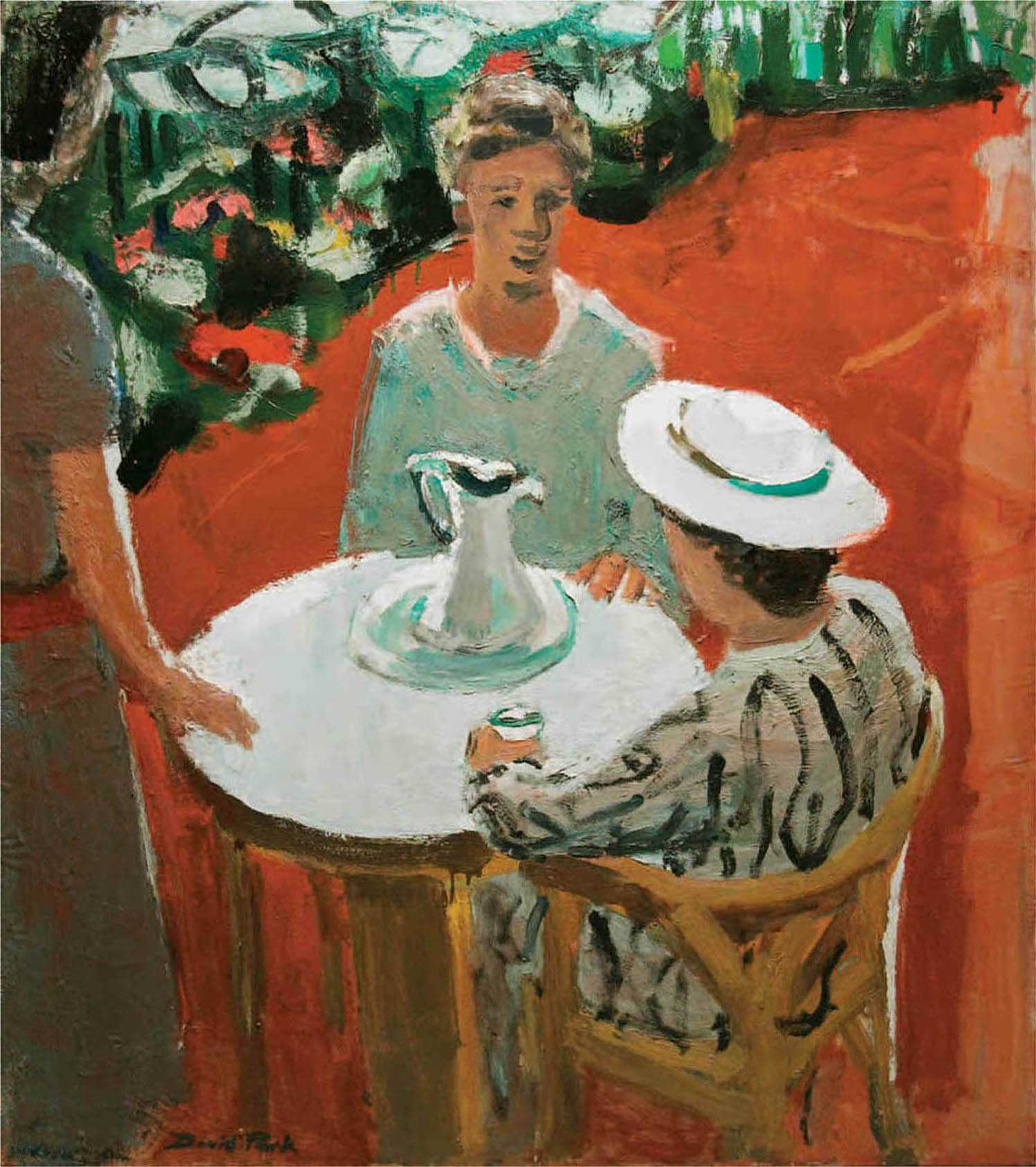

Fig. 100. The Patio, 1956 Oil on canvas, 51 × 45½ in. (129.5 × 115.6 cm.) Private collection

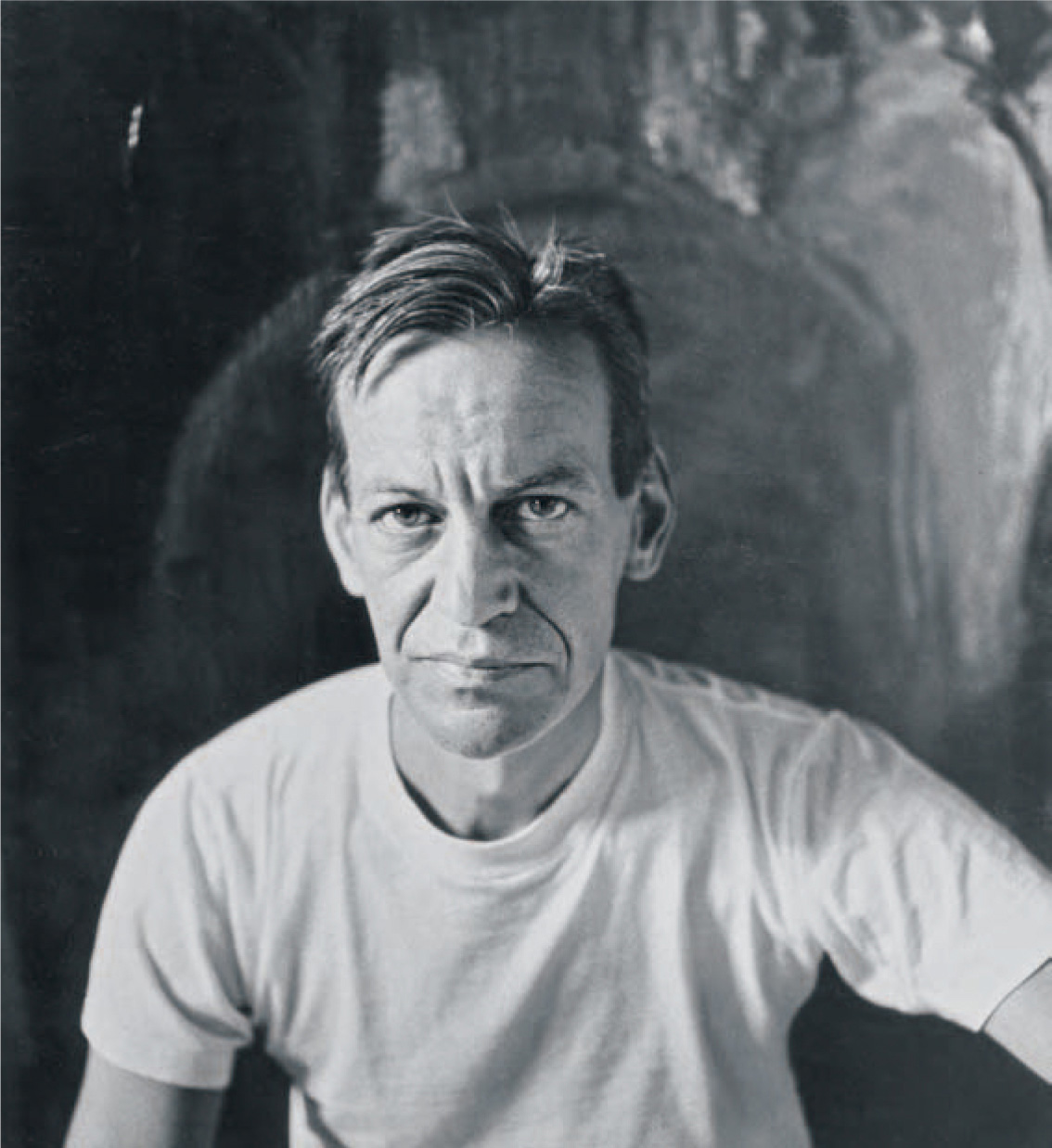

IN HIS 1998 CATALOGUE ESSAY FOR A SHOW OF DAVID’S WORK at San Francisco’s Hackett-Freedman Gallery, Paul Mills remarked, “David would have made a marvelous old man.” When I read that sentence I thought, Yes. For years, I looked at men born around 1911, thinking about what David would be like, this elderly man, this old painter. No matter how many years he might have lived, I know he would have gone on working, and always come down from the studio exhausted.

