Incivility at times provides wonderful entertainment, but it creates anxiety.

—SUSAN HERBST (2010, 130)

I HAVE A short clip from a 2013 episode of Fox’s Hannity that I like to use to start classroom discussions of incivility. In it, Tamara Holder, a Democrat and Fox News contributor, and conservative radio host Billy Cunningham are having a conversation about raising the debt ceiling. Their disagreement escalates as Cunningham praises Rand Paul’s balanced budget and jabs his finger toward Holder, saying “Your ilk, people of your ilk….” Holder cuts him off, shouting, “Get your finger out of my face!” (“Holder and Cunningham Blow Up” 2013). As they watch, students tend to have one of two reactions. Some stare at me in shock, clearly uncomfortable with the behavior of the two television commentators. Others start chuckling at the politicos’ behavior, finding the exchange to be just another example of the ways in which politics becomes theater. Either way, the segment elicits a series of emotions in the students that shape their comments in class and their attitude toward the show and the argument being made about Obama’s economic policy.

In a move away from an emphasis on the “rational voter” (e.g., Downs 1957; Enelow and Hinich 1984; Page and Shapiro 1992), contemporary scholars of political behavior have welcomed affect into their theories. Emotions have been found to increase persuasion, shape candidate evaluations, and inspire engagement in “effortful” political activities like protest and letter-writing (Brader 2005; Cassino and Lodge 2007). Generally, different emotions are associated with approach and avoidance tendencies: an approach motivation is linked to positive feelings, and negative feelings are associated with avoidance (Cacioppo, Priester, and Berntson 1993; Elliot, Eder, and Harmon-Jones 2013). However, anger stands out as a negative emotion that is tied to an approach motivation. In politics, anger encourages citizens to get involved—to protest, write letters, or express their opinions—while disgust and anxiety turn citizens away from political engagement (Brader 2006).

The general assumption behind much of this research is that most people have similar emotional responses to political stimuli: negative advertisements produce negative emotional responses across all study participants, and positive advertisements produce positive emotional responses. When individual differences have been incorporated, the most common focus is on the effects of partisanship. However, in the previous chapter, I hypothesized that conflict orientation influences affective and behavioral responses to political incivility, producing heterogeneous effects on individuals’ emotional responses, information-seeking patterns, and political engagement. The first of these hypotheses, the emotion hypothesis, suggests that in the face of incivility, individual citizens will have different responses, and these different responses will be conditional on the person’s conflict orientation. Conflict-avoidant citizens will have stronger negative emotional responses to incivility than their conflict-approaching counterparts. Conflict-approaching individuals will have more positive emotional responses to the same information and tone. Returning to the earlier example, my theory suggests that the conflict-approaching students were the ones who laughed at the Holder-Cunningham exchange, while my conflict-avoidant students cringed or looked uncomfortable.

These expectations are borne out in the data. This chapter reports the results from two survey experiments in which participants were shown either a civil or an uncivil video clip and then asked about their emotional response to that clip. I found, as expected, that conflict-avoidant individuals recoil from expressions of incivility in the media, while conflict-approaching individuals relish it. Conflict-avoidant participants reported greater feelings of disgust, anxiety, and anger after watching uncivil media, whereas conflict-approaching participants overall reported less of these emotions at roughly equivalent levels for both civil and uncivil video clips. Conversely, the most conflict-approaching participants reported significantly higher feelings of amusement and entertainment when assigned to watch the uncivil treatment. The conflict-avoidant, however, were no more entertained by incivility than by civil presentations of information. These results demonstrate that the interaction of incivility and conflict orientation leads to very different emotional responses across individuals.

These divergent outcomes complicate our understanding of the role of incivility in politics. On the one hand, incivility elicits emotions that draw people into the political arena, potentially increasing participation and citizen engagement. On the other hand, it systematically discourages involvement by the conflict-avoidant—people who are more likely to articulate positions in nonconfrontational ways. Furthermore, these findings suggest that incivility breeds incivility: nasty online comments and hateful outbursts at political rallies may be the result of the conflict-approaching individual’s enthusiasm for argument and confrontation.

