But the difficulties which photography caused for traditional aesthetics were child’s play compared to those presented by film.

As cinema’s bandwagon—already heavy with reformers and trade journal reporters—rolled toward World War I, literary intellectuals, pundits, and other belletrists climbed aboard (sometimes climbing down again after their thousand words) just to see what the ride was like. Judging from the sharp spike in the number of film essays written between 1912 and 1914, it was apparently de rigueur to offer a learned editorial on the way modern life and culture found expression through this new phenomenon. Just as a range of opinions comprised the reformist discourse explored in

chapter 3, so the tone of this collection of articles, which Anton Kaes felicitously dubbed the

Kino-Debatte, extended from peevish outrage and haughty condescension to diplomatic concession or even roguish delight in the new medium.

2 This expansion of the discourse in Germany corresponded to cinema’s more visible public profile at this time, due to a stronger domestic film industry; the production of longer and more emotionally involving story films; the rise of film stars, such as Asta Nielsen and Henny Porten; the emergence of picture palaces and the successful “embourgeoisement” of the cinematic experience; and, most tellingly, the development of the

Autorenfilm, a short-lived strategy that attached literary and theatrical luminaries to industry projects.

3 Perhaps because those weighing in—including Ernst Bloch, Max Brod, Alfred Döblin, Georg Lukács, Kurt Pinthus, Walter Serner, and others—were or were to become such prominent names in the German literary tradition, this part of the conversation about film has received the most attention in secondary surveys of the period. We should be quick to note, however, that reformers and trade journal writers did not disappear during this time—on the contrary, they exerted a clear influence on the direction of the discussion, even if negatively—but the sheer number of new voices in the mix has tended to shift our attention from the pedagogical and commercial sections of the debate.

This chapter will be no different in that respect. It will, however, back away from the scholarly emphasis on the relation between literature and film. While depictions of the

Kino-Debatte have been as varied as the debate itself, scholars usually focus on the battle between image and word in the contemporary discussion of cinema’s relationship to German culture. It is indeed hard to ignore the incessant complaints about the supposed decline in literacy attributed to the consumption of sensational and superficial images rather than great literature or the many declarations that cinema could never be considered genuine art as long as it lacked words to express the depths of the human soul. Anton Kaes was absolutely correct when he noted that the tension between old and new “found expression in a vigorous discourse about the relationship between literature and cinema,” or, simply, that the debate about cinema was “a debate about the literature of the time.”

4 While theories of film started to disengage themselves from literary or theatrical models by the 1920s, before World War I, cinema and its champions felt the need to justify themselves in terms of literature. For Sabine Hake, literature was “the primary reference point” for writers coming to terms with modernity through their essays on cinema.

5 Peter Jelavich emphasized the attempts to conform film to “traditional bourgeois aesthetics, which demanded clarity of authorial voice and rootedness in the written word.”

6 Helmut Diederichs similarly charted the ways in which this group divided the ground between literature and film.

7 Stefanie Harris has demonstrated, on the other hand, how cinema’s unique form shaped the literary work of such writers as Kurt Pinthus.

8 As Heinz-B. Heller usefully pointed out, these were

literary intellectuals after all, so it comes as no surprise that their response to film would be from a position firmly grounded in their chosen medium.

9Focusing so closely on early cinema’s relationship to literary form and turf, however, unintentionally narrows our understanding of cinematic experience to that particular relationship, leaving relatively unexplored the question of film and aesthetic reception in general. The above quotation from Benjamin—his point that the challenge that photography presented to traditional aesthetics was “child’s play” compared with film—summarizes a fairly common conception: that film was emblematic of a change in aesthetic standards at the fin de siècle as mass reception and distraction replaced individual contemplation as the dominant or most appropriate mode of aesthetic reception. Indeed, in film and media studies this account is more or less taken on faith in Benjamin’s word alone. I have no argument with the general outlines of this story, but even his well-known “Work of Art” essay compresses the events considerably. So we have a dual historiographical problem, as I see it: the emphasis on the literary misses a large swath of the cinematic experience, specifically the relationship between viewer and image, while the leap from contemplation to distraction in film history and theory is too often taken for granted without spelling out the character of “traditional aesthetics” and the transition to whatever replaced it. This chapter argues that a close, renewed examination of the

Kino-Debatte is essential to solving both historiographical problems.

Previous chapters were concerned with the criteria for film’s legitimacy within any given discipline and the adaptability of motion picture technology to an expert mode of viewing as a major factor in establishing that legitimacy; this chapter will explore film’s legitimacy within the realm of aesthetics and its degree of adaptability to the expert mode of viewing known as aesthetic contemplation. It presumes that, following a trend in German aesthetics since Kant, the question of aesthetic value hinged on

reception more than form. That is, the major statements on aesthetics in the long nineteenth century—especially those of Kant, Schiller, Schopenhauer, and others, but excluding those within the Hegelian tradition, which was concerned with how meaning inhered in form rather than how we experienced it—were concerned primarily with the role of aesthetics as a way of being in the world, more than whether any particular form was more artistic than another. They were concerned with the function of art within a moral, ethical, social, and philosophical system. The value and legitimacy of art in this system depended primarily on the singularity of the experience it aroused. The exact nature of that experience has been a topic of constant exploration since these statements, but the significance of that experience for the system in general—whether philosophical, moral, or political—cannot be underestimated. Form prompts experience, to be sure, but these and other statements emphasized the universal character of the aesthetic experience rather than the variety of experiences created by various forms. More often than not, evaluations of any given form, such as music, rested on the ability of that form to catapult the reader/listener/viewer into a particular kind of aesthetic experience. Better experience usually equaled more hallowed form.

So to understand fully the relationship between early cinema and aesthetics, we must focus on the relationship between the cinematic experience and aesthetic experience as it was understood, or between watching movies and the expert mode of viewing called aesthetic contemplation. This chapter asks the following questions: to what extent did the cinematic experience, as these authors described it, conform to their understanding of aesthetic experience? Specifically, how did the experience of film align with their understanding of aesthetic contemplation as an implicitly expert mode of viewing? To what extent did the descriptions of cinematic experience participate in changes to expert conceptions of this mode of viewing?

To answer these questions requires first understanding what the authors presumed about aesthetic experience. The trouble with aesthetic experience, of course, as countless analytic philosophers have complained, is its notoriously slippery surface. It is very difficult to define logically, or even on an individual basis. Fortunately, for the purposes of this project we need not come to a philosophically rigorous conclusion; instead, we need only outline what the authors thought aesthetic experience was. Even that is elusive, because any given writer borrowed ideas or presumptions, often haphazardly, from a long and varied aesthetic tradition. Indeed, we might find it more historiographically productive to think of descriptions of aesthetic experience (rather than aesthetic experience per se) as statements often expressing competing values. If one writer latched onto Kant’s idea of disinterest and detachment as the point of aesthetic experience, another might champion, after Schopenhauer, the idea of losing oneself in the artwork. If one author saw repose as the fundamental criterion of any aesthetic encounter, another might have emphasized the value of the free play of associations while engaged with a work of art. My point is that these key ideas or terms—detachment, loss of self, repose, free play, and others—describing any aesthetic experience (not just cinematic) functioned within a system of implicit dichotomies. Let me explain.

If we gather common ideas about the nature of aesthetic experience in the major statements of Kant, Schiller, Schopenhauer, and others within the tradition of nineteenth-century German aesthetics, it appears that aesthetic contemplation entailed (1)

detachment or disinterest, meaning that aesthetic judgment is without desire, passion, or self-interest; (2)

repose, in that the object is lingered over without haste, giving enough time for the free play of the imagination;

10 (3)

activity, meaning that the mind is alive with associations and correlations; and (4)

loss of self, in that the contemplation of the object can lead to either a transcendental immersion into the object (Schopenhauer) or a moment of awareness of one’s participation in a larger community (Kant). Under this category we can also subsume discussions about the role of the body in aesthetic experience; for some, aesthetic contemplation was a purely mental operation; others looked to the body as a model for understanding aesthetic pleasure, while avoiding the purely sensual. Some terms are mutually reinforcing (disinterest and participation in a community, for example), while others are contradictory (detachment and immersion seem to be opposite ideas).

