Coffea arabica, with flowers and both ripening and fully ripe berries.

Plant products have long been exchanged as barter or for money. Trade networks in the ancient Mediterranean, Asia and the New World were extensive, and often involved timber, food or materials for cloth. Modern exploitation of cash crops differs mainly in its scale and the wholesale transplantation of plants outside their original settings.

Tobacco was moved around the New World before Europeans encountered the ‘sot weed’, and was used in most of the ways that it still is. Sugar cane had already been transported from the Pacific islands into Asia and Southwest Asia and Africa before Europeans took it to the Caribbean and mainland America. Tea plants were more carefully guarded in China before they, too, were smuggled out, as seeds or young plants, to India, Sri Lanka and eventually to Africa. Coffee gradually spread from its home in Ethiopia, both to the New World and Java, and other parts of Africa. Demand for tea, coffee and sugar grew in parallel, and sugar and tobacco (along with cotton) fuelled the development of slavery in the New World, as plantation growers expanded production of these labour-intensive crops.

Like coffee and tea, chocolate also contains stimulants; unlike its original New World connoisseurs, Europeans preferred it sweet. They also adapted its processing and vastly extended production beyond its Central and South American homeland to several tropical areas of Africa, from where much of it now derives.

Left A flowering, fruiting stem of a banana, with a banana tree to the left, in a detail from a vivid hand-coloured plate in John Cowell’s The Curious and Profitable Gardener (1730). A note in the Kew Library copy, from the library of Sir Hans Sloane, comments that these were ‘painted in their natural colours’.

Right ‘Bud sport of Sugar Cane’, an original artwork from a set recording various trials and experiments on Barbados at the end of the 19th century. These sweet grasses come in a wonderful range of colours and patterns.

Africa in turn donated the oil palm to Malaysia, Indonesia and Thailand, as well as to tropical Central and South America. The development of large plantations in areas the palm was introduced to has inevitably resulted in environmental damage, with loss of local habitat and rainforests, together with the issues that monoculture always brings.

The banana, now grown far beyond its home in Southeast Asia and available all year round, does not produce seeds, which means that plants are clones with no natural genetic variation, a worrying addition to the usual pitfalls of monoculture. Plants were taken to the New World to provide local food for slaves, and refrigerated shipping from the late 19th century helped expand the market.

The unusual properties of rubber’s sap were known by people in the Amazon, but its successful commercial exploitation needed the input of chemical technology (vulcanization) to stabilize the product and make it more resilient to temperature. First bicycles, and, above all, automobiles, vastly increased the market for it and led to massive rubber plantations in parts of Africa, China and the Philippines. Chemistry, too, has dramatically affected world supplies of indigo, long prized for its rich blue colour, whether from the Asian indigo tree or the European herbaceous woad. Valued for thousands of years, indigo is now mostly synthesized in the laboratory.

Camellia sinensis

I am in no way interested in immortality

But only in the taste of tea.

Lu Tung, 9th century

Tibetan teapot from Shigatzi, brought to Kew by Joseph Dalton Hooker after his forays in search of plants. Traditionally, Tibetans favoured brick tea, which is first steamed, compressed and aged. Broken up again, the tea is then churned with salt, yak butter and hot water in a bamboo vessel, and kept warm in the teapot on a brazier.

Both the tea plant, Camellia sinensis, and tea drinking originated in China. The plant is an attractive, evergreen shrub (or tree if allowed to grow), which needs elevation, warmth, good rainfall and an acid soil. Like coffee and certain other plants, tea leaves contain two especially important alkaloids: caffeine and theophylline. Both are stimulants and both are addictive, which helps explain why tea (and coffee) drinking has long been so widespread.

The origins of tea drinking in China are shrouded in myth, but tea leaves were gathered and used in infusions possibly by the mid-1st millennium BC. The plant’s leaf was probably chewed even earlier, as it still is today in the southwestern regions of China where C. sinensis is indigenous. Tea’s cultivation, preparation and use are intimately intertwined with China’s ancient and turbulent history. It was used as a currency and an official means of payment; it was frequently taxed at a high rate and subject to a state monopoly to maximize revenues. Its tastes were revered and it achieved an almost religious significance.

The two major kinds of tea, green and black, are simply the result of different picking and processing. Only the tips – the top two leaves and a bud – are picked, and this is still done by hand. Green tea is slightly younger when picked and not ‘fermented’ (oxidized) so much. More delicate, it was the preferred brew in China. Black tea is processed more fully. It is more robust and became the favourite in many nations abroad. Between these two, oolong is also popular. The ‘curing’ of tea is an elaborate process, requiring great knowledge and skill. Properly prepared and packed, tea keeps well, an important factor in its eventual worldwide popularity.

Tea drinking was so fundamental in Chinese society that ceremonies evolved around it. Such ceremonies were even more ritualized in Japan, after Buddhist monks studying in China took tea back to their native country in 805. The Japanese tea ceremony reached its highest form with Sen Rikyū in the late 16th century. It was bound by strict rules and took place in a precisely constructed room with a host and five guests. The entrances and exits, implements, dialogue and order of events were carefully orchestrated. In a sense, the tea itself was almost incidental to the wider meanings of the ceremony, but it had to be properly prepared, brewed and served to perfection. Variants of the ceremony were introduced after Sen’s execution in 1591 (for reasons that are unclear), but the ceremonial importance of tea has remained a feature of Japanese life.

Tea was central to Chinese society too; and Mongol invaders also developed a taste for the beverage, mixing it with milk and butter. Tea also gradually spread overland into Russia and other Asian countries. The first Russians recorded to have tasted it were two envoys sent in the early 17th century to negotiate with a Mongol prince. After the drink had become popular throughout the vast country, the samovar came to embody Russian domesticity, with its clever internal pipework keeping hot water and tea always on tap. Most tea reached Russia via Kyakhta, a once prosperous town on the Mongolian border – its tea market was the reason for its historical status.

Tea arrived in Europe by boat. After the opening of the ocean route to Asia via the Cape of Good Hope in the late 15th century, reports of the beverage began to trickle back to Portugal and the rest of Europe. The Dutch began importing it to Europe in the early 17th century, and the diarist Samuel Pepys recorded his first experience with the ‘China drink’ on 25 September 1660. Tea had just become available, and was sold at Thomas Garway’s famous coffee house in Exchange Alley, London, and along with coffee it quickly became fashionable. Import taxes meant that much of the tea was smuggled.

For almost two centuries, Europeans did not know where in China the plant was grown, since trade was carefully controlled and few foreigners were allowed beyond Canton, the main port. In fact, the transport of the tea from the inland sites of growing and processing involved heroic feats of organization and physical labour. Understandably, it was assumed at the time that green and black tea came from different tea plants.

Transporting tea by raft, packing and labelling tea crates, and weighing tea – a Chinese business in Chinese hands. By the 19th century, much of China’s official trade passed through the port of Canton, where foreign merchants could set up trading houses or factories but were not allowed inland. They were obliged to deal with the government-designated merchants or ‘Gong Hang’.

The benefits and dangers of tea drinking were long debated, and the 18th-century lexicographer Samuel Johnson, an inveterate consumer, had to defend his habit. Gradually, however, the beverage installed itself at the centre of British life. British demand for tea, and having to meet the Chinese preference for silver to pay for it, led to a desire to find an export to China to balance expenditure. Opium fitted the bill, and the 19th-century Opium Wars were partially fuelled by the British obsession for tea. In the mid-19th century the ‘tea clippers’ competed to be the quickest from Chinese ports to English ones, and the races were deemed newsworthy, although properly prepared and packed tea stores well, so it was not really about the quality of the final drink.

