4 The corporate century

Giant private companies have become the driving force behind economic globalization, wielding more power than many nation-states. Business values of ‘efficiency’ and ‘competition’ now dominate the debate on social policy, the public interest and the role of government. The tendency to monopoly, combined with decreasing rates of profit, drives corporate decision-making – with little regard for the social, environmental and economic consequences of those decisions.

The most jarring aspects of travel today are not the cultural differences – though thankfully those still exist – but the commercial similarities. Increasingly, where we travel to feels more and more like the place we just left.

Whether it’s Montreal or Mumbai, Beijing or Buenos Aires, globalization has introduced a level of commercial culture which is eerily homogeneous. The glitzy, air-conditioned shopping malls are interchangeable; the same shops sell the same goods. Fast-food restaurants like KFC, Subway, Pizza Hut and Dunkin Donuts are sprinkled around the globe. The emphasis is on high-sugar, high-fat foods – with minor concessions to local tastes. (McDonald’s, for example, features a ‘paneer salsa wrap’ in India, cottage cheese in spicy seasoning, wrapped in a chapati and fried.) KFC has more than 4,200 outlets in China alone.

Young people yearn for the same smartphones, drink the same soft drinks, smoke the same cigarettes, wear identical branded clothing, play the same computer games, watch the same Hollywood films and listen to the same Western pop music.

Welcome to the world of the transnational corporation, a cultural and economic tsunami that is roaring across the globe and replacing the spectacular diversity of human society with a Westernized version of the good life. As corporations market the consumer dream of wealth and glamor, local cultures around the world are marginalized and devalued. Family and community bonds are disintegrating as social relationships are ‘commodified’ and reduced to what the English social critic Thomas Carlyle called the ‘cash nexus’ in his 1839 essay, Chartism. In the words of Swedish sociologist Helena Norberg-Hodge, there is ‘a global monoculture which is now able to disrupt traditional cultures with a shocking speed and finality and which surpasses anything the world has witnessed before.’1

Over the past two decades, as global rules regulating the movement of goods and investment have been relaxed, private corporations have expanded their global reach so that their decisions now touch the lives of people in every corner of the world. The vast, earth-straddling companies dominate global trade in everything from computers and pharmaceuticals to insurance, banking and cinema. Their holdings are so numerous and so Byzantine that it is often impossible to trace the chain of ownership. Even so, it is estimated that a third of all trade in the international economy results from shuffling goods between branches of the same corporation.

Some proponents of globalization argue that transnationals are the ambassadors of democracy. They insist that free markets and political freedoms are inextricably bound together and that the introduction of the first will inevitably lead to the second. Unfortunately, the facts don’t support their claim. Market economies flourish in some of the world’s most autocratic and tyrannical states and transnational corporations have shown surprisingly little interest in, and have had even less effect on, changing political systems. The truth is that corporations follow the money – a nation’s political system is largely irrelevant. Saudi Arabia, Malaysia, Indonesia, Pakistan, China, Colombia: all have thriving market systems where big corporations are dominant actors. But none of them can be counted among the world’s healthy democracies.

As the US political scientist Benjamin Barber has written: ‘Capitalism requires consumers with access to markets and a stable political climate in order to succeed; such conditions may or may not be fostered by democracy, which can be disorderly and even anarchic in its early stages, and which often pursues public goods costly to or at odds with private market imperatives…capitalism does not need or entail democracy.’2

Many global corporations now wield more economic power than nation-states. According to 2010 figures from the World Bank and Forbes magazine, Wal-Mart took in more revenue than the GDP of South Africa and Greece while Costco’s revenue was more than the total GDP of Luxembourg. Exxon, General Electric, Bank of America and Berkshire Hathaway were all in the top 20 global corporations and all had higher revenues than Bangladesh.3

An earlier study by the Washington-based Institute for Policy Studies found:

• The world’s top 200 corporations accounted for 25 per cent of global economic activity but employed less than one per cent of its workforce.

• Combined sales of the top 200 corporations were 18 times more than the total annual income of 1.2 billion people living in absolute poverty – 24 per cent of the total world population.

• The profits of the top 200 corporations grew 362.4 per cent from 1983 to 1999 while the number of people they employed grew by just 14.4 per cent.4

Corporate merger mania

Of course large companies have not just appeared on the scene. They’ve been with us since the early days of European expansion, when governments routinely granted economic ‘adventurers’ such as the Hudson Bay Company and the East India Company the right to control vast swaths of the planet in an attempt to consolidate imperial rule. But there has been nothing in history to match the economic muscle and political clout of today’s giants – they grow larger and more powerful by the day. Scarcely a week goes by without another merger between major corporations. The competition for market share over the past two decades has been the catalyst for the biggest shift towards monopoly for a century.

