Plant Aesthetics on the Grand Scale

Flowering branch of Eucalyptus resinifera, native to the coastal regions of eastern Australia. It is more tolerant of shade than many gum trees and is a popular plantation eucalypt.

Plants make living landscapes; they colour and shape the ground on which they grow. Forests can be ‘impenetrable’ and the stuff of dark legend. Grasslands are ‘sweeping’, taking the eye to the far horizon. Plants punctuate desert landscapes and can define the boundary between land and sea. Shaping the environment en masse, landscape plants have provided an aesthetic that has been captured in art and literature. In the East, landscape painting is the most highly regarded style.

How have such plants moulded the planet? How have we adapted their landscapes for our own ends and utilized the products that these plants offer? The stately larches straddling the continents of the northern hemisphere are an important component of the great boreal forests. They have myriad uses reflecting the cultures they help shape: snowshoes for the winter months, lumber for building and exquisite Japanese bonsai. The utility of the productive timber of North America’s giant redwoods vies with their impact on the emotions, exploited today through tourism. The remaining stands in California are perhaps a relic of a much wider forest, already ancient before man moved in with the axe.

Eucalyptus or gum trees, adapted to survive and even benefit from bush fires, typify the unique Australian plant heritage, and their essential oils are enjoyed. They are also now part of the new landscape of commercial tree production around the globe. Outside the plantation, the Tasmanian Blue Gum has become an invasive weed in parts of California, crowding out native plants and creating a monoculture, reminding us how we sometimes alter and manipulate landscapes with unexpected consequences. The trees do, however, support bees and hummingbirds, and prevent soil erosion. Some rhododendrons too have gained a poor reputation. But clothing their native hillsides, with the white masses of the Himalaya as a backdrop, their colours are spectacular.

Left Rhododendron nuttallii – described in Curtis’s Botanical Magazine (1859) as the ‘Prince of Rhododendrons’. This small tree (10 m/33 ft) is topped by glorious, scented white flowers, the largest in the genus.

Right The intrepid artist Marianne North captured the verdant richness of the mangrove swamp in Sarawak, Borneo (1876; detail). She traversed the country wearing rubber boots, with her skirts hitched up to her knees, and often used a boat – perhaps when she created this view from the water.

The dramatic tree-sized cacti of the American West are plants capable of life under extreme conditions. These icons of the movie industry have a longer history in the desert culture of Native Americans. They serve as a reminder of the clash of cultures as Europeans moved west across the continent. Mangroves demonstrate the peculiar plant characteristics of a life in brine. They thrive at the boundaries between land and sea, holding the two apart and preventing coastal erosion by some astoundingly beautiful adaptations. The Māori, original inhabitants of the islands of New Zealand, adopted the silver tree fern as a plant of special significance. The trunks were used for timber, while the fronds made a bed. The silver undersides, cut and laid to catch the moonlight, pointed the way – a vegetable means of communication.

Larix spp.

Stately Conifers of the Northern Forests

We continued along the most extensive larch wood which I had ever seen,—tall and slender trees with fantastic branches.

Henry David Thoreau, 1864

The boreal forests are striking features of the landscapes of the northern hemisphere. They constitute the largest forest area in the world, and are so extensive that they have long had a significant ecological impact on climate and carbon dioxide levels. Like most forests, they contain a mixture of vegetation, but larches and other conifers dominate. They love the cool of the mountains and cannot stand wet, frozen, low-lying soil, so their reaches have waxed and waned over many millennia as temperatures and the extent of the Arctic ice have varied. Larches range widely in North America, central and northern Europe, and in Asia, from the Himalaya to Siberia and Japan. They are unusual among the conifers (‘cone bearing’) in being deciduous, with their leaves, ‘needles’, turning colour and falling in winter. Conifers are an ancient botanical group, dating back about 300 million years, and most, such as pines, are evergreen.

Larix is a relatively small genus of about a dozen species; the trees themselves are generous in size (30–50 m/98–165 ft) and fast growing. The seeds develop in the attractive crimson cones, which remain behind after the seeds are shed. The mature cones differ in each species, so are essential for botanical classification. Larch trees’ fast rate of growth has made them valuable sources of fuel, and although the wood is soft, it is unusually durable – its high resin content helps make it watertight and it will not rot in the ground. This has made it a favourite for fencing, pit supports and general building purposes. It is also slow burning and deemed a good material for smelting iron. The Romans used larch to build ships, and the tradition has long continued, with Scottish trawlers and luxury yachts still built of the wood. Russians and Siberians depended on the tree to construct their houses and to warm themselves. Native Americans used it long before European settlements. Hackmatack or Tamarack are indigenous names for larches, and mean ‘wood used for snowshoes’. Larch turpentine, obtained by tapping, has been advocated in both human and animal medicine.

