Quercus squamata is now known as Lithocarpus elegans and is no longer considered to be an oak. In the 19th century it was described as a large timber tree from the species-rich subtropical Garrow (Garo) mountains in northeast India; the wood was said to be lighter coloured than English oak, but equally strong and close-grained. The name may have changed but the functionality remains.

Whoever controlled the lands where the Cedar of Lebanon grew controlled access to this most valuable of trees and the bounty that its wood afforded. Much in demand as a durable and fragrant timber for Phoenician ships as well for construction, it provided a valuable commodity for exchange. Its resin, too, was held in high regard. Cedar wood thus sets the tone for Technology and Power, examining the material applications of plants and what benefits that might bring.

What cedar had done in the eastern Mediterranean, oak would do for various seafarers in Europe. Power at sea was matched by majesty at home. Oak provided the durability and strength to create many great churches and other buildings. Yew conferred power differently. It made stout hunting spears that have lasted long enough to date their use back some 450,000 years. The subtle difference in flexibility between sapwood and heartwood created the longbows that helped the English triumph at Agincourt in the 15th century. And yew’s biochemistry has yielded weapons of another sort – drugs to kill the rapidly dividing cells of certain cancers.

All these woods can also be used for furniture too, but there is always the shock of the new. When Europeans encountered the tropics they found huge trees, their growth stimulated by the moist, hot conditions, and untouched by loggers. These provided usable wood in dimensions hitherto unknown. Tropical hardwoods, mahogany in particular, became the wood of choice for furniture in the 18th century. Easy to work and inherently stable, its products were highly desirable. By the time the fashion for mahogany had run its course, the future of the tropical woodlands was already threatened.

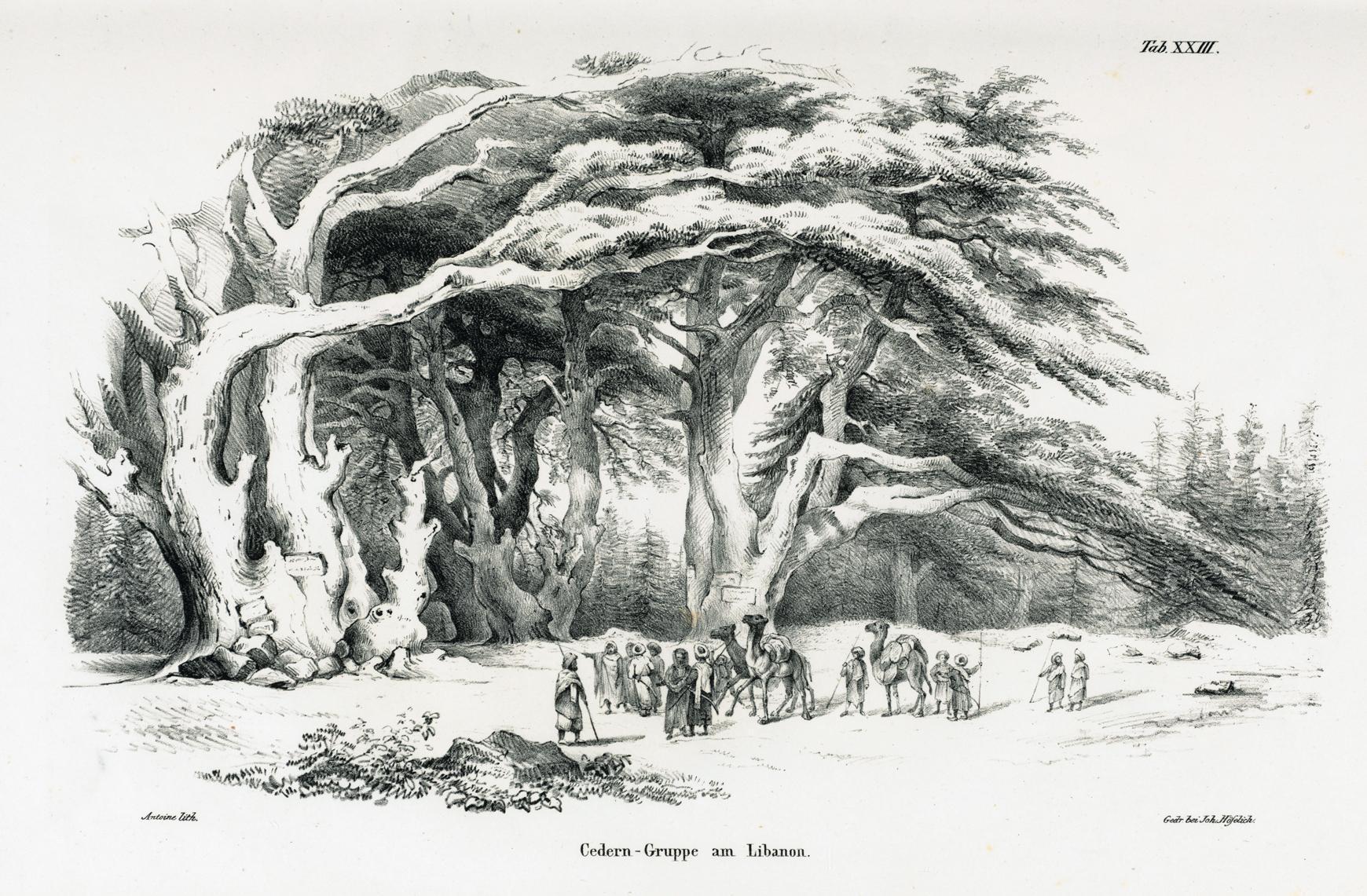

Left The majestic Cedar of Lebanon (Cedrus libani), with details of the needles and cones – male above, female below – and winged seeds, which are released from the mature cones.

Right Carding the cotton, an essential stage in its preparation for spinning, as recorded by Pierre Sonnerat in his Voyage aux Indes orientales et à la Chine (1782).

From tree to grass – the amazingly versatile bamboo. Spread through the temperate and tropical world, these perennial, woody, hollow-stemmed plants have proved to be extraordinarily adaptable in human hands. Their stringy strength lends them to house building in Japan. Lashed together lengths of the giant bamboos created buoyant rafts. Twisted bamboo reminiscent of a steel cable acted like one in Chinese suspension bridges. From baskets to fabric, bamboo fibres have been woven into objects and clothes as this plant continues to meet our needs.