Consolidation has been especially rapid in the telecommunications and media industries, where it is impossible to keep up with the endless shape-shifting. In January 2000, America Online (a distant memory now but then the world’s biggest internet provider) announced a $164-billion merger with Time-Warner. That’s still the biggest merger of all time but the jockeying amongst telecoms has not stopped. In 2013 Verizon bought Vodafone’s 45-per-cent stake in Verizon Wireless for a cool $130 billion, making it the third-largest corporate takeover of all time. That same year Warren Buffet’s Berkshire Hathaway holding company snapped up storied ketchup-maker, HJ Heinz, for a paltry $23 billion. In the world of big pharma, the US giant, Pfizer, bought Wyeth for $68 billion in 2009 while the German firm, Merck, engineered a $45-billion merger with Schering Plough, thus becoming the world’s second-largest drug company. Meanwhile, in the transport sector, American Airlines acquired US Airways for $11 billion, creating the world’s largest airline. A few years earlier, in 2006, both France and Luxembourg fought a losing battle against a $34-billion hostile takeover of Arcelor SA by India-based Mittal. The merger created the world’s largest steel company. In 2013 the company had revenues of $72 billion and it produces close to 100 million tons a year.

UN figures indicate that the tendency towards monopoly is growing across a range of industries, including manufacturing, banking and finance, media and entertainment, and communications. But high-profile business marriages are also taking place in older industries like automobiles and transport as well as in primary resources such as mining, forestry and agriculture. The 10 largest corporations in their field now control 86 per cent of the telecommunications sector, 85 per cent of the pesticides industry, 70 per cent of the computer industry and 35 per cent of the pharmaceutical industry. Between 2003 and 2005, the world’s top 10 seed companies increased their control of the world’s global seed trade from one-third to one-half.

Huge global corporations are becoming ever more powerful, eroding the regulatory powers of nation-states and riding roughshod over the rights of citizens to determine their own future. Of the top 100 economies, 37 belong to corporations rather than countries, with Wal-Mart the 28th-largest economy in the world.

GDP or total sales ($ billions)

The recent economic crash cooled corporate merger mania (in 2008 mergers fell by 30 per cent) but not for long. Deal-making has picked up as the global economy has slowly revived. According to Thomson Reuters, the global mergers and acquisitions market in 2013 involved 38,819 deals worth a combined $2,393 billion.5

Companies don’t do much horse trading when markets and the economy are heading south. So an uptick in mergers and acquisitions is a signal of investor confidence. Stock markets reward the merged corporations with higher share prices on the grounds that the new larger firms will be more ‘efficient’ and therefore increase company earnings. But what does that notion of ‘efficiency’ really mean? Mergers squander piles of money but they don’t usually produce better services or increase production. The public impact of this very private decision-making process is rarely considered. When corporate giants merge it inevitably leads to job losses and factory closures. From management’s perspective this is precisely the point – to bolster the bottom line by trimming costs.

When the Brazilian private equity firm, 3G Capital, and US-based Berkshire Hathaway acquired control of condiments maker, Heinz, in 2013 the writing was on the wall for the 105-year-old factory in Leamington, Ontario. Within months Heinz announced that the plant would be closed: 750 workers lost their jobs as production shifted to the US. The plant was the economic lifeblood of the small town. ‘It’s impersonal,’ the town’s deputy mayor, Charlie Wright, told the Toronto Star. ‘They’re looking at the bottom line all the time. They don’t look at the impact on people…But numbers have faces, and they have families, and they have schools to go to.’6 What might be good news for shareholders and money managers is a disaster for both the workers and the community.

Globalization has sparked a frenzy of corporate mergers and acquisitions (M&As). These mega-companies threaten competition and increase the threat of monopoly.

In 2013 more than $2.4 trillion was spent on cross-border M&As. The biggest deals were in telecommunications, energy and real estate.

Top Mergers & Acquisitions, 2013

Business executives champion the economic ‘common sense’ of mergers and push for them on the grounds that getting bigger is the only way to compete in a lean-and-mean global marketplace. Size does matter in the cut-throat world of free markets. But fewer companies also increase the tendency towards monopoly by eliminating competition. The easiest way to get rid of competitors is to buy them out. Giant companies also have more power to wring concessions from national and regional governments simply because they are such dominant economic players. All governments are keen to lure investors that promise jobs and growth.

Pushing privatization

The spate of mergers and acquisitions over the last decade reflects the quickly changing nature of the global economy, especially the loosening of foreign-investment regulations and the liberalization of international capital flows. Companies are now freer to compete globally, to grow and expand into overseas markets – and the recent shift to free trade in goods, services and investment capital is furthering this consolidation.

The assumption that competition is good ‘in and of itself’ is central to the corporate-led model of economic globalization. It’s this belief that has led to a worldwide campaign by the economically powerful in favor of privatizing publicly owned enterprises. According to this view, government must be downsized and its role in the provision of public services curtailed. The argument is that governments are inefficient bureaucracies that waste taxpayers’ money – so they must be restrained. It’s a very human trait to complain, so no wonder this criticism resonates with people of all political stripes. Perhaps that’s why, when conservative critics began to bemoan the costs of big government in the 1970s, it didn’t take them long to find a sympathetic ear. But instead of streamlining bureaucratic inefficiencies and making government work better, they argued that private business should do the job instead.

This enthusiasm for privatization exploded when Margaret Thatcher came to power in Britain in 1979. State-owned enterprises were auctioned off: the national airline, government-run water, gas, telephone and electric utilities, and the railway system. From 1979 to 1994 the overall number of jobs in the public sector in the UK was reduced from seven million to five million. However, there were few new jobs in the private sector to replace them. And the jobs that were created were in the non-unionized, low-paid, service sector. In the case of British Rail, the 1996 privatization created an inefficient, accident-prone system that depended on massive public subsidies and still had some of the highest rail fares in Europe. In 2014, 20 train lines in Britain were owned or operated by foreign state-owned or state-controlled companies. For a one-off payment to the public purse, the UK government had sold state-owned enterprises that had contributed guaranteed yearly profits to the Treasury.