EMOTIONAL POLITICS

Research on emotion and affect spans psychological subfields as cognitive, social, and neuro-psychologists attempt to determine the extent to which emotions are conscious or unconscious, a result of cognitive processes or the inspiration for cognitive action (Frijda 1986; James 1884; Lazarus 1994). Multiple theories seek to explain the nature of emotion and connect it to behavior and decision-making, and many of them have been applied to politics.1 One such theory suggests that emotion sparks different motivations that ultimately shape citizen behavior. Generally, this line of research suggests that positive emotions are associated with an approach motivation and negative emotions encourage avoidance (Cacioppo et al. 1993; Carver and Scheier 1990; Elliot et al. 2013). However, anger is often associated with both an approach motivation and negative feelings (Carver 2004; Harmon-Jones 2003; Harmon-Jones, Harmon-Jones, and Price 2013). These general emotion-motivation-behavior patterns play out in a range of social and political scenarios, with emotions shaping candidate preferences, persuasion, reliance on prior beliefs, and political interest (Brader 2006; Cassino and Lodge 2007; Huddy, Feldman, and Cassese 2007; MacKuen et al. 2007; Parsons 2010).

Political communication, and incivility in particular, can produce different emotional responses in citizens. For example, Brader (2006) shows that positive music in campaign ads cues enthusiasm while negative music and images evoke fear. While Brader focuses on nonverbal communication in order to ensure his effects are in response to the processing of emotions rather than a cognitive response to the substance of the message, others have focused on emotional responses to language (e.g., Gross 2008; Druckman and McDermott 2008), and particularly the language used in uncivil communication (Mutz 2015; Gervais 2014, 2015). Sociologists interested in Australians’ responses to situations of “everyday incivility” found that individuals’ emotional responses to uncivil experiences depend on whether the person is a witness or participant in the event. In focus-group recollections of these experiences, individuals who had participated were more likely to report feelings of anger, while observers reported more feelings of fear, unease, and disgust (Phillips and Smith 2004). Similarly, Gervais (2015) found that exposure to like-minded incivility provoked less of an emotional response in participants in an online discussion forum than did exposure to disagreeable incivility. Characteristics of the individuals receiving the message—their position vis-à-vis the person communicating through incivility—shaped their emotional and behavioral responses to the communication.

Like Phillips and Smith and Gervais, I argue that our responses to political incivility are more nuanced. Incivility does not elicit the same emotions across all individuals. Appraisal theory suggests that emotions are elicited based on an individual’s assessment of the personal significance of a situation, object, or stimulus (Lazarus 1994; Roseman 2008; Scherer 1999). From this perspective, we are constantly assessing the congruence between situations and our own motivations. If individuals are motivated to approach conflict situations, then they will have a different emotional response than if they are motivated to avoid conflict. In the case of political incivility, individuals’ motivations are tied not only to partisan identity but also to their conflict orientation: their desire to approach or avoid argumentative or confrontational situations.

EXPECTATIONS

Previous research has demonstrated that incivility can produce a range of emotional responses, from disgust, fear, and frustration to anger to excitement (Gervais 2015; Mutz and Reeves 2005; Phillips and Smith 2004). Certain individuals are more likely to experience these emotional reactions than others because of the interaction between conflict orientation and incivility. More conflict-avoidant individuals will be more likely to react negatively to incivility while conflict-approaching individuals will have positive responses to the same tone. I focus on three negative emotions—anxiety, disgust, and anger—and three positive emotions—amusement, entertainment, and enthusiasm.

I expect that when conflict-avoidant individuals are faced with political information that is expressed in a highly argumentative or uncivil manner, they will have a negative reaction, regardless of whether they agree with the information being conveyed or the people presenting that information. The conflict-approaching, on the other hand, will more likely react with enthusiasm or amusement to the expression of incivility in political media.

Looking first at negative emotions, the literature suggests that incivility could easily tap into the distinct appraisal themes and action tendencies of each. Perceptions of threat and uncertainty produce anxiety (Albertson and Gadarian 2015; MacKuen et al. 2007). If individuals prefer a world in which conflict is minimized, it seems obvious that they will perceive incivility as threating to the stability and habitual nature of their world. If an individual enjoys conflict, incivility is far less likely to produce the same feelings of threat or uncertainty.

