18.

The Neutron Bomb

Neutron weapons always exuded an eerie fascination. In 1960, when specialists in the U.S. military considered them only a theoretical concept, Senator Thomas Dodd of Connecticut alluded in a talk on the future of war to the possibility of adjusting the energy of an atomic explosion so that “instead of heat and blast its primary product is a burst of neutrons.” This burst of neutrons, the senator said, would do negligible physical damage, but it would immediately kill all life in the target area; as The New York Times put it, such a weapon “would, in short, operate as a kind of death ray.” The U.S. Army developed the new device to better deter Soviet armored divisions—it was less contaminating and caused less collateral damage than tactical nuclear weapons. The Soviet Union immediately opposed the neutron bomb.1

In early July 1977, news broke that the United States had successfully detonated the weapon. “Neutron Bomb Tested!” screamed the front page of the Los Angeles Times. Protesters immediately mobilized; a small group of determined activists even collected their own blood in vials, which they flung against the stone pillars framing the river entrance to the Department of Defense.2 With blood dripping from the Pentagon, the Soviet Union’s covert action infrastructure began to mobilize as well. Its operational objective was threefold: to prevent the NATO-wide deployment of what the U.S. military called “enhanced radiation weapons”; to divide NATO by pitching European allies against the United States; and to distract from the Soviets’ own simultaneous military expansion.

