Mark Twain memorably observed that “the Mississippi … is not a commonplace river, but on the contrary is in all ways remarkable.” He also called it “the crookedest river in the world, since in one part of its journey it uses up one thousand three hundred miles to cover the same distance that the crow would fly in six hundred and seventy-five.”1 This is a stupendous river by any standards, 3,779 kilometers long, with a huge triangular drainage area that covers about 40 percent of the United States, the third-largest river drainage in the world, exceeded only by the Amazon and the Congo. The river rises in Lake Itasca, Minnesota, and then flows through the heart of the Midwest. The Missouri River with its vast silt load, the Great Muddy, which drains the Great Plains, joins the Mississippi at St. Louis, the Ohio River at Cairo, Illinois. Below Cairo, the river flows through a wide, low valley, once a bay of the Gulf of Mexico, now filled with sediment. Today 966 kilometers downstream the Mississippi joins the Gulf. The river channel meanders over the low-lying plain, often contained between natural levees formed by flood sediments.

Through a natural process known as avulsion, literally delta switching, the river has meandered back and forth across the flat landscape of the Lower Mississippi valley ever since sea levels climbed in the Gulf of Mexico after the Ice Age. The river’s gradient shallows with the ocean’s rise, the flow slows, and the silt load sinks to form lobes of a huge delta in a regime that changed little for thousands of years—until humans started controlling the Mississippi. Sediment builds up; a channel becomes clogged; the river shifts course to a steeper route downstream. Meanwhile the abandoned channel receives less water and becomes a bayou. A major channel shift triggered by an unusually severe spring flood takes place about every thousand years. The last one would have inundated maize fields on the floodplain, but the ancient farmers, hunters, and fisherfolk on the flatlands and among the bayous would have adapted to the shift without trouble. Today’s river is long overdue for a dramatic channel shift, most likely down the Atchafalaya Basin or through Lake Pontchartrain near New Orleans. This time the human and economic stakes are very high indeed, with almost unthinkable consequences for cities like New Orleans and Baton Rouge. Only massive humanly constructed flood control works stand between millions of people and disaster from upstream.

Figure 13.1 Map showing locations in chapter 13.

Most of the Lower Mississippi’s water comes from the Ohio River and from downstream tributaries like the Arkansas and Red Rivers, only 15 percent from its own upper reaches. The Missouri contributes considerably less water, but massive quantities of silt, both of which flow down the Lower Mississippi. All these sources make for a complex flood regimen, especially when all major tributaries overflow at the same time. Such events resonate in historical memory. The Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 produced overflows so severe that the river reached a width of ninety-seven kilometers. On April 15, 385 millimeters of rain fell on New Orleans, covering parts of the city with more than two meters of water. The Flood Control Act of 1928 authorized the Army Corps of Engineers to construct the longest levee system in the world. With the new levees came at least some protection from raging floods, but also a new ever-present threat of highly destructive breaks in the defense walls caused by floods and hurricane-induced sea surges. For all the additional protection, many communities in the shadow of levees were potentially even more vulnerable than before.

THE ROUTINE NEVER changed—enormous flocks of migrating waterfowl flying northward in spring, south in fall, along what is now known as the Mississippi flyway. Thousands of birds would pause to feed and rest at shallow oxbow lakes near the great river. Each spring and fall, the hunters would wait in the reeds at dawn with traps and spears. They would use canoes to drive the birds into narrow defiles in the reeds, where they could be netted, or swim among them with duck decoys on their heads, then grab their unsuspecting prey by the feet from underwater. Back ashore, they preserve the birds by drying and soaking them in oil for later consumption. Storage was critical. Everyone living along the river had experienced food shortages caused by floods that could inundate wide tracts of the floodplain until as late as July.