It would be easy for him, now, to pay his bills. The black cloud wouldn’t rise off the pages of the big flat checkbook and penetrate each room of the house. I wish sales of paintings had provided enough money to live on during his lifetime, but I’m glad he knew recognition was coming. I wish I could ask him if he remembered our conversation that evening on the driveway when he asked me about the four basic human needs.

I wonder what his paintings would be like now. In the gouaches that are his last work, and in the late oils, the union of figuration and abstraction made for increasingly potent and timeless paintings. More would have come, but beyond that I can only guess. In Richard Diebenkorn’s work I can trace the linearity in the Ocean Park paintings back to his figurative years when he painted Phyllis sitting in a wicker chair gazing toward a window. Beyond the frame of the window are power lines and an abstracted, linear landscape. When he took the chair and the figure out of the picture he came into his Ocean Park series. In the early Diebenkorn abstract paintings, before his figurative work, the shapes I used to think of as blobs seem to me in his later period to have become figures in chairs. In at least some of Diebenkorn’s work, from abstract paintings to the great Ocean Park series, there is, to me, a traceable look.

Would I be able to trace David’s look? What would have happened to his rowboats, his violins, his bathers? I’ll always wonder. But I don’t wonder at all about David’s other great gift, that of friendship, and how, had he lived, it would have played in my life. Always I have known that David would be crazy about my daughters, and also about my closest friends. He and they are of a kind. We would all sit around the living room drinking our wine (well, he’d be drinking a martini or some I. W. Harper on the rocks) and talking the way we all talk, analyzing politics or what we’re reading or the day’s news. The evening would be as full of color as the thick paint on his canvases.

The loss of David has so many layers. My heart aches with wishing David’s seven grandchildren and his nieces and nephews had him in their lives. I know that David and my husband, Ed Bigelow, would have been delighted by each other.

But we have the paintings. Even when we don’t own originals, we all cut out color reproductions from catalogues and frame them for our offices, our kitchen walls, our bedrooms. All of David’s family—my sister, my daughters, my nieces and nephews, my cousins—and especially my mother have lived with his work as our familiar.

I still don’t know how to behave when I first walk into an exhibit of David’s paintings. Scan the whole show, discover what is there? Allow myself to be caught up in the first painting I see and just stand in front of it? Mainly, somehow, I have to absorb the absence—and the presence—of David, and it leaves me drained. This happened in 1994 when I walked into the Palo Alto Cultural Center show called David Park: Fixed Subjects.

I was surrounded by David’s paintings. Like a pitcher on the mound or a skier before a jump, he had focused his whole being in each one of those canvases, and in that focus the rest of the world disappeared. His force filled the gallery. My chest caved in with the sense that he ought to be there, he ought to see this show, he ought to know what has happened to his work. The feeling was so strong I could almost smell him in the room beside me—the oil paint and turpentine, the Camel cigarettes.

I crossed to a bench in a far gallery, sank down, and looked around. On the walls were paintings I loved or had forgotten or that made me uncomfortable or that I had not seen for years. I stared straight ahead at a painting I could never look at for long. It disturbed me, and always had. The painting, Head (sometimes titled Boy’s Head), was not a portrait but just a human face and head with an abstracted background. As I looked at the painting the world around me receded, replaced by something that happened in my mother’s living room in 1960, two days after David died.

Home alone that morning, Deedie had walked down garden steps to the mailbox. She told me how strange it felt to be doing something so normal. She pulled out a small batch of mail. Glancing through the bills and letters, she came upon a blue envelope addressed in unfamiliar handwriting to Mr. David Park. More than a little shaken, she turned the letter over. On the back of the envelope was the printed name and address of Nancy Hale, a well-known author. Deedie and David had admired her short stories in the New Yorker and frequently read them aloud to each other. Her novel The Prodigal Women stood right over there on the bookshelf. And now, too late, she had written to David.

Deedie told me she didn’t know what to do. Should she send the letter back, still sealed, along with a note? In thirty years of marriage she had never opened David’s mail. Unsettled, she left the letter on the table and then, later, sat down and cut the envelope open at its right edge—her tidy, precise habit. That afternoon I was at her house and she handed the envelope to me. “Read it,” she said.

We stood by the dining room table, the house strangely and terribly empty of David. I removed the letter from its envelope: thin light-blue stationery with Nancy Hale’s name and address printed on the top of the page.

The letter started “Dear Mr. Park,” something I’d rarely heard my father called. Nancy Hale said she loved David’s work and was particularly interested in the paintings of heads. She said the faces were haunted. They made her think that in order to paint something so powerful David must be a haunted sort of person.

“Haunted?” I thrust the letter back at Deedie. The word evoked darkness, a painful kind of separation. All my life I’d known David was driven, fed by something the rest of us didn’t know. But haunted? That meant he had anguish. He suffered. “But he loved his life,” I said to Deedie, almost crying. “He loved people. People loved him.” The word haunted broke my heart. He had just died, he didn’t want to die, he was so young. He was so eager in life.

“He had fun,” I added, desperate that Deedie would agree. “Think of his laugh. You can’t be haunted if you laugh.”

Deedie made a slight, thoughtful nod and looked down at the letter in her hands. She folded it and put it in its envelope and looked back at me.

“Yes, you’re right,” she said. “But, well—the paintings . . .”

I didn’t ask her what she meant. She didn’t elaborate, and for years the word haunted hovered in the air around me. Deedie answered that letter from Nancy Hale, telling her how moved David would have been to hear from her. A few days later a note of condolence arrived, and that was that. As with so much of my father’s memorabilia, Nancy Hale’s letter no longer exists.

