The periodic table is a mercurial thing, and most elements are more complicated than the straightforward rogues of poisoner’s corridor. Obscure elements do obscure things inside the body—often bad, but sometimes good. An element toxic in one circumstance can become a lifesaving drug in another, and elements that get metabolized in unexpected ways can provide new diagnostic tools in doctors’ clinics. The interplay of elements and drugs can even illuminate how life itself emerges from the unconscious chemical slag of the periodic table.

The reputations of a few elemental medicines extend back a surprisingly long time. Roman officers supposedly enjoyed better health than their grunts because they took their meals on silver platters. And however useless hard currency was in the wild, most pioneer families in early America invested in at least one good silver coin, which spent its Conestoga wagon ride across the wilderness hidden in a milk jug—not for safekeeping, but to keep the milk from spoiling. The noted gentleman astronomer Tycho Brahe, who lost the bridge of his nose in a drunken sword duel in a dimly lit banquet hall in 1564, was even said to have ordered a replacement nose of silver. The metal was fashionable and, more important, curtailed infections. The only drawback was that its obviously metallic color forced Brahe to carry jars of foundation with him, which he was always smoothing over his nasal prosthesis.

Curious archaeologists later dug up Brahe’s body and found a green crust on the front of his skull—meaning Brahe had probably worn not a silver but a cheaper, lighter copper nose.* (Or perhaps he switched noses, like earrings, depending on the status of his company.) Either way, copper or silver, the story makes sense. Though both were long dismissed as folk remedies, modern science confirms that those elements have antiseptic powers. Silver is too dear for everyday use, but copper ducts and tubing are standard in the guts of buildings now, as public safety measures. Copper’s career in public health began just after America’s bicentennial, in 1976, when a plague broke out in a hotel in Philadelphia. Never-before-seen bacteria crept into the moist ducts of the building’s air-conditioning system that July, proliferated, and coasted through the vents on a bed of cool air. Within days, hundreds of people at the hotel came down with the “flu,” and thirty-four died. The hotel had rented out its convention center that week to a veterans group, the American Legion, and though not every victim belonged, the bug became known as Legionnaires’ disease.

The laws pushed through in reaction to the outbreak mandated cleaner air and water systems, and copper has proved the simplest, cheapest way to improve infrastructure. If certain bacteria, fungi, or algae inch across something made of copper, they absorb copper atoms, which disrupt their metabolism (human cells are unaffected). The microbes choke and die after a few hours. This effect—the oligodynamic, or “self-sterilizing,” effect—makes metals more sterile than wood or plastic and explains why we have brass doorknobs and metal railings in public places. It also explains why most of the well-handled coins of the U.S. realm contain close to 90 percent copper or (like pennies) are copper-coated.* Copper tubing in air-conditioning ducts cleans out the nasty bugs that fester inside there, too.

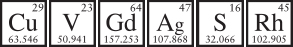

Similarly deadly to small wriggling cells, if a bit more quackish, is vanadium, element twenty-three, which also has a curious side effect in males: vanadium is the best spermicide ever devised. Most spermicides dissolve the fatty membrane that surrounds sperm cells, spilling their guts all over. Unfortunately, all cells have fatty membranes, so spermicides often irritate the lining of the vagina and make women susceptible to yeast infections. Not fun. Vanadium eschews any messy dissolving and simply cracks the crankshaft on the sperm’s tails. The tails then snap off, leaving the sperm whirling like one-oared rowboats.*

Vanadium hasn’t appeared on the market as a spermicide because—and this is a truism throughout medicine—knowing that an element or a drug has desirable effects in test tubes is much different from knowing how to harness those effects and create a safe medicine that humans can consume. For all its potency, vanadium is still a dubious element for the body to metabolize. Among other things, it mysteriously raises and lowers blood glucose levels. That’s why, despite its mild toxicity, vanadium water from (as some sites claim) the vanadium-rich springs of Mt. Fuji is sold online as a cure for diabetes.

