In 1950, a curious notice turned up in the New Yorker’s gossipy “Talk of the Town” section:*

New atoms are turning up with spectacular, if not downright alarming frequency nowadays, and the University of California at Berkeley, whose scientists have discovered elements 97 and 98, has christened them berkelium and californium respectively…. These names strike us as indicating a surprising lack of public-relations foresight…. California’s busy scientists will undoubtedly come up with another atom or two one of these days, and the university… has lost forever the chance of immortalizing itself in the atomic tables with some such sequence as universitium (97), ofium (98), californium (99), berkelium (100).

Not to be outwitted, scientists at Berkeley, led by Glenn Seaborg and Albert Ghiorso, replied that their nomenclature was actually preemptive genius, designed to sidestep “the appalling possibility that after naming 97 and 98 ‘universitium’ and ‘ofium,’ some New Yorker might follow with the discovery of 99 and 100 and apply the names ‘newium’ and ‘yorkium.’ ”

The New Yorker staff answered, “We are already at work in our office laboratories on ‘newium’ and ‘yorkium.’ So far we just have the names.”

The letters were fun repartee at a fun time to be a Berkeley scientist. Those scientists were creating the first new elements in our solar system since the supernova kicked everything off billions of years before. Heck, they were outdoing the supernova, making even more elements than the natural ninety-two. No one, least of all them, could foresee how bitter the creation and even the naming of elements would soon become—a new theater for the cold war.

Glenn Seaborg reportedly had the longest Who’s Who entry ever. Distinguished provost at Berkeley. Nobel Prize–winning chemist. Cofounder of the Pac-10 sports league. Adviser to Presidents Kennedy, Johnson, Nixon, Carter, Reagan, and Bush (George H. W.) on atomic energy and the nuclear arms race. Team leader on the Manhattan Project. Etc., etc. But his first major scientific discovery, which propelled him to those other honors, was the result of dumb luck.

In 1940, Seaborg’s colleague and friend, Edwin McMillan, captured a long-standing prize by creating the first transuranic element, which he named neptunium, after the planet beyond uranium’s Uranus. Hungry to do more, McMillan further realized that element ninety-three was pretty wobbly and might decay into element ninety-four by spitting off another electron. He searched for evidence of the next element in earnest and kept young Seaborg—a gaunt, twenty-eight-year-old Michigan native who grew up in a Swedish-speaking immigrant colony—apprised of his progress, even discussing techniques while they showered at the gym.

But more was afoot in 1940 than new elements. Once the U.S. government decided to contribute, even clandestinely, to the resistance against the Axis powers in World War II, it began whisking away scientific stars, including McMillan, to work on military projects such as radar. Not prominent enough to be cherry-picked, Seaborg found himself alone in Berkeley with McMillan’s equipment and full knowledge of how McMillan had planned to proceed. Hurriedly, fearing it might be their one shot at fame, Seaborg and a colleague amassed a microscopic sample of element ninety-three. After letting the neptunium seep, they sifted through the radioactive sample by dissolving away the excess neptunium, until only a small bit of chemical remained. They proved that the remaining atoms had to be element ninety-four by ripping electron after electron off with a powerful chemical until the atoms held a higher electric charge (+7) than any element ever known. From its very first moments, element ninety-four seemed special. Continuing the march to the edge of the solar system—and under the belief that this was the last possible element that could be synthesized—the scientists named it plutonium.

Suddenly a star himself, Seaborg in 1942 received a summons to go to Chicago and work for a branch of the Manhattan Project. He brought students with him, plus a technician, a sort of super-lackey, named Al Ghiorso. Ghiorso was Seaborg’s opposite temperamentally. In pictures, Seaborg invariably appears in a suit, even in the lab, while Ghiorso looks uneasy dressed up, more comfortable in a cardigan and a shirt with the top button undone. Ghiorso wore thick, black-framed glasses and had heavily pomaded hair, and his nose and chin were pointed, a bit like Nixon’s. Also unlike Seaborg, Ghiorso chafed at the establishment. (He would have hated the Nixon comparison.) A little childishly, he never earned more than a bachelor’s degree, not wanting to subject himself to more schooling. Still, prideful, he followed Seaborg to Chicago to escape a monotonous job wiring radioactivity detectors at Berkeley. When he arrived, Seaborg immediately put him to work—wiring detectors.