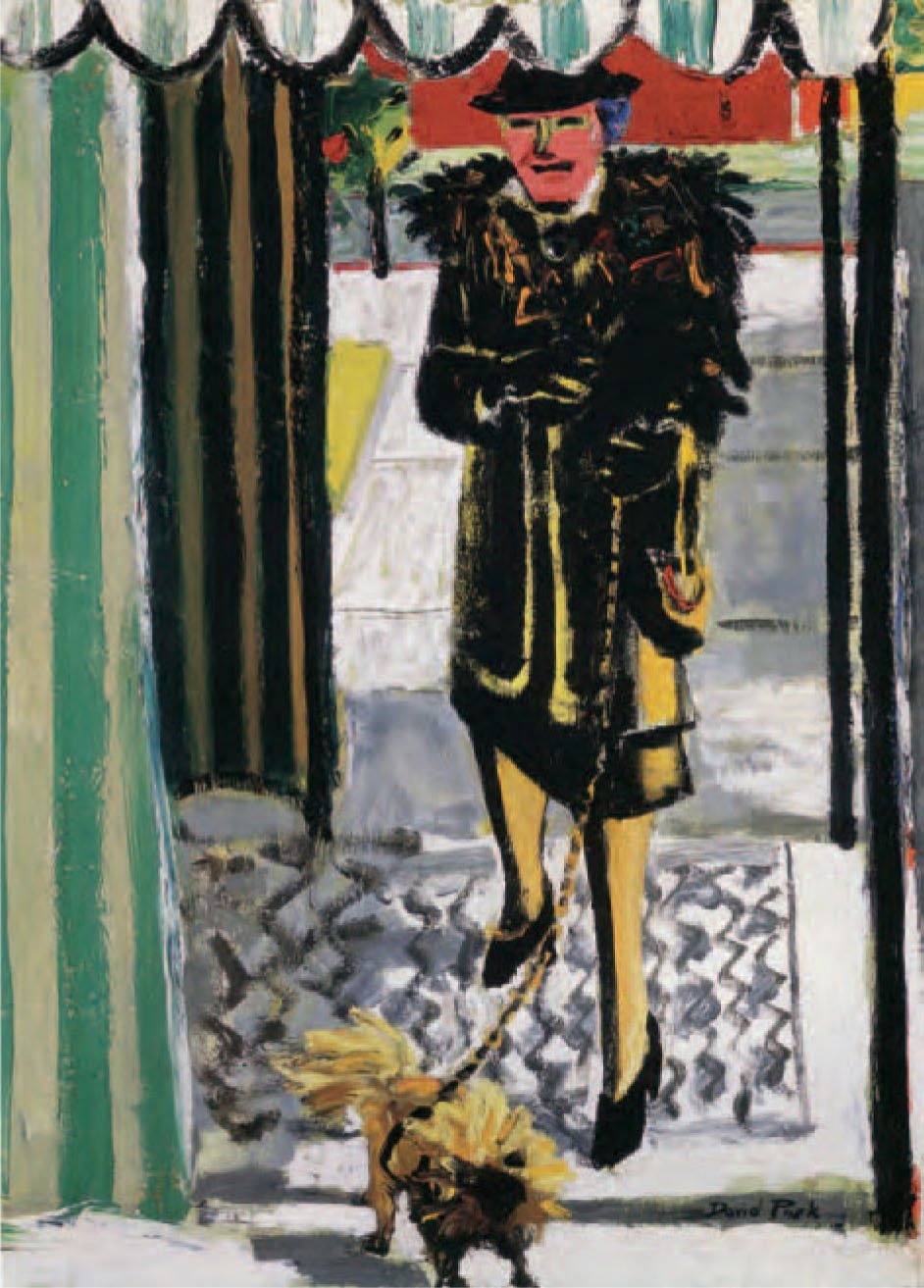

Fig. 101. Cousin Emily and Pet Pet, 1952 Oil on canvas, 46 × 34 in. (116.8 × 86.4 cm.) Private collection

From the gallery bench I looked again at Head. In my view, the few late heads in oil of 1958 and 1959, and others he painted in gouache in 1960, comprised some of David’s most powerful work. Uncomfortably, I opened my notebook, brought because I wanted to write in it while surrounded by David’s paintings. But I didn’t want to write about Head. The face in the painting was too disturbing.

I once told the painter Tom Holland about the power I saw in David’s heads. Tom had been a student of David’s, and he and his wife, Judy, became close friends of my parents. I asked Tom if he thought David was trying to make a statement in those paintings, to get across an idea about the human condition, or life and death, or something like that. Tom sort of smiled and shrugged his shoulders and said, “No, he was just trying to paint a good head.”

I know Tom was right. There are, however, a few paintings that do make a statement. One is Cousin Emily and Pet Pet from 1952. David could be stingingly sarcastic, and in Cousin Emily I feel it sizzling up from the canvas. In the painting, the figure is a caricature of a big-city woman, well off, walking her little dog. The painting highlights the foibles and attitudes of the fictitious Cousin Emily. Thinking about her from the point of view of David’s sarcasm, I can almost see the fussy little knickknacks in her apartment. The painting has been widely published. Maybe the work succeeds because of its sting.

My thoughts were interrupted, bringing me back to my hard bench. People sitting beside me were discussing David’s paintings. All my life I’ve eavesdropped in galleries, sometimes hearing viewers say things like, “Couldn’t he keep his paint from dribbling?” Or, “I can’t figure out why this painting is in a museum.” But these people today used the words masterful and bold. I soaked it up.

I turned and finally focused on the wonderful painting Women in a Landscape (page 169), a large oil I’d seen every few years. It belongs to the Oakland Museum of California. David didn’t knowingly or intentionally teach me how to look at paintings, but from an early age I saw him countless times in the living room with one of his art books open in his hands. As he looked at paintings in the book, his focus stilled the air, and after he left the room I would pick up the same book and look to see what it was he had seen. The same thing happened standing beside him in a museum.

When looking at a painting I experience an almost physical sensation, of being lifted up into the image. Peripheral vision is gone, sound is gone, I am gone, all that exists is the painting. No words come into my head to interrupt me during that first pull into the image, which can occur in front of the same painting over and over. Then words gradually enter and label colors or figures or landscape or light.

I grew up hearing about light in a painting, just as I heard about any light—at sunset or after a rain or at any moment during a day. At some point in looking at David’s paintings I saw that the way he used light was key to a painting, in the same way light is essential to vision. I see the white paint in a big splotch on the glass tabletop beside David’s easel—white paint gathered onto the bristles of his brush—the handle of the brush long since spotted and stained with old paint.

I see that David collected light, like the thin cast of blue as he went up and down the stairs of the house in Boston where he was born. As a photographer might reach for a certain filter to better capture an image, David’s painter’s mind reached into his repertoire of light. In the painting that was before me at the Palo Alto show, there is an unseen sky above the brown and ocher landscape of trees, but I sensed a cloudless autumn sky because of the way the sunlight slants into the landscape where the two women stand.

Thick dark strokes on the right suggest a tree. The landscape is heavily abstracted in the colors of New England in late fall, after the flamboyant reds and golds have faded. As a boy David walked through those woods on the way to the neighborhood pond. There he paddled canoes and rowed boats that emerged shiny and wet on canvas after canvas for the rest of his life.

No boats are in this landscape. A creamy white color and bits of red and green enter the strong, broad brushstrokes, bringing forth the figures in their landscape and the faces that are so tender and somehow so vulnerable.

Figures in a landscape, women in a landscape. I love those words as titles, for that’s what we all are, necessarily: people in a landscape here on Earth, people in a place. No matter how different in topography or climate or in our own experience, place is one of the things we have in common with everyone alive, with everyone who has ever lived. Place forms us, etches itself on our emotional lives. I don’t know if I’d be so intrigued by the concept of figures in a landscape if I hadn’t lived so long with David’s titles.

Squirming around on my bench to get more comfortable, I wrote in my notebook about this Oakland Museum painting, for I’d noticed something I’d never paid attention to—the woman’s stomach was created with one rounding sweep of a wide paintbrush. It is entirely different from the way David painted a male stomach.

I’d seen that broad-brushed sweep someplace else, maybe in several other paintings. Two of David’s late, great oils came to mind—Four Women (fig. 79) and Torso (fig. 103). Both paintings are in the Bay Area, and because I lived there for many years I was able to go and stand in front of them. Even now, living on Maui, I study those paintings in books. Both painted in 1959, both ghostlike in quality, they are, for me, markedly different. Stark and white, Four Women shocks me every time I see it. I keep thinking of David saying, “Art ought to be a troublesome thing.” I can’t resolve the troublesomeness of Four Women. It’s not meant to be resolved. Those figures are somehow beyond place, beyond time, beyond life. They touch a large and naked something, and they make me want to stand there looking.