Other elements have made the transition into effective medicines, like the hitherto useless gadolinium, a potential cancer assassin. Gadolinium’s value springs from its abundance of unpaired electrons. Despite the willingness of electrons to bond with other atoms, within their own atoms, they stay maximally far apart. Remember that electrons live in shells, and shells further break down into bunks called orbitals, each of which can accommodate two electrons. Curiously, electrons fill orbitals like patrons find seats on a bus: each electron sits by itself in an orbital until another electron is absolutely forced to double up.* When electrons do condescend to double up, they are picky. They always sit next to somebody with the opposite “spin,” a property related to an electron’s magnetic field. Linking electrons, spin, and magnets may seem weird, but all spinning charged particles have permanent magnetic fields, like tiny earths. When an electron buddies up with another electron with a contrary spin, their magnetic fields cancel out.

Gadolinium, which sits in the middle of the rare earth row, has the maximum number of electrons sitting by themselves. Having so many unpaired, noncanceling electrons allows gadolinium to be magnetized more strongly than any other element—a nice feature for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). MRI machines work by slightly magnetizing body tissue with powerful magnets and then flipping the magnets off. When the field releases, the tissue relaxes, reorients itself randomly, and becomes invisible to a magnetic field. Highly magnetic bits like gadolinium take longer to relax, and the MRI machine picks up on that difference. So by affixing gadolinium to tumor-targeting agents—chemicals that seek out and bind only to tumors—doctors can pick tumors out on an MRI scan more easily. Gadolinium basically cranks up the contrast between tumors and normal flesh, and depending on the machine, the tumor will either stand out like a white island in a sea of grayish tissue or appear as an inky cloud in a bright white sky.

Even better, gadolinium might do more than just diagnose tumors. It might also provide doctors with a way to kill those tumors with intense radiation. Gadolinium’s array of unpaired electrons allows it to absorb scads of neutrons, which normal body tissue cannot absorb well. Absorbing neutrons turns gadolinium radioactive, and when it goes nuclear, it shreds the tissue around it. Normally, triggering a nano-nuke inside the body is bad, but if doctors can induce tumors to absorb gadolinium, it’s sort of an enemy of an enemy thing. As a bonus, gadolinium also inhibits proteins that repair DNA, so the tumor cells cannot rebuild their tattered chromosomes. As anyone who has ever had cancer can attest, a focused gadolinium attack would be a tremendous improvement over chemotherapy and normal cancer radiation, both of which kill cancer cells by scorching everything around them, too. Whereas those techniques are more like firebombs, gadolinium could someday allow oncologists to make surgical strikes without surgery.*

This is not to say that element sixty-four is a wonder drug. Atoms have a way of drifting inside the body, and like any element the body doesn’t use regularly, gadolinium has side effects. It causes kidney problems in some patients who cannot flush it out of their systems, and others report that it causes their muscles to stiffen up like early stages of rigor mortis and their skin to harden like a hide, making breathing difficult in some cases. From the looks of it, there’s a healthy Internet industry of people claiming that gadolinium (usually taken for an MRI) has ruined their health.

As a matter of fact, the Internet is an interesting place to scout out general claims for obscure medicinal elements. With virtually every element that’s not a toxic metal (and even occasionally with those), you can find some alternative medicine site selling it as a supplement.* Probably not coincidentally, you’ll also find personal-injury firms on the Internet willing to sue somebody for exposure to nearly every element. So far, the health gurus seem to have spread their message farther and wider than the lawyers, and elemental medicines (e.g., the zinc in lozenges) continue to grow more popular, especially those that have roots as folk remedies. For a century, people gradually replaced folk remedies with prescription drugs, but declining confidence in Western medicine has led some people to self-administer “drugs” such as silver once more.*

Again, there is an ostensible scientific basis for using silver, since it has the same self-sterilizing effects as copper. The difference between silver and copper is that silver, if ingested, colors the skin blue. Permanently. And it’s actually worse than that sounds. Calling silvered skin “blue” is easy shorthand. But there’s the fun electric blue in people’s imaginations when they hear this, and then there’s the ghastly gray zombie-Smurf blue people actually turn.

