Twenty years after 51 Pegasi b shattered the theories of planet formation, astronomers came to an important conclusion: we are not normal.

Nearly 2,000 planets had now been discovered travelling around stars beyond our Sun. From these observations, it was estimated that 1 per cent of stars hosted a hot Jupiter, making these strangely located gas giants numerous, but still relatively rare. However, circling half of regular stars like our Sun was a type of planet unlike any seen in our own Solar System.

Labelled the super Earths, these planets were bigger than the Earth, but smaller than Neptune, with sizes stretching between 1.25 and 4 Earth radii. Most of the discoveries orbited their star in less than 100 days, with many circling even closer than the hot Jupiters. The most common orbit for the hot super Earths was at 0.05au; just 5 per cent of the distance from the Sun to the Earth, and 13 per cent of the distance to Mercury.

With a size between our largest rocky planet and our smallest gaseous one, what were these worlds? Had we discovered mega Earths with solid surfaces coated in thin atmospheres, or were these mini Neptunes, with small solid cores engulfed in gigantic gas envelopes? How did they end up so close to their star and why does our Solar System not have a planet that size? Could the answer be tied to how likely life is to arise in the Universe?

Without an analogue in our own Solar System, astronomers were left to untangle the origins of the most common type of planet in their data without having a familiar comparison.

In late 2011, NASA determined that after 34 years of travelling through space, its Voyager 1 probe was on the brink of leaving the Solar System. The exact exit date was announced multiple times over the next few years to an increasingly amused public audience, spawning headlines that included ‘Humanity leaves the Solar System – or maybe not’ from TIME magazine, and ‘Voyager has left the Solar System (this time for real!)’ by the US NPR news. The problem was that defining the exact edge to the Solar System was a nearly impossible task, especially as we only had models to tell us what to expect to find there.

Despite these issues, the journey of Voyager 1 made one fact absolutely clear: since it has taken from the probe’s launch in 1977 until recent times to approach the boundary of our own planetary system, we were not going to visit an exoplanet any time soon.

Our nearest star (apart from the Sun) is Proxima Centauri; a dim star that sits 4.24 light years from Earth. The star is thought to host a planet with a minimum mass 30 per cent larger than Earth, making this our nearest possible exoplanet. Yet Proxima Centauri is still almost 2,000 times further than Voyager 1 has currently travelled. At the space probe’s current velocity of 60,000km/h (37,000mph), it would take more than 75,000 years to reach the nearest possible planetary system – so due to the vast distances involved, sending a probe to uncover the mysterious properties of the super Earths is a disappointingly unviable option. However, at least distinguishing between a rocky terrestrial world and a gaseous Neptune would be possible if we could measure the planet’s density.

Born too close to their star’s heat for ices to form, terrestrial planets like the Earth are built predominantly from silicates and irons. These heavy materials give these worlds high densities, with the values for Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars ranging between 3.9 and 5.5g/cm3. For a similar composition, a higher mass planet will result in a higher density, as the stronger gravity acts to further squeeze the rock. Planet interior models reveal that a rocky super Earth with five times the mass of our planet would have a density of around 7.8g/cm3.

On the other hand, most of Neptune’s bulk is in its huge atmosphere. This gas mainly consists of hydrogen and helium, the two lightest elements in the Universe. These dilute Neptune’s density to be a low 1.6g/cm3. A gaseous version of the super Earth would be a mini Neptune, with a thick atmosphere engulfing a core of rock or ice. The density of a 5 Earth-mass gas planet might be around 3–4g/cm3; higher than Neptune due to its smaller mass attracting less light gas, but far below that of a rocky super Earth.

The average density of a planet is simply the planet’s mass divided by the volume of space it fills. Since planets are approximately spherical, this comes down to two values: the planet mass and the planet radius. Unfortunately, not only is acquiring both measurements challenging, but the uncertainty in the recorded value can be large. For a planet finely balanced between a massive terrestrial world and a small gas giant, this uncertainty can leave us as much in the dark about the planet’s type as would the sex of a foetus with its legs crossed in the womb.

One frustrating example of this was the super Earth orbiting the star Kepler-93. As its name suggests, Kepler-93 was observed by the Kepler Space Telescope in the search for transiting planets. The star was one of the brightest the telescope examined, allowing both a swift announcement of a closely orbiting planet in 2011, and an impressively precise measurement of the planet’s size. Kepler-93b took only 4.7 days to circle its star and had a radius of 1.478 Earth radii, with an uncertainty of just 0.019 Earth radii, or 119km (74mi). This meant that the true value of Kepler-93b’s radius lay in a narrow range between 1.459 and 1.497 Earth radii, designating it a clear super Earth.

