1 Globalization then and now

Globalization is a relatively new word which describes an old process: the integration of the global economy that began in earnest with the launch of the European colonial era five centuries ago. But the process has accelerated over the past 30 years with the explosion of computer technology, the dismantling of barriers to the movement of goods and capital, and the expanding political and economic power of transnational corporations.

More than five centuries ago, in a world without electricity, cellphones, antibiotics, refrigeration, wifi, automobiles, jet aircraft or nuclear weapons, one man had a foolish dream. Or so it seemed at the time. Cristóbal Colón, an ambitious young Genoese sailor and adventurer, was obsessed with Asia – a region about which he knew nothing, apart from unsubstantiated rumors of its colossal wealth. Such was the strength of his obsession (some say his greed) that he was able to convince the King and Queen of Spain to bankroll a voyage into the unknown across a dark, seemingly limitless expanse of water then known as the Ocean Sea. His goal: to find the Grand Khan of China and the gold that was rumored to be there in profusion.

Centuries later, Colón would become familiar to millions of schoolchildren as Christopher Columbus, the famous ‘discoverer’ of the Americas. In fact, the ‘discovery’ was more of an accident. The intrepid Columbus never did reach Asia – not even close. Instead, after five weeks at sea, he found himself sailing under a tropical sun into the turquoise waters of the Caribbean, making his landfall somewhere in the Bahamas, which he promptly named San Salvador (the Savior). The place clearly delighted Columbus’ weary crew. They loaded up with fresh water and unusual foodstuffs. And they were befriended by the island’s indigenous population, the Taíno.

‘They are the best people in the world and above all the gentlest,’ Columbus wrote in his journal. ‘They very willingly showed my people where the water was, and they themselves carried the full barrels to the boat, and took great delight in pleasing us. They became so much our friends that it was a marvel.’1

Twenty years and several voyages later, most of the Taíno were dead and the other indigenous peoples of the Caribbean were either enslaved or under attack. Globalization, even then, had moved quickly from an innocent process of cross-cultural exchange to a nasty scramble for wealth and power. As local populations died off from European diseases or were literally worked to death by their captors, thousands of European colonizers followed. Their desperate quest was for gold and silver. But the conversion of heathen souls to the Christian faith gave an added fillip to their plunder. Eventually European settlers colonized most of the new lands to the north and south of the Caribbean.

Columbus’ adventure in the Americas was notable for many things, not least his focus on extracting as much wealth as possible from the land and the people. But, more importantly, his voyages opened the door to 450 years of European colonialism. And it was this centuries-long imperial era that laid the groundwork for today’s global economy.

Colonial roots

Although globalization is now a commonplace term, many people would be hard-pressed to define what it actually means. The lens of history provides a useful beginning. Globalization is an age-old process and one firmly rooted in the experience of colonialism. One of Britain’s most famous imperial spokespeople, Cecil Rhodes, put the case for colonialism succinctly and brazenly in the 1890s. ‘We must find new lands,’ he said, ‘from which we can easily obtain raw materials and at the same time exploit the cheap slave labor that is available from the natives of the colonies. The colonies [will] also provide a dumping ground for the surplus goods produced in our factories.’2

During the colonial era European nations spread their rule across the globe. The British, French, Dutch, Spanish, Portuguese, Belgians, Germans, and later the Americans, took possession of most of what was later called the Third World. And of course they also expanded into Australia, New Zealand/Aotearoa and North America. In some places (the Americas, Australia, New Zealand and southern Africa) they did so with the intent of establishing new lands for European settlement. Elsewhere (Africa and Asia) their interest was more in the spirit of Rhodes’ vision: markets and plunder. From 1600 to 1800 incalculable riches were siphoned out of Latin America to become the chief source of finance for Europe’s industrial revolution.

Global trade expanded rapidly during this period as colonial powers sucked in raw materials from their new dominions: furs, timber and fish from Canada; slaves and gold from Africa; sugar, rum and fruits from the Caribbean; coffee, sugar, meat, gold and silver from Latin America; opium, tea and spices from Asia. Ships crisscrossed the oceans. Heading towards the colonies, their holds were filled with settlers, administrators and manufactured goods; returning home, the stout galleons and streamlined clippers bulged with coffee, copra, cotton and cocoa. By the 1860s and the 1870s world trade was booming. It was a ‘golden era’ of international commerce – though the European powers pretty much stacked things in their favor. Wealth from their overseas colonies flooded into France, England, Holland and Spain while some of it also flowed back to the colonies as investment – in railways, roads, ports, dams and cities. Such was the range of global commerce in the 19th century that capital transfers from North to South were actually greater at the end of the 1890s than at the end of the 1990s. By 1913 exports (one of the hallmarks of increasing economic integration) accounted for a larger share of global production than they did in 1999.

