10

COMMAND AND COLLABORATE

It seemed like much more was going wrong than right. Snow and ice had been cascading off the roof since Friday, flattening the massive clear-span tents that were installed to serve as sheltered extensions to the stadium that contained additional rest rooms, concession counters, and merchandise kiosks. Instead, they had become a hazardous no-man’s-land, filled with mangled, misshapen steel beams, acres of tattered nylon, and scattered debris of destroyed furniture, fixtures, and equipment. None of the entrances to the stadium behind the wreckage were usable, and the area was still too dangerous to clear any of the damage before the fans were scheduled to arrive. Temporary grandstands inside the stadium were still being installed and the push to complete them before admitting the public necessitated a delay in opening the gates.

This description is of the North Texas Super Bowl XLV in 2011, discussed earlier, during which thousands of fans were stranded in massive queues on the wrong side of the building, and it seemed as though one intractable problem piled up on the last one all day long. Our operations team huddled early at NFL Control. Reminiscent of NASA’s Mission Control Center, team members responsible for every facet of the operation sat at long rows of tables, chairs, and equipment, looking through enormous glass windows at the field instead of video feeds from outer space.

It seemed very natural to have everyone at NFL Control facing the field, since the seats in the stadium generally faced in the same direction. As more and more things went wrong that day, however, it proved to be an extremely inefficient configuration for working as a team to respond to problems. Strategically sandwiched between the lead teammates responsible for security and broadcasting operations, I sat in the front row of NFL Control monitoring multiple radio channels. But I was largely unable to communicate with others in the command center without radioing, phoning, or texting them. That day, a great deal of coordinated effort was required to manage all that failed, and many of us spent hours standing, turning, and shouting across the stair-stepped rows stretching the width of the room. It was apparent very quickly that this was a great arrangement for everyone to be able to see the game while things were going well, but far from the best configuration for a command center requiring collaborative problem solving when things were not going well.

Just a few years before, I visited the Pagoda Tower at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway (IMS) to see how they managed race day at the Indy 500. Given the vast footprint of the 2½-mile oval track, there is no spot where anyone could see everything, and the command center was no exception. From Race Control, all team members who had a need to see the action were seated at the windows overlooking the “Yard of Bricks,” the 36-inch strip that comprises the start and finish line, dating to when the entire Speedway track was paved with bricks in 1909. Stretching out in front of the team members was a bank of TV monitors displaying images covering every square foot of the oval track. Each teammate was on the lookout for crashes, car parts, and dangerous debris in their assigned section of the track. The race director stood at the corner windows watching the front stretch; beside him was a large TV screen displaying a swirling cascade of Global Positioning System (GPS) coordinates, representing each car on the track.

As cool as the technology was, what impressed me the most was on the other side of the elevator bank: the large rectangular conference table located with no view of the race at all, which was decidedly low-tech. Seated around the table were the IMS team members with responsibilities that did not require a view of the track—security, transportation, facility operations, and more. As the Speedway filled with fans, this group worked swiftly and efficiently together to manage operations, share updates with one another, and solve problems collaboratively, all because they were seated around a rectangular conference table looking and talking with each other, rather than facing forward in a classroom-style configuration.

It took the woefully inefficient and frustratingly ineffective experience of trying to manage multiple problems at Super Bowl XLV, in 2011, for us to consider redesigning NFL Control. For Super Bowl XLVI, held in Indianapolis in 2012, we applied the intelligence gathered during our visit to the Indy 500’s Race Control facility. We positioned the people who needed to see the field to best do their job—officiating, football operations, broadcasting, and media relations—facing the window. Right behind them, we installed a large rectangular conference table, where representatives of each area not directly related to the activities on the field—stadium operations, transportation, medical services, and social media monitors—could keep each other updated and work collaboratively to solve problems. For several of us facing the field—including myself, the head of security, and public safety officials—we could easily swivel our chairs around to face the conference table should our input be required. Although we installed additional TV monitors, game clocks, and time-of-day clocks for those seated at the conference table to keep tabs on the game, I’m sure it was a highly unpopular decision to take people away from their view of the field. But, we all understood that we were there to do our jobs to deliver the best outcome, and without question, this proved to be a better way to do it.