This accurate radius measurement was followed up with an attempt to determine the planet’s mass. Using the Keck telescopes on the summit of the dormant Hawaiian volcano of Mauna Kea, Kepler-93 was scrutinised for a telltale radial velocity wobble. The stellar jiggle was seen, but the motion was difficult to pin down. Initial estimates found that Kepler-93b weighed in at 2.6 Earth masses, but with a massive uncertainty that suggested the planet could be as large as 4.6 Earth masses. Further measurements helped to constrain the pattern of the star’s motion, giving Kepler-93b a mass of 3.8 Earth masses, with an uncertainty of 1.5 Earth masses either up or down. This was better, but a mass range of 2.3–5.3 Earth masses inside a planet radius of 1.478 Earth radii left a large number of options for the planet type. In fact, the resulting average density range of 4–9g/cm3 indicated that Kepler-93b could have been anything from a gaseous world through to a rocky terrestrial planet. So despite an extensive set of observations, the nature of Kepler-93b remained a mystery.

It was not until four years after the announcement of the radius measurement for Kepler-93b that the planet’s nature was revealed. An additional set of radial velocity observations, using the European Telescopio Nazionale Galileo in the Canary Islands, nailed the planet mass down to 4.02 Earth masses, with an uncertainty of just 0.68 Earth masses. This yielded an average density estimate of around 6.88g/cm3, pointing to Kepler-93b being a giant rocky planet. So did this mean that all super Earths were in fact larger versions of our own home planet?

In the beginning of 2014, astrophysicist David Kipping was searching for exomoons; moons orbiting extrasolar planets. It was an ambitious objective. The largest moon in our Solar System is Ganymede, a satellite of Jupiter with a mass double that of our own Moon and 2.5 per cent that of the Earth. While exoplanets might host larger moons, these planetary satellites would have only a tiny effect on the star.

A potential solution to this was not to search for the moon’s effect on the star, but for its effect on a planet. Like the star and planet, a planet and its moon orbit a common centre of mass. This causes the planet to wobble during its orbit around the star. If the planet transits, the wobble will slightly alter the times of concurrent transits. The situation is similar to running circuits on an athletics track holding on to a small child. When the child is pulling you forwards you move slightly faster, and you slow when the child drags you back, causing a variation in your lap time. Observing a change in the time taken for a planet to appear back in front of its star between orbits might therefore be a smoking gun for the presence of a hidden moon.

This technique is known as transit timing variations, or TTV. In their 2014 journal paper, Kipping’s team presented data from eight transiting planets, hunting for slight changes in their periodic appearances. To their excitement, they found a variation in one of the transit times. But this was not due to a moon.

The transiting planet was orbiting a cool star known as Kepler-138. Three planets had previously been identified by the Kepler Space Telescope, all with very small radii of between 0.4 and 1.6 of the radius of the Earth, and situated close to the star with orbits lasting less than one month. The wobbling planet was the outermost in the system, Kepler-138d. However, its wobble was not caused by unseen moon, but from the drag and pull of the middle neighbouring planet, Kepler-138c.

While it was initially disappointing that the first exomoon had not been discovered, the result still hit the record books. Like the wobble in the star, the variations in the transit time could act as a set of weighing scales for the planet’s mass. Kepler-138d turned out to be the lightest world to have both its size and mass measured. 1 The previous record holder had been a rocky planet, Kepler-78b, which was 70 per cent heavier than the Earth. Kepler-138d clocked in at just 1 Earth mass.

Such a near match in mass to our home world ought to have made the nature of Kepler-138d obvious. This should be a rocky terrestrial world, too hot to host liquid water but with a solid surface and thin atmosphere. However, the radius of Kepler-138d was almost 60 per cent larger than the Earth’s, making the density four times lower than that of our planet and only 30 per cent higher than water. This was no rocky world, but a very small Neptune.

Further observations in 2015 adjusted the mass of Kepler-138d downwards to 0.64 Earth masses, and the radius to 20 per cent larger than the Earth’s. This still left the planet with an extremely low density of 2.1g/cm3, and a thick atmosphere.

Speaking for the media, Kipping commented, ‘This planet might have the same mass as Earth, but it is certainly not Earth-like. It proves that there is no clear dividing line between rocky worlds like Earth and fluffier planets like water worlds or gas giants.’

