I step in; intermission has just begun. An oppressive, damp draft hits me, even though the doors are open. The spacious room (500 capacity) is filled to the last seat with children. There is an incredible ruckus: running, yelling, shrieking, laughing, chatting. Boys scuffle. Orange peels and empty bon-bon boxes fly through the air. The floor is studded with candy wrappers. Along the windowsills and radiators young toughs roughhouse. Girls and boys sit together, densely packed. Fourteen-year-old boys and girls with hot, excited faces tease each other in unchildlike ways…. Children of all ages, even two- and three-year-olds, sit there with glistening cheeks. Women walk among them selling sweets. Many children sneak candy and drink soda [Brause]; young boys smoke furtively.

Then the movie begins.

—A SCHOOLTEACHER FROM BREMEN (1913)

1For the cinema reformers of imperial Germany, this was a scene from hell. This is what German

Kultur had come to, what modernity had wrought: children melting and spoiled like day-old candy on the floor of a movie theater. Like Professor Rath of

Der Blaue Engel (The Blue Angel, 1930), who follows his students into a seedy nightclub and is initially shocked by the sexuality and degeneracy within, this schoolteacher from Bremen walked into a matinee and was horrified by what she saw. Her emphasis on the corporeality of the scene, on the

body of the audience, so to speak—fighting, eating, sweating, and awakening sexuality—attests to the perception that cinema presented a grave danger to the children’s emotional and moral fitness and especially their physical health. Given the traditional bourgeois association of sensuality with the lowly masses, this scene also represented a threat to the well-being of the nation, of the body politic.

2 As this chapter will demonstrate, “children” and “the masses” were often interchangeable concepts. Indeed, while cinema was often portrayed as a gaping Moloch devouring innocent children in some pagan ritual, the children depicted in this passage are far from sacrificial lambs. They present something of a veiled threat to the narrator, as if she had entered a strange, chaotic culture. In the contemporary literature on children and cinema, scenes like this one provoked twin paternal urges: to protect and to control.

“Women walk among them selling sweets.” Along with the concern for sensuality (and its tacit partner, capitalism), the numerous references to sweets stand out in this description. Implicit was the assumption that cinema was spoiling the “taste” of the children for financial gain. Reformers complained constantly about the “tastelessness” of both the theater atmosphere and the films themselves. Figuratively speaking, the concession candy that ate at the children’s teeth was also rotting their aesthetic sensibilities. Konrad Lange, a noted art historian at the University of Tübingen and a ferocious enemy of film, put it more bluntly: “If one were to judge the artistic understanding of our good, middle-class citizens, one would have to say that their taste is rotten to the core. They have a morbid taste for the slick, the effeminate, the sentimental, and the sugary. They display a demoralizing aversion to the healthy dark bread of true art.”

3 Lange made the relationship between taste, class, and the body as explicit as possible. Taste, as the simultaneous expression of individual judgment and social distinction, serves as a connection between the private and the public spheres. It is, as Pierre Bourdieu notes, “a class culture turned into nature, that is,

embodied.”

4 It therefore provides a link between individual consumption and a national agenda. Protective of the masculine ideals at the heart of that agenda, Lange condemned the feminization of culture accompanying the onslaught of modernity; he was not alone: most middle-class males of the Western world seemed to share his concerns.

5Lange’s solution, like that of many teachers and educators involved in cinema reform, stressed the education of children and adults. The abiding faith in the ability of education to overcome social ills and promote social progress was a fundamental plank in the platform of many fin de siècle movements, from the socialists to the progressives. But the tradition of

aesthetic education, with its promise to harmonize the senses and sharpen judgment, offered a quintessentially German solution.

6 By pointing the way to a “true” and “pure” aesthetic experience, aesthetic education also pledged to counteract the corrupting influence of the cinema. While many reformers, such as Lange, steadfastly refused to be seduced by cinema’s charms, some flirted with this particular Lola, courting her in hopes of making her an honest woman by giving her an aesthetic education (or an education in aesthetics). Even while the film industry used the reformers for its own ends, it revealed the contradictions of their ideology. Just as Professor Rath’s affair with Lola reveals the indefensibility of his position—a teacher who, ultimately, does not have the best interests of his students at heart—so, too, the reformers’ involvement with film shows that there were larger issues at stake than the health of the children.

Even if Professor Rath portrays the hypocrisy of his class, I see him as a distinctly modern character caught between—and profoundly ambivalent about—the solemn textbooks of his classroom and the cunning spectacle of the nightclub, or more broadly, between

Kultur and

Zivilisation. As Norbert Elias and others have noted, these terms played an important function in German self-identity; by the beginning of the twentieth century, they formed a contrasting pair. If

Kultur implied “inwardness, depth of feeling, immersion in books, development of the individual personality,” or the general cultivation of one’s inner life, then

Zivilisation implied “superficiality, ceremony, formal conversation.”

7 Or, as Raymond Geuss puts it,

Zivilisation “has a mildly pejorative connotation and was used to refer to the external trappings, artifacts, and amenities of an industrially highly advanced society and also to the overly formalistic and calculating habits and attitudes that were thought to be characteristic of such societies.”

8 By the 1910s and 1920s,

Zivilisation came to be associated with the primary burdens of industrialized society: capitalism and technology, or the utilitarian, material, even decadent world of commercial interests. By contrast,

Kultur was associated with not only inner, spiritual values but a specifically German configuration of ethical and moral ideals.

9 Professor Rath is caught between his allegiance to learning and teaching the subtleties of the German cultural heritage, to cultivating his soul and those of his students to become good Germans, on one hand, and his attraction to the superficial, voyeuristic pleasures of a crass milieu that combines the worst of sensuality and capitalism, on the other. His downward spiral, of course, begins with his choice between them.

German educators interested in reforming film and its theaters felt they faced the same dilemma. But unlike Rath, they did not approach it as an either/or choice. Instead, the appropriation of motion pictures for educational purposes was a negotiation between aesthetic and moral values, on one hand, and modern technology or commercial interests, on the other. Such negotiations necessarily implied that commercial cinema was not viewed negatively across the board. Just like the reform movements in general, film reform was nothing if not multiple, consisting of many different voices expressing the full range between progressive optimism and cultural pessimism.

10 Yet a picture emerges of a well-meaning but deeply ambivalent group committed to preserving traditional ideals while modernizing the social curriculum. Motion pictures, in this case, were for many not merely a problem to be solved but perhaps also a solution in themselves; if they could be reformed, or “ennobled” as reformers often put it, then they might serve as a means to reconcile

Zivilisation and

Kultur, a goal shared by most of the reformers of imperial Germany, no matter what their chosen object of improvement.

11 The educational use of motion picture technology reveals this attempt at reconciliation, especially in the way that films were made to fit established pedagogical practices. As reformers pressed film into an educational mold, their work also highlighted the ideological and practical contours of that framework.

Specifically, the use of motion pictures in education followed the contours of a pedagogical trend or approach known as

Anschauungsunterricht, or “visually based means of instruction.” Popularized in the nineteenth century, this method exemplified the reformist impulse in education, in that it attempted to counter the perceived overrationalization and rote memorization of the traditional pedagogical approach with a self-consciously modern strategy that emphasized the immediate visual perception of things themselves, as opposed to their description in books. Known as “the object lesson” in English-speaking countries, the approach asked teachers to present an object, such as a seashell, and ask the students a series of simple questions about it. The questions were designed to lead the students from concrete description to a higher, abstract understanding of the object in relation to its environment and to other things. Many claimed that motion pictures could function as outstanding representations of objects that could not be brought into the classroom, if and only if film could be made to conform to this and other methods of visual training. This chapter, then, continues some of the concerns traced in the previous chapter, especially the investment of the expert class in specific methods of processing visual information. At stake here is not merely the type of viewing, such as medical or scientific observation, but the culture’s interest in

what counts as learning. Anschauungsunterricht, in this respect, was not just one more pedagogical method but a way of acquiring

Kultur; it was a strong component of

Bildung, or the process of self-cultivation. What counted as learning, in this case, was a way of forging

vision and

thought into

taste; if “taste” were the sign of cultivation, then “vision” was the means by which taste was trained.

