CHAPTER 7

Alcohol and Burning Pyres

When scholars study a thing,

they strive to kill it first, if it’s alive;

then they have the parts and they’ve lost the whole,

for the link that’s missing was the living soul.

GOETHE, FAUST, PART 1

The culture of the Middle Ages is the result of a successful synthesis. The ideas that came with the Christian missionaries and had seemed quite strange at first had by then been successfully integrated and incorporated into the worldview of the indigenous Germanic-Celtic forest peoples. As far as the medical system was concerned, there had been a reconciliation of the conflicting approaches. The nature-bound, indigenous, healing lore of the herbalists and the medicine of the cloister brothers and sisters had fused into a harmonious amalgam, or at least into an acceptable agreement and mutual understanding. This was reflected in the work and influence of the abbess, Hildegard of Bingen, who carried on in a similar spirit as clairvoyant wise women had always healed.

This balance was also reflected in the Gothic church architecture, which had begun during this time. The halls held aloft with high colonnades with their bold ribbed vaults and the light gently surging through the lancet windows almost gave the impression of forest silence. The cathedrals were, so to say, the rebirth in stone of the hallowed halls of the beech or oak forests that were sacred to the ancestors. The acoustics of the organ and polyphonic chorales, already introduced at that time, were close enough to the murmur of the gods in the sacred groves when the wind was blowing through the treetops. Ever more, the massive Romanesque churches, based on the Mediterranean model of damp, cool caves, were abandoned. In the hot Mediterranean where the sun can sting mercilessly, the gods had revealed themselves since ancient times in stone grottos, but in the north it was in the forest where one was close to God.

Professionalization

Alas, no sooner had the foreign influence been assimilated than the wind shifted again. A paradigm shift took place from the eleventh century onward. Again, the new cultural impulse came from the Middle East. One year after the birth of Hildegard of Bingen, the crusaders conquered Jerusalem and liberated the Holy City, including the Holy Grave.

Thereafter, contact with the Arab-Islamic world naturally grew in intensity. Shortly before these events, the learned North African doctor and drug trafficker Constantine the African (1017–1087 CE) appeared in the hospice in Salerno, which belonged to the Cloister Montecassino. As a baptized lay brother, the native Tunisian translated the Arabic writings of Avicenna, Rhazes, Ibn al-Baitar, and other Islamic scholars) as well as the lost (but preserved in the Islamic world) ancient Greek scriptures, into Latin.1 Arabic writings were also translated in Moorish Spain at the University of Toledo. What came to light struck like lightning in the medieval world. Like hungry wolves, Western scholar monks pounced on the classical knowledge that had recently been made available again, particularly on Aristotle’s and Persian-Arabic scholars’ less lofty and less spiritual, but more objective, perspective on natural history.

Mineral remedies—alum, antimony, lead, iron sulfate, verdigris, lime, calcium carbonate, chalk, salt, copper ore, sodium carbonate, sulfur, sulfide, and other inorganic chemical substances—played a far greater role in Islamic medicine than in the West; perhaps this was so because the desert has less vegetation. In Arabic medicine, the plants themselves were not so much seen as independent, responsive beings one could talk to, but as carriers of material forces (virtutes). These material forces can be extracted and transferred into elixirs, electuaries, pills, syrups, and other medicinal preparations (Stille 2004, 38). The aim of Arabic medical practitioners was to look for essences; they wanted to get rid of the rough fabric of impurities and slag (faeces). It was based more on a materialistic perspective.

Alchemical processing of medicinal plants

Arabic alchemy, dissolve and coagulate (solve et coagula), came into fashion with the monks. They experimented, boiled, baked, calcined, distilled, filtered, and sublimated. It was the beginning of the laboratory and of modern pharmacy. Very important was distilled alcohol, the spirit of wine (spiritus vini), the “fire water” (aqua ardens). This alcohol (spiritus), extracted as the essence of the crude plant mass, was practically seen as a panacea. It can especially alleviate the “cold” ailments and also serve as a solvent for precious exotic healing spices, such as cardamom, ginger, galangal, nutmeg, clove, and cinnamon. The monks and scholars were very enthused about all of this. Liqueurs, brandies, and herbal brandies became the monopoly of many monasteries. Uroscopy, bloodletting, cupping therapy, pulse taking, laxatives, purgatives, the making of electuaries (thick liquid medicine) and theriacs (pharmaceutical panaceas), Iatro astrology, and so on became part of medical science.