Left ‘Bergamotto Foetifero da Padoua’ by Johann Christoph Volkamer in Nürnbergische Hesperides, (1714). The essential oil from the rind of the Bergamot orange (Citrus bergamia) gives the unique flavour to the tea blend known as Earl Grey. This orange is thought to be a hybrid between the sweeter C. limetta and the bitter orange, C. aurantium.

Right An idyllic scene of a tea plantation from Samuel Ball’s An Account of the Cultivation and Manufacture of Tea in China (1848). Ball served as inspector of teas for the East India Company in Canton and wrote his book after returning to Britain, to assist those trying to cultivate tea in British India and other parts of the empire.

Consumer demand also encouraged the search for other areas for tea growing, and after early difficulties cultivation of the plant enjoyed increasing success in British India, first in Assam and then in Darjeeling and other hillside areas. This encouraged tea plantations elsewhere, including Kenya and other parts of East Africa. In Ceylon (Sri Lanka), tea proved a blessing after the coffee plantations were wiped out by a fungal disease.

Tea continues to be one of the most popular beverages in the world, especially in Britain, Australia and its areas of early production, China and India. In the modern world, ‘brands’ have come to dominate. These often still bear the names of previous entrepreneurs, such as Lipton and Twining; Earl Grey tea, with added bergamot flavourings, also bears a famous name. The tea bag, introduced around 1908, and derided by connoisseurs, finally democratized this once elite drink.

A flowering sprig of the tea plant, Camellia sinensis, in the same genus as garden camellias. The tips or terminal flush, ‘two leaves and a bud’, are picked twice a year in early spring and late spring/early summer. The ‘bud’ is not an unopened flower but an immature unopened leaf.

Coffea spp.

Coffee makes us severe, and grave, and philosophical.

Jonathan Swift, 1722

A Turkish gentleman sips his coffee, above, with the plant, beans and a coffee roaster depicted below, in this delightful engraving from Philippe Sylvestre Dufour’s Traitez nouveaux & curieux du café, du thé et du chocolate (1688).

Caffeine is the world’s most commonly used psychoactive drug. In fact tea leaves contain higher caffeine concentrations than coffee beans, but a cup of coffee delivers some ten times more caffeine than its tea equivalent. The genus Coffea contains two especially important species, arabica and robusta (canephora), which account for virtually all the world’s coffee production. The former produces a richer, subtler aroma and taste, while the latter – cheaper, harsher and more bitter – is the favourite for instant coffee. Most commercial coffees blend the two.

Coffee belongs to the tropical family Rubiaceae and the bush grows best at altitude in warm climates with plenty of rain. It is native to present-day Ethiopia, where it is still cultivated but also grows wild. According to legend, a young goatherd noticed that his goats that had eaten the coffee berries (the seeds, or beans) were frisky and unusually lively. He subsequently got hooked on them himself. Legend aside, sucking coffee beans was almost certainly the earliest method of use. Eventually, the leaves and berries were boiled to yield a drink containing the stimulant caffeine.

Medieval Arabic texts first mention the beverage, and for several centuries its use was confined to northern Africa and southwestern Asia. Coffee became a favourite with Muslim clerics as it enabled them to continue their meditations through the night. The beans were later transported east, where they were cultivated in India, Sri Lanka and other Asian countries by the early 17th century, about the time that Europeans discovered what a cup of coffee could do. There was a coffee house in Constantinople (Istanbul) by about 1475, and Europeans there enthused about the new beverage.

The Coffee House became a central part of European culture from the mid-17th century in cities such as London, Paris, Amsterdam, Vienna and Berlin. In these establishments the availability of newspapers and the discussions on a range of current affairs were as important as the beverage, but coffee, along with tea – both drinks appeared roughly simultaneously (as did chocolate) – were the reason the place was there. In Vienna, coffee houses continued to serve important cultural and political functions into the modern period. The Viennese had discovered the bean after the siege of the city was lifted in 1683 and the retreating Ottoman army left behind their supplies, including the precious beans.

Coffea arabica from a multi-volume work by Dr Friedrich Gottlob Hayne (1825). Despite its easy availability as a beverage, coffee was still regarded as a medicinal substance. Relatively pure caffeine was isolated in 1819 by Friedlieb Ferdinand Runge.

Coffee has often vied with tea as a nation’s favoured caffeinated drink, and both have served the same sociable and stimulating roles. The French flirted with tea, but coffee won out in the 18th century. Paris had 2,000 coffee houses on the eve of the French Revolution. In Britain, tea supplanted coffee in the 19th century: it was cheaper and easier to transport and store. In the United States, where there were coffee houses as early as 1670, coffee was the victor, and the modern history of coffee is closely tied to the economic and political fortunes of that country, which in the 19th century was by far the leading coffee consumer in the world. By this time coffee cultivation had spread to many parts of the globe where conditions and labour supply were favourable.

Generally these regions were part of European colonial possessions, and included Brazil, Colombia and Costa Rica in the Americas, Kenya in Africa, and (briefly) Ceylon (Sri Lanka) and (more lastingly) Java in Asia. Brazil has long been a leading coffee producer. The Brazilian harvest has periodically been affected by adverse weather or occasional drought, but mostly by sharp cold, which the plants do not tolerate. Coffee was so important for Brazil’s balance of payments that successive governments aided the growers’ associations, helping stockpile gluts to keep the international price up, and sometimes tiding over growers in times of poor yields. International financiers, mostly American, also invested in coffee planters and stores.

Cultivation of coffee is labour intensive, since the beans must be gathered by hand – they ripen sequentially so mechanical means don’t work. The raw coffee beans are generally exported for roasting in the country of consumption. Roasting is easy in theory, but hard to get right. The longer the pale beans are roasted, the darker the bean will become. The process releases the aromatic and volatile compounds that give coffee its aroma (one of the best in the world) and taste. The aroma is there, briefly, in a recently opened jar of instant coffee, although the taste is different. A Belgian named George Washington developed an instant brew in 1906, in Guatemala. (He was not the first.) Washington subsequently emigrated to the United States. The First World War proved a godsend for the new product, which could be easily made wherever almost boiling water could be produced. American troops called Washington the ‘soldier’s friend’. Instant coffee is made now mostly by freeze-drying brewed coffee, which produces the powder or granules in the commercial jar.

The flowers (right) and the subsequent beans (left) of Coffea arabica. This watercolour is by Manu Lal (fl. c. 1798–1811), painted in the Company School style developed by Indian artists for the British to meet their need for naturalistic representation of plants, animals and people. Many artists, including Lal, worked for the East India companies that ran the country.

Plantations grew coffee in bulk and also processed it. Here, coffee is being dried by steam in Brazil in an illustration from Francis Thurber’s Coffee: from Plantation to Cup (1881), published by the American Grocer Publishing Association. Thurber travelled widely and reported on many aspects of coffee production and consumption, including the poor working conditions on many plantations.

For many people today, ‘coffee’ is instant coffee, but the rise of the new wave of ‘coffee houses’, which cater for a computer generation as the old ones did for those in search of a newspaper and warm fire, has produced its own modern clientele, who care about the source, taste and style of their caffeine drink.

Saccharum officinarum

Around thee have I girt a zone of sugar cane to banish hate.

