Scarified seed heads of the opium poppy, Papaver somniferum, with traces of the dried juice that is processed to produce the drug.

Throughout recorded human history, and undoubtedly before, plants have provided the basis of therapeutics, and there are few plants in this volume that have not been used by someone, somewhere, at some time, to try to alleviate the ills or injuries that plagued them. But the plants in this section possess compounds with specific physiological effects on the human body, and some of them are still important in modern scientific medicine.

Anything, in certain circumstances, can be a poison, and the balance between heal and harm is always finely judged. Cocaine, the alkaloid from the South American plant Erythroxylum coca, is a powerful local anaesthetic, but also central to the lucrative international trade in illicit drugs. Opium, an effective remedy for pain, can be extracted from the poppy, which is the source of morphine too, another useful drug, but also of heroin, ironically introduced as a less addictive alternative to morphine.

The willow tree has a long use in medicine, and its main therapeutic ingredient, slightly modified, yielded aspirin. Preparations of aloe can also be found in the home medicine cabinet, and it is an ingredient of many cosmetics. Rhubarb is now mostly enjoyed as an early spring fruit, instead of as a purgative, which its roots can produce. Citrus fruits, a relatively late arrival in Europe in any quantity, were appreciated for their power to both prevent and cure scurvy, a common disease of long voyages and among land people with limited winter diets.

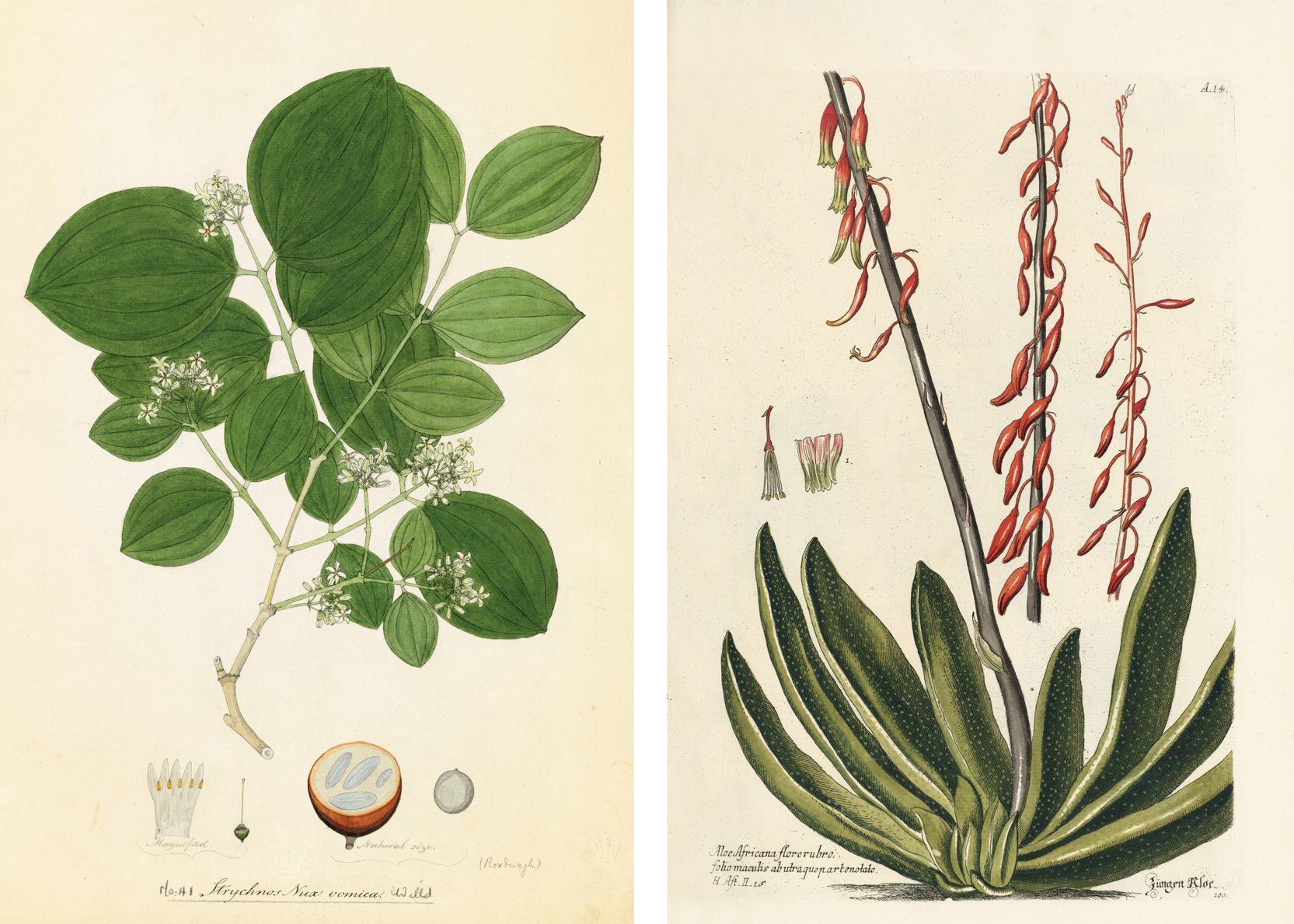

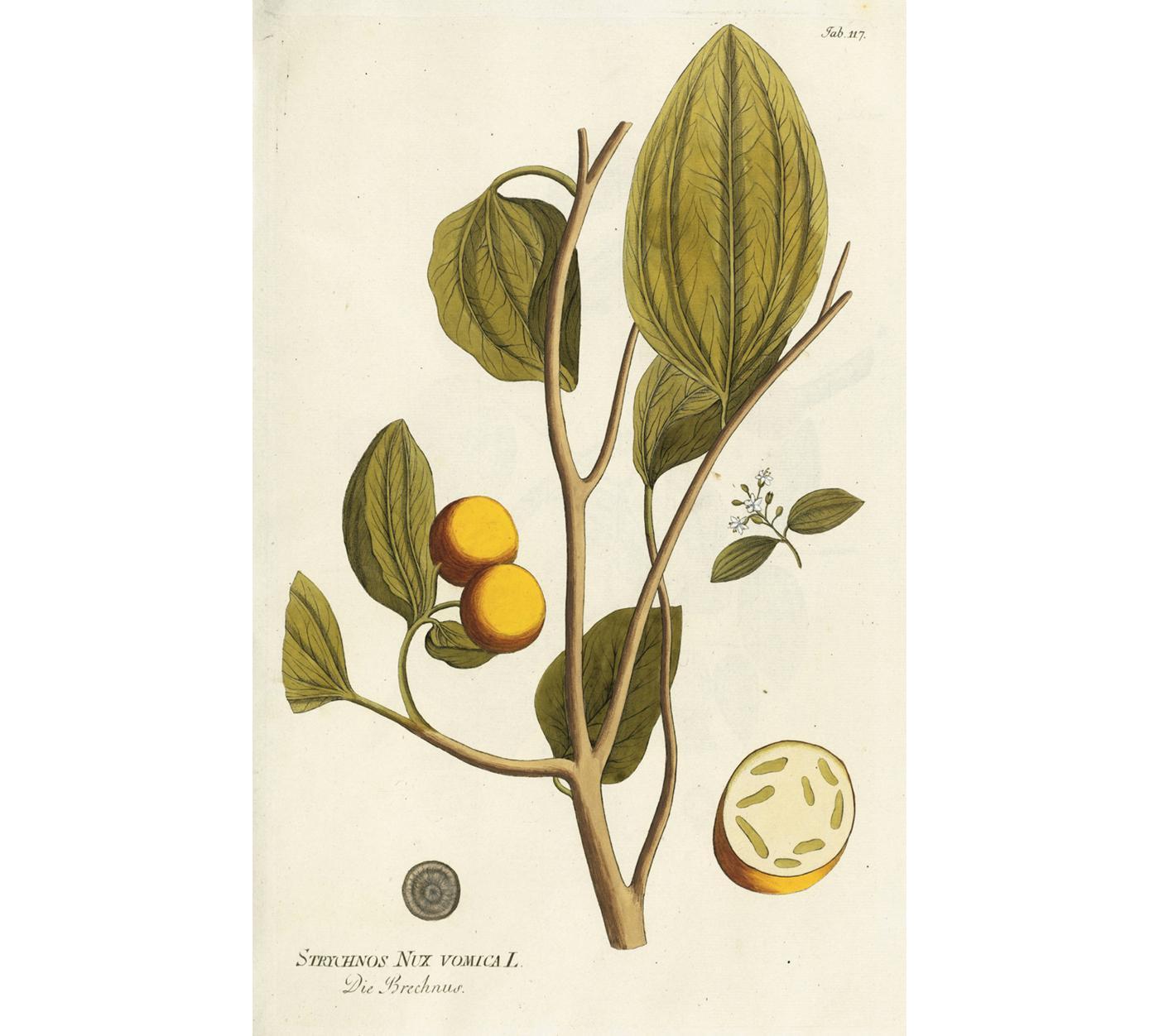

Left Strychnos nux-vomica drawn by one of the Indian artists employed by the surgeon-botanist William Roxburgh to illustrate the plants he had collected from Coromandel, the east coast of Madras in the 1780s and 1790s.

Right One of the many distinctive aloes of the southern Africa ‘hotspot’, described before botanists used the term but were aware of the variety of species, as featured in G. K. Knorr, Thesaurus rei herbariæ hortensisque universalis (1770–72).

Two species of Strychnos, one from Asia and one from South America, produce substances which swing the balance between healing and harm towards the latter. This did not prevent S. nux-vomica, the Asian species, from enjoying a long history as a tonic. Its active ingredient, strychnine, was also used as a rat poison and an agent of murder. The South American counterpart yielded curare, which kills by paralysing muscle action. It found use in surgery before better relaxing agents were discovered. Ancient Indian doctors used the roots of Rauvolfia to treat snake bites and much else. Its active alkaloid, reserpine, enjoyed a brief period of use in the West, when it was found to lower blood pressure. It also seemed promising in psychiatric disorders, but, as with curare, other drugs soon replaced it. On the other hand, both quinine, from South America, and artemisinin, from China, are still important in the battle against malaria, a major modern killer.

Plants can also produce steroids, and the Mexican yam was the source of the cheap steroids that yielded the contraceptive pill (‘the Pill’), one of the most important medical innovations of the past half-century. It needed modern chemistry to modify it, and chemistry has also played its part in turning a substance from the Madagascar periwinkle into a treatment for childhood leukaemia.

