THROUGH THE YEARS, I HAVE LEARNED THERE IS NO HARM IN CHARGING ONESELF UP WITH DELUSIONS BETWEEN MOMENTS OF VALID INSPIRATION.

STEVE MARTIN, BORN STANDING UP: A COMIC’S LIFE, 2007

When the US Army Air Corps set out to fly faster than the speed of sound, Col. Albert Boyd insisted that they proceed in small increments. They would make one flight of only a few minutes, then carefully monitor the results, make any adjustments, and push the envelope the next day by just a bit. Each flight was part of a sequence, in which the lessons from one step would be used to improve the next.

We have seen that great decisions come from understanding whether we can influence outcomes and whether performance is absolute or relative. Another important element, epitomized by Col. Boyd and his aviators, is learning and improving over time. It’s about gaining expertise, which is not the same as simply amassing experience.

Let’s start by looking at an activity that takes just a few seconds: shooting a free throw in basketball. Free throws are a good test of pure shooting skill. The task is the same for everyone: tossing a ball, nine and a half inches in diameter, through a rim eighteen inches wide, placed ten feet off the ground, from a distance of fifteen feet. That’s not exactly threading a needle, but it’s close. There isn’t a lot of margin for error. Furthermore, as when striking a golf ball, performance is entirely up to you. You’re not predicting what someone else will do; it’s up to you to throw the ball through the hoop.

During the 2011–2012 season, NBA teams attempted an average of 22.5 free throws per game. The Oklahoma City Thunder made 80.6 percent of its free throws, sinking 1,406 of 1,744 attempts. The Orlando Magic had the worst record, making only 66.0 percent, hitting just 995 of 1,508 shots. That’s a massive difference between the top team and the bottom, but of course the variance among individual players is even greater. Jamal Crawford of the Portland Trailblazers led the league, sinking 92.7 percent of his free throws, far more than the season’s most valuable player, LeBron James, at 77.1 percent, let alone the Magic’s Dwight Howard, who made only 49.1 percent from the free throw line.1 (Howard’s dismal performance was the main reason the Magic were the worst team. Without Howard, the rest of the Magic shot 76.3 percent, slightly better than the league average of 75.2 percent.) As good as Crawford shot, he was still shy of the best ever, Mark Price and Steve Nash, who both made 94 percent for their entire careers. That’s far better than the average, which has held steady since 1960 at about 74 percent for the NBA and 68 percent for college players.

It makes you wonder: What’s the secret to a good free throw?

To find out, a California-based venture capitalist and inventor (as well as former college basketball player and coach) named Alan Marty worked with Jerry Krause, head of research for the National Association of Basketball Coaches, and Tom Edwards, director for aerospace at the NASA Ames Research Center. They were, according to Marty, “the first group to systematically and scientifically confirm what makes great shooters, great.”2

After months of research, they determined that the best free throw has three features. First, it’s straight—neither to the left nor right but dead center. No surprise there. You don’t want to throw up a clunker that bounces off to one side or the other. Second, the best shot doesn’t aim for the exact center of the basket. The perfect spot is eleven inches past the front rim, about two inches beyond the midpoint. That gives a BRAD shot, the acronym for “Back Rim and Down.” Third, and very important, is the arc. The best shots are neither too high nor too flat, but leave the hands at an angle of 45 degrees.

Finding the best arc was the result of three methods. The researchers watched some of the best free throw shooters and mapped their trajectories, which revealed a consistent 45 degree arc. At the same time Edwards, the NASA scientist, modeled the physics of the free throw and determined the best shot had an arc in the mid-40 degrees. Finally, the team built an automated shooting machine and programmed it to throw over and over again in precise and replicable ways. They tried various arcs, from relatively flat shots to high looping shots, and found the best was 45 degrees. Three methods, all of which converged on a single answer.

So far, so good. Of course, it’s one thing to calculate the perfect arc, but something else to toss a basketball with exactly that arc, time after time. How do you consistently shoot the ball with a 45 degree arc and a depth of eleven inches past the rim?

The key is immediate feedback, so players can adjust their shots and try again, over and over, until they reach a level of accuracy and consistency. With this in mind, Marty and his team developed a system called Noah (named after the man who built the ark in the Book of Genesis), which links a computer with a camera and an automated voice. When a player releases a shot, the camera records the trajectory and the speaker immediately calls out the angle. Players can take a shot, make an adjustment, and take another, several times a minute. It doesn’t take long for the player to get a good feel for a 45 degree arc.