Between about 4500 and 4000 B.C.E., the Mississippi and its tributaries slowed as sea levels stabilized. Silt from the now more sluggish river accumulated. Backwater swamps and oxbows formed, which proved to be a paradise for hunters camped along their floodplains. Apart from waterfowl, they thrived off fish and mollusks, also plant foods, which abounded, especially the nut harvests of fall. So plentiful were food supplies that many groups stayed in the same places for most, if not all, the year.

By 2000 B.C.E., the Lower Mississippi had become a complex political and social world. Most people now lived in small base camps, but sometimes clustered around somewhat larger centers, connected to other groups by intricate ties of kin and volatile rivalries. The largest of these centers comes as somewhat of a surprise in a world of hamlets and temporary camps. The great horseshoe-shaped earthworks and mounds of Poverty Point lie on the Macon Ridge in the Mississippi floodplain, near the confluences of six rivers and twenty-five kilometers from the great river itself. Six concentric semicircular earthen ridges divided into segments lie about forty meters apart. Apparently houses lay atop the earthworks, which were about twenty-five meters wide and three meters high, elevated above the surrounding low-lying terrain. To the west, an earthen mound stands more nearly twenty meters high and two hundred meters long. Over five thousand cubic meters of basket-hefted soil went into the Poverty Point earthworks.2

Figure 13.2 The earthworks at Poverty Point, Louisiana. © Martin Pate.

The concentric earthworks came into being in about 1650 B.C.E., surrounded by a network of lesser centers. Long-distance trade routes carrying exotic materials converged here, not only from upstream along the Mississippi, but also from the Arkansas, Red, Ohio, and Tennessee Rivers as well. Together, they formed the nexus of a vast exchange network that handled exotic rocks and minerals such as galena from more than ten sources in the Midwest and Southeast, some of them as far as a thousand kilometers away.

Poverty Point is a huge enigma. How many people lived there? Was this a center where hundreds of visitors gathered for major ceremonies, perhaps on occasions such as the solstices? A person standing on the largest Poverty Point mound can sight the vernal and autumnal equinoxes directly across the center of the earthworks to the east. This is the point where the sun rises on the first days of spring and fall, but whether this was of ritual importance remains a mystery. What is certain, however, is that Poverty Point was at the mercy of river floods and the vagaries of the Mississippi delta downstream.

The great center lies near natural escarpments, close to floodplain swamps, oxbow lakes, and upland hunting grounds. Like societies up and down the major rivers nearby, Poverty Point people were hunters and plant gatherers. They also cultivated a number of native species, such as sunflowers, bottle gourds, and squashes. The floodplain landscapes and their environs produced more than enough food for considerable numbers of people to live permanently in places as large as Poverty Point, but we still know little about them, or of the leaders behind the centers, who must have organized the communal labor needed to erect earthworks and mounds. Poverty Point was a prophetic forerunner of much more elaborate chiefdoms that flourished along the Mississippi and its tributaries a thousand years later. But, after centuries of gradual population growth and extensive long-distance trade, Poverty Point society gradually imploded. The exchange system collapsed after 1000 B.C.E. Three hundred years later Poverty Point was deserted. Everyone had moved away. Trade slowed, settlements were smaller, and any semblance of complex society vanished. One major factor may have been climate change.

Tracking climate change in the Lower Mississippi valley is an exercise in complexity, for riverbank breaks, shifts in large meander belts, and other geological processes resulted in major changes in human settlement, especially between about 1000 and 450 B.C.E. During these centuries, rainfall was higher and temperatures were cooler over wide areas of the world, higher rainfall notably causing increased flooding in the Netherlands, with abandonment of many low-lying areas. We know that cooler and wetter climate pertained in some parts of Minnesota and that there were larger than normal floods along Mississippi tributaries in southwestern Wisconsin. Out in the Gulf of Mexico, the Orca Basin traps sediment from the great river, whose varying size reflects the intensity of ancient floods. At least two flood cycles of unprecedented volume occurred between about 1000 and 550 B.C.E., which introduced large quantities of freshwater into the Gulf. Each of these major cycles lasted for as long as fifty years and must have had major effects on the hydrologic system of the Mississippi River basin. At the same time, between about 900 and 550 B.C.E., many more hurricanes and large storms came ashore along the Gulf Coast. The combined effects of lower temperatures, higher rainfall, and changed atmospheric circulation produced much more flooding along the Mississippi, with resulting serious disruption of daily life among the societies along its banks, perhaps the explanation for a sharp decline in the number of archaeological sites and possibly in human populations in the alluvial portions of the Mississippi River basin as Poverty Point was abandoned.

