3 Debt and structural adjustment

Developing countries fight for a New International Economic Order, including fairer terms of trade, and push their case through UN agencies like UNCTAD and producer cartels like OPEC. Petrodollars flood Northern financial centers and US President Richard Nixon floats the dollar, sabotaging the Bretton Woods fixed exchange-rate system. When Third World debt expands, the IMF and World Bank step in to bail out debt-strapped nations. In return they must adopt ‘structural adjustment’ policies which favor cheap exports and spread poverty throughout the South.

The global economy has changed dramatically since 1980 – so much so that few of us today recall the campaign for a ‘new international economic order’ (NIEO) by African, Asian and Latin American nations just 10 years before that. Throughout the 1960s and early 1970s, an insistent demand for radical change burst forth from the two-thirds of the world’s people who lived outside the privileged circle of North America and western Europe. There was a strong movement to shake off the legacy of colonialism and to shape a new global system based on economic justice between nations. Some Third World states began to explore ways of increasing their bargaining power with the industrialized countries in Europe and North America by taking control of their natural resources. The Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) was formed in September 1960 by four Middle East oil producers (Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia) plus Venezuela. Their goal was to control the supply of petroleum and ratchet up the price of oil, thereby increasing their share of global wealth and bringing prosperity to their populations. The oil exporters’ success led to heady talk of ‘producer cartels’ to raise the price of other exports like tin, nickel, coffee, cocoa, cotton and natural rubber so that poor countries dependent on one or two primary commodities could gain more income and control over their own development. There was also strong opposition to the growing power of Western-based corporations that were seen to be remaking the world in their own interests, trampling on the rights of weaker nations. When poor countries tried to increase the price of their main exports, they often found themselves confronting the near-monopoly control by big corporations of processing, distribution and marketing.

In the wake of OPEC, the NIEO was strongly endorsed at the Summit of Non-Aligned Nations in Algiers in September 1973. Then, in April 1974, the Sixth Special Session of the UN adopted the Declaration and Program of Action of the New International Economic Order. The following December the General Assembly approved the Charter of Economic Rights and Duties of States.

Key NIEO demands included:

• ‘Indexing’ developing-country export prices to tie them to the rising prices of manufactured goods from the developed nations.

• Hiking official aid from the developed countries to 0.7 per cent of GNP (only Sweden, Norway, Luxembourg, Denmark and the Netherlands have consistently reached or exceeded this 0.7% target in the succeeding years).

• Lowering tariffs on exports from poor countries and managing volatile commodity markets.

• Regulating transnational corporations to ensure they comply with national laws.

• Greater stability in exchange rates and monitoring of cross-border capital flows.

Meanwhile, the Charter of Economic Rights and Duties of States endorsed:

• The sovereignty of each country over its natural resources and economic activities, including the right to nationalize foreign property.

• The right of countries dependent on a small range of primary exports to form producer cartels.

The declaration of NIEO principles was the culmination of a new ‘solidarity of the oppressed’ which had spread throughout the developing nations.

The ‘Third World’ seeks justice

Galvanized by centuries-old colonial injustices and sparked by the radical ideas of Frantz Fanon in Algeria, Kwame Nkrumah in Ghana, Mohandas Gandhi in India, Sukarno in Indonesia, Julius Nyerere in Tanzania and Fidel Castro in Cuba, these ‘Third World’ nations set out to collectively challenge the entrenched power of the United States and western Europe. The NIEO was not a grassroots movement. It was a collection of intellectuals and politicians who believed that free markets, left to themselves, would never reduce global inequalities – there needed to be a global redistribution of wealth. For the most part they did not reject the capitalist model. Instead these leaders argued for improved ‘terms of trade’ and a more just international economic system. When bargaining failed, producer countries began to form trade alliances based on specific commodities.

Third World nations also formed political organizations like the Non-Aligned Movement, which was initially an attempt to break out of the polarized East/West power struggle between the West and the Soviet Bloc. In the UN, developing countries formed the ‘Group of 77’, which was instrumental in creating the UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). Within UNCTAD, poor countries pushed for fairer ‘terms of trade’. Many newly independent countries in the South still relied heavily on the export of raw materials in the 1950s and 1960s. But there was a faltering effort and a stronger belief in the need to build local industrial capacities and to push for a new global economy based on justice and fairness. Why was it that the price of imports from the West – whether manufactured goods, spare parts or foodstuffs – seemed to creep ever upwards while the prices for agricultural exports and raw materials from the South remained the same – or even decreased? This patent injustice was one of the main concerns of the NIEO and the focus of its commodity program.

The plan was to intervene in the market, to regulate supplies and steady prices, to the benefit of both producers and consumers. The 10 core commodities were to be cocoa, coffee, tea, sugar, jute, cotton, rubber, ‘hard’ fibers (sisal and coir), copper and tin. This new commodity system was to be based on ‘international buffer stocks’ with a ‘common fund’ to purchase these stocks when prices dropped, as well as new multilateral trade commitments and improved ‘compensatory financing’ to stabilize export earnings. Unfortunately, the NIEO was never really given much of a chance by Western nations, which saw it as an erosion of their market advantage. They rejected out of hand the idea that rich countries had anything to do with the plight of developing countries. They denied that poor countries had shared interests and they refused to accept that these countries were sidelined by international institutions. Third World nations, meanwhile, were split by divergent interests, a desperate need for export earnings and their lack of political power.