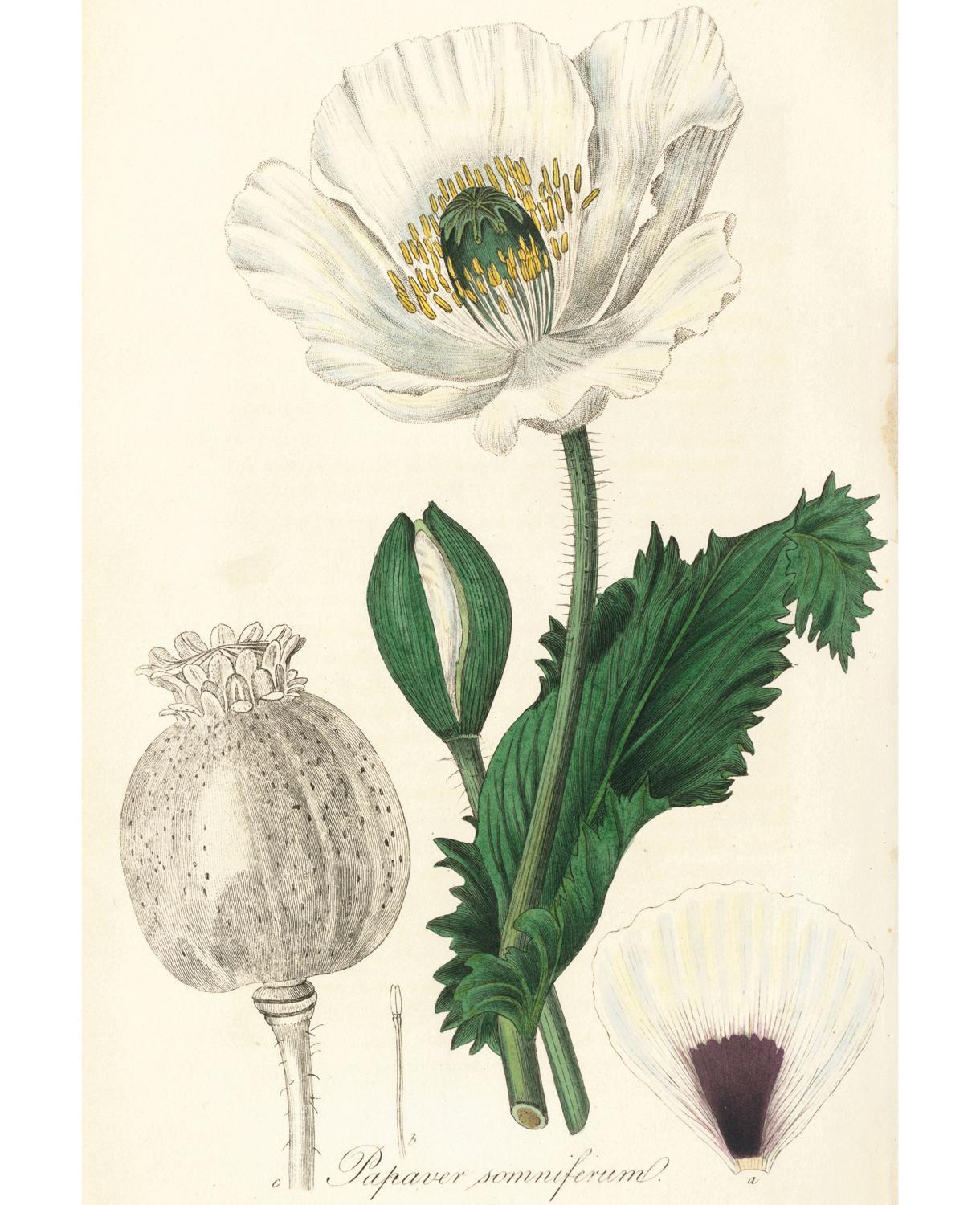

Papaver somniferum

All [Mrs. –’s] friends advised her to lay aside the use of opium, lest it should by habit become necessary; but she whispered me privately, that she would rather lay aside her friends.

George Young, 1753

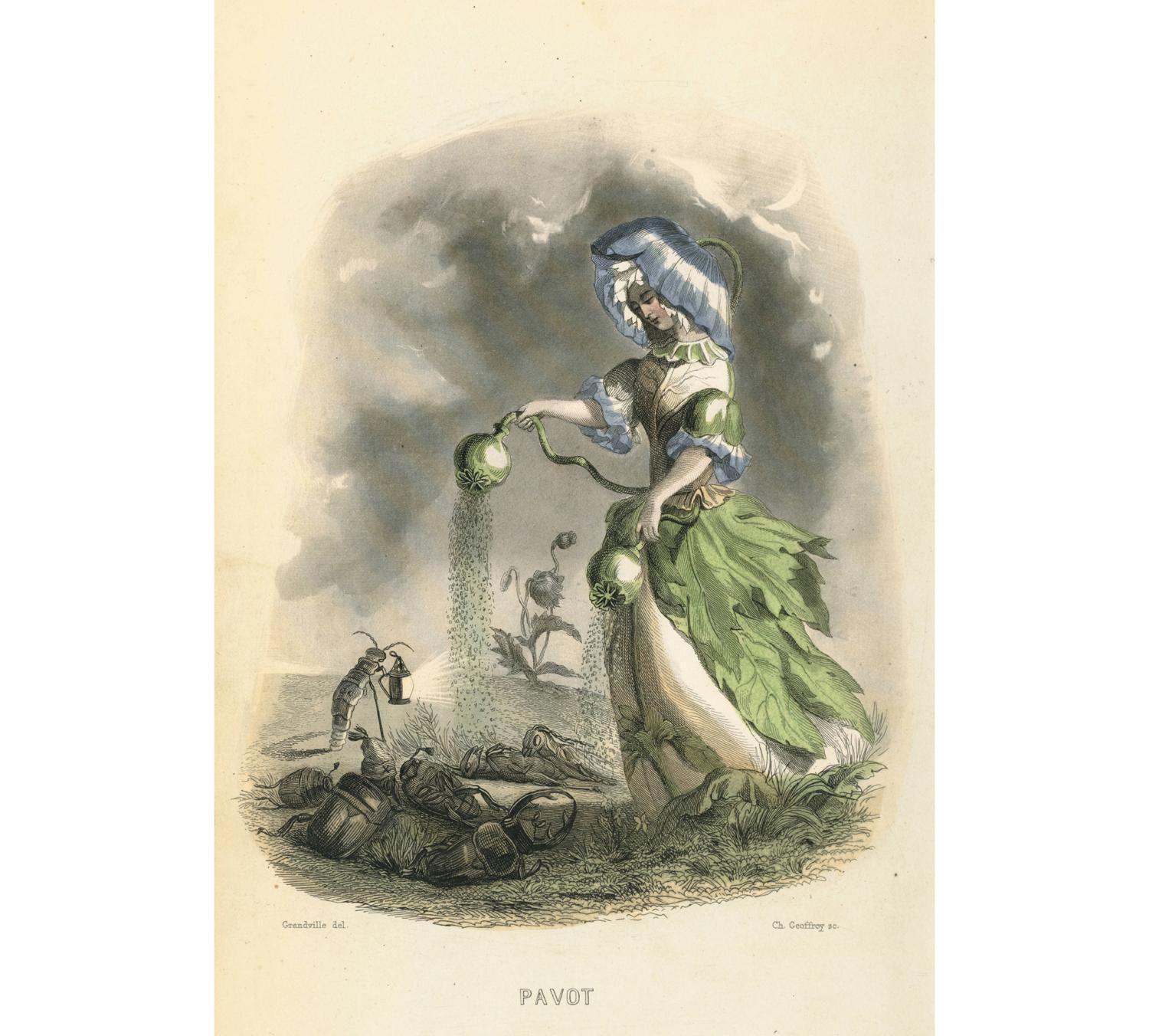

The ‘Pavot’ (poppy) from J. J. Grandville’s Fleurs animées (1847) sprinkles her seeds and puts the insects to sleep. The accompanying poem ‘Nocturne’ (by Taxile Delord) refers not just to peaceful sleep but also to the power of narcotic-induced dreams. The Romantic poets Coleridge and De Quincey both reported using opium to heighten their creative powers.

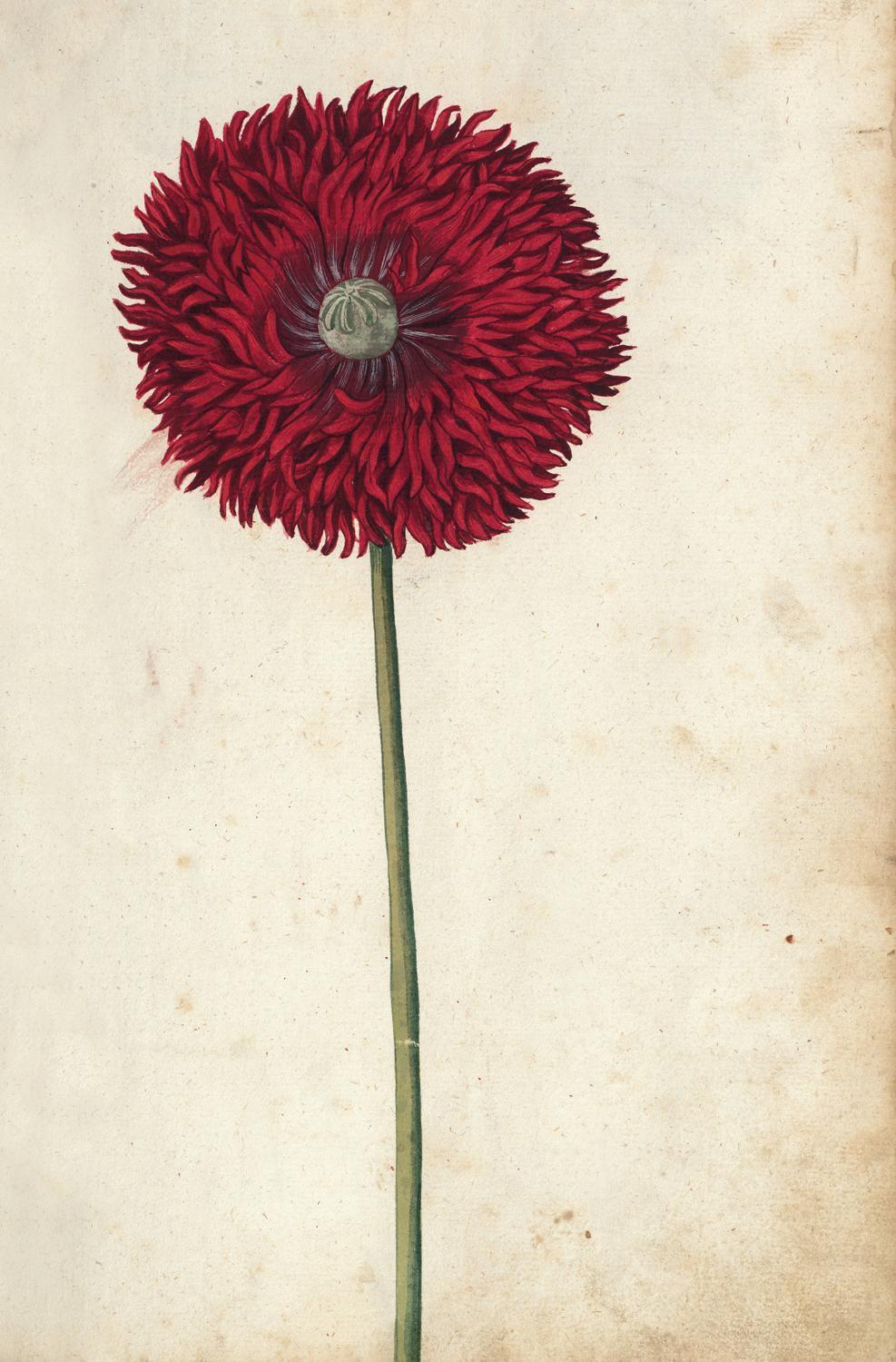

Poppies had become popular by the 16th century, manipulated into different colours and shapes from the native plants of Asia. Turkey was a major source of garden specimens. This watercolour of a red-fringed opium poppy by the German Sebastian Schedel appeared in his Calendarium (1610), which was arranged month by month as the flowers came into bloom.

The field poppy (Papaver rhoeas) is native to Europe, where it grows almost everywhere, mostly as a pretty weed of agriculture; it is often red. The opium poppy (P. somniferum), generally white, is also vigorous and has long been deliberately grown for its main product: opium. The poppy was in fact among the earliest cultivated plants, probably first tamed in the western Mediterranean, known to Neolithic man and appreciated by early Mediterranean cultures, including in Egypt, Crete, Greece and Rome, and used as far east as India. The Hippocratics (5th–4th century BC) recommended it for pain control as well as for treating diarrhoea and many other diseases, or for producing sleep. Dioscorides, the great 1st-century AD authority on drugs, described opium as having cooling properties, thereby useful for hot conditions.

Harvesting the poppy is not easy: the unripe capsule must be scored at the correct time to exude the crude opium juice, which is collected and processed by drying in the sun and boiling. What was originally a sticky white liquid becomes a brown paste, and further sun drying produces a brown, clay-like substance, much richer in opium and easy to mould into cakes or rounds for transport. Knowledge of these techniques is prehistoric: small juglets made in Cyprus and exported to Egypt and elsewhere, which contained opium, resemble the inverted shape of the poppy head and are often scored or painted in imitation of incisions.

That ingesting opium could produce a sense of euphoria was long known; so was the fact that ever-larger doses were often necessary to achieve the same effect, as well as the substance’s ability to create dependence in its users. An overdose could kill, and opium was undoubtedly used in murder, including reportedly by the emperor Nero (37–68). A later, more admired emperor, Marcus Aurelius (121–80), whose personal physician was Galen, used opium regularly, but was apparently able to control his dosage and thereby maintain self-control. The ‘bondage of opium’ over the centuries has been highly variable in different regular users.