Anxiety hypothesis: The more conflict-avoidant the individual, the more anxiety he or she will report feeling when exposed to incivility.

Whereas anxiety stems from feelings of uncertainty, disgust arises when a situation or stimulus violates expectations of moral purity (Horberg et al. 2009; Pizarro, Inbar, and Helion 2011; Rozin, Haidt, and McCauley 2008). The use of obscenity or other uncivil language has been tied to morality throughout American culture (Carter 1998; Feinberg 1988; Horberg et al. 2009), making it plausible that uncivil language would elicit feelings of moral disgust toward politics or the political discussion.

Disgust hypothesis: More conflict-avoidant individuals than conflict-approaching individuals will report feeling disgusted by incivility.

Appraisal theory suggests that individuals are more likely to experience anger when they assess a situation as wrong or unjust in some way (Lerner and Tiedens 2006; Russell and Giner-Sorolla 2011). Incivility’s ability to provoke anger, therefore, would depend not only on how an individual feels about conflict, but the person’s assessment of the situation in which incivility is used. In a political situation, this could be tied to partisanship; as Gervais (2015) has shown, partisans are more likely to experience anger when incivility is directed toward their own party than when it is directed at the opposing party. We can imagine that exposure to incivility might prompt greater anger among the conflict-avoidant—toward the media for sanctioning this type of language, toward political elites for using it, or toward politics generally. Furthermore, conflict-avoidant individuals who share the partisan perspective being attacked might be more likely to report anger than those who share the perspective of the attacker.

Anger hypothesis: Conflict-avoidant individuals will be more likely to report feelings of anger after exposure to incivility.

Partisan-anger hypothesis: Conflict-avoidant individuals who are exposed to disagreeable incivility will report greater anger than those who see the exchange as like-minded incivility.

While the conflict-avoidant are more likely to experience negative emotions, I expect those who are more conflict-approaching to have more positive reactions to incivility. Experiences generated by others that are also consistent with an individual’s personal motives evoke “liking” (Arnold 1960; Roseman 1984). Translated directly into my framework, mediated incivility is consistent with the conflict-approaching individual’s motivation to experience conflict and therefore will be liked. Similarly, affective-intelligence theory suggests that enthusiasm and satisfaction stem from the successful repetition of behavioral outcomes (Marcus, Neuman, and MacKuen 2000). From both perspectives, an individual who enjoys conflict situations will report experiencing incivility positively. Indeed, this is what Mutz and Reeves (2005) found: individuals who are excited by conflict also report that incivility has greater entertainment value. I assess individuals’ reporting of three positive affective states in the face of incivility: entertainment, amusement, and enthusiasm. I expect the patterns here to be the opposite of those found in the investigation of negative emotions. Whereas the conflict-avoidant will report no difference in their positive experience of the civil or uncivil video clips, the conflict-approaching will have a stronger positive reaction to incivility.

Entertainment hypothesis: The more conflict-approaching the individual, the more he or she will report being entertained by incivility.

Amusement hypothesis: The more conflict-approaching the individual, the more he or she will report being amused by incivility.

Enthusiasm hypothesis: The more conflict-approaching the individual, the more he or she will report enthusiasm about incivility.

EXPERIMENTAL MANIPULATION OF INCIVILITY

My first test of these hypotheses uses data from the six hundred participants in the Survey Sampling International (SSI) study. In the SSI study, after participants responded to the Conflict Communication Scale, they were told that they would watch a short clip from a recent political newscast and then be asked a series of questions based on the video. Participants were assigned to one of four treatments that varied in their level of civility. The clips were either civil or uncivil2 and came from either MSNBC’s Morning Joe or The Dylan Ratigan Show.3 Because a pilot test of the treatments suggested that the clips from the two shows were viewed similarly across key measures, the analyses in this chapter focus only on the difference between the civil and uncivil treatments and not on distinctions between those participants who saw Morning Joe and those who saw Dylan Ratigan. The use of both civil and uncivil treatments allows me to compare reactions to the two treatments at the same value of conflict orientation, as well as responses to the same treatment across different levels of conflict orientation. To encourage realism, the clips were excerpts from live cable news broadcasts, with the same two- to three-minute segment shortened to highlight either the civil or uncivil components of one conversation among the same set of commentators. The segments from both Dylan Ratigan and Morning Joe dealt with major economic debates from 2009 and 2011: the AIG bonus scandal and the budget deficit. As with any experimental treatment, the videos represent a balance between the desire for ecological validity and a realistic experience on the part of participants versus the need to control as much of the content as possible to ensure that the treatments differ only on the construct of interest (Druckman et al. 2011).

