More than 10 years before the first exoplanet was discovered, a telescope was scrutinising the sky for a sign that our Solar System was not unique in the Universe. It was a search that struggled to be taken seriously. The scepticism was not due to scientists thinking that there were no planets orbiting other stars, but because it seemed so incredibly unlikely that they would be found with the current technology.

Planet hunting had so far focused on astrometry; the search for tiny shifts in the locations of stars on the sky that would indicate an orbit with a planet. The problem was that even Jupiter orbiting the Sun at 16 light years away would produce an angular movement of just 0.0000003 degrees. This was about 1,000 times smaller than the resolution of the photographic images of the sky being taken from Earth.

The closest claim to a find was the announcement of two Jupiter-sized planets orbiting Barnard’s star; a red dwarf about six light years away in the constellation of Ophiuchus, the Serpent Bearer. Comparison of the star’s position on photographic plates in the 1960s suggested a 1 micrometre shift in position. However, it was later shown that this movement corresponded to times when the telescope lens had been cleaned; a discovery that underlined how impossible this process seemed.

Looking for the wobble in the star’s radial velocity did not seem more promising. Jupiter creates a shift in the Sun’s velocity of about 13m/s over its 12-year orbit, assuming that the orbit was viewed edge-on for maximum effect. In the 1970s, a star’s radial velocity could only be measured to the nearest 1km/s. This meant that the signature of even Jupiter-sized planets was impossible to detect. Even a hot Jupiter (at the time, an unimaginable entity) would be missed.

The breakthrough in radial velocity measurements was made in the late 1970s by Gordon Walker and his postdoctoral researcher, 1 Bruce Campbell. They proposed putting a container of a known gas between the incoming starlight and the telescope detector. Like a star’s atmosphere, the gas atoms absorb specific wavelengths of light. This creates a fingerprint of dark bands overlaid on the starlight. As the light from the star shifts towards red and blue during the orbit with the planet, the gas fingerprint acts as a stationary point to measure this variation against – like the zero mark on a measuring stick. The big advantage was that both the reference point and the starlight could be recorded simultaneously, avoiding previously large errors due to the apparatus not staying completely stationary between the measurements.

Walker and Campbell originally picked hydrogen fluoride for the reference gas, since it had well-spaced absorption wavelengths that could be clearly distinguished. The disadvantage was that hydrogen fluoride was highly toxic and corrosive, and the gas container had to be refilled after each observing run. Writing an account of the new instrument in a review in 2008, Walker noted that ‘Frankly, it was quite unsafe.’

Unsafe it may have been, but it was successful. The design allowed a factor of a hundred improvement in measuring the radial velocity of stars, giving an accuracy close to 10m/s. Although researchers would eventually swap the dangerous hydrogen fluoride for a gas container of iodine, the precision achieved with hydrogen fluoride would have been sufficient to detect extrasolar planets over a decade before the pulsar worlds. In fact, the failure to do so was to be a very near miss.

The hydrogen fluoride gas container had been installed on the Canada-France-Hawaii 3.6m (12ft) telescope, situated on Hawaii’s Mauna Kea. Assuming detectable planets were Jupiter-analogues on orbits lasting over a decade, Walker, Campbell and fellow astronomer Stephenson Yang surveyed 23 stars for a few nights a year over 12 years. In 1988, the teams reported the results from the first six years of observations. Seven stars hinted at a perturbation by a possible planet, one of which was a star known as γ Cephei. In what would become a standard feature of early planet discoveries, the object around γ Cephei would be dismissed due to being simply too weird.

The observations of γ Cephei revealed it to be a binary star system, about 45 light years away in the constellation of the Greek mythological king, Cepheus. The sibling stars’ orbit was longer than the duration of the planet-hunting survey, so only part of their mutual loop was observed. From this section, the astronomers concluded that the stars took 30 years to circle one another, and there was an additional 25m/s wobble in their motion that repeated every 2.7 years. In their 1988 publication, this wobble was deemed a ‘probable third body’, yet by the survey’s completion in 1995, the tone had become more cautious.

The larger of the γ Cephei pair was thought to be a giant star, expanding as it reached the twilight years of its life. These stellar elders were known for their irregular natures, susceptible to pulsations in their outer layers that look very like the wobble from a planet. The prospect of a planet orbiting a binary star system also seemed unlikely, a feeling compounded by the planet seeming to be a gas giant orbiting much closer to the star than any in our Solar System. With scepticism still running high for planet searches, this world seemed too exotic to be true. It was a wrong conclusion.

A further 10 years later, new observations of γ Cephei showed that the binary orbit actually took twice as long as previously thought, and the larger star had not yet become a cantankerous giant. This erased previous doubts and in 2003, the planet was announced as a gas giant of 3–16 Jupiter masses (depending on the unknown angle of its orbit), orbiting the larger star every 2.48 years at a distance of just over 2au. If the find had been announced in 1988, this would have been the first extrasolar planet discovered. Nevertheless, its discovery pioneered the technique that would find thousands of other worlds.