The primary species of larch are divided into two groups on the basis of leaf markings. They are also usually familiarly known by their principal locations, for example Japanese, Siberian, European or Western (in North America). Not surprisingly for a plant with multiple uses, larch has been transplanted successfully. The first larch trees were probably planted in Britain only in the 17th century. The London diarist and plantsman John Evelyn travelled to Chelmsford in Essex where he admired a European larch (native to the Alps).

A branch of the European larch with cones (male, bottom left; female, bottom right). Male cones appear as bright green tufts on the branches along with the new season’s needles (detail in the top left). As with all gymnosperms the seeds are bare, not encased in a fruit or vessel, although protected by the cone.

One of the most striking ‘larchfests’ – the spectacle of seeing the glorious autumnal colours of larches, often among other, darker evergreens – was that masterminded by the Dukes of Atoll on their estate at Dunkeld in the Scottish Highlands. In the mid-18th century, John Murray, the second Duke, planted about 150 decidua larches (the ‘European’). His son and grandson continued the practice, resulting in millions of trees on the estate, often on agriculturally worthless land. In 1895 a cross between the Japanese larch (kaempferi) and decidua was made. This was especially vigorous and healthy, and is now known as the Dunkeld Larch – it is the commonest commercial larch in Britain and is valuable throughout the world. At the opposite extreme, the larch is a favourite tree for bonsai.

Sequoia sempervirens

The redwoods, once seen, leave a mark or create a vision that stays with you always … they are not like any trees we know, they are ambassadors from another time.

John Steinbeck, 1962

‘The coldest winter I ever spent was summer in San Francisco’, said someone, even if it wasn’t Mark Twain, and there’s no denying the chilling damp of the coastal fog. It forms when the air above the cooler waters of the California Current comes into contact with the warmer landmass. This weather pattern perfectly suits the coastal redwood trees (Sequoia sempervirens). These ancient conifers are the world’s tallest trees today – the record is held by the Hyperion, at 115.5 m (379 ft) high. The biggest trees, measured by volume rather than height, are the closely related giant redwoods (Sequoiadendron giganteum) of the western Sierra Nevada, California.

The redwoods run down the Pacific coast in a strip 8–56 km (5–35 miles) wide, from southwestern Oregon to just south of Monterey, California. They usually grow up to an altitude of about 300 m (985 ft), although some are found higher; the foliage cannot tolerate high or freezing temperatures. Redwoods and other conifers have their antecedents in the great conifer forests of the Jurassic, before the flowering plants began their successful radiations. Older, fossilized ancestors very similar to S. sempervirens are found over the western United States, northern Mexico and along the coasts of Europe and Asia (the other close living Sequoia relative, the dawn redwood, Metasequoia glyptostroboides, is found in a small region of Sichuan-Hubei province in China). So this coastal strip, a large but circumscribed area, is probably a relic of a once much more widespread population. Redwoods are now grown in many other areas of the world as ornamental specimens.

Only a very small proportion (estimated at 5 per cent) of the redwood’s range consists of original, old-growth wood. The redwoods have been highly prized for timber, which is lightweight and resistant to decay, since the Spanish settled in the 18th century, but it was the gold rush of 1849 that began the serious inroads into the forests. Concern to preserve the majesty of the redwoods led to the founding of the Sempervirens Club in 1900 and the Save the Redwoods League in 1918. Protected areas quickly followed, but the loggers continued to cut. Tensions between the timber trade and the conservationists remain, although today the decline of coastal fogs adds a new threat. The trees’ height and water requirements mean that the drier, warmer climate poses a serious problem. Redwoods were the first trees in which the drawing in of moisture through the stomata (pores in the leaves) was appreciated. They also capture water and dissolved minerals from the fog, which then drips on to other members of their ecosystem.

Before the advent of steam-assisted machinery, the felling, moving and transforming of sections of redwood tree trunks into usable lumber in the sawmill was close to the limit of human capability. It could take a two-man team six days, working 12 hours a day, to cut a single tree. In Marianne North’s painting Under the Redwood Trees at Goerneville, California (1875) the hut gives an idea of the scale of the trees.

Most people view the redwoods by looking upwards, but there are a few extreme botanists who have taken to the trees. They have opened up a new world in the canopy some, 90 to 105 m (295–345 ft) above the ground. Nestling in trees, some of which have been alive for 2,000 years, are more than 180 species that never touch the ground, including ferns, huckleberries, even rhododendrons, rooted in centuries-old accumulations of litter. Lichens and mosses also thrive, along with salamanders, slugs, bees and beetles. The canopy is welded together by fused secondary trunks that arise from branches, likened to the flying buttresses of the medieval churches built when these trees were already in middle age. Redwood regeneration can be vigorous – rings of trees spring from the roots of a long-dead central plant. Long may it continue.