That thou mayst be in love with me, my darling never to depart.

Hymns of the Atharva Veda

A bottle of crude sugar brought back from David Livingstone’s second Zambezi expedition by Sir John Kirk, who acted as the official doctor and naturalist in 1858–63. A keen botanist, highly regarded by the directors of Kew, he became the Vice-consul of Zanzibar and successfully brought an end to slavery on the island with the co-operation of the sultan.

A sweet tooth is nothing new. Long before the ready availability of cheap, highly refined sugar, human beings sought out naturally occurring sweet tastes; sugars are ubiquitous in plants and animals. An especially rich source of sucrose, the ‘sugar’ of sugar, is Saccharum officinarum, or sugar cane. A member of the grass family, sugar cane was probably first cultivated in New Guinea, though the genus is another that hybridizes easily and the wild original species is unknown. Unlike many canes, such as bamboo, which are hollow, the centres of the sugar cane stalks are fibrous and the juice contains about 17 per cent sucrose. This happy fact was discovered long ago: sugar cane was chewed in the Pacific islands and grown in India – Alexander the Great sent sugar cane home from there – and China well before the Christian era. Strabo, writing in the early 1st century AD, repeats earlier accounts of ‘reeds that yield honey’ without bees.

The process of extracting and boiling down the sap to make solid sugar was discovered in antiquity; the Indians called this raw brown solid ‘jaggery’. By the 7th century AD the Persians had discovered that adding lime could render the product white. The Arabs established sugar plantations throughout Southwest Asia, North Africa and on several islands in the Mediterranean, usually with irrigation. From there, sugar gradually made its way into Europe, although it was very expensive; honey, in which fructose is the primary sugar, was still the main sweetener used.

Sugar canes are tropical plants that grow well on rich soil with plenty of rain and sunshine; some can reach up to 6 m (almost 20 ft) tall. As the European taste for the luxury item increased, the Iberian countries established plantations on Madeira and the Canary Islands. Columbus took cane with him on his second voyage to the New World, where the Caribbean isles proved suitable for its cultivation. Sugar was expensive because it was laborious to produce. The tough canes had to be cut near the roots, the leaves stripped off and then quickly crushed and the juice boiled down, filtered and boiled down again. Planting and harvesting were backbreaking work. The cane grows best if a portion containing a node is planted, either in a trench or a single hole. The fields must be weeded and watered if rain is insufficient, and the processing, no easy task, used a lot of fuel. Madeira was largely deforested for cane growing and production.

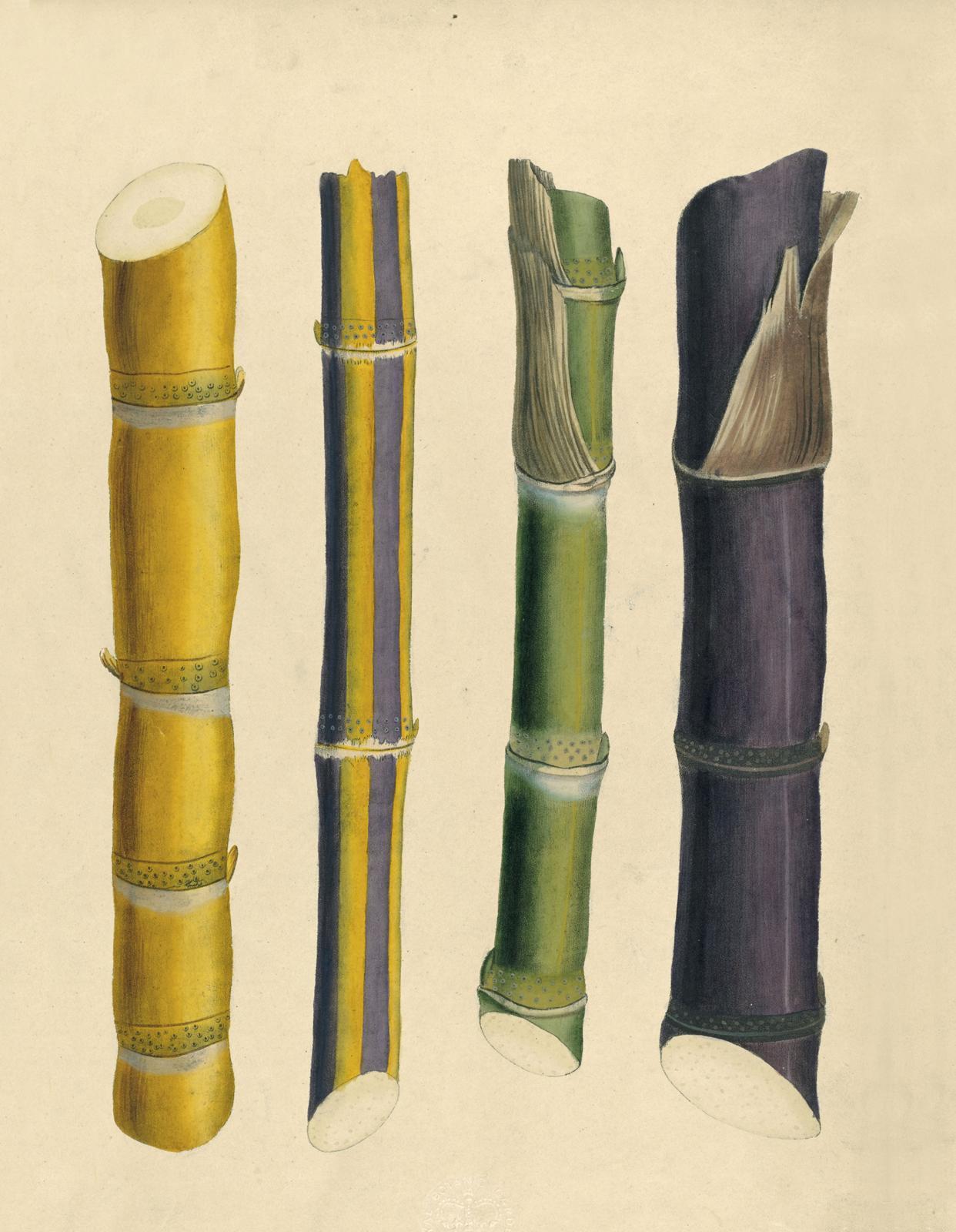

Four different coloured varieties of sugar cane as featured in François Richard de Tussac’s flora of indigenous and imported exotics, Flore des Antilles (1808).

With the coming of tea, coffee and chocolate to Europe in the 17th century the demand for sugar increased markedly. Manpower was needed to work the plantations in Barbados, Jamaica, Brazil and other New World locations. Indentured labour schemes proved inadequate, and African slavery was the terrible solution. Between 1662 and 1807, when Britain’s trade was abolished, some 3 million Africans were transported in her unsanitary and overcrowded ships. The Portuguese, Spanish, Dutch and Americans also had active slave transportation systems for sugar plantations in Brazil and other colonial possessions, as well as Louisiana in the United States. The journey from Africa to the Americas, known as the ‘Middle Passage’, was part of a triangular route – ships left Liverpool, London or Bristol laden with merchandise to be exchanged for slaves on the west coast of Africa; after transporting them across the Atlantic to the plantations, the ships would return with the prized cargoes. African slavers captured their unfortunate victims, mostly men but also women and children, from the interior of the continent. Survival rates were variable on the long crossing, but conditions were routinely atrocious, with little and bad food, and crowded, inhuman conditions.