For both individuals and entire teams, Noah has yielded impressive results. One high school coach credited Noah with raising his team’s average from 58 to 74 percent. He explained: “This generation wants immediate feedback. They also want visual feedback and this system does both. It’s the video-game age now, so having a system available that generates immediate statistics is great.”

DELIBERATE PRACTICE AND HIGH PERFORMANCE

The principle behind Noah is deliberate practice. Not just lots of time spent practicing, but practice that conforms to a clear process of action, feedback, adjustment, and action again. Not simply experience, but expertise.

The original insights about deliberate practice go back more than two decades, to a study conducted by Benjamin Bloom, president of the American Educational Research Association. At the time, it was widely thought that high performers in many fields were blessed with native talent, sometimes called genius. But as Bloom studied the childhoods of 120 elite performers in fields from music to mathematics, he found otherwise.3 Success was mostly due to intensive practice, guided by committed teachers and supported by family members.

Since then a great deal of research has tried to uncover the drivers of high performance. Some of the most important work has been conducted by K. Anders Ericsson, professor of psychology at Florida State University. Ericsson is described by Steven Dubner and Steven Levitt, authors of Freakonomics, as the leading figure of the expert performance movement, “a loose coalition of scholars trying to answer an important and seemingly primordial question: When someone is very good at a given thing, what is it that actually makes him good?”4 In one of his first experiments more than thirty years ago, Ericsson asked people to listen to a series of random numbers, then repeat them. At first most people could repeat only a half dozen numbers, but with training they improved significantly. “With the first subject, after about 20 hours of training, his digit span had risen from 7 to 20,” Ericsson recalled. “He kept improving, and after about 200 hours of training he had risen to over 80 numbers.” Repeated practice led to a remarkable tenfold improvement.

The technique that worked for a seemingly meaningless task turned out to be effective for many useful ones as well. Ericsson studied activities ranging from playing musical instruments to solving puzzles to highly skilled activities like landing airplanes and performing surgery. Very consistently, subjects improved significantly when they received immediate and explicit feedback, then made adjustments before trying again.5

You won’t be surprised to learn that juggling, mentioned as a difficult task in Chapter Five, lends itself to deliberate practice. Very few people are able to juggle right away, but most of us can learn to juggle three balls with a bit of instruction and a good deal of deliberate practice. Golf, too, lends itself to deliberate practice. Anders Ericsson describes how a novice golfer, with steady practice, can fairly rapidly reach a level of competence, but after a while improvement tapers off. Additional rounds of golf don’t lead to further progress, and for a simple reason: in a game setting, every shot is a bit different. A golfer makes one shot and moves on to the next, without the benefit of feedback and with no chance for repetition. However, Ericsson observes: “If you were allowed to take five or ten shots from the exact location of the course, you would get more feedback on your technique and start to adjust your playing style to improve your control.”6 This is exactly what the pros do. In addition to hours on the driving range and the putting green, they play practice rounds in which they take multiple shots from the same location. That way, they can watch the flight of the ball, make adjustments, and try again. The best golfers don’t just practice a lot; they practice deliberately.

SHIFTING BACK AND FORTH

Previously we saw that when we can influence outcomes, positive thinking can boost performance. The concept of deliberate practice lets us refine that notion. Positive thinking is effective when it’s bracketed by objective feedback and adjustment.

The result is not simply optimism, but what the psychologist Martin Seligman calls learned optimism. The key is to replace a static view, which assumes a single mind-set at all times, with a dynamic view, which allows for the ability to shift between mind-sets. Before an activity, it’s important to be objective about our abilities and about the task at hand. After the activity, whether we have been successful or not, it’s once again important to be objective about our performance and to learn from feedback. Yet in the moment of action, a high degree of optimism—even when it may seem excessive—is essential. This is the notion expressed by comedian Steve Martin as he looked back on his career: that moments of deluded self-confidence can be useful, provided they are kept in check by valid assessments.

