CHAPTER 14

BOIS 250 AND MADELEINE FARM, SEPTEMBER 29–30

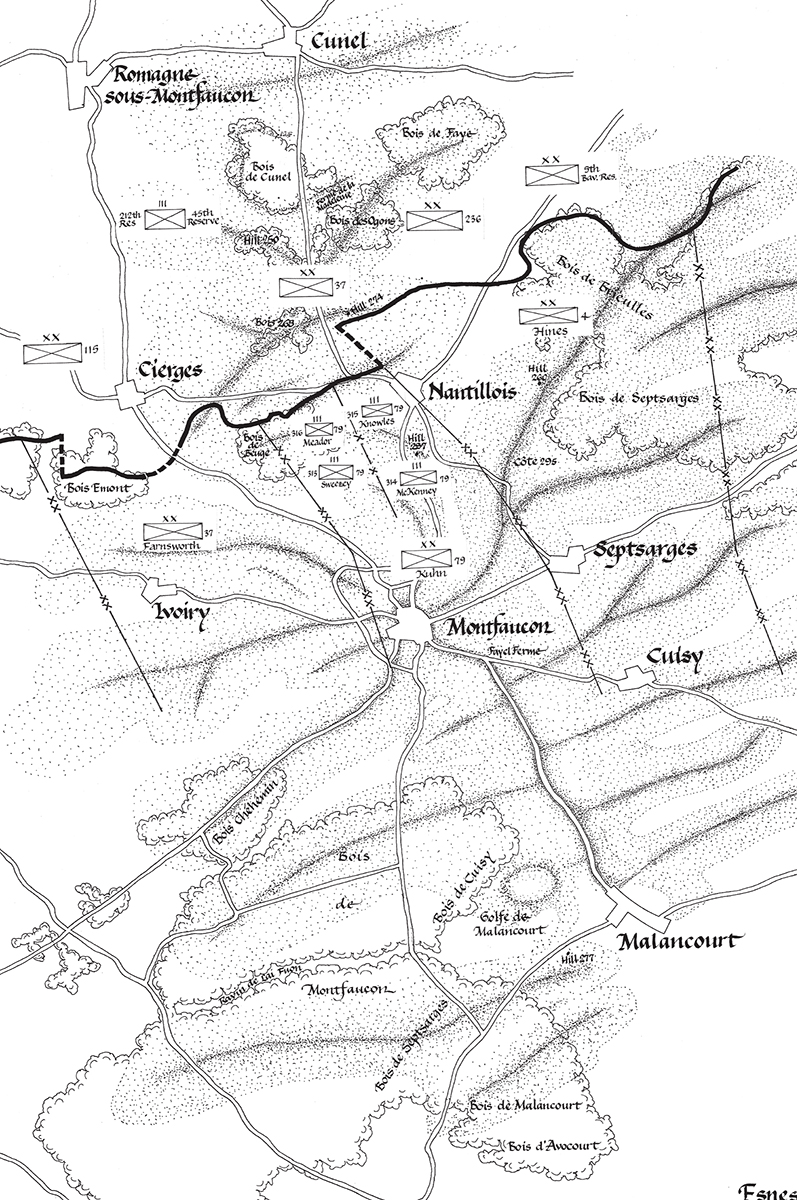

Kuhn’s Field Order No. 9 spelled out his arrangements for the advance on September 29. The infantry would attack at 7:00 a.m. On the left, the 316th Infantry under Colonel Charles would lead as before, its 1st Battalion (Major Parkin) to the west and its 3rd Battalion (Captain Somers) to the east; the 2nd Battalion (Captain Lukens) and the Machine Gun Company would follow in support. The immediate objective would be Bois 250, half a mile ahead. On the right, Charles’s 315th would be in front, with its 2nd Battalion (Major Borden) to the west and its 3rd Battalion (Major Lloyd) to the east, supported by the 1st Battalion (Captain Noonan) and its own machine gun company supporting from behind. Facing it at a distance of half a mile were the Bois des Ogons and Madeleine Farm, filled with German artillery and machine guns. Between the two regiments would be Company C of the 312th Machine Gun Battalion. Four French tanks would accompany the 315th, which had tried and failed three times the previous day to advance past Hill 274; none were allocated to the 316th. The support regiments would follow, Sweezey’s 313th on the left, the 314th under Colonel Oury (who was also commanding the 158th Brigade) on the right.

That looked fine on paper, but Kuhn was getting unwelcome news. Half an hour before the attack, Major Pleasonton, an officer in his headquarters, passed on a message from Sweezey “to the effect that his regiment was much depleted due to straggling, was low in ammunition owing to the failure to connect with combat train which was under shell fire, and represented a generally bad state of affairs.”* Kuhn told Pleasonton to ignore the report, “which was probably largely exaggerated, and that no attention could be paid to such tales.”1 An hour later Knowles sent Kuhn a message that was even more blunt:

We have been under artillery fire all night which has given us losses amounting to 50%. We have not been able to get our rations up because the train was shelled on the whole road. The men are getting so weak on account of getting no food there is not much driving power left. We are going to do the best we can but I am afraid the losses will be very heavy.2

* Sweezey’s actual report read, “Your message just received ordering attack. I fear the most dire results on account of condition of men. Invent [i.e., the 316th Infantry] I do not believe has half his strength in our front due to straggling. My men have had no sleep for 3 nights, only cold food, have been out in cold rain all night without any protection whatever and many without overcoats. I of course will comply with orders and do my best under conditions but due to heavy casualties among officers I cannot guarantee results. Request 2 combat wagons be sent immediately with ammunition.” (“Field Messages of the 157th Infantry Brigade,” 1918, RG 120, 79th Division, Box 16, 32.16, NARA, September 29, 1918, time sent not given.)

Kuhn’s response is not recorded, but it cannot have been much different than what he told Pleasonton. At least one of his brigade commanders, he could tell himself, was following orders instead of complaining. As the attack began, Oury sent a message to Kuhn describing his dispositions and adding, “All formed in depth according to orders. I am in liaison with the division on our right ... Reports will be rendered as advance progresses.”3 In return Oury received at a message at 8:07 a.m. from Colonel Ross informing him that sound-ranging equipment, used to locate enemy guns, had arrived and “consequently our counter-battery work should become more effective.” Ross also betrayed divisional headquarters’ frustration with the general lack of information regarding its regiments’ progress when he added, “The 316th Infantry is practically on line with you according to last reports. Have heard nothing from them since the hour of attack. Itasca [79th Division] appreciates the tone of your message and wishes you every success.”4 Here was one brigade commander, Ross must have thought, who knew his job.

An artillery bombardment was ordered between 6:00 and 7:00 a.m.; but the division’s guns, scattered across an area nearly four miles deep by two and a half miles wide, were either in transit or out of communication, so almost nothing happened.*5 Despite the lack of either a barrage or counterbattery fire, at 7:00 a.m. the two lead regiments crested Hill 274 and advanced down its north slope. The result was a repetition of the previous day. Within five minutes they ran into heavy machine gun fire from the Bois des Ogons, the Madeleine Farm, and seemingly every bush and ditch on the landscape. As the two battalions of the 316th emerged from Bois 268 on their way to the wood ahead, the left of the line was particularly hard hit. Machine gun fire from three directions cut down one company commander and two battalion officers; four other officers were wounded, one mortally. In the 1st Battalion, Company C had one officer remaining, Company D had none; in the 3rd, Companies I and L, having lost all of their officers, were led by sergeants.6 The 1st Battalion got 300 yards from Bois 268, then stopped in its tracks. At 10:10 a.m. Colonel Charles reported his situation to Nicholson in 157th Brigade headquarters: “300 yards ahead of North Western edge 268. Troops being cut to pieces by artillery and machine gun fire. 2nd Battalion, 119th Field Artillery now here.” He quickly followed that up with, “Retrograde movement very difficult to check. Field back of our P.C. now under constant shell fire.”7 Nicholson relayed the information to V Corps as well as to Kuhn and Oury, adding, “Hostile artillery fire practically unopposed by our artillery.”8 Pleas continued to come in from Charles:

Request 155’s for counter battery on Bois de Cunel guns and draw at 09.0–82.3. Tanks south of Bois de Bigors [sic] refuse to operate without artillery support. Our lines on right and left this regiment have fallen back exposing both our flanks. My men too are retiring. Am reorganizing in woods No. 268 to advance as soon as flanks are covered.9

* The eight 9.2-inch guns of the 65th Coastal Artillery Corps, assigned to the 57th Field Artillery Brigade, were stuck in traffic many miles to the south. Some of the French heavy artillery regiments could be located no more precisely than “on road.”

