5 Global casino

The deregulation of the finance sector, coupled with the digital revolution, has sparked a surge in the international flow of capital. Uncontrolled speculation has eclipsed long-term productive investment and poses a huge threat to the stability of the global economy. Recent financial crises, including the crash of 2008, have caused suffering for millions and confirm the need for urgent action to control the money markets and rein in currency traders.

The acceleration of economic globalization is dramatically altering life for people around the world. As wealth increases for a minority, disparities between rich and poor widen and the assault on our planet’s natural resources speeds up.

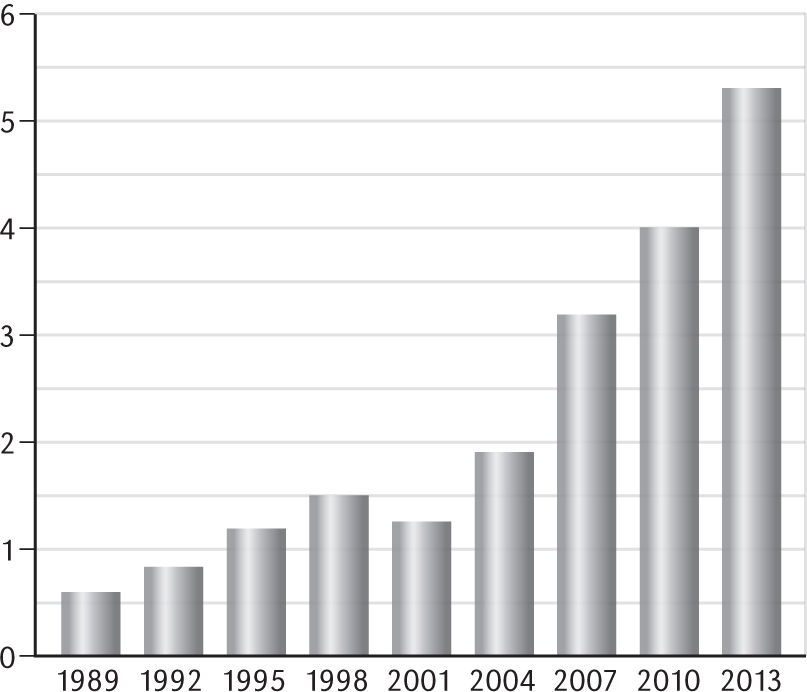

But the biggest and most dangerous change over the past 35 years has been in the area of global finance. The volume of worldwide foreign-exchange transactions has exploded as country after country has lowered barriers to foreign investment. In 1980, the daily average of foreign-exchange trading totalled $80 billion. In 2013, the Geneva-based Bank for International Settlements (BIS) estimated that more than $5,300 billion changes hands every day on global currency markets. That’s an astounding $1,934,500 billion a year, more than 100 times greater than the total value of all goods and services traded globally during the same period. This is an unimaginable sum of money.1 But it is all the more stunning when you realize that most of this investment has almost nothing to do with producing real goods or services for real people. Less than five per cent of all currency trading is linked to actual trade. The rest is speculative profit-seeking.

The world of international finance is technically arcane but the main point is easily understood. The goal is to make money – the end-use of the investment is relevant only to the extent that it is profitable. As growth in the real economy declines due to overcapacity and shrinking wages worldwide, speculative investment has grown. Money chasing money has eclipsed productive investment as the engine of the global economy.

There are very few controls on the movement of international capital. Yet the predominant view of the Bretton Woods institutions, the giant global banks and private corporations is that the world needs more financial liberalization, not less.

Others are not so sure. They’re more inclined to believe what Keynes wrote in his 1936 book The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money. ‘Speculators may do no harm as bubbles on a steady stream of enterprise. But the position is serious when enterprise becomes the bubble on a whirlpool of speculation.’

The rules for running the global economy, laid down at the 1944 Bretton Woods Conference, specifically sought to rein in finance capital and contain it within national borders. Keynes, Britain’s chief delegate at the gathering, warned that unregulated flows of capital would remove power from elected politicians and put it into the hands of the rich investors – whose ultimate allegiance was to their own self-interest.

Short-term speculation wreaks havoc

Today that self-interest is creating global havoc. Since governments in the industrialized countries began to deregulate financial markets in 1979, short-term speculation has become the single largest component in the flow of international investment. Managers of billion-dollar hedge funds, mutual funds and pension plans move money in and out of countries at lightning speed based on fractional differences in exchange rates. This volatile flow of currency is almost completely detached from the physical economy. For every dollar that is needed to facilitate the trade in real goods, nine dollars is gambled in foreign-exchange markets.

Critics of corporate-led globalization charge that unregulated flows of capital pose a major threat to the stability of the world economy, turning it into a ‘global casino’. This free flow of capital has also had a direct political impact, leaving national governments hostage to market forces. Any departure from the received wisdom is instantly punished. Without regulation, investors can pull up stakes at a moment’s notice. Governments are hesitant to introduce laws that might upset investors and cause capital to flee, taking potential jobs with them and possibly sparking economic chaos. This threat is a powerful brake on national sovereignty, reducing the political space for governments to control their own economic destiny. Such is the power of finance capital today.