The nature of sugar cane cultivation made plantation settings desirable. They varied greatly in size, and were often referred to not by their area but by the number of slaves. Slavery helped define the histories of the New World areas where it was practised, and beyond. After the abolition of slavery in the 19th century, by the French, British, Americans, Dutch, Spanish and Portuguese, the importation of sugar workers from Asia, the Polynesian islands and the Mediterranean countries left an indelible mix on the ethnic compositions of the sugar-producing lands.

It has been estimated that it took one African life to produce a tonne of sugar, but such was the scale of the operation that the price of sugar in Europe and North America came down dramatically from the late 17th century, and it became a commodity within reach of most people. The final refining process was generally done outside the areas of supply, since fuel and power were more easily available there. The British even re-exported some sugar back to the producing colonies.

The basic cultivation requirements for growing cane remain the same, but the production process has changed over the past century. Cutting the cane is now done by machine, making level fields preferable, and pressing and extracting the juice are also mostly mechanized. Little is wasted: the residue of the first boiling, molasses, is used in cooking or distilled to make rum. Sugar distillation yields alcohols and biofuels, and other products include chemicals, fertilizers and animal feeds. Today, the major producers of sugar cane are Brazil and India.

A rival of the cane and another source of table sugar is sugar beet (Beta vulgaris). A German chemist, Andreas Sigismund Margraf, discovered in the middle of the 18th century that significant concentrations of sucrose could be extracted from this root crop. Sugar beet can tolerate a wide range of soils and climates, and during the British blockades of the Napoleonic Wars, Napoleon encouraged its cultivation and processing in France, to keep his soldiers sweet. The end table product, sucrose, is the same as from cane, and today about 20 per cent of sugar worldwide is derived from the beet. Despite the global epidemic of obesity, diabetes and other sugar-related ‘diseases of civilization’, sugar remains very popular. Its sweetness has brought pleasure but also pain.

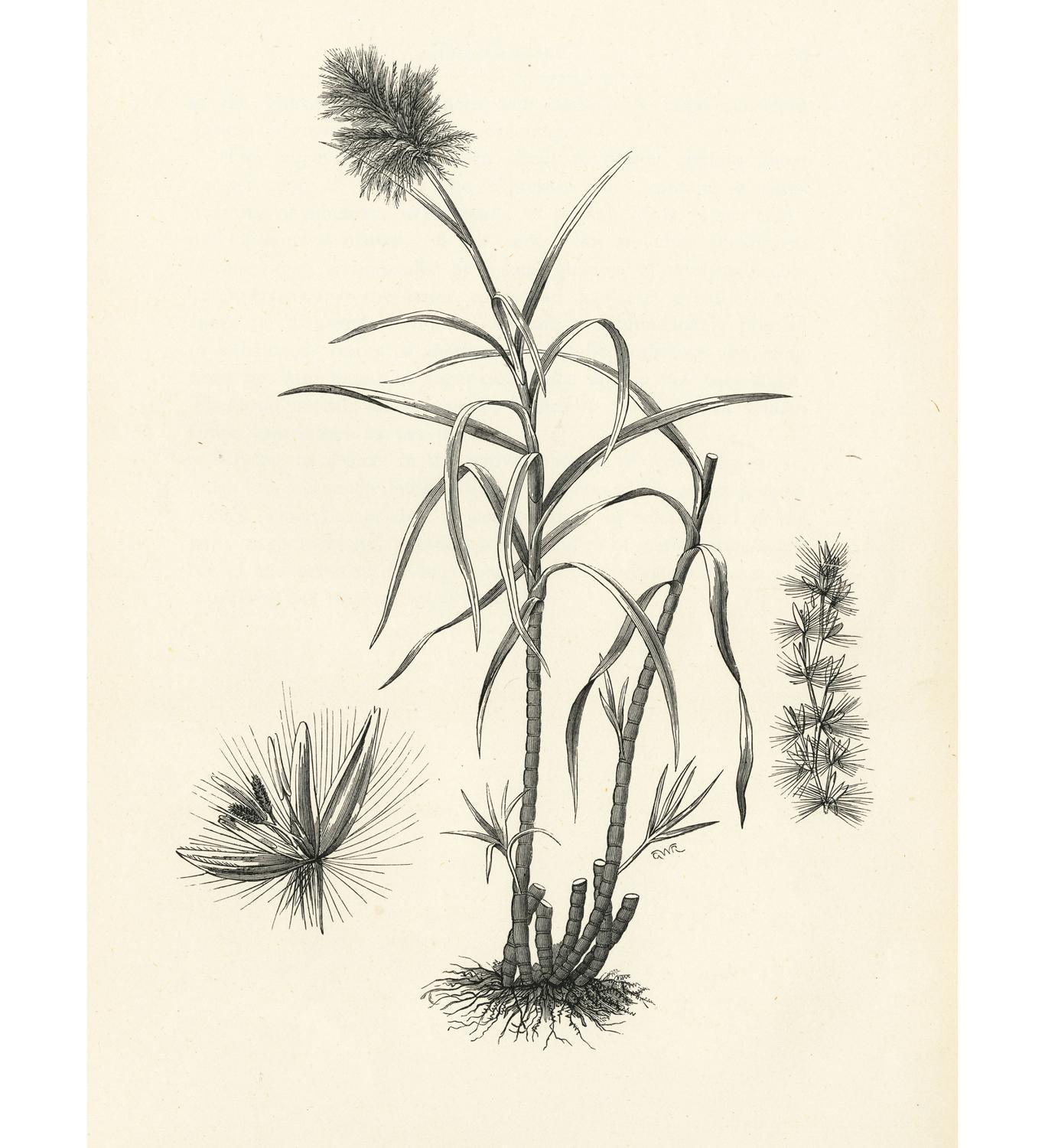

In Food-grains of India (1886) the agricultural chemist Arthur H. Church described the sugar cane as ready to cut when about to produce the ‘large feathery plume of flowers’, and included details of these flowers in the plate which illustrated Saccharum officinarum. Once the cane has flowered the sugar-containing stalk stops growing.

Theobroma cacao

Up, and Mr. Creede brought a pot of chocloatt ready made for our morning draught.

Samuel Pepys, Diary, 6 January 1663

For many of the ancient cultures of Mesoamerica and South America, the chocolate tree held a special place. It featured in the creation myths of the Maya, and the Aztecs used the beans (seeds) as a currency. It was so prized by the Aztecs that they imported it over long distances. The even older Olmec civilization also valued the beans of the tree, and ‘cacao’ probably derives ultimately from their language, now unfortunately lost. The Maya referred to the plant, its seeds and the product as cacao, and cognates exist in other Mesoamerican languages. Linnaeus, who was fond of chocolate, bestowed its current botanical name: Theobroma, meaning ‘food of the gods’, and the native word cacao.

T. cacao is a fastidious tree that doesn’t naturally grow beyond a range of about 20 degrees north or south of the Equator. It needs shade, high temperatures and humidity. On modern plantations, the over-storey is generally provided by either rubber or banana plants. The pods grow directly from the tree’s trunk and stems (a phenomenon called ‘cauliflory’), and the flowers are fertilized exclusively by midges (they do have some use). Only a tiny fraction of the flowers go on to produce a pod, and a good tree will produce about 30 pods each year. Within the pod, the pulp surrounding the seeds is sweet but the raw kernels are quite bitter. They must be fermented, dried, roasted and winnowed (the removal of the thin shell) before the cacao ‘liquor’ is produced. Debate continues about where the tree originated – probably Amazonia – but it was domesticated in Mesoamerica. Another species of Theobroma (bicolor) is also grown from southern Mexico to Brazil, where its product, called pataxte, is drunk or mixed with the seeds of the more expensive cacao.

