For planet-formation theories, the discovery of 51 Pegasi b was rather unfortunate.

Its announcement in 1995 as the first planet found orbiting a star like our own Sun threw open the door to a new era of planet discoveries. It also blasted a hole in the theory of planet formation.

In truth, 51 Pegasi b was not the first exoplanet to be discovered. Around five years earlier, a planet had been found orbiting the remnant of a dead star known as a pulsar. However, since a pulsar is very unlike our Sun, there were any number of excuses for why such a planetary system should be different from our own. For 51 Pegasi b, the excuses were harder to find. This was a planet orbiting a Sun-like star but in completely the wrong place.

51 Pegasi b is a gas giant planet. It has a minimum mass approximately half that of Jupiter, making it 150 times more massive than the Earth. However, it sits so close to its star that one year on 51 Pegasi b is over in a blisteringly short 4.2 days. Even our Sun’s closest planet, Mercury, takes 88 days to complete an orbit, while our Jupiter takes a full 12 Earth years to loop the Sun.

Such differences from our own Solar System were intriguing, but they resulted in a conundrum: both the major theories for gas giant planet formation required the planet to form far away from the star.

To gather enough mass to capture the colossal atmosphere of a gas giant, the planet must form beyond the ice line so that it can bulk up on frozen ices. It also needs to be far away from the star so that its gravity can dominate over a wide region and lure in a large reservoir of planetesimals (in the language of Chapter 2, its Hill radius needs to be big). For formation via disc instability, the planet needs to be even further out than the ice line, 51 Pegasi b was so close to its sun, that it should not have been able to become a gas giant. In fact, the intense heat at such a location should have prevented much solid mass from forming there at all.

Just to add insult to injury, 51 Pegasi b did not prove to be an isolated anomaly. As detections of exoplanets began to mount up, so did the number of gas giants that snuggled up to their stars.

It was true that current observational methods favoured finding such hot Jupiters over planets in systems that might resemble our own. Very massive and close to their star, these huge worlds caused the maximum wobble in the star’s radial velocity. Their swift orbits also repeated the signal of their presence every few days. In short, hot Jupiters were the bawling babies of the exoplanet field. Nevertheless, there was no denying their presence. Later statistics would estimate that around 1 per cent of stars hosted a hot Jupiter. You could not have a planet formation theory without them.

There was only one logical explanation for their existence; if such a planet could not be formed where it sat, then it must have been born further away and moved there.

The concept of a planet changing its orbit was actually not a new one. The idea had been postulated as early as the 1980s, but had originally been dismissed. The problem had not been how to start a planet moving, but how to stop it.

Planetary migration occurs when the gravity of the growing planet begins to pull strongly on the surrounding gas in the protoplanetary disc. The gas resists, with the swifter gas closer to the star trying to pull the planet forwards, while the slower gas further out in the disc drags back on it. Since the planet does not feel the gas pressure, the directly surrounding gas is also part of the slower moving component. This makes the backward drag the stronger force, and the planet loses speed and moves inwards towards the star.

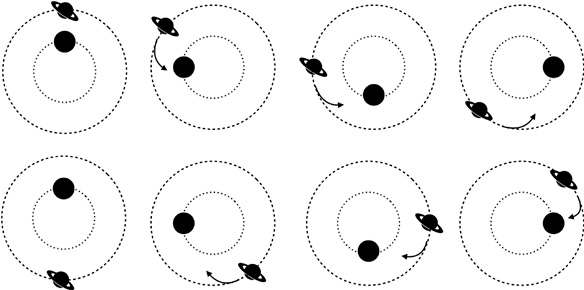

Figure 7 A planet migrating through the protoplanetary disc. Gas closer to the star moves faster than the planet and tries to pull it forwards. Gas further out is moving slower and drags it back. Typically, the drag wins and the planet slows and moves towards the star.

We touched on this motion when exploring gas giant formation in Chapter 3. Trawling through the protoplanetary disc was an effective way to grow by gathering planetesimals. Unfortunately, it can end very badly for the planet.

Predictions for the planet’s inward migration suggest a merciless rate. Within 100,000 years, a gas giant embryo at Jupiter’s current position could meet a fiery death as it crashed into the star. This is far shorter than the time taken for the disc to evaporate and release the planet from the drag of the gas. Since a planet’s gravity can be sufficient to start migration once it reaches the size of Mars, it is unclear how it is possible for planets to form at all.

