5

LIVING IN THE LAND OF THE LIKELY

Torii Hunter’s leaping grab of a drive well over the wall in right-center field robbed Barry Bonds, of the San Francisco Giants, of a certain home run in the first inning. Yet, it did not win Hunter, of the Minnesota Twins, the Most Valuable Player (MVP) honors in the 2002 MLB All-Star Game, held on July 9, 2002, in Miller Park, Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Later, with two outs in the bottom of the third, Bonds posted a pair of runs, lining a pitch from Roy Halladay, of the Toronto Blue Jays, over the right field fence to give the National League an early 4 to 0 lead. Halladay was already the American League’s third pitcher in as many innings. The four-run difference shrank as the score seesawed through the top of the eighth inning. With one man out, Omar Vizquel, of the Cleveland Indians, tripled into the right-field corner scoring Robert Fick of the Detroit Tigers from second base and tying the game.

Between the two leagues, only five pitchers remained of the 19 pitchers named to the All-Star Game rosters, and team managers Joe Torre and Bob Brenly faced the prospect of the game going into extra innings. As it was customary for All-Star team managers to use all of their players during the game, Torre sent two of his remaining relievers to the mound in the eighth and ninth innings, throwing only 11 and 14 pitches, respectively. Brenly pulled reliever John Smoltz, of the Atlanta Braves, for a pinch hitter after throwing only eight pitches in the ninth inning, leaving each team with just a single hurler to take the game into extra innings.

After the American League stranded a man on third base to finish the top of the 11th inning with the score still deadlocked at 7 to 7, the umpires walked to the front row of field-level seats to explain the dilemma to Commissioner Bud Selig. Neither team manager wanted to risk injury to their final two pitchers by having them throw for more than two innings in an exhibition game. Deliberations on how to finish the game were made in full view of the fans in the stadium and 14 million viewers on national television. As Captain Murphy would have predicted, the game ended three outs later in a reluctant tie, as had been decided during the awkward field-level meeting, amid fans booing and chanting “Let them play! Let them play!” There was no winner of the 2002 All-Star Game and no MVP was named for the game. But thanks to Hunter’s spectacular catch in the first inning, the American League extended its undefeated All-Star streak.

Extra innings, of course, are not unknown in baseball. According to The Washington Post, there were 185 lengthened matches out of 2,428 games during a recent season, comprising 7.6 percent of the schedule. Of those, 63 (2.5 percent) lasted 12 innings or more. Of course, All-Star Games are not remotely like regular season games. But, knowing that a tie at the end of nine innings is not unheard of, and that even longer games are entirely possible, it is hard to understand why a rule was not in place well before Curt Schilling, of the Arizona Diamondbacks, unloosed the first pitch of the night.

A tied score after nine innings was 100 percent predictable, and a 12-inning game was totally within the realm of possibility. The first tied score in 73 years of All-Star Games was in 1961, when rain forced a premature end with the score deadlocked after nine innings. That All-Star teams had never run out of pitchers in the past was clearly no prognostication of the future, notwithstanding that a 15-inning game was played to a National League victory in Anaheim Stadium on July 11, 1967.

Smarting from fan criticism, Major League Baseball made good on its promise to ensure this would never happen again by initiating a rule that some position players, including pitchers, be held in reserve even at the risk of them never playing, and that certain players be permitted to re-enter the game even after they were replaced. A definitive conclusion to the game was particularly important in later years when baseball ruled that the top seed in the World Series would be determined by the winner of the All-Star Game, a rule that temporarily addressed the event’s relevance to fans.

THE OUTCOME IS PREDICTABLE WHEN YOU DON’T PLAN FOR THE PREDICTABLE

What the 2002 All-Star Game teaches us is the importance of planning for the predictable. The probability of a game going into extra innings was reasonably high, and in baseball there is no telling how many innings it will take to break a stalemate. The notion that a team could run out of pitchers during a game was an entirely imaginable possibility. Several years before, the NHL had foreseen the possibility of a tie in their All-Star exhibition and instituted a rule to play one five-minute overtime, followed by a shootout to break a stubborn tie. As hockey fans know, ties used to be a common outcome in the regular season, but this is the format now used in the regular season as well.

It may sound silly, or at least overcautious, to have had a rain plan for an outdoor event in the desert city of Phoenix, Arizona, and before Super Bowl XLII on February 3, 2008, I would have agreed with you. The historical average monthly rainfall totals for the city in the month of January is 0.77 inches, but during the ten days of scheduled fan activities leading up to the game, we enjoyed about half the year’s expected allotment of liquid sunshine. I left my hotel one afternoon in a torrential rainstorm and grabbed one of the gifts that had been graciously left in my room by the Phoenix Convention & Visitors Bureau when I checked in for the month. I didn’t for a moment think about how strange it was that an umbrella was one of those gifts, but I was grateful it was there. I grabbed it out of the basket and set out for the convention center, where the NFL Experience and the Media Center were being set up. When I opened the umbrella, the inside a little too cleverly said: “If your meeting was in Phoenix, you wouldn’t be needing this right now.”