Today bamboo can be mixed with other, older fibres such as cotton, hemp and linen made from flax. Wool from animals is also used of course, but vegetable fibres offered something different. From these came string, cord and cloth, clothes and sails, paper and furnishings, the industries of spinning and weaving, high fashion and the hangman’s rope. All these plants contribute the raw materials of our material world.

Cedrus libani

Foundation of the Phoenician Empire

My friend up to now the high-grown cedar’s tip would have penetrated to heaven. Make from it a door whose height will be six-dozen yards.

Epic of Gilgamesh, Tablet V

The Phoenicians were famed merchants and shipbuilders. Their craft, made of timber from their great cedar groves and equipped with a single sail and oars, sailed throughout the Mediterranean using direct open-sea routes. As well as building their ships from cedar trees they also traded in the highly prized cedar logs.

Towards the higher reaches of the steep rocky mountainsides of Lebanon and Syria are small stands of majestic conifers, the Cedars of Lebanon, which can grow to some 40 m (130 ft) in height. They are the descendants of trees which, along with cypresses, junipers and other pines, once clothed the slopes of the Lebanon and Taurus mountains in evergreen beauty. If modern Turkey is the best remaining source, it is Lebanon that has claimed this iconic tree as its national symbol.

Measured on a geological timescale, the Cedrus genus is a relative youngster. It evolved in the early Tertiary period (65 to 55 million years ago) and fossilized remains are hard to distinguish from the living species. In terms of human history it was a crucial tree for the ancient civilizations that occupied the Levantine coast. Cedar wood provided the late Bronze and Iron Age Phoenicians with a most valuable commodity, which their neighbours – the Egyptians, Assyrians, Israelites, Babylonians, Persians – would seek to attain by trade, demand as tribute or take by force. The construction of a coastal railway during the First World War and its subsequent fuelling reduced much of what then remained of Lebanon’s significant stands of cedar to ash. This was a sad finale for trees once so prized that their wood was used for the coffins of Egyptian pharaohs.

Cedar’s essential oils imbue it with a highly desirable scent. It is also an enduring one, as archaeological finds of still fragrant wood attest. Other chemicals in the resin impart good protection against wood-boring insects and microbial decay. Unlike the spreading contours of landscaping cedars planted in European parks from the 18th century onwards, those growing more densely on home soil were taller and straighter. They yielded impressively long runs of usable wood much prized in the ancient world for the construction of major buildings and ships.

An ancient cedar grove in Lebanon. The Forest of the Cedars of God (Horsh Arz el-Rab) in northern Lebanon is part of a UNESCO World Heritage Site that celebrates and conserves the ancient lineage of Cedrus libani. The trees may be relics of populations of the Cedrus genus that ran along the mountain ranges here before the Tethys Sea closed and became the Mediterranean.

Solomon famously sought cedar for his temple and royal palace in Jerusalem. He negotiated with Hiram, king of Tyre, for timber and skilled woodworkers, offering in return silver and vast amounts of olive oil and wheat. When the temple of Amun-Ra wanted cedar for a new sacred barge for the god in the 11th century BC, Wen-Amon, a senior temple official, sailed from Thebes to the Phoenician city of Byblos. Egyptian gold, silver, linen and 500 rolls of papyrus were the price.

The Phoenicians were master shipbuilders. Their slow but capacious merchantmen sailed the breadth of the Mediterranean. Famed for their length, cedar wood planks (and masts) offered strength and flexibility too. Specially thickened cell walls are laid down on the underside of the trunk, which in life help to keep the trunk vertical against the heavy pull of the branches. Such dense wood absorbs less water when immersed, aiding the water-resisting qualities of the resin. In such ships the Phoenicians exported their luxury goods – carved ivories, jewelry made from precious metals – and traded in raw materials such as copper ingots, towing behind them the prized cedar logs from home port to distant destination.

Quercus spp.

Great oaks from little acorns grow.

