THE ONLY WAY TO MAKE PROGRESS IN BUSINESS IS THROUGH CHANGE. AND CHANGE, BY DEFINITION, HAS A CERTAIN AMOUNT OF RISK ATTACHED TO IT. BUT IF YOU PICK YOUR SHOTS, USE YOUR HEAD, AND APPLY GOOD MANAGEMENT, THOSE ROLLS OF THE DICE CAN TURN OUT PRETTY GOOD.

ED WHITACRE, AMERICAN TURNAROUND: REINVENTING AT&T AND GM AND THE WAY WE DO BUSINESS IN AMERICA, 2013

Experiments offer a powerful way to isolate a single phenomenon while holding other things constant. Many real-world decisions, however, don’t oblige our wish to deal with one element at a time. They confront us with many elements, interlinked and interdependent. They often combine an ability to control outcomes with a need to outperform rivals, they often unfold over months and years, and they involve leaders in an organizational setting.

In these next two chapters I’ll look at two very different kinds of leadership decisions: making a high-stakes competitive bid and starting a new venture. In both instances, we’ll see how a careful analysis and deliberation—left brain—is essential, but that winning decisions also call for moments of calculated risk—right stuff.

A GOOD PLACE TO LOSE YOUR SHIRT

Competitive bids have been a frequent topic of study in decision research, with much attention paid to the winner’s curse. The winner’s curse appeared briefly in Chapter One, when Skanska USA Building was trying to determine how much to bid for the Utah Data Center. An aggressive bid was surely needed, but a danger loomed: if Skanska made a very low bid in order to win, it would very likely end up losing money. As we will see, the standard lessons about the winner’s curse make sense for some kinds of competitive bids, but aren’t appropriate for others.

The story of the winner’s curse goes back to the 1960s, when managers at the Atlantic Refining Company noticed a worrying trend. Some years earlier, Atlantic (later known as Atlantic Richfield and then ARCO) had won several auctions to drill for oil in the Gulf of Mexico. Later, as the company reviewed the performance of those leases, it found that it was losing huge sums of money. Oil had been discovered, yes, but revenues weren’t enough to make the leases profitable. Winning bids had turned into losing investments.

A few members of Atlantic’s R&D department decided to take a closer look. Ed Capen, a research geophysicist, found that Atlantic wasn’t alone. Virtually every company that acquired oil fields in the Gulf of Mexico through public auctions ended up losing money. Since 1950, investing in Gulf of Mexico oil fields had “paid off at something less than the local credit union.”1 Competitive bidding, Capen concluded, “is a good place to lose your shirt.”2

To get at the root of the problem, Capen looked at the auction process itself. He discovered an insidious dynamic: when a large number of bidders place secret bids, it’s almost inevitable that the winning bid will be too high. Capen called this the winner’s curse.

From there the story gets even more interesting. Once Atlantic understood the danger of overbidding, it took precautionary steps. Each department was instructed to become more conservative. Geophysicists were told to be more cautious when estimating the size of oil deposits. Geologists were directed to assume a lower rate of drilling success. Accountants were instructed to raise the discount rate, which lowered the net present value of future revenue streams and made fewer projects appear attractive. Every one of these measures seemed reasonable, but together they had an unanticipated effect. Ed Capen recalled, “By the time everyone was through subtracting value, our bids were so low we didn’t buy anything.”3 Now Atlantic had a different problem: it had found a way to avoid losses from overbidding, but also precluded the possibility of any wins.*

Working with two colleagues, Bob Clapp and Bill Campbell, Ed Capen designed a Monte Carlo model to simulate bidding among many parties. Eventually they devised a method aimed at limiting losses while providing a reasonable chance of success over the long run. Capen and his colleagues set out three rules: The larger the number of bidders, the lower you should bid. The less information you have relative to the information possessed by rival bidders, the lower you should bid. And the less certain you are about your information, the lower you should bid. When more than one condition is present, it’s even more important to reduce your bid; when all three are present, be extra careful. In those cases, Atlantic’s rule of thumb was to make its best estimate of the value of the lease, then bid only 30 percent of that amount. Granted, this approach would lead to fewer wins, but any purchase would be at a price that would give the company a good chance of earning a profit. It was a practical way to mitigate the dangers of competitive bidding.

Capen and his colleagues were modest about their method. The complexities of competitive bidding remained daunting: “So what is the best bid strategy? We cannot tell you and will not even try. The only thing we can do is show you one approach to the mathematical modeling of competitive sales. . . . The bidding model gives us a bid that we can make with confidence, and be happy with when we win. Yes, we may have overestimated value. But we have bid lower than our value estimate—hedging against expected error. In a probability sense, we ‘guarantee’ that we obtain the rate of return we want.”4 In 1971, Capen, Clapp, and Campbell published their findings in a seminal article, “Competitive Bidding in High-Risk Situations,” in the Journal of Petroleum Technology. It remains a classic to this day.5

COUNTING NICKELS IN A JAR

In the following years, the winner’s curse was studied in a variety of experiments. In one, Max Bazerman and William Samuelson filled a large glass jar with nickels, then asked a group of students to come close and take a good look, so they could inspect the jar from various angles. Unbeknownst to the students, the jar contained 160 nickels, worth $8. Each student then made a sealed bid, stating how much he or she was willing to pay for the contents of the jar, with the highest bid winning the nickels.