This chapter argues that the goal of reform was not merely to align film and its theaters with standards of taste and morality but to conform motion pictures to specific modes of viewing; Anschauungsunterricht serves as an obvious and convenient method of training vision to which reformers and educators adapted motion pictures and their projection. While Anschauungsunterricht was explicitly a method of training observation in school-age children, the ideal pertained to adults as well, as we see in all sorts of adult education programs at the time, especially those concerned with aesthetic education. Hence, the image of spectatorship or of ordinary movie audiences at this time must be understood in contrast to this attempt to assimilate motion pictures into a larger ideological arena, signaled most strongly by the desire to train audiences to a particular mode of viewing associated with Anschauungsunterricht and aesthetic education.

So this chapter charts the work involved in fitting motion pictures to educational and reformist agendas; it also surveys the cultural and ideological landscape on which these efforts took place.

12 Three sections alternate between practical efforts and historical and theoretical context. The first section discusses the general contours of reform in Wilhelmine Germany before outlining some of the concrete steps reformers took to protect child audiences from the hazards of cinema. Censorship, taxes, and child protection laws were accompanied by attempts to create an alternative film system by controlling means of production, distribution, and exhibition. I will also describe reformers’ efforts to persuade production companies and theater owners to support reform films and exhibition values, which led to the creation of reform theaters and community cinemas. The second section examines some of the guiding principles or assumptions behind these efforts, including

Anschauungsunterricht, aesthetic education, and the discourse on “the child” and “the masses.” The urge to protect children from the “degeneracy” of mass entertainments went hand in hand with the desire to educate the general public. Both concerns drew life from child and crowd psychology popularized at the turn of the century. Reformers saw aesthetic education and

Anschauungsunterricht, entwined in theory and practice, as potential solutions to the problematic picture of spectators the experts painted. The third section looks closely at the work of two reformers who set out to create alternative, educational, and edifying exhibition spaces in response to the perceptions and problems outlined in the previous section. Educator and reformer Hermann Lemke articulated principles for the educational use of film for school-age children, especially at commercial theaters that arranged special screenings for elementary schools. Another reformer, Hermann Häfker, hoped to offer educational or edifying film presentations for adults. Häfker’s attempts to create “model presentations” (

Mustervorstellungen) exemplify the use of film as an instrument of ideological solidarity. Increasingly worried about the “bad taste” of mass entertainments, Häfker enlisted film in a program of aesthetic education designed to raise the sensibility of the people to a unified, national level. Taking his cue from a long tradition of aesthetic education dating back to Schiller, as well as the art education movement then taking place, Häfker wanted to use motion pictures to train the tastes of the nation. Finally, this section takes a longer look at Schiller’s ideas about aesthetic education to lay bare Germany’s long-standing ideological investment in the relationships between vision, taste, pedagogy, and nation.

In their desire to make a change for the better, the men and women involved in film reform were part of a much larger set of movements sweeping the industrialized world around the turn of the century. As increased industrialization and urbanization brought one social upheaval after another, “reform” expressed the mood of the times in a variety of ways throughout Europe and the United States. In the United Kingdom, constitutional reforms swept through Parliament as groups demanded suffrage throughout the last third of the century. In the United States, the agrarian Populist movement of the 1890s and the Progressive movement of the 1900s reflected a broad impulse toward criticism and change. Progressivism, in particular, captured the spirit of reform through its outrage over the excesses of capitalism, its faith in progress, and its interventionist policies. During the 1880s, the pressures of industrialization and democracy prompted the French parliament to create the only state-run, compulsory, secular primary school system in the world. The growing confrontations between the forces of labor and capital also prodded republican politicians to campaign for social legislation, such as regulation of working conditions, to ensure social peace.

13Germany, in particular, was deluged by swelling transformations in the public sphere provoked by rapidly changing demographics. The Industrial Revolution and national unification came relatively late to Germany and accelerated very quickly. The resulting discord between the classes and between rural and urban lifestyles seemed especially acute.

14 During the high tide of these changes, which occurred from around 1890 to 1920, the concept of “reform” as an expression of the sense of transition and as a plan for managing it took on special significance for self-understanding. Germany’s groundbreaking legislation providing for compulsory insurance for workers’ sickness, workplace accidents, and retirement pensions became an influential model for the United Kingdom, the United States, and France. These measures, dealing in some form with physical conditions and consequences of the workplace, illustrate the strong connection between class and somatic issues in reform movements during the late nineteenth century. Reform manifested itself in everything from

Jugendstil decor, to a new, more “natural” style in women’s clothing (

Reformkleidung), to nutrition reform (

Ernährungsreform).

15 “Reform” implied a battle against tradition, against perceived cultural and social stagnation; as such, it provided a plan for the formation of new, more “authentic” concepts for living. In fact, the connections between the reform movements and the more general tradition of

Kulturkritik are very strong; from Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi in the eighteenth century to Friedrich Nietzsche and Paul de Lagarde in the nineteenth, the critique of society paved the way for a general re-evaluation of values in the twentieth.

16Very often, the critique of society focused on the educational system. Education reform was among the first movements to sweep across Germany. The kaiser himself had set the agenda on a December morning in 1890 while addressing a congress of educators in Berlin; Wilhelm II claimed he grasped “the spirit of an expiring century” with his calls for school reform. In answering the question of how the German schools of the nineteenth century could be reshaped to meet the needs of the twentieth, the kaiser echoed sentiments that had been expressed throughout Europe during the often rocky transition from the Victorian age to the modern. Specifically, he voiced his fears that the

Gymnasium (high school) failed to train its students adequately for the requirements of Germany’s rapid industrialization. Second, he complained about the “excess of mental work” in the schools, arguing that such “overburdening” was threatening the physical health of Germany’s youth. Finally, he insisted that German schools devote more time and energy to fostering specifically national values, thus turning away from the traditional emphasis on the classics: “We must make German the basis of the

Gymnasium; we should raise young Germans, not young Greeks and Romans.”

17The kaiser’s concerns about “the modern,” “the healthy,” and “the national” reflected and reinforced similar fixations of the European elite. Like them, he found the educational system to be both the problem and the solution to perceived crises. By inadequately preparing the nation’s children for the demands of the future, the system risked irrelevance, according to reformers of the time. Swift reform promised both a brighter future and a greater measure of control over the rapid changes taking place. Among the different examples of education reform were the country boarding schools (

Landerziehungsheime), which were experimental schools located in the countryside as an explicit rejection of urban culture.

18 Their emphasis on physical education echoed the hopes of the youth movement for a spiritually renewing combination of countryside, fresh air, and

Volk. Likewise, work schools (

Arbeitsschule) hoped to renew the creative (and ethical, hence political) spirit through manual labor, such as gardening, and handicrafts, such as wood sculpting or leatherwork.

19 The art education movement (

Kunsterziehungsbewegung) similarly stressed the creative capacities of children, advocating renewal through art and education of the aesthetic sensibility.

Film reformers shared the kaiser’s interest in “the modern,” “the healthy,” and “the national.”

20 At the center of their concerns lay motion pictures, which they also found to be both scourge and cure. An emblem of modernity, cinema represented a plague, especially toxic to children, and proper education of the public was the only hope to halt the epidemic. At the same time, cinema was emerging as the most powerful instrument of mass education and therefore potentially provided the surest treatment for whatever ills modernity had spread. Before treatment could begin, however, commercial interests had to be persuaded to participate in this remedy. Moreover, film needed a stamp of legitimacy to have any authority in this rescue mission. Film reform was the process by which these goals were attempted, if not completely achieved. It shared roots, objectives, and ideology with other reform movements of the day, especially, and not surprisingly, educational reform.