Fig. 102. Women in a Landscape, 1958 Oil on canvas, 50 × 56 in. (127 × 142.2 cm.) Courtesy of the Oakland Museum of California. Anonymous Donor Program of the American Federation of the Arts A60.35.1

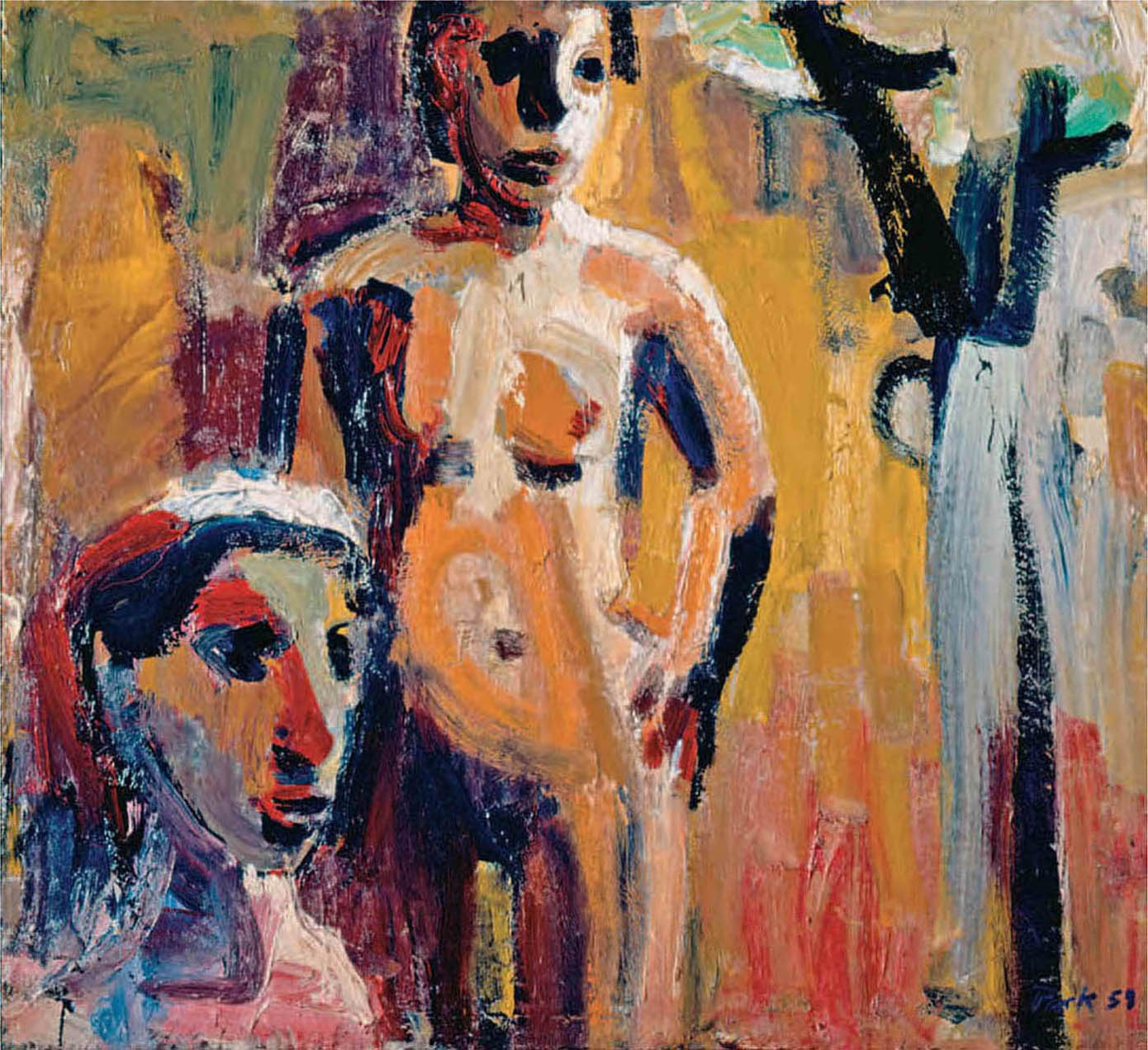

Torso, often and wonderfully hanging on a gallery wall at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, is for me stirring rather than shocking. I can enter it and feel myself captivated by the colors, the paint, the brushstrokes. That dippy swirl of white beside and below the figure’s ear, the blue-green at the upper left, the red delineating arms and breasts. The belly. The whole abstracted right side of the canvas. And the arm that’s at the figure’s hip—how in the world does that messy swipe of brown paint become so unmistakably an arm? And finally the face, that quintessential David Park face. The painting is deep and rich and far more important than the way the stomach is painted, but still I almost laughed, there on the bench at the gallery, to have noticed my father’s treatment of the female belly.

And then I turned around again and looked straight at Head. The face on the canvas was intertwined with the word haunted, so packed with meaning that for all the years since he painted it I only glanced at it in galleries and then would shy away. I thought about my mother, who died when she was almost eighty after a marriage of twenty-seven years to her second husband, Roy Moore, an Englishman. I remembered talking with David out on my back patio in Orinda, the night his voice deepened with pain. Tragically, the root cause of Deedie’s death, thirty years later, was clinical depression.

Other than that night on the patio, David and I didn’t talk about the darkness in his life, or in mine. After he died, Nat and I heard a rumor that he and Ann Wykoff had been lovers. We’d wondered, for there was a sparkle in the air around the two of them that we noticed as kids. Perhaps I was even aware of it as a toddler looking down at Ann and David while they played their four-handed duet. And men gravitated toward Deedie, who told me once that an old family friend had been crazy about her all his adult life. She was proud and awed by this.

And then of course there was the shipboard romance, when Deedie “lost her heart” to one of the freighter’s officers. Did my parents have occasional affairs? Were there other men, other women? Did affairs or other relationships cause pain, suffering, insecurity? In what ways did David’s sexuality affect his work? More than having affairs, I can imagine David burning his energy out on canvas and collapsing into bed without a thought of sex. My interesting parents—where were their life stories played out on the sexual spectrum? The number of things a child does not know about his or her parents is vast.

Fig. 103. Torso, 1959 Oil on canvas, 36⅜ × 27¾ in. (92.4 × 70.5 cm.) San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, gift of the Women’s Board, 60.7426

According to Deedie’s brother, Gordon Newell, when David left Los Angeles and the Otis Art Institute he walked along the coast all the way to San Francisco. When possible, he walked on beaches. That’s about four hundred miles. It would be the walk of a lifetime, and David never once mentioned it. Gordon said that a tragedy had happened and that David had been impelled to walk his way through it. It was something about a girl he knew, and her suicide.

Nat and I had never heard a word of this tragedy. In an interview, Deedie offhandedly dismissed the four-hundred-mile walk by saying it was “one way of seeing how the land lies.” Maybe Gordon misremembered, or maybe that’s all Deedie chose to say. I don’t know. I have only my imagination placing David, eighteen, walking mile after mile on a beach wherever he could get to it. Heading north, white surf rolled in on his left and washed away his footsteps in the sand behind him. In spite of all that abundance of light and surf and air, he never mentioned the experience. I can only wonder why.

Fig. 104. David Park, c. 1958. Photograph by Imogen Cunningham ©The Imogen Cunningham Trust

And what I could now finally accept, after so many years, was that human pain—and his own pain—showed in David’s work. When I wailed at my mother over Nancy Hale’s comment and said that David wasn’t haunted, that he’d had a good life, Deedie said, “Yes, but—the paintings . . .”

What she meant was, Look what he put in the paintings. In front of me was Head. Finally, I sat there looking at it, and took it in. I saw that it and David’s other paintings of heads transcended their rich, thick paint and the abstracted features on the faces and whether or not they were good paintings of heads. As with every painting, David put his all into it, his David-ness, his history and stories, and all those years of dedication to his values. In wanting to paint a pure head, one not narrated by setting, not about foibles or attitude, he found something universal, or at least that had become my view. I began to see the head in front of me as a kind of self-portrait. Not an external likeness, but a portrait of the inside of David Park, human being. I looked at the painting and was in awe of the fact that my skinny, tired father stood in his studio and painted the human soul.

