Water, Diamonds or Lava? The Planet Recipe Nobody Knew

Two years after the discovery of 51 Pegasi b was announced, astronomers were becoming skilled at picking out the wobble in a star’s position that hinted at the presence of a planet. The result was six more exoplanet finds, all hot Jupiters like 51 Pegasi b, whose huge mass and close orbits made them the easiest to detect.

The last three of these were announced together in 1997. Among the trio was HR 3522b, a planet slightly smaller than Jupiter on a 14-day orbit. Although the planet was referenced in the journal paper by its listing in the Yale Bright Star Catalogue (HR), it would become more commonly referred to as 55 Cancri b; the first planet found around the 55th star in the constellation of Cancer, the Crab. Its discovery was instantly notable as one of the first planets found outside our Solar System, but this would not be the only record for the planetary system. In fact, 55 Cancri b was the first planet found in a system more alien than anything we could imagine.

Within 10 years of the discovery of 55 Cancri b, four more planets had been detected orbiting the same star. This made 55 Cancri the first star to be found hosting five planets, and also one of the first three to have a super Earth with a mass similar to Neptune; 55 Cancri e is about 8 Earth masses (48 per cent of Neptune’s mass) with an incredibly short orbital time of only 18 hours, sitting at just 5 per cent of Mercury’s distance from the Sun.

Observations of 55 Cancri had revealed it to be one half of a binary. Its stellar sibling is a smaller red dwarf star that sits at a distance of more than 1,000au. While too small and distant to damage the planets forming around its bigger sibling, the regular pull from the red dwarf seems to be causing the planetary system to turn on its head.

This is a similar effect to the Kozai-Lidov mechanism that we met in Chapter 5 as a way of using a stellar companion to move hot Jupiters towards their stars. For the planets of 55 Cancri, the gravitational pulls from the neighbouring worlds hold the planets’ orbits together, so the entire system slowly flips over like a set of synchronised swimmers. If it were possible to stand on the surfaces of these planets and stare at the sky, the constellations would appear to slowly shift as the planetary system performed a somersault. Admittedly, it would take a particularly long-lived life form to notice this, as a full flip would take around 30 million years.

Yet what made the system truly strange was the properties of its super Earth, 55 Cancri e. Like the other planets in the system, 55 Cancri e had been found via the star’s induced wobble with the radial velocity technique. In 2011, NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope also observed the super Earth transiting across the star’s surface. This was another ‘first’ for the planetary system, since 55 Cancri is visible with the naked eye, making its innermost planet the first to transit a star that can be seen without a telescope. The transit observation measured the planet’s radius and the angle of the orbit, pinning down the planet mass. The super Earth’s size was discovered to be 20 per cent larger than the Earth at 2.2 Earth radii. It was another of those values that would appear to make absolutely no sense.

With both mass and radius measurements, the density of 55 Cancri e could be easily calculated as 4g/cm3. Despite a radius that suggested the planet should be a mini Neptune, 1 this density was far too high for a gaseous world with a large hydrogen and helium atmosphere. An 8 Earth-mass mini Neptune should have a density of only 1.3g/cm3. On the other hand, 4g/cm3 was far too low for a rocky Earth-like interior in a planet of that mass. While the Earth’s density is moderately close at 5.5g/cm3, a planet eight times heavier would compress the rock to above 8.5g/cm3. This meant that 55 Cancri e was too small for a gas world and too large for a rocky world. So, what was it?

If this super Earth was a rocky planet, then the ingredients for its composition should match our terrestrial worlds. This indicates a bulk made predominantly from iron and silicates. For a given mass, the smallest rocky planet possible would be one made of pure iron. The largest would have no iron at all, but be made throughout from the lighter silicate rocks. Neither of these extreme versions is very likely. The elements of our terrestrial worlds condense into solids at a sufficiently similar temperature to create a mixed planet-forming flour. Our hottest and most iron-rich planet, Mercury, still retains 30 per cent of its mass in a silicate mantle. Yet even these most improbably extreme examples remain smaller than 55 Cancri e.

What if we attempted to reconcile the radius and mass of 55 Cancri e by abandoning the distinction between terrestrial and gaseous planets and forming a hybrid world? Such a planet would have a rocky core substantially bigger than the Earth’s and be capable of retaining a primitive thick hydrogen and helium atmosphere. Since the gases are so light, even an atmosphere containing just 0.1 per cent of the planet mass could result in a world with the density matching 55 Cancri e.

The hybrid planet would be perfect if it were not for 55 Cancri e’s incredibly short 18-hour orbit. With a year lasting less than an Earth day, the super Earth is looping its star at a distance of just 0.016au. This proximity to a burning nuclear engine gives the planet an estimated average temperature of around 2,000°C (3,600°F). At these blistering values, the planet’s mass will struggle to stop a light atmosphere of hydrogen and helium evaporating away. Such an atmosphere should be burned off within a few million years, which is short in planet-formation terms. This makes it unlikely that we would catch sight of 55 Cancri e while it still had a primitive envelope of gases.