It does seem rather unusual that the head of the German empire, almost by definition the representative of a conservative status quo, would come out so strongly in favor of reform. A mixture of progressive reforms and reactionary politics indicated the ambivalent attitude of the bourgeoisie toward the troubling issues of the day.

21 All reform movements revealed, in one way or another, the fundamental irony of the kaiser’s position. The calls for clothing reform in Germany exemplified this contradiction. In his 1901 book,

The Culture of the Female Body as a Foundation for Women’

s Clothing, Paul Schultze-Naumberg made an extensive study of the debilitating physical effects resulting from methods of forcing the female form into an aesthetic ideal. In a graphic and impassioned plea to eliminate the corset, in particular, Schultze-Naumberg demonstrated how its use eventually caused deformation of the muscles, bones, and internal organs. He called for a more functional clothing in keeping with “a new concept of corporeality.”

22 While consistent with similar efforts by women’s movements to liberate themselves from the pressures of social constraints, Schultze-Naumberg’s “new concept” of more “natural” bodies included only those from healthy German stock. Carl Heinrich Stratz, another strong advocate of clothing reform, took a similar approach in his book

Women’

s Clothing and Its Natural Development, grounding his arguments for the elimination of the corset on the conclusion that it threatened the racial superiority of European women.

23 Schultze-Naumberg and Stratz, whose worries about the integrity of the Fatherland were cloaked in concerns for the health of women, are excellent examples of the fusion of progressive goals of more liberal movements with reactionary, nationalist politics.

Clearly, Schultze-Naumberg and Stratz shared with their fellow guardians of culture a rather paternalistic attitude toward the role of women in the changing public sphere of modernizing Germany. Women in general, and female sexuality in particular, were often targets of public disapproval about modern life, as in Stratz’s work above, or in the complaints about Asta Nielsen’s “unladylike” behavior in her films, or in the concerns about the number of women in cinema audiences. For some, these complaints are signs of a deeper anxiety about the increasing role of women in public life in Germany; the women’s movement or the youth movement in their various manifestations are often cited as prime motivators in the perceived decline of male cultural authority.

24 According to this version, the women’s movement exemplified a menace that appeared to surround German intellectuals; actions such as the youth movements seemed to threaten paternal credibility even in the home.

25 Faced with such massive structural changes, the cultural elite embraced reform as a way of coping with, and controlling, modernization. While it is true that most voices that survive in print are male, we must not forget that women were not simply the objects but the agents of reform. In fact, late nineteenth-century imperial Germany saw a proliferation of volunteer organizations—instigating reform, helping the poor, and exchanging information—that provided structure to a society in transition. Women entered the public sphere not only as consumers but also through volunteer organizations that functioned in tandem with, even as a substitute for, the state and provided steady and urgent pressure for changes in social policy. So social policy in imperial Germany was not simply a top-down affair instigated by male experts but grew out of women’s culture.

26 Likewise, while Germany’s “crisis in culture” might have been acutely felt by male intellectuals as a decline of male authority,

27 this perception must be tempered by the knowledge that the social mobility that women and workers gained from modernization also benefited males and the middle class not only through the greater economic power that came with a consumer society but the political power that came with the alignment of state policy with middle-class goals—an alignment that occurred partly as a result of the intervention of women’s and volunteer organizations.

28 So while the hyperbole of public debate sometimes provides an easy example of male, middle-class “anxiety,” we should not take it entirely at face value.

The

Schund campaigns of late nineteenth-century Germany are a great example of the battle between modern consumer culture and the goals of middle-class volunteer organizations.

Schund is usually translated as “trash” or “rubbish,” but reformers of the late nineteenth century applied it to serialized novels and pamphlets purveyed by colporteurs or kiosks, especially literature perceived to lack any redeeming value yet not obscene. While the serialized novel emerged in the mid-nineteenth century, the market grew exponentially thereafter; by 1890 it was so popular that

Schundliteratur accounted for fully two-thirds of all German literary sales.

29 By the time of the Weimar Republic,

Schund referred in general to any thin, mass-market paperback novel sold by the millions at kiosks and stationery shops.

30Educators and school administrators were the first to launch campaigns against this form of entertainment; according to Corey Ross, “the roots of the campaign against

Schund can indeed be traced back to the efforts of elementary school teachers in the 1870s and 1880s to influence the reading habits of their pupils by drawing up lists of recommended titles.”

31 Teachers continued to be the primary force behind these campaigns, even as they comprised a diverse group of interested parties, including temperance groups, religious associations, women’s commissions, leagues against public vice, and local police forces.

32 Yet, as Kara Ritzheimer has argued, the rhetoric of reform unified these groups, despite their diverse goals and methods. Ritzheimer paraphrases, for example, a professor who warned that

children who read excessively were likely to develop a lust for reading (

Lesewut) that might “effeminize the body,” “cause the senses to lose their acuteness,” “weaken the memory,” “over-excite the imagination,” and “destroy a will to pay attention to serious matters.” Furthermore, this “reading lust” was capable of breeding indolence (

Schlaffheit), indifference (

Gleichgültigkeit), absentmindedness (

Zerfahrenheit), mental laziness (

Denkfaulheit), extravagance (

Überspanntheit), and slack behavior when it came to work and play (

Unlust zu Arbeit und Spiel sich einstellen).

33

This rhetoric of sensuality, addiction, feminization, and weakness was a portrait of media effects that transformed apparently normal children into the worst caricature of the lower class. Beyond the vocabulary of media effects, these groups also promoted

children as the primary focus of their efforts, thereby unifying their protectionist rhetoric around a class-neutral issue, rather than waging a campaign in the name of

adults, which could barely evade paternalistic connotations, if not all-out class warfare.

34 In any case, the rhetoric was incredibly pliable, in that it was applied equally vociferously to books and motion pictures.

Cinema reform not only patterned itself after the educational reform movements, the instigators were often hardened veterans of the anti-

Schund campaigns. Karl Brunner, for example, was a

Gymnasium professor and a leading anti-

Schund campaigner who eventually became the head film censor in Berlin.

35 The Hamburg commission discussed later started as a response to

Schund. Most of the reformers were teachers and educators, so their close ties to the education reform groups of the period were also formative. Hermann Lemke, a

Gymnasium professor from Storkow and one of the founders of

Kinoreform, was well connected to the Society for the Dissemination of Popular Education (Gesellschaft zur Verbreitung von Volksbildung), the leading educational organization in Germany. Hermann Häfker, the most articulate representative of film reform and arguably Germany’s first film theorist, was a journalist and writer who was also close to the leaders of the art education movement. Konrad Lange, one of the leading voices of the art education movement, taught art history at the University of Tübingen.

Despite their similar backgrounds, these reformers were not all of one mind. The disparate views and priorities of all involved, as well as the absence of a central organization or platform, make it difficult even to characterize

Kinoreform as a movement. Scattered around mostly northern and small-town Germany, the representatives worked primarily at the local level, trying to coordinate national efforts through friendly trade journals, such as

Der Kinematograph (1907–1935) out of Düsseldorf and especially

Bild und Film (1912–1914) out of Mönchen-Gladbach. The birth of trade magazines devoted exclusively to film coincides with the birth of the reform movement in 1907; during its earliest years,

Der Kinematograph acted as a willing partner in

Kinoreform.

36 The range of viewpoints in its pages, and in the other magazines that followed shortly thereafter, testifies to the difficulty the reformers had in choosing the most effective course of action.

If they did not agree on methods, their approaches at least reflected the experience and infrastructure already gained in the work against

Schund. Basically, the efforts of the film reform movement overall can be divided into “negative” and “positive” solutions, in the parlance of the day: those that emphasized regulation, taxes, police enforcement, and censorship, and those that offered alternatives to the objectionable fare; this chapter will focus on the latter, “positive” approach. We can also divide these approaches further based on the object of reform.