While much was made of the opportunity for ordinary British people to buy shares in these newly privatized public utilities, the reality was quite different. Nine million UK residents did buy shares but most of them invested less than £1,000 and sold them quickly when they found they could turn a quick profit.

The majority of shares of the former publicly owned companies are now controlled by institutional investors and wealthy individuals. Campaigning journalist Susan George has called privatization ‘the alienation and surrender of the product of decades of work by thousands of people to a tiny minority of large investors’.7

As governments adopt the private-enterprise model and cut public expenditure, they open areas to market forces that were previously considered the responsibility of the state. After World War Two, in the light of growing socialist sympathies, politicians in the West were convinced by a civic-minded electorate to expand the welfare state, including education, healthcare, unemployment insurance, pensions and other social-security measures. At the same time the state expanded its investment in public infrastructure, building roads, bridges, dams, airports, prisons and hospitals.

Now, with the notion of an ‘inefficient’ public sector firmly fixed in people’s minds, governments are selling off public utilities like water, electricity, airports, even postal services – often because operating budgets have been slashed to ribbons. Even prisons and parks are being privatized as governments pare public expenditure to meet market demands for balanced budgets. All of this has an impact on the public sphere and inevitably contributes to the erosion of shared community. Make no mistake about it, these areas offer tremendous scope for private profits. In the US the total state budget for prisons and jails in 2012 was more than $53 billion.8

The new market in public healthcare

Other areas are also being eyed avidly by the private sector. Take state-funded healthcare. In Canada, Australia and Europe, private companies are making major inroads into publicly financed healthcare as deficit-conscious politicians slash budgets. This systematic de-funding shows no sign of slowing down as governments seek to reduce public debt in the midst of a weak economy. In the US, where the Obama administration eventually passed a watered-down Affordable Care Act, private insurance companies still hold sway. They have the power to raise premiums to increase profits and have more influence on decision-making than doctors or patients.

At the international level, the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS), administered by the World Trade Organization (WTO), was created in 1994. One of the goals of the GATS is to classify public health as a ‘service industry’, eventually opening the door to full-scale commercialization.

The for-profit health sector in the US has been actively lobbying to pave the way for overseas expansion. A document by the US Coalition of Services Industries in November 1999 suggested that Washington push the WTO to ‘encourage more privatization’ and to provide ‘market access and national treatment, allowing provision of all healthcare services cross-border’. The ultimate goal was clearly spelled out: to allow ‘majority foreign ownership of healthcare facilities’. The logic of the market is already intruding into the debate around healthcare policy. But the great fear for defenders of state-funded healthcare in Europe, Canada and elsewhere is that privatization will lead to a two-tier system. Wealthy patients jump the queue and receive state-of-the-art care while the rest of us make do with poorly equipped, underfunded hospitals, long waiting lists and overworked doctors, nurses and technicians.

Privatization has been strongly endorsed by both the World Bank and the IMF and is a standard ingredient in any ‘structural adjustment’ prescription. It is based on the notion that governments have no business in the marketplace and that the least government is the best government. Despite strong criticism of its policies, the Bank remains wedded to privatization.

Its Private Sector Development Strategy, released in February 2002, reinforces what the Bank calls ‘policy-based lending to promote privatization’. The initiative seeks to expand the Bank’s business-friendly division, the International Finance Corporation (IFC), whose role is to open doors for private companies, both foreign and domestic. The emphasis is on increasing the role of private business in the service sector: water, sanitation, electricity, education and healthcare.

Take the case of water. Since the 1980s the World Bank has been the biggest backer of water privatization in the developing world, with the IFC as its main channel for loans and financing. Yet its own data shows a 34-per-cent failure rate for private water and sewerage contracts between 2000 and 2010.9

How much room do poor nations have to reject or shape adjustment policies which are presented to them by the Bank or the IMF as conditions of borrowing? The answer is: virtually none. The Bank and the IMF have been enforcing market fundamentalism for decades. Often privatization is a ‘condition’ for release of aid funds. They jointly launched the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries Initiative (HIPC) in 1996. To qualify for debt relief under the program Southern nations must fall into line. According to an Oxfam UK report, debt relief to Honduras under the HIPC was delayed for six months when the IMF demanded more progress on electricity privatization.10 As a result of this pressure, the ability of governments to make sovereign policy decisions on behalf of their citizens is compromised.

Largely due to this arm-twisting, state assets have been auctioned off across the developing world and the former Soviet Union. In Russia, the transition to private ownership was riddled with corruption. Former Communist Party apparatchiks wound up in control of most state assets while billions hemorrhaged out of the country into numbered Swiss bank accounts. According to historian and investigative journalist Paul Klebnikov, the country suffered its worst economic decline since the Nazi invasion of 1942: ‘There was a 42-per-cent decline in GDP. The population was impoverished. Mortality rates rocketed and the Russian state was essentially bankrupt.’11 Klebnikov put the blame for this ‘shock therapy’ squarely on Western institutions. In 2002, he told Multinational Monitor: ‘Governments such as the American government at the time, august Western universities such as Harvard, and international financial institutions like the IMF, bear significant responsibility and must answer for their complicity in creating this whole catastrophe.’12 The oligarchs who profited from Russia’s privatization plan were not amused. Klebnikov was murdered in Moscow in 2004.