Yes, the wind had changed. The medical school of Salerno was revolutionary. An international scholarly elite gathered there. The founders’ legend tells of four doctors, a Christian Orthodox Greek, a Jew, an Arab, and a Latin Christian who joined together in order to exchange views on the accumulated knowledge from India to Spain. In Salerno, anatomical experiments were done on pigs. Exceptional was also that women were admitted to the school, albeit only a few. Only one is actually recorded, namely medical doctor Trotula who hailed from a well-to-do family. She turned to gynecology, which had been left to primitive, illiterate midwives for centuries and wrote a scholarly work on the subject. Historians are not sure, though, if she was really a man who had given himself a fictitious name.

What took place in Salerno makes the hearts of many of today’s enlightened contemporaries leap for joy. These medics were doing the job properly! What was developing there was encouraged and legally protected by emperor and pope. The Stauffer Emperor Frederick II issued a comprehensive set of laws (1240 CE), which led to the professionalization of physicians and pharmacists. No one was allowed to practice medicine who had not studied at a university for five years, taken three years of logic, and completed a one-year internship with an established physician. The future physician’s knowledge of anatomy and the scriptures of the old masters, Hippocrates and Galen, had to be examined, by decree, by masters from Salerno (Schipperges 1990, 181).

The laws served to protect patients from charlatans and incompetent medical practitioners, who could neither understand humoral pathology nor draw logical conclusions. Pope John XXII and Paris Bishop Etienne joined the decree and also prohibited the practice of medicine by illiterates (ignari), herbal healers (herbarii), and old women (mulieres vetulae) (Chamberlain 2006, 44). With this, the rustic healers, leeches, wortcunners, midwives, and wise old women were decreed obsolete; they were considered illegal and henceforth liable to persecution. In their place appeared the Greek iatros (“medical practitioner”), the fidicien (“physician”; from Latin, “practitioner of natural science”), and the Latin medicus (“healer”), as well as the Latin doctor (“teacher”). As members of an independent profession, these physicians were no longer subject to the rules of celibacy but were permitted to marry and have families.

The new rules on professionalization also affected the mild-mannered monks. In various councils, such as the Council of Tours (1163 CE), they were forbidden to practice medicine. Priests, monks, and nuns should henceforth be restricted to their primary responsibilities, namely to see to the salvation of their flock. Monastic medicine came to an end. However, the monks were still allowed to produce medicines. And this they did; they busied themselves with the production and “examination” of various alcohols and distilled spirits, potions, powders, and the like.

Also during this time, apothecaries were established and regulated, and the practice of regular physicians was legally separated from that of surgeons. Now doctors alone were responsible for internal medicine and the prescription of pharmaceutical remedies (polypharmacy). The less prestigious, less educated barbers (surgeons) were responsible for bloodletting, pulling teeth, applying leeches, administering enemas, scraping out fistulas, sewing wounds, cupping therapy, and scarification.

The new regulations and laws had dire consequences for illiterate peasant healers, especially for the gifted women healers. Healing and herbalism, which had fallen within the range of female activity since time immemorial, had become a domain dominated by men.

Heretics

Just at this time, a heretical movement began to discomfort the Roman Catholic Church. The apostates called themselves Cathars, the “pure” (Greek katharos = pure), which became Ketzer (heretic) in German. They saw themselves as the only true Christians (veri christiani). They practiced austerities and nonviolence and shamed the official Church and their secular clergy with their demonstrative virtuous conduct. They accused the Church of being too lax, unclean, unholy, and full of pagan practices. They rejected the idolatry of worshiping the cross, graven images, and saints; they rejected the doctrine of hell and purgatory: the material world in which we live, is in itself hell and Satan its master. They rejected baptism, marriage, and the Eucharist.

In addition, the Cathar worldview was strictly dualistic; that is, they divided the world into good and evil, light and darkness, spirit and matter, the kingdom of God and of Satan. In their view, the Catholic Church obviously belonged to the latter. Of course, this all went too far—the Church’s reaction was to come down on the heretics, who had settled primarily in southern France, with full force. The pope called for a crusade against them. Under the leadership of the Dominicans, the Inquisition, a system of spying, torture, dispossession, and death by burning at the stake, was set up against them. The burning of the heretics could be biblically justified. Did Jesus not say, “If anyone does not remain in Me, he is like a branch that is thrown away and withers. Such branches are gathered up, thrown into the fire, and burned” (John 15:6)?