This is the second time on the planet factory production line that gas drag has nearly cast would-be new worlds into the star. The first occasion was the drag on small planetesimals, which feel a headwind in the slower-moving gas. As the planetesimals grow into embryos, this drag can no longer affect their more massive body. But as the mass increases further to form small planets, the planet’s gravity pulls on the gas to create dangerously strong drag forces once again.

The obvious existence of our Solar System was the reason why the idea of migration was initially dismissed. Yet, the discovery of hot Jupiters gave reason to pause. Was it possible for a planet to migrate, but stop before it hit the star?

While the gas drag forces the planet to change orbit, the planet’s pull does the same to the gas. The slower-moving gas is accelerated and forced to move outwards, while the faster-moving gas is slowed and moves inwards. This pushes the gas away from the planet. When the planet is small, fresh gas is able to pour in to replace the displaced material. However, when the planet’s gravity becomes strong enough, it pushes all gas away to open a gap in the disc.

It is this process that completed gas giant formation described in Chapter 3; the young gas giant grows rapidly as it migrates into fresh planetesimal reservoirs. As its mass becomes great enough for its gravity to open a gap, the planet is left in a low-density hole and atmosphere growth finally stalls.

With the gas pushed away from the planet, its countering drag might entirely disappear. However, the disc gas is also drifting inwards as it is accreted by the star. This causes the gap to try and refill from the outside edge, providing a renewed supply of gas to drag back on the planet before it is pushed away. The result is still an inward push, but substantially weaker than before. If the planet can move slowly enough, the gas disc will evaporate and leave the planet free of its force.

Planetary movement before the gap opens is known as Type I migration, and progresses to Type II once the planet carves a hole. However, due to the speed of Type I migration, planets run the risk of never making it to the sedate Type II mode.

Exactly how Type I migration is stopped remains an open question. One possibility is that the inward-moving planet acts as a snow shovel, piling up gas just inside its orbit. This increases the fast inner gas that wants to pull the planet forwards, allowing it to counter the slower gas’s drag. Sudden bumps and changes in the gas, such as those at the ice line, may also flip the strength of the inward and outward gas forces to act as planet traps and halt this mode of migration. In short, anything that can affect the flow of the gas in a region of the disc may also change the rate of Type I migration.

If hot Jupiters reached their current location via migration, then migration potentially plays a tight game with planet formation. Assuming the hot Jupiters we observe stopped their inward march when the gas disc evaporated, their proximity to the star suggests that they got very lucky. Alternatively, the planets may stop at the disc’s inner edge, beyond which the star has evaporated or accreted all the material.

However, while migration offers a solution to the hot Jupiters, it messes up the Solar System.

The problem with Mars

If migration does indeed explain the hot Jupiters, we are left with an obvious question: how did the planets in our Solar System avoid the same fate?

Whether the terrestrial planets were hauled about by migration is a debated topic. Forming more slowly, the Earth and its neighbours may have stayed below the mass to drive fast migration until the gas has evaporated away. Alternatively, our rocky worlds may have been held in position by one of the planet traps mentioned earlier.

The fate of the gas giants is less easily waved away. The fast formation needed to ensure their huge atmospheres forces the planets to be susceptible to both Type I and Type II migration. Even if Type I migration could be slowed or halted, their huge mass would have opened the gas gap to begin Type II migration and sent the planet onwards towards the Sun.

We have also seen hints that at least a small amount of orbital movement did shape our planets. Gas giants can more easily gain mass if they migrate through the disc. The current positions of Uranus, Neptune and the Kuiper belt may also not have contained enough material for these objects to form, suggesting that they may have shuffled over from a denser region. But if migration did occur, what stopped Jupiter from crashing through the inner Solar System and destroying the Earth?

In fact, Jupiter may have tried to do exactly that. The clue to this dangerous past lies with Mars. Despite being named after the Roman mythological god of war, Mars is small and weedy. It is so diminutive that its size has presented a problem for planet-formation theories.

As we step outwards through the inner Solar System to Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars, the pull from the Sun’s gravity weakens. This allows the gravitational influence of the planet (its Hill radius) to extend and attract rocks from a wider area as it forms. The result of this progressively larger feeding zone ought to be steadily bigger planets. We should therefore find that planet masses increase until we approach Jupiter, whose huge gravity starts to mess with the formation process to create the asteroid belt.

This logic holds well until we pass the Earth, but rather than Mars being a super-sized version of our own planet, it has only a tenth of our mass. Even allowing for the protoplanetary disc to gradually drop in density between the Sun and the ice line, we would expect a Mars of between 0.5 and 1 Earth mass. Moreover, the asteroid belt should also be chunkier and populated with a collection of Mars-sized embryos. Instead, the largest object in the asteroid belt is Ceres, which is around a hundred times smaller than Mars.