For once, Charles’s pleas were answered. The artillery liaison officer in Nicholson’s headquarters got the message to General Irwin, who ordered his 121st and 454th Artillery Regiments to deliver the fire. That, plus whatever the 119th Artillery was able to do, had the desired effect. A few minutes later Charles sent a runner back to Sweezey with the message, “Enemy retreating rapidly under our fire. Please throw in full support at once to drive him before he reorganizes.”10 Sweezey pressed his regiment forward; but on their own Charles’s men continued to withdraw into Bois 268, mingling with the advancing soldiers of the 313th; only with difficulty could the regiment’s officers stop them from retreating further.

The right side of Charles’s line did better than the left, at least to first appearances. The 3rd Battalion got all the way into Bois 250 and cleared it of machine guns, but it was unsupported and badly disorganized. Many small groups, thinking they were isolated and perhaps left behind, withdrew back to their starting point. Remaining in the wood, at its northern edge, were three officers and about 50 men from Companies I, K, and M and the 312th Machine Gun Battalion, all under Captain Somers, the acting battalion commander. Around noon, as the rest of the regiment drew back into Bois 268, Somers’s detachment became isolated half a mile ahead of the nearest American troops. It threatened to turn into, if not a Lost Battalion, then perhaps a Lost Platoon.

At about the same time General Nicholson came forward to the position of the 316th on horseback, fully visible to the Germans and oblivious to their fire. His intent was to gauge the situation and order Colonel Charles to make a further assault on Bois 268, but he quickly realized that the 316th had nothing left to give. Locating Colonel Sweezey, he ordered him to pass his regiment through the 316th, take over the front line, and attack. Charles organized what was left of the 316th, amounting to 500 men (out of a full complement of 3,800), into a single battalion commanded by Major Parkin, so it could follow the 313th in support. Kuhn, not knowing of Nicholson’s attack order, sent at 12:55 p.m. a message to Charles:

Message stating your troops falling back received. Do all you can to restore order and confidence as there is no cause for alarm—organize holding line north edge Bois de Beuge with machine guns, reorganize troops and omit [sic—?] orders—am arranging for protection artillery barrage in case of need.11

The Bois de Beuge was half a mile south of the current position of the 316th; this order shows that Kuhn had accepted the impossibility of further advance and was now only interested in stabilizing his front, even if it meant giving up hard-won ground. Kuhn informed V Corps:

Line enfiladed by artillery fire from right and left, principally right and forced to fall back because of this fire, machine gun fire, and total exhaustion of troops. I consider them incapable of further driving power. Am organizing and holding line N. edge Bois de Beuge–Nantillois to re-organize and to meet possible hostile counter attack ...12

But Kuhn’s communication was premature. His order to Charles did not arrive at the regimental headquarters until two hours later, after Charles’s attack had jumped off.

While this exchange was going on, Captain Somers’s impromptu force was still holding its isolated position in Bois 250. The captain sent five runners back to get in touch with the rest of the 316th. All five were shot down; three ultimately died of their wounds. Fortunately, Somers’s little band was joined a few hours later by a platoon from the 312th Machine Gun Battalion, which had followed in support. Spotting a group of German machine gunners coming toward them from the northwest, the new arrivals opened fire; the Germans dropped their weapons and fled. From their vantage point Somers and his men could see the German flank to their left, along with an artillery observation post and several machine gun nests. On these they turned their own machine guns and automatic rifles, but were rewarded with a deluge of artillery shells and machine gun bullets. At this point their own machine gun platoon ran out of ammunition, but the German fire had slackened enough to allow them to return to the lines of the 316th and get more. The rest of Somers’s group stayed put, awaiting either relief or further orders.13

At 2:30 p.m. the 313th attacked out of Bois 268, followed by Major Parkin’s battalion of the 316th in support; there was no time to organize an artillery barrage. The 313th suffered heavy casualties right away. Companies G, B, and A had their commanders killed or mortally wounded. Lieutenant James Towsen was wounded eight times before he would consent to being sent to the rear. Moreover, the regiment veered too far to the east, taking it as far as the Bois de Cunel and within a hundred yards of Madeleine Farm, but out of its own sector. Behind them Parkin’s battalion, attacking straight ahead, quickly found itself back in Bois 250, with the 313th nowhere in evidence. As it got to the northern edge of the wood, there were Somers and his band. Parkin set up a defensive line and advanced into the open field to survey the area. To the northeast was a hospital; to the northwest the town of Romagne; and in between large German troop concentrations. To his right in the sector of the 158th Brigade was the Bois des Ogons, which he was now in a position to outflank. Parkin sent Lieutenant Mowry Goetz back to the Brigade PC to report this fact and to ask for reinforcements so he could pull off the maneuver. But Goetz could not find Colonel Nicholson and no one else in the PC would authorize an attack, given that Kuhn had ordered the brigade to assume the defensive. At any rate, Parkin’s battalion was under heavy fire and taking many casualties. Even though it now included Captain Somers’s scratch platoon it was down to 250 men.14

Back at the PC of the 316th there had been a change of command. As Colonel Charles was dictating a message to his signals sergeant a shell exploded nearby, wounding him in the leg and killing the sergeant; Lieutenant Colonel Robert Meador, the second-in-command, took over the regiment. It was Meador who finally received Kuhn’s order to withdraw to the Bois de Beuge. By carrier pigeon he replied:

Order to organize Beuge received 15 H 25, but 313th Inf. has relieved us for assault, & is held up with ruinous losses on northern edge wood 268.* Am calling in scattered troops, & trying to communicate with Sweezey. † Charles slightly wounded. This Regt’s effectives about 400. 313th also fast melting away.15

* The accounts by members of the 316th uniformly express the belief that the 2:30 p.m. attack of the 313th never got far from Bois 268 before being pinned down. It is clear from the records of the 313th itself, however, that they made it to the southeast edge of the Bois de Cunel, almost a mile further on. The confusion probably arises from the fact that the 313th, having wandered out of its sector, became for a while invisible to officers of the 316th.

† Thus the handwritten original. The typed transcript, in place of “calling in scattered troops,” reads, “falling in scattered groups.”

Among the “scattered troops” was Parkin’s battalion. Bowing to circumstances, Meador ordered Parkin to retire and at the same time sent a messenger to the 57th Field Artillery to cancel a bombardment that was to open up on the Bois de Cunel. Once again Lieutenant Goetz volunteered to deliver the message. He and a private went forward at great risk to Bois 250 to convey Meador’s order. With the order in hand, Major Parkin withdrew his men, now numbering 160, from Bois 250 at 9:00 p.m. By the time he reached the Bois de Beuge the defensive line Kuhn had ordered was in place and strongly held. The position Somers and Parkin had reached in Bois 250 was the furthest forward, not only of the 79th, but of all the other divisions in the Meuse–Argonne that day.16 Sweezey, also under orders, withdrew his 313th Infantry from the Bois de Cunel and joined the 316th in the Bois de Beuge a mile and a half to the rear. Retiring was as expensive as advancing; two more companies, C and D, had their commanding officers killed and the regimental operations officer dropped with a bad leg wound. As before, sergeants and corporals led companies and platoons when their officers fell.* At 7:00 p.m., Meador reported his situation to Kuhn; he was not encouraging:

Have divided defensive sector North edge Bois de Beuge with 313th. Even so, line untenable. This Reg’t has 3 M.G.s and 150 infantry to hold a front of one kilometer. Ammun. 7000 rounds; food none; water, little.17

* Colonel Sweezey remained bitter about having been ordered to withdraw, believing that he would have been in a position to outflank the Bois des Ogons had he been supported by the adjacent units. In his operations report after the Armistice he wrote, “I give it, however, as my unqualified opinion, that had we received expected support by the troops on our left, the combined Army Objective ... could have been reached that evening by 18h, with the consequent capture of a great many field pieces which were seen in operation just beyond the woods not more than 400 to 500 meters distant. This belief is confirmed by the statements of both battalion commanders of the attacking line who reached the position referred to.” (Sweezey, “Report of Operations, September 25–November 11,” p. 4.) As noted above, Parkin of the 316th also thought he could have turned the Bois des Ogons given reinforcements. In fact, there was no realistic prospect of such a maneuver by either unit. Both were depleted in manpower, ammunition, and provisions, and both would have been turning their flanks toward the enemy, who was well supplied with precisely aimed artillery. As the 313th and 316th at this point were unaware of each other’s presence at the wood, they likely would have ended up shooting at each other.

