On the morning of 12 April 1771, to a deafening fanfare of long-necked trumpets and the steady roll of camel-borne nagara drums, Shah Alam mounted his richly caparisoned elephant and set off through the vaulted sandstone gateway of the fort of Allahabad.

After an exile of more than twelve years, the Emperor was heading home. It was not going to be an easy journey. Shah Alam’s route would take him through provinces which had long thrown off Mughal authority and there was every reason to fear that his enemies could attempt to capture, co-opt or even assassinate him. Moreover, his ultimate destination, the burned-out Mughal capital of Delhi, was further being reduced to ruins by rival Afghan and Maratha armies.

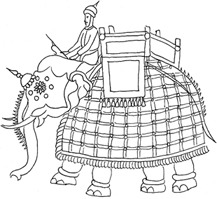

But the Emperor was not coming unprepared: following him were 16,000 of his newly raised troops and followers. A Mughal painting survives, showing the line of march: a long column of troops snakes in wide, serpentine meanders along the banks of the Yamuna, through a fertile landscape. At the front of the procession are the musicians. Then follow the macemen and the bearers of Mughal insignia – the imperial umbrellas, the golden mahi maratib fish standard, the face of a rayed sun and a Hand of Fatima, all raised on gilt staffs from which trail red silken streamers. Then comes the Emperor himself, high on his elephant and hedged around by a bodyguard armed with a thicket of spears.

The imperial princes are next, carried on a line of elephants with saffron headcloths, each embroidered with the Emperor’s insignia. They are followed by the many women of the imperial harem in their covered carriages; then the heavy siege guns, dragged by foursomes of elephants. Behind, the main body of the army stretches off as far as the eye can see. The different cohorts of troops are divided into distinct battalions of sepoy infantry, cavalry, artillery and the camel corps with their swivel guns, each led by an elephant-mounted officer sitting high in a domed howdah. The expedition processes along the banks of the river, escorted by gilded royal barges, and heads on through woods and meadows, past islands dotted with temples and small towns whose skylines are punctuated with minarets.1

The moment was recorded, for it marked what was recognised, even at the time, as a crucial turning point in the politics of eighteenth-century India. Shah Alam had now finally given up on the Company ever honouring its many promises to give him an army, or even just an armed escort, to help him reconquer his capital. If the Company would not help him then he would have to look for new allies – and this, by default, meant his ancestral enemies, the Marathas. But whatever the dangers, the Emperor was determined to gamble everything in the hope of regaining his rightful place on the Peacock Throne of his ancestors.2

When they belatedly learned of the Emperor’s plans, successive anxious Company officials in Calcutta wrote to Shah Alam that they ‘could not in any way countenance His Majesty’s impolitic enterprise’, and that they did not ‘think the present period opportune for so great and hazardous an undertaking, when disturbances are rife throughout the Empire’.3 ‘His Majesty should know that he has set himself a formidable task. If he regards the Marathas as friends he is greatly mistaken, since they are notoriously fickle and untrustworthy.’ ‘They will take pleasure in His Majesty’s distress and the object of their intended loyalty is only to get you into their clutches in order to use your name to reach their own ends.’4

Behind this apparently benign concern for the Emperor lay a deep anxiety on the part of the Company. Shah Alam’s announcement of his imminent departure had been entirely unexpected. Not only did the Emperor’s keepers want him in their own hands to legalise and legitimate whatever decisions they made, they also feared the consequences if others should seize him with the same intention. The Marathas were the Company’s most formidable rivals in India. They dominated almost the entire west coast of the subcontinent and much of the central interior, too. Too late, the Company was now contemplating ‘the additional influence it must give to the Marathas having the Emperor’s person in their hands, whose name will be made a sanction for their future depredations’.5

With a view to changing the Emperor’s mind, one of the highest ranking Company officers, General Barker, was despatched to Allahabad to try and reason with him. Even Shah Alam’s own senior advisers told him that he was ‘throwing away the substance to grasp at a shadow … and sacrificing his interests to the vain gratification of residing in the imperial palace’. They also warned him about the dangers of placing confidence in the Marathas, ‘the very people whose perfidious conduct and insatiable ambition had proved so fatal to many of your august family’.6

But Shah Alam had made up his mind. Barker found him ‘deaf to all arguments’.7 The Emperor even went as far as threatening suicide if there was any attempt by the Company to thwart him. He had long found life in Allahabad as a puppet of the Company insupportable, and now he yearned to return home, whatever the risks. ‘He sighed for the pleasures of the capital,’ wrote William Francklin, a Company official who knew him well and who eventually wrote his first biography.8

The Council ultimately realised it had little option but to accept the Emperor’s decision with the best grace possible: ‘It was not in our power to prevent this step of the King’s,’ they wrote to the directors in London in January 1771, ‘except by putting an absolute restraint on his person, which we judged would be as little approved by our Hon’ble masters, as it was repugnant to our own sentiments of Humanity.’9 Barker wrote to the Emperor: ‘since His Majesty has arranged all this with the Marathas secretly, the writer has received instructions neither to stand in the way of the royal resolution, nor to support it.’10

In fact, the Company had no one to blame but themselves for the Emperor’s dramatic decision. The discourteous treatment he had received from EIC officers in Allahabad since he arrived there six years earlier was the principal reason he had decided to hazard everything on the gamble of the Delhi expedition: ‘The English added to Shah Alam II’s misfortunes by treating him with an insulting lack of respect,’ wrote Jean-Baptiste Gentil, who had visited the Emperor in the Allahabad fort. ‘They did this repeatedly, in a setting – the palace of his forebear Akbar – which constantly brought to mind the former power and glory of the House of Timur.’

These insults at length compelled him to abandon what little remained to him of this once-opulent inheritance, and to go back to Delhi to live in the squalid huts hastily put up there for his return.

Worse, they [the Company] increased his misery by refusing to pay him the full 26 lakhs Rupees* that had been agreed under the Treaty of Allahabad of 1765.

A mere battalion-officer, of his own accord, arrested and imprisoned one of Shah Alam’s most senior liveried footmen. The Emperor duly requested the officer to release his servant, promising that in future his servant would be more careful, though the man had committed no offence deserving such treatment. Well, can you believe it? This officer immediately had the man brought out and horse-whipped in the presence of the Emperor’s messenger, saying: ‘This is how I punish anyone who fails to show me due respect!’

A short time after this, Brigadier Smith, who was staying in the imperial palace, forbade the Emperor’s musicians to sound the traditional naubat trumpet fanfare which is always played in a chamber above the gateway to the palace, saying that it woke him too early in the morning. The musicians having played in spite of the Brigadier’s orders, Smith sent guards to throw them and their instruments down from the upper chamber: luckily the musicians escaped in time, so it was only the instruments which were thrown down.

The uncouth and quarrelsome nature of this officer banished any peace of mind which the unfortunate Emperor might have enjoyed at Allahabad, till the humiliations inflicted on him daily compelled him, as said, to abandon his palace in Allahabad, to go and live on the banks of the Yamuna in Delhi, exchanging a rich and fertile province for a township of ruins.11

These thoughtless insults by junior officers only added to the bitterness Shah Alam already felt towards their superiors. He had good reason to feel betrayed. In the course of his many attempts to get the Company to honour its promises, one exchange in particular with Clive still rankled.

In 1766 Shah Alam had gone as far as sending an envoy to his fellow monarch George III, one sovereign to another, to appeal to him for help, ‘considering the sincerity of friendship and nobility of heart of my brother in England’. In his letter Shah Alam had offered to recognise the Hanoverian King’s overlordship in return for being installed in Delhi by Company troops. But the Emperor’s letters to the King had been intercepted by Clive, along with the nazr (ceremonial gift) of rare jewels worth Rs100,000,* and neither were ever delivered. Meanwhile, Shah Alam’s presents to the King were given on his return to London by Clive, as if from himself, without any mention of the Emperor. Shah Alam’s envoy did make it to Britain, and wrote a remarkable book about his travels, The Wonders of Vilayet, which revealed for the first time to an Indian audience the bleakness of the British winter and the quarrelsome nature of whisky-fuelled Scots; but the Company made sure he never succeeded in getting an audience with the King or near anyone in government.12

In December 1769, when Calcutta yet again refused to escort the Emperor to Delhi, this time allegedly ‘owing to the unsuitability of the time’, Shah Alam finally concluded that it was hopeless to rely on the Company: if he was ever to get to Delhi, he would have to do so protected by his own troops – and he would need to find new allies to convey him where he wished to go.13

Dramatic changes in the politics of Hindustan helped spur the Emperor into action. In the decade following the defeat of the Marathas at Panipat in 1761, and the death of 35,000 – an entire generation of Maratha warriors and leaders – the Afghans had had the upper hand in Hindustan from roughly 1761 until 1770.14 In 1762 Ahmad Shah Durrani had ousted Shah Alam’s teenage nemesis, Imad ul-Mulk, from the Red Fort, and installed as governor Najib ud-Daula, a Rohilla of Afghan birth. Najib had started his Indian career as a humble Yusufzai horse dealer but had steadily risen thanks to his skills both as a fighter and as a political strategist.

