Architect from Capolago, now Switzerland, who was active in Rome, where he arrived in c. 1576. There Maderno worked for his uncle, Domenico Fontana, Pope Sixtus V’s favored architect. In 1594, Fontana moved to Naples, and Maderno became an independent master. He created his façade for the Church of Santa Susanna, Rome, in 1597–1603, a design based on Giacomo da Vignola’s Il Gesù (1568–1584), with a gradual crescendo from the lateral bays to the central portal aimed at placing focus on the entrance. In 1602, Maderno also designed the Water Theater in the Villa Aldobrandini at Frascati for Cardinal Pietro Aldobrandini. The following year, he was appointed the official architect of St. Peter’s, and, in 1606–1612, he worked on the conversion of the structure into a longitudinal basilica and added a new façade. In 1628–1633, Maderno worked for the Barberini on the design of their palazzo, his most important secular commission. Maderno died in 1629, and the Palazzo Barberini was completed by Gian Lorenzo Bernini.

Sculptor possibly from Lugano who was active in Rome. Early in his career, Maderno restored antique statues for collectors but soon began executing small terracotta sculptures inspired by ancient prototypes. His most important commission is the life-size statue of St. Cecilia (1600) in the Church of St. Cecilia in Trastevere, Rome. In 1599, the saint’s body was found intact in a coffin under the church’s high altar. Pope Clement VIII commemorated the miraculous event by commissioning Maderno to create a recumbent sculpture of the saint as she had been found, with hands bound, her neck partially severed, and wearing an embroidered dress. Once Maderno completed the work, it was incorporated into the high altar, under which the saint was reburied. It became the prototype for the depiction of recumbent saints in art.

Painted by Leonardo da Vinci for the high altar of the Church of Santissima Annunziata in Florence. The commission for this altarpiece originally went to Filippino Lippi, but Leonardo persuaded the friars of the Annunziata to give him the charge instead. In 1501, Leonardo provided a cartoon for the composition (original lost; another version in London, National Gallery), which proved too large for the altarpiece’s intended frame. The cartoon was exhibited in the Annunziata monastery, and Florentines flocked to see it, including Michelangelo and Raphael, both of whom were deeply affect by it.

In the final composition, Leonardo arranged the figures to form a pyramid against an atmospheric landscape, the Virgin Mary sitting on St. Anne’s lap and holding onto the Christ Child, who grabs a lamb by the neck and ear. Clearly, Christ’s genealogy is one of the painting’s main themes. Christ grabs the sacrificial lamb to herald the Passion, which Mary tries to prevent by holding him back. In the cartoon, St. Anne points upward as if to indicate to her daughter that Christ’s sacrifice is the will of God and that it would be futile to intervene.

In the painting, Leonardo omitted St. Anne’s pointing gesture, although the melancholic tinge in her smile implies her recognition of Christ’s future suffering. The cascade of movement from upper left to lower right, heightened by Mary’s graceful bend, is an enhancement to the original composition, where mother and daughter sat almost side by side. Leonardo did not complete the work, and when he moved to France in 1517, to serve Francis I, he took the painting with him, along with his Mona Lisa (1503; Paris, Louvre) and St. John the Baptist (c. 1513–1516; Paris, Louvre), keeping it until his death in 1519, when it entered the French royal collection.

Painted by Federico Barocci for the Confraternity of the Misericordia in Arezzo. The Madonna del Popolo shows the people of Arezzo below an apparition of the Virgin, who intercedes on their behalf. Some of the figures point to the vision, while others go about their daily routines without noticing the event. A woman returns from the market with a child in her arms; a beggar lies on the ground while a man offers him alms. The Virgin seems to be asking her son to illuminate those who are blind to the true faith, and in response, he sends the Holy Spirit so they may be saved. Barocci enhanced the figures’ appeal by adding touches of pink throughout the pictorial surface, common to his art. This work represents the artist’s early Mannerist phase. Consequently, the composition is oval, with a void in the center and a large number of figures populating the picture, most in contorted poses. Barocci would eventually shed the Mannerist style in favor of greater clarity and deeper emotional content in response to the demands of the Council of Trent and the Counter-Reformation.

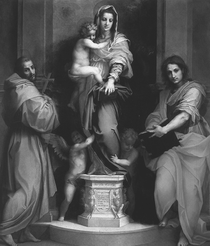

Painted by Andrea del Sarto for the Convent of San Francesco dei Macci. An unconventional representation, the Virgin is shown standing on a pedestal decorated with harpies, mythological monsters who carry away the souls of the dead and minister punishment. Also on the pedestal are inscribed the first lines of the hymn to the Virgin of the Assumption, which explains why the two putti at Mary’s feet seem to be pushing her upward.

The work has been the subject of much discussion because the inclusion of the harpies is not well understood. Identified variously as harpies, sphinxes, sirens, and other mythical creatures, they have inspired readings that range from symbols of paganism superseded by the triumph of Christianity to sin conquered by the Virgin’s purity. Some believe that del Sarto’s Mary is the woman of the Apocalypse described in the Book of Revelations who engages in a spiritual battle against demons or the embodiment of the Immaculate Conception who tramples the dragon of evil.

In the painting, Mary is flanked by St. Francis and St. John the Evangelist, this last figure based on one of the males holding a book in Raphael’s School of Athens in the Stanza della Segnatura (1510–1511) at the Vatican. St. John is there because he authored one of the Gospels where the story of salvation is told (and the Book of Revelations). St. Francis is the patron of the Poor Claires, who resided in the monastery for which the work was painted.

Painting by Titian. The Madonna of the Pesaro Family was commissioned by Jacopo Pesaro, Bishop of Paphos, Cyprus. Following the prescriptions of Giovanni Bellini and Giorgione for the depiction of the enthroned Virgin and Child, Titian placed these saintly figures on an elevated throne against a landscape, with two large columns flanking them. Titian, however, elaborated on the format by relegating the throne to the side and placing St. Peter, not the customary musical angels, at the foot of the throne—his key to Heaven’s gate prominently displayed. The armored figure on the lower left presents a Turkish captive to the Virgin and Child to refer to Jacopo’s triumph over the Turks in 1502, at Santa Maura, while commanding the papal naval ships. The diagonal formed by the throne, saint, and armored and captive figures makes for a dynamic rendition. At either side of the Virgin are members of the Pesaro family kneeling, with St. Francis, founder of the Franciscan Order, to which the Church of Santa Maria dei Frari belongs, on the right petitioning the Virgin to view the Pesaro family favorably. Above, heavily foreshortened putti support the cross on which Christ will be crucified. Yet, the Christ Child seems oblivious to his future fate as he plays with his mother’s veil. This playful detail shows Titian’s interest in stressing the human aspect of his religious characters.

Painted by Leonardo da Vinci for the Church of San Francesco Grande in Milan, a commission received from the Confraternity of the Immaculate Conception. Two of Leonardo’s pupils and an independent sculptor were also involved in the project, which was to include side panels depicting musical angels and a sculpture of the Immaculate Conception to be placed either above or below the altarpiece. Leonardo’s figures form a pyramidal composition, with the Virgin in the center, embracing the young St. John the Baptist and holding up her foreshortened hand in a protective gesture above her son’s head. The Christ Child, in turn, blesses his cousin, the Baptist, while the angel on the right points to St. John and looks in our direction. The scene takes place in a grotto, a reference to the Holy Sepulcher where Christ was buried after the Crucifixion. The light that seeps through the rocks in the background denotes the salvation Christ will bring to humanity, made possible by Mary, the immaculate vessel who brought on his incarnation.

Here, Leonardo adds a sense of mystery to the work by using his characteristic sfumato technique, while his interest in botany is reflected in the accurate rendering of the plants in the foreground. A second version of this painting exists (fin. c. 1506; London, National Gallery), which lacks the subtleties of the earlier composition, betraying the heavy intervention of assistants. The Madonna of the Rocks presents the poetic beauty for which Leonardo is so well known and reflects his keen observation of the nuances of nature and desire to replicate them faithfully on the painted surface.

Painting by Anthony van Dyck. The Madonna of the Rosary is part of a series van Dyck rendered on the life of St. Rosalie, patron saint of Palermo, Sicily. It is the largest work the artist created during his stay in Italy and one of his finest altarpieces. Commissioned in 1624, to celebrate the recovery of the saint’s remains, the work also was meant as appeal on behalf of the people of Palermo for deliverance from the plague that was devastating their city. The Madonna of the Rosary shows the Virgin Mary and Christ Child appearing to Rosalie and her companions in a heavenly burst of clouds and angels. Below, a nude child holds his nose, a traditional reference to death and decay, and points to those who are stricken. The overall composition borrows heavily from Peter Paul Rubens’s St. Gregory Surrounded by Saints (c. 1608; Grenoble, Musée), a work he placed on his mother’s tomb in the Abbey of St. Michael in Antwerp, where van Dyck would have seen it. The lush brushwork and vivid colorism not only come from Rubens, but also from van Dyck’s direct study of the works of the Venetians, particularly Titian. When van Dyck painted this work, no precedents on the depiction of St. Rosalie existed; therefore, it shows his inventiveness in formulating a new standard of visual of representation.