To the right of the 316th, the attack of the 158th Brigade was led by Knowles’s 315th Infantry. Their orders said that the 4th Division, to their right, was half a mile further along than the 79th, so their flank would be covered as they attacked from Hill 274. They would be accompanied by four Renaults of the French 345th Tank Company.† A request for artillery support was denied; no guns were available other than those already accompanying the regiment.18 The attack went off on time. Company I of 3rd Battalion made it to the Bois des Ogons with light casualties but then things got difficult as they came under fire from front and flanks. Captain Albert Friedlander, the company commander, had been evacuated for shell shock the previous day; the two surviving lieutenants, although both wounded, continued to lead the unit. Companies L and K ran into fire coming from the Bois de Brieulles on their right flank. Company L quickly lost its commander, Captain Francis Awl, and was down to a single lieutenant. Sergeants took over its two platoons. Getting into the woods, Company K bumped up against a machine gun nest. The commander, Captain William Carroll, and a sergeant worked around the flank of the nest, shot one gunner, and captured two others. The experience of 2nd Battalion was similar. Company F immediately lost two of its lieutenants, one killed and one fatally wounded. As Company G tried to take Madeleine Farm its commander, Captain Earl Offinger, was wounded, leaving one officer in the company. The Headquarters Company’s 37mm gun, the last in the regiment for which there was ammunition, ran out while shelling a machine gun nest and had to retire. Thereupon the 2nd Battalion ran into the same flood of machine gun bullets that had stopped the 3rd Battalion and took to ground.*

† The Army War College account says 15 tanks. This is yet another illustration of the frequent disagreements among the sources. (Army War College, Historical Section, “The Seventy-Ninth Division, 1917–1918,” p. 45.)

* Once again, the report of French tank commander Richard tells a different story. According to it, the 345th Tank Company cleaned out the left side of Bois de Cunel; but the infantry, taking fire from the hills near Romagne, were stopped. The same happened when the tank company turned to attack the Bois des Ogons; the infantry failed to follow and the tanks had to withdraw. ([no first name] Richard, “Report of the Battalion Commander Richard, Commanding the 15 Light Tank Battalion to the Commanding Officer of the 505th Regiment of Artillery of Assault,” October 2, 1918, 17 N 128, SHD, p. 2.)

It was apparent from the flanking fire that the 4th Division, far from being ahead of the 79th, was nowhere nearby, and by 9:00 a.m. the advance of the 315th had come to a full stop. Colonel Knowles telephoned General Kuhn: “We have no recent information as to the location of front line, 4th Div. It was abreast of us yesterday afternoon. 4th Division must go forward before I can. Hostile artillery in location 11.8–83.4 is enfilading my front line.”19 At that point the connection went dead. The coordinates Knowles gave corresponded to the southern edge of the Bois de Fays, where the 4th Division would have been, had it, in fact, been half a mile ahead of the 79th. Kuhn immediately contacted General Hines, commander of the 4th Division: “Cannot advance unless your left brigade also advances at the same time. Request present location of your front line and your intentions.”20 This must have been a novel experience for Kuhn: the 4th Division was holding him up, instead of the reverse. There is no record of a reply in the archives of the 79th.

At 11:15 a.m. Colonel Oury sent a runner to Kuhn summarizing his brigade’s situation:

Since writing last message have had a definite report from the front ... The advance has been stopped. It appears to be held up on right and left divisions who are still behind us. The enemy fortification at Madelaine Swamps consists of anti-tank guns, machine guns, renders imperative further artillery preparation before advance can be resumed. Bois de Cunel is also strongly held. Request that heavy artillery be again laid on Farm de la Madeleine and that the 37th Div. be requested to push up guns to prevent enfilading machine gun fire from nests in their fronts.21

The message got to Kuhn more than three hours later. Around noon, Oury followed up with a more realistic assessment:

The situation has again changed. The 315 Inf is retreating from its position. It is now passing my P.C. I have given orders to Maj. Borden to reorganize and proceed back to the front. I have given the same orders to Col. Knowles. This to be accomplished by 13H00. 314th Inf is in place but are making no attempt to move forward with it. Our position in front is strongly held and must be reduced by artillery before infantry can take it. Request that preparation start at once with strongest artillery preparation that can be given us.22

This did not reach the general until 8:47 p.m, by which time events had passed it by. By 1:00 p.m. the 315th was back on Hill 274.

Although positioned 800 yards to the rear in support of the 315th Infantry, the 314th suffered as well. At 9:20 a.m. Lieutenant C.A. Webb, the 79th Division liaison officer to the artillery, reported that two battalions had made in into Bois des Ogons—how far he didn’t know—but that several companies were held up back on Hill 274 by a single machine gun that had not been suppressed. Any further advance was blocked by artillery fire, high explosive mixed with gas. The Germans had not dropped gas shells on the front line for fear of hitting their own troops, so they concentrated on the rear area where the 314th was positioned. The men had to advance with their gas masks on.* As it happened, almost all of the losses of the 314th were from shell fire rather than machine guns. One of the dead was Major Alfred R. Allen, who had just a few hours earlier taken over command of 1st Battalion. Hit in the head, he died in the hospital a few days later. He had been a prominent neurologist and faculty member at the University of Pennsylvania Medical School. Another was the regiment’s French adviser, Lieutenant Poulaine, a veteran of the elite Chasseurs Alpins, nicknamed the “Blue Devils.” As he was meeting with two officers of 2nd Battalion on how to conduct the attack, a machine gun bullet hit him in the head. One of the officers reported his words: “Ah! Captain, I was a fool—I was careless. After four years I let them get me that easy! Kiss mother for me.” Some personal details and a final “Goodbye” were the last words the officer heard. A stretcher was fashioned from rifles and overcoats and the lieutenant was carried to the rear; but he died soon after reaching the first aid station.23 By evening, the 314th had withdrawn to where they had started that morning, dug in on a line a third of a mile northwest of Nantillois.

* In general, gas was a minor factor in the Montfaucon battle. Captain Clark, the division gas officer, reported on September 29 that the 79th suffered no gas attacks until after noon on the 27th. This was presumably because the Germans were pulling their guns back in anticipation of the September 26 attack. The 79th first ran into gas as it attacked north of Montfaucon and in the Bois de la Tuilerie to its east, but only about 50 shells fell up until mid-day on the 28th, causing 45 gassing cases, of which Clark suspected that three-quarters were malingerers. Clark was unaware of the over 400 cases that were arriving at the gas hospitals in the 79th’s sector. (Cochrane, “79th Division,” p. 45.)

Not only the infantry regiments of the 79th suffered that day. In the morning the 119th Field Artillery Regiment moved up through Montfaucon in thick fog and took the road toward Nantillois. About 9:00 a.m., as the tail of the column was coming down the hill, the fog lifted and German artillery opened up on the regiment with great accuracy. Private Jacks of the regiment’s Machine Gun Company believed ever afterward that the 119th had somehow gotten past the American infantry and bumped headlong into the German gun positions. Several enemy batteries, in Jacks’s telling, blazed away at the 119th at virtually point-blank range. The men of his company could clearly see the enemy’s muzzle flashes and quickly unlimbered their machine guns to fire on their tormentors. The scene was chaotic:

The orchards and gardens by the highway in an instant were dotted with dead men and horses, and the dim atmosphere became sticky and choking with the poisonous fumes of gas and the sickening odor of high explosives. Gassed and wounded horses staggered screaming and plunging through this bedlam, there was yelling and yelping on every hand, the flaming machine-guns set up their clattering yammer in every direction, and all around rose the drumming roar of heavy guns and the crash of incoming shells ... The naked slopes were covered with mournful relics, including many fragments of the 79th Division infantry, who came up irregularly and were shot down on the exposed open. I saw one man who fell over on his back and was clutching a blood-soaked letter in his hand. I walked over to him with another machine-gunner, thinking he might have some ammunition we could use. He was dead when we reached him, and a shot carried away part of the letter, but we picked up the red fragment remaining and read all that was left, the last couple of lines scrawled in a small feminine hand, “—come back to me and I will never fool you any more. Lovingly, Betty.” He had been shot through the throat and had bled to death and had evidently dragged out her letter, to read it again before he died.24