Najib was the ‘undefeated but not unchallenged master of Delhi for nine years’, who succeeded in ‘maintaining his position by a brilliant feat of poise and balance’, between a viper’s nest of contending forces.15 In October 1770, however, Najib died, and rumours reached Allahabad that his unruly son and successor, Zabita Khan, ‘had presumed to enter into the royal seraglio, to have connection with some of the ladies shut up in it. The king’s own sister was one of the number.’16 Mughal honour was now at stake, and the queen mother, Zeenat Mahal, wrote to her son to come immediately and take charge.

The main architect of the Afghan incursions into northern India, Ahmad Shah Durrani, had now returned to the mountains of his homeland to die. He was suffering the last stages of an illness that had long debilitated him, as his face was eaten away by what the Afghan sources call a ‘gangrenous ulcer’, possibly leprosy or some form of tumour. Soon after winning his greatest victory at Panipat, Ahmad Shah’s disease began consuming his nose, and a diamond-studded substitute was attached in its place. By 1772, maggots were dropping from the upper part of his putrefying nose into his mouth and his food as he ate. Having despaired of finding a cure, he took to his bed in the Toba hills, where he had gone to escape the summer heat of Kandahar.17 He was clearly no longer in any position to swoop down and assist his Rohilla kinsmen in India. The Afghans settled in India were now on their own.18

In May 1766, the Marathas launched their first, relatively modest, expedition north of the Chambal since Panipat five years earlier. By 1770, they were back again, this time with an ‘ocean-like army’ of 75,000, which they used to defeat the Jat Raja of Deeg and to raid deep into Rohilla territory east of Agra.19 It was becoming increasingly clear that the future lay once again with the Marathas, and that the days of Afghan domination were now over.

In contrast to the failing and retreating Durrani monarchy, the Marathas had produced two rival young leaders who had showed both the determination and the military ability to recover and expand Maratha fortunes in the north. The first of these was the young Mahadji Scindia. Of humble origins, Scindia had been chased from the battlefield of Panipat by an Afghan cavalryman who rode him down, wounded him below the knee with his battle axe, then left him to bleed to death. Scindia had crawled to safety to fight another day but he would limp badly from the wound for the rest of his life. Unable to take exercise, Scindia had grown immensely fat. He was, however, a brilliant politician, capable, canny and highly intelligent.20

His great rival, Tukoji Holkar, had also narrowly survived death on the plains of Panipat, but was a very different man. A dashing bon viveur, with a fondness for women and drink, but with little of his rival’s subtlety or intelligence, he and Scindia disagreed on most matters, and their nominal overlord, the Maratha Peshwa, had had to intervene repeatedly to warn the two rival warlords to stop squabbling and cooperate with each other. But both men did agree that this was the right moment to revive Maratha power in Hindustan, and that the best way of cementing this would be to install Shah Alam back in Delhi under their joint protection, and so secure control of his affairs.21 The master of Delhi, they knew, was always the master of Hindustan.

In late 1770 a secret message from Scindia reached Allahabad, offering Shah Alam Maratha protection if he were to return home. In response the Emperor discreetly sent an envoy to both Maratha leaders to explore the possibility of an alliance. Both rival camps responded positively and an understanding was reached. On 15 February 1771, an agreement was settled between the Marathas and Shah Alam’s son, the Crown Prince, who was in Delhi acting as Regent, that the Marathas would drive Zabita Khan and his Afghans out of Delhi, after which Scindia would escort Shah Alam to Delhi and hand over the palace to him. All this would be done in return for a payment by Shah Alam of Rs40 lakh.* The terms were secretly ratified by the Emperor on 22 March 1771.

By the middle of the summer, the Marathas had crossed the Yamuna in force and succeeded in capturing Delhi and expelling Zabita Khan’s garrison. They then forded the upper Ganges and headed deep into Rohilkhand, burning and plundering as they went. Zabita Khan retreated in front of them to Pathargarh, his impregnable fortress in the badlands north-east of Meerut. All the pieces were now in place.22

Only one final matter remained to be decided: the commander of Shah Alam’s new army. Here the Emperor had a rare stroke of luck. His choice fell on a man who would prove to be his greatest asset and most loyal servant. Mirza Najaf Khan had only recently entered Shah Alam’s service. He was the young Persian cavalry officer who had previously distinguished himself against the Company in the service of Mir Qasim.

Still in his mid-thirties, handsome, polished and charming, Najaf Khan had the blood of the royal Persian Safavid dynasty flowing in his veins and was allied through marriage with Nawab Shuja ud-Daula of Avadh. He was a refined diplomat, an able revenue manager and an even more accomplished soldier. He had carefully observed Company tactics and strategy while fighting with Mir Qasim, and learned the art of file-firing, modern European infantry manoeuvres and the finer points of artillery ballistics. The Company officers who met Najaf Khan were impressed: he was ‘high spirited and an active and valiant commander, and of courteous and obliging manners’, wrote William Francklin after meeting him. ‘By his unremitting attention to business, he preserved regularity, and restored order throughout every department.’ More unusually still for the times, he was ‘a humane and benevolent man’.23

Few believed Shah Alam had much of a chance of getting safely back to Delhi. Fewer still believed he had any hope of re-establishing Mughal rule there, or of achieving any meaningful independence from the Marathas, who clearly wished to use him for their own ends, just as the Company had done. But if anyone could help Shah Alam succeed on all these fronts, Najaf Khan was the man.

As the historian Shakir Khan commented, ‘A single courageous, decisive man with an intelligent grasp of strategy is better than a thousand ditherers.’24

Twenty miles on from Allahabad, the Emperor crossed into Avadh and that night arrived at Serai Alamchand. There, on 30 April, he was joined by Nawab Shuja ud-Daula.

The two had not come face to face since both had fled from the battlefield of Buxar seven years earlier. With Shuja came another veteran of that battle, the fearsome Naga commander, Anupgiri Gossain, now ennobled with the Persianate Mughal title, ‘Himmat Bahadur’ – or ‘Great of Courage’. Like everyone else, Shuja tried to dissuade Shah Alam from progressing to Delhi, but ‘finding that His Majesty was firm in his determination’ he agreed to lend the Emperor the services of Anupgiri, along with his force of 10,000 Gossain horse and foot, as well as five cannon, numerous bullock carts full of supplies, tents and Rs12 lakh* in money, ‘believing that if His Majesty joins the Marathas with insufficient troops he will be entirely in their hands’.25 But he declined to come with the Emperor and warned him that he saw the expedition ending badly.26

Shuja’s warnings continued to be echoed by General Barker. The general wrote to the Emperor: ‘the rains have now set in, and the Royal March, if continued, will end in disaster. So long as His Majesty stops at Kora [on the western edge of Avadh] the English troops will be at his service. If, which God forbid, His Majesty goes beyond the boundaries of Kora, and sustains a defeat, we will not hold ourselves responsible.’27

But the Emperor kept his nerve. He stayed nearly three weeks at Serai Alamchand, sequestered in his tent with Mirza Najaf Khan, ‘invisible to every person’, planning every detail of their march and working out together how to overcome the different obstacles. They secretly sent a trusted eunuch ahead with Rs2.5 lakh** in bags of gold to buy influence among the Maratha nobles. His mission was to discover which of the rival young Maratha leaders was more open to Shah Alam’s rule, and to begin negotiations about handing over the Red Fort back into Mughal hands.28

On 2 May, the Emperor packed up and headed westwards by a succession of slow marches until his army reached the last Company cantonment at Bithur, outside Kanpur. Here General Barker came and personally bade the Emperor farewell. He took with him all the British officers of Shah Alam’s army, but as a goodwill gesture left him with two battalions of Company sepoys and a gift of four field guns.29

The following week, Shah Alam’s army trudged in the heat past Kannauj and over the border into Rohilla territory. On 17 July, the monsoon broke in full force over the column, ‘and the very heavy rains which have fallen impeded his progress’ as the axles of his artillery foundered in the monsoon mud and the elephants waded slowly through roads that looked more like canals than turnpikes.30 Towards the end of August, the Emperor’s damp and bedraggled army finally reached Farrukhabad, dripping from the incessant rains. Here the Emperor faced his first real challenge.