Most opium habitués probably first encountered the substance medicinally, as it was a mainstay in the doctor’s armamentarium – ‘God’s own medicine’, according to Sir William Osler, the 19th-century Canadian physician – and used at times for virtually every disease or symptom. ‘Opium and lies’ was Osler’s pungent recommendation for treating advanced tuberculosis. The reforming 16th-century doctor and alchemist Paracelsus might have rejected much of traditional medical knowledge, but he retained opium as a favourite remedy. He coined the term ‘laudanum’, although it was the recipe of Thomas Sydenham in the 17th century that became standard: a mixture of opium and red wine, spiced with saffron, cloves and cinnamon. So enthusiastic was Sydenham about opium that he was dubbed ‘Opiophilos’.

During the 18th and 19th centuries, many patent medicines, including Dover’s Powders, Godfrey’s Cordial and Daffy’s Elixir, contained opium (and generally alcohol). Such medicines were used as cure-alls, as well as for keeping children quiet and soothing frayed nerves. Their unregulated sale until well into the 19th century meant that they provided a major source of income for quacks, druggists and apothecaries.

The addictive properties of opium led to social and legal concerns, even if many men of letters, most famously the poet Thomas De Quincey, statesmen and others of all classes, occupations and both sexes depended on its daily physical and psychological effects. Governments, too, valued the revenue its import raised, and this was especially true in British India. India and Turkey were the two primary sources, with Turkish opium generally used in Europe. However, the opium poppy was also widely cultivated in India, both for local use and, increasingly, for export to China, which since the 18th century had provided a market for social use (it had earlier been employed there medicinally). There was some official disquiet in Britain that opium export to China was not entirely ethical, as it created a culture of dependency, and Chinese authorities legislated against its importation and use in the 19th century. The two Opium Wars (1839–42 and 1858–60) were about much more than just opium, but they did forcibly smooth the Indian-Chinese trade.

In the meantime, the chemical contents of the opium juice were analysed. Its most potent alkaloid, morphine, named after the Greek god of sleep, was isolated in 1804 and marketed a couple of decades later. Codeine, currently the most widely used opium derivative, followed in 1832, and these discoveries allowed pharmaceutical entrepreneurs to market the products in more or less pure form. Heroin, chemically adapted from morphine, was introduced in 1898 as a ‘safer’ alternative to the latter. The development of syringes in the 1850s made the effects of all opiates (and other substances such as cocaine, another plant-derived substance) much more powerful, and increased addiction and dependency. National and then international attempts to control the sale and use of opiates and other addictive substances followed.

Poppy Seed Head, by Brigid Edwards. The dried seed capsule functions like a pepper pot, sprinkling the seeds from the pores. These natural structures provided the inspiration for ancient jewelry and pottery. Small jugs were exported from Cyprus in the 2nd millennium BC to Egypt, Syria and Palestine. When inverted, their shape mimics the poppy capsule and enough of their original contents has survived to reveal that they were used to store opium.

The classic white opium poppy. The Greek doctor Galen (129–c. 210) extolled the virtues of Olympic Victor’s Dark Ointment. This salve contained opium and dried to an elastic patch. It provided an external way to relieve pain and swelling, especially around the eyes.

The ‘war on drugs’ from the early 20th century has not been a notable success. Making them either prescription-only, or completely illegal, has had the unfortunate consequence of driving supply and use underground, and created a criminal class to exploit the market, estimated to be worth some $350 billion a year. The rise of AIDS in the 1980s compounded the health issues, as the use of dirty needles spread this and other diseases among users. Afghanistan has emerged as the world’s leading supplier of opium, but the Golden Triangle countries of Southeast Asia, as well as Colombia, are also leading players. Morphine and codeine are still widely used in medicine, but the delicate balance between heal and harm remains.

Cinchona officinalis, Artemisia annua

The Peruvian bark became my sheet anchor.

Thomas Sydenham, 1680

Malaria was a serious problem in India and during the colonial period the British managed to establish Cinchona plantations and produce the anti-malarial drug quinine for local use. These packages (dating from 1925) were sold in post offices.

A flowering sprig of the Cinchona officinalis tree and the quinine-containing bark. Europeans tended to uproot and strip the tree, but this was unsustainable in South America and unlikely to appeal to a plantation owner. Various methods were developed to harvest the bark in such a way that the tree would live and the bark regenerate so the operation could be repeated at a later date.

For more than two centuries, ‘the Bark’ was shorthand for a medicine derived from Cinchona, a genus of about forty species of evergreen trees indigenous to the elevated slopes of the South American Andes. Two species, C. officinalis and C. pubescens, and a cultivar, ‘Ledgeriana’, contain significant amounts of alkaloids, of which quinine and quinidine are especially important.

To the indigenous South American peoples ‘quinquina’ meant ‘bark of barks’, and cinchona bark was undoubtedly used medicinally in pre-Columbian Peru and other Andean areas. Malaria probably arrived only with Europeans, although the mosquitoes that we now know transmit the disease were already there. The story that the bark was recommended to treat the malarial fever of the Countess of Chinchon in 1638 is apocryphal, but accepted by Linnaeus, who misspelled her name when creating the genus Cinchona. Spanish physicians and missionaries learnt of the value of Cinchona bark in treating intermittent fevers (generally what we would call malaria), and shipped the new drug back to Europe, where malaria was common.

Variously called Peruvian Bark, Jesuit’s Bark or simply the Bark, the new remedy for fever established itself in the 17th century when an enterprising English practitioner used it at the French court. At that time the diagnosis and treatment of ‘fever’ were based simply on symptoms or individual clinical experience, and the bark varied in quality. Nevertheless, it was a significant source of income for Spanish Peru, which meant that access to the trees was carefully controlled.

Two French chemists, Joseph Bienaimé Caventou and Pierre Joseph Pelletier, isolated the active principle, quinine, in the early 19th century. This made dosage much easier to manage, and with European imperial expansion in Africa and Asia demand was very high. Both the British and the Dutch were keen to smuggle seeds out of Peru. Behind the British initiative was Joseph Dalton Hooker, director of Kew Gardens from 1865 to 1885, whose extensive experiences in India, where malaria was rife, allowed him to see the potential for establishing Cinchona plantations there. The Dutch eyed their possessions in Java.

There were farcical elements in these early attempts at botanical espionage, as seeds from the wrong species were obtained and the long voyage back to England took its toll. By 1861 Kew had seeds, and seedlings destined for India were raised. These were transported in Wardian cases, special sealed glass boxes used in shipping plants in the 19th century. Plantations were established in India, Ceylon (Sri Lanka) and Java, easing the supply of quinine, although the need was always great. The bark was gathered in the traditional way by cutting from only part of the tree so that it could recover, and then drying the product in the sun before processing.

In the late 1890s, Ronald Ross and Giovanni Battista Grassi discovered the life cycle of the Plasmodium parasite that causes malaria and its method of transmission by the bite of female Anopheles mosquitoes. This helped explain its geographical prevalence in marshy areas and tropical lands where frequent thunderstorms left breeding puddles. Mosquito control became part of the preventative strategy, but quinine, taken as a prophylactic and as treatment, remained essential. Disruption of supplies during the Second World War encouraged the development of alternative synthetic drugs, of which there are now many. Although quinine-resistant strains of Plasmodium now exist, quinine long remained effective and is still used in treating some forms of the disease; quinidine, the other main alkaloid in Cinchona, is used to treat heartbeat irregularities.

The causative parasite of malaria has unfortunately acquired resistance to all front-line treatments, but in the battle against the disease the plant world has yielded another drug for the modern armamentarium. Sweet wormwood (Artemisia annua) is a bit of a weed. It grows easily on slopes, at the forest limits and on waste ground disturbed by human activity. It also contains a powerful anti-malarial compound, artemisinin (qinghaosu). This and its derivatives, which allow the drug to be given by injection as well as orally, stepped into the breach as drug-resistant malaria reached frightening levels in Southeast Asia in the aftermath of the region’s wars and population displacements. Malaria, much like wormwood, thrives in chaos.

Qinghao (A. annua) had been part of the Chinese pharmacopeia since the 2nd century BC. What brought it to the fore internationally was a request from North Vietnam during the Vietnam War for China’s help with anti-malarial drugs and the circumstances in China at the time. Mao sought to both destroy and utilize China’s past; modern science would strip the best from traditional medical texts and make China self-sufficient in medicinal products. In 1967 a secret project – 523 – was set up to screen plants such as A. annua for their anti-malarial potential. The pharmacologist Tu Youyou led the team, and as well as the source plants, she also paid attention to the original method of producing the drug, as described in the 4th century AD by Ge Hong in his Emergency Prescriptions Kept Up One’s Sleeve. He was the first to recommend qinghao for ‘intermittent fevers’ and his instructions provided a vital clue that great heat should not be used in the extraction process. In isolating the active component of the plant extract, Professor Tu produced the first water-soluble artemisinin derivative.

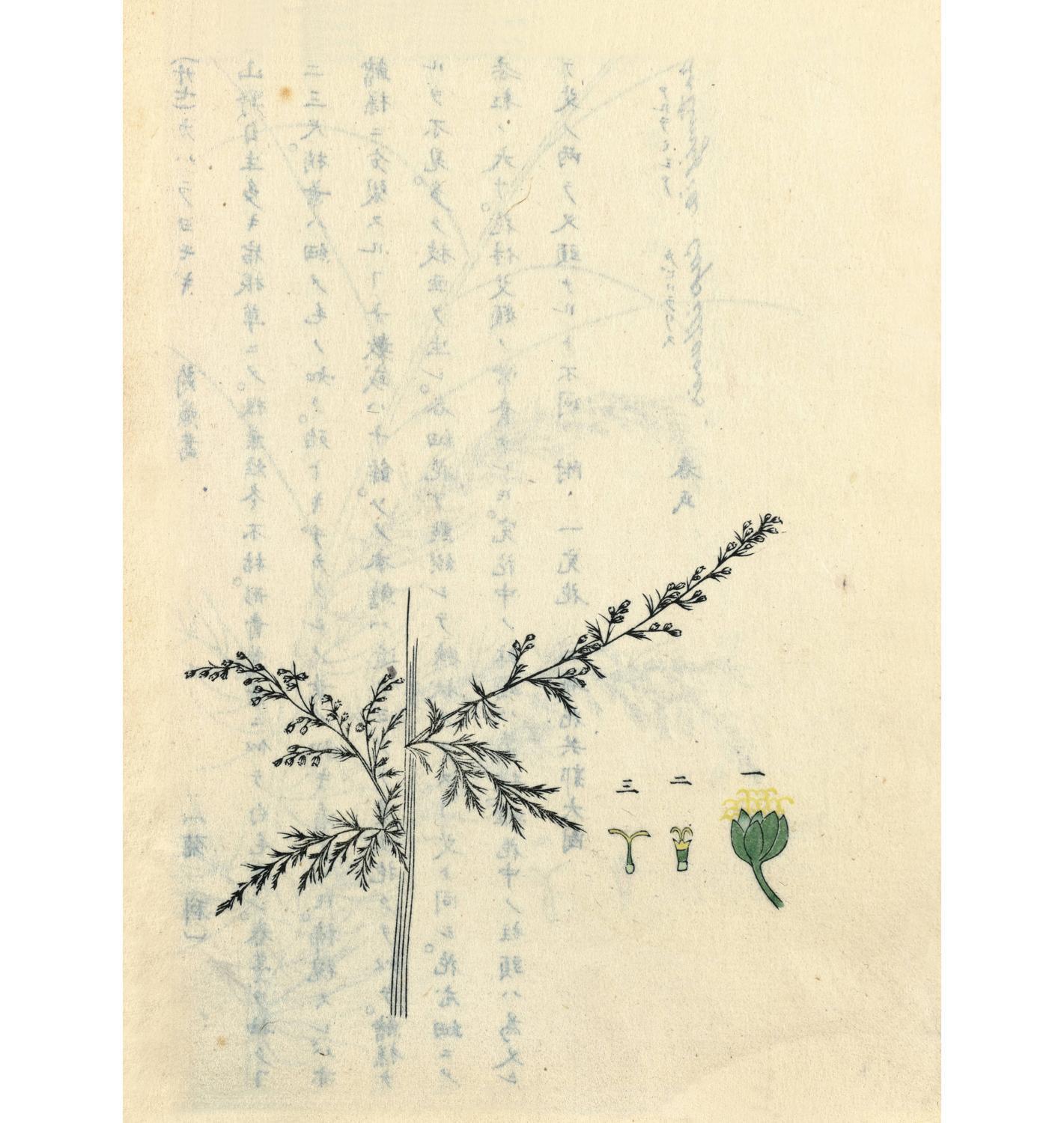

The Chinese anti-malarial Artemisia annua from Somoku-Dzusetsu; or, an iconography of plants indigenous to, cultivated in, or introduced into Japan (1874). The second edition was edited by two botanists, Tanaka Yoshio and Ono Motoyoshi, who were involved with Japan’s modernization. Tanaka is known as the ‘father of museums’ and Ono edited a bilingual dictionary of botany, much used in China.