Expanding international trade

When people talk about globalization today they’re still talking mostly about economics, about an expanding international trade in goods and services based on the concept of ‘comparative advantage’. This theory was first developed in 1817 by the British economist David Ricardo in his Principles of Political Economy and Taxation. Ricardo wrote that nations should specialize in producing goods in which they have a natural advantage and thereby find their market niche. He believed this would benefit both buyer and seller but only if certain conditions were maintained, such as: 1) trade between partners must be balanced so that one country doesn’t become indebted and dependent on another; and 2) investment capital must be anchored locally and not allowed to flow from a high-wage country to a low-wage country.

Unfortunately, in today’s high-tech world of instant communications, neither of these key conditions exists. Ricardo’s blend of local self-reliance mixed with balanced exports is nowhere to be seen. Instead, export-led trade dominates the global economic agenda. The only route to increased prosperity, say the ‘experts’, is to expand exports to the rest of the world. The rationale is that all countries and all peoples eventually benefit from more trade.

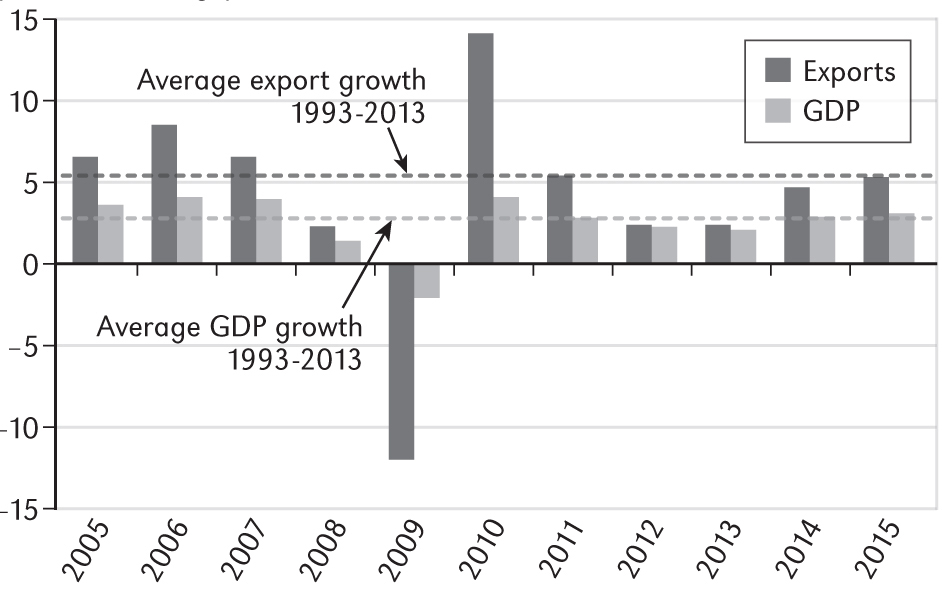

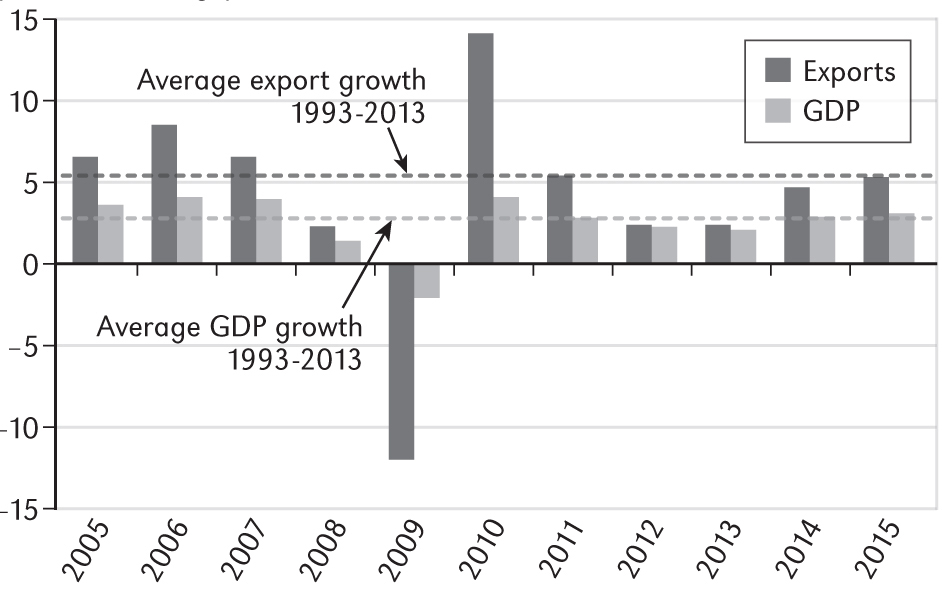

When the world economic crisis erupted in 2008, international trade slumped for the first time in living memory. According to the World Trade Organization (WTO), trade in Europe fell by nearly 16 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2008 while global trade fell by more than 30 per cent in the first quarter of 2009. But this was an anomaly. During the 1990s world trade grew by an average 6.6 per cent yearly and from 2000 on it averaged more than 6-per-cent growth a year. On average, trade after 1950 expanded twice as fast as world GDP. Unfortunately, most of this wealth ended up in the hands of the rich developed nations. They account for the lion’s share of world trade and they mostly trade with each other. According to the WTO, in 2013 Europe and North America together accounted for nearly 50 per cent of global merchandise exports and 61 per cent of commercial service exports.3

Colonialism in the Americas separated Indians from their land, destroyed traditional economies and left native people among the poorest of the poor.

• The Spanish ran the Bolivian silver mines with a slave labor system known as the mita; nearly eight million Indians had died in the Potosí mines by 1650.

• Suicide and alcoholism are common responses to social dislocation. Suicide rates on Canadian Indian reserves are 10 to 20 times higher than the national average.

• In Guatemala the infant mortality rate among indigenous people is 30% higher than for the non-indigenous population. Maternal mortality is almost 10 times higher among indigenous people. (cesr.org)

