From the Sacred to the Exquisite

Orchis morio (or Anacamptis morio) – the green-winged orchid – one of the native British orchids Charles Darwin used in his experiments to determine the role of insects in pollinating these enchanting flowers.

Plants meet the needs of our senses and spirit as well as our bodies. The veneration of plants is evident in some of the earliest artifacts, and the mythology of ancient societies is replete with plant deities. The texts of today’s major religions refer to the importance and sanctity of plants. Nature worship, tree hugging, plant appreciation societies and flower festivals – all flourish as we continue to esteem plants for their varied meanings and associations, and the pleasures they bring.

The lotus is hallowed for its ability to grow in stagnant water and rise seemingly from the dead. It is a potent symbol of rebirth and purity; its iconic buds and opened flowers ornament the Hindu and Buddhist traditions. The rose is the quintessential flower of love. It is a mutable emblem that was favoured wherever it naturally grew. As different species were brought together from East and West, its very form changed over time. The pursuit of scented, repeat-flowering roses of myriad hues yielded a rose-fancier’s paradise.

The tipping point between a healthy passion and floral madness has happened more than once and in disparate parts of the world. Gorgeous peonies – the Chinese flower of riches and honour – sold for enormous sums in Tang dynasty China as gardeners vied to produce huge flowers. Risky plant-hunting expeditions were required to satisfy demand in the West. Orchids suffered at the hands of rapacious connoisseurs who sought new plants for their collections. On a more scientific level they also drew in those who wished to understand the often unique relationships of plant and pollinator. ‘Tulip fever’ raged during the Dutch Golden Age and led to an unsustainable futures market. The Dutch were consumed by the same passion as the Ottoman Turks, who had scoured and stripped the mountainsides of Central Asia for the smaller, delicate species tulips. Tulips inspired many artists, as did Chinese plum blossom, a harbinger of spring even as winter seems still to grip the landscape. Dainty flowers open before the leaves on bare stems – the delicate brush stokes needed to capture their fragile beauty honed the skills of many a fine painter and calligrapher.

Left The showy flowers (a double-flowered variety on the right) and developing fruits of the pomegranate, with the ripe fruit below, split to show the juicy arils in their compartments.

Right Two choice tulips, ‘Dracontia’ (bending to the right) and ‘Variegata’, from the Italian physician and botanist Antonio Targioni Tozzetti’s Raccolta di fiori frutti ed agrumi (1822–30).

And what was the forbidden fruit of Eden? Apples and pomegranates have both shared the epithet, and have links with fertility, immortality and abundance. Date palms too are symbols of everlasting life. These desert icons have long associations with the concept of the ‘tree of life’, their fruits succouring and sweetening and their leaves a potent symbol of peace. Sanctity and ritual purity are the attributes of frankincense, the dried gum of Boswellia trees. Burnt during religious rites for millennia, its scent is often essential to the shared experience of worship.

Nelumbo nucifera

Sacred Flower of Purity and Rebirth

When we can imagine ourselves free from guilt, we bloom as the lotus … in the summer dawn.

D. T. Suzuki, 1957

The idol ‘Pussa’ depicted sitting on her lotus in Athanasius Kircher’s China Illustrata (1667). Trying to make sense of the reports of Chinese Buddhist images, Kircher equated them with the Egyptian and Greek deities and so the Pussa becomes the Chinese equivalent of Isis or Cybele.

In the light and warmth of the new day the lotus bud unfurls its petals accompanied by the most discreet susurration. Through the day, the lotus’s delicious scent intensifies, attracting the pollinating insects that will spend a night within the closed flower. They are kept on the move by the warmth the plant generates. After three days the glory of this most bewitching of blooms begins to fade. The petals fall, leaving an iconic conical boss. This will swell and grow, tip on its side and, once mature, fall into the water, its contents having developed into bean-like seeds.

If the petals are ephemeral, the seeds have an astonishing longevity. Seeds dated to over a thousand years old have been successfully germinated. And the flower’s delicate beauty atop its stalk contrasts with the rhizome below, for this emblem of purity thrives in stagnant water. The circular leaves, supported on spiny stalks above the water line, have water-repelling adaptations on the upper side, which shrug off much of the rainwater that falls. What is caught in the dished centre is absorbed through a pore connected to special channels in the stem that continue through the rhizomes. This system provides additional water and a means of gaseous exchange. It is testimony to the lotus plant’s size that although water-dwelling, it needs yet more water. Capable of rapid growth, the lotus can quickly take over the shallows and marshes of rivers and lakes, producing massive clones.

All this has continued for millennia. What we see today as wild lotuses dotted in the warm temperate and tropical parts of Asia – Iran to Japan; Kashmir and Tibet through New Guinea to northeastern Australia – are relics of a once more widespread population. Over the span of geological time, following a rise to prominence in the Cretaceous, the lotus lost out in the desiccation of a colder, drier earth. Our love for the plant may have helped reinstate it.

In many of its native regions the lotus became indelibly associated with ancient cultures and their religions. Whenever they travelled, in conquest or to spread the word, people carried their lotuses, muddying the patterns of natural and artificial dispersal. Everywhere, this was a plant of rebirth. Its renewed growth in dry ponds after the rains endowed the lotus with a magical quality. The lotus has long featured in the life of Mesopotamia. It was associated with the cult of Inanna, fertility goddess of the city of Uruk, and reproduced in jewelry and on seals. The lotus-shaped sceptre was a symbol of ascendancy, maintaining its prominence through the region’s successive empires until Alexander the Great vanquished the Persian king Darius III in the late 4th century BC. Under Persian influence the lotus seems to have joined the existing blue and white waterlilies in the waters of the Nile in the first half of the 1st millennium BC, supplanting them in the rites of Isis. As the goddess of birth and renewal, Isis became a leading Egyptian deity in the receptive Greco-Roman pantheon.

‘Lotus’ – a watercolour painted in India between 1860 and 1870. Appreciation of the lotus extends across Asia and festivals celebrating the opening of the flowers have become important tourist attractions. Lotus ponds are part of the West Lake Cultural Landscape of Hangzhou, China, in an area of the Yangtze River delta that has been celebrated since the Tang dynasty and is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The lotus would also become crucially important to the beliefs of the Indian subcontinent. As recorded in the Vedas that underpin Hindu mythology, Vishnu and Lakshmi are central to the creation story. Afloat in the void on a giant snake Vishnu sprouts a lotus from his navel. The flower opens to reveal Brahma, who then sets to work to make the universe. Goddess of fertility and prosperity, Lakshmi is born holding, or like Brahma is seated on, a lotus. It becomes her flower. The lotus is no mere adornment. As the vedic canon developed, the ‘lotus of the heart’ became the container of one’s inner cosmos, the destination of the spiritual quest of life.

A late 19th-century Indian rosary made from the seeds of Nelumbo nucifera. The followers of all the major religions in India use rosaries, and they are often made of seeds, the sacred nature of the lotus perhaps making this an auspicious choice.

The lotus also bore the Buddha, just as it held the earth above the maelstrom of the universe. Buddhism in its various teachings spread from India to China, Korea and Japan, Tibet and Sri Lanka, adapting and taking on local associations, but the lotus remained a central image. It was cherished and cultivated for its essential symbolic role in the achievement of enlightenment. By seeking to rise as the lotus bud does from the mud (the evil of human ways) and to float above all worldly things, the follower of Buddhism could approach nirvana. The Lotus Sutra (c. 1st century BC) was one of the most important texts of Mahayana Buddhism, which espoused a simplified doctrine. In the 13th century AD, the Japanese Nichiren founded a school that further elevated this sutra.

‘Tamara of India’ from Richard Duppa’s Illustrations of the Lotus of the Ancients and Tamara of India (1816). The seeds in their central boss are clearly shown amidst the rosy petals. Duppa, trained in law, wrote on botany, art and politics, and spent time painting in Italy, combining his various skills in this engaging volume.

After the Meiji restoration (1868) and the opening of Japan to foreigners Japonisme became increasingly popular in Europe and America. The lotus was an integral part of this new fascination with the East, and was incorporated into Art Nouveau’s later repertoire of nature-inspired glass, ceramics, jewelry, furniture and fabrics. It is now grown wherever possible as an inspiring ornamental. Replete with spirituality, the lotus also nourishes the body. The rhizomes and seeds (and to a lesser extent leaves and flowers) are eaten throughout eastern and southern Asia, and the West is slowly waking up to the taste of these ancient beauties.