Thankfully, this condition, called argyria, isn’t fatal and causes no internal damage. A man in the early 1900s even made a living as “the Blue Man” in a freak show after overdosing on silver nitrate to cure his syphilis. (It didn’t work.) In our own times, a survivalist and fierce Libertarian from Montana, the doughty and doughy Stan Jones, ran for the U.S. Senate in 2002 and 2006 despite being startlingly blue. To his credit, Jones had as much fun with himself as the media did. When asked what he told children and adults who pointed at him on the street, he deadpanned, “I just tell them I’m practicing my Halloween costume.”

Jones also gladly explained how he contracted argyria. Having his ear to the tin can about conspiracy theories, Jones became obsessed in 1995 with the Y2K computer crash, and especially with the potential lack of antibiotics in the coming apocalypse. His immune system, he decided, had better get ready. So he began to distill a heavy-metal moonshine in his backyard by dipping silver wires attached to 9-volt batteries into tubs of water—a method not even hard-core silver evangelists recommend, since electric currents that strong dissolve far too many silver ions in the bath. Jones drank his stash faithfully for four and a half years, right until Y2K fizzled out in January 2000.

Despite that dud, and despite being gawked at during his serial Senate campaigns, Jones remains unrepentant. He certainly wasn’t running for office to wake up the Food and Drug Administration, which in good libertarian fashion intervenes with elemental cures only when they cause acute harm or make promises they cannot possibly keep. A year after losing the 2002 election, Jones told a national magazine, “It’s my fault that I overdosed [on silver], but I still believe it’s the best antibiotic in the world…. If there were a biological attack on America or if I came down with any type of disease, I’d immediately take it again. Being alive is more important than turning purple.”

Stan Jones’s advice notwithstanding, the best modern medicines are not isolated elements but complex compounds. Nevertheless, in the history of modern drugs, a few unexpected elements have played an outsized role. This history largely concerns lesser-known heroic scientists such as Gerhard Domagk, but it starts with Louis Pasteur and a peculiar discovery he made about a property of biomolecules called handedness, which gets at the very essence of living matter.

Odds are you’re right-handed, but really you’re not. You’re left-handed. Every amino acid in every protein in your body has a left-handed twist to it. In fact, virtually every protein in every life form that has ever existed is exclusively left-handed. If astrobiologists ever find a microbe on a meteor or moon of Jupiter, almost the first thing they’ll test is the handedness of its proteins. If the proteins are left-handed, the microbe is possibly earthly contamination. If they’re right-handed, it’s certainly alien life.

Pasteur noticed this handedness because he began his career studying modest fragments of life as a chemist. In 1849, at age twenty-six, he was asked by a winery to investigate tartaric acid, a harmless waste product of wine production. Grape seeds and yeast carcasses decompose into tartaric acid and collect as crystals in the dregs of wine kegs. Yeast-born tartaric acid also has a curious property. Dissolve it in water and shine a vertical slit of light through the solution, and the beam will twist clockwise away from the vertical. It’s like rotating a dial. Industrial, human-made tartaric acid does nothing like that. A vertical beam emerges true and upright. Pasteur wanted to figure out why.

He determined that it had nothing to do with the chemistry of the two types of tartaric acid. They behaved identically in reactions, and the elemental composition of both was the same. Only when he examined the crystals with a magnifying glass did he notice any difference. The tartaric acid crystals from yeast all twisted in one direction, like tiny, severed left-handed fists. The industrial tartaric acid twisted both ways, a mixture of left- and right-handed fists. Intrigued, Pasteur began the unimaginably tedious job of separating the salt-sized grains into a lefty pile and a righty pile with tweezers. He then dissolved each pile in water and tested more beams of light. Just as he suspected, the yeastlike crystals rotated light clockwise, while the mirror-image crystals rotated light counterclockwise, and exactly the same number of degrees.

