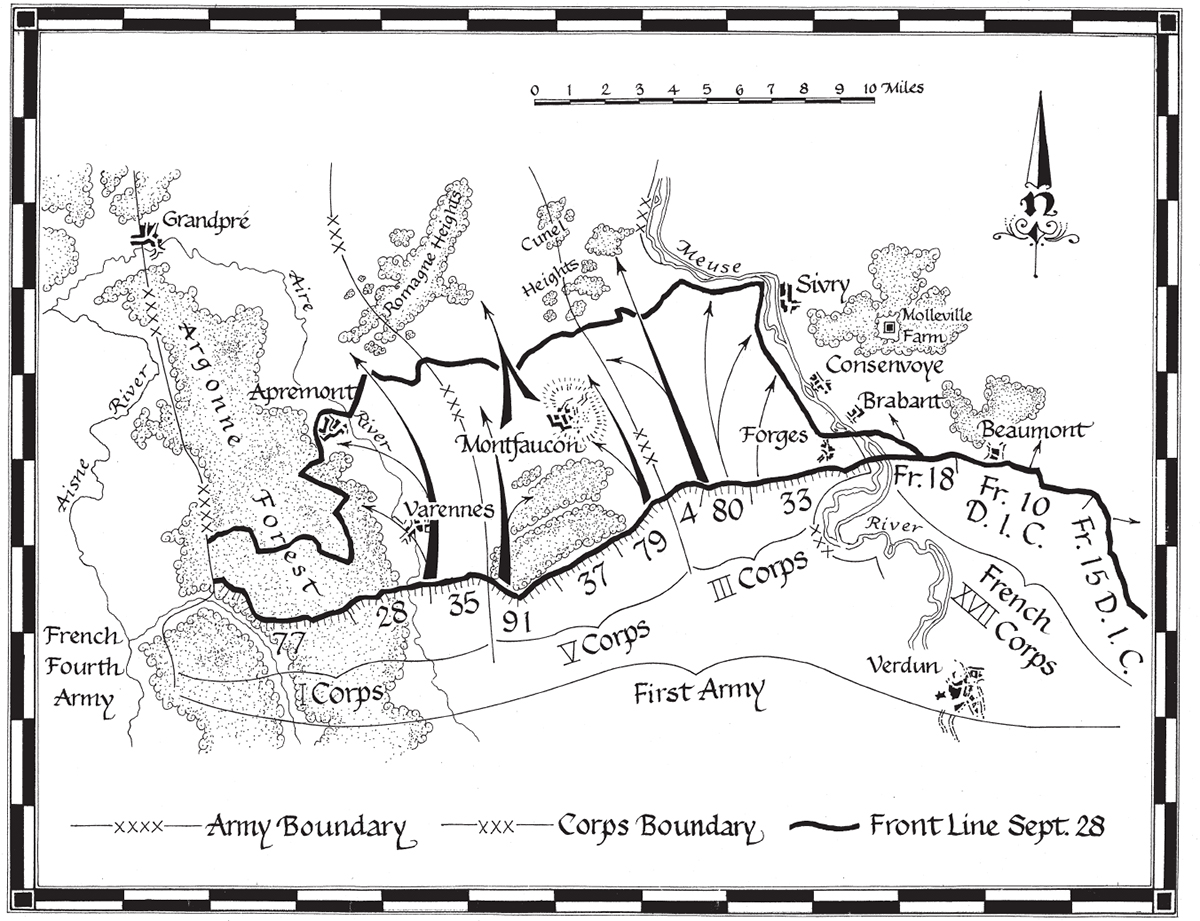

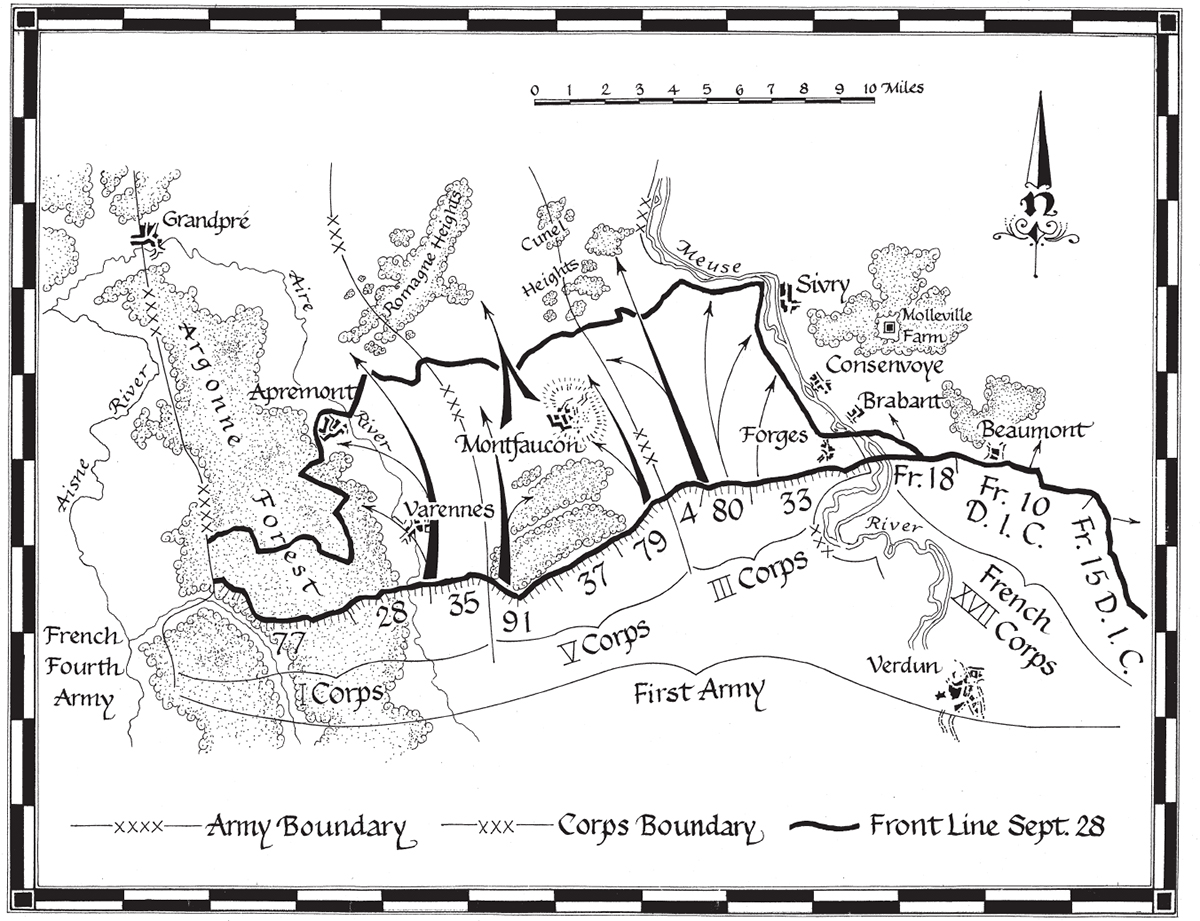

ALIGNMENT OF US DIVISIONS FOR THE MEUSE–ARGONNE ATTACK, SHOWING PLANNED ADVANCE, SEPTEMBER 26, 1918

CHAPTER 7

FIRST ARMY TAKES THE FIELD

The events of spring 1918 changed the Allies’ strategic thinking. Until Foch took over as commander-in-chief, strategy was left to the commanders of the individual armies—in the case of the French, Pétain. Having held the line at Verdun and brought the Army back from mutiny after the failure of the Nivelle campaign, Pétain adopted a strategy of strictly limited offensives while waiting for the Americans to arrive in force. Foch, finally invested with overall command, replaced the Army’s defensive strategy with an offensive one, after concluding that Pétain’s incremental methods could not end the war any time soon.* Once the Spring Offensives had been contained, Foch recognized that the Germans had made themselves vulnerable by abandoning their former defensive positions and supply depots and distributing their forces over a broad front; it was time to attack. At first Pétain resisted Foch’s direction, but Clemenceau intervened and made it clear who would be in charge. Pétain thereupon acceded and on July 12 issued Directive No. 5: “Henceforth the armies should envisage the resumption of the offensive ... They will focus resolutely on using simple, audacious, and rapid procedures of attack. The soldier will be trained in the same sense and his offensive spirit developed to the maximum,” so that he would be suited for rapid advance in open country. Pétain prescribed training so as to instill a “spirit of maneuver and an aptitude for movement;” clear, concise orders that left the details of execution to the individual unit commander; surprise; rapid execution and deep expansion of the attack; and exploitation, both immediate and long-distance.1 If this wasn’t open warfare, nothing was.

* As early as January 1, 1918 Foch had written to General Maxime Weygand, his chief of staff: “We must respond [to an enemy offensive] ... with an attitude that will comprise, for the armies of the Entente, the resolve to seize every occasion to impose their will on the adversary by retaking, as soon as possible, the offensive, the only means that leads to victory ... In case of an enemy attack, [the Allied armies must] not just stop him and counter-attack on the same ground as his attacks, but, more, must undertake powerful counter-offensives of disengagement on terrain chosen and prepared in advance, executed as rapidly as possible.” (Ministère de la Guerre, Service Historique, AFGG, Tome Vi, 1er Volume, Annexes – 1er Volume (Paris: Imprimerie Nationale, 1920–38), p. 410.)

A second development finally gave Pershing what he wanted—an American army. Foch had agreed to this in principle in late April, but it was a minor concession at the time; Pershing had already consented to lend his divisions to the French and British to repel the German offensives. In mid-June Pershing thought the time had come to consolidate his forces, but Foch proposed instead that he assign some of the best trained US regiments to depleted French divisions, to be returned in early August. Pershing refused. At a conference at Bombon on July 9 Pershing brought up the issue again. Now Foch agreed the time was right. From the Americans’ minutes of the meeting:

General Foch says he wishes to express his satisfaction about the fact that General Pershing’s views on the situation are so much like his. He is going to be still more American than the Americans. It is, in his opinion, absolutely necessary to organize the American troops in American army corps and armies, with a view to operate them in an American sector on an American battlefield ... One million Americans are now in France. It is the absolute right of the American army to play, as an army, a role corresponding to the above figure.2

Foch proposed to put American divisions still lacking their artillery into quiet sectors or training areas, and Pershing agreed. On July 24 Pershing ordered the formation of the American First Army on August 10.