Some students’ estimates were high, many were low, and a few were very accurate. Overall the average of their bids was $5.01, a good deal lower than the true value of the nickels. Most students were cautious and tended to underbid, which isn’t surprising because people are often risk averse, and in this experiment there was nothing to be gained by erring on the high side. But in every auction, some people bid well above the correct figure. Over the course of several auctions, those high bids had a mean of $10.01, which meant that on average the winner paid 25 percent more than the contents were worth.

This simple demonstration had all the virtues of laboratory experiments. It was easy to do: just assemble the students and show them the jar, invite them to place their bids, and calculate the result. The entire process took just a few minutes. Other versions used a variety of different items, including things like paper clips, but the results were the same. The larger the number of bidders, the greater the chance that at least one bid would be wildly high, and the less likely it was that an accurate bid could hope to win. Bazerman and Samuelson published their findings in an article with a title that made the point nicely: “I Won the Auction but I Don’t Want the Prize.”6

Today, winner’s curse has entered the general lexicon. It’s often mentioned when questions are raised about an ambitious bid. It’s not a cognitive bias, because it doesn’t arise from an error of cognition. Rather, it stems from the bidding process itself. Bring together enough people—even people who are somewhat conservative in their bids—and it’s very likely that at least one will bid too much. Richard Thaler described the winner’s curse as “a prototype for the kind of problem that is amenable to investigation using behavioral economics, a combination of cognitive psychology and microeconomics.”7 So well did the term capture the essence of behavioral economics that Thaler used it for the title of a 1992 book, The Winner’s Curse: Paradoxes and Anomalies of Economic Life.

AUCTIONS, PUBLIC AND PRIVATE VALUE

Of course it’s good to be aware of the winner’s curse. Anyone thinking of taking part in an auction should understand the basic paradox that the apparent winner often ends up a loser. You don’t want to be drawn into a bidding war for some item on eBay when you can find it somewhere else and perhaps more cheaply. The winner’s curse is particularly important in the world of finance, where it poses a serious danger for investors in publicly traded assets. Because market analysts and investors have access to roughly the same information, anyone willing to pay more than the market price is very likely paying too much. The implication is sobering. Imagine you spot what seems like a bargain—a stock that you think can be bought on the cheap, for example. Rather than believe you know something that others don’t, it’s wiser to conclude that you’re wrong.8 Much more likely is that your generous valuation is in error. Seminars on behavioral finance teach investors to watch out for the winner’s curse and to avoid its ill effects.9

But let’s stand back for a moment. What do a nickel auction and buying a stock have in common? By now, I hope you have spotted the answer. In both cases, there’s no way to exert control over the value of the asset.

Both are examples of a common value auction, meaning that the item on offer has the same value for all bidders.10 The jar contains the same number of nickels for everyone; not even the most eagle-eyed buyer can find an extra nickel hiding somewhere in the contours of the jar. Further, a nickel has the same value to everyone. You cannot, through skill or persistence or positive thinking, go into a store and buy more with a nickel than I can. The same goes for a financial asset, like a share of Apple or General Electric. It’s worth the same for you and for me. You can decide to buy a share, or you can decide not to buy and spend your money elsewhere, but you won’t have any effect on its value.

In common value auctions, our bids reflect our estimates of the asset’s value. If you think the jar contains more nickels than I think it does, you’ll bid more than I will, simple as that. The same goes for a share of stock. For these sorts of assets, there’s nothing to be gained from anything other than careful and dispassionate assessment.

There’s another reason you don’t want to overpay. If you need nickels you can always go to a bank and buy a roll of 40 for $2. There’s no reason to pay more. You wouldn’t worry about losing a nickel auction—or making a Type II error. Rather, you should worry about making a Type I error—winning the bid and realizing you have overpaid. The same is true for a share of Apple or GE. There’s a ready market with plenty of liquidity, and unless you’re planning to mount a takeover bid and want to accumulate a large block of shares, you can buy as many as you want without moving the market. Paying more than the market price makes no sense.

Other auctions are very different. They’re known as private value auctions, in which the value for you and for me is not the same. Differences might be due to entirely subjective reasons, as with a collectible. What would you be willing to pay for John Lennon’s handwritten lyrics to “A Day in the Life”? They were sold at Sotheby’s in New York for $1.2 million after a vigorous bidding war among three parties, each of whom placed a high personal value on a small piece of paper.11 In other cases the difference in value is for commercial reasons, such as different abilities to generate revenues or profits from the asset. Here again, what bidders are willing to pay may differ sharply. Offering more than others isn’t necessarily wrong, but should reflect a sound understanding of the value of that asset today—and what it can earn tomorrow. Paying more than other bidders might make good sense, provided you can explain your rationale.

DRILLING FOR DOLLARS

Let’s return to bidding for oil tracts. It’s not a common value auction, and it doesn’t take place in a few minutes, but rather unfolds over years. Determining the amount to bid is much more complicated than at a nickel auction.