Nevertheless, the two hit it off. When they returned to Berkeley after the war (both adored the university), they began to produce heavy elements, as the New Yorker had it, “with spectacular, if not downright alarming frequency.” Other writers have compared chemists who discovered new elements in the 1800s to big-game hunters, thrilling the chemistry-loving masses with every exotic species they bagged. If that flattering description is true, then the stoutest hunters with the biggest elephant guns, the Ernest Hemingway and Theodore Roosevelt of the periodic table, were Ghiorso and Seaborg—who discovered more elements than anyone in history and extended the periodic table by almost one-sixth.

The collaboration started in 1946, when Seaborg, Ghiorso, and others began bombarding delicate plutonium with radioactive particles. This time, instead of using neutron ammunition, they used alpha particles, clusters of two protons and two neutrons. As charged particles, which can be pulled along by dangling a mechanical “rabbit” of the opposite charge in front of their noses, alphas are easier to accelerate to high speeds than mulish neutrons. Plus, when alphas stuck the plutonium, the Berkeley team got two new elements at a stroke, since element ninety-six (plutonium’s protons plus two more) decayed into element ninety-five by ejecting a proton.

As discoverers of ninety-five and ninety-six, the Seaborg-Ghiorso team earned the right to name them (an informal tradition soon thrown into angry confusion). They selected americium (pronounced “am-er-EE-see-um”), after America, and curium, after Marie Curie. Departing from his usual stiffness, Seaborg announced the elements not in a scientific journal but on a children’s radio show, Quiz Kids. A precocious tyke asked Mr. Seaborg if (ha, ha) he’d discovered any new elements lately. Seaborg answered that he had, actually, and encouraged kids listening at home to tell their teachers to throw out the old periodic table. “Judging from the mail I later received from schoolchildren,” Seaborg recalled in his autobiography, “their teachers were rather skeptical.”

Continuing the alpha-bombing experiments, the Berkeley team discovered berkelium and californium in 1949, as described earlier. Proud of the names, and hoping for a little recognition, they called the Berkeley mayor’s office in celebration. The staffers in the mayor’s office listened and yawned—neither the mayor nor his staff saw what the big deal about the periodic table was. The city’s obtuseness got Ghiorso upset. Before the mayor’s snub, he had been advocating for calling element ninety-seven berkelium and making its chemical symbol Bm, because the element had been such a “stinker” to discover. Afterward, he might have been tickled to think that every scatological teenager in the country would see Berkeley represented on the periodic table as “Bm” in school and laugh. (Unfortunately, he was overruled, and the symbol for berkelium became Bk.)

Undeterred by the mayor’s cold reception, UC Berkeley kept inking in new boxes on the periodic table, keeping school-chart manufacturers, who had to replace obsolete tables, happy. The team discovered elements ninety-nine and one hundred, einsteinium and fermium, in radioactive coral after a hydrogen bomb test in the Pacific in 1952. But their experimental apex was the creation of element 101.

Because elements grow fragile as they swell with protons, scientists had difficulty creating samples large enough to spray with alpha particles. Getting enough einsteinium (element ninety-nine) to even think about leapfrogging to element 101 required bombarding plutonium for three years. And that was just step one in a veritable Rube Goldberg machine. For each attempt to create 101, the scientists dabbed invisibly tiny bits of einsteinium onto gold foil and pelted it with alpha particles. The irradiated gold trellis then had to be dissolved away, since its radioactivity would interfere with detecting the new element. In previous experiments to find new elements, scientists had poured the sample into test tubes at this point to see what reacted with it, looking for chemical analogues to elements on the periodic table. But with element 101, there weren’t enough atoms for that. Therefore, the team had to identify it “posthumously,” by looking at what was left over after each atom disintegrated—like piecing a car together from scraps after a bombing.

Such forensic work was doable—except the alpha particle step could be done only in one lab, and the detection could be done only in another, miles away. So for each trial run, while the gold foil was dissolving, Ghiorso waited outside in his Volkswagen, motor running, to courier the sample to the other building. The team did this in the middle of the night, because the sample, if stuck in a traffic jam, might go radioactive in Ghiorso’s lap and waste the whole effort. When Ghiorso arrived at the second lab, he dashed up the stairs, and the sample underwent another quick purification before being placed into the latest generation of detectors wired by Ghiorso—detectors he was now proud of, since they were the key apparatus in the most sophisticated heavy-element lab in the world.