Fig. 105. Head (Boy’s Head), 1959 Oil on canvas, 32 × 26 in. (81.3 × 66 cm.) Smithsonian American Art Museum Bequest of Edith S. and Arthur J. Levin

When David died, something hugely vital seeped out of my life. In those days, we hadn’t been told that people experience stages of grief. Compared to now, grief was a little-used word. At the time, I was extremely busy coping with my husband and my three young children, and, I am told, I didn’t ever really talk about my father’s death. I never thought to talk about it. It was all around me. I lived in it, awakened into it in the morning like waking into air, and had no distance from which to observe my feelings or name them. I do remember hearing the expression “Time heals” and not comprehending. It seemed to me that time might dull a terrible loss, but it couldn’t heal it. Nothing could. Loss is a human experience and we wear it like paint on a canvas, thick, in swirls and peaks and brushstrokes, with other colors hidden underneath.

Sitting in the gallery with my notebook, the paintings meant more than ever before. They’d given me more of David and the sorrows in his life. I realized that I’d been haunted by whatever it was that haunted him. Through finally confronting my own reactions to Head, David became, for me, a fuller man. I took a last, slow stroll around the gallery with a new sense of David and his life to add to the richness I already knew, as if his reds had deepened and his blues and greens had never been so bottomless.

In 1976, I abandoned one of my father’s late, great oils and left it to burn. It’s worse than that. Actually, I abandoned three large oils and two gouaches. Ed and I had gone to bed in my little cottage, where my youngest daughter, sixteen-year-old Peggy, was sleeping upstairs. It was about 12:30 when we turned off all the lights. At 2:09, according to the red dots on the new digital clock radio Ed had given me, he awoke abruptly and leapt to his feet. A noise had awakened him. He grabbed his robe and rushed out of the room, thrusting his arms in the sleeves. The robe’s long tie flowed out on either side. By then I was following him—same scene: robe, arms, sash. The noise was extremely violent, and I was terrified. I thought one of the cats was in a death battle with a raccoon.

Rounding a corner ahead of me, Ed suddenly yelled, “Fire! Get outside! The house is on fire!” He barreled up the stairs to Peggy’s room with me close behind, but was stopped by flames pouring out of the bathroom. He yelled, “Peg, Peg, the house is on fire, go out on the roof.”

But she had awakened a moment before, opening her eyes and wondering why the room was filled with fog. She started to sit up, saw flames, heard Ed, and dove out the window. “I’m out, I’m on the roof, get Mother out,” she screamed back at him. We both wheeled and rushed back down those steep, treacherous stairs. I heard Ed bump and fall behind me, but he was up again and then we were shoulder to shoulder, turning toward the outside door. On the wall at my right hung a large painting by my father—fifty-five by forty-five inches. I almost grabbed it, but it was so big that to carry it through my small, crowded house I would have had to move sideways. Instantly I knew that taking it would slow me down.

I didn’t make a decision, I recognized one. I needed to get my daughter off that roof. I abandoned the painting. With a stab of pain, knowing exactly what I was doing, I ran toward the door.

My mind closed against the other paintings in the house and I burst outside to a blast of sweet air. Rushing to the back patio, I looked up. There she was, standing on the flat roof in her underwear. She covered her bare chest with her arms, her straight blond hair hanging by her face as she looked down at Ed and me. She was backlit by a wall of leaping flames.

“Jump,” I yelled, but she called down that she was scared, so I told her to sit down and scoot off. Ed and I stood underneath her with our arms up as if to catch her.

Looking down at us she called, “I’m afraid I’ll hurt you.”

In my fullest and most frantic and most absolutely demanding mother-voice I screamed at my daughter, “Scoot over and drop off NOW.”

She jerked a shoulder as if it had been bitten, and turned toward the flames now shooting out the window from which she’d crawled. A burning spark had just lit on her back. She hung on to the gutter and dropped off.

We three crashed to the ground, got up, and held each other, staring for one long moment at the house of flames. Peggy had broken a bone in her heel, but we didn’t know it then. Suddenly I jerked away from the horrible fascination in front of me and plunged across the yard yelling at the neighbors, “Help! Fire! Call 911!” While I was doing this, Ed made a dash through the front door and pulled out a painting named Beachball, which he set on the ground by a huge tree about thirty feet from the house. He sprinted back to the front door to try to rescue another painting, for although we had never discussed it, he knew exactly what had to be saved. But Peg tackled him yelling, “Don’t, don’t.” Her tackle slowed him down, and in that moment he saw that he had done what could be done, that to try for more would be suicide.

A few hours later, the fire still burned. With fire trucks and hoses all over the street, with utility trucks and police cars and neighbors everywhere, with Peg wrapped in a blanket and me in my bathrobe, we watched in awe and also in a wild and almost glorious kind of joy. We kept hugging each other and saying, “You’re alive. I’m alive. We’re all alive.” Very soberly, the fire marshal had told us that we’d had only about one minute to spare. That if we’d slept one minute longer we would not be alive. Especially Peggy, for her room had exploded into flame when the burning bit of something hit her shoulder. If Ed hadn’t awakened—if Peg hadn’t awakened—“You’re alive,” I said again, a hand on each side of my daughter’s face, and we burst out laughing. The neighbors spread away from us, probably thinking we’d gone mad, and, in a way, we had.

In firefighting terms the house was “fully involved.” Nothing we owned would be saved. The one painting that Ed had rescued, and Peggy was now holding, had been placed thirty feet away from the fire, with its painted surface toward the tree. That surface was now charred and smoke-blackened and had little craters from boiled paint. I already knew I would do anything possible to have it repaired.

When I tell people the story of my house burning down, they inevitably think about what they would try to save. “The pictures of my kids” is what most say. But I am not one of them. Having saved ourselves softened all our other losses, which was everything in the house, including pictures of my children, their artwork and memorabilia, our books and our family heirlooms. And none of it matters to me the way the loss of the paintings matters. The other losses fade; the loss of the paintings grows. It pains me more now than it did five years ago, or ten. That is just the way it is.

Fig. 106. Beachball, 1955 Oil on canvas, 24 × 18 in. (61 × 45.7 cm.) Private collection

David gave me Figures in a Landscape back in the fifties. He invited me to choose a painting for myself, and it is what I picked. Nat was made the same offer, and that’s when she chose Boston Street Scene (fig. 64). Each of us, at different times, went to the studio and stood looking at what was on the easel and what was standing on the floor. David moved canvases around so we could see everything. It took a long time and I was overwhelmed, not having any idea how I was going to choose. I wanted one and then another and then another, but I kept looking back at Figures in a Landscape. Finally I stood in front of the big painting on the floor, looking down at the figures, the tender expression on their faces, the trees, the greens, and I said, “I think this one.” David said, “Good for you.” Nat remembers that when she looked at everything in the studio and pointed to Boston Street Scene, he was also clearly pleased and said, “Atta girl.”

I first saw the painting Shore Line on the driveway of Cragsmoor Inn. It and Bather with Towel came to me after David died, but Figures in a Landscape came to live with me in 1955. Over the years, I passed those paintings many times a day and stared into them across the living room in the evening and stood lost in front of them countless times. I will always miss them.

But somewhere there does exist a painting I didn’t lose in the fire, although not a painting of David’s. A few days after David died, Deedie and I were off doing some of the necessary errands, and we stopped by Dick and Phyllis Diebenkorn’s. The four of us settled in their living room for a few minutes, the feelings between us heavy with David’s death. A new painting sat on the mantel over the fireplace, leaning against the wall. I hadn’t seen it before. As I recall, the image was that of a seated figure in three-quarter view, a woman gazing into the distance. It was beautiful and I said so, and that I loved it.

Dick said, “Oh, well, look, take it. I’d like you to have it.”