To ensure that the civil and uncivil treatments differed in incivility rather than simply the level of disagreement, I chose videos in which political elites—journalists and elected officials—disagreed about a political outcome. Substantively, the clips focus on policy and do not contain the sort of antidemocratic content that Papacharissi (2004) identifies as uncivil. Therefore, the findings reported here only compare emotional responses to incivility as captured by the tone of communication rather than the substance. Both uncivil clips contain indicators of incivility similar to those used in other experimental research (e.g., Berry and Sobeiraj 2014; Brooks and Geer 2007; Gervais 2015; Mutz 2015), including interruption, shouting, and verbal sparring (phrases like “wait a second” or “well, listen”). The uncivil clips also contain visual cues that could signal incivility. In Morning Joe, cohost Mika Brzezinski touches Joe Scarborough’s forearm as he emphatically interrupts Representative Cantor, as if to encourage him to tone down his response. In the Dylan Ratigan clip, one of the female speakers holds her hands up while fighting against an interruption, reinforcing her words, “wait a minute,” with a hand gesture that indicates the same thing. While neither gesture is uncivil in itself, both could be incorporated into an individual’s mental picture of the scene as evidence that incivility is occurring. Finally, the civil clips contain an exchange between the same journalists and political elites in which they had some disagreement but without the indicators of incivility such as name-calling or shouting.

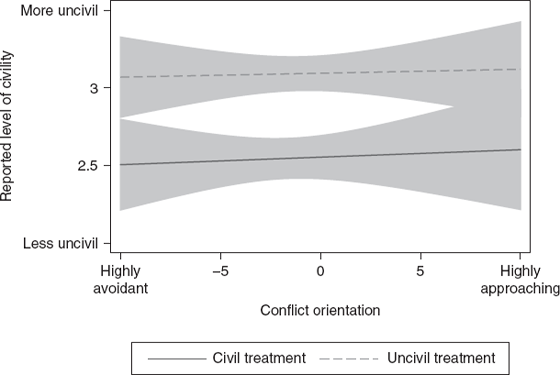

As figure 3.1 shows, participants in the survey interpreted the uncivil treatment as approximately one-half point less civil than the civil treatment, a statistically significant but perhaps not substantively significant difference ( , sd = 1.0;

, sd = 1.0;  , sd = 1.1, t = 6.6). The most conflict-avoidant and the most conflict-approaching participants perceived the civil treatment as similarly civil and the uncivil treatment as similarly uncivil. These treatments present a hard test of my theory: if only a slight difference in incivility can produce different emotional effects, it is likely that a more extreme case would produce larger variation. Furthermore, because perceptions of incivility do not vary with conflict orientation, we can be more confident that conflict orientation is directly shaping emotional reactions, rather than orientation affecting perceptions of incivility, which then influence one’s affective response.

, sd = 1.1, t = 6.6). The most conflict-avoidant and the most conflict-approaching participants perceived the civil treatment as similarly civil and the uncivil treatment as similarly uncivil. These treatments present a hard test of my theory: if only a slight difference in incivility can produce different emotional effects, it is likely that a more extreme case would produce larger variation. Furthermore, because perceptions of incivility do not vary with conflict orientation, we can be more confident that conflict orientation is directly shaping emotional reactions, rather than orientation affecting perceptions of incivility, which then influence one’s affective response.

FIGURE 3.1 Perceived civility of the MSNBC clips.

Note: Linear predictions derived from bivariate regressions of perceived civility on conflict orientation and experimental treatment. Shaded areas represent 95% confidence intervals.

Source: SSI.

INCIVILITY SPARKS EMOTIONAL RESPONSES

Before getting into the differences across conflict orientations, I looked for a general relationship between exposure to incivility and reported emotional responses. Drawing on Mutz and Reeves (2005) and Brader (2006), I expected the uncivil treatment to increase individuals’ reported experience of all emotions, positive or negative.