If you saw the 2007 movie There Will Be Blood, you might think that drilling for oil is a bit like drinking a milkshake—you sink a straw and drain it dry. A few wells might be something like that. The famous 1901 Spindletop gusher near Beaumont, Texas, comes to mind; the oil was so close to the surface that even before the well was tapped, fumes were wafting up through the soil. Today, of course, oil exploration takes place in much more demanding settings. Drilling was already complex when Atlantic was drilling in the Gulf of Mexico back in the 1950s, and it’s much more challenging now. Some of the complexities became apparent to the general public in a dramatic fashion in 2010, with the explosion and spill at BP’s Deepwater Horizon platform.

The cost of developing new oil fields continues to rise because of the challenges of working in more and more remote locations, but if we hold constant the level of difficulty, the cost of producing oil has declined on a per-barrel basis. That’s because there have been major improvements at every step of the process. Let’s start with exploration. Oil companies now have much better seismic imaging technology and more powerful software to interpret the data they gather. In the 1970s two-dimensional imaging was the state of the art. By the 1980s more oil could be located thanks to three-dimensional imaging along with better algorithms to analyze data. Then came four-dimensional imaging, with the fourth dimension of time. By comparing images taken at regular intervals, exploration companies could monitor how extraction causes the remaining oil to shift, allowing them to position subsequent wells with even greater precision. Companies are also more efficient at drilling. Drill bits are made of increasingly durable materials that are less likely to break, and wells no longer have to be vertical but can be drilled at any angle, including horizontal. Oil companies are also better at extraction, using techniques known as enhanced oil recovery. In addition to advanced drilling muds, some companies inject natural gas and carbon dioxide to push the oil up to the surface.12

The combined impact of these improvements has been huge.13 If exploration, drilling, and extraction each improved by 1 percent per year—a conservative assumption—and if each had the same weight, we would see a total improvement of 3 percent, compounded annually. That’s not exactly Moore’s Law, which famously stated that the power of semiconductors would double every eighteen to twenty-four months, but it’s still very significant. Get better by 3 percent each year, and you will increase productivity by 23 percent in seven years and by 55 percent in fifteen years. What used to be produced for $3 now costs less than $2. These improvements have made it possible to develop oil fields more fully and to extend their useful lives for many more years. BP’s oil field at Prudhoe Bay, Alaska, which opened in the early 1970s, was expected to shut after 40 percent of the oil was extracted. Now, with greater efficiency and lower costs, it may well continue operation until 60 percent has been extracted, half again as much as originally anticipated.14

All of these factors are crucial when deciding how much to bid for an oil tract. The oil in the ground may be the same for all bidders, but how much we bid differs according to the technology we use, the equipment we employ, and the skills of our engineers and drilling crews. And that’s just at a point in time. The vital question isn’t how good we are today, but how much better we are likely to become at exploration, drilling, and extracting over the life of the field.

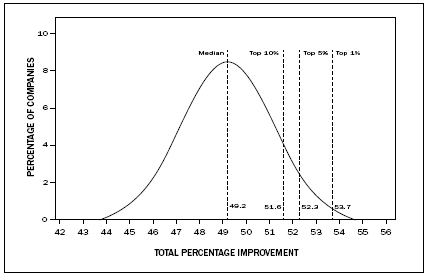

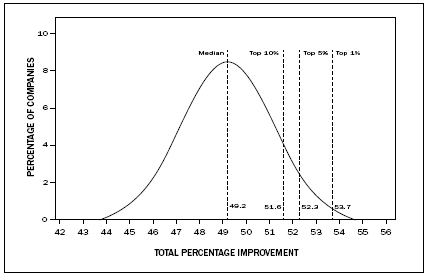

To see what this means, I designed another Monte Carlo simulation. This one assumed that the oil field has a useful life of fifteen years, during which three capabilities—exploration, drilling, and extraction—each improve at an average of 1 percent per year.15 The result shows a median improvement over fifteen years of 49.2 percent (see Figure 10.1). In other words, the same quantity of oil should cost about half as much to bring to the surface. The amount a company should be willing to pay reflects the present value of the stream of cash flow over the life in the field, with each year’s volume extracted more and more efficiently.

FIGURE 10.1 15 YEAR IMPROVEMENT OF OIL EXPLORATION, DRILLING, AND EXTRACTION

Is making a bid based on anticipated improvements an example of overconfidence? By one definition, yes. It smacks of overestimation. It exceeds our current level of ability. But by another definition, betting on an annual improvement of 3 percent isn’t excessive at all. It’s in line with the historical rate of improvement. The problem is, your rivals are also likely to improve at a similar rate, meaning that betting on a 3 percent rate of improvement probably won’t be enough to win. It will only bring you to the midpoint of expected improvements.

To have a good chance of winning, you might want to make a bid that puts you in the top 10 percent, which means betting on an improvement of 51.6 percent over fifteen years. To stand a better chance, you might want to go still further—toward the high end of what could be justified by historical rates. An improvement of 52.3 percent could be expected to occur one in twenty times. Such a bet would seem to be an example of overestimation, but even then you wouldn’t win the auction if a rival was willing to be even more ambitious. To have a very good chance of winning the auction, you might want to be in the top 1 percent, which means betting on an improvement of 53.7 percent.