I feared he might think I’d been hinting for a gift, and also I was overwhelmed. I said, “Oh my God, no, thank you, I couldn’t possibly.”

“But really, I want to give it to you.”

I couldn’t accept it. It was valuable, for one thing—undoubtedly worth six or seven hundred dollars. You can’t just accept a gift like that. I stammered my thanks and my love of the painting, and turned down the gift.

Fig. 107. Figures in a Landscape, 1955 Oil on canvas, 36 × 50 in. (91.4 × 127 cm.) Collection of Helen Park Bigelow Lost in fire

Fig. 108. Shore Line, 1952 Oil on canvas, 32 × 38 in. (81.3 × 96.5 cm.) Collection of Helen Park Bigelow Lost in fire

Fig. 109. Bather with Towel, 1959 Oil on canvas, 55 × 45 in. (139.7 × 114.3 cm.) Collection of Helen Park Bigelow Lost in fire

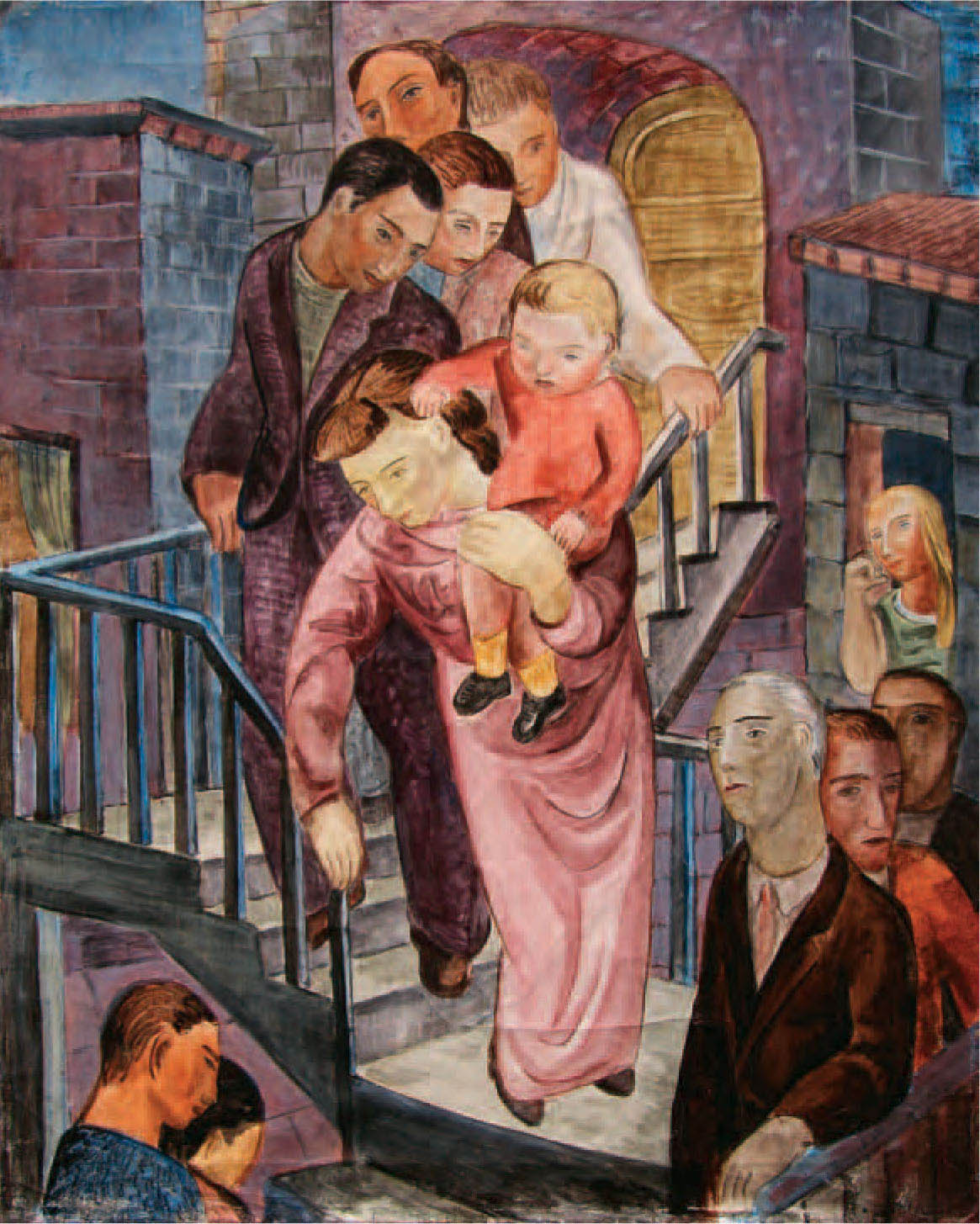

Fig. 110. Exodus (The Staircase), 1935 Oil on canvas, 31 × 25 in. (78.7 × 63.5 cm.) Collection of Helen Park Bigelow

Smiling a little sadly, Dick said, “Well, okay.” I realized he looked hurt. Conversation shifted, but something on Dick’s face told me, too late, that his offer was an expression of his grief and his loss of David. It was for David that he wanted to give me the painting. I understood, my heart ached, and I knew I had done the wrong thing.

The only thought that tempers this story is that because I turned down Dick’s gift, his painting didn’t burn up in my house, as it might have. And, this stroke of luck: At the time of the fire I was remodeling my living room and had limited wall space. I’d farmed three other paintings out to Nat and to a friend, and so those paintings were saved.

Shortly after my house fire, Edith Truesdell sent me a painting of David’s, one of the early works given to her in the 1930s. She sent it because of the paintings I’d lost in the fire. Within weeks, Jane Richardson Hanks, a lifelong best friend of Deedie’s and David’s and one of the trio of nude women at the mountain cabin, wrote and said she was giving me an early painting of David’s because my house burned down and I had lost some of his work.

When the second painting came, it was hard to believe what I saw. The painting was a reverse scene of the image given me by Edith. In one, Exodus (also sometimes titled The Staircase), people move somberly along a passageway and out of a building. A woman carries a child. Clothing is muted, in color and style. From an open window in the building on the side of the image, a girl with blond hair watches, elbow on the windowsill, head propped on hand.

In the other painting the girl is the only figure. It’s the same girl, the same pose, the same dress. Her hair falls against her arm in just the same manner. I don’t know which painting came first. Did David paint the scene in Exodus, become interested in the girl at the window, and then paint her? Or did he paint her first and then wonder what she was looking at, and then paint it?

These two paintings are unique. Nowhere else in David’s work does one character plainly appear on two canvases. Neither Edith nor Jane knew about the other painting. The two women barely knew each other and had not been in contact for decades. But at the same time they were both inspired, because of the fire, to give the paintings to me. And now the two works are reunited, hanging side by side, where otherwise their similarity might never have come to light.

When David died he left about three hundred paintings and drawings. I didn’t know then that they would become my life companions. That they would come to me, one by one, on pages of a catalogue or book. I didn’t know that for the rest of my life I would gaze at paintings like Couple (fig. 99) and see and feel my father’s profundity, or that his warmth and affection would glow from the canvas in a painting like The Patio (fig. 100).