Late 14th-century English proverb

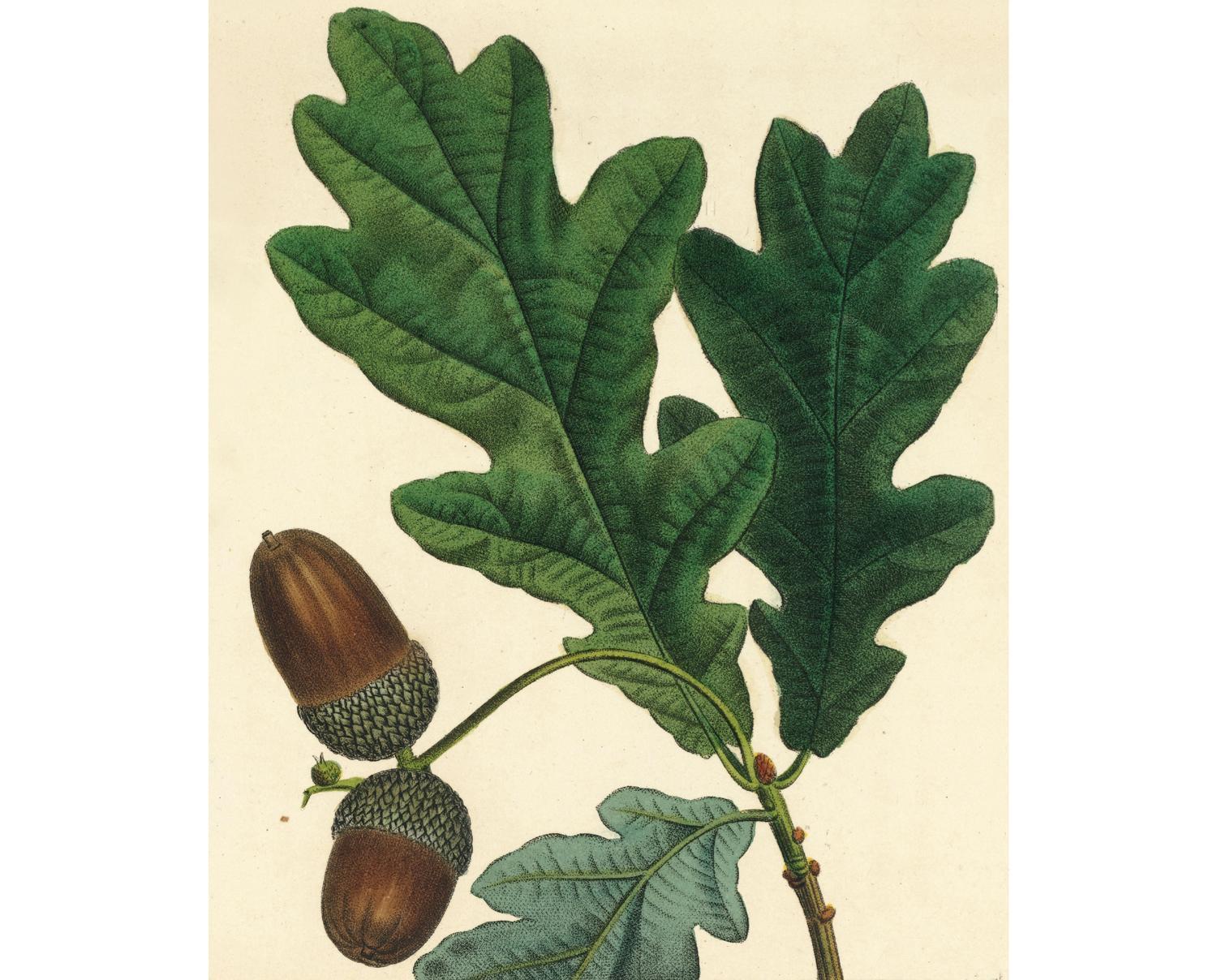

Leaves and acorns of the European white oak, Quercus pedunculata, from The North American Sylva (1865). It can take 50 years before a tree produces acorns; then, with the assistance perhaps of a helpful squirrel or jay, it takes two years for a small shoot to develop from a buried acorn, since the root system is the sapling’s priority.

Quercus (oak) is a large genus of up to 500 species, distributed mainly over the northern hemisphere, but with a native species in the Colombian Andes. The trees can live from sea level to as high as 4,000 m (over 13,000 ft) and come in a variety of guises including some evergreen and semi-green species, but it is the tall, stately deciduous trees that have been most prized. Slow-growing hard woods, they generally have thick, gnarled bark, rich in tannins. These naturally occurring chemicals exploited for preparing or tanning leather and maturing wine also make the wood especially good as a building material, as they deter insects and resist rot. The thick-walled fibrous cells of the oak’s core give it strength.

Oaks probably originated in Asia and were widespread 55 million years ago; their modern distribution reflects the ecological and climatic changes that have occurred during recent geological periods. They are wind-pollinated, and germination, as with many plants, is a hit and miss affair. Squirrels often help to distribute the acorns, hiding them in the ground and then forgetting where they left them (or meeting with an accident). Most oak species need temperate weather and relatively rich, moist soil. When conditions are favourable, individuals can live for several hundred years and reach enormous sizes.

Different species have been exploited for a variety of uses. A favourite was Q. robur, native to Britain and much of northern Europe. The material of choice for ships until the coming of metal hulls, it helped create British supremacy at sea. Several characteristics were needed for wood for shipbuilding: large trunks from which to hew timber, and malleable planks that were light and watertight. Oak had all these. Although it was dominant in British forests, such was the demand for ships, houses, furniture and firewood that much had to be imported from Scandinavia and other Baltic countries from the 17th century. The most common American species, Q. alba, the white oak, helped make the fortune of the Massachusetts Bay Company, which shipped timber home in the ships that brought settlers across the Atlantic. Another American species, Q. virginiana, the ‘live oak’, was considered the most durable of all, although it is less commonly used now.

Two East Asian oak species, with their leaves, acorns, bark and wood: Quercus aliena (right), oriental white oak, a useful timber tree; and Quercus variabilis, Chinese cork oak (left), which has lower yields but similar characteristics to European cork oak, with cells coated in a waterproofing wax.

Yet another species of oak has a special place in the affections of wine lovers: Q. suber, the source of cork. The bark of this semi-evergreen tree is especially thick and the ancient Romans used it in a variety of ways: for insulation, shoe soles, anchor floats and to stopper bottles – all still familiar today. The bark itself is probably an evolutionary adaptation against fire; it can be stripped every ten years, after the bark has regenerated, and the tree can live for 100 years or more.

Although acorns are edible (after leaching out the bitter tannins), and were a staple of many Native Americans until the late 19th century, especially in California, they are not much consumed today. However, they still form the basis of food for pigs in Italy and Iberia, from which famous hams are made.

Taxus baccata, T. brevifolia

Medieval Longbows, Modern Medicine

We few, we happy few, we band of brothers.