The episode Jacks describes undoubtedly happened, but there are problems with his account. On the 29th, the enemy lines were just over a mile north of Nantillois; the 119th could not possibly have run into the hostile artillery, which was positioned several miles yet further to the German rear, mostly around the towns of Romagne and Cunel.25 There was also no possibility that an American artillery column could pass through several regiments of friendly and hostile infantry without noticing. A much more likely explanation is offered by the version of Charles M. Engel, a private in Battery A of the 119th. According to him, the regiment was put under the command of the infantry, whose colonels ignorantly deployed the guns in broad daylight, without an opportunity for concealment or camouflage. “We were in direct sight of the enemy observation balloons and before our guns were in firing position the enemy opened fire on the second battalion and men were flying in the air before they knew what was happening and we lost more men right there than in any other action in our five steady months in action.”26 And indeed, the presence of German balloons is attested by many other American accounts. Thus is the same event interpreted differently by different eyewitnesses.

For the attack of the 79th to move forward at all, artillery support was crucial, especially counterbattery fire. At 11:15 a.m., the 158th Brigade’s artillery liaison officer sent to General Irwin asking for fire on Madeleine Farm at 11:30 a.m., to last for half an hour. Irwin ordered the 121st and 330th (French) Artillery Regiments to begin firing at the requested time. At the same time he sent a message to Kuhn saying that the firing could not begin at exactly 11:30 a.m., but it would stop at 12:00 noon in any event. “It will be heavy fire while fired. Tell Colonel to use his own batteries.” By the last sentence he meant the colonel commanding the 120th Artillery, which had been detailed to support the brigade. Kuhn, figuring that even with Irwin’s caveat the firing schedule was optimistic, commanded the 75s instead to start firing on the southern edge of the Bois de Cunel at 1:00 p.m. and end an hour later. The 155s would fire on “la Mamelle trench, upon Cunel village, and upon le Ville aux Bois farm until further orders.” At 12:45 p.m. Kuhn ordered Knowles, “Reorganize your command. We are having strong artillery fire in Bois de Cunel. Hold at all costs your position well in front of Nantillois–Bois de Beuge line.” But it is not clear that any bombardment actually materialized; six years later, researchers at the Army War College could find no evidence that it did.27

Lack of artillery was not the only impediment to progress; the men of the 315th were drifting to the rear. Around 2:00 p.m. Oury saw the flood of stragglers passing his PC and took action. “This retrograde movement was stopped by myself and Staff Officers as they passed my P.C. The Commanding Officer of the 315th Infantry was directed to reorganize his regiment and put it back in line. This was accomplished later in the afternoon.”28 Oury may have been an optimist but Knowles, the commanding officer in question, was a realist. At 3:00 p.m. he sent an assessment of his situation to Oury and Kuhn. Yes, stragglers were being collected, but most of them were merely searching for food and water. Machine gun ammunition was low. Men from the 314th, 316th, and 313th Infantry Regiments were mixed in with his own. His effective strength was down to 50 percent. Most tellingly:

Men are of good moral [sic], but badly exhausted, because of lack of food, water and sleep. Officers getting scarce, Med. officers left all in. Wounded with practically no help but 1st aid and many who could be saved are dying because of lack of attention and exposure. Supply train near my P.C., but unable to go further on account of shelling.29

An hour and a half later, Oury repeated his situation report but, apparently fearing that he had been too subtle, came to the point:

It is my opinion that now is the occasion for fresh troops to be sent in right away. The men are tired and against the evident resistance on our front will not get far under any circumstances. They will if ordered, of course, attempt to advance but this may develop the possibility of a stampede somewhere along the line.30

And, a little later:

Find that the casualties have been growing worse. Major Allen just killed by shell fire. We are lying in the open accomplishing nothing in our present positions, but getting men destroyed. Request that I be permitted to withdraw. The 2d and 3d Battalions, 315th Infantry, are falling back without orders.31

Oury’s terse summary of the plight of his casualties did not, of course, capture the despair of the afflicted men. Private Casper Swartz and another man of the 314th came across a wounded soldier who begged to be put out of his misery. Swartz was unwilling to shoot him; but as he stood there two stretcher-bearers came up. Swartz asked them to evacuate the wounded man but they refused, saying he was from a different outfit. Swartz said to his buddy, “Take aim on the one guy and I will take the other.” That stopped the stretcher-bearers in their tracks. Swartz said, “If you fellows start moving toward the rear without taking this wounded man along, we will kill both of you.” Without further objection, the former recalcitrants placed the casualty gently on their stretcher and took him to the rear.32 An intelligence specialist from First Army headquarters who had trained with the 313th Infantry watched as the wounded of the 79th—those lucky enough not to be left lying on the field—came in to the field hospital:

After dark, truck after truck arrived piled crisscross with wounded on stretchers, one row lengthwise on the bottom, another crosswise with ends on the body sides of the trucks. The drivers said that they had been forty-eight hours on the way in a drizzle. The distance is not so great but the roads are jammed and often impassible [sic] and they had to go carefully over the rough spots for fear of shaking these human wrecks to pieces. Many of them, when lifted out, certainly looked more dead than alive. One man’s face was covered with blood and his uniform stiff with clots. I thought he was dead, but it turned out to be blood that had dripped on him from the man above ... Minor wounds had to wait as the surgeons worked feverishly hour after hour trying to keep up with the incoming tide. Mud-caked, rain-soaked and blood-stained men lay silently row on row, patiently waiting their turn.33

Not all the wounds were physical. As the intelligence man looked for his former buddies among the casualties of the 313th:

I came across the most dejected kid I have ever seen. Pale as a ghost, smeared with grime, he sat against a wall and stared before himself as though in a trance; 313 “D” was on his collar button and he nursed a bandaged hand.

“What’s the matter, buddy, downhearted?” I asked. “‘D’ is my old company. I was with them for two months at Camp Meade. How is everybody?”

He looked up a moment gloomily and then continued to stare at the wall. “They’re all dead,” he said listlessly, “gassed and shelled—nobody left.”

“Aw, cheer up,” I said, “probably not that bad. You’ll find nine-tenths of them in hospital. Men don’t die that easily.”

He shook his head and looked as if he were about to burst into tears ... I could not shake him out of his dejection and so left him wrapped in gloom, convinced that all his comrades were no more and not comforted at all in that he had escaped with a minor hurt.34

Getting to a hospital was no guarantee of safety. At 2:00 p.m. a triage center opened at Fayel Farm, consisting of the 315th and 316th Field Hospitals. In the words of an intelligence officer on General Irwin’s staff, one hour later:

... a German plane circled slowly over the hospital which was plainly marked by large red crosses on top of the tents. Then, following each other at intervals of thirty seconds, ten German shells fell among the tents, eight being direct hits. Patients, litters and tents were scattered in all directions and numbers of men laying there helpless, but only slightly wounded, were killed outright or received mortal wounds. There was no hesitation on the part of the men near enough to help, and dozens rushed into the bursting shells and carried out the helpless to places of safety, cursing the maliciousness that could have instigated such inhuman fire.35

Twenty-one men died, several of them wounded German prisoners. Officers and men helped evacuate the wounded under fire; walking wounded gave their places in ambulances to those more seriously hurt. The patients were transferred to the former first aid station on the Avocourt–Malancourt road, but continued shelling forced the 315th and 316th Field Hospitals all the way back to Clair Chêne, where they had started out. Nine men of the 304th Sanitary Train were killed, some while attempting to retrieve the wounded from the field.*36

* The episode achieved notoriety in First Army as a typical German atrocity. A common reaction was that of Gerald F. Gilbert, an enlisted man in the 304th Sanitary Train: “Damn the Germans for such a dirty deed. I am in favor of killing every one of them ... They are the meanest, dirtiest, low-down people on earth and should be exterminated.” (Gerald F. Gilbert, Jr., untitled diary, n.d., World War I Survey, WWI-158, 304th Sanitary Train, AHEC, p. 67.) But the reality was likely different. Dr Hanson, now serving as assistant to the hospital’s commanding officer, noticed earlier in the day that the 1st Division, newly arrived at the Meuse–Argonne front, had camped across the road from the hospital. He immediately became upset, knowing that if the presence of the division was detected by the Germans, it would come under attack with inevitable damage to the hospital. Hanson got his chief to talk to the commander of the 1st Division, but the latter merely replied that they had been ordered up to help the infantry. (Hanson, I Was There, p.81.)

