There’s a conundrum near the fringes of the periodic table. Highly radioactive elements are always scarce, so you’d think, intuitively, the element that falls apart the most easily would also be the most scarce. And the element that is effaced most quickly and thoroughly whenever it appears in the earth’s crust, ultra-fragile francium, is indeed rare. Francium winks out of existence on a timescale quicker than any other natural atom—yet one element is even rarer than francium. It’s a paradox, and resolving the paradox actually requires leaving behind the comfortable confines of the periodic table. It requires setting out for what nuclear physicists consider their New World, their America to conquer—the “island of stability”—which is their best and perhaps only hope for extending the table beyond its current limitations.

As we know, 90 percent of particles in the universe are hydrogen, and the other 10 percent are helium. Everything else, including six million billion billion kilos of earth, is a cosmic rounding error. And in that six million billion billion kilos, the total amount of astatine, the scarcest natural element, is one stupid ounce. To put that into some sort of (barely) comprehensible scope, imagine that you lost your Buick Astatine in an immense parking garage and you have zero idea where it is. Imagine the tedium of walking down every row on every level past every space, looking for your vehicle. To mimic hunting for astatine atoms inside the earth, that parking garage would have to be about 100 million spaces wide, have 100 million rows, and be 100 million stories high. And there would have to be 160 identical garages just as big—and in all those buildings, there’d be just one Astatine. You’d be better off walking home.

If astatine is so rare, it’s natural to ask how scientists ever took a census of it. The answer is, they cheated a little. Any astatine present in the early earth has long since disintegrated radioactively, but other radioactive elements sometimes decay into astatine after they spit out alpha or beta particles. By knowing the total amount of the parent elements (usually elements near uranium) and calculating the odds that each of those will decay into astatine, scientists can ring up some plausible numbers for how many astatine atoms exist. This works for other elements, too. For instance, at least twenty to thirty ounces of astatine’s near neighbor on the periodic table, francium, exist at any moment.

Funnily enough, astatine is at the same time far more robust than francium. If you had a million atoms of the longest-lived type of astatine, half of them would disintegrate in four hundred minutes. A similar sample of francium would hang on for just twenty minutes. Francium is so fragile it’s basically useless, and even though there’s (barely) enough of it in the earth for chemists to detect it directly, no one will ever herd enough atoms of it together to make a visible sample. If they did, it would be so intensely radioactive it would murder them immediately. (The current flash-mob record for francium is ten thousand atoms.)

No one will likely ever produce a visible sample of astatine either, but at least it’s good for something—as a quick-acting radioisotope in medicine. In fact, after scientists—led by our old friend Emilio Segrè—identified astatine in 1939, they injected a sample into a guinea pig to study it. Because astatine sits below iodine on the periodic table, it acts like iodine in the body and so was selectively filtered and concentrated by the rodent’s thyroid gland. Astatine remains the only element whose discovery was confirmed by a nonprimate.

The odd reciprocity between astatine and francium begins in their nuclei. There, as in all atoms, two forces struggle for dominance: the strong nuclear force (which is always attractive) and the electrostatic force (which can repel particles). Though the most powerful of nature’s four fundamental forces, the strong nuclear force has ridiculously short arms. Think Tyrannosaurus rex. If particles stray more than a few trillionths of an inch apart, the strong force is impotent. For that reason, it rarely comes into play outside nuclei and black holes. Yet within its range, it’s a hundred times more muscular than the electrostatic force. That’s good, because it keeps protons and neutrons bound together instead of letting the electrostatic force wrench nuclei apart.

When you get to nuclei the size of astatine and francium, the limited reach really catches up with the strong force, and it has trouble binding all the protons and neutrons together. Francium has eighty-seven protons, none of which want to touch. Its 130-odd neutrons buffer the positive charges well but also add so much bulk that the strong force cannot reach all the way across a nucleus to quell civil strife. This makes francium (and astatine, for similar reasons) highly unstable. And it stands to reason that adding more protons would increase electric repulsion, making atoms heavier than francium even weaker.