With a Neptune-like atmosphere out of consideration, what could be less dense than rock but still heavy enough to be held by the planet? The answer might be a very strange state of water.

If 55 Cancri e had originally formed beyond the ice line, then it would have been born packed full of ice. As it migrated towards the star, the hydrogen and helium in its atmosphere would be lost to leave a rocky core under a water-vapour envelope thousands of kilometres thick. The idea that a planet orbiting so close to the inferno of its star could be covered in water is indeed bizarre. The water on this planet would certainly not resemble the cool liquid that comes out of a kitchen tap. Instead, the water on 55 Cancri e would exist in an extremely rare state known as supercritical.

Supercritical fluids occur at very high temperatures and pressures. For example, rocket fuel is in a supercritical phase when it is blasted from the tail of a launching spacecraft. In this form, the distinctions between liquids and gases become blurred to leave a substance somewhere in between these definitions. On such a world, it would be impossible to tell where the oceans met the sky. If it were possible to survive, you would find yourself suspended somewhere in the supercritical fog.

A burning-hot world with an 18-hour year, enveloped in a liquid-like gas on an orbit that slowly flips over, is a strange place indeed. Yet, there is an even weirder explanation for the composition of 55 Cancri e. Rather than supercritical water, the super Earth could be heavy in diamonds.

While 55 Cancri is a star similar in size to our Sun, its composition is not identical. Rather, 55 Cancri is suspected of being rich in carbon. Until they reach old age, stars mainly consist of hydrogen and helium with trace amounts of other elements, such as carbon, oxygen, magnesium, silicon and iron. The Sun has roughly half as much carbon as oxygen, a trait that is typically expressed as the ratio between these two elements, C/O = 0.5. In contrast, observations of 55 Cancri in 2010 suggested that the star has actually slightly more carbon than oxygen, with a ratio C/O = 1.12. These differences in stars are important since the protoplanetary disc is made from the same material. Therefore, if the star is carbon rich, it is likely that the grains of dust that form the planets will also be enhanced with carbon. This could build worlds out of very different material from our terrestrial population.

Despite its importance for biological life, the Earth is surprisingly carbon poor. Ninety per cent of the Earth’s mass is in iron, silicon, oxygen and magnesium. The majority of the iron is in the Earth’s core, with the remaining elements forming the silicate mantle and crust. Carbon is only a minor constituent, making up less than 0.2 per cent of the Earth’s mass. This tiny fraction is because carbon only condensed into solid grains in the cold outer Solar System. Around the forming terrestrial worlds, it remained a vapour and was blown away as the Sun dispelled the gas disc. As is the case with the possible origin for our oceans discussed in Chapter 4, the Earth began devoid of carbon and received its meagre quantity from meteorites sailing inwards from the outer Solar System.

Should the fraction of carbon get a boost and rival (or even exceed) the fraction of oxygen atoms in the protoplanetary disc, the solid building material begins to change. With carbon atoms controlling the scene, silicon starts to bond with carbon rather than oxygen to form solid silicon-carbide instead of silicate. Planets born from this dust would be made from carbon and the new silicon-carbide, rather than oxygen compounds.

If 55 Cancri e has such a carbon-rich interior, the need for a volume-boosting envelope of lighter material vanishes. For the planet’s observed mass, a solid body made from iron, carbon and silicon could produce the correct radius. Not only does this remove the need for supercritical water, but 55 Cancri e might not have any water at all.

In a carbon-rich protoplanetary disc, the oxygen would be grabbed by the carbon to form the toxic carbon monoxide. There would be little oxygen left to bond with hydrogen and form water. Even the outer planetary system might therefore have no water ice. Modelling the planetesimals forming in carbon-rich systems, Torrence Johnson of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California jibbed, ‘There’s no snow beyond the snow line.’

The lack of water in the planetary system means that even if 55 Cancri e were on an orbit that allowed a more agreeable climate, due to its carbon base it might be incapable of supporting any life that we currently recognise. Collaborating with Johnson, Jonathan Lunine of Cornell University commented humorously, ‘It’s ironic that if carbon, the main element of life, becomes too abundant, it will steal away the oxygen that would have made water, the solvent essential to life as we know it.’

Aside from having no water, what would a carbon world be like? The crust would probably be graphite, the substance that is found in pencils. Beneath the planet’s surface, the pressure would mount to produce a mantle of diamond. Much of the carbon in the Earth’s mantle also exists as diamond, oxidising to carbonate near the crust as the pressure drops. The reason why we are not rolling in gems is that the total quantity of carbon is so low, below 0.2 per cent compared with just over 50 per cent oxygen. On a carbon world, the quantity of diamond would cause these glittering gems to erupt from the ground during volcanic activity.

If liquid existed on the planet, then it would also be a carbon-based substance such as a sea of tar. The atmosphere would be heavy in carbon monoxide and dioxide, while carbon-heavy rain would make the air thick with smog. This is the optimistic picture. The planet may actually have no atmosphere at all.