The transparent injustice of this enraged and frustrated leaders like Tanzania’s charismatic Julius Nyerere, who referred to declining terms of trade as constantly ‘riding the downward escalator’. Between 1980 and 1991 alone, non-oil exporting developing countries lost nearly $290 billion due to decreasing prices for their commodity exports. In response to this economic discrimination, developing countries also began agitating for an increase in ‘untied’ aid from the West. (When aid was ‘tied’, poor countries were obliged to spend their aid dollars on goods and services from the donor nation; it was in fact a way of subsidizing domestic manufacturers.) Third World nations also called for more liberal terms on development loans and for a quicker transfer of new manufacturing technologies from North to South.

In addition, most developing countries favored an active government role in running the national economy. They quite rightly feared that in a world of vast economic inequality they could easily be crushed between self-interested Western governments and their muscular corporate partners. This was the chief reason that many Third World nations began to take tentative steps to regulate foreign investment and to introduce minimal trade restrictions.

This process began in Latin America, where formal political independence had been won in the 19th century, much earlier than in Asia and Africa. South American nations began to encourage ‘import substitution’ in the 1950s as a way of boosting local manufacturing, employment and income. Countries like Brazil and Argentina used a mix of taxation policy, tariffs and financial incentives to attract both foreign and domestic investment. US and European auto companies set up factories to take advantage of import barriers. The goal was to stimulate industrialization in order to produce goods locally and to boost export earnings. This had the added benefit of reducing imports, which both cut the need for scarce foreign exchange and kept domestic capital circulating inside the country. But the era of import substitution was short. Latin American nations were bullied into dismantling import barriers. Foreign-made goods, mostly American, soon flooded in again, undercutting domestic industries. By the late 1980s, there were few local producers of cars, TVs, fridges or other major household goods in Latin America. Production that remained was dominated by big foreign companies. Nonetheless, the attempt at import substitution was an important step in trying to shift the balance of global power to poor countries.

The origins of the debt crisis

Even before the clamor for a new international economic order, momentous changes were beginning to unfold that would dramatically alter the fate of poor nations for decades to come. By the late 1960s, the Bretton Woods dream of a stable monetary system – fixed exchange rates with the dollar as the only international currency – was collapsing under the strain of US trade and budgetary deficits.

As the US war in Vietnam escalated, the Federal Reserve in Washington pumped out millions of dollars to finance the conflict. The US economy was firing on all cylinders and beginning to overheat dangerously. Inflation edged upwards while foreign debt ballooned to pay for the war.

World Bank President Robert McNamara also leapt into the fray and contracted huge loans to the Global South during the 1970s – both for ‘development’ (defined as basic infrastructure to bring ‘backward’ economies into the market system) and to act as a bulwark against a perceived worldwide communist threat. The Bank’s stake in the South increased five-fold over the decade.

At the same time, a guarded optimism took hold in developing countries, fuelled by moderately high growth rates and a short-term boom in the price of commodities, particularly oil. OPEC was the first, and ultimately the most successful, Third World ‘producer union’. By controlling the supply of oil, it was able to triple the price of petroleum to over $30 a barrel. The result was windfall surpluses for OPEC members – $310 billion for the period 1972-77 alone. This ‘oil shock’ rippled through the global economy, triggering double-digit inflation and a massive currency ‘recycling’ problem.

What were OPEC nations to do with this vast new wealth of ‘petrodollars’? Some of the cash was spent on glittering new airports, power stations and other showcase mega-projects. But much of it eventually wound up as investment in Northern financial centers or deposited in Northern commercial banks. This enormous inflow of petrodollars led to the birth of the ‘eurocurrency’ market – a huge pool of money held outside the borders of the countries that originally issued the currency. The US dollar was the main ‘eurocurrency’ but there were also francs, guilders, marks and pounds.

Western banks, with all this new OPEC money on deposit, began to search for borrowers. They didn’t have to look for long. Soon millions in loans were contracted to non-oil-producing Third World governments desperate to pay escalating fuel bills and to fund ambitious development goals. At the same time the massive increase in oil prices triggered a surge in global inflation. Prices skyrocketed while growth slowed to a crawl and a new word was added to the lexicon of economists: ‘stagflation’.

In the midst of this economic chaos, US President Richard Nixon moved unilaterally to delink the dollar from gold. A key goal of Bretton Woods was to ‘ensure exchange-rate stability, prevent competitive devaluations, and promote economic growth’. The US dollar was to provide that stability by functioning as a global currency. (The US owned over half the world’s official gold reserves – 574 million ounces – at the end of World War Two.) International trade was to be settled in dollars which could be converted to gold at a fixed exchange rate of $35 an ounce. The US government agreed to back every overseas dollar with gold. Other currencies were fixed to the dollar and the dollar was pegged to gold.

Nixon’s radical move torpedoed Bretton Woods and moved the world to a system of floating exchange rates. Washington also devalued the US dollar against other major world currencies, jacked up interest rates to attract investment and imposed a 90-day wage-and-price freeze to fight inflation – all of which had an enormous impact on the global economy.