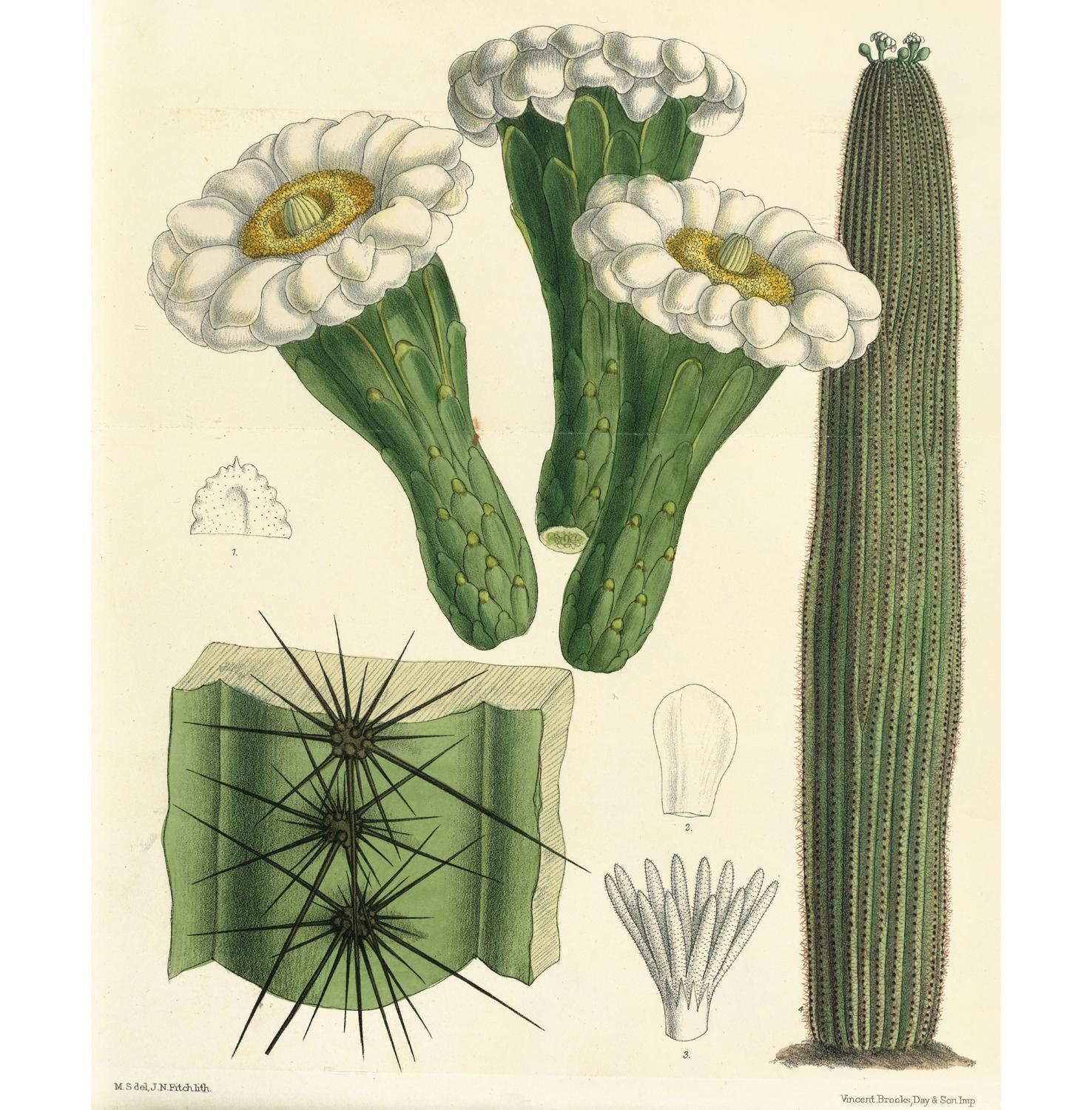

Carnegiea gigantea

I will turn into a saguaro, so I shall last forever, and bear fruit every summer.

Myth of the Pima Native Americans

Detail from Marianne North’s Vegetation of the Arizona Desert (1875). North’s individualistic work has been criticized as satisfying neither the requirements of botanical illustration nor the high art of the later 19th century, but she has certainly captured the saguaro cactus as part of this unique landscape.

Set in the silver-mining boomtown of Tombstone, Arizona, in the early 1880s, My Darling Clementine (John Ford, 1946) is one of Hollywood’s classic Westerns. It culminates in a famous shootout: the gunfight at the O.K. Corral. Ringing the town, and providing an iconic backdrop, are saguaro cacti, mute witnesses to a formative period of America’s human history. Their own past in this exceptional scenery is written in geological time.