Native Americans ate the juicy pulp or drank the ground beans in a beverage, mixed with a variety of flavourings including chillies and vanilla. As befitted a substance so venerated, it was used on ceremonial occasions. The Maya had a cacao god, with a regular festival. Elaborate utensils for drinking chocolate survive, and the vessels, and probably the beans themselves, were left in the tombs of important individuals. One cache, thought to be actual beans that had miraculously survived the heat and humidity of Mesoamerica, turned out to be models beautifully made from clay in the shape of the bean. Always expensive, the beans were reserved for elites and the rich. Chocolate was thought to be intoxicating and too dangerous for women and children. The beans do contain a complex set of alkaloids, including caffeine and theobromine, that today would be described as stimulants rather than intoxicants.

Flowers, leaves and fruit of Theobroma cacao, with details of the flowers and inside of the fruit and seeds, from Fleurs, Fruits et Feuillages choisis … de l’île de Java (1863) by Berthe Hoola van Nooten. She turned to botanic art as a means of supporting herself after she was widowed, although the queen of the Netherlands helped with publication. Nooten’s art seemed to capture the lush exoticism of the tropics and was turned into sumptuous chromolithographs by Pieter De Pannemaeker.

Varieties of raw cacao kernels from chocolate’s homeland and places around the world where it was transplanted: Ceylon (Sri Lanka), Guayaquil, Caracas, Portuguese Africa, Trinidad, Samoa. These boxes were once part of an exhibit at the Museum of Materia Medica at University College Liverpool (later the University) – a reminder of chocolate’s long association with medical use and the continued claims for the health benefits of dark chocolate’s flavanols.

Columbus encountered the beans in a captured canoe during his third voyage to the New World, but it was not until the Spanish landed in Mexico that Europeans sampled the exotic drink. They didn’t take to it immediately, but soon learnt to flavour it with vanilla and other spices. Sugar was eventually added to make it the sweet drink it now is. The beans reached Spain by 1544, and were a commodity rather than simply a novelty by 1585, although as in their homeland they remained so expensive that only royals and elites could indulge in them. Chocolate gradually spread to other parts of Europe, including Italy. The French discovered it in the early 17th century, and by 1657 there was a chocolate seller in London, with the drink soon available at the tea and coffee houses. Europeans generally preferred to take it sweetened and hot, although the Spanish continued to add chillies.

Once the commodity was more widely available, cooks began to incorporate it too, although it was mostly used either medicinally or socially. Increasing European demand led to further planting of the tree in several Caribbean islands, including Trinidad and Jamaica. When the British captured Jamaica from the Spanish in 1655, it became a major supplier for the British market. The plantations had grown the original Mesoamerican variety, Criollo, which produces fine chocolate but is very disease prone. After a blight virtually wiped out the Trinidad plantations, a more robust variety, Forastero, replaced it. Forastero had been discovered growing wild in Brazil. It now accounts for almost 80 per cent of world production, although hybrids are being developed that combine the robustness of Forastero with the finer flavour of Criollo. The international market has resulted in the spread of Theobroma cultivation to many areas within the climatic constraints of the plant; West Africa is now the world’s leading producer.

The processing of the pods yields a number of different products, each of which has uses. The sun fermentation of seed and pulp is essential to develop the flavours and results in a full-fat liquor, which was what was consumed until the early 19th century. Then, in 1828, a Dutchman, Coenraad van Houten, with his father, patented a process that reduced the paste by about two-thirds, yielding a product called cocoa. A portion of the cocoa butter that had been extracted could then be added back to the residue, producing the solid (which melts in the mouth) that we call chocolate. Within a couple of decades, chocolate bars were on the market.

Many of the familiar names in chocolate confectionery date from the 19th century: Cadbury in Britain, Lindt in Switzerland, Hershey in the USA. As with any mass-produced product, the finished product varies and is generally determined by the percentage of cocoa solids. ‘Milk chocolate’ was invented when a Swiss confectioner, working with Henri Nestlé, added dried milk in 1876. There is now a chocolate for every taste.

Nicotiana spp.

A custome loathsome to the eye, hatefull to the nose, harmfull to the braine, dangerous to the Lungs.

King James I of England, 1604

An Indian nabob rides on his palanquin, smoking from a hookah or hubble-bubble pipe carried by one of his servants. In India tobacco might be mixed with sugar and rosewater. In Egypt and elsewhere it was blended with fruit, mint and molasses to produce shisha, hence the similar shisha pipe. In both, the smoke is bubbled through water before being inhaled.

Tobacco has been almost universally demonized, but it is still much in demand. This is not just a modern phenomenon: ever since its introduction to Europe in the early 16th century, there have been critics as well as advocates.

Although species of Nicotiana existed in Australia, the current tobacco plant originated in the New World, where it is probable that it was deliberately cultivated several thousand years ago. Of two native species, N. rustica and N. tabacum, the latter provides most of present-day production. Tobacco’s original home was likely the eastern parts of South America, but varieties were widespread through the western hemisphere in pre-Columbian times, as was use of the plant. A member of the Solanaceae family (which includes the tomato and potato), tobacco is an annual that grows to a height of between about 20 cm and 3 m (8 in. to 10 ft), depending on the variety and growing conditions. It is grown commercially for its leaves, which are harvested and then dried for use.

Tobacco leaves contain numerous alkaloids, of which nicotine, isolated by two Germans, Wilhelm Heinrich Posselt and Karl Ludwig Reinmann, in 1828, is by far the most potent. Tobacco is both psychologically and physiologically addicting. In high concentrations it can also be hallucinogenic, a fact appreciated by priests and shamans of pre-Columbian America. Both the Maya and the Aztecs prized the leaf. American peoples used the ‘sot weed’, an early European appellation for the substance, in many of the ways that it still is – they made cigars, smoked it in pipes, took snuff and used it in teas and enemas. Tobacco was also important ceremonially, with North American tribes creating elaborate pipes, some for war and some for peace.

Both the plant, Nicotiana tabacum, and (later) the alkaloid were named for Jean Nicot, who served as French ambassador in Lisbon, Portugal, in the 16th century. Here he learnt about tobacco, particularly its medicinal use, and sent seeds back to the French court where it became popular with Queen Catherine. Instead of smoking the leaves, he advised her to crush them and inhale, like taking snuff.

Columbus was given tobacco on his first voyage. Although his men initially discarded the leaves, on the second landing, in modern-day Cuba, some of the sailors tried smoking, and tobacco was among the New World products taken back to Spain. At first tobacco was also used medicinally, but the smoking habit spread fairly quickly to the Mediterranean countries, and to Britain, where tobacco was introduced around 1564. Queen Elizabeth I tried it, but her successor, King James I, was violently opposed to the weed. He did, however, appreciate the boost to his purse that the duties (which he increased dramatically) provided, though they also encouraged smuggling.

In Europe most tobacco was initially smoked in pipes, with some also rolled into cigars. In the 18th century, taking snuff (ground tobacco sniffed up the nose) grew in popularity, a custom accompanied by the manufacture of ornate snuffboxes. Tobacco was officially a male preserve, although ladies began to take snuff and lower-class female tobacco smoking also increased. The habit even influenced domestic architecture and the rituals of dinner, with the ladies withdrawing after meals to leave the men to their pipes, cigars and port. Large houses had their smoking rooms, sometimes with a billiards table.