By slashing the value of the dollar, Washington effectively reduced the huge debt it owed to the rest of the world. The US had been running a sizeable deficit to pay the costs of the war in Vietnam. As interest rates shot up, those countries reeling under the effect of OPEC oil-price hikes had the cost of their eurodollar loans (most of which were denominated in US dollars) double or even triple almost overnight. The debt of the non-oil-producing Third World increased five-fold between 1973 and 1982, reaching a staggering $612 billion. The banks were desperate to lend to meet their interest obligations on deposits, so easy terms were the order of the day. Dictators who could exact payments from their cowering populations with relative ease must have seemed like a good bet for lenders looking for a secure return.

Sometimes the petrodollar loan money was squandered on grandiose and ill-considered projects. Sometimes it was simply filched – siphoned off by Third World elites into personal accounts in the same Northern banks that had made the original loans. Often it was both wasted and stolen.

Dictator kickbacks and ‘odious debt’

The experience was similar across the Global South. From the mid-1960s to the mid-1980s, despots were in power across Latin America and they employed an ingenious variety of scams. In Asia and Africa, too, autocrats with powerful friends and voracious appetites for personal wealth were financed willingly by the international banking fraternity. Indeed, it worked so well that the credit lines became almost limitless – particularly if the governments in question were on the ‘right’ side of the Cold War and buying large quantities of arms from Northern suppliers.

Examples of these foolish loans to corrupt leaders are well known. In the Philippines, the dictator Ferdinand Marcos with his wife, Imelda, and their cronies, pocketed in the form of kickbacks and commissions a third of all loans to that country. Before he was forced from office in 1986, Marcos’ personal wealth was estimated at $10 billion.

The Argentine military dictatorship, famous for its ‘dirty war’ against so-called subversives, borrowed $40 billion from 1976 to 1983 and left no records for 80 per cent of the debt. After the return to democracy Argentineans demanded that the government either produce accounts or declare the debt illegal. Evidence soon emerged that some US banks knew money was being misused, that there had been kickbacks plus fraudulent loans to companies linked to the military, and that the IMF allegedly connived at the fraud. The military also used some of the money to buy weapons for the Falklands/Malvinas War. Later, in the 1990s, following the IMF prescription, President Carlos Menem privatized public services and industries and pegged the Argentine peso to the US dollar. All for naught as it turned out – in 2001 the crushing debt burden led to a complete collapse of the Argentinean economy. Bank accounts were frozen. The country defaulted on nearly half its $180-billion repayment obligations the following year and there was tremendous popular pressure to resist taking on further foreign debt.

Analyst Joseph Hanlon cites the African country of Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo) as another flagrant example of loans made knowingly to ‘corrupt and nasty dictators’. In 1965, Joseph Mobutu, a staunch anti-communist, seized power in the Congo, which he renamed Zaire. The IMF country director, Irwin Blumenthal, also acted as head of Zaire’s central bank from 1978. Hanlon quotes a memo from Blumenthal in which the IMF employee writes that corruption was so serious that there was ‘no (repeat no) prospect for Zaire’s creditors to get their money back’. Despite this warning, the IMF funnelled $700 million to Mobutu over the next decade while the World Bank pumped in another $2 billion. Western governments also shoved cash at the dictator. Hanlon notes: ‘When Blumenthal wrote his report, Zaire’s debt was $4.6 billion. When Mobuto was overthrown and died in 1998, the debt was $12.9 billion.’1

From 1997 to 2000, the ‘Jubilee 2000’ citizens’ movement led a worldwide campaign to cancel the debts of the world’s poorest countries. The campaign attracted millions of supporters, North and South. Jubilee researchers found that almost a quarter of all Third World debt (then around $500 billion) was the result of loans used to prop up dictators in some 25 different countries – sometimes called ‘odious debt’. ‘Odious’, because citizens wondered why they should be obliged to repay loans contracted by corrupt rulers who used the money to line their own pockets.

Loans flowed free and fast through the 1970s and early 1980s. But eventually the soaring tower of debt began to crack and sway. One government after another began to run into trouble. The loans they had squandered on daft projects or salted away in private bank accounts became so large that foreign-exchange earnings and tax revenues couldn’t keep up with the payments.

Structural adjustment

During this period, the IMF became an enforcer of tough conditions on poor countries that were forced to apply for temporary balance-of-payments assistance. The loans were conditional on governments following the advice of Fund economists who had their own take on what Southern nations were doing wrong and how they could fix it. The demands were woven into the deals worked out with those countries that required an immediate transfusion of cash. Essentially, the IMF argued that the debtor country’s problems were caused by ‘excessive demand’ in the domestic economy. Curiously, the responsibility of the private banks that made most of the dubious loans in the first place (with their eyes wide open, it should be noted) was ignored.

According to the Fund, this excessive local demand meant there were too many imports and not enough exports. The proposed solution was to devalue the currency (making imports more expensive) and cut government spending. This was supposed to slow the economy and reduce domestic demand, gradually resulting in fewer imports, as well as more and cheaper exports. In time, the IMF argued, a little belt-tightening would eliminate the balance-of-payments deficit. Countries were forced to adopt these austerity measures if they wanted to get the IMF ‘seal of approval’. Without it, they would be ostracized to the fringes of the global economy. As early as the 1970s, both the IMF and the World Bank also urged debtor nations to take on deeper ‘structural adjustment’ measures. Initially, borrowing countries refused to go along with the advice.