The development of sophisticated computerized communications, combined with a global push for financial deregulation in the early 1980s, opened the doors to speculative investment. A decade later, the World Bank, the IMF and the US Treasury preached the gospel of liberal financial markets, pressing Third World governments to open up their stock markets and financial services (banks, insurance companies, bond dealers and the like).

As noted, the Bretton Woods agreements specifically sought to limit the movement of finance capital and contain it within national borders. Article VI of the original IMF Articles of Agreement allows members ‘to exercise such controls as are necessary to regulate international capital movements’. But free-market ideologues dismissed these concerns as old-fashioned and irrelevant in the modern world.

Under pressure from what Columbia University economist Jagdish Bhagwati calls the ‘Wall Street/Treasury complex’, governments in the early 1980s began to dismantle controls on the flow of capital and cross-border profits. Bhagwati argues that lax capital controls serve the ‘self-interest’ of financiers by enlarging the area in which they can make money.2

At the same time the financial-services industry itself underwent an unprecedented revolution, sparking a wave of mergers, acquisitions and overseas expansion. In most countries, banks, trust companies, insurance companies and investment brokerages were given the right to fight for each other’s business and to compete across international borders. This level of deregulation had not been witnessed in Western countries since the Depression of the 1930s.

The boom in the finance industry was closely linked to the digital revolution. Computerization means currency traders can move millions of dollars around the world instantly with a few taps on a computer keyboard. Investors profit from minute fluctuations in the price of currencies. The result is what Filipino activist Walden Bello calls global arbitrage – a game where ‘capital moves from one market to another, seeking profits…by taking advantage of interest-rate differentials, targeting gaps between nominal currency values and the “real” currency values, and short-selling in stocks – borrowing shares to artificially inflate share values, then selling.’3 Volatility is central to this high-tech world of instant millions and Bello, among others, argues that it has become the driving force of the global capitalist system as a whole. According to the Wall Street Journal, ‘Increased activity by smaller banks, hedge funds and computer-driven trading programs that can buy and sell currencies in milliseconds’ has fuelled speculative trends. As a result, says the BIS, the volume of currency trading from these sources ballooned by 53 per cent from 2010 to 2013.4

Financial crises proliferate

Besides speculating in foreign-exchange markets, money managers may also choose to put their funds into direct investment or portfolio investment. Foreign direct investment (FDI) – which tends to be stable and more long-term – occurs when foreigners buy equity in local companies, purchase existing companies or actually start up a new factory or business. Foreign portfolio investment (FPI) – which is typically more volatile – is when foreigners buy shares in the local stock market. The trouble begins because portfolio investors have few ties to bind them to the countries in which their funds are invested. In the current global system, where liberalized financial markets are the norm, there are no constraints to prohibit investors from selling when they’ve turned a quick profit or from exiting at the first signs of financial difficulties.

More than $5 trillion ($5,000 billion) changes hands daily on global currency markets.

• An estimated 95% of all forex deals are short-term speculation; more than 80% are completed in less than a week and 40% in less than two days.

• From 2010 to 2013 the daily volume of forex transactions increased by 32% from $4 trillion to $5.3 trillion. Three days of foreign exchange turnover is enough to cover world trade for a year. The US dollar was dominant, accounting for $4.6 trillion or 87% of the daily total in 2013.

• It is estimated that a ‘Robin Hood’ tax of just 0.5% on all financial transactions would discourage speculators and raise more than $400 billion yearly for global development. Transaction taxes already exist in Hong Kong, Mumbai, Seoul, Johannesburg and Tapei.

Rate of growth of foreign exchange markets

Figures for daily turnover in foreign exchange trading Trillions of dollars

UNCTAD documented the shift from FDI to FPI during the 1990s. According to its 1998 World Investment Report, FPI accounted for a third of all private investment in developing countries from 1990 to 1997. And in some countries, like Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, Thailand and South Korea, portfolio investment actually outpaced direct investment. Portfolio investment is also funnelled through offshore tax havens and other ‘friendly’ regulatory regimes. For example, FPI in Luxembourg in 2012 was $2.3 trillion. In the Cayman Islands the figure was $2 trillion – a thousand times bigger than the nation’s relatively tiny GDP of $2 billion. In the same year, FPI also exceeded GDP in Aruba, Vanuatu, Malta, Guernsey and the Isle of Man.5

UNCTAD notes that increasing FPI can signal a more volatile global economy because portfolio investors are ‘attracted not so much by the prospect of long-term growth as by the prospect of immediate gain’. Thus they are prone to herd behavior, which can lead to ‘massive withdrawals’ in a crisis.