These relationships are borne out in the data, although the results are more pronounced for negative emotions than for positive ones. The graph on the left side of figure 3.2 shows that incivility only weakly increases individuals’ positive feelings. Participants in the incivility treatment only report a significant increase in their feelings of amusement when compared to those who watched the civil clip ( ,

,  , p < 0.041).4 This difference is relatively small: the participants in the uncivil condition reported their amusement as, on average, two-tenths of a point higher on a five-point scale than did those participants in the civil condition. A two-sample, two-tailed t-test indicates there was no significant difference in their reported entertainment (

, p < 0.041).4 This difference is relatively small: the participants in the uncivil condition reported their amusement as, on average, two-tenths of a point higher on a five-point scale than did those participants in the civil condition. A two-sample, two-tailed t-test indicates there was no significant difference in their reported entertainment ( ,

,  , p = 0.30).

, p = 0.30).

FIGURE 3.2 Average emotional responses to treatments.

Source: SSI.

The treatment has a greater effect on participants’ reported experience of negative emotions—anger, disgust, and anxiety. Participants reported statistically significantly greater feelings of each negative emotion in the uncivil condition than in the civil condition. The effects are still relatively small for anger and anxiety, an increase of between two- and three-tenths of a point (Anger :  ,

,  , p < 0.02; Anxiety :

, p < 0.02; Anxiety :  ,

,  , p < 0.041), but they are much greater for feelings of disgust. On average, participants report feeling a little disgusted after watching the civil treatment (

, p < 0.041), but they are much greater for feelings of disgust. On average, participants report feeling a little disgusted after watching the civil treatment ( ), but this average jumps half a point on the scale to 2.37, or somewhere between “a little” and “somewhat” disgusted for participants in the uncivil condition (p < 0.01).

), but this average jumps half a point on the scale to 2.37, or somewhere between “a little” and “somewhat” disgusted for participants in the uncivil condition (p < 0.01).

EFFECTS AS MODERATED BY CONFLICT ORIENTATION

Overall, these findings demonstrate that incivility elicits a range of emotional responses from citizens, both positive and negative. But the main effects of incivility on emotional response also suggest an interesting tension: incivility increases reported negative feelings like anger, disgust, and anxiety, but it also increases positive feelings of amusement. Breaking the results down across the range of conflict orientations reveals why incivility seems to produce both positive and negative emotional reactions in individuals. In comparison to civil coverage of the same issue, incivility is more likely to elicit positive emotions in more conflict-approaching individuals, but more likely to induce negative emotions in the conflict-avoidant.

Table 3.1 displays the results of five OLS regression models that investigated the relationship between each emotional response, conflict orientation, the treatment condition, and a variety of demographic and political characteristics. Looking first at the negative emotions—anxiety, anger, and disgust—I expected that exposure to incivility would increase feelings of all three among the conflict-avoidant and that partisanship would also play a role in evoking anger. When I compare the findings from the civil and uncivil treatments across the range of conflict orientations, it is clear that individuals who are more conflict-avoidant experience greater negative emotional reactions to incivility than they do to a civil discussion of the same issue. As table 3.1 shows, a similar pattern emerges in individuals’ self-reported feelings of anxiety, disgust, and anger in response to civility and incivility. Individuals who are more conflict-avoidant report greater negative emotional reactions to the uncivil clip than they do to the civil clip. However, this difference disappears when we look at individuals who are more conflict-approaching.