Spurred on by the Cathars, the Church tightened their ideological reins. All at once, Satan played a major role in theology. He was no longer the ordinary devil, the cloven-hooved, hairy, gaunt, nature spirit with horns that a clever farmer could outwit; he was also no longer the “poor devil” that a bishop could force to build a bridge. He was now “Lord of the World” and a veritable anti-god.

Even after the heretics were long eliminated, the Inquisition continued to exist as an institution. It was used against “witches,” the last carriers of shamanism, which was very dangerous for the village healers and leech doctors, especially when they were more successful than the professional doctors, as was often the case. Successful healers got the full force of the law thrown at them. After all, only Satan could be responsible for their success!

Pestilence and Syphilis

In the fourteenth century, the medieval climate optimum came to an end. It gradually grew colder and the weather became unstable. Climatologists speak of the “Little Ice Age” between 1350 and 1800. The winters were longer; chestnuts, figs, almonds, and wine disappeared from northern Europe; grain acreage decreased; and there were crop failures, famine, and social unrest. Beggars and robbers made the roads unsafe. Flagellants traveled across the country, whipping themselves bloody in order to obtain God’s grace.

Due to the wet and cold weather, rye, which thrives in a colder climate better than wheat does and was the most important grain for baking bread, was suddenly seized by the ergot fungus (Claviceps purpurea). Because they were hungry, however, people did not stop baking bread, and the result was a pandemic ergot poisoning. Symptoms were convulsions, respiratory and circulatory disorders, and—because of the LSD-component of the fungus—crazed hallucinations. Because of circulatory disorders, fingers and toes turned black and rotted off as if they had been burnt by fire. It seemed as if an army of demons had fallen upon mankind. The infestation was called St. Anthony’s fire because only St. Anthony, the holy Egyptian hermit who himself had been attacked by hordes of demons and resisted them, could help.

The Temptation of Saint Anthony (Albrecht Duerer)

The long, cold winters and insufficient food led to weak immune systems and susceptibility to various epidemics, including the plague. The pope and the emperor blamed the people themselves for their misery; their immoral and sinful life was responsible for God’s punishment. They should buy indulgences. But above all, it was the fault of the witches, these covert heathens, who practiced harmful magic. And so witch persecution increased; the Inquisition had a new task. While the executed heretics had been both men and women, now the “witches” were mainly women, the heiresses of the old heathen seers, also traditionally called Walas, Voelvas and Veledas. By burning them at the stake, the cultural inheritance, the shamanic knowledge of healing and magic, were also burned, whose roots reached back to the Old Stone Age.

When the Black Death epidemic raged and wiped out one-third of Europe’s population, the learned doctors were at their wits’ end. Their visits to their patients were now called “death runs.” In long leather garments that covered the whole body, with beak masks filled with aromatic herbs, with gauntlets and goggles meant to protect against infection by visual contact, they visited the sick. Bloodletting was the primary means of medical science because it was believed to guide the bad humors out of the body. Theriac, a broad-spectrum panacea made from expensive exotic spices, opiates, powdered toads, snake venom, and mithridate (a universal antidote also made of bizarre ingredients) should “master” the “pestilential poison.” Perfumed smelling “apples” called pomander (small, hollow metal balls full of herbs) containing amber, civet, aloe, dittany, myrrh, and pimpernel were another medical remedy (Porter 2003, 127). Still other doctors prescribed brandy and other spirits for their patients. Houses were fumigated, and quarantines were enforced. This was how the Great Tradition reacted to the crisis.

Dance of Death as imagined during the time of the plague and famine (woodcut from the Nuremberg Chronicle, 1493)

For its part, the Church offered the frightened people the so-called pestilence saints, whose intercession should mitigate the scourge of God. The most important was Saint Roch, who had indeed himself suffered from the plague and had been healed. Saint Anne, the mother of the Mother of God, the grandmotherly being who had once replaced Mother Hulda (and was now the patroness of the miners just as the Paleolithic goddess had been responsible for the netherworld), should likewise be appealed to with consecrated “Saint Anne water” and pilgrimages to churches under her patronage. Saint Sebastian, who was studded with arrows, and the two divine physicians Cosmas and Damian were also part of what the Church officially had to offer. These were other answers from the Great Tradition.