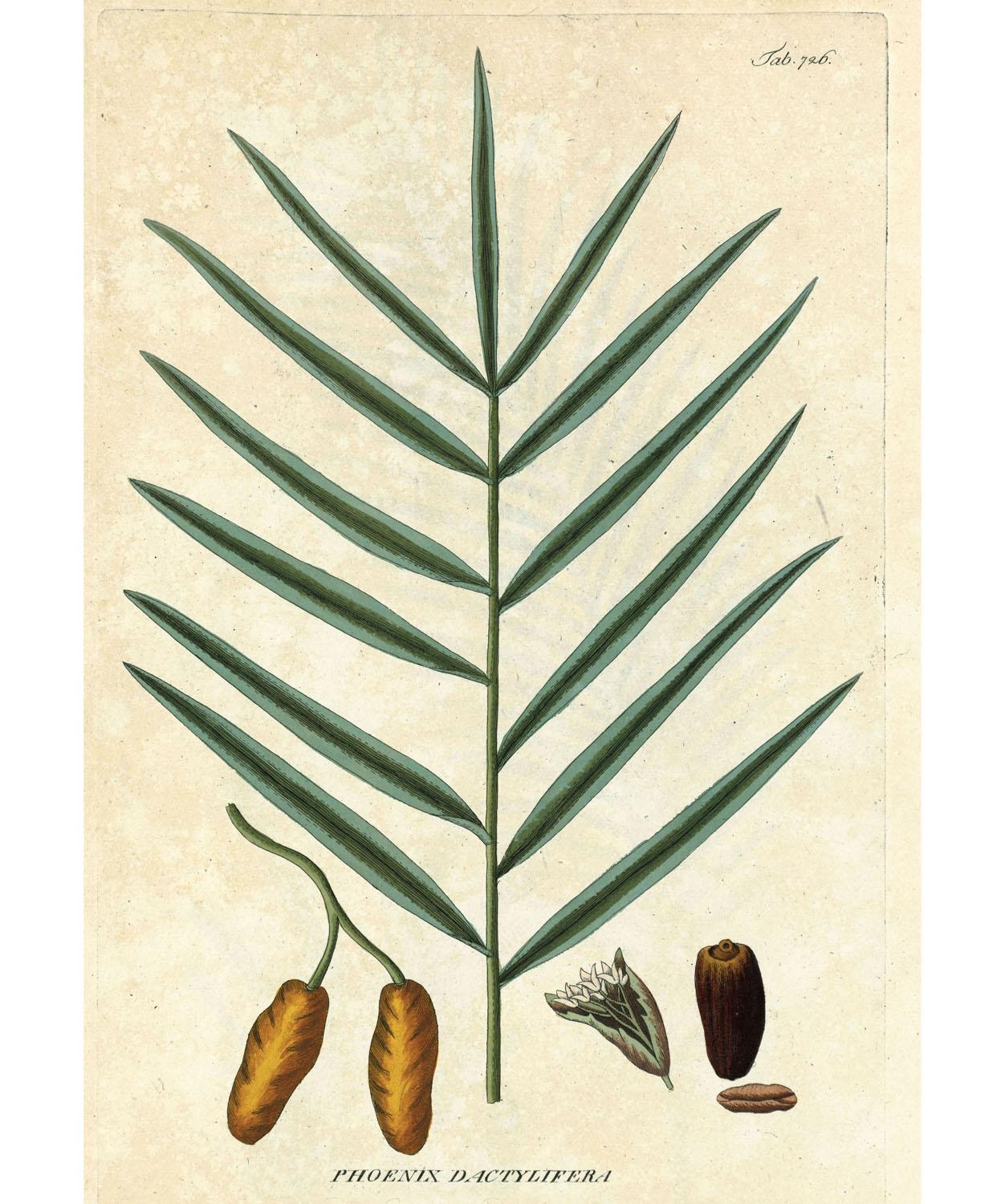

Phoenix dactylifera

Shake the trunk of the palm tree towards thee: it will drop fresh, ripe dates upon thee. Eat, then, and drink, and let thine eye be gladdened!

Qur’an 19:25–26

Engelbert Kaempfer travelled extensively in Russia, Persia and Asia in the late 17th century and wrote about his adventures in Amoenitatum Exoticarum (1712). He witnessed the caravans that arrived in Isfahan, Persia’s capital – the merchants had long enjoyed the nutritious combination of camel milk and dates.

The shimmering mirage of an oasis fringed with date palms has tricked many a thirsty desert traveller. The real tree succours and shades, and is found in rocky outcrops as well as the shifting sands of Southwest Asia and North Africa. The date is the lynch pin of the unique oasis ecology – the palms are nurtured by the groundwater that lies within reach of their roots and tolerant of some salinity.

With its tall, slender trunk up to 30 m (almost 100 ft) high, topped with a crown of fronds, the date palm also offers a protective canopy in irrigated plots. Beneath the palm there is room for fruits, cereals and vegetables, and other useful crops. Such ‘date palm garden’ agriculture, found from the early Bronze Age, around the early 3rd millennium BC in Mesopotamia, added to the date’s already considerable bounty. Sap from the stem can be drunk fresh or fermented to make date wine; palm pith makes flour and palm hearts serve as vegetables. The super sweet fruits, held high up in great bunches, are a cardinal foodstuff. When ripe and dry (varieties are classified by their softness and dryness) they are easy to preserve, wonderfully transportable and highly nutritious. When pressed, the fermented dates produce a syrup, the honey of the biblical ‘milk and honey’. The trunks, leaves, kernels and their oils serve as timber, roofing, fuels, multipurpose fibres – especially for basketry – fodder, caffeine-free ‘coffee’ and soap. Little wonder that the date palm was raised to divine status and has been identified with the trees of life, abundance and riches.

The Sumerians celebrated dates, using the iconic trees on their cylinder seals. The Egyptians created columns topped with palm capitals and the god of eternity, Heh, grasped notched palm branches used to record time. The date palm became a leading motif of the ancient world even in places where the climate prevented cultivation. In highly stylized form it featured in reliefs in the stupendous state apartments of the Northwest Palace at Nimrud built for the Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal II in the late 9th century BC.

The palm’s ancient association with everlasting life may relate to its ability to cope with fire damage (hence Phoenix), and to the regular growth of new fronds throughout the year. What would not have been so apparent is the special nature of the cells of the stem. These are not immortal but essentially last throughout the roughly 150-year lifespan of the tree. The date palm is best propagated from offshoots, which sprout at the base of the parent plant. These clones allow selection for female over male trees, since only the females produce fruit.

A frond, carried in the hand of the victor, was a mark of triumph in Greek and Roman athletic and other competitions. The date palm was also a significant symbol in all the monotheistic faiths of the Holy Land. Its fronds are an important element in the Jewish festival of Sukkot. Those who celebrated Jesus’ entry into Jerusalem greeted him with waving palm fronds, and early Christian martyrs are often depicted with one. According to Muslim tradition the date was made of the dust left over after Adam’s creation, and it spread with Islam to Spain. Among other instructions, Islamic armies were ordered not to destroy existing palm trees. Dates were an intrinsic part of the Arabian identity – traditional buildings on the Arabian Peninsula are still made from the leaves of date palms. And what could be more natural to break the month-long fast of Ramadan, each day at sunset, than these marvellous morsels of the desert?

Frond, flower and fruit of the date. The tradition of planting date palms in palace gardens in Persia is reflected in the fabulous garden carpets that were woven to provide eternal spring within.

Boswellia sacra

Trees have their allotted climes … to the Sabaeans alone belongs the frankincense bough.

Virgil, 1st century BC

A censor, wafting incense, stands next to a hookah, as recorded by Engelbert Kaempfer. In Christian rites, incense was used more in the Eastern Church than the Western, and Protestants dispensed with it after the Reformations of the 16th century.

Resins are both valuable and useful – think of amber, tar and pitch, turpentine and rosin. Many come from conifers, and some were appreciated for their scent. Other trees, too, were tapped for their fragrant resin, to be burnt as redolent incense, or used in medicines and as perfume. Among the most prized was frankincense (or olibanum), taken from the four species of Boswellia. Of these, Boswellia sacra was the most prestigious. A marvellous mystique enveloped the land of the Sabaeans (Yemen, Oman) where B. sacra grew – the air was said by the Greek Agatharchides (2nd century BC) to be permeated by the sweetest scents.

Gold, frankincense and myrrh (resin from Commiphora trees) are hallowed as the gifts presented to Jesus by the Magi. True or not, they represented three of the most valuable items of the time. By the mid-4th millennium BC frankincense was being imported into Mesopotamia, possibly from the southern Arabian Peninsula. The overland Incense Route may have stimulated domestication of the single-humped camel as beast of burden, and certainly by the late 2nd millennium BC desert communities were controlling the lucrative trade in aromatics and spices that crossed the sands to markets in Egypt, the Levant and beyond, ultimately as far as India and China. Towns en route enjoyed a healthy income from the taxes, and the Nabataeans grew rich on the trade, building their city at Petra. Frankincense was sufficiently valuable that those who sourced and traded the best resin wanted to keep the exact location of their trees to themselves. Historical authors confused matters, some thinking that juniper provided the pure incense of frankincense.

The flame, smoke and scent of incense were all significant in the rituals, sacrifices and oblations of many ancient cultures. Egyptians and Greeks shared a similar belief that the scent protected against evil spirits and signified the presence of the gods, who were by definition fragrant beings. Incense was itself an offering: instructions for its composition were set down in the Hebrew Bible. It also formed part of the preparatory stage of Roman animal sacrifice. The early Christian church abjured incense, but it was used again by the 5th century. Burnt in thuribles it was wafted to cense the priests, scriptures, altars and the elements of the Eucharist.