Although there was some scepticism when the rest of the world learnt of China’s new anti-malarial drug in 1979, today various artemisinin drugs are a crucial part of the World Health Organization recommended ACT (artemisinin combination therapy), which uses a cocktail approach to curtail parasite resistance. The cat-and-mouse battle between drug and parasite continues.

Rauvolfia serpentina

Only in the last twenty-five years has the scientific world begun to discover the true value of Rauwolfia. Credit must be given to the chemists and pharmacologists in India who started to analyse crude extracts of R. serpentina.

Jurg A. Schneider, 1955

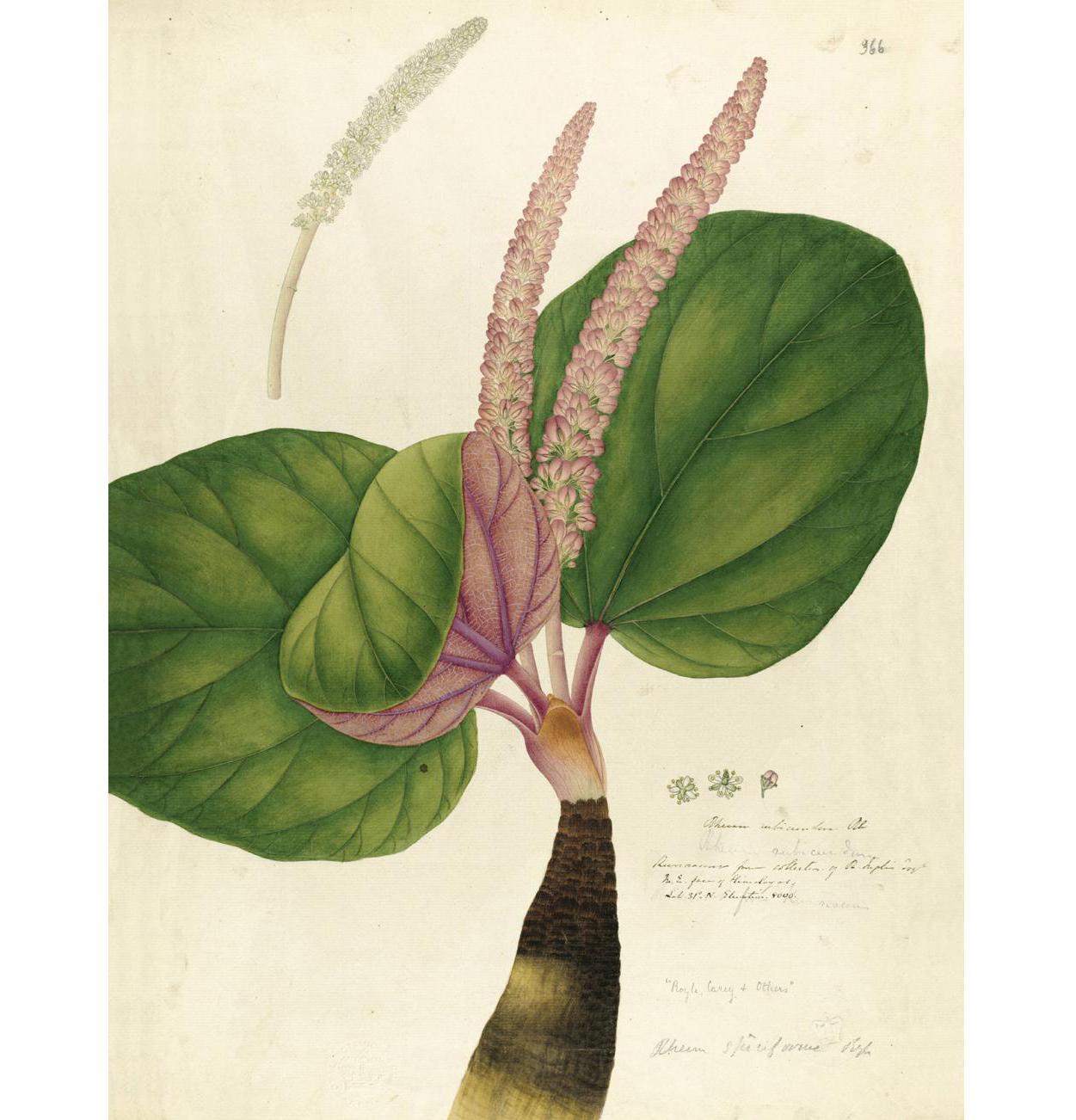

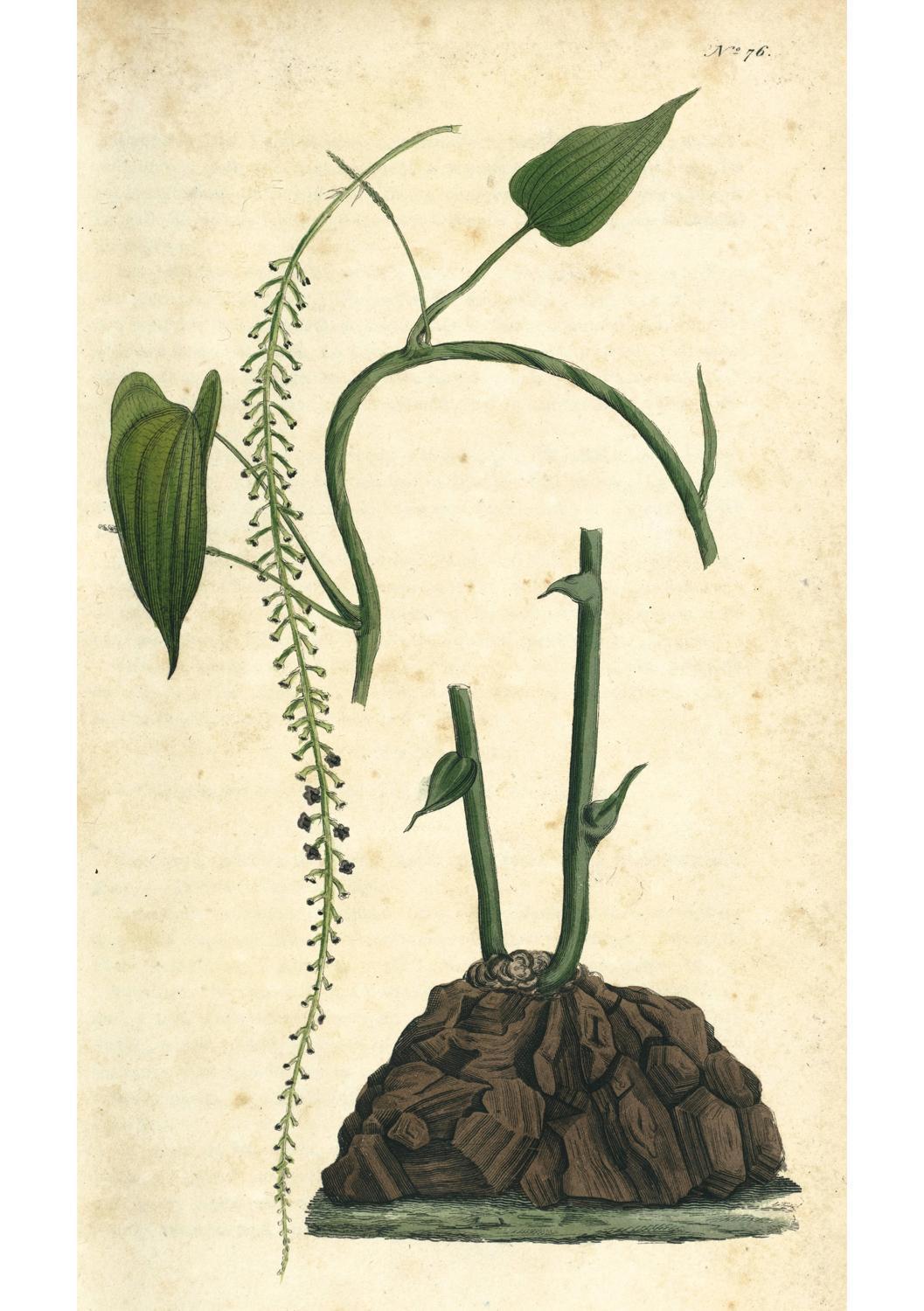

Watercolour of Rauvolfia, believed to be from the collection of Claude Martin (1735–1800). Born in France, Martin deserted his native army and thrived in that of the British East India Company, settling in Lucknow. Here he established a museum and commissioned Indian artists to paint the plants and birds of his adopted country.

Rauvolfia (often spelled ‘rauwolfia’) is a large genus of about 200 species of trees and shrubs with a wide distribution in tropical climates. It is frequently considered as a weed, so vigorous is its growth. The genus was named for the 16th-century German doctor and naturalist Leonhard Rauwolf, who travelled widely in Southwest Asia and described many new species of plants and animals, though he never actually saw any examples of ‘his’ genus, which was named later in his honour.

In India, where it is known as Sarpagandha, Chandra and Chotachand, the dried roots and leaves of Rauvolfia serpentina have long had a place in Ayurvedic medicine. Powder made from the plant had a variety of uses, including as an antidote against snakebite. It was also employed to calm agitated patients, and to treat insect stings and diarrhoea. In the West rauvolfia was regarded as little more than a curiosity. Then, in 1931, two Indian scientists analysed the ground root powder and identified several alkaloids. It was assumed that the root’s physiological effects came from a cocktail of the alkaloids, but many laboratories, both in India and elsewhere, began to study the chemical makeup in detail and the most potent of these many alkaloids, called reserpine, was isolated in 1952.

The whole root had already been shown to lower blood pressure in laboratory animals, and this newly isolated alkaloid came at a time when high blood pressure had been implicated in rising rates of heart disease and stroke throughout the Western world. In the 1950s there were few safe drugs that could reduce blood pressure and major surgery was sometimes resorted to, involving cutting along the spine and thus disrupting the sympathetic nerve fibres, which act to reduce arterial diameter. It was dangerous and left the patient with serious side effects.

The promise of this new drug led to a systematic survey and chemical analysis of rauvolfia plants from around the world. Many were found to contain reserpine, and supplies of the drug came from Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Burma (Myanmar) and Thailand as well as India. This was important, since the Indian authorities had been reluctant to give up their hold on the new wonder drug. From the late 1950s, after it was approved for patient use in the US and Britain, the main use of reserpine was to treat raised blood pressure. However, it also created much excitement in psychiatric circles, since the drug had a calming effect too. It began to be given to patients in psychiatric hospitals, where improvement was reported in schizophrenics whose behaviour became more tractable.