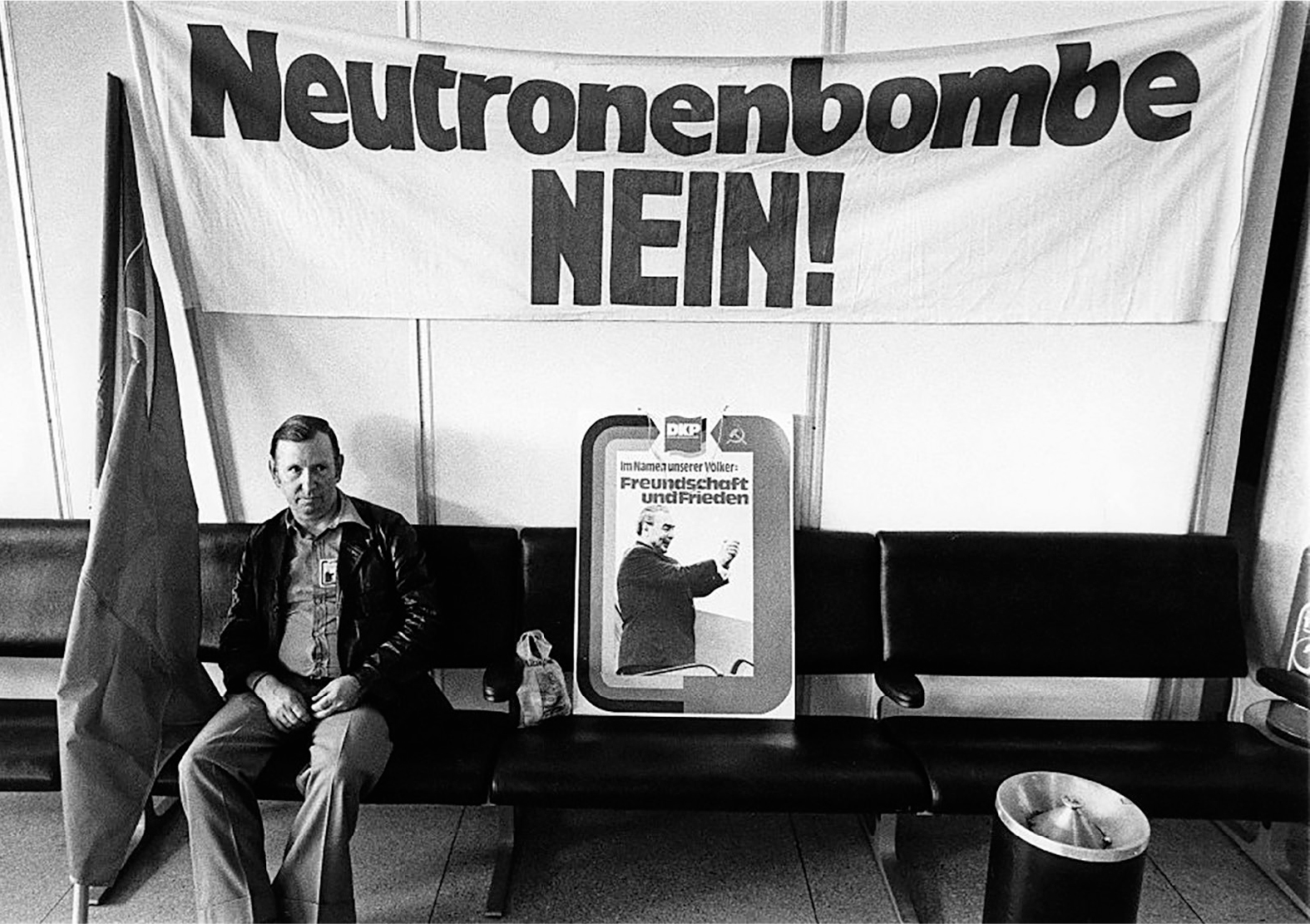

A sign reading “Neutron Bomb NO” at the Cologne airport, awaiting Leonid Brezhnev’s 1978 visit. The anti-neutron-bomb campaign was one of the Cold War’s best-funded and most successful active measures. (Photograph by Steche / ullstein bild via Getty Images)

Over the next two weeks, in July 1977, the Soviet Union ramped up the number of press stories on the neutron bomb issue. The CIA monitored more than 3,000 broadcast items weekly. Ten days after the first test, 5 percent of all Soviet bloc news stories were covering the neutron bomb. A week later the level rose to 13 percent, more than any other topic. On August 1, 1977, the official Soviet news agency announced an International Week of Action Against the Neutron Bomb.3 One commentator in Izvestia called the new technology “inhuman.” The Patriarch of the Russian Orthodox Church called the weapon “satanic.” Indeed, viewed from a Communist perspective, the neutron bomb was the ultimate capitalist weapon: a destroyer of people, not property. The Soviets understood that such an anti-capitalist critique would be even more powerful when it came from blue-collar factory workers. “I will never forget the stern privations that fell to the lot of our people during World War II,” a worker from the Motor Repair Factory No. 1 was quoted in Vechernyaya Moskva, an evening paper: “Fascist Germany wanted then to wipe off the face of the earth Moscow, Leningrad, Kiev, and other Soviet cities and villages and to turn all of us into obedient slaves. The American imperialists have gone even further, blasphemously declaring that the neutron bomb will only kill people, leaving all material structures intact.”4

Two days earlier another paper attributed a nearly identical quote to a worker in Uzbekistan, 1,500 miles south of Moscow.

In mid-July, Der Spiegel ran a cover story titled “Neutronen-Bombe, America’s Wonder-Weapon for Europe.” The magazine argued that the new radiation weapon would lower the threshold for nuclear use, and thus render more probable an all-out nuclear war that would rage across Germany. Europeans were genuinely concerned about the weapon, and the Soviets worked hard to fan the flames. Various front groups were mobilized for the cause. Peace councils organized protest meetings in a number of Eastern bloc countries in Europe, and the official newspapers of various European Communist parties published anti-neutron-bomb commentaries.5

“What had begun as a manifestly Soviet effort now appeared to many as a general public reaction to the alleged horrors of the ‘neutron bomb,’” the CIA concluded a year later.6

The Carter administration announced in September 1977 that the president would not approve production of so-called enhanced radiation weapons unless America’s NATO allies in Europe agreed to deploy them as well. The announcement provided an opening for the Soviets: public opinion in Europe could now shape a U.S. military policy—and active measures, in turn, could shape public opinion in Europe. The anti-neutron-bomb campaign shifted from the United States to Europe. Leonid Brezhnev, Khrushchev’s successor and the fifth leader of the USSR, mailed a letter to every Western European head of state, warning them that a NATO deployment of the neutron bomb would threaten détente. These announcements, as the CIA observed, received heavy media coverage worldwide.7