Across the Global South, privatization has been bedeviled by corruption, regulatory failure and corporate bullying. In the energy sector, for example, companies are often reluctant to invest in power projects without a guaranteed return. Enter the ‘power-purchase agreement’ – a legal sleight of hand which requires a publicly owned electricity distributor to buy power from private producers at a fixed price in US dollars for up to 30 years – even if demand swoons and the power is not used. In India, the Maharashtra State Electricity Board (MSEB) was fleeced by the now-disgraced corporation Enron and its $920-million Dabhol power plant. At one point, after renegotiating the power-purchase deal, the MSEB was obliged to pay Enron $30 billion a year. Indian critics called the deal ‘the most massive fraud in the country’s history’. Indian novelist and activist Arundhati Roy says that the MSEB was forced to cut production from its own plants to buy power from Dabhol and hundreds of small industries had to close because they couldn’t afford the expensive power. ‘Privatization,’ Roy writes, ‘is presented as being the only alternative to an inefficient, corrupt state. In fact, it’s not a choice at all…[it’s a] mutually profitable business contract between the private company (preferably foreign) and the ruling elite.’13

The problem with foreign direct investment

In addition to selling off public assets, governments are desperate to attract private investment. But investment by foreign corporations is by no means a guarantee of economic progress.

A large chunk of foreign direct investment (FDI) is used to buy out state firms, purchase equity in local companies or finance mergers and acquisitions. Cross-border mergers and acquisitions account for about 80 per cent of total foreign direct investment yearly. Little of this ends up in new productive activity and there is almost always a net loss of jobs as a result of downsizing after mergers are completed. Increased investment from abroad can also cause a net drain on foreign exchange as transnational companies remit profits to their overseas headquarters. If a foreign corporation produces mainly for local markets, and especially if it edges out local suppliers rather than replacing imports, it may actually worsen balance-of-payments problems.

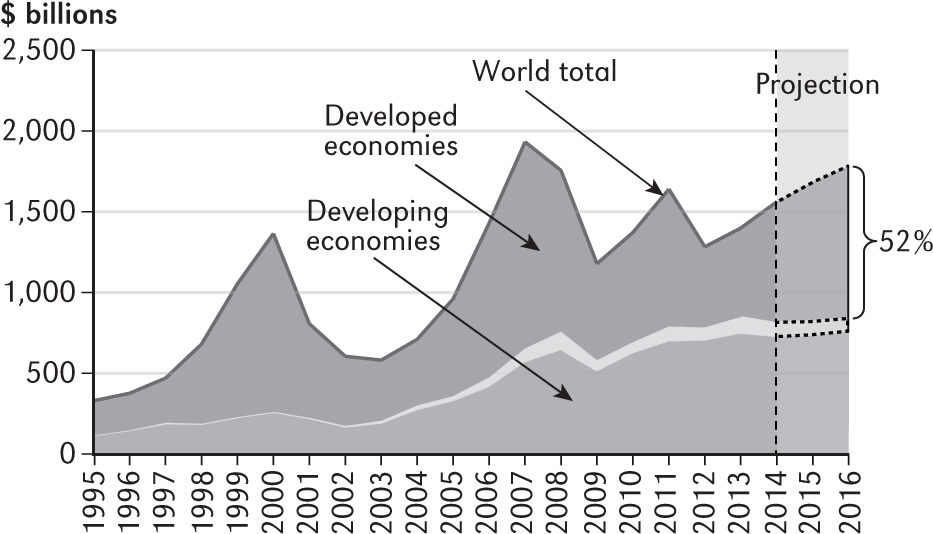

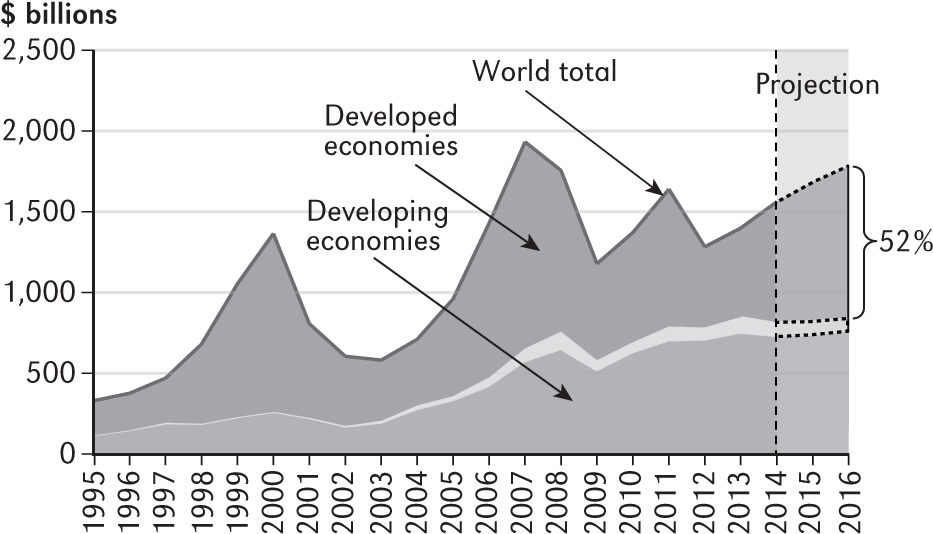

The rise and rise of foreign direct investment FDI)

FDI inflows, global and by group of economies, 1995–2013 and projections, 2014-2016

It’s not ‘how much’ but ‘what kind’ of FDI that matters. National governments need to select foreign investment that will produce net benefits for their citizens and reject those investments whose overall impact will be negative. Foreign investment can make a positive contribution to national development – but only if it is channelled into productive rather than speculative activities. Unfortunately, the ability to shape foreign investment is dwindling as free-trade arrangements and bilateral trade agreements effectively tie the hands of states which agree to them, inevitably compromising government sovereignty.