Filmreform, for example, expressed an emphasis on the

content of films, with an accompanying strategy that focused on production.

Kinoreform, on the other hand, expressed an emphasis on the

space of film exhibition, and with it a strategy to clean up and “uplift” film theaters (

fig. 3.1).

Filmreformers such as Brunner and Lange spent their energy devising negative methods to control film production and reception, while Lemke and Häfker developed positive strategies for both

Filmreform and

Kinoreform.

Courtesy Deutsches Institut für Filmkunde, Wiesbaden

Yet these reformers had a set of common objectives framed in ways similar to those in the

Schund campaigns. First and foremost, they felt compelled to protect children from what they perceived to be the dangerous effects of cinema. This was first explicitly stated in 1907, when a teacher’s group in Hamburg, the Society of Friends of the Schools and Instruction for the Fatherland (Gesellschaft der Freunde des vaterländischen Schul- und Erziehungswesens), formed a commission to study the effects of cinema on schoolchildren. Its conclusions were predictable and familiar: both the films themselves and the theaters produced physical and moral side effects in school-age children. The combination of the “flicker effect” and the lack of adequate ventilation in theaters caused “eyestrain, nausea, and vomiting,” according to the commission. Emphasizing the connection between the body and ethical judgment, the symptoms were a sign of a deeper moral sickness, manifested in school by “apathy for learning, carelessness, and a tendency to daydream.”

37 Jurist Albert Hellwig, certainly the most prolific reformer who advocated the negative approach, echoed these concerns in 1914, when he argued that “a promotion of a certain superficiality and inattentiveness, as well as a retardation of concentration and aesthetic cultivation” could be counted among the psychological dangers to young moviegoers—a diagnosis familiar from the discourse examined in the previous chapter.

38Second, the reformers made it clear from the very beginning that they hoped to use cinema for educational purposes. In this and many other ways, the German reformers were very similar to their American counterparts, who also took it upon themselves to “uplift” both the theaters and the films for the good of the masses.

39 The Hamburg commission concluded its study with the recommendation that

Technically and thematically impeccable cinematic presentations can be an outstanding instrument for education and entertainment. Pedagogically and artistically minded groups must advocate for better, nobler uses of the cinematograph by encouraging the big corporations in this industry to present good, child-oriented productions in special screenings for children.

40

Hermann Lemke answered this call to arms independently in the summer of 1907, when he persuaded a Friedenau cinema theater owner to host Germany’s first “reform theater,” which was likely merely a “film reform” night or series at a commercial theater, given that it did not last very long in this form. Lemke gave the opening address, making the goals of cinema reform clear to the mostly middle-class audience of teachers, press, and community leaders. He charged that the current state of cinema had caused the aesthetic sensibilities of the people to regress. Calling on the combined power of educators and the press, he maintained that “when the taste of the people is so backward, it’s the duty of the intellectual [

geistigen] leaders to influence them and put their aesthetic taste back on the right track.” Cleaning up the cinema theaters was the first order of business in this project, making it one of the earliest examples of

Kinoreform. Lemke applauded the improvements the theater owner had already made:

This reformation is already apparent in the way this auditorium has been given a worthy interior decoration. Gone is the small, narrow room where everyone is crammed and squeezed together; in its place we find a larger, airier hall … so that the patron’s sense that he is in a second-rate establishment vanishes all on its own. Good ventilation has been provided in order to reduce health risks.

41

Lemke’s concerns demonstrate how closely “taste” and “respectability” were tied to “the body,” and especially the body of “the masses.” He was preaching to the converted, however.

Der Kinematograph later reported, “it seems that the middle class is more interested than the working class in the direction the reform theater is taking. While the seats in the third section show hardly any patrons, the first section (50 cents admission) is mostly sold out.”

42 Still, Lemke was sufficiently encouraged to organize a Cinema Reform Association the following autumn.

43 Represented by teachers, members of the press, theater owners, and production companies, the association was one of many throughout Germany that hoped to coordinate efforts from these quarters toward their educational goals. Indeed, composed of businessmen, teachers, council members, and theater owners in the community, local

Kino-Kommissions such as this were the primary means through which reformers organized their efforts, disseminated their results, and created larger networks.

44 Lemke’s society received contributions from such firms as the German branches of Eclipse and Gaumont.

45 While cleaning up the

Kinos, the reformers turned their attention to the films themselves.

Enjoying an easy fraternity with producers during the early years, film reformers hoped to capitalize upon their good relations with the motion picture companies to increase the number and availability of reform-type productions. In a particularly idealistic move indicative of the “positive” approach, Lemke in 1908 suggested that his reform association act as a “Film-Idea-Central,” a clearinghouse of sorts for reform-minded scripts. Members of the association could submit ideas for scenarios, and the society would negotiate with the studios on the writers’ behalf. Lemke explained, “Because we’re in constant contact with the manufacturers, such an exchange will be relatively easy to arrange, particularly because we know what is being demanded. We would provide distribution free of charge and only require that those who use it become members. In this way, we may be able to bring the film companies to the cutting edge of this moment and also have a productive influence internationally.”

46 Unfortunately, while the members of the movement might have held some early enthusiasm for this plan, the film companies themselves apparently did not take to it; the idea never went beyond the initial stages, and no further mention is made of the Film-Idea-Central in the trade press or reform publications.

The failure of the Film-Idea-Central and the film reform theater in Friedenau established something of a frustrating pattern for the reformers. Film companies and exhibitors expressed early interest in reform projects, even going so far as to sponsor events, but eventually refused more meaningful and lasting support. The end of 1908 saw the opening of Germany’s first film trade show/exhibition at Berlin’s Zoological Gardens. Jointly sponsored by Lemke’s reform party and the leading film companies at the time, and with the rather obvious motto of Refining the Cinema (

Veredelung des Kinos), it was nonetheless heavily criticized even by friendly periodicals for its lack of organization.

47 Exhibitors, manufacturers, and production companies declined the reformers’ help for the next exhibit in 1912.

48 Likewise, when Lemke and Häfker attempted to muster support for their special exhibitions, the film companies were initially supportive but lost interest fairly quickly. Realizing that domestic companies could not or would not produce sufficient numbers and variety of educational films, Häfker went so far as visiting foreign film companies, such as the Charles Urban Trading Company in London and Eclipse in Paris, to find suitable nature films for his exhibitions.

49 Lemke even went to England and wrote film treatments to jump-start some sort of interest in his program.

50 Very early on, it was quite clear that the production companies were cautious about backing the reformers and their schemes.

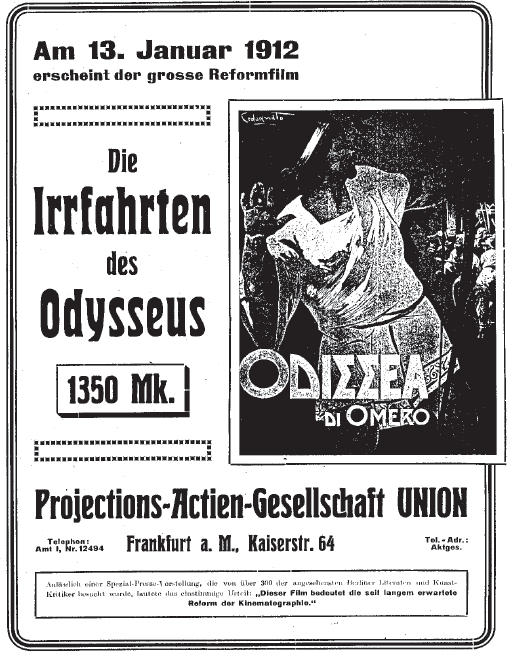

This did not mean, however, that the film companies wanted nothing to do with the reform movement. They were certainly willing to use the reform movement for their own ends; despite their difficulties, the reformers were still a legitimating presence—they were, after all, educators, clergy, journalists, and otherwise pillars of their respective communities. Film companies were eager to cash in on this allegiance. Advertising trumpeted this relationship, even if the reformers had nothing to do with the making of the film. A 1912 Italian film distributed by the German company PAGU,

Die Irrfahrten des Odysseus (The Wanderings of Odysseus), was rather disingenuously labeled a “Reformfilm” and carried this blurb: “From a special press screening, which was attended by the most respected Berlin literary figures and art critics, came the unanimous decision: ‘This film signals the long-awaited reform of cinema’” (

fig. 3.2).