The team got the drill down, and one February night in 1955, their work paid off. In anticipation, Ghiorso had wired his radiation detector to the building’s fire alarm, and when it finally detected an exploding atom of element 101, the bell shrieked. This happened sixteen more times that night, and with each ring, the assembled team cheered. At dawn, everyone went home drunkenly tired and happy. Ghiorso forgot to unwire his detector, however, which caused some panic among the building’s occupants the next morning when a laggard atom of element 101 tripped the alarm one last time.*

Having already honored their home city, state, and country, the Berkeley team suggested mendelevium, after Dmitri Mendeleev, for element 101. Scientifically, this was a no-brainer. Diplomatically, it was daring to honor a Russian scientist during the cold war, and it was not a popular choice (at least domestically; Premier Khrushchev reportedly loved it). But Seaborg, Ghiorso, and others wanted to demonstrate that science rose above petty politics, and at the time, why not? They could afford to be magnanimous. Seaborg would soon depart for Camelot and Kennedy, and under Al Ghiorso’s direction, the Berkeley lab chugged along. It practically lapped all other nuclear labs in the world, which were relegated to checking Berkeley’s arithmetic. The single time another group, from Sweden, claimed to beat Berkeley to an element, number 102, Berkeley quickly discredited the claim. Instead, Berkeley notched element 102, nobelium (after Alfred Nobel, dynamite inventor and founder of the Nobel Prizes), and element 103, lawrencium (after Berkeley Radiation Laboratory founder and director Ernest Lawrence), in the early 1960s.

Then, in 1964, a second Sputnik happened.

Some Russians have a creation myth about their corner of the planet. Way back when, the story goes, God walked the earth, carrying all its minerals in his arms, to make sure they got distributed evenly. This plan worked well for a while. Tantalum went in one land, uranium another, and so on. But when God got to Siberia, his fingers got so cold and stiff, he dropped all the metals. His hands too frostbit to scoop them up, he left them there in disgust. And this, Russians boast, explains their vast stores of minerals.

Despite those geological riches, only two useless elements on the periodic table were discovered in Russia, ruthenium and samarium. Compare that paltry record to the dozens of elements discovered in Sweden and Germany and France. The list of great Russian scientists beyond Mendeleev is similarly barren, at least in comparison to Europe proper. For various reasons—despotic tsars, an agrarian economy, poor schools, harsh weather—Russia just never fostered the scientific genius it might have. It couldn’t even get basic technologies right, such as its calendar. Until well past 1900, Russia used a misaligned calendar that Julius Caesar’s astrologers had invented, leaving it weeks behind Europe and its modern Gregorian calendar. That lag explains why the “October Revolution” that brought Vladimir Lenin and the Bolsheviks to power in 1917 actually occurred in November.

That revolution succeeded partly because Lenin promised to turn backward Russia around, and the Soviet Politburo insisted that scientists would be first among equals in the new workers’ paradise. Those claims held true for a few years, as scientists under Lenin went about their business with little state interference, and some world-class scientists emerged, amply supported by the state. In addition to making scientists happy, money turned out to be powerful propaganda as well. Noting how well-funded even mediocre Soviet colleagues were, scientists outside the Soviet Union hoped (and their hope led them to believe) that at last a powerful government recognized their importance. Even in America, where McCarthyism flourished in the early 1950s, scientists often looked fondly at the Soviet bloc for its material support of scientific progress.

In fact, groups like the ultra-right-wing John Birch Society, founded in 1958, thought the Soviets might even be a little too clever with their science. The society fulminated against the addition of fluoride (ions of fluorine) to tap water to prevent cavities. Aside from iodized salt, fluorinated water is among the cheapest and most effective public health measures ever enacted, enabling most people who drank it to die with their own teeth for the first time in history. To the Birchers, though, fluoridation was linked with sex education and other “filthy Communist plots” to control Americans’ minds, a mirrored fun house that led straight from local water officials and health teachers to the Kremlin. Most U.S. scientists watched the antiscience fearmongering of the John Birch Society with horror, and compared to that, the pro-science rhetoric of the Soviet Union must have seemed blissful.