Indian Population of the Americas: 1492 and 1992

SEDOS Bulletin, Rome, May, 1990; The Dispossessed, Geoffrey York (Lester & Orpen Dennys, Toronto, 1989); Guatemala: False Hope, False Freedom, James Painter (CIIR, London, 1987); Ecuador Urgent Action Bulletin (Survival International, London, 1990); Native Population of the Americas in 1492, Ed. W. Denevan (University of Wisconsin Press, 1976) and GAIA Atlas of First Peoples, Julian Burger (Doubleday, New York, 1990).

Nonetheless, the world has changed in the last century in ways that have completely altered the character of the global economy and its impact on people and the natural world. Today’s globalization is vastly different from both the colonial era and the immediate post-World War Two period. Even arch-capitalists like currency speculator George Soros have voiced doubts about the values that underlie the direction of the modern global economy.

‘Insofar as there is a dominant belief in our society today,’ he writes, ‘it is a belief in the magic of the marketplace. The doctrine of laissez-faire capitalism holds that the common good is best served by the uninhibited pursuit of self-interest…Unsure of what they stand for, people increasingly rely on money as the criterion of value…The cult of success has replaced a belief in principles. Society has lost its anchor.’

The inefficient magic of the marketplace

The ‘magic of the marketplace’ is not a new concept. It’s been around in one form or another since the father of modern economics, Adam Smith, published his pioneering work The Wealth of Nations in 1776. (Coincidentally, in that same year, Britain’s 13 restless American colonies declared independence from the motherland.) But Smith’s concept of the market was a far cry from the one championed by today’s globalization boosters. Smith was adamant that markets worked most efficiently when there was equality between buyer and seller, and when neither was large enough to influence the market price. This, he said, would ensure that all parties received a fair return and that society as a whole would benefit through optimal use of its natural and human resources. Smith also believed that capital was best invested locally so that owners could see what was happening with their investment and could have hands-on management of its use. Author and activist David Korten sums up Smith’s thinking as follows: ‘His vision of an efficient market was one composed of small owner-managed enterprises located in the communities where the owners resided. Such owners would share in the community’s values and have a personal stake in its future.’4 Smith’s understanding of the market bears little similarity to today’s globalized economy, dominated by faceless mega-corporations with marginal ties to the local community. Corporate managers make decisions aimed at increasing shareholder value while ownership is vested in mysterious holding companies and distant financial conglomerates.