51 Aware of the potential directions cinema could take, the film companies initially went along with the reformers, especially if they could be used as a selling point. But as soon as it became apparent that the vast majority of the viewing public was more interested in narrative entertainment free from “ennobling” connotations, the companies brushed off the reform societies’ efforts to influence the product directly.

The extreme positions of some reformers did little to help the overall cause with the production companies. Lange and Brunner, for example, were steadfast in refusing film any legitimacy whatsoever as a medium of entertainment. Their regular denunciations of “film drama” (

Kinodrama) merely antagonized an industry leaning heavily toward narrative films. This prejudice against narrative films often disguised stronger rhetoric against international domination of the German film market. “In the international film drama, the wildest passions of all nations come together for a gruesome rendezvous,” clergyman Paul Samuleit charged.

52 Likewise, their complaints about capitalist interests tainting cinema’s potential were thinly veiled laments about the presence of

foreign capital. Some reformers, such as Häfker and Lange, dismissed film drama because of aesthetic concerns. It did not offend their sensibilities because of sloppy production qualities, although these did attract attention. Rather, the filmed drama betrayed what they saw to be cinema’s primary mission: to record movement and “real life.” The argument for filmic realism, of course, coincided with their desire to use cinema for educational purposes, as we will see in the next section. As Sabine Hake notes, they did not dismiss the possibility of story elements in their educational films, but the excesses of the “trashy film” so contradicted their stated ideals that many rallied against film drama altogether, for both political and aesthetic reasons.

53

Lemke hoped to reform the cinema through example, stressing cooperation with and from the industry, and to rally schools together to create a distribution system.

54 Others were not so willing to rely on this teamwork. One faction of the reform movement, led by Albert Hellwig and Karl Brunner, saw censorship and regulation (the “negative” approach) as the best way to combat the onslaught of

Schundfilme. Both Hellwig and Brunner advocated a series of legal restrictions on the cinema, including censorship, entertainment taxes (

Lustbarkeitsteuer), poster censorship, safety regulations, and child protection laws (

Kinderschutz).

55 Authorities tried to maintain some control over child audiences (and, consequently, theaters) by restricting their visits to specific hours of the day, regulating the length of the matinees, and requiring that they be accompanied by an adult, that police should have unlimited access to the theater during the matinees, that the day’s program must be given prior approval, or that a “suitable pause” separate the films.

56Reformers recognized early on the importance of establishing a distribution network for their educational films. For this task, Lemke and his circle enlisted the help of the Society for the Dissemination of Adult Education (Gesellschaft zur Verbreitung von Volksbildung, hereafter referred to as the GVV). An umbrella organization for more than 8,000 local education groups, clubs, associations, and societies, it was a formidable partner in

Kinoreform. Bildungs-Verein, the house publication, had a circulation of 13,000—many times that of any film trade magazine. Yet the GVV leadership was hesitant about cinema’s importance as an educational tool. Even though Johannes Tews, the director of the GVV and editor of

Bildungs-Verein, had attended the opening of Lemke’s Friedenau reform theater, he still considered cinema to be of minor significance.

57 The GVV resisted involvement with cinema until 1912, when it established a film distribution center of 180 films in 16 categories, from history of the Fatherland to educational films on biology.

58The reformers found a more willing and beneficial partner in the Lichtbilderei, established in 1909 as a foundation of the Association for Catholic Germany (Volksverein für das katholische Deutschland). The Lichtbilderei was Germany’s largest educational film institute before World War I, with an extensive catalog of titles. It began as a rental source for magic lantern slides, which could be used for public lectures, but started collecting films as well after 1911. By the end of 1912, it reportedly had around 900 titles and was collecting more at about 30 films per week, and by 1913 offered 400 slide series and 1,400 film titles.

59 The Lichtbilderei was not limited to providing films for schools, churches, and clubs; it also provided programming for many commercial theaters. Approximately 40 weekly theaters and 50 to 60 Sunday

Kinos showed Lichtbilderei films regularly.

60 The Lichtbilderei was also involved in the distribution of more commercial dramas, actually acquiring “monopoly” rights over such established hits as

Quo Vadis? (Italy, 1913),

Giovanna d’

Arco (The Maid from Orleans, 1913), and

Tirol in Waffen (Tirol in Arms, 1914).

61 From 1912 to 1915, the Lichtbilderei was something of an organizational center for the cinema reform movement.

62 Its stock of films gave life to the community cinemas and private

Reformkinos, and its publications—the periodical

Bild und Film (Image and Film) and the series of books from the association’s Volksvereins publishing company—were the principal forum for the discussion of

Kinoreform issues after 1912.

In 1912, the GVV, in association with the Lichtbilderei, established the funds for two educationally oriented

Wanderkino. These traveling cinemas toured from town to town, playing for four to six weeks in each place, in an effort to offset the influence of commercial cinemas and unify aesthetic and educational standards across the nation. Showing between nine and eleven films an evening, accompanied by lectures concerning such topics as “A Modern Factory,” the enterprise was basically modeled after the GVV’s successful

Wandertheater and public lecture series. Between the fall of 1912 and the outbreak of war, the

Wanderkinos offered a total of 1,279 such evenings.

63Reformers had most success with their exhibition experiments. In addition to the reform theaters and

Wanderkinos already mentioned, a number of communities established their own public cinemas. The first was founded in the town of Eickel at a cost to the community of 14,000 German marks. Others opened soon afterward, in such towns as Altona, Wiesbaden, Osterfeld, Frankfurt (Oder), Gleiwitz, and Stettin.

64 These cinemas became the center of local reform activity and provided the precedent for the state-run cinemas of modern Germany, which continue to illustrate the relation between taste and nation. The proclamations of the early

kommunale Kinos articulated this relationship and the goals of the reform movement in general:

To oppose, for aesthetic, cultural, and patriotic reasons, the trash that is generally offered in the private theaters; to replace it with films of scientific, entertaining, and educational value; to exert, in association with established institutions with similar principles, a gradual influence on the film market, which is currently almost entirely dependent on foreign countries, and thereby keep here the millions that are flowing out of the country. Finally, to enlist cinema in the service of youth organizations and colleges by providing suitable presentations.

65

To the modern observer, the cinema reformers of imperial Germany might seem a bit quixotic. Tilting their lances to such impassive windmills as capitalism and narrative, they only reluctantly and belatedly conceded that they were charging against the wind of public opinion. As the movies became more popular and an evening’s entertainment began to look less and less like a lecture series, instead relying more heavily on

Kinodrama, the reformers began to look more and more irrelevant. Their own Dulcinea—the children of the nation—seemed oblivious to their activities. Even those sympathetic to their cause, like this reviewer of a book on cinema and theater reform, found their efforts somewhat naive.

[The author] is certainly entitled to his opinion in this terribly serious matter. However, he will surely also understand the skepticism of those who do not believe at all in the “ennobling” of films towards a literary bent [

literarischen Seite], because they see completely heterogeneous things being forced into an unhappy marriage. The idea that benevolent corporations will free the theaters of commercial interests altogether is too pretty to be given much credence.

66

Others were not so kind. Speaking on behalf of the industry in 1911, a trade journal editor pointedly replied to the reformers, “We ourselves know what we need, and we don’t need tutelage.”

67 One theater owner from the 1920s remembered them as “sanctimonious folks and hypocrites, morality sleuths in male and female guise.”