Beneath that skin of progress, though, a tumor had metastasized. Joseph Stalin, who assumed despotic control over the Soviet Union in 1929, had peculiar ideas about science. He divided it—nonsensically, arbitrarily, and poisonously—into “bourgeois” and “proletarian” and punished anyone who practiced the former. For decades, the Soviet agricultural research program was run by a proletarian peasant, the “barefoot scientist” Trofim Lysenko. Stalin practically fell in love with him because Lysenko denounced the regressive idea that living things, including crops, inherit traits and genes from their parents. A proper Marxist, he preached that only the proper social environment mattered (even for plants) and that the Soviet environment would prove superior to the capitalist pig environment. As far as it was possible, he also made biology based on genes “illegal” and arrested or executed dissidents. Somehow Lysenkoism failed to boost crop yields, and the millions of collectivized farmers forced to adopt the doctrine starved. During those famines, an eminent British geneticist gloomily described Lysenko as “completely ignorant of the elementary principles of genetics and plant physiology…. To talk to Lysenko was like trying to explain the differential calculus to a man who did not know his twelve times table.”

Moreover, Stalin had no compunction about arresting scientists and forcing them to work for the state in slave labor camps. He shipped many scientists to a notorious nickel works and prison outside Norilsk, in Siberia, where temperatures regularly dropped to –80°F. Though primarily a nickel mine, Norilsk smelled permanently of sulfur, from diesel fumes, and scientists there slaved to extract a good portion of the toxic metals on the periodic table, including arsenic, lead, and cadmium. Pollution was rife, staining the sky, and depending on which heavy metal was in demand, it snowed pink or blue. When all the metals were in demand, it snowed black (and still does sometimes today). Perhaps most creepily, to this day reportedly not one tree grows within thirty miles of the poisonous nickel smelters.* In keeping with the macabre Russian sense of humor, a local joke says that bums in Norilsk, instead of begging for change, collect cups of rain, evaporate the water, and sell the scrap metal for cash. Jokes aside, much of a generation of Soviet science was squandered extracting nickel and other metals for Soviet industry.

An absolute realist, Stalin also distrusted spooky, counterintuitive branches of science such as quantum mechanics and relativity. As late as 1949, he considered liquidating the bourgeois physicists who would not conform to Communist ideology by dropping those theories. He drew back only when a brave adviser pointed out that this might harm the Soviet nuclear weapons program just a bit. Plus, unlike in other areas of science, Stalin’s “heart” was never really into purging physicists. Because physics overlaps with weapons research, Stalin’s pet, and remains agnostic in response to questions about human nature, Marxism’s pet, physicists under Stalin escaped the worst abuses leveled at biologists, psychologists, and economists. “Leave [physicists] in peace,” Stalin graciously allowed. “We can always shoot them later.”

Still, there’s another dimension to the pass that Stalin gave the physical sciences. Stalin demanded loyalty, and the Soviet nuclear weapons program had roots in one loyal subject, nuclear scientist Georgy Flyorov. In the most famous picture of him, Flyorov looks like someone in a vaudeville act: smirking, bald front to crown, a little overweight, with caterpillar eyebrows and an ugly striped tie—like someone who’d wear a squirting carnation in his lapel.

That “Uncky Georgy” look concealed shrewdness. In 1942, Flyorov noticed that despite the great progress German and American scientists had made in uranium fission research in recent years, scientific journals had stopped publishing on the topic. Flyorov deduced that the fission work had become state secrets—which could mean only one thing. In a letter that mirrored Einstein’s famous letter to Franklin Roosevelt about starting the Manhattan Project, Flyorov alerted Stalin about his suspicions. Stalin, roused and paranoid, rounded up physicists by the dozens and started them on the Soviet Union’s own atomic bomb project. But “Papa Joe” spared Flyorov and never forgot his loyalty.

Nowadays, knowing what a horror Stalin was, it’s easy to malign Flyorov, to label him Lysenko, part two. Had Flyorov kept quiet, Stalin might never have known about the nuclear bomb until August 1945. Flyorov’s case also evokes another possible explanation for Russia’s lack of scientific acumen: a culture of toadyism, which is anathema to science. (During Mendeleev’s time, in 1878, a Russian geologist named a mineral that contained samarium, element sixty-two, after his boss, one Colonel Samarski, a forgettable bureaucrat and mining official, and easily the least worthy eponym on the periodic table.)