Cacti are primarily New World plants. They exhibit the classic suite of adaptations – the ‘succulent syndrome’ – of arid landscapes. The saguaros have immense stems, which can photosynthesize and store huge quantities of water from the brief summer rains. They use a special type of photosynthesis (Crassulacean acid metabolism), which sees the uptake of carbon dioxide at night, thus minimizing water loss through the stomata during the day. Anchored by a taproot, they also have a network of smaller roots near the surface ready to absorb any water when it does rain. A thick, waxy cuticle covering the plant, and leaves reduced to whorls of spines also help to cut down water loss. The spines deter larger herbivores and provide shade for the stem.

The tall (over 15 m/50 ft) and columnar saguaro cacti are stately, unhurried plants, living for 175–200 years. Slow to reach flowering maturity (30–35 years and at 2 m/6½ ft high), only at 50-plus years old do the candelabra-like branches begin to appear. The plants produce flowers on the stem tips – more stems means more flowers and increased reproductive success. From April to June, the white, waxy, funnel-shaped blooms open at night, releasing a ripe-melon fragrance to attract their nocturnal pollinators, the lesser long-nosed bats. White-winged doves and insects take over the next morning, before the flower fades. Each blossom lasts only 24 hours. The red fruits with their numerous fat-rich seeds follow from May to July. They are a useful food source for a range of animals including the Gila woodpeckers, which make their home in the stems, pecking in and down to form a pocket. Once these are vacated by the woodpeckers, elf owls move in. In response to an injury, saguaros form a hard callous around the wound. When the plant dies, these nesting boxes remain and are known as ‘saguaro boots’.

Arborescent (tree-like) saguaro cacti are part of a unique flora concentrated in the Sonoran Desert – they live nowhere else but here and in places form groves. It is thought that the central Mexican ancestors of the saguaro responded to and evolved with the desertification of the region, 15 to 8 million years ago. They are an intimate part of the biome, connected with other plants such as the palo verde ‘nurse trees’ that protect saguaro saplings until they outgrow and outlive them.

For much longer than today’s tourists and yesterday’s gunslingers, the Native Americans in the Sonora region have celebrated and utilized the saguaro. Using a woody rib from a dead plant, the Pima and Tohono O’odham peoples harvest the fruit, eat it fresh and save the seeds for grinding into meal. They also make a syrup, which is fermented into wine to be drunk at rain ceremonies; an age-old celebration of the renewal of life in the desert.

Saguaro cactus from Curtis’s Botanical Magazine (1892). Joseph Dalton Hooker reported proudly of the saguaro in the Kew Palm House that ‘the flowering of this wonderful plant in England must be considered one of the triumphs of Horticulture’. Cacti took their place among the exotics in botanic gardens and collections of wealthy amateur growers.