The United Nations’ first Special Session on Disarmament was held in New York from May 23 to June 28, 1978. The Soviets softened the ground ahead of the summit with a barrage of apparently grassroots peace movement events. By early February, the World Peace Council, through a “sub-front,” as the CIA later determined, organized a symposium in Vienna in collaboration with the International Atomic Energy Agency, an official UN body, and put the neutron bomb on the agenda. Twenty-two different country delegations attended. The main event, however, was held in Amsterdam, beginning on March 18, and was organized mainly by the Dutch Communist Party. The Dutch minister of defense, a Christian Democrat named Roelof Kruisinga, had just resigned in protest against his government’s refusal to condemn the weapon, triggering a vote in Parliament against deploying the new weapon, ten days ahead of the rally.8 The condemnation passed with more than a two-thirds majority, making it politically impossible for The Hague to agree to NATO deployment.9 More than forty thousand peace activists from all over Europe took to the streets in the mass rally called the International Forum Against the Neutron Bomb. Among the many speakers at the rally were the American critic Daniel Ellsberg, of Pentagon Papers fame; the Patriarch of the Russian Orthodox Church; and the World Peace Council’s Romesh Chandra.10 Every tenth house in Amsterdam and other cities displayed a Dutch Communist Party–issued poster reading “Stop the Neutron Bomb.”

President Carter’s doubts grew as a result.11 He was aware of the events in the Netherlands, and on the day of the Amsterdam rally he told his closest advisors that he would oppose the neutron bomb. When NATO officials indicated that the KGB could be a force behind the international anti-neutron-bomb movement, many were skeptical. “There is no evidence” of KGB influence, commented The Guardian a few weeks after the Dutch vote, as uncertainty about the future of the enhanced radiation weapon lingered.12 In early April, the news broke that Carter had postponed production of the neutron bomb, alienating some European allies, Germany among them.

M110 203mm self-propelled Howitzers are staged in a parking area at the port of Antwerp, September 1984. The M110 was capable of firing the W79 Mod 0 shell, a tactical nuclear artillery projectile with an enhanced radiation mode (a “neutron bomb”) that could be switched on or off.

(Bram de Jong / Dirk Van Laer / U.S. Department of Defense)

The active measures campaign, however, did not end. The covert campaign had been flanked by forgeries along the way. On June 8, 1978, for example, several Belgian newspapers received an anonymous piece of mail that contained a photocopy of a letter from Secretary General Joseph Luns of NATO, purportedly to the U.S. permanent representative to NATO, William Tapley Bennett, Jr. In the letter, Luns informed Bennett that “with the help of [his] friends” in Belgium’s defense ministry, “the listing of the journalists showing negative attitude to the neutron bomb” was well under way. Luns implied, ominously and without specifics, that some of his Belgian friends were “overzealous” about taking action against the listed journalists.13

When some of the named journalists reached out to NATO, the authorities immediately and publicly stated that the missive was a forgery. Almost two months later, though, the Belgian publications De Nieuwe and De Volkskrant published articles on the Luns letter, along with the fake documentation, both without any mention that the missive had been officially labeled a forgery.14

The CIA agreed with Soviet diplomats and spymasters that the neutron bomb active measures campaign had been an extraordinary success. Anatoly Dobrynin, the longtime Soviet ambassador in Washington, later recalled in his memoirs that “the Soviet campaign had undercut American plans to deploy in Europe a new kind of nuclear weapon.” The partly covert campaign, Dobrynin wrote, had successfully redefined a defensive weapon as an offensive one.15 “That the campaign was successful was confirmed when the Americans finally abandoned their idea,” concluded the KGB defector Ilya Dzhirkvelov, adding, “I can state with confidence that we received considerable help in achieving our aim from the foreign correspondents whom we supplied with disinformation.”16 In September 1979, the chief of the International Department of Hungary’s Communist Party, János Berecz, wrote, “The political campaign against the neutron bomb was one of the most significant and successful since World War II.”17 The Soviet Union awarded an official decoration to its ambassador to The Hague, recognizing his success in advancing the anti-neutron-bomb campaign through the Dutch Communist Party.