Tobacco was the first major cash crop for the original English settlements in Virginia and played a large role in their financial viability. As early as 1613, the leaf was being exported to England, and by the mid-18th century it was the major revenue earner for the colonies on the southern eastern seaboard. At first tobacco growing was small-scale, but as tenant farmers strove to satisfy demand, operations expanded by using African slaves. Tobacco plantations were also established on several of the Caribbean islands.

Tobacco growing spread to the American Midwest, and in the 1860s an Ohio planter noticed a new variety that was to change the face of the industry. Cigarettes, with the tobacco wrapped in paper, had been smoked in some form even by pre-Columbian Americans, and British soldiers in the Crimean War (1853–56) had learnt the custom from Turkish use. The new tobacco, called burley, has little chlorophyll and its yellow leaves are much milder. Burley became the favourite for machine-rolled cigarettes since it was much easier to inhale and smokers absorbed more nicotine, with addictive results.

Two occurrences in particular facilitated the meteoric rise of cigarette smoking around the turn of the 20th century. The first was the increased power of advertising following the arrival of mass-print newspapers and magazines in the mid-19th century. As large multinational tobacco companies sought to capture brand loyalty, the advertising was ubiquitous and clever, targeting different groups, such as young people, doctors and women. The last group massively expanded the market, as smoking became associated with the ‘New Woman’, who was far more independent and had money to spend. The second strand was the advent of the First World War, which made cheap, often free, cigarettes available to millions of young people on all sides of the conflict, and behind the lines as well. Many went on to smoke regularly after the war, and the pattern was repeated in the Second World War.

In the first half of the 20th century, smoking was widespread, glamorized and affordable for almost everyone, even though taxed by governments, who welcomed the revenues. At the same time, doctors began to notice an increase in lung cancer, a rare disease before the beginning of the century. Almost simultaneously, two pairs of researchers in the early 1950s, one in the USA and one in Britain, published careful studies that implicated cigarette smoking in the modern epidemic. The American pair, Ernst Wynder and Evarts A. Graham, correlated smoking statistics with autopsies on patients dying from the disease. The British pair, Austin Bradford Hill and Richard Doll, who thought at first they might be looking at a consequence of the material used in paving roads, did more careful life histories of patients in hospitals with lung cancer. They factored out many possible causes and concluded that cigarette smoking was the culprit.

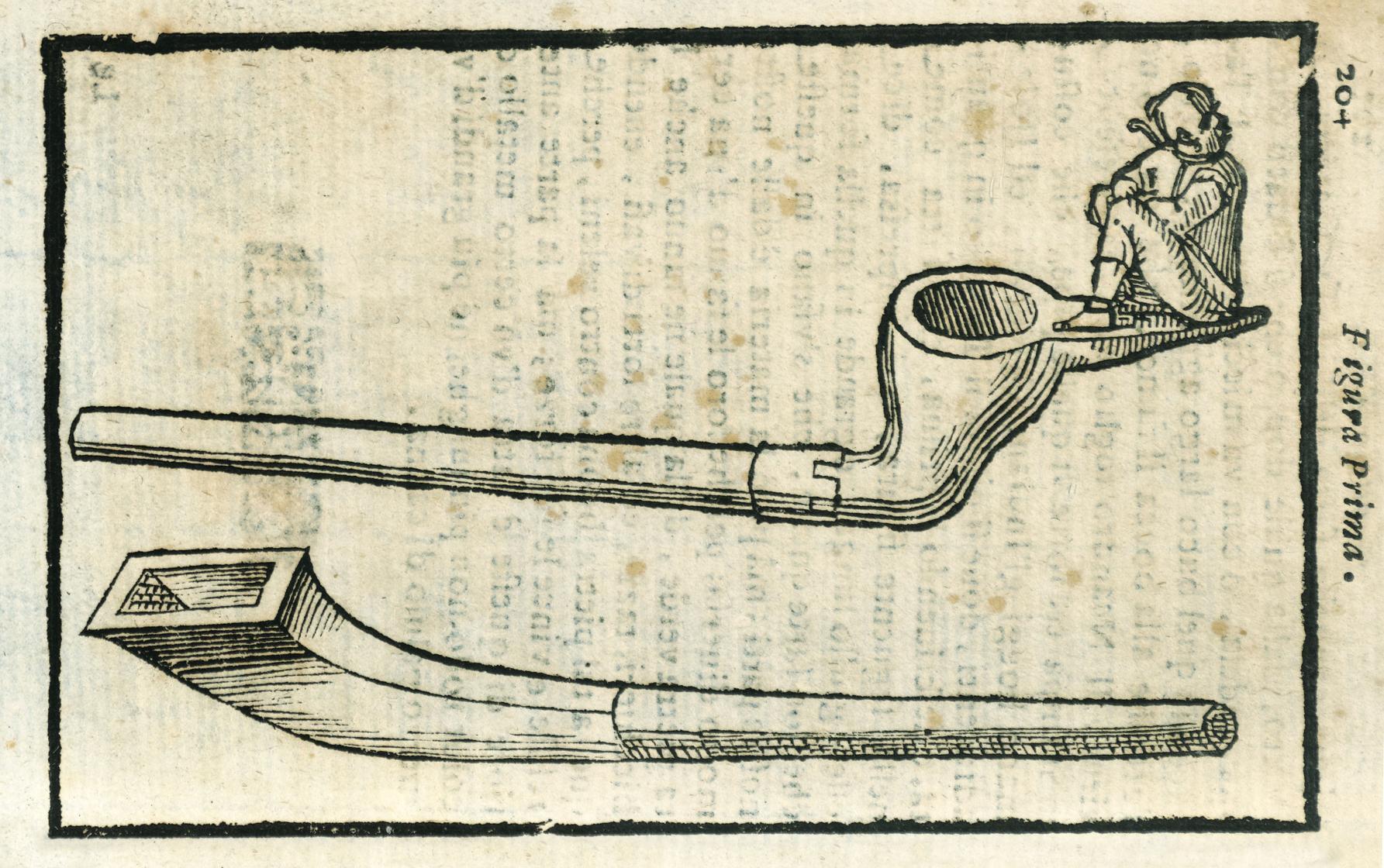

Pipe designs from Il Tabacco Opera (1669). The use of tobacco and its products quickly gave rise to a whole range of paraphernalia of containers and equipment, some becoming beautiful objects in their own right.

In retrospect, the evidence was conclusive, but it took more than a decade for it to be widely accepted, and tobacco manufacturers have been remarkably devious. First denial, then ‘safer’ options and then the right of choice have been very effective, and, even in countries where tobacco advertising has been banned, smoking rates have come down only gradually. In developing countries they are still very high, and the sot weed seems destined to be around for a while yet.

Indigofera tinctoria, Isatis tinctoria

We are not furnished but two drugs that give a permanent blue, and they are, indigo and woad.

Elijah Bemiss, 1815

Indigofera tinctoria was grown as a plantation crop in the 18th century in South Carolina, Florida, the Caribbean and in South America, where John G. Stedman witnessed its production and recorded it in his Narrative of a five years’ expedition against the revolted Negroes of Surinam (1796). He was appalled by the brutality of the slave owners.