The interior of the Earth is an active machine. The crust is split into rigid chunks known as tectonic plates. Beneath these is the planet’s mantle. While the Earth might appear solid, over geological timescales of millions of years, the mantle moves as a highly sluggish fluid. This acts as a conveyer belt for the tectonic plates and shuffles them around. When two plates move apart, the underlying mantle is exposed and cools to form fresh crust. Older and thicker crust is melted where plates slide under one another, often creating volcanoes at this boundary. These movements of the crust and mantle circulate the planet’s atmosphere and nutrients, and even generate the magnetic field. However, replace our mantle with diamond, and this essential motion becomes much more difficult.

Diamond has a very high viscosity; a fluid friction that controls how sluggishly materials flow. Syrup is more viscous than water, and a diamond mantle is about five times more viscous than a silicate layer. If the carbon fraction of a planet exceeds 3 per cent, the difficulty in moving the mantle can draw the moving plate tectonics to a screeching halt.

The absence of plate tectonics would give a planet an immobile lid, making it far harder for volcanoes to form. While a decrease in the number of explosive mountains might seem like a positive attribute, it also suppresses the development of an atmosphere. The resulting world would be a stagnant body, heavy in gems but lacking in air.

The graphite crust of the planet might also make it too hot. Even on an Earth-like orbit, the dark colour of the graphite would absorb, rather than reflect, sunlight. The planet would be the black car in a Florida car park, 2 compared with the green-and-blue Earth version. This would be a problem for maintaining surface liquid water, even if it were possible to somehow acquire oceans.

All of this considered, the lure of a planet of beautiful gems is not sufficient to make a carbon world an appealing property.

Before 55 Cancri e could officially be declared a carbonic hellhole, its carbon credentials were called into question. The problem was that measuring a star’s C/O (carbon to oxygen) ratio is a difficult business. To point the finger of blame more directly, it is measuring the star’s oxygen content that is particularly tricky.

Stars consist of incredibly hot, dense cores surrounded by a slightly cooler atmosphere of low-density gas. In the Sun, the temperature of the core can reach more than 15,000,000°C (27,000,000°F), while the outer layer is at 5,500°C (10,000°F). This outer atmosphere is known as the photosphere of the star. The photosphere’s temperature is still intense, but it is cool enough to allow atoms to hold on to their electrons. These electrons are arranged on a ladder of unequally spaced energy levels. As the radiation pours from the core, the atoms absorb wavelengths with the right energy to flip an outer electron on to one of the higher energy rungs. Which wavelengths are absorbed depends on the energy levels occupied by electrons, and therefore the type of atom. By examining a star’s light and seeing which wavelengths are absent, the different atoms in the star can be revealed.

Difficulties arise when two different atoms absorb at very similar wavelengths. It can become hard to separate out the two, creating uncertainties in the quantity of each atom. In the case of the C/O measurement for 55 Cancri, the commonly measured wavelength for oxygen was extremely close to one for nickel. In 2013, data from the star was freshly examined. Rather than relying on differentiating between the main oxygen and nickel wavelengths, three different wavelengths that oxygen atoms can absorb were compared to the absorption from nickel. The conclusion was that the C/O ratio in the star was much lower than the initial 1.12, at around 0.78. Carbon replaces oxygen in silicon compounds about when the protoplanetary disc gas has C/O ~ 0.8. This new value therefore put 55 Cancri e right on the brink of being a carbon world, with the answer resting on a particularly challenging observation.

For those desiring an abhorrent carbon world, a further complication could save the situation. While the star and the protoplanetary disc are born with the same composition of atoms, the solid particles in the disc change over time.

When exploring the formation of our protoplanetary disc in Chapter 1, we noted that the material of the dust grains depended on temperature. Closer to the Sun, silicate and iron compounds that only vaporise at high temperatures are present. Volatile molecules such as water remain as a gas until the temperature drops past the ice line. Yet this transition from gas to solid does not happen instantly. The ages of meteorites that have fallen to Earth suggest that contrary to appearing in a single burst, the solid particles that built our planets condensed out of the gas over 2.5 million years. This is long enough for conditions in the protoplanetary disc to change to give carbon-heavy planetesimals a boost.

When the C/O ratio sits below 0.8, carbon remains a gas through much of the protoplanetary disc. Silicon grabs the oxygen to form grains of silicate, leaving the carbon untouched. This steadily depletes the gas of oxygen and the C/O ratio begins to rise. Solid particles forming later in the disc may therefore come from a gas so carbon heavy that graphite and silicon carbide preferentially form.

This means that even if the protoplanetary disc gas initially has a C/O ratio of less than the magic 0.8 value, it may still end up with a large quantity of solid carbon. Calculations suggest that a value as low as C/O = 0.65 is sufficient to produce carbon-rich planetesimals. Not only could this make 55 Cancri-e a carbon world, but it would not be alone.