The U.S. intelligence community calculated in 1980 that an operation of the magnitude of the “neutron bomb” campaign “would cost over $100 million,” if the U.S. government were to undertake it.18 Levchenko, who defected from the KGB in 1979, as the neutron bomb campaign was ongoing, estimated the price tag at $200 million (equivalent to more than $600 million in 2018).19

U.S. intelligence was likely more reliable in its overall assessment of the effectiveness of a Russian campaign than were the Russian intelligence officers, because the CIA did not have to justify spending hundreds of millions on the active measure. CIA analysts pointed out that accurately measuring the impact of the campaign was difficult, if not impossible, for the Soviets as much as for the Americans, one reason for which was that most voters and activists in Europe genuinely did oppose the mysterious weapon. A significant amount of the opposition was entirely unrelated to Soviet active measures. Yet CIA analysts conceded that “the Soviets made ‘neutron bomb’ a household scareword in Europe, if not throughout the world.”20

Congress took note of all of these events. Prompted by new anti-American forgeries such as FM30-31B as well as the neutron bomb campaign, the U.S. House Intelligence Committee held several open hearings that would give an opportunity for the CIA to present details of Soviet active measures to the American public, and to refocus America’s attention on disinformation. The CIA’s point man for the hearing was John McMahon, the deputy director for operations. McMahon, a burly man with white hair and drooping glasses, brought with him five additional intelligence officers and a wealth of detail. During the hearing, McMahon engaged in a revealing argument about the nature of front organizations with John Ashbrook, a hawkish Republican from Ohio.

“You identified the World Peace Council as the largest of the major Soviet front groups used in propaganda campaigns,” said Ashbrook. “Is that correct?”

“Yes,” said McMahon.

The World Peace Council was founded in Paris as the World Committee of Partisans for Peace in 1949, the same year the CIA started working the Kampfgruppe in Berlin. In 1951, the French government expelled the organization for alleged fifth column activities. The council then moved to Vienna, but after three years, Austria also banned the group for “activities directed against the Austrian state.” The U.S. State Department later described the World Peace Council as an “archetypical front organization.”21 (Soviet diplomats agreed with this assessment. Arkady Shevchenko, the Soviet Union’s undersecretary general of the United Nations, witnessed the council’s work in New York during the neutron bomb campaign: “Particularly annoying were the ceaseless requests from Moscow to assist the Soviet-controlled World Peace Council,” Shevchenko recalled, adding that the nominal peace organization “swarmed with KGB officers.”)22

Ashbrook was aware of some of the World Peace Council activity, and continued his questioning of McMahon. “All right,” he said. “Does it or does it not have an American affiliate?”

“It has an American affiliate,” the CIA officer responded.

Ashbrook grew impatient: “The American affiliate is the U.S. Peace Council, is it not?”

“Right,” said one of McMahon’s staffers.

“The American affiliate of the World Peace Council, the U.S. Peace Council, had their founding convention just last fall. It was November 9 to 11 in Philadelphia,” Ashbrook said, turning to the CIA’s McMahon. “Do you target that?”23

McMahon was confused.

“We would not target it,” he said about the U.S. front organization, “nor would we follow it.” The CIA’s McMahon pointed out that the Peace Council would be the FBI’s responsibility, and then added, tersely, “I must point out that the Communist Party is a very legal institution in the United States.”

Ashbrook expressed his frustration with letting a known Soviet front group go on its merry way. “I guess that is just a part of the problem we have in the West,” he said.

“That is part of an open society, sir,” responded McMahon.

The CIA’s Directorate of Operations had understood perhaps one of the most insidious threats posed by successful disinformation campaigns: overreacting to active measures risked turning an open society into a more closed one. The more difficult question was how to draw the line between reactions that defended the former and those that encouraged the latter. Only the future would tell.