We can fix this conundrum if the density of planetesimals was abruptly depleted at around the Earth’s current position. Deprived of planet-building blocks, both Mars and the asteroid belt are then forced to remain small. But what could have happened to drain Mars’s neighbourhood of rocky supplies?

When searching for missing mass, an obvious suspect is the most mammoth planet in the Solar System: Jupiter. Could Jupiter have had a wild history that entailed the planet travelling into the inner Solar System, gathering or scattering planetesimals, then migrating backwards to its current location?

This idea became known as the Grand Tack model, named after the sailing manoeuvre to reverse the direction of a boat. The scenario begins when Jupiter is forming in the protoplanetary disc. As the planet’s gravity starts to pull more strongly on the surrounding gas, the young Jupiter begins to migrate towards the Sun. The change in orbit allows the growing planet to quickly gather more planetesimals, eventually gaining enough mass to open a gap in the gas. This slows Jupiter’s motion to Type II migration, but the planet keeps shrinking its orbit. Jupiter’s march also shepherded planetesimals in its path inwards, while scattering others outwards. The planet might have ended up as a hot Jupiter, were it not for the appearance of Saturn.

Further out in the protoplanetary disc, Saturn formed more slowly than its big sibling. While Saturn is the second-largest planet in our Solar System, it has less than a third of the mass of Jupiter. Due to its lighter weight, Saturn opened only a partial gap in the gas, allowing the planet to migrate swiftly and gain on Jupiter’s inward march.

As the planets approach, their years become closer in length. Eventually, Saturn orbits the Sun exactly twice in the time it takes Jupiter to orbit three times. This ratio is known as a 2:3 resonance, and it is very difficult to break.

Figure 8 A 2:1 orbital resonance. The inner planet pulls the outer planet forwards for the first half of its orbit and backwards for the second half. The net force on the planets due to each other is zero, making a stable set-up that is difficult to change.

Exactly why resonances are stable can be seen by picturing a 1:2 resonance between the two planets. Saturn would then orbit the Sun twice in the time it takes Jupiter to orbit once. For the first half of its orbit, Saturn is behind Jupiter and the larger planet’s gravity pulls Saturn forwards. For the second half of its orbit, Saturn is in front of Jupiter and being pulled back. Overall, these forces cancel out each other, and neither planet feels an extra tug during its circles about the Sun. However, if the two planets move slightly closer, the balance breaks. There is now an overall pull on Saturn that encourages the planet to gain speed and move outwards to the resonance position. This same balance applies to planets in different orbital resonance, such as 2:3 or 1:4.

Due to this stability, resonant orbits are common in planetary systems. Neptune orbits the Sun three times for every one orbit of Pluto, while Jupiter’s moons Ganymede, Europa and Io are all in resonant orbits around the giant planet in a 1:2:4 ratio.

When Jupiter and Saturn reach their 2:3 resonance, they are close enough that the gap around Jupiter and partial gap around Saturn overlap. Instead of being tugged by gas on both sides, Jupiter now only feels the pull of the faster inward gas, while Saturn feels the drag of the outer gas. This causes Saturn to want to migrate inwards, while Jupiter now wants to migrate outwards. Since the resonant orbits push the planets apart if they try to move past one another, it comes down to a battle of strength. With the stronger gravity, the forces around Jupiter win. Both planets migrate outwards, leaving a disc depleted of planetesimals right around where Mars would later form.

As they returned to the outer Solar System, the planet pair scattered the planetesimals that had moved into their vacated spots. Forming in this region beyond the ice line, the displaced rocks were packed with ice. They were sent flying in all directions, with a population ending in the asteroid belt to become the water-rich C-type asteroids. Others flew further, feasibly striking the newly formed Earth and delivering its oceans.

The tack of Jupiter and Saturn also prevented Uranus and Neptune from drifting towards the Sun. As the smaller gas giants form and begin to migrate, they also risk becoming locked in resonant orbits. This makes it very difficult for the planets to jump past their big siblings and continue towards the Sun.

The Grand Tack model was proposed in 2011 in the journal Nature, led by astronomers Kevin Walsh and Alessandro Morbidelli. The day after seeing the success of the Grand Tack model in replicating both Mars’s small size and the asteroids, Morbidelli strode into Walsh’s office and declared that he had shook his finger at Jupiter the night before and told the giant planet, ‘Jupiter! I know what you did!’

When Jupiter and Saturn near their present positions, the protoplanetary gas disc evaporates. The planets are finally free of the gas drag for good. However, to finish our Solar System’s tale, we need one last reshuffle.