William Shakespeare, Henry V, Act 4, Scene 3

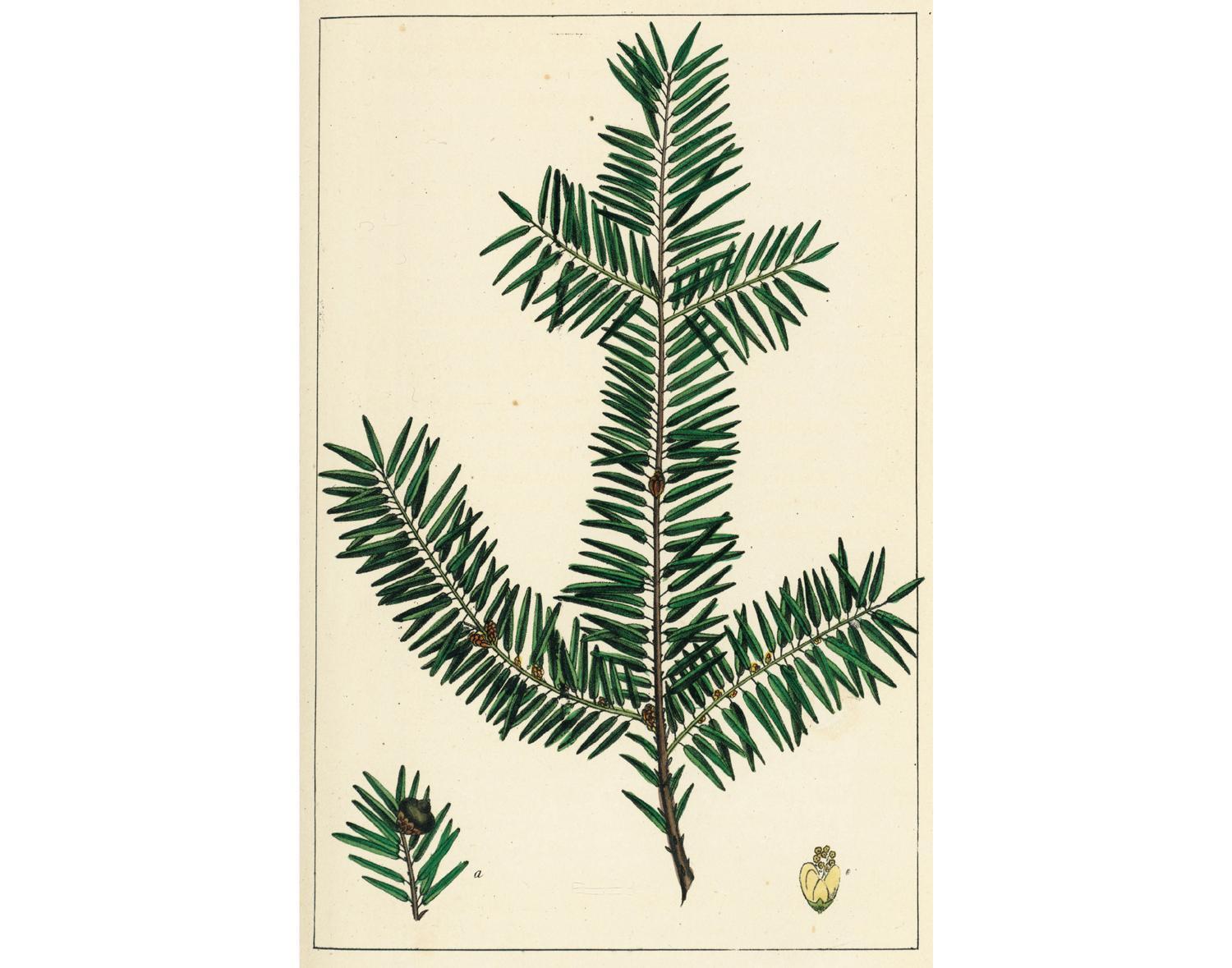

A sprig of Taxus brevifolia, which grows in the mountains of the western coast of North America from southeast Alaska to northern California. Native Americans used the wood for canoe paddles, bows and spears. Until the development of taxol, the forestry industry regarded yew as a nuisance, cutting and burning these ancient trees of the understorey.

On the morning of St Crispin’s Day, 25 October 1415, an English army led by Henry V faced that of France under Charles VI. By the end of the day Henry was victorious and the legend of Agincourt had begun. The English were not as outnumbered as the old chronicles would have it, but had far more archers equipped with their longbows made of English or European yew (Taxus baccata). It was these devastating weapons, strategically deployed, that made the difference.

Yew is an ancient material of aggression. Hunting spears are among some of the most ancient wooden artifacts discovered. A yew spear tip from Clacton-on-Sea, Essex, England, dates from around 450,000 years ago. A spear lodged between the ribs of a mammoth in Lower Saxony, Germany, is some 90,000 years old. Ötzi the Iceman carried an unfinished yew bow on his final journey in the Ötztal Alps, on the border of Italy and Austria, over 5,000 years ago.

By the reign of Henry VIII of England the longbow’s heyday was waning, but it still had a presence. Recovery of Henry’s warship the Mary Rose, which sank in 1545, has yielded a considerable shipment of yew bows and staves. The quality of the wood indicates that it was imported European or perhaps western Asian timber. Venetian merchants who controlled so much of the trade at the time sourced the wood. A specified number of staves were set as a tax on each barrel of wine imported into England.

Other woods were also used for bows, but yew is special. If the bow staves are cut radially from a length of even, straight yew timber, the result has two natural layers. The pale sapwood from just under the bark forms the flat outer layer, away from the archer; it resists being put under tension. The rounded belly of the bow is the heartwood layer, which resists compression. This resistance is stored as tremendous energy as the archer draws the bow – energy that propels the arrow upon release. Strong and amazingly elastic, the water-conducting cells of yew wood – tracheids – have a helical thickening that acts like a series of coiled springs.

Yews are long-lived trees with remarkable powers of regeneration, but the need for bow staves took its toll. So too did the clearance of forest for agricultural land. Some four hundred years after the Mary Rose, and across the Atlantic Ocean, the Pacific yew would face similar pressures, but this time it involved metaphorical warfare between cells of the body.

In 1962 bark was stripped from mature yews of Taxus brevifolia in Washington State and screened as part of a large project to harness the potency of plant products as cancer drugs. Once the active principle had been isolated and its structure and mode of action were determined, clinical trials were run. Thirty years after the bark had been harvested, in 1992, taxol (trademarked as Taxol® in 1994) was licensed for advanced, refractory ovarian cancer. Today variations on the original drugs are also used to treat forms of breast, lung, head and neck cancers, and the AIDS-related Kaposi’s sarcoma.

The taxol is found in the bark of mature Pacific yews, a large amount of which is needed to produce a small quantity of the refined drug; obtaining the bark meant killing the tree. In 1990 after the realization that clinical success would lead to huge demand, environmentalists joined with the American Cancer Society and two key scientists of the taxol story to call for sustainable exploitation of the yew by having it listed as a threatened species. The petition failed, but the Pacific Yew Act went some way to protecting the trees. Since then part-synthesis of taxol has made the raw material go further. Means of producing drugs from clippings, twigs and needles, including from European yew, and the use of plant cell cultures have also been developed. Sadly, exploitation of the Himalayan yew (Taxus contorta) for taxol in northwest India and western Nepal has led to a 90 per cent decline in the number of trees. It is now listed as an endangered species on the IUCN’s Red List.

Linum usitatissimum

Love is like linen often changed, the sweeter.