Nonetheless, most Southern governments are anxious to attract investment from global corporations – despite the concern about corporate power and unethical behavior. After all, transnational companies are extremely skilled at delivering the goods. They are at the cutting edge of technological innovation and they can introduce new management and marketing strategies. And it’s generally the case that wages and working conditions are better in foreign subsidiaries than in local companies.

But overseas investors don’t automatically favor countries simply because they’ve loosened regulations on profit remittances or corporate taxes. The big money predictably goes where it’s safest and where the potential for profit is greatest. Most direct investment is concentrated in a small number of developing countries. According to UNCTAD’s World Investment Report 2013 the bulk of investment in the Global South went to a handful of countries – Brazil, Mexico, India, Indonesia and especially China.14

Transnationals are also major players in research and development (R&D). They account for close to half of global R&D expenditure, eclipsing many governments. The world’s largest R&D spenders are concentrated in a few industries – information technology hardware, the automotive industry, pharmaceuticals and biotechnology.

Investors crave stability, which is why nearly 60 per cent of all foreign investment goes to industrial countries. The US, Britain, Australia, Ireland, France, Canada and Spain receive the lion’s share. Yet even in the West corporations have the upper hand, trading off one nation against another to see which can offer the most lucrative investment incentives. Governments drain the public purse in their attempts to buy jobs from private investors. Tax holidays, interest-free loans, research grants, training schemes, unhindered profit remittances and publicly funded sewers, roads and utilities are among the mix of ‘incentives’ that companies now expect in return for opening up a new factory or office.

The largest transnationals call themselves ‘global firms’, which might lead one to believe that they are stateless, disembodied entities toiling for the good of humankind. The truth is more complex. There are few giant companies that are truly stateless; most are firmly tied to one national home base. Bill Gates’ Microsoft is identifiably American. Total is French, Siemens is German, Vodafone is British and the giant aerospace conglomerate Embraer is Brazilian. But nationality is disposable when profits entice. Companies may wrap themselves in the national flag when lobbying local governments for tax breaks, start-up grants or other goodies. But their allegiances are fickle – and quickly diverted if opportunities for profit appear greater elsewhere. The fact that transnational corporations are relatively footloose means they can move to where costs are cheapest – and play off one government against another in the process. Examples fill the business press daily. Bombardier, a Canadian company that had received millions in government subsidies, announced in 2005 that it was exporting 500 highly paid, skilled jobs to India, China and Mexico, claiming that it needed to ‘return to profitability by reducing operating costs’.15 Companies also look to escape taxes whenever possible. In September 2014 the Obama administration moved to close a loophole on ‘tax inversion’. This legal dodge allowed companies to buy a foreign rival then relocate the head office outside the US to take advantage of lower taxes. Washington’s move came as fast-food giant Burger King was attempting to ‘invert’ to Toronto in a deal with the iconic Canadian coffee-and-donuts chain, Tim Hortons.

This political power – to pull up stakes, lay off workers, move management and shift production – is a powerful bargaining chip that business can use to squeeze greater concessions from job-hungry governments.

One of the corporate sector’s greatest political victories in recent decades has been to beat down corporate taxes. In Britain, the corporate tax rate fell from 52 per cent in 1979 to 30 per cent in 2000 and Prime Minister Tony Blair boasted that British business was subject to fewer strictures than corporations in the US. By 2014, the UK corporation tax rate had plunged still further to just 21 per cent, way below the US rate of 40 per cent and the French rate of 33 per cent and the Canadian rate of 26.5 per cent.16

Corporate tax rates have declined in virtually every OECD country over the last two decades as governments rely more and more on personal income taxes and sales taxes for revenues. (Between 2000 and 2011, debt-strapped Greece pared its rate from 40 per cent to 20 per cent.) In 1950 corporate taxes in the US accounted for 30 per cent of government funds; today they account for less than 12 per cent. In Canada, the effective federal corporate tax rate was cut from 28 per cent in 2000 to 15 per cent in 2012. Meanwhile, corporate income taxes accounted for just 7.85 per cent of government revenues, down from an average 11 per cent in the 1960s and 1970s. The main point is that corporations play one country against another to reduce taxes and increase profits. But they also employ scores of tax lawyers and accountants to ensure they pay as little as possible.

Their sheer size, wealth and power mean that transnationals and the business sector in general have been able to structure the public debate on social issues and the role of government in a way that benefits their own interests. They have used their louder voices and political clout to build an effective propaganda machine and to boost what the Italian political theorist Antonio Gramsci called their ‘cultural hegemony’. Through sophisticated public relations, media manipulation and friends in high places, the orthodoxy of corporate-led globalization has become the ‘common sense’ approach to running a country. This radical paradigm shift has occurred in the short space of 40 years – an extraordinary accomplishment by a cadre of rightwing thinktanks, radical entrepreneurs and their academic supporters.