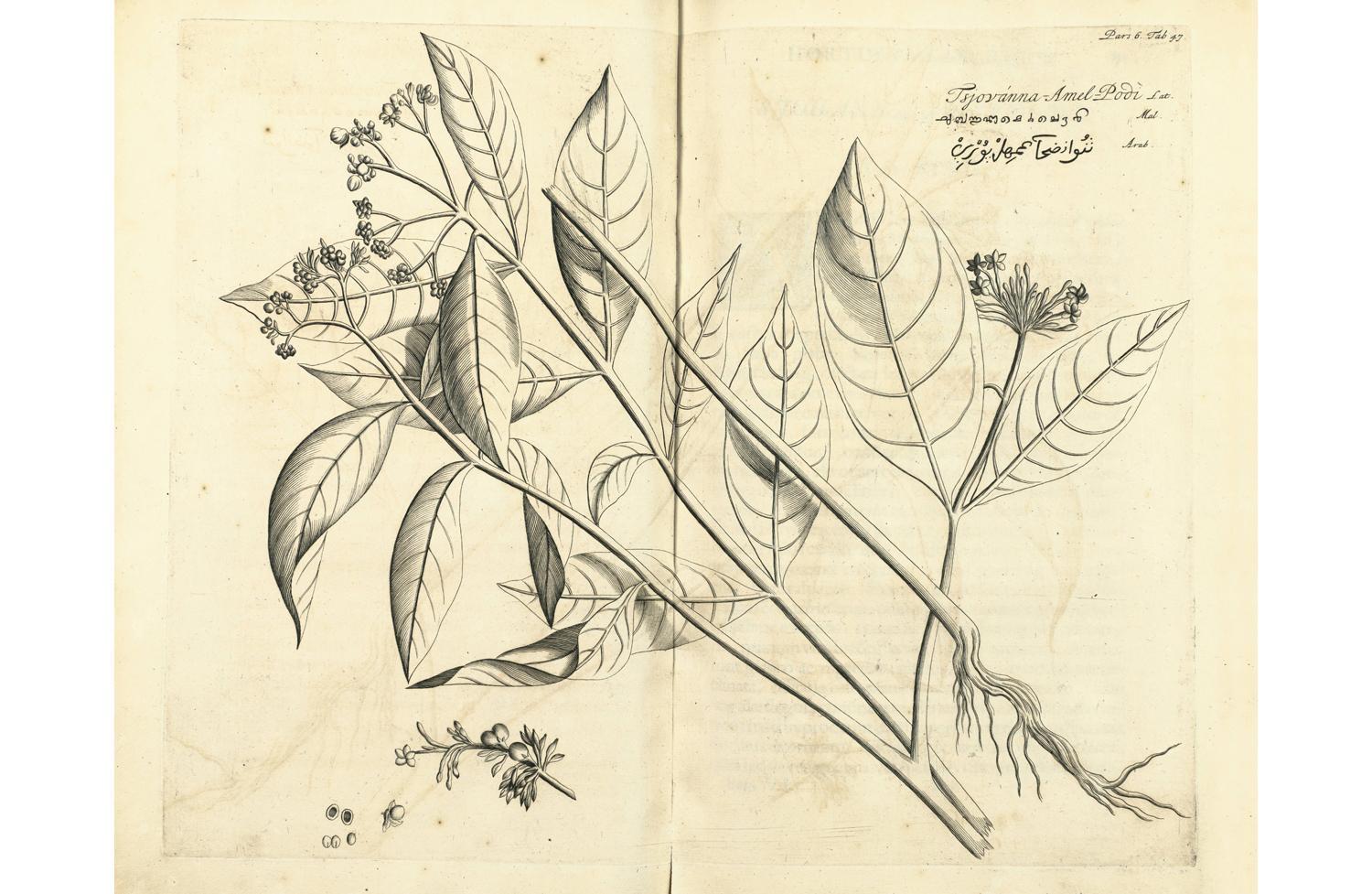

Rauvolfia, from Hendrik van Rheede’s Hortus Malabaricus. It is not surprising that traditional healers in the Indian subcontinent tried to find remedies against snakebite. Recent research finds that the region bears the greatest burden of envenoming and death in the world, with 81,000 venomous bites and nearly 11,000 deaths each year.

The early promise did not hold. Reserpine’s reported side effects included depression, with several suicides attributed to its use. Intense pharmacological research into how the drug worked suggested that it might actually relieve depression rather than cause it. It acts on the nerve endings in the nervous system, blocking the release of several chemicals (called monoamines) crucially involved in activity in the central nervous system. This helps explain its calming influence, but also fed into an early theory about a biological cause of depression. There are now far better drugs available for both blood pressure control and mental disorders, so reserpine has retreated into the laboratory, where it continues to be used by scientists seeking to understand the minute workings of the brain.

Erythroxylum coca

For me, there still remains the cocaine bottle.

Sherlock Holmes, in The Sign of Four, Arthur Conan Doyle, 1890

Snakes and coca leaves were both sacred to the Incas. Recent analyses of Inca mummies found in a shrine in 1999 reveal that in the 12-month period leading up to their sacrificial death, as part of capacocha rituals, the three children ingested increasing amounts of coca leaf and chicha beer. This is in addition to the sizeable quid of coca leaves found clenched between the teeth of the 13-year-old girl.

For the Incas coca was sacred; it was so important that the state monopolized its production and distribution, and coca leaves were offered to the gods. A small tree or shrub, coca grows best on the lower slopes of the tropical Andes and its use in the area has a long history. The leaves, which can be harvested several times a year, contain a potent cocktail of alkaloids, of which the most significant is cocaine; they also contain a small amount of caffeine.

When gathered, dried and mixed with some lime, the leaves can be placed between the cheeks and gums, where their alkaloids are slowly absorbed. The result is an increase in muscle strength, a reduction of hunger and a general sense of alertness. Spanish conquistadors described the plant and its effects, and when they forced native peoples to labour in their mines, they ensured that they were supplied with the leaves to increase production. In the mid-19th century two German chemists independently isolated its most potent alkaloid. One of them, Albert Niemann, gave it the name that has stuck: cocaine.

Cocaine was one of many plant alkaloids attracting medical and chemical attention at the time; the young Sigmund Freud, then a budding neurologist, started self-experimenting with it in 1884. His collection of papers on the subject, ‘Über Coca’ (On Coca), more advocacy than sober scientific analysis, came back to haunt him. He downplayed any addictive qualities of the drug, emphasizing the psychological euphoria and increase of energy and muscular strength. One of Freud’s colleagues, the ophthalmologist Carl Koller, noticed at the same time that cocaine was a powerful local anaesthetic.

It took some time before cocaine’s potent addictive qualities were appreciated, and in the meantime enterprising pharmaceutical companies sold the drug with a syringe for ease of administration, and it became an ingredient of popular beverages. Cocaine was also touted as a safe way to break morphine addiction. Sherlock Holmes was habituated to cocaine, although his creator, Arthur Conan Doyle, eventually broke his character’s habit, as the dangers of cocaine use became more obvious. Among prominent individuals trapped by cocaine in those early days was the pioneer of aseptic surgery, William Stewart Halsted, professor of surgery at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. Although he managed to keep his career going, he never completely lost his addiction to morphine, which he substituted for cocaine.

Herbarium specimen of Erythroxylum coca. Coca leaves are browsed by the vicuña and guanaco; the alkaloids in the leaves have a local anaesthetic effect on the animals’ stomachs, creating a false sense of satiety. They lose their appetite and leave the plant alone, and once the cocaine and other chemicals reach the brain, the effect of heightened energy and mild euphoria encourages them to move on. Just as these animals are not addicted to coca leaves, human use in a similar manner does not lead to the dependency associated with processed cocaine.

Despite medical uses, cocaine has become a controlled drug in most places. Criminalizing its use has not met with marked success, and cocaine, both in its pure state and in the adulterated form of ‘crack’, is used by millions of people. Supplying it is highly profitable, especially for Colombia, despite encouragement for growers there to plant coffee trees instead, or for Peruvians to grow asparagus.

Strychnos nux-vomica, S. toxifera

‘Strychnine is a grand tonic, Kemp, to take the flabbiness out of a man.’

‘It’s the devil,’ said Kemp. ‘It’s the palaeolithic in a bottle.’

H. G. Wells, The Invisible Man, 1897

Strychnos nux-vomica, showing the smooth-shelled orange fruits, which reach the size of a large apple and contain a soft, jelly-like pulp. The seeds were reportedly used in southern India to add to the potency of distilled spirits. The wood is hard and durable, and along with the roots, this exceedingly bitter-tasting material was traditionally used to treat fevers (no doubt including malaria) and snakebite.

In plants, alkaloids have a variety of functions including protection from animal predators, since many of them are poisonous. Two species of Strychnos, a genus of almost 200 trees and vines scattered throughout the tropical world, manufacture especially potent alkaloids. The main active principle of the nut of S. nux-vomica, from South and Southeast Asia, is strychnine, one of the first alkaloids isolated by modern chemists in the early 19th century. The South American S. toxifera contains curare. Each of these two alkaloids played a significant role in their indigenous cultures, as well as in the West.

Although nux-vomica is sometimes mistakenly assumed to mean ‘emetic nut’ (the vomica means ‘depression’ or ‘cavity’), strychnine in fact makes it harder to vomit, as doctors trying to treat overdoses learnt to their cost. Strychnine is a nerve stimulant, producing spasms and, in high doses, convulsions and death. The nuts of the tree acquired their place in medicine because of their obvious stimulating effect and were also thought to protect against snakebite. S. nux-vomica has a long history in Indian Ayurvedic medicine and Arab doctors knew of the medicine in the Middle Ages. The Portuguese in Goa studied it and began importing it to Europe.

In Western medicine nux-vomica was prescribed for many complaints and was available over the counter for people wishing to treat themselves. With its obvious effects of tightening muscles and generally stimulating those who took it, it seemed to be a ‘pick-me-up’. Even after its active principle, strychnine, was isolated the crude drug, ground from the nut, continued to be favoured. Ironically, it was also used as a rat poison as early as the 16th century, and both nut and its alkaloid could be used for more sinister purposes. Strychnine was harder to detect than the other favourite Victorian poison, arsenic, which meant that doctors, who had easy access to it, preferred it. The infamous poisoner William Palmer used it to murder his mother-in-law, (possibly) his wife and several children and a friend, and Thomas Cream, another doctor, used it serially. Both were hanged. As chemical detection methods improved, and, eventually, supplies were more systematically controlled, strychnine fell from favour. Even its use as a poison for vermin was finally outlawed, and it faded from the scene, except in detective fiction.

Two gourds from Guyana containing curare made from Strychnos toxifera bark and used to tip poison arrows. These were collected by Robert Spruce (1817–93), who travelled extensively in South America at the behest of Sir William Hooker at Kew and George Bentham, who described many of the specimens Spruce collected.

While strychnine the medicine became classed as a poison, curare the poison acquired a legitimate place in medicine. In the tropical regions of South America, hunters dipped their arrows in a substance obtained from Strychnos toxifera as they were aware that it caused paralysis, making killing game easier. It was also used in warfare. Early European explorers naturally became intrigued, and samples of the miraculous substance reached Europe by the late 16th century. But it remained largely a curiosity until the famous French physiologist Claude Bernard showed in 1856 that curare, as the active principle was called, acted to block the junction between the motor nerves and the muscles. Death was caused by suffocation, as the muscles controlling breathing were paralysed. An experimental animal could be kept alive by artificial ventilation, and because the other muscles were also paralysed, and therefore flaccid, operations were easier to perform. The drug thus became an important adjunct to modern surgery, with ventilation controlled by the anaesthetist. Although curare has been replaced by newer relaxing drugs, working out its mode of action greatly contributed to our understanding of how nerves and muscles interact.

Rheum spp.

Nor was it till I had turned back the curious bracteal leaves and examined the flowers that I was persuaded of its being a true Rhubarb.

Joseph Dalton Hooker, 1855

‘True rhubarb’ from Athanasius Kircher’s China Illustrata (1667). Kircher did not go to China, relying instead on the accounts of fellow Jesuit missionaries Michał Boym and Martino Martini who did. Kircher referred to the importance of retaining the moisture in the harvested root, as if it dried completely it would lose its strength.

Rhubarb has now earned the plaudit of ‘superfood’, a fairly meteoric rise for a plant that has only been eaten seriously for about two hundred years. As a medicinal, rhubarb is much older, but rather than the stems of the dessert vegetable it is the dark-skinned roots that are used. Rhubarb root, especially of species identified as Rheum officinale, R. palmatum and R. tanguticum, featured in early Chinese medical texts and was well known to folk practitioners, particularly as a cathartic.

Most of the sixty or so species of rhubarb are found on the mountainsides and desert areas of northern and Central Asia, where they have evolved into wonderfully diverse forms. Traded along the Silk Road, rhubarb root entered the Western pharmacopeias in the 1st century AD. Dioscorides described it as a stomach tonic, stimulating the appetite and assisting digestion. Persian practitioners recommended it as a stomach strengthener to counteract headaches after too much wine. It was not until the Middle Ages that its purgative properties garnered attention. As rhubarb’s gentle laxative nature became better known, together with a growing awareness of the sale of many inferior roots, Europe became increasingly interested in sourcing ‘true rhubarb’. The Portuguese were delighted to bring it home from Macao after opening their Chinese trading port there in the 16th century. The Dutch and British entered the competition, but the interior of China and the finest root still remained unreachably remote.