We’re not far from what happened when we combined an ability to improve performance with the need to do better than rivals—much like in the Tour de France, but without any illicit doping. Anyone hoping to win a competitive battle, in which the winner takes it all, will have to bid more than seems warranted and then exert control to achieve those gains. Put another way, anyone not willing to go out on a limb won’t stand much of a chance of winning.

Of course it’s wise to beware of the winner’s curse. The analysis conducted by Atlantic Refining Company, all those years ago, helped identify an insidious problem. The rules suggested by Ed Capen to moderate bids are a step in the right direction. But it’s a mistake to take a simple classroom experiment using a common value auction and apply its findings to private value auctions, where capabilities can improve over many years. When we can exert influence and improve outcomes, and in particular when we have many years in which to do so, a very different logic applies. Seeking to avoid losses and steer clear of dangers may seem prudent, but it will not lead to success. In addition to a clear understanding of base rates and a careful analysis of possible improvements, we also need to take calculated risks.

FROM BUYING SHARES TO BUYING COMPANIES

Beyond nickel auctions and shares of stock, the winner’s curse has also been used to explain the high prices paid for corporate acquisitions. Consider this question from a leading text in the field, Judgment in Managerial Decision Making:

Your conglomerate is considering a new acquisition. Many other firms are also “bidding” for this firm. The target firm has suggested that they will gladly be acquired by the highest bidder. The actual value of the target firm is highly uncertain—the target firm does not even know what they are “worth.” With at least half a dozen firms pursuing the target, your bid is the highest, your offer is accepted, and you obtain the acquisition. Have you been successful?16

According to the author—Max Bazerman, who conducted the nickel auction—it’s likely your firm has not been successful. If you paid more than other bidders, you probably paid too much. The reason, of course, is the winner’s curse, coupled with common biases we have already discussed, notably overconfidence. Managers are therefore cautioned to temper their optimism and recognize that the acquired company is likely worth much less than they imagine. They should bid less than they would otherwise offer, or perhaps refrain from making a bid at all.

There’s another syllogism at work:

• Most acquisitions fail to deliver value.

• Bidders are prone to the winner’s curse.

• Therefore, acquisitions fail to deliver value because of the winner’s curse.

From there, it’s a short step to suggesting that excessive bids stem from overconfidence.17 We point the finger at excessive optimism, perhaps due to the runaway ego of chief executives. That makes for a satisfying explanation, of course. We love to see the mighty fall. We’re pleased to see the rich and arrogant get their comeuppance. But as we know, it’s too easy to make these sorts of judgments after the fact. As long as executives are successful, they’re likely to be described as bold and confident; it’s only when things go badly that we talk of overconfidence or hubris or arrogance. (The only exception I know of is the chairman of French conglomerate Vivendi, Jean-Marie Messier, who was seen as a personification of arrogance even before his company foundered. His nickname, J4M, stood for Jean-Marie Messier, Maître du Monde.)

What’s a better way to explain the poor track record of acquisitions? Very likely there’s a combination of forces at work. One is overestimation. Even if it’s not as pervasive as often suggested, some managers surely do overestimate their ability to drive revenue growth and cost savings. Chief executives who are the most optimistic about the benefits they expect to achieve will be willing to pay much more than others. Second is the paradox that successful managers may be the worst offenders, having grown accustomed to past success and therefore imagining they will succeed in the future, even when attempting something much more difficult. They focus on their own personal rate of success—the inside view—and neglect the rate of success in the population—the outside view. Third is the problem of asymmetrical incentives. Chief executives may be willing to take a dubious chance if they know they will benefit handsomely for getting good results but will suffer little if things go poorly—or even walk away with a large severance payment if the deal goes badly. Heads I win, tails I win even more.

Given the generally poor record of acquisitions, it’s easy to conclude that any time we are tempted to bid more than other buyers, we’re committing an error. But this is too simple a view. Morally laden terms like hubris aren’t helpful, either, because most people don’t think that concepts like hubris and arrogance apply to them—at least not until they have the same wrenching experience, at which point they ruefully admit that they suffer from the same flaws.

To blame the poor performance of so many acquisitions on overconfidence and the winner’s curse diverts us from making important distinctions. Acquisitions are typically matters of private value, not common value. A company may be justified in paying more than another if it can identify potential gains that are unique to it. Furthermore, value isn’t captured at the point of acquisition, but is created over time, sometimes several years. For that, companies can influence outcomes.

Rather than conclude that acquisitions are bound to fail, we should ask a series of second-order questions. If most acquisitions fail, do some kinds have a greater chance of success than others? What can be done to influence outcomes and raise the chances of success? Are there circumstances in which it might be reasonable to undertake even a very risky acquisition?