68 Film histories, until recently, have been equally dismissive. Siegfried Kracauer charged simply that, with their zealous efforts to defend the literary canon of the nation, “they yielded to the truly German desire to serve the established powers.”

69 Even if a bit condescending, Kracauer was not far off the mark. While the proclamations of the various

Kinoreformers embraced a wide range of opinion, they never strayed far from the status quo. As Sabine Hake noted, “In sharp contrast to the intellectuals, the reformers aligned themselves openly with the existing power structure.”

70 We must not, however, underestimate the reformers’ contribution to German culture. In trying to sway what Kracauer called “the salutary indifference of the masses,” the reformers succeeded in dominating the discourse on cinema in the years before World War I. In addition to the permanent impression they left on German film culture, German mass communication research owes them an especially heavy debt: their focus on media effects had a lasting influence on the vocabulary and goals of modern mass media studies in Germany.

71Ultimately, of course, cinema reform was not completely successful. The reformers failed to meet their stated goals and, considering the extreme position of many reformers, this is perhaps all for the best. World War I abruptly changed the nation’s priorities, and even though the calls for reform were heard again through the Weimar years, the urgency of the moment had passed. In 1913, lances heavy with disappointment, the movement clearly appeared to be running out of breath. Sighed Lemke, “I was always hoping that someone would take over the chairmanship from me, assist me, and further expand the [Cinema Reform] Association, but no one was willing to do so and the result was that the Association remained in its infancy [

in seinen Kinderschuhen stecken blieb, or literally, “stuck in its children’s shoes”].”

72Lemke’s metaphor was apt, because it reveals the extent to which the reformers thought about the cinema (and themselves) through the metaphor of “the child.” Because they were educators and teachers, this is perhaps to be expected. It is noteworthy, however, that they applied this trope to adult audiences. References to their audiences as “children,” especially in connection with mention of “the masses,” are scattered throughout the discourse.

73 One reformer, looking for the underlying causes of cinematic drama’s continued popularity, maintained that “just as much blame belongs to the audience, the people [

das Volk], this ‘big child,’ whose alarmingly spoiled taste craves for cinema’s dramatic trash and silly comedies, practically forcing the theater owners to present them with aesthetic and moral duds week after week.”

74 Even Georg Lukács thought about cinema spectatorship in terms of children: “In the ‘cinema’ we should forget these heights [of great drama] and become irresponsible. The

child in every individual is set free and becomes lord of the psyche of the spectator.”

75 Whether Lukács’s “inner child” was inherently good or evil depends upon one’s viewpoint, of course, and there were many to choose from at this time.

This section will survey some of the prevailing assumptions about child psychology and pedagogy to clarify the underlying ideological presumptions about child and adult moviegoers. “Suggestibility” was the common denominator linking children and crowds; studies of children were even the source of theories about social psychology. So this section will demonstrate how the portrait of (film) spectatorship usually derived from expert analyses of children and crowds. At the same time, I will show that symptoms of this spectatorship were problems to be solved by training in observational methods, specifically aesthetic education exemplified by the kind of programs promoted by Hamburg museum director Alfred Lichtwark, who was the driving force behind the art education movement of the time. His approach was popular and well known to film reformers—especially because its nationalist flavor appealed to the taste of many experts of the day—but it was also familiar because it exemplified the observational approach to general education known as

Anschauungsunterricht. Looking closely at this approach or trend in pedagogy reveals it was a self-conscious response to the perceived disorder and quickened pace of modern life; observational training was a way of ordering thought that countered pace and disorder by emphasizing “dwelling” and correlation. This section thereby connects psychology, reform movements, and pedagogy to explain the ideological and practical emphasis on expert modes of viewing as a solution to the multiple problems spectatorship posed to film reform.

Child psychology of the period provides a partial explanation for the equation of children and the masses. Swedish author Ellen Key’s

Century of the Child, an enormously popular children’s rights manifesto published originally in 1900, advocated a reassessment of the prevailing view that children were inherently evil. Summing up a trend in child psychology that emphasized the creative nature of the child, it called for new teaching methods to correspond to the new century, leaving behind the authoritarian methods of the old school and reassessing pedagogy “from the child outward” (

vom Kinde aus). If adult society, utilitarianism, and the demands of the “real world” had determined the standards of pedagogy before, now attention turned to the child’s needs and inner nature. Whereas the old pedagogy might have emphasized uniformity, now the child could expect to be treated as “the measure of itself.”

76 As Key insisted, “instruction should only cultivate the child’s own individual nature,” which Key and others assumed to be creative, good, and even wise.

77Freud, however, was less optimistic about the life of the child. His essay on “Infantile Sexuality,” published in his 1905

Three Essays on Sexuality, painted a darker picture of childhood as a “hothouse of nascent psychopathology.”

78 His explanation of the importance of the child’s body—describing the oral, anal, and phallic stages—on mental development was groundbreaking. Its lasting contribution is manifold, but most immediately it underlined the influence of childhood development on adult mental life. While there is little indication that Freud’s theories were wholeheartedly accepted by garden-variety reformers, the new child psychology of both Key and Freud provides a clue to the urgency reformers felt when they argued for aesthetic cultivation and against the influence of sexually charged

Kinodramen.

Despite Sigmund Freud’s seminal contributions, Darwin’s evolutionary theories of child development still had a strong grip on the public imagination during this period. In particular, Darwin argued that child development recapitulated the mental evolution of the species. Accordingly, the maturing child was expected to exhibit mental characteristics of subhuman species. In

The Descent of Man, Darwin observed, “We daily see these faculties developing in every infant; and we may trace a perfect gradation from the mind of an utter idiot, lower than that of an animal low in the scale, to the mind of a Newton.”

79 Discussions of crowd psychology latched onto this teleological comparison between children and primitive mentalities.

80 Gustave Le Bon, the most well known popularizer of nineteenth-century crowd psychology, characterized the masses as “an enraged child.” Furthermore, according to Le Bon,

It will be remarked that among the special characteristics of crowds there are several—such as impulsiveness, irritability, incapacity to reason, the absence of judgment and of the critical spirit, the exaggeration of the sentiments, and others besides—which are almost always observed in beings belonging to inferior forms of evolution—in women, savages, and children, for instance.

81

Darwin’s evolutionary scheme provided a quasi-scientific basis for comparing crowds with children, but even more significant for this comparison was the concept of “suggestibility.” Le Bon devoted a chapter to “the suggestibility and credulity of crowds,” arguing that the crowd is “perpetually hovering on the borderland of unconsciousness, readily yielding to all suggestions” (21), a mental state most commonly found in women and children (29). Most serious psychologists of his time dismissed Le Bon’s rather crude arguments, but the metaphorical connection between children and the masses was still quite powerful for researchers. In fact, one could argue that social psychology has its roots in child study. Alfred Binet, a disciple of La Salpêtrière’s Charcot and one of the founders of experimental social psychology, used the observational opportunities provided by public school classrooms to test his evolving theories of suggestibility. His conclusions about children and suggestibility worked their way into his formative studies of social behavior, which had a profound impact on the direction of modern social psychology.

82Reformers borrowed the concept of “suggestibility” as they described the cinema audiences and their scopophilia or

Schaulust.

83 The Hamburg commission noted this condition in their report, complaining that

many cinema presentations endanger children morally as well. Let’s assume, for example, that a young boy with a tendency towards thievery were to see crimes presented with elegance and brilliant success. Wouldn’t that arouse his imitative instinct? A young girl could easily learn how to get easy money and enjoy an apparently carefree and, in her eyes, wonderful life by selling her honor. When she needs to earn a living later in life, she might ask herself: “why work at a sewing machine for 10 pfennigs an hour, why work at a factory for 10 marks a week?”