The Russians were the most successful in bringing the best rhubarb through to Amsterdam in the 17th and 18th centuries. Keen to maximize their profits, the Russian state instituted strict quality control at Kyakhta on the border with Mongolia. By this time rhubarb seeds had also made their way West, and gardeners as well those in charge of the physic and botanic gardens were trying to produce plants of medicinal quality. The Royal Society of Arts in Britain offered medals for sizeable plantations, but debate continued over which variety was the ‘true’ rhubarb as the potency of homegrown roots proved disappointing.

Rhubarbs do not come true from seed and readily hybridize to produce new varieties, which can be perpetuated by root division. This is perhaps what led to the development of culinary cultivars. First sold with limited success in Covent Garden in London in the early 19th century, the pink stalks gained in popularity after the arrival of cheap sugar sweetened their tartness. Forcing plants with warmth and by excluding light also produced a more refined delicacy than field-grown plants. The tender stems, ready early in the year, brightened the winter tables of the wealthy. In America, master plant breeder Luther Burbank produced superb new varieties.

Rheum spiciforme, like most of the 60 species of rhubarb, is native to the countries of and fringing the Qinghai–Tibetan Plateau, ‘the roof of the world’. It is thought that the rapid uplift of this region led to the diversification of the rhubarb genus. The low-growing habit of R. spiciforme may be an adaptation to the damaging winds blowing at the great altitudes where it is found.

After the Second World War rhubarb had to compete with a growing range of imported fruit and fell from favour. The resurgence in rhubarb’s popularity has been driven by its new image, laden as it is with bioactive polyphenols, which are currently being investigated for anti-cancer, anti-inflammatory and other potential benefits. Like all good things, too much rhubarb over too long a period, as a purgative rather than a food, can cause problems. And don’t eat the leaves.

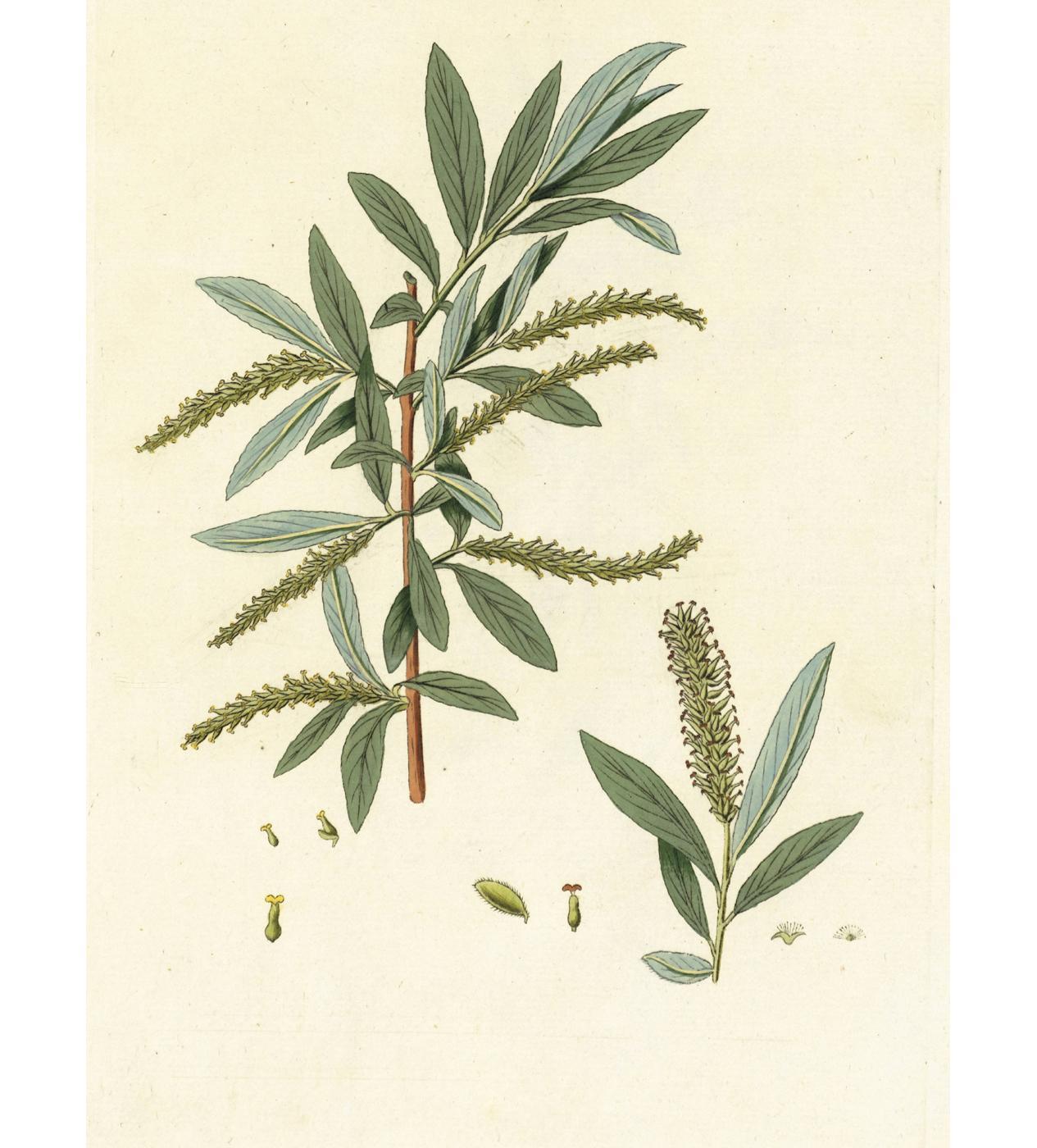

Salix spp.

Tree of Sorrow and Pain Reliever

There is a willow grows aslant a brook That shows his hoar leaves in the glassy stream.

Shakespeare, Hamlet, Act 4, Scene 7

Few trees have been more intertwined with human history than the willow. Its use in weaving baskets and making fences and hurdles is ancient, and continues as a reviving craft. The Salix genus of about 300 species, with numerous cultivars, is widely spread in the temperate regions of the northern hemisphere, though willows can also be found south of the Equator and in the colder reaches of the Arctic. They frequent river-edges, where their roots help prevent erosion.

The medicinal qualities of one species in particular, Salix alba – the name alba relates to the silvery-white underside of the leaves – have long been exploited by humans. The Egyptians, ancient Greeks and peoples of Southwest Asia all used it to treat fevers and pains, and inevitably many other complaints as well. The bark was generally ground and put into an infusion of wine or other liquid. It remained a mainstay in European therapeutics, and the 17th-century English herbalist Nicholas Culpeper recommended willow bark as a substitute for the more expensive Peruvian Bark. Both have a bitter taste, and Salix might have alleviated the fever, though it would not have cured the disease if it happened to be malaria. In 1763, an English clergyman, Edmund Stone, specifically singled out infusions of willow bark as a remedy for fever.

It continued to attract medical attention and in the 1820s two pharmacists, one French, Henri Leroux, and the other Italian, Raffaele Piria, independently isolated the active ingredient, salicin. Further work showed that when this is broken down in the body, one of the products is salicylic acid, demonstrated in the 1870s to be valuable in reducing the pain and inflammation of rheumatic heart disease. These were the early days of germ theory and the substance was thought to be an internal disinfectant, since salicylic acid can kill bacteria in the laboratory. It is now known that it works through other mechanisms. Another species, S. purpurea, also contains the essential compounds.

‘Aspirin’, which has an acetyl molecule added to the salicylic acid, was actually synthesized in 1853, but was only marketed (with great success) by the German pharmaceutical company Bayer in 1899. It had a long life as the frontline drug for the reduction of fever, headache and pain. Its manufacture no longer needs the willow bark; it is made from coal tar derivatives. Despite its place in the household medicine cabinet, aspirin would almost certainly have failed modern safety regulations governing the introduction of new medicines.

Samuel Copland extolled the virtues of Salix alba in Agriculture Ancient and Modern (1866). In addition to the familiar uses of coppiced wood as stakes and poles and for hurdles and baskets, he reported that people living near the Arctic dried the inner bark, then ground and mixed it with oatmeal as a flour in times of scarcity. In Russia it was reputedly planted and pollarded to mark the way for travellers across the Steppes.

More recent uses of willows include as biomass, and they are coppiced for fuel in Sweden and elsewhere. Many are very fast growing and strike easily from a fresh-cut branch. Their wood is used for charcoal and making paper, their bark for tanning; they provide excellent windbreaks and their environmental impact is widely appreciated. The weeping willow (S. babylonica), introduced to Europe from China, is a favourite ornamental. And while S. alba may not enjoy its former medicinal status, another variety of the species, caerulea, is used to make cricket bats. No other wood will do, and the sound of willow bat striking the leather of the cricket ball is a distinctive sign of summer wherever cricket is played.

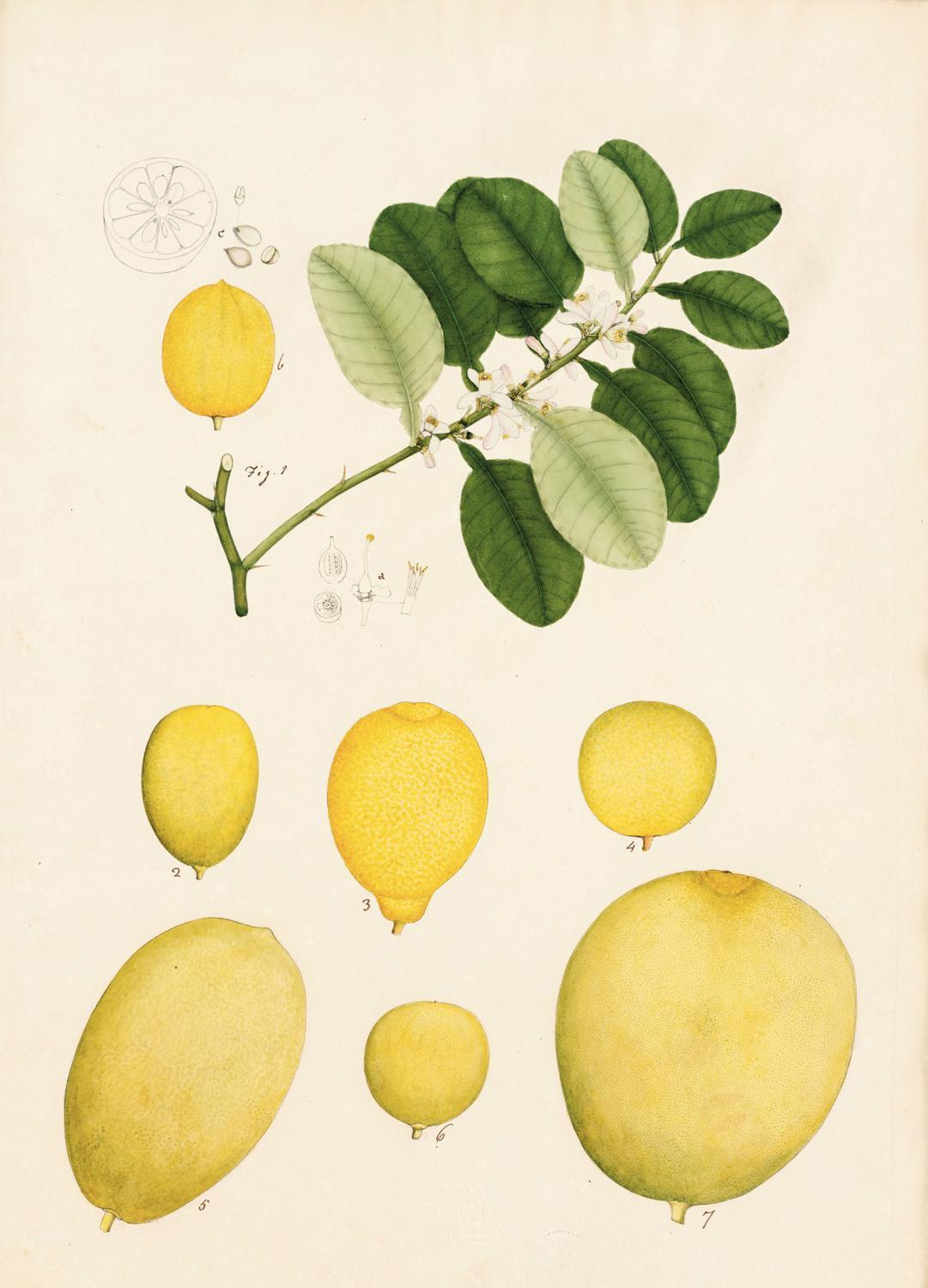

Citrus spp.