Fig. 111. Girl in Window, 1935 Oil on canvas, 31 × 25 in. (78.7 × 63.5 cm.) Collection of Helen Park Bigelow

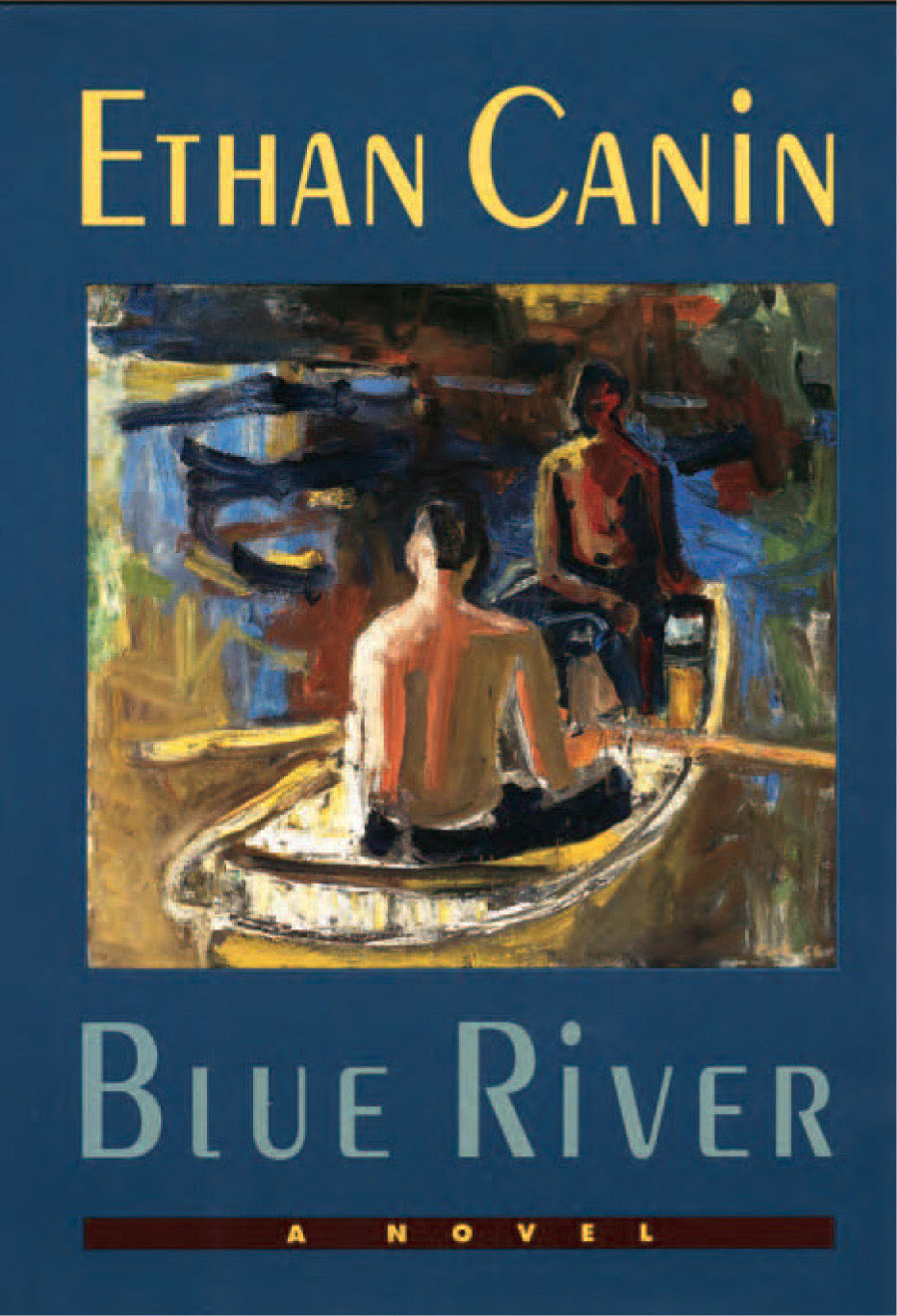

Since he died, certain moments or events suddenly come my way because of him, and they always feel like gifts from David. For instance, one day in 1991 I wandered browsing in a bookstore and there on a shelf, leaping out at me, was a painting of David’s on the cover of a new novel. The painting, Rowboat, is owned by the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. I didn’t know it had been chosen for a book jacket (following page). And the novel was by Ethan Canin, a writer I admire. I picked up the book and turned around and around in the store, wanting to tell everybody. I bought five copies, one for my sister, one for me, one for each of my kids.

Fig. 112. Book jacket, Blue River by Ethan Canin Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1991

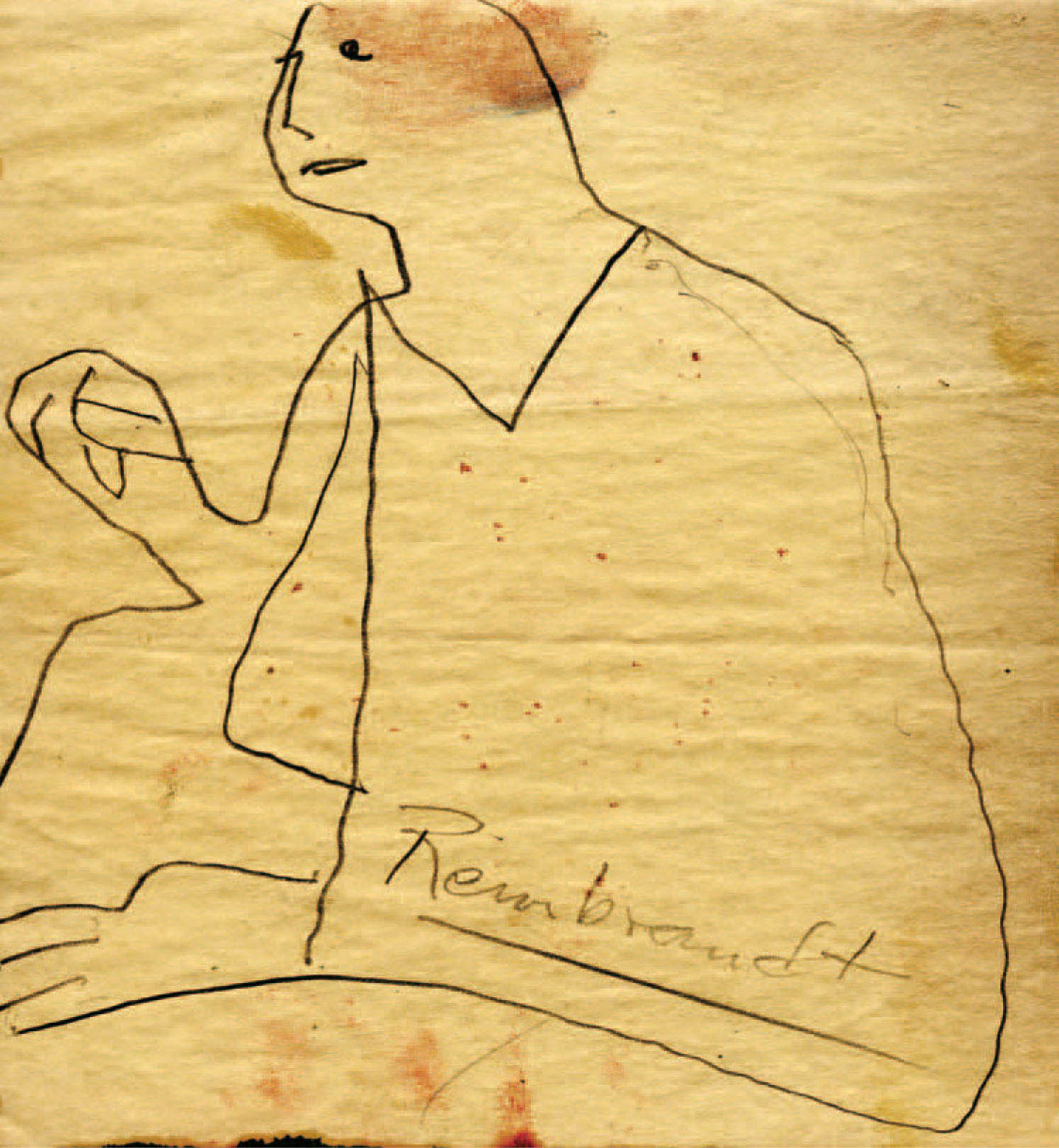

Another “gift” from David came one afternoon in the form of a message on my answering machine, a woman named Lu Vaccaro, calling from the Midwest. She and her husband, Nick Dante Vaccaro, had been students of David’s at UC Berkeley in 1959, during his last year of teaching. In a life-drawing class, David had a male model posing, and Nick was struggling with his drawing. Wearing a white lab coat over his trousers and shirt, David moved quietly through the maze of easels, murmuring with students about their work. He came up behind Nick, and the two men whispered about the issue in the pose that was being difficult. Lu said that David would never draw or paint on a student’s work. His method of illustrating a point was to take a small sketchpad from the pocket of the lab coat and quickly sketch the figure posing, focusing on the problem the student was having. He did this with Nick, and they talked quietly, pointing at the drawing and at the model. David slipped the pad of paper back into his pocket.