Pasteur mentioned these results to his mentor, Jean Baptiste Biot, who had first discovered that some compounds could twist light. The old man demanded that Pasteur show him—then nearly broke down, he was so deeply moved at the elegance of the experiment. In essence, Pasteur had shown that there are two identical but mirror-image types of tartaric acid. More important, Pasteur later expanded this idea to show that life has a strong bias for molecules of only one handedness, or “chirality.”*

Pasteur later admitted he’d been a little lucky with this brilliant work. Tartaric acid, unlike most molecules, is easy to see as chiral. In addition, although no one could have anticipated a link between chirality and rotating light, Pasteur had Biot to guide him through the optical rotation experiments. Most serendipitously, the weather cooperated. When preparing the man-made tartaric acid, Pasteur had cooled it on a windowsill. The acid separates into left- and right-handed crystals only below 79°F, and had it been warmer that season, he never would have discovered handedness. Still, Pasteur knew that luck explained just part of his success. As he himself declared, “Chance favors only the prepared mind.”

Pasteur was skilled enough for this “luck” to persist throughout his life. Though not the first to do so, he performed an ingenious experiment on meat broth in sterile flasks and proved definitively that air contains no “vitalizing element,” no spirit that can summon life from dead matter. Life is built solely, if mysteriously, from the elements on the periodic table. Pasteur also developed pasteurization, a process that heats milk to kill infectious diseases; and, most famously at the time, he saved a young boy’s life with his rabies vaccine. For the latter deed, he became a national hero, and he parlayed that fame into the clout he needed to open an eponymous institute outside Paris to further his revolutionary germ theory of disease.

Not quite coincidentally, it was at the Pasteur Institute in the 1930s that a few vengeful, vindictive scientists figured out how the first laboratory-made pharmaceuticals worked—and in doing so hung yet another millstone around the neck of Pasteur’s intellectual descendant, the great microbiologist of his era, Gerhard Domagk.

In early December 1935, Domagk’s daughter Hildegard tripped down the staircase of the family home in Wuppertal, Germany, while holding a sewing needle. The needle punctured her hand, eyelet first, and snapped off inside her. A doctor extracted the shard, but days later Hildegard was languishing, suffering from a high fever and a brutal streptococcal infection all up and down her arm. As she grew worse, Domagk himself languished and suffered, because death was a frighteningly common outcome for such infections. Once the bacteria began multiplying, no known drug could check their greed.

Except there was one drug—or, rather, one possible drug. It was really a red industrial dye that Domagk had been quietly testing in his lab. On December 20, 1932, he had injected a litter of mice with ten times the lethal dose of streptococcal bacteria. He had done the same with another litter. He’d also injected the second litter with that industrial dye, prontosil, ninety minutes later. On Christmas Eve, Domagk, until that day an insignificant chemist, stole back into his lab to peek. Every mouse in the second litter was alive. Every mouse in the first had died.

That wasn’t the only fact confronting Domagk as he kept vigil over Hildegard. Prontosil—a ringed organic molecule that, a little unusually, contains a sulfur atom—had unpredictable properties. Germans at the time believed, a little oddly, that dyes killed germs by turning the germs’ vital organs the wrong color. But prontosil, though lethal to microbes inside mice, had no effect on bacteria in test tubes. They swam around happily in the red wash. No one knew why, and because of that ignorance, numerous European doctors had attacked German “chemotherapy,” dismissing it as inferior to surgery in treating infection. Even Domagk didn’t quite believe in his drug. Between the mouse experiment in 1932 and Hildegard’s accident, tentative clinical trials in humans had gone well, but with occasional serious side effects (not to mention that it caused people to flush bright red, like lobsters). Although he was willing to risk the possible deaths of patients in clinical trials for the greater good, risking his daughter was another matter.

In this dilemma, Domagk found himself in the same situation that Pasteur had fifty years before, when a young mother had brought her son, so mangled by a rabid dog he could barely walk, to Pasteur in France. Pasteur treated the boy with a rabies vaccine tested only on animals, and the boy lived.* Pasteur wasn’t a licensed doctor, and he administered the vaccine despite the threat of criminal prosecution if it failed. If Domagk failed, he would have the additional burden of having killed a family member. Yet as Hildegard sank further, he likely could not rid his memory of the two cages of mice that Christmas Eve, one teeming with busy rodents, the other still. When Hildegard’s doctor announced he would have to amputate her arm, Domagk laid aside his caution. Violating pretty much every research protocol you could draw up, he sneaked some doses of the experimental drug from his lab and began injecting her with the blood-colored serum.