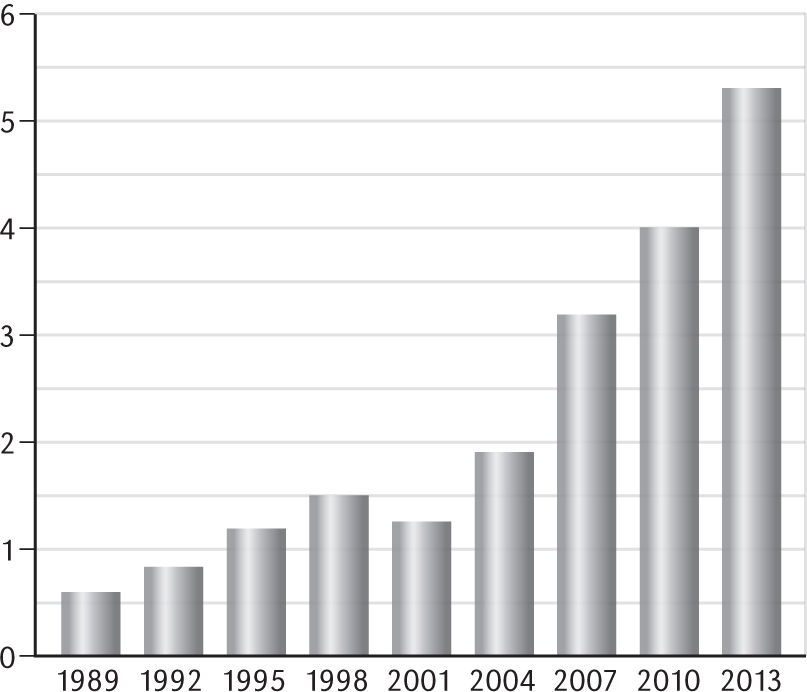

And there have been plenty of such crises. One 2002 study from the US National Bureau of Economic Research found that there were 48 financial crises around the world from 1949 to 1971 and 139 from 1973 to 1997 in the era of hyper-deregulation. Research by IMF economists Luc Laeven and Fabián Valencia found there were 146 banking crises, 218 currency crises and 66 sovereign debt crises from 1970 to 2011, noting that these types of financial crises often overlap.

Since the 1997 meltdown in Asia, there have been financial crises in Russia, Brazil, Turkey and Argentina. And of course, the global crash of 2008 was a watershed. The following year banking crises emerged in Denmark, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Mongolia and Ukraine; then in Kazakhstan in 2010 and in Nigeria and Spain in 2011. Each of these required active intervention by international financial institutions and national governments to keep the world system from collapsing.

Number of national economies with banking crises (1970-2012)

Source: ‘From the Oil Crisis to the Great Recession: Five crises of the world economy’, José A Tapia, Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

We are still living with the legacy of the 2008 collapse. Details of the ‘sub-prime mortgage crisis’ are now well known. A combination of greed and speculation by banks, mortgage companies and investment firms led to a colossal housing bubble in the US and Europe. Cheap mortgages triggered a frenzy of activity and a surging real-estate market. It was a classic ‘bubble’ mentality, with everyone hoping to make a quick buck. US bankers offered sub-prime mortgages to buyers who were living from pay check to pay check. Exotic new financial instruments were invented (‘credit default swaps’ and ‘collateralized debt obligations’). Cheap mortgages were bundled, sold and resold, spreading the risk – and the potential damage – across the global banking system. When US interest rates were raised to stifle inflation, mortgage payments became too expensive for low-income homeowners, forcing many into default. As the market collapsed, house prices fell. Many people with sub-prime mortgages ended up owing more than their house was worth. As a result, tens of thousands of lenders had no way of recouping their loans. Rising defaults pushed many US mortgage companies into bankruptcy. But the ‘toxic assets’ also infected overseas banks that had joined the hyper-inflated US market. With losses mounting and fear spreading, the whole system went into shock and began to shut down. Confidence disappeared. Banks refused to lend to each other; money markets froze; credit dried up and economic growth ground to a halt.

The bursting of the US sub-prime housing bubble brought untold calamity to millions of people around the world. Families lost their homes, their jobs, their dignity and their self-esteem. According to the IMF, there were 16 million more unemployed in 2012 than in 2007, most of those in industrialized countries. And that figure is surely an underestimate, since such data is notoriously unreliable.

To staunch the financial hemorrhaging, governments around the world pumped more than $15 trillion into the global economic system, bailing out banks, debt-strapped car companies and insolvent insurance firms. The stated purpose of this Keynesian-style fiscal stimulus: to revive economic growth.

Just a decade earlier, the 1997 Southeast Asian crisis had prefigured the 2008 collapse. The Southeast Asian economy went into freefall in the summer of 1997. In the 18 months prior to the crash more short-term investment had entered the region than in the previous 10 years. Capital flows into Thailand and Malaysia in the 1990s amounted to more than 10 per cent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and most of that speculative cash went into short-term debt. Previously, these nations had been more cautious about foreign investment and had taken steps to develop domestic industry by closing the door to cheaper imports from the West.