YOUR COMMAND CENTER

Setting up a single location where key constituents and stakeholders can gather and work together as a project rolls out—your own “NFL Control”—is a smart move and one that can significantly improve timely, informed decision making when something goes wrong. You don’t have to be managing a major event for this to make sense. You may be preparing for a potential threat, such as a negative news story, a court decision, or a labor dispute.

We set up such a workspace as a deadline approached threatening the NHL with its first strike in 1992. Our “crisis communications center” was filled with banks of phones and TV monitors, enabling representatives of all league business units to stay consistently on-message and equipped with the most up-to-the-minute information. With details rapidly unfolding, information could be quickly, accurately, and simultaneously disseminated across the business. So, too, we could collect and compare market sentiment from our most important customers, clients, and the press, and then elevate consistent themes to the highest levels of management.

We called it the “crisis communications center” because we were truly facing significant brand and economic risk. But you don’t need to be facing an existential crisis to establish a central location from which to monitor and manage a new project. A temporary installation—where the project leader and representatives from all relevant support areas are housed—is as good an idea for gathering results and reactions from the marketplace as it is for the quickest coordinated response to when things go wrong. It is also the singular place where senior management can get a comprehensive real-time snapshot of a project’s performance.

Forces operating outside of our organizations can often impact results and cause us to make midcourse corrections to our plans. In addition to installing televisions showing broadcast coverage of the Super Bowl, NFL Control monitored news feeds so we could be instantly apprised of any news or business developments that might require us to make adjustments or last-minute decisions. Do the same in your project office, keeping a close watch on news and other feeds most relevant to your company or industry. Our digital media team combed through social media platforms to inform us of conversation trends, observations, and complaints so we could respond to emerging issues. Your project control center might also benefit from dashboards displaying essential real-time performance metrics such as orders, sales, social media sentiment, stock prices, and news streams.

Every company or project office can have a designated location—a room equipped with phones, teleconferencing equipment, computers, and other communications gear, white boards, and office supplies—where problem solvers know to get together when a crisis or challenge unfolds. Identifying a command center can be as simple as designating a company conference room that can be quickly activated when something unexpectedly goes wrong. There should also be a predesignated rallying alert to send word out that an emergency meeting or a coordinated response is needed. With just a little advance planning and at a manageable cost, getting the word out quickly to gather is easy.

We subscribed to an emergency texting system with which we could manage an infinitely subdividable database of text numbers and e-mail addresses. If something that went wrong required instant communication with everyone, say a last-minute cancellation or an evacuation, we could instantly and simultaneously reach out to our full database of teammates working with us at the Super Bowl. We also divided the database into functional subgroups to whom we could communicate messages tailored for more specific audiences—the executive management team, department heads, the operations team, the security department, the event operations group, and many others.

The database management-and-communications system was used to keep specific segments of the staff informed with the latest operational information, such as travel times and waiting times at gates. Thankfully, we rarely had to issue a communication to the widest, all-points audience, but if our off-site staff parking or check-in facilities were inaccessible due to, say, a fire in the area or a road closure, we would have been able to reach thousands of team members with a single text message command. This system would have given us the ability to instantly contact and quickly gather the most appropriate group decision makers for coordinated responses to critical problems.

Having a method to rapidly communicate with your entire team, or with selective subgroups of key department, project, and contractor staff, can save valuable time mobilizing responses. Many organizations use e-mail distribution lists for this purpose, but I’ve found that brief texts tend to cut through the clutter and are reviewed by recipients with more urgency. It just takes a little advance planning and thoughtfulness to set up the most likely subgroups you or your organization will need to contact in a hurry. Having a predetermined place where project leaders can collect senior decision makers and gather additional teammates for assistance can also greatly reduce response time when minutes count.