At first Hildegard worsened. Her fever alternately spiked and crashed over the next couple of weeks. Suddenly, exactly three years after her father’s mouse experiment, Hildegard stabilized. She would live, with both arms intact.

Though euphoric, Domagk held back mentioning his clandestine experiment to his colleagues, so as not to bias the clinical trials. But his colleagues didn’t need to hear about Hildegard to know that Domagk had found a blockbuster—the first genuine antibacterial drug. It’s hard to overstate what a revelation this drug was. The world in Domagk’s day was modern in many ways. People had quick cross-continental transportation via trains and quick international communication via the telegraph; what they didn’t have was much hope of surviving even common infections. With prontosil, plagues that had ravaged human beings since history began seemed conquerable and might even be eradicated. The only remaining question was how prontosil worked.

Not to break my authorial distance, but the following explanation must be chaperoned with an apology. After expounding on the utility of the octet rule, I hate telling you that there are exceptions and that prontosil succeeds as a drug largely because it violates this rule. Specifically, if surrounded by stronger-willed elements, sulfur will farm out all six of its outer-shell electrons and expand its octet into a dozenet. In prontosil’s case, the sulfur shares one electron with a benzene ring of carbon atoms, one with a short nitrogen chain, and two each with two greedy oxygen atoms. That’s six bonds with twelve electrons, a lot to juggle. And no element but sulfur could pull it off. Sulfur lies in the periodic table’s third row, so it’s large enough to take on more than eight electrons and bring all those important parts together; yet it’s only in the third row and therefore small enough to let everything fit around it in the proper three-dimensional arrangement.

Domagk, primarily a bacteriologist, was ignorant of all that chemistry, and he eventually decided to publish his results so other scientists could help him figure out how prontosil works. But there were tricky business issues to consider. The chemical cartel Domagk worked for, I. G. Farbenindustrie (IGF, the company that later manufactured Fritz Haber’s Zyklon B), already sold prontosil as a dye, but it filed for a patent extension on prontosil as a medicine immediately after Christmas in 1932. And with clinical proof that the drug worked well in humans, IGF was fervid about maintaining its intellectual property rights. When Domagk pushed to publish his results, the company forced him to hold back until the medicinal patent on prontosil came through, a delay that earned Domagk and IGF criticism, since people died while lawyers quibbled. Then IGF made Domagk publish in an obscure, German-only periodical, to prevent other firms from finding out about prontosil.

Despite the precaution, and despite prontosil’s revolutionary promise, the drug flopped when it hit the market. Foreign doctors continued to harangue about it and many simply didn’t believe it could work. Not until the drug saved the life of Franklin Delano Roosevelt Jr., who was struck by a severe strep throat in 1936, and earned a headline in the New York Times did prontosil and its lone sulfur atom win any respect. Suddenly, Domagk might as well have been an alchemist for all the money IGF stood to make, and any ignorance about how prontosil worked seemed trifling. Who cared when sales figures jumped fivefold in 1936, then fivefold more the next year.

Meanwhile, scientists at the Pasteur Institute in France had dug up Domagk’s obscure journal article. In a froth that was equal parts anti–intellectual property (because they hated how patents hindered basic research) and anti-Teuton (because they hated Germans), the Frenchmen immediately set about busting the IGF patent. (Never underestimate spite as a motivator for genius.)

Prontosil worked as well as advertised on bacteria, but the Pasteur scientists noticed some odd things when they traced its course through the body. First, it wasn’t prontosil that fought off bacteria, but a derivative of it, sulfonamide, which mammal cells produce by splitting prontosil in two. This explained instantly why bacteria in test tubes had not been affected: no mammal cells had biologically “activated” the prontosil by cleaving it. Second, sulfonamide, with its central sulfur atom and hexapus of side chains, disrupts the production of folic acid, a nutrient all cells use to replicate DNA and reproduce. Mammals get folic acid from their diets, which means sulfonamide doesn’t hobble their cells. But bacteria have to manufacture their own folic acid or they can’t undergo mitosis and spread. In effect, then, the Frenchmen proved that Domagk had discovered not a bacteria killer but bacteria birth control!