All that changed in the 1990s when these Southeast Asian countries became star pupils of the so-called ‘Washington Consensus’. Both the IMF and the World Bank had advised the countries to deregulate their capital accounts as a way of enticing foreign investment and kick-starting the development process. Around 1990 Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia and the Philippines all adopted an open-door policy to foreign investment. Measures included jacking up domestic interest rates to attract portfolio investment and pegging the national currency to the dollar to ensure that foreign investors wouldn’t get hit in the event of sudden shifts in the value of the currency.

In one of the most thorough examinations of the impact of ‘hot money’ on national economies, Walden Bello outlines the case of Thailand. In 1994 the World Bank noted in its annual report that ‘Thailand provides an excellent example of the dividends to be obtained through outward orientation, receptivity to foreign investment and a market-friendly philosophy backed up by conservative macro-economic management and cautious external borrowing policies.’

Ironically, it was in Thailand that the economic boom first began to fizzle – sparked by the herd mentality of short-term investors. In 1992-93 the country gave in to IMF pressure and adopted a radical deregulation of its financial system.6 Measures included: fewer constraints on the portfolio management of financial institutions and commercial banks; looser rules on the expansion of banks and financial institutions; dismantling of foreign-exchange controls; and the establishment of the Bangkok International Banking Facility (BIBF). The BIBF was a way for both local and foreign banks to take part in offshore and onshore lending. Firms licensed by the BIBF could both accept deposits and make loans in foreign currencies, to residents and non-residents. Most of the foreign capital entering the country soon came in the form of BIBF dollar loans.

The capital that flooded into Thailand was neither patient nor rooted. Most of it was invested not in goods-producing industries but in areas where profits were reckoned to be sizable and quick. Millions poured into the stock market (which inflated prices beyond their real worth) and into real estate and various kinds of easy consumer credit like car financing. By late 1996 there was an estimated $24 billion in ‘hot money’ in Bangkok alone. As a result of this offshore investment, the country’s foreign debt ballooned from $21 billion in 1988 to $89 billion in 1996. The vast majority of this – more than 80 per cent – was owed to the private sector.7

The Asian meltdown

It was a similar story throughout the region. South Korea’s foreign debt nearly tripled from $44 billion to $120 billion from 1993 to 1997 – and about 70 per cent of that was in short-term, easily withdrawn funds. In Indonesia, companies outside the financial sector built up $40 billion in debt by the middle of 1997, 87 per cent of which was short-term. According to official figures the five countries in the region (Indonesia, Thailand, Malaysia, the Philippines and South Korea) had a combined debt to foreign banks of $274 billion just before the crisis: 64 per cent of that was in short-term obligations. This was a recipe for financial disaster.

Much of the speculative capital in Thailand went into real estate, always a favorite for those with a get-rich-quick dream in mind. So much money was pumped into Thai real estate that the value of unsold office buildings and apartments in the country nudged $20 billion. It was this massive bubble that finally frayed the nerves of foreign investors. When they woke up to the fact that most of their money was tied up in property, for which there were no buyers, and that Thai banks were carrying billions in bad debt that could not be serviced, investors panicked and hurried to withdraw their funds. The anxiety (later dubbed the ‘contagion effect’) spread quickly from Thailand and Malaysia to Indonesia, the Philippines and South Korea. Like the plague in medieval Europe, this financial chaos was felt to be a contagious disease that could jump national borders.

In just over a year there was a complete turnaround in the capital account of the region: in 1996, new financial inflows to the five countries totalled $93 billion. In 1997, $105 billion left those same countries – a net outflow of $12 billion. All investors rushed for the exit at the same time because none of them wanted to get caught with depreciated local currency and assets.8

The vicious downward spiral picked up speed – egged on by speculators who intervened massively in foreign-exchange markets and helped to seriously devalue local currencies. Under speculative attack, the governments of the region did what they could to ward off the inevitable. The first line of defense was to raid their own foreign-exchange reserves to buy up their national currency in a last-ditch attempt to maintain its value. Under pressure from speculators, the Bank of Thailand lost almost all its $38.7 billion in foreign exchange holdings in just six months. But to no avail. Speculators continued to bail out in droves. The next step was to float their currencies, but that too backfired, proving a catalyst for further devaluation. The Thai baht lost half its value in a few months. So the hemorrhage of foreign funds helped both to deplete foreign-exchange reserves and to drive down the value of domestic currencies.

The baht felt the pressure first but the devaluation soon spread to the other countries. As the currencies drifted downwards, local firms that had borrowed from abroad had to pay more in local currency for the foreign exchange needed to service their overseas debts. At the first sign that things were spinning out of control, many foreign banks and other creditors refused to roll over their loans. They demanded immediate repayment. At this point the panic that gripped the region suddenly became a crisis threatening to capsize the entire global economy. Soon, international financial operators were selling baht, ringgit and rupiah in an effort to cut potential losses and get their funds safely back to Europe and the US. In the ensuing capital flight, Asian stock prices plunged and the value of local currencies collapsed. Businesses that had taken out dollar-denominated loans couldn’t afford the dollar payments to Western creditors.