During the time when Poverty Point prospered, before 1000 B.C.E., the river enjoyed a period of relative geological stability.3 Around then, the Mississippi channel shifted north of Vicksburg, Mississippi, upstream of Poverty Point, causing westward migrations in river channels downstream, including Joe’s Bayou near Poverty Point, which became a major outlet for the river, just as major flooding affected the region. The floods rendered much of the alluvial plain uninhabitable for long periods of time, sweeping away ponds and sloughs where the people had harvested thousands of fish as floods receded. Fish densities may have plummeted in the now faster-moving water, which may have forced the groups who had relied on the fish harvests to rely more heavily on hunting and plant foods in the nearby uplands. No longer could people live in permanent settlements; the floods would have disrupted long-distance trade by canoe.

Mobility versus sedentary living: Poverty Point’s demise may be a classic example of increased vulnerability to rising water on the part of more permanent settlements. The change was not instantaneous; people and individuals respond to climatic events in complex ways. As more elaborate ancient societies came into being in later times, it’s noticeable that many villages lay on slightly higher, better-drained ground above the floodplain, even if they were near it. Over many centuries, people living along the river and in the bayous and swamps of the delta adapted effortlessly to a regime of flood and sea surge, an equation that changed dramatically with the arrival of European settlers. The cumulative effects of human efforts to control the river and its capricious flooding have now brought rising sea levels to the forefront in the complex minuet of ocean, river flood, and silt accumulation.

THE DANCE FLOOR is the shallow delta that forms the mouth of the river. As the Mississippi approaches the Gulf Coast, the current slows and deposits fine alluvium. Over the past five thousand years, the southern coast of Louisiana has advanced between twenty-four and eighty kilometers, forming twelve thousand square kilometers of coastal wetlands and extensive tracts of salt marsh. The latest cycle of delta development began as sea levels rose at the end of the Ice Age some fifteen thousand years ago. At the time, the mouth of the river was farther out in the Gulf, the current shoreline beginning to take shape about five thousand to six thousand years ago, when sea levels stabilized somewhat. Since then, the river has changed course repeatedly, as shorter and steeper routes to the Gulf have emerged upstream. As the river shifted, so the old delta lobe into the Gulf would lose its supply of alluvium, then compact and subside, retreating as the advancing ocean formed bayous, sounds, and lakes.

The Mississippi delta has always been a landscape of shifting currents, tides, and mudflats. This is a waterlogged, now-vanishing world, where you canoe through forests and occasional open clearings, where there is almost no solid ground. A confusing mosaic of forested basins and streams form the fretwork of the delta, which absorbs the flood and holds the water until it escapes to the Gulf. When floods spread water out over the surrounding countryside, the water slows and deposits silt, the finest dropping at the edges, closer to the river, where natural levees form.

Such levees were where the first European settlers built forts. In 1718, the settlement that was to become New Orleans rose on a natural levee, only to be waterlogged by a high flood. There was nowhere to go, so the settlers raised artificial barriers. At first, the main levee was just under a meter high, raised in part by a law requiring homeowners to do so—not that many of them did. Fortunately for the growing settlement, the floods could spread widely on the eastern bank of the river where there were no artificial levees. In 1727, the French colonial governor proudly announced that the levee was complete. Nevertheless, the city was inundated in 1735 and again in 1785. The intervals between severe floods were long enough that generational memory faded, but the levees were slowly extended along the west bank as far as the Old River, some 322 kilometers upstream and along the east bank as far as Baton Rouge. The levees were far from continuous, mainly protecting plantations. Elsewhere, the flood poured over the countryside as it had always done. Many plantation houses rose on the only higher ground—ancient Indian burial mounds.4