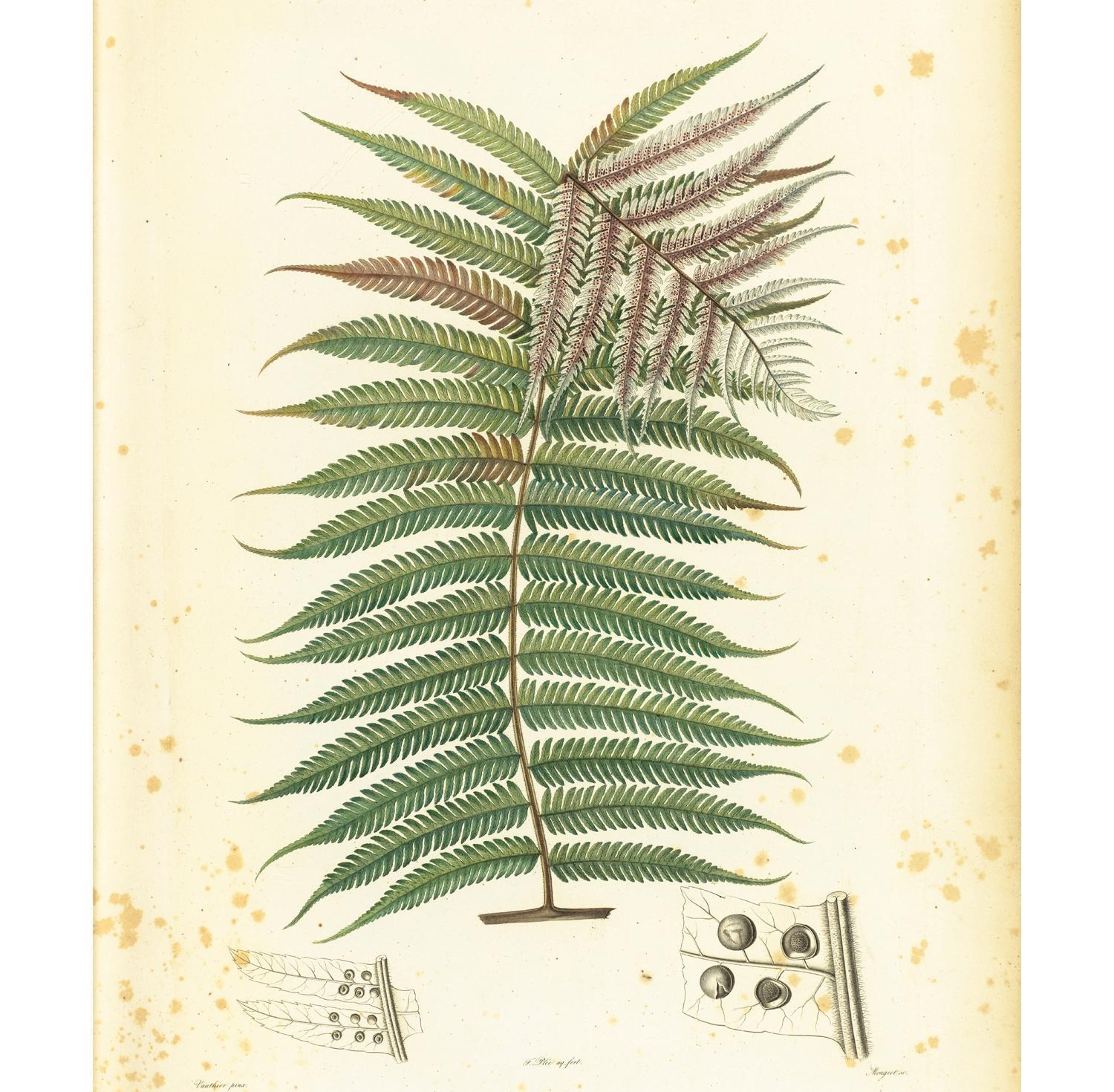

Cyathea dealbata

Ponga ra! Kapa O Pango, aue hi! [Silver fern! All Blacks!]

All Blacks Rugby Team, New Zealand, pre-match haka, 2005

New Zealand separated from Australia about 80 to 100 million years ago, giving the islands plenty of time to develop a special flora and fauna. They were so unusual in fact that when Sir Joseph Banks visited in 1769 with James Cook on the Endeavour, he recognized only 15 of the first 400 plants he examined – 89 per cent of its native flora is exclusive to New Zealand. The animals were once equally exotic, some of them already extinct before the Europeans arrived.

Ferns, which with related plants constituted more than 12 per cent of New Zealand’s flora, are very old: evidence of their ancestors dates from the middle Devonian period (around 385 million years ago) and tree ferns are present in the mid-Triassic (around 235 million years ago). Today ferns exhibit a vast variety of form and habitat, but they have changed so little through evolutionary time that one of their primary biological uses is to study the basic mechanisms of life in early forms. Although ‘trees’ in size and general appearance, tree ferns rarely branch and do not have true bark, instead being protected by the roughened bases of old fronds, often with an additional covering of lichens, moss or other organisms. Their root system is very compact, which means that larger examples (up to 25 m/80 ft) generally must be supported by adjacent plants. Like other ferns they reproduce by spores formed on the back of their fronds. The two principal genera of tree ferns are Dicksonia and Cyathea, both highly successful and widespread in their geographical distributions.

The silver tree fern, C. dealbata, is one of a number in New Zealand, but was especially prized by the Māoris, who permanently settled the islands from East Polynesia in around AD 1250–1300. It can grow as high as 10 m (33 ft), with fronds 2–4 m (6½–13 ft) long radiating from the top. Known as kaponga or ponga to the Māoris, the silver tree fern takes its English name from the whitish-silver underside of its fronds, which can give the plant a majestic appearance in moonlight. Traditionally, this characteristic was exploited by laying the fronds upside down on the ground to mark trails in the dark. The Māoris also used the plant for building rat-proof food storage houses and making utensils. The tough, durable trunks have since been employed in fencing and landscaping and for making vases and boxes. The pith and young fronds can been cooked (the Māoris did so), and medicinal recommendations include a wound dressing for easing boils or cuts and a treatment for diarrhoea.

The silver tree fern was part of the fern craze – pteridomania – that swept Victorian Britain and to some extent North America. Specialist dealers arose and their wares fetched high prices as wealthy people in the northern hemisphere hoped to meet the challenge of growing exotics out of their natural environments. The silver tree fern occurs unevenly throughout New Zealand’s islands, and all tree ferns need to be protected against export for gardeners and habitat loss for a variety of reasons. In New Zealand, C. dealbata has become a national icon, its distinctive silver leaves gracing the black jerseys of the national rugby union team, the All Blacks.

Frond (with spore details) of New Zealand’s silver tree fern, from the Voyage de la corvette L’astrolabe exécuté pendant les années 1826–1829 (1833). This voyage was the first of two French expeditions to the southern hemisphere under Captain Dumont D’Urville which were immensely important for bringing back new material to European collections.

Eucalyptus spp.

Kookaburra sits in the old gum tree.