Agridulce como la naranja es el sabor de la vida.

[Sour and sweet like the orange is the taste of life.]

Spanish Proverb

Some of the varieties or species (he was undecided) of ‘sour lemons or limes’ of India drawn at the request of William Roxburgh, perhaps during his superintendency of the Botanic Garden in Calcutta (1793–1813). During his tenure, his Indian artists produced some 2,500 botanical illustrations. One set remained in Calcutta while the second came home to the Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew.

The oranges, grapefruits, clementines and lemons that we eat for breakfast, drink as juice or cook with may seem very familiar, yet several are of recent origin. Grapefruit (C. paradisi) was bred only in the 18th century, and clementines, a hybrid of the tangerine and an ornamental variety of the bitter orange, are a century younger. This is because the species of the genus Citrus are wonderfully fertile with each other, and the trees or bushes themselves are highly adaptable to human manipulation.

All citrus fruits originated in an area stretching from eastern Asia to Australia at a time (perhaps 20 million years ago) when Australia was still joined to the Asian continent. They have complicated historical genetic relationships, still not entirely understood, although the Australian lime (Citrus australis) is very old, and other citrus species have an extensive history in Asia, where they were appreciated for both their fragrant flowers and their fruit. One recent suggestion is that there are three basic citrus species, from which sprang the wide variety we enjoy: the citron (C. medica); the mandarin (C. reticulata); and the pummelo (C. maxima).

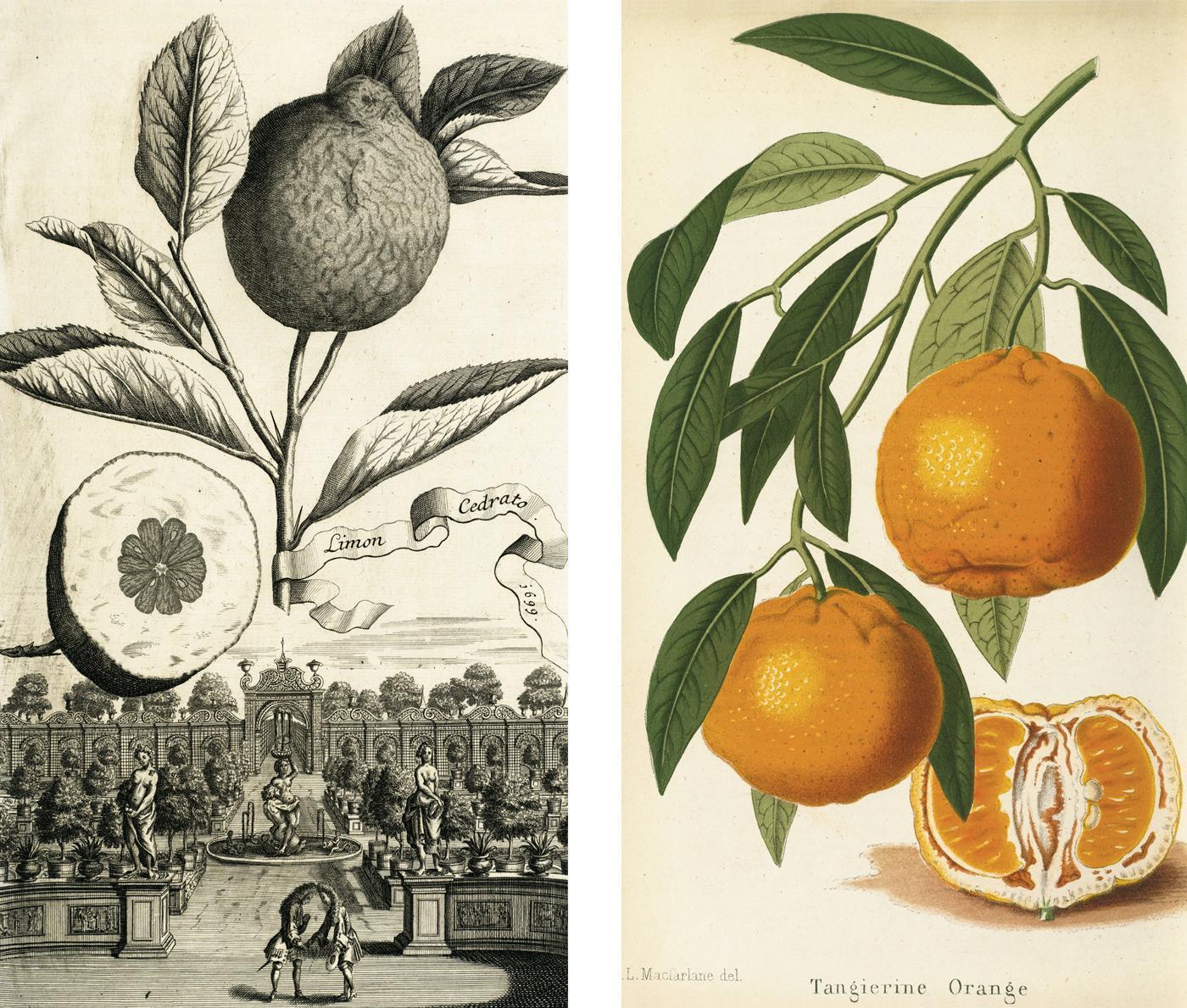

Citrus moved west after Alexander the Great discovered them in India in the 4th century BC, although the citron was known in Southwest Asia before 400 BC. This resembles a large lemon and became important in the Jewish Feast of the Tabernacles; Etrog, a small-fruited variety, is grown especially for the Feast. Although now only a minor member, citron has given its name to the whole genus, indicative of its historical importance.

Other citrus fruits, probably limes and lemons, arrived in Europe in the early Christian era, although they were still exotic and available only to the wealthy. The Arabs prized them and introduced bitter oranges, lemons and limes into areas they conquered, including Spain. Then, as now, citrus trees needed two things: plenty of water and no serious frost. This means that they require irrigation if grown in dry areas, and protection in climates subject to occasional frosts. As rich northern Europeans became fascinated with their taste and the delicious scent of their flowers, they constructed orangeries and large hothouses in order to grow them. The elegant Orangery at Kew Gardens, southwest London, was built when the gardens were still the private preserve of King George III. Unfortunately, the light levels were insufficient for successful citrus growing.

Left ‘Limon cedrato’ or citron. Johann Christoph Volkamer, a wealthy merchant at Nürnberg (Nuremberg), established orchards and an orangery for his extensive collection of citrus trees. These were recorded in his 2-volume Nürnbergische Hesperides (1708–14), with over 100 plates, in which botanical art met Rococo garden style.

Right The tangerine orange (Citrus tangerina): an easily peeled variety associated with the region around Tangiers in North Africa. It was commended in the 19th century by Mr Tillery, gardener to the 5th Duke of Portland, as the tastiest orange he had known grown in Nottinghamshire, in England. The Duke’s Welbeck estate had brazier-heated walls in its extensive kitchen garden and glass houses.

Although citrus fruits proved difficult to grow at home, British, Dutch and other northern European seafarers encountered them in their travels, and were grateful for them. Long sea voyages, accompanied by monotonous and nutritionally inadequate victuals, meant that scurvy was a major hindrance to European imperial and commercial aspirations. Scurvy causes bleeding from the gums and under the skin, weakness, diarrhoea and emaciation; it can kill. We don’t know who first recognized that citrus fruits could actually cure this dreadful disease, and that regular consumption could prevent it occurring in the first place. However, by the late 15th century, the value of eating citrus fruits in the cure and prevention of scurvy was mentioned, and some ships’ captains were aware of this before it became routine medical practice. In the mid-18th century the Naval Surgeon James Lind famously tested citrus along with other recommended remedies for scurvy in an early clinical trial. He found that lemon was especially effective, although it took another three decades before the British Navy made provision for the supply of limes or lemons to sailors.

Citrus fruits contain variable amounts of ascorbic acid, the vitamin that prevents (and cures) scurvy, which humans cannot make in their bodies. Ironically, the lime, which gave British sailors their nickname ‘limeys’, is a less reliable source than some other citruses, though many other fresh fruits and vegetables also contain it. The variable amount of ascorbic acid in foodstuffs complicated the evaluation of citrus fruits in the scurvy scenario, but the health-giving properties of the fruits are still prominent in modern marketing. From the 1980s, the Nobel Prize-winning chemist Linus Pauling advocated high doses of ascorbic acid for the treatment of the common cold as well as the prevention of cancer and cardiovascular diseases.

Sweet oranges (C. sinensis) were cultivated in Europe by the 15th century, and Columbus took them and lemons (C. limon) to the Americas on his second voyage. There they were grown on several Caribbean islands, as well as in Florida, which is still one of the centres of world production. California became Florida’s major North American rival, after groves were established there in the 19th century. Just a year after the transcontinental railway reached Los Angeles, a citrus grower successfully shipped a load of oranges back east. Other major producers include Brazil, several southern European countries and Israel. Sweet oranges are now grown principally for their juice, which modern methods of preparation and transport have made readily available.

Continuing crosses have increased the variety of citrus fruits on the market, which can now be purchased all year round. At the same time, intensive cultivation has inevitably brought with it the perennial problems of pests and diseases. Freak frosts in generally warm climates also affect the annual harvest, and protection via sludge pots (now often banned because of pollution) and spraying trees with water when frost threatens are the two major strategies of growers. Spraying relies on the fact that as long as water (rather than ice) is present on the leaves, the leaf temperature will not fall below the freezing point of water.

‘Hesperidium’ is the scientific term for the whole fruit, after the golden apples of Hesperides sought by Hercules, which were neither orange nor apple. If the juice and flesh (pulp) are what we most readily consume, the peel is just as valuable. The peels of various citrus fruits contain many oils that are widely used in soaps, perfumes and cooking. The bergamot orange is grown exclusively for the oils in its peel which give Earl Grey tea its distinctive flavour, and the peel of Seville oranges makes the best marmalade.