Figure 14 Formation of protoplanetary discs around binary stars. If the stars are more than about 100au apart, discs can form around both stars, although planet formation may still be disrupted if the stars are closer than about 1500au. At 10–100au, the sibling stars disrupt one another’s discs. A disc may remain around the larger star, or both may be destroyed. When the stars are very close, a circumbinary disc can form around both stars.

Had γ Cephei been an isolated star, the signs of an orbiting planet might have been taken more seriously. But is having a sibling a real problem for planet formation?

In the constellation of Taurus, the Bull, are several hundred newly formed stars embedded in gas clouds known as the Taurus-Auriga complex. With ages of only 1–2 million years, any of these stars planning on forming planets should be surrounded by their dusty protoplanetary discs. A survey of 23 of these young stars that orbited at least one stellar companion revealed that roughly a third were encircled by a disc. This was half the frequency seen around isolated stars. It appeared that a sibling was bad for the planet-forming business, even before the planets had begun to form.

Exactly how bad depended on the proximity of the sibling. Very few protoplanetary discs were seen for stars closer than 30au, with the exception of a few discs that encircled both stars. Conversely, if the stars were further than 300au apart, the disc frequency seemed unaffected by a stellar sibling. In between, the discs were harder to observe, suggesting that the companion star was helping to disperse the protoplanetary disc.

If a sibling stifled protoplanetary disc formation, then it seemed to have an even stronger effect on the growing planets. Examination of stars observed with the Kepler Space Telescope suggested stellar siblings needed to be as far apart as 1,500au before planet formation was unimpeded. Planets existed where the stars were closer, but they were significantly rarer than those around stars that sat alone.

How does the companion star inflict so much damage? A protoplanetary disc forming around a young star in a binary also feels an outward pull from the stellar sibling. This distorts the disc, which bulges towards the second star. Since the disc rotates faster than the binary orbit, the bulge moves ahead of the sibling star. The sibling’s gravity tries to pull the bulge back in line, creating a drag force that slows the disc. As in planet migration, the reduction in speed causes the gas and dust to move inwards and the disc contracts. The result is known as tidal truncation by the companion star. The same dragging effect also occurs on the Earth, due to tidal bulges raised by the Moon. The result reduces the Earth’s rotation very slightly, causing the occasional leap second to be added to our calendar.

Truncating the protoplanetary disc cuts short the time available for planet formation. The more compact disc will sit closer to the star’s evaporating heat and be accreted more swiftly. This explains why protoplanetary discs around binary stars seem to be visible for a shorter time than those around single stars. The proximity of a second star can also raise the temperature of the disc, hindering the condensation of dust to reduce the amount of planet-building material.

For the protoplanetary discs that do survive, the companion star can play havoc with the planetesimals. As the binary pair orbit one another, the second star can pull the forming planetesimals on to elliptical paths that precess like a gyroscope around the host star. The bent paths result in much faster collisions, which can cause particles to fragment rather than stick. This throttles the growth to larger planetesimals and planetary embryos.

These difficulties fuelled the suspicion that γ Cephei could not host a planet. A major concern was whether a truncated disc could even contain enough gas to form a giant-sized Jupiter planet. If it could not, then the observation was probably mistaken. In fact, estimates of the truncation point suggest that there was just enough mass to create the planet, but a second gas giant would be very unlikely.

That γ Cephei’s planet is a gas giant also offers a possible solution to the rapid dispersal of the protoplanetary disc. If the disc was sufficiently heavy, then a planet could form via a disc instability and avoid the problems with destructively fast collisions. The instability might even form more easily in a binary system, as a heavier compact disc has a greater chance of fragmenting and the companion star’s tug could trigger the instability.

But just when there appears to be a workable planet-formation theory for binary stars, a new planet shows up and blows it to pieces. In this case, that planet went by the catchy name of OGLE-2013-BLG-0341LBb.

The planet that bent light

Not only is the name of OGLE-2013-BLG-0341LBb more unwieldy than that of any object met so far, but the planet was also found through an entirely different method of discovery. Rather than detection from the star’s wobble or a dimming in brightness, this planet was found by the gravitational bending of light.

While we do not normally think of light as being affected by gravity, Einstein claimed that rays would follow the curves in space created by massive objects. 2 The analogy is rolling a ping-pong ball rapidly across a sheet depressed by a bowling ball; the path of the light ball will bend around the heavy weight.

This theory was tested for the first time during the total solar eclipse in 1919. British physicist Arthur Eddington realised that the brief obscuration of sunlight by the Moon could be used to see if the Sun’s gravity was bending the light from background stars. If the starlight was being bent, then the stars visible during the solar eclipse would appear in slightly different positions than at night-time when the Sun was not in the sky.

Eddington’s measurements discovered a deflection of 0.00045 degrees, consistent with Einstein’s prediction. The announcement propelled Einstein’s theories into the international spotlight. Despite the excitement, Einstein himself was unmoved by the attention, responding to a journalist who asked how he would have felt had Eddington’s observations disproved his theory with, ‘I would have felt sorry for the dear Lord. The theory is correct.’