TABLE 3.1 THE INTERACTION BETWEEN CONFLICT ORIENTATION AND INCIVILITY INFLUENCES EMOTIONAL RESPONSES

| |

ANXIOUS |

DISGUSTED |

ANGRY |

AMUSED |

ENTERTAINED |

| Conflict orientation |

−0.0080 |

0.022 |

0.0087 |

0.037* |

0.014 |

| |

(0.0144) |

(0.016) |

(0.015) |

(0.015) |

(0.015) |

| Uncivil treatment |

0.26** |

0.41** |

0.15 |

0.28** |

0.21* |

| |

(0.094) |

(0.107) |

(0.097) |

(0.098) |

(0.099) |

| C.O. x Treatment |

−0.031 |

−0.059* |

−0.030 |

0.031 |

0.050* |

| |

(0.021) |

(0.024) |

(0.022) |

(0.022) |

(0.022) |

| Political knowledge |

−0.099** |

−0.041 |

−0.074* |

−0.16** |

−0.17** |

| |

(0.036) |

(0.041) |

(0.037) |

(0.373) |

(0.038) |

| Democrat |

−0.14 |

−0.26 |

−0.17 |

0.039 |

0.029 |

| |

(0.122) |

(0.136) |

(0.124) |

(0.125) |

(0.126) |

| Independent |

−0.19 |

−0.099 |

−0.21 |

0.049 |

−0.072 |

| |

(0.141) |

(0.159) |

(0.144) |

(0.145) |

(0.147) |

| Strong partisan |

0.12 |

0.12 |

−0.011 |

0.26* |

0.27* |

| |

(0.111) |

(0.125) |

(0.113) |

(0.114) |

(0.115) |

| Female |

−0.22* |

−0.15 |

−0.24* |

−0.20* |

−0.14 |

| |

(0.092) |

(0.104) |

(0.094) |

(0.095) |

(0.097) |

| Constant |

−0.22** |

2.21** |

2.28** |

2.35** |

2.60** |

| |

(0.092) |

(0.187) |

(0.170) |

(0.17) |

(0.174) |

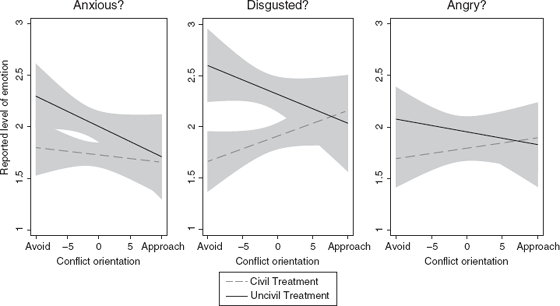

Figure 3.3 displays these regression results graphically. Feelings of disgust among the conflict-avoidant are most influenced by the presence of incivility, with the highly conflict-avoidant (those who score a −10 on the Conflict Communication Scale) reporting average feelings of disgust at around 2.6 on the 5-point scale when shown the uncivil video clip. This translates to feeling somewhere between “slightly” and “moderately” disgusted. Those conflict-avoidant individuals who viewed the civil clip reported feelings of disgust that averaged around 1.6, a full point lower than those who viewed incivility, somewhere between “not at all” and “slightly” disgusted. The gap between those who viewed the uncivil clip and those in the civil condition declines as conflict orientation moves toward greater conflict-approaching tendencies, becoming statistically indistinguishable around the conflict-ambivalent zero point.

FIGURE 3.3 Conflict-avoidant individuals experience more negative emotions in response to incivility.

Note: Linear predictions are from an OLS regression of emotion and the interaction between conflict orientation and experimental treatment, controlling for demographic and political variables. Each emotion was measured on a 1 to 5 scale, with 1 indicating a respondent experienced a given emotion “not at all” and 5 indicating “extremely.”

Source: SSI.

Incivility also has a greater effect on individuals’ reported feelings of anxiety if they are highly conflict-avoidant. The gap between average reported anxiety for the highly conflict-avoidant in civil and uncivil treatments is about half a point on the five-point scale, with those who watched the uncivil video clip reporting more anxiety than those in the civil treatment. The difference between the treatments at the highest levels of conflict avoidance is not statistically significant, but this is likely due to the relatively small set of participants who score the highest and lowest values of the CCS. The difference is clear for those participants who are slightly conflict-avoidant (those who scored between −7 and zero), and the gap between reported feelings of anxiety for these individuals is between a quarter and a third of a point. As with reported feelings of disgust, the difference between the civil and uncivil treatments disappears for those participants who are conflict-approaching. The responses for reported feelings of anger also follow this pattern, although these differences are not statistically significant. The conflict-approaching do not experience any greater feelings of anger, anxiety, or disgust when viewing an uncivil video clip than when viewing a civil clip. However, the conflict-avoidant report feeling more anxious and disgusted when they watch uncivil coverage of politics than when they watch a civil discussion of the same issue, thereby offering support for the anxiety, disgust, and anger hypotheses. There was no support for the partisan-anger hypothesis. Neither partisanship nor the strength of party identity had a statistically significant effect on participants’ report of negative emotional reactions.