The Rohilla Nawab of Farrukhabad, Ahmad Khan Bangash, had just died. Shah Alam decided to demonstrate his resolve by demanding that all the Nawab’s estates should now escheat to the crown, in the traditional Mughal manner. His demands were resisted by the Nawab’s grandson and successor, who gathered a Rohilla army, surrounded and cut off the Emperor’s column, and prepared to attack the imperial camp. Shah Alam sent urgent messages to Mahadji Scindia, requesting immediate military assistance. This was the moment of truth: would the Marathas honour their promise and become imperial protectors, or would they stand by and watch their new protégé be attacked by their Afghan enemies?

Two days later, just as the Rohillas were preparing for battle, several thousand of Scindia’s Marathas appeared over the horizon. The young Bangash Nawab saw that he was now outnumbered and appealed for peace, quickly agreeing to pay Shah Alam a peshkash (tribute) of Rs7 lakh* in return for imperial recognition of his inheritance. The Shah confirmed the young man in his estates, then moved with his winnings to Nabiganj, twenty miles from Farrukhabad, to spend the rest of the monsoon.31

On 18 November, Mahadji Scindia finally came in person to the imperial camp. He was led limping into the Emperor’s durbar by Prince Akbar, as everyone watched to see whether the Maratha chieftain would conform to Mughal court etiquette and offer full submission to the Emperor. After a moment’s hesitation, to the relief of the Mughals, Scindia prostrated himself before the Emperor, ‘laid his head at the Emperor’s feet, who raised him up, clasped him to his bosom and praised him. On account of his lameness, he was ordered to sit down in front of the Emperor’s gold chair.’32 Scindia then offered the Emperor nazars (ceremonial gifts), signifying obedience, after which the Emperor ‘graciously laid the hands of favor upon his back. After two hours he received leave of absence and returned to his Encampment.’33

Two days later, Scindia returned for a second visit, and the two leaders, the Mughal and the Maratha, worked out their plans and strategy. On 29 November, the newly confederated armies struck camp and together headed on towards Delhi.34

Shah Alam marched out from his camp near Sikandra on New Year’s Day 1772, and that evening, at Shahdara, on the eastern bank of the Yamuna, he finally came within sight of the domes and walls of his capital rising across the river. The Maratha garrison rode out to greet him, bringing with them Zeenat Mahal, the Empress Mother, the Crown Prince Jawan Bakht and ‘at least twenty-seven [of the Emperor’s other] children.’35 Shah Alam received them all in formal durbar.

Five days later, at quarter past eight in the morning, with his colours flying and drums beating, Shah Alam rode through the Delhi Gate into the ruins of Shahjahanabad. That day, the auspicious feast of Id ul-Fitr, marking the end of the holy fasting month of Ramadan, was remembered as his bazgasht, or homecoming.

This was the day on which he took his place in the palace of his fathers, ending twelve years in exile. The Mughals were back on the Peacock Throne.36

The mission before Shah Alam in January 1772 was now nothing less than to begin the reconquest of his lost empire – starting with the region around Delhi.

He and Mirza Najaf Khan had two immediate targets in sight: the Jat Raja of Deeg had usurped much of the territory immediately south of the capital, between Delhi and Agra. But more pressing than that was the need to bring to heel the rogue Rohilla leader Zabita Khan, who now stood accused of disobeying the Emperor’s summons, as well as dishonouring his sister. This was a matter which could not wait. Leaving his army camped outside the city across the river, Shah Alam spent just over a week in the capital, leading Id prayers at the Id Gah, paying respects at his father’s grave in Humayun’s Tomb, surveying what remained of his old haunts and visiting long-lost relatives. Then, on 16 January, he returned to his camp at Shahdara. The following morning, the 17th, he set off with Mirza Najaf Khan and Mahadji Scindia to attack Zabita Khan’s fortress.

The army first headed north towards the foothills of the Himalayas, then at Saharanpur swung eastwards. There they tried to find a ford across the Ganges at Chandighat, a day’s march downstream from Haridwar. Zabita Khan’s artillery guarded all the crossing places, and were entrenched on the far bank, firing canister over the river. But it was winter and the monsoon floods had long receded, while the spring Himalayan snowmelt had yet to begin. According to the Maratha newswriter who travelled with Shah Alam, an hour before sunrise, on 23 February, ‘The Emperor reached the bank of the Ganges and said with urgency, “If sovereignty be my lot, then yield a path.” Immediately, the river was found to be fordable, the water being deep only up to the knees and the lower half of the leg.’ The imperial army crossed the river and as dawn came up, engaged in fighting at close quarters, swords in hand. ‘Three miles to the right, Mahadji Scindia and his officers also crossed the river, then rode upstream and fell without warning on the Afghan rear.’37

The turning point came when Mirza Najaf Khan managed to get his camel cavalry onto an island halfway across the river, and from there they fired their heavy swivel guns at close quarters into the packed Afghan ranks on the far bank. One hour after sunrise, Zabita Khan gave up the fight and fled towards the shelter of the Himalayas. Several of his most senior officers were captured hiding in the reeds and rushes.38

The two armies, Mughal and Maratha, then closed in to besiege Zabita Khan’s great stone fortress at Pathargarh, where he had lodged his family and treasure for safety. The fortress was newly built and well stocked with provisions; it could potentially have resisted a siege for some time. But Najaf Khan knew his craft. ‘Najaf Khan closed the channel by which water comes from the river to this fort,’ reported the Maratha newswriter. ‘For four days cannon balls were fired by both sides like clouds of rain. At last one large bastion of the fort was breached. Immediately the garrison cried for quarter.’39 The Qiladar sent an envoy to Najaf Khan offering to capitulate if the lives and honour of the garrison were assured. He accepted the offer.

On 16 March, the gates of Pathargarh were thrown open: ‘The Marathas took their stand at the gate of the fort,’ recorded Khair ud-Din. ‘At first the poorer people came out; they were stripped and searched and let off almost naked. Seeing this, the rich people threw caskets full of gems and money down from the ramparts into the wet ditch to conceal them. Others swallowed their gold coins.’40

After this, the Marathas rushed in and began to carry away all the terrified Rohilla women and children to their tents, including those of Zabita Khan himself. All were robbed and many raped and dishonoured. In the chaos and bloodshed, the tomb of Zabita Khan’s father, Najib ud-Daula, was opened, plundered and his remains scattered. The Emperor and Najaf Khan intervened as best they could, and saved the immediate family of their adversary, whom they put under armed guard and sent on to Delhi. The families of other Afghans who wished to return to their mountains were marched back to Jalalabad under escort.41 Among those liberated were a number of Maratha women who had been captive since the Battle of Panipat, more than a decade earlier.42

For two weeks the besiegers sacked Pathargarh, digging up buried treasure and draining the moat to find the jewels which had been thrown into it. The booty, collected by Najib over the thirty years he was Governor of Delhi, was allegedly worth an enormous Rs150 lakhs,* and included horses, elephants, guns, gold and jewels.

Zabita Khan’s young son, Ghulam Qadir, was among the prisoners and hostages brought back to Shahjahanabad. There he was virtually adopted by the Emperor and brought up in style in the imperial gardens and palaces of Qudsia Bagh, north of Shahjahanabad. This was an act that Shah Alam would later come to regret. Even as his father continued to resist the Emperor and plot a series of rebellions against Shah Alam’s rule, Ghulam Qadir was given the luxurious life of an imperial prince, and grew up, in the words of one Mughal prince, to be as arrogant ‘as Pharaoh himself’.43 One senior noble, whose brother had been killed by Zabita Khan, asked the Emperor for Ghulam Qadir’s head in return, but Shah Alam protected the boy and insisted that no son should be responsible for the misdeeds of his father: ‘If his father committed such crimes why should this innocent child be killed?’ he asked. ‘If you are bent on vengeance, then seize Zabita Khan and kill him.’44

Maybe it was this that gave rise to gossip of a strange bond between the boy and the Emperor. Before long, however, there were rumours spreading in the palace that the Emperor’s affections for his young Rohilla protégé had crossed certain bounds. According to one gossipy Mughal princely memoir of the time, the Waqi’at-i Azfari, ‘when His Majesty beheld this ungrateful wretch in his royal gaze, he showed remarkable compassion’.