Most soldiers were neither dead nor wounded, but all were desperately hungry. The supply situation, which depended on the roads, had not abated. On September 29 Premier Clemenceau decided to visit Montfaucon, the greatest prize of the American offensive so far. He got within five miles, then became stuck in the enormous traffic jam that was starving First Army of guns, ammunition, and food. Angrily abandoning his car, he strode forward far enough to overlook the road north packed solid with vehicles, horses, and guns. He finally gave up in disgust, returned to his car (which took some effort to turn around) and went off to visit the more hospitable French sector nearby. It was perhaps fortunate for Pershing that Clemenceau got no further; he could not see the full extent of American disorganization. (In addition to Clemenceau, André Tardieu, the high commissioner for Franco-American cooperation, also wanted to visit Montfaucon, but Pershing dissuaded him. President Poincaré tried, but could get no further than Esnes.) The traffic jam behind the American front, Pétain’s observers reported to him, was “unimaginable.” Lieutenant Colonel Nodé-Langlois saw two regiments camped in the middle of the road. Some vehicles were stalled in place for up to 30 hours; when they moved, the average speed was two kilometers per hour. The road between Clermont and Baulny was blocked by two huge craters, and although alternate tracks had been cut into the neighboring fields, the going was so poor that many trucks broke down. The few military police were ineffective in enforcing road discipline—drivers simply ignored them. The only way to get obedience was with a drawn pistol.

A Colonel Bourgerie exclaimed, “And our policemen go to New York to learn traffic control!” Repair work on the badly damaged roads was poorly done; although plenty of laborers were available, they were poorly organized and equipped, and worked at cross-purposes. The Americans to whom the French protested, realizing the criticality of the situation, blamed the mud, the exhaustion of the troops, and the cross-traffic caused by the relief of the front-line units.37 But officers could also be a problem. Captain W.R. Eastman, a V Corps surgeon trying desperately to get forward to Montfaucon, found the direct route barred by the MPs. Instead, he was shunted to the one-way road going east to Avocourt:

Along came a big staff car in the opposite direction, pushed my little old Dodge off the plank road into the mud and went on. The next M.P. I asked why he had let that car go through. He replied that he had signalled for him to stop, that the officer had yelled to him that he had the right of way to Hell and pushed along. I hope he reached his destination. Have been looking for him ever since, but I have never run across him.38

Responding to the barrage of bad news from his brigade commanders, Kuhn sent a stiff order to Oury telling him to establish a defensive line near Nantillois, “if possible in the North thereof,”—over half a mile behind his present position on Hill 274. With regard to artillery support, Kuhn could offer little reassurance: “Corps has been informed of our situation and of the direction from whence the fire is coming and it is believed that some measure will be taken in the very near future by Corps or Army to afford relief.” He ended with a warning: “Rumors have been prevalent that the 79th Division is to be relieved. This rumor has no foundation in fact and must be suppressed.”39

The rumor was more accurate than Kuhn knew. At 12:45 p.m. the general had sent a message to Cameron at V Corps requesting that the 79th be relieved:

My whole line falling after advance on Ogons woods and troops on my right also reported retiring in some disorder due to concentration artillery crossfire and exhaustion of troops. Am reorganizing retiring units and am preparing to hold line in front of Nantillois against possible counter-attack. Request fresh divisions rushed forward at once.40

V Corps staff had forwarded the message on to Pershing’s headquarters with the note, “General Cameron does not recommend relief.” But First Army decided otherwise. At 4:30 p.m. Colonel Drum, Pershing’s Chief of Staff, issued Field Order No. 31 directing that the 3rd Division relieve the 79th in the line that night. The order was sent to V Corps. Kuhn, not knowing this, kept sending messages to Cameron indicating that he was still game as long as he got help:

It is my opinion that no advance by infantry is possible until effective counter battery work has been instituted. It has been impossible for the divisional artillery to cope with the situation. I deem it my duty to bring these matters to you attention in order that proper action may be taken in the premises ...41

And at 10:20 that night he told Oury not to expect relief any time soon:

Your message describing the conditions of your troops received. It is impossible to provide for any relieve [sic] this morning and I must impress upon you the necessity of exerting all your influence to maintain discipline and uphold the morale of the men. Every effort will be made to supply the men with rations. I hope to avoid calling on the men for any exertion beyond the requirements of security and protection of their line. The men have done well and it would be a pity should they fail to maintain discipline.42

Finally, at 3:30 a.m. on the morning of the 30th, Kuhn received V Corps’ order commanding the 3rd Division to relieve the 79th—all but the 304th Engineers, who would be attached to the 3rd for another week. He quickly sent notes to Nicholson and Oury telling them that the 5th Brigade of the 3rd Division was “marching to your relief” and ordering them to set up liaison arrangements.43 Three hours later he made this formal in his Field Order No. 10. The ordeal of the 79th—at least the September part of it—would soon be over.

The concern at First Army headquarters was much broader than the plight of the 79th. Pershing had been receiving reports of stagnation all along his line. From I Corps on the left he heard:

Infantry advancing from the corps objective met with determined resistance. The 77th Division on the left was unable to advance any distance through the forest. The 28th Div. was held approximately on the line it occupied yesterday. The 35th Div. attempted to move forward from Montrebeau [Woods] but was driven back by machine-gun and artillery fire.*44

* This was generous. The 35th Division had virtually disintegrated; its fate has been described in detail by Robert Ferrell. (Robert H. Ferrell, Collapse at Meuse–Argonne: The Failure of the Missouri-Kansas Division (Columbia, MO and London: University of Missouri Press, 2004).)

III Corps on the right reported:

All along our front the infantry met considerably more resistance. Very heavy M.G. and artillery fire prevented further advance during the day. At the closing of this report our line remains approximately the same.45

V Corps sent the hardly reassuring message, “Troops advancing slowly”; the details of its report dwelt on difficulties and delays.46 At 8:30 p.m. Colonel Willey Howell, Drum’s chief of intelligence, issued a situation estimate that began, “All day long on the 29th, the enemy has maintained himself by means of machine gun fire, artillery and counter attacks ... It is becoming quite obvious that his intention is to hold this ridge (Aprémont–Exermont–Cierges–Brieulles line) as long as he can do so.” After recapitulating the fruitless American attacks and repulses of the previous two days he concluded:

I believe that the Germans were overwhelmed by our original advance, but that the advance has been so mismanaged and has been so dilatory as to enable them to recover from their first surprise, to readjust and establish themselves in a defensive position, to bring up several reserve divisions and to commence a very much stronger defense than they were able to conduct at the start. We can expect, I think, no further withdrawal under present conditions. The great success of the French Fourth Army (on our left) will possibly attract some of the troops in our front to the front of that army, unless we continue to hammer at the enemy. However, on the other side, it seems that our proper action would be to cease this hammering, to reorganize our advance, and to renew our attack in an orderly manner with fresh troops.47

In reality, the German position on the 29th was not nearly as secure as Howell believed. In the sector of the 151st Infantry Regiment, confusion reigned. Regiments, battalions, and individual soldiers from three divisions were mixed randomly, and officers could not locate their commands. “At a few locations, groups of staff officers gathered to ask each other despairingly for news of their troops.”48 A massive attack by the American 37th Division forced the 212th Infantry to retreat before it itself was stopped. Gallwitz’s diary recorded a series of violent artillery bombardments and continuing infantry attacks by the Americans, requiring Fifth Army to commit its own reserves to restore the line.49 But it was clear to the German troops that they would not be overrun any time soon and morale, if not high, was sufficient in most units to ensure a vigorous defense. In particular, they had lost their fear of the tanks. Lieutenant Berger in the 150th Infantry wrote home about how his battalion stopped the tank attack of the American 37th Division in front of Cierges:

The tanks ... drove into our trench and one hit the dug-out entry with his gun. The situation became awkward. I drew my pistol and came close to one of the tanks in the road. Just as I stuck my pistol into the observation loophole, the crew noticed me and shut the loophole a moment before the shot. I felt rather stupid, but continued on next to the tank in case the loophole opened again. This did not happen, however. After a while several other people arrived with hand grenades and we brought the thing to a halt. I threw several grenades, which I had tied together with my handkerchief, beneath the caterpillar tracks of a second tank. It continued on about 50 paces, then the crew gave up. When the men saw that nothing happened to someone who was right up against the tanks—although one still had to watch out for the other tanks’ machine guns—it became a sport to take care of the tanks. Of 10 tanks, the battalion disposed of 7. The men even climbed on top and cried, ‘Give it to him! Give it to him!’ and so on. One man fell, unfortunately, and was run over. The American infantry, accompanied by our machine-gun and now also infantry fire, pulled back.50

By the end of the day, the regimental histories report, infantry attacks had ceased; the Americans contented themselves with periodic artillery bombardments.