Our most common planet type would appear to be like a bag of mixed marbles: similar in size, but wildly different in design.

The varied nature of the super Earths had astronomers hooked. While Kepler-138d and Kepler-93b proved that there was no sharp divide between the massive terrestrial and small gaseous worlds, was there an approximate splitting point between the two planet types?

In 2014, roughly 70 super Earth planets had both mass and radius measurements. The average density of these planets suggested a rough rule of thumb that a planet with a radius of more than 1.5 Earths would have the thick atmosphere of a mini Neptune.

There were many exceptions to this rule in both directions. The size of Kepler-138d should have made it rocky, but it was gaseous. Meanwhile, a planet denoted BD+20594b was found to have a radius of 2.2 Earth radii, but with a density high enough to make it predominantly rock. Nevertheless, for cases where only the size of the planet was known, the 1.5 Earth-radius rule provided a good first guess.

What was now needed was a way to explain how such a diverse collection of planets reached their positions so close to their stars.

Chthonian planets

Two classes of planet had now been found orbiting exceedingly close to their stars: the hot Jupiters and hot super Earths. This gave astronomers cause to wonder if these two planetary types could be linked. Were super Earths just hot Jupiters whose giant atmospheres had somehow been siphoned away?

Evidence for this theory came from the first transiting planet to be detected: HD 209458b. In the autumn of 2003, the hot Jupiter was observed trailing its atmosphere like a gigantic comet as it crossed in front of its star. The blazing heat from its three-and-a-half-day orbit was evaporating away the gas giant’s enveloping gases. If a significant amount of atmosphere were to be stripped, the planet might shrink to the size of a super Earth. The result would be either a mini Neptune or an exposed solid core. The skeletal nature of this product led the hypothetical worlds to be known as chthonian planets; beings of the mythological Underworld.

Despite their darkly imaginative appeal, the existence of super-evaporated chthonian planets was debatable. Hot Jupiters had such huge atmospheres that even the evaporation observed for HD 209458b might not be enough to produce a super Earth during the star’s lifetime. However, evaporation was not the only way to remove an atmosphere.

As a hot Jupiter moves inwards from the outer Solar System, the pull of the star gets stronger. This causes the planet’s Hill radius to shrink, so that its own gravity dominates over a smaller region. Since the planet’s atmosphere has collapsed down to a size much smaller than the Hill radius, this initially makes no difference. But when the planet gets extremely close to the star, the star’s gravity can dominate inside the atmosphere and begin to drag gas away from the planet. Like strong evaporation, this could leave a chthonian planet as a small gas world or an exposed core.

The fact that super Earths can be found closer to their star than hot Jupiters supports the idea of a stripped-down planet. Hot Jupiters would have their atmospheres siphoned away at 0.1–0.05au, leaving any planet that has migrated beyond that point to be a super Earth. If this proved to be true, then a rocky super Earth might be giving us a tantalising glimpse of the inside of a gas giant.

Yet there is a problem; we see very few planets in between the size of a hot Jupiter and a hot super Earth. If hot Jupiters are destined to become super Earths, we should see planets with sizes in between the two regimes as their atmospheres get stripped. Yet almost all the planets we observe close to their stars are either hot Jupiters or super Earths; just the start and end points of the chthonian theory. There is no population of hot planets between Neptune and Jupiter in size. While not completely impossible, it does seem highly unlikely that we have just missed observing these worlds. So if super Earths are not just overflowing hot Jupiters, what are the other options?

Building local

A tempting idea is to form super Earths at their current locations. If the star’s natal protoplanetary disc could birth these worlds directly, it would explain why the planets are so numerous. We previously dismissed the possibility that massive hot Jupiters could form where there is so little rocky material, but was this still true for the much smaller super Earths?

Our Solar System’s innermost planet is Mercury; a world just 5.5 per cent of the Earth’s mass sitting at a respectable distance of 0.4au. This is more than three times further out than the main populations of both the hot Jupiters and super Earths.

At first glance, this situation ought to be the norm. The size to which a planet can grow hinges on how much material it can gather from the protoplanetary disc. This depends on the quantity of dust and planetesimals surrounding the growing planet, and the extent of the planet’s gravitational reach (Hill radius). Close to the colossal tug of the Sun, the planet’s gravity can control only a small region of space, restricting the amount of new material that can be reeled in for growth. Planets close to their stars should therefore be small.