Work executed by Michelangelo while training in the Medici household, illustrating his admiration for Donatello. The Madonna of the Stairs not only recalls Donatello’s Pazzi Madonna (1420s–1430s; Berlin; Staatliche Museen), but it also uses the older sculptor’s relievo schiacciato technique. Michelangelo also looked to ancient statuary, particularly funerary stelae, a proper choice, as his scene foreshadows the future death of Christ. As in the ancient examples, Michelangelo’s relief is permeated by a quiet, somber mood. In the foreground, the Virgin, here presented as the “Stairway to Heaven” by her juxtaposition to the stairs, partially covers the Christ Child with her mantle to denote the future wrapping of his body with the shroud in preparation for burial. In the background, wingless angels spread the shroud in anticipation of the event. Executed by Michelangelo while in his teens, the Madonna of the Stairs demonstrates that he was already capable of rendering anatomy and drapery folds accurately and that his interest in challenging himself to render complex poses began at an early age.

Painting rendered by Parmigianino for Elena Baiardi to be placed in her family chapel in the Church of Santa Maria dei Servi, Parma. The Madonna with the Long Neck is the artist’s best-known work and exemplifies his mastery at rendering graceful, elegant scenes. The elongations, ambiguities, and incompatible proportions qualify the work as Mannerist. The large Virgin in the center of the composition is reminiscent of the monumental, powerful sibyls rendered by Michelangelo on the Sistine ceiling, Vatican (1508–1512). Her opened toes, shown prominently in the foreground, in fact replicate those of Michelangelo’s Libyan Sibyl. The sleeping Christ Child, in turn, is based on the pose of the dead Christ sprawled across Mary’s lap in Michelangelo’s Vatican Pietà (1498/1499–1500), his grayish, corpse-like complexion alluding to his future death on the cross. The row of classical columns in the background parallel the columnar posture and neck of the Virgin, and possibly refer to the Old Law of Moses, now superseded by the New Law of Christ. The diminutive male figure in the background holding an opened scroll is believed to be one of the prophets who foretold the coming of the Lord. This emphasis on symbolic elements that at times prove difficult to decipher is part of the Mannerist style and categorizes the work as one of the movement’s grand masterpieces.

Created by Duccio, then the leading painter of the Sienese School. The Maestà Altarpiece was intended for the main altar of the Cathedral of Siena. A freestanding polyptych painted on both sides, the altarpiece was removed from its original site in 1506 and dismantled to make way for a new decorative program. The scenes from the predella and pinnacles were scattered and are now in various museums throughout the world; some, regrettably, were cut down, and two are missing. This has fueled much debate as to the original order of placement of the scenes and the subjects represented in the lost panels.

In the central panel is an Enthroned Virgin and Child in majesty (hence the appellation Maestà), surrounded by angels, appropriate to the cathedral of a city whose patroness is the Virgin. Sts. Ansanus, Savinus, Crescentius, and Victor, also patrons of Siena, kneel at Mary’s feet, while an inscription at the foot of her throne reads, “Holy Mother of God, be the cause of Siena, of life to Duccio as he has painted you in this manner.” Behind the figures are three-quarter-length representations of prophets holding scrolls. The back of the main panel features the Passion of Christ, while the predella scenes are from Christ’s infancy and the pinnacles from the life of the Virgin. The almond-shaped faces of the figures, use of black to denote shadows, and heavy gilding betray the dependence on the Maniera Greca tradition established in the region by Coppo di Marcovaldo and Guido da Siena.

In 1311, when the altarpiece was completed, the Sienese citizens carried it from Duccio’s workshop to the cathedral in a grand procession led by the bishop and other members of the clergy. Candles were lit around it, bells rung, bagpipes and trumpets played, and prayers were carried out in front of it. Siena could now boast of an artist as grand as Giotto, active in the enemy Republic of Florence.

Painter of Milanese and Portuguese descent. Maino was active in Spain in the courts of Philip III and Philip IV. The details of his training are not completely clear. Considered by most to have been one of El Greco’s pupils, one 17th-century source states that Maino was a student and friend of Annibale Carracci, as well as a close companion of Guido Reni. By 1611, Maino is documented in Toledo, where two years later he took vows at the Dominican Monastery of St. Peter Martyr. In 1614, Philip III called him to Madrid and appointed him drawing master to his son, future king Philip IV. At court, he excelled in the area of portraiture, although he is best known for the religious canvases he created. Among these are the Adoration of the Magi and the Adoration of the Shepherds (both 1612–1613; Madrid, Prado), both rendered for the Monastery Church of St. Peter Martyr.

Maino’s most important commission is the Recapture of Bahia (1634–1635; Madrid, Prado) for the Hall of Realms in the king’s Palace of El Buen Retiro, an event that took place in 1625, led by Gaspar de Guzmán y Pimentel, Count Duke of Olivares and first minister to Philip IV, whom Maino included in the painting. Here, Bahia is recovered from the Dutch, who kneel in front of Philip IV’s portrait. The wounded tended to in the foreground, modeled after traditional images of the Pietà, add an aura of sentimentalism and cast the victors as benevolent toward their enemies. In these works, Maino’s style is closely tied to that of the members of the Carracci School in its choice of colors and idealization of forms, giving credence to the contemporary reports that Maino received his training in Italy.

Italian sculptor and architect from Siena. In 1308, Maitani was summoned to Orvieto to reinforce the apse and transept of the city’s cathedral, which had weakened. In 1310, he was appointed Director of Cathedral Works, a position he held until his death in 1330. In this capacity, he was charged with the design of the cathedral’s façade and its reliefs, which include scenes from the Book of Genesis (from the Creation to the descendants of Cain), the Tree of Jesse, the prophecies of the coming of Christ and his sacrifice for humanity, the story of salvation, the Last Judgment, the Resurrection, and paradise. Also attributed to Maitani is the Enthroned Virgin and Child, revealed by angels who part the curtains of the canopy that contains them above the cathedral’s west portal. Maitani’s style in these reliefs is closely tied to the medieval tradition and is characterized by busy scenes with figures in contorted poses. For this, he is classified as one of the most expressive sculptors of the Proto-Renaissance era.

Tyrant ruler of Rimini, a charge he obtained in 1432, at the age of 14. Malatesta was excommunicated in 1462, by Pope Pius II, and cast to Hell in front of St. Peter’s on charges of impiety and sexual misconduct related to the suspicious death of his wife, Polissena Sforza (1449), probably from poisoning. In 1450, Malatesta had commissioned Leon Battista Alberti to complete the Tempio Malatestiano, begun by Matteo de’ Pasti as a renovation of a church already on the site that housed the funerary chapels of his ancestors. By the time Alberti became involved in the project, Malatesta had decided to convert the structure into some sort of pagan shrine that spoke of his glory as ruler. He retrieved the remains of famous men, including Greek humanist and Neoplatonist Gemistus Pletho, an advocate of paganism whose body Malatesta had discovered during the 1465 campaign against the Turks in the Morea, when he commanded the Venetian army. The project gave the pope added ammunition in his defamation campaign against Malatesta. Malatesta was also the patron of Antonio Pisanello and Piero della Francesca.

A painter from the town of Nijmegen, now Holland, who was the uncle of the Limbourg brothers. Malouel is known to have worked for Isabella of Bavaria, wife of Charles VI of France (d. 1435), and in 1396, he is recorded as court painter to Philip the Bold, Duke of Burgundy, a charge he fulfilled until his death in 1415. For Philip he rendered five large panels for the Chartreuse de Champmol in Dijon, where he also was charged with painting and gilding Claus Sluter’s Well of Moses (1395–1406; Dijon, Musée Archéologique). One of the five panels is perhaps the Martyrdom of St. Denis (fin. c. 1416; Paris, Louvre), believed to be the painting for which Henri Bellechose, Malouel’s pupil, received pigments to complete it after his master’s death. The work shows Denis, patron saint of France and first bishop of Paris, receiving his last communion on the left and undergoing his decapitation on the right, with Christ’s Crucifixion in the center, the cross held by God the Father.