At the height of the frankincense trade, Yemen and Oman were renowned for their perfumed air. Boswellia was harvested and burnt there, and it became a major trading region for spices and perfumes from the neighbouring African coast, and from India once the pattern of the monsoon winds was appreciated.

Today the tree grows in a limited ecological niche in the ‘frankincense region’ of the southern Arabian Peninsula. Trees lodged in clefts in the limestone escarpment, inland from the coast, enjoy the best water supply in this otherwise arid region. Their multiple trunks are covered with papery, peeling bark. Slashed, it releases the oily gum-resin, and if the cutting is moderated the tree will recover and remain productive. The best quality resin is allowed to run down the tree as tears. It dries and hardens into highly aromatic whitish pearls or beads. These can be softened and worked into larger quantities or ground to powder for blending. Incense is often made up of frankincense, other aromatic resins and spices.

It seems likely that increasing dryness, intense exploitation at the height of the trade in the 1st and 2nd centuries AD and then a falling price thereafter may have caused a decline in the number of Boswellia sacra trees, and today numbers are declining. The trees of Dhofar in Oman are now part of a UNESCO World Heritage Site: the Land of Frankincense.

Punica granatum

And they made upon the hems of the robe pomegranates of blue, and purple, and scarlet, and twined linen.

Exodus 39:24

Long used medicinally, today the pomegranate has achieved a new popular status as one of the ‘superfoods’, said to be effective against heart disease.

Break open a pomegranate’s leathery rind and inside are the tightly packed compartments of a jewel casket. Each small seed is surrounded by a beautiful, juicy aril, an extra seed coat which in the pomegranate forms the pulpy, enticing flesh. The colour of the flesh, depending on variety, ranges from deep red to the merest hint of translucent pink. Like colour, the pomegranate’s taste also depends on variety. Since its domestication from the wild orchards of Transcaucasia, northeastern Turkey and the southern Caspian region, the balance of sweet and sour has been selected for and perpetuated by taking cuttings from favoured parent trees. These pretty trees, with their shiny deep green leaves and long-lasting, extravagant red flowers, also pleased their cultivators.

Wherever it was grown, the pomegranate entered the psyche as well as the garden. The abundance of seeds in each fruit often symbolized fertility, regeneration and abundance. The Zoroastrians of the central Iranian plateau used pomegranates in initiation and marriage ceremonies. The fruit appears frequently in the Hebrew Bible, often grouped with the olive and vine. There are descriptions of its form embroidered on priestly and regal garments, and decorating Solomon’s Temple. The shape was replicated in oil lamps and embossed on coins. Said to contain 613 seeds, each corresponding to the Torah’s 613 mitzvot (commandments), pomegranates feature in the food celebrations of Rosh Hashanah.

The Phoenicians may well have taken the pomegranate to North Africa and the western Mediterranean. In Greek myth, pomegranates are chiefly associated with Demeter, goddess of agriculture and the harvest, and her daughter Persephone. Hades, who had abducted Persephone, tricked her into eating some pomegranate seeds. Since eating anything in the underworld condemned the consumer to remain there, she was required to stay in the kingdom of the dead for part of the year. Her return to the earth each spring signalled new life of the forest and field. The fertility symbolism also permeated Greek understanding of the female body. The pomegranate’s blood-like, many-chambered interior was likened to the womb. Hippocratic recipes to assist conception and for fever after childbirth included pomegranate juice.

Traditionally a pomegranate tree is said to have arrived in China’s Han court from Kabul with the returning envoy Zhang Qian, around 135 BC, although a document from a tomb sealed in 168 BC also names the plant. It was greatly appreciated for its flowers and commemorated in poetry as the essence of red beauty during the Six Dynasties (AD 220–589) – the flowers’ shape and colour were likened to the skirt of a courtesan’s dancing costume.

The Christian Church assimilated the pomegranate’s association with resurrection, and its red juice symbolized Christ’s shed blood. In religious art the Madonna often holds an infant Jesus clutching the fruit (for instance Madonna of the Pomegranate, by Botticelli, c. 1487). This medieval trope was stitched into a series of famous tapestries, The Hunt of the Unicorn (1495–1505). In the final panel (thought by some to stand alone) the captive unicorn is tethered to a pomegranate tree. This can be read both as Christ on the cross and as a celebration of matrimony, with the pomegranate as the emblem of fertility and the indissolubility of the union. In 1509 when she married Henry VIII of England, Catherine of Aragon chose the pomegranate for her coat of arms. It was to no avail. Henry had their marriage annulled in 1533 for failing to provide the son he wanted.

Maria Sibylla Merian combined plants and the insects that fed upon them to great effect in her Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium (1705). Here the caterpillar of the iridescent blue Morpho menelaus butterfly strips the leaves of the pomegranate. Merian spent two years in Surinam, returning home with specimens and artwork to prepare her book.

Malus domestica

Fruit of Temptation and Eternal Life

But of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, thou shalt not eat of it: for in the day that thou eatest thereof thou shalt surely die.

Genesis 2:17

Harvesting the ripe fruit, one of a series of woodcuts illustrating the annual cycle of maintaining a healthy orchard, in Marco Bussato’s Giardino di agricoltura (1592). Bussato made his living from grafting before writing a successful series of books which attested to the growing interest in agronomy in the early modern period.

It seems fitting that if the apple’s home cannot have been the Garden of Eden, it was at least in the ‘celestial mountains’. Suggested locations for the biblical paradise don’t easily provide the right conditions for sweet apples that can be plucked from the tree and eaten raw. They lack the essential period of sustained cold temperatures that stimulates the dormant buds to break and the blossom to appear when temperatures rise. By contrast, the slopes of the Tian Shan (which means ‘celestial mountains’), in Central Asia, offered the necessary environment. The ancestors of today’s table fruit most likely took root as part of a vast temperate forest that periodically stretched from the Atlantic to Beringia in the later Pliocene (up to 2.6 million years ago).

Today the slopes of the Tian Shan near Almaty (formerly Alma Ata) in Kazakhstan remain clothed in a veritable fruit forest (although it is under threat). Such abundance yields an array of tree forms, fruit sizes, colours, tastes, textures and ripening times in the native wild apple, Malus sieversii. This highly diverse species is the progenitor of our cultivated apple, M. domestica, which inherited the marvellous variation. Early cultivated apples spread from their Kazakh home along the Silk Roads, and the Greeks and Romans took them across Europe. It was in Europe that M. domestica met the local crab apple, M. sylvestris, and exchanged genes. Their hybrid progeny also exchanged genes with the parents, and over a long period of time these crosses (known as introgression) created the potential for our favourite apple varieties.

Once found, a variety can be maintained in only one way. Plant the pips from your favourite crunch and the next generation will be different. The five seeds in any one apple can give rise to five dissimilar plants. It is by grafting scion wood to a rootstock (first used with apples about 4,000 years ago) that the chance finds of Britain’s perfect ‘cooker’ the ‘Bramley’s Seedling’ (c. 1810s) or America’s ‘Newtown Pippin’ (c. 1750s), ‘Aport’ or ‘Alexander’ from the Ukraine (c. 1700s), ‘Gravenstein’ (c. 1600s), which arose in Germany or Italy but became very popular around Hamburg in the 19th century, or Australia’s world-beater, the ‘Granny Smith’ (c. 1860s) have been perpetuated.

A selection of apple varieties from Jean Herman Knoop, Pomologie, ou Description des meilleures sortes de pommes et de poires (1771). Note the natural imperfections on the fruit, often ignored in idealized portrayals.

The doubt ecology has cast on the apple in Eden has been added to by philology. During the early years of the Christian Church in northern Europe an unwonted precision was attached to the more general Hebraic ‘fruit’ of Genesis 3:3. Similarly the Greek melon (or malon) could refer to any tree fruit: ‘Armenian melons’ were apricots, ‘Persian melons’, peaches, and ‘Median melons’, citrons. This offered multiple options for biblical scholars translating from the Greek and for those chasing the identity of the golden apples of the Garden of Hesperides, the securing of which formed the eleventh of Heracles’ twelve labours. Hippomenes used three given him by Aphrodite to win a foot race against Atalanta, and thus secure her as his bride, when he dropped them and she stooped to pick them up. And if Paris had not been asked to judge which of three goddesses would receive the golden apple inscribed ‘To the Fairest’, the walls of Troy might have stood far longer.

Belief in the apple’s sexual connotations, aphrodisiacal powers and place in courtship were widespread, and applied both to the larger, sweet ones and the small, sharp crab apples. Pre-Roman Celtic traditions venerated the latter. They made good cider and increased in palatability when dried or cooked. Devotees still make deliciously red crab apple jellies, the colour coming from tannins in the skin. As an ornamental tree, it is also increasingly appreciated.