The bending of light can give away the presence of a hidden massive object, such as a dim star or a planet. It is a technique known as gravitational microlensing, as the hidden object acts as a lens to bend the light. In a regular lens like that in your glasses, light is bent more strongly at the edges than when passing through the middle. This allows light rays to be focused on to a single point. However, a gravitational lens acts in the opposite direction, bending light that passes close to its centre more strongly than that further away. This results in light being focused on to a ring rather than a single point, to become a bright annulus around the lens known as an Einstein ring. If the lens is extremely massive, such as a whole galaxy, then the ring can be clearly resolved. In the case of a smaller lens like a star, the ring cannot be distinguished. Instead, the background star is seen to brighten and darken as it passes behind the lens, as the ring is more luminous than the background star alone.

Since anything with mass will bend light, a planet orbiting a lensing star will affect the process. This extra mini-lens creates an additional bump in the brightening and darkening of the background source. It was such a bump that revealed the presence of OGLE-2013-BLG-0341LBb.

OGLE stands for the Optical Gravitational Lensing Experiment, forming one of the best acronyms ever created for a galaxy survey. OGLE is organised from the University of Warsaw in Poland, and most of the observations were taken at the Las Campanas Observatory in Chile. While primarily designed to search for dark matter, OGLE has discovered nearly 20 exoplanets. OGLE-2013-BLG-0341LBb was observed while OGLE was hunting for objects in the direction of the galactic bulge, a central region of tightly packed stars in our Galaxy. This location gave the planet the ‘BLG’ part of its name, for ‘bulge’. The ‘2013’ denotes the year in which the observing season began, and the ‘0341’ is just an ordinal number. The last ‘L’ confirms that this was an object found via lensing, to separate it out from a handful of objects OGLE spotted in transit. The capital ‘B’ is because the planet’s star was not alone: it was one half of a very close binary.

The lensing event produced three bumps in brightness as the background star sailed behind this system: two big double peaks from each of the binary stars and a smaller bump from the planet. Analysis revealed that the sibling stars were dim dwarfs orbiting one another at 15au apart; between the distance of Saturn and Uranus from the Sun. The planet orbited one of these stars at a near-Earth distance of 0.8au and had a mass roughly twice that of the Earth. Despite the fact that the planet is a hair-width closer to its star than our own planet, it is much colder. At 10–15 per cent of the Sun’s mass, the dwarf star is around 400 times less bright than the Sun. This leaves its planet a cold, dark world with temperatures likely to be about -213°C (-351°F); colder than Jupiter’s icy moon, Europa. Rocky the planet may be, but it is not Earth-like.

OGLE-2013-BLG-0341LBb might not be similar to the Earth, but it proved that planets could form around a star with a very close sibling. Exactly how the planet managed to gather enough material in such a closely packed setting is open to debate, but there are a number of promising ideas. A simple solution is that the high collision speed from elliptical planetesimal orbits is less of a problem than previously thought. The gas drag may dampen the effect of the second star’s pull to retain the planetesimals in circular orbits. A second option is a mechanism such as the streaming instability discussed in Chapter 2; planetesimals may gather together and collapse under their combined gravity.

Another intriguing possibility is that the binary stars were once further apart. Stars form in clusters, with many stellar neighbours packed close together. This can create star systems with three or even more sibling stars orbiting a mutual centre of mass. Such a system can be unstable, with the multitude of gravitational tugs altering the stars’ speed until the group breaks and ejects a star. The result of giving the runaway star enough energy to escape causes the remaining stars to move closer together. If OGLE-2013-BLG-0341LB was once part of a triplet, then the reduction to a binary could have decreased the star separation from more than 100au to the current close orbit. The planet might therefore have formed relatively unmolested by the companion star and remained in orbit once the stars approached.

Sadly, we may never get another chance to observe OGLE-2013-BLG-0341LBb. The background star and the planetary system lens have now moved apart, and another precise alignment would be needed to see the planet again. We know this cold world is out there, but it may never be spotted from the Earth for a second time.

Despite this lamentable situation, there is another, similar system that we can repeatedly study. It is an exciting prospect, since this planet orbits a binary system that is one of the closest stars to the Earth. The only catch is that the planet may not exist.

Our nearest binary

At just over 4 light years from the Earth, the Alpha Centauri system is our closest stellar neighbour and the third-brightest star in the night sky. While it looks to the naked eye to be a single star, it is actually a triple star system consisting of a close binary and a distant dwarf star. Unlike the hypothetical trio that may have existed in OGLE-2013-BLG-0341LBb’s system, the small size and large distance of Alpha Centauri’s third star allows the system to be stable. The central binary stars are denoted Alpha Centauri A and B, and are approximately the mass of the Sun. They orbit one another every 80 years with an average separation of 11au; just over the distance from the Sun to Saturn. The third star is Proxima Centauri and is the closest of the three to the Earth, but sits at a faraway 15,000au from the binary.