Let’s take these questions in order. Extensive empirical research has concluded that most acquisitions fail to create value.18 The evidence goes beyond the handful of high-profile disasters, like the TimeWarner merger with AOL at the height of the Internet bubble. Mark Sirower of New York University studied more than one thousand deals between 1995 and 2001, all worth more than $500 million, and found that almost two out of three—64 percent—lost money. On average, the acquiring firm overpaid by close to 10 percent.19

But do some kinds of acquisitions have a greater chance of success than others? A significant number—the other 36 percent—were profitable, and they turned out to have a few things in common. The buyer could identify clear and immediate gains, rather than pursuing vague or distant benefits. Also, the gains they expected came from cost savings rather than revenue growth. That’s a crucial distinction, because costs are largely within our control, whereas revenues depend on customer behavior, which is typically beyond our direct control.

For an example of successful acquisitions that sought gains from cost savings, consider the string of deals carried out by Sandy Weill in the 1980s and 1990s, when he merged Commercial Credit with Primerica and then with Travelers. Each deal was aimed at finding cost synergies, usually by combining back office functions and consolidating operations, and each was successful. Later, when Weill engineered the 1999 merger of Travelers with Citibank, the outcome was different. This time the logic of acquisition depended on revenue gains through cross-selling of banking and insurance products; sadly for Citigroup, those gains never materialized. What had been intended as the crowning achievement of Sandy Weill’s career turned out to be a deal too far.

As for circumstances in which it might make sense to attempt a risky acquisition, we need to consider the competitive context. We need to look at questions of relative performance and the intensity of rivalry. The amount a firm is willing to pay should reflect not only the direct costs and expected benefits, but broader considerations of competitive position. In 1988 the Swiss food giant, Nestlé, was willing to pay a high price to acquire English confectionary company Rowntree, maker of Kit-Kat and Smarties, not only because it saw a potential to create value, but also to make sure that Rowntree was not acquired by a rival Swiss chocolate company, Jacobs Suchard. Nestlé’s offer of $4.5 billion reflected a calculation of gains achieved—revenue growth and cost savings—as well as strategic considerations, the latter of which could only be calculated in the most general terms. It preferred running the risk of making a Type I error—trying but failing—rather than a Type II—not trying at all.

To understand the dynamics of decision making in an acquisition, we need to do more than look at the overall (often poor) record of acquisition success, then cite the results of laboratory experiments like the nickel auction, and suggest one is due to the other. We also have to think about some of the elements we have discussed in previous chapters: control, relative performance, time, and leadership.

For that, let’s take a close look at a real acquisition. Let’s go back a few years and recall the bidding war for AT&T Wireless.

THE TEXAS SIZE SHOOT-OUT FOR AT&T WIRELESS

This story began in the autumn of 2003, when the US wireless industry was moving from a phase of rapid growth to one of price competition and consolidation. After years of generous profits, cell phone carriers were feeling the strain of declining profit margins. AT&T Wireless, spun off from AT&T Corporation in 2000, was among the worst hit, beset by technical problems and losing subscribers. Its share price had slipped all the way down to $7, barely half the level of one year earlier. Rivals were gaining ground.

The largest US carrier, Verizon Wireless, had 37.5 million customers from coast to coast. The number two carrier, Cingular, was a joint venture owned 60 percent by San Antonio–based SBC and 40 percent by Atlanta-based BellSouth. Cingular had 24 million customers and a strong regional position, but was seeking a national position.

The chief executive of SBC was Ed Whitacre, a six foot four Texan known as “Big Ed” who had climbed the ranks at Southwestern Bell, a regional carrier in the old Bell system. In 1996, when the Telecommunications Act opened local markets to competition, Whitacre was fast out of the gate, buying one rival after another. In 1997 Whitacre’s company, now known as SBC, acquired Pacific Telesis for $16.5 billion, and the next year it added Southern New England Telecommunications Corp. for $4.4 billion. Whitacre’s goal was to build the country’s largest telecommunications company, offering both fixed and wireless services.20 In 1999 SBC paid $62 billion for Ameritech Corp., the leading phone carrier in the Midwest.21 In 2000 it teamed up with BellSouth to create Cingular, which soon became the number two wireless carrier behind Verizon Wireless.

In late 2003, as AT&T Wireless was struggling, Cingular sensed an opening. On January 17, 2004, it offered to buy AT&T Wireless for $11.25 a share. It was a nonbinding offer, little more than an opening gambit, but when the word got out shares of AT&T Wireless rose sharply. If Cingular was willing to pay $11.25, an eventual sale might go for more—maybe much more. Three days later the AT&T Wireless board formally decided to entertain offers from buyers. The auction would be handled by its banker, Merrill Lynch. Its law firm, Wachtell Lipton, was a specialist in mergers and acquisitions and had invented the “poison pill” defense. No one bought its clients on the cheap.22

For Cingular, the attraction was obvious. Adding AT&T Wireless’s 22 million customers would give it a national position and vault it into first place. The cost savings could be massive. By combining operations and back office functions, Cingular might lower costs by $2 billion a year, maybe more.23 An SBC executive commented, “This is the most strategic acquisition for Cingular with compelling synergies, and we are determined to be successful.” Whitacre later explained: “There are only so many national licenses in existence, and they rarely become available for purchase. So when the ‘For Sale’ sign went up, everybody in the wireless world sat up and took notice. . . . For SBC to become a major player over the long term we needed a national footprint—a regional presence wasn’t going to carry us. With the assets of AT&T Wireless in our back pocket, we’d instantly gain national standing and recognition. Without it, we’d always be a second-string player.”24