Adam and Eve became mortal when they ate the apple, but Celtic and Norse myths imbued the fruit with powers of limitless longevity. The fabled King Arthur rests still in Avalon, where the apples of immortality grew. Scandinavia’s magical elect lived by eating enchanted apples. When Idun, goddess of spring and keeper of the apples in the paradise of Asgard, is tricked into taking the fruits to their enemies the giants, the gods begin to shrivel and age. After various adventures she returns to her rightful place and restores youth and vigour to the gods with slices of apple.

The Romans were great planters of orchards. After the collapse of their empire, the custom was continued by the monastic orders in piecemeal fashion, although in Iberia it was the Muslims who restored pomological prosperity. Apples were grown for both the table and the cider press. Cider was an important drink throughout the apple-growing regions of Europe. And it was what many of Johnny Appleseed’s trees were planted for in early 19th-century America. Part of a farm-labourer’s wages were commonly paid in cider, a tradition that continued in Britain until 1878, when it was made illegal.

Dessert apples perhaps reached their apogee in Victorian Britain. Apples had had to compete with new delicacies after the voyages of exploration, but a combination of rising numbers of the newly moneyed building grand houses with walled kitchen gardens and the excellence of the British climate for raising apples fuelled a cult of the apple. The range of varieties and their extended ripening period reached new heights. The fruit was not just to be eaten, but also to be admired, the apple store duly opened for friends to exclaim over the contents.

Blossom and fruit of Pyrus malus (Malus domestica). Tian Shan, the home of the apple, was unscathed by the ice that scraped away much of the flora of northern Europe and North America, while considerable geological activity revitalized the soil and created new land. The region was also isolated by large desiccated areas surrounding its mountain ranges. All proved beneficial to the evolution of the apple.

However, many were low yielding, biannual croppers, or liable to scabs, rots and insect pests. Elsewhere in the world, particularly in the USA, the tale of the 20th century was the rise of the large commercial orchard, industrialized picking, packing and sorting, and sale through the demanding supermarket chain. The number of varieties was radically pruned and new kinds were often bred for transportability over taste.

Today the value of forgotten varieties is being appreciated again, for what they offer to our palate and for the richness of their genetic makeup. Great wealth is to be found in the ‘celestial mountains’. Our love affair with the apple is not over.

Chinese Plum or Japanese Apricot

Prunus mume

The flowering plum is the earliest to blossom,

She alone has the gift of recognizing spring.

Xiao Gang, 6th century AD

Flowers and fruit of ‘Toko mume’, a variety of Prunus mume, one of several that feature in The Useful Plants of Japan (1895). Japanese ume condiments include whole umeboshi pickles, a pureed ume paste or ume-su and the ‘vinegar’ left over from pickling.

China’s mei trees have been cherished for thousands of years. Known as Chinese plum or Japanese apricot, this small tree is in fact closer to apricots than plums, their cousins among the Prunus. Native to the slopes of western Sichuan and western Yunnan in China, across the north of Vietnam and Laos, through Korea and Japan, its fragrant blossoms (mei hua), in whites, pinks, reds and pale greens, open on naked stems while snow still lies on the ground. Their appearance heralds the coming of spring. Together with the bamboo and pine, mei became known in China as the ‘three friends in winter’.

Despite their beauty, mei were first cultivated for their yellow- or greenish-fleshed apricot-like fruits. Too sour to eat raw, they have been dried, salted, pickled, pureed and used to flavour wine. The contents of the Western Han dynasty tomb 1 at Mawangdui, Changsha (2nd century BC) included pots containing mei stones and dried fruit, as well as written evidence of processing techniques. Piquant pickles have been favourites in the East for millennia. Today’s Chinese mei and Japanese ume condiments are widely eaten in East Asia and diasporas beyond. Belief in the fruit’s medicinal qualities also has a long history, including as a wound salve and to give strength in battle. In combination with red perilla leaves (used as a colourant), pickled umeboshi’s inherent chemicals – benzaldehyde and organic acids – have been shown to exhibit bactericidal action against Escherichia coli, particularly useful when consuming raw fish dishes.

The early orchards of the Han dynasty (206 BC–AD 200) were laid out for fruit production, but strikingly flowered cultivars attracted increasing attention. Poets of the 5th and 6th centuries began to extol their beauty and the five-petalled blossoms had great significance, being associated with the traditional five blessings of longevity, prosperity, health, virtue and a natural death. Writers celebrated the delicate yet robust nature of flowers that could survive the cold weather during Chinese New Year. Choice mei trees became highly desired in both imperial and private gardens. Their shapes were manipulated to produce preferred forms and vistas created with viewing pavilions. In time these would be replicated in miniature in the traditions of penjing in China and bonsai in Japan.

Watercolour of Prunus mume. Nanjing in China is home to the Purple Mountain Park where thousands of plum blossom trees scent the air. In Japan, festivals in February and March – ume matsuri – still celebrate these harbingers of spring in parks and shrine and temple grounds.

Branches in bloom were cut for indoor arrangements, although the flowers did not last long. Floral transience was juxtaposed with the tree’s longevity. The blossoms, symbolizing rejuvenation and vigour, were borne on old wood, exemplifying steadfastness and durability. Artists depicted isolated, floating branches in exquisite detail. ‘Ink plum blossom’ (mo-mei) became a recognized genre.

During the Song (960–1279) and Yuan (1271–1368) dynasties planting of the trees, and artistic and poetic appreciation of the blossom, reached new heights and acquired new meanings. Song Po-jen’s mid-13th century Mei-hua hsi-shen p’u (Register of Plum-blossom Portraits) contained 100 full-page woodcuts, each with an accompanying poem. It can be read as both a painting manual and a voice of protest against the Yuan Mongol rulers. The legacy of such artists – myriad decorative patterns and discontent expressed through art – continues to inspire, just as the blossoms themselves do each year, as winter hints of spring.

Rosa spp.

The red rose is part of the splendour of God; everyone who wants to look into God’s splendour should look at the rose.

Ruzbihan Baqli of Shiraz, d. 1209

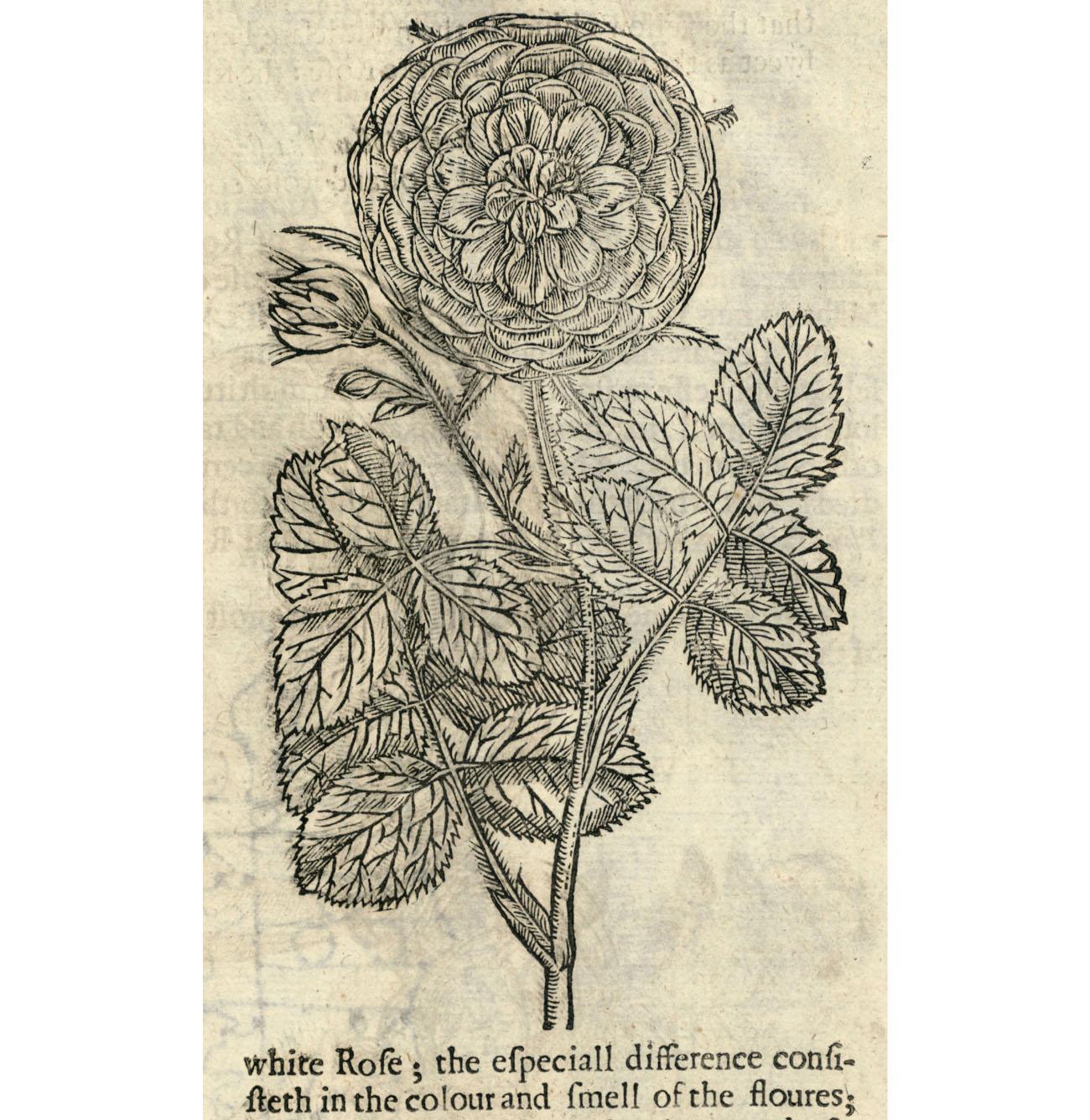

‘Rosa Provincialis, sive Damascena. The Province or Damaske Rose’ from Gerard’s Herball (1633). Gerard declared the rose as deserving the ‘chief and prime place among all floures [sic] whatsoever’.