A related idea comes from Peter Gollwitzer, a psychologist at New York University, who distinguishes between a deliberative mind-set and an implemental mind-set. A deliberative mind-set suggests a detached and impartial attitude. We set aside emotions and focus on the facts. A deliberative mind-set is appropriate when we assess the feasibility of a project, plan a strategic initiative, or decide on an appropriate course of action.* By contrast, an implemental mind-set is about getting results. When we’re in an implemental mind-set, we look for ways to be successful. We set aside doubts and focus on achieving the desired performance. Here, positive thinking is essential. The deliberative mind-set is about open-mindedness and deciding what should be done; the implemental mind-set is about closed-mindedness and achieving our aims. Most crucial is the ability to shift between them.7

To test the impact of mind-sets, Gollwitzer and his colleague Ronald Kinney conducted an insightful experiment. One group of people was asked to list all the reasons they could think of, pro and con, regarding a particular course of action. The intention was to instill a deliberative mind-set. A second group was asked to list the specific steps they would take to successfully carry out a given course of action. The goal here was to instill an implemental mind-set. Next, all subjects took part in a routine laboratory task. Gollwitzer and Kinney found that subjects with an implemental mind-set showed significantly higher belief in their ability to control the outcome. They concluded: “After the decision to pursue a certain goal has been made, successful goal attainment requires that one focus on implemental issues. Accordingly, negative thoughts concerning the desirability and attainability of the chosen goal should be avoided, because they would only undermine the level of determination and obligation needed to adhere to goal pursuit.”8 An implemental mind-set, focusing on what it takes to get the job done and banishing doubts, improves the likelihood that you will succeed.

The question we often hear—how much optimism or confidence is good, and how much is too much—turns out to be incomplete. There’s no reason to imagine that optimism or confidence must remain steady over time. It’s better to ramp it up and down, emphasizing a high level of confidence during moments of implementation, but setting it aside to learn from feedback and find ways to do better.9

MIRACLE ON THE HUDSON: SHIFTING MIND-SETS ON THE FLIGHT DECK

An example of shifting between deliberative and implemental mind-sets comes from US Air Flight 1549, which landed safely on the Hudson River in January 2009, sparing the lives of all 155 people aboard.10

In the moments after the Airbus 320 took off from La Guardia Airport and struck a flock of geese, causing both engines to fail, Captain Chesley Sullenberger kept a deliberative mind-set. He coolly and systematically considered his options, including a return to La Guardia and an emergency landing at Teterboro Airport in New Jersey. Neither was possible. The aircraft had lost all power and wouldn’t be able to reach either airport. At this time, sober deliberation was required.

Once Sullenberger determined that the best course of action was to ditch in the Hudson, his focus shifted to implementation. All that mattered now was a successful landing. For that, he needed to muster a positive mind-set so that this landing—this one, right now—would be executed to perfection. In an interview with Katie Couric on 60 Minutes, Sullenberger described his attitude as the plane descended. “The water was coming up fast,” he recalled. Kouric asked if during those moments he thought about the passengers on board. Sullenberger replied: “Not specifically. I knew I had to solve this problem to find a way out of this box I found myself in.” He knew exactly what was needed: “I had to touch down the wings exactly level. I needed to touch down with the nose slightly up. I needed to touch down at a decent rate, that was survivable. And I needed to touch down at our minimum flying speed but not below it. And I needed to make all these things happen simultaneously.”

The time for deliberation had passed; now, success was all about implementation. Sullenberger stayed focused and kept his cool. At all times, he said, “I was sure I could do it.” His total focus on implementation helped achieve what was called “the most successful ditching in aviation history.” The Guild of Air Pilots and Air Navigators awarded the crew of Flight 1549 the Master’s Medal, the citation reading in part: “This emergency ditching and evacuation, with the loss of no lives, is a heroic and unique aviation achievement.” It’s also a prime example of shifting from one mind-set to another, gaining the benefits of deliberate thinking, but then shifting completely to implementation.

THE RIGHT STUFF AT AMEN CORNER

The need to shift mind-sets is clearly seen in golf—and not just once, as in landing a plane, but over and over. We have seen how golf is a game of confidence. As golfer Mark O’Meara said, you have to know the ball is going in. That’s true enough when you’re standing over the putt. But before a shot, a golfer needs to assess matters objectively and impartially. What’s the distance to the pin, the strength of the wind, and the length of the grass? Given all these factors, what shot should I play? Which club should I pick, the five-iron for greater distance or the six-iron for higher loft? These questions call for a deliberative mind-set, unaffected by wishful thinking.

Once the club is chosen and the golfer settles into his or her stance, the focus shifts. Now it’s all about executing this shot—this one shot—to perfection. An implemental mind-set is needed.