The C/O ratio in our local stellar neighbourhood suggests that a third of planet-hosting stars might have a C/O ratio above 0.8 and harbour dastardly carbon worlds. Even if this value proves to be an over-estimate due to the difficult oxygen measurement, carbon planets may still form a significant population. Two of the stars found with notably high C/O ratios are hosts to gas giants. HD 189733 is 63 light years away in the constellation of Vulpecula, the Fox. Its gas giant is a hot Jupiter with an orbit lasting 2.2 days. HD 108874 is 200 light years away in the constellation of Coma Berenices (Hair of Berenice, an Egyptian queen), and has two Jupiter-sized worlds that sit further from the star. HD 108874b sits at the Earth’s location of 1au, while the second planet orbits at 2.68au. As gaseous worlds, none of these planets would have a solid surface. However, should they harbour moons, these satellites may well be more carbon worlds.

Rocky recipes

Should 55 Cancri e avoid the fate of a carbon world, silicon would combine with oxygen to form silicate rocks. This initially sounds far more Earth-like. However, it turns out that not all rock recipes are created equally.

Silicates are formed from silicon and oxygen combined with another element. In the Earth’s mantle, that addition is commonly magnesium (although sometimes iron). The exact blend of mineral depends on the relative abundance of magnesium and silicon, expressed as the ratio Mg/Si. The Sun has an Mg/Si ratio of a little over 1, giving roughly equal numbers of both atoms. This produces a mix of pyroxene (one silicon atom and one magnesium per molecule) and olivine (two magnesium atoms to one silicon) through our mantle. Surveys of magnesium and silicon in neighbourhood stars suggest that the Mg/Si ratio is highly variable. This could result in terrestrial worlds made from silicate rock, but with different mineral versions for their interiors.

For an Mg/Si ratio of less than 1, the silicon fraction tops the magnesium. Silicon mops up the available magnesium to form the familiar pyroxene, but the remaining silicon bonds with other minor elements such a potassium, aluminium, sodium and calcium to create a family of minerals known as feldspars. Feldspar is a common mineral in the Earth’s crust, so a magnesium-poor planet might have a mantle made of crust material. On the other hand, if magnesium exceeds silicon then the magnesium-rich olivine and ferropericlase (magnesium and oxygen) minerals are produced.

The reason why all these mineral types matter comes back to the ability of the mantle to move around. A mantle more or less viscous than the Earth’s minerals risks changes to the crustal plate tectonics and volcanic activity to produce entirely different surface conditions. Messing with the mantle recipe is like attempting to make pastry from flour and butter; get the ratios wrong and you may end up with something ill suited to support life.

If 55 Cancri e forms silicates, then its fate may be a sluggish mantle. The star has a measured Mg/Si ratio of just 0.87, making any silicate material magnesium poor. The crust-like composition of feldspars would give the mantle a thick viscous flow compared with the Earth’s rock. This may result in explosive volcanism, as gases are unable to escape the slow gelatinous magma, carrying the molten rock upwards during the eruption.

On the other end of this scale are the magnesium-rich planets orbiting the star Tau Ceti. The system sits 11.9 light years from Earth in the constellation of Cetus, the Whale. As the closest star to the Sun after Proxima and Alpha Centauri, the planets of Tau Ceti have long been ammunition for science fiction.

The existence of the planets is controversial, but there is evidence that five super Earths orbit Tau Ceti. The inner three planets sit close to the star, but the outer two potentially have surface temperatures comparable to those of the Earth. However, Tau Ceti has a Mg/Si ratio of 1.78, making it 70 per cent more magnesium rich than the Sun. If these worlds are rocky, they will harbour magnesium-heavy mantles of olivine and ferropericlase. Unlike feldspars, ferropericlases flow more easily than the Earth’s mantle mix. This could give a more vigorous stirring of the planet’s interior, affecting the movement of the tectonic plates. Alternatively, the magnesium-rich crust may be thick and unable to fracture into tectonic plates at all. If this still produces volcanic activity, the gas will easily escape the freely flowing magma to spawn non-explosive effusive eruptions of lava.

Although we do not yet understand exactly how these different geologies will change a planet, there is a bottom line: an Earth-sized rocky world does not equal an Earth.

Explosive discoveries

The nature of 55 Cancri e continued to niggle at astronomers. Was this a carbon world with a diamond mantle, or a planet with a silicon-rich surface coated with exotic seas of neither liquid nor gas?

The possibilities took an entirely new twist due to fresh observations published by a team from the University of Cambridge in 2016. Training the Spitzer Space Telescope on 55 Cancri, the astronomers examined the light not just as 55 Cancri e transited the star’s surface, but also as it dipped behind the star. Both overlaps between the star and planet result in a drop in the observed brightness. When the planet is neither in front of the star nor behind it, the light observed is a combination of the star and the planet’s own dim radiation. During a transit, the planet conceals part of the star’s surface and the brightness drops. When the reverse happens and the star conceals the planet, a second smaller dip is also seen as the planet’s radiation is obscured. This second transit is known as an occultation, or secondary eclipse.