As Korten hints, our world is vastly different from the one that Adam Smith inhabited. Take the revolution in communications technology which only began around 1980. In less than four decades, mind-boggling advances in digital technology, software and satellite communications have radically altered the production, marketing, sales, and distribution of goods and services as well as patterns of global investment. Coupled with improvements in air freight and ocean transport, companies can now move their offices and factories to wherever costs are lowest. Being close to the target market still counts but it is no longer vital. Improved technology and relatively inexpensive oil (for the moment, anyway) have led to a massive increase in goods being transported by air and sea. The United Nations’ International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) notes that global air traffic has doubled in size every 15 years since 1977. The agency predicts that it will double again by 2030. ‘The 3.1 billion airline passengers carried in 2013 are expected to grow to about 6 billion by 2030, and the number of departures is forecast to grow from 32 million in 2013 to some 60 million in 2030.’5 Airbus, the giant European aircraft manufacturer, predicts that air-freight traffic will continue to grow by five per cent yearly, mainly in so-called ‘emerging’ economies. Increased ‘South-to-South’ trade flows, Airbus says, will make up 16 per cent of global air freight by 2033.6

The global shipping business, which now consumes more than 140 million tons of oil a year, is expected to rebound dramatically once the global economy gets back on track. And costs are falling.

According to the Washington-based World Shipping Council, approximately 1,500 shipping companies make 26,000 US port calls a year while more than 50,000 container loads of imports and exports from 175 countries are handled each day. From 1990 to 2005, rates on the three major US trade shipping routes fell by between 23 and 46 per cent.

International trade is expanding faster than the world’s economic output. This trade is seen as one of the main ‘engines’ of economic growth.

Growth in the volume of world merchandise trade and GDP, 2005-15 (annual % change)

Source: WTO Press Release, ‘Modest trade growth anticipated for 2014 and 2015 following two year slump’, 14 April 2014.

It is not hyperbole to suggest that containerized shipping both changed the shape of industrial production and spurred globalization. When the container was introduced in 1956, the world was full of small manufacturers selling locally, much like Smith’s ideal. A half century later local markets had mostly evaporated as plunging shipping costs opened up the global market. Combined with cheap labor, it meant the cost of long-distance shipping was no longer an issue. A garment factory in Bangladesh could fill an order for 10,000 shirts from Target, Sears or Marks and Spencer for a fraction of the cost of a local manufacturer. You could call it the ‘footloose’ phase of capitalism. Companies could bounce from country to country in search of cheap labor, low taxes and investment ‘incentives’ from job-hungry national governments.

Ocean-freight unit costs have fallen by 70 per cent since the 1980s, while air-freight costs have fallen by three to four per cent a year on average in recent decades.

These cheap transport rates reflect ‘internal’ costs – packaging, marketing, labor, debt and profit. But they don’t reflect the ‘external’ impact on the environment of the irreplaceable fossil fuels used to power jet airliners and ocean freighters. Moving more goods around the planet increases pollution, contributes to ground-level ozone (ie smog) and boosts greenhouse-gas emissions, a major source of global warming and climate change. These ecological costs are basically ignored in the profit-and-loss equation of business. This is one of the main reasons environmentalists object to the globalization of trade. Companies make the profits but society has to foot the bill.

Enter the free-market fundamentalists

The other key to recent globalization springs from structural changes to the world economy that have occurred since the late 1970s. It was then that the system of rules set up at the end of World War Two to manage global trade collapsed. The fixed currency-exchange regime agreed at Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, in 1944 gave the world 35 years of relatively steady economic growth.

If there’s a Third World, then there must be a First and Second World too. When the term was first coined in 1952 by the French demographer, Alfred Sauvy, there was a clear distinction, though the differences have become blurred over the past few decades. Derived from the French phrase, tiers monde, the term was first used to suggest parallels between the tiers monde (the world of the poor countries) and the tiers état (the third estate or common people of the French revolutionary era). The First World was the North American/European ‘Western bloc’ while the Soviet-led ‘Eastern bloc’ was the Second World. These two groups had most of the economic and military power and faced off in a tense ideological confrontation commonly called the ‘Cold War’. Third World countries in Africa, Latin America, Asia and the Pacific had just broken free of colonial rule and were attempting to make their own way rather than become entangled in the tug-of-war between East and West. Since the break-up of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s the term Third World has less meaning and its use is diminishing. Now many refer to the ‘developing nations’, the Majority World or just the South.