Phineas Fletcher, Sicelides (performed 1614), Act 3, Scene 5

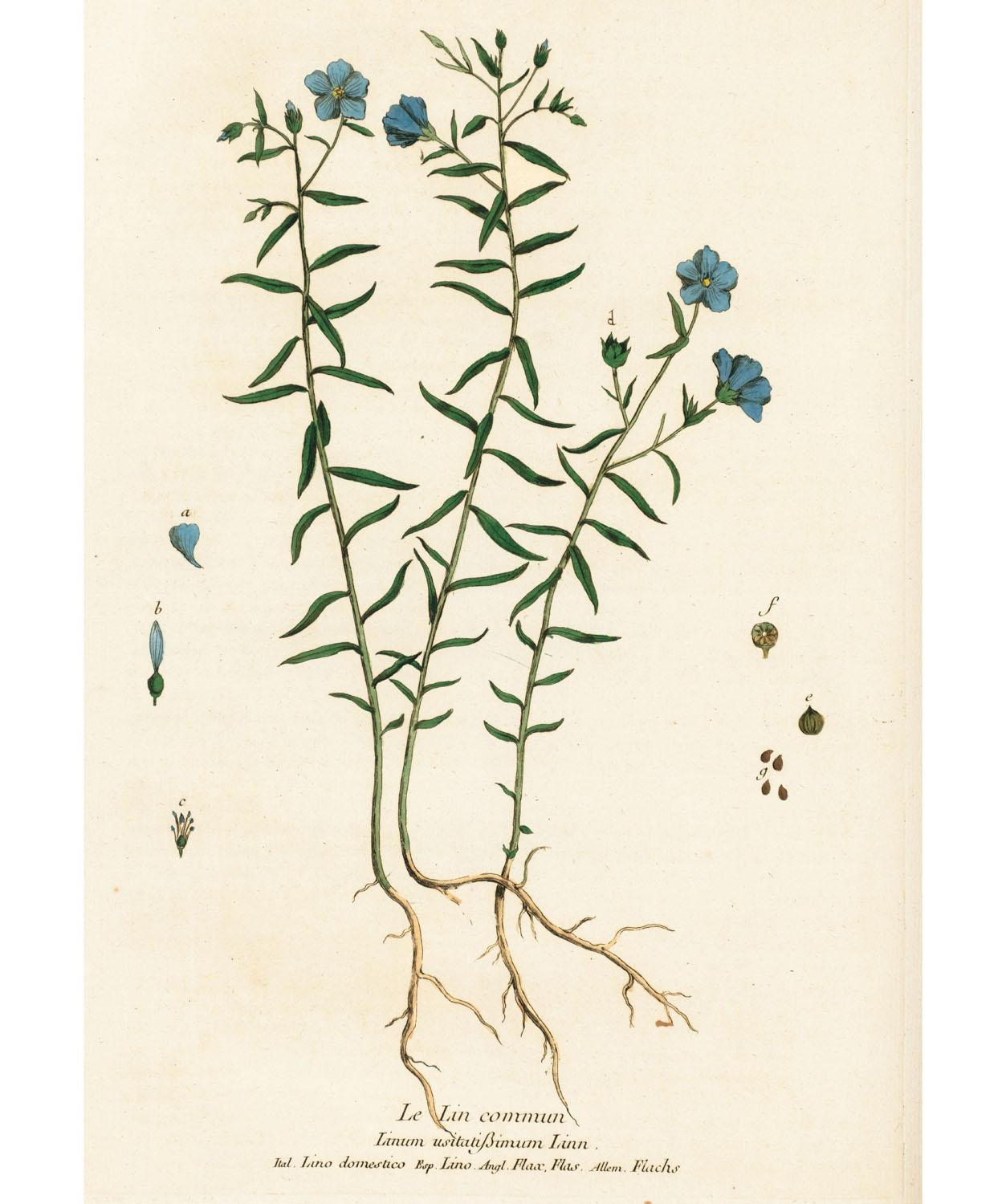

Flax has clothed humanity since at least the 4th millennium BC, though it was brought into the tilled field initially for its oil-rich, edible seeds. Probably domesticated from pale flax (L. bienne) about 8,000 years ago, its consumption is still older.

A key event in the domestication process appears to have been a genetic one that increased the unsaturated fatty acid content. Exposed to air, linseed oil slowly oxidizes and solidifies. Applied to densely woven linen, it strengthened ancient body armour. The same principle allowed pigments mixed with linseed oil to dry in layers when painted on to linen canvases. And what served high art also protected woodwork against the elements. In the 1860s Frederick Walton developed linoleum or ‘lino’ flooring by building up layers of oxidized linseed oil mixed with cork or wood dust on a fabric backing. After the discovery of germs in the 1880s, housewives were encouraged to throw out their carpets and lay linoleum. It was easy to clean and the linseed oil was also touted as an antibacterial agent. Back in fashion after being overtaken by vinyl in the 1950s, lino is now a ‘green’ product.

Compared to the oil plants, fibre-producing flaxes are taller (around 1.2 m/4 ft) and leaf only at the top. Linen was both a utility and a sacred fabric in ancient Egypt. Easily bleached and robust enough to stand frequent washing, pure white linen was worn by temple priests. Egyptian tomb paintings of the early 2nd millennium BC show flax being turned into linen. Processing the plants involves first retting (rotting) in water and then scutching (beating), releasing the bast fibres (just beneath the outer layer) for spinning and weaving. Flax fibres were made into string, rope and sailcloth (flax is about twice as strong when wet) as well as cloth to be worn.

In cooler northern and western Europe where flax grew well, linen made a useful layer beneath wool, being smooth on the skin and absorbent. Cotton and silk were pleasing, but prohibitively expensive outside their native regions. Linen was woven in the home for domestic use, and in the urban prosperity of the late Middle Ages high-end linens in an expanding range of styles and weaves were traded. From bed-sheets to altar-cloths, fine linen found a place.

More linen on the market meant more waste cloth at the end of its use. The technique of making paper from rags completed its slow journey from China to Europe via Muslim Spain in the 12th century. From the 16th century onwards, various centres of linen weaving – Bruges, Antwerp, Belfast – developed distinctive fabrics and reputations, while Russia grew much of the raw material. Trade and war at sea increased the need for both sailcloth and sailors’ slops. Linen found new uses as warfare changed. In the First World War, linen held the ammunition on machine gun belts; waterproofed it covered aircraft frames.

Linen’s failing perhaps is its inelasticity which makes it crease easily. The advent first of cheap cottons and then synthetic fabrics caused a precipitous decline in linen’s place in the clothing market. New blends, expensive price tags and rarity value have created a new aura around this ancient cloth. And flax foods are in fashion again, marketed for their alpha linolenic acids, which the body converts to omega 3 fatty acids thought to prevent cardiovascular disease.