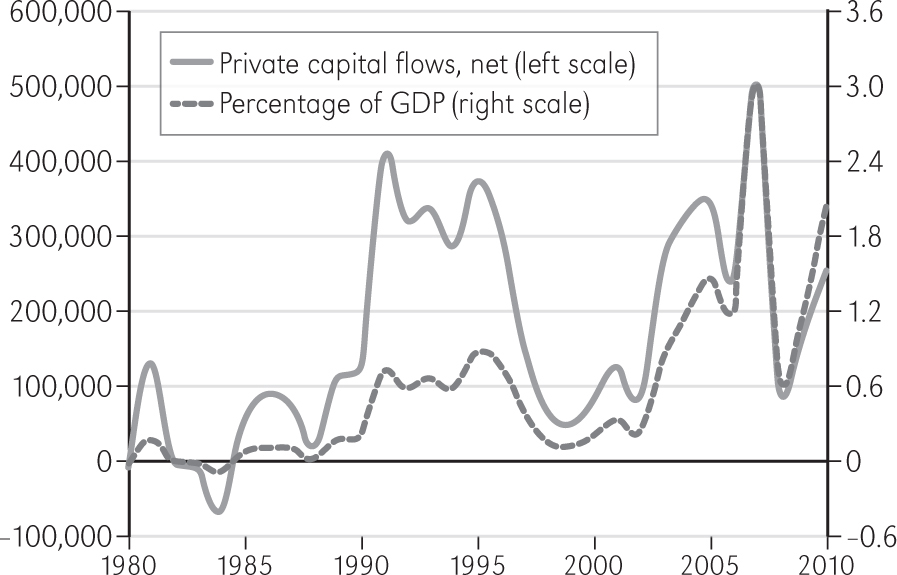

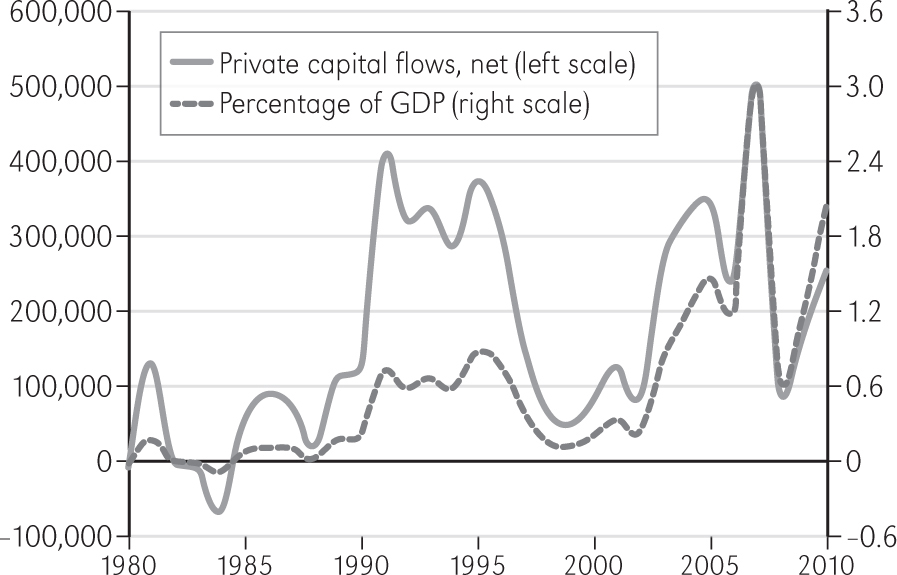

Most of the increase in debt in recent years has been to pay interest on existing loans rather than for productive investment or to tackle poverty. Developing countries have often paid out more in debt service (interest plus principle) than they receive in loans and new investment – a net transfer from North to South. After the crash of 2008, net private capital flows to developing countries plummeted. Ironically this reversal could be beneficial in the long run since private capital is often speculative and destabilizing. As financial globalization has spread rapidly in recent decades more and more developing countries have liberalized their financial systems.

Net private capital flows towards developing and transition economies, 1980-2010 ($ millions and as percentage of recipient countries’ GDP)

(Source: Development and Globalization, Facts and Figures 2012, UNCTAD.)

Then, in 1982, Mexico became the first indebted country to admit it could no longer meet its payments and a fully fledged Third World ‘debt crisis’ emerged. Northern politicians and bankers began to worry that the huge volume of unpayable loans would undermine the world financial system. Widespread panic began to spread as scores of Southern nations teetered on the brink of economic collapse. In response, both the Bank and the IMF hardened their line and demanded major changes in the way debtor nations ran their economies. Countries like Ghana were forced to impose tough adjustment conditions as early as 1983. A few years later, US Treasury Secretary James Baker decided to formalize this new strategy, forcing Third World economies to radically ‘restructure’ their economies to meet their debt obligations. The ‘Baker Plan’ was introduced at the 1985 meeting of the World Bank and the IMF when the US urged both agencies to impose more thorough ‘adjustments’ on debtor nations.