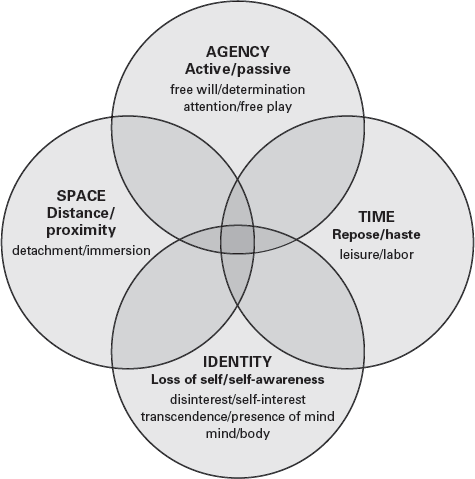

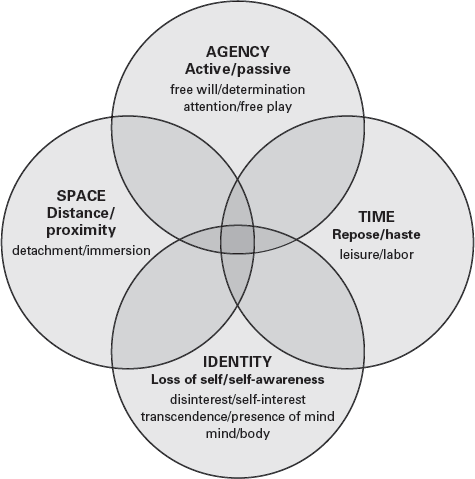

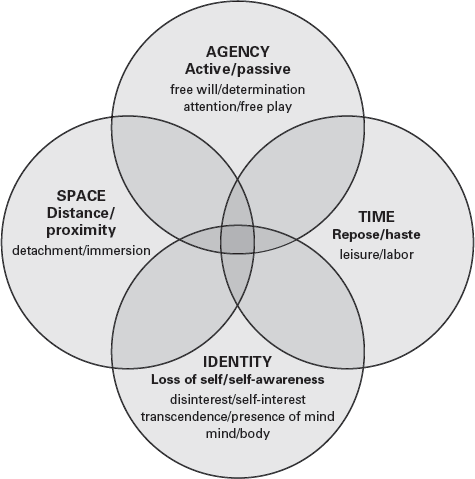

But we can arrange these terms—detachment, repose, activity, and loss of self—into spheres or larger categories that also contain their opposites. These categories are:

space (distance/proximity or detachment/immersion),

identity (loss of self/self-awareness),

time (repose/haste), and

agency (activity/passivity or free will/determination) (see

fig. 4.1). This arrangement shows especially clearly the

ideological implications of these terms and of the descriptions of aesthetic experience they evoked. That is, to give aesthetic experience its moral or philosophical weight within a larger system—the pivotal role of Kant’s

Critique of Judgment with regard to his other

Critiques comes to mind—the terms writers and philosophers used to describe aesthetic experience were rhetorically linked to fundamental ideological values (or ideologically inflected categories of experience) such as agency and identity. Understanding the rhetorical role these terms played allows us to glimpse the stakes of any historical debate regarding aesthetic experience. Pairing the terms with their opposites also underlines their mutual dependence in those historical debates.

This scheme also allows us to escape the analytic philosophers’ futile attempts to logically reconcile descriptions, an evasion much more in keeping with the sharpest understandings of aesthetic experience as indeterminate. Schiller argued, for example, that the aesthetic state is a

mediating moment “midway between matter and form, passivity and activity,” wherein indeterminacy is the preferred state of being.

11 Accepting the indeterminacy of the aesthetic state should turn us away from pat definitions and toward an understanding of aesthetic contemplation as dichotomous, fluid, oscillating, or unfixed. (Again, I want to stress that questions about what the aesthetic state actually is and even whether it exists are irrelevant when considering historical descriptions of it.) For example, descriptions of contemplation almost always preferred repose over haste—thereby presuming that both the object and the subject were more or less in a state of stillness—but the quick, gestalt-like expert glance over the artwork as a whole was not ruled out as part of the process.

12 However, detachment was almost a universal feature of these descriptions, so its opposites, self-interest or passion, were hardly ever included as viable elements of the experience.

13 On the other hand, descriptions of the aesthetic experience often oscillated between sides of a dichotomy: claims that emotional detachment or psychic distance were crucial to aesthetic experience (Kant, Schiller) must be balanced or reconciled with descriptions that emphasized emotional projection or immersion into the artwork (Schopenhauer, Adolf Hildebrand). Likewise, the relationship between active and passive stances in aesthetic experience is often unclear from the descriptions; mastery alternates with surrender (as in many descriptions of the experience of the sublime), while focused attention alternates with the free play of associations or loss of self in the experience. This approach, then, matches a theoretical understanding of aesthetic experience as indeterminate to a historiographical scheme that does not try to resolve contradictions but allows them to stand to highlight their ideological function.

Obviously these categories overlap; questions of agency and identity are indeed hard to separate. But that is precisely the point: the overlapping conceptual categories strengthen the ideological weight of any given description. So this scheme might be useful for an investigation of any historical description of aesthetic experience; it is definitely useful to understanding the early debates about motion pictures. To summarize, viewing the historical claims for aesthetic experience in terms of a series of dichotomies, rather than as a series of firm characteristics, has three advantages. First, we avoid the futile philosophical debate about what the aesthetic experience actually is and replace it with the recognition that historical descriptions of aesthetic contemplation—what writers and aestheticians thought it was—have been varied and contradictory, but not infinitely so. Second, by subsuming the dichotomies under the general categories of identity and agency, we emphasize that most philosophers (in the neo-Kantian tradition) recognized aesthetics as a moral category that mediated between opposite poles of their choice. For example, the Kantian/Schillerian tradition of putting Art between Reason and Sensuality extends in spirit to at least Theodor Adorno, if not also Jacques Rancière and other contemporary philosophers who hope to find for Art a place apart and some emancipatory potential. Seeing the aesthetic experience as a series of unstable dichotomies recognizes not only Art’s socially mediating function but also that historical descriptions of aesthetic experience emphasized its productive indeterminacy.

Finally, with regard to this specific project, these dichotomies allow us to see more clearly how the discussion of motion pictures was ultimately an

aesthetic debate, in the sense that these essays on cinema may be about the status of literature, the content of the films, or whatever, but the core issue was the larger ideological problem of

the moral significance of the aesthetic experience. These writers obviously cared about the decline in reading skills, about the loss of ability to concentrate, the superficiality of the mass audience, the novelty of the moving image, and many other things that may or may not have indicated the decline of civilization. But, at bottom, all these complaints can be traced to the

character of the aesthetic experience, which apparently mattered most to these writers. “Film presentations are generally rejected from an artistic perspective,” wrote Emilie Altenloh about the taste of the upper classes.

14 While Altenloh undoubtedly refers to judgments of artistic

form (“von

künsterlischen Gesichtspunkten”), this chapter agues that complaints or judgments of form were ultimately in the service of a better aesthetic experience. Modernity was therefore an affront to their aesthetic sensibilities and values, which were rooted in a philosophical tradition that privileged a particular, expert mode of viewing a stationary image or object. The extent to which cinema challenged or could be accommodated to these values is the question of this chapter.