But what if our Solar System was abnormal from birth? While our protoplanetary disc had very little material close to the Sun, perhaps a more typical example was rich in dust around the region where super Earths form. This would enable even a small Hill radius to gather plenty of solids.

We constructed our protoplanetary disc in Chapter 1 by taking the current positions of the planets and smearing them out around their orbits to recreate the dusty beginnings. The result was the Minimum Mass Solar Nebula. What happens if we do the same with the planetary systems than contain super Earths?

A protoplanetary disc created from crushed-up super Earths shows where the dust would need to sit to directly build that planet population. Unfortunately, piling material into a planet-making disc can lead to problems. Since a high density of dust would be suspended in a high density of gas, the inner disc now becomes very massive. Like the mechanism proposed for forming gas giant planets in the far outer disc, the inner disc can now break apart due to its own inflated gravity. Should that happen, the new planets would resemble gas giants and be completely different from the super Earths. Moreover, crushing up the planetary systems that contain super Earths produces very strangely shaped protoplanetary discs. Many of these are so weirdly proportioned that they simply could not have formed around a star at all, requiring bizarre anomalies such as the disc becoming progressively hotter further away from the star.

The conclusion is that there is no common protoplanetary disc that can birth super Earths. Instead, the mass needed for these planets must appear after the disc has formed.

The planet broom

The next idea involves a giant broom. When applied to its usual job of sweeping floors, a broom can gather dust into a pile. What seems to be very little dirt when spread evenly over the floor, can turn into a sizeable bag’s worth when swept into a small area. Was there a protoplanetary equivalent of a broom that could sweep rocky grains into a pile big enough to build a super Earth?

Sweeping up rocks avoids the problems of a special super Earth protoplanetary disc. The disc could form in its regular shape, without an unstably high quantity of gas and dust close to the star. The rocky solids would then be gathered from around the disc and deposited at the orbits of the super Earths, allowing these planets to swiftly form. Since the sweep-up would involve solid particles but not gas, the inner disc would not become heavy enough to break apart into gas giant planets. The only question was what could act as a broom? The answer is a hot Jupiter.

A Jupiter-sized planet migrating towards the star will plough into the rocky planetesimals that were building terrestrial worlds. While many rocks will be scattered away or accreted into the planet, others will end up in resonant orbits with their laps around the star synchronised with the Jupiter. In this stable configuration, these planetesimals are forced inwards with the Jupiter to pile up close to the star. Now bunched together, the planetesimals collide to form a world bigger than any in our inner Solar System. The result is a super Earth orbiting closer to the star than the hot Jupiter. It seems plausible, but is there evidence that this really happens?

Gliese 876 is a star smaller and cooler than our Sun known as a red dwarf. It sits about 15 light years away in the constellation of Aquarius, the Water Carrier. Radial velocity measurements of the star’s wobble have revealed four planets, with the innermost world a super Earth of nearly 7 Earth masses on an orbit lasting just two days. Slightly further out with orbits of 30 and 60 days are two hot Jupiters.

The two Jupiters and the outermost Uranus-sized fourth planet have resonant orbits. The innermost of the three giants performs four orbits in the time it takes for the middle planet to orbit twice and the outer planet to orbit once. This 1:2:4 arrangement is the same as that found in Jupiter’s moons, Ganymede, Europa and Io. The resonances support the idea that the three planets migrated inwards together. Their gravitational pull on one another would have coupled their orbits (as happened to Jupiter and Saturn during their grand tack through the Solar System). As they moved inwards, smaller planetesimals could have been caught in further resonant orbits, and shovelled forwards. These rocky pieces would then collide, breaking from their resonance as they formed the inner super Earth.

Notably, the size ratio between Gliese 876’s largest planets is very different from Jupiter and Saturn’s, with the outer world being the larger at more than 2.5 Jupiter masses, and the inner planet at 0.7 Jupiter masses. This probably prevented the planets from performing the U-turn that would have stopped them from becoming hot Jupiters.

The presence of this super Earth’s giant Jupiter brothers gives weight to the theory that closely orbiting planets could form from material swept up during migration. The problem is that super Earths are substantially more common than hot Jupiters. So if a Jupiter is not around to do the sweeping, how does the rocky building material reach the star?

The dead zone trap

It was the planetary system that Jack Lissauer, a space scientist at NASA’s Ames Research Centre in California, described as ‘the biggest thing in exoplanets since the discovery of 51 Pegasi b.’

