12

MANAGING THE INVERTED PYRAMID

A starched white shirt with an anachronistic paper collar, a pair of crisply pressed navy-blue pants with a pencil-thin line of piping, a tight-fitting double-breasted jacket trimmed above the hips, and a pair of thick white cotton gloves. That was our uniform at Radio City Music Hall.

At that time, Radio City Music Hall was the largest theater in the world, just shy of 6,000 seats. It was as much an architectural wonder during the 1970s and ’80s as it was when it opened its polished brass doors in 1932. We ushers had a language all our own, which included hand signals that were visible over long distances, despite the theatrical darkness thanks to our white gloves. With a series of hand gestures, an usher standing in Aisle A on the 50th Street side of the building could communicate with the usher captain, standing way over in Aisle H (a city block away), that there were 150 available seats in Aisle C.

Saturdays and Sundays were the theater’s busiest days by far, and no one ever had those days off. It was mandatory for Radio City Music Hall ushers to go to “Sunday School” about a half-hour before the theater opened for the matinee. The entire crew gathered in a large circle around Bill Davis, the senior theater manager, dwarfed in the magnificence of the 60-foot high Grand Foyer. Mr. Davis imperiously reviewed the schedule for the day, delivered news about upcoming shows, rattled off important announcements on a variety of subjects, and drilled us mercilessly about everything he just said, or had said at previous “Sunday School” sessions. If we were asked a question and didn’t know the answer, there was a reasonably good chance we would be verbally humiliated, and an outstanding possibility of being sent home without pay. The “service staff,” doormen who were a minimum of six feet tall, and the more altitudinally challenged ushers, hailed from a diversity of backgrounds, neighborhoods, and cultures. Notwithstanding what made us different, we had two things in common. We were incredibly proud to be working at “the showplace of the nation” (and we hated the guy).

Occasionally, Mr. Davis sermonized about the significance of working in such a remarkable place. Radio City Music Hall meant something to people, he said, and we meant something to the delivery of an experience in front of the curtain that complemented the quality of the experience presented from the stage. If we had thought about it, we would have recognized that Mr. Davis’s weekly “Sunday School” sermon, his deadly question-and-answer session, and his incessant, uncompromising insistence on excellence in every detail communicated that we were part of the guest experience, part of the show, and as such, essential to the business. If only he had outright said that.

When the patrons arrived, the first representative they met was not a highly-paid C-level executive from the suite of offices hidden above the arched ceiling of the auditorium. It was the doorman managing the queue. The patrons purchased their tickets not on the stage from the producer of the show, but at one of the tiny box office windows from another barely compensated employee. They presented their tickets at the door not to the lead singer, but to an usher. And, none of the people they would interact with between the lobby and their seats were members of the Rockettes. The people were ushers and concessions workers. The fact is, in most businesses in today’s experience economy, the people you count on the most to deliver your company’s brand message are often the least paid and/or least appreciated—the customer service representatives, online chat agents, salespeople, clerks, cashiers, security guards, and, yes, even ushers. They may actually be the ONLY people your customers will ever meet in person, online, or over the phone.

Frequently, the only training customer-facing staff members receive is procedural in nature. They are instructed how to clock-in and clock-out when they report to work, log into their computer, operate the cash register, write up an order, fill out an expense report, allow only properly credentialed people past a certain point, or direct a ticket holder to the correct seat. Ensuring that the staff can do their core jobs accurately is essential to a high-functioning organization, but it is only half the job. We have all encountered people working for a wide range of companies and government agencies who may be efficiently and precisely accurate but deliver a memorably miserable experience.

Enlightened leaders understand the importance of developing an environment where every representative of the brand—whether they are the lowest paid or are more competitively paid employees, contracted staff, or vendors—care as much about each other and the customer as do their better compensated, behind-the-scenes colleagues. It is paramount to engage the customer-facing staff to represent themselves as an essential delivery system for your brand’s experience. We have to transform them from a roster of employees into a team, and from a collection of colleagues into teammates. Our teammates must fully grasp the importance of their role, and how dependent the company, brand, and/or project are on them. To realize this, it is incumbent upon managers and leaders to reinforce that message directly with words, actions, and behaviors.

TURNING THE PYRAMID UPSIDE DOWN

The ancient Egyptians built the earliest pyramids more than 4,600 years ago, and they remained stable and durable by planting the biggest flat surface firmly on the ground. Although the ancients have long departed, the pyramids stand in silent testimony to the Egyptians’ ingenious feats of engineering and construction. No one has had to make any sort of adjustments to keep the pyramids right where they are, in the very same location and oriented in the very same position.