On Super Bowl Sunday, the place to gather was NFL Control. But, because fans and the media could look in through the big windows facing the field just as easily as we could look out, we designated a smaller, secondary room nearby with no windows, just in case an issue was so serious or sensitive that it required the Commissioner or other publicly recognizable figures to meet with us to be briefed, provide direction, or issue decisions in the midst of a crisis. Bud Selig, apparently, did not have easy access to such a place in 2002 when his 11th-inning All-Star Game briefing was conducted in front of millions of TV viewers.

THE WEB OF COMMAND

On July 21, 1944, American forces stormed the island of Guam in the western Pacific, launching a costly, weeks-long struggle to retake territory captured 2½ years earlier by the Japanese Imperial Army. As the heated battle raged, communications between the Japanese troops and their commanders were cut off. During the ensuing confusion, surviving members of Shōichi Yokoi’s platoon evaded capture by escaping deep into the tropical jungle. In the absence of orders from their superiors, as many as 1,000 troops hid in caves and dense vegetation, succumbing over time to starvation, capture, and suicide. Yokoi, the last known survivor of the battle, was discovered by two American hunters setting fish traps in 1972, 27 years after the end of World War II. Malnourished but still under standing orders to resist capture, Yokoi attempted to disarm one of the hunters before being overcome and marched to the local police station. Yokoi was returned to Japan a few weeks later to a hero’s welcome and to a world he could not have imagined. He died in 1997 after having spent two years less time in postwar Japan than he did waiting for a new set of orders from inside a cave in Guam.

Few of us are as resolute, persevering, or as unquestioningly loyal as Shōichi Yokoi. In his story, the chain of command was irretrievably broken, and as a result, his orders stood immutably frozen for 27 years. Your team may not be able to wait even 27 minutes for direction; nor should they, when something goes wrong. Many times, things go from bad to worse precisely because of inordinate delays while the team awaits answers to questions that have made their way up the chain of command. Decentralizing how decisions get made and delegating levels of authority to members of the team along the chain of command is one of the best ways for leaders to head off emerging issues and avoid having small problems becoming bigger ones. Often, there is not just one chain of command operating at once in an organization, but many. If all those chains are elevating a combination of routine and urgent messages all at once, it is more likely the decision maker(s) at the top will be overwhelmed and timely responses to the most important issues may be delayed.

Managing my first Super Bowls, it seemed like almost every problem was elevated to someone sitting at NFL Control. I know that’s an exaggeration, and that many decisions were being made out in the field. The high volume of radio and phone traffic, however, resulted in a queue of issues waiting either for me or someone in the command center to respond to in some order or priority.

One of the areas of most frustration for our supervisors and teammates in the field, we learned, was “waiting for answers from NFL Control.” From my perspective, it felt as though an enormous number of requests for noncritical decisions from nearly every area of the business were thrown into a funnel; the funnel narrowed down to a constant, high-pressure stream to be handled by a very small number of people. So, when falling snow and ice, unfinished construction, overwhelmed gates, and long delays occupied all of our attention in the command center, we were unable or unavailable to provide direction for many routine decisions that were normally elevated to NFL Control. More decisions HAD to be made at different levels along the chain of command or in the field and on-the-spot.

There was not one decision-making chain, but multiple chains, all operating at the same time and terminating in the same place. Some were directly involved in managing the many difficult challenges that day. A great many more were not affected, but they were still sending information and requests for action on other issues to their “prime decision maker” at NFL Control.

In the aftermath, and following lengthy and exhaustive consideration, we determined that it was essential to push more authority for decision making down each chain, away from NFL Control. The command center would continue to be the location where issues of the greatest implications for the game, event, and organization were evaluated and managed, or where responses requiring the greatest degree of coordination were directed.