The next question was where First Army would serve. Pershing had addressed this soon after arriving in France, his main consideration being that the location should accommodate a force of several million men comprising a unified American army. The left wing of the line was unsuitable because the British needed to protect their supply lines through the Channel ports. The French had to occupy the center of the line, because they needed to defend Paris. The right portion of the front, located in Lorraine, offered opportunities. It was generally quiet and uncongested with troops and offered areas for billeting and training. It gave potential access to ports on the Atlantic and the Mediterranean, so that the Americans’ supply lines would not conflict with those of the British. Furthermore, those lines would run south of Paris and would be less vulnerable to a German advance, an important consideration if the Americans were to take over a greater load from a depleted French army. And there were attractive strategic objectives. The sector included the St Mihiel salient, a wedge that protruded into the Allied lines for 15 miles and obstructed the Paris–Nancy rail line. Just north of the front lay the Longwy–Briey iron mines, the Saar coal beds, and the critical rail hub of Metz. From Lorraine the US could deliver a decisive attack that would disrupt the enemy’s logistics along the entire front, forcing them to retreat to the German border or even the Rhine.3

Historians have criticized the strategic basis for placing the AEF in Lorraine. The resources of Longwy–Briey and the Saar basin were not critical to the German war effort; they provided only about 10 percent of its raw materials. The critical railroads that supplied the German divisions ran not through Metz but through Thionville, some 18 miles further north, requiring a much more ambitious offensive to disrupt.* The Germans had held Metz since 1870 and had spent the time installing elaborate fortifications around the city itself and in the surrounding countryside. The Woëvre plain, which the Americans would have to cross to get to Metz, was filled with impediments to the free movement of troops: poorly drained, clayey soils laced with small streams and ponds, and surrounding heights that allowed the Germans to overlook the entire region. Perhaps a reason Foch readily agreed to put the AEF in Lorraine was one that would have been obvious to any French officer who looked at a map: there were no important strategic objectives behind the American lines to tempt Ludendorff into a full-scale assault against Pershing’s inexperienced and half-trained army.†

* Alan Millett points out that the German rail network is shown correctly in Vincent J. Esposito, ed., The West Point Atlas of American Wars, Volume II: 1900–1918, vol. 2 (New York: Henry Holt, 1959, reprinted 1997), map 68; Historical Division, USAWW, vol. 1, p. 26; and in several German sources. The maps in Pershing, My Experiences, show the main lateral line running from Metz to Sedan, which is wrong. (Millett, “Over Where?” p. 252.)

† The Paris–Avricourt rail line, which ran behind the American position, was already cut by the Germans at Château Thierry and was within range of their artillery at St Mihiel.

The issue of where the Americans would fight arose again with a vengeance in mid-August, just as Pershing had taken command of First Army. So far, Allied counterattacks had been local, aimed at reversing the German salients gained in the Spring Offensives. Around August 16, Haig convinced Foch to switch from local attacks to a general offensive against the entire German line from Verdun to the sea—itself one huge, westward-bulging salient. He proposed that the British continue their action at Amiens by attacking eastward toward Cambrai, to sever the German lateral rail supply line near Maubeuge. The French and Americans would mount a converging attack on the south face of the German position west of the Meuse, also cutting the railroad that supplied the German armies and interfering with Ludendorff’s ability to move reserves to meet the British. This would force Ludendorff into a general withdrawal from the Hindenburg Line, the great, 200-mile-long trench system that had anchored the German position in northeast France since early 1917. In the context of such an operation, a sustained assault beyond St Mihiel toward Metz made no sense; instead of converging, it would deviate from the axis of the British and French advances. Haig’s plan therefore reduced to eight divisions the American forces for attacking St Mihiel, making an advance on Metz impossible.