But around 1980 things began to shift with the emergence of fundamentalist free-market governments in Britain and the US, and the disintegration of the state-run command economy in the Soviet Union. The formula for economic progress adopted by the administrations of Margaret Thatcher in the UK and Ronald Reagan in the US called for a drastic reduction in the regulatory role of the state. According to their intellectual influences, Austrian economist, Friedrich Hayek, and University of Chicago academic, Milton Friedman, meddlesome big government was the problem. Instead, government was to take its direction from the market. Companies must be free to move their operations anywhere in the world to minimize costs and maximize returns to investors. Free trade, unfettered investment, deregulation, balanced budgets, low inflation and privatization of publicly owned enterprises were trumpeted as the six-step plan to national prosperity.

The deregulation of world financial markets went hand in hand with an emphasis on free trade. Banks, insurance companies and investment dealers, whose operations had been mostly confined within national borders, were suddenly unleashed. In London, deregulation took place on 24 October 1986 and was quickly dubbed the ‘Big Bang’. Within a few years, major players from Europe, Japan and North America expanded into each other’s markets as well as into the newly opened and fragile financial-services markets in the Global South. Aided by sophisticated computer systems (which made it easy to transfer huge amounts of money at the click of a mouse) and governments desperate for investment, the big banks and investment houses were quick to invest surplus cash anywhere they could turn a profit. In this new relaxed atmosphere, finance capital became a profoundly destabilizing influence on the global economy.

Instead of long-term investment in the production of real goods and services, speculators in the global casino make money from money – with little concern for the impact of their investments on local communities or national economies. Governments everywhere now fear the destabilizing impact of this ‘hot money’ which can come and go at the drop of a hat. The collapse of 2008 – the most devastating since the Great Depression of the 1930s – is just the latest in a long chain of financial disasters. Recent UN studies show a direct correlation between the frequency of financial crises and the huge increase in international capital flows from 1990 to 2010.

The East Asian financial crisis

The collapse of the East Asian currencies, which began in July 1997, was a catastrophic example of the damage caused by nervous short-term investors. Until then the ‘tiger economies’ of Thailand, Taiwan, Singapore, Malaysia and South Korea had been the success stories of globalization. Advocates of open markets pointed to these countries as proof that classic capitalism would bring wealth and prosperity to millions in the developing world – though they conveniently ignored the fact that in all these countries the State took a strong and active role in the economy. According to dissident ex-World Bank Chief Economist Joseph Stiglitz: ‘The combination of high savings rates, government investment in education and state-directed industrial policy all served to make the region an economic powerhouse. Growth rates were phenomenal for decades and the standard of living rose enormously for tens of millions of people.’7

Foreign investment was tightly controlled in the ‘tiger economies’ until the early 1990s, severely in South Korea and Taiwan, less so in Thailand and Malaysia. Then, as a result of continued pressure from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and others, the ‘tigers’ began to open up their capital accounts and private-sector businesses began to borrow heavily.