Marion Sinclair, 1932

Eucalypts are Australia’s major source of hardwood. Not surprisingly in the colonial period, when many viewed the tropics as virgin territory for plantations of all kinds, these trees were trialled in botanic gardens (this photograph was taken in Bogor, Java). Like all non-indigenous species, eucalypts can become serious invasive nuisances.

Eucalyptus is a large genus of trees, with about 500 species that come in a great variety of sizes and shapes. Native to Australia and a few Pacific islands, they are now to be found worldwide, so adaptable are they. A number of common names such as gum trees (of several types), peppermint trees and bloodwood trees are indicative of their many characteristics and uses.

Eucalyptus trees evolved several million years ago, when Australia was already separated from the larger Asian landmass but was much wetter than it has since become. As conditions in Australia changed, several members of this resilient genus developed adaptations that have permitted it to become so widespread and dominant. First, very deep and extensive root systems allow trees to survive where surface water is scarce. Second, it can thrive after forest fires, often caused by lightning. Firing actually helps the trees’ seeds to germinate and the ash-rich forest floor offers the perfect conditions for a new crop of eucalyptus saplings. In addition, buds just below the bark of a mature tree are stimulated by fire, so the eucalyptus can rise Phoenix-like from the ashes. So many species of the genus adapted that there was hardly an ecological niche in Australia that it could not colonize. One species, E. regnans, is the tallest flowering tree in the world, and the eucalyptus regularly towers over its competitors in forests.

The Aborigines exploited the eucalyptus, making from it spears, boomerangs and rough canoes. After Europeans settled in Australia from the late 18th century, the tree’s vigour and range of applications were recognized and it was exported to many other parts of the world. There are specimen trees virtually everywhere and commercial plantations in Brazil, the United States, northern Africa and India. Many species are extremely fast growing – saplings of some can reach 1.5 m (5 ft) in the first year, and 10 m (33 ft) by their tenth – and make excellent firewood. Indeed, the biomass obtained from an acre of eucalyptus rivals that of any other tree. By planting it in marshes its efficient water uptake has been used to drain wet places, and its volatile gums are disliked by mosquitoes, further helping malaria control.

Eucalyptus yields a number of valuable products. Its oils are a distinctive feature of the trees’ adaptive mechanisms and some, such as eucalypol (cineole), are used medicinally and occasionally in perfumes. The Blue Mountains near Sydney take their name from the pungent haze created by the extensive eucalyptus stands there. The leaves, bark and fruit, for example in E. gunnii, yield a variety of pigments that are used in dyeing, and the genus is an important source of tannin. The trees make good windbreaks while the hard woods can be employed in making musical instruments and they are a central core of chipboard; the pulp is a major ingredient in paper manufacture.

The flowers of Eucalyptus persicifolia from the Botanical Cabinet of the Loddiges nursery in Hackney, London. Part botanical periodical, part subtle advertisement, the fine plates were engraved by George Cooke. This ornamental eucalypt was grown in the nursery’s conservatory to protect it from frost; its rarity may have commended it to the discerning grower.

Although an extremely important commercial tree, eucalyptus’s aggressive vigour and spread around the globe give it a bad name among conservationists. Its success is aided by the fact that its oils make it relatively impervious to predators. One animal that can digest its leaves is the koala, a marsupial that evolved only in Australia, and the sight of these sedentary eating machines feeding on eucalyptus leaves is a famous icon of Australia’s unique ecology.

Rhododendron spp.

… three Rhododendrons, one scarlet, one white with superb foliage, and one, the most lovely thing you can imagine.