For a time, governments tried to stave off default by lending some of their foreign-currency reserves to the indebted private companies. South Korea used up some $30 billion in this way. But the money soon ran out and Western banks refused to make new loans or to roll over old debts. Asian businesses defaulted, cutting output and laying off workers. As the region’s economies sputtered, panic intensified. Asian currencies lost 35 to 85 per cent of their foreign-exchange value, driving up prices on imported goods and pushing down the standard of living. Businesses large and small were driven to bankruptcy by the sudden drying up of credit; within a year, millions of workers had lost their jobs while the prices of imports, including basic foodstuffs, soared.

In an effort to calm investors and forestall total financial collapse the International Monetary Fund (IMF) introduced a $120-billion bailout plan. But the IMF rescue package just made a bad situation worse – not least for the citizens of those nations who had to endure the impact of the Fund’s loan conditions. One of the central requirements of the package was that governments guarantee continued debt service to the private sector in return for creditors being persuaded to roll over or restructure their loans. This mirrored the IMF’s role during the Third World debt crisis of the 1980s. Public money from Northern taxpayers (via the Fund) was handed over to indebted governments, and then recycled to commercial banks in the South to pay off their debts to private investors. In Asia some critics dubbed this bailout of international creditors ‘socialism for the global financial elite’.

The IMF’s Asian package also forced countries to further liberalize their capital account. The goal was to cut government expenditure and produce a surplus. The standard tools were applied: high interest rates combined with cuts to both government expenditures and subsidies to basics like food, fuel and transport. The high interest rates were supposed to be the bait to lure back foreign capital. But the bait didn’t work. Tight domestic credit, combined with high interest rates, sparked a much sharper recession than would have otherwise taken place and did nothing to restore investor confidence.

A pocket guide to the language of the financial market place.

• Hedging

If a business holds stocks of a commodity like cocoa or copper it runs the risk of losing money if the price falls before it can unload it all. This loss can be avoided by ‘hedging’ the risk. This involves selling the item before the purchaser actually wants it – ie for delivery at an agreed price at a future date. Hedge funds make a business of selling and buying this risk, often using borrowed money to put together ‘highly leveraged’ deals. The most infamous hedge fund, the US firm Long Term Capital Management (LTCM), had to be rescued with a $3.5 billion bailout from other Wall Street investment companies after it overextended itself to the tune of $200 billion. The firm had invested $500 million of borrowed money for every $1 million it invested of its own cash.

• Futures, options and swaps

A futures contract is an agreement to buy or sell a commodity or shares or currency at a future date at a price decided when the contract is first agreed. An option is like a futures contract except that in this case there is a right, but no obligation, to trade at an agreed price at a future date. An interest-rate swap is a transaction by which financial institutions change the form of their assets or debts. Swaps can be between fixed and floating rate debt, or between debt in different currencies.

• Derivatives

A sweeping, catchall term used to refer to a range of extremely complex and obscure financial arrangements. Futures contracts, futures on stock market indices, options and swaps are all derivatives. In general, derivatives are tradable securities whose value is ‘derived’ (thus the name) from some underlying instrument which may be a stock, bond, commodity or currency. They can be used as a hedge to reduce risks or for speculation. According to the Bank for International Settlements the notional value of all derivatives in effect in June 2007 was $516 trillion, which dwarfs the value of all the world’s stock markets combined.

• Stock market indices

The most famous are the Dow Jones Industrial Average, an index of share prices on the US stock market based on 30 leading US companies, the FTSE 100, an index of Britain’s 100 top companies and the Japanese equivalent, the NIKKEI 225.

• Foreign exchange market

This is where currencies are traded. There is no single location for this market since it operates via computer and telephone connections in an interlaced web linking hundreds of trading points all over the world. The total turnover of world foreign exchange markets is enormous, many times the total international trade in goods and services.

• Mutual funds/Unit trusts

A financial institution which holds shares on behalf of investors. The investors buy shares or ‘units’ in the fund, which uses their money to buy shares in a range of companies. An investor selling back the units gets the proceeds of selling a fraction of the fund’s total portfolio rather than just shares in one or two companies.

• Equities

The ordinary shares or common stock of companies. The owners of these shares are entitled to the residual profits of companies after all claims of creditors, debenture holders and preference shareholders have been satisfied. These are paid out to stock owners in the form of dividends.

• Junk bonds

Bonds issued on very doubtful security by firms where there is serious doubt as to whether interest and redemption payments will actually be made. Because these bonds are so risky, lenders are only prepared to hold them if promised returns are high enough.