Hans Christian Andersen’s fable of metamorphosis, The Flax (1843), takes this most useful of plants on a journey from field to fabric, from ragbag to paper and a final immolation in the fireplace. Cheerful stoicism might be Andersen’s intended message, but he neatly captures Linum usitatissimum’s utility.

Cannabis sativa

… three merry boys are we,

As ever did sing in a hempen string

Under the Gallows-Tree.

John Fletcher (with Ben Jonson & others), The Bloody Brother (c. 1616)

Planted as an annual, cultivated hemp plants can reach 5 m (over 16 ft) in height. From these tall stems come the bast fibres used for making textiles and paper, as well as inestimably useful string, cordage and rope, while the seeds yield an edible oil. Fibres from different plants have been referred to as ‘hemps’, but the real thing comes only from Cannabis sativa. Shorter and leafier varieties of the same plant are the source of psychoactive cannabinoids. These are concentrated in the female flowers, which, along with nearby leaves, are processed as hashish and marijuana.

Both the stem fibres and the cannabinoids have been used for a very long time in the plant’s homelands of Central and northeastern Asia. Chinese shamans employed the narcotic properties for medical purposes and the mind-altering effects. Knowledge of these uses may have spread westwards from China into India or may have arisen independently. Neolithic pottery from China, the ‘land of mulberry and hemp’, may well bear the imprint of hemp cloth. Mulberry – the food of silkworms – clothed the rich, while the poor made do with hemp. Under Confucian influence filial duty required surviving children to mourn their parents in hemp clothing, regardless of wealth. Han dynasty China (206 BC–AD 200) witnessed the paper-making revolution, using new and recycled hemp fibres (clothing and fishing nets) and mulberry bark.

After the plant’s introduction from Asia, hemp rope and cordage appear to have been taken up quickly in the Mediterranean during the Classical period before spreading inexorably westwards. Trade, exploration and conquest all relied increasingly on hemp as ships increased in size and complexity. Hemp (and linen) sails and rigging help propel the ship; sailors slept in hammocks of hemp canvas. Tremendous hawsers towed ships and hemp ropes anchored them, while a hempline gauged the water’s depth.

Early settlers in Virginia in the New World were obliged to grow hemp, the land and climate being suitable. Much later, American ‘duck canvas’ shaded the covered wagons that headed west to open up the country in the 19th century. But it was Russia that met the growing naval demands. Peter the Great saw the opportunity to turn some of Russia’s vast land and its serf population to the cultivation of hemp. This was hugely successful, and hemp became a major export crop.

The hemp plant, Cannabis sativa, is the source of many useful products as well as a narcotic. Ropes made from the strong stem fibres were crucial to sailing ships before synthetic versions and were tarred to prevent deterioration. When they did wear out, they were unpicked and the resulting oakum was used to maintain the caulking on hulls and deck planks. The unpleasant task of picking oakum was assigned as a naval punishment.

Hemp was crucial until the end of sailing ships and the rise of synthetic fibres. Its modern history has been dominated by its use as a narcotic, which has seen its growth and consumption outlawed. Varieties with low THC (tetrahydrocannabinol) are now being grown commercially, as hemp oil and seed make a health-driven comeback and the fibre’s green credentials are increasingly appreciated.

Gossypium spp.

Cotton is King

David Christy, 1855

The ubiquitous popularity of jeans ensures that worldwide demand for cotton remains high. It comes at a price, however, as modern methods of growing use large amounts of fertilizers and pesticides, mostly petroleum-derived, as well as a lot of water. In warm climates cotton is a perennial and can grow into a tree, but it is generally treated as an annual, when it is a large shrub of up to 2 m (over 6 ft) high. It needs rich soil, with plenty of rain in its growing season and a dry spell for harvesting. Of the around 50 species of the genus Gossypium, only four have been exploited for the plant’s fibres, which are found in the ripe seed pod or boll. Two New World species, G. hirsutum and G. barbadense, were used in pre-Columbian times; two Old World ones, G. arboreum and G. herbaceum, were also long prized.

The origin of the two Old World species is obscure, as their wild ancestors are not yet identified, but they probably came from Africa. Archaeological evidence for cotton in the Indian subcontinent dates from about 2500 BC. The Greek historian Herodotus described both the plant and Indian weaving of the strands; Indian writings mention it even earlier. The word ‘cotton’ is of Sanskrit origin. The Arabs introduced cotton to Sicily and Spain as they expanded their empire from the 8th century. However, European weaving and spinning techniques did not match those achieved in India, where muslins and chintzes of great delicacy and beauty were produced. Most early European cottons were actually fustians, a mixture of cotton and flax.

The flowers, ripening boll and seeds of Gossypium religiosum. As the handwritten notes testify, this South American cotton has been renamed several times. William Roxburgh commissioned this drawing in India, where the plant had gained a reputation for being cultivated by mendicants or found near temples.

New World cotton had already established itself in pre-Columbian societies. G. barbadense was native to Peru, where it was an important trade commodity between coastal communities, which needed it for fishing nets, and upland ones, where it was grown. In the 1st millennium BC the Paracas culture in Peru created elaborate textiles from camelid wool woven with cotton. ‘Egyptian cotton’, although now widely grown there, is actually the New World species barbadense. G. hirsutum was probably domesticated several times, but especially in Mesoamerica. The Spanish invaders in the early 16th century abandoned their scratchy woollens and linens for the softer cottons that the Aztecs wore. This species now accounts for almost 90 per cent of world cotton production.

A woman’s festive cotton dress from Ethiopia. Although Gossypium herbaceum enjoyed a long history of exploitation in Ethiopia, most commercial cotton grown there is now from the New World species and hybrids. More drought-tolerant, the local species may provide genetic material for new hybrids for this thirsty crop.

It took a while for cotton to become common in Europe, but when it did it transformed the textile industry. And since cotton is much easier to wash than wool or linen, it also had important consequences for cleanliness and public health. Originally most European cotton was imported in its raw state from India, where the East India Company enjoyed a monopoly. In the 18th century, innovations in harnessing power and machines to separate boll and seed and for combing and weaving the fibres revolutionized cloth production in Lancashire in the north of England.