84

Why, indeed? These remarks prefigure persistent themes in the discourse on cinema during this period, especially the preoccupations with suggestibility, crime, and female sexuality. Emilie Altenloh, author of the first sociological study of cinema, even found parts of this equation in the nature of female spectatorship:

The female sex, of which it is generally said that it always purely and emotionally absorbs an impression in its entirety, must be particularly receptive to filmic presentation. By contrast, it seems very difficult for people who are highly developed intellectually to project themselves into the sequences of events, which are often strung together haphazardly. On various occasions people who were used to grasping things on a purely intellectual level said that it was extremely hard for them to comprehend the logic of a movie plot.

85

Altenloh equated holistic or synthetic approaches to the image with female spectatorship, and analytic approaches with expert or educated observation. She suggested that, on one hand, this open or holistic approach to the image enabled an empathetic projection that is unavailable to those who approach the film analytically. On the other hand, this empathetic mode of viewing left the spectator vulnerable to suggestion, and in this step she equated feminine and childlike modes of spectatorship. She further maintained that, in the absence of a strong family life or education, cinema held a mesmerizing influence on its young patrons, especially young male workers: “It is undeniable that the cinema’s lack of all higher interests has a certain influence on the entire way of thinking and living for these unstable people [

ungefestigen Menschen],” she concluded. “From the lives of outlaws, the morals of Apaches, and the fearlessness of heroes in cowboy films they take a philosophy of life that forces them into trajectories similar to that of their celebrated idols.”

86Albert Hellwig also wrote often on the suggestive power of cinema and its dangers for the criminally inclined or morally weak. In one article, he described a neurasthenic woman’s response to a night at the movies. In the film, a postal clerk dreams that he is attacked by robbers: “there appear a series of threatening faces and ghostlike hands, which reach out to others in their sleep.” This made such an impression on the young lady that she began to see hallucinations of these hands day and night. “The rather intelligent lady was initially fully aware that it was merely a hallucination, a product of her imagination. She was nonetheless quite upset because she saw this group of gigantic hands appear suddenly and in a variety of circumstances.”

87 Hellwig implied that the cause of the woman’s hallucinations was a combination of cinema’s suggestive power and the woman’s pathological condition, neurasthenia, a vague, yet debilitating nervous condition in vogue during this time. It left its victims incapable of work and inflicted upon them a dazzling array of symptoms, including headaches, the fear of responsibility, graying hair, and insomnia. According to Anson Rabinbach, “neurasthenics were identifiable by their impoverished energy and by the excessive intrusion of modern urban society on their physical and mental organization.”

88 It was a form of mental fatigue that left its victims unable to resist the stimuli of the modern world; it was characterized, in short, as a weakness of the will, as moral exhaustion.

The combination of pathology and morality is significant, because the concept of “moral weakness” metaphorically connected judgment and physical strength. The reformers’ focus on both the unhealthy atmosphere of the nickelodeons and suggestive power of film reveals an underlying concern for both the bodies of the audiences and their moral judgment. This concern manifested itself as a problem of “taste”—taste lies between the realms of sensuality and reason. As with the question of the nature of the child, reformers were divided over the nature of the masses, especially their judgment. Against those who argued that the masses were not ready for reform, that they were not interested in what interested the educated classes, Hermann Lemke argued, “I for one cannot imagine that the general population has such bad taste; and even if the people were not yet mature enough for it [cinema’s reform], they would have to be educated. But one must never indulge their lowest instincts—that is harmful to the community and must be prevented.”

89 Hellwig was less willing to entertain the idea that the masses were inherently good: “It is the bad taste of the audience that ultimately makes the trashy film.”

90 The solution to this problem of taste and, by extension, the crisis of moral judgment, was aesthetic education.

Since Schiller, aesthetic education has offered a solution to the twin problems of sensuality and suggestibility. That is, Schiller suggested the category of the aesthetic as a medium between alienated Nature and Reason. In an alienated world, the aesthetic provided Schiller with hope for reintegration and, hence, social harmony. The aesthetic category acted as a corridor between raw nature and a higher morality. “In a word,” Schiller wrote, “there is no other way of making sensuous man rational except by first making him aesthetic.”

91 The reformers were very interested in making “sensuous man rational.” Schiller’s importance for the reformist agenda is illustrated by an editorial in the trade periodical,

Lichtbild-Bühne (

fig. 3.3). The headline reads, “The Cultural Work of the Cinema Theater: Thoughts from the Year 1784, by Friedrich von Schiller.”

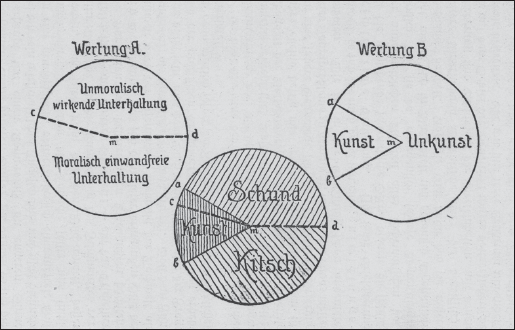

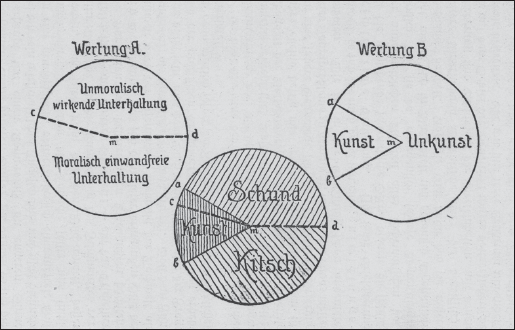

92 The essay invoked Schiller’s “The Stage Considered as a Moral Institution” to argue that cinema could function in the same manner. The aesthetic, however, was a precondition to the moral, and cinema must first go through that transformation. An illustration from a 1918 reform pamphlet illustrates the axiomatic nature of this relationship between the aesthetic and the moral (

fig. 3.4).

93 The upper-left sphere represents “entertainment with immoral effect” and “morally unobjectionable entertainment,” while the upper-right sphere signifies “art” and “non-art.” A transubstantiation occurs when the rather plain problems of morality (left) and aesthetics (right) are superimposed to reveal the nature and proportion of “art,” “trash,” and

Kitsch. We could say that this new sphere represents the issue of “taste.”

Schiller represents the beginning of a long tradition of aesthetic education in Germany, one that eventually became grafted onto questions of nationalism. The most famous, or infamous, example of this development was August Julius Langbehn’s

Rembrandt as Educator, first published anonymously and with enormous success in 1890.

94 Like Schiller and de Lagarde before him, Langbehn reacted against the perceived excessive rationalization of the Enlightenment. The preoccupation with systemization, objectivity, and book learning had, in his opinion, brought about “the decline of the spiritual life of the German people” (7). Specialization, he complained, precluded exercise of creative power: “one thirsts for synthesis” in overeducated Germany, he wrote, and so “one turns to art!” (8). The German people could be rescued from this “systematic, scholarly, cultured barbarism” by “going back to their original source of power, their individualism” (9). Furthermore, if individualism was the root of all art, and he claimed it was, and if education should correspond to the nature of its students, then art education would be the most effective and natural form of instruction. Rembrandt, even though he was Dutch, was for Langbehn “the most individual of all German artists” (11). “The scholar is characteristically international, the artist national,” he wrote, underlining the difference between science and art, word and image (11). The goal of art education, as Langbehn saw it, was to effect a spiritual regeneration of the German people by reacquainting them with their own inner nature as it was exemplified by the masterpieces of national art. But if this program sounds reasonable, most of Langbehn’s essay was noxiously antimodern, antiliberal, and even anti-Semitic, which unfortunately struck a chord among the reading public and resounded throughout German culture of the time.

95 He advocated approaches to aesthetic education rooted in national (as opposed to international/foreign) sources, but he understood the local and national in biological, racial, and ethnic terms. Progressive agendas had no place in his conception of aesthetic education.

Alfred Lichtwark, generally recognized to be the driving force behind the art education movement, also valued local artistic traditions in his address to the 1901 art education conference in Dresden. “Our education still lacks a

firm national foundation,” he declared.