That’s only sort of correct, though. Remember that Maria Goeppert-Mayer (“S.D. Mother Wins Nobel Prize”) developed a theory about long-lived “magic” elements—atoms with two, eight, twenty, twenty-eight, etc., protons or neutrons that were extra-stable. Other numbers of protons or neutrons, such as ninety-two, also form compact and fairly stable nuclei, where the short-leashed strong force can tighten its grip on protons. That’s why uranium is more stable than either astatine or francium, despite being heavier. As you move down the periodic table element by element, then, the struggle between the strong nuclear and electrostatic forces resembles a plummeting stock market ticker, with an overall downward trend in stability, but with many wiggles and fluctuations as one force gains the upper hand, then the other.*

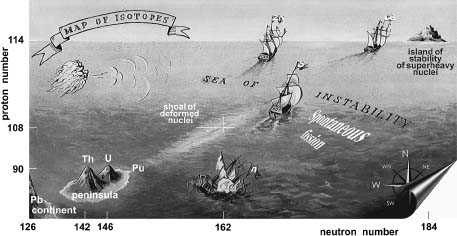

Based on this prevailing pattern, scientists assumed that the elements beyond uranium would asymptotically approach a life span of 0.0. But as they groped forward with the ultraheavy elements in the 1950s and 1960s, something unexpected happened. In theory, magic numbers extend until infinity, and it turned out that there was a quasi-stable nucleus after uranium, at element 114. And instead of it being fractionally more stable, scientists at (where else?) the University of California at Berkeley calculated that 114 might survive orders of magnitude longer than the ten or so heavy elements preceding it. Given the dismally short life span of heavy elements (microseconds at best), this was a wild, counterintuitive idea. Packing neutrons and protons onto most man-made elements is like packing on explosives, since you’re putting more stress on the nucleus. Yet with element 114, packing on more TNT seemed to steady the bomb. Just as strangely, elements such as 112 and 116 seemed (on paper at least) to get horseshoes-and-kisses benefits from having close to 114 protons. Even being around that quasi-magic number calmed them. Scientists began calling this cluster of elements the island of stability.

A whimsical map of the fabled “island of stability,” a clump of superheavy elements that scientists hope will allow them to extend the periodic table far past its present bounds. Notice the stable lead (Pb) continent of the main-body periodic table, the watery trench of unstable elements, and the small, semi-stable peaks at thorium and uranium before the sea opens up. (Yuri Oganessian, Joint Institute for Nuclear Research, Dubna, Russia)

Charmed by their own metaphor, and flattering themselves as brave explorers, scientists began preparing to conquer the island. They spoke of finding an elemental “Atlantis,” and some, like old-time sailors, even produced sepia “charts” of unknown nucleic seas. (You’d half expect to see krakens drawn in the waters.) And for decades now, attempts to reach that oasis of superheavy elements have made up one of the most exciting fields of physics. Scientists haven’t reached land yet (to get truly stable, doubly magic elements, they need to figure out ways to add more neutrons to their targets), but they’re in the island’s shallows, paddling around for a harbor.

Of course, an island of stability implies a stretch of submerged stability—a stretch centered on francium. Element eighty-seven is stranded between a magic nucleus at eighty-two and a quasi-stable nucleus at ninety-two, and it’s all too tempting for its neutrons and protons to abandon ship and swim. In fact, because of the poor structural foundation of its nucleus, francium is not only the least stable natural element, it’s less stable than every synthetic element up to 104, the ungainly rutherfordium. If there’s a “trench of instability,” francium is gargling bubbles at the bottom of the Mariana.

Still, it’s more abundant than astatine. Why? Because many radioactive elements around uranium happen to decay into francium as they disintegrate. But francium, instead of doing the normal alpha decay and thereby converting itself (through the loss of two protons) into astatine, decides more than 99.9 percent of the time to relieve the pressure in its nucleus by undergoing beta decay and becoming radium. Radium then undergoes a cascade of alpha decays that leap over astatine. In other words, the path of many decaying atoms leads to a short layover on francium—hence the twenty to thirty ounces of it. At the same time, francium shuttles atoms away from astatine, causing astatine to remain rare. Conundrum solved.

Now that we’ve plumbed the trenches, what about that island of stability? It’s doubtful that chemists will ever synthesize all the elements up to very high magic numbers. But perhaps they can synthesize a stable element 114, then 126, then go from there. Some scientists believe, too, that adding electrons to extra-heavy atoms can stabilize their nuclei—the electrons might act as springs and shocks to absorb the energy that atoms normally dedicate to tearing themselves apart. If that’s so, maybe elements in the 140s, 160s, and 180s are possible. The island of stability would become a chain of islands. These stable islands would get farther apart, but perhaps, like Polynesian canoers, scientists can cross some wild distances on the new periodic archipelago.

The thrilling part is that those new elements, instead of being just heavier versions of what we already know, could have novel properties (remember how lead emerges from a lineage of carbon and silicon). According to some calculations, if electrons can tame superheavy nuclei and make them more stable, those nuclei can manipulate electrons, too—in which case, electrons might fill the atoms’ shells and orbitals in a different order. Elements whose address on the table should make them normal heavy metals might fill in their octets early and act like metallic noble gases instead.