Joseph Dalton Hooker, 1849

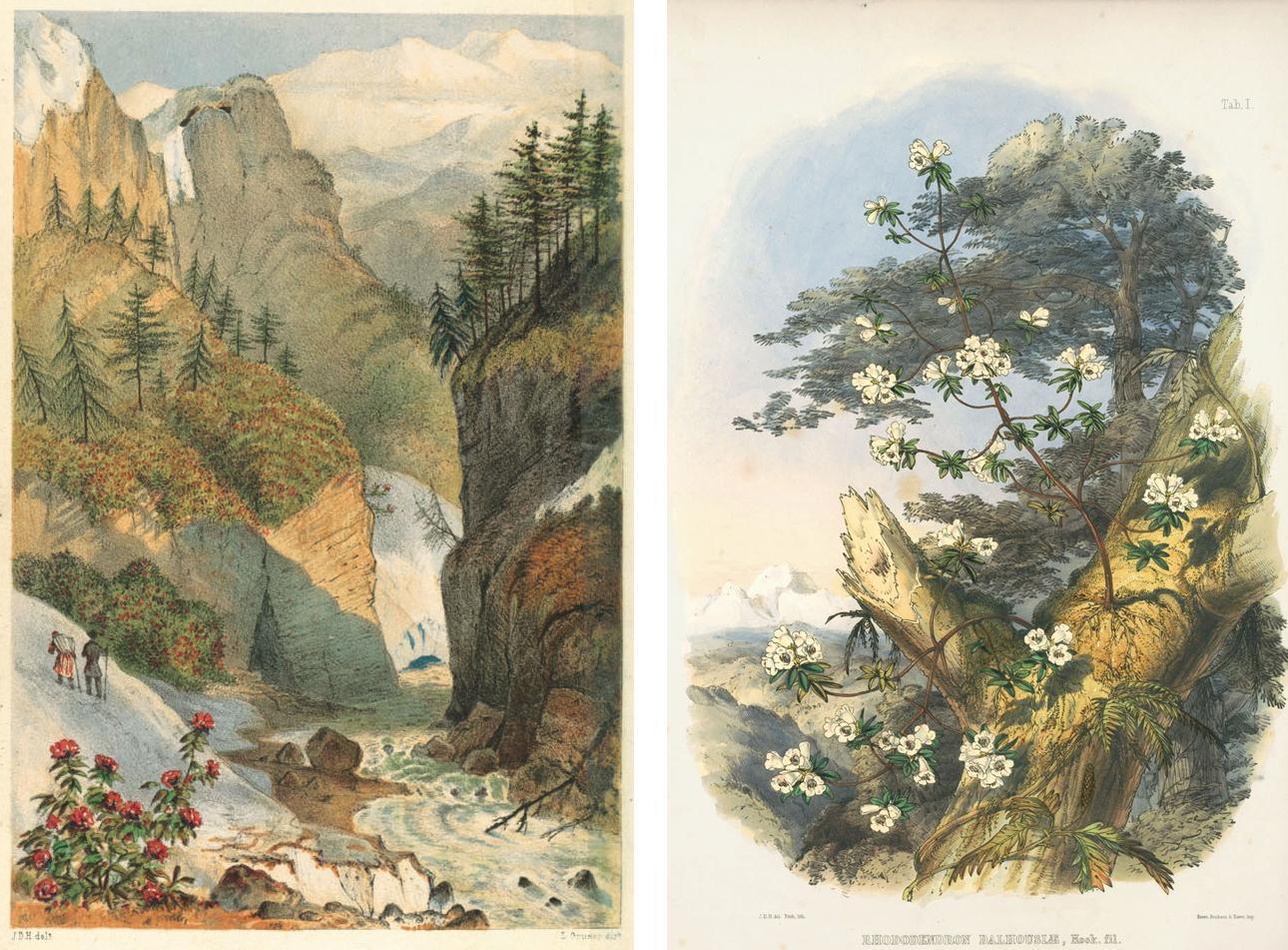

A taxonomic nightmare, the Rhododendron genus is one of the largest in the entire plant kingdom: it contains more than 800 species with probably still others yet to be described. Largely a northern hemisphere plant, although Australia has its own species, rhododendrons vary enormously in size, shape and habitat. Some are tiny Alpine-like plants, others substantial trees up to 30 m (around 100 ft) tall, such as the aptly named R. giganteum. They can form dense, luscious tropical landscapes and are found in the high Himalaya at the extreme limit of vegetation. They can even be epiphytes, growing on other trees. Their root systems are usually compact, although in drier climates some species have more spreading roots. Almost all share one characteristic: they need acid soil.

With many species exhibiting striking, waxy, deep green leaves and spectacular, often fragrant blooms in a broad spectrum of colours from light pastels to deep crimsons and even blues, they have become plants for gardens as well as landscapes. A small eastern European species was cultivated in the early 17th century, and the French naturalist and traveller Joseph de Tournefort admired R. ponticum in Anatolia in the early 1700s. European fascination began in earnest with the discovery of North American species that were brought back to Europe throughout the 18th century. When Linnaeus classified rhododendrons he placed azaleas in a different genus, but the two are now grouped together, with azaleas occupying several subgenera of the larger grouping. Equally prized in modern gardens, azaleas are generally deciduous or partly deciduous and are smaller and less aggressive than their cousins.

When Joseph Dalton Hooker was botanizing in India, including the Himalaya, in the late 1840s, he was astounded by the rhododendron landscapes. He identified 28 new species in Sikkim alone, describing them in his magnificent book, The Rhododendrons of Sikkim-Himalaya. It was Hooker who systematically investigated the geographical and morphological range of this giant genus, and he continued to study them after his return to England, where he succeeded his father William Hooker as director of Kew Gardens. Between them, they introduced a few Asian species to Britain, and then to Europe and North America, although most Asian species have been introduced in the past century, many from western China.

Left ‘Snow beds at 13,000 feet, in the Th’lonok Valley: with Rhododendrons in blossom, Kinchin-junga in a distance’: the frontispiece to Joseph Dalton Hooker’s Himalayan Journals, vol. 2 (1854). Hooker was captivated by the scenery and plants, but noted the scent could be ‘too heavy by far to be agreeable’.