Everyone wants there to be planets around Alpha Centauri. The system’s proximity to the Earth has inspired novelists and script writers to deck the stars with civilisations from the home of the Transformers, Cybertron, 3 to the city that sells the best Pan Galactic Gargle Blaster in the Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy.

The announcement in 2012 that a slight wobble had been detected in Alpha Centauri B was therefore met with great excitement. The variation in the star’s radial velocity indicated an Earth-mass planet orbiting every 3.2 days. While such a short orbit pointed to a molten lava world, its existence meant that planet formation was possible in the Alpha Centauri system, and fuelled hopes that more temperate worlds might exist further out. But not everyone was convinced. The detected wobble in Alpha Centauri B was tiny – right on the edge of what was detectable. Was it perhaps a little too near that edge to be a genuine signature?

To extract the wobble due to a planet from the telescope data, all other influences on the star’s radial velocity must first be removed. The star’s own surface is a major cause of false alarms, with flares and star spots producing their own change in the starlight. In total, these effects are far larger than the variation being sought, so even a small error in their subtraction creates a false positive for a planet.

In a task that must have felt suited to a Devil’s advocate, the data was analysed using a different technique for filtering out the star’s noise. If the planet existed, then its signature should appear through both filter methods. But the planet vanished.

The new results did not completely kill the possibility of a planet around Alpha Centauri B, but they stamped a big question mark on this discovery. Fortunately, unlike with OGLE-2013-BLG-0341LB, the observations can be repeated to collect more data. The current difficulty is that Alpha Centauri A is moving into closer alignment with its twin from our viewpoint on Earth. This means that observers will have to wait for the stars to draw apart once again before we can ascertain if Pan Galactic Gargle Blasters are on the menu.

Searching for Tatooine

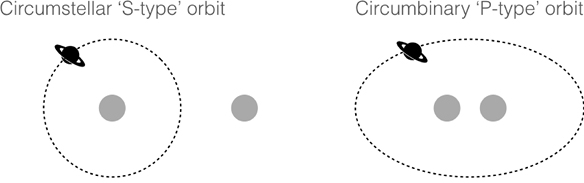

One of the most iconic views in science fiction cinema is the twin suns setting over the desert planet of Star Wars’ Tatooine. Seen together rising and setting, Tatooine does not orbit just one sun, but circles both stars of the binary. This is known as a circumbinary, or P-type, orbit, in contrast with the previous circumstellar, or S-type, orbit, where only one star of the binary hosts the planet. While such planets were only imagined when the Star Wars franchise began, it turns out that they are entirely possible.

Unlike the planets circling single stars, a circumbinary planet orbits further away from the binary pair. This reduces its influence on the stars’ motion, making its presence harder to detect from the radial velocity wobble. Instead, these worlds need to be caught traversing across one of the stars, or by their gravitational pull adjusting the period of the binary’s orbit.

Figure 15 Planet orbits in binary star systems. Planets forming in protoplanetary discs circling one star in the binary end up on circumstellar or S-type orbits. Planets forming in discs encircling both stars orbit on circumbinary or P-type orbits.

In 2011, the detection of Kepler-16b achieved both those feats. The system sits 200 light years away in the constellation of Cygnus, the Swan. The star pair form an incredibly close binary, with a separation of just 0.22au; less than the distance between the Sun and Mercury. Both stars are smaller than our own, at 69 per cent and 20 per cent of the Sun’s mass. So close and dim are these siblings that they cannot be resolved into separate stars. Instead, their double nature is revealed by their eclipsing paths, which cause their combined light to be periodically dimmed as each star alternately dips behind the other.

In observations taken by the Kepler Space Telescope, attention was caught by three additional dips in the stars’ brightness that did not correspond with the stars eclipsing. The extra dimming was a hint of a third, unseen body that was covering a little of the binary’s light. These extra eclipses did not occur at even time intervals, pointing to a circumbinary orbit where the binary’s rotation was shifting the transit time.

Even with thoughts of Tatooine on the horizon, it was not immediately obvious that the mystery object was a planet. It could have been a third star like Proxima Centauri, grazing past the binary as it orbited at a greater distance. This degeneracy was broken by the interloper’s effect on the orbits of the binary pair. Similar to transit timing variations discussed in Chapter 6, the gravity of the third body caused slight variations in when the two stars eclipsed. The size of these changes depended on the mass of the addition. It weighed in as a planet.

This new world had the sky of Tatooine, but it was neither rocky nor hot. Close to the size of Saturn, Kepler-16b orbits the two stars every 229 days. While this gives the planet a year length close to that of Venus, the smaller stars offer scant heat, and the estimated surface temperature is -73°C (-99°F). The transit and eclipse timings revealed both the mass and radius of the planet, producing an average density of 0.964g/cm3. This is higher than Saturn (whose density is 0.687g/cm3), but far too low to make the planet terrestrial. It is possibly a hybrid world, half solid rock and ice, and half thick hydrogen and helium atmosphere.

Kepler-16b should more officially be referred to as Kepler-16 (AB) b, to reflect that it orbits both stars of the binary system. However, since there is no ambiguity when both stars are looped, the ‘AB’ part is typically omitted.