The find was of six planets transiting the Sun-like star Kepler-11, located in the constellation of Cygnus, the Swan, around 2,000 light years away. Its announcement in 2011 hit the headlines both for the number of transiting planets in a single system and for their arrangement, which was the most tightly packed configuration ever seen.

Five of the planets around Kepler-11 circle the star within the orbit of Mercury, with the sixth only slightly outside. The tugs between the closely orbiting siblings allowed their mass to be measured via their transit timing variations. This close-knit family was revealed to have five super Earths of 2–8 Earth masses. The mass of the last planet in the system, Kepler-11g, was harder to pin down due to the weaker effect the outermost planet has on the other worlds. Estimates suggest a value of less than 25 Earth masses; a Neptune-sized world.

Here was a planetary system with not one, but six planets orbiting close to the star, and no hot Jupiter to shovel material inwards. How could such a system form? To quote Lissauer again, ‘we didn’t know such systems could even exist’.

While the planets of Kepler-11 were a surprise, we do know of an excellent process for shuffling rocks towards the star without a hot Jupiter: the drag from the gas headwind. As rocky boulders near 1m (3.3ft) in size, they can no longer be cradled in the flow of gas but become large enough to dictate their own orbital path. Since they do not feel the gas pressure, these small rocks move slightly faster than the surrounding gas, which results in a headwind. In Chapter 2, this was a major problem as it caused rocky material to be dragged away from where our planets sit and inwards towards the Sun. But could this process aid the production of the hot super Earths?

The main challenge with boulder drag is how to stop this flow of building material before it crashes into the star. Without the hot Jupiter to secure the rocks in resonant orbits, the rapid inflow due to the headwind would lead to incineration. What is needed is a stop sign that allows the rocks to pile up.

To form the Solar System’s planets, we invoked the streaming instability, whereby pelotons of boulders gathered enough mass to shield themselves from the gas drag. However, there is no reason for the streaming instability to preferentially produce these large clusters of rocks close to the star. It is possible that rocky material might collect at the protoplanetary disc edge, beyond which the star has accreted all the gas and dust, but this would not explain a system with multiple super Earths on different orbits. Instead, a more flexible option is to use the magnetic field.

Magnetic fields are everywhere in the Universe. Take an atom, strip one of its electrons and it will have a slightly positive electric charge. Give this charged particle a push, and it will create a magnetic field. It will also feel a force from any magnetic fields already present.

On the other hand, if the atom is neutral (no electric charge) then it does not care about the magnetic field. Its movement does not create a field, nor does it feel a force within a field. This is the reason why electric and magnetic forces (known jointly as the electromagnetic force) in the Universe have a much smaller effect on the construction of galaxies and planets than gravity. A look at the numbers suggests that the electromagnetic force is 39 orders of magnitude larger than the gravitational force. Yet over big distances, the Universe is neutral and responds only to gravity’s tug.

The heat within a star strips atoms of their electrons to create a multitude of moving charges that generate its magnetic field. These field lines weave through the surrounding gas and dust in the protoplanetary disc. The effect this has depends on the number of disc particles that are charged.

Energy radiating from the star can strip atoms in the disc of their electrons, creating charged particles of gas and dust that then become susceptible to the magnetic field. The magnetic forces ruffle up the particle orbits, aiding the accretion on to the star. Turn off the magnetic field and the rate of inward gas flow drops right down. Closest to the star, the disc feels the full force of the star’s radiation. This creates plenty of charged particles to respond to the magnetic field. But before we get to about 0.1au, the star’s energy will struggle to penetrate the gas all the way through to the centre of the disc. The number of charged particles drops and the gas stops feeling the magnetic field.

The region where the magnetic forces are turned off is referred to by the ominous-sounding term, the dead zone. Gas between the star and the dead zone edge flows easily inwards, while gas within the dead zone moves more slowly. The result is similar to a traffic jam, and the gas density rises at the dead zone edge. The gas pressure rises along with the density boost, shifting the forces felt by the gas at that point in the disc. This allows the gas to orbit at the same speed as the rock, removing the headwind on the boulders. No longer dragged towards the star, these rocks collect around the edge of the dead zone and begin to collide to birth a super Earth.