Right ‘Rhododendron dalhousiae in its native locality’ served as the frontispiece to Hooker’s The Rhododendrons of Sikkim-Himalaya (1849–51). Hooker’s foray into the eastern Himalaya yielded 25 new rhododendron species. For the book, Hooker’s original artwork was transformed into superb lithographs by Walter Hood Fitch.

Since rhododendrons hybridize easily, new varieties have been regularly developed, as new characteristics were sought, including greater hardiness, flower colour or size. Often it has been a case of East meeting West. For instance, an early British hybridization, from 1814, crossed a Turkish variety (R. ponticum) with an American species (R. periclymenoides).

Rhododendrons grow well where conditions are roughly similar to the soil and temperature of their native habitats. Like many plants bred for gardens, they suffer from a variety of pests and diseases, but this did not deter fascination among gardeners. Those without the necessary acid soil often imported peat, depleting ancient peat bogs. At the same time, several species, particularly R. ponticum, formerly used as the basic grafting stock, have naturalized easily and spread rampantly, creating new, unlooked-for landscapes. In Scotland pigs are employed to forage in unwanted rhododendron stands to weaken the root systems and help keep the plants under control. Although largely ornamental, rhododendrons (like virtually every other plant) have been used medicinally, especially in Asia, and sometimes the young leaves are cooked.

Rhizophora and other species

The red mangrove grows commonly by the seaside, or by rivers or creeks. The body … always grows out of many roots about the bigness of a man’s leg…. Where this sort of tree grows it is impossible to march by reason of these stakes.

William Dampier, 1697

Swathes of mangrove forests cover some 15,000,000 ha (37 million acres) around shorelines in the tropics and subtropics. A diverse group of specialized plants, around 70 species and hybrids of trees (up to 30 m or 100 ft tall), shrubs, ferns and a single palm are considered ‘true’ mangroves, of which 38 are ‘core’ species dominating the forests. Mangroves form shoreline ecosystems and support a wealth of other plants and animals.

Their presence in the tidal littorals protects the edge of the land from the perpetual wearing of the sea, the ravages of storms and the effects of extraordinary events. On 26 December 2004 massive waves of immense height and speed were generated in the Indian Ocean, caused by a huge undersea earthquake. Nothing could entirely absorb the force of the waves where they reached shores, but damage was mitigated in inland areas behind intact mangrove forests. Where mangroves had been cleared, often to provide a reliable source of income for local people through shrimp farming, the devastation was extreme.

From the air the intertidal home of the mangrove forest is clearly demarcated: a verdant splash of green between the sea and the interior. But these plants are probably best seen, like seaports, from a boat. From the water it is possible to appreciate the adaptations that have allowed these plants to reside in this often muddy and unstable transitional zone between land and salt water, and the different morphologies of the mangrove forests.

Fringing mangroves live along narrow strips that follow the shoreline, lagoon or numerous channels cut by river deltas. Although they can cope with seawater, mangroves thrive where salinity is diluted by freshwater from rivers or high rainfall. In shallow basins, broader forests develop, sheltered from daily tidal ingress. Patchy ‘overwash’ mangroves inhabit islands or headlands that are inundated at high tide, making it difficult for leaf litter and other useful debris to build up.

Mangroves deal with the conditions in their brackish world in various ways. All reduce the amount of salt absorbed through the roots as much as possible; Rhizophora are keen excluders. Others, including Avicennia, excrete it through salt-secreting glands that leave characteristic crystals on the leaves. A third group of plants allows the salt to build up in the leaves and then sheds them as necessary. Regeneration of mangroves is essential for the health of the forest, but the shifting bottom and movement of water make treacherous settings for seedling growth. To get around this, the plants have developed various means of allowing seeds to germinate while still attached to the parent. The resulting propagules can become quite large, those of R. mucronata are a metre (3 ft) in length.

The leaves and propagule of the red mangrove (Rhizophora mangle). Red mangroves are indigenous to the western coast of Africa, and the eastern and western coasts of subtropical and tropical America, between 28 degrees north and south of the Equator. Their ability to trap sediments helps filter the water, and by building up deposits into peaty soils they act as a carbon sink.

Mature plants must also cope with soft, waterlogged ground. Rhizophora employ stilt roots from high up the stem, like guy ropes; additional roots can descend from branches. Heritiera develop massive buttress roots over a large area to anchor the plants along typhoon-prone shorelines. Held fast, such large living structures must be able to breathe in the mud. Some have lenticels – the equivalent of leaf pores – on their stems. Breathing roots of various shapes and sizes – knee roots, peg roots – stick up from hollow horizontal roots on others. The fascinations of this landscape may come to their rescue, as the aesthetic as well as the practical potential of these plants is increasingly appreciated.