Not to tempt the gods of hubris, but scientists already have names for those hypothetical elements. You may have noticed that the extra-heavy elements along the bottom of the table get three letters instead of two and that all of them start with u. Once again, it’s the lingering influence of Latin and Greek. As yet undiscovered element 119, Uue, is un·un·ennium; element 122, Ubb, is un·bi·bium;* and so on. Those elements will receive “real” names if they’re ever made, but for now scientists can jot them down—and mark off other elements of interest, such as magic number 184, un·oct·quadium—with Latin substitutes. (And thank goodness for them. With the impending death of the binomial species system in biology—the system that gave us Felis catus for the house cat is gradually being replaced with chromosomal DNA “bar codes,” so good-bye Homo sapiens, the knowing ape, hello TCATCGGTCATTGG…—the u elements remain about the only holdouts of once-dominant Latin in science.*)

So how far can this island-hopping extend? Can we watch little volcanoes rise beneath the periodic table forever, watch it expand and stretch down to the fittingly wide Eee, enn·enn·ennium, element 999, or even beyond? Sigh, no. Even if scientists figure out how to glue extra-heavy elements together, and even if they land smack on the farther-off islands of stability, they’ll almost certainly skid right off into the messy seas.

The reason traces back to Albert Einstein and the biggest failure of his career. Despite the earnest belief of most of his fans, Einstein did not win his Nobel Prize for the theory of relativity, special or general. He won for explaining a strange effect in quantum mechanics, the photoelectric effect. His solution provided the first real evidence that quantum mechanics wasn’t a crude stopgap for justifying anomalous experiments, but actually corresponds to reality. And the fact that Einstein came up with it is ironic for two reasons. One, as he got older and crustier, Einstein came to distrust quantum mechanics. Its statistical and deeply probabilistic nature sounded too much like gambling to him, and it prompted him to object that “God does not play dice with the universe.” He was wrong, and it’s too bad that most people have never heard the rejoinder by Niels Bohr: “Einstein! Stop telling God what to do.”

Second, although Einstein spent his career trying to unify quantum mechanics and relativity into a coherent and svelte “theory of everything,” he failed. Not completely, however. Sometimes when the two theories touch, they complement each other brilliantly: relativistic corrections of the speed of electrons help explain why mercury (the element I’m always looking out for) is a liquid and not the expected solid at room temperature. And no one could have created his namesake element, number ninety-nine, einsteinium, without knowledge of both theories. But overall, Einstein’s ideas on gravity, the speed of light, and relativity don’t quite fit with quantum mechanics. In some cases where the two theories come into contact, such as inside black holes, all the fancy equations break down.

That breakdown could set limits on the periodic table. To return to the electron-planet analogy, just as Mercury zips around the sun every three months while Neptune drags on for 165 years, inner electrons orbit much more quickly around a nucleus than electrons in outer shells. The exact speed depends on the ratio between the number of protons present and alpha, the fine structure constant discussed last chapter. As that ratio gets closer and closer to one, electrons fly closer and closer to the speed of light. But remember that alpha is (we think) fixed at 1/137 or so. Beyond 137 protons, the inner electrons would seem to be going faster than the speed of light—which, according to Einstein’s relativity theory, can never happen.

This hypothetically last element, 137, is often called “feynmanium,” after Richard Feynman, the physicist who first noticed this pickle. He’s also the one who called alpha “one of the great damn mysteries of the universe,” and now you can see why. As the irresistible force of quantum mechanics meets the immovable object of relativity just past feynmanium, something has to give. No one knows what.

Some physicists, the kind of people who think seriously about time travel, think that relativity may have a loophole that allows special (and, conveniently, unobservable) particles called tachyons to go faster than light’s 186,000 miles per second. The catch with tachyons is that they may move backward in time. So if super-chemists someday create feynmanium-plus-one, un·tri·octium, would its inner electrons become time travelers while the rest of the atom sits pat? Probably not. Probably the speed of light simply puts a hard cap on the size of atoms, which would obliterate those fanciful islands of stability as thoroughly as A-bomb tests did coral atolls in the 1950s.

So does that mean the periodic table will be kaput soon? Fixed and frozen, a fossil?

No, no, and no again.

If aliens ever land and park here, there’s no guarantee we’ll be able to communicate with them, even going beyond the obvious fact they won’t speak “Earth.” They might use pheromones or pulses of light instead of sounds; they might also be, especially on the off off chance they’re not made of carbon, poisonous to be around. Even if we do break into their minds, our primary concerns—love, gods, respect, family, money, peace—may not register with them. About the only things we can drop in front of them and be sure they’ll grasp are numbers like pi and the periodic table.