To burrow further, we could argue that these dichotomies grew out a more fundamental, historical division between active and passive viewers. As we have seen, film spectators were often characterized as hypnotized by the cinematic image, even addicted to it, and captivated by the ease with which it entered the stream of consciousness, while cinema’s fragmented temporality, quick pace, and motley form matched the habits and psyche of the modern city dweller, who was at once impatient and distracted, unable to concentrate on a single, main idea. Hence movies were perceived as effortless, whereas real art required work; movies were a jumble, whereas real art had a distinct form; movie spectators needed their next film like a drug, while real art encouraged a detached observer; movies moved by far too quickly, disallowing the continuous, leisurely attention required of real art. If these sets seem familiar, it is partly because they have been repeated over the centuries whenever audiences are described; theater audiences were probably the first victims of such characterizations.

15 Rancière’s explanation of the paradox of spectatorship sheds some light on this issue:

There is no theatre without a spectator…. But according to the accusers, being a spectator is a bad thing for two reasons. First, viewing is the opposite of knowing: the spectator is held before an appearance in a state of ignorance about the process of production of this appearance and about the reality it conceals. Second, it is the opposite of acting: the spectator remains in her seat, passive. To be a spectator is to be separated from both the capacity to know and the power to act.

16

The idea of aesthetic contemplation from Kant and Schiller to early twentieth-century professional aestheticians looks like a deliberate attempt to counter the problem of passivity in spectatorship by endowing the viewer with both a protocol and a philosophical justification that connect aesthetic enjoyment to reasoning and knowledge production (“the capacity to know”), on one hand, and political maturity or citizenship (“the power to act”) on the other. Endowing aesthetic contemplation with agency and linking it to individual or civic identity gave this mode of viewing the moral weight it needed to counter a mode of viewing perceived to be common to the passive, irresponsible crowd. The contemporary discussion of the cinematic experience could not avoid confronting this weighty connection between agency and contemplation—often to film’s disadvantage.

Precisely because contemplation had long been endowed with high moral import—with values such as reason and citizenship—any changes to the conditions of contemplation put these values at risk, especially as mass reception became more common with new urban demographics and forms. If cinema were not at the heart of these transformations, for many essayists it was a worst-case scenario. At the same time, however, the discussion about cinema was not merely a reactionary defense of Enlightenment-era ideals; it was a collective attempt to find some common ground, to ask (often implicitly) whether contemplation was the proper way to engage with these new forms, and if not, what was? In fact, Benjamin’s own position on the relative value of contemplation and distraction was not limited to his words in the “Work of Art” essay. As Carolin Duttlinger has shown, Benjamin’s conception of attention (

Aufmerksamkeit) played a central and complex role from his earliest essays, and if he advocated distraction (

Zerstreuung) as the perceptual stance most appropriate toward modernity in the “Work of Art” essay, that was only one part of a long conversation he had with himself about the relationship between a mode of viewing and one’s position toward and within modern life.

17 Ultimately, this conversation was about the relationship between “a way of being with images,” in Dudley Andrew’s ingenious phrase,

18 and a way of being in the world. For Benjamin as well as the writers of the

Kino-Debatte decades earlier, the two stances were one and the same.

So this chapter will explore the status of aesthetic reception in the context of discussions about cinematic spectatorship. The first section will trace the broad themes in the

Kino-Debatte about movies, modernity, and spectatorship in relation to the rhetorical or ideological categories of time and agency. Through an examination of Schiller and Schopenhauer, it will stress the philosophical and subsequently ideological connection between temporality, indeterminacy, and aesthetic experience, and how this constellation persisted in the descriptions of early cinema. The second section will inspect discussions of aesthetic experience in professional aesthetics of the time, especially around the concept of

Einfühlung, or “feeling into” the artwork. These discussions about the relationship of emotions and the body to aesthetic experience were attempting to come to grips with, on one hand, unresolved ideas about reception in nineteenth-century aesthetics, and on the other, modern aesthetic reception characterized by turn of the century democratic access to art. This section will demonstrate that discussions of the cinematic experience also pressed on some of the same troubling issues—such as emotional projection, immersion and detachment, and visual pleasure—regarding the nature of aesthetic contemplation in the modern world that professional aestheticians discussed. This section explores the categories of space and identity. The third section focuses on Georg Lukács’s famous early essay on film, “Thoughts Toward an Aesthetic of the Cinema” (1913), to demonstrate the nascent political critique of contemplation that was to be such a central feature of his and other theorists’ stance after World War I. This final section will also return to Benjamin, Siegfried Kracauer, and the discussion of contemplation and distraction to realign our history of these theories in light of the

Kino-Debatte’s discursive construction of spectatorship.

The scheme outlined above could apply to any historical description of aesthetic experience after Kant, but this section will recast some familiar themes in the

Kino-Debatte in terms of the roles time and agency played in contemporary understandings of aesthetic experience. Let us begin with a relatively obvious case: motion pictures as an emblem of social acceleration. This was a bright, visible thread in early debates about cinema all over the world. Basically, commentators complained that the incessant tempo of motion pictures—its relentless push forward and its quick change from one view to the next—exemplified the problems of modern social acceleration.

19 Educator Georg Kleibömer discussed cinema’s pace at length in his 1909 essay, “Cinema and Schoolchildren.” He opened his attack by describing the Great Lisbon Earthquake’s profound effect on young Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, and then wondered whether the eruption of Mount Pelée in 1902 had the same effect:

And let us search for just one child for whom this natural event had an indelible significance. How is it that we all well know that this search will be in vain? Because in our time all the world’s grand strokes of fate are immediately known to us in every detail; because one harrowing incident displaces the other before it can be “worked over” by our mind. Now even the most tragic events only touch the surface of the soul.

20

Superficiality abounds, according to Kleibömer, because we do not have enough time to absorb the emotional significance of events before we are compelled to move to the next one. “The moral education of a child,” he instructed, “should include a few events that give him an understanding of certain emotional values,” but “above all, such emotions must not confront other feelings in close temporal proximity.” And in the cinema? “In rapid succession jest and seriousness alternate on the screen, since variety must reign…. So first horror, fear in the highest degree, then compassion increased to the utmost.” He therefore criticized “the danger that this rapid traversal of the entire scale of feelings poses for the truth and depth of children’s emotions.” Kleibömer saw filmic form as a synecdoche for the rapidity with which modern information was conveyed; he assumed that because of that rapidity, children could not absorb the significance of events, and this was the root cause of their perceived superficiality (as opposed to, perhaps, the possibility that they were six-year-olds not named Goethe).

Kleibömer was not alone in his opinion; writers of all sorts, not just cranky reformers, connected movies and modernity in this way. Austrian author Karl Hans Strobl similarly argued, “The cinema is one of the most perfect expressions of our time. Its hasty, erratic tempo corresponds to the nervousness of our lives; the anxious flickering, the whisking away of its scenes is the extreme opposite of a measured, regular stride, of confident persistence.”

21 In the pages of

Der Kinematograph a commentator noted matter of factly, “And so the cabaret, with its indiscriminate, democratic disposition, appeals best to the nervous haste and variety of our time, which of course is not say that the theater is doomed. But now the cinema, the projection house, successfully competes with the cabaret for the affection of the people just as the latter surpassed the legitimate stage.”

22 Right-wing editor of

Der Kunstwart and proto-Nazi Wilhelm Stapel was even more explicit:

Because of the rush of images, you get used to absorbing only an approximation of the impression; you do not get a clear and conscious understanding of the image in its details. Therefore only the coarse, surprising, sensational impressions stick. The sense for the intimate, the precise, the delicate is lost. The patrons of the cinema “think” only in garish, vague ideas. Any image that lights up their mind’s eye takes up all of their attention; they no longer mull and reconsider it, they no longer indulge in the particularities and the reasons.