Exactly how this mayhem goes down is still debated. There are two main hypotheses: the Nice Model and (with a naming choice reminiscent of Hollywood blockbusters) the Nice Model II. In both scenarios, chaos erupts due to the planet factory leftovers.

Just beyond the giant gas planets lay a sea of remaining planetesimals. These rocky remains had skirted the edge of the planet orbits and avoided being absorbed or booted out of the Solar System. In the Nice Model, the lifting of the gas drag allowed the coercing pull of the giant planets’ gravities to be a dominant force that causes these rocks to dribble inwards.

The strong gravity of the gas giants could rapidly accelerate nearby planetesimals. Moving too fast to be captured by the planet, these scattered out of the neighbourhood. The result of ejecting a planetesimal was a reverse kick on the planet like the recoil from the firing of a gun. Being very massive, this backlash did not strongly affect the gas giant. However, the impact could build up through multiple scatterings and eventually make the planet change its orbit. This new motion is known as planetesimal-driven migration.

Due to the difficulties with forming Uranus and Neptune in their current positions, it is suspected that the planets were much closer together when the gas disc dispersed. Jupiter’s position could remain around 5au, but Neptune would be around 15au, rather than 30au, with Saturn and Uranus in between. The scattering of the planetesimals separated this close configuration, causing the planets to move apart.

As their orbits diverged, Jupiter and Saturn reached a second orbital resonance. However, this time the resonance did not lock the planets together. While approaching planets can force one another to maintain the resonant orbits, planets that are moving apart cannot stop their motion. Instead, passing the resonance produced a gravitational jolt that bent the orbits of Jupiter and Saturn into a more elliptical path.

These bent orbits pushed the two largest planet towards Uranus and Neptune. The two smaller giants were scattered outwards, barging into the outer reservoir of planetesimals. This resulted in a truly massive scattering, with the smaller rocks shooting all over the Solar System. Some of these rocks were pushed outwards to form the Kuiper belt, others bombarded the inner planets, and a population left the planet-populated region altogether to find a home in the Oort cloud.

The Nice Model was named after the French town where the idea was formed. The Nice Model II kept the name and proposed a similar scenario between the outer planetesimal rubble and the gas giants. In this version, the planetesimals did not have to dribble inwards and be scattered. Instead, the gravitational pull of the whole rocky debris field was enough to break the resonances between the giant planets and start the resulting chaos.

Dramatic as these models sound, there is evidence for such a giant scattering event occurring on the surface of our Moon. Examination of the lunar craters shows a spike in activity around 700 million years ago.

With the planetesimals scattered away, the orbits of the giant planets finally settle. Uranus and Neptune now sit at their current more distant location with the remains of the planetesimal sea pushed out by Neptune’s motion to form the Kuiper belt.

The planet with the density of polystyrene

Migration provided a fast and efficient train line to slide Jupiter-sized planets close to their star. With the Solar System’s formation now consistent with migration, this seemed the solution to this strange class of planet. Yet, as more planets were discovered, a population of hot Jupiters appeared that did not quite fit the gas migration picture.

At first glance, WASP-17b appeared to be a regular hot Jupiter. It was named for being the 17th discovery in a ground-based survey to hunt for transiting planets; 1 a project known as the Wide Angle Search for Planets, to give the insect-inspired acronym ‘WASP’.

The planet was found circling a star in the constellation of Scorpius around 1,300 light years from Earth. With one orbit taking just 3.7 days and a radius of 1.5–2 times that of Jupiter, this was clearly another hot gaseous world.

However, closer inspection of WASP-17b revealed two surprises: first, the planet was immensely bloated. Despite being a super-Jupiter in size, radial velocity measurements revealed a mass equivalent to only 1.6 Saturns. This small mass but extreme size gave the planet an average density of 6–14 per cent of Jupiter and a few per cent that of Earth. It was a value so low that UK astrophysicist Coel Hellier remarked that the planet was only ‘as dense as expanded polystyrene’.

The second rather surprising discovery was that it was orbiting backwards.

In our Solar System, the planets circle the Sun in the same direction as the Sun’s own spin. We call such orbits prograde and they are the expected situation since the Sun, protoplanetary disc and planets are formed from the same core of rotating gas.

With everything turning the same way, migration should not cause the planet’s orbit to reverse. Like being pulled into the centre of a whirlpool, a hot Jupiter that has been dragged inwards should still be orbiting in the same direction, albeit much closer to the star. Finding WASP-17b orbiting in the opposite direction to its star’s spin therefore did not fit with the idea of gas-driven migration.