Next, once the golfer strikes the ball and watches its flight, the need for impartial observation returns. Am I playing long today, or are my shots falling short of their usual distance? Do I have my best game, or do I need to compensate in some way? The emphasis is on seeing things as they are, free from illusions or distortions. Moments later, when standing over the ball with club in hand, the implemental mind-set returns. Again the golfer must believe that this swing, this shot, will be perfect. I can—I will—make this shot exactly as I wish.11

And so it goes, back and forth between deliberation and implementation, perhaps seventy-two times—for a par golfer—in a few hours. No wonder the mental game is paramount. According to Bob Rotella, one of today’s most respected coaches: “To play golf as well as he can, a golfer has to focus his mind tightly on the shot he is playing now, in the present. A player can’t think about the shot he just hit, or the shot he played with the tournament on the line a week ago. That’s thinking about the past. He can’t think about how great it would be to win the tournament, or how terrible it would feel to blow it. That’s thinking about the future.”12

One of Rotella’s students is the Irish champion Padraig Harrington, a fine player but with the reputation of analyzing too much. At the Doral Open in March 2013, Rotella had Harrington wear a cap with electrodes to measure which areas of Harrington’s brain were most active as he played, the more analytical left brain or the more instinctive right side. Rotella said: “We want Padraig in the right brain. During a round, you shift back and forth but when he’s trying to swing, you definitely want him in that right side.”13 Another of Harrington’s coaches, Dave Alred, added: “One side of your brain lets you get on with stuff and the other side of your brain clutters what you are trying to do. That’s it in a nutshell. Golfers have to oscillate between the two sides, which is where it gets complicated.”14

Nowhere was the ability to shift between mind-sets illustrated as clearly as at the 2010 Masters. Coming into the final day of the tournament, Lee Westwood held a slim lead over Phil Mickelson, followed closely by Tiger Woods and K. J. Choi. Any of them was in position to win, with a few good shots and accurate putts. Performance was relative and payoffs were highly skewed, with the winner getting a payday of $1,350,000, compared to $810,000 for second place and $510,000 for third. A single stroke could be worth half a million dollars—as well as the fabled Green Jacket.

By the 8th hole, Mickelson and Westwood were tied at 12 under par. Then Mickelson nosed into the lead, taking a one-stroke advantage on the 9th hole, and held onto that barest of margins for the next three holes. Coming to the 13th hole, Mickelson had a two-stroke lead with only six holes left to play. Called Azalea, the 13th is one of the most difficult on the course, a 510-yard, par-five hole at the end of a demanding series of holes known as Amen Corner.

Clutching a driver, Mickelson came to the tee and powered the ball far and deep, but it veered off course and came to rest in the rough, lying in a patch of pine straw behind some trees. Still two hundred yards from the green, Mickelson faced a very difficult approach shot. Making matters worse, a tributary of Rae’s Creek fronted the green. Disaster loomed.

Most observers expected Mickelson to lay up—that is, to hit onto the fairway, and from there to make a safe approach shot over the creek and onto the green. He would very likely lose a stroke, and if Westwood birdied the 13th the Masters would be tied. But at least Mickelson would avoid a very risky shot through the trees, which could go badly wrong and cost several strokes, with little chance to recover.

Even his caddy advised him to take the safe route. But Phil Mickelson thought differently. Judging the line through the trees, he figured that a well-hit shot could split the trees and maybe even find the green.

Determining the best shot was a matter of deliberation: understanding his capabilities, assessing the competitive setting, and bearing in mind the holes yet to play. Then, having committed himself to attempt the risky shot, Mickelson’s mind shifted to implementation. As he later said: “I had to shut out everything around me. The fact that most people, most spectators, family friends, and even my caddy, wanted me to lay up. I had to focus on making a good golf swing because I knew if I executed that swing, the ball would fit between the trees, and end up on the green.”15

As the gallery watched in silence, Mickelson made a clean shot that threaded the ball between the pines, cleared the creek, bounced twice, and ended up just a few feet from the hole. It was a stunning shot, the stuff of legend. From there, his lead secure, Mickelson went on to win the 2010 Masters.16

An example of the right stuff? Absolutely. Once Mickelson made up his mind to go for the shot, he blocked out all distractions and summoned utter confidence. As he later put it, “I just felt like at that time, I needed to trust my swing and hit a shot. And it came off perfect.”17

Of course not all risky shots turn out so well. It’s easy to pick a memorable shot and infer, after the fact, that it was brilliant. (When asked the difference between a great shot and a smart shot, Mickelson gave a candid reply: “A great shot is when you pull it off. A smart shot is when you don’t have the guts to try it.”18) As are many instances of brilliance, it was shaped by careful analysis. In addition to a keen sense of the shot itself, Mickelson also understood the competitive situation. He wouldn’t have attempted such a shot on the first day of the Masters, or even on the second day. During the early rounds the main idea is to play well, to look for chances to make a birdie, but above all to avoid major errors. As the saying goes, you can’t win the tournament on Thursday, but you can lose it. Better to make a Type II error of omission than a Type I error of commission.