I’m sure you’ve listened to weather reports, heard a forecast of a 20 percent chance of showers, and thought that the best way to ensure that it doesn’t rain is to bring an umbrella with you. You leave your umbrella home anyway because, after all, it’s only a 20 percent chance. It may or may not rain, but here’s what I know for sure: if you do leave your umbrella home and it does rain, you will get 100 percent wet. Even in Phoenix. The question is, how will that ruin your day, your project, or your event, and is it worth having a plan for when the unlikely happens?

Probability is just one key factor master planners consider when imagining what situations are worthy of the time and resources required to develop contingency plans. Safety considerations, of course, are paramount. Anything foreseeable going wrong that could result in physical danger should zoom to the top of any list. Another important factor is the damage that can be done reputationally and economically by an unlikely, but possible, occurrence. The potential impact on your brand or bottom line can escalate the need for a contingency plan for scenarios for which probability alone might not qualify.

Like Major League Baseball’s All Star Game, probability seems to work against us when a project occurs annually or with regularity. Just ask Robert Krumbine, the chief creative officer for Charlotte Center City Partners (CCCP) in Charlotte, North Carolina. The mission of Krumbine’s organization is to “envision and implement strategies and actions to drive the economic, social, and cultural development of Charlotte’s Center City.” Among many other programs, CCCP participated as the producer of the “Avenue of the Arts” component of a street festival called “Taste of Charlotte.” The annual three-day event, running from Friday to Sunday, has been operating for decades and, of course, from time to time weather can dampen spirits and attendance. One recent edition experienced a bit more than that.

The festival opened on a sunny spring morning, as 125 local artists settled in to their tents, fussing over displays of their handiwork. Krumbine, as he always does, checked in regularly throughout the day with multiple weather resources to stay on top of any changes in the forecast. “Suddenly,” he recalls, “we heard about storms brewing to our west.” It wasn’t an unusual occurrence in the spring. “We didn’t necessarily think the worst. You may get a little bit of rain, a little bit of wind, and everybody just battens down the hatches for a few minutes.” Krumbine kept his eyes open, and when he and his associates saw a purplish wall of clouds bearing down on the festival, he knew it was time to act, and fast. He jumped into a cart and started warning guests to seek shelter as soon as possible. When the front hit, it was “like a train on a track right through the middle of the festival,” destroying many of the artists’ booths and wares. The winds lifted a 30- by 40-foot tent off its moorings and sent it smashing through a nearby office building’s glass windows.

Krumbine saw more structures ready to rip away from their tethers, so he jumped off the cart, and with his team, physically held tents in place to reduce the extent of the damage to the artwork and the structures around them. In retrospect, holding metal tent poles in place during a severe thunderstorm “was not a very smart thing to do,” he acknowledges. “It was a knee-jerk reaction.” Happily, no one was injured during the fast-moving high-wind event, but the festival site was devastated. Krumbine, city agencies, and all the important stakeholders quickly gathered in the police department’s mobile command center to assess the damage and decide what to do next. They determined that by suspending operations for the rest of the day and working through the night, they could get the festival site repaired and reopened for the following morning.

“It completely changed the way we think about contingencies now,” Krumbine recalls. “Now, we spend so much more time looking for potential problems and how we are going to deal with life safety first. Where do people go during an emergency? Now, we use that overlay for other events we do.”

It often goes that way. Something goes wrong and it changes how well you can imagine something similar happening again. Charlotte now requires a minimum standard for tented structures and a greater amount of ballasting for tents to keep them securely fastened to the ground. “The Taste of Charlotte” incident also teaches us the importance of having a place for senior officials to go to discuss important issues away from the limelight, and certainly away from the public and the media. So while you are imagining what can possibly go wrong, also imagine where you will rally the important stakeholders when you have to make difficult decisions and how you will gather them.

MAY THE ODDS BE EVER IN YOUR FAVOR

Whether it’s rain or any other factor that could derail your project, a 20 percent chance of some single thing going wrong is actually a pretty high probability. It may sound that this means you have an 80 percent likelihood of success, but unless you truly believe that’s the ONLY thing that can go wrong, think again. It simply means that you have an 80 percent chance of that one specific thing going right. There are still a lot of other things that can go wrong that can eat away at that 80 percent escape from disaster.

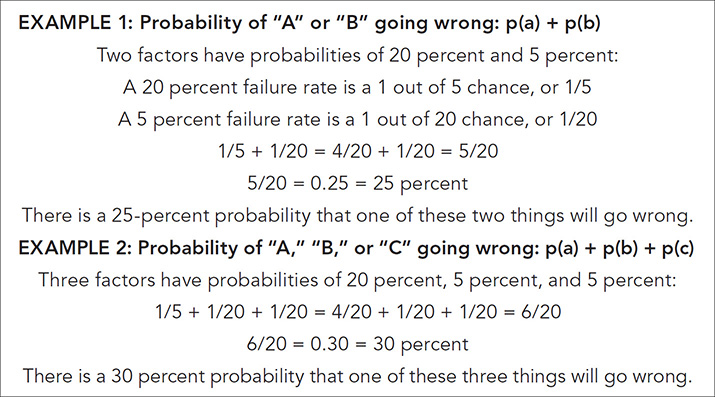

The more complex the project, the more likely something is going to go wrong somewhere, sometime, or somehow. Every time you imagine the possibility of something going wrong, you should add the probabilities together to determine how likely your project will be afflicted with just one of these failure factors (see Figure 5.1).