This breakdown of prontosil was stunning news, and not just medically stunning. The important bit of prontosil, sulfonamide, had been invented years before. It had even been patented in 1909—by I. G. Farbenindustrie*—but had languished because the company had tested it only as a dye. By the mid-1930s, the patent had expired. The Pasteur Institute scientists published their results with undisguised glee, giving everyone in the world a license to circumvent the prontosil patent. Domagk and IGF of course protested that prontosil, not sulfonamide, was the crucial component. But as evidence accumulated against them, they dropped their claims. The company lost millions in product investment, and probably hundreds of millions in profits, as competitors swept in and synthesized other “sulfa drugs.”

Despite Domagk’s professional frustration, his peers understood what he’d done, and they rewarded Pasteur’s heir with the 1939 Nobel Prize in Medicine or Physiology, just seven years after the Christmas mice experiment. But if anything, the Nobel made Domagk’s life worse. Hitler hated the Nobel committee for awarding the 1935 Peace Prize to an anti-Nazi journalist and pacifist, and Die Führer had made it basically illegal for any German to win a Nobel Prize. As such, the Gestapo arrested and brutalized Domagk for his “crime.” When World War II broke out, Domagk redeemed himself a little by convincing the Nazis (they refused to believe at first) that his drugs could save soldiers suffering from gangrene. But the Allies had sulfa drugs by then, too, and it couldn’t have increased Domagk’s popularity when his drugs saved Winston Churchill in 1942, a man bent on destroying Germany.

Perhaps even worse, the drug Domagk had trusted to save his daughter’s life became a dangerous fad. People demanded sulfonamide for every sore throat and sniffle and soon saw it as some sort of elixir. Their hopes became a nasty joke when quick-buck salesmen in the United States took advantage of this mania by peddling sulfas sweetened with antifreeze. Hundreds died within weeks—further proof that when it comes to panaceas the credulity of human beings is boundless.

Antibiotics were the culmination of Pasteur’s discoveries about germs. But not all diseases are germ-based; many have roots in chemical or hormonal troubles. And modern medicine began to address that second class of diseases only after embracing Pasteur’s other great insight into biology, chirality. Not long after offering his opinion about chance and the prepared mind, Pasteur said something else that, if not as pithy, stirs a deeper sense of wonder, because it gets at something truly mysterious: what makes life live. After determining that life has a bias toward handedness on a deep level, Pasteur suggested that chirality was the sole “well-marked line of demarcation that at the present can be drawn between the chemistry of dead matter and the chemistry of living matter.”* If you’ve ever wondered what defines life, chemically there’s your answer.

Pasteur’s statement guided biochemistry for a century, during which doctors made incredible progress in understanding diseases. At the same time, the insight implied that curing diseases, the real prize, would require chiral hormones and chiral biochemicals—and scientists realized that Pasteur’s dictum, however perceptive and helpful, subtly highlighted their own ignorance. That is, in pointing out the gulf between the “dead” chemistry that scientists could do in the lab and the living cellular chemistry that supported life, Pasteur simultaneously pointed out there was no easy way to cross it.

That didn’t stop people from trying. Some scientists obtained chiral chemicals by distilling essences and hormones from animals, but in the end that proved too arduous. (In the 1920s, two Chicago chemists had to puree several thousand pounds of bull testicles from a stockyard to get a few ounces of the first pure testosterone.) The other possible approach was to ignore Pasteur’s distinction and manufacture both right-handed and left-handed versions of biochemicals. This was actually fairly easy to do because, statistically, reactions that produce handed molecules are equally likely to form righties and lefties. The problem with this approach is that mirror-image molecules have different properties inside the body. The zesty odor of lemons and oranges derives from the same basic molecules, one right-handed and one left-handed. Wrong-handed molecules can even destroy left-handed biology. A German drug company in the 1950s began marketing a remedy for morning sickness in pregnant women, but the benign, curative form of the active ingredient was mixed in with the wrong-handed form because the scientists couldn’t separate them. The freakish birth defects that followed—especially children born without legs or arms, their hands and feet stitched like turtle flippers to their trunks—made thalidomide the most notorious pharmaceutical of the twentieth century.*