In the Little Tradition of the common people, victims turned to local herbs and relied on revelations from the otherworld. Whenever people are at the extreme limit of what is tolerable and in the greatest danger, the veil that separates the everyday world from the supernatural world becomes very thin. In such times, nature and forest spirits come closer. Herbal women and simple farming folk now heard, in many places, angels, gnomes, talking birds, sea mermaids, moss dwarves, and various wee people who gave them good advice.

In the Giant Mountains, the mountain spirit Ruebezahl stepped out of the forest and told an exhausted and helpless forest farmer:

Cook saxifrage and valerian, so the plague will have an end.

In the Salzburg area, a bird called from a tree:

Eat juniper and burnet, then you die not so fast!

In St. Gallen, a mysterious voice said,

Burnet and masterwort are good for pestilence!

Dozens of such sayings have been recorded by folklorists. And if they are analyzed closely, they are always plants, especially the roots, that are not only rich in vitamins and have a vitalizing effect but also possess a strong immune-boosting component (Storl 2010a, 240). They include, first of all, saxifrage (Pimpinella saxifraga), angelica (Angelica sylvestris), masterwort (Peucedanum ostruthium), juniper (Juniperus communis), and the carline thistle (silver thistle, Carlina acaulis). Even ransoms, or bear’s garlic (Allium ursinum), tormentil (Potentilla erecta), valerian (Valeriana officinalis), and forest sanicula (Sanicula europaea) are frequently mentioned. According to modern phytotherapeutic criteria, these plants can be classified as more effective than the means of the Galenic academic doctors.

For the West Slavs, such as the Sorbs, it was similar. Here, too, voices were heard from the otherworld: “You shall need valerian, dorant [not clearly identified, possibly horehound, snapdragon, or some other plant], and frankincense.” A young girl listens to a bird sing: “Valerian, valerian, valerian.” It is said that all recovered who drank valerian afterward. If the plague threatened the Sorbs, they put out all fires, took an oak board and a thick spruce board, and rubbed them against each other until the spruce began to smolder and catch fire. With this fire, a so-called need-fire known since pagan times and which always signaled a new beginning, the plague then disappeared. Houses were also incensed against the plague—among others plants, juniper, elecampane root, oak leaves, birch bark, and even the hair of an uncastrated billy goat were used (Lehmann-Enders 2000, 34–35).

In 1492, yet another contagion was introduced when the ships of Columbus returned to Europe and brought syphilis. The European population had no natural immunity against this sexually transmitted, infectious disease. The victims rotted alive, and the nobility and the clerics were severely affected. Whole monasteries were depopulated; kings and princes succumbed. The common people, who had relatively strict customs and also lived a basically clean life, were less affected. All the stops of conventional medicine were pulled, but the Hippocratic-Galenic humoral teachings failed, and no cure was found. Even conventional herbs did not really help. Although the Caribbean indigenous peoples knew an effective cure with blood-purifying plants, such as guaiacum (Guaiacum officinalis) or sarsaparilla (Smilax officinalis), combined with a special diet and frequent sweat baths, the Europeans had no understanding of such “savage practices.” While it was previously believed that for every disease, there is a healing herb, the medical profession began to lose faith in the efficacy of herbal medicines.2

The modern medicine of the day found an answer in the so-called Saracen ointment which the crusaders discovered during their stay in the Middle East. This ointment consisted of mercury and other highly toxic mineral substances—and it seemed to help. Mercury was also administered internally in the form of calomel, or Mercuris dulcis. Even though the patient suffered severely and had adverse side effects due to mercury poisoning—salivating, drastic diarrhea, and later suppurating ulcers, kidney and intestinal inflammation, hepatitis, and hair and tooth loss3—mercury was considered a miracle drug, similar to penicillin, chemotherapy, and radiation in our age.