FIGURE 5.1. Calculating Partial Failure

Let’s say that in addition to the one thing that has a 20 percent probability of failure, you imagine something else that might have only a 5 percent likelihood of going wrong. That means if you escape the first problem, which by your own reckoning you will do 80 percent of the time, your likelihood of complete success goes down by another 5 percent. Now, the chance that you’ll be free and clear of one of these two sources of anxiety is down to just 75 percent of the time. Add another factor that has a 5 percent probability of failure and the likelihood of enjoying a success—unencumbered by any one of those three issues—is now down to only 70 percent. Keep adding factors that can go wrong, and you can see that your likelihood of total, unequivocal success drops with every single one. The more complicated the process or project, the more details, the more factors in the equation, the more probability that at least something is not going to go well. Consider a project as complex as the Super Bowl, and you can imagine that plenty is going to go wrong on Super Bowl Sunday. Every time. The trick, of course, is to make sure that the things that don’t go right are the least important, the least damaging, and the least visible. That, of course, was not always the case.

I wouldn’t waste much of your precious planning time calculating your likelihood of complete escape from something going wrong. A total escape is near impossible. This is just an illustration of why it’s important to imagine and eliminate from the system as many things likely to go wrong as possible, or to try to make them less likely. Few risk factors will be as high as that 20 percent likelihood of scattered showers. If you have many risk factors, your project already has real problems.

Your contingency planning framework will look a lot like a classical decision tree: “If this happens, we do that. If that happens, we do this.” It will unquestionably save your project valuable time and resources, and result in better and more informed decision making if you are acting on a contingency plan rather than trying to figure out your response from scratch when the heat is on. You will have more time to gather more intelligence and opinions while also reasoning through all of the ramifications and potential consequences of any course of action if you imagine them ahead of time.

![]()

A few hours after the conclusion of Super Bowl XLVIII between the Seattle Seahawks and Denver Broncos, the temperature plummeted and by morning, eight inches of fresh snow had blanketed the New York metropolitan area, stranding many out-of-town fans and guests at area airports. If that snow had fallen just 12 hours earlier, the game would have been very different. It was an unusually brutal winter. Deep “polar-vortex” cold often dropped temperatures into the single digits. Heavy snows ahead of the game delayed construction and preparations at MetLife Stadium in East Rutherford, New Jersey. Snowfall in January and February in the northeast was, of course, predictable. What wasn’t predictable was exactly when it would snow and how much. So, contingencies had to be built into the plan in case it snowed a lot and at the worst possible time.

The intrigue of canceling, postponing, or moving a Super Bowl made for irresistibly good news copy. New York Daily News journalist Bill Price sounded the alarm more than a year ahead of the game: “According to the new Farmer’s Almanac, which will be printed soon, the weather on Feb. 2, 2014—the same day Super Bowl XLVIII is scheduled to be played at MetLife Stadium—will feature ‘an intense storm, heavy rain, snow, and strong winds.’ ” He continued, “Not good news for organizers of the event, which will be played outdoors in a cold-weather city for the first time in history.” He went on to explain that Pete Geiger, editor of the Farmer’s Almanac, had told the Associated Press “This is going to be one for the ages.”

I was repeatedly asked about the Farmer’s Almanac forecast and whether it made me nervous. “We’ve been in cold-weather cities before,” I told Bob Glauber, football columnist for Newsday. “We’ve been in situations where snow has fallen ahead of the Super Bowl. There are rescheduling scenarios for 256 regular-season games each year. Same thing for Super Bowls since the beginning of Super Bowls,” I assured his readers. Of course, I was nervous. Not because of the Farmer’s Almanac forecast, or any forecast made 13 months ahead of time. Besides, how much news would they have made if they predicted a beautiful Super Bowl Sunday? I was nervous because a major snowfall at a miserably unfortunate time was a very real possibility.

In the same article, Glauber went further in trying to reassure his readers: “One thing the league has going for it when it comes to being reasonably certain the game will go off as scheduled: Since the construction of Giants Stadium at the Meadowlands in 1976, no Jets or Giants game has ever been postponed because of weather.” (Thanks for trying to make me feel better, Bob, but a happy weather history doesn’t have any bearing on the likelihood of a future outcome.)

Throughout the processes of planning, execution, response, and evaluation, applying your imagination should never cease. But now that you’ve imagined enough challenges, let’s get down to planning those contingencies!