Are planets in circumbinary orbits common, or is Kepler-16b a rare example? At the time the planet was discovered, the latter certainly seemed possible.

As in the circumstellar case, circumbinary protoplanetary discs are subject to the dual pull from two stars. The double tug still risks increasing the speed of planetesimal collisions, grinding down potential new worlds. Additionally, if the planet formed or migrated too close to the binary pair, the changing gravitational forces as the stars changed position in their orbit around one another would vary too strongly to keep the planet’s orbit stable. Instead, the planet would eventually be sent flying into the stars, or out of the system entirely.

Suspiciously, Kepler-16b sits close to this edge of stability. The stars in the Kepler-16 system are also of very different sizes, causing the larger partner to sit close to the binary’s centre of mass. The most massive star therefore only moves slightly during the orbit of its sibling and planet, minimising the changes in the gravitational pull felt by Kepler-16b. This might add up to this circumbinary planet being a lucky chance.

To add to the formation problems, there is the issue of detection. Eclipsing binaries already have a periodic dimming that is far stronger than that created by a transiting planet. Star spots are a further problem, dimming the binary’s light in a way that resembles a crossing world.

Circumbinary planet transits also do not occur at evenly spaced intervals, making it hard to confirm if the dip in light is from an orbiting planet. When circling a single star, the planet’s transit each orbit is highly predictable, so much so that transit timing variations can be used to find hidden planets. However, a planet circling a binary must transit a moving target. The motion of both the planet and binary pair causes the regularity of the transit clock to break. Kepler-16b’s third transit across the brightest binary star was 8.8 days earlier than the time predicted based on the duration between the first two transits. This is an enormous shift, particularly in comparison to the transit timing variations caused by planetary siblings, which are typically just minutes, or at most a few hours.

To cap it all, the planet may not even transit forever. Due to the varying gravitational tug from the looping suns, the planet does not complete its orbit exactly where it started. Instead, its motion precesses, which gradually changes the planet’s path. This can eventually result in it no longer transiting the stars. Models for the long-term evolution of Kepler-16b suggest that the planet will cease to transit the larger star early in 2018, and will begin to transit again in around 2042. The planet stopped transiting the smaller star in May 2014 for a predicted 35 years.

Despite this stack of difficulties, observers continued to search the skies. It was more than the intriguing nature of these double-sun planets that drove the search. The combined measurements from the transit and variations in the eclipses of the binary can give the planet properties to excellent precision. For Kepler-16b, the planet’s mass and radius are each known to a remarkable 4.8 per cent and 0.34 per cent accuracy respectively. Laying hands on such precise data made the search for circumbinary worlds worth the trouble.

As it turned out, the next discoveries were around the corner. Kepler Space Telescope observations of 750 eclipsing binaries on close orbits lasting less than one Earth year were searched for a sign of a transiting planet. The search was a success: only four months after the announcement of Kepler-16b, two more circumbinary planets were discovered.

The two new planets became Kepler-34b and Kepler-35b, both gas giants with masses similar to Saturn’s. Kepler-34b orbits two Sun-like stars that circle one another every 28 days, taking 289 days to complete its year around the pair. Meanwhile, Kepler-35b orbits two smaller stars, each roughly 80–90 per cent of the Sun’s mass. The binary pair orbit one another in 21 days, while the planet circles around in 131 days.

All three circumbinary discoveries had orbits that aligned closely (within 2 per cent) with the orbital plane of the binary stars. This suggested that the planets formed with their stars within a protoplanetary disc that encircled both members of the closely orbiting stellar pair. If the planets had been captured, their orbits would be more randomly inclined, like those of the comets that orbit the Sun. Each of these three systems had only one planet. While this proved that circumbinary planets were possible, could a whole planetary system surround a double sun?

The answer was found the autumn of the same year. Kepler-47 is a binary with one Sun-like star and one smaller sibling a third of the size and only 1 per cent as bright. The two stars are a very closely packed pair, orbiting one another every 7.45 days at a distance of just 0.08au. Initially, the stars appeared to be alone. Their orbital times seemed unmolested by the pull of a hidden body. But the brightness of the stars revealed the shadow of another presence. In fact, there were at least two planets transiting across the larger star.

The lack of a measurable effect on the binary’s motion prevented an estimate of the planets’ mass. It also suggested that these could not be massive Jupiter-sized gas giants whose gravitational pull would affect the binary. Radius measurements from the transits backed this up. The closer planet was three times the size of Earth on an orbit of 50 days. Further from the stars, the second planet was larger at just over 4.5 Earth radii and took 303 days to lap the binary. They were gas planets, but not as big as Jupiter.

The proximity of the inner planet meant that it would be a hot mini Neptune, probably about half the mass of our own Neptune with a thick atmosphere. The second planet was closer in size to Neptune with a more tepid climate. While neither world offered a surface from which to watch the suns set, the presence of at least two planets was evidence that whole systems of Tatooine-like worlds might be possible.