Doctors now prescribed, for those who could afford it, mercurial preparations for everything: asthma, colicky babies, gout, jaundice, madness, cancer, rickets, rhinitis, smallpox, and so on. To numb the pain that accompanied this therapy, laudanum, an opium preparation, was prescribed. Since opium paralyzes intestinal peristalsis and causes constipation, enemas and strong laxatives became necessary. (Bloodletting was still practiced because the “bad fluids” had to be flushed out.) This “heroic medicine,” as it came to be called, was considered modern and scientific. The old herbal women could not keep up, and their “superstitious” knowledge was no longer in demand. On the contrary, it was ridiculed and increasingly punishable. The climax of the syphilis epidemic in the mid-seventeenth century was also the peak of witch persecution.4

In the eighteenth century, a clean sweep was made: it was the time of the Enlightenment. Only that which could be scientifically proven and based on accurate empirically supported observation and measurement and did not violate the laws of logic was considered real and substantial. Anything else was regarded as subjective, illusory, or simply superstitious. “Witches” no longer existed; if anything, they were henceforth declared poor, deranged old women. The witch hunt was passé. Anna Goeldin of Glarus was the last witch beheaded in Switzerland in 1782 for allegedly killing a child by conjuring pins into its milk. The very last execution of a witch in Europe took place in 1793 in Poznan (Poland).

And as little as it was believed in this new enlightened age that there are witches, wizards, elves, mermaids, or ghosts, no one believed in the effects of healing herbs and incantation. Medicine had become a rational science. Healing was now in the hands of men who were scientifically trained and rational. Even gynecology, obstetrics, and neonatology were now a matter for the doctors; midwives were only reluctantly tolerated as unskilled helpers. Chemical-pharmaceutical agents that can be dosed precisely replaced the herbs of the wise, old women. Sometime later, bourgeois women fought for the right to study and to practice the medical profession. This is good in itself, but basically they assumed a medical practice that is masculinized and in which all uncontrollable elements—vision, inspiration, intuition—are kept at a minimum.

In the countryside, far from enlightened city society, folk medicine lived on happily, with its herbal agents, healing incantations, and other so-called superstition. These rural folk used the same tried and true medicinal plants that their ancestors had always used. Monastic medicine had also left its mark. Not only were traditional teas, decoctions, powders, and ointments still made, but the old herb women who lived in virtually every village now also healed with herbal tinctures and spirits and made decoctions in wine, sweet electuaries, and ointments with olive oil. Again and again, herbal medicine revivalists, such as the brilliant doctor Christoph Wilhelm Hufeland and Father Sebastian Kneipp, who came from the simplest circumstances in Bavaria and whose family could not afford doctors, drew from the ancient traditions. Also herbalists, such as Maria Treben and Maurice Mességué, brought traditional knowledge into the modern age and traditional healing back to modern consciousness.

Arabic Influence in Medical Vocabulary

A new worldview requires a new vocabulary. The strong impression that Islamic medicine made on Western medicine from the twelfth century can be clearly seen if we bring the many concepts to mind that found their way into the language of scientific medicine and pharmacists.

Alchemy (Egyptian-Coptic kami, chemi = black, black earth): Arabian alchemy, material metamorphosis, the attempt to change ignoble, “sick” metals, step by step, into elixirs, or even gold, is the legacy of Ancient Egyptian culture. The transformation process that took place during certain constellations at exactly the right time included procedures such as distillation, crystallization, and sublimation. In the course of time, exact weights and measuring methods were developed, and new materials were discovered, such as hydrochloric acid, sulfuric acid, nitric acid, ammonia, alkalis, many metal compounds, ether, phosphorus, Prussian blue, and so on.5 Alcohol and minerals became part of medicine, of iatrochemistry. This new empirical direction of research fascinated the European clerical elite. It is the cradle of modern chemistry.

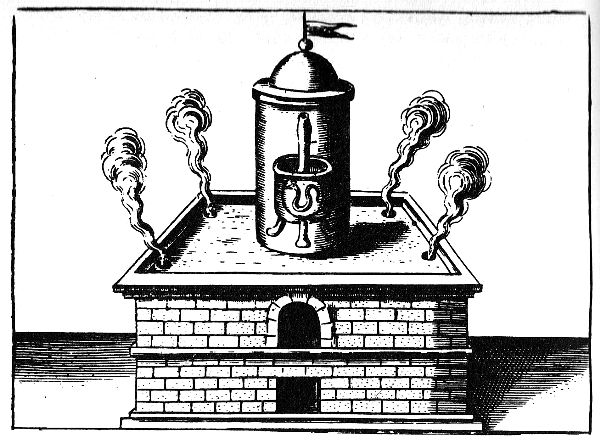

Athanor, an alchemical sand bath oven (Museum Hermeticum, Frankfurt, 1678)