Output in some countries fell 16 per cent or more, unemployment soared and wages nose-dived. In Thailand, GDP growth-rate estimates plummeted after the IMF intervention, from 2.5 per cent in August 1997 to minus 3.5 per cent in February 1998. In Indonesia, the IMF forced the Government to close down 16 banks; a move it thought would restore confidence in the notoriously inefficient banking system. Instead it led to panic withdrawals by customers at the remaining banks, which brought further chaos. It is estimated that half the businesses in the country went bankrupt.

The impact on the region was stunning. According to the International Labour Organization (ILO) more than 20 million people in Indonesia were laid off from September 1997 to September 1998. UNICEF said that 250,000 clinics were closed. The Asian Development Bank said that more than six million children dropped out of school. And Oxfam estimated that over 100 million Indonesians were living in poverty a year after the crisis – four times more than two years earlier.9

There was also a frightening resurgence of racial ‘scapegoating’ and inter-communal violence throughout the region. Malaysia’s leader at the time, the autocratic Mahathir Mohamad, blamed Jewish financiers for destabilizing his Muslim country, while in Indonesia the shops of ethnic-Chinese merchants were looted and burned and hundreds of Chinese brutally beaten and killed.

There were, however, some clear winners that emerged from the Asian meltdown. The big ones were the Western corporate interests that rushed in to snap up the region’s bargain-basement assets after the economic collapse. As former US Trade Representative Mickey Kantor said at the time, the recession in the ‘Tiger Economies’ was a golden chance for the West to reassert its commercial interests. ‘When countries seek help from the IMF,’ he said, ‘Europe and America should use the IMF as a battering ram to gain advantage.’10

That was certainly true in South Korea, where the IMF agreement lifted restrictions on outside ownership so that foreigners could purchase up to 55 per cent of Korean companies and 100 per cent of Korean banks. Years of effort by the Korean elite to keep businesses firmly under control of state-supported conglomerates called chaebols were undone in a matter of months. In January 1998, the French investment firm Crédit Lyonnais estimated that just 87 of the country’s 653 non-financial firms were safe from foreign buyers. US economist Rudi Dornbusch. accurately summed up the overall impact of the economic slump: ‘Korea is now owned and operated by our Treasury. That’s the positive side of this crisis.’11

Why capital controls offer protection

A key reason why the Asian economies were so vulnerable to currency destabilization was that they had gradually abandoned controls over the movement of capital. When a country cedes control over capital flows, it effectively removes any tools it may have for intervening in the market process, leaving itself at the mercy of speculators whose only concern is profit. More critically, nations lose the ability to control internal economic strategies which lie at the heart of national sovereignty. How can a nation hope to determine its own social agenda and economic future if key policy areas are shaped by the self-interest of foreign investors and money markets?

At the time of the Asian meltdown, one country emerged from the chaos in noticeably better shape than the others. Although Malaysia’s GDP fell by 7.5 per cent in 1998, the nation managed to escape the devastating social impact felt elsewhere. Partly this was because Malaysia adopted a range of defensive measures to limit capital flight, many of which were modelled on China’s example.

The Malaysian Central Bank ruled that private companies could only contract foreign loans if they could show that the loans would end up producing foreign exchange which then could be used to service the debt. And like China, Malaysia also pegged its currency, the ringgit, to the US dollar and allowed it to be freely converted to other foreign currencies for trade and direct investment. Critically, portfolio investors had to keep their funds inside Malaysia for a minimum of one year and the amount of money residents could take out of the country was restricted.

Most important, trade in ringgit outside the country was not recognized by the government and this helped to prevent manipulation by currency speculators. Measures were also taken to reduce foreign investment in the Malaysian stock market. The controls allowed the government to stimulate the domestic economy with tax cuts, lower interest rates and spending on public infrastructure – without having to worry about speculators targeting its currency. Interest rates fell from 11 to 7 per cent, a helpful boon to local businesses and the domestic banking industry.

Despite its authoritarian political structure, China was also able to sidestep the Asian trap – mainly by avoiding becoming entangled in international financial markets. At the time of the Asian financial crisis, China had considerably more control over its domestic economy than just about any nation in the world. Its currency, the renminbi, was not freely convertible; its finance system was owned and controlled by the state and there was relatively little foreign investment in the Chinese stock market. Plus the world’s biggest nation was not then a member of the WTO – the country did not become a full member of the organization until December 2001.

As a result, China was not vulnerable to the speculative herd behavior that devastated other countries in the region. Instead of devaluing its currency and trying to grab a share of its neighbors’ exports, China took another tack. The government decided to direct national savings into a $200-billion public-works program to stimulate its domestic economy.12

Latin American responses

Chile is another country that successfully tried to regulate destabilizing short-term flows of foreign capital by installing a series of financial ‘speed bumps’ to slow down speculation. When Mexico’s economy crashed in 1995, Chile was able to escape the worst ‘contagion’ effects because of its encaje policy. This regulation required foreign investors to deposit funds equivalent to 30 per cent of their investment in Chile’s central bank. In addition, portfolio investors were required to keep their cash inside the country for a minimum of at least a year. These barriers slowed down the exodus of funds from Chile and kept it from falling victim to what the financial press dubbed Mexico’s ‘tequila effect’.