By the start of 2015, a dozen circumbinary worlds had been found. Given how tricky these planets are to detect, it is likely that 10 times as many Tatooine-like worlds are missed in observations. Double sunsets may not be commonplace, but nor are they incredibly rare. However, there were discoveries of both circumbinary and circumstellar worlds that made even Tatooine look mundane.

Methuselah

Kepler-16b is frequently cited as the first Tatooine-like world, but it was not the first circumbinary discovery. Like the earliest exoplanet finds, the first known circumbinary planets orbited dead stars.

A year after Wolszczan and Dale’s discovery of planets around a pulsar, a millisecond pulsar was observed 12,000 light years away in the constellation of Scorpius, the Scorpion. The millisecond spin pointed to the existence of a stellar sibling, and variations in the pulsar’s lighthouse flash were examined for evidence of a companion. The discovery was a white dwarf star and an additional circling planet.

This planet was nothing like the super Earth-sized worlds Wolszczan and Dale had discovered. This was a massive gas giant, two-and-half times the size of Jupiter. Rather than orbiting close to the pulsar, it looped both the pulsar and the white dwarf stellar sibling at a distance of 23au – between the orbits of Uranus and Neptune in our Solar System.

The find tore holes through all the ideas of pulsar planet formation. Protoplanetary discs around pulsars were thought to come from a shredded companion star, yet this pulsar’s sibling was still evidently present. Even if part of its mass could have been ripped away to form the disc, how could such a massive planet form so far away? The planet’s orbit was also inclined relative to the orbit of the two dead stars, suggesting they had not formed together. All this pointed to one conclusion: this planet had been captured.

The pulsar and its white dwarf sibling did not sit in an isolated piece of the Galaxy. Instead, the pair resided in an ancient cluster of stars. When a gas cloud collapses to form a star, it does not birth just a single sun. Instead, the dense pockets of gas fragment into a close group of stars known as a stellar cluster. Clusters range in size from mere tens of stars to ones containing hundreds of thousands of new suns. Forming from the same natal cloud, this stellar family all has the same age, although differences in mass cause their life expectancy to vary. Clusters typically drift apart over time, leaving widely spaced single stars, binaries or small groups. However, the oldest and largest star clusters contain millions of members and retain their densely packed collective. These are known as globular clusters and were formed when our Galaxy was still young. It is in one of these ancient mammoths that PSR B1620-26 resides.

The globular cluster of PSR B1620-26 is named Messier 4. It is one of the easier clusters to spot with a small telescope, appearing as a fuzzy, moon-sized ball close to the bright star, Antares. The cluster has a mass of about 70,000 solar masses in a region 75 light years across, and is thought to be about 12.8 billion years old. If the new pulsar planet originally formed around a young star, then it would be approximately the same age as the cluster and one of the oldest planets ever discovered. This gave the planet the nickname Methuselah, after the grandfather of the biblical Ark-building Noah, who was reported to have lived for a rather unlikely 969 years.

Life within the close-knit star cluster is thought to explain the existence of a planet around a binary of dead stars. The planet could have formed in a normal protoplanetary disc around a young star. During its lifetime, the planetary system moved through the densely packed cluster core. The stars in this region become so close that interactions between stellar neighbours changed from being extremely rare, to very common. In this environment, the planet’s host star drew close to a binary whose stars had already passed the end of their life to become a pulsar and white dwarf. The trio of stars interacted and the white dwarf was replaced by the planet-hosting star. The pulsar was then orbited by a regular star while the planet was jostled outwards to circle the new binary pair.

Finally, the planet’s original parent star reached the end of its life and became a red giant. The giant’s outer layers overflowed on to the pulsar, stripping the giant star to leave behind a new white dwarf. This process did nothing to dislodge the Jovian world, since the star was too small to explode as a supernova. Instead, it became a planet with two dead stars rising and setting in its sky. PSR B1620-26b turned out not to be the first circumbinary born from a star’s death. In fact, it was not even the most strange.

The stars with one body

In the constellation of Serpens Caput, the Serpent Head, 1,670 light years away, is a binary of living and dead stars. This is NN Serpentis; a sibling star system consisting of one white dwarf paired with a regular red dwarf star. The stars orbit one another every three hours and seven minutes at a minute separation of 0.004au. It is a proximity so close that astronomers believe the red dwarf once lived inside its sibling.

While the death of a Sun-like star into a white dwarf is less violent than for its more massive counterparts, it can still be a dangerous time for a sibling. As a dying star expands to a red giant, its outer layers may not only spill on to a close companion but actually envelope it. Like a giant egg with two yolks, one star now sits within the body of the other. The pair are now said to have a common envelope. Inside another star, the orbit of the enveloped star is dragged inwards by the surrounding stellar material. As the orbit shrinks, energy is released that throws out the engulfing layers and exposes the white dwarf core of the red giant star.