The Bank and the Fund made full use of this new leverage. Together they launched a policy to ‘structurally adjust’ the Third World by further deflating economies. They demanded a withdrawal of government funding from public enterprise but also from basic healthcare, welfare and education. Exports to earn foreign exchange were privileged over basic necessities, food production and other goods for domestic use.

The IMF set up its first ‘formal’ Structural Adjustment Facility in 1986. The World Bank, cajoled by its more doctrinaire sibling, soon followed – by 1989 the Bank had contracted adjustment loans to 75 per cent of the countries that already had similar IMF loans in place. The Bank’s conditions extended and reinforced the IMF prescription for financial ‘liberalization’ and open markets.

These new demands included:

• selling state-owned enterprises to the private sector;

• reducing the size and cost of government through public-sector layoffs;

• cutting basic social services as well as subsidies on essential foodstuffs;

• reducing barriers to trade.

This restructuring was highly lucrative for the financial sector. Private banks siphoned off more than $178 billion from the Global South between 1984 and 1990.2 Structural-adjustment programs (SAPs) were an extremely effective mechanism for transforming private debt into public debt.

Consequently, the 1980s were a ‘lost decade’ for much of the Third World – especially for Africa. Growth stagnated and debt doubled to almost $1,500 billion by the decade’s end. By 2002, it had reached nearly $2,500 billion. An ever-increasing proportion of this new debt was to service interest payments on the old debt, to keep money circulating and to keep the system running. Much of this debt had shifted from private banks to the IMF and the World Bank – though the majority was still owed to rich-world governments and Northern banks. The big difference was that the Fund and the Bank were always first in line, so paying them was a much more serious prospect.

The stark fact that the IMF and the Bank were taking more money out of the developing countries than they were putting in was a jolt for those who believed those institutions were there to help.

In six of the eight years from 1990 to 1997 developing countries paid out more in debt service (interest plus repayments) than they received in new loans: a total transfer from South to North of $77 billion. Most of the increase was to meet interest payments on existing debt rather than for new productive investment.3 In 1998, this negative flow reversed as a result of massive bailout packages to Mexico and Asia. Nonetheless, figures for all private and public loans received by developing countries between 1998 and 2002 show that Southern nations repaid $217 billion more than they received in new loans over the same period.4

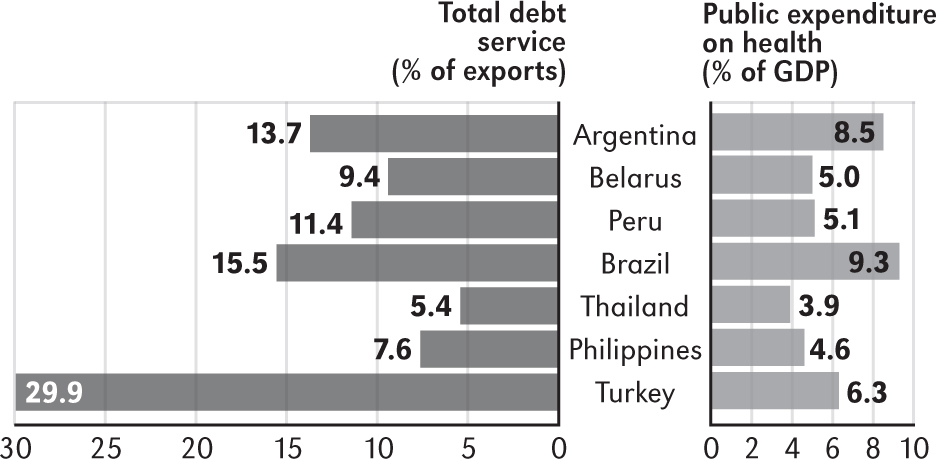

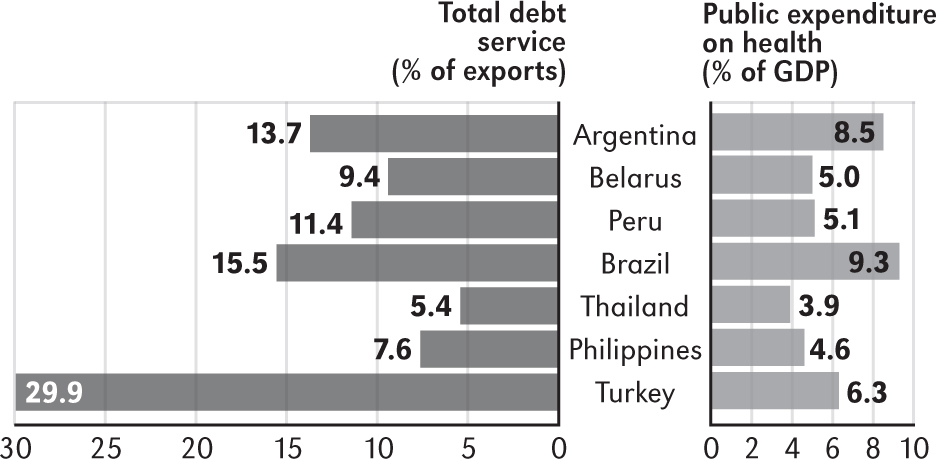

In return for new loans to poor countries, lenders in the 1980s and 1990s insisted on ‘structural adjustment’ to increase their chances of being paid back. This meant cutting government spending on things like healthcare and education – the very services on which poor people (and women and children in particular) rely. Many of these countries have ended up spending more on servicing their debts than on the basic needs of their citizens.