Shaken by the Asian debacle, Western finance ministers, led by the US, came up with a new plan to aid countries experiencing balance-of-payments shortfalls before such a crisis occurred. The idea was to give more money (up to $90 billion) and more power to the IMF to create ‘an enhanced IMF facility for countries pursuing strong IMF-approved policies’. The thinking was that an instant loan from a ‘precautionary fund’ would make currency speculators less anxious and so tame the ‘hot money’ and stall devaluation.

Brazil was the first country to use the new IMF plan. Unfortunately, Brazil’s economy seemed no more immune to financial crisis than Indonesia or Thailand. When the Brazilian real came under attack in 1998 the government of Fernando Cardoso spent more than $40 billion in foreign exchange trying to prop it up. Cardoso also raised domestic interest rates to 50 per cent to try to keep capital from fleeing the country. Nevertheless traders continued to hammer the real even after the country signed a formal letter of intent with the IMF. By January 1999, nearly a billion dollars a day was exiting the country – the government had no choice but finally to devalue its currency, which lost nearly a third of its value overnight.

The Brazilian economy crashed as IMF policies kicked in. High interest rates scared off domestic business owners who could no longer afford to borrow. Budget cuts and public-sector layoffs increased poverty and unemployment as the government was forced to implement what the IMF called ‘the largest privatization program in history’. As in Asia, the IMF/US Treasury plan championed foreign investment, lured by high interest rates, as Brazil’s only long-term hope. Unfortunately, the Fund brushed aside the downside of interest-rate hikes – each percentage increase added millions to debt-service costs, all of which had to be repaid in hard currencies purchased with the devalued Brazilian real. By the end of 1999, Brazil’s total external debt, always the highest in the Global South, topped more than $230 billion.

The next Latin American nation to feel the pinch was Argentina, one of the first Latin nations fervently to embrace globalization. In December 2001, the country sent shockwaves around the world when the economy exploded into social chaos. In less than two weeks, five different presidents tried to take control and calm the increasingly violent demonstrations which had erupted across the country. ‘Que se vayan todos!’ the protesters chanted: ‘Out with the lot of them!’ – meaning all the politicians and the international financiers that had helped bring the country to its knees.

The crisis had its roots in the economic model pushed by the IMF in the early 1990s when Carlos Menem was President. In return for emergency balance-of-payments support, Argentina knocked down its trade barriers, liberalized its capital account and instituted a massive privatization of state enterprises. Nearly 400 companies – from oil and water to steel, insurance, telephone and postal services – were sold off to foreign interests. Corruption was rife: Menem and his cronies grew rich in the process.

But what really attracted speculators was the government’s move to peg the Argentine peso to the US dollar at an exchange rate of one-to-one. This effectively removed all control over the domestic economy from the hands of the government. The IMF happily endorsed the arrangement.

Then things began to unravel. With a fixed exchange rate and the dollar rising in value, Argentine goods quickly became uncompetitive, both globally and locally. Cheaper imports flooded the country as the once-thriving agricultural sector slumped. Even the world-famous Argentine beef industry saw export markets dry up. The country had to borrow more foreign currency to finance the growing trade gap, further increasing an already heavy debt burden. Soon lenders began to get the jitters, credit disappeared and businesses lurched into bankruptcy.

In December 2001, Argentina again approached the IMF for a loan to meet its $140-billion external debt. When the Fund balked, the country defaulted on $100 billion of its debt, and then quickly spiralled into recession. In a few short months, unemployment spiked to 21 per cent, GDP declined nearly 17 per cent and more than half of Argentineans were living below the poverty line. Something had to give.

Fed up with political corruption and the destructive impact of foreign debt, the Argentine people began to demand more control over their economic lives. The collapse sparked a flurry of worker-run enterprises, co-operatives, alternative currencies, barter exchanges and other self-help institutions. More than 200 companies were taken over and managed by their employees after their owners shut up shop.

In May 2003, the populist government of Nestor Kirchner was elected. In a bold move, Kirchner told debtors he would write off 75 per cent of his country’s $100-billion debt in defaulted government bonds – take it or leave it. In September 2003 he also convinced the IMF to roll over $21 billion in outstanding debt, insisting that no more than three per cent of the nation’s budget would be used for debt servicing. Pushed to the wall, the IMF caved in.

‘We are not going to repeat the history of the past,’ said Kirchner. ‘For many years we were on our knees before financial organizations and the speculative funds…We’ve had enough!’13

In an astonishing turnaround, the country finally cleared its account with the Fund in January 2006, repaying $9.57 billion in debt and gaining a measure of economic autonomy not felt for decades.