96 The basis for a national culture, as with Langbehn, could be found in German art. “Up to now,” Lichtwark said, “the schools have not considered it their task to acquaint youth not only with the names, but the works of the great artists who express the German character” (104). And he blamed this lack of attention to “national art” for the lack of “formative power” in German culture. But Lichtwark’s idea of

Heimat was not rooted in blood and soil, like Langbehn’s, but rather in the historical and cultural environment in which talent and cultural forms develop; Lichtwark’s more historically contingent conception of

Heimat therefore led to a more liberal and modernist understanding of the relationship between local and national culture.

97 Yet like Langbehn, Lichtwark held that “the challenge of art education” was inseparable from “a moral renewal of our life” (99). This hope was certainly not limited to Lichtwark; most representatives of the art education movement held it as their ultimate goal.

But Konrad Lange was cautious of such sanguine hopes, asking at that same conference whether “with ‘

Kunsterziehung’ [art education] we’ve actually found the magic word to solve all social questions.”

98 If he seemed less concerned about the spiritual state of the people, he was, like Lichtwark, still very anxious about the state of German art. He acknowledged that “we actually have masters of the first order in all the areas of the fine arts, men who are living proof that the creative German spirit is not yet dead,” but claimed that this was not enough. For this relative good health to survive, it needed good soil in which to grow. “And this soil can only be the people’s understanding of art.”

99 Worried that the elements of modern urban life could undermine children’s sense of culture, Lange advocated leading them to art to maintain a sense of artistic tradition, to bring “the artistic education of our youth … in closer connection to the living, creative art of the present.”

100The education of taste was also very important to Lichtwark. To his contemporaries, he was even better known as the director of the Hamburg

Kunsthalle, which came into international prominence during his tenure. There he was instrumental in organizing groundbreaking exhibits of amateur and artistic photography, promoting local artists, and rediscovering forgotten local talents, such as the romantic painter Philipp Otto Runge. “We do not want a museum that simply stands and waits,” proclaimed Lichtwark upon assuming the directorship of the Hamburg

Kunsthalle in 1886. “Rather, we want an institution that actually works for the aesthetic education of our population.”

101 Aesthetic education, for Lichtwark, was about individual self-cultivation, of course, but it also had value for the community. Summarizing Lichtwark, Eckard Schaar writes, “Artistic cultivation is not an innate ability … but rather a participation in a national collective property that, carried by the spirit of the people, influences the soul of the individual.”

102 Lichtwark envisioned his museum as an educational center for the artistic life of the region that would focus and direct this process of individual and communal aesthetic development. It would be a clearinghouse of taste, wherein exhibits of art from around the world would help raise the sensibilities of the general public and teach new techniques to local artists. For instance, in his introduction to the first exhibit of amateur photography in 1893, Lichtwark stated that the show’s goal was to “raise the artistic taste of the public and stir interest” in the new art.

103 The development of a national art depended upon the aesthetic education of both the public and the artists—his museum would take up that task.

104Lichtwark’s influence on actual educational practices came through one of his most popular books,

Exercises in the Contemplation of Art Works. The drills consisted of Aristotelian question-and-answer sessions between teacher and student, demonstrating by example how the child’s inherent aesthetic taste could be cultivated and guided to acceptable standards. The student would gaze upon a painting and answer the teacher’s questions about its form and content until the work’s meaning would reveal itself to the child. For this process to be successful, Lichtwark stressed the importance of extended contemplation of single artworks in a quiet, conducive environment. Consistent with the

vom Kinde aus philosophy mentioned earlier, this method of aesthetic training soon gained wide favor among German art educators. Lichtwark’s system also confronted the important issue of national taste.

The typical modern German has a weakness in the area of aesthetic education. He lacks an external refinement and solidity of form as well as an inner connection to the visual arts. He has no desire for artistic pleasures that require an education of the eye and heart. His eyes see poorly and his soul not at all. For the preservation of our nation as well as our national economy, these inadequacies must be forcefully redressed.

105

Lichtwark designed his

Exercises to provide a training program for children and others who were “aesthetically weak.” By teaching youngsters how to look, gaze, and, ultimately,

see, Lichtwark was following a set of presumptions common to aesthetic education: train the eye and the heart follows. For the art education reformers of imperial Germany, then, educating public taste was a project in nation building. Simply, education

through art was a way of building a distinctly national art, while education

to art was designed to build consensus and therefore national unity, as well as maintain traditional standards and methods of evaluation. These two directions were and are common for all art education programs from Friedrich Schiller to John Dewey.

106Lichtwark’s approach caught on. A number of books in the following years staged an encounter between an imaginary viewer, a painting, and a helpful questioner.

107 Bildbetrachtung (“image viewing” or “image contemplation”) became a common method of teaching art appreciation, which emphasized the contemplative, especially the spiritual side of aesthetic education and experience. Schoolteacher Heinrich Wolgast echoed the views of many in Hamburg and elsewhere who stressed the connection between vision and spiritual development through disciplined viewing exercises: “the child who conquers the world with these more sensitive organs will reap greater rewards than one with untrained eyes,” he wrote, and “intellectual understanding of the world based on a deeper grasp of its appearances will guarantee an improved preparedness for life.”

108 Reformers such as Wolgast hoped that training the observational acuity of children and adults would result not just in spiritual but ultimately national renewal; the art education movement is therefore a good example of the explicit, parallel investment in visual education and national goals that we see consistently in discussions of positive film reform.

109 Lichtwark’s program enjoyed national visibility and increasing popularity, especially among educators interested in current ideas about visual education. The parallels were not lost on film reformers such as Lemke, Sellmann, and Häfker, who had similar educational aspirations for film.

Yet these pedagogical impulses sprang from a broader trend in visual education that suffused nineteenth-century pedagogy, for which Wolgast’s formulation could have easily served as the motto. This trend, known generally as

Anschauungsunterricht (“observational instruction” or “visual means of instruction” or simply “visual education”), started with the educational principles of Swiss pedagogue Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi (1746–1827), who believed that

Anschauung, or “sense impression” was “

the foundation of all knowledge.”

110 Anschauung is a difficult word even for Germans: in Kant’s

Critiques it is usually translated as “intuition,” but it also means “sense perception,” which are two very different things. In German dictionaries the two meanings of the word, one cognitive, one perceptual, sit side by side, matching the epistemological and phenomenological (or the knowable and visible) sides of the experiential coin. Yet

Anschauugsunterricht strove to develop the child’s innate sense of form (in the Kantian sense) through observational exercises focused on the visible world, so it thereby embraced

Anschauung’s seemingly opposed connotations. It is perhaps best understood as a process through which the pupil attains an appreciation of both the detail of the individual object and its place in a larger system, whether philosophical, taxonomic, or social. Pestalozzi’s program was notable for its then-radical approach to education. Rather than a top-down, authoritarian, deductive, and speculative method that demanded the student listen to the lecturer and recite back what was said or read in books, Pestalozzi advocated a bottom-up, democratic, inductive, and empirical approach to learning that asked the teacher to interact with the student—similar to the process in Lichtwark’s

Exercises—and trust that the student could come to a higher understanding of the material through careful observation of the object in front of him or her. It countered mere book learning and rote memorization with a program that emphasized the pedagogical power of natural objects themselves.

But it was not merely about bringing the child to an object; the method was primarily about teaching the child how to

observe. Yet as we saw in the previous chapter, observation is above all a complex logical operation, as Clive Ashwin notes about Pestalozzi’s

ABC der Anschauung (1803): “Its content was designed to activate and exercise the child’s faculties, first by distinguishing separate entities and isolating them within the perceptual manifold; secondly by enabling the child to observe and note their peculiarities of form; and thirdly by associating each form with its correct name. This integration of number, form, and word led Pestalozzi to put the

ABC der Anschauung at the centre of his educational scheme.”