Most organization charts organize and manage workforces in the shape of a pyramid. The large base at the bottom is typically composed of positions considered the least essential, empowered, and compensated. These individuals are directed by a series of managers in levels of diminishing size and increasing responsibility as one ascends through the structure, finally reaching the senior leadership—the smallest number of individuals in the positions of ultimate authority—at the very apex of the pyramid.

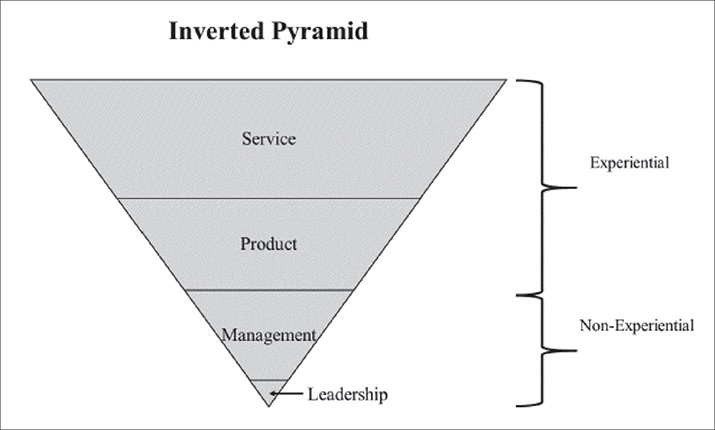

I believe organizational pyramids should be precariously poised on the tip of an inverted pyramid. (See Figure 12.1.) Because so much is riding on direct or indirect human interactions with the customer, I put the most populous group at the top to symbolize their importance, rather than at the bottom. I call this front-line staff the service team because that’s what they are there to provide—outstanding service—whether in the form of a simple greeting; assistance; conflict resolution; a sale; or a safe, clean, and smoothly operating environment. If any of these touchpoints go wrong, more problems can follow.

FIGURE 12.1. The Inverted Pyramid

The next most important group is the product team. This is the group critical to delivering on the customer’s expectations of the brand. Sometimes they are very visible and synonymous with the product or service itself (singers, dancers, athletes, designers, physicians, and nurses) and sometimes they are entirely unseen but nonetheless essential to the delivery of a flawless experience (mechanics and engineers, chemists and researchers, assembly line workers, stage hands, project planners, programmers, and technicians). Membership in the service and product teams is not mutually exclusive. It is possible to be simultaneously part of both. We depend upon physicians and nurses for their professional skills, but no matter how stellar they are at delivering medical care, the experience is better when they have good bedside manner. We may have been greeted at the departure gate by the most ebullient attendant and thanked at the end of the flight by the most gracious and skilled pilots, but if the baggage handlers don’t care about where your luggage goes or how it looks when it gets there, the customer’s overall experience and relationship with the brand can be significantly endangered.

The next team in descending order of size is the management team, a group that is almost always invisible to the customer, but upon whom members of the product and service teams rely for guidance and support. This is the level of teammates that may not directly deliver the customer experience, but can significantly impact the effectiveness, efficiency, and attitudes of those who do. It is populated by managers and supervisors across the entire business, and teams of professionals representing marketing, financial services, human resources, and other essential functions, They, too, have a part to play in ensuring that things don’t go wrong within their area of responsibility, from overseeing informed budget planning and accurate forecasting to compliance with government regulations and the development of effective promotional campaigns.

Finally, the smallest group upon which the entire pyramid balances is the senior leadership. This is the level that implements policies, establishes culture, and sets the direction of the company. The fact that they are on the bottom of the inverted pyramid does not belie their importance. The entire organization balances on the extremely fine and precarious point the senior leadership represents. The decisions they make, the direction they provide, and the environment they promote among their teams on every level can keep the pyramid upright or cause it to teeter and topple. In this model, the responsibility to keep the pyramid upright belongs to everyone on every level. If something goes wrong on the service or product levels, senior leadership has the responsibility to make decisions that can readjust the balance. Think of the United Airlines conflict from Chapter 1. An exceptionally poor experience was delivered to the passenger, but decisions by senior leadership may well have made the effect on the brand worse, more far-reaching, and more long-lasting.