Also attributed to Malouel is the Pietà in the Louvre (c. 1400), a tondo (circular panel) that brings the scene close to the picture plane to evoke piety from viewers. The work combines the Pietà theme with the Holy Trinity, as it is God the Father who supports the bloodied body of Christ, while the Holy Dove hovers between them. The coat of arms of France and Burgundy painted on the panel’s reverse denotes that this work was also rendered for Philip, and perhaps the Chartreuse de Champmol. Malouel was among the artists who translated the French Gothic miniaturist tradition to large-scale painting. His gilded backgrounds, rich patternings, and elongated forms qualify him as one of the luminaries of the International Style.

An early portrait by Titian. It is not clear who is depicted in the Man with Blue Sleeve, although art historians have suggested that it may be poet Ludovico Ariosto. Some view the work as a self-portrait, while others believe the man to be a member of the Barbarigo family, among Titian’s earliest patrons. Regardless of the sitter’s identity, the work represents a major step forward in the development of portraiture. Previously, sitters were presented in a formal, static pose, and the emphasis was on opulence and social status. Titian exchanged luxury for visual richness by loosening his brushwork and placing the man’s body in an informal profile pose with a sharp turn of the head toward the viewer and a self-assured facial expression. His arm, clad in the blue sleeve, hangs over a parapet and seems to break into the viewer’s space. The foreshortenings, lively pose, and character of the man depicted infuse the work with a dynamism never before seen in this genre. With this, Titian broke away from the Renaissance emphasis on permanence and opened the doors for future experiments in portraiture on the capturing of a moment in time on the pictorial surface.

Dutch Mannerist painter who authored the Schilderboeck (first published in 1604), a biographical compendium of artists and their works from the ancient era to the author’s days. For art historians, this book is one of the major sources of information on the lives of the Northern masters of the 15th and 16th centuries. For this, van Mander has been called the “Vasari of the North.” Van Mander was in Rome from 1573 to 1577, and it is there that he became aware of Giorgio Vasari’s Lives of the Artists, which inspired him to write the Schilderboeck. It is also there that he was exposed to the Mannerist mode he adopted as his own. He spent some years wandering through the Netherlands, finally settling in Haarlem in 1583, where, together with Hendrik Goltzius and Cornelis van Haarlem, he established an academy and developed a Dutch Mannerist style. Van Mander died in Amsterdam, where he spent the last two years of his life. Among his most notable works are The Flood (c. 1583; Haarlem, Frans Halsmuseum), the Continence of Scipio (1600; Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum), and the Garden of Love (1602; St. Petersburg, Hermitage Museum).

(In Italian, “almond.”) An almond shape used in art to surround saintly figures, for instance, the Virgin Mary or Christ, to denote their divinity. The device is more common in works belonging to the Proto-Renaissance era, for example, the Strozzi Altarpiece (1354–1357) in the Strozzi Chapel at Santa Maria Novella, Florence, by Andrea Orcagna, where Christ is centered in a mandorla and surrounded by seraphim. In the Baptistery of Padua, in Giusto de’ Menabuoi’s fresco (c. 1378), the Virgin is enclosed in a mandorla and hovers above the entrance to the tomb of Fina Buzzacarini, the patron. A work that belongs to the Early Renaissance that uses the device is the Sansepolcro Altarpiece by Sassetta (1427–1444; Borgo di Sansepolcro, Church of San Francesco), where St. Francis, enclosed in a mandorla, hovers above the sea with the Franciscan virtues of Charity, Poverty, and Obedience above him.

Painter from Haarlem whose fantastic works are closely related to those of Hieronymus Bosch. Mandyn is recorded in Antwerp in 1530, with Gillis Mostaert and Bartholomeus Spranger figuring among the pupils in his workshop. His Temptation of St. Anthony (1547; Haarlem, Frans Halsmuseum) is his only signed work and has served as the basis for reconstructing his career. Like Bosch’s fantasies about the follies of humanity, Mandyn’s painting presents a landscape littered with bizarre objects and monstrous creatures who hassle the saint as he prays for strength. Mandyn was somewhat more conservative than Bosch in the peculiarities of his scenes, although they possess as much visual richness as Bosch’s compositions. Other works by Mandyn include the St. Christopher with the Christ Child (c. 1550) at the Los Angeles County Museum and the Landscape with the Legend of St. Christopher (early 16th century) at the St. Petersburg Hermitage.

Italian painter whose career is not well documented. Manfredi was born in Ostiano, near Mantua, and went to Rome sometime between 1600–1606, where he became one of Caravaggio’s closest followers. Giovanni Baglione wrote that Manfredi in fact worked in Caravaggio’s studio as his assistant and servant. His Gypsy Fortune Teller (c. 1610–1615; Detroit Institute of Arts) depicts a subject also tackled by Caravaggio (c. 1596; Rome, Capitoline Museum). Like his master, Manfredi used half-figures set against a dark, undefined background and lit through the use of theatrical chiaroscuro. His Cupid Punished by Mars (1605–1610; Chicago, Art Institute) relates compositionally and thematically to Caravaggio’s Amor Vincit Omnia, and his Guardroom (c. 1608; Dresden, Gemäldegalerie) borrows from Caravaggio’s Cardsharps (1595–1596; Forth Worth, Kimbell Museum of Art). Manfredi was responsible for transmitting the Caravaggist mode of painting to the foreign masters who visited Rome in the early decades of the 17th century, particularly from France and the Netherlands.

A term used to describe the Greek or Byzantine mode of painting adopted in Italy by artists of the Proto-Renaissance era. It is characterized by the heavy use of gilding, brilliant colors, striations to denote the folds of fabric, and segments for the figures’ anatomical details. Among the artists who adopted the Maniera Greca style are Berlinghiero Berlinghieri, Bonaventura Berlinghieri, Coppo di Marcovaldo, Guido da Siena, and Cimabue, who is said to have brought it to its greatest refinement. Giotto is the first master to have rejected the Maniera Greca mode in favor of greater naturalism and convincing emotive content, revolutionizing the art of painting.

An art movement that emerged in roughly the 1520s, inspired by the unprecedented architectural forms Michelangelo introduced in the vestibule of the Laurentian Library (1524–1534) and the Medici Chapel (New Sacristy of San Lorenzo, Florence, 1519–1534), as well as the sculptural figures in this last commission, with their exaggerated musculature and unsteady poses. Mannerists purposely denied the strict classicism and emphasis on the pleasing aesthetics of the High Renaissance and instead embraced an anticlassical mode of representation that entailed the use of illogical elements, jarring colors and lighting, contorted figures, and ambiguous iconographic programs. The early exponents of this movement were Jacopo da Pontormo and Rosso Fiorentino. These artists favored circular compositions with a void in the center; scenes that move up instead of logically receding into space; abrupt color combinations; and harsh lighting that ignores the subtle Renaissance gradations from light, to medium, to dark. Rather than looking to nature for inspiration, these masters looked to Michelangelo, the result being an art that can be categorized as self-consciously artificial, highly sophisticated, and cerebral.

The pioneer of Mannerist architecture was Giulio Romano, who designed for Duke Federigo Gonzaga of Mantua the Palazzo del Tè (1527–1534), a structure with asymmetrical placement of pilasters, stringcourses that are interrupted by massive keystones, and pronounced rustications on the exterior surfaces. Mannerism soon spread to other parts of Italy and Europe. Perino del Vaga brought the vocabulary to Rome and Genoa; Domenico Beccafumi to Siena; Correggio to Parma; and Parmigianino to Parma, Rome, and Bologna. A second wave of Mannerist artists emerged toward the middle of the 16th century, including Agnolo Bronzino, Giorgio Vasari, and Federico Barocci. Benvenuto Cellini, Bartolomeo Ammannati, and Giovanni da Bologna translated the Mannerist idiom into sculpture, and Ammannati and Vasari also applied it to architecture.

Rosso Fiorentino and Francesco Primaticcio traveled to France to work in the court of King Francis I. At the Palace of Fontainebleau, they invented a new type of decoration that combined stucco, metal, and woodwork with painting and sculpture, establishing what today is known as the Fontainebleau School, a French version of Mannerism. In the Low Countries, Mannerism was adopted by a group of masters known as the Romanists, among them Jan Gossart, Joos van Cleve, Bernard van Orley, and Jan van Scorel.

French architect first trained by his father, who was a carpenter. When his father died in 1610, Mansart completed his training with his brother-in-law, architect Germain Gaultier, who had collaborated with Salomon de Brosse. No evidence exists to confirm that Mansart was in Italy. Yet, he was familiar with the Italian architectural vocabulary, already fairly well represented in France through the work of de Brosse and Jacques Lemercier. By now, the treatises of Vitruvius, Andrea Palladio, and Giacomo da Vignola had been translated into French and made available to local masters. Also available were books with reproductions of the monuments from antiquity, on which the Renaissance architectural vocabulary of Italy was based.