The light from the planet is from the reflected starlight and the planet’s own thermal radiation. As the planet is colder than the star, the thermal part of its radiation is in the longer, infrared wavelengths that the Spitzer Space Telescope is primed to see. By observing the change in this thermal radiation as the planet disappeared from sight during the occultation, the planet’s temperature could be measured.

Observations of the occultations of 55 Cancri e between 2012 and 2013 revealed something decidedly odd; the thermal radiation from the planet was fluctuating by 300 per cent. The resulting calculated temperature for the planet varied between 1,000–2,700°C (1,800–4,900°F); a massive change of nearly 2,000°C (3,600°F). In addition, the dip in brightness during the planet’s transit in front of the star was also not constant, showing a variation in how much light the planet’s surface seemed able to obscure as if it were changing in size.

These massive fluctuations of incredibly high temperatures suggested a new idea: volcanoes. Bathed in this heat, almost any type of rock would melt. The result would not be a planet with oceans of strange water or tar, but one swimming in magma. With a molten crust, eruptions can violently spew plumes of melted rock up into the atmosphere.

Such activity is not alien to our own Solar System. Jupiter’s third-largest moon, Io, is the most volcanically active world in our planetary system. Volcanoes on the moon spew material more than 300km (190mi) above the surface. So far from the Sun, the energy to melt Io’s lower crust and drive the volcanoes stems from the tidal heating due to the moon’s slightly elliptical orbit. 3 The varying gravitational tugs come from Jupiter and the two neighbouring moons, Europa and Ganymede, which flex Io’s surface and cause it to distort by up to 100m (328ft). This is more than five times larger than the difference in the height of the ocean tides on Earth. On 55 Cancri e, the pull from the star and the neighbouring planets could create a similarly elliptical orbit that flexes the planet and drives some serious volcanic action, in addition to the star’s melting heat.

If the volcanic ejecta were thrown high into the atmosphere of 55 Cancri e, the lower layers of the atmosphere would be obscured. Observations would then detect the higher, cooler parts of the planet’s gases and cooling plume of ejecta to provide a lower estimate of the planet’s temperature. As the volcanic activity eased, the plumes would disperse and the planet’s lower and hotter atmosphere would once again become visible. The measured temperature fluctuation could therefore be due to bursts of volcanic activity. These plumes could also explain the change in the light dip as the planet transits across the star. When the air is thick with volcanic ash, the star’s light is blocked more effectively to give a larger radius estimation for the planet.

To match the observed changes in both temperature and radius, the volcanoes on 55 Cancri e would have to throw material higher than any volcano in the Solar System. For plumes throwing up all over the planet, the average height would need to be of the order 1,300–5,000km (800–3,100mi). If a single massive plume had to do the job, then it would need to be a staggering 10,000–22,000km (6,200–13,600mi); one to two times the radius of the planet. For comparison, Io’s 300–500km (190–300mi) plumes are between 16 and 27 per cent of the moon’s radius. Yet 55 Cancri e is clearly a land of extremes, so perhaps we should expect nothing less.

Should the volcanoes be true, they also cast a light on the planet’s composition. Taking the actual radius of the planet to be the smallest measurement (corresponding to a plume-free atmosphere), the planet’s density becomes consistent with an Earth-like iron and silicate interior, although the planet would still poorly resemble our own, with a surface of melted rock creating a world of molten lava. That said, the volcanic model does not rule out the carbon world or supercritical water envelope. To ascertain that, the content of the volcanic outflows or planet atmosphere would need to be probed.

Nikku Madhusudhan, a member of the Cambridge University team and lead scientist on the suggestion of 55 Cancri e as a carbon world said, ‘That’s the fun in science – clues can come from unexpected quarters. The present observations open a new chapter in our ability to study the conditions on rocky exoplanets using current and upcoming large telescopes.’

Lava worlds

It is a difficult call, but the prospect of 55 Cancri e being a volcanic ocean of lava might be even more hellish than that of a smog-filled carbon world. Yet it was not the first planet to be suspected of possessing an inferno-riddled landscape.

In February 2009, a new planet was reported transiting a star 489 light years away in the constellation of Monoceros, the Unicorn. The planet was denoted CoRoT-7b, named after the French space telescope that made the discovery: the COnvection ROtation et Transits planétaires observatory, or in English, COvection, ROtation and planetary Transits. CoRoT was designed to find transiting exoplanets on short orbital paths lasting less than 50 days; an objective that was satisfyingly fulfilled with the discovery of CoRoT-7b. The planet orbited its star in 20 hours, at just 4 per cent of the distance between Mercury and the Sun. 4

Unlike in the case of 55 Cancri e, the density of CoRoT-7b seemed more easily explainable. The same year as its transit detection, radial velocity measurements estimated the planet’s mass. CoRoT-7b has a mass just under 5 Earth masses and a radius of 1.7 Earth radii to give a density around 6g/cm3. This is a little light for an Earth-like iron core and silicate mantle in a 5 Earth-mass world, but possible if the iron were depleted or the observed radius a slight overestimate. It was certainly too high a density for a gaseous planet, and the measurement made CoRoT-7b the first rocky planet to be confirmed outside our Solar System.