American ingenuity also improved cotton processing. Eli Whitney’s cotton gin of 1793 allowed the much quicker mechanical separation of the fibres from the seeds in the boll. These and other developments brought the price of cotton fabrics down, which in turn stimulated demand. The United States began to rival India in supplying the commodity. Climatic conditions were favourable in the southern states, where large-scale cotton growing began in Tennessee in 1807 and soon spread. African slaves supplied the labour in the plantations, continuing the inhumane strategy that had given sugar cane its place on world markets. American exports to Britain increased hugely by 1853, much to the detriment of India.

The American Civil War (1861–65) disrupted the supply of cotton, a gap that India only partially filled. It led to unemployment in the Lancashire mills and divided British sympathies about the War, despite the fact that slavery had been one cause behind the conflict. The defeat of the South ended slavery and punctured the old plantation system, but didn’t stop cotton monoculture there, and with it the seemingly inevitable problems of pests and diseases. From the late 19th century the worst of these was the boll weevil, the female of which lays its eggs on the cotton plant’s buds.

The ongoing struggle between insect and agribusiness has involved pesticides and genetically modified (GM) plants. Between these and chemical fertilizers, as well as heavy use of water, cotton has come in for much criticism from environmentalists. Demand remains high, however. Cotton seed and its oil have myriad uses, from animal food to paints. Recycled fibres are used in the paper for American currency. Short fibres go into making cellulose used in explosives, shoes, handbags and bookbindings. Cotton products show up in ice cream and X-ray film, in lacquers and make-up. It is not only jeans that fuel world consumption.

A plant and seeds of Gossypium neglectum, a synonym of G. arboreum. Although it is not certain where this Old World ‘tree cotton’ was first domesticated, it was developed by the Indus valley cultures and the resulting varieties dominated cotton production in Asia before the introduction of New World cottons.

Bambusoideae

Versatility and Strength in a Stem

Labourers are obliged to pare their nails, but people of quality let them grow … and at night put little cases of bamboo on them.

Peter Osbeck, 1771

The tip of a bamboo shoot and delicate leaves on a Japanese block of lacquer ware. Bamboo is frequently depicted in East Asian art, both for its symbolism and the overlap with calligraphy techniques.

When Europeans and North Americans encountered the material culture of the bamboo-rich countries of China and Japan in the 19th century they were astonished by the multiplicity of uses to which the plant’s hollow stems were put. Understanding this technology provided a window on to these societies – bamboo substituted for much that was made of wood and metal elsewhere. It could be said that tropical and subtropical Asia was profitably living in a ‘Bamboo Age’.

Today there is an increasing realization of the economic potential of the world’s fastest growing ‘woody’ plants (they are not true wood). Phyllostachys edulis has been recorded as putting on 120 cm (almost 4 ft) in 24 hours during its maximum growth period, and it can reach up to 28 m (92 ft), yielding stems for the construction industry and fibres for textiles, as well as edible shoots when young.

Bamboos are broadleaved grasses (Poaceae); as forest dwellers, they are the only major grass lineage to have diversified in this environment. There are some 1,400 species (in around 115 genera) identified worldwide. They fall into three tribes: Bambuseae and Arundinarieae are the major ones, while Olyreae live mostly in the Americas. Some bamboo species are difficult to study because of their infrequent flowering. In 1912 specimens of P. edulis flowered in Nakasato, Japan. Seeds were planted in Yokohama and Kyoto, and although separated by 350 km (217 miles) the resulting culms all flowered in 1979 (such gregarious behaviour is known as mast flowering), completing their 67-year lifecycle. The estimated time taken by P. reticulata from seed to flower is 120 years. Bamboos also reproduce vegetatively by underground rhizomes, which allows their rapid increase. There are both ‘runners’, which expand horizontally beneath the soil and send up new shoots, and ‘clumpers’, budding new culms from the sides of the primary plant.

Such diversity of species and bounty of growth are matched by the richness of use, aside from the simply culinary (both as food and the chopsticks to eat it with). Split stems can be woven, and a sheet of bamboo matting can be made into the side of a house or a hat. Baskets might seem commonplace, but the ability to contain and carry is fundamental. Poultry can be taken to market and fish caught in traps; trays hold silkworms. Twisted into cables, bamboo fibres can be combined with whole culms to bridge rivers, while bamboo rafts float below. Bamboo can carry water as well as cross it: as irrigation pipes and water wheels, buckets and cups. A simple pole over one shoulder carries a suspended load on each end, two poles a sedan chair. From outdoor to indoor furniture, the house itself, the temple and the scaffolding for larger buildings, all are made of bamboo. It is used to write with and on – first on split culms and then paper. The giant panda requires none of these, but must simply eat huge quantities of bamboo and have a large enough range to move on when, after flowering, plants of some species die away.

Part of the culm (stem), leaf and sheath of the impressive 5-m (16-ft) tall Phyllostachys castillonis. Bamboos are giant grasses of incredible versatility. Construction of China’s Great Wall (begun in the 5th century BC) and Grand Canal (5th century AD) both benefited from the bamboo wheelbarrow, which with a sail could carry 165 kg (365 lb).

Swietenia spp.

Of all woods, mahogany is the best suited to furniture where strength is demanded. It works up easily, has a beautiful figure and polishes so well that it is an asset to any room.

Thomas Sheraton, 1803

A mahogany tripod table of mid-18th century design – it was extremely fashionable, with its characteristic piecrust rim. Originally, such tables were fashioned from a single piece of wood, but in reproduction pieces the rim is applied afterwards. In fact this is a toy table, but even in a doll’s house, only the best would do.

It is easy to see why mahogany has long been favoured as a wood of fine furniture, panelling and woodwork. Its hue (after it dries) is so rich and distinctive that it has become an actual colour, its grain is exquisite, and it is tough and durable.