The final round, on Sunday, is a different matter. With just a few holes to play and victory within reach, a different calculus takes over. Phil Mickelson showed talent and guts, as well as a clear understanding of strategy.

THE LIMITS OF DELIBERATE PRACTICE

With so many examples of improved performance through deliberate practice, it’s tempting to conclude, as Ericsson puts it, that “outstanding performance is the product of years of deliberate practice and coaching, not of any innate talent or skill.”19 Others have made much the same argument. In recent years deliberate practice has been invoked as the key to high performance in books ranging from Talent Is Overrated, by Geoff Colvin, to Outliers, by Malcolm Gladwell.20 It’s mentioned prominently in Moonwalking with Einstein, in which science reporter Joshua Foer sought out Anders Ericsson for guidance in his (highly successful) quest to improve his memory.21 How can we increase our ability to recall information, whether the items on a shopping list, names of people we have met, or the exact sequence of fifty-two cards? The key is to practice deliberately. Set a specific goal, obtain rapid and accurate feedback, make adjustments, and then try again. And again.

No question, the message of deliberate practice is very encouraging. It appeals to our can-do spirit. We like to think that genius isn’t born. We like to believe that even Mozart had to practice long hours, and that Einstein’s success was the result of good teachers and hard work. It makes us feel good to imagine that Bobby Fischer wasn’t a creature from a different world, but got an early start and persisted. It makes us think there may be hope for us, too. If Joshua Foer went from a novice to national champion in one year, why not me?22

Yet we should be careful. Deliberate practice is hardly the cure-all that some would like to suggest.

First, there’s a growing body of evidence that talent matters—and a great deal. Researchers at Vanderbilt University found that children who performed very well on intelligence tests at a young age had a significant edge over others in later accomplishment. Very high intellectual ability really does confer an enormous real-world advantage for many demanding activities.23 Second, if we’re not careful, we can always pick examples after the fact, then look back and claim that extensive practice led to success. Among Gladwell’s examples in Outliers were The Beatles and Bill Gates, both chosen to illustrate the value of long hours of practice, whether playing music late into the night at clubs in Hamburg and Liverpool, or programming computers for hours on end while growing up in Seattle. Missing, however, are the legions of people who also practiced diligently but didn’t find the same success. (Psychologist Steven Pinker found Malcolm Gladwell’s approach particularly maddening: “The reasoning in Outliers, which consists of cherry-picked anecdotes, post-hoc sophistry and false dichotomies, had me gnawing on my Kindle.”)24

More important, deliberate practice is very well suited to some activities but much less to others. Look again at the examples we have seen: shooting a basket, memorizing a deck of cards, hitting a golf ball. Each action has a short duration, sometimes taking just a few seconds or maybe a few minutes. Each one produces immediate and tangible feedback. We can see right away whether the basketball went through the hoop, we got all fifty-two cards right, or the shot landed on the green. We can make modifications and then try again. Furthermore, each action was a matter of absolute performance. Even if a golf shot was made with an eye toward the competition, the shot itself—swinging a club to drive a ball onto the green and then into the hole—was a matter of absolute performance. Executing the task didn’t depend on anyone else.

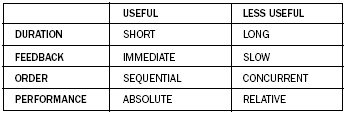

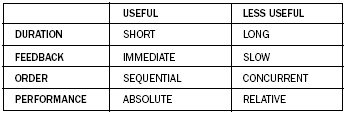

These sorts of tasks are described in the left column of Table 7.1. Duration is short, feedback is immediate and clear, the order is sequential, and performance is absolute. When these conditions hold, deliberate practice can be hugely powerful. As we relax each of them, the picture changes. Other tasks are long in duration, have feedback that is slow or incomplete, must be undertaken concurrently, and involve performance that is relative. None of this is meant to suggest their deliberate practice isn’t a valuable technique. But we have to know when it’s useful and when it’s not.