The close density match with the Earth spawned a number of news reports (including – it must be admitted – from NASA), claiming that the new world was the ‘most Earth-like planet’ discovered at the time. While perhaps this was true with regard to its composition, the fact that the planet’s average surface temperature was around 2,000°C (3,600°F) really made the comparison rather poor. If it were possible to stand on the surface of the planet, the star would appear more than 300 times larger than the Sun looks in our own sky. However, the standing part would be difficult because the temperature would have melted a rocky surface to an ocean of lava. CoRoT-7b was not just the first confirmed rocky world; it was also the first lava world.

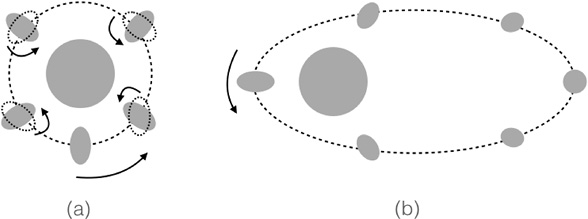

Figure 11 Tidal forces: (a) A closely orbiting planet (or moon) will be distorted by the gravitational pull of the star. The star’s gravity pulls on the raised bulge so the same side of the planet always faces inwards in a tidal lock. (b) Planets on elliptical orbits are flexed as the gravitational pull from the star changes with distance. This causes tidal heating of the planet. (Actual distortion exaggerated.)

Lava worlds such as CoRoT-7b and 55 Cancri e sit so close to their stars that they become tidally locked. Planets in this configuration have one side of their surface always facing their star. Our own Moon is tidally locked to the Earth, so we only ever see half its surface. The first time a human laid eyes on the reverse side of the Moon was during the Apollo 8 mission when the famous Earthrise photograph was captured.

Tidal locking occurs as the planet (or moon) gets distorted by the star’s (or planet’s) gravity. A spherical planet will be pulled into a slightly oblate (rugby-ball) shape by the strong tug of the very close star. As it attempts to rotate, the star’s gravity will drag on the bulge raised on the planet’s near side. This forces the planet to rotate so that the bulge is always facing the star. The result is a tidal lock.

The gravity of the planet (or moon) can also distort the star (or planet). In the case of CoRoT-7b, due to the huge size difference between the planet and star this reverse tug goes unnoticed. On the other hand, the Moon’s pull on the Earth causes both the land and the seas to rise and fall as tides. The Earth’s distortion of the Moon raises a surface bulge of about 0.5m (1.6ft).

If a planet’s orbit is not circular, then the distortion the star induces changes during the orbit as the gravitational pull weakens and strengthens. This causes the flexing that drives the volcanic activity on Io and 55 Cancri e. It may even be happening to CoRoT-7b, due to the presence of a second planet on a more distant orbit. This bigger sibling could force CoRoT-7b’s orbit into an ellipse, causing the planet to flex as it moves further and closer to the star. The surface of CoRoT-7b might then match 55 Cancri e as a volcanic nightmare.

The further apart the star and planet orbit, the weaker this tidal distortion. The drag on the raised bulge is then too weak to create a lock, which is why the Earth is not tidally locked to the Sun. If the two orbiting objects are similar in size, they can be tidally locked to one another. This is the case for Pluto and its large moon, Charon, which face one another like partners in a rumba.

Planets tidally locked to their stars are split worlds, with one side of perpetual day and the other of eternal night. How well heat is distributed between the day and night sides depends on the planet and the ability of its atmosphere to circulate the warmth. Due to the vast distance of CoRoT-7b from us, we are not able to detect its atmosphere or any variations in its temperature. If the atmosphere were able to even out the heat, the surface would be expected to reach about 1,500°C (2,700°F). If the heat cannot be redistributed, then the day side may reach values of 2,300°C (4,200°F), while the night side could sit as low as -220°C (-360°F). This would divide the planet into a lava ocean on the day side and a black rocky landscape on the night side.

The day-side boiling rock may give the planet a tenuous atmosphere. This would be a far cry from our own air, as it would be a gas of vaporised rock. As this rocky gas rose in the atmosphere, it would cool and solidify into a hailstorm of pebbles. The pebble type would depend on the temperature, with different rock compositions solidifying at different heights. The effect would be a giant fractionating column; a planet-sized version of the equipment used to separate out the different components of crude oil using their varying condensation temperatures. Modelling this process at Washington University in the US, planetary chemist Bruce Fegley, Jr described, ‘Instead of a water cloud forming and then raining water droplets, you get a “rock cloud” forming and it starts raining out little pebbles of different types of rock.’ CoRoT-7b appears to lack both a solid surface, and a remotely moderate weather system.