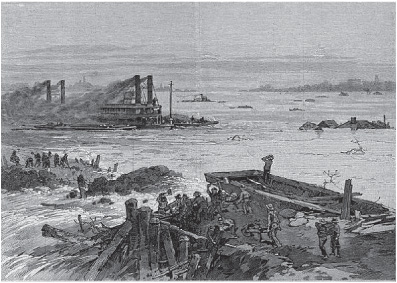

The more levees confined the river, the more destructive floods became when they broke through human barriers. By the mid-nineteenth century, it was clear that even raised levees would not contain the river as flows increased. Congress passed the Swamp and Overflow Lands Act in 1850, which deeded millions of hectares of swampland to the states. They in turn sold the swamp to landowners to pay for levees. The new owners drained most of the swamps, converted them into farmland, and then demanded larger and better levees to protect their investments. Catastrophic floods and levee breaks in 1862, 1866, and 1867 finally prompted Congress to form the Mississippi River Commission, charged through the Army Corps of Engineers to “prevent destructive floods.” The most ruinous inundation of the nineteenth century came in 1882, at which point it was becoming apparent that the Atchafalaya River could become the new main course of the Mississippi. By now the river flowed high above the surrounding landscape, confined only by its levees, a disaster waiting to occur, which finally transpired with the flood of 1927. This caused multiple breaches and destroyed every bridge across the river for hundreds of kilometers. Sixty-seven thousand square kilometers of surrounding country vanished underwater.

Figure 13.3 Repairing a levee on the Lower Mississippi. Drawing by Charles Graham. Author collection.

The Flood Control Act of 1928 provided funds for coordinated river defenses that were still incomplete in the 1980s. This time, the corps did more than raise levees. They straightened parts of the river, built spillways, like that at Bonnet Carré, nineteen kilometers west of New Orleans, which diverted water away from the city and into Lake Pontchartrain during a major flood in 1937. In places, levees now rose to more than nine meters, but increasingly the Army Corps turned its attention to the Atchafalaya, which flowed into one of the largest river swamps in North America.

Without human interference, the Lower Mississippi’s floodwaters would disperse widely over the delta plain through many outlets. Virtually the entire delta would be covered not only with floodwater but also with fine sediment derived from mountains hundreds of kilometers away. As the writer John McPhee remarks, “Southern Louisiana is a very large lump of mountain butter, eight miles thick where it rests upon the continental shelf, half of that under New Orleans, a mile and a third at Red River.”5 Deposits like this compact, condense, and sink. McPhee calls the delta “a superhimalaya upside down.” The subsidence continues despite human intervention. Until about 1900, the Mississippi and its tributaries compensated for the subsidence with fresh sediment that came down each year. The delta accumulated unevenly but on the positive side of the geological cash register, as channels shifted and decaying vegetation sank into the flooded silts. The vegetation itself grew as a result of nutrients supplied by the Mississippi.

Before the days of flood defenses, the river spread across the surrounding country quite freely and in many places, except at low water, when it stayed within its natural banks. Today, over three thousand kilometers of levees constrain the river until Baptiste Collette Bayou, ninety-seven kilometers downstream of New Orleans. The delta has lost silt for a century and southern Louisiana is sinking. Meanwhile the river with its levees shoots fine river sediment out into the Gulf of Mexico—some 356,000 tons of it a day. The water rises ever higher behind the levees as the surrounding landscape continues to subside. McPhee calls the delta “an exaggerated Venice, two hundred miles wide—its rivers, its bayous, its artificial canals a trelliswork of water among subsiding lands.”6