ORGANIZATION CULTURE CAN MAKE THINGS GO RIGHT

Without question, establishing and nurturing a collaborative corporate culture that recognizes the essential contribution that every individual can make at every level will help make things go right more often. Kevin Catlin, managing partner at Insight Strategies, Inc. in Los Angeles, California, likes to share the story with his clients of a practicing surgeon who was being interviewed by a news crew as he walked through the halls of the hospital he also managed. The doctor interrupted the interview briefly to chat with a janitor working in the hallway. After a few moments, the two chuckled and shook hands. The interview resumed as the janitor returned to cleaning a windowsill. A junior reporter asked the janitor what he and the surgeon had discussed and was startled by his response:

“Saving lives.” What possible role can a janitor in a hospital play in fulfilling its mission to save lives?

“This hospital is teeming with germs,” he explained. “Every time a child touches this windowsill as she walks past, puts her hand to her own mouth as children often do, then kisses Grandma in her sick bed, she can literally kill her with a kiss. That is not happening on my floor.”

The surgeon in this story is a rare individual who simultaneously inhabits all levels of the inverted pyramid. He was the senior leader of the company who, in fact, had had a long history of successfully turning around struggling hospitals. He was a practicing surgeon who was both part of the product patients came to the hospital to receive and he had a clear and personal focus on the service side of the equation. His chief contribution, as illustrated in this story, however, was establishing a culture that embraced a clarity of purpose.

The mission of the hospital was to save lives. Everyone in the organization understood their contribution to achieving it. This is not about getting employees to care about their job. Caring only about the job is simply an act of self-preservation. We must imbue teammates with a genuine understanding and appreciation of the contribution they make. When they do, they care about doing things right, and keeping things from going wrong, just like our valued friend at the windowsill.

In a 2013 Forbes.com article, Kevin Kruse, founder and CEO of LEADx, offered one of the finest definitions of leadership: “Leadership is a process of social influence which maximizes efforts of others towards achievement of a goal.” Kruse explains that his definition is not limited by authority or power, and that the people being influenced don’t need to be “direct reports.” It has no requirement of title or personality traits, and acknowledges that “there are many styles, many paths, to effective leadership.” It is further defined by “a goal, not influence with no intended outcome.”

Let’s face it. You are just one person and if you are leading a company, business unit, or project team, there is a lot on your shoulders, for example: the profit-and-loss (P&L) performance; the launch of new brands or products; and the management of a myriad of operational details. Leading is not the same as directing every activity or fixing everything that goes wrong. I learned this the hard way because I’m a perfectionist. I want everything to be flawless and I sometimes did things that I could have had other people do because, well, since I know how I wanted it to turn out, wasn’t it just easier to do it myself?

Kruse suggests that leading is not telling people what to do or how to do it. He says that leadership is influencing and motivating those around you to get the best results possible. The team we need to assemble is composed of people who WANT that, too. There is nothing so demoralizing as people who worked hard but didn’t accomplish what was expected of them. Many times, it was because no one told them what was actually expected of them or what goal they were working toward. You can be an expert archer and shoot arrows with exceptional precision. But, if you shoot an apple cleanly off someone’s head, it doesn’t count if you were supposed to be aiming at a nylon target safely attached to a bale of hay.

You might think that excitement and the desire to do a great job was preprogrammed into everyone working on the Super Bowl. After all, you’re working at the Super Bowl. But, checking credentials at a gate for eight hours, with only the distant, muffled roar of the crowd to connect you to the excitement, you might not feel all that invested in providing a wonderful fan experience. Perhaps you are in a location where you don’t see fans at all.

In an average year, there were 18,000 people who wore Super Bowl credentials. Fewer than 1,000 people worked for the League Office. The rest were stadium staff, concessions and catering workers, temporary staff, contracted security, production staff, drivers, host committee volunteers, and many others. They worked for a patchwork quilt of different companies, contractors, and agencies. But, to our customer, the fan, they ALL worked for the NFL on game day. Every one of them was an ambassador of the brand. Given their diverse responsibilities, pay scales, and employers, how was it possible to get everyone on the same page? By making sure they were reading the same book, one that clearly communicated the mission, the purpose, and the values shared by everyone working on Super Bowl Sunday.

DEFINING THE TEAM’S MISSION

The project team’s mission is often related to, but not the same as, the company’s business objectives. The metrics used to measure their respective success can be quite different. Business objectives may include: achieving certain financial goals, increasing the company’s share of market, enhancing customer perceptions of the brand, or boosting awareness of a new product. But, an effective mission for the broader team is frequently expressed in relatable terms that every teammate can share and embrace. By making the mission common to everyone, regardless of their role, team members can contribute significantly to the company meeting its objectives, whether directly or indirectly.