Two years after the announcement of CoRoT-7b, the Kepler Space Telescope confirmed its own first rocky planet find. The world was Kepler-10b. It had the density of Earth-like rock on an orbit of 20 hours. Another two years later and a similarly smouldering rocky Kepler-78b was found, orbiting its star in just 8.5 hours. This class of planet was a subset of the hot super Earths (and smaller) worlds that appeared to have an Earth-like composition but an orbit measured in days. Their molten, potentially volcanic terrain was nothing like our planet. These lava worlds might not have been common, but their numbers suggested hell was to be found in the Galaxy. But it is not only terrestial worlds that have alien natures stemming from their bizarre compositions.

White planet

Astronomers first observing Gliese 436b were initially struck with a similar problem to that encountered with 55 Cancri e; the measured radius did not seem to agree with the mass for any of the usual planet interiors. The planet was 33 light years away in the constellation of Leo, the Lion, and closely orbiting its star in 2.5 days. The mass was found to be 30 per cent larger than Neptune at 23 Earth masses, while its radius was roughly equal to Neptune’s at just under 4 Earth radii. This made the planet too dense to have a large hydrogen and helium gas atmosphere, but not sufficiently dense to be rocky. Instead, the most likely solution seemed to be hot ice.

Like the watery solution to 55 Cancri e’s composition, it seems too bizarre that ice could exist in the blazing heat of a planet 13 times closer (7 per cent of the distance) to its star than Mercury. But compression to high pressures by the planet’s very large mass can create strange forms of ice that stay solid even at surface temperatures of more than 300°C (570°F).

For the planet to have acquired the ice for its bulk, Gliese 436b must have formed beyond the ice line, then migrated inwards. Its envelope of gases must then have evaporated in the star’s heat to leave a thin atmosphere around the ice and rock core, or a layer of the equally strange supercritical water.

Just as the case for Gliese 436b seemed wrapped up, new observational data flung it wide open again. The data for the planet’s size was analysed afresh and Gliese 436b was found to be 20 per cent larger than previously suspected. This made its interior consistent with a more regular Neptune-like gas giant, enveloped in a thick atmosphere.

Yet the planet was not done with surprises. Neptune’s striking azure blue comes from the methane gas in its atmosphere; a molecule made from a carbon atom bonding to four hydrogen atoms. Yet when the Spitzer Space Telescope observed the planet, it saw carbon monoxide, but very little methane. This was mysterious since a gas giant’s thick atmosphere is expected to have plenty of hydrogen to form methane with any carbon atoms. While oxygen is also present, the carbon should preferentially want to form methane at the temperatures expected in the atmosphere. Instead, the carbon had bonded with oxygen to leave the atmosphere with 7,000 times less methane than expected. Why would this happen?

Various suggestions were proposed to explain this phenomenon. Perhaps there was methane in the atmosphere, but its signature was diluted by particularly high quantities of other, heavier molecules. Yet that should lead to a denser planet than had been measured for Gliese 436b. Then, in 2015, a new solution was proposed: perhaps the hydrogen simply was not there.

The idea was that Gliese 436b had begun with a normal mix of hydrogen in its atmosphere, but the close proximity of the star had evaporated the gas. Being the lightest element, hydrogen would have been the most easily stripped of all the planet’s gases. It would have exited, but the planet’s gravity would have held on to the heavier elements. Without hydrogen to form a bond, the atmospheric carbon linked with oxygen to produce carbon dioxide. Meanwhile, the departure of hydrogen would have left behind an atmosphere most abundant in helium. The new helium planet would therefore have morphed into a world unlike those in our Solar System.

Due to the numeracy of Neptune-like planets close to their star, helium planets could be quite common. Rather than losing all their atmosphere or retaining it, hot gaseous planets may selectively lose hydrogen as Gliese 436b does. This gradual stripping would not be fast, taking about 10 billion years; about twice the age of our Solar System. Helium planets would then be the old wanderers in our Galaxy. They would not be blue like Neptune; instead the helium in their atmosphere would appear white.

The strangeness of the exoplanet worlds continued to expand, as was noted in 2015 by planetary scientist Sara Seager, co-author on the paper suggesting Gliese 436b’s helium atmosphere. ‘Any planet one can imagine probably exists, out there, somewhere, as long as it fits within the laws of physics and chemistry,’ Seager said. ‘Planets are so incredibly diverse in their masses, sizes and orbits that we expect this to extend to exoplanet atmospheres.’

It was a statement that would shortly prove true for 55 Cancri e.

The planet without air

Later in 2016, members of the Cambridge group that had proposed the volcanic landscape for 55 Cancri e were poring over their data from the Spitzer Space Telescope. Instead of comparing the dip in heat radiation as the planet vanished behind the star, this time they followed the planet’s dim heat signature through the whole orbit. With one side perpetually facing the star, 55 Cancri e showed its night side to the telescope mid-transit across the star’s surface. As it circled to duck behind the star, the planet turned to expose its day-side face. What the results revealed were two completely different temperatures.