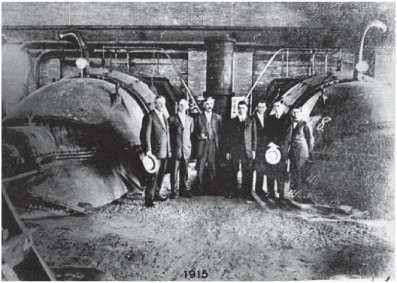

The entire delta is a highly vulnerable, threatened landscape. About half of New Orleans is as much as 4.6 meters below sea level, hedged in between Lake Pontchartrain and the Mississippi. The richest inhabitants live on the highest ground by the river. The poorest dwell at lower elevations in the most vulnerable locations of all. The city receives abundant rainfall, often torrential downpours that cause serious flooding within the river defenses, as happened with Tropical Storm Isaac in 2012. There are no natural outlets, so the water has to be pumped out, which tends to lower the water table and increase subsidence. The pumps, invented by engineer A. Baldwin Wood during the early twentieth century, allowed the city to expand to ever-lower elevations; there was no space elsewhere.7 New Orleans is so waterlogged that the dead are buried in cemeteries aboveground. Even from the slightly higher ground of the French Quarter, you look up at the levees and passing ships, their keels well above the city streets.

New Orleans has distinctive levee problems, not least that of the waves caused by the wakes of passing vessels. Everywhere, the high water line is rising as the speed of the confined water from upstream increases and the levees themselves subside. Down at the coast, the shortage of river silt has led to erosion, to the tune of some 130 square kilometers of marshland a year. Louisiana is 4 million square kilometers smaller than it was a century ago. Half a kilometer of marsh reduces the height of a storm surge from offshore by 2.5 centimeters. With the disappearance of 130 square kilometers of coastal barrier, the Mississippi equivalent of the Bangladeshi mangroves is drastically reduced. The vanishing marshes caused the corps to build an encircling levee around New Orleans, turning it into a fortified city—this before one figures in the sea level rises of the future.

At this point, many experts believe that the coast is beyond salvation, as entire parishes vanish and nutrient and sediment starvation wreak havoc on the coastal landscape. Today, much Mississippi water flows down the Atchafalaya, which is the main route by which severe floodwaters reach the Gulf. Morgan City, Louisiana, has a flood stage about 1.2 meters above sea level and lies directly in the flood’s path. Huge walls 6.7 meters high surround the small town, which must be one of the most vulnerable human settlements on earth.8 It is as if the city dwells atop an occasionally active volcano, its fate decided by flood control installations up at Old River, far upstream. This is apart from the storm surges caused by hurricanes. Weather conditions over 42 percent of the United States determine the long-term survival of Morgan City. Floods here last not weeks as they do upstream, but months, for the more people upstream protect themselves with rings of levees, the more water arrives downstream.

Figure 13.4 The dedication of A. Baldwin Wood’s pumping station in New Orleans, 1915. Author collection.

THANKS TO HUMAN activity, the Gulf Coast is sinking, sea levels are rising, and humans have effectively reversed nature. Or have they? This is hurricane country, and when such storms arrive they tear into the coast and accelerate erosion dramatically, making for an even more severe threat of destruction from the south than from the north.

Hurricanes entered recorded delta history dramatically in 1722, when one such storm led some French settlers of New Orleans to suggest that the city was uninhabitable. In 1779, another even more severe hurricane razed the city completely. A long history of devastation of barrier islands and inland villages also haunts the coast, but people have always stayed—to farm, to fish, and, in more recent times, because of oil. Rising sea levels compound the problem as they encroach on the eroding and subsiding delta shore. By the 1970s, the estimated annual loss was about a hundred square kilometers a year. The rate has slowed since then, as oil and gas activity has declined somewhat and measures were taken to reduce the loss, which now stands at somewhere between sixty-five and ninety square kilometers annually. Then there are sea surges, which created some seven hundred square kilometers of open water at the expense of wetland in the 2005 hurricane season alone.