The rose is perhaps the most loved flower and one with many associations. One hundred million roses changed hands in the week leading up to Valentine’s Day (14 February) 2013 at the world’s largest flower auction, FloraHolland. The flower has enjoyed periods of intense adoration, but never fallen from grace and Rosa continues to enthral in its many forms. From miniatures to sprawling groundcover, through bush and shrub to climber and rambler; five-petalled, many-petalled; whites, pinks, purples, reds, yellows, oranges, stripes, once and repeat flowering; single stemmed and clustered blooms; evergreens and scented leaves; heavenly perfumes – the panorama of cultivated roses is a floral celebration like few others. It attests to a passion to enjoy and manipulate this flower over many centuries, aided by the almost uniquely complex way in which Rosa’s sets of seven chromosomes separate and recombine.

The rose’s symbolic meanings have moved with the times, mutating as fashions and religions change, perhaps reflecting the fact that in many of the important areas of ancient civilization there were local roses to cherish. Rosa is naturally confined to the northern hemisphere, but essentially encircled the globe between 20 and 70 degrees north. The genus appears to have thrived during the Oligocene (33.9–23 million years ago), dispersing and diversifying into the approximately 100 to 150 species (rose taxonomy is complex) of wild roses gracing the planet today.

‘Rosa bifera officinalis/Rosier des Parfumeurs’, from P.-J. Redouté’s Les Roses, vol. 1 (1817). Redouté’s brilliant execution and composition captured almost everything about the rose, except its scent. The largest constituent of rose oil is citronellol, but it is other trace components that contribute most to its wonderful perfume.

From these wild species the rose was probably domesticated many times. The plant’s innate ability to hybridize with close and far-flung relations when brought into contact by human hands furnished the staggering number of garden cultivars – around 20,000. Many older roses resulted from complex crosses, the precise when and how remaining a mystery. The white and blush Albas are an old European hybrid between R. gallica and R. canina. R. damascena has three parents, each with a discrete natural range. At some point the species rose R. gallica and the long-cultivated R. moschata produced a new hybrid. When this was crossed with R. fedtschenkoana the glorious scented damascene or damask rose was born. There is no ambiguity about its desirability: the damask is a perfume rose. Distillation of its petals yields attar of roses and its by-product, rose water. Rose water is used routinely in sweet and savoury dishes of the Persian kitchen and aromatic confections throughout Southwest Asia. The Zoroastrians still greet guests with rose sweets.

Left A watercolour probably painted in the early 19th century by one of the many Indian artists who produced botanical illustrations for the East India companies, combining traditional styles with the demands of European natural history illustration to produce images that were at once familiar and exotic.

Right Herbarium specimen from the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew of a variety of Rosa indica now known as Rosa chinensis Jacq. var. minima, presented by Joseph Dalton Hooker in 1868.

The Greeks wrote sparingly of roses as emblems of death and love. The Romans continued these associations, but as with many things Roman, took them to new levels of excess. Roses featured in medicine and elite dining, and substantial cultivation such as in Roman Egypt and Campania produced the raw material for decorative garlands and chaplets. Demand was particularly high during the celebration of Rosalia, generally towards the end of May, when roses were placed on tombs in commemoration of the dead.

Initially shunned by the Christian Church, roses made a comeback in the Middle Ages, decorating churches and finding their way into spiritual writing. St Bernard of Clairvaux (1090–1153) in his exegesis of the Song of Songs lauded white roses as a Marian symbol, while the red rose’s five petals frequently represented Christ’s Five Wounds. The rose and cross were also combined in the Rosicrucians’ secret society, which flourished in the swirling hermeneutics of 17th-century Protestantism.

Roses were a quintessential part of the Persian garden. In Islamic tradition it is said that as Muhammad ascended to receive his revelations, his sweat fell back to earth and a fragrant rose came forth. In the 13th century Sufi mystics such as Ruzbihan Baqli and Rumi celebrated the rose’s transcendental qualities; not least the lingering ethereal perfume captured after the flower has faded.

By forcing or growing different kinds of roses it was possible to extend the rose season, but only the damask roses flowered twice in a year. In the late 18th century people in the West began to appreciate what the Chinese, with their vastly superior history of cultivation and different rose genes, had enjoyed for at least 1,000 years: remontant or repeat-flowering roses. The Chinese species bloomed all summer long in new shades of pink, crimson, blush and yellow, some with a delicate scent of fresh tea (from which came the hybrid teas). Four cultivars in particular survived the English climate (England having come to dominate the China trade) and served as ‘studs’, bringing their precious genes to fanciers in Europe and North America. Chinese roses started a breeding mania. Today’s plants of enchanting beauty, scent and reliability are the results of the increasingly complex hybridizations (and some lucky sports). They delight enthusiasts in clubs and societies the world over.

Empress Josephine, wife of Napoleon, is often credited with playing a leading role in promoting the rose and establishing the concept of a dedicated rose garden at her chateau at Malmaison. Romantic yes, but not strictly accurate. While Josephine was certainly interested in roses she sprinkled them in glorious mixed borders; the ‘rose garden’ was invented when Malmaison opened to the public at the turn of the 20th century.

Roses can have a darker side too. Writing of the short reign (218–22) of the Roman emperor Elagabalus (Heliogabalus), Lampridius has him walking through rooms strewn with roses and suffocating his guests with masses of fragrant petals. The ‘violets and other flowers’ were turned into rose petals in Alma-Tadema’s late 19th-century masterpiece The Roses of Heliogabalus. Today such implausible antics would probably require a shipment from Colombia, Ecuador or Kenya. They have captured the world market in these flowers, which have for so long captured our hearts.

Tulipa spp.

All these fools want is tulip bulbs/Heads and hearts have but one wish

Let’s try and eat them; it will make us laugh/To Taste how bitter is that dish.

Petrus Hondius, 1621

A diminutive Tulipa armena (just over 20 cm/8 in. tall) from the Kew Herbarium. Small species tulips such as this were collected from the wild and manipulated (with the help of ‘breaking viruses’, which led to the stripes) into the fancy forms of the 17th-century tulip mania.

Tulip bulbs are humble looking things, easily held in the hand, a thin dry papery layer protecting the softer tissues within. But great potential lies deep inside. For here, in the centre of the scales that will provide its nourishment, is a new stem. At its tip is the embryonic flower bud. Once planted, and after the roots have formed and an essential period of coolness has passed, the stem will propel the growing flower bud upwards before its petals colour and open for a glorious two weeks or so of unbridled beauty.

In its quiescent state the tulip can easily be transported, ensuring instant gratification somewhere else the following spring. It was this that helped the Ottoman Turks transform various species of tulips from wild flowers to essential jewels of the garden. After his conquest of Constantinople (Istanbul) in 1453, Mehmed II built the Topkapı palace and laid out its Persian-inspired gardens, replete with carnations, roses, hyacinths, irises, jonquils and tulips. Under his successors, the tulip became intimately involved with Ottoman culture from the 16th century, evident in textiles, pottery and most famously its ornate glazed tiles.

Turkey may have been the place where the wild tulip entered the garden in grand style, but only four species of tulips are thought to be native here, although more now grow wild in mountainous areas of the country. The likely natural home of the tulip is further east, between the mountains of Tian Shan and Pamir-Alai in Central Asia. From here it spread where mountain and steppe provided the right combination of free drainage, winter chill, spring rain and a good baking in summer sun. The Ottoman sultans and their equally rapacious viziers were able to demand huge quantities of bulbs to be dug up from the wild in the empire’s provinces and vassal states, while their florists began to manipulate nature. They selected and crossed the seeds of those tulips that grew ever closer to their ideals of perfection: long, slender flowers consisting of six same-length dagger-shaped petals, held upright on an elegant but strong stem.

For Europeans it wasn’t quite love at first sight. The first tulip bulbs to arrive in Antwerp in 1562 suffered an inauspicious fate. Very much an adjunct to the bales of cloth he received, a merchant tried them roasted with oil and vinegar like onions and tossed the rest into his garden. Most languished, but a few were treated with respect by George Rye, another merchant and keen gardener. Similar cargoes brought bulbs to Amsterdam. Some of Leiden’s came when the new head of the botanic garden, Carolus Clusius, arrived in 1593. He hoarded his blooms, refusing to share or sell, and fell victim to theft. Dutch tulipomania is the most famous, but France and England experienced periods of intense frenzy, and countries such as Germany were influential markets.