Alcohol (Arabic al kuhl = eye powder, antimony): The fine antimony powder was used as black eyeshadow and as a medical treatment for the eyes. The Spanish alchemists transferred the concept of the finest powder to the finest distilled spirits: aqua vitae (the water of life) and aqua ardens (distilled liquor), which represented the quinta essentia (quintessence) of the wine.6 The famous Dominican and doctor, Arnold de Villanova, introduced “fire water,” or “spiritus,” as a medical panacea in the thirteenth century. After that time, alcoholic distillations were fervently produced in European cloisters, and not a few men of god became alcoholics.

Alembic (Arabic al-inbīq = distiller): The device that made it possible to distill alcohol and produce essential oils and perfumes.

Alkali (Arabic quala = roast): The word refers to roasted, saline beach plants out of whose ashes alkali (potash, sodium carbonate, etc.) can be gained.

Amalgam (Arabic amalal-ğamā a = work of fusion): This word, well-known due to mercury dental fillings today, refers to metal alloys with mercury. Mercury alloys played a major role in alchemical medicine.

Amulet (Arabic hammāla = a band to wear): An amulet is a pendant, which was spoken over with incantations or Koran verses to keep evil genies (djinns = bad spirits) away.

Aniline (Arabic an-nil = indigo plant; originally from Sanskrit nila = blue): Synthetic indigo was produced in the mid-nineteenth century by BASF (the multinational chemical-manufacturing company) from coal tar and used as a basis for many dyes, plastics, and drugs.

Antimony (Arabic intimid = stibnite): The Benedictine alchemist monk and alchemist Basilius Valentinus was very enthused about this silver-white lustrous metalloid. He heard that pigs eat it to purge themselves; then, he tried it on his fellow monks, who promptly died. Even Paracelsus still believed that antimony is the strongest arcanum, if alchemically refined, and would transform an impure body into a pure one, such as with leprosy.

Artichoke (Arabic al-haršūf = goad, prod): This vegetable from the subfamily of thistles that the Moors imported to Europe was already used early on in Arabic medicine for liver and gall ailments. The root contains cynarine.

Benzine (a corruption of the Arabic lubān gāw = incense from Java; Catalan benjuyn; Middle Latin benzoe): Benzine resin was used as a healing means for chest ailments, catarrh, and abscesses. In the nineteenth century, the distillation of benzoin resulted in “gasoline,” a word that came to be used for fuel for machines.

Bezoar (Persian bādzahr = antidote): This preventative and remedy for poisoning consists of the stomach stone of ruminants or hair balls from cat guts and was very popular with princes and cardinals in medieval Europe. They often wore them on pendants and dipped them into their beverages to neutralize possible poisons.

Bismuth (Arabic itmid = antimony): A chemical element with symbol Bi in the periodic table. The Arabs once also used this brittle white, silvery substance medicinally.

Boron, borax (Arabic būraq = borate sodium): The Egyptians already used this mineral for embalming. Medicinally, it acts as a disinfectant.

Camphor (Arabic kāfūr, from Sanskrit karpūra): In India, the fragrant white resin from the camphor tree is lit up, burning with a clear, white flame, and used when worshipping the gods. When the Muslims discovered it, they used it for washing and embalming of the dead and in medicine for nosebleeds, diarrhea, eye diseases, gout, and as an anti-aphrodisiac. Hildegard was enthused about “Ganphora” that strengthens a feverish patient as “the sun brightens a cloudy day.” Camphor, she said, “is so pure that witchcraft and delusions cannot manifest; instead they disappear in the face of its purity, as snow melts away in the face of the sun” (Riethe 2007, 383).

Cotton (Arabic bitāna = inner lining of garments): Loose mass of soft cotton fibers.

Elixir (Arabic al-iksbī = philosopher’s stone, dry substance with magical properties; originally from the Greek xēríon = dry healing substance): It is one of the key words of alchemical medicine; it is the fifth essence, a life-supporting and life-extending substance. In Europe, one began to call herbal substances extracted in alcohol “elixirs.”