In earlier times, before human interference, sediment maintained the elevation of the wetlands and fed the offshore barrier islands, many of which are now disappearing in the face of hurricanes and rising sea levels. Tidal gauge data for Louisiana record a sea level rise of nearly a meter over the past century, most of it caused not by global changes in ocean volume but by subsidence. If the local sea level were to rise 1.8 meters between now and 2100, all efforts to restore the wetlands would be canceled out and New Orleans would be seriously threatened. This is why Hurricane Katrina was a defining moment in the adversarial relationship between humans and the ocean.

Poverty Point may have been vulnerable to river floods, sea level shifts, and climate change, but its people could disperse into villages and resettle elsewhere. Today, millions of people live on the low-lying coastal plains of the Lower Mississippi region, where warming temperatures, rising sea levels, and a projected higher frequency of extreme weather events pose serious threats to much larger, far more vulnerable populations. When Katrina came ashore on the Gulf Coast in 2005, Americans received a harsh lesson in the frightening vulnerability of densely populated cities lurking behind flood defenses.

Hurricane Katrina was only a Category 1 Atlantic hurricane as it crossed southern Florida.9 It strengthened dramatically in the Gulf of Mexico before making landfall in southeastern Louisiana as a Category 3 on August 29, with sustained winds of 195 kilometers an hour. The storm lost hurricane strength only about 240 kilometers inland, near Meridian, Mississippi. Between 200 and 250 millimeters of rain fell in Louisiana as the hurricane swept inland. The sea surge was far more damaging than the wind and rain. The height was at least eight meters, inundating the parishes surrounding Lake Pontchartrain. When combined with levee breaches, the damage was catastrophic, with significant loss of life, quite apart from the devastation of coastal wetlands.

By August 31, 80 percent of New Orleans was underwater, in places 4.6 meters deep. A citywide evacuation order came into effect, at first voluntary, then mandatory, the first such evacuation in the city’s history, despite the ever-present threat of flood. By the time the hurricane came ashore, over a million people had fled New Orleans and its immediate suburbs. Nevertheless, over a hundred thousand remained, especially the elderly and poor. An estimated twenty thousand took refuge at the Louisiana Superdome, officially designated as a “place of last resort,” and designed to withstand very strong winds indeed. Flooding stranded many residents, many of them on rooftops or trapped in attics. There were bodies floating in the eastern streets; water was undrinkable; power outages were widespread.

The official death toll was nearly fifteen hundred people. As search-and-rescue operations intensified, looting and violence became epidemic through much of the city. Residents simply took food and other essentials from unstaffed grocery stories; armed robberies were commonplace. The authorities imposed a curfew, and then declared a state of emergency as sixty-five hundred National Guardsmen arrived to help restore order.

With flooding and chaos in the city, evacuation seemed a logical strategy. For years, coastal evacuation policies had assumed that most people could afford to leave their houses when ordered to do so and would be able to evacuate in their vehicles. The evacuees would seek shelter with relatives or stay in hotels or motels at higher elevations inland. Katrina proved the planners wrong. More than a quarter of New Orleans residents had no access to an automobile. They lived from one pay period to the next and had no surplus funds for evacuation or other emergencies. This was why many residents sought refuge at the Superdome and convention center. Hurricanes come ashore in this area relatively rarely, which means that generational memories fade quickly. Many people, who had forgotten the experience of Hurricanes Betsy (1965) and Camille (1969), preferred to stay and ride out the storm. Those who stayed were predominantly less educated, poor, and earning lower incomes. These were the people most affected by the disaster.

Most evacuees stayed within three hundred kilometers of New Orleans, but others dispersed all over the country, as far as California, Chicago, and New York. Orleans Parish had a population of 455,188 before the hurricane, and only 343,829 afterward, a drop of 24.5 percent.10 The hardest-hit parish, St. Bernard near Lake Pontchartrain, lost 45.6 percent of its people to out-migration. Over 250,000 Katrina migrants went to Houston. How many have returned is a matter of debate, for reliable statistics are hard to develop or come by. Many have chosen to relocate permanently.