Bowing to reality, Drum on Pershing’s instruction issued an order canceling further offensive action—although it did not read that way. First, it recited the good news. “The Allied attack has been successful all along the front ... Our left has completely repulsed the counterattack of a fresh hostile division and gained many prisoners.” Then came the important information:

2. The American First Army will continue the attack on further orders. . . .

3. (B) The III Corps, the V Corps and the I Corps:

(1) These corps will organize for further attack.

(2) They will organize for defense the line—Bois de Forges–Gercourt-et-Drillancourt–Bois-Jure–Dannevoux–Bois de Dannevoux–Bois de la Cote-Lemont–Bois de Brieulles–Nantillois–Bois de Beuge–etc. [Emphasis added.]51

In the parlance of First Army, “organize for further attack” meant dig in, relieve depleted units, resupply, and wait for orders. Four exhausted divisions—from west to east the 35th, 91st, 37th, and 79th—were taken out of the line. For all of them, this had been their first battle; their replacements were veterans. The 1st Division under Major General Charles P. Summerall took over from the 35th; it had been in France since July 1917, and had fought in every major American action including St Mihiel. The 32nd Division, commanded by Major General William G. Haan, had fought with the French in the Aisne–Marne and Oise–Aisne campaigns; it replaced the 37th and, a few days later, the 91st. The 3rd Division, the “Rock of the Marne,” had stopped the German advance at Château Thierry and then attacked beside the French at Aisne–Marne; commanded by Beaumont Buck, it assumed the sector of the 79th. Pershing’s lineup for the next phase of the offensive would be a much more capable, experienced army.

POSITIONS OF THE 79TH DIVISION’S REGIMENTS, NIGHTS OF SEPTEMBER 29 AND 30

Accounts began immediately of why the 79th Division failed to take Montfaucon on the first day or to advance further than seven miles in all. Two days after the relief, Colonel S.F. Dallam, the V Corps inspector, wrote to the AEF Inspector General saying that three things had stopped the attack: exhaustion and hunger; the strong defensive positions in the Bois des Ogons and the Madeleine Farm; and the heavy artillery fire from the flanks, which could not be countered because the faulty telephone network prevented the 79th from giving coordinates to their own artillery for counterbattery fire.52 Memoranda and reports by the division’s own officers told essentially the same story. Subsequent analyses added lack of training and lack of combat experience as major factors; the Assistant Inspector General wrote:

The 79th Division came under fire for the first time since its organization. More than half of its strength was made up of draftees of not more than 4 months service and considerable less of actual training due to time lost in transport from the US and in moving about while in France. As is the case with all green troops there was lacking the experience which comes only from thorough training or actual contact with the enemy.53

Another inspector’s report, commenting on the performance of the 79th and 37th Divisions, concluded:

There was confusion, there was lack of resolution. At times there were conditions bordering on panic. But the fact remains that these two green divisions, entering battle for the first time, crossed three highly organized enemy positions and captured a good many hundred prisoners each. Their maiden efforts were, under all the circumstances, all that could be expected.54

In May 1919, the Historical Section of the AEF General Staff assigned officers to walk the American battlefields and report their findings. Colonel C.F. Crain surveyed the Montfaucon sector and noticed that there were few shell holes in the southern edges of the woods in which German machine guns had been emplaced. He wrote in his report’s conclusion:

Considering this fact it seems to me, proven that the Infantry of the 79th division attacked the strong German machine gun positions with very little artillery support, and to this fact is due its disorganization and failure to take its objectives ... To recapitulate, the infantry of the 79th division attempted to capture the German positions with their bare hands.55

Crain’s criticism of the artillery was seconded by Colonel Lanza, who after the war wrote extensively on the subject. Narrow divisional zones limited firing essentially to straight ahead; batteries could not support adjacent divisions.* Deep no-fire zones allowed the enemy to operate unmolested and to arrange artillery fire in advance for their own counterattacks. Divided command of the artillery among the division, corps, and army made coordination difficult to impossible. The divisions themselves had insufficient artillery; this was especially a problem when facing counterattacks, because poor communications often rendered them unable to request assistance from corps or army guns. Most important, according to Lanza, was the failure to open each day with a preparatory bombardment, on the assumption that the Germans were retreating and if the Americans fired it would just slow down their infantry.56 Problems Lanza could have listed, but did not, included the failure of the infantry to give target coordinates to the artillery and the long delays in communication, which quickly made information obsolete.

* Captain Harry S. Truman, commanding a battery in the 35th Division, was threatened with court martial for destroying one German battery and disabling two others—they had been in the zone of the next-door 28th Division, and therefore off limits. The threat was not made good, and the veterans of the 28th remembered the favor when Truman ran for President in 1948. (Martin Gilbert, The First World War: A Complete History (New York: Henry Holt, 1994), p. 467.)

The French advisers, always fecund sources of criticism, went into great detail on the failings of the 79th. Major Paul Allegrini, the commander of the French Military Mission to the 79th, began his report with faint praise and progressed downward from there:

The infantry, whose morale is good, attacks with zeal; but it can’t be denied that it has not fulfilled its task; it has made progress but it has neither fought nor maneuvered: starting in effect from the moment the enemy stiffens its resistance, or the bombardment becomes more intense, the men are surprised, as if astonished to be shelled, whereas the bombardment is most frequently caused by their inexperience, which leads them to show their profile and to walk along crests, to bring the mobile kitchens close to the lines, and finally, to neglect to dig in; the pick and shovel were not handled by anyone.57

Whenever resistance developed, it was overcome “solely thanks to the assistance of the French tanks.” The infantry had not been trained in working with tanks, so when the tanks advanced, the infantry rarely followed, leading to the loss of ground. The top officers didn’t know their jobs—commanders got separated from their staffs, plans and orders were delivered late if at all. Not having worked with artillery or aircraft before the battle, the commanders did not know how to use them. The artillery, led by French officers, did fairly well, but on their own initiative and without target information from the infantry.* The support units knew nothing about mopping up, so the reserve regiments suffered losses after the assault troops had passed. Worst of all, no provision seemed to have been made for resupplying the men, who went for three days without food or water. Probably for this reason there were far too many stragglers, who greatly reduced the regiments’ front-line strength. But even Allegrini had to concede:

Despite all of the notable failings, despite the inadequate command, if one remembers that 60% of the men of the division had at most three months of service, that all of them had heard their first shell eight days before the attack, that they went from the impression of a very quiet sector, without a transition, to one of attack; one must admit that the attitude of the men of the division suited the occasion; that the attack succeeded; and that the division advanced as far as, if not further, than, the US divisions that surrounded it.

* The V Corps artillery was largely composed of French regiments and its commander, General René Alexandre, was French, as were several of the artillery battalions assigned to the 79th.

In one or two months, he predicted, the men of the 79th would be capable of doing quite well.†58

† Major Allegrini was not around to see his prediction come true. Tired of his carping, Kuhn wrote to the Adjutant General of the AEF in October asking that the major be assigned elsewhere. He was. (Joseph E. Kuhn, “Major Paul Allegrini, French Mission,” October 15, 1918, RG 120, Entry 6, Adjutant General File, General Correspondence, Box 1017, 20087, NARA, pp. 1–2.)