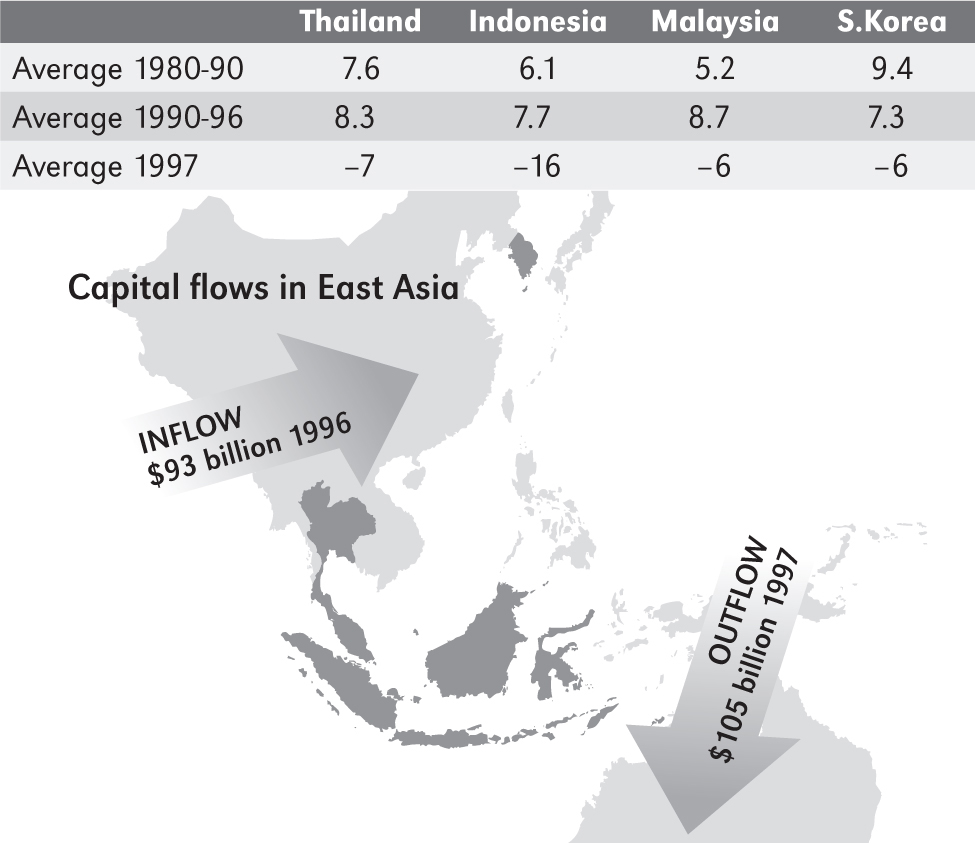

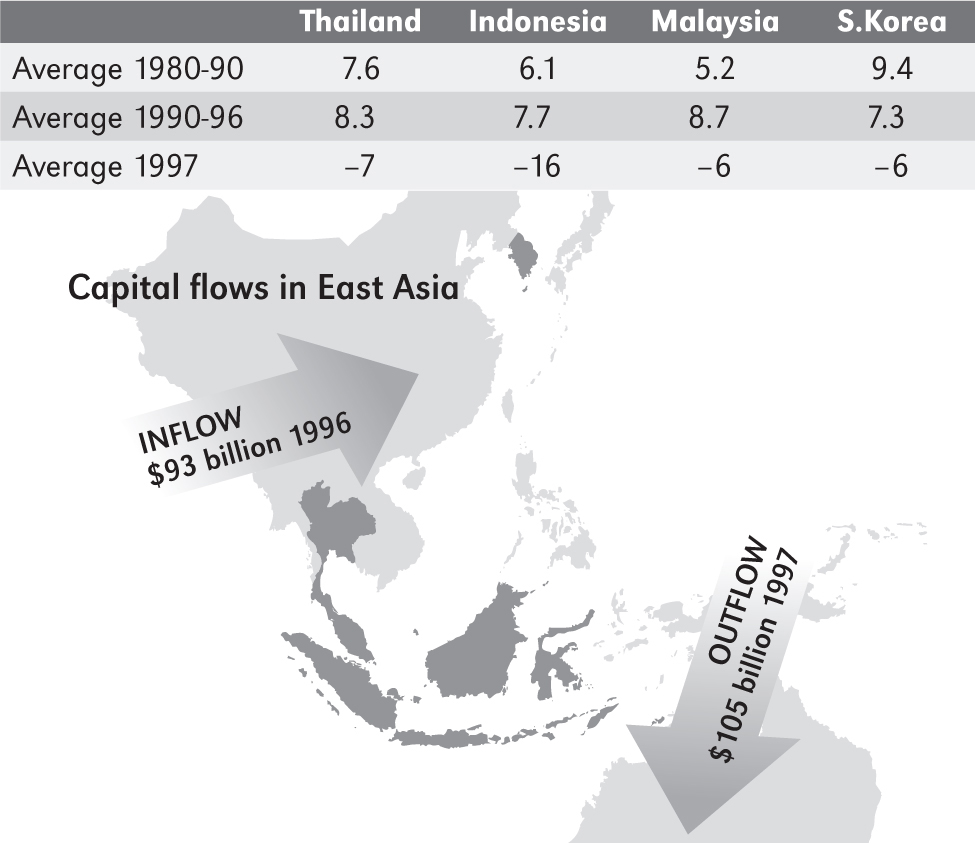

Spectacular growth rates floated on a sea of foreign investment as offshore investors poured dollars into the region, eager to harvest double-digit returns. In 1996, capital was flowing into East Asia at almost $100 billion a year. But mostly the cash went into risky real-estate ventures or into the local stock market where it inflated share prices far beyond the value of their underlying assets.