Of course, that should be the properties of the periodic table, since the standard castles-with-turrets look of our table, though chiseled into the back of every extant chemistry book, is just one possible arrangement of elements. Many of our grandfathers grew up with quite a different table, one just eight columns wide all the way down. It looked more like a calendar, with all the rows of the transition metals triangled off into half boxes, like those unfortunate 30s and 31s in awkwardly arranged months. Even more dubiously, a few people shoved the lanthanides into the main body of the table, creating a crowded mess.

No one thought to give the transition metals a little more space until Glenn Seaborg and his colleagues at (wait for it) the University of California at Berkeley made over the entire periodic table between the late 1930s and early 1960s. It wasn’t just that they added elements. They also realized that elements like actinium didn’t fit into the scheme they’d grown up with. Again, it sounds odd to say, but chemists before this didn’t take periodicity seriously enough. They thought the lanthanides and their annoying chemistry were exceptions to the normal periodic table rules—that no elements below the lanthanides would ever bury electrons and deviate from transition-metal chemistry in the same way. But the lanthanide chemistry does repeat. It has to: that’s the categorical imperative of chemistry, the property of elements the aliens would recognize. And they’d recognize as surely as Seaborg did that the elements diverge into something new and strange right after actinium, element eighty-nine.

Actinium was the key element in giving the modern periodic table its shape, since Seaborg and his colleagues decided to cleave all the heavy elements known at the time—now called the actinides, after their first brother—and cordon them off at the bottom of the table. As long as they were moving those elements, they decided to give the transition metals more elbow room, too, and instead of cramming them into triangles, they added ten columns to the table. This blueprint made so much sense that many people copied Seaborg. It took a while for the hard-liners who preferred the old table to die off, but in the 1970s the periodic calendar finally shifted to become the periodic castle, the bulwark of modern chemistry.

But who says that’s the ideal shape? The columnar form has dominated since Mendeleev’s day, but Mendeleev himself designed thirty different periodic tables, and by the 1970s scientists had designed more than seven hundred variations. Some chemists like to snap off the turret on one side and attach it to the other, so the periodic table looks like an awkward staircase. Others fuss with hydrogen and helium, dropping them into different columns to emphasize that those two non-octet elements get themselves into strange situations chemically.

Really, though, once you start playing around with the periodic table’s form, there’s no reason to limit yourself to rectilinear shapes.* One clever modern periodic table looks like a honeycomb, with each hexagonal box spiraling outward in wider and wider arms from the hydrogen core. Astronomers and astrophysicists might like the version where a hydrogen “sun” sits at the center of the table, and all the other elements orbit it like planets with moons. Biologists have mapped the periodic table onto helixes, like our DNA, and geeks have sketched out periodic tables where rows and columns double back on themselves and wrap around the paper like the board game Parcheesi. Someone even holds a U.S. patent (#6361324) for a pyramidal Rubik’s Cube toy whose twistable faces contain elements.

Musically inclined people have graphed elements onto musical staffs, and our old friend William Crookes, the spiritualist seeker, designed two fittingly fanciful periodic tables, one that looked like a lute and another like a pretzel. My own favorite tables are a pyramid-shaped one—which very sensibly gets wider row by row and demonstrates graphically where new orbitals arise and how many more elements fit themselves into the overall system—and a cutout one with twists in the middle, which I can’t quite figure out but enjoy because it looks like a Möbius strip.

We don’t even have to limit periodic tables to two dimensions anymore. The negatively charged antiprotons that Segrè discovered in 1955 pair very nicely with antielectrons (i.e., positrons) to form anti-hydrogen atoms. In theory, every other anti-element on the anti–periodic table might exist, too. And beyond just that looking-glass version of the regular periodic table, chemists are exploring new forms of matter that could multiply the number of known “elements” into the hundreds if not thousands.

First are superatoms. These clusters—between eight and one hundred atoms of one element—have the eerie ability to mimic single atoms of different elements. For instance, thirteen aluminium atoms grouped together in the right way do a killer bromine: the two entities are indistinguishable in chemical reactions. This happens despite the cluster being thirteen times larger than a single bromine atom and despite aluminium being nothing like the lacrimatory poison-gas staple. Other combinations of aluminium can mimic noble gases, semiconductors, bone materials like calcium, or elements from pretty much any other region of the periodic table.