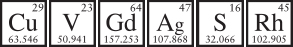

As the thalidomide disaster unfolded, the prospects of chiral drugs seemed dimmer than ever. But at the same time people were publicly mourning thalidomide babies, a St. Louis chemist named William Knowles began playing around with an unlikely elemental hero, rhodium, in a private research lab at Monsanto, an agricultural company. Knowles quietly circumvented Pasteur and proved that “dead” matter, if you were clever about it, could indeed invigorate living matter.

Knowles had a flat, two-dimensional molecule he wanted to inflate into three dimensions, because the left-handed version of the 3D molecule had shown promising effects on brain diseases such as Parkinson’s. The sticking point was getting the proper handedness. Notice that 2D objects cannot be chiral: after all, a flat cardboard cutout of your right hand can be flipped over to make a left hand. Handedness emerges only with the z-axis. But inanimate chemicals in a reaction don’t know to make one hand or the other.* They make both, unless they’re tricked.

Knowles’s trick was a rhodium catalyst. Catalysts speed up chemical reactions to degrees that are hard to comprehend in our poky, everyday human world. Some catalysts improve reaction rates by millions, billions, or even trillions of times. Rhodium works pretty fast, and Knowles found that one rhodium atom could inflate innumerably many of his 2D molecules. So he affixed the rhodium to the center of an already chiral compound, creating a chiral catalyst.

The clever part was that both the chiral catalyst with the rhodium atom and the target 2D molecule were sprawling and bulky. So when they approached each other to react, they did so like two obese animals trying to have sex. That is, the chiral compound could poke its rhodium atom into the 2D molecule only from one position. And from that position, with arms and belly flab in the way, the 2D molecule could unfold into a 3D molecule in only one dimension.

That limited maneuverability during coitus, coupled with rhodium’s catalytic ability to fast-forward reactions, meant that Knowles could get away with doing only a bit of the hard work—making a chiral rhodium catalyst—and still reap bushels of correctly handed molecules.

The year was 1968, and modern drug synthesis began at that moment—a moment later honored with a Nobel Prize in Chemistry for Knowles in 2001.

Incidentally, the drug that rhodium churned out for Knowles is levo-dihydroxyphenylalanine, or L-dopa, a compound since made famous in Oliver Sacks’s book Awakenings. The book documents how L-dopa shook awake eighty patients who’d developed extreme Parkinson’s disease after contracting sleeping sickness (Encephalitis lethargica) in the 1920s. All eighty were institutionalized, and many had spent four decades in a neurological haze, a few in continuous catatonia. Sacks describes them as “totally lacking energy, impetus, initiative, motive, appetite, affect, or desire… as insubstantial as ghosts, and as passive as zombies… extinct volcanoes.”

In 1967, a doctor had had great success in treating Parkinson’s patients with L-dopa, a precursor of the brain chemical dopamine. (Like Domagk’s prontosil, L-dopa must be biologically activated in the body.) But the right- and left-handed forms of the molecule were knotty to separate, and the drug cost upwards of $5,000 per pound. Miraculously—though without being aware why—Sacks notes that “towards the end of 1968 the cost of L-dopa started a sharp decline.” Freed by Knowles’s breakthrough, Sacks began treating his catatonic patients in New York not long after, and “in the spring of 1969, in a way… which no one could have imagined or foreseen, these ‘extinct volcanoes’ erupted into life.”

The volcano metaphor is accurate, as the effects of the drug weren’t wholly benign. Some people became hyperkinetic, with racing thoughts, and others began to hallucinate or gnaw on things like animals. But these forgotten people almost uniformly preferred the mania of L-dopa to their former listlessness. Sacks recalls that their families and the hospital staff had long considered them “effectively dead,” and even some of the victims considered themselves so. Only the left-handed version of Knowles’s drug revived them. Once again, Pasteur’s dictum about the life-giving properties of proper-handed chemicals proved true.