Falteringly, Nick asked if he could have the small sketch (fig. 113). David said, “Sure,” and took it out of his pocket. As David tore the drawing off its pad, Nick said, “And, do you mind, would you sign it?”

Looking surprised, again David said, “Sure.” He signed the drawing, folded it, and handed it to Nick, who stuck it in a book because David was again leaning over Nick’s drawing and saying something more about the pose. That evening, talking over the day’s events with Lu, Nick suddenly said, “Oh, wait, Mr. Park made a drawing.” He retrieved it from his book, unfolded it, and the two of them burst out laughing.

I have a vivid recollection of the evening in 1982 when I became older than my father. I was in the kitchen, and dinner simmered on the stove. Suddenly out of my drifting mind the arithmetic of months and years and days claimed my attention. Right then, stirring some pasta in a pot, I had been alive forty-nine years, six months, and three days—the length of David’s life. I put down my wooden spoon and looked at the clock. I was in Pennsylvania, East Coast time. More math: Right then, by ten or fifteen minutes, I was older than David. My pasta was ready to serve but I turned it off and stood staring out the window. Its panes were steamy from the cooking, and I stared past my own blurred reflection and into the night, lost in a moment I hadn’t thought of for years. Sometime in the early 1940s, when I was eight or nine, Deedie and David and Nat and I were at a sprawling villa that hugged a hillside above California’s Santa Clara Valley. Outside on a shaded patio, a party was taking place. In the hot, hazy afternoon I stood alone, looking at the view from the edge of the patio.

Fig. 113. Untitled (Classroom Sketch) 1959 Pencil on paper, 5½ × 4½ in. (14 × 11.4 cm.) Collection of Helen Park Bigelow

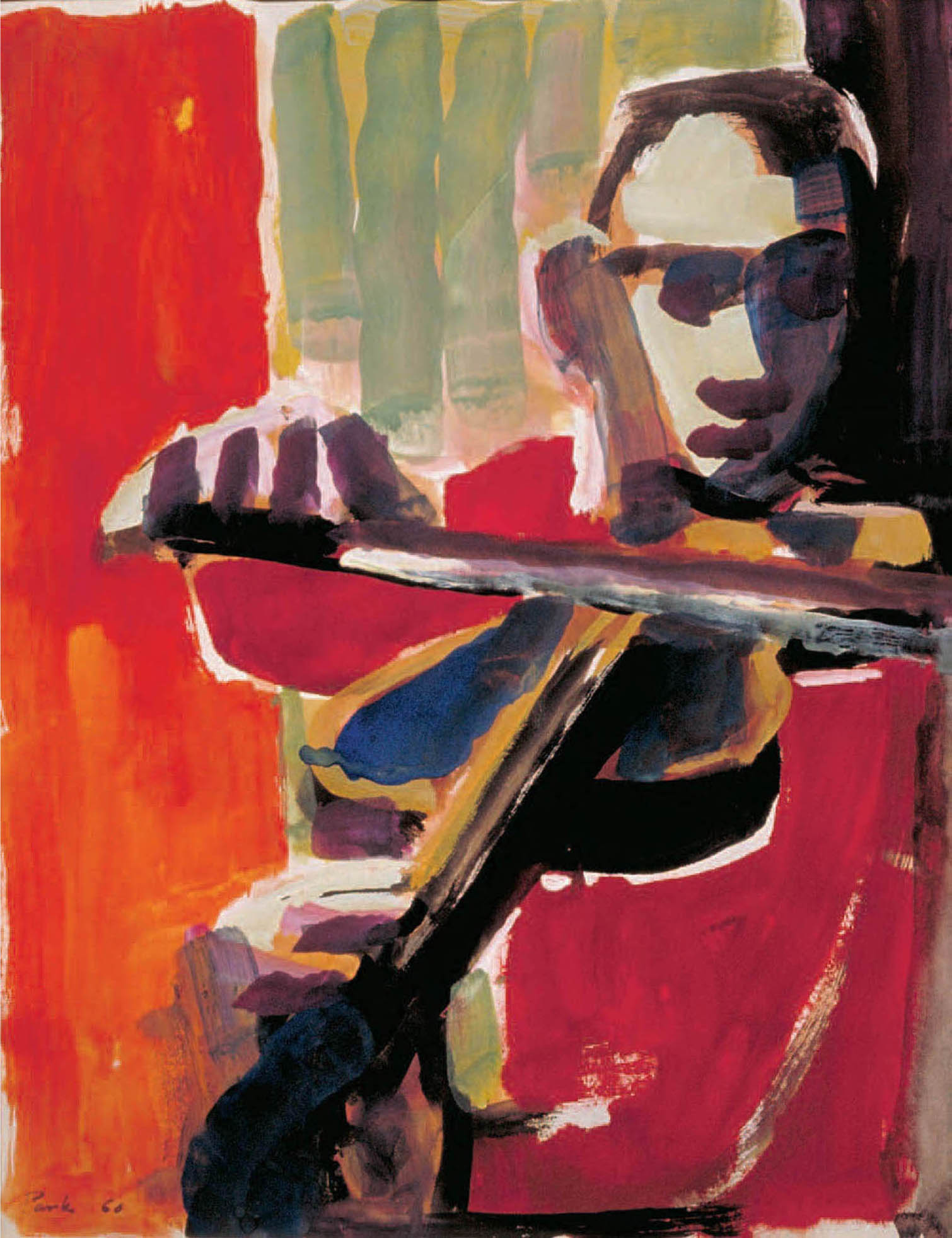

Fig. 114. Violinist, 1960 Gouache on paper, 14 × 11 in. (35.6 × 27.9 cm.) Private collection

Back then the floor of the Santa Clara Valley was covered with orchards. In my memory, the moment that followed lives in a vista of trees, in late-summer hazy light. Nearby, grown-ups stood or sat talking with each other, and from the house came the music of a violin.

Across the patio, David left a group of people and walked over to me. “Hear that?” he asked, nodding toward the house. It was perfect violin music, the way the violin sounds at a concert. I told David that, yes, I heard it, and we stood side by side listening and looking at the rounded mounds of orchard trees down in the valley below us.

“Beautiful,” David said. The view? The violin? I didn’t know, and it didn’t matter. Nodding toward the house again, David said, “It’s Yehudi Menuhin. He’s a houseguest here, and now all your life you will remember this, that you were at a party and you heard him practicing.”

I liked it that Yehudi Menuhin was practicing. Not performing but just being ordinary, a man doing what he had to do. Standing at my kitchen window all those years later, on the night when I realized I had been alive longer than my father, I felt deeply connected to all the feelings of that afternoon, just as David said I would: the shady light and all the trees and the violin music flowing into the air like rippling threads. But it is mainly the gift from David that lasts—the deep, proud pleasure as he came to stand beside me on a terrace and tell me something special, and then stayed there with me, listening.