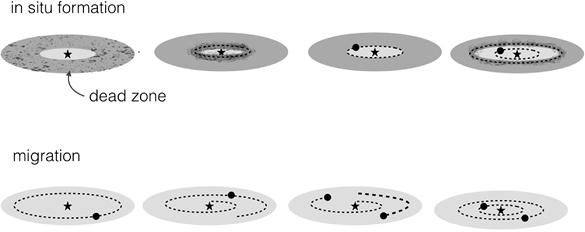

Figure 10 Hot super Earths either form from rocky material that has been swept towards the star (in-situ formation) or further out in the protoplanetary disc and migrate inwards. In one possible in-situ formation mechanism, rocky boulders are dragged inwards by the gas. These collect around the edge of the dead zone, where the disc does not have enough electric charge to feel the magnetic field. The boulders collide to form a planet, whose gravity opens a gap in the gas disc. The gap allows the star’s radiation to create more charged particles, moving the dead zone outwards. Boulders can then collect at the new edge and form a second hot super Earth.

This shift in the gas flow around the growing super Earth also acts as a planet trap and throttles Type I migration. Rather that shooting off towards the (dangerously close) star, the planet can continue to grow until it can open a gap in the gas disc. This should kick-start Type II migration, but the super Earth is so massive compared with the gas this close to the star that the gas drag may be too weak to move it. Regardless of the planet’s locomotion, the gap allows the radiation from the star to penetrate the disc. Dust and gas are stripped of their electrons to become charged and feel the magnetic fields. The dead zone breaks close to the planet and its edge moves outwards past the planet’s gap. At this new dead zone edge, planetesimals can collect afresh to build the next super Earth. When the gas disc evaporates, a series of super Earths may be left orbiting close to the star. This appears to be very close to what we see in Kepler-11.

Although boulder drag was a promising mechanism for a production line of super Earths, the Kepler-11 system was not yet done with surprises.

Combining the mass measurements with the size from their transits revealed that none of the Kepler-11 planets were rocky. Rather, their densities suggested that they were covered in a thick gas atmosphere that envelops half the extent of the planet. The exception was the innermost planet, Kepler-11b, whose higher density pointed to a larger core filling two-thirds of the planet’s size. However, even this is a much larger gas atmosphere than there is on an Earth-like world. The Kepler-11 planets were all mini Neptunes.

To match the observations of super Earths, any formation idea must be able to encompass both large rocky planets and small gas giants. So was it possible for a world born so close to its star to acquire the thick atmosphere of a mini Neptune? As it turns out, the difficulty is not how to gather gas, but how to stop.

Before the protoplanetary disc gas evaporates, a newly forming planet can pull in an atmosphere from this surrounding reservoir. On short orbits in a region packed full of planetesimals, super Earth formation should be very efficient, taking considerably less than a million years. This leaves plenty of time to accrete enough gas to become a mini Neptune. In fact, the main risk is going too far and becoming a hot Jupiter.

Hot Jupiters were previously thought to be too massive to form close to their stars. But was this assumption too hasty? With the ability to channel building material to the inner regions of the disc, would we end up with Jupiter-sized worlds?

As Jupiter grew in the outer Solar System, its gravity began to attract a large amount of gas. Eventually this became so heavy that the atmosphere went into runaway collapse, with gas piling on to the planet as the atmosphere continued to compress. This process subsided when the planet’s gravity opened a gap in the gas disc. By this time, a large gas giant had been born. This looks like an unstoppable situation, but it transpires that there is a solution.

Building from piles of rocks that have been swept inwards to the dead zone, a young super Earth’s atmosphere is heavy with dust. This prevents the planet’s gaseous envelope from cooling efficiently, since the dust grains block radiation escaping the planet (in more technical language, the atmosphere has a high opacity). The higher temperature of the gas supports it against the planet’s gravity, delaying runaway collapse until after the gas disc has evaporated. The result is that the planet is able to gain a thick atmosphere, but nothing close to the drowning gases of a hot Jupiter.

Whether a super Earth becomes a giant terrestrial planet or a small gas world could depend on the protoplanetary disc. Heavier discs can assemble a super Earth planet more rapidly, allowing more time to grasp bigger atmospheres. For lighter discs, the super Earths might not form until the gas was close to evaporation, leaving these planets rocky, with thinner atmospheres.

Building planets in their observed location is known as in-situ formation. The hot Jupiter shovel and boulder drag make in-situ formation for super Earths a serious possibility. But this did not completely seal the deal for super Earths.

While Kepler-11 became the prototype for stars closely orbited by tightly grouped planets, it was far from alone. A year after its discovery, Kepler-32 was found, with five planets all smaller than 3 Earth radii and with orbital times of 0.7–22 days. Then three more planets were found surrounding the star HD 40307, bringing its total up to six planets with less than about 7 Earth masses, five of which have periods of 4–52 days. Other systems followed, suggesting that more than 10 per cent of stars might have a similar configuration of worlds.