Mansart’s first recorded commission was the façade of the Church of Feuillants in Paris (1623–1624; destroyed; known only through engravings), a work based on de Brosse’s Church of St. Gervais. Mansart added a tall screen above the segmented pediment in the manner of Jean du Cerceau and volutes (spiral scrolls) at either side of the upper story with rusticated pyramids at either end to differentiate his work from that of de Brosse. Mansart correctly applied the Colosseum principle to the structure, with the Ionic order below the Corinthian. The commission was followed by the Château de Berny (1623–1624), of which only a portion of the court façade survives. Here Mansart provided a freestanding structure with independent roofs, at the time a major departure from the usual French château type. He also added some curvilinear forms along the court to add movement to the structure and flanked it with quadrant colonnades.

The Château de Balleroy (c. 1631) is one of the few buildings by Mansart to have survived in its original condition. Built for Jean de Choisy, Chancellor to the Duke of Orleans, the structure is fairly small in size, so Mansart emphasized its vertical axis to add to its monumentality. The building sits on a terrace accessed by semicircular stairs that break the monotony of the rectilinear forms. The central block is composed of three stories and crowned by a pitched roof with dormers. The side blocks mimic these forms, yet their height is decreased so as not to compete with the central block.

Other domestic structures by Mansart include the Château de Blois (1635–1638) built for Gaston d’Orléans, Louis XIII’s brother, and the Château de Maisons (1642–1646) for René de Longueil, the king’s Président des Maisons. In the mid-1640s, Mansart also provided a design for the Church of Val-de-Grâce commissioned by Anne of Austria, Louis XIII’s wife, who passed the work onto Lemercier after a year, as Mansart ignored budgetary constraints and kept making changes to his plans. Mansart, in fact, is known to have had a belligerent personality, which cost him not only this commission, but also many others. Toward the end of his life, he fell into oblivion, receiving only sporadic work from patrons. Today, Mansart is considered one of the most proficient and influential architects of 17th-century France.

The leading painter of the Early Renaissance in Northern Italy; a master of perspective and foreshortening. Mantegna was born near Padua, where he was trained by painter Francesco Squarcione, who was also an art collector and dealer. From Squarcione Mantegna developed a keen interest in antiquity and learned to read Latin. His interest in the ancient world peaked when he became a member of a group in Verona that engaged in archaeological studies and often took boat rides on Lake Garda to read the classics. In 1453, Mantegna married Nicolosia, the daughter of Jacopo Bellini, becoming a member of the Bellini dynasty of painters.

His earliest commission is the Ovetari Chapel in the Church of the Ere- mitani in Padua (1454–1457). The contract for the work had to be signed by his brother, as Mantegna was considered too young to do so himself. The patron was Imperatrice Capodilista, wife of Antonio di Biagio degli Ovetari, who left funds in his will for the project. The scenes chosen were from the life of St. James. Unfortunately, these were lost to allied bombing during World War II and are only known through the few remaining fragments and photographs taken before their destruction. The photos reveal Mantegna’s understanding of the Florentine vocabulary and technical advancements in perspective. They also disclose the influence of Donatello, as Mantegna’s figures are as solid as the sculptor’s. In Mantegna’s St. James Led to his Execution, part of the Ovetari frescoed program, one of the soldiers is, in fact, based on Donatello’s St. George from Orsanmichele, Florence (1415–1417).

From 1456 to 1459, Mantegna painted the San Zeno Altarpiece for the Church of San Zeno in Verona. Here the elaborate architectural framework, created in a classical vocabulary, interacts with the painted image in that its columns are made to match precisely the painted piers in the foreground. Mantegna carried the classical idiom into the image itself by placing the enthroned Virgin and Child, musical angels, and saints in a chamber with piers that support a continuous all’antica frieze with garlands and putti. Here again, Donatello’s influence is noted in the overall composition. The architectural and figural arrangements depend on Donatello’s altar in the Church of San Antonio (il Santo) in Padua.

Mantegna’s Agony in the Garden (mid-1450s; London, National Gallery) is based on one of the drawings Jacopo Bellini created for teaching purposes. The work reveals Mantegna’s mastery at rendering foreshortened figures, specifically the sleeping Apostles in the foreground. In the middle ground, Judas leads the Romans to Christ, and in the background, the city of Jerusalem is shown as an ancient Roman city. To this period also belongs Mantegna’s St. Sebastian (1457–1458; Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum), which shows the saint amid Roman ruins. A foot fragment from an ancient statue is juxtaposed to the saint’s foot to denote that Mantegna learned well his lessons from the ancient masters.

In 1459, Mantegna moved to Mantua, where he became court painter to Duke Ludovico Gonzaga. There he remained until his death, painting altarpieces and frescoes, and designing pageants. The most significant work Mantegna carried out in these years is the decoration of the Camera Picta (“Painted Chamber”) in the Mantuan Ducal Palace (1465–1474). Also known as the Camera degli Sposi (“Room of the Married Couple”), the frescoes in this chamber record contemporary events in the Gonzaga’s lives. The architecture in the scene continues that of the actual room, and figures climb fictive steps to reach the real mantel above the fireplace. The most illusionistically successful scene is on the ceiling, where a painted oculus (rounded opening) provides a view of the sky. On a balustrade around the oculus, putti and servants in exaggerated foreshortening look down at the viewer and smile. Even more remarkable is Mantegna’s Lamentation over the Dead Christ (c. 1490; Milan, Pinacoteca di Brera), also painted in Mantua. Here, the corpse lays on a slab that is perpendicular to the picture plane, permitting a clear view of Christ’s wounds. At his side, Mary and St. John weep uncontrollably, inviting viewers to do the same. This work was inspired by Andrea del Castagno’s Death of the Virgin in the Church of San Egidio, Florence (destroyed in the 17th century), which Mantegna saw when he traveled to that city in 1466 and again in 1467.

The engravings Mantegna produced from the 1490s onward disseminated his style in Northern Europe, where Albrecht Dürer is known to have copied them to perfect his own skills. For Dürer, Mantegna represented an example of classicism. In Italy, however, Mantegna touched future masters mainly for his illusionistic devices. His foreshortenings in the Camera Picta became the catalyst for the illusionistic ceilings of the next three centuries.

Manueline is an architectural style typical of early 16th-century Portugal. It is called Manueline because it was developed during the reign of Manuel I (1495–1521). Since at the time Portuguese economy depended on maritime trade and riches were pouring into the area due to recent land discoveries, the Manueline style often features a profusion of nautical applied ornamentation, for instance, barnacles, seaweed, shells, buoys, ropes, anchors, and navigation instruments. These maritime motifs usually meld with elements from Late Gothic, Plateresque, Mudéjar, Flemish, and Italian architecture. Many of the buildings built in Lisbon in the Manueline style were lost to the earthquake of 1755, although a few examples remain, most notably the Mosteiro dos Jerónimos by Diogo de Boitaca and Juan de Castilho, and the fortified Torre de Belém by Francisco de Arruda.

St. Margaret was the daughter of a pagan priest from Antioch who banished her when she converted to Christianity. Margaret went to the countryside, where she became a shepherdess, and there she was able to practice her faith freely. She rejected the advances of Governor Olybrius, who, in retaliation, ordered her torture and imprisonment. While captive, the devil appeared to her in the form of a dragon and swallowed her. Margaret carved her way out of the belly of the beast with a small crucifix she always carried with her. The following day, attempts were made to end her life by fire and drowning, but both efforts were futile, as she miraculously emerged unscathed from the flames and water. The thousands of individuals who witnessed the event were immediately converted and executed. Margaret herself was finally beheaded.

Because she carved her way out of the dragon’s belly, Margaret is the patron saint of childbirth. She is included in that capacity on the bedpost in Jan van Eyck’s Arnolfini Wedding Portrait (1434; London, National Gallery). In Francisco de Zurbarán’s depiction of the saint (1634; London, National Gallery), she stands alongside the dragon, her dress and hat that of a shepherdess. She is also included in Friedrich Herlin’s Family Altarpiece (1488; Nördlingen, Städtisches Museum), where she presents female donors to the Virgin and Child.

A Hapsburg and the daughter of Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I. At the age of two, Margaret was betrothed to future king Charles VIII of France. Instead, in 1489, Charles married Anne of Brittany and sent Margaret back to her father’s court. In 1497, she married the Infante Juan, heir to Isabella of Castile and Ferdinand of Aragon. Widowed a few months later, in 1501, she wed Philibert II, Duke of Savoy, who also died (1504). Her father then appointed her regent to the Netherlands (1507) and guardian to Charles V, whom she made her universal heir.