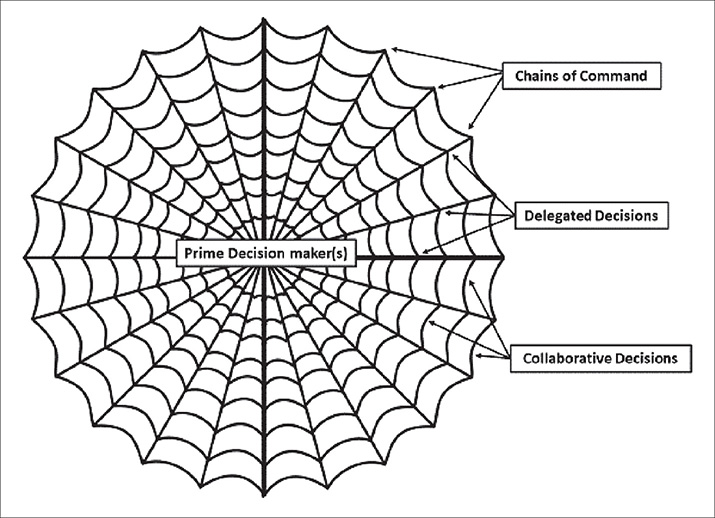

We delegated decision-making authority for managing many smaller, localized matters to supervisors and teammates on the ground. Along with that authority, we assigned responsibility for developing collaborative, coordinated solutions to localized problems directly between the chains of command most affected by the issue and in the best position to solve them. This interconnectivity between chains of command formed more of a web of decision making. (See Figure 10.1.)

FIGURE 10.1. Web of Command

Providing quick, relatively low-cost solutions to lesser experiential problems were similarly delegated. Any teammate could take the name and e-mail address of a fan whose clothes were torn by a sharp edge on a barricade or stained by a dirty seat and agree on the spot that we would pay for repair, replacement, or dry cleaning without getting clearance from NFL Control. (What’s a $15 cleaning bill on an $800 ticket?) A gate supervisor was assigned to every security checkpoint who could make decisions on better organizing queues, call directly for maintenance or repairs, or communicate with other gates to divert excess traffic to less-crowded locations. In addition to streamlining decision making and enabling NFL Control to better focus on handling bigger, more impactful, and more encompassing problems, this new redistribution of authority also resulted in the entire team taking a greater ownership over their personal contribution to the fan experience at the Super Bowl.

To be entirely accurate, the ultimate decision maker at the NFL on any given day is, of course, the commissioner and above him, the owners of the 32 football clubs. On Super Bowl Sundays, the authority to make operational decisions had been delegated to those of us at NFL Control, and we only occasionally had the need to elevate problems up to those highest of levels.

Think about how the chains of command for your business, department, or project are structured. When the most senior levels of management are absorbed with so much routine decision making that teammates regularly spend an inordinate amount of time waiting for answers, the organization is not well positioned to respond to an unfolding problem or crisis. In such an environment, important deadlines can be threatened, small problems can fester into big ones, and things that could have been made to go right go wrong. Define what kinds of challenges, questions, or problems need to be elevated to the highest levels, and what can be handled on the supervisory or field level. Identify the limits on financial impacts of decision making. That is, determine the cost, if any, that you will allow each level in the web of command to commit to in solving localized problems.

When something does go so awfully wrong that senior management is entirely absorbed defusing an existential problem, we cannot allow a rigid decision-making structure to cause every decision to stall, or operations to grind to a halt. Shōichi Yokoi spent 27 of his prime years hiding in the jungle waiting for orders that would never come because he and the rest of his unit were given no authority to make decisions if the chain of command was interrupted. Before being faced with a crisis, identify and communicate how you expect each level along the web of command to operate when the focus of senior management is diverted to solving more major problems. Identify one or more interim decision makers who senior management can rely upon to manage routine operations; pass along to senior management only information that is relevant to solving a bigger problem.

Streamlining and decentralizing decision making may require a decided culture shift in your organization. Developing a team-oriented culture focused on collaborative problem solving is the next step in preparing to handle the things that may go wrong.