Blue is a rare colour in the plant kingdom and even rarer in the foods we eat, but it has always been prized. It is the colour of mourning in some countries, the robes of the Tuareg in North Africa and warriors in ancient Britain. Most of this blue colouring was laboriously extracted from plants, two of which were especially significant: Indigofera tinctoria (‘indigo’) and Isatis tinctoria (woad). The word indigo refers to the dye extracted from the leaves of these and a number of other plants and derives from ‘India’, where much of the precious dye originated.

Producing indigo is a challenging and complicated process, but one that was discovered independently many times, in both the pre-Columbian New World and in the Old. The leaves must be mixed with lime or stale urine and allowed to ferment in vats. After the liquid is evaporated and further manipulated, the resulting brilliant blue powder could be easily caked and transported. It had many uses, in dyes, paints and cosmetics, and provided a base to mix with other colours. Not surprisingly, so valuable a substance was also used medicinally against many disorders, including cholera and bleeding maladies and as an aid to fertility.

Indigofera tinctoria is a tropical shrub-like plant, especially common in India, but also found throughout Southeast Asia. It was cultivated and exploited in its native setting from the end of the 1st millennium BC. Indian textiles were valued from an early period and indigo was traded via the Silk Roads and other routes. Both the ancient Greeks and Romans prized it, but they also had to rely on woad, which is a herbaceous biennial (of the brassica family) that grows in temperate climates. It yielded the same valuable dye and was closer to hand, but extraction was more difficult, since concentrations of indigotine (the chemical name for the blue pigment) are much lower. There is still debate about how ancient Egypt got its blue dyes – it could have been from woad, but Indigofera was traded in the area very early, and the Muslims continued the fascination with the colour.

European shipping routes to Asia made proper indigo more readily available, and after the British established hegemony in India they exploited both its importation into Europe and its use in their own expanding garment industries. European woad production saw a revival when Napoleon placed an embargo on British imports and encouraged French woad production for army uniforms. French, German and some British woad growing continued throughout the 19th century. Towards the century’s close, two events had a great effect on modern indigo.

Woad provided the blue increasingly sought after in Europe from the 12th century. It was widely associated with the Virgin Mary and became the chosen colour of French court. The town of Erfurt in Germany built its university on the proceeds of growing and processing woad.

The patenting of metal studding on blue jeans by Jacob Davis and Levi Strauss & Co. in 1873 gave them the necessary durability required by ranchers, farmers and cowboys. The universal appeal of jeans has ensured a continuous demand for indigo, whose characteristic uneven fading has become a fashion statement. This need has been met by the efficient synthesis of indigo, by Adolf von Baeyer, in 1897. Most natural indigo production is now small-scale, with some in India and Africa, and some by artisans in the West who still value the true blue that nature yields.

Hevea brasiliensis

… the pith of a wood that was very light.

Andrea Navigero, 1525

A number of plants produce rubber, but only the Brazilian ‘rubber plant’ is employed commercially today. It is one of many gifts of the New World to the Old, and it was exploited and revered long before the Europeans came. The Amazonians knew of the striking waterproofing properties of the latex sap that can be tapped from the tree, and rubber use was widespread in pre-Columbian Mesoamerica and South America. Containers, shoes and musical instruments were made from the hardened substance, which could be moulded as it dried, and it also had medicinal, ritual and ceremonial applications.

In the early 16th century Aztec teams demonstrated a game using a rubber ball (made from another rubber-producing plant) to the court in Spain. Indeed, Europeans seemed most fascinated by the ball game, the object of which was to put the rubber ball through a hoop without using the hands or allowing it ever to touch the ground. Only in the 18th century did naturalists take a serious interest in the tree and its product. A French engineer and amateur botanist, François Fresneau, described both the tree and the tapping for the sap in 1747, and others in South America brought home accounts of the unusual properties of rubber.

Early European attempts to exploit the substance were not successful. Various entrepreneurs in the early 19th century imported rubber to make boots and raincoats and waterproof cloth. (It was also, more successfully, noted that the material could remove pencil marks: the ‘rubber’, or eraser, had arrived.) All these enterprises failed, because in very hot weather the rubber melted, and in very cold it hardened and cracked.

Sprig of Hevea brasiliensis, with flowers (lacking petals and described as pungent) and the three-seeded nut. When ripe, the fruit explodes and the seeds can be thrown up 15 m (50 ft) from the parent tree. In plantations trees grow 25 m (82 ft) high because of the effects of tapping and have a useful lifetime of perhaps 35 years. Rubberwood is now marketed as an eco-timber rather than burned as waste.

The breakthrough came in 1839, when an eccentric American, Charles Goodyear, discovered after a great deal of empirical experimentation that adding sulphur to the melting rubber stabilized it; extreme temperatures no longer had their undesirable consequences. Goodyear spent much of his life moving his family from place to place, seeking backers and spending some time in debtors’ prisons. Although his name was posthumously perpetuated in a major international tyre company, he didn’t reap the rewards of his successful discovery. At about the same time an English chemist, Thomas Hancock, studied the process in more detail, with better chemical knowledge, and obtained an English patent for vulcanized rubber (he called it ‘ebonite’, but Goodyear’s ‘vulcanization’ has lasted).

A selection of items made from hard, vulcanized rubber. Most of these would now be made of plastic. Quite what the rubber pipe would have smelled like during use is intriguing.

Goodyear never stopped preaching the multiple uses of rubber. At the Great Exhibition in London (1851) and the Exposition Universelle in Paris (1855), Goodyear was there with displays of furniture, inkstands, vases, combs, brushes and many other ordinary items, all made of rubber. Although his efforts failed to direct the flow of funds into instead of out of his coffers, the public displays did alert the world to the possibilities of this adaptable plant material.

Increasing popularity was good for Brazilian growers and traders of rubber, if not for the collectors of the raw material – the task entailed long hours and tedious, exhausting labour. Demand for rubber brought about an accelerating clearing of the Amazonian rainforests for rubber plantations. It also stimulated the search for other areas of the world where H. brasiliensis could thrive. And it had to be that particular rubber tree: the Brazilian Joao Martins da Silva Coutinho demonstrated its undoubted superiority.

Joseph Dalton Hooker, director of the Royal Botanical Gardens at Kew, was instrumental in spreading the cultivation of the rubber plant. His agents in Brazil produced seeds that arrived at Kew in 1876. Although only a tiny fraction germinated, seedlings were later dispatched to Singapore. They all subsequently died. Plants in Ceylon (Sri Lanka) also struggled in the early years, although successful plantations were established eventually. The appointment of Henry N. Ridley in 1888 as superintendent of the Singapore Botanical Gardens proved to be the turning point. Ridley was a tireless enthusiast for the product: he experimented on the optimum growing conditions, on how, where and how often the plants could be tapped, and how seeds and seedlings were best transported. More efficient methods of collecting rubber were also devised, especially the use of acid to coagulate the latex. By the end of the century, Southeast Asia, including Malaysia (now Malaya), was a major source of rubber. The Chinese are a notable presence in the area mainly because of the indenture system used to meet demand. Everywhere, the creation of plantations required land clearance and a large workforce.

Use of rubber products grew continuously during the latter part of the 19th century, but the tyre, for bicycles and then automobiles, created a vast new market. In France the Michelin brothers, Édouard and André, pioneered the use of rubber for vehicles. In 1891 they patented a tyre for bicycles that could easily be removed and repaired. With the coming of automobiles, the limitations of solid tyres were shown up: they tended to break the wheels at speeds of more than 15 mph (25 kmph). Pneumatic car tyres were the answer, and in 1895 the Michelins demonstrated one. Although the tyres had to be changed every 150 km (90 miles or so), the world was convinced that this was the way forward.