From the beginning of his tenure as commander-in-chief, Foch envisioned a joint attack by the French and the Americans. In his notes from the Bombon meeting on July 10, Fox Conner, Pershing’s Assistant Chief of Operations, reported that the French command insisted that, “[t]o bring about a certain spirit of emulation, considered (by Foch and Weygand) as essential in securing the necessary coordination, the attacks must be launched in the same general region with interdependent objectives ... The vital spark of emulation would misfire should the plan be an attack by the Americans in Lorraine while the French and British attack in the north (Weygand).”4 Foch clearly wanted the Americans to emulate the French, not trusting the newcomers to know their business. Pershing, either naïvely or (more likely) deliberately, neatly turned this back on Foch:

[T]he most valid of the reasons advanced by General Foch and General Weygand in support of the practically continuous front of attack is to be found in the idea of securing emulation between the several armies. The very distinct impression left on my mind by the conversation of both General Foch and General Weygand was a doubt on their part of the ability of both the French and British [to] attack unless carried along by the enthusiasm of Americans acting in the same region against common objectives. If such were the fact it would perhaps be sufficient reason for adopting the proposed plan. [Emphasis added.]5

Thus Foch and Pershing reached agreement in fact while diverging by 180 degrees in principle.

On August 30 Foch met with Pershing at Ligny-en-Barrois (First Army headquarters since August 29) to present his version of Haig’s plan. Foch wanted the French Second Army to attack northward between the Meuse and the Argonne; the American First Army between the Argonne and a line west of the Aisne; and the French Fourth Army west of that. He wanted four to six American divisions to reinforce the French Second Army. This would have broken the American forces into three groups: a small one to attack the southern flank of the St Mihiel salient; one with the French Second Army; and the main body operating up the Aisne. Each American force would be separated from its fellows by French units. Pershing reacted negatively: “This virtually destroys the American Army that we have been trying so long to form.”6 This was an exaggeration, but the plan did move the Americans westward away from their supply lines, hospitals, training centers, and other support facilities. The discussion became intense. At one point Foch asked, “Do you wish to take part in the battle?” “Most assuredly,” replied Pershing, “but as an American Army.”7 Two days later Foch proposed that First Army execute a limited operation to reduce the St Mihiel salient, then redirect itself northward to a sector between the Meuse River (on the east) and the Argonne Forest (to the west) to participate with the French in the main assault. The St Mihiel attack would start on September 10 using eight to ten divisions; the Meuse–Argonne offensive would begin sometime between September 20 and 25 and would occupy 12–14 divisions. Pershing agreed; he would not get his attack on Metz, at least not soon, but he retained control of a unified American army.

Pershing’s acceptance of Foch’s counterproposal for St Mihiel overcommitted the Army. In the words of Donald Smythe, Pershing’s biographer:

An American Army, untested and in many ways untrained, was to engage in a great battle, disengage itself, and move to another great battle some sixty miles away, all within the space of about two weeks, under a First Army staff that Pershing admitted was not perfect and, as of this date, had no inkling that an operation west of the Meuse was even contemplated. Army staffs normally required two to three months to form a fully articulated battle plan with all its technical annexes; this staff—and, again, it must be emphasized that it was new, inexperienced, and untested—would have about three weeks. It was a formidable commitment, not to say impossible, and it is not clear that Pershing should have made it.8

But the alternative was to attack north with the St Mihiel salient remaining to threaten the American rear. Nevertheless, the Army suffered consequences from this decision for the rest of the war, particularly as it prevented most of the best divisions from participating early in the Meuse–Argonne offensive.

Having won his chance at a purely American offensive, Pershing now had to deliver. The V-shaped St Mihiel salient, about 15 miles deep, protruded southwestward into the American lines. Pershing’s plan called for three divisions, comprising IV Corps, to attack the south face with a further four divisions in support, while the three divisions of V Corps attacked the west face with three divisions in reserve. His force included his five most experienced divisions—the 1st, 2nd, 4th, 26th, and 42nd—some of which would therefore be unavailable for the opening of the Meuse–Argonne offensive. In all, the attacking forces numbered 550,000 American and 110,000 French troops, opposed by 23,000 Germans and Austrians, representing seven vastly understrength divisions.9 The attackers were supported by 3,000 guns, 267 tanks, and 1,400 airplanes, all of them borrowed from the French.*10

* First Amy’s lack of artillery, transport, and aircraft arose directly from Pershing’s agreement, at the frantic behest of his allies, to ship only infantry and machine gun units during the Spring Offensives. In the words of David Trask, “Pershing never came close to completing his design for a completely independent army. He depended heavily on the Allies for support in deficient categories until the end of the war.” (Trask, AEF and Coalition Warmaking, p. 101.)

Pershing’s preparations included a generous helping of deception. Registration fire was prohibited; the artillery was to use mass of fire and aiming by use of map coordinates to suppress enemy guns.† In early September, three officers from each of six divisions—the 79th among them—were dispatched to Belfort, 100 miles south in Alsace, to conduct “reconnaissance” and thereby to convince the Germans that the true attack would fall there. (Pershing’s staff were probably hoping they would be captured. They weren’t, and the Germans weren’t fooled, although Kuhn and several other American generals assumed that was where their divisions were to be sent.11) And the general made sure to exhort his commanders to observe the principles of open warfare, despite the fact that this was to be essentially a set-piece attack. His Field Order No. 49 directed that “penetration will be sought by utilizing lanes of least resistance in order to cause the fall of strong points by out-flanking.” Any “success” in the attack was to be “vigorously exploited,” although just how this was to be done was not described.12

† Registration was the practice of firing a few shells in advance of the real bombardment, having air reconnaissance report where they fell, and correcting aim accordingly. It generally tipped off the enemy that an attack was coming.

The attack jumped off on September 12, the first day that American forces fought as a unified army. It was a walkover. Unknown to the Americans, the Germans had ordered that the salient be evacuated beginning on September 10. As a result, few German guns were in place, and those that were lacked ammunition. The remaining German troops were more interested in getting away than resisting, which kept American casualties to only 7,000. Four hundred and fifty guns and 16,000 prisoners were taken. Achieving all of its objectives in four days, the attack liberated 200 square miles of French land, opened the Paris–Nancy railroad, protected the right flank of the future Meuse–Argonne assault, and provided a staging area for possible attacks on Metz, the Longwy–Briey industrial region, and the railroad supplying the German Army to the northwest. It also demonstrated that the American Army was capable of full-scale operations.13

Although the Germans officially pooh-poohed the American victory, pointing out that they were abandoning the salient anyway and that the withdrawal had been orderly, the German High Command was in fact upset. General Max von Gallwitz, commander of the army group defending St Mihiel, wrote, “I have experienced a good many things in the five years of war and have not been poor in successes, but I must count the 12th of September among my few black days.”14 Pershing was ecstatic, seeing the victory as confirmation of his doctrine: “For the first time wire entanglements ceased to be regarded as impassable barriers and open-warfare training, which had been so urgently insisted upon, proved to be the correct doctrine.”15 Even his allies were impressed. The salient had been held by the Germans for four years and the French had failed twice to take it. French officials, including President Raymond Poincaré, rushed to visit Pershing and congratulate him. Premier Georges Clemenceau had less luck; Pershing allowed him to advance only as far as Thiaucourt, 25 miles behind the lines, but could not prevent him from seeing the congestion on the roads.16