In Thailand, where the Asian ‘miracle’ first began to sour, over-investment in real estate left the market glutted with $20 billion worth of unsold properties. The house of cards collapsed when foreign investors began to realize that Thai financial institutions to which they had lent billions could not meet loan repayments. Spooked by the specter of falling profits and a stagnant real-estate market, investors called in their loans and cashed in their investments – first slowly, then in a panic-stricken rush.

More than $105 billion left the region in the next 12 months, equivalent to 11 per cent of the domestic output of the most seriously affected countries – Indonesia, the Philippines, South Korea, Thailand and Malaysia.8 Having abandoned capital controls, Asian governments were powerless to stop the massive hemorrhage of funds. Ironically, the IMF’s 1997 Annual Report, written just before the crisis, singled out Thailand’s ‘remarkable economic performance’ and ‘consistent record of sound macroeconomic policies’.

The IMF was to be proven wrong – disastrously so. Across the region economic output plummeted while unemployment soared, leaping by a factor of 10 in Indonesia alone. The human costs of the East Asian economic crisis were immediate and devastating. As bankruptcies soared, firms shut their doors and millions of workers were laid off. More than 400 Malaysian companies declared bankruptcy between July 1997 and March 1998 while in Indonesia – the poorest country affected by the crisis – 20 per cent of the population, nearly 40 million people, were pushed into poverty. The impact of the economic slowdown had the devastating effect of reducing both family income and government expenditures on social and health services for years afterwards. In Thailand, more than 100,000 children were yanked from school when parents could no longer afford tuition fees. The crash also had a knock-on effect outside Asia. Shock-waves surged through Latin America, nearly tipping Brazil into recession while the Russian economy suffered worse damage. Growth rates slipped into reverse and the Russian ruble became nearly worthless as a medium of international exchange.

The East Asian crisis was a serious blow to the ‘promise’ of globalization – and a stiff challenge to the orthodox economic prescriptions of the IMF. Indeed, in retrospect, the Asian meltdown of 1997-98 can be seen as a warm-up for the debacle of 2007-09. Across the region, the Fund was reviled as the source of the economic disaster. The citizens of East Asia saw their interests ignored in favor of Western banks and investors. In the end, writes Stiglitz: ‘It was the IMF policies which undermined the market as well as the long-run stability of the economy and society.’

It was the first time that the ‘global managers’ and finance kingpins showed that the system wasn’t all it was made out to be. The world economy was more fragile, and thus more explosive, than anybody had imagined. As the region slowly recovered, citizens around the world began to scratch their heads and wonder about the pros and cons of globalization, especially the wisdom of unregulated investment. The mass public protests against the WTO, the IMF/World Bank and the G8 were still to come – in Seattle, Prague, Genoa, Quebec City, Doha and elsewhere. But the East Asian crisis planted worrying seeds of doubt about the merits of corporate globalization.

Short-term speculative capital whizzes around the world leaving ravaged economies and human devastation in its wake. East Asia (Indonesia, South Korea, Thailand, Malaysia, the Philippines) suffered a destructive net reversal of private capital flows from 1996 to 1997 of $12 billion.

Percentage change in GDP before and after the Asian financial crisis

1 Kirkpatrick Sale, The Conquest of Paradise: Christopher Columbus and the Columban Legacy, Knopf, New York, 1990. 2 The Ecologist, Vol 29, No 3, May/June 1999. 3 ‘Modest trade growth anticipated for 2014 and 2015 following two year slump’, WTO press release, 14 April 2014. 4 David Korten, When Corporations Rule the World, Kumarian/Berrett-Koehler, West Hartford/San Francisco, 1995. 5 The World of Air Transport in 2013, Annual Report of the ICAO Council. 6 Global Market Forecast 2014 Freight, Airbus S.A.S. 7 Joseph Stiglitz, Globalization and its Discontents, WW Norton, New York/London, 2003. 8 Human Development Report 1999, United Nations Development Programme, New York/Oxford, 1999.