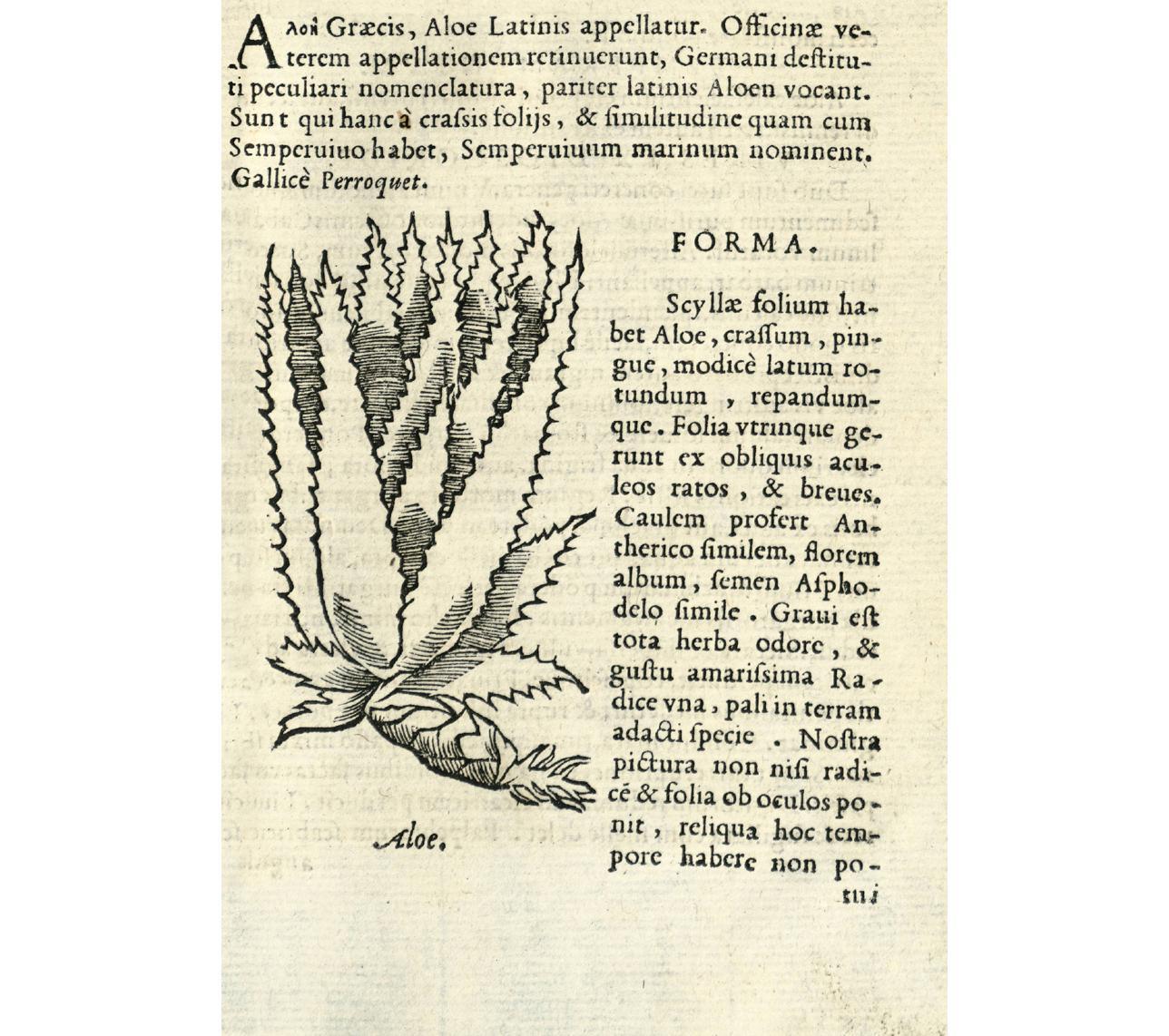

Aloe perryi, A. vera, A. ferox

The Succulent and Its Healing Gel

You ask me what were the secret forces, which sustained me during my long fasts. Well, it was my unshakable faith in God, my simple frugal life style, and the Aloe whose benefits I discovered upon my arrival in South Africa.

Mahatma Gandhi (letter to his biographer Romain Rolland)

‘De Aloe’ from Leonhart Fuchs’ De Historia Stirpium (1551), one of the great herbals of the 16th century, illustrated with fine-quality woodcuts. Fuchs may have grown his aloes in pots at the botanical garden he created as part of the university at Tübingen. In the 1st century AD, and further south, Pliny reported the use of special conical pots for aloes.

Medicinal aloes were so prized that Aristotle advised his one-time pupil Alexander the Great to take control of the island of Socotra in the Indian Ocean, where the best aloes (Aloe perryi) grew. Or at least that’s how the story goes. Perhaps the human worth of a plant might be measured by the quality of the legend it attracts.

Aloes are succulents, plants that have various adaptations to cope with aridity. The aloes’ modified leaves act as water storage organs during the dry season, and the liquid they contain, as well as the tissue, attracts herbivores – in southern Africa elephants have a penchant for them. Probably in order to deter such interest the leaves have protective prickles, and many species produce bitter-tasting chemicals including the aloins. The amount of aloin (and other bioactive products) varies from species to species, plant to plant, with age and season, and in response to damage. This can lead to inconsistencies in the quality of aloe products and is one reason why it has proved so difficult to assess their reputed medicinal benefits and gauge toxicity.

The name aloe is derived from the Arabic alloeh. Rather confusingly the same word was used for the commodity the plant yielded, aloes, in the form of shiny blackish bricks or lozenges. When a leaf is cut, latex is exuded from special cells just under the skin; this was heated and condensed until it solidified. The easily transportable lozenges could then be melted again as needed and were often combined with other drugs. The Egyptians used aloes as early as the mid-2nd millennium BC, though Hippocrates did not mention the drug. It entered the Roman pharmacopeia only in the 1st century AD – Pliny reported that the leaves of the Asiatic kind were applied fresh to wounds. This use is still promoted, although clinical evidence is equivocal. The best aloes, he said, came from India, for which we can read the Indian Ocean trade routes. He extolled it principally as a laxative, though listed many other situations in which it was effective, including against hair loss.

Wound healing and purging were the main uses of aloes, although it was recommended for numerous therapeutic, cleansing and moisturising tasks, internally and externally. Its popularity was especially strong in the Arabic medicine of the eastern Mediterranean, exported by the Muslim conquests. Over time the plants, as well as the condensed drug, were exported to the east as far as China and into Europe. Everywhere it gained popularity and filtered into the pharmacopoeias.

Aloe ferox, the ‘great hedge-hog aloe’, from Curtis’s Botanical Magazine (1818). This South African aloe grows to 2 m (over 6 ft) in height, with leaves reaching 1 m (3 ft) in length. Traditionally a few leaves are taken from multiple plants and arranged around a lined depression to collect the brown exudate dripping from the cut surface. Concentrated by heating and then dried, the resulting solid bitter aloes have been used locally for centuries.

Africa, especially the south, houses Aloe hotspots, with a fabulous diversity of species. At the continent’s southernmost tip, A. ferox was a long-standing indigenous favourite. Today it is the source of an important local industry as the demand for aloe products continues to expand; traditional ways of managing and harvesting leave the plant intact for further cropping. Africa’s output of A. ferox, however, is dwarfed by that of Aloe vera from Mexico, the southern US and parts of South America. A. vera came from the Arabian Peninsula, although quite where is unclear. It was taken to the New World by Columbus, and spread from the West Indies. Aloe latex and its products are not benign cure-alls, but recent studies do point towards a role in lowering blood sugar in diabetics and blood lipid levels in patients with an excess.

Dioscorea mexicana, D. composita

No woman can call herself free until she can choose consciously whether she will or will not be a mother.

Margaret Sanger, 1919

There are many pills, but only one is ‘the pill’. The oral contraceptive or birth control pill was known simply as this soon after its introduction in 1960. Widespread availability for unmarried women came too late for the freedoms of the ‘swinging sixties’, but it would in time offer unprecedented childbearing choices for sexually active women. The pill is unusual in that it is not taken to cure or alleviate sickness, but to prevent a natural process. The body’s reproductive hormones control a woman’s menstrual cycle through a delicate series of feedback loops. The pill’s daily dose of the hormone progesterone interferes with this and suppresses ovulation. The original source of the hormones used were plants – two non-edible species of Mexican yams known locally as cabeza de negro (Dioscorea mexicana) and barbasco (D. composita).

Research in the 1930s and 1940s involving steroids and sex and other hormones was exciting and full of medical promise. While biologists determined how these chemical messengers controlled many of the body’s functions, chemists tried to find ways of supplying large amounts at minimal cost, for research purposes but especially for therapeutics. Plants have steroids too and maverick organic chemist Russell Marker was the first to realize the potential of the Mexican yams. His genius lay in an uncanny ability to synthesize analogues of the complex organic compounds found in nature, provided he could find the right raw material. Impressed with Japanese work with the steroid diosgenin from yams, he put his energy into finding a cheap source of plant steroids.

With the help of botanists and knowledgeable locals, Marker’s team analysed some 400 plants collected during trips in the early 1940s to the southern US and Mexico. Marker became interested in the cabeza de negro yam. This large, coarse vine with heart-shaped leaves and huge tubers grew wild in the stifling forests of Veracruz, eastern Mexico. Marker persuaded a local shopkeeper there to find some tubers for him, and from this diosgenin-rich source he produced enough progesterone to warrant industrial-scale exploitation. As human steroids all share a similar basic structure, synthesis of one opened the way to the manufacture of other sex and adrenal gland hormones.

Dioscorea mexicana: its characteristic above-ground tuber is found in other yam species, notably the ‘elephant’s foot’ yam (D. elephantipes) of South Africa. Rich in saponins, this is also threatened by over-collection for garden specimens and by local people who use it medicinally.

In 1944 Marker set up Syntex in Mexico City, but left early in 1945. He had determined that the barbasco yam had a higher yield of diosgenin and reached productive size in about three years (cabeza de negro required six to nine years). Using this plant, Syntex chemists Carl Djerassi and Louis Miramontes improved the processing of the tuber and the means of producing large quantities of pure progesterone. They went on to produce an oral, rather than injectable, form of progesterone – norethisterone. Tested for its efficacy to treat menstrual disorders and miscarriage, its potential as an oral contraceptive became apparent. Clinical trials in Puerto Rico followed and Enovid was the first pill marketed.

Syntex, the pill and supplies of diosgenin established Mexico as the world’s leading producer of high-quality plant-derived hormones. There were many positives, but also negatives. Unemployed peasants collected the yams in the jungle, enduring hard conditions before selling them on to middlemen. Such collecting was unsustainable. Price increases in the 1970s, in part a result of the Mexican government nationalizing yam gathering, made other options such as total synthesis financially viable.

Catharanthus roseus

Delicate Flower, Powerful Treatment

This plant deserves a place in the stove [hothouse], as much as any of the exotics.

Philip Miller, 1768

Madagascar is a special island, home to a diverse, distinct flora and fauna. Some 80 per cent of its native plants lived nowhere else before being transported to other lands. This includes the Madagascar or rosy periwinkle. Popular as a tender bedding annual, it is pretty without being sumptuous, more bridesmaid than bride. Yet within its tissues the periwinkle contains the unique alkaloids vinblastine and vincristine that have changed the face of childhood cancers.

On its island home and elsewhere the periwinkle had also gained a reputation as a medicinal herb. In Jamaica ‘periwinkle tea’ was used as a remedy for diabetes. Insulin had transformed this disease, but was expensive and had to be injected. The efficacy of the periwinkle leaves was tested using a sample received from Jamaica in 1952 in the laboratory of Robert Noble at the University of Western Ontario in Canada. Effects on blood sugar and glycogen levels using oral preparations were disappointing. Fortuitously, along with blood tests for glucose Halina Czajkowski Robinson ran white blood cell counts on her own initiative. The results of her tests revealed that something in the periwinkle was suppressing the production in the bone marrow of these vital cells of the body’s defence system. In 1954 biochemist Charles T. Beer joined the team and four years later succeeded (after some 5,000 attempts) in isolating the ‘something’. It was an alkaloid named vinblastine, which could be tested in tumour cell cultures on the laboratory bench. Although Beer’s method of producing vinblastine would be patented, parallel work was underway at the giant pharmaceutical firm of Eli Lilly in Indianapolis, USA. Here they were conducting a sweep of analyses of plants for potential drugs and had heard about periwinkle and diabetes, this time from the Philippines.

Late in 1959 vinblastine moved from the culture dish to patients. It was made commercially available in 1961 (as Velbe) and joined in 1962 by the similar but more active alkaloid vincristine (Oncovin). In combination therapy, despite side effects, this became the bastion of the treatment of childhood leukaemias. Its use has been extended to some lymphomas and lung cancers, Kaposi’s sarcoma in HIV/AIDS and autoimmune conditions. The periwinkle drugs work as ‘spindle poisons’, interfering with the formation of the microtubules of the spindle, the apparatus in the dividing cell that helps move the chromosomes around during cell division.

The Madagascar periwinkle was first grown as an ornamental in France, at the royal gardens of Versailles and Trianon. Seeds from there were sent to Philip Miller at the Chelsea Physic Garden in the 18th century, who extolled their summer-long profusion of blossoms. Apart from its need for winter warmth, its cultivation requirements are easy to satisfy, and the periwinkle naturalized wherever it was taken in the subtropics and tropics.

Symbol of hope for these diseases, the periwinkle has also become something of an emblem for biopiracy too. Many deplore the exploitation of the knowledge and resources of the developing world by the developed. Madagascar, the evolutionary home of the periwinkle, seems to produce the best quality alkaloids, but the samples of periwinkle plants in this story were from elsewhere. Various countries today provide the raw material, which is needed in large amounts, but the rural Malagasy people who collect the wild plants or grow them on a small scale continue to receive poor prices. There is also a fear that global habitat destruction reduces the chances of finding other plants akin to this life-saving flower.