The clusters work like this. The atoms arrange themselves into a three-dimensional polyhedron, and each atom in it mimics a proton or neutron in a collective nucleus. The caveat is that electrons can flow around inside this soft nucleic blob, and the atoms share the electrons collectively. Scientists wryly call this state of matter “jellium.” Depending on the shape of the polyhedron and the number of corners and edges, the jellium will have more or fewer electrons to farm out and react with other atoms. If it has seven, it acts like bromine or a halogen. If four, it acts like silicon or a semiconductor. Sodium atoms can also become jellium and mimic other elements. And there’s no reason to think that still other elements cannot imitate other elements, or even all the elements imitate all the other elements—an utterly Borgesian mess. These discoveries are forcing scientists to construct parallel periodic tables to classify all the new species, tables that, like transparencies in an anatomy textbook, must be layered on top of the periodic skeleton.

Weird as jellium is, the clusters at least resemble normal atoms. Not so with the second way of adding depth to the periodic table. A quantum dot is a sort of holographic, virtual atom that nonetheless obeys the rules of quantum mechanics. Different elements can make quantum dots, but one of the best is indium. It’s a silvery metal, a relative of aluminium, and lives just on the borderland between metals and semiconductors.

Scientists start construction of a quantum dot by building a tiny Devils Tower, barely visible to the eye. Like geologic strata, this tower consists of layers—from the bottom up, there’s a semiconductor, a thin layer of an insulator (a ceramic), indium, a thicker layer of a ceramic, and a cap of metal on top. A positive charge is applied to the metal cap, which attracts electrons. They race upward until they reach the insulator, which they cannot flow through. However, if the insulator is thin enough, an electron—which at its fundamental level is just a wave—can pull some voodoo quantum mechanical stuff and “tunnel” through to the indium.

At this point, scientists snap off the voltage, trapping the orphan electron. Indium happens to be good at letting electrons flow around between atoms, but not so good that an electron disappears inside the layer. The electron sort of hovers instead, mobile but discrete, and if the indium layer is thin enough and narrow enough, the thousand or so indium atoms band together and act like one collective atom, all of them sharing the trapped electron. It’s a superorganism. Put two or more electrons in the quantum dot, and they’ll take on opposite spins inside the indium and separate in oversized orbitals and shells. It’s hard to overstate how weird this is, like getting the giant atoms of the Bose-Einstein condensate but without all the fuss of cooling things down to billionths of a degree above absolute zero. And it isn’t an idle exercise: the dots show enormous potential for next-generation “quantum computers,” because scientists can control, and therefore perform calculations with, individual electrons, a much faster and cleaner procedure than channeling billions of electrons through semiconductors in Jack Kilby’s fifty-year-old integrated circuits.

Nor will the periodic table be the same after quantum dots. Because the dots, also called pancake atoms, are so flat, the electron shells are different than usual. In fact, so far the pancake periodic table looks quite different than the periodic table we’re used to. It’s narrower, for one thing, since the octet rule doesn’t hold. Electrons fill up shells more quickly, and nonreactive noble gases are separated by fewer elements. That doesn’t stop other, more reactive quantum dots from sharing electrons and bonding with other nearby quantum dots to form… well, who knows what the hell they are. Unlike with superatoms, there aren’t any real-world elements that form tidy analogues to quantum-dot “elements.”

In the end, though, there’s little doubt that Seaborg’s table of rows and turrets, with the lanthanides and actinides like moats along the bottom, will dominate chemistry classes for generations to come. It’s a good combination of easy to make and easy to learn. But it’s a shame more textbook publishers don’t balance Seaborg’s table, which appears inside the front cover of every chemistry book, with a few of the more suggestive periodic table arrangements inside the back cover: 3D shapes that pop and buckle on the page and that bend far-distant elements near each other, sparking some link in the imagination when you finally see them side by side. I wish very much that I could donate $1,000 to some nonprofit group to support tinkering with wild new periodic tables based on whatever organizing principles people can imagine. The current periodic table has served us well so far, but reenvisioning and recreating it is important for humans (some of us, at least). Moreover, if aliens ever do descend, I want them to be impressed with our ingenuity. And maybe, just maybe, for them to see some shape they recognize among our collection.

Then again, maybe our good old boxy array of rows and turrets, and its marvelous, clean simplicity, will grab them. And maybe, despite all their alternative arrangements of elements, and despite all they know about superatoms and quantum dots, they’ll see something new in this table. Maybe as we explain how to read the table on all its different levels, they’ll whistle (or whatever) in real admiration—staggered at all we human beings have managed to pack into our periodic table of the elements.