That congestion was a symptom of three problems that foreshadowed greater troubles to come. The first was transportation and supply. No measures had been taken to ensure smooth operation of the transportation system. The staff had failed to determine correctly the capacity of the roads and the drivers, particularly the French ones, had failed to maintain road discipline. The engineers had poorly organized the supply of laborers to repair the shell-shattered tracks. As a result, traffic jams lasted for days. Major General Ernest Hinds, chief of the AEF’s artillery, wrote in a memorandum to Hugh Drum, Pershing’s Chief of Staff:

There was ignorance and lack of discipline shown in the management of our traffic. The regulations are not understood by drivers and traffic police and are not carried out with sufficient rigidity in many cases when they are understood. Truck trains halted with proper intervals between sections would soon be filled up solidly by chauffeurs [staff cars] working their way forward. Then if a single vehicle of the column going in the opposite direction happened to have an accident, there would be a complete blocking of the traffic for a time.17

Clemenceau, stuck in his traffic jam, was appalled by the confusion. He later wrote, “They wanted an American army. They had it. Anyone who saw, as I saw, the hopeless congestion at Thiaucourt will bear witness that they may congratulate themselves on not having had it sooner.”18 Whatever the presenting symptoms, the situation was the inevitable result of trying to cram some half-million men with their equipment, transport, and supplies into a triangle roughly 20 miles on a side.

Many weaknesses in American training and staff work also emerged. Riflemen couldn’t tell their own planes from the Germans’. They did not use cover when advancing against machine guns and, when retiring, remained upright. Rolling barrages advanced too slowly for the infantry, failed to use direct observation in favor of map direction, and wasted ammunition. Men on the march straggled, particularly when stopped. Mounted men, halted in traffic, remained in the saddle instead of dismounting to rest their horses and themselves. “Animals were misused, abused, or not used at all.” Commanders failed to re-establish communication by horse relay once telephone lines were cut. French liaison officers reported that American commanders did not appreciate the value of armor and, believing in the irresistibility of an American assault, failed to soften up the German positions with artillery. They followed regulations to the letter and were incapable of improvisation when new situations arose. They neglected to establish fixed command posts, and those that they did set up were too far to the rear, making effective command and liaison impossible. Orders often were far too wordy, complex, and redundant to be understood or even read.19 As a result of the road situation clothing and food were insufficient, and the tanks were held up by a lack of fuel for 32 hours.

The third area of deficiency was the artillery. Once the rolling barrage had ended, the artillery support on the first day was unsatisfactory. Batteries had great trouble moving forward over the torn-up ground, and those that did displace forward had trouble setting up their telephone lines. They were thus out of touch both with their regimental headquarters and with the infantry command posts that could tell them the positions of the troops in the front line. As a result, German artillery and machine guns were free to pound the US troops all afternoon. Although their French instructors had trained the American gunners in how to use their weapons, they did not train them in tactics. Not being skilled in rapid target acquisition and preparatory bombardments, the American gunners left many German batteries untouched and pounded many unoccupied positions to a pulp. The difficulty of moving artillery and ammunition forward, of communicating with the infantry, and of determining the position of the front line all indicated that a continuation of the St Mihiel offensive, had Foch allowed it, would have been possible only after prolonged planning and preparation or at the cost of greatly increased casualties.

These problems boded ill for the American participation in Foch’s planned offensive. None were insurmountable, given time to train, reorganize, and re-equip; all armies had faced them at various points in the war. But between the end of the St Mihiel operation and the start of the Meuse–Argonne offensive, First Army had ten days.

Many of the American commanders whose troops flattened the St Mihiel salient thought that Metz was the great piece of unfinished business. The night after the operation ended Brigadier General Douglas MacArthur, a brigade commander in the 42nd Division, went through the German lines and observed the fortress of Metz from several miles away through binoculars, concluding that it was “practically defenseless.” (How he could tell at that distance that the largely subterranean trenches and fortifications were undefended is a mystery.) He asked that his brigade be allowed to attack, promising he would be in possession of the town “by nightfall”; he was turned down.20 Colonel George C. Marshall, on Pershing’s planning staff, also thought the city could be taken in a day or two. But Major General Hunter Liggett, a veteran artilleryman who would soon take over command of First Army, disagreed; only a thoroughly experienced army could take the fortified town, and even so would most likely get bogged down on the Woëvre plain for the winter. *21 In fact, the situation behind the former St Mihiel salient was very dangerous for the Germans. The fortress of Metz had been stripped of much of its artillery, leaving it exposed. The Germans were amazed that the Americans didn’t take advantage of their initiative. But the issue was moot; Pershing, pressed by Foch, had already committed to redirect his troops northward for the Meuse–Argonne offensive.

* In World War II it took Patton’s XII Corps 14 days (November 8 through 22, 1944) to secure Metz, starting from positions less than ten miles to the west; the final assault itself took six days. Three days were required to take Fort St Julien, an old seventeenth-century fort defended by 362 Germans without heavy weapons. (Stephen E. Ambrose, Citizen Soldiers: The U.S. Army from the Normandy Beaches to the Bulge to the Surrender of Germany (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1997), pp. 161–65.)

Foch’s overall plan was to give up hope of a breakthrough battle, which always ended in the attacker bogging down on the ruined battlefield and the defender using superior lateral transport to reinforce the threatened area. Instead, he designed a series of offensives all along the front to take advantage of the numerical superiority provided by the Americans, use up the Germans’ reserves, and give them no time to regroup. In the words of Donald Smythe, “Unlike Ludendorff, Foch had the genius to finally see that a decisive, war-winning breakthrough was chimerical, for the defense could always move its reserves by rail and truck more quickly than the offense could move by foot, especially over devastated ground.”22 He therefore devised the following series of operations:

1.On September 26, the French Fourth Army and the American First Army would attack northward toward Mézières and Sedan. The Americans would operate between the Meuse River (to the east) and the Argonne Forest (to the west), the French west of the Argonne.

2.A day later, the British would attack toward Cambrai with two armies comprising 27 divisions.

3.The day after that, the Belgians, French, and British in Flanders, at the extreme north of the German position, would stage a joint attack toward Ghent with a total of 28 divisions.

4.Finally, on September 29, the French and British would attack the center of the German line between Péronne and La Fère.23

Thus, all 200 miles of the enemy front would come under attack, although in staggered fashion so as to keep the Germans off balance. The first of these assaults was put under the command of Pétain, the French commander-in chief, who would coordinate the actions of the French Fourth Army (under General Gouraud) and the American First Army (under Pershing).