Margaret was a major collector and patron of the arts. Bernard van Orley and Jan Mostaert were her court painters, and Conrad Meit her sculptor. A portrait of Margaret rendered by van Orley in the Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts, Brussels, records her likeness. Mostaert’s Portrait of an African Man (1520–1530, Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum) is thought to represent an individual from her court in Malines. Meit created a number of small- and large-scale sculptures for her, as well as portraits. He was charged with overseeing the execution of the tombs of Margaret and her husband Philibert in the Church of Brou in Bourg-en-Bresse (1526–1532). Margaret’s collection included such notable works as Jan van Eyck’s Arnolfini Wedding Portrait (1434; London, National Gallery) and Jan Gossart’s Metamorphosis of Hermaphrodite and Salamacis (c. 1505; Rotterdam, Museum Boymans-van Beuningen).

Wife of Henry VII of Luxemburg, who was crowned King of Germany in 1309. He invaded Genoa in October 1311, when Margaret, who accompanied him, fell ill and died two months later. Henry commissioned Giovanni Pisano to create a monument to be placed above his wife’s tomb in the Church of San Francesco di Castelletto in Genoa (now in Genoa, Museo di Sant’Agostino). The monument was dismantled and removed from its original location in the late 18th century when San Francesco was demolished. In its present state, it is nothing more than a seated effigy of the queen. Originally, however, it included a marble sarcophagus and other figures. Some of the extant pieces are three figures from a scene representing Margaret’s resurrection, two angels, a figure of Justice holding a scroll, a head representing Temperance, and a fragment of a Virgin and Child. This was probably a wall tomb, as evidenced by the unpolished backsides of the extant sculptures. The scene of Margaret’s resurrection may have been contained in a lunette above the sarcophagus, and the Virtues must have surrounded the effigy.

French painter and manuscript illuminator from Amiens who was praised by poet Jean Lemaire de Belges as the “prince of illuminators.” As a member of a family of painters, Marmion probably received his training from his father. He settled in Valenciennes sometime in the 1540s, and there he established his own independent workshop. In 1454, he was summoned by Philip the Good to work for him on the decorations of a lavish banquet. From this point onward, Marmion regularly worked for the Burgundian court, also serving Philip’s son, Charles the Bold, and Charles’ wife, Margaret of York.

Although a number of manuscript illuminations, including the Crucifixion in the Pontifical of Sens (c. 1467; Brussels, Bibliothèque Royale, Ms. 9215, fol. 129), can be given to Marmion with certainty, his large-scale paintings are not as well documented. Among these is the Lamentation (early 1470s) at the New York Metropolitan Museum, which bears the arms and interlaced initials of Charles and Margaret on the verso. The painting’s small scale denotes that it was meant for use in private devotion. Other works by Marmion are in the Philadelphia Museum of Art, namely his Pietà and St. Jerome and a Cardinal Praying, both dating to the last quarter of the 15th century. The angular forms of Marmion’s draperies, brilliant colors, and emphasis on detail and drama define his works as Flemish.

Painted by Paolo Veronese for the same monks who commissioned Tintoretto to paint the Last Supper (1592–1494) in their monastery church. The marriage at Cana represents the first miracle effected by Christ. He and the Virgin Mary were invited to a wedding. When the hosts ran out of wine, Christ turned water from the jugs, seen on the right foreground, into wine. The scene is a noisy, dynamic composition similar to Tintoretto’s Last Supper; however, while Tintoretto rendered humble figures, Veronese emphasized the opulence of brocade silks and tableware. The result is a scene that looks more like a contemporary Venetian wedding celebration than a solemn representation of a miraculous event. Christ and Mary sit in the center of the table and are the only figures who neither move nor engage in conversation. They are also the only to feature halos. The foreground includes a playful cat and several dogs patiently waiting for a morsel to fall. In front of the table are musicians who entertain the guests. These are portraits (from left to right) of artist Jacopo Bassano, Veronese himself, and Titian. With their inclusion, Veronese made his case for painting as a liberal art comparable to music.

The scene stems from Jacobus da Voragine’s Golden Legend. Mary had many suitors, so the high priest in the temple asked them to present rods to him. Joseph, who held the rod that bloomed, was granted Mary’s hand in marriage. In versions by both Pietro Perugino (1500–1504; Caen, Musée des Beaux-Arts) and Raphael (1504; Milan, Brera), the marriage takes place in front of the temple and is officiated by the high priest. Joseph holds the blooming rod in one hand and puts the ring on the Virgin’s finger with the other. Among the other suitors, the one next to Joseph breaks his rod over his knee in frustration, while next to Mary stand the other maidens from the temple. Guercino painted the marriage (1649; Fano, Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio) as a more intimate event, inside the temple with only the Virgin, Joseph, the high priest, and two women present. The temple’s tabernacle behind the high priest and the canopy above the figures places the work in its proper historical setting. The scene was also depicted by Giotto (1305; Padua, Arena Chapel), El Greco (c. 1612; Bucharest, Art Museum), and Nicolas Poussin (1640; Grantham, Belvoir Castle; second version Edinburgh, National Gallery of Scotland).

The mythological god of war. Mars is the son of Jupiter and Juno, and his attributes are the helmet, shield, and spear or sword. His illicit affair with Venus was discovered by Vulcan, her consort. In retaliation, Mars punished Cupid for causing him to fall in love with the goddess, an episode rendered by Bartolomeo Manfredi in his Cupid Punished by Mars (1605–1610; Chicago, Art Institute). In Sandro Botticelli’s Mars and Venus (c. 1482; London, National Gallery), the god is shown asleep, perhaps to denote the power of love over war. In Paolo Veronese’s Mars and Venus United by Love (c. 1570; New York, Metropolitan Museum), the coupling of these two figures carries similar connotations, in this case of political significance to Emperor Rudolf II of Prague, who commissioned the work. Diego Velázquez (1638; Madrid, Prado) showed Mars at the foot of the bed after his amorous encounter with Venus and discovery by Vulcan, while Annibale Carracci presented him paying the adulterer’s fee in the background of his Venus Adorned by the Graces (1594–1495; Washington, D.C., National Gallery).

Martha is the sister of Mary, who is often conflated with Mary Magdalen, and Lazarus. Christ often visited their home, and on one such occasion, Martha complained to him that her sister was listening to his words rather than tending to her chores. Christ retorted that it was Mary who had chosen the “better part.” This is the scene Diego Velázquez depicted in his Christ in the House of Mary and Martha (c. 1620), at the National Gallery in London. With this episode Martha came to symbolize the active Christian way of life and her sister Mary the contemplative existence.

Martha is usually included in scenes of the Raising of Lazarus, as in Giotto’s rendition in the Arena Chapel, Padua, of 1305, and Caravaggio’s of 1609 (Messina, Museo Nazionale). In fact, she is the one who called on Christ after her brother’s death to bring him back to life. Martha and her siblings went to France after Christ’s death. There in the woods between Arles and Avignon, a dragon threatened the inhabitants of the region. Martha found the creature in the woods hurting a male youth. She doused the dragon with the holy water she carried in an aspersorium (a vessel used to contain holy water) and held her cross in front of it. The dragon was appeased and allowed St. Martha to bind it with her girdle. Francesco Mochi’s St. Martha in the Barberini Chapel at Sant’Andrea della Valle, Rome (1609–1628), shows her bending down to place the aspersorium in the monster’s mouth.

Martin V’s election to the papal throne ended the Great Schism. At the Council of Constance, antipope John XXIII and Benedict XIII were deposed, Gregory XII was forced to abdicate, and Martin was elected as sole occupant of the papal throne. Martin was a Colonna, a member of one of the oldest and most powerful families in Rome. He was educated in law at the University of Perugia and appointed protonotary by Urban VI and cardinal deacon by Innocent VII. Having attained the papacy, Martin was able to reestablish its seat in Rome in 1420, through his family’s backing. He granted concessions to Queen Joanna II of Naples to effect the removal of the Neapolitan troops that occupied Rome, and to condottiere Braccione di Montone, who then dominated central Italy. Martin recognized Braccione as Lord of Perugia but then defeated him in the Battle of L’Aquila in 1424.

In Rome, Martin sought to reaffirm the power and prestige of his office and rescue the city from the disrepair into which it had fallen during the schism. To this effect, he began a reconstruction campaign of the major pilgrimage sites, including St. John Lateran, Santa Maria Maggiore, and the portico of Old St. Peter’s. He also commissioned from Masolino the altarpiece for Santa Maria Maggiore, which depicts the church’s founding (Miracle of the Snow, c. 1423; Naples, Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte), and from Gentile da Fabriano frescoes depicting the life of St. John the Baptist and prophets (now destroyed) for the walls of St. John Lateran. With this, Martin laid the foundations for the development of the Renaissance in Rome.