After bringing him gently and peacefully to Shahjahanabad and installing him in Qudsia Bagh, he appointed him guards and sent him large trays of assorted foods three times a day. The Shah frequently summoned him to the royal presence and would commiserate with him regarding his state, rubbing his blessed hand over the boy’s back out of pity, and insisting on his learning how to read and write. He gave him the imperial title Raushan ud-Daula and, when the boy was missing his parents and weeping, the Shah promised that he would soon be sent home. However, due to the political expediencies of the time, certain senior nobles at court did not want Ghulam Qadir to be released and sent to his father’s side. They prevented His Majesty from liberating the wretch.

At the time His Majesty greatly humoured Ghulam Qadir, allowing him intimate access, for he had designated his hostage as ‘my beloved son’. The author recalls several lines of rekhta [Urdu] poetry His Majesty recited at a garden banquet held in honour of Ghulam Qadir. One of these [playing on Shah Alam’s pen name of Aftab, the sun,] ran:

He is my special son, and the others mere slaves,

O God! Keep the house of my devotee ever inhabited.

May his garden of desire continue blossoming,

May Autumn never trespass amid his garden’s borders.

May he be reared in the shade of God’s shadow,

So long as Aftab (the sun) shines

And the heavenly stars sparkle in the sky.45

It may well be that there is no firm basis for this story, nor for Azfari’s homophobic joke that Ghulam Qadir suffered from ubnah – an itch in his arse. Homosexual relations were fairly acceptable between superiors and inferiors at this time and were not in themselves considered unusual or fodder for smutty jokes. Afzari’s joke lay in Ghulam Qadir being the ‘bottom’ (which established his inferiority) rather than the ‘top’, apparently an important distinction at the time. But some later sources go further. According to Najib-ul-Tawarikh, compiled one hundred years later in 1865, Ghulam Qadir was very handsome and the Emperor Shah Alam II sensed or suspected that females of the royal harem were taking interest in him. So one day the Emperor had his young favourite drugged into unconsciousness and had him castrated. There is a widespread tradition supporting this, but the many contemporary accounts do not mention it and there is some later talk of the Rohilla prince as being bearded, presumably not something that would have been possible had he actually been a eunuch.*

Nevertheless, if the young captive Ghulam Qadir did suffer from unwanted imperial affections in his gilded Mughal cage, which is quite possible, it would certainly help explain the extreme, psychotic violence which he inflicted on his captors when the tables were turned a few years later.46

The Delhi Shah Alam returned to at the end of his campaign against Zabita Khan bore little resemblance to the magnificent capital in which he had grown up. Thirty years of incessant warfare, conquest and plunder since 1739 had left the city ruined and depopulated.

One traveller described what it was like arriving at Delhi in this period: ‘As far as the eye can reach is one general scene of ruined buildings, long walls, vast arches, and parts of domes … It is impossible to contemplate the ruins of this grand and venerable city without feeling the deepest impressions of melancholy … They extend along the banks of the river, not less than fourteen miles … The great Masjid, built of red stone, is greatly gone to decay. Adjacent to it is the [Chandni] Chowk, now a ruin; even the fort itself, from its having frequently changed its masters in the course of the last seventy years, is going rapidly to desolation …’47

The Swiss adventurer Antoine Polier painted an equally bleak vision. Delhi, he wrote, was now a ‘heap of ruins and rubbish’. The mansions were dilapidated, the gorgeously carved balconies had been sawn up for firewood by the Rohillas; the canals in the Faiz Bazaar and Chandni Chowk were clogged and dry. ‘The only houses in good repair were those belonging to merchants or bankers,’ noted the Comte de Modave.48 A third of the city was completely wrecked. Polier blamed Zabita Khan’s father, Najib ud-Daula, who he said had ‘committed every kind of outrage in the city … the devastations and plunders of Nader Shah and Ahmad Shah Durrani were like violent tempests which carried everything before them but soon subsided; whereas the havoc made by the Rohillas over a decade resembled pestilential gales which keep up a continual agitation and destroy a country’.49

The great Urdu poet Mir returned to Delhi from exile around this time, full of hope that Delhi’s downward trajectory might have been arrested after so many years of ill fortune. On arrival he could not believe the scale of the devastation he found. He wandered in despair around the abandoned and despoiled streets, searching for his old haunts, looking in vain for something familiar: ‘What can I say about the rascally boys of the bazaar when there was no bazaar itself?’ he wrote. ‘The handsome young men had passed away, the pious old men had passed away. The palaces were in ruin, the streets were lost in rubble …’

Suddenly I found myself in the neighbourhood where I had lived – where I gathered friends and recited my verses; where I lived the life of love and cried many a night; where I fell in love with slim and tall beloveds and sang their praises. But now no familiar face came to sight so that I could spend some happy moments with them. Nor could I find someone suitable to speak to. The bazaar was a place of desolation. The further I went, the more bewildered I became. I could not recognize my neighbourhood or house … I stood there horrified.50

Here where the thorn grows, spreading over mounds of dust and ruins,

Those eyes of mine once saw gardens blooming in the spring.

Here in this city, where the dust drifts in deserted lanes

In days gone by a man might come and fill his lap with gold.

Only yesterday these eyes saw house after house,

Where now only ruined walls and doorways stands.

Sikhs, Marathas, thieves, pickpockets, beggars, kings, all prey on us

Happy he is who has no wealth, this is the one true wealth today.

The Age is not like the previous one, Mir,

The times have changed, the earth and sky have changed.

Tears flow like rivers from my weeping eyes.

My heart, like the city of Delhi, lies now in ruin.51

Nor was it clear that any sort of final peace had now come to the city. In the aftermath of the capture of Pathargarh, the fragile new alliance between the Mughals and the Marathas already appeared to be near collapse as the two sides fought over the division of the spoils: ‘the faithless Marathas have seized all the artillery and treasures of Zabita Khan, as well as his elephants, horses and other property,’ reported a palace newswriter, ‘and have offered only a worthless fraction to the Emperor.’52

The Marathas countered that the Emperor had still to pay them the Rs40 lakh he had promised them, by treaty, for restoring him to the throne. In response the Emperor could do little more than chide his allies for their faithlessness: ‘a harsh altercation broke out between him and the envoys of the Marathas, and the latter went away in anger.’ In the end Scindia handed over to the Emperor just Rs2 lakh* of the 150 he had allegedly taken from Zabita’s citadel. Shah Alam was rightly indignant: ‘For six months not a dam has been paid to my soldiers as salary,’ he said. ‘My men only get their food after three or four days of fasting.’53

The matter was still unresolved when the two armies returned to Delhi. By December 1772 things had escalated to such a pitch of hostility that on Friday the 17th there was a full-scale Maratha attack on Shah Alam’s small army, as his troops made a stand amid the ruins of the old fort of Purana Qila. During this skirmish, the newly recruited Breton adventurer René Madec, who had just been lured to Delhi by his friend Mirza Najaf Khan, took a bullet in the thigh. ‘The Emperor proposed coming to terms,’ wrote Madec in his Mémoire, ‘but the Marathas wanted to extract every possible advantage from having won the recent battle, so now they forced this unfortunate prince to dance to their tune.’

They were determined not to allow him to increase his military strength, which would soon enough have been a counterbalance to their own armed forces. All they wanted was to keep Shah Alam dependent on themselves. Their terms were that the Emperor would keep only such troops as he strictly needed as a personal guard … After this affair, the Emperor found himself reduced to a pitiable condition. He had failed to pay his troops before the battle, and was in even less of a position to pay them after. I could see that my troops were on the point of rebellion.54

Things could easily have turned out very badly for Shah Alam, but at the last minute he was saved. In early September 1773, an unexpected message arrived by express courier from Pune, announcing the premature death from consumption of the young Maratha Peshwa, Narayan Rao. A violent succession dispute quickly followed, pitting the many different factions in the Maratha Confederacy against each other. As news arrived in Delhi of the fight for control, both Scindia and his rival Holkar realised it was essential that they return south to Pune as fast as they could in order to secure their interests. In their hurry to get to Pune, they both departed within the week, leaving Shah Alam and Mirza Najaf Khan in complete, unmediated control of Delhi.