The Germans, not knowing of the difficulties behind the American lines, certainly knew they had been in a fight, and not a winning one. In their war diaries, combat reports, and regimental histories they wrote of a highly motivated if inexperienced enemy who, despite repeated setbacks and outright failures, just kept coming. No word here of American infantry cowering in trenches while French tanks did all the work; the tales told by officers and regimental historians are ones of unremitting and violent pressure from the enemy and constant, although stubborn, retreat by the Germans. An after-action report by the Operations Section of the 117th Division observed:

The division has very little combat value at the present time. After the arrival of replacements and a training period of 8 days, beginning then the division will be fit to be put in line or on a quiet front, after a training period of 5 weeks, on any front at all.59

The battalions in all three regiments were at about half-strength; trained crews were on hand for fewer than half of the machine guns. Although 1,300 recruits were available in the recruit depot, many of these were only 18 years old. Of the remainder, more than a hundred were to face courts-martial for mutiny.60 General Hoefer, the division commander, commended his troops:

Days of heavy fighting lie behind us. To all troops of the division who have fought valiantly during these days I express my highest commendation for their attainments. The units of the 11th Grenadiers and the 450th Infantry are to be praised especially, because, although enveloped on both sides, as a deep wedge they tenaciously held their positions south of Montfaucon for a long time and did not withdraw until so ordered.

But this was no triumph, as Hoefer continued:

If each one in his turn had fought as courageously as these brave men, the enemy assault would have been broken sooner. The voluntary surrender of positions, because the enemy has forced his way into the flank, is a blunder prompted by weakness and unsoldierly conduct toward those elements who bravely defended themselves ...61

Kuhn, also, had reason to be proud of his division. It had advanced six miles against heavy opposition, conquered the most heavily fortified portion of the German line, and taken over 900 prisoners.62 A few days after the relief he published the following message:

During the recent fighting the 79th Division received its first baptism of fire in the Montfaucon sector. The commanding general takes this means of expressing to his command his satisfaction and gratification for the courage, fortitude and tenacity displayed by all the troops, especially the infantry, which, though frequently subjected to heavy machine gun and artillery fire, not only held all the ground conquered but gallantly strove to advance whenever called upon to do so ... He feels confident that the 79th division will not fail to maintain its excellent record and that the experience gained in the recent fighting will be turned to profit when again confronting the enemy.63

Privately, however, the general was near despair. To his diary he confided:

More inspectors and I guess they are after me, OK. Looks like Blois or States with fewer stars. I have nothing for which to reproach myself and think division did well and showed grit and nerve.64

Blois was the reclassification center for American officers who had been relieved of duty. Being sent to Blois was a visible sign of failure.* To his wife he wrote:

The division did well in my opinion although it failed to fully accomplish the task set to it. God knows I did all I could to make things go but it would not quite connect. Four nights without sleep and a bad cold on top left me pretty well down & out but a good night’s rest last night has restored me greatly and I shall be OK shortly. Casualties were moderate but, as is always the case, some of the best and bravest are gone.65

* Pershing relieved many generals during the war, but Kuhn was not among them. In June 1917 he dismissed General William Sibert, an elderly engineering officer, from command of the 1st Division. In October 1918 he removed Beaumont Buck from command of the 3rd Division, Cameron from command of V Corps (sending him to lead the 4th Division upon the promotion of Hines to III Corps commander), and John McMahon of the 5th Division, all of them for displaying lack of spirit in their troops and themselves. Clarence Edwards, a politically appointed officer of the Massachusetts National Guard, was removed from command of the 26th for maintaining poor discipline, disloyalty, and generally being a nuisance. (Smythe, Pershing, p. 214.) Kuhn escaped their fate. Perhaps Pershing remembered the brilliant upperclassman of his Academy days. Perhaps Kuhn had earned the goodwill of the officer corps when, as president of the Army War College, he had recommended 120 colonels for promotion to general. (Millett, The General, p. 307; Joseph E. Kuhn to Col. Frederick Palmer, July 10, 1930, Kuhn Papers, Box 5, USMA, p. 1.) Or perhaps Pershing and his staff realized that they had ordered him to take an inexperienced, largely untrained, poorly supplied division and work wonders.

In fact, the 79th did no worse than most other divisions of First Army and better than some. The Meuse–Argonne offensive as a whole failed to achieve Pershing’s objectives. The plan for the initial advance had been for the three corps to reach the Army Objective—an advance of ten miles—on the afternoon of the first day, September 26. Instead, his divisions stalled nearly four miles short of their goal and would not reach it until mid-October. Many blamed V Corps—and the 79th in particular—for failing to capture Montfaucon and penetrate the German line that first day, thus allowing the enemy time to reinforce. Others were not sure it would have made a difference. The fall of Montfaucon would not have alleviated the traffic jams, which throttled supply lines and prevented the artillery from moving forward. Lieutenant Colonel Frederick Palmer, a war correspondent in Pershing’s headquarters, wrote:

There are those who say that if we had taken Montfaucon on the first day, we might have reached the crest of the whale-back [i.e, the Barrois plateau] itself on the second or third day and looked down on the apron sweeping toward the Lille–Metz railway ... They forget the lack of road repairs; the lack of shields [?] to continue the advance; and the interdictory shell-fire which the enemy laid down on the ruins of the town and on the arterial roads which center there. If we had taken Montfaucon on the first day, I think there would still have been a number of other ‘ifs’ between us and the crest.66

Indeed, apart from the 79th Division’s lack of training and experience, it suffered from the same ills that plagued the other divisions: ignorance of combined-arms operations, poor communications leading to defective artillery support, and, above all, failure to maintain the roads. As we have seen, all offensives in World War I—even the apparently successful ones, from Moltke’s advance to the Marne in 1914 to Ludendorff’s Spring Offensives—were limited by their supply lines.* Sooner or later, generally after an advance of no more than ten miles, the men would run out of food and ammunition. Moreover, the disorganization that resulted from an attack would have to be sorted out before the operation could continue much further; even the victorious British and French offensives north of the Meuse–Argonne ground to a halt in the first week of October. Had the 79th taken Montfaucon on the first day, First Army would have stopped shortly thereafter anyway, strangled by its own lack of supplies. A balanced judgment has been offered by the historian Martin Gilbert: “By former Western Front standards the Americans were successful. Montfaucon, which Pétain had believed could hold out until the winter, was taken on September 27, and advances were made of up to six miles. But the plan had been far more ambitious, making the set-back all the more galling.”†67

* See Chapter 7, p. 169.

† The idea that Pétain thought Montfaucon could hold out until winter is often repeated in American World War I histories; see, e.g., Edward M. Coffman, The War to End All Wars: The American Military Experience in World War I (New York: Oxford UP, 1968), p. 301. It appears to be a slight distortion of a sentence in Pershing’s memoirs: “In the event that we should attack between the Meuse and the Argonne, Pétain thought all that could be done before winter would be to take Montfaucon.” (Pershing, My Experiences, vol. 2, p. 253.) No one seems to offer an original source for Pétain’s opinion.

The failure of the 4th Division to “turn Montfaucon” by attacking into the zone of V Corps, as Pershing’s Field Order No. 20 had prescribed, was debated within the AEF at the time but was ultimately smoothed over in the official record. It will be recalled that General Alfred Bjornstad, chief of staff of III Corps, canceled the movement because he did not want to violate corps boundaries (see Chapter 11). Drum and Pershing therefore blamed III Corps for not making the attack. General Bullard, the III Corps commander, replied that First Army had, in effect, canceled the attack by insisting that all corps advance straight to the Army Objective. In the words of historian Alan Millett, “General Drum’s ingenuous defense of Army headquarters was that the III Corps should have understood that it had the freedom to cross corps boundaries without Army approval. Such a response from Drum was self-serving, for he had insisted in practice on a high degree of Army control over the corps’ movements. It was not the first or last time he and Pershing disassociated themselves from schemes of maneuver that had turned sour.”68

R.T. Ward, the colonel in Pershing’s Operations Section who had written the attack plan for the Meuse–Argonne, was diplomatic in his final report: “Corps boundaries were given on the operation map and also division lines. Possibly there was a misunderstanding at times as to what these division lines meant. These lines were intended to show the army conception of the maneuver and were not intended to act as barriers between corps and division and thus limit their operations and prevent lateral maneuver.”69 Pershing picked up the “misunderstanding” theme in his memoirs. Of the 4th Division he wrote, “It was abreast of Nantillois and its left was more than a mile beyond Montfaucon, but through some misinterpretation of the orders by the III Corps the opportunity to capture Montfaucon that day was lost.”70 In fact, the lost opportunity was due to Pershing’s own failure and that of his staff to communicate his intentions clearly to his three corps commanders and to make sure that the corps’ own orders reflected those intentions. But the whole issue was a red herring. As Edward M. Coffman has pointed out, had the attack of the 4th Division gone forward, Nantillois would have fallen a day earlier, but the offensive would have bogged down anyway.71