One of the most important pupils of Duccio, instrumental in the development of the International Style. Martini is known to have assisted his master in the execution of the Maestà Altarpiece (1308–1311; Siena, Museo dell’Opera del Duomo) and been active in Siena, Naples, Sicily, Assisi, and the papal court of Avignon in Southern France. His first documented commission is the Maestà for the Council Chamber in the Palazzo Pubblico, Siena (1311–1317; partially repainted in 1321), meant to inspire the rulers of the city who convened in this room to engage in wise government. In 1317, Martini was invited by Robert D’Anjou, king of Naples, to work for him at his court. There he painted an altarpiece of St. Louis of Toulouse (Naples, Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte), Robert’s brother, to commemorate his canonization that year and assert divine sanction of Anjou rule.

In c. 1328, Martini was in Assisi, painting frescoes in the Montefiore Chapel in the Lower Church of San Francesco. The commission came from Franciscan cardinal Gentile Partino da Montefiore, who had close ties with the House of Anjou, as he had negotiated the attainment of the Hungarian throne for Robert’s nephew, Charles I Carobert. These frescoes depict the life of St. Martin of Tours, who lived in the 4th century and to whom the Church of San Martino ai Monti, Rome, Cardinal Montefiore’s titular church, is dedicated. Among Martini’s altarpieces are the polyptych he created for the Church of Santa Caterina in Pisa (Pisa, Museo Nazionale di San Matteo), called the Pisa Polyptych (1319), and the Annunciation for the Cathedral of Siena (1333; Florence, Uffizi), this last work with the assistance of Lippo Memmi, who rendered the figures of St. Ansanus and St. Margaret on the outer leaves.

In 1335, Martini went to France to work in the papal court of Avignon, where he spent the rest of his life. There he befriended Petrarch, who was also working for the papacy. In c. 1340–1344, Martini executed the Road to Calvary (Paris, Louvre), originally part of a polyptych depicting the Passion of Christ. In the same time period, he received the commission from Cardinal Jacopo Stefaneschi to fresco the Church of Notre-Dame-des-Doms in Avignon. These frescoes included a Blessing Christ and a Madonna of Humility, which have deteriorated considerably. The sinopie for these two scenes are now housed in the Papal Palace in Avignon. As the French papal court was frequented by delegates and other individuals from various realms, Martini’s Sienese visual vocabulary soon spread to other parts of Europe, where it developed into what is aptly called the International Style.

Spanish painter and miniaturist who embraced the International Style. Martorell was probably trained by Luis Borrassá in Barcelona, where he is documented beginning in 1427. There he became the leading artist of the region. The only securely documented work by Martorell is the Altarpiece of St. Peter of Pubol (1437; Gerona, Museo de Gerona). This work, his Altarpiece of St. Vincent (c. 1435–1440; Barcelona, Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya), his Retable of St. George (c. 1437; Chicago, Art Institute; Paris, Louvre), and his Retable of the Transfiguration (c. 1445–1452; Barcelona, Cathedral) show the emphasis on the details of costumes and architecture, liberal use of gilding, and crowding characteristic of the International Style. These works also demonstrate Martorell’s gradual move toward greater realism and simplification.

Work painted by El Greco for King Philip II of Spain as the altarpiece to the Royal Church of El Escorial. The Theban Legion was composed of 6,000 Christian men from Upper Egypt from the 3rd century, led by St. Maurice. When the saint and his men refused to sacrifice to idols, as commanded by Emperor Maximian Herculius, they were decapitated. Maurice and two fellow officers encouraged their soldiers not to lose faith as they were being martyred, which is the moment depicted by El Greco in the Martyrdom of St. Maurice and the Theban Legion. In the painting, angels above hold palms of martyrdom and await the men’s souls in Heaven. El Greco deemphasized the horror of the scene by placing the executions in the middle ground and decreasing considerably the scale of the figures in that portion of the painting. Philip II rejected the work, although El Greco was paid for his services, and the painting was placed in storage in the Escorial basement. El Greco did not obtain further royal commissions; his unique style may have proved too progressive for his patron.

A follower of Christ who became one of the great examples of the repentant sinner. Mary Magdalen’s legend seems to be a conflation of various episodes from the lives of more than one woman. Prior to her acceptance of Christ, she was a prostitute. She gave up her sinful life when she and her sister Martha received the Lord in their home. While Martha was busy preparing dinner, Mary Magdalen listened to his words, which caused her renunciation of sin—the scene depicted by Diego Velázquez in his Christ in the House of Mary and Martha (c. 1620), at the National Gallery in London. In the house of Simon the Pharisee, Mary Magdalen washed Christ’s feet with her tears, dried them with her hair, and anointed them with costly oils—a prefiguration to the anointment of Christ’s body after the Crucifixion. This is the scene depicted by Dirk Bouts in Christ in the House of Simon the Pharisee of the 1440s (Berlin, Staatliche Museen).

Mary Magdalen usually weeps at the foot of the cross during the Crucifixion, as in Matthias Grünewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece (fin. 1515; Colmar, Musée d’Unterlinden). She was the first to visit Christ’s sepulcher, only to find it empty. Christ appeared to her, and, at first, she took him for a gardener. When she realized who he was, she tried to touch him, but he cautioned her against it, as he had not yet ascended to Heaven. In art, the scene is called Noli me Tangere (“Do not touch me”), and shows Christ carrying a hoe. Examples are Titian’s version of c. 1510, in the National Gallery in London, and Correggio’s of c. 1525, in the Madrid Prado.

After Christ’s death, Mary Magdalen went to Provence, in France, where she spent the rest of her life in the wilderness, engaging in penance. In art, this period in her life was also a common subject. Donatello’s Mary Magdalen, which shows her in her last years, is by far the most expressive, as he rendered the saint in polychromed wood as an emaciated, toothless figure covered by her long, red tresses (1430s–1450s; Florence, Museo dell’Opera del Duomo).

The Italian painter Masaccio was born in San Giovanni Valdarno, near Florence, where he is recorded as having joined the painters’ guild in 1422. “Masaccio” was his nickname, a derogatory appellation that referred to his uncomely physical appearance. Giorgio Vasari, in fact, wrote that Masaccio was so completely engrossed in his art that he dedicated little time to his own grooming or the tidying of his home. Little is known of his training, but it is clear that his contemporaries, Donatello and Filippo Brunelleschi, were a major force in his artistic development, as was Giotto. Like Giotto, Masaccio rejected the ornamental style of the Sienese and Venetian schools and instead opted for a more naturalistic mode of expression. From Donatello he borrowed the solidity of forms and from Brunelleschi the new classical architectural vocabulary to use in the backgrounds of his paintings. Moreover, Masaccio was the first to experiment with one-point linear perspective, a scientific method thought to have been developed by Brunelleschi.

Masaccio’s Madonna and Child with Saints (1422; Florence, Uffizi), painted for the Church of San Giovenale in Cascia di Reggello, provides an early example of his art. Here the figures occupy a believable, rational space. They are more voluminous than the figures rendered by masters from the previous century, they overlap to further enhance the sense of space, and the shading of their draperies is more emphatic than in earlier examples. Two years later, Masaccio collaborated with Masolino in the execution of the Virgin and Child with St. Anne (Florence, Uffizi), a painting that stresses Christ’s genealogy by placing the figures one behind the other to form a pyramid.

In c. 1425, Masaccio and Masolino again collaborated, this time in the Brancacci Chapel at Santa Maria del Carmine, where they painted scenes from the life of St. Peter. The following year, Masaccio rendered the Enthroned Virgin and Child, part of the Pisa Polyptych, commissioned by Giuliano di Ser Colino degli Scarsi for Santa Maria del Carmine, at one point dismantled and its pieces scattered. In 1427, Masaccio created one of his most important masterpieces, the Holy Trinity at Santa Maria Novella. Masaccio’s importance lies in the fact that he introduced new technical innovations to painting that allowed for believable renditions of space. Although he died while still in his 20s, the impact of his art was immense.

Florentine painter who trained with Giotto. Maso’s masterpiece is the series of five frescoes he created in c. 1340 for the Bardi di Vernio Chapel at Santa Croce, Florence. These scenes are from the life of St. Sylvester, who reigned as pope in 314–335 and who persuaded Emperor Constantine the Great to convert to Christianity. The monumentality of Maso’s figures in these frescoes; the volume of their faces, hands, and drapery folds; and the diagonal placement of the background architecture to show two sides at once are elements he borrowed from his master. The elaborate backdrops, refined costumes and figure types, meticulous rendering of details, and careful application of paint, however, are very much his own.