Galangal (Arabic halanğān): This plant from the ginger family grows in South Asia; it found its way to the Arab markets and pharmacies, has an antispasmodic effect on the digestive system, and is anti-inflammatory and stimulating. Hildegard of Bingen was highly enthused and prescribed the exotic root for everything from back pain, bad breath, hoarseness, and hearing disorders to spleen ailments.

Gauze (Arabic qazz = raw silk): Gauze is the thin, loosely woven fabric that is used for wound care.

Julep (Arabic gulāb = rose water, refreshing drink): In Europe, this drink of distilled water and syrup became a popular way to take medicine. We know the word as the refreshing mint julep in the hot south of the United States.

Kandis (Arabic qand; Punjabi khanda = an angular stone): Rock sugar, as well as crystalized sugar, was an expensive commodity that the Arabs brought from India and was used in many medicinal mixtures, such as syrup and electuaries. The modern word candy for confectionery goes back to it.

Massage, massage (Arabic massa = to touch, to feel; from the ancient Greek mássein = to knead): The treatment of touching or stroking out a disease is of course one of the oldest methods of therapy. However, this specific word was brought to the European languages by travelers to the East.

Mummy (Arabic mūmiyā’ī = earth pitch, bitumen, asphalt; from the Persian mum = wax): Embalmed body parts used as medicine (see page 238).

Myrrh (Arabic murr): The resin of the myrrh bush, which grows in southern Arabia, is regarded as precious incense. We know it from the story of the Three Wise Kings from the East, who bring the Christ child myrrh, frankincense, and gold. The ancient Egyptians used the resin along with soda to embalm corpses; the Arabs used alcoholic tinctures of it to make the gums firmer and to treat asthma, lung disease, worms, digestive ailments, and more. Hildegard saw the expensive imported good as a means against magic and satanic influences, but also as effective for fever and migraines.

Natron (Arabic natrūn; from the ancient Egyptian ntr.j): In British English, natron refers to the deposits of soda ash and sodium bicarbonate, which are chemically identical to soda and essential in preparing mummies. Today we know it as baking soda, as part of the effervescent powder used for neutralizing excess stomach acid. Arabs used it as an antiseptic and water softener.

Potassium (Arabic al-qalya = potash, ash salt): The element potassium, an alkali metal, is important in plant growth and living bodies to help maintain blood pressure and metabolism in the bones. The symbol for potassium in the periodic table is K, which refers to kalium, a word still used in British English and also comes from the Arabic al-qualya, meaning potash or “salt of ashes.” Potash is essential in maintaining blood pressure, fluid balance, transmission of nerve impulses and the metabolism of the bones. Potassium was used for these purposes in Arab medicine.

Safran (Arabic za’farān): These orange pistils of a kind of crocus are a luxury (150,000 blossoms produce one kilogram of saffron); the plant was used by the Arabs for coloring and seasoning, but also for healing and as a cosmetic and an aphrodisiac.

Soda (Arabic suuwād = salt plant ash): Sodium carbonate, soda water.

Sugar (Arabic sukkar; as a loan word from Sanskrit sákara = grit, grains of sugar): The “white gold,” especially that extracted from sugar cane, was recommended by Arab physicians as a remedy and was part of electuaries and syrup.

Syrup (Arabic šarāb = potion): Syrup is thickened sap with sugar, honey, or molasses. In Islamic medicine, remedies are often administered as syrups.

Talc (Arabic talq = talc, steatite): Powdered soapstone, used as talcum powder.

Plant Names from Arabic

The following words (originally from Arabic) for plants, spices, and preparations show what an impression the Arabic scholars made on European doctors, pharmacists, and scholars: aloe, barberry, borage, ebony, tarragon, galangal, harmal (wild rue), hashish, senna, ginger, jasmine, coffee, camphor, carob, calico (cotton), kermes (cochineal), kiff (cannabis resin), cumin, cubeb (pepper), turmeric, lime, loofah (sponge gourd), marzipan, myrrh, orange, saffron, salep (“fox testicles,” boyhood herb), safflower (false saffron), sandalwood, senna, sesame, spinach, sultana, sumac, tamarind, teak, zedonary (bitter root), plum.