So if this was a common outcome for planet organisations, why again was our Solar System different? Our gas giants may have avoided becoming hot Jupiters, but the early days of the Solar System should have seen a stream of planetesimals flowing towards the star. Yet we failed to form even one super Earth.

There was also debate about whether a planet forming in-situ could hold on to the large atmosphere of a mini Neptune. With a formation site packed with material, but the planet’s Hill radius still small, a collection of Earth-sized embryos might initially be produced (due to an Earth-sized isolation mass, in the language of Chapter 2). This would be followed by an extended period of giant impacts between the embryos to form the super Earth. These large collisions risk vaporising the gases of the new world, leaving only a thin envelope surrounding a rocky planet.

Possible explanations existed to weave around these problems: the dead zone may change between protoplanetary discs, another process might interfere with the planetesimal flow, and giant impacts may not always be necessary. But this did provide enough doubt to explore other options.

A migrating population

Away from any planet traps, the chunky mass of the super Earths should result in swift migration. Did this make it likely that the super Earths migrated towards the star from much further out?

The idea that super Earths were born far away from the star has nice and not-so-nice features. The lack of a clear divide in the size of rocky super Earths and mini Neptunes suggests that these planets are a single class, forming through the same mechanism. Since our own Neptune formed past the ice line in the outer Solar System, it seems reasonable that hot mini Neptunes, and therefore the rocky super Earths, might all begin in a similar location. The rocky planets would be the versions that failed to acquire huge atmospheres, due either to lack of mass or from having formed close to when the gas disc was evaporated.

This also ties their evolution to the hot Jupiters. In all cases, large planets could start beyond the ice line, where there is plenty of planet-building material. Far from the star, the planet’s Hill radius is large and it can swiftly gather mass and gases, and avoid atmosphere-stripping collisions.

This also provides an explanation for our Solar System’s lack of super Earths. Jupiter and Saturn’s U-turn grand tack prevented the migration of Uranus and Neptune. Without our largest gas giants barring their path, the embryos of these smaller worlds might have travelled inwards towards the Sun. In one movement, we have removed the need for a slew of different planet-formation mechanisms to explain these varying worlds.

Yet this assertion about the universal power of migration is a bold statement. It would mean that major planet reorganisation is a common occurrence. While hot Jupiters most probably migrated inwards, they only appear around 1 per cent of stars. On the other hand, hot super Earths are thought to orbit around 50 per cent of stars. For all these planets to have changed orbits, migration must not only be possible, but it must be a major player in planetary-system architecture.

There are also some observations that do not match this picture. As with Jupiter and Saturn’s brief spate of migration, the tugs between neighbouring planets moving through the gas disc should result in resonant orbits. The outer planet should approach its inner neighbour either during migration, or when the innermost world stops at the protoplanetary disc inner edge. Their orbits will then slide into resonance, with an exact integer ratio between their orbital times. While this is seen for a few systems, such as Gliese 876, many others, such as Kepler-11 and HD 40307, show no such pattern. So does this mean that migration definitely did not occur?

Although resonant orbits would support the migration picture, it turns out not to be a deal breaker. One reason for this is that Type I migration is an infuriatingly picky process. As we have seen with planet traps, the first stage of migration is very sensitive to the conditions of the surrounding gas. It also depends on planet mass. The more massive the planet, the stronger the gravitational pull with the gas disc. Heavier planets typically migrate faster, until they are able to open a gap in the gas and slow to Type II migration. However, there can also be regions in the disc where a combination of the planet’s pull and local gas conditions can flip the direction of migration for a short period. This leads to migration paths depending strongly on the specific combination of forces from the planet’s current mass, gas conditions at its present location and any pulls from neighbouring planets. 2

Such tailor-made migration tracks allow more flexibility in the positions of planets when the gas finally evaporates. In one set of computer models for this contrary process, a region for reverse migration developed for planets above 5 Earth masses. The planetary embryos able to grow fast enough to hit this sweet spot were potential hot Jupiters. These most massive worlds were then delayed in reaching the star to leave them stranded slightly further out than the smaller super Earths. This matches up with the observation that hot Jupiters cluster behind the super Earth population. It also supports their relative rarity, since rapid growth was needed to hit the region of outward migration with enough beef to be turned around. Such varying paths are also more difficult to lock into resonance, leaving planets with a broad range of separations.