TABLE 7.1 WHEN IS DELIBERATE PRACTICE USEFUL?

To see how these differences can matter, consider the job of a sales representative. Imagine you’re a cosmetics salesperson, going door to door in your neighborhood. This sort of task is in the left column. The entire transaction is quick, taking maybe a few minutes. Feedback is immediate; you know right away if you made a sale or not. You finish one visit before going on to the next. Performance is absolute in the sense that you’re not directly competing with another offer. The logic of deliberate practice applies nicely. How you describe the products, how you present the options, the words you use and jokes you tell, and the way you try to close the sale—all of these can be practiced and refined, with feedback from one encounter applied to the next. The best salespeople approach each encounter as a new opportunity and do their best to project confidence and self-assurance. They can’t afford to be discouraged by the last rejection or worried about rejections to come. They have to believe that this customer, this call, this time can be successful—and muster positive thinking to help make it so. After each call, they can stand back and reflect. What did I do well, and what can I improve for next time? They shift rapidly from deliberation to implementation and back again.

For other kinds of sales representatives, the story is entirely different. Consider the sale of, say, a complex enterprise software system. The sales process—it’s a sales process, not a sales call—demands a deep understanding of the client’s needs and takes place over weeks and months. During that time, feedback is either uncertain or nonexistent. You might not know for several months if your efforts will bear fruit. Furthermore, because you’re working on many potential sales in parallel, you can’t easily incorporate the lessons from one client and apply them to the next. Your efforts are concurrent, not consecutive. And finally, for something like an enterprise software system, performance is better thought of as relative, not absolute, because the client is very likely talking with multiple vendors but will buy from only one. If nothing comes of your efforts, you may never know if it was because your sales presentation was poor, a rival’s products and services were better, or another sales rep was more effective. In this sort of setting, rapid and immediate feedback that can be applied right away is simply not possible.

DELIBERATE PRACTICE IN THE BUSINESS WORLD

In the business world, some decisions lend themselves nicely to deliberate practice, but others do not. Rapidly occurring and routine activities, including not only operations but many customer-facing encounters conform very well to the rigor of deliberate practice. That’s the essence of Kaizen, the system of continuous improvement at the heart of so many manufacturing techniques. There’s a disciplined sequence—plan, do, act, check. The cycle time is short and repeated over and over. Feedback is rapid and specific and can be applied to a next effort. Performance, whether gauged in quality or defects or some other operational measure, is absolute. It depends on you and no one else.

For other activities, the benefits of deliberate practice are less obvious. Examples go well beyond software sales. Consider the introduction of a new product. The entire process may take months or even years. By the time results are known, additional products will have been introduced. Furthermore, performance is at least partly relative. If a new product was unsuccessful, is that because we did a poor job, or did a rival introduce a better one?

Or consider setting up a foreign subsidiary. Years may elapse before we can assess whether we have been successful. Many factors are out of our control, including the actions of competitors as well as global economic forces. Was entry to a new market successful because of superior insights about customer needs, or mainly because of favorable economic conditions? Managerial decisions like these rarely afford us the luxury of trying once, receiving feedback, refining our technique, and trying again.

In Talent Is Overrated, Geoff Colvin offers an explanation of why two young men, Steve Ballmer and Jeff Immelt, office mates at Procter & Gamble in the late 1970s, became successful.25 Although they had graduated from excellent business schools, Stanford and Harvard, respectively, neither seemed much different from hundreds of other new hires at P&G. Twenty-five years later, however, they were hugely successful, Ballmer as the chief executive of Microsoft, taking over from Bill Gates, and Immelt as the chief executive of General Electric, where he succeeded Jack Welch. Colvin claims that Ballmer and Immelt owe their success to deliberate practice, and at first glance that seems plausible. If deliberate practice helps people improve at everything from hitting golf balls to landing airplanes, perhaps it’s an important element for executive success, too.