But Cingular wouldn’t be alone. The world’s largest network operator, Vodafone, based in the United Kingdom, was also interested in buying AT&T Wireless, and if anything Vodafone had an even more audacious record of acquisitions. In 1999 it doubled in size by scooping up California-based AirTouch, gaining in the process a 45 percent minority share in Verizon Wireless. A year later it doubled again with the takeover of Mannesmann, the first hostile takeover in German industrial history, for a staggering €112 billion. Yet Vodafone was dissatisfied with its minority share in Verizon Wireless and was looking to build its own position in the United States. The acquisition of AT&T Wireless would give Vodafone what it desperately wanted, and chief executive Arun Sarin indicated he was ready to bid. The Wall Street Journal described the looming contest between the two titans as “a Texas-size shootout.”25

AT&T Wireless’s banker, Merrill Lynch, used a number of ways to estimate its client’s value and converged on a range between $9.00 and $12.50 per share.26 In parallel, Cingular and Vodafone made their own calculations. Meeting privately, Vodafone’s board approved a ceiling of $14, but hoped it could make the deal for much less. One industry analyst described the contest: “It is scale—Cingular, versus scope—Vodafone. Cingular is betting on cost synergies, particularly the opportunity to work on redundant infrastructure overhead, while Vodafone is betting on economies of scope, trying to apply the same aggressive recipe they have used in Europe to the US.”27 But of course anything can happen when executives get caught up in a bidding contest. The initial bids would be sealed, but after that the bidding would go back and forth, so that AT&T Wireless could secure the highest price possible.

Bids were due at 5:00 PM on Friday, February 13, 2004. They came in just after hours. Vodafone offered $13 a share, which valued AT&T Wireless at $35.45 billion. Moments later Cingular’s bid arrived, offering just a bit less: $12.50 a share, for a value of $33.75 billion. Both parties proposed all-cash bids—no stock swaps, just cash. All of this was good news for AT&T Wireless on two counts. Both bids were above the range that Merrill Lynch had calculated, meaning that AT&T Wireless shareholders would receive a solid premium. Even better was that the bids were close to one another. With just fifty cents separating the bids, the process would go on, as one of the bankers explained to me, “until the seller is satisfied that the bidders have exhausted their ammunition.”

On Saturday morning the AT&T Wireless board directed its bankers to seek “improvements in prices and terms,” a polite way of saying it wanted more money. Merrill Lynch sent word to Cingular and Vodafone that a second round of bids was due the following day, at 11:00 AM on Sunday.28 Now a protracted battle was shaping up among parties spread across Manhattan. The AT&T Wireless team, led by its president, John Zeglis, settled in at Wachtell Lipton’s offices on 52nd Street. The Cingular team, led by Stan Sigman, set up a war room at the offices of SBC’s lawyers in lower Manhattan. The Vodafone team dug in with its lawyers at 425 Lexington Avenue across from Grand Central Station, where it stayed in close contact with company headquarters in England.29

The next bids arrived on Sunday morning. Vodafone didn’t know how much Cingular had bid, but had been told only that its offer of $13 wasn’t enough. One of Vodafone’s bankers explained to me: “The psychology was, we had to move up. If we didn’t move up, the seller would get the sense we were maxed out. We were each eyeing the other, wanting to keep it moving.” After some deliberation, Vodafone submitted a bid of $13.50, still under the board limit of $14. Meanwhile, Cingular executives decided it was time for a major push and upped their bid all the way to $14, for an astonishing sum of $38.2 billion.30 Now Cingular was in the lead.

On Monday morning, the President’s Day holiday, Merrill Lynch contacted Vodafone and said that Cingular had pulled ahead. Vodafone now raised its bid once again, to $14.31 Although the bids were even, a tie worked in Vodafone’s favor. A takeover by Cingular would likely raise antitrust concerns, which could delay the deal or block it altogether. Another reason was the impact on AT&T Wireless. Combining with Cingular could lead to significant layoffs, with AT&T Wireless employees likely to bear the brunt. Vodafone, on the other hand, would probably expand the business and add jobs. If the bids were tied, AT&T Wireless would go with Vodafone. The only question now was whether Cingular would raise its bid once again.

After lunch on Monday, AT&T Wireless board member Ralph Larsen called Cingular and Vodafone and read the same script: Best and Final Offers were due at 4:00 PM. Larsen wouldn’t say who was in the lead. Cingular’s Sigman later recalled: “They said, ‘Just because you may have been in the lead before doesn’t mean you are anymore.’”32

When the deadline came, Vodafone reaffirmed its bid of $14 but went no higher. It had reached its limit and wouldn’t be drawn into a bidding war. Cingular didn’t raise its bid, either, but added a provision aimed at one of AT&T Wireless’s concerns: in the event the deal was held up by regulators, it would pay a 4 percent interest fee every month after ten months. A good attempt, but not enough to make a difference. Vodafone still held the advantage. A final decision was imminent.