Other methods joined this idea in support of super Earth migration. Another possibility was that the planets could initially have been in resonance, but were later knocked about by bombardment from the remaining rocks once the gas had evaporated. This follows the evolution of our own giant planets, whose orbits shifted as they scattered planetesimals. Alternatively, the closely orbiting super Earths could be affected by an unseen giant planet further from the star. In a distant location more difficult to detect, the presence of a big gravitational bully could ruffle the orbits of super Earths to break up their resonances.

With the idea of migrating super Earths firmly on the table, a second concern arose. If migration was a major way to form super Earths, could any system with a closely orbiting planet support a habitable world like our own Earth?

Did Saturn save our planet’s bacon? Without the second gas giant, Jupiter would have followed the fate of worlds such as 51 Pegasi b, crashing through the inner Solar System on the way to the Sun. It may well have been followed by Uranus and Neptune, migrating to become closely orbiting super Earths. As they travelled inwards, these giant worlds might have battered our precious Earth to pieces.

The Earth’s location at 1au is key to its habitability. This distance from the Sun means that the planet receives just enough heat to be neither too hot nor too cold to support our existence. If it could not form at this position due to the migration of outer planets, there is a high chance life would never have evolved.

So can a world like our Earth exist behind closely orbiting hot Jupiters or super Earths? If not, we may be forced to dismiss half of all planetary systems in a search for alien neighbours. That might make life in the Universe rare indeed.

The inward sweep of a planet is potentially a disastrous event. The gravitational pull from a migrating world will scatter rocky material out of the inner planetary system, shovel planetesimals towards the star and devour a sizeable chunk of the rest. The terrestrial planet zone would be left an empty factory, barren of planet-building material.

Should a young planet have formed before the migration, the sudden pull of an approaching big planet would scatter it on to a new orbit like a comet. A scattered path around the star risks being strongly elliptical, with the planet’s distance from the star varying strongly during its circuit. The result can be extreme seasons as the surface temperature soars and plummets over a planet’s year. It may not be impossible to retain water and develop life in such a condition, but it is going to be difficult.

The prospect is bleak but there is still a glimmer of hope. If enough dust and rocks are left behind the migrating planet, then the building of terrestrial worlds can begin afresh. How much material is left for a restart will depend on how fast a migrating planet sweeps through the system. The precarious Type I migration rates make this hard to estimate, but a planet that lingers around the terrestrial planet-making zone will scatter away more rocky material than a migrating world that zips more quickly towards the star.

Rocky planetesimals that are scattered may also be able to return to more circular orbits due to the gas disc. A planetesimal on an elliptical path is forced to cut across the circular gas flow of the disc. The different speed of gas and solid creates a very strong drag, drawing the rocks back on to circular paths to continue the planet-forming process.

All is also not entirely lost for a scattered planet, which may yet be able to recover a more circular orbit. On a bent elliptical orbit, the planet feels a varying pull from the star as it approaches and then moves further away. As in the case of the hot Jupiters scattered inwards by the Kozai-Lidov mechanism, this fluctuating pull can circularise the planet’s orbit once again. The gas disc will also resist the planet’s orbit becoming elliptical, helping it to maintain a circular path.

Recovery after a migrating planet population may even hold some advantages. A second generation of planets may not reach Mars size until after the evaporation of the gas, removing the need for planet traps to prevent migration towards the star. The large scattering of rocks from the first migrating planets may also deliver ices to the inner system, allowing water-rich worlds to form. The result would be hot planets close to the star, but worlds with more promising conditions (albeit difficult pasts) for life behind them.

An unresolved mystery

The formation of the hot super Earth population remains an intriguing problem. Did they migrate from behind the ice line, or form from planetesimals and boulders shovelled inwards by hot Jupiters or gas drag forces?

One way to untangle these ideas is to hunt for the fainter signatures of outer planets. A star with planets both far out and on close orbits is less likely to have seen strong migration than a star surrounded only by close-in planets. A planet that has formed far from the star will also be heavy in ices. This may produce an atmosphere thick with water vapour that could be glimpsed by the next generation of telescopes. However, until we can unravel the meandering ways of both planets and planetesimals, our most common planet class will remain a mystery.

Notes

1. This was trumped by its own planetary sibling, Kepler-138b, whose 0.07 Earth masses was measured in 2015.

2. The sensitivity of Type I migration to the exact conditions around the planet makes it a big can of worms.