Pétain issued his instructions on September 16. He called for a three-phased attack converging on Mézières: Operation B, the American attack between the Meuse River and the Argonne Forest; Operation C, the advance of the French Fourth Army in region Argonne Forest–Reims; and Operation D, the attack of the French Fifth Army between Reims and the lower Aisne River. (Operation A was the St Mihiel offensive.) B and C would take place on September 25, D on September 26. He described the goals of the American attack:

An operation called B, carried out between the Meuse and the upper course of the Aisne, by the American First Army, designed to gain possession of the Hindenburg Line on the front Brieulles-sur-Meuse–Romagne-sous-Montfaucon–Grandpré, with subsequent exploitation in the direction of Buzancy-Mézières in order to outflank the enemy line Vouziers-Rethel from the east.24

Orders issued over the next few days specified the arrangements for supplying the Americans during the first phase of the campaign and prescribed measures to maintain security and surprise. Finally, on September 20, Pétain sent his ultimate order, reading in its entirety: “Operations B and C will take place on September 26.”

Pershing’s plan was embodied in Field Order No. 20, issued on September 20 by his Chief of Staff, Hugh Drum. First Army would attack on a 20-mile sector comprising some of the most challenging terrain on the Western Front. The right boundary was to be the Meuse River, overlooked to its east by the Heights of the Meuse. From the river the land rose westward in a series of undulating hills to the Barrois plateau, capped by the promontory of Montfaucon, approximately midway along the German position and four miles from the American front line. West of Montfaucon the surface dipped into the valley of the north-flowing Aire River, then rose sharply to a plateau on which rested the formidable Argonne Forest. Pershing’s plan, developed under Drum’s supervision by September 7, consisted of four phases:

1.A rapid ten-mile advance to a line level with the northern limit of the Argonne Forest, termed the “American Army Objective.” This would cut off the defenders and allow a junction with the French at Grandpré.

2.Another quick ten-mile advance to a line Le Chesne–Stenay, called the “Army First Phase Line.” This would force the Germans fighting the French on the left to withdraw.

3.An attack up the Heights of the Meuse to secure the right flank.

4.A concluding attack to cut the Sedan–Mézières rail line.

The key to the plan was rapid execution of the first phase. To accomplish this, Pershing allocated 12 divisions organized into three corps.* In each corps, three divisions were in the attack line and a fourth was in reserve. (Pershing’s best divisions, of course, were still on the St Mihiel front and would not be able to participate in the opening assault on the Meuse–Argonne.) On the right was III Corps under Major General Bullard, with (from right to left) the 33rd, 80th, and 4th Divisions in the line. Its main job was to advance to the east of Montfaucon and secure the Americans’ right flank along the Meuse River. The center was occupied by V Corps, commanded by Major General George H. Cameron and including the 79th, 37th, and 91st Divisions. It had the key role: to conquer Montfaucon—the “second German position,” the Etzel-Stellung—and advance through Nantillois to Romagne-sous-Montfaucon a distance of about ten miles. To its left was I Corps under General Hunter Liggett, with the 35th, 28th, and 77th Divisions. It was to attack up the valley of the Aire to the east of the Argonne Forest, then with the French Fourth Army to its west cut off the forest at its north end, forcing the Germans to withdraw.

* Corps were groupings of (typically) two to four divisions.

ALIGNMENT OF US DIVISIONS FOR THE MEUSE–ARGONNE ATTACK, SHOWING PLANNED ADVANCE, SEPTEMBER 26, 1918

To accomplish this advance, Pershing established several intermediate objectives. The first was the “Corps Objective,” to which the three corps were to advance independently. In the case of V Corps this line ran just north of Nantillois, about five miles from the starting point. No deadline for accomplishing this was given, but it was clear that it would have to be reached by mid-day. Once V Corps reached the Corps Objective, all three corps would attack in concert up to the line Aprémont–Romagne–Brieulles-sur-Meuse, roughly another five miles. This line, the “American Army Objective,” was to be reached by the afternoon of the first day.25 Subsequent attacks were to bring First Army to the “Combined Army First Objective,” about 12 miles from the starting line, and eventually to the Meuse near Sedan.

The Germans had only five understrength divisions in the Meuse–Argonne sector and 15 more within three days’ march. With nine divisions of 28,000 men each on a 20-mile front, Pershing had an initial 10-to-1 numerical advantage.*26 His divisions were not wholly without experience—seven had occupied front-line sectors and five had been in combat.† But none had served at the front for more than a few weeks, and many were populated largely by recent conscripts who were essentially untrained. It did not help that, just before the attack, staff officers of the five least-experienced divisions (35th, 37th, 79th, 80th, and 91st) were diverted to the General Staff College in Langres, virtually gutting the administrative capacity of the inexperienced divisions.

* Other sources give the American superiority at 4-to-1 (Smythe, Pershing, p. 193) and 8-to-1 (Paul F. Braim, The Test of Battle: The American Expeditionary Forces in the Meuse–Argonne Campaign (Shippensburg, PA: White Mane Books, second revised edition, 1998), p. 85). The main differences seem to be in how one counts available reserves and nearby divisions.

† Braim puts these numbers at four and none, respectively. (Braim, Test of Battle, p. 85.) Smythe says that four divisions had seen action. (Smythe, Pershing, p. 192.) The numbers given above are taken from War Department reports. (Army War College, Historical Section, Order of Battle of the United States Land Forces in the World War: Divisions, Document 23a (Washington, DC: GPO, 1931), passim; Ayres, Statistical Summary, p. 33.)

Most puzzling was (and still is) how the divisions were assigned to their places in the line. The 79th was placed opposite Montfaucon, the key German position. It had never served at the front and had never trained with its newly assigned artillery brigade (or, in fact, any artillery at all), yet it was to take the heights, four miles distant and towering some 400 feet above the division’s jumpoff point, on the first day.‡ At least the 79th was flanked by two more experienced divisions. On its left was the 37th; drawn from the Ohio National Guard, it had spent six weeks occupying a front-line (but quiet) sector in the Vosges Mountains. To its right was the 4th Division, a Regular Army unit (although much diluted with recent draftees) and veteran of the Aisne–Marne and St Mihiel campaigns. But the 4th Division was part of III Corps, not V Corps in which the 79th resided. This meant that any coordination between the two divisions during the battle—and coordination was critical to Pershing’s plan, as we shall see—would have to go through First Army headquarters. In other words, if the right-most regiment of the 79th wanted help from its neighbor the leftmost regiment of the 4th, the commanding officer’s request would have to go up through the brigade, division, and corps headquarters to Pershing’s staff, then the response would go back down the chain to the regimental commander in the 4th before any action could be taken.* This was not an arrangement for smooth cooperation.

‡ The process by which divisions were assigned to places in the line is obscure. The first mention of the 79th in the plan for the Meuse–Argonne is in a memorandum titled, “Proposed Disposition of U.S. Divisions in Line,” dated September 7. (G-3 Assistant Chief of Staff, AEF, “Proposed Disposition of U.S. Divisions in Line,” September 7, 1918, RG 120, Entry 24, “AEF General Headquarters, 1st Army Reports, G-3,” Box 3382, 114.0, NARA, p. 2.) It says that the 79th “is to take the left half of sector Meuse to Aire,” in the general vicinity of where it ended up but covering what eventually was a three-division front. Three days later, Pershing dispatched a letter to Pétain containing a table showing all nine front-line divisions, with the 79th in the position it eventually occupied in the assault. (Historical Division, USAWW, vol. 8, p. 60.) But this was not a final arrangement, as several divisions switched places subsequently. It is possible that the divisions were allocated based on who was closest to their ultimate destination in the line, not with any tactical rationale in mind. In any event, as in so many cases, the archives contain only the results of decisions, not the deliberations that led up to them.