WASP-17b’s opposing orbit is known as retrograde. While the Solar System’s planets do not display such contrariness, the same it not true of the comets. Halley’s Comet orbits the Sun in the reverse direction due to being given a hard kick by a planet that flipped over its orbit. Such a kick is a possible explanation for WASP-17b. While no other planets have been found orbiting its star, it is possible that it has a distant hidden sibling. The other possibility is that the sibling belongs to the star.

Roughly a third to half the stars in our Galaxy are binaries, with two (or sometimes more) stars orbiting one another. How strongly the gravitational pull from a stellar sibling can affect the forming planets depends heavily on its distance. WASP-17 does not have an obvious stellar companion, but it is possible that a nearby star was able to mess with its planet.

The method for stars interfering with each other’s planetary children was described independently by Soviet scientist Michail Lidov in 1961, and Japanese astronomer Yoshihide Kozai in 1962. At the time, the strangeness of exoplanet orbits was not known – Lidov was instead examining the orbits of moons and artificial satellites, while Kozai was looking at asteroids.

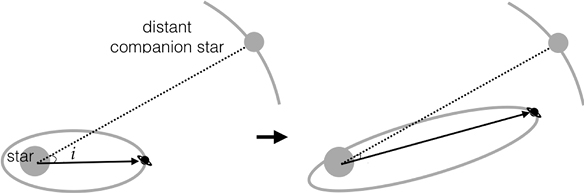

Figure 9 An edge-on image showing the Kozai-Lidov mechanism. A companion star (or more massive planet) can change the orbit of a planet by decreasing the angle (i) between the planet’s orbit and companion’s orbit and increasing the ellipticity.

The pair of scientists studied systems where two large bodies are in orbit and one of these is also circled by a much smaller satellite. In Lidov’s case, the two bodies were the Earth and Moon, and the small satellite was a space probe in the Earth’s orbit. For Kozai’s work, the two large bodies were Jupiter and the Sun, with the small body being an asteroid. They found that the second large body (the Moon or Jupiter) can perturb the orbit of the small satellite (space probe or asteroid). More specifically, the small satellite can lower its inclination (height) above the orbit of the two large bodies in exchange for increasing its orbit’s ellipticity. This results in an alternating switch in the small satellite’s orbit between height and ellipticity, where it will move from a highly inclined orbit to a highly elliptical one and back again. The mechanism became known as the Kozai-Lidov mechanism.

In the case of WASP-17b, the two large bodies of the Kozai-Lidov mechanism would be the planet’s star and a second companion star, or even a more massive planet. Being the smallest object in the system, such a companion could start to change the orbit of WASP-17b.

This scenario allows WASP-17b to form in a tidy near-circular orbit beyond the ice line. As it begins to feel the tug from the second star’s gravity, the height and ellipticity of its orbit begins to change. Eventually, the height can become so extreme that the planet flips over to follow a retrograde path.

As the orbit becomes more elliptical, its new bent path takes the planet closer to the star. This causes the gravitational pull from the star to increase during the nearby section of the planet’s orbit, and decrease as the planet moves away. Varying the force from the star’s gravity flexes the planet like a rubber ball. This produces heat, puffing up WASP-17b’s atmosphere to exceed Jupiter proportions in an effect known as tidal heating. The energy to create the heat is removed from the planet’s orbit, and the planet is forced to circle more closely to the star. 2 This fights the Kozai-Lidov mechanism, eventually forcing the planet into a close circular orbit. What is left is a hot Jupiter.

The Kozai-Lidov mechanism provides a second way of creating a hot Jupiter. But is a giant planet’s migration more commonly due to gas drag, the pull of a distant star (or bigger planet) or the scattering from another planet?

In fact, all methods may be at work. For hot Jupiters in prograde orbits with no obvious star or massive planet companions, gas-driven migration probably dragged them inwards. Retrograde planets or those orbiting stars in binaries could have fallen victim to the Kozai-Lidov mechanism. The remaining hot Jupiters were then scattered inwards by another planet that either lurks further out, or was cast from the planetary system entirely when it kicked its neighbour towards the star.

This trio of options indicates that despite the surprise of hot Jupiters, it turns out there are many ways to create one.

As more planets were found around stars beyond our own Sun, other planets were found snuggled up to their stars. These new worlds were smaller than the hot Jupiters and unlike any planet we had yet seen.

Notes

1. Using telescopes on Earth, rather than in space.

2. Like running around a valley, it takes less energy to run close to the bottom than to climb to the top and run around the rim. Likewise, widely spaced orbits have more energy than close ones.