But Flyorov’s case is ambiguous. He had seen many colleagues’ lives wasted—including 650 scientists rounded up in one unforgettable purge of the elite Academy of Sciences, many of whom were shot for traitorously “opposing progress.” In 1942, Flyorov, age twenty-nine, had deep scientific ambitions and the talent to realize them. Trapped as he was in his homeland, he knew that playing politics was his only hope of advancement. And Flyorov’s letter did work. Stalin and his successors were so pleased when the Soviet Union unleashed its own nuclear bomb in 1949 that, eight years later, officials entrusted Comrade Flyorov with his own research lab. It was an isolated facility eighty miles outside Moscow, in the city of Dubna, free from state interference. Aligning himself with Stalin was an understandable, if morally flawed, decision for the young man.

In Dubna, Flyorov smartly focused on “blackboard science”—prestigious but esoteric topics too hard to explain to laypeople and unlikely to ruffle narrow-minded ideologues. And by the 1960s, thanks to the Berkeley lab, finding new elements had shifted from what it had been for centuries—an operation where you got your hands dirty digging through obscure rocks—to a rarefied pursuit in which elements “existed” only as printouts on radiation detectors run by computers (or as fire alarm bells). Even smashing alpha particles into heavy elements was no longer practical, since heavy elements don’t sit still long enough to be targets.

Scientists instead reached deeper into the periodic table and tried to fuse lighter elements together. On the surface, these projects were all arithmetic. For element 102, you could theoretically smash magnesium (twelve) into thorium (ninety) or vanadium (twenty-three) into gold (seventy-nine). Few combinations stuck together, however, so scientists had to invest a lot of time in calculations to determine which pairs of elements were worth their money and effort. Flyorov and his colleagues studied hard and copied the techniques of the Berkeley lab. And thanks in large part to him, the Soviet Union had shrugged off its reputation as a backwater in physical science by the late 1950s. Seaborg, Ghiorso, and Berkeley beat the Russians to elements 101, 102, and 103. But in 1964, seven years after the original Sputnik, the Dubna team announced it had created element 104 first.

Back in berkelium, californium, anger followed shock. Its pride wounded, the Berkeley team checked the Soviet results and, not surprisingly, dismissed them as premature and sketchy. Meanwhile, Berkeley set out to create element 104 itself—which a Ghiorso team, advised by Seaborg, did in 1969. By that point, however, Dubna had bagged 105, too. Again Berkeley scrambled to catch up, all the while contesting that the Soviets were misreading their own data—a Molotov cocktail of an insult. Both teams produced element 106 in 1974, just months apart, and by that time all the international unity of mendelevium had evaporated.

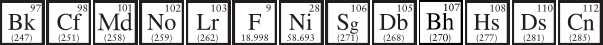

To cement their claims, both teams began naming “their” elements. The lists are tedious to get into, but it’s interesting that the Dubna team, à la berkelium, coined one element dubnium. For its part, Berkeley named element 105 after Otto Hahn and then, at Ghiorso’s insistence, named 106 after Glenn Seaborg—a living person—which wasn’t “illegal” but was considered gauche in an irritatingly American way. Across the world, dueling element names began appearing in academic journals, and printers of the periodic table had no idea how to sort through the mess.

Amazingly, this dispute stretched all the way to the 1990s, by which point, to add confusion, a team from West Germany had sprinted past the bickering Americans and Soviets to claim contested elements of their own. Eventually, the body that governs chemistry, the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC), had to step in and arbitrate.

IUPAC sent nine scientists to each lab for weeks to sort through innuendos and accusations and to look at primary data. The nine men met for weeks on their own, too, in a tribunal. In the end, they announced that the cold war adversaries would have to hold hands and share credit for each element. That Solomonic solution pleased no one: an element can have only one name, and the box on the table was the real prize.