Hidden within the folds of a red giant, stars in a common envelope are extremely difficult to observe. However, binaries of a white dwarf with a very closely orbiting companion are suspected of having once shared an envelope. Such is the case with NN Serpentis, whose two stars would have been dragged together during the white dwarf’s bloated red giant phase. Being swallowed whole does not sound conducive to hosting a planetary system. But once again, the Universe did not care.

Like Kepler-16, the NN Serpentis pair form an eclipsing binary, where the stars appear to transit one another as seen from the Earth. Slight variations in when the stars eclipsed forced astronomers to conclude that – as improbable as it seemed – the stellar pair were not alone.

The small variations in the orbit of NN Serpentis were due to two planetary companions. These were massive gas giants, seven and two times the size of Jupiter. They orbited the pair of tight-knit stars much further out at 3.5au and 5.5au, taking 7.7 years and 15.5 years respectively to complete the circuit. Did these planets form with the binary stars, or were they born in the wake of the common envelope being thrown outwards?

The first option suffers from the problems of retaining a planet through a stellar death. While not as violent as a supernova, the loss of the red giant’s outer layers drastically reduced the mass of the binary pair by about 75 per cent. In the case of PSR B1620-26b, such mass loss was avoided by the pulsar accreting the ejected envelope. The less massive stars of NN Serpentis would have lost this material, making it difficult to hold on to orbiting planets. It is therefore more likely that the planets of NN Serpentis are far younger than their stars.

If the castaway envelope of the red giant formed a disc around the binary stars, then a second generation of planets could begin. If this really did occur for NN Serpentis, the two planets are very young. The white dwarf in the stellar pair is extremely hot at 57,000°C (103,000°F), implying that it has had little time to cool since its formation. This puts the white dwarf’s age (and therefore, the maximum age of the planets) at no more than a million years. Such a fast formation time for two gas giants suggests that they did not form via the steady gathering of planetesimals in core accretion. Instead, the planets must have been born in a more rapid disc instability in the shell of discarded stellar layers.

NN Serpentis is an extreme system: planets born in the shredded layers of stars that have shared a body. In fact, the system is so weird that we need to end with a note of caution. Two other extremely close eclipsing binaries have been observed to have similar variations in their transit times. Like NN Serpentis, these was thought to be also due to planets. But examination of the planets’ orbits revealed that they could not remain stable; the worlds would swiftly crash into the stars or shoot out of the system. This suggests that another unknown event had to be responsible for altering the binary orbits. The orbits of the planets around NN Serpentis are stable, but the comparison with similar systems implies that an alternative explanation may still exist. Closely eclipsing binaries could yet hold secrets that have nothing to do with planets.

Cousins

For planets forming around only one star of the binary, the stellar sibling can act as the evil aunt that disrupts the cradle. But is it possible for the binary stars to each host a separate system of planets?

Such cousin planets are possible, but once again depend on the separation between the stars. If the stars are far apart, then planets can form around both stars as if they were single suns. If the stellar pair are closer than about 20au, the gas surrounding the binary will preferentially be drawn around the larger star. Closer still, and the circumbinary Tatooine worlds form. Cousin planetary systems have so far proved to be rare. At the start of 2016, only three, or possibly four, 4 binary stars had been found where both stars separately hosted planets. One of these trio was the particularly intriguing case of the binary WASP-94.

WASP-94A and B sit 600 light years away in the constellation of Microscopium, the Microscope. Observations of WASP-94A showed periodic dips in the starlight, revealing the presence of a transiting planet. The star was being orbited by a hot Jupiter, with an orbital time of just under four days. To find the mass of this new world, WASP-94A was monitored for the characteristic wobble in the radial velocity. This was found, but a second wobble in the star’s sibling was also detected. WASP-94B was also orbited by a second hot Jupiter that did not transit the star.

The two binary stars orbit one another at a distance of 2,700au. Such a large separation should mean that the stars had no effect on the planets forming around their sibling. The presence of the two hot Jupiters might therefore have been interesting but unremarkable, if it were not for the planets’ unusual orbits.

Forming out of the natal gas cloud together, the stars’ spin and the orbit of the binary and planets should all rotate in the same plane and direction. Instead, there was an angle between the orbits of the two planets that caused only one of the cousins to transit. Moreover, that transiting planet was found to have a retrograde orbit, circling WASP-94A in the opposite direction to the star’s spin.

We have seen such misalignments before. Chapter 5 described how a stellar sibling could flip a planet to create a hot Jupiter with an inclined or retrograde orbit. It could be that WASP-94A and B are too far apart to interfere with their sibling’s planet formation, but could still turn a planet on its head. Alternatively, these cousins might once have been planet siblings orbiting just one star. A close interaction between the two planets might have booted one of the pair over to the other star. There could also be other unseen planets in the system that sent the hot Jupiter around WASP-94A on to a tilted orbit. At the moment, the family history of these cousins remains a mystery.

Worlds of many suns

As the Alpha Centauri binary and distant Proxima Centauri demonstrate, the sibling stars are not limited to pairs. It is unlikely that more than two stars would be close enough to be encircled by a single circumbinary disc, but planets on circumstellar orbits could find their skies lit with a multitude of suns.