* Adjacent units routinely swapped liaison officers, but their role appears to have been limited largely to communication, not tactical coordination.

First Army had at its disposal almost 4,000 guns of all calibers.† Of these about 600, mostly in French divisions, were assigned to neutralize the German artillery in the Heights of the Meuse and 640 remained on the St Mihiel front, leaving about 2,760 to support the nine attacking divisions directly. Divisional artillery brigades—each augmented by a regiment of nine batteries of 75mm field guns and other batteries—would provide 1,780 tubes to fire the rolling barrage. Corps artillery numbering 400 pieces would concentrate on German guns and strong points. The 542 guns of Army artillery would neutralize distant assembly areas and supply depots and interdict enemy movement behind the lines.27 The firing plan was for one-quarter of the Army artillery to begin with a long-range bombardment at 11:30 p.m. on September 25—enough guns to disrupt the German rear areas but, it was hoped, not enough to alert them to a full-scale assault. At the same time, the French Fourth Army to the west would open its preparatory fire and the guns on the old St Mihiel front would lay down a diversionary bombardment toward Metz. At 2:30 a.m., all guns were to join the preparation.28 At H-hour, divisional artillery was to begin the rolling barrage behind which the infantry would advance; the barrage would pound the German front-line trenches for 25 minutes, then advance at a rate of 100 meters every four minutes. The men would follow at a distance of 300 meters.29

† The divisions, the corps, and First Army itself all had their own artillery units. For the Meuse–Argonne campaign, the divisions (including those of attached French units) had a total of 2,568 guns; the corps had 870; and First Army had 542. (W.S. McNair, “Explanation and Execution of Plans for Artillery for St Mihiel Operation and Argonne–Meuse Operations to November 11, 1918,” December 23, 1918, RG 120, Entry 22, Commander-in-Chief Reports, Box 30, NARA, p. 15.)

In some respects—brief preparatory fire to achieve surprise, the rolling barrage to neutralize the defenders—Pershing’s artillery plan resembled Bruchmüller’s innovative and successful use of his guns at Riga.* But key ingredients in the German general’s success were missing: his attention to explaining the firing plan to the attacking troops; conducting drills that acclimated the men to the rolling barrage; and centralizing control of the artillery at the army level. Pershing’s preparations included none of these; true to his infantry-first doctrine, artillery remained the poor cousin at the party. At the beginning of planning for the Meuse–Argonne, First Army artillery staff were not told anything about the date of the attack, its location, or the enemy forces, such information being deemed too secret for them to possess. They were simply told to prepare for an attack involving 12 divisions. They replied that they required more information to do any planning; it was given to them a day later.30 Four of the divisions had had their artillery brigades stripped from them upon arrival in France; they now received, from other divisions, brigades with which they had never trained and whose officers they did not know. Complicating things further, the ultimate German defense line—the Kriemhilde-Stellung—was ten miles beyond the American starting point, well out of range of all but the very largest American guns. To support the advance, the guns would have to move forward behind the infantry over broken ground and torn-up roads in order to maintain fire superiority—a maneuver well beyond the capability of First Army. This was, in part, because all movement of divisional artillery was to be regulated by the corps commanders—an arrangement that erroneously assumed those commanders would have good communication with their subordinate divisions and with army headquarters.

* See Chapter 4.

Augmenting the artillery was a weapon new to American combat—tanks. Four French light tank battalions, two American battalions, and four groups of French heavy tanks were attached to First Army; almost all went to V Corps. The orders to the tank battalions were terse:

Tanks to assemble in the Forêt de Hesse.* On D day they will follow the infantry as soon as the way has been made passable for them, to their position of readiness in the Bois de Montfaucon and near Cheppy. Thence they will operate in the sectors Nantillois, Montfaucon, Gesnes, and Baulny-Exermont. On the Hindenburg Line being made passable for them, they should be in the best possible position for exercising their proper functions and will proceed to destroy machine-gun nests, strong points, and to exploit the success.31

* Army orders printed locations and unit designations in all-capitals (they still do). These have been reduced to initial capitals herein to preserve readability.

No mention was made of cooperating with the infantry. Tank–infantry coordination was a difficult art. Tanks needed to precede the infantry in order to suppress machine guns and prevent casualties. Infantry, on the other hand, had to protect the tanks, which in combat had limited vision to the front and almost none to the sides or rear. This often made them prey to antitank guns and enemy soldiers armed with explosive charges. (Pétain had expressly urged this point on Pershing.32) If the infantry followed the barrage too closely, however, it could result in tank losses from one’s own artillery. By now, the French and British had developed highly trained combined-arms units, as described in Chapter 4. But joint operations between tanks and infantry remained difficult even when the two arms had trained together. Of course the American infantry had never trained with tanks at all, let alone with the battalions furnished for this attack.†

† See Tim Travers, How the War Was Won: Factors That Led to Victory in World War One (Barnsley, UK: Routledge, 1992; repr., Pen & Sword, 2005), p. 115. Communication between infantrymen and tank crews, the latter sealed into reverberant steel boxes flooded with engine and machinery noises, was almost impossible in combat. The British tried putting bell-pulls on the outside of their tanks; it didn’t work. French soldiers sometimes resorted to banging on the hulls with shovels to get the attention of those inside. (Ibid.; Philpott, Three Armies, p. 482.)

Another innovation was air support. Eight hundred and forty aircraft were assigned to the offensive, a three-to-one superiority over the Germans. Three new American squadrons were included, one of which was the 166th Bombing Squadron flying two-seater DH-4s made in the United States.‡ During the artillery preparation, the objectives of the bombers included “troop concentrations, convoys, stations, command posts and dumps; to hinder his movement of troops and to destroy his aviation on the ground.” During the attack itself, their additional missions were to prevent the arrival of reserves, break up counterattacks, and harass the enemy as he withdrew. Reconnaissance planes would photograph enemy positions and the results of bombing raids.* A pursuit group was assigned to accompany the attack; its instructions were to “protect our observation aviation at every altitude from the Meuse inclusive on the east to La Hazaree [sic] inclusive on the west; prevent enemy aviation from attacking through the Woëvre and ... attack concentrations of enemy troops, convoys, enemy aviation and balloons.”33 No instructions were issued for supporting the attacking infantry directly, nor were there any means for units engaged at the front to request air support.† No aviation units were assigned to individual corps or divisions.

‡ But see Chapter 3 on the deficiencies of the DH-4.