So it was that Shah Alam’s Delhi expedition ended in the one outcome no one had foreseen. The Marathas, having helped install Shah Alam back in power in Delhi, now withdrew for several years, while they battled among themselves. By the monsoon of 1773, Shah Alam found himself no longer the powerless puppet he had been for so much of his life, but the surprised sovereign of his own dominions, with one of the greatest generals of the eighteenth century as his commander.

Shah Alam was now forty-five, late middle age by Mughal standards. For all his mixed fortunes in battle, he could still look back on many aspects of his life with gratitude: he had successfully eluded assassination at the hands of Imad ul-Mulk, and had survived four pitched battles with the Company’s sepoys, only to have the victors swear him allegiance. He had made it back to Delhi and now occupied the Peacock Throne, independent within his kingdom and beholden to no one. This was for Shah Alam an almost miraculous outcome, and one that he had no hesitation attributing to divine intervention.

The Nadirat-i-Shahi, Diwan-e-Aftab is a collection of 700 examples of Shah Alam’s best poetry and songs, ranging from ghazals (lyric poems) to nayika bheda, verses that were compiled at his command in 1797. It opens with a ghazal of supplication to his Creator, written around this time, which shows the seriousness with which he took his royal duties, and the degree to which he believed his role to be heaven-appointed, and guarded over by God:

Lord! As You have bestowed by Your Grace, the Empire upon me

Render obedient to my word the realm of hearts and minds

In this world [alam] You have named me as King-of-the-World [Shah Alam]

Strike a coin in my name for the benefit of this world and the next

You have made me the sun [aftab] of the heaven of kingship

Illuminate the world with the light of my justice

At Your sacred court I am a beggar despite royal rank

Admit unto Your Presence this hapless supplicant

As You are the Most True and Supreme Judge, O God, I pray to You!

Let the justice of my rule breathe life into rock and desert

With Your help Moses prevailed over the tyrant Pharaoh

Your divine aid made Alexander king of the kingdom of Darius

As you have made shine in this world [alam] my name bright as the sun [aftab]

From the sun of my benevolence, fill with light the hearts of friend and foe

There were new conquests to be made during the next fighting season, but first there was the monsoon to be enjoyed and thanks to be given. As the Emperor told the Maratha commanders just before they left, he could not come with them on their campaigns as he needed to be in ‘Delhi for the marriage of my spiritual guide’s sons and the urs [festival] of my pir’, the great Sufi saint Qu’tb ud-Din Baktiar Khaki of Mehrauli.55 Shah Alam had last been to the shrine of his pir when he went to seek his blessing and protection before fleeing Delhi twelve years earlier. Now he wished to thank the saint for bringing him safely back.

He first summoned Mirza Najaf Khan, and in full durbar formally rewarded him for his services with the post of Paymaster General, and the gift of estates in Hansi and Hissar, to the west of the capital.56 He then decamped to the monsoon pleasure resort of Mehrauli, with its marble pavilions, swings, mango orchards and waterfalls, to celebrate his return in the traditional Mughal manner: with pilgrimages to Sufi shrines, music, songs, poetry recitations, fountains, feasting and love-making in the tented camps set up within the Mughal walled gardens of Mehrauli.

It was around this time that Shah Alam is thought to have written some of his most celebrated lyrics, a series of monsoon raags in the now lost musical mode of Raag Gaund, rain-tinged verses ‘celebrating the imminent moment of joyful union between the clouds and the earth, the lover and the beloved’.57 These were intended to be sung to celebrate the fecund beauty of the season, giving thanks to the patron saint of Mehrauli for his protection, and asking the saint for his blessing for what was to come:

The peafowl murmur atop the hills, while the frogs make noise as they gather

Turn your eyes to the beautiful waterfalls and spread the covering cloth fully!

I beg this of you, lord Qu’tb-ud Din, fulfil all the desires of my life

I worship you, please hear me, constantly touching your feet

Come on this beautiful day; take the air and delight in the garden,

Sate your thirst and take pleasure contemplating the beauties of Raag Gaund

Give riches and a country to Shah Alam, and fill his treasure house

As he strolls beneath the mango trees, gazing at the waterfalls.58

While Shah Alam relaxed and celebrated in Mehrauli, Najaf Khan was hard at work. He first secured the estates he had been granted in Hansi, and then used their revenues to pay his troops. He began to recruit and train further battalions, including one made up of destitute Rohillas, left penniless after the fall of Pathargarh, who were now driven by poverty to join the forces of their former enemies. As word spread of Shah Alam’s ambition to reconquer his ancestral empire, veterans from across India flocked to Delhi looking for employment in the Mirza’s new army.

Mirza Najaf was well aware that the new European military tactics that had already become well known in eastern and southern India were still largely unknown in Hindustan, where the old style of irregular cavalry warfare still ruled supreme; only the Jats had a few semi-trained battalions of sepoys. He therefore made a point of recruiting as many European mercenaries as he could to train up his troops. In the early 1770s, that meant attracting the French Free Lances who had been left unemployed and driven westwards by the succession of Company victories in Bengal, and their refusal to countenance the presence of any French mercenaries in the lands of their new ally, Avadh.59

Steadily, one by one, he pulled them in: first the Breton soldier of fortune René Madec; then Mir Qasim’s Alsatian assassin, Walter Reinhardt, now widely known as Sumru and married to a remarkable and forceful Kashmiri dancing girl, Farzana. The Begum Sumru, as she later became celebrated, had become the mother of Sumru’s son, and travelled across northern India with her mercenary husband; she would soon prove herself every bit as resilient and ruthless as he. While Sumru marched with Najaf Khan, the Begum pacified and settled the estates the couple had just been given by Shah Alam at Sardhana near Meerut.

Soon the pair created their own little kingdom in the Doab: when the Comte de Modave went to visit, he was astonished by its opulence. But Sumru, he noted, was not happy, and appeared to be haunted by the ghosts of those he had murdered: he had become ‘devout, superstitious and credulous like a good German. He fasts on all set [Catholic feast] days. He gives alms and pays for as many masses as he can get. He fears the devil as much as the English … Sometimes it seems he is disgusted by the life he leads, though this does not stop him keeping a numerous seraglio, far above his needs.’60 Nor did this stop him arming against human adversaries as well as demonic ones, and the Comte reported that of all the mercenary chiefs, Sumru ‘was the best equipped with munitions of war … His military camp is kept in perfect order … His artillery is in very good condition and he has about 1,200 Gujarati bulls in his park [to pull the guns.]’61

Then there was the Swiss adventurer Antoine Polier, a skilled military engineer, who had helped the Company rebuild Fort William in Calcutta after Siraj ud-Daula wrecked the old one. But he craved wilder frontiers and had found his way to Delhi, where he offered his military engineering skills and expertise in siege craft to Najaf Khan. Finally, there was also the suave and brilliant Comte de Modave himself, who, before bankruptcy propelled him eastwards, was a friend and aristocratic neighbour of Voltaire in Grenoble and a confidant of the French Foreign Minister, the Duc de Choiseul. Modave wrote and translated a number of books in the most elegant French, and his witty and observant memoirs of this period are by far the most sophisticated eyewitness account of the campaigns which followed.

A little later, the Mirza’s army was joined by a very different class of soldiers: the dreadlocked Nagas of Anupgiri Gossain. Anupgiri had just defected from the service of Shuja ud-Daula and arrived with 6,000 of his naked warriors and forty cannon. These Nagas were always brilliant shock troops, but they could be particularly effective against Hindu opponents. The Comte de Modave records an occasion when the Company sent a battalion to stop the Nagas ‘pillaging, robbing, massacring and causing havoc … [But] instead of charging the Nagas, the Hindu sepoys at once laid down their arms and prostrated themselves at the feet of these holy penitents – who did not wait to pick up the sepoys’ guns and carry on their way, raiding and robbing.’62

By August, under these veteran commanders, Najaf had gathered six battalions of sepoys armed with rockets and artillery, as well as a large Mughal cavalry force, perhaps 30,000 troops in all. With these the Mughals were ready to take back their empire.