Like the Centauri trio, HD 131399 is a triplet star system that sits 340 light years from Earth in the constellation of Centaurus, the mythological half-human, half-horse Centaur. The group is also split into a binary and single star, but that is where the similarities with our nearest neighbours end.

The single star in HD 131399 is the most massive of the three, with 80 per cent more mass than the Sun. The binary pair consist of a Sun-sized star and a dwarf that orbit around their heavyweight sibling like a spinning dumbbell. The single star and the binary pair are separated by 300au, and sitting between them is a plus-sized Jupiter world.

The Jovian gas giant orbits the massive singleton star at a distance of 82au; roughly twice the distance from the Sun to Pluto. This equates to a staggering 550 Earth years to complete one orbit. If it were possible to live on a moon around the planet, entire generations of humans would live and die during a single one of the planet’s century-long seasons. The planet is so far from any of the three stars in the system that its presence was not detected by transit or from changes to the stellar motions. Instead, HD 131399Ab was directly imaged.

Figure 16 HD 131399Ab orbits the largest star in a triple star system. The second two stars form a binary that also orbits with the largest star.

Forming from violent impacts or rapidly collapsing gas, planets are born hot. Normally, this heat is obscured by the blaze of the star. But if the planet is big enough, young enough and far enough from its sun, then this heat signature can be detected. How hot the planet is depends on its age and mass. Assuming the age of the system is the same as that of the star, this allows the mass of a directly imaged planet to be estimated from its temperature. Direct imaging is a rapidly growing technique in exoplanet studies, but it remains hugely challenging for even the best telescopes. At four Jupiter masses, HD 131399Ab was one of the lowest-mass planets imaged at the time of its announcement in 2016.

For about half of HD 131399Ab’s multi-century orbit, all three stars would sit close together in the sky. Triple sunsets and sunrises would mark each day. During the second part of the year, the stars would appear to draw apart until the rising of the primary star would coincide with the setting of the smaller binary pair. For approximately 140 years, the planet would have no real night-time. Yet despite always having a sun (or two) in the sky, HD 131399Ab would not be brightly lit. The distance to these three stars is so great, that even the massive primary would be about 1/600th the brightness of the Sun; appearing as a small but very bright point of light. The binary pair would form a double but even fainter glow.

Writing for Slate online magazine, astronomer and science writer Phil Plait speculated on the course of a civilisation developing on such a world. Would such a civilisation ever assume a Ptolemaic model with the heavens rotating about its planet, when an obvious counter example sat as binary suns in its own sky?

So far out, it is unlikely that HD 131399Ab formed near its present orbit. It is possible that the system has other, unseen planets that scattered the gas giant on to its current path. Alternatively, HD 131399Ab may have been a circumbinary world around the dumbbell binary, and was scattered either by the stars or a planet. The bizarreness of this situation further demonstrates that stars are excellent planet factories under any conditions.

In the constellation of Crater, the Cup, 150 light years from Earth, is a quadruple star system. HD 98800 consists of two binary star pairs orbiting one another at just 50au like, waltzers in a fairground ride. Such a close distance is the equivalent to four suns being packed into the Solar System between our Sun and the Kuiper belt. While no planets have been detected in the system, one pair of binary stars is surrounded by a circumbinary debris disc.

Debris discs consist of the dusty fragments formed during the planet-forming collisions, like sawdust in a furniture factory. Unlike protoplanetary discs, they appear at the end of the planet-formation process. The warm dust allows the discs to be spotted from their infrared radiation by instruments such as the Spitzer Space Telescope.

Around this unusual binary, Spitzer revealed a debris disc in two halves. The outer section sits nearly 6au from the encircled binary pair, while the inner part stretches between 1.5 and 2au. Between these two sections was a gap.

This space could indicate an unseen planet. The hidden world would mop up the smaller rocks in its orbit, creating a cleared section in the debris. This is not the only option, however, since the collisions that produced the debris might never have formed a planet-sized world. Instead, the largest objects would be asteroid-sized rocks. The gap might then have resulted from the combined gravitational tugs of the four close suns. However, if the planet does exist, it would see four suns in the sky. Two of these would be slightly further then the Sun from Earth. The other two would sit at roughly the orbit of Pluto.

Even more complex systems may still be out there. In the constellation of Ursa Major, the Great Bear, 250 light years away, is a five-star system. The quintuplets are split into two sets of binaries and a single star. Meanwhile, the constellation Gemini, the Twins, contains the bright star, Castor, which shines with the combined light of six stars. While no planets have been observed in these systems, they would have skies that even fiction has not imagined.

Notes

1. A postdoctoral researcher is a junior researcher who has recently completed their doctoral thesis.

2. We met this idea in Chapter 8, talking about the generation of gravitational waves as massive objects creating ripples in Einstein’s rubber-sheet universe.

3. In Marvel comics, Cybertron was ejected from the Alpha Centauri system to become a rogue planet. Chapter 11 considers these orphan worlds.

4. The question mark here is Kepler-132, where it is not clear which star the binary’s four planets orbit.