* Thirteen balloons were assigned to observe enemy activity and spot for the artillery. (Historical Division, USAWW, vol. 15, p. 235.) It is clear from the situation reports filed during the battle, however, that the balloons were generally grounded or blinded by bad weather, and those that got up suffered heavy casualties. (Ibid., vol. 9, pp. 160–209 passim.)

† Colored panels were issued for infantry units to spread on the ground so as to indicate their positions to friendly aircraft; but the men were not trained in their use and they were almost never deployed. (G. de la Chapelle, “Report with Regard to the Employment of the Squadron During the Battle from September 26th to 30th,” c. October 1918, 17 N 128, SHD, p. 1.)

The newest military innovation was also the one most feared and loathed, even by those who used it—gas. During the planning for the Meuse–Argonne, the First Army operations staff studied the intense and effective use the Germans made of gas during their Spring Offensives. These lessons were incorporated into Army orders for the attack. Sufficient gas was obtained from the French to neutralize German artillery and points of resistance, and to inflict casualties on personnel. Army field orders during the action pressed for its greater use. But in practice, First Army used little gas. The three battalions of the 1st Gas Regiment were distributed among the three attacking corps. During the artillery preparation, each was to fire non-persistent gas shells only after halts in the artillery shelling as ordered by the corps chief of artillery. (Persistent mustard gas was to be fired at the Heights of the Meuse to protect the attack’s right flank.)‡ During the advance itself, only smoke and thermite (an incendiary) were to be fired. In the words of historian Rex Cochrane, “This was the final sop to Army’s indecisive plans for the use of gas on the Montfaucon front, and even this was never carried out.”34 The reason was that Pershing’s orders left the use of gas up to the discretion of the corps commanders, who were as inexperienced as their men with the new weapon and were reluctant to use it. As a result, many German positions that might have been neutralized by the preparatory bombardment were able to offer serious resistance.

‡ Gas came in several varieties. Non-persistent chemicals such as phosgene and diphosgene dispersed in 10–20 minutes; they were used to disable enemy positions that were about to be assaulted and occupied by friendly troops. Persistent types such as mustard gas could take several days to lose their effectiveness. These were used to make enemy positions—gun emplacements, command posts, transportation hubs—untenable for a relatively long period of time. By 1918 the threat from gas was no longer the infliction of mass deaths on the battlefield; effective gas masks and training had largely eliminated that possibility. Instead, by forcing the enemy to don masks, one greatly reduced his capability. The masks were difficult enough to wear on defense; on the offense they were virtually impossible. Of course, gas casualties continued to occur, especially among inexperienced troops, and the victims suffered horribly. Unlike the other combatants the AEF never did develop an effective organization, doctrine, or training program for gas warfare.

In hindsight, perhaps the biggest flaw in Pershing’s plan was a failure to address seriously the road problem. Supply and transportation had been the bane of every offensive in the war so far, even when the roads were good. In First Army’s entire 20-mile sector only three roads led north, and all had been ruined by the previous four years’ fighting. In the words of an after-action report by Pershing’s logistics staff, “As a result, the map indications of roads leading north from Esnes, Avocourt, and Boureuilles actually represented the former locations of those roads. Instead, there was only shell-holed countryside, with wire entanglements, for a distance of 3 to 6 km in advance of the American lines.”35 Rainy weather would turn this moonscape of Jurassic clay into bottomless mud—the same mud that had almost immobilized Moltke’s Prussians as he pursued Napoleon III northward almost 50 years earlier. Pershing’s plan allocated repair of roads to the engineering companies and trains of the attacking units themselves; these were capable at most of assisting their own divisions, but not of coordinating road construction across the entire front. Truckloads of gravel and other materials would be stationed at convenient locations, but the major items of equipment were the pick and shovel. Although the Americans had invented the Holt caterpillar farm tractor, on which the tank was based, no one thought to create armored bulldozers, graders, and other earthmoving equipment that could follow the front-line troops and rapidly construct serviceable roads. (Of course, no other armies had hit upon this innovation, either.*) Further, the nine divisions would have to share the three roads that nominally existed, leading to conflicts of need and priority with no central authority to sort them out. They would have to advance against a tide of ambulances, prisoners, and empty supply wagons coming the other way. A circulation map was distributed on September 19, but it had no information on the roads that lay beyond the American lines of that date. On September 25 a map was distributed that had data on roads as far north as Cunel Heights but no further. Nonetheless, Field Order No. 20 optimistically assumed that roads would be available when needed. In its directive to the artillery, for example, it said, “Divisional artillery will follow the advance of our infantry to forward positions and this artillery will in turn be followed by corps artillery and then by army artillery. Corps commanders will prescribe roads available for these movements, and promptly inform the chief of artillery of arrangements made.”36 This was simply to ignore a reality that was manifest long before the attack itself.

* The bulldozer was not invented until 1923. The first US Army combat engineering battalions were established shortly before World War II.

Pershing’s plan relied on surprise to keep the Germans from reinforcing the sector quickly. Thirteen of the Germans’ 18 divisions were opposite St Mihiel. To encourage them to expect an attack toward Metz, First Army concealed its activities in the Meuse–Argonne by disguising its reconnaissance troops in French uniforms, relieving the French Second Army (then occupying the sector) only just before the attack, and moving only at night. Artillery registration fire and radio traffic were kept to a minimum. Groups of tanks in the St Mihiel salient moved as if preparing for an offensive against Metz. While long-range guns bombarded Metz, the Air Service bombed the railroad station and the supply depots there, and flew bombing and pursuit missions to the east up to Château Salins. The officers talked “confidentially” to the men about an upcoming attack on Metz; the men, of course, talked among themselves in the bars and cafés. Nevertheless, by the 25th the Germans got wind that something was up along the Meuse. They withdrew their forward troops back to the main line as a defense against artillery and started moving reinforcements toward the area.*

* A postwar German assessment published in an American journal noted, “When it is remembered that nine divisions were concentrated in the first line for this attack without the knowledge of the Germans, it must be realized that the efforts of the troops to camouflage their movements were most successful.” (Hermann von Giehrl, “Battle of the Meuse–Argonne (Part 1 of 4),” Infantry Journal 19, August (1921), p. 132.)

Field Order No. 20 was very detailed about the physical arrangements for the offensive—the divisions that would carry the assault; the artillery, tanks, planes, and other services that would support them; and the objectives to be reached by given dates. It did not make clear, however, exactly how the divisions were to achieve their objectives. V Corps was positioned so that Montfaucon was directly in the path of its right-most division, the 79th. Yet Drum’s mission for V Corps was:

(a) With its corps and divisional artillery it will assist in the neutralization of hostile observation from Montfaucon.

(b) It will reduce the Bois de Montfaucon and the Bois de Cheppy by outflanking them from the east and the west, thereby cutting off hostile fire and hostile observation from these woods against the III and I Corps.