Najaf Khan began his campaign of reconquest close to home. On 27 August 1773, he surprised and captured the northernmost outpost of Nawal Singh, the Jat Raja of Deeg. This was a large mud fort named Maidangarhi which the Jat ruler Surajmal had built, in deliberate defiance of imperial authority, just south of Mehrauli, and within sight of the Qu’tb Minar. ‘The rustic defenders fought long but at last could resist no longer. Najaf Khan captured the fort, and put to the sword all of the men found there.’ Najaf Khan then took several other small mud forts with which the Jat Raja had ringed the land south of Delhi.63

Nawal Singh sued for peace, while actively preparing for war and seeking an alliance with Zabita Khan Rohilla, who had recently returned to his devastated lands and was now thirsting for revenge. But Najaf Khan moved too quickly to allow any pact to be stitched together. His swift advance crushed the troops of Nawal Singh. On 24 September, he marched deep into Jat country and on the evening of 30 October at Barsana, just north of Deeg, with the sun sinking fast into fields of high millet, he killed and beheaded the principal Jat general and defeated his army, leaving 3,000 of them dead on the battlefield. The Jat sepoys tried to fire in volleys, but did not understand how to file-fire. Najaf Khan’s troops, who had worked out the rhythm of their loading and firing, fell to the ground during the volleys and then got up and rushed the Jat lines ‘with naked swords’ before they could reload. Najaf was himself wounded in the battle; but the immense plunder taken from the Jat camp paid for the rest of the campaign.64

As word spread of Najaf Khan’s military prowess, his enemies began to flee in advance of his arrival, enabling Najaf to take in quick succession the fort of Ballabgarh, halfway to Agra, as well as a series of smaller Jat forts at Kotvan and Farrukhnagar.65 By mid-December, Najaf Khan had laid siege to Akbar the Great’s fort at Agra. He left Polier to direct siegeworks, and then headed further south with half the army to seize the mighty fortress of Ramgarh, which he took by surprise, then renamed Aligarh.

On 8 February 1774, after Polier had fired more than 5,000 cannonballs at the walls of Agra Fort, he finally succeeded in making a breach. Shortly afterwards, the Fort surrendered and was handed over to Sumru and his brigade to garrison.66 Finally on 29 April 1776, after a siege of five months, the impregnable Jat stronghold of Deeg fell to Najaf Khan after the Raja fled and starvation had weakened the garrison. Madec records that three wives of Nawal Singh begged the palace eunuch to kill them after the capture of the city: ‘They lay on the carpet and he cut off the heads of all three of them, one after another, and ended by killing himself on their corpses.’67 The citadel was looted and the defenders put to the sword: ‘Much blood was spilt and even women and children had their throats cut,’ wrote the Comte de Modave. ‘Women were raped and three widows of the former Raja committed suicide rather than endure this fate. Then the pillagers set fire to the town. The fire spread to the powder store, and on three consecutive days there were terrible explosions. Najaf tried to stop the plundering, but it took him three days to bring his troops under control.’68

Shah Alam later censured Najaf Khan for the sack: ‘I have sent you to regulate the kingdom, not to plunder it,’ he wrote. ‘Don’t do it again. Release the men and women you have captured.’69

Nevertheless, in less than four years, Najaf Khan had reconquered all the most important strongholds of the Mughal heartlands and brought to heel the Emperor’s most unruly vassals. The Rohillas were crushed in 1772, again in 1774 and finally, in 1777, the Jats’ strongholds were all seized. By 1778, the Sikhs had been driven back into the Punjab, and Jaipur had offered submission. A token suzerainty had been re-established over both Avadh and parts of Rajputana.

The Mughal imperium was beginning to emerge from its coma after forty years of incessant defeats and losses. For the first time in four decades, Delhi was once again the capital of a small empire.

While Mirza Najaf Khan was busy with the army, Shah Alam stayed in Delhi, re-establishing his court and trying to breathe life back into his dead capital. Imperial patronage began to flow and the artists and writers started to return: as well as the poets Mir and Sauda, the three greatest painters of the age, Nidha Mal, Khairullah and Mihir Chand, all came back home from self-exile in Lucknow.70

Inevitably, as the court became established, the usual court intrigue began to unfold, much of it directed at Najaf Khan, who was not only an immigrant outsider, but also a Persian Shia. Shah Alam’s new Sunni minister, Abdul Ahad Khan, jealous of Najaf Khan’s growing power and popularity, tried to convince the Emperor that his commander was conspiring to dethrone him. He whispered in Shah Alam’s ears that Najaf Khan was plotting to join forces with his kinsman Shuja ud-Daula to found a new Shia dynasty which would replace the Mughals. ‘Abdul Ahad was Kashmiri, over 60 years old, but as nimble and energetic as a man in the prime of life,’ wrote the Comte de Modave. ‘He had been trained to the intrigues of court life since his earliest youth, his father having occupied a similar position for Muhammad Shah Rangila.’

On the surface, there could not be a more civil and decent person than this Abdul Ahad Khan, but all his political ambitions were nothing other than a tissue of disingenuous trickery, designed to extract money for himself, and to supplant anyone who gave him umbrage. He especially hated Najaf Khan, who was commanding the Emperor’s troops, which depended only on him, and who was therefore in control of his game. That meant that Najaf Khan was also feared and oddly un-loved by the Emperor himself.71

Najaf Khan shrugged off the gossip, carrying on with his conquests with an equanimity that impressed observers: ‘His perseverance is unparalleled,’ wrote Polier. ‘His patience and fortitude in bearing the reproaches and impertinence of this courtly rabble is admirable.’72 Modave agreed: ‘I have no words adequate to describe the phlegmatic poker-face which Najaf Khan kept up during all these intrigues directed against him,’ he wrote. ‘He was well-informed of their smallest details, and he would discuss them sardonically with his friends, frequently commenting that only the feeble fall back on such petty means.’

He never betrayed any sign of unease and carried on his campaign against the Jats regardless … He knew what power he could exercise in Delhi, and has often confided in one of his associates that he could, if he so wished, change matters in an instant, and send the Padshah back to the Princes’ Prison, and put another one on the throne. But that he was held back from having recourse to such violent methods by the fear of making himself hateful and hated. He preferred patiently to suffer the petty frustrations and humiliations thrown in his way, secure in the knowledge that, as long as he had a strong army, he had little to fear from his impotent rivals.73

Inevitably in such circumstances, between the Emperor and his most brilliant commander, a polite and courtly coldness developed which manifested itself in subtle ways that Modave took great pleasure in noting down: ‘It is a well-established custom in Delhi to send ready-cooked meals to the Emperor,’ he wrote, ‘to which the monarch responds by sending similar meals to those he wishes to honour.’

The dishes selected to be sent to the Emperor are placed on large platters, then covered with a cloth bag sealed with the seal of the sender, and these are sent into the royal seraglio. The Padshah had any dishes coming from Najaf Khan’s kitchen secretly thrown into the Yamuna; and when the compliment was returned, Najaf Khan would receive the royal gift with much ceremonious bowing, but, as soon as the royal servants carrying the meal had withdrawn, the cooked dishes were given to the halal-khwars, who cheerfully feasted on them – these latter fine fellows are in charge of cleaning the privies in people’s houses, so you can guess their status and function.74

Despite this, both Modave and Polier still found much to admire in Shah Alam. On 18 March 1773, soon after being taken into his service, Polier was formally received in the Diwan-i-Khas throne room by the Emperor. He was given fine living quarters in the haveli of Safdar Jung near the Kashmiri Gate, and presented with an elephant, a sword and a horse. The Emperor tied on his turban jewel himself, and he was sent food from the royal table. ‘Shah Alum is now about 50 years of age,’ Polier wrote in his diary soon afterwards, ‘of a strong frame and good constitution, his size above the middling and his aspect, though generally with a melancholy cast, has a good deal of sweetness and benignity in it, which cannot but interest the beholder in his favour.’

His deportment in public is grave and reserved, but on the occasion full of graciousness and condescension. Indulgent to his servants, easily satisfied with their services, he seldom finds fault with them, or takes notice of any neglect they may be guilty of. A fond father, he has the greatest affection for his children, whom yet he keeps agreeable to the usage of the court, under great subordination and restriction.

He is always strictly devout and an exact observer of the ceremonies of his religion, though it must be owned, not without a strong scent of superstition. He is well versed in the Persic and Arabic languages, particularly the former, and is not ignorant of some of the dialects of India, in which he often amuses himself composing verses and songs.

That he wants neither courage nor spirit has been often put to the proof, and he has more than once had severe trials of his constancy and fortitude, all of which he bore with a temper that did him infinite credit. But from the first, he reposed too implicit confidence in his ministers, and generally suffered his own better opinion to give way to that of a servant, often influenced by very different motives from those which such a confidence should have dictated.