Masolino has been overshadowed by Masaccio, with whom he often collaborated. Studies on his art unfortunately have centered mainly on identifying his intervention in these commissions he shared. One of his early works is the Miracle of the Snow (c. 1423; Naples, Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte), part of the Santa Maria Maggiore Triptych commissioned by Pope Martin V for the Church in Rome bearing the same appellation. In c. 1425, Masolino worked with Masaccio on the frescoes of the Brancacci Chapel at Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence, commissioned by Felice Brancacci. Among the scenes he contributed are the Healing of the Lame Man and the Raising of Tabitha and the Temptation. The scenes on the vault and lunettes, destroyed in the 18th century, are also thought to have been by his hand.

In c. 1428–1430, Masolino was again in Rome, painting frescoes from the life of St. Catherine of Alexandria in the Castiglione Chapel at San Clemente for Cardinal Branda Castiglione. This commission is one of the best examples of the period of propagandist chapel decoration. Masolino’s works show that he adopted techniques he learned while working alongside Masaccio, including one-point linear perspective, a single source of light, and cast shadows that enhance the three-dimensionality of forms. Masolino’s art is distinguished from Masaccio’s, however, in that his figures are more elegant and slender, yet lack the visual impact and emotive power of those rendered by his fellow master.

When the three magi set off to find the newborn Christ, they asked Herod, king of Judea, if he knew where the child could be found. Upon hearing of the birth of the new king of the Jews, Herod felt his position threatened and ordered the killing of all the children in his kingdom aged two or younger. The story gave artists the occasion to paint a complex scene of violence and desperation that highlighted their artistic abilities. Among the most poignant examples are Giotto’s in the Arena Chapel in Padua (1305), Domenico del Ghirlandaio’s in the Cappella Maggiore at Santa Maria Novella, Florence (1485–1490), Guido Reni’s in the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Bologna (1611), and Peter Paul Rubens’s in the National Gallery in London (1611–1612).

Flemish master, now identified as Robert Campin from Tournai. Campin was the teacher of Rogier van der Weyden and, along with Jan van Eyck, is considered the father of Early Netherlandish art. The name Master of Flémalle derives from three panels, now in the Städelsches Kunstinstitut in Frankfurt, which came from an abbey in Flémalle, near Liège. Campin was born in Valenciennes, possibly in 1375, and became a citizen of Tournai in 1410. In 1423, he was elected dean of the painter’s guild and served on one of the city’s councils until 1428. In 1432, he was banished from Tournai for immoral conduct and forced to go on pilgrimage to St. Gilles in Provence. The sentence was reduced to payment of a fine, thanks to the intervention of Jacqueline of Bavaria, daughter of Count William IV of Holland, which reflects the esteem with which Campin was regarded.

Scholars usually place the Entombment Triptych (c. 1415–1420; London, Collection of Count Antoine Seilern) among Campin’s earliest works. It presents everyday figure types engaged in the drama of the moment, the angularity of their draperies offering an alternative to the fluid rhythms of the works of contemporaries. The shallow background and compression of the figures into a tight space suggest that Campin looked to sculpted religious imagery, for which Tournai was well known, while the weeping angels and heads of the Virgin and the dead Christ pressed together suggest an awareness of the works of Giotto, the one to introduce these motifs into art.

Campin’s Nativity (c. 1420; Dijon, Musée des Beaux-Arts) develops further the naturalistic tendencies of the Entombment. Here, a road leads into a landscape, the recession into space convincingly achieved by empirically observing nature and imitating it on the panel. The work is full of symbolism, typical of Campin’s art. St. Joseph, for instance, shields the flame of a candle with his right hand to denote, as the Bible instructs, that Christ is the light, a point reiterated by the rising sun behind the manger. Moreover, the midwife with the withered hand refers to the apocryphal account of the Nativity, where one of the midwives who attended Mary during childbirth doubted Christ’s virgin birth—her irreverence resulting in the problem with her hand, which was cured by the touch of the Christ Child.

Campin’s most celebrated painting is the Mérode Altarpiece (c. 1426; New York, Cloisters). The central panel in this work shows the Annunciation in an interior domestic setting, with the Virgin seated on the ground to denote her humility. A miniaturized Christ Child carrying the cross enters the room through a window and flies toward his mother’s womb, marked by the star pattern formed by the folds of her drapery. The fact that the child has passed through the glass without breaking it refers to his mother’s virginity being preserved regardless of conception. The background niche represents the tabernacle in the temple and the towel the washing of the hands by the priest before the mass. The smoke rising from the extinguished candle confirms the presence of God in the room, while the scroll and book on the table refer to the Old Testament and New Testament, respectively, and the vase with lilies to the Virgin’s purity. On the left wing of the altarpiece are the donors, identified as members of the Ingelbrecht and Calcum families by the coat of arms on the back window in the central panel. On the right wing is St. Joseph in his carpentry shop, working on a mousetrap, an allusion to St. Augustine’s statement that the Incarnation of Christ was the trap used by God to ensnare the devil.

Campin followed his famed altarpiece with the Virgin and Child before a Fire Screen (c. 1428; London, National Gallery; some believe the work to be by a follower of Campin) and the Virgin in Glory (c. 1428–1430; Aix-en-Provence, Musée Granet). In the first, the fire screen behind the nursing Mary forms a halo around her head. The second presents Mary and the Christ Child seated on a bench, a crescent moon at their feet, and floating above St. Peter, St. Augustine, and a donor—a scene based on the account of the Apocalypse. Both paintings show a more successful recession into space and greater unity among the compositional elements than in Campin’s earlier works.

Campin used oil as his medium, which allowed him to apply layer upon layer of color and resulted in a brilliance never before seen in panel art. He was also the first master in the North to reject the elegant, courtly scenes of the International Style in favor of the representation of the natural world and the drama of human existence. Although heavily dependent on the Northern miniaturist tradition and the sculpture of Tournai, Campin was the pioneer who established the visual conventions that would reign in the North until the end of the 15th century.

One of the Evangelists who authored the Gospels and the patron saint of bankers, as he was a tax collector from Capernaum when Christ called him to become one of his Apostles. After Christ’s Crucifixion, Matthew went to Judea, where he preached, and then to Ethiopia, where he was martyred by sword for thwarting the king’s attainment of the virgin Ephigenia. Matthew’s story was masterfully illustrated by Caravaggio in the Contarelli Chapel, Rome (1599–1600, 1602), including his calling by Christ, his writing of the Gospel while guided by an angel, and his martyrdom. Hendrick Terbrugghen also painted the Calling of St. Matthew in 1621 (Utrecht, Centraal Museum), and Nicolas Poussin rendered the Landscape with St. Matthew in 1640 (Berlin, Gemäldegalerie), where the angel dictates to the saint the word of God.

Born in Wiener Neustadt into the Hapsburg line, the son of Frederick III and Eleonora of Portugal. Maximilian’s marriage to Mary of Burgundy (d. 1482), daughter of Charles the Bold, in 1477 led to his obtaining the Burgundian Netherlands and his involvement in war against France concerning the territory. Maximilian also became involved in the Italian Wars, carried out by the great European powers to control the Italian independent cities, his purpose being to prevent French territorial expansion and extend the Hapsburg dominion. His association with Ludovico “il Moro” Sforza during this conflict led to his marriage in 1493 to Bianca Maria Sforza, Ludovico’s niece. At the time, he invested Ludovico with the Duchy of Milan, to which Louis XII of France also laid claim. In 1508, he allied himself with Pope Julius II and France, forming the League of Cambrai to curtail Venice’s territorial expansion. In 1511, however, Maximilian and the pope formed the Holy League to expel Louis XII from Italy.

Maximilian was the patron of Hans Burgkmair, who created a series of woodcuts for him, and Albrecht Dürer, whose portrait in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna (1519) records the emperor’s likeness. Maximilian is also included in Dürer’s Rozenkranz Madonna (1505–1506; Prague; National Gallery) for the Church of San Bartolomeo, commissioned by the Fondaco dei Tedeschi, the association of German merchants in Venice. There he kneels to be crowned with roses by the Virgin. Juan de Flandes worked for Maximilian as well. The emperor sent him to the Spanish court to render the likenesses of the royal children.

German engraver from Bocholt who was trained by his father, also an engraver and a goldsmith. Sixteen early prints by Meckenem are in fact copies of his father’s works. Meckenem is documented in Cleves in 1465, and in Bamberg in 1470, returning to Bocholt in 1480, where he was elected to the town council in 1503. A prolific engraver, he left more than 600 plates, many of which provide insight into everyday life and lore. Among these are the Morris Dance (c. 1475), a form of comical acrobatic dance performed during carnival; The Lute Player and the Harpist (c. 1490), which has left a visual record of the musical instruments and costumes of the day; and The Visit to the Spinner (c. 1495), which presents a middle-class interior domestic setting. Meckenem’s Self-Portrait with His Wife Ida (c. 1490) is among the earliest self-portraits in an engraving to have survived. Meckenem’s style is characterized by sharp contrasts of light and dark, emphasis on textures, and sharp contours that add visual richness to his images.