Government spending on foreign debt and social services (selected countries, 2012)

Source: World Bank

According to the Jubilee Debt Campaign (JDC) the total debt of the very poorest countries in 2007 (the ‘low income countries’ with an annual average income then of less than $935 per person) was $222 billion. That same year, those countries paid over $12.4 billion to the rich world in debt service – $34 million a day. For all ‘developing’ countries, total external debt in 2007 was $3,400 billion on which they paid $540 billion in debt service. There was some debt cancellation in 2008 and 2009, but there were also massive new debts in response to the global financial crisis.

Meanwhile, the ‘conditions’ imposed by structural adjustment diverted government revenues away from things like education and healthcare towards debt repayment and the promotion of exports. This gave the World Bank and IMF a degree of control over national sovereignty that the most despotic of colonial regimes rarely achieved.

Even former ‘economic shock-therapy’ enforcers like Columbia University’s Jeffrey Sachs were forced to reconsider their faith in this ‘neoliberal’ recipe for economic progress. In 1999, Sachs wrote that many of the world’s poorest people live in countries ‘whose governments have long since gone bankrupt under the weight of past credits from foreign governments, banks and agencies such as the World Bank and the IMF…Their debts should be cancelled outright and the IMF sent home.’5

The limited scope of debt relief

Despite Sachs’ warning, the situation has changed little. In nations as far apart as Rwanda, Egypt and Peru, the privations suffered in the name of debt repayments were hidden behind violent outbreaks of civil unrest. All attempts at debt relief for the South were rebuffed on principle until 1996, when the ‘Heavily Indebted Poor Countries Initiative’ (HIPC) was launched to make debt repayments ‘sustainable’. This was followed in 2005 by the IMF-led Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative (MDRI) which offered full debt relief to those countries that fulfilled their HIPC obligations. The MDRI applies only to debts contracted with the IMF, the International Development Association (the World Bank’s ‘soft loan’ window) and the African Development Fund. It doesn’t offer relief on debts incurred to other governments, to private creditors or to other multilateral institutions.

According to the World Bank, by 2014 the HIPC and MDRI programs had relieved 36 countries of $96 billion in debt since 1996, ‘freeing up their governments to spend money on poverty reduction’. Thirty-one of the beneficiary countries are in Africa.6 But the HIPC/MDRI package has a checkered history. HIPC was designed in the interest of the creditors to protect their interests, to avoid default and to keep the system running. The program cancels debt to a level it considers ‘sustainable’ – based on a country’s export earnings. But it doesn’t consider other needs or whether the debts were legitimate in the first place. Poor countries are hobbled but not broken: they continue to spend billions on debt repayments, often as much as 20 per cent of revenues. And as the Jubilee Debt group suggests, much of that debt is ‘unpayable’ – it’s simply impossible for countries to pay it off while also providing their people with health and education. Most HIPC candidates continue to spend more on debt service than on public health.7 Despite $130 billion in debt cancellation from 2000 to 2013 the Jubilee Debt Campaign warns that the root causes of the debt trap are still in place and that ‘history may be set to repeat itself’.

In October 2014 it noted: ‘Two-thirds of impoverished countries face large increases in the share of government income spent on debt payments over the next 10 years. On average, current lending levels will lead to increases of between 85 per cent and 250 per cent in the share of income spent on debt payments, depending on whether economies grow rapidly, or are impacted by economic shocks. Even if high growth rates are achieved, a quarter of impoverished countries would still see the share of government income spent on debt payments increase rapidly.’

The group cites the case of Ghana. The IMF and World Bank predict the West African nation’s debt payments will increase from 12 per cent of government income in 2014 to 25 per cent by 2023 even if the economy grows by 5.6 per cent a year. If economic growth is less, payments could devour half of government income. Shockingly, this has all occurred since Ghana’s debt was cancelled in 2004.8

Decades of structural adjustment failed to solve the debt crisis, caused untold suffering for millions of people and led to widening gaps between rich and poor. A 1999 study by the Washington-based group, Development Gap, looked at the impact of SAPs on more than 70 African and Asian countries during the early 1990s. The study concluded that the longer a country operates under structural adjustment, the worse its debt burden becomes. SAPs, Development Gap warned, ‘are likely to push countries into a tragic circle of debt, adjustment, a weakened domestic economy, heightened vulnerability and greater debt.’9

So we are left with a bizarre and troubling spectacle. In Africa, external debt more than quadrupled after the Bank and the IMF began managing national economies through structural adjustment. According to the UN, in 2004 Zambia had one of the highest rates of HIV/AIDS infection in the world, yet the southern African nation was spending three times as much on debt service as on healthcare. When the country finally completed the HIPC program in April 2005, $4 billion of debt was cancelled. Yet the IMF predicts Zambia’s debt payments will triple from $60 million in 2010 to $180 million in 2015.

In Angola, where the average person lives to 52 years of age and 1 in 10 babies dies before their first birthday, over twice as much was spent on debt payments as on healthcare from 2010 to 2014, according to World Bank figures. In the late 1990s, half of all primary-school-age children in Africa were not in school yet governments spent four times more on debt payments than they spent on health and education.