The day side of the planet was around 2,500°C (4,500°F), between the minimum and maximum average values that the astronomers had previously seen. The night side was 1,400°C (2,600°F), lower at about 1,100°C (1,900°F). This still made the night side extremely toasty, but the huge difference indicated that this planet was very bad at sharing heat. On 55 Cancri e, the hot stayed hot and the cold stayed cold.

The huge temperature extremes suggested that 55 Cancri e had no atmosphere. Such a strong change in temperature would have driven winds in an envelope of gases, circulating the heat over to the night side in the resulting gales. Perhaps the planet once had its own air, but the incredibly hot orbit had stripped it down to its rocks.

Almost contrary to this conclusion, the astronomers spotted a further anomaly. The hottest point on the planet’s surface was not directly in the middle of its day side, but shifted to the east. This pointed to at least one mechanism on the planet that was capable of moving heat. A likely culprit would be the lava. Should 55 Cancri e truly be lava world, then the molten rock could flow over to the day side and shift the hotspot. Over on the night side, the rock would solidify and no more circulation would be possible.

This picture fitted the data on 55 Cancri e well: a molten lava world with no air, dual hemispheres of eternal sunburn and engulfing darkness separated by a temperature drop of over 1,000°C (1,800°F). It was not an easy destination to pack a suitcase for, 5 but it was complete. At least, it would have been had not the Hubble Space Telescope found an atmosphere just a few weeks before.

Like the outer layers of a star, atoms in a planet’s atmosphere absorb light. Missing wavelengths in starlight that grazes a planet’s surface act as fingerprints for the gases surrounding the planet. Due to their small size and thin layer of gases, detecting the atmospheres of rocky worlds is a difficult task. To stand a chance, the planet must transit and the star needs to be bright and close. Previous attempts to detect the atmosphere of two other super Earths had been unsuccessful, but in February 2016 that luck changed. Hubble Space Telescope data for 55 Cancri e revealed the first atmospheric fingerprints of a super Earth.

With the telltale pattern of missing wavelengths revealing an atmosphere, how was it that 55 Cancri e had a 1,100°C (1,900°F) dichotomy in temperature? Winds should whip around the planet to redistribute the heat between the scorching day side and cooler night side. One possibility was that the planet had a lopsided atmosphere.

The idea that an atmosphere would concentrate over half the planet seems even more crazy than hot ice or a gaseous liquid water. However, it could occur if the atmosphere were a gas that condensed on the cooler night side. The planet would then be surrounded by vapour on its day side, which rained out as it cooled on the night side.

An example of such an atmosphere would be one filled with vaporised rock. If part of the molten lava on the day side evaporated into the atmosphere, it would condense back out into solid rock on the night side. The fact that this is a possibility emphasises once again the incredible heat of lava worlds. Such a system could even explain the moving hot spot on the planet’s day side, which could be shifted by the day-side atmosphere rather than by lava flows.

This notion was thwarted by the Hubble observations finding an atmosphere dominated by hydrogen and helium. This in itself is a surprise, since these light gases are prone to rapid evaporation. 55 Cancri e was not expected to still be holding on to these primitive gases, which adds to the planet’s ever-expanding mystery. That aside, if these gases are present, they would remain gases at even very low temperatures. There therefore should have been no problem circulating between the two hemispheres of 55 Cancri e.

The only further clue provided by Hubble was the detection of hydrogen cyanide. A favourite poison in Agatha Christie novels when in liquid form, hydrogen cyanide is formed from atoms of hydrogen, carbon and nitrogen. It is possible that this gas may be messing with how the atmosphere circulates around the planet, but currently no one is sure.

Interestingly, the presence of hydrogen cyanide hints at the composition of 55 Cancri e. The hydrogen-carbon-nitrogen combination should only be strongly present in the atmosphere of a carbon-rich planet. This puts the prospect of 55 Cancri e being a carbon world back in the picture. If it is, we can add an immensely poisonous atmosphere to the property description, just in case a diamond mantle still sounded tempting.

55 Cancri e is the planet version of not judging a book by its cover. The frankly horrifying possibilities for its surface conditions demonstrate that an Earth-like size and a Sun-like star are not sufficient to make our home planet. But this is not nearly as strange as we can go. The Sun is not the only type of star in the Galaxy. For one, it is not yet dead.

Notes

1. In Chapter 6, we said a rough rule of thumb was that above a size of about 1.5 Earth radii, the planet was probably gaseous rather than rocky.

2. The rush to park under the one tree in a Florida supermarket car park is real, no matter how far it is to the store’s entrance.

3. We met tidal heating for the puffy hot Jupiter, WASP-17b, in Chapter 5. Due to the planet’s elliptical orbit, the gravitational tug from the star varied in strength, flexing and heating the planet. This is discussed in more detail later.

4. CoRoT-7b is a little smaller than the Sun, but larger than 55 Cancri e. This causes its nearest planet to sit slightly closer than 55 Cancri e, but still have a slightly longer orbital time.

5. Also, your suitcase would melt.