At 7:00 PM AT&T Wireless chief executive John Zeglis reached Vodafone’s Arun Sarin by telephone. It was midnight in London. Vodafone’s bid was accepted, Zeglis said. All that was needed was approval of Vodafone’s board, scheduled to meet the next morning.

As he monitored events from San Antonio, Ed Whitacre saw the deal was slipping away. He recalled, “In my mind, that was not acceptable. Wireless was the way of the future. Millions of new wireless customers were piling on by the quarter, with no signs of slowing. The mobile web was also showing a lot of promise. We simply could not afford to permanently relegate ourselves to second-tier status.”33

Although AT&T Wireless had given a verbal acceptance to Vodafone’s offer, the deal wasn’t done until the Vodafone board gave its formal approval. Whitacre figured there was still a chance that AT&T Wireless could change its mind, provided it received a higher offer. At 9:00 PM he contacted Duane Ackerman, his counterpart at BellSouth. By now, all the numbers had been analyzed. There was no new information to consider. The only remaining question was this: How much of a risk were they willing to take? Was it worth taking an even bigger risk? Whitacre recalled the conversation as direct and blunt: “‘There’s only one of these things,’ I told Duane. ‘This is beachfront property, and once it’s gone, it’s gone.’”34 They agreed to raise their bid to $15 a share, a full $1 more than what Vodafone had offered. A Cingular executive later recalled, “We thought we had a decent chance of winning at 4 o’clock, and when we didn’t win, we wanted to end it. So we ended it. Winning was the only option.”

Moments before midnight, Sigman called Zeglis at Wachtell Lipton offices and made the offer: Would AT&T Wireless accept $15 a share? That worked out to $41 billion, the largest cash deal in US history. One person recalled that the air seemed to go out of the room: “Everybody was like, ‘Whoa.’”35 Zeglis tried to keep a calm voice. Sure, we’ll accept $15, he said, as long as the offer is signed and delivered by three in the morning. That would be 8:00 AM in London, when Vodafone’s board planned to meet. Everything had to be settled by then.

With that, SBC and BellSouth called snap board meetings. Some directors were tracked down by cell phone and others were rousted out of bed. Polled by telephone, both boards approved the bid. Within minutes a detachment of bankers and lawyers, offer in hand, headed uptown to the offices of Wachtell Lipton on 52nd Street. At 2:00 AM, Zeglis recalled, “We had just finished our third pizza when Stan and his team brought over their piece of paper.”36 Zeglis checked the figures and signed on the line. The deal was done. Moments later he performed one last duty. Reaching Arun Sarin at Vodafone headquarters, Zeglis recalled, “I told him we went another way.” Vodafone’s celebratory announcement was quickly scrubbed.

HOW MUCH IS ENOUGH, HOW MUCH IS TOO MUCH?

The bidding war for AT&T Wireless had all the ingredients of great drama: a head-to-head duel between large companies, a record sum of money, and a surprise late-night ending. The press found the story irresistible. The headline in the Financial Times was typical: “Cingular grabs AT&T from sleeping Vodafone.”37 Cingular was seen as the winner, capturing the prize with a gutsy midnight move. Vodafone was portrayed as the loser, its failure to close the deal described as a “significant setback.”38

Others saw it differently. The enormous sum of money smacked of the winner’s curse. Surely Cingular had paid too much. The market was skeptical, too, sending shares of SBC and BellSouth lower, while shares of Vodafone rose.39 That’s normal. Investors have come to assume that winning bidders pay too much and routinely punish the shares of the buyer, while bidding upward the shares of a would-be buyer, relieved that they dodged a bullet.

But on closer inspection, both sets of executives made reasonable bets. Vodafone set a limit of $14 a share before the bidding began and stayed with that limit.40 Far from getting caught up in the bidding war, it calculated the maximum it would pay and didn’t get swept up by ego or emotion. Neither Arun Sarin nor his top team gave in to the psychology of the moment to try to get the Vodafone board to raise its limit.

As for Cingular, the last-minute decision to raise the stakes raised the specter of the winner’s curse. Phrases like “winning was the only option” sound like bravado. As Whitacre later put it, he and Ackerman made a desperate effort to throw a touchdown pass and win the game. No question, alarm bells should sound when an executive justifies spending a record amount of money by reasoning that the opportunity is unique. Even beachfront property can be overvalued.41

We might conclude that Cingular fell victim to the winner’s curse if this were a common value auction, but a corporate acquisition is different. It’s a private value auction in which gains aren’t captured at the time of the deal, but created over time. Furthermore, much of the value to Cingular would come from cost savings, a more predictable source of gain than revenues. There were also competitive considerations. Whitacre recalled: “There was only one AT&T Wireless, and we had exactly one shot to get it right.”42 That’s not to say any price, no matter how high, would have been justified. Cingular was surely at the upper limits of what it could pay. The fact that Whitacre and Ackerman were trying to salvage a deal that had almost slipped away suggests they had already reached the limit they set for themselves. But if the choice was between spending $1 per share more to clinch the deal or letting AT&T Wireless get away, deciding to push ahead was not obviously wrong. The cost of a Type I error—at $15 a share, paying too much—was less onerous than the cost of a Type II error—failing to grasp the nettle and losing the bid. Whitacre saw it in precisely those terms: “The financial implications for SBC and BellSouth were not insignificant. But the downside to not winning AT&T Wireless could be devastating over the long term.”43 Long-term strategic considerations trumped short-term financial calculations.