The more our lives become entangled in the market, the more the ideology of profit before people becomes accepted. A corporation’s ultimate responsibility is not to society but to its shareholders, as Chief Executive Officers (CEOs) constantly reassure their investors at annual general meetings. Enhanced value for shareholders drives corporate decision-making – without regard for the social, environmental and economic consequences of those decisions. The public is the loser. Unless social obligations are imposed on companies, the business agenda will continue to ride roughshod over national and community interests. Capitalism and the public good are not necessarily congruent.

Impacts of NAFTA

The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) was one of the first regional economic pacts developed to further corporate globalization. The Washington-based non-governmental organization, Public Citizen, has documented a steady movement of US companies to cheap labor zones in Mexico and the direct loss of hundreds of thousands of jobs since NAFTA came into effect in 1995.

The activist group cites the example of the jeans maker Guess? Inc which, according to the Wall Street Journal, cut the percentage of its clothes sewn in Los Angeles from 97 per cent prior to NAFTA to 35 per cent two years later. In that period the company relocated five sewing factories to Mexico and others to Peru and Chile. More than 1,000 workers in Los Angeles lost their jobs. According to the Washington-based Economic Policy Institute, the deal eliminated nearly 880,000 jobs, most in high-paying manufacturing, while the ones that replaced them were low-paid, non-unionized service jobs. NAFTA also had a negative effect on the wages of US workers whose jobs were not relocated. They are now in direct competition with skilled, educated Mexican workers who work for a dollar or two an hour – or less. As a result their bargaining power with employers has been substantially eroded. NAFTA was supposed to solve this problem by raising Mexican living standards and wages. Sadly, that has not happened. Instead, workers on both sides of the Rio Grande have suffered.

NAFTA’s labor side-agreement was supposed to cushion workers but it didn’t work out that way. Instead, labor protections built into Mexico’s legal system have been attacked as obstacles to investment. In 2002, Mexican President Vicente Fox announced he would support the World Bank’s recommendations to scrap most of Mexico’s Federal Labor Law – eliminating mandatory severance pay and the 40-hour week. Mexico’s historic (though not always enforced) ban on strike-breaking and guarantees of healthcare and housing would be gutted as well.

The policy of encouraging foreign investment at all cost has also led to the wholesale privatization of Mexican industry and the effects have been devastating. While three-quarters of the workforce belonged to unions three decades ago, less than 30 per cent does today. Private owners reduced the membership of the railway workers’ union from 90,000 to 36,000.

Since 1994, half a million Mexicans have left their country every year. The recent world crisis has led to more displacement. The economy shrank by more than 10 per cent and 700,000 jobs were lost from October 2008 to May 2009. In response, President Felipe Calderón prescribed a two-per-cent tax on food and medicine, together with sharp hikes in the price of electricity, gas and water.

During the last two decades, the income of Mexican workers has lost 76 per cent of its purchasing power. Under pressure from foreign lenders, the government ended subsidies on the prices of basic necessities – including gasoline, electricity, bus fares, tortillas and milk – all of which have risen drastically. In 2012, an estimated 54 million people lived in poverty and 12 million in extreme poverty. Before the crash of 2007-8, the country’s independent union federation, the National Union of Workers, claimed that more than nine million people were out of work – a quarter of the workforce.

Well before NAFTA, the disparity between US and Mexican wages was growing. Mexican salaries were a third of those in the US in the 1970s. They are now less than an eighth. It is this disparity which both impoverishes Mexican workers and acts as a magnet drawing production from the US. By exacerbating these trends, NAFTA forced working communities in Canada, the US and Mexico to ask some basic questions.17

As corporations gain the upper hand, fear of job losses and the resulting social devastation have created a downward pressure on environmental standards and social programs – what critics of corporate power call ‘a race to the bottom’.

NAFTA is one of more than 3,000 trade and investment treaties around the world. Almost all of these carry provisions that empower corporations while restricting national governments from interfering with the ‘wisdom’ of the market. Business is constantly pushing to expand the freedom to trade and invest, unhindered by either government regulations or social obligations.

The fights against the MAI and TTIP

The Multilateral Agreement on Investment (MAI) was one infamous example of the attempt by big business to remake the world in its image.

The public has been wary of the WTO for some time. But the MAI flew under the radar until activists stumbled across it in 1997. After the WTO was created in 1994, the globe’s major corporations began to put together a plan for codifying the rules of world trade in a way that would give them the upper hand. They found it in the MAI. The agreement was drafted by the International Chamber of Commerce (a ‘professional association’ of the world’s largest companies) and presented to the rich-nation OECD members for discussion and, it was assumed, rubber-stamp approval.

Majority World governments were suspicious of the MAI; many saw it as ‘a throwback to colonial-era economics’. But, with the weight of the OECD behind it, supporters reckoned it would be speedily adopted as an official WTO document.

Delegates from OECD countries began discussing the MAI in early 1995 behind closed doors. By early 1997 most of the treaty was on paper and the public was none the wiser. In fact, most politicians in the OECD’s 29 member countries weren’t even aware of the negotiations. When activists in Canada got their hands on a copy of the MAI and began sending it around the world via the internet, the full scope of the document became clear.