23

Devotees of the connection between early cinema and modernity will find this theme familiar. Noteworthy, however, is not simply this well-known correspondence but the strong implication that cinema’s tempo interfered with the usual aesthetic experience of viewing images. Stapel was very clear in this regard: the spectator does not “get a clear and conscious understanding of the image in its details…. they no longer mull and reconsider it.” If one is to understand the image, one must attend to the details slowly. Now this could just be a commonsensical caution that one cannot simultaneously do anything hastily and well, but it was not usually put in those terms. Instead, the complaint was specifically about the superficiality that results from processing (or being forced to process) visual imagery too rapidly. What was the connection between viewing tempo and shallowness?

To appreciate the moral implications of this equation, we must return to Schiller and Schopenhauer, who based their philosophies on a common understanding of time. The importance of temporality for Schiller’s aesthetics is not only rarely discussed, it is key to understanding later ideological objections to film. So the following will explicate their aesthetic schemes while emphasizing temporality and indeterminacy, which will clarify certain aspects of the debates about cinema. Even if these early nineteenth-century philosophers were in many ways considered obsolete by the early twentieth century, their ideas about the moral and cultural importance of aesthetic experience—and the relationship between that significance and the passing of time—were widely and implicitly assumed. Schiller, especially, presumed that everyday, sensuous existence is necessarily tied to the inexorable succession of moments, while abstract thought and reason—or the Platonic idea—exist outside this temporal course in a timeless, static, changeless existence. Schiller called our animal nature the “sense drive” and the spiritual or intellectual side of our existence the “form drive.” He described the sense drive:

Since everything that exists in time exists as a succession, the very fact of something existing at all means that everything else is excluded…. when man is sensible of the present, the whole infinitude of his possible determinations is confined to this single mode of being. Wherever, therefore, this drive functions exclusively, we inevitably find the highest degree of limitation. Man in this state is nothing but a unit of quantity, an occupied moment of time—or rather, he is not at all, for his Personality is suspended as long as he is ruled by sensation, and swept along by the flux of time.

24

Here and elsewhere, Schiller defined his understanding of the different facets of human existence in terms of their relationship to time. In the sense drive, one is nothing but “an occupied moment of time”; by being occupied by (in terms of both concerned with and controlled by) sensuous existence—ruled only by needs and desires of the moment—one is “swept along by the flux of time.” This conception of temporality, for Schiller and others, implied a limit on human potential: “Wherever, therefore, this drive functions exclusively, we inevitably find the highest degree of limitation.” The form drive, however, “embraces the whole sequence of time, which is as much as to say: it annuls time and annuls change. It wants the real to be necessary and eternal, and the eternal to be necessary and real” (81). Ideas aspire to timelessness, being outside of the succession of events and therefore outside of perception. Reason is timeless, in Schiller’s scheme, but also ethereal. So Schiller invented another motive force to harmonize, balance, or counter the other two:

For as long as he only feels, his Person, or his absolute existence, remains a mystery to him; and as long as he only thinks, his existence in time, or his Condition, does likewise. Should there, however, be cases in which he were to have this twofold experience simultaneously, in which he were to be at once conscious of his freedom and sensible of his existence, were, at one and the same time, to feel himself matter and to know himself as mind, then he would in such cases, and in such cases only, have a complete intuition of his human nature. (95, emphasis in original)

For Schiller, the desiring, physical side and the spiritual, intellectual side of our nature have their limitations, but when we are able to experience both at the same time we are without limitations. That is, if our lopsided, specialized existence is determined by our physical desires (that is, as matter without form), or by our intellectual aspirations (that is, form without matter), then the third way escapes determination entirely; it is indeterminate. Schiller called this third mode of existence “the play drive,” which is exemplified by aesthetic experience. It is a moment of indeterminacy, of oscillation between Sense and Reason, or between physical necessity and law. That moment of indeterminacy holds the greatest human potential, when free will is exercised most productively in the service of “a complete intuition of [our] human nature.” Schiller concluded:

Our psyche passes, then, from sensation to thought via a middle disposition in which sense and reason are both active at the same time. Precisely for this reason, however, they cancel each other out as determining forces, and bring about a negation by means of an opposition. This middle disposition, in which the psyche is subject neither to physical nor to moral constraint, and yet is active in both these ways, pre-eminently deserves to be called a free disposition … we must call this condition of real and active determinability the aesthetic. (141, emphasis in original)

The exercise of free will, then, is the goal of aesthetic experience. But not entirely: the goal is to be “sensible of existence” without being determined by it; to be aware of all aspects of our nature while they are held in abeyance. Aesthetic experience is a balancing act between physical necessity and moral obligation, actively taking part in both sides of the human condition without letting either determine us. Schiller thereby gave the aesthetic experience a strong ethical charge; it serves as the moment when we are most fully human, overly determined by neither of our natures: “For, to mince matters no longer, man only plays when he is in the fullest sense of the word a human being, and he is only fully a human being when he plays” (107, emphasis in original). For Schiller, aesthetic experience was the grandest kind of play, which brings our fullest human potential into relief.

Especially interesting and rarely noted, however, is the emphasis Schiller placed on the temporal dimension of this experience. The sense drive is “swept along by the flux of time,” the formal drive “annuls time,” but the play drive is repeatedly described as an experience of simultaneity: “a middle disposition in which sense and reason are both active

at the same time.” The importance of simultaneity in his scheme marks Schiller’s move as a very modern gesture; both simultaneous and indeterminate (“this condition of real and active determinability [

Bestimmbarkeit]”), his category feels very modern indeed. It is not too great a leap to argue that simultaneity creates this indeterminacy; we are both in and outside of time, which puts us in a position of being in neither one drive nor the other, but both states at the same time. This clarifies his formulation of the play drive: “the play-drive, therefore, would be directed towards annulling time

within time, reconciling with absolute being and change with identity” (97, emphasis in original). The annulment of time experienced in the formal drive is reconciled with the experience of time within the sense drive, thereby resulting in the “annulling time

within time.” Whatever one makes of the validity of his interpretation, there can be no doubt that Schiller’s conception of the aesthetic experience was ultimately temporal.

Schopenhauer also took pains to underline the temporality of the experience, even if it was different from Schiller’s: “It is the state where, simultaneously and inseparably, the perceived individual thing is raised to the idea of its species, and the knowing individual to the pure subject of will-less knowing, and now the two, as such, no longer stand in the stream of time and of all other relations.”

25 Both subject and object are raised to a transcendent state in Schopenhauer’s conception of contemplation, during which the object becomes an idea and the subject loses itself and its desire in the process, thereby also finding temporary relief from the misery of longing and striving. The emancipatory potential of aesthetic experience derives from its ability to provide a momentary escape from time; this is different from Schiller’s more moral and community-oriented aesthetics, but it affirms rather than cancels Schiller’s conception of the aesthetic as a primarily temporal experience. For both philosophers, and in the most common conceptions of aesthetic experience in the long nineteenth century, human limitation was tied to “the flux of time,” and its emancipatory potential was linked to the escape from that flux or being able to maintain a balance between competing temporalities.

This review of Schiller’s and Schopenhauer’s philosophies is necessary, because it reminds us of the

ethical or moral mission they assigned to aesthetic experience, thereby giving it an ideological weight that it carried through the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. It also establishes

the importance of time within traditional aesthetics, especially the notion of repose in the aesthetic stance. Finally, it emphasizes that Schiller and others calibrated their conception of contemplation to highlight its

indeterminacy, or more precisely, the importance of the indeterminate quality of the aesthetic experience as an emblem of human liberty. All of these features of aesthetic experience—especially the focus on experience, rather than artistic form—spread and took root in everyday understandings of aesthetic issues that we see in the

Kino-Debatte and other, early discussions about viewing motion pictures. Again, the goal is to demonstrate that these debates were largely discussions about aesthetic (as opposed to narrowly literary) experience, especially this model of contemplation, to which modern spectatorship was detrimentally compared. Indeed, the unfavorable comparisons functioned primarily as a defense of contemplation’s ideological value. We could dismiss the comparisons out of hand as ideologically compromised, but we would lose the deeply ambivalent and complex character of aesthetic reception. Contemplation was not yet dead; whether the values associated with it actually ever died is still open to question.