This has always been Shah Alum’s foible, partly owing to indolence and partly to his unsuspecting mind, which prevents him from seeing any design in the flattery of a sycophant and makes him take for attachment to his person what is nothing more than a design to impose on him and obtain his confidence. Indeed two of the king’s greatest faults are his great fondness of flattery, and the too unreserved confidence he places on his ministers. Though he cannot be called a great king, he must be allowed to have many qualities that would entitle him, in private life, to the character of a good and benevolent man …75

The usually caustic Comte de Modave took a similar view of the Emperor. Modave thought him well-intentioned, gentle, courteous and lacking in neither wit nor wisdom. ‘He is good to the point of weakness,’ he wrote, ‘and his physical appearance and demeanour radiate intelligence and kindness. I have often had the honour of being in close proximity to him, and I was able to observe on his face those expressions of restlessness which reveal a prince immersed in deep thoughts.’

The Padshah seems to be a tenderly affectionate father, cuddling his little children in public. I was told in Delhi that he has 27 male children, all in riotous good health. When he appears in public, he is often accompanied by three or four of his sons. I have seen him ride out from the Palace-Fort to gallop in the surrounding countryside, accompanied by several of these young princes similarly mounted on horses, and displaying to their father their skill and prowess in various sports and games. At other times, I have seen him within the Palace Fort, passing from one apartment to another, with his youngest sons aged from 3 to 6 years old carried in his train – eunuchs were the bearers of these noble burdens.

Travel and adventure have broadened the mind of this prince, and his dealings with the French and the English have exposed him to a general knowledge of the affairs of the world, which might have helped guide him in the pursuit of his ambitions. But once back in Delhi, his affairs were in such a mess, and the temptations of lazy leisure so strong as to render all the good qualities of this prince ineffectual, at least up till now …

Though this prince has several good qualities – intelligence, gentleness, and a perceptive understanding – his occasional pettiness can ruin everything. Cossetted among his womenfolk, he lives out a flabby, effeminate existence. One of his daily pastimes is playing a board-game with his favourite concubines, with oblong dice about the length of the middle finger [chaupar] … Each game the Padshah plays with his ladies involves 3 or 4 paisas, which he pays if he loses and insists that he receive if he wins, according to the rules.

He has the failings of all weak rulers, and that is to hate those he is constrained to promote, which is the case with his general Najaf Khan – they both mistrust each other, and are continually falling out … Even though Shah Alam has taken part in war, he has never developed any taste for the military profession, even though the position he finds himself in would demand that he make fighting his principal occupation. One wastes one’s time trying to persuade him to go on campaign; since his return to Delhi, he has either avoided or refused all proposals made to him on that subject.

His minister [Abdul Ahad Khan] is so avid for authority and riches that he uses his influence on the spirit of Shah Alam for the sole purpose of distancing the prince from the servants who were truly loyal, and then replacing them with his own creatures. The irritation that this conduct inspired in all at court, particular in Najaf Khan, the most important amongst them, has occasioned cabals and intrigues … Jealous of his general [Najaf], and having little confidence in his ministers, who are without credit, Shah Alam always fears some petty revolution in the palace, which would put him back into the prison where he was born.76

But the most serious problem for the court was not internal divisions and intrigues so much as Shah Alam’s perennial lack of funds. On 9 September 1773, Shah Alam wrote to Warren Hastings asking for the tribute of Bengal. He said he had received no money from the Company ‘for the last two years and our distress is therefore very great now’. He reminded the Company of their treaty obligations – to remit revenue and to allow him the lands awarded to him at Kora and Allahabad.77

The appeal was unsuccessful. Hastings, appalled by the suffering of the Bengalis in the great famine, made up his mind to stop all payments to ‘this wretched King of shreds and patches’.78 ‘I am entrusted with the care and protection of the people of these provinces,’ he wrote, ‘and their condition, which is at this time on the edge of misery, would be ruined past remedy by draining the country of the little wealth which remains in it.’79 This did not, however, stop him from allowing his Company colleagues to remit much larger amounts of their savings back to England.

‘I think I may promise that no more payments will be made while he is in the hands of the Marathas,’ Hastings wrote to the directors a year later, ‘nor, if I can prevent it, ever more. Strange that … the wealth of the province (which is its blood) should be drained to supply the pageantry of a mock King, an idol of our own Creation! But how much more astonishing that we should still pay him the same dangerous homage whilst he is the tool of the only enemies we have in India, and who want but such aids to prosecute their designs even to our ruin.’80 When his colleagues on the Council pointed out that the Company only held its land through the Emperor’s charter, Hastings replied that he believed the Company held Bengal through ‘the natural charter’ of the sword. In 1774, Hastings finally made the formal decision to cease all payments to Shah Alam.81

The loss to Shah Alam’s treasury was severe, and it meant he could rarely pay his troops their full salary. As a Company report noted, ‘the expenses of his army are so greatly exceeding his Revenue that a considerable part of it remains for months together without any subsistence, except by Credit or Plunder. As a result, numerous Bodies of Troops are continually quitting his Service and others equally numerous engaging in it, as he indiscriminately receives all Adventurers.’82

All this was vaguely manageable while Najaf Khan was winning back the imperial demesne around Delhi and bringing back to the palace plunder from the Jats and the revenues of Hindustan. The real problems began when his health began to give way, and Najaf Khan retired, broken and exhausted, to his sickbed in Delhi.

Najaf Khan first became ill in the winter of 1775 and was confined to his bed for several months. While he was unwell, the Jats rose in revolt and it was not until he recovered in April that he was able to lead a second campaign to re-establish imperial authority in Hariana.

In November 1779, the scheming Kashmiri minister Abdul Ahad Khan finally lost the confidence of the Emperor when he led a catastrophic campaign against the Sikhs of Patiala. In the aftermath of this debacle, Shah Alam finally made Mirza Najaf Khan Regent, or Vakil-i-Mutlaq, in place of his rival. He was forty-two. It was a promotion the Emperor should have made years earlier: all observers were unanimous that the Mirza was by far the most capable of all the Mughal officials. But no sooner had Mirza Najaf Khan taken hold of the reins of government than he began to be troubled by long spells of fever and sickness. ‘The gates of felicity seemed to open for the people of these times,’ wrote one observer. ‘The citizens felt they were seeing promised happiness in the mirror. Yet [after Najaf Khan retired to his bed] the bugles and drums of marching troops approaching was like a poison dissolving thoughts.’83

Many were still jealous of the meteoric rise of this Shia immigrant, and to explain his marked absence from public life rumours were spread that Mirza Najaf Khan had become a slave to pleasure who was spending his days in bed with the dancing girls of Delhi. Khair ud-Din Illahabadi claims in the Ibratnama that the great Commander was led astray by a malevolent eunuch. ‘One Latafat Ali Khan tricked his way into Mirza Najaf’s confidence,’ he wrote, ‘and gained great influence over him.’

Under the guise of being his well-wisher, he shamelessly encouraged the Mirza, who till then had spent his time fighting and defeating enemies of the state, to taste the hitherto unknown pleasures of voluptuousness. Latafat Ali Khan was able to introduce into the Mirza’s own private quarters an experienced prostitute, who day and night had slept with a thousand different men. He now had her appear shamelessly at every intimate gathering, till the Mirza became infatuated with her, and little by little became her sexual slave. By this channel, Latafat Ali Khan was able to receive endless sums of money and gifts; but the wine and the woman quickly sapped the Mirza’s strength.