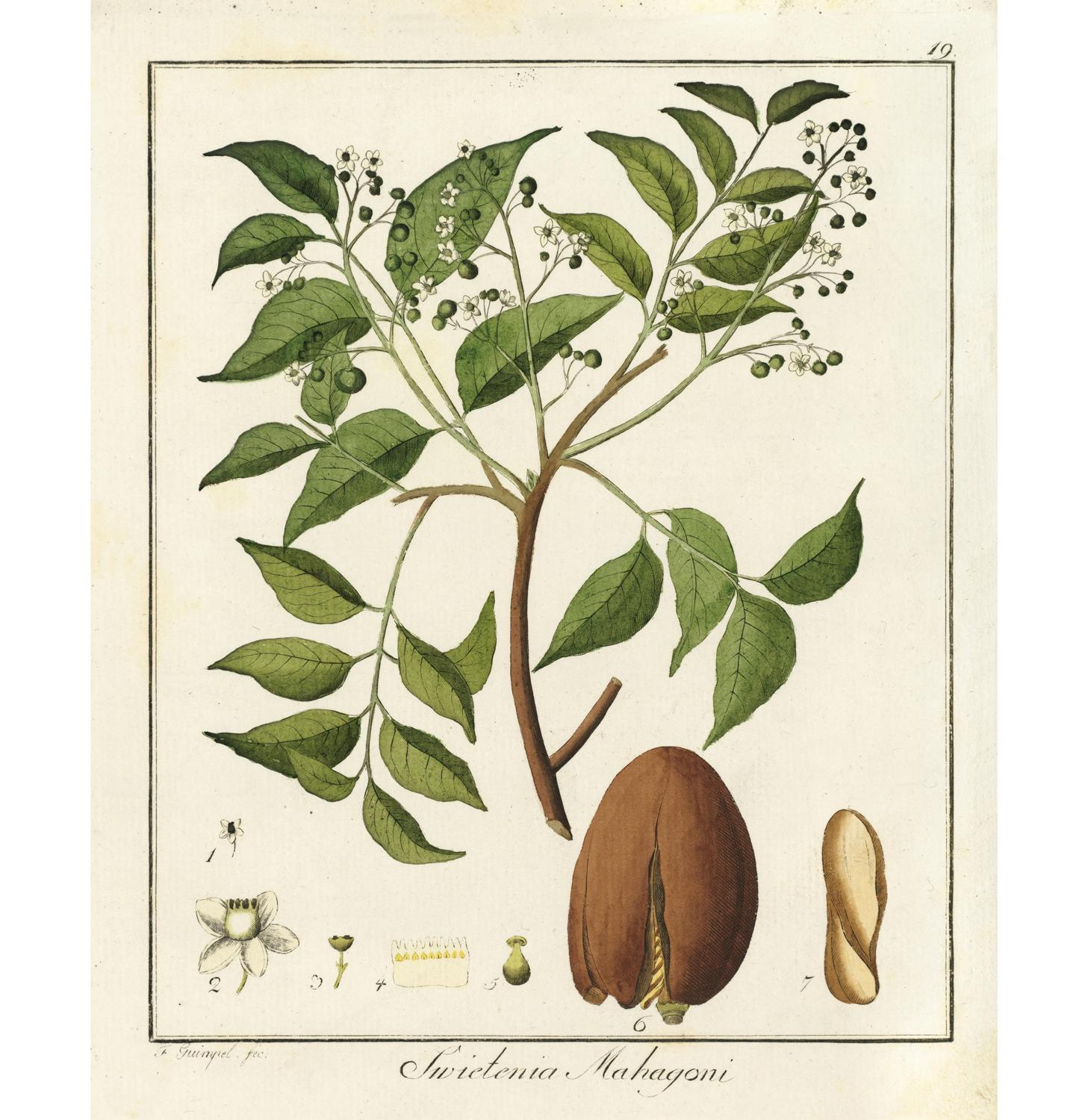

‘True’ mahogany belongs to the genus Swietenia, named by Nikolaus Jacqui, a Dutch disciple of Linnaeus, in honour of his patron, Gerard van Swieten, professor of medicine in Vienna. Linnaeus had thought it was a kind of cedar. Southern American mahoganies were widespread through the tropical regions of the continent and the Caribbean, and had been long used by people in the area. They consist of three closely related species, S. mahagoni, S. humilis and S. macrophylla. The first was found predominantly in southern Florida and the Caribbean as far north as the Bahamas; the second, with smaller leaves and preferring drier climates, spread from northern South America into Mexico; the third, the big-leafed favourite of modern plantations, was dominant in Brazil and Honduras. These three species can hybridize freely. They supplied most of the European and North American requirements for beautiful furniture, carvings and building construction. Imports peaked in the late 19th century, by which time supplies were already becoming much scarcer.

Mahogany needs sun and warmth to thrive, and is slow growing and solitary. This means that no mahogany forests exist ready to be exploited: rather, isolated trees have to be individually cut and laboriously dragged to a navigable waterway, road or (now) rail terminus. With proper spacing they can be plantation grown, but the mahogany shoot-borer is a serious pest. Successful plantations have been established in India, Bangladesh, Indonesia and Fiji. In an attempt to preserve this magnificent tree (S. macrophylla, can reach up to 70 m/230 ft and 3.5 m/12 ft in diameter), two principal things are being done.

First, mahogany is now listed by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) and its exploitation is being increasingly regulated. This happened only after massive wastage in the Amazon, where trees were simply felled and burnt when land was cleared for ranch and other food-related use. Despite the restrictions, a large percentage of mahogany trees are still illegally logged. It is estimated that in Peru, currently the world’s largest exporter, up to 80 per cent of mahogany is produced outside international regulations.

A flowering sprig of Swietenia mahagoni, with a five-lobed seed capsule and seed. The capsule persists on the tree through the winter before cracking open to release its seeds to take flight in spring. In its native Caribbean, preparations from the tree’s bark were traditionally used as a medicament.

Second, ‘mahogany’ now includes a number of other hardwood trees, some not even in the same family. African mahogany belongs to the genus Khaya or Entandrophragma; Sri Lankan mahogany is a cedar tree; while Philippine, New Zealand and Chinese mahoganies are yet other types of tree. They are all marketed as ‘mahogany’. So today mahogany furniture may or may not be made from the same kind of tree used by Chippendale, the brothers Adam, Hepplewhite or the other brilliant craftsmen and designers of Britain, Europe and the United States during the heyday of the wood. But the enduring qualities of the true mahogany are still appreciated. Apart from furniture, it is used in some of the famous Ludwig drums and for the best electric guitars, including Gibson, because it produces a warm, vibrant sound. The wood’s properties of beauty and durability still command respect, and a price to match.