Those values were primarily ethical in imperial Germany. Modernity, it appears, was too pushy; it shoved its spectators along, giving them no pause for reflection, which was an offense to values of repose. So when writers such as Gaupp, Sellmann, Stapel, Strobl, or others noted the potential effect of the fast pace of movies and modernity, they were not simply complaining about the vapid superficiality of “kids these days”; they were defending a very long tradition that insisted on leisurely approaches to the image. To allow oneself to succumb to the “flux of time” while attending to an image—or to let the image impose such limitations—was an abdication of the duty to self-cultivation, of the obligation to become fully human. Contemplation was depicted as a moment of escape, but also a moment of self-awareness; the aesthetic experience had a special place in state and cultural self-conceptions in Germany, which the righteous defended vigorously.

26 But because of its pivotal role between emancipation, civic duty, and self-awareness, contemplation represented a complex, ambivalent stance toward the world that was not so easily dismissed, as Benjamin recognized (and which I will discuss at greater length later in the chapter).

Another good example within the discussion concerns the fragmentary, disjointed quality authors attributed to modern life and to cinema. If movies and modernity were too pushy and quick, they were also disjunctive: the cinema “is short, rapid, even encrypted, and it stops for nothing. There is something compact, precise, even military about it. This fits very well with our age, an age of extracts.”

27 These comments on form were often framed as an analogy between movies, modernity, and the mind of its spectators; modern life was disordered, as were movies and the thought processes of its audience. This homology—a discursive construction of film’s spectator—was usually an implicit defense of aesthetic ideals of detachment and effort. Theater critic Hermann Kienzl’s brief commentary is exemplary:

The psychology behind the triumph of cinema is urban psychology. Not only because the metropolis is the natural focal point from which all social life radiates, but especially because the metropolitan soul—this inquisitive and inscrutable soul perpetually on the run, stumbling from one fleeting impression to the next—is really the soul of the cinema! Indeed, some city dwellers even lack the stamina and concentration for mental and emotional absorption—and probably also the time, especially in Berlin, a metropolis agitated by work-fever. The same trivial drive for relaxation that leads city dwellers to the operetta or farce after work to replenish their exhausted energies leads them likewise to seek the effortless pleasures offered by movie theaters.

28

Here we have the usual stereotypes about the metropolis and its inhabitants: they are driven by passion, desire, necessity; their actions are hurried and jumbled. Needless to say, these were also transgressions against the aesthetic values of detachment and repose. Kienzl pretended to offer merely a description of the situation, but it was an implicit defense of the principles outlined earlier.

There is also the implication, well before Hugo Münsterberg, that movies were popular and effective because they somehow mimicked the structure of the modern mind, or at least the mind of its audience. For many commentators, the link between movies, modernity, and mind made film “the most psychological representation in our time.”

29 The “effortless pleasures” of the cinema replenished the modern soul in a way—a trivial way, they would say—that other entertainments could not. Most writers disparaged movies and the mind of the masses in a dual dismissal, but others saw it differently:

Only film technology permits the rapid sequence of images that roughly corresponds to our own imaginative faculty and in some measure imitates its jerky unpredictability [

Sprunghaftigkeit]. Part of the fatigue to which we finally fall prey while watching theatrical works of art results not from the noble effort of aesthetic enjoyment, but rather from the exertion in adapting to the plodding, affected movement of life on stage. Spared this effort in the cinema, one is free to devote a considerably more uninhibited commitment to the illusion.

30

Whereas Kienzl and others assumed that the mind of an intellectual is ordered and disciplined, Lou Andreas-Salomé concluded, after spending a year with Sigmund Freud and Viktor Tausk, that the mind is no such thing. When Kienzl remarked that “city dwellers lack the stamina and concentration for mental and emotional absorption,” he compared the stalwart literary mind with the flighty, disordered, lazy mind of the moviegoer. But Andreas-Salomé acknowledged that movies moved quickly and disjunctively, which matched her understanding of the “imaginative faculty.” This put both in a favorable, or at least neutral, light. Indeed, her sympathetic view of cinema’s aesthetic potential depended on this structural similarity; the speed at which we think—slowed down considerably by theater—was matched only by cinema. Likewise, she saw in early cinema’s unpredictability—we can imagine that to early, novice audiences the continual surprise at the next view might have given them the impression that film narrative or editing was capricious (which it sometimes was)—a disconnectedness that fit her understanding of human thought. Actually, the primary difference between her idea of mind and Kienzl’s was that she refused to create two models divided by class, one for elite intellectuals and one for the mass audience. Her model assumed that, when it comes to thinking, we are all a hot mess, trained or not. Münsterberg also developed a single model, but presumed that all our imaginative faculties are well ordered. In any case, many authors assumed a structural similarity between movies and mind, but their aesthetic judgment depended on whose mind movies resembled.

But Kienzl and Andreas-Salomé shared one assumption: true art required effort and movies were effortless. The “noble effort of aesthetic enjoyment” was a persistent trope in these and other discussions about the difference between high and low cultural forms, in which high art was usually differentiated by its complexity or difficulty and low art by its simplicity. For Andreas-Salomé, cinema’s effortlessness was a result of its structural similarity with the mind, especially with regard to its motion and pace. It had also something to do with the age-old comparison of images and ideas, a comparison common to the

Kino-Debatte, too, as when Hermann Duenschmann, apparently a big fan of Gustave Le Bon, compared the film audience with a crowd: “The crowd thinks only in images and can only be influenced through images that act suggestively on their imagination.”

31 This implied that the learned think in words, but the visual status of ideas has always been ambiguous. At least since Descartes, many philosophers have defined “ideas” as images, not words. Descartes consistently made the analogy that ideas are “like portraits drawn from Nature.”

32 Or Locke, in his

Essay Concerning Human Understanding, wrote that ideas are “Pictures drawn in our Minds,”

33 or that the “Idea is just like that Picture, which the Painter makes of the visible Appearances joyned together.”

34 Now an important caveat here is that Descartes and Locke were thinking not of concepts, but of sensory ideas—the images that our brain creates from the sensory information gathered by normal perception.

35 But the leap to concepts is not too hard to make and has been made since Plato, perhaps. The point is that one support for this notion that films were “effortless” was the isomorphism between images and the way the mind is thought to work. (This was also a support for the assumption within discussion about educational media that visual instruction is more efficient than instruction with other kinds of materials.)

Yet images per se cannot be easier to comprehend; otherwise the aesthetic contemplation of paintings would have no pedestal upon which to place itself. So there must have been something other than the similarity between images and mind that supported the claim that movies were effortless. Ulrich Rauscher gives a clue: “I fear the cinema has one disadvantage for the audience: because it tells its story so comfortably, because it takes over the operations of sense-making itself, the cinema, which could foster the creativity of our literati, will bring about a general laziness of the public’s imagination.”

36 Film is effortless, because it “takes over the operations of sense-making itself” (

weil er die Versinnlichung der Vorgänge selber übernimmt) for the audience, leaving nothing for the imagination to work on. The “noble effort” of aesthetic enjoyment was perceived as the free play of associations that accompanied a productively ambiguous artwork; the imagination filled in interpretive gaps with its own associations, thereby bringing subject and object together as the hermeneutic circle between part, whole, and subject tightened. Just as photography was not considered legitimate aesthetic material because of its mechanical nature and its excessive detail—which left nothing to the imagination, presumably—so, too, motion pictures were dismissed because their detail and their narrative patterns left the viewer nothing to do but watch. There was more to it than that, however, because these same movies were disdained for their chaotic, confusing stories, which doubtless would leave much to the imagination. The problem, then, was that the succession of images was not merely obvious, but

preordained. Whether the images were confusing or crystal clear, they were always

someone else’

s images, and if we combine this concept with the “images = ideas” formula, we have a series of views

imposed upon the viewer in a preordained temporal sequence, which does not happen with paintings or literary images. Hence the loss of free play, or more importantly,

free will. The cinematic experience, in this view, was not

indeterminate, but rather

determined. (Benjamin quotes Georges Duhamel: “I can no longer think what I want to think. My thoughts have been replaced by moving images.”