It wasn’t easy. Argentina got no help from the IMF along the way. The Fund opposed policies that led to recovery – a stable exchange rate, low interest rates and a tax on exports. A stable currency was important to keep the peso from becoming overvalued. Priced competitively, exports would grow and encourage local investment. Instead the IMF wanted to increase the price of public services like water and electricity, run bigger budget surpluses and pay off foreign creditors, all to please the markets. But the Kirchner government held fast – and the economy responded by growing by nearly nine per cent yearly from 2003 to 2008. Social spending tripled in real terms. Employment rose to a record high and real wages increased by over 40 per cent. Consequently, poverty declined and inequality was reduced.

This was an amazing accomplishment, all the more so because the country continued to service its other debts during that time. By 2005 more than 75 per cent of Argentina’s creditors had agreed to debt restructuring and by 2010 more than 90 per cent had reached an agreement.

Not that Argentina is completely out of the woods. Since 2012 the country has been under attack by billionaire hedge fund manager Paul Singer and his company, NML Capital. Singer snapped up millions of dollars’ worth of Argentine debt in 2006 for pennies on the dollar and since then has been squeezing the country at every opportunity. NML Capital is looking for a 1,600-per-cent return on its bonds. Singer’s ‘vulture fund’ has even attempted to seize Argentine assets overseas, a claim that was bolstered by Judge Thomas Griesa of the US District Court of New York in the summer of 2014. Griesa ruled that Argentina must pay Singer all the debt claimed before continuing to service the bonds it restructured in 2005 and 2010. (The Court also upheld NML’s demand that Argentina identify overseas assets that can be seized in lieu of repayment.) But even servicing its restructured debt has taken a toll. The country has paid more than $174 billion in interest since 2004. Yet total debt has actually increased over that period from $43 billion to more than $240 billion.14

Still resisting regulation

Despite the obvious danger of capital ricocheting around the globe, the IMF and the US Treasury have been reluctant to support mechanisms to inhibit its movement. And speculators themselves have also been working overtime to squelch defensive government action against their attacks. Pressures to lift exchange controls were strong right up to the most recent financial 2008 crisis, which is covered in Chapter 7.

The original Bretton Woods agreement did not fulfil Keynes’ dream of giving ‘every member government the explicit right to control capital movements’, but the policies did give members some controls. Unfortunately, even these limited tools have been gradually eroded over the years by the growing insistence on deregulation. Market fundamentalists like Lawrence Summers, formerly Bill Clinton’s Treasury Secretary and chief economic advisor to Barack Obama, criticized efforts by Malaysia, Hong Kong and others to hobble the movement of overseas capital.

He called controls a ‘catastrophe’ and urged countries to ‘open up to foreign financial-service providers, and all the competition, capital and expertise they bring with them’. Given the damage inflicted on millions by the fickle nature of short-term speculators, Summers’ views are both myopic and harmful. The fact that he is still a powerful Washington insider does not instil confidence that the radical regulatory changes needed to fend off future economic disasters will be made.

As citizens from Korea to Argentina have seen their lives wrecked by the whipsaw effect of one global financial crisis after another, it has become painfully evident that the old ways no longer work. The world has been led to the brink of financial chaos too often over the last few decades. Solutions are needed urgently to ensure that money markets, bond traders and currency speculators are brought under the control of national governments for the public good.

1 ‘Global FX volume reaches $5.3 trillion a day in 2013 – BIS’, Reuters, 5 Sept 2013 and International Trade World, OECD StatExtracts, stats.oecd.org. 2 Jagdish Bhagwati, ‘The Capital Myth: the difference between the trade in widgets and the trade in dollars’, Foreign Affairs, May/Jun 1998. 3 Walden Bello, Dilemmas of Domination, Zed Books, London, 2005. 4 ‘Global Currency Trading Volumes Show October Increase’, Wall Street Journal, 28 Jan 2014, online.wsj.com/articles 5 IMF Coordinated Portfolio Investment Survey, cpis.imf.org. 6 Walden Bello, ‘Domesticating Markets’, Multinational Monitor, Mar 1999. 7 Testimony of Walden Bello before the House Banking Committee, US House of Representatives, 21 Apr 1998. 8 Human Development Report 1999, UNDP/Oxford University Press. 9 Oxfam East Asia Briefing, available from oxfam.org.uk 10 Quoted in Mark Weisbrot, ‘Globalization for Whom?’, Preamble Center, preamble. org/globalization 11 Quoted in ‘Asian Crisis Spurs Search for New Global Rules’, Economic Justice Report, Jul 1998. 12 Mark Weisbrot, ‘The Case for National Economic Sovereignty’, Third World Network Features, Jul 1999. 13 Roger Burbach, ‘Can’t pay, won’t pay’, New Internationalist No 374, Dec 2004. 14 ‘We don’t owe, we won’t pay!’ Jubilee South, Jul 2014, dialogo2000.blogspot.co.uk