Essentially the proposed agreement set out to give private companies the same legal status as nation-states in all countries that signed on. But, more importantly, it also laid out a clear set of rules so corporations would be able to defend their new rights against the objections of sovereign governments. The MAI was so overwhelmingly biased towards the interests of transnational companies that critics were quick to label it ‘the corporate rule treaty’.

For example, under MAI provisions corporations could sue governments for passing laws that might reduce their potential profits. They could make their case in secret with no outside interest groups involved and the decision would be binding. The MAI also allowed foreign investors to challenge public funding of social programs as a distortion of free markets and the ‘level playing field’. If a government chose to privatize a state-owned industry, it could no longer give preference to domestic buyers. In addition, governments would be forbidden to demand that foreign investment benefit local communities or the national economy. They could not demand domestic content, local hiring, affirmative action, technology transfer or anything else in return for allowing foreign companies to exploit publicly owned resources. And there were to be no limits on profit repatriation.

Once the text became public, citizens’ groups around the world began vigorous education campaigns on the damaging impact of the MAI. Two influential activists, Tony Clarke and Maude Barlow, summed up the feelings of citizens’ groups everywhere. ‘The MAI’, they wrote, ‘would provide foreign investors with new and substantive rights with which they could challenge government programs, policies and laws all over the world.’18

In a few months, public anxiety about the deal came to a head. In France, Australia, Canada and the US, politicians at all levels were drawn into the debate and governments were forced to enter ‘reservations’ to protect themselves from certain of the MAI’s provisions. By the May 1998 deadline it was clear that the talks were at a standstill and that public opposition had torpedoed further progress on the Agreement.

This was a clear victory for a growing international citizens’ movement. But the end of the MAI did not spell the end of the corporate agenda for a global investment treaty. The focus would now shift to both regional and country-to-country trade agreements where corporations could lobby for the MAI-like investment provisions.

Since then we’ve seen major new initiatives like the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) between the US and the EU, the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) deal between Canada and the EU, and the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) negotiations involving 12 nations strung along the Pacific Rim. These deals all bow to investor rights by including a clause to resolve what are called ‘investor-state dispute settlements’ (ISDS). NAFTA has a similar provision and the MAI was to include an ISDS mechanism too. This point is to allow corporations to sue governments if they stand in the way of open investment. In other words, business knows best and politics must not be allowed to get in the way.

In an open letter to UNCTAD, more than 250 non-governmental organizations wrote: ‘Through the dispute process, states’ regulatory efforts in the areas of health, environment and climate change, financial stability, water, labor rights and agriculture, among other areas, have been challenged, with billions of dollars of taxpayer money already awarded to corporations, and with many billions more still pending.’ The consequences are clear enough. Researcher Scott Sinclair points out that, as a result of similar ISDS provisions in NAFTA, ‘Canada has already paid out more than $170 million in damages and is facing billions of dollars in current claims related to resource management, energy and pharmaceutical patents’.19

The downward pressure on wages and social programs caused by economic globalization is compounded by the rise of free trade zones (FTZs), which now exist in more than 135 countries – there are more than 3,000 FTZs around the globe – from Malaysia and the Philippines to El Salvador, Mexico and even socialist Cuba. These officially sanctioned sites exist almost as separate countries, offering their corporate clients minimal taxes, lax environmental regulations, cheap labor and low overheads.

The dangers of overproduction

In their urgent need to grow, corporations have ignored a fundamental aspect of capitalist production: over-capacity. It was Henry Ford, one of the pioneers of mass production, who realized 80 years ago the inherent dilemma of replacing labor with machines and then paying the remaining workers poverty-level wages. You could produce a lot of cars but in the end you would have no-one who could afford to buy them: too many goods and too few buyers. Today, sophisticated improvements in manufacturing equipment have boosted productivity while destroying millions of jobs and curbing wage growth. Henry Ford’s own automobile sector is a case in point. One major reason for the massive restructuring in that industry over the past decade is over-capacity, estimated at more than 30 per cent worldwide. According to The Economist, the global auto industry can produce 20 million more vehicles a year than the market can absorb. Production is shifting to low-wage countries like Mexico, which was the world’s eighth-largest carmaker in 2014. Companies like Ford and Nissan have pledged to invest billions there in the future. China is still the world’s largest car maker, with a quarter of global production – followed by the US, Japan, Germany and South Korea. But this may change. The average manufacturing wage in China at $3.50 per hour is now higher than the $2.70 per hour in Mexico. (Car workers in North America make between $25 and $30 an hour.)

There is a global over-capacity in everything from shoes and steel to clothing and electronic goods. One estimate puts the excess manufacturing capacity in China alone at more than 40 per cent. As industries consolidate to cut losses, factories are closed but output remains the same or even increases. This produces falling rates of profit, which in turn drives industry to look for further efficiencies. One tack is to continue to cut labor costs – which helps the bottom line initially but actually dampens global demand over time. Another is the merger-and-acquisition route – cut costs by consolidating production, closing factories and laying off workers. However, this too is self-defeating in the long run since it also inevitably reduces demand.