37) By showing us where to look, editing and cinematic narrative forced these writers to look there; this was for many patrons a step too far.

Those patrons would presumably never allow themselves to enjoy cinema’s flow of images. But the inadequacy of this rigid decree—that the flux of time jeopardizes agency and thereby imposes limits on human potential—for modern life becomes apparent in the

Kino-Debatte (and elsewhere) as well, especially in discussions that emphasized

alertness and

somnambulism. Essays often invoked these tropes when describing the tolls of modern life. Recalling Georg Simmel’s vivid portrait of “The Metropolis and Mental Life” (1905) or Freud’s idea of the “stimulus shield” (1920), these essays also assumed that life in the big city dulled the senses and made one blasé, requiring ever greater thrills to be satisfied.

38 For many writers, cinema was just the ticket: “But every day and every hour cinema restores to our pampered senses, which in the heyday of technology have forgotten how to be astonished, the feeling of Pygmalion’s enchantment with Galatea.”

39 Anticipating film theory of the 1920s, this author and others claimed that cinema renewed vision by offering a point of view we otherwise could not have. For writers such as Rauscher, cinema’s preordained succession of images was oppressive and imprisoning, whereas for this writer, it was liberating to see with another’s eyes. Max Brod, too, was rejuvenated by a visit to the cinema:

The vividness with which so much happens [in the film] has finally shaken me out of my semi-somnolent state. Now on the way home I become an inventor, imagining new images for the Biograph: a pursuit in which, instead of automobiles, locomotives or trolleys, two ships, a cruiser and a pirate ship, race against each other over the wide surface of the sea, the gap between them narrowing amid the most furious shooting.

40

Or this early editorial: “I believe that through the cinema we have only now learned to see. We have been awakened to the pleasure of watching [

Schauen]…. Reality appears much more clearly before us, and the interest is twice as great. We can almost let our mind fall asleep and reap with our eyes what the soul desires.”

41 If these writers were drifting through their modern lives, semi-awake to its challenges and blasé to its pleasures, cinema roused them from this aesthetic slumber to give them a new outlook. Here, then, a trip to the cinema did exactly what any aesthetic experience should do: renew our perception. This idea, however, was relatively new in aesthetics and already expressed the waning dominance of the Schillerian model.

Indeed, that aesthetic contemplation was undergoing a transformation is evident in essays that evoked alertness and somnambulism in terms of modern life. Strobl both admired and was uneasy with social acceleration and its effect on our perception:

But wherever the streets of world commerce run, wherever the billions cross paths, wherever goods are converted into money and money into power—at these hubs of human and commercial relations a sustained readiness is necessary. Constant presence of mind has replaced the old contemplativeness that let one’s mind wander, because we no longer need to have it at hand.

42

According to Strobl, a leisurely approach to the traffic of images or to the city was simply not viable. One required instead a “presence of mind” that was very much embedded in the present but not necessarily “swept away by the flux of time.” Alertness, as we will see in our discussion of Benjamin, was considered a more modern response to time and succession than repose, yet was no less complex in its relationship to time.

Aesthetic experience, as discussed by Kant, Schiller, and Schopenhauer in the early nineteenth century, was a complex and contradictory structure that was nonetheless required to bear a particularly heavy ethical load. If it collapses logically with the barest nudge, it was still home to a family of values related to agency and identity. As we have seen, early discussions about film were often couched in terms of agency, especially with regard to the spectator’s relation to the passing of time. Complaints about cinema’s incessant temporal push and its preordained succession of imagery continued at least one line of thinking about aesthetic experience, which insisted that the viewer’s stance before the image was also a stance before the world, one that recognized our limits but also strove to glimpse human potential in an ephemeral moment of transcendence. Aesthetic contemplation was understood as an exercise of free will, so to surrender oneself completely to the image or to the flow of time was an abdication of duty; indeterminacy meant liberty, but the rush of preordained images meant constraint. The temporal complexity of Schiller’s and Schopenhauer’s visions of aesthetic experience was therefore at odds with conceptions of cinematic temporality as constraining or controlling. But with statements attesting to the importance of alertness in modern life or positing that seeing the world from another viewpoint could reawaken the senses, the discussion began to question the utility of a leisurely aesthetic stance in favor of an approach to images—and the world—that was not merely cognitively active and unhurried, but

reactive and

quick. So in the

Kino-Debatte we can begin to see the “difficulties” new forms might have posed for what Benjamin called “traditional aesthetics.”

But an understanding of aesthetic contemplation as inherently tied to leisure and free will—or, basically, the cultured gentleman’s prerogative—is only partially correct. We must also consider the relationship between aesthetic experience and identity or subjectivity. One might think that the gentleman’s prerogative also presumed a stable, unified self, which would be confirmed in aesthetic experience.

43 Kant’s theory of the beautiful, for example, held that pleasure arose from the harmony between the artwork and our cognitive faculties, which assumed a resonance between them that was stable and stabilizing. His theory of the sublime, however, maintained that its pleasure derived from the oscillation between the physical threat of nature’s awesome power or infinitude and our cognitive framing of that boundlessness. Faced with this power, the threat of physical annihilation presented a literal loss of self, while the mastery implied by cognitively framing such power was self-affirming. So the existence of that particular kind of aesthetic experience, especially given the importance of the sublime in aesthetic theory, meant that aesthetic experience per se was never inherently stabilizing.

This split between body and mind, or between loss of self (whether through physical danger or an experience of transcendence) and self-awareness (whether cognitive or corporeal), was exacerbated by the structure of Schopenhauer’s system. On one hand, Schopenhauer insisted that a loss of self was absolutely necessary to any experience calling itself aesthetic, if it were to have any mollifying effect at all. As Schopenhauer described it, the viewer attends to the object and gradually loses self-awareness as the associations and Ideal become prominent. Likewise, his description of aesthetic contemplation emphasized the purely visual and cognitive—as opposed to corporeal—experience of viewing. For him, the aesthetic gaze divorced itself from the world, from the flux of time, and even from the artwork itself, the specifics of which did not figure largely in his understanding of aesthetic experience. Indeed, Kant, Schiller, Schelling, Schopenhauer, and Hegel all ignored the specific features of any given artwork in favor of using the object as a prompt for abstract thought and for mounting ever more complex philosophical systems. Johann Friedrich Herbart continued this approach in his formalist aesthetics, which “proposed a simplified theory of form, one that defined aesthetics essentially as the science of elementary relations to lines, tones, planes, colors, ideas, and so on,” without reference to the specter of “content” or “meaning.” Similarly, “the perfect aesthetic frame of mind for Herbart was a state of absolute indifference, that ‘quiet seriousness’ that lies ‘between depression and excitation.’”

44 In this tradition, their understanding of the gaze matched their understanding of the object: neither emphasized detail or materiality; both could be characterized as disembodied or ephemeral.

On the other hand, Schopenhauer also simultaneously pursued another approach, which he did not see as contradictory, but complementary. Part of the second volume of

The World as Will and Representation speculated on the

physiology of the perceptual act, an approach that aesthetically minded scientists such as Hermann von Helmholtz, Gustav Fechner, and Wilhelm Wundt pursued further in their experiments on the nature of (aesthetic) perception.