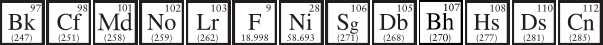

Finally, in 1995, the nine wise men announced tentatively official names for elements 104 to 109. The compromise pleased Dubna and Darmstadt (home of the West German group), but when the Berkeley team saw seaborgium deleted from the list, they went apoplectic. They called a press conference to basically say, “To hell with you; we’re using it in the U.S. of A.” A powerful American chemistry body, which publishes prestigious journals that chemists around the world very much like getting published in, backed Berkeley up. This changed the diplomatic situation, and the nine men buckled. When the really final, like-it-or-not list came out in 1996, it included seaborgium at 106, as well as the official names on the table today: rutherfordium (104), dubnium (105), borhium (107), hassium (108), and meitnerium (109). After their win, with a public relations foresight the New Yorker had once found lacking, the Berkeley team positioned an age-spotted Seaborg next to a huge periodic table, his gnarled finger pointing only sort of toward seaborgium, and snapped a photo. His sweet smile betrays nothing of the dispute whose first salvo had come thirty-two years earlier and whose bitterness had outlasted even the cold war. Seaborg died three years later.

After decades of bickering with Soviet and West German scientists, a satisfied but frail Glenn Seaborg points toward his namesake element, number 106, seaborgium, the only element ever named for a living person. (Photo courtesy Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory)

But a story like this cannot end tidily. By the 1990s, Berkeley chemistry was spent, limping behind its Russian and especially German peers. In remarkably quick succession, between just 1994 and 1996, the Germans stamped out element 110, now named darmstadtium (Ds), after their home base; element 111, roentgenium (Rg), after the great German scientist Wilhelm Röntgen; and element 112, the latest element added to the periodic table, in June 2009, copernicium (Cn).* The German success no doubt explained why Berkeley defended its claims for past glory so tenaciously: it had no prospect of future joy. Nevertheless, refusing to be eclipsed, Berkeley pulled a coup in 1996 by hiring a young Bulgarian named Victor Ninov—who had been instrumental in discovering elements 110 and 112—away from the Germans, to renew the storied Berkeley program. Ninov even lured Al Ghiorso out of semiretirement (“Ninov is as good as a young Al Ghiorso,” Ghiorso liked to say), and the Berkeley lab was soon surfing on optimism again.

For their big comeback, in 1999 the Ninov team pursued a controversial experiment proposed by a Polish theoretical physicist who had calculated that smashing krypton (thirty-six) into lead (eighty-two) just might produce element 118. Many denounced the calculation as poppycock, but Ninov, determined to conquer America as he had Germany, pushed for the experiment. Creating elements had grown into a multiyear, multimillion-dollar production by then, not something to undertake on a gamble, but the krypton experiment worked miraculously. “Victor must speak directly to God,” scientists joked. Best of all, element 118 decayed immediately, spitting out an alpha particle and becoming element 116, which had never been seen either. With one stroke, Berkeley had scored two elements! Rumors spread on the Berkeley campus that the team would reward old Al Ghiorso with his own element, 118, “ghiorsium.”

Except… when the Russians and Germans tried to confirm the results by rerunning the experiments, they couldn’t find element 118, just krypton and lead. This null result might have been spite, so part of the Berkeley team reran the experiment themselves. It found nothing, even after months of checking. Puzzled, the Berkeley administration stepped in. When they looked back at the original data files for element 118, they noticed something sickening: there was no data. No proof of element 118 existed until a late round of data analysis, when “hits” suddenly materialized from chaotic 1s and 0s. All signs indicated that Victor Ninov—who had controlled the all-important radiation detectors and the computer software that ran them—had inserted false positives into his data files and passed them off as real. It was an unforeseen danger of the esoteric approach to extending the periodic table: when elements exist only on computers, one person can fool the world by hijacking the computers.

Mortified, Berkeley retracted the claim for 118. Ninov was fired, and the Berkeley lab suffered major budget cuts, decimating it. To this day, Ninov denies that he faked any data—although, damningly, after his old German lab double-checked his experiments there by looking into old data files, it also retracted some (though not all) of Ninov’s findings. Perhaps worse, American scientists were reduced to traveling to Dubna to work on heavy elements. And there, in 2006, an international team announced that after smashing ten billion billion calcium atoms into a (gulp) californium target, they had produced three atoms of element 118. Fittingly, the claim for element 118 is contested, but if it holds up—and there’s no reason to think it won’t—the discovery would erase any chance of “ghiorsium” appearing on the periodic table. The Russians are in control, since it happened at their lab, and they’re said to be partial to “flyorium.”