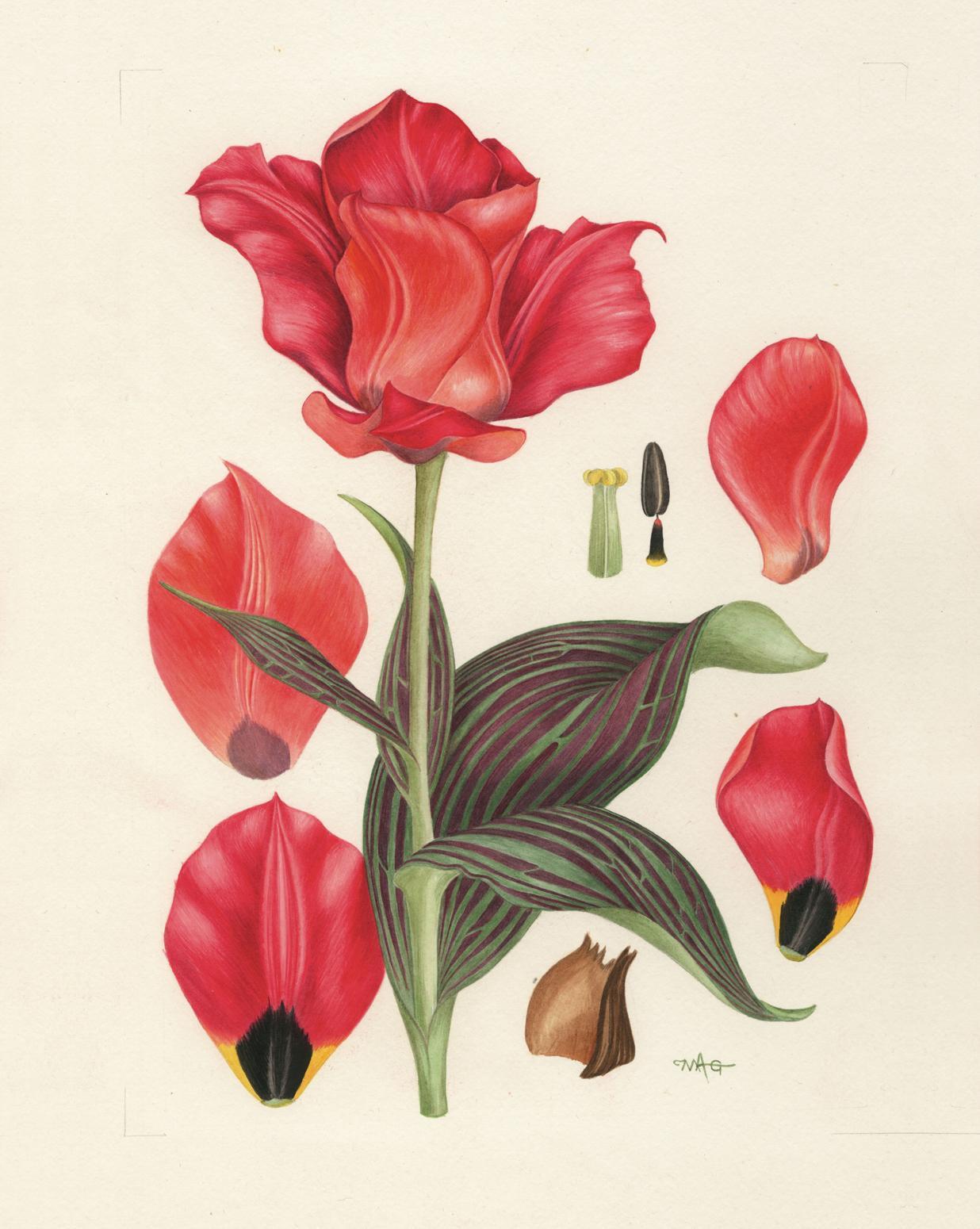

A painting of Tulipa greigii by Mary Grierson (1912–2012), part of a series of tulips by one of the leading botanical artists of the later 20th century. Grierson worked as the herbarium artist at Kew, combining artistic skills with attention to detail and a fine understanding of botany.

Tulip-fancying was part of the wider interest in exotic plants brought back through journeys of trade and exploration, itself part of the passion for owning and displaying natural curiosities. Plants, and especially tulips as tulipomania took hold, were to be grown in precisely arranged beds of exact dimensions, which visitors were invited to witness and admire as the flowers reached their peak.

And what a peak it was. European taste in tulips favoured a plumper look to the flower; the flower heads were often large, on long stems. But what drove tulip madness was the colour. Not the pure, solid colours familiar in today’s mass plantings and flower-shop blooms, but the delicate feathering and flaming of tulips that by some occult process had become multicoloured. This was termed ‘breaking’ – one colour apparently breaking into another on the petals as if painted with the finest brush. There were three desired types. Bizarres were red streaked on yellow, Roses red on white and Bybloemens purple on white.

A plate from Robert Thornton’s Temple of Flora, or Garden of Nature (1799–1807). Thornton employed leading artists and engravers, and oversaw the production of the illustrations. He had the plants set against naturalistic backgrounds and the effect was stunning, but the project bankrupted him and he died in poverty.

Such astonishing beauty is now known to be caused by viruses, which interfere with the genes that code for proteins producing particular pigments in the petals. The virus also weakens the plant and slows the formation of bulblets. These baby bulbs were grown on, bulking up the stock (seeds do not come true). Over time what is essentially a diseased individual plant dies out, but its progeny continue. There is also the potential for new favourites as parasitic virus and tulip host co-existed in the florists’ beds. So, ironically, it was damaged goods that were traded with such passion initially by aficionados and then in the 1620s by the emergent professional nurserymen. Such businesses profited as the price of bulbs (sold by weight after lifting) rose and they continued to prosper as entrepreneurial burgomasters entered the market as middlemen trading in tulip futures. This was the bubble that burst in late 1636 and early 1637.

The Dutch organized successful packaging for long-distance transport and used travelling salesman to create markets for their wares. Such enterprise would see them become the world’s leading growers of bulbs and flowers, moving into the massive American market with new breeds of pure coloured flowers in the 20th century. Today the Dutch grow 4.32 billion tulips, 2.3 billion of which fill flower stalls and bouquets as cut flowers. They are now as virus-free as possible and those flamboyant blooms of the past live on only among a few cognoscenti growers and in the still-coveted still life paintings of the old masters.

Orchidaceae

An orchid in a deep forest sends out its fragrance even if no one is around to appreciate it. Likewise, men of noble character hold firm to their high principles, undeterred by poverty.