45 Their findings, however, indicated that the human body was a transient, variable, and unstable field upon which any subjectivity rested at its own risk. That is, if a stable and unified subjectivity previously depended on a happy conception of the body as similarly stable and unified, experimental physiology and psychology of the mid-nineteenth century invalidated that guarantee. As Jonathan Crary has argued, the fleeting nature of the human body left barely any solid ground for subjectivity.

46Many aestheticians during the late nineteenth century looked for an approach to questions about aesthetic perception that would navigate between the Scylla of abstract, disembodied philosophizing about art and the Charybdis of fragmenting, “scientistic” approaches to the aesthetic experience. They were less interested in philosophical or physiological questions about how we perceive form and space than in the psychological problem of how we take delight in the specific characteristics of form and space.

47 Robert Vischer’s seminal 1873 dissertation,

On the Optical Sense of Form, coined the term

Einfühlung, or “feeling into,” as an answer to this question.

48 Vischer meant it to explain “the symbolism of form,” or how spatial form has meaning for us: the subject “unconsciously projects its own bodily form—and with this also the soul—into the form of the object” (92). But

Einfühlung eventually came to mean emotional projection in general, and then, with Edward B. Titchener’s translation of the term as “empathy,” it transformed into a broad psychological concept.

49 In aesthetics, however,

Einfühlung was discussed in terms of several problems, including a renewed interest in analyzing the specific formal and material features of artworks and the experience they prompted

50; describing the emotional content of the aesthetic experience in terms of projection of self in relation to distinct forms; and understanding the role of the body as a measure of both art and aesthetic experience, especially in terms of aesthetic pleasure.

51 That is, writers taking up the idea of

Einfühlung explained aesthetic pleasure as a resonance between the structure of the body and the structure of the artwork, thereby explicitly acknowledging the embodied nature of perception.

52This brief history is necessary, because it clarifies “traditional aesthetics” and its “challenges,” which were twofold: (1) new artistic

forms, such as photography, fit uncomfortably in the canon of fine or even applied art; and (2) new aesthetic

experiences, especially mass reception. The question of form is outside this chapter’s purview, but we can address the nature of mass reception, which differs from individual contemplation in at least two pertinent ways: (1) the emotions of the audience amplify those of the individual, thereby making emotional projection into the work much more prominent; and (2) because of this amplification, and the awareness of being in an audience, the sense of embodiment is more pronounced as well. We could therefore view the discussion of

Einfühlung in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries as an exploration of conflicting dichotomies nascent in “traditional aesthetics” (such as the relations between mind and body, or between free will and destabilizing aesthetic experience), while also attempting to reconcile the contradictions inherent in these grand aesthetic systems with changes in class demographics as more and more people gained access to and were interested in art.

53 Specifically, I would argue that

Einfühlung aesthetics could be seen as an attempt to reconcile issues especially pertinent to mass reception (embodiment, emotional projection) with individual contemplation and its ideological implications. While mass reception was not explicitly acknowledged in discussions of

Einfühlung, the theories pave the way for a deeper understanding of the role of emotion and corporeality in aesthetic experience. Indeed, many contemporary theorists have looked back to

Einfühlung aesthetics as a possible framework for new theories of embodied spectatorship.

54The dichotomies circling around the category of identity were less fraught ideologically than those concerning agency. Whereas no one argued seriously for “determination” against “free will” (although “surrender” might have been an option), philosophers were able to describe aesthetic experience in terms of “loss of self” just as persuasively as “self-awareness.” The issue of embodied perception, however, brushed against the almost universal requirement of disinterest, in that any hint of sensuality immediately lowered the status of aesthetic experience to mere pleasure. Like paper and scissors, physicality always lost against reason in this ideological game. But because the ideological stakes were generally not as high in this category, this section will not focus on those stakes; instead it will emphasize descriptions of aesthetic experience. Specifically, in an attempt to understand precisely the nature of film’s “challenge” to “traditional aesthetics,” this section will draw upon theories of

Einfühlung, which were particularly adept at describing emotional projection and embodied perception in aesthetic experience, two issues also present in the debates about cinema. In fact, if the legitimacy of cinema as an aesthetic form in part hinged on the answers to these questions, it was also true that these two issues—which I want to stress were present in “traditional aesthetics” from the beginning, if we look closely—mounted the strongest theoretical and practical challenge to individual contemplation as it was generally understood. Emotional projection and embodied perception threatened to change the questions about aesthetic legitimacy itself. If

Einfühlung aesthetics tried to reconcile individual contemplation with features of aesthetic experience that were also prominent in mass reception, then the presence of a form such as cinema pressed harder on those questions.

This is not to say, however, that early discussions of cinema participated directly in debates within professional aesthetics or that professional aestheticians participated in the

Kino-Debatte; to my knowledge no writings on film during this period in Germany ever mentioned the term

Einfühlung.

55 But the early discussions of film brought up the same issues. To be sure, salons crowded with paintings and people had already prompted much complaint as mass reception elbowed its way into the art world and demanded a seat at the table. But cinema was not merely one of many emblems of modernity; the nature of the experience itself—the feeling of movement, synesthesia, emotional projection, and spatial depth—coincided precisely with issues in aesthetic reception that professional aesthetics hoped to pin down. We can therefore read the

Kino-Debatte as part of an extended conversation in German culture about the nature of aesthetic experience. The debates were not just a series of complaints about film encroaching on literary form and territory; they were also a very sophisticated debate about the nature of aesthetic reception, about what it meant, in a broad sense, to contemplate an image.

As an opening example, consider this quotation from a 1912 article describing an actualité that featured Wilhelm II on one of his hunting trips:

The Kaiser sits motionlessly—only the image twitches slightly here and there, flickering and spotting up as if something were boiling under the projected surface. Suddenly, he raises his rifle and my ear hears the gunshot without its being fired. The audience silently rejoices over their Kaiser’s fine shot; a wave-like movement goes through the room. The mountain goat rolls.

56

This otherwise incidental passage is exemplary of the early debates about film in its focus on audience reaction. This writer described, for example, a process of emotional projection: the audience understood the representation by projecting itself into the scene of the hunt. They rejoiced

with the kaiser as well as

over his excellent aim. The writer also emphasized the

physical response of the audience, demonstrating the importance of the body for this process of projection. The “wave-like movement” that ripples through the room was an effect of this projection. But here we should note what is different about the cinematic experience over the solitary enjoyment of a painting. This writer described the mutual amplification of audience emotion (which Benjamin later theorized in his “Work of Art” essay) that is inherent to the cinematic experience and that manifested itself here as a physical reaction. There is a reciprocity between spectator and screen, just as

Einfühlung aesthetics described the mutual relationship between viewer and artwork, but here that feeling of resonance was amplified by the number of people in the room all feeling it at once (

fig. 4.2).

Note, too, that if

Einfühlung aestheticians thought about that resonance between painting or sculpture and viewer in terms of “movement,” here that term is no longer metaphorical but strikingly literal: the movement of the image, of the kaiser, and of the audience were all working in concert to provide the basis for emotional projection. If before—as I will explain later—the idea of “movement” in aesthetics was limited to what we might term “inner movement,” or emotional resonance, now that same reciprocity depended on a

physical sensation of movement. Furthermore, just as writers on

Einfühlung argued that our senses were not strictly delimited and that stimuli for one sense could also stimulate another, so we see here a similar recognition of the confusion of the senses. In noting that he “hears the gunshot,” the writer emphasized a

synesthetic response; he recognized that the film experience is not merely visual, but that vision itself is embodied and connected to the other senses. (This “gunshot” could have been a sound effect, of course, but we should also consider that it could have been psychosomatic, an effect of deep immersion.)