Meanwhile in Latin America, before the debt balloon, Ecuador spent 30 per cent of its revenue on education, 10 per cent on healthcare and 15 per cent servicing its debts. By 2005 the situation was reversed – the nation spent nearly half its income on debt service, 12 per cent on education and just 17 per cent on healthcare. And poverty had increased. When the government opted to channel oil money towards social spending, the IMF and World Bank balked. The Bank delayed and ultimately cancelled an already approved loan as a result of what it described as a ‘policy reversal’. In 2007 Ecuador’s $17-billion debt had swollen to 40 per cent of its GDP.

SAPs may not have put Third World countries back on a steady economic keel but they have certainly helped undermine democracy in those nations. Critics call it a new form of colonialism.

‘Southern debt,’ writes political scientist Susan George, ‘has relatively little to do with money and finance, and everything to do with the West’s continuing exercise of political and economic control. Just think of the advantages: no army, no costly colonial administration, rock-bottom prices for raw materials…It’s a dream system and Western powers won’t abandon it unless their own outraged citizens – or a far greater unity among debtor nations themselves – oblige them to so do.’10

Joseph Stiglitz, former World Bank Chief Economist, is candid about the record of bureaucrats in both the IMF and the World Bank who have eroded the ability of states to govern their own affairs. In an article written shortly after his resignation, Stiglitz said there are ‘real risks associated with delegating excessive power to international agencies…The institution can actually become an interest group itself, concerned with maintaining its position and advancing its power.’11

Years later, he continued his attack on the limitations of ‘market fundamentalism’ preached by the IMF and the World Bank. ‘The institutions are dominated not just by the wealthiest industrial countries but by the commercial and financial interests in those countries and the policies naturally reflect this…The institutions are not representative of the nations they serve.’12

Servicing the national debt has become a major concern in rich and poor countries alike. But especially so in the Global South, where there are far fewer dollars to spend: debt has become a major brake on development.

With the break-up of the Soviet Union and the surging global economy in the early 2000s the triumph of capitalism seemed complete. The great financial meltdown that began in late 2008 shattered that confidence. But memories are short. Deficit fetishism, otherwise known as ‘austerity’, continues to dominate domestic economic policy across the West, even as unemployment remains stubbornly high.

What is certain is that ‘structural adjustment’ is an integral part of the modern globalized economy. Indeed, SAPs have a perverse logic when seen through the lens of economic globalization that puts the economy ahead of people. This ‘market fundamentalism’ has its own basic credo: private corporations should be free to trade, invest and move capital around the globe with a minimum amount of government interference.

But there are fault lines emerging in this elite consensus. People in the Global South are resisting structural adjustment through violent opposition and grassroots organizing. Across Europe millions have protested harsh austerity measures imposed by the ‘troika’ – the European Commission, the International Monetary Fund and European Central Bank – in return for bailouts to debt-strapped national governments. Protest is simmering across the South, too, not least among the millions uprooted by World Bank mega-projects, particularly the building of huge hydroelectric dams.

Opposition to free trade is on the rise. And in Latin America, governments opposed to – or at least uncomfortable with – the ‘Washington Consensus’ have been elected in Nicaragua, El Salvador, Uruguay, Paraguay, Argentina, Brazil, Ecuador, Bolivia and Venezuela. The one-size-fits-all model of economic globalization is no longer accepted. Religious extremism and the politics of ethnic exclusion (from Palestine to Iraq to India) are turning political costs into military ones. And, as continuing protests against the World Trade Organization and the G8 prove, powerful and unaccountable institutions are coming under pressure from citizens’ groups, community activists, students, trade unionists and environmentalists. Many are calling for reform. Others are going much farther and demanding the outright abolition of these agencies and a complete restructuring of the global economic system.