There was, finally, the question of leadership. Whitacre had a reputation for bold moves. He was not known for shrinking from big deals, but for rallying his team to greater heights. Making a strong push to win this deal would reinforce his reputation as a leader. As Whitacre saw it, it was crucial to press ahead: “That, ultimately, is what builds enthusiasm and momentum within a company—the feeling that By God, we’re actually doing something here; this company is on the move; I can be proud of where I work.”44

How did the acquisition of AT&T Wireless work out? Once the deal went through, Cingular moved quickly to capture combination benefits. Through concerted efforts at cost reduction, it more than achieved expected synergies. By 2006 those savings had reached $18 billion, 20 percent more than had been estimated at the time of the deal. There were strong revenue gains, too.45 Overall, the acquisition of AT&T Wireless turned out to be profitable for Cingular. One of the bankers involved in the deal later told me, “At $15 [per share] the deal worked out fine for Cingular. They were the right buyer, and they created value.”

And the story doesn’t end there. The following year, in January 2005, Whitacre announced plans to acquire the rest of AT&T Corporation, the parent of AT&T Wireless. He was still determined to create a global leader, with powerful positions in both wireless and fixed line communications. In a surprising move, Whitacre took the name of the company he bought, calling the combined entity AT&T Inc., commenting, “While SBC was a great brand, AT&T was the right choice to position us as a premier global brand.” The new AT&T became a market leader in wireless communication, with strong positions in DSL broadband lines, local access, and long distance lines.46

Even then, Whitacre wasn’t finished. He next acquired BellSouth, his partner in the Cingular joint venture, bringing the entire network under his control. In January 2007 Cingular was rebranded as AT&T Wireless. Just three years after AT&T Wireless put itself up for sale, the AT&T brand was reborn, this time as the US market leader. As for Ed Whitacre, he was in charge of what Fortune magazine in 2006 named “America’s Most Admired Telecommunications Company.” The record bid for AT&T Wireless in February 2004 had been an essential element of a winning strategy.47 Looking back in 2013, Whitacre observed: “That deal cemented our place in the US wireless industry. It also changed the landscape of the industry for all time. I knew that going in, which was why I pushed so hard. And man, I want to tell you, we pushed that one about as far as you could push.”48

By one definition, paying $15 per share for AT&T Wireless was an excessive bid. It surpassed what could be justified based on current calculations of costs and revenues. If the deal had failed to deliver value, Whitacre would surely have been castigated for hubris. Critics would have blamed the winner’s curse. But $15 per share was not excessive given that AT&T Wireless offered benefits that were unique in the landscape of telecommunications, and once lost might be gone forever. Ed Whitacre understood that in a competitive arena, where managers can shape outcomes, the only way to succeed is to take calculated risks—not just risks that lend themselves to precise analysis, taken out to several decimal points, but risks that are understood in broad brush strokes. Only those willing to take large and even outsize risks will be in a position to win.

THINKING ABOUT COMPETITIVE BIDS

Many complex decisions involve competitive bids, whether tendering a low bid to win a contract or making a high bid to acquire a property or a company. For anyone engaged in competitive bidding, familiarity with the winner’s curse is vital. You don’t want to pay more than $2 for a roll of 40 nickels—certainly not when you have ready alternatives. You don’t want to pay more than market value for a share of stock, thinking that you know something others don’t.

Yet once again, we sometimes generalize the lessons from one situation without understanding important differences. Classroom demonstrations about the winner’s curse are a good way to illustrate the perils of common value auctions, but we need to be careful when we apply them to private value auctions, let alone to situations in which we can influence value and performance is relative. Very different circumstances call for a different mind-set.49

So when are winners cursed? In simple experiments, the bidder who wins the prize is almost always cursed. The real winners are those who keep their wallets shut and refuse to be drawn into a bidding war. But in many real-world situations, the truth is more complex. When we can influence outcomes and drive gains, especially when the time horizon is long, we can and should bid beyond what is currently justified. And where competitive dynamics are crucial, it may be essential to do so. We must consider not only the dangers of paying too much—a Type I error—but also the consequences of failing to push aggressively—a Type II error.

The real curse is to apply lessons blindly, without understanding how decisions differ. When we can exert control, when we must outperform rivals, when there are vital strategic considerations, the greater real danger is to fail to make a bold move. Acquisitions always involve uncertainty, and risks are often considerable. There’s no formula to avoid the chance of losses. Wisdom calls for combining clear and detached thinking—properties of the left brain—with the willingness to take bold action—the hallmark of the right stuff.

![]()

* If the words “Atlantic” and “auction” have a familiar ring, you might remember the Marx Brothers movie The Cocoanuts. Groucho says, “I’ll show you how you can make some real money. I’m gonna hold an auction in a little while at Cocoanut Manor. You know what an auction is, eh?” Chico answers, “Sure. I come from Italy, on the Atlantic Auction!”