This speaks to another theme in

Einfühlung aesthetics: the idea of contemplation as the ground for aesthetic experience. Our usual assumption that the spectator is held in continuous rapt attention is troubled by this passage, for it also emphasizes the

materiality of the experience: “the image twitches slightly here and there, flickering and spotting up as if something were boiling under the projected surface.” The film experience seemed to require the audience, like the motionless kaiser and the rolling mountain goat, to hold opposite attitudes—stasis and movement, contemplation and distraction—at the same time. At once immersed in the illusion while blithely noting the twitching image, the audience alternated between attention and detachment. Already, the cinematic experience highlighted contradictions at the heart of contemplation. The rest of this section, then, will explore the issues of emotional projection, synesthesia, and movement as they relate to identity and embodied perception in both

Einfühlung aesthetics and early discussions of cinema in the

Kino-Debatte.

Emotional projection was a key issue in aesthetics during this period. An essay from the debates on film will help explicate this topic. Alfred Polgar felt that attending the cinema was a sensual experience. In his 1911 essay, “Drama in the Film Theaters,” he described seeing pretty girls on the screen; they smiled at him and he felt that he should smile back, even wait for them outside the theater once the show was over. He knows it is silly to think of such things, but there is something strangely compelling in the way the film takes on a life of its own, the way it “smiles back at me.”

57 This could be the sigh of another lonely film guy, or the first glimmer of a phenomenology of film, in which the film itself has a subjectivity that engages with the spectator, such as that suggested by Vivian Sobchack.

58 But it also hints at the connection between emotional projection,

Einfühlung, and identity.

Polgar’s emotional investment in the girls on the screen recalls one of the central concepts of Vischer’s dissertation and of this trend in German aesthetics: the imputation of one’s inner life to an inanimate object, which Vischer termed Einfühlung. Vischer wrote:

We have seen how the perception of a pleasing form evokes a pleasurable sensation and how such an image symbolically relates to the idea of our own bodies—or conversely, how the imagination seeks to experience itself through the image. We thus have a wonderful ability to project and incorporate our own physical form into an objective form…. What can that form be other than the form of a content identical with it? It is therefore our own personality that we project into it. (104)

According to Vischer, we project our emotions and sense of our body (such as our orientation in space) onto an inanimate object, just as we project these aspects of ourselves onto other people to understand their expressions. To us, the work of art itself is permeated by human sensations. In fact, subjectivity is present not only in our attitude toward the work but also within the work itself. “There is also a will

within the image” (114), Vischer wrote, meaning that we project our experience on to the relation

between the parts of the work as well. Vischer’s concept of

Einfühlung described how the projection of human feelings onto inanimate objects plays a role in the creation, shaping, and reception of artworks.

Likewise, Adolf Hildebrand’s The Problem of Form in the Fine Arts (1893)—which had already gone through nine editions by 1914—was an incredibly popular exploration of the problems posed by sensual perception. He was especially interested in legibility—how we can understand the relation between changing appearances in people, nature, and art. Hilde-brand explained:

Nature in its movements and transformations produces changes in its appearance, which we interpret as the visible signs of those processes. We perceive the signs and imagine the process; we participate in it, so to speak, perform along with it, and accept the internal activity as the cause of the external appearance. Just as the child learns to understand laughter and tears by joining the process and is able to feel, through muscular activity that he himself calls forth, the inner cause of the pleasure or pain, so does all gestural expression and all movement on the part of others become for us a comprehensible expression of internal processes, a comprehensible language.

59

Hildebrand extended this analogy to inanimate objects and representations as well. We understand images by imputing them with a “story” of their processes, similar to our own; our own bodily sensations and experiences enliven the images and make them comprehensible to us. We understand art through a process of empathy. Taken together, the theories of Vischer and Hildebrand helped to establish Einfühlung as a popular explanation of the aesthetic experience.

Polgar also made a comparison between film and music to further his thesis about the power of the cinematic image. Music, he wrote, has the power to “move” us; it moves our “inner humanity” in a way quite mysterious. It could also provoke a synesthetic response: “a powerful suite of images, color, feeling, and idea.” Film, Polgar argued, functions in the same way: it is “a similar fertilization of all the other senses through the stimulation of an optical sense.”

60 This idea of synesthesia was important to

Einfühlung theorists, because it helped to describe what actually happens during aesthetic reception, but also because it indicated the centrality of the body as a measure of aesthetic response.

Einfühlung theory postulated that the harmonious correlation of form to the physical or sensory structure of the viewer was the key to aesthetic pleasure. That is, according to the theories, if the object has a structure similar to our body, it is pleasing to us; if not, it strikes us as unpleasant. By extension, the symmetry of the body accounts for the tendency toward symmetry in art. A sympathetic response to this harmony could take place on a number of levels. There is, for example, in terms of symmetry, the physical correspondence of the structure of sense organs and various objects (a horizontal line matches the horizontality of our eyes, for instance). In terms of regularity, the formal arrangement in series matches the rhythmic function of our organs. In other words, “the body, in effect, imposes an ‘organic norm’ in viewing the world, according to which regularity, symmetry, and proportion induce pleasing sensations by emulating the normal human body.”

61But this “viewing” is not merely visual. Vischer noted that sometimes “a visual stimulus is experienced not so much with our eyes as with a different sense in another part of our body” (98). Sunglasses could have the effect of “cooling” the skin, while “loud” colors might offend our auditory nerves. “For in the body there is, strictly speaking, no such process as localization.” The embodiment of vision meant that “the whole body is involved; the entire physical being is moved” (99). On one hand, this embodiment implied the possibility—even necessity—of synesthesia, at least at some level. The senses resonate with one another; the boundaries between them are not simply blurred, but porous, causing a stimulus to one sense to spark a response in the others. On the other hand, Vischer also argued that this resonance between the senses is the model for the relation between the arts: “These reflexes or reciprocal vibrations of the senses are the physical cause of the unity of the arts” (99). While this parallel between the structure of the body and the relation between the arts was just a footnote to his argument, it points to an ambiguity in Vischer’s book and in subsequent discussions of Einfühlung, as we will see: the question of embodied spectatorship did not always imply physical participation in the act of viewing; instead, it often implied shared forms and orientations between the artwork and the human body per se. That is, the body was more often a model for art than a participant in art. Vischer’s evocation of synesthesia functioned ambiguously by pointing both to embodied spectatorship and to the body as an idealized model.

However, Ernst Bloch’s 1914 essay, “Melody in the Cinema, or Immanent and Transcendental Music,” pressed harder on this issue via the example of silent film accompanied by music. A musician by training, Bloch placed greater emphasis on the redemptive and sensual nature of sound. But he argued that, while it was exclusively visual, the film image gained another dimension when combined with the proper music. Indeed, his article was a plea for music that was appropriate for the film and not simply random notes played to cover the sound of the projector. He found synesthetic possibilities in film music, which could present a complete sensual experience initiated by the ear, not the eye.

As visitors to the cinema we must initially rely exclusively upon our eyes. Now, the sense of touch conveys the impression of reality most immediately; in front of the film screen, however, we must renounce everything—pressure, warmth, scent, sound, and the feeling of being sensually encompassed [

sinnliches Mittendarinsein]—that gives the appearance of things its fully “real” character. The skin, the nose, ears, and all other senses are switched off, while the eyes are overwhelmed. Only an optical impression of black and white is excerpted from the real world, and since this impression is presented in the most confusing momentary motion and without any stylization, it produces the uncanny impression of a solar eclipse, a silent and sensuously deprived reality that is heightened only in its speed and its concentration, but without departing from our world aesthetically and ideally. But now the ear takes on an unusual function: it fills in as the replacement for all the other senses. Because the rustling, rubbing, and noisy collision of objects, because above all, human voices (which are themselves ringing with emotion) can blend seamlessly into [musical] tones—indeed, precisely because there is nowhere a natural or manufactured sound in the world that competes with music—this art form [film music] is able to reflect the colorfulness of lived reality and achieve at one stroke a sensuous totality that never makes us aware of our individual senses.

62