In 1615, Marie de’ Medici, wife of Henry IV of France, commissioned Salomon de Brosse to build for her the Luxembourg Palace in Paris, based on the Palazzo Pitti, the residence in Florence where she had lived as a child. Once completed, Marie took the task of decorating it. She commissioned Peter Paul Rubens to create a cycle of more than 40 works to commemorate her and her husband’s deeds, to be placed in the palace’s two galleries. Rubens had already worked for her son, Louis XIII, in 1620–1621, creating cartoons for 12 tapestries, depicting the life of Emperor Constantine the Great. Familiar with the master’s talent, Marie felt confident that he would provide works of great quality for her as well.

Only approximately 20 paintings were completed by Rubens, all from the life of Marie. The cycle begins with her childhood and education, and continues with her arrival in Marseilles, her marriage to Henry, his assassination in 1610, her regency and exile to Blois, and her reconciliation with her son and vindication. The cycle glorifies a life that was not as exalted as Marie professed. The misery of her childhood had to do with her mother’s early death and her father’s remarriage to a commoner. He sent his children, including Marie, away to the Palazzo Pitti. Two of them died in childhood and a third was married off at an early age to the Duke of Mantua, leaving Marie on her own. Henry IV only married her for her hefty dowry.

In 1610, Henry IV was stabbed to death, and Marie became regent to her son because Salic Law prohibited women from serving as queens. Her relationship with her son was froth with conflict, and although they reconciled after Louis exiled her to Blois, thanks to the intervention of Cardinal Armand Richelieu, in 1630 he exiled her for good. She escaped to the Low Countries and then Germany, where she died. Luxembourg Palace was closed and Rubens’s cycle forgotten until the late 17th century, when it was reopened. The rediscovery of Rubens’s Medici Cycle, with its lush brushwork and rich colorism, caused a major sensation. Debates among Poussinists and Rubenistes ensued, forever changing the course of art in France.

The Medici originated in the valley of the Mugello and moved to nearby Florence in the 13th century. In 1397, Giovanni di Bicci de’ Medici established a bank. Soon he opened branches throughout Italy and Europe, and became involved in papal finances, enterprises that resulted in his amassing a large fortune. With wealth came power, and in 1402, Giovanni was elected to serve as one of the priors of Florence’s legislative body, the Signoria. His son Cosimo sealed the family’s political hegemony when, in 1434, he was able to effect the removal of the Albizzi from power and take over their position as the city’s leading political figure. Medici rule was to last until the 18th century, when the family died out, save for exile in 1494 and again in 1527. In 1530, the Medici took absolute control of Tuscany as dukes and, in 1569, grand dukes, titles they obtained through the efforts of two Medici popes: Leo X and Clement VII. Marriage alliances linked them to the royal houses of France and Spain, further strengthening their position of power.

It is not unreasonable to say that the Medici were one of the central forces that enabled the Renaissance to take place, as they contributed greatly to the cultural and intellectual fabric of Florence, the birthplace of the movement. Without their patronage, philosophers Marsilio Ficino and Pico della Mirandola; artists Donatello, Filippo Brunelleschi, Sandro Botticelli, and Michelangelo; poet Angelo Poliziano; and astronomer Galileo Galilei might not have had the opportunity to achieve the endeavors for which they are so well known.

The son of Giovanni di Bicci de’ Medici. Cosimo was exiled from Florence by the Albizzi, who headed the city’s oligarchic regime, for leading an opposing political faction. That faction was powerful enough to have Cosimo recalled in 1434 and the Albizzi removed from power. Cosimo became the leader of a republican system he quietly governed from behind the scenes. To ensure his hegemony, he banished his opponents and appointed magistrates from among his supporters. He also forged alliances with Milan, Naples, Rome, and Venice.

Cosimo’s court is considered to have been key to the development of the Renaissance, as he supported such scholars as Argyropoulous and Marsilio Ficino, who opened the Platonic Academy in Florence with his backing. In addition, he was the patron of Donatello and Michelozzo, who designed his Palazzo Medici (beg. 1436). Cosimo also affected the Florentine religious fabric, as he was a major supporter of the Dominicans. He gave them the San Marco Monastery in Florence after expelling the Sylvestrine monks, who had occupied the building and allowed it to fall into disrepair. Cosimo had Michelozzo renovate the structure and add a library, the first to be built in the Renaissance. Once completed, he donated 400 Latin and Greek manuscripts as the core of its collection, establishing San Marco as one of the most important public libraries of Europe. From 1438–1445, he also financed the frescoes Fra Angelico painted in the monastery’s cells.

The grandson of Cosimo de’ Medici. Lorenzo was 20 years old when he took control of the government in Florence from his invalid father, Piero the Gouty. Like his predecessors, he chose to control the city from behind the scenes. He also continued the policy of forging alliances with the major Italian city-states and contributing to the cultural and intellectual life of Florence. In 1478, Lorenzo fell victim to the Pazzi Conspiracy to oust the Medici from power. On that occasion, he was wounded and his brother Giuliano murdered, an act for which he retaliated by hunting down and severely punishing the conspirators.

Lorenzo was the patron of poet Angelo Poliziano. Under him, Marsilio Ficino translated the works of Plotinus and Proclus, bringing Neoplatonism to the forefront of philosophy. It was Lorenzo who took the young Michelangelo under his protective wing and nurtured his talent and persona, and who commissioned Andrea del Verrocchio to create his famed bronze David (1470s; Florence, Museo Nazionale del Bargello). Giuliano da Sangallo built for him a magnificent villa at Poggio a Caiano (1480s), the first attempt to recreate an ancient suburban villa based on the descriptions provided by Vitruvius and Pliny the Younger. Sangallo also built the Church of Santa Maria delle Carceri at Prato (1484–1492) with funds provided by Lorenzo.

The daughter of Grand Duke Francesco I de’ Medici of Florence and Johanna of Austria, daughter of the Hapsburg Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand I. In 1600, she was betrothed to Henry IV of France, whose poor finances necessitated a lucrative marriage alliance, which the Medici were willing to provide. The following year, she gave birth to her son, the future Louis XIII. Her mother’s untimely death and her father’s remarriage and almost complete abandonment of his children had caused great misery in Marie’s early life. Her marriage did not fare any better. Henry had a number of mistresses, who resented her presence at court. When he was assassinated by a religious fanatic in 1610, Marie was immediately appointed regent to her son, as Salic Law prevented her from assuming the role of queen. No sooner had she obtained this charge than she banished Henry’s mistresses.

As regent, Marie fell under the influence of Concino Concini, marquis of Ancre, who dismissed Henry’s minister, Duc de Sully, and created such resentment that the nobility rebelled against the regency. In 1617, Concini was assassinated. Having attained his majority, Louis XIII assumed his position as king of France and exiled his mother to Blois. In 1619, she escaped and allied herself with her younger son, Gaston d’Orleans, against the king, only to be defeated. In 1622, Cardinal Armand Richelieu, Louis’ first minister, reconciled Marie with the king. The reconciliation, however, did not last. A conspiracy to overthrow Richelieu for his anti-Hapsburg policies caused Marie’s permanent banishment from the French court. She escaped to the Low Countries and then Germany, where she spent the last years of her life.

Peter Paul Rubens created for Marie from 1622 to 1625 the Medici Cycle for the Luxembourg Palace, built for her by Salomon de Brosse (beg. 1615), to record the most important events of her life and glorify her position as the wife of Henry and mother of Louis. Another artist patronized by Marie was Orazio Gentileschi, who was present at her court in 1624.

German sculptor who, from 1506 to 1510, worked in the court of Frederick the Wise, Elector of Saxony, in Wittenberg. In 1514, Meit entered in the service of Margaret of Austria, creating for her large- and small-scale statues and overseeing the execution of her tomb, as well as that of her husband, Philibert II, Duke of Savoy, in the Church of Brou, Bourg-en-Bresse (1526–1532). Meit is thought to have been trained by Lucas Cranach the Elder, who worked alongside him and Albrecht Dürer in Frederick’s court. Meit is best known for his small-scale freestanding sensuous nude figures inspired by Italian and ancient prototypes. Among them are his Judith with the Head of Holofernes (1510–1515; Munich, Bayerisches Nationalmuseum), Lucretia (c. 1510; Braunschweig, Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum), Mars and Venus (1520; Nuremberg, Germanisches Nationalmuseum), and Eve (c. 1520; Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum).