Just three days after the start of its scientific operation, the Kepler Space Telescope got lucky. It spotted the transit of a planet inside the temperate zone of its star.

It would take another two-and-a-half years to certify the find. The characteristic dip in starlight needs to be seen at least three times to confirm the presence of a planet and measure its properties. The telescope had caught the first transit almost immediately, in May 2009. Another two had followed by December 2010. One year later, on 5 December 2011, the announcement was officially made: the first transiting planet within the temperate zone had been discovered. ‘Fortune,’ said William Borucki, who had led the discovery team from the NASA Ames Research Center in California, ‘smiled upon us with the detection of this planet.’

The new world was Kepler-22b. The planet orbits a Sun-like star 600 light years away in the constellation of Cygnus, the Swan. Sitting at a distance of 0.85au, Kepler-22b loops around its star every 290 days. Around our own Sun, this location would place Kepler-22b right on the edge of the early Venus boundary for the temperate zone. If the planet was also Earth-like, it would suggest that the world could have harboured liquid water for a brief period in its early history. However, Kepler-22 is a slightly smaller and cooler star than our Sun, making it 25 per cent less luminous. The weaker radiation pulls the temperate zone inwards to place Kepler-22b firmly within its conservative boundary. Did this make the planet our first look at another Earth?

The media were certain: ‘Earthlike planet found orbiting at right distance for life’, blared the headline on the National Geographic website. ‘Kepler-22b – the “new Earth”’, screamed the Telegraph. ‘Earth-like planet confirmed’, added the BBC.

However, as the planet’s measurements rolled in, it became clear that this world was keeping its secrets. The planet’s radius is 2.4 Earth radii, placing Kepler-22b in the mysterious super Earth category between the sizes of our rocky and gaseous worlds. It is too small and distant to produce a detectable wobble in the star’s position, making it impossible to measure the planet mass. This ruled out the option of calculating a bulk density to reveal if the planet was probably terrestrial, or a lot of hot gas.

Radial velocity data would also have allowed the eccentricity of the planet’s orbit to be estimated. A transit observation sees only one part of the orbit as the planet passes across the star’s surface, while the radial stellar wobble maps the planet’s full circle. With only the transit detected, the planet could be on a bent path that spends just a tiny fraction of its year inside the temperate zone.

Based on the rule of thumb discussed in Chapter 6, it seems unlikely that a planet larger than 1.5 Earth radii would be rocky. However, Kepler-22b’s intermediate size might make it a water world. Such a planet would have a rocky core entirely engulfed by an ocean thousands of kilometres thick. With the sought-after temperate zone based on the concept of surface water, a global sea might seem a positive feature for life. The problem is that the lack of land throttles the carbon-silicate cycle, as we will see in the next chapter. Life is not necessarily precluded on such a world, but it would certainly be different from that on Earth. Kepler-22b may have been a first discovery, but it is not a second Earth.

In 2010, the most exciting place in the Galaxy was the neighbourhood of the red dwarf star Gliese 581. The small star has only a third of our Sun’s mass and sits 20 light years away in the constellation of Libra, the Weighing Scales. Around its moderate light were thought to be six planets, all between the mass of the Earth and Neptune. It was our Solar System in miniature, and intriguingly, three of those worlds looked potentially habitable.

Red dwarf stars with masses of between a tenth to half that of our Sun are exciting prospects for detecting small planets. For a start, these dim stellar furnaces are numerous and form about three-quarters of the stars in our Galactic neighbourhood. Their small size decreases the ratio between the planet and star, making both the transit light dip and radial velocity wobble more pronounced and easier to detect. Finally, their low luminosity places the temperate zone much closer to the star. The proximity boosts the chances of a planet within the temperate zone transiting across the stellar surface, since the orbit would have to be highly inclined to miss the star’s face entirely. The short year in the closer orbit also leads to frequent transits, giving multiple chances to spot the planet. The net result is that rocky worlds in the temperate zone are easiest to find around red dwarfs.

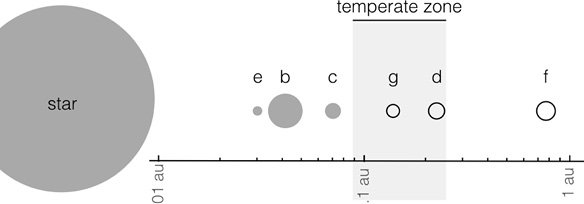

Between 2005 and 2010, six planets were discovered orbiting Gliese 581 using the radial velocity technique. The first to be announced was predictably the weightiest and orbited close to the star; Gliese 581b was a Neptune-sized world at almost 16 Earth masses, with an orbit time of a little over five days. Next to be discovered were two super Earths, Gliese 581c and Gliese 581d. This pair had masses of 5.5–6 Earths, and orbited in 13 and 67 days. Then a planet only twice the mass of the Earth was found; Gliese 581e circled the star closer than its three planetary siblings in just 3.1 days. Finally, two more distant super Earths were detected. Gliese 581f was 7 Earth masses and had an orbital time of 433 days, while Gliese 581g was 4 Earth masses with an orbit that lasted just over a month.

With the exception of the outermost super Earth, Gliese 581f, all the planets orbited far closer to their star than any planet in our Solar System. But the red dwarf’s dim light indicated that these were not scorched worlds. Instead of a temperate zone around 1au, the location where liquid water could persist on an Earth-like planet lay at 0.09–0.23au, corresponding to circular orbits lasting 18–72 days. This placed planets Gliese 581d and Gliese 581g inside the temperate zone, while Gliese 581c sat tantalisingly just beyond the inner edge. Could one of these three worlds be Earth-like enough to be awash with an ocean?

Figure 21 Gliese 581 is a red dwarf star that was thought to be orbited by six planets, two inside the temperate zone. However, later observations questioned the existence of planets d, f and g.

Upon its discovery in 2007, Gliese 581c was the lowest-mass exoplanet ever found. Despite orbiting slightly inside the inner edge of the temperate zone, there was an optimistic proposal that a covering of reflective clouds might be able to keep the planet cool. Reflecting 50 per cent of the star’s radiation at the location of Gliese 581c would allow an otherwise Earth-like planet to have an average surface temperature of 20°C (68°F). While the Earth reflects only about 30 per cent of sunlight, Venus’s clouds bounce back 64 per cent of the incident rays. Fifty per cent reflection therefore seemed possible, and Gliese 581c was declared in its discovery paper the ‘most Earth-like of all known exoplanets’. It was a bold proclamation, but could a few clouds truly make Gliese 581c a serious contender for a habitable world? Unfortunately, the odds are stacked against a cooler climate.

The first problem is the planet’s location. Even adjusting for the red dwarf’s weak heat, Gliese 581c sits closer to its star than Venus does to our Sun. Moreover, while Venus’s clouds may be reflective, they also indicate the suffocating atmosphere of a runaway greenhouse environment.

This risk is compounded by the planet’s mass. If Gliese 581c has an Earth-like composition, its 5.5 Earth masses would correspond with 1.5 Earth radii; a size right on the brink between a terrestrial planet and a gaseous mini Neptune. Even if the planet were rocky, the extra mass would boost the gravity to draw in a thick atmosphere. This would efficiently trap heat to rocket the surface temperature beyond that expected even at the edge of the temperate zone. The stronger gravity also risks the primitive atmosphere of hydrogen and helium gases being retained to produce a dry and unusable mess.

Just in case a brief holiday still sounded tempting, the proximity of Gliese 581c to its star indicates that the planet risks tidal lock. Like the CoRoT-7b lava world, a tidally locked Gliese 581c would be a split world of day and night with one face permanently turned towards the star’s inferno. Such divided worlds can struggle to distribute heat around the globe. This does not necessarily render a world barren, but such a temperature dichotomy is unlikely to aid life. The combination of these factors is enough to take Gliese 581c out of serious consideration for habitability.

In contrast to this, the main issue with the habitability of planets Gliese 581d and Gliese 581g is that they may not exist. Two weeks after the discovery of Gliese 581f and Gliese 581g was announced, their existence was called into question at a meeting of the International Astronomical Union in Italy. Fresh observations had confirmed the presence of planets b, c, d and e, but failed to find definite signatures for planets f and g. The difficulty was that teasing apart the wobbling motion of the star to pick out the rhythmic tugs from multiple orbiting planets is immensely tricky. This is especially true for red dwarfs, which are intrinsically faint and typically rambunctious stars. Even slight fluctuations on the star’s fiery surface can lead to a false find.

The non-existence of Gliese 581f was accepted, but researchers haggled over Gliese 581g. Further analysis failed to reach any conclusion: was this planet real or just a ghost? If the planet existed, it sat squarely in the temperate zone. Moreover, with a mass just three times that of Earth, Gliese 581g was far more likely to be rocky than Gliese 581c. With the chance of habitability being waved like a carrot on a stick, everyone wanted this planet to exist.

In 2014, these hopes were dashed. Further observations of Gliese 581 had recorded unusual magnetic activity on the star’s surface. The magnetised patch was similar to a sunspot and was interfering with the surrounding flow of stellar material. As the star rotated, the spot appeared as a periodic wobble that looked strongly like the influence of a planet. When this effect was removed from the data, Gliese 581g vanished. What was worse, the correction also erased Gliese 581d. This second casualty had been measured to have an orbit taking twice the time of Gliese 581g and turned out to be linked with the same anomaly.

While the observations of Gliese 581 remain debated, the prospect of not existing is a blow to the real estate of Gliese 581d and g. Hunting low-mass planets was proving to be an extremely difficult game.

There are two problems with finding a transiting Earth-sized planet in the temperate zone. The first is that a planet and star analogue to our own has only a 0.1 per cent chance of transiting. From most viewing angles, the small and distant Earth does not cross the Sun’s face. The second issue is that the decrease in light as the planet crosses the star is just one part in 10,000. ‘Imagine the tallest hotel in New York City, and everybody has their light on,’ Natalie Batalha, project scientist for the Kepler Space Telescope, stated. ‘And one person in his hotel lowers the blinds by 2cm. That’s the change in brightness we’re trying to detect from the transit of a planet as small as Earth passing a star the size of our Sun.’

Yet on 18 April 2014, the Kepler Space Telescope science team announced that it had done it. Kepler-186 was a red dwarf about 500 light years away in the constellation of Cygnus. With half the mass of our Sun, the star’s dim light pulled the temperate zone inwards to sit at 0.22–0.4au, almost entirely within Mercury’s 0.4au orbit in our Solar System. The planet was Kepler-186f, which sat on the outer edge of the conservative temperate zone with an orbital time of 130 days. It had a radius of 1.11 Earths, tantalisingly close dimensions to our own planet. At such a small size, Kepler-186f was unlikely to be anything other than rocky.

Like the Earth, Kepler-186f is part of a system of planets. Four other worlds had previously been discovered, all with sizes smaller than 1.5 Earth radii. These four siblings orbited closer to the star than Kepler-186f, taking 4–22 days to loop the red dwarf. While also small enough to be rocky, the planets sat inside the inner edge of the temperate zone, and were liable to be too hot to support liquid water even if they mirrored the surface conditions on Earth. Unlike in our own system, the most likely candidate for habitability was the outermost planet. Could we now finally say we had found an Earth twin?

The only true way to ascertain whether Kepler-186f is Earth-like would be by exploring its surface. While we cannot yet send spacecraft between star systems, clues could be gleaned from the planet’s atmosphere. As we saw for 55 Cancri e, the light passing through the gases surrounding a planet transiting across its star can reveal information about surface conditions. For instance, the Earth’s atmosphere is packed with oxygen and methane from the teeming life on our ground. Unfortunately, Kepler-186f is 500 light years away, rendering it too distant and small for an atmospheric study. The best we can do is speculate.

In fact, the position of Kepler-186f raises a couple of interesting problems. The first is a ubiquitous issue with the temperate zone around red dwarfs. Situated close to the star, planets in this potentially comfortable region travel on much shorter orbits than the Earth. Forming at such a location would be a rapid process. Able to whip around the star almost three times as often as the Earth, collisions between planetesimals would be frequent and material would quickly accumulate. This initially sounds very positive; swift planet formation would allow a longer time in the temperate zone to develop a life-supporting environment. But there is a price. The very young red dwarf is a hot beast. Before the start of nuclear fusion, proto-red dwarf stars are surprisingly luminous. Unlike larger Sun-sized stars, a forming red dwarf can be 100 times brighter than its normal dim value once it begins to burn hydrogen into helium. If a planet has formed during this early phase, any surface water could be evaporated away before the star cools. The surface temperature on Kepler-186f might allow liquid water now, but possibly there is none left on the planet to form a sea.

An associated problem with forming close to the star is the speed of the planetesimals and embryos. These rocky bodies move rapidly on close-in orbits. The final planet-formation stage may end up being dominated by high-velocity collisions, capable of stripping away atmosphere and water from a young world.

A second issue is that Kepler-186f appears to be the outermost planet around its star. For the Earth, this is of course not true. Beyond our orbit sits Mars, then the neighbourhood of the gas giants. The presence of Jupiter has been particularly important in our evolution, since its powerful gravity is thought to have scattered ice-rich planetesimals inwards to deliver our oceans. Admittedly, the gas giant games of gravitational pinball also present risks to a young planet, but a lack of water would definitely preclude Earth-like life. Without such an outer kickballer, would Kepler-186f be a dry world?

These seem like significant problems for Kepler-186f. Yet, the layout of the planetary system could indicate an alternative and more promising history. This system has five worlds that all sit very close to the star. For these to form on their current orbits, the original protoplanetary disc would have needed to contain more than 10 times the Earth’s mass, with most of this bulk within 0.4au of the star. Such a shape is not commonly observed in discs around young stars. It is therefore more likely that the Kepler-186 planets formed further out and migrated inwards. This circumnavigates the above concerns: forming in the colder outer reaches of the disc would allow ice to solidify with the planet and form water-rich worlds. These could then migrate inwards from the gas drag after the star had outgrown its fiery protostar phase. The outer location of Kepler-186f would then prove an advantage, since it may be distant enough to avoid tidal lock. With a regular rotation that allows the planet to be evenly heated, surface water could possibly be maintained.

And yet… migration does not entirely bypass all problems. Kepler-186f is still close enough to the star to feel the full frontal of space weather from the star’s stellar wind. Without a strong magnetic field, the planet could find itself stripped of its air. Whether the planet is able to generate a magnetic field will be down to its geology. But while Kepler-186f is a likely size to be rocky, there is no way of telling what types of rock it contains.

As the varied scenarios for the composition of 55 Cancri e testify, rocky does not necessarily mean Earth-y. Even a mix of iron, silicate and ice can lead to very different planet masses. A pure iron Earth-sized world would have a mass of nearly 4 Earths, while one dominated by ice might only weigh in at 0.32 Earths. If Kepler-186f did have the same mix of iron and silicates as our planet, its mass would be 1.44 Earths. So while the planet’s size might be only 10 per cent larger than the Earth, its mass could be between a third to one-and-a-half times our bulk. These variations would produce strong differences in the planet’s gravity and internal pressure. The resulting rock composites may not have the right mobility to generate a magnetic field. The difference in gravity will also affect the atmosphere gases that can be drawn in and held by the planet.

But yet again, we can argue this from the opposite direction. Models of the effect of stellar flares and wind on a planet without a magnetic field around a red dwarf have suggested that the damage may be restricted to just the upper atmosphere. This could leave conditions on the ground unharmed by the rambunctious star. Until we probe the atmospheres of more small planets beyond our Solar System, the effect of non-Earth environments involves a lot of guessing.

It is also worthy of note that life on Earth can be found in the most unappetising places. So-called extremophiles are creatures that can survive (as their name suggests) in extreme levels of hot and cold temperatures, acidity, pressure and dryness. One of the most resilient examples are the tardigrades, or water bears; eight-legged micro-animals that can successfully hibernate in temperatures of -256–+151°C (-428–+304°F), pressures higher than those found in the ocean trenches, and exposure to radiation levels hundreds of times higher than would kill a human. However, whether life could begin in such extreme conditions or can simply evolve to adapt is a big unknown.

As for Kepler-186f, it is possible that it may be habitable and host life. We can say that its location and size do not rule this out, but we equally cannot say that these factors guarantee hospitable conditions. Orbiting a red dwarf, any life on Kepler-186f would be very different from our own. At high noon, the close star would look a third larger in the sky than our Sun, but its brightness would match the Sun on Earth an hour before sunset. This dimly lit distant world could perhaps be a distant Earth cousin, but it can never be a twin.

By November 2016, 93 planets had been confirmed orbiting entirely within the temperate zone of their star, with 217 planets found with at least part of their orbit inside this region. Of these, five planets had radii below 1.5 Earths and were likely to be rocky, with Kepler-186f being the smallest and closest in size to the Earth.

What does this tell us about the rarity of worlds that could be potentially Earth-like? While the number of small planets found is low, the total number of new worlds discovered is huge. It is huge enough to do some statistics.

Based on the 2,300 planets that had been discovered by the Kepler Space Telescope by 2013, it was estimated that one in six stars had a planet within 80–125 per cent of the size of the Earth. Around the Milky Way’s 100 billion stars, this would mean that 17 billion Earth-sized worlds are out there. The calculation used for this excitingly big number had included an estimate for the number of planets that might have been missed in observations and the chances of a false detection. However, it only applied to planet orbits that were shorter than 85 days. For longer orbits, the number of discovered planets was still too low for a meaningful calculation. 1 With such short years, most of these 17 billion worlds would be too hot to be inside the temperate zone.

To combat this problem, a second estimate was made for planets orbiting red dwarfs. Smaller worlds around these stars are easier to observe, especially in the temperate zone where the closely orbiting planet would transit about five times in one Earth year. From an examination of nearly 4,000 dwarf stars, just under 40 per cent have a planet that is likely to be rocky; 15 per cent of these were also within the temperate zone of the star. This implied that there was most probably an Earth-sized planet in the temperate zone within 10 light years of Earth. It was an intriguing thought. Where was our nearest rocky planet?

In the summer of 2016, it looked as though we might have the answer. A planet had been discovered around Proxima Centauri, the dim third wheel that formed the triple star system with the Alpha Centauri binary.

Of the three stars, Proxima Centauri sits nearest to the Earth. Its distance is 4.22 light years, compared with the 4.3 light years to Alpha Centauri. The distance between the binary and third star is a rather considerable 13,000au and casts doubt over whether the trio are truly held together, or if Proxima Centauri is just passing through the system. Whichever turns out to be the case, Proxima Centauri is our nearest neighbour, making any planet the star hosts the closest possible exoplanet to us. The discovery of Proxima Centauri-b was therefore justifiably exciting.

The planet had been found using the radial velocity technique, providing a minimum mass of 1.3 Earths. With no observed transit, the orientation of the planet’s orbit remained unknown, leaving the exact mass a mystery. If we were seeing the orbit of Proxima Centauri-b at an angle larger than 15 degrees, the planet mass would be in the mini Neptune regime. That said, it is still more likely that our nearest neighbour has a mass commensurate with a rocky planet.

The planet orbits Proxima Centauri at just 0.05au, giving it a year of 11.2 days. This might suggest that the planet is a baked lava world, but Proxima Centauri is a dim star even for a red dwarf. With just over 10 per cent of the Sun’s mass, the star’s radiation is so weak that Proxima Centauri-b sits within its temperate zone.

Of course, the present weak flow of energy from the star does not avoid the problems faced by Kepler-186f in orbiting a red dwarf. Proxima Centauri is a particularly active star even today, suffering from mega flares that periodically bathe its closely orbiting planet in radiation levels hundreds of times higher than those found on Earth. Unless Proxima Centauri-b is protected by a strong magnetic field, its atmosphere may well be stripped.

The loss of atmosphere would be particularly bad since the planet’s incredibly close orbit indicates that it is almost certainly tidally locked. Without an atmosphere capable of redistributing heat, the planet will be split into roasting and freezing hemispheres, corresponding to perpetual day and night.

The star’s strong activity also comes with the risk that this planet may be a false detection. With a lot of action and change on the star’s surface, picking out the tiny wobble from an exoplanet becomes an even greater challenge.

In spite of these concerns, the proximity of Proxima Centauri-b makes this find one of the most exciting exoplanet discoveries. If future observations are able to examine the planet’s atmosphere, we may get a peek at what surface conditions are like around red dwarfs. The easiest way to achieve this would be if the planet were found to transit the star. Unseen so far, the chances are not high but Proxima Centauri is being watched carefully for signs of a periodic dimming. A second option would be a direct image of the planet. Direct imaging is always a challenging prospect, especially for such a small world. However, Proxima Centauri-b is our nearest possible exoplanet. As new space telescopes such as the Hubble Space Telescope’s successor the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) and the Wide Field Infrared Survey Telescope (WFIRST) come on line, together with the ground-based Extremely Large Telescope (ELT) and Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT), 2 this planet will be one to watch.

As our nearest exoplanet, how long would it take to visit Proxima Centauri-b? While 4 light years sounds tiny compared with the 500 light-year distance of Kepler-186f, a light year is a blisteringly long distance. The furthest humans have ever travelled is a loop around the Moon; a teeny 0.00000004 light-year distance. Our furthest and fastest travelling spacecraft is Voyager 1, which would still take 75,000 years to reach Proxima Centauri if it were orientated in the right direction.

Other ideas have been floated for attempting high-speed travel of miniature probes, but these are no more than drawing-board sketches at this stage. For the moment, the district of our nearest stars must be studied through a telescope’s eye.

Notes

1. Note that this does not mean that there are fewer planets further from their star, only that these are trickier to detect.

2. Let’s take a moment to appreciate the descriptive, yet unimaginative, naming of astronomical instruments.