Tyres, though important, are just one of a host of uses for rubber. Automobiles and most other modern machines contain rubber in hoses, fittings, washers, cable insulation and numerous other parts. It is also still used for boots and shoes, gloves, condoms and much else. All this encouraged chemists to examine the molecular basis of rubber’s distinctive properties. The German chemist Hermann Staudinger showed that the substance consisted of polymers (long chains) of hydrogen and carbon, and that vulcanization, by adding sulphur, resulted in stabilizing chemical bonds. He won a Nobel Prize for his work in 1953. Although synthetic rubber is now widely used, it cannot replace the natural material for some purposes; and natural rubber is of course renewable. Brazil now produces little rubber, but the Malay Peninsula is still a major player, with China also in the game.

Musa acuminata × balbisiana

There is another tree in India, of still larger size, and even more remarkable for the size and sweetness of its fruit.… The leaf of this tree resembles, in shape, the wing of a bird, being three cubits in length and two in breadth.

Pliny, 1st century AD

Bananas are large perennial herbs; the false stem is formed from the leaf sheaths. The vast leaves have a long history of use – from roofing to wrapping to umbrellas – and some varieties are now grown in southern India for disposable ‘biological plates’. For thousands of years bananas were propagated by dividing and planting the small ‘pups’ at the base, but successful tissue culture techniques have now been developed.

Bananas have become so ubiquitous and cheap that it is hard to appreciate that, before the 1870s, they were virtually unavailable in temperate lands and were mostly consumed at source. They originated in Southeast Asia, but the wild variety had seeds and produced little that was edible; the non-seeded, edible variety, probably a natural hybrid, has long been prized in Asia and its islands. The plant needs warmth and plenty of water (it will not grow naturally except around 30 degrees north or south of the Equator), and thrives on well-drained, rich soil. The distinctive huge leaves emerge from a large single stem. The male flowers are sterile, while the female (or hermaphroditic) flowers produce the fruits.

Because the fruit of this large herb lacks seeds, it must be propagated from lateral shoots (suckers or ‘pups’), and by this means was widely spread throughout Asia and the Malay Archipelago. It reached as far as Hawaii, and Muslim traders may have introduced it into Africa (it could have been introduced even earlier via Indonesia), where it became a mainstay of the diet. Its mode of propagation means that new cultivars cannot be bred, although several natural varieties exist, the most common commercial one being Cavendish, developed in the Victorian hothouse of the Duke of Devonshire in 19th-century England. The fact that bananas are clones means they are especially susceptible to pests and diseases, a real worry in the modern world. A previous widespread commercial variety, named Gros Michel, was badly affected by a fungus in the 1930s.

Before the European age of exploration bananas had been spread throughout Asia, Oceania and Africa. The Portuguese then introduced them to the Canary Islands, and from there they were taken to the Caribbean, where their main use was as food for African slaves. The plant has the value of yielding its fruits continuously throughout the year and is one of the heaviest producers in the plant kingdom; the fruits are rich in carbohydrates, contain high levels of potassium and are a good source of vitamin C.

Bananas don’t travel well, however, and needed more rapid sea transport and refrigeration to become readily available worldwide. Several American companies, including United Fruit and Del Monte, quickly exploited and dramatically extended the plantations in the Caribbean islands and Central and South America. A British company, Fyffes, a partnership between an importer and a shipping magnate, did the same with the West African countries and the British market. The shipper, Sir Alfred Lewis Jones, gave away bananas to people on the Liverpool docks when his ships came in, to encourage potential customers to acquire a taste for this new fruit. These entrepreneurs established the banana as an all-year-round fruit at a time when many Europeans were seasonally limited in what they could eat.

The French Plantain (Musa × paradisiaca), here from Berthe Hoola van Nooten’s Fleurs, Fruits et Feuillages choisis … de l’île de Java (1863), is found in Indonesia and the Pacific islands. Plantains can be eaten at various stages; unripe they are starchy, becoming sweeter as they ripen. Dried for later use, they can also be ground into flour.

In tropical countries bananas continue to be important local edibles, and in India the whole plant is consumed in different ways. Although mostly eaten raw in the West, bananas are often cooked in many parts of the world. In addition, plantains are also widely used in Africa, Asia and the Caribbean. They have a slightly different chromosomal arrangement, but are of the same species as the familiar yellow banana. Plantains are generally cooked and are equally nutritious.

Elaeis guineensis

Economics Versus the Environment

Keep that wedding day complexion.

Advertisement for Palmolive Soap, 1922

The oil palm is indigenous to the tropical rainforests of West and Central Africa. A tall, long-lived tree – it can attain up to 30 m (98ft) high and 150 years in age – it bears large clusters of fruits about the size of a plum. Before commercial exploitation in the late 19th century, the fruits were mostly gathered from wild or tended trees, and people had long discovered ways of processing the abundant oil they contained. The traditional oil, made from the fruit’s flesh, is red in colour and was used locally in cooking, but did not travel well. Consequently, the first Europeans who encountered it described its properties but saw little potential value abroad. However, it was probably traded from early times within Africa, perhaps as far north as Egypt.

After harvesting and separating the seed or kernel, the fleshy part of the fruit is softened, pressed and the resulting palm oil purified. These traditional steps have been much improved by modern production methods but are still essential. Another oil is made from the kernels, and these are often exported whole for processing in the country of consumption.

As well as use in cooking, palm oils were found to be suitable for soaps, perfumes and margarine, and European demand grew. At the heart of international interest was William Lever, an entrepreneur who, with his brother James, established Lever Brothers, now part of Unilever. They began exporting palm oil from British colonies in Africa, but when securing more land for plantations proved difficult they moved the centre of operations to the Belgian Congo (now Democratic Republic of Congo, DRC). Lever combined shrewd advertising with the use of the vegetable oil in producing and selling cheap soap. Although a notable philanthropist – he built Port Sunlight as a model village for his workers in England – he also exploited cheap labour and profited from appalling working conditions in Africa.

The increasing popularity of margarine, developed in France in 1869 as a cheaper alternative to butter, led to a demand for vegetable oils. Palm oil needed less treatment than other oils, so became the product of choice. New transport methods eased its shipment and this in turn led Western entrepreneurs to look elsewhere for its commercial production. Java was the first new area, pioneered by the Dutch; it was a success, especially after the chance introduction of a new variety. Soon Indonesia and Malaysia were added to the list. Malaysia is now the world’s largest producer of palm oil, the downside being the destruction of much rainforest and with it the traditional home of the orang-utan. A distinct species of oil palm is found in South America (E. oleifera), which is employed locally but not for large-scale production. The African species is now grown there commercially in several countries.

The African oil palm, with its male and female flowers, fruit or drupes, and seeds. The expansion of oil palm plantations in Indonesia exemplifies the tensions between providing income for poor farmers and an export crop for a developing country, versus environmental degradation. Such concerns did not trouble the colonial planters who established oil palm as a cash crop.

Palm oil is low in free fatty acids (FFAs) and so is attractive to Western health-conscious consumers. Modern production is graded according to its percentage of FFAs, with the lowest reaching a premium. The oil withstands high temperatures for frying and can form the basis of ‘healthy’ margarines, containing vitamins A, D and E, and two essential acids.