The Mirza spent all his time with this woman, worshipping her beauty, drinking wine to excess, his eyes enflamed and weakened, his body feverish and distempered, until he fell seriously ill. But he paid no attention to his health and carried on partying as long as he could manage it, ignoring doctors’ advice to moderate his behaviour. Finally, his illness reached a stage where it could no longer be cured or treated: the bitter waters of despair closed over his head and Heaven decreed he should die suddenly in the full flower of his manhood.84

Whatever may have been the particulars of Najaf Khan’s love life, the truth about his illness was far crueller. In reality, his time in bed was spent, not in sexual ecstasy, but in pain and suffering, spitting blood. The commander had contracted consumption. By August 1781 he was bedridden. He lingered for the first three months of 1782, gaunt and cadaverous, more dead than alive. ‘From the Emperor to the meanest inhabitant of Delhi, Hindus and Musalmans alike became anxious for the life of their beloved hero,’ wrote Khair ud-Din. ‘When human efforts failed they turned to the heavenly powers and prayed for his recovery. A grand offering (bhet) was made at the shrine of the goddess Kalka Devi [near Oklah] in the night of 7th Rabi on behalf of the Mirza, and the blessings of the deity were invoked for his restoration to health. The Nawab distributed sweets to Brahmans and little boys, and released cows meant for slaughter by paying their price in cash to the butchers with a strong injunction to the effect that none should molest these animals. But all this was in vain.’85 When the remorseful Emperor came to say goodbye at the beginning of April, Najaf Khan was ‘too weak to stand or to perform the customary salutations’:

On seeing the condition of the Mirza, His Majesty wept, and gently laid his hand on his shoulder to comfort him … Rumours of the Nawab’s imminent death spread throughout the city. His womenfolk left the private quarters and, weeping and wailing, crowded around his bedside, which brought a last flicker of consciousness to his face. Then he called for his sister, sighing with regret, ‘Sit by my pillow for a while, cast your merciful shadow on me, let me be your guest for a few moments’; and as he whispered this, he closed his eyes. They say one watch of the night was still left when the breath of life departed from his body’s clay.86

Mirza Najaf Khan died on 6 April 1782, aged only forty-six. For ten years he had worked against all the odds, and usually without thanks, to restore to Shah Alam the empire of his ancestors. Thereafter, as one historian put it, ‘The rays of hope for the recovery of the Mughal glory that had begun to shine were dissipated in the growing cloud of anarchy.’87 Najaf Khan was remembered as the last really powerful nobleman of the Mughal rule in India and was given the honorific title of Zul-Fiqaru’d-Daula (the Ultimate Discriminator of the Kingdom).88 He was buried in a modest tomb in a garden a short distance from that of Safdar Jung.* Like much of his life’s work, it was never completed.

Almost immediately, the court disintegrated into rival factions as Najaf Khan’s lieutenants scrambled for power. Afrasiyab Khan, Najaf Khan’s most capable officer and his own choice of successor, was the convert son of a Hindu tradesman, and was supported by Anupgiri Gossain and his battalions of warrior ascetics; but because of his humble background he had little backing in the court.

His rise was strongly opposed by Najaf’s grand-nephew, the urbanely aristocratic Mirza Muhammad Shafi, who organised a counter-coup on 10 September 1782, directing military operations from the top of the steps of the Jama Masjid. The two rival factions battled each other in the streets of Delhi, while outside the city the Sikhs, Jat and Rohillas all took the opportunity to rise as one in revolt. Shah Alam’s attempt to reconcile both sides with marriage alliances came to nothing.89 Within two years, both claimants had been assassinated and almost all of Mirza Najaf Khan’s territorial gains had been lost. For the first time, jokes began to be made about how the empire of Shah Alam ran from Delhi to Palam – Sultanat-i Shah Alam az Dilli ta Palam – a distance of barely ten miles.

The Maratha newswriter reported to Pune that ‘the city is again in a very ruinous condition. Day and night Gujars commit dacoity [violent robbery] and rob wayfarers. At night thieves break into houses and carry away shopkeepers and other rich people as captives for ransom. Nobody attempts to prevent these things.’90 Sikh war parties began once again to raid the northern suburbs. As Polier noted, the Sikhs ‘now set off after the rains and make excursions in bodies of 10,000 horses or more on their neighbours. They plunder all they can lay their hands on, and burn the towns.’91

Three successive failed monsoons, followed by a severe famine spreading across Hindustan, sweeping away around a fifth of the rural population, added to the sense of chaos and breakdown.92 In Lucknow at the same time, the Nawab Asaf ud-Daula built his great Imambara mourning hall in order to provide employment for 40,000 people as famine relief work; but Shah Alam did not have the resources for anything like this.93 The poet Sauda articulated in his letters the growing sense of despair: ‘The royal treasury is empty,’ he wrote. ‘Nothing comes in from the crown lands; the state of the office of salaries defies description.’

Soldiers, clerks, all alike are without employment. Documents authorising payment to the bearer are so much waste paper: the pharmacist tears them up to wrap his medicines in. Men who once held jagirs or posts paid from the royal treasury are looking for jobs as village watchmen. Their sword and shield have long since gone to the pawn shop, and when they next come out, it will be with a beggar’s staff and bowl. Words cannot describe how some of these once great ones live. Their wardrobe has ended up at the rag merchant …

Meanwhile, how can I describe the desolation of Delhi? There is no house from which the jackal’s cry cannot be heard. The mosques at evening are unlit and deserted, and only in one house in a hundred will you see a light burning. The lovely buildings, which once made the famished man forget his hunger, are in ruins now. In the once beautiful gardens, where the nightingale sang his love songs to the rose, the grass grows waist high around the fallen pillars and ruined arches.

In the villages round about, the young women no longer come to draw water at the wells and stand talking in the leafy shade of the trees. The villages around the city are deserted, the trees themselves are gone, and the well is full of corpses. Shahjahanabad, you never deserved this terrible fate, you were once vibrant with life and love and hope, like the heart of a young lover: you for whom men afloat upon the ocean of the world once set their course as to the promised shore, you from whose dust men came to gather pearls. Not even a lamp of clay now burns where once the chandelier blazed with light.

Those who once lived in great mansions, now eke out their lives among the ruins. Thousands of hearts, once full of hope, are sunk in despair. There is nothing to be said but this: we are living in the darkest of times.94

Unable to impose order on his court, and threatened by resurgent enemies on all sides, Shah Alam had no option but to reach out again to Mahadji Scindia, who had finally returned to Hindustan from the Deccan after an absence of eleven years: ‘You must undertake the Regency of my house,’ Shah Alam told him, ‘and regulate my Empire.’95 With the letter of supplication, he sent Scindia an Urdu couplet:

Having lost my kingdom and wealth, I am now in your hands,

Do Mahadji as you wish.96

In many ways Shah Alam made a canny decision when deciding to seek Mahadji Scindia’s protection for the second time. Scindia’s power had grown enormously since he left Delhi and headed south in 1772 to sort out affairs in the Deccan. He was now, along with Tipu, one of the two most powerful Indian commanders in the country. Moreover, his troops had just begun to be trained in the latest French military techniques by one of the greatest military figures of eighteenth-century India, Comte Benoît de Boigne, who would transform them beyond recognition. Before long they would be famed for their ‘wall of fire and iron’ which would wreak havoc on even the best-trained Indian armies sent against them.97

De Boigne was responsible for transferring to Scindia’s Marathas sophisticated new European military technology including cannon armed with the latest sighting and aiming systems with adjustable heights and elevating screws, and the introduction of iron rods to their muskets that allowed the best-trained troops to fire three shots a minute. When used by infantry deployed in a three-row pattern, his Maratha sepoys could keep up a continuous fire at the enemy, deploying an unprecedented killing power: according to one calculation, a squadron of cavalry breaking into a gallop 300 metres from one of de Boigne’s battalions would have to face around 3,000 bullets before they reached the sepoys’ bayonets.

A decade hence, when Scindia’s battalions were fully trained and reached their total strength, many would regard them as the most formidable army in India, and certainly the equal of that of the Company.98 Already, Scindia’s Rajput opponents were learning to surrender rather than attempt to defeat de Boigne’s new battalions, and Ajmer, Patan and Merta all gave up the fight after a brief bombardment rather than face the systematic slaughter of man and horse that de Boigne inevitably unleashed on his enemies. One commander even advised his wife from his deathbed, ‘Resist [Scindia] unless de Boigne comes. But if he comes, then surrender.’99

In November 1784, Scindia met Shah Alam at Kanua near Fatehpur Sikri. Scindia again prostrated himself, placing his head on the Emperor’s feet and paying him 101 gold mohurs, so taking up the office of Vakil-i-Mutlaq vacated by Mirza Najaf’s death. But as one British observer noted, ‘Scindia was [now] the nominal slave, but [in reality] the rigid master, of the unfortunate Shah Alam.’100

The Maratha general, after all, had his own priorities, and protecting the Emperor had never been one of them. Visitors reported the imperial family occasionally going hungry, as no provision had been made to supply them with food.101 When Scindia did visit, he gave insultingly cheap presents such as ‘sesame sweets usually given to slaves and horses’. He ordered the Delhi butchers to stop killing cows, without even consulting the Emperor.102 Finally, in January 1786, he took his forces off towards Jaipur in an attempt to raise funds and extend Maratha rule into Rajasthan, leaving the Red Fort unprotected but for a single battalion of troops under the command of Anupgiri Gossain.