The real danger of this overproduction is ‘deflation’. Instead of a steady rise in employment and relatively stable prices for commodities and manufactured goods, deflation is a downward spiral of both prices and wages. In economic terms, the formula is simple: capacity exceeds demand, prices fall, unemployment rises and wages are forced down farther.

In the 1930s, the result was a resounding and destructive economic crash which saw plants close and millions of workers made redundant. This catastrophe was reversed only when factories boosted production of armaments and other supplies for the Second World War. So far deflation has been kept at bay in the 21st century by making the US economy the ‘consumer of last resort’. According to the IMF, the US has provided about half the growth in total world demand since 1988. The US may still be recovering from the 2008 recession but the dollar is still vastly overvalued and its economy continues to suck in cheap imports from the rest of the world. Every day, Americans borrow $3 billion from foreigners – a form of ‘vendor financing’ – to pay for imports and to keep domestic interest rates low. The result is colossal domestic debt and record trade deficits. In 2013, the US trade deficit was $472 billion, down from $700 billion in 2007 but still nearly three per cent of GDP. China’s trade surplus with the United States increased from $11 billion in 1990 to a whopping $298 billion in 2012 – the country’s largest bilateral deficit.

In an era of globalized free markets, all countries try to fight their way to prosperity by boosting exports. That’s partly because traditional Keynesian methods of stimulating domestic growth by ‘priming the pump’ had fallen into disfavor prior to the collapse of the global economy in 2008. And few countries have either the inclination or the political will to direct domestic savings toward investment in the local market. Instead, all nations look outwards; international trade is seen as the ticket to economic growth. The financial meltdown saw a dramatic turnaround in world trade. Manufactured exports worldwide fell by half or more from late 2007 to mid-2009, the first time world trade had contracted since 1945. A few years earlier, in 2004, according to the WTO, the value of world merchandise trade rose by 21 per cent to $8.88 trillion while trade in services jumped by 16 per cent to $2.10 trillion. Yet, as UNDP’s 2005 Human Development Report pointed out: ‘After more than two decades of rapid trade growth, high-income countries representing 15 per cent of the world’s population still account for two-thirds of world exports – a modest decline from the position in 1980.’

The success of any country vis-à-vis another depends on how competitively (ie how cheaply) it can price its goods in the world market. This competition inevitably means cutting costs and the easiest costs to cut are wages. But, as we have already seen, cheap labor exports inevitably backfire by undermining domestic purchasing power and depressing domestic demand. Simply put: workers earn less so they have less to spend. As University of Ottawa economist Michel Chossudovsky notes: ‘The expansion of exports from developing countries is predicated on the contraction of internal purchasing power. Poverty is an input on the supply side.’20

Over the past 15 years, the UN has documented a steady shift of global income from wages to profits. Even so, investors are no longer satisfied with five or six per cent annual returns. Trade and investment barriers started to crumble as economic globalization took hold. But corporations, banks and other major investors were looking for quicker ways of maximizing their returns. The solution was at hand. From the ‘real’ economy of manufacturing and commodity production, investors turned to the world of international finance. Speculation and gambling in international money markets seemed easier than competing for fewer and fewer paying customers in the old goods and services economy. Welcome to the era of the ‘global casino’.

1 Helena Norberg-Hodge ‘The march of the monoculture’, The Ecologist, Vol 29, No 2, May/Jun 1999. 2 Benjamin R Barber, Jihad vs McWorld, Ballantine Books, New York, 1995. 3 Comparison of the World’s 25 Largest Corporations with the GDP of Selected Countries: 2010’, Global Policy Forum, globalpolicy.org 4 Sarah Anderson and Jon Cavanagh, Top 200: the Rise of Corporate Global Power, Institute for Policy Studies, Washington, 2000. 5 Mergers & Acquisitions 2013, Thomson Reuters, nin.tl/MandA2013 6 Jennifer Wells, ‘Loss of Heinz and ketchup-making devastates Leamington’, Toronto Star, 23 May 2014. 7 Susan George, ‘A short history of neo-liberalism’, paper presented to the conference on Economic sovereignty in a globalizing world, Bangkok, March 1999. 8 Fact Sheet: ‘Trends in US Correction’, The Sentencing Project, sentencingproject.org 9 Anna Lappé, ‘World Bank wants water privatized, despite risks’, Aljazeera America, 17 April 2014. 10 K Bayliss, ‘Privatization and poverty’, Jan 2002, http://idpm.man.ac.uk/crc/ 11 ‘The theft of the century’, Multinational Monitor, Jan/Feb 2002. 12 ‘Privatization and the Looting of Russia’, Multinational Monitor, Jan/Feb 2002. 13 Arundhati Roy, Power politics, South End Press, Boston, 2001. 14 ‘FDI Inflows, Top 20 host economies 2013’, UNCTAD. 15 ‘90 more Downsview plan jobs may flee’, Toronto Star, 27 Sep 2005. 16 nin.tl/corptaxrates 17 Excerpted from David Bacon, ‘Up for grabs’, New Internationalist, No 374, Dec 2004. 18 This description of the battle against the MAI owes much to Tony Clarke and Maude Barlow, MAI Round 2: new global and internal threats to Canadian sovereignty, Stoddart, 1998. 19 ‘Making Sense of the CETA’, Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, Sep 2014, policyalternatives.ca 20 Michel Chossudovsky, The globalization of poverty, Third World Network, 1997.