Certainly the message is very encouraging. It’s comforting and even inspiring to imagine that with diligence and deliberate practice, you too can become the chief executive of a major company. But Colvin’s claim is doubtful. To conclude that Steve Ballmer and Jeff Immelt were better at deliberate practice than their contemporaries, we would have to know who was in the next office and whether those people engaged in deliberate practice. Which of course we don’t. Even if we could compare them with their peers, the most important factors in career success are rarely the sorts of things that lend themselves to rapid and explicit feedback, followed by adjustment and a new effort. Much of Immelt’s success at GE had to do with the business division he ran, medical instruments, and decisions he made about product strategy and market development. As for Steve Ballmer, some of the most important factors in Microsoft’s success had to do with devising a propriety standard, MS-DOS, that was not controlled by IBM and could be sold to makers of PCs—so-called IBM clones. A shrewd move by Gates and Ballmer, no doubt, and one that showed enormous vision about the evolution of hardware and software, as well as a keen understanding about crucial points of leverage in a rapidly changing industry. But it’s not the sort of decision that lends itself to deliberate practice. You don’t have the opportunity to try, monitor the feedback, and try again.

Executive decisions aren’t like shooting baskets. In fact, as a general rule the more important the decision, the less opportunity there is for deliberate practice. We may wish it were otherwise, but there’s little evidence that in business, deliberate practice is “what really separates world-class performers from everybody else.”

Even Anders Ericsson misses this crucial distinction. In a 2007 article for Harvard Business Review, he writes: “[D]eliberate practice can be adapted to developing business and leadership expertise. The classic example is the case method taught by many business schools, which presents students with real-life situations that require action. Because the eventual outcomes of those situations are known, the students can immediately judge the merits of their proposed solutions. In this way, they can practice making decisions ten to twenty times a week.”26 This assertion is questionable. In business, eventual outcomes are rarely known with either the speed or clarity of, say, landing an airplane or striking a ball. Nor do students learning by the case method have the chance to make a decision and see how their actions would have played out. At best, they learn what another person did and get a sense of what followed (at least as described by the case writer, who very likely gathered facts and constructed a narrative with the eventual result in mind). The case method can be a very effective means of learning, and well-constructed cases can give rise to thoughtful discussions with powerful insights. But let’s not exaggerate. Most strategic decisions are very far removed from the logic of deliberate practice, in which rapid and precise feedback can be used to improve subsequent decisions. When we fail to make this distinction, we mislead our students and maybe even fool ourselves.

Ericsson recommends that managers and other professionals set aside some time each day to reflect on their actions and draw lessons. “While this may seem like a relatively small investment,” he notes, “it is two hours a day more than most executives and managers devote to building their skills, since the majority of their time is consumed by meetings and by day-to-day concerns. The difference adds up to some 700 or more hours more a year, or 7,000 hours more a decade. Think about what you could accomplish if you devoted two hours a day to deliberate practice.”27 I’m all for reflection and evaluation. Stepping back to ponder one’s actions and trying to draw lessons from experience is a good idea. But when feedback is slow and imprecise, and when performance is relative rather than absolute, we’re in a different domain. Although deliberate practice is ideal for some activities, it is much less appropriate for others.

THINKING ABOUT DECISIONS OVER TIME

Winning decisions call for more than identifying biases and finding ways to avoid them. As we have seen, we first need to know whether we’re making a decision about something we can or cannot directly control. We also need to understand whether performance is absolute or relative.

In this chapter we have added the temporal dimension. We need to ask: Are we making one decision in a sequence, where the outcome of one can help us make adjustments and improve the next? If so, the logic of deliberate practice works well. We can oscillate between deliberative and implemental mind-sets. For many activities, especially those that offer rapid and concrete feedback, and for which performance is absolute, the benefits of deliberate practice can be immense.

Yet many decisions do not lend themselves to deliberate practice, and it’s crucial to know the difference. The opening example of Skanska USA Building and its bid for the UDC is a case in point. The bidding process alone took months, and the actual construction would take years to complete. Precise lessons would be hard to distill and difficult to apply to a next project, which would be different from the UDC in many respects. Plus, bidding against four other companies added a competitive dimension, so that performance was relative. As much as Bill Flemming would have loved to derive the benefits of deliberate practice, and whereas he surely used his accumulated experience to help make a smart bid, a large and complex decision like the UDC bid demanded a different approach.

Wise decision makers know that for sequential decisions that provide clear feedback, we can err on the side of taking action, monitoring results, and then make adjustments and try again. When circumstances are different—when decisions are large, complex, and difficult to reverse—a different logic applies. Now the premium is on getting this decision right. Rather than err on the side of taking action that may be wrong but that can be rapidly corrected, we may prefer to err on the side of caution and avoid a mistake with potentially devastating long-term consequences.

![]()

* A point on terminology: Deliberate practice calls for the shift back and forth between a deliberative mind-set and an implemental mind-set.