Confucius, 551–479 BC

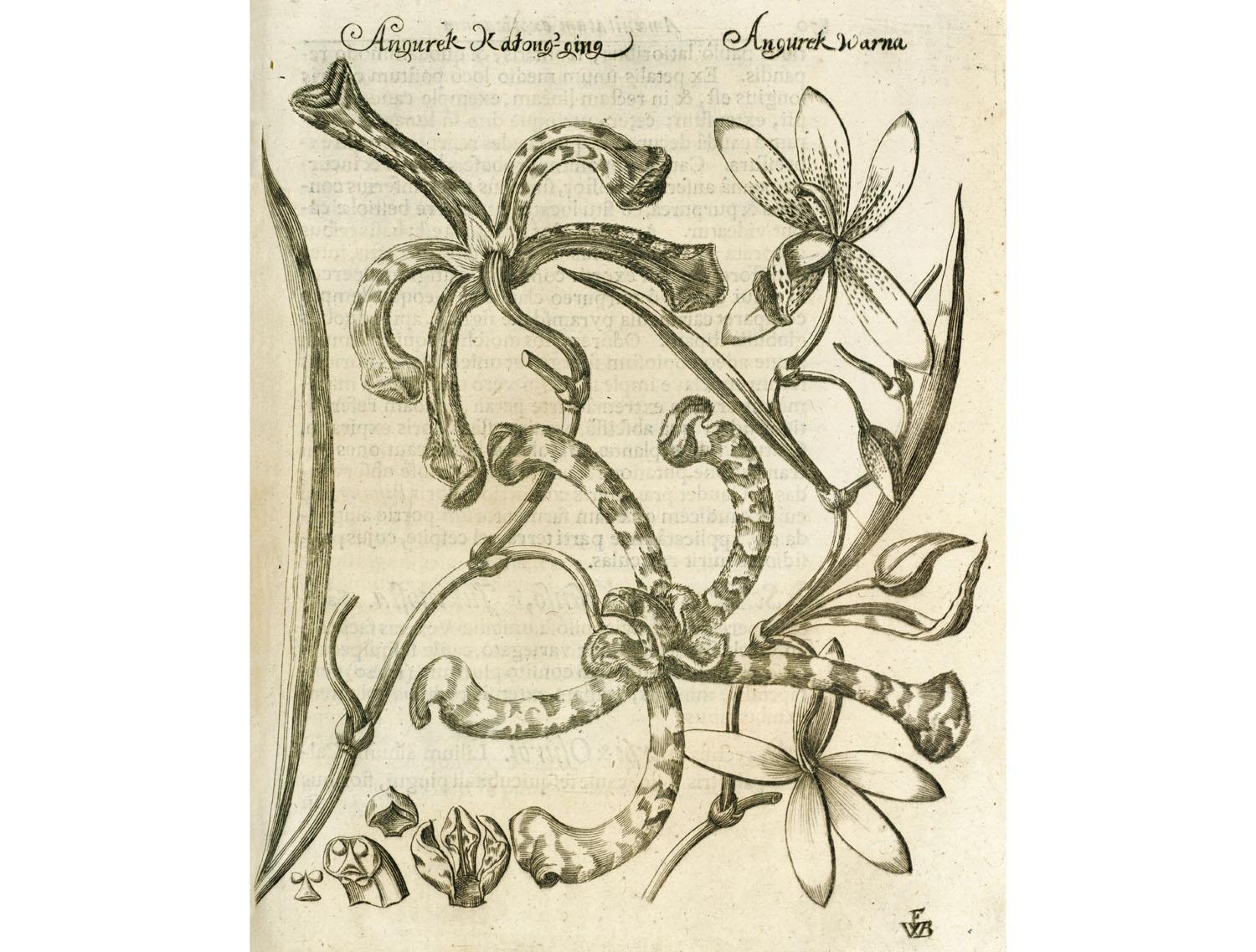

The ‘Angurek katong’ging,’ first described by Engelbert Kaempfer in Amoenitatum Exoticarum (1712), combining the Malay words for epiphytic orchid and scorpion; it is now known as Arachnis flosaeris. Arachnis species were important in commercial breeding of hybrid orchids for the houseplant market.

Orchids have it all: they are exquisite, fragrant, alluring, and come in a seemingly unending diversity of extraordinary floral forms that enchant and engage the mind. If orchids are eternally beautiful, today they are also big business. Women may not wear orchid corsages as they once did and orchids must vie with roses and lilies in bridal bouquets, but step into a supermarket and there are potted orchids by the shelf-full. Many are Phalaenopsis or ‘moth orchids’ – named for their resemblance to those denizens of the insect world. Choice abounds among these unnamed mass-market hybrids bred from species from South Asia and the Indonesian archipelago and raised using micro-propagation techniques. They may offend the orchid purists, but the whites, pinks, purples and yellows, and spots and stripes of the often scented flowers have a grace and elegance that bring an aura of the exotic, a sense of the humid tropics to the windowsill. Today’s multi-billion dollar business is but the latest growth of an ancient fascination. Wherever they occur – over huge swathes of the planet with the exception of the frozen Antarctic – orchids have been held in high esteem.

Confucius associated orchids with purity and morality and they later became a favourite theme for the literati who retired from public life rather than serve the conquering Mongols of the Yuan dynasty. In poetry and especially in ink drawings, orchids symbolized high-mindedness in adversity. Orchid painting would develop into a leading art form in China, Japan and Korea. The plants were also employed in the Chinese pharmacopeia. Various species of Dendrobium were renowned for their strengthening powers, properties that reflected this orchid’s challenging habitat. Named Shih-hu or ‘rock-living’, it was thought that plants that could thrive when clinging to exposed rock must be resilient and robust and would therefore impart these qualities. Together with other Chinese orchids they do contain active substances which are currently being investigated.

The Cymbidium hookerianum orchid, found in Bhutan in 1848 and named by Heinrich Gustave Reichenbach for Joseph Dalton Hooker. Reichenbach was one of the leading orchidists of the 19th century. The artist and engraver Walter Hood Fitch was a master at fitting large, complex plants into paper sizes needed for publication.

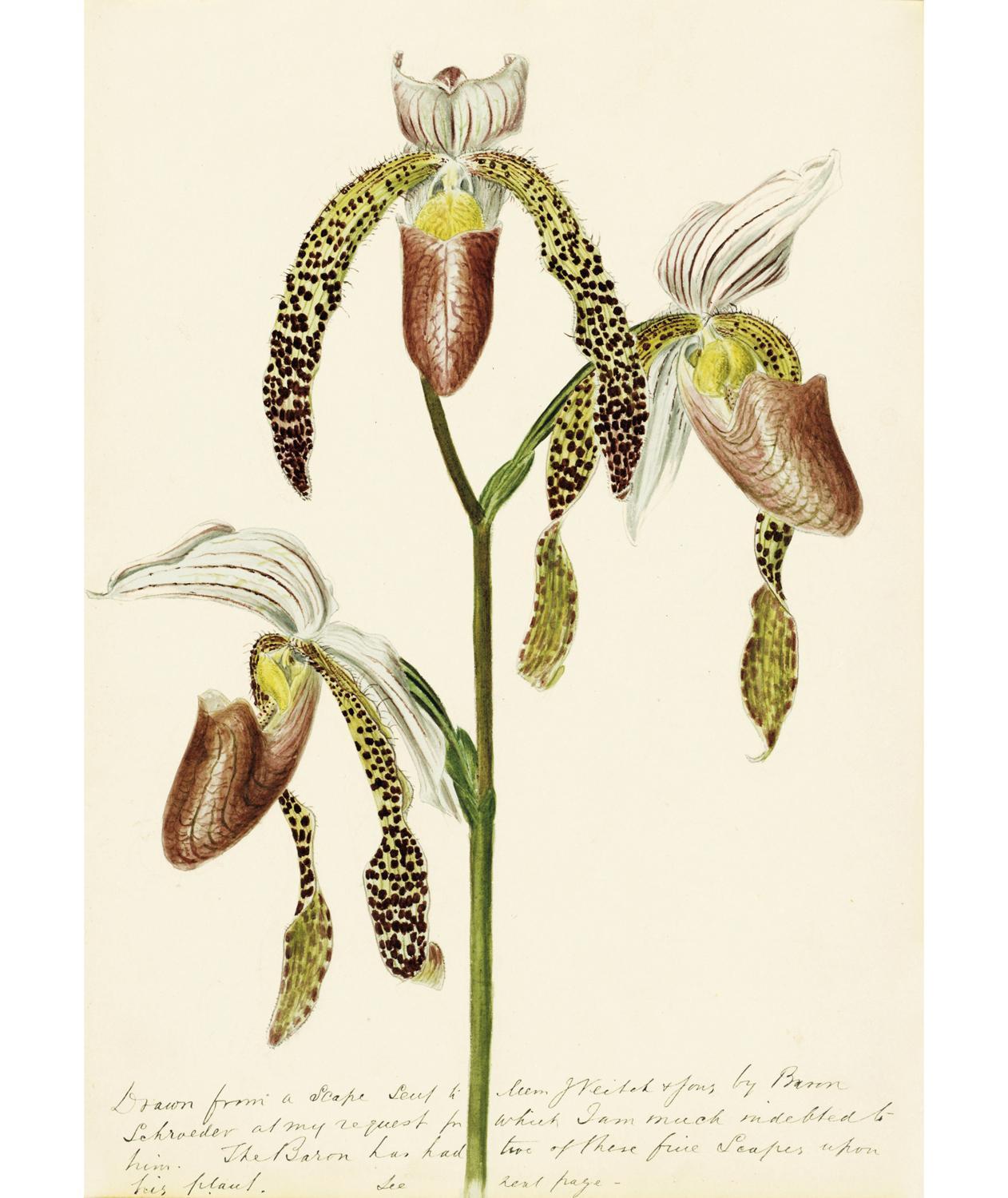

The hybrid orchid Cypripedium morganiae (Paphiopedilum morganiae) from the Scrapbooks of John Day (1824–88), who painted his own orchids, those in London nurseries and the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, and some in situ in the tropics.

A similar association between plant forms and medicinal use was known in ancient Greece and Rome as the ‘doctrine of signatures’. Europe is home to only about 1 per cent of the world’s orchid species, including members of the Orchis (Greek for testicles) and Ophrys genera, with paired, subterranean, swollen rhizomes, thought to resemble male generative organs. In Greek mythology Orchis enjoyed various sexual adventures but these ended badly, and transformed after death he bequeathed the world these sensuous plants. Theophrastus (c. 372–288 BC), Dioscorides (c. AD 40–80) and Galen (AD 129–c. 210) linked assorted orchids with fecundity and suggested their use in fertility disorders. Various species have recently been identified on Roman monuments, appearing as part of the frieze on the Ara Pacis or peace altar built by Augustus and on the Temple to Venus Genetrix dedicated by Julius Caesar. Folk traditions continue to recommend these plants as aphrodisiacs. The Turks have long enjoyed an ice cream made of salep – the dried powdered root of Orchis mascula – and make claims for its positive effects.

Orchis mascula, the early purple orchid, which, like O. morio was used by Darwin in his research. The twinned swollen rhizomes inspiring the genus name are displayed, along with the seed capsules, each of which can contain 4,000 seeds. Destruction of their habitat (old meadows and pastures) means that even this prodigality cannot contend with 21st-century life.