(c) Upon arrival of the III and I Corps at the corps objective ... it will continue the advance to the American Army objective ... and penetrate the hostile third position without waiting for the advance of the III and I Corps.37

The Bois de Montfaucon and the Bois de Cheppy were small, adjacent woods that lay immediately over the lines of V Corps; there was no mention of the corps capturing the town of Montfaucon itself. Nor would it be possible to “outflank” the two woods; they lay directly astride V Corps’ path. More to the point was the mission assigned to III Corps, whose sector lay to the east of Montfaucon and did not include it:

(a) By promptly penetrating the hostile second position [an east–west line running through Montfaucon] it will turn Montfaucon and the section of the hostile second position within the zone of action of the V Corps, thereby assisting the capture of the hostile second position west of Montfaucon [emphasis added].

(b) With its corps and divisional artillery it will assist in neutralizing hostile observation and hostile fire from the heights east of the Meuse.

(c) Upon arrival of the V Corps at the corps objective ... it will advance in conjunction with the IV Corps to the American Army objective.38

Because it would become an issue later, one may ask what, exactly, was III Corps supposed to do at Montfaucon? Pershing’s order was less than clear. Possibly it was for III Corps to bypass “Montfaucon and the section of the hostile second position within the zone of action of the V Corps,” while staying within its own zone of operation. That might constitute “turning” the German position, as the defenders would believe themselves about to be cut off. Or it could attack westward behind Montfaucon into the zone of V Corps, severing the German position from its lines of supply and reinforcement. The question hinges on the meaning of the term, to “turn” a position. It is resolved by examining the definition in a textbook written by a West Point professor and used there since 1889: “Turning movements, as distinguished from flank attacks, consist in detaching a force and sending it around the enemy’s flank, with a view to an attack from that direction or to threatening his communications, etc.”39 Other popular texts had similar definitions. So First Army’s intention—poorly stated—was that at least part of III Corps was to cross into V Corps’ zone behind the hill of Montfaucon. It was a creative maneuver, well within the spirit of Pershing’s open warfare doctrine. It would violate the corps zone boundaries laid out in Field Order No. 20; but as long as those boundaries were understood by everyone to be flexible and not to impede lateral movement for good tactical reasons, all would be well. In the event, all would not be well.

There are several yardsticks one can use to measure how realistic Pershing’s plan for the Meuse–Argonne was. The first is the successful British attack at Amiens under General Rawlinson on August 8, which penetrated six to eight miles on the first day while capturing 400 guns and 27,000 prisoners. The assault was a masterpiece of combined-arms operations. Surprise and deception successfully concealed from the Germans the fact that the Australians and Canadians, the best assault troops in the British Army, would lead the attack. Artillery and machine guns provided more firepower than before. Ninety-five percent of the German guns had been located before the attack, and 2,000 artillery pieces were carefully preregistered to neutralize them. Air supremacy was provided by 1,900 planes, which were also used to mask the noise of the approaching tanks, which numbered 342 Mark Vs and 72 Mediums as well as troop carrier and supply tanks. Most important, the British had spent the previous year developing methods for mutual support among infantry, artillery, tanks, and aircraft, and had trained their troops in these methods.40

The British were helped by the fact that the Germans were caught in the middle of a front-line relief, their morale was low, and their defenses were thin. Indeed, the German positions in the summer of 1918 were of a considerably different nature than the ones the Allies had fruitlessly assaulted since late 1914. They were not designed as defensive positions at all; they were merely the furthest points the Germans had reached in their Spring Offensives, and were organized to support an attack. Rather than three zones of increasing toughness, they often comprised only a single, forward position with few wire defenses or shellproof dugouts. The troops themselves were exhausted and hungry; their offensive had petered out partly because they stopped to loot the abandoned food supplies of the retreating British.41 Those were the advantages that allowed the British at Amiens to advance six to eight miles on the first day. The AEF had none of them.

The second comparison is with the 1916 German offensive at Verdun. As we have already seen, Falkenhayn’s plan included a massive attack southward on the east bank of the Meuse. But, against the advice of his artillery advisers and of Crown Prince Rupprecht, he planned no action on the west bank, where there were large concentrations of French artillery.42 The result was that the German troops were shot up by enfilading fire from the west. Falkenhayn had to regroup and divert troops to the Meuse–Argonne sector (Maas-West, to the Germans), resulting in the bloody battles for and around the Mort Homme and Hill 304.

Pershing’s plan was, in this respect, identical to Falkenhayn’s—indeed, on the identical battlefield, but rotated 180 degrees. Pershing ordered nine divisions to attack northward between the Argonne Forest and the Meuse River. East of the Meuse, where the Germans had heavy guns hidden in the hills, the French XVII Corps was only to lay down harassing bombardments and make local raids.43 Like Falkenhayn, Pershing was attacking with the Meuse to his right while ignoring the strong enemy artillery across the river. The result could have been predicted, but was not.*

* There were, of course, important differences between the two offensives. Falkenhayn wanted an artillery-heavy campaign of attrition. Pershing intended an infantry-led breakthrough.

Finally, the history of the war showed that the problem of supply inevitably limited the most audacious penetrations. Rail transport flowed along static lines and could not follow a rapid advance. Roads capable of bearing heavy traffic, much of it from motorized vehicles, could not be built quickly. Construction methods, equipment, and training were all geared toward trenches and static emplacements, not rapid extension of roads and quick establishment of efficient logistical networks. As a result, supplies could not reach the troops and artillery could not move forward to follow them. This problem had plagued almost all successful offensives in the war. The Russians’ Brusilov offensive of 1916; the German counterattack against the British at Cambrai in July of 1917; the German–Austrian breakthrough at Caporetto three months later; all five of Ludendorff’s attacks in the 1918 Spring Offensive; and the British advance at Amiens all ground to a halt because food and ammunition could not be moved forward fast enough over the churned-up ground. Even the Schlieffen Plan of 1914 faltered as much because the Germans outran their supply lines as because they ran into the French at the Marne.44 The British, French, and German armies had four years’ experience trying to move supplies forward across torn-up battlefields. The Americans had almost none.

In essence, then, First Army’s plan for the initial Meuse–Argonne assault was a desperate gamble. The planners assumed the first two German lines would be lightly held, and that the enemy would be fooled as to the axis of the attack. They called for a ten-mile advance by nine divisions, followed by a breakthrough of the Kriemhilde-Stellung, on the first day, when no American division had yet advanced three miles in a single day, not even at St Mihiel, where the attacking troops were combat veterans and the Germans were already withdrawing. Only three roads would be available to support the advance, and those were roads in name only. If the Americans failed to break through on the first day, the Germans would be able to reinforce the sector with an additional 15 divisions within three days. Even though the German divisions were one-third the size of the Americans’ and were disorganized and tired, Pershing’s operations staff knew that they were still formidable defenders. Unless the Americans reached their first day’s objectives, the breakthrough assault would turn into a protracted and bloody campaign. Hugh Drum and his staff convinced themselves that a first-day penetration was not only possible but likely. Pershing did not need to be convinced; he already believed it. Writing to his wife ten days before the attack, General Kuhn predicted Germany’s imminent defeat:

What a reversal of form since July 15 when everything seemed to be going the Kaiser’s way. I don’t see how there can be any come back now and Germany has surely hit the toboggan slide. Of course, things may not always go with perfect smoothness so we must be prepared for little setback now and then.45

He would find out what a “little setback” looked like.