One cannot entirely blame them, given the controversy and factionalism surrounding the recovery effort. One reformist faction wanted to use the storm as an excuse to remake New Orleans in a more efficient, modern form, including a replacement for the old public school system. Such a restoration would have required enormous sums of money from outside. New Orleans lacks a Coca-Cola or other large corporation to help pay the bill. Congress and the Bush administration did spend large sums on the city, but unfortunately they rejected proposals for a large-scale buyout of inundated housing as a basis for redeveloping the entire city. Instead, Washington gave billions in grants to individual homeowners, who wanted to return, and also for such projects as building schools, libraries, and water treatment plants. This was all fine and good, but the money was distributed inefficiently, much of it after very long delays. A patchwork of redevelopment made it nearly impossible for the poverty-stricken city government to provide basic services such as garbage collection, fire protection, and policing in a systematic manner.

All of these delays and often mistaken decisions tended to reinforce a widespread impression that no one outside the city cared about a poor, largely black population. There was even a sense among black community members that neither the Bush administration nor white New Orleans wanted blacks to return. As Nicholas Lemann wrote in the New York Review of Books, an ancient fear of black insurrection tended to resurface, accompanied by a longing for the city to be reborn as “another Charleston or Savannah, smaller, neater, safer, whiter, and relieved of the obligation to try to be a significant modern multicultural city.”11 This was, of course, merely a feeling and something that never even slightly surfaced as city policy.

Racial undercurrents of all kinds were at the heart of the toxic politics of rebuilding that emerged just as soon as the floodwaters receded. A Republican real estate developer assigned to the design of a comprehensive rebuilding program by the mayor, Ray Nagin, suggested that some of the most devastated, poorest, and lowest-lying areas of the city not be rebuilt immediately. Black outrage reached a fever pitch. Many out-migrants felt they were being deliberately excluded from their homes. The chasm between black and white widened even further. This debacle killed the mayor’s plan and meant that there was no blueprint at all. As recently as 2010, fifty thousand houses were still empty, more than a quarter of the available housing in the city. The current mayor, Mitch Landrieu, is moving cautiously. He is willing to tear the derelict houses down as part of a new policy that proclaims that every neighborhood will be rebuilt and that one cannot simply wait for displaced residents to return.

Meanwhile, the long-term consequences of the disaster continue. The city is much smaller, so population-based federal funds for housing, health care, and infrastructure are much reduced. Old political districts will be redrawn, resulting inevitably in less black representation at both the state and federal levels and a loss of political power. The permanent displacement of many poorer inhabitants has increased the percentage of educated, high-income residents. The redevelopment of low-income housing is glacially slow, causing some to question whether the recovery effort is equitable. By 2010, about 54 percent of the evacuees had returned to their pre-Katrina addresses. There are powerful reasons to stay away: the lack of affordable housing and a shortage of rental properties. Much recovery funding went to homeowners, who are in a minority among poorer citizens. With little money, few job opportunities, and a shortage of affordable housing, many refugees left permanently.

THE PLIGHT OF the Mississippi delta confirms that we have few options when confronted by extreme weather events made ever more dangerous by rising seas. Armoring cities and coasts with levees and seawalls is, at best, a costly gamble, even if twenty-first-century construction and technology provides ever more secure barriers. Even adopting building codes that allow for surging hurricanes and permit people to take shelter in their homes is an expensive hedge against catastrophic destruction. The only other option is carefully managed relocation at short notice. Katrina and other major storms teach us that the density of population in large twenty-first-century cities is such that our ability to relocate displaced residents either temporarily or permanently is severely limited. Inevitably, situations arise where those who can, leave and those who cannot, stay, fueling already festering economic and social inequities within and between segments of society. The resulting economic and political tensions within communities, between source and host communities, and, in the case of Bangladesh, between nations, do not augur well for a warmer future of higher sea levels and a great incidence of storm surges nurtured by extreme weather events.