Oblivious to the challenges faced by First Army and the fact that their own offensives had stalled, the Allied leaders redoubled their criticisms of Pershing after the Meuse–Argonne offensive bogged down. Haig blamed “inexperience and ignorance on the part of the Belgian and American Staffs of the needs of a modern attacking force.”72 Clemenceau, who still resented Pershing’s resistance to amalgamation, wrote to Foch:

The French Army and the British Army, without a moment’s respite, have been daily fighting, for the last three months ... but our worthy American allies, who thirst to get into action and who are unanimously acknowledged to be great soldiers, have been marking time ever since their forward jump on the first day; and in spite of heavy losses, they have failed to conquer the ground assigned them as their objective. Nobody can maintain that these fine troops are unusable; they are merely unused.73

But those closer to the action were more generous. On November 1, General Edmond Buat, Pétain’s chief of staff, said to Major Paul H. Clark, Pershing’s liaison officer:

When I learned that your army were to undertake the operations you assumed last September, I said it is prodigious ... You made mistakes and had difficulties certainly, but why not? Are you supermen? Are you Americans Gods that you can do the miraculous? If you had not had the difficulties that you did have I would certainly have said you were miracle workers ... given the conditions that existed—enemy—terrain—degree of training there are no other troops in the world who would have given one half the result that the US army did give.74

A modern French historian renders a favorable decision on the performance of the AEF in the Meuse–Argonne. André Kaspi points out that attacking in the Argonne was Foch’s idea, not Pershing’s. All of the AEF’s previous preparations were aimed at continuing its offensive eastward toward Metz and Briey. To oblige Foch, Pershing turned his army into the right wing of a combined Allied offensive and successfully shifted half a million men westward in two weeks. “No one has ever denied them this glory.” Furthermore, the Americans achieved substantial results, even if those did not amount to the spectacular victory that they later claimed. They learned as they went and passed through the crises that all improvised armies encounter. As Pétain grudgingly admitted to Foch on October 12, “Some organizational improvements have been made. They would have been more perceptible and faster if an inordinate national pride had not impeded the influence that the French officers assigned to the American staffs should legitimately have exercised.”75

The American offensive had gotten stuck, but Ludendorff could take no comfort from the fact. Already on September 16, the German army group commander in Macedonia had warned of an imminent collapse in the face of a Franco-Serbian offensive; but at the time Ludendorff and Hindenburg could not be distracted from trying to figure out what Foch’s plans for a September offensive were about.76 On September 28, as the two of them assessed the military balance in their headquarters at Spa, things looked bleaker than ever. The French, British, and Americans were continuing their advances against the Germans’ main line of defense in the West. In his memoirs, Ludendorff wrote:

In Champagne and on the western bank of the Meuse a big battle had begun on the 26th of September, French and American troops attacking with far-reaching objectives. West of the Argonne we remained masters of the situation, and fought a fine defensive battle. Between the Argonne and the Meuse the Americans had broken into our positions. They had assembled a powerful army in this region, and their part in the campaign became more and more important.77

In the south and east, an Italian offensive against a weakened Austria-Hungary was imminent. The Turks had abandoned Amman (in present-day Jordan) on the 25th and the next day Bulgaria had asked for an armistice, increasing the despair of the civilian populace. This was shown by the collapse of the Berlin Stock Exchange, which had held steady in the face of German military reverses since early August. The worst worry, however, was the naked vulnerability of the Balkan front, where an unhindered Allied advance to the Danube from Greece seemed a real possibility.*78 As Ludendorff studied the situation with his staff his agitation increased until he fell to the floor, convulsing and foaming at the mouth. That evening he had recovered just enough to conclude that he must ask for an armistice. This was Ludendorff’s second “black day,” and unlike the first he never recovered.

* Brook-Shepherd and others cite Ludendorff’s memoirs as proof that only the disasters on the Eastern Fronts caused his decision to seek negotiations. (Gordon Brook-Shepherd, November 1918 (Boston, Toronto: Little, Brown, 1981), p. 201.) It is true that Ludendorff cites the threat to Serbia, Hungary, and Turkey, to Rumanian neutrality, and Austro-Hungarian weakness as his immediate reasons. But his recital of the situation in France a couple of pages later makes it clear that fear of a breakthrough by the western Allies was a large part of his motivation as well. Colonel Albrecht von Thaer, Ludendorff’s chief of staff, met with him on October 1; his diary shows Ludendorff to have been desperately worried about the imminent collapse of the Western Front, partly as a result of the fresh American troops. (Albrecht von Thaer, “Diary Notes of Oberst Von Thaer, 1 October 1918,” www.lib.byu.edu/~rdh/wwi/1918/thaereng.html, accessed December 2, 1998.)

Having ordered his regiments to await relief, Kuhn decided to make no further attacks on the 30th. This was not easy; German shells, unimpeded by American counterbattery fire, continued to fall on the hastily constructed defensive line, which was held by the 311th and 312th Machine Gun Battalions and two platoons of the 310th Machine Guns—normally assigned in support, not as the main defensive units. Fortunately, no counterattack materialized. Food finally arrived and the men ate their first good meal since the jumpoff four days earlier.

Throughout the afternoon the troops of the 3rd Division replaced Kuhn’s worn-out regiments. Shelling and bad roads had prevented the 3rd from arriving in time to effect the relief at night, so it was done in broad daylight. To the amazement of Kuhn’s men, the columns of the 3rd marched up the roads under shell fire, then deployed in combat formation as they approached the trenches. In the words of a lieutenant in the Machine Gun Company of the 314th, “It was an inspiring sight to see those long thin waves billowing forward without hesitation, pressing onward with guns slung as if on a casual promenade. But, however spectacular, it was an entirely uncalled-for procedure to carry out a relief in this manner in the light of day while subject to enemy fire.”79 Men of the 3rd died uselessly as a result.

By 6:00 p.m. all four infantry regiments had left the line and started their march to the rear. Only two companies of the 311th Machine Gun Battalion remained, not to be relieved until the morning of October 1. Lieutenant Joel of the 314th described the procession:

Hoboes could hardly look more uncouth than the columns of soldiers trailing over the ruins of Montfaucon on the evening of September 30th. With seven-day beards, clothing ripped and shredded by barbed wire, and a thick coating of Argonne mud cemented to the hide with perspiration, the men hardly looked human. Everyone was emaciated and hollow-eyed, most of them suffering from bad colds and related ills. Swollen feet and stiffened muscles were the common lot of all. Guns and bayonets were covered with thick layers of rust. Even the ordinarily well-dressed officers were hardly presentable to a self-respecting hobo.80

The 304th Engineers made it as far as Malancourt when the order came through from V Corps reassigning them temporarily to the 3rd Division; worn out by five days of heavy manual labor as well as combat, they had to retrace their steps to the front.

Those who could stagger to the rear were, of course, the lucky ones. The division lost many men in its five days of action, but the actual numbers are unclear. Immediately after being relieved, the 79th reported its losses as 149 officers and 4,966 men killed, wounded, or missing, but there was little basis for these figures.81 Certainly Kuhn’s September 30 estimate of a 50 percent reduction in strength included several thousand stragglers and those wounded who had reached first aid stations or hospitals without being counted. After the war the US Army Medical Department reported that the division lost 597 killed, 2,375 wounded, and 473 gassed between September 26 and 30, including those who subsequently died of wounds.82

As the men of the 314th Infantry trudged back through Montfaucon, the battle offered up a final, bizarre event for their contemplation. A solitary enemy airplane had been flying over the German lines for some time, unmolested by Allied fighters or antiaircraft fire. Suddenly it crumpled, burst into flames, and “spun like a pinwheel to earth—a mass of fire.”83 Perhaps it was hit by one of the Germans’ own high explosive shells, or perhaps the gasoline tank caught fire. To the hungry, exhausted soldiers it was just one more apparently pointless event at which to wonder.