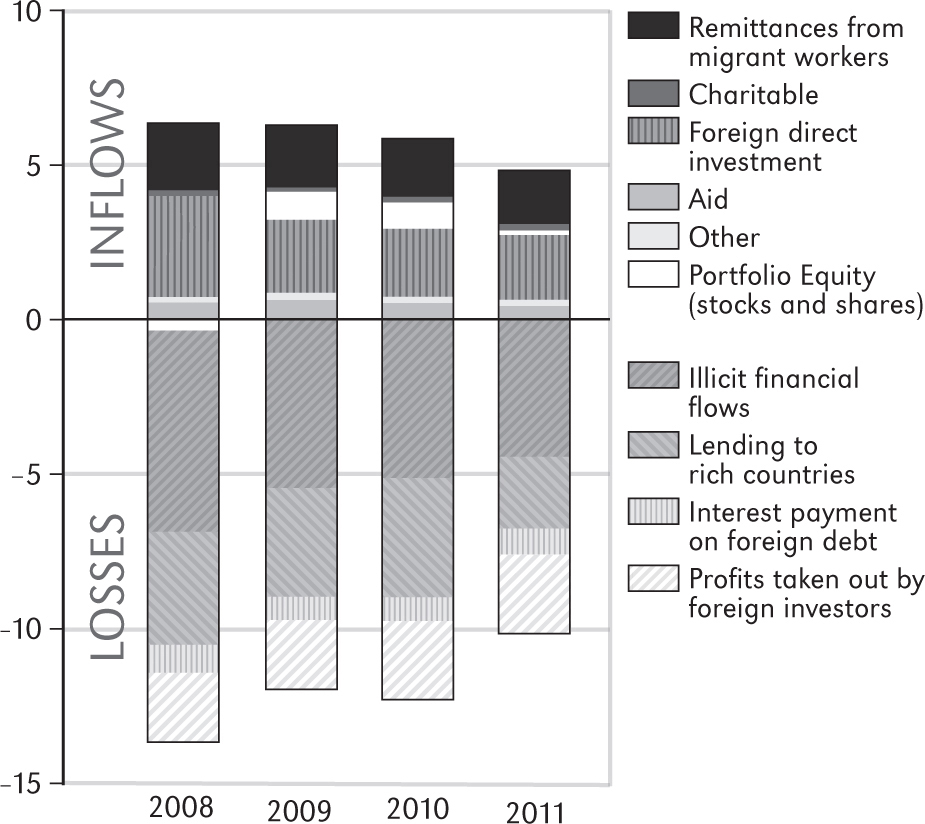

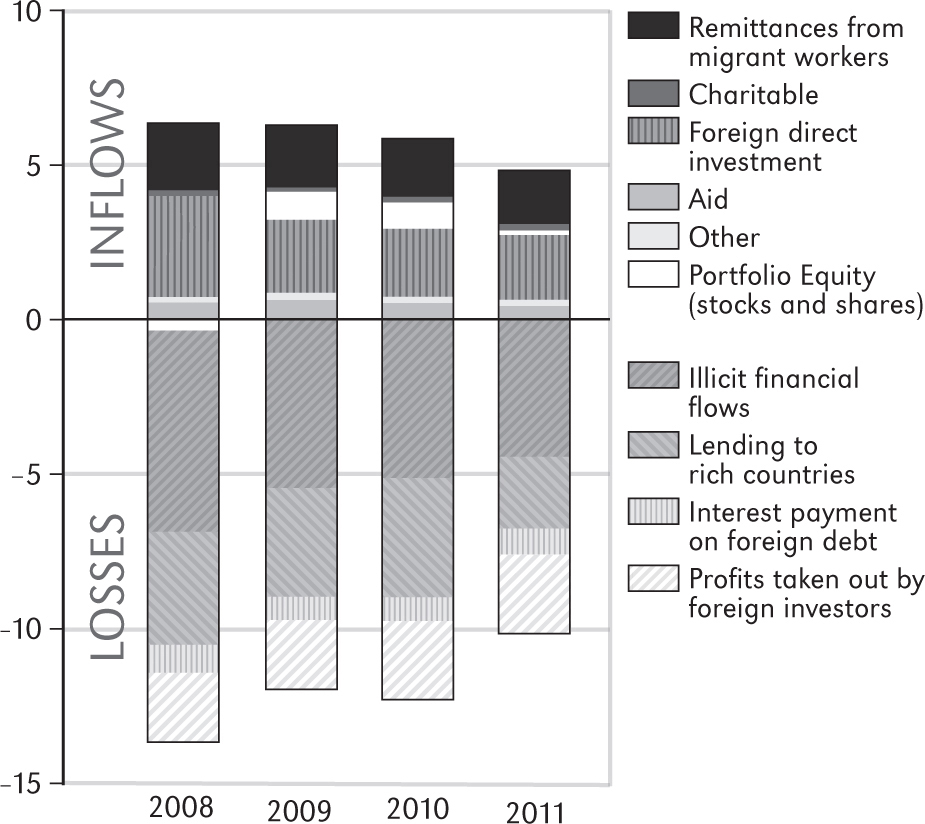

A 2014 study by the European Network on Debt and Development found that losses of financial resources by developing countries have been more than twice the amount of new loans and investment since the financial crisis of 2008. The graph shows that lost wealth has been close to 10% of GDP. The main causes are illicit financial flows, profits taken out by foreign investors and lending by developing countries to rich countries.

Inflows vs. losses for developing countries, % GDP (2008-11)

Source: eurodad

1 Joseph Hanlon, ‘Illegitimate Loans: lenders, not borrowers, are responsible’, Third World Quarterly, Vol 27, No 2, 2006. 2 ‘How Bretton Woods re-ordered the world’, New Internationalist, No 257, July 1994. 3 ‘Debt: the facts’, New Internationalist, No 312, May 1999. 4 Eric Toussaint, Your Money or Your Life, Haymarket, Chicago, 2005. 5 The Independent, London, 1 Feb 1999. 6 ‘The Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative’, IMF Factsheet, Sep 2014, nin.tl/IMFonMDRI 7 Human Development Report 2005, UNDP, New York, 2005. 8 ‘Lending boom threatens to create new debt crises’, Jubilee Debt Campaign, Oct 2014, jubileedebt.org.uk 9 ‘Conditioning debt relief on adjustment: creating conditions for more indebtedness’, Development Gap, Washington 1999. 10 Susan George, Another World Is Possible If…, Verso, London/New York, 2004. 11 Jim Lobe, ‘Finance: Stiglitz calls for more open debate, less conditionality,’ IPS, 30 Nov 1999. 12 Joseph Stiglitz, Globalization and its Discontents, Norton, New York/London, 2003.