The Orchidaceae family is one of the largest among the flowering plants, with in excess of 26,000 species, most found in the tropics and subtropics. Many are epiphytes – air plants that grow high up in the canopy. In the 17th century, voyages of discovery in search of East Indies spices brought botanizing merchants, missionaries, officers, diplomats and doctors into new territories, with their exotic floras. Georg Eberhard Rumphius, ‘first merchant’ of Batavia (Jakarta), produced a twelve-volume Herbarium Amboinense (published posthumously in the mid-18th century). He included important new species of terrestrial and epiphytic orchids, the latter described as ‘aristocrats of wild plants, who convey their nobility by wanting to live only high up in trees’.

Such books and the arrival of the plants themselves fuelled the new passion for exotics. Sir Joseph Banks brought dendrobium orchids back from Australia. Humbler servants of the expanding British Empire also returned home with specimens although many perished on the long sea voyages. The survivors could be kept alive in hothouses, but the mistaken view that they were parasitic plants led to fatal mistakes in their culture and much disappointment as they faded or failed to flower. William Cattley, an exotic-plant enthusiast, succeeded. The ‘most splendid’ Cattleya labiata from the Organ Mountains of Brazil displayed its true beauty in his hothouse in 1818. Cattleyas would become extremely popular.

Nurseries had initially relied upon informal networks of botanical enthusiasts as suppliers of parent stock, but they began to use professional plant hunters. In the 19th century, nurserymen such as James Veitch gambled on the heavy costs involved and sent out men to brave the rigours of the tropics. As orchid mania intensified in Britain and northern Europe in the second half of the century the effects on the natural habitats could be devastating. Competing collectors stripped orchids by the thousands, taking all they could find in a locality, occasionally by felling the host trees to pick off the plants at ground level. Once they had taken all they could carry they destroyed the rest to prevent others gaining access to them.

To bulk out the collected stocks – many of which were auctioned on arrival – nurseries also experimented with propagation and hybridization. Orchids often failed to set seeds for several years, and when they did, germination was no easy matter. Orchids produce copious dust-like seeds. More air than embryo, they float in the air or perhaps on water. Miniaturization means they lack the food stores that feed larger seeds as they germinate; to compensate, orchids evolved species-specific relationships with mycorrhizal fungi to aid germination and subsequently support the plant in continued symbiosis. Still unaware of this, the persistent and talented plantsman John Dominy, working for Veitch, raised the first flowering hybrid orchid Calanthe × dominyi in 1856. It was named in his honour by the leading orchidist John Lindley, who remarked to its creator: ‘You will drive the botanists mad’.

‘The parts of the fruit of Vanilla planifolia’, the vanilla orchid, with the seeds magnified × 200. The botanist and orchid specialist John Lindley and renowned artist Francis Bauer teamed up to produce Illustrations of Orchidaceous Plants (1830–38), which has been described as a foundation work on orchids.

Charles Darwin retained his sanity but was fascinated with orchids and their means of reproduction. He wanted to understand the amazing array of adaptations that have co-evolved between different species of orchids and their individual insect pollinators. Working first with native British orchids, many then growing around his home at Down House in Kent, he described orchids that imitated female insects, inducing the males to try to mate but instead picking up pollen from one plant and fertilizing the next. He was also well supplied with tropical orchids from his friends and correspondents. The stunning white orchid from Madagascar, Angraecum sesquipedale, with its 25-cm (10-in.) long nectary amazed him. His suggestion of a long-tongued moth as pollinator would prove correct. Identified in 1903, Xanthopan morganii praedicta has a tongue that can indeed reach the nectar and pick up the pollen along the way, but it wasn’t actually caught in the act until 1997.

The special relationship between plants and pollinators played a part in the one orchid that has perhaps universal acclaim. Very few people do not like vanilla, with its complex, aromatic, floral flavour. But what they may not know is that the real thing, so much better than the synthetic substitute usually made from lignin, comes from orchids. The main vanilla orchid is Vanilla planifolia (or fragrans). Cherished by the Totonacs of eastern Mexico, its fermented beans were used to pay tribute to the Aztecs and flavoured the cold chocolate drink reserved for the elite or taken by soldiers before engagements. The Totonacs revered the orchid, believing that the first plant grew from the blood of an ancient princess whose punishment for eloping with her lover was to be beheaded.

Vanilla is still expensive today because outside its homeland (with its natural pollinator) it has to be hand-pollinated, and then handpicked and hand-cured before being hand-sorted and packed. The discovery in 1841 of a simple method of hand-pollination by a young, recently freed slave, Edmond Albius, on Réunion in the Indian Ocean, allowed this island to overtake Mexico as the world’s largest producer in the 1860s. Word of Albius’s method and the vanilla orchid spread, so that today Madagascar and Indonesia – both home to many beautiful indigenous orchids – are the leading producers.

Orchids still fascinate and surprise. In 2011 Bulbophyllum nocturnum, newly discovered on New Britain (Papua New Guinea), was seen opening its flowers at 10 p.m. – the first night-flowering orchid ever observed. Botanist André Schuiteman at Kew predicts that the pollinator will be a tiny fungus gnat since the orchid’s flowers resemble slime moulds. Such is the wonder of the orchid world.

Paeonia spp.

In front of the Emperor’s audience hall many thousand-petalled tree peonies were planted … he would sigh and say ‘Surely there has never before been such a flower among mortals’.

9th-century Chinese writer

‘Pivoine odorante’, from P.-J. Redouté’s Choix des plus belles fleurs (1827–33). Moutan or tree peonies, P. suffruticosa, originated in China, where they had long been avidly cultivated. Held in high esteem by the Tang dynasty emperors, their massive blooms were used to ornament the imperial palaces. They were still relatively new and very sought after when Redouté painted them early in the 19th century.

In some Greek legends, Paeon (or Paean) served as physician to the gods. He cured Hades and Ares of their wounds and as a reward after his death was transformed into a peony. The story could relate to one or more of five species of herbaceous peonies that graced the hillsides of Greece and the Greek islands. Paiawon is mentioned in a list of deities on a Linear B tablet found at Knossos, Crete, so perhaps it was the pure white single-petalled Cretan P. clusii that is referred to. This plant’s roots have high levels of the volatile antimicrobial paeonol. Deep maroon P. parnassica found on Mount Parnassus contains methyl salicylate (similar to aspirin), so external use could have helped aches and sprains.

But neither of these species came to dominate the learned herbals. In the 1st century AD Dioscorides gave various medical applications for peonies and referred to two kinds – male and female. This related not to the plant’s reproductive strategy, which was not then appreciated (and in any case peonies are hermaphrodite), but to their relative robustness. P. mascula (the Balkan peony) has been identified as male and P. officinalis, female. ‘She’ came to dominate the medical market, and found favour as a hardy garden plant. In medieval Europe peonies were part of the floral complement of a ‘noble garden’. Crushed seeds were used as spice and baked roots eaten alongside roast pork, their astringency a perfect foil for fatty meat. Double whites and reds, with their showy, petal-rich flower bowls were bred: the peony aesthetic was well underway.

Herbaceous peonies reach from Spain to Japan, from the Kola Peninsula on the Arctic Circle to Morocco (there are also two further herbaceous species in northwestern America and Mexico). China is fortunate to be home to the eight species of tree peonies too. Mudan or Moutan (often P. suffruticosa) peonies are taller, woody plants that have gained their own mystique and glamour. Their name is said to come from Mudang – the mythical Emperor of Flowers. During the Tang dynasty (618–907) tree peonies became a veritable mania at court and beyond, and inspired poets and artists. Some exchanged hands for a hundred ounces of gold and gardeners achieved blooms of 30 cm (12 in.) in diameter. Also native to China, the herbaceous P. lactiflora was grown en masse as a medicinal.

Watercolour of ‘Paeonia daurica’ – this herbaceous peony ranges from Croatia to Iran, across Turkey and the Caucasus mountains. In the past there was some uncertainty about its relationship to P. mascula, the ‘male’ peony of Dioscorides’ great herbal from the 1st century AD, but recent work has confirmed it as a separate species.

Buddhist monks took the tree peony to Japan in the 8th century. Here gardeners developed the imperial peonies and later the anemone-flowered forms, manipulating the stamens (male flower parts) until they resembled narrow petals and appeared to fill the petal bowl. They gave the resulting plants elaborate names.

After their introduction by Sir Joseph Banks at the end of the 18th century, tree peonies became a sensation in Europe’s elite gardens – a scented, thorn-free ‘rose’. And when P. officinalis met P. lactiflora their offspring were considered great beauties. Plant hunters sought out new species in the East for introduction and breeding; this was not straightforward since China’s borders were difficult to penetrate, but persistence paid off. So too did that of Japan’s Toichi Itoh, who finally achieved his determined desire for a double yellow by overcoming the previously unfruitful crossing of tree and herbaceous parents. Sadly, he died before his plants came into their floral glory in 1963 and showed the way to yet more new forms and colours in this glorious flower.