A mission statement should consist of a single sentence that is easy to understand, personalize, and express. For example, an airline might establish this shared mission: “We ensure that when passengers deplane, they are already looking forward to traveling with the company again.” Nearly everyone who works for the airline can understand how their jobs can impact that mission, not only customer-facing gate staff, flight attendants, and pilots, but also baggage handlers (luggage should arrive the quickest and safest), custodial staff (our cabins should be the cleanest), and the Information Technology (IT) department (our website should make finding, booking, and paying for a flight the easiest). The mission given above will beat “we have to increase revenues by 25 percent” every time. It’s relatable, personal, applicable, and easy to sustain.

Think of your own company, department, or project, and you will discover that anyone and everyone can have an impact your customers’ experience, either directly by delivering a positive interaction or by contributing to an environment that ensures they occur. At a sports stadium—which includes food preparers, escalator mechanics, groundskeepers, parking lot attendants, IT technicians, bus drivers, and electricians—there is no role that cannot contribute to, or potentially detract from, creating lasting memories. If everyone understood their integral, incremental contribution to our purpose, like the janitor in the hospital or the guard at the gate, things would go right more often. Conversely, things go wrong more often when teammates are ambivalent, unappreciated, and do not understand the importance of their role and how much we count on them. So, as leaders, we have to tell them. Often.

THE EARLY WARNING SYSTEM

Every leadership group, regardless of industry, can take maximum advantage of the early warning system built into their organization to reduce the number of things that could go wrong or contain the severity of their effects when they do. At the Super Bowl, our early warning system was composed of 18,000 credentialed staff and contractors. As leaders, our responsibility did not end with defining and sharing the mission and how each teammate fulfilled our shared purpose. We also recognized that the flow of communication could be even more powerful and effective if we encouraged it to move more freely in both directions. Leveraging the real-time observations of all 18,000 teammates, and communicating our encouragement that they should share them, provided us with indispensable diagnostics on how we were performing. The team in the trenches—invested in the mission and clear on their purpose—have more eyes, ears, and brains in the field, and can help us make midcourse corrections in real time to avoid having small problems become larger ones. We shared the notion that it is everybody’s job, and it is part of everyone’s purpose, to be on the lookout for something that didn’t look right. It is not, by any means, an understanding that is implied. We, as leaders, must make that expectation explicit.

During the weeks leading up to the Super Bowl, we hung banners from hundreds of light posts, across roadways, and on hotels and office buildings. On a windy day, a banner might pull loose from the hardware that kept it in place. It was not just the banner-hanging company responsible for refastening the banner to the building. It was not solely the NFL event department staff member who contracted the banner company who had to tell them it was flapping about in the wind. It was the job of any one of the 18,000 teammates who passed by that banner to let us know it was loose. By doing so, we greatly increased the likelihood that it would be repaired before it could pull away from the building entirely and cause injury or damage to property.

We all know this as the “see something, say something” philosophy promoted by the law enforcement and security communities. It applies just as much to our businesses and projects. In the United States, reporting problems is easy. If we see a suspicious package, what we believe to be a crime being committed, or a situation that requires help, we call “9-1-1.” We need to make it just as easy for our team to surface issues, as well. For members of the Super Bowl team, we printed a hotline number on the back of every credential, along with the expectation that they would use it to communicate a problem. Any problem.

Collectively, businesses wisely invest billions of dollars on security equipment and personnel each year to prevent physical and financial loss. Empowering every teammate to identify emerging or existing problems, and giving them an easy way to inform management, can significantly add to our preparedness without significant cost. It is essential to communicate our belief that it’s everybody’s job to be part of the early-warning system, and that time is of the essence when something looks like it’s going wrong or has gone wrong.

Keep in mind that the larger and more dispersed the workforce, the more important it is for us to provide a simple way to elevate their observations and concerns. Certainly, informing a supervisor is the usual, most timely, and most appropriate first step. But if a supervisor is not reachable or the nature of the problem is not directly related to the teammate’s core responsibilities, a central reporting system can be very powerful. That’s why I like the hotline approach—a common and easy-to-access text or phone number any teammate can use to elevate literally anything that might be going wrong. On the receiving side of the hotline, assign an individual or team to monitor incoming reports of threats and problems, and to route information quickly and efficiently to the teammates who are best qualified to solve or manage them. Be sure that teammates who use the hotline receive a confirmation that their report has been received and that it is appreciated.

![]()

A useful way to communicate our reliance on every teammate’s vigilance is to distribute laminated wallet cards that display both our common mission on one side and the hotline information on the other. Putting both messages in the same convenient and accessible place can reinforce our expectations and our dependence on our team. Getting them to use it, however, requires building a culture of empowerment.