The pattern for the experience of positive emotions mirrors that for negative emotions. Looking at figure 3.4, we see that the conflict-approaching are more likely to report feeling amused or entertained when watching an uncivil clip than when exposed to the civil treatment. However, more conflict-avoidant individuals report feeling no more positive when watching the uncivil video than when watching the civil one. The effects for both amusement and entertainment are relatively similar, with highly conflict-approaching participants in the uncivil condition reporting levels of both reactions that are about three-quarters of a point higher than those in the civil condition. In other words, the most conflict-approaching people found the uncivil clip to be moderately amusing or entertaining, while they found the civil clip to be only slightly amusing or entertaining. Those who identified as more conflict-avoidant reported no difference in their feelings of amusement and entertainment when watching the uncivil or civil video clips.

FIGURE 3.4 Conflict-approaching individuals experience positive emotional reactions to incivility.

Note: Linear predictions are from an OLS regression of emotion and the interaction between conflict orientation and experimental treatment, controlling for demographic and political variables. Each emotion was measured on a 1 to 5 scale, with 1 indicating a respondent experienced a given emotion “not at all” and 5 indicating “extremely.”

Source: SSI.

To summarize, the SSI study results suggest that conflict orientation and incivility interact to produce different emotional responses in the conflict-avoidant and conflict-approaching. Participants who are more conflict-avoidant are more likely to report negative emotions such as disgust and anxiety when shown an uncivil news clip than when shown a civil portrayal of the same information. Conversely, more conflict-approaching people report greater amusement and entertainment when watching an uncivil clip than a civil one. These findings hold even when controlling for other facets of individuals’ political lives, including their partisanship, political interest and knowledge, and demographic characteristics such as gender. While these demographic and social characteristics do have an impact on individuals’ emotional responses above and beyond the treatments, incivility and conflict orientation continue to play a significant role in emotional response, particularly in evoking disgust and entertainment.

BEYOND POLITICAL INCIVILITY

The SSI study demonstrates that political incivility elicits different emotional reactions based on our conflict orientations. But these results raise a second question: Can we be conflict-avoidant when it comes to politics, but conflict-approaching in our professional lives? If our conflict orientation is specific to politics, then we would not have the same reactions to political incivility as we would to other types of incivility.

The GfK study was designed in part to test the extent to which conflict orientation shapes our responses to incivility in the mediated world more generally The 3,101 participants recruited for this study completed a four-question version of the Conflict Communication Scale5 and were randomly assigned to one of four 45-second clips that varied in the presence of civility or incivility and their substantive content. One set was political in nature, featuring CSPAN coverage of congressional hearings on Planned Parenthood. The second set of clips was entertainment-based and centered on two judges’ evaluations of food prepared by a contestant on the reality cooking show Master Chef. Each of the clips was pretested by a different online convenience sample and selected to maximize differences in perceived civility between the civil and uncivil clips while minimizing differences across the substantive topics.

The Planned Parenthood clips showed an exchange between members of the Congressional Oversight and Government Reform committee and Planned Parenthood president Cecile Richards. In the civil condition, Representative Elijah Cummings (D-Md.) argues in a reasoned, calm tone that the rule of law must be followed even if he or others wish that it said something else. The uncivil clip depicts an exchange between Richards and Representative Jim Jordan (R-Ohio). Jordan frequently interrupts Richards, raises his voice, holds his finger up as if he’s pointing or telling her to wait a minute, and ultimately accuses her of avoiding his questions. Using a 5-point scale on which 1 signified the clip was not at all civil and 5 indicated extreme civility, participants saw a statistically significant difference in the civility of the two clips ( , sd = 1.3;

, sd = 1.3;  , sd = 0.90, p(two – tailed) < 0.01).

, sd = 0.90, p(two – tailed) < 0.01).

In the Master Chef clips, a male contestant’s pasta dish is being judged. In the civil condition, a female judge is critical of the food but keeps an even tone and does not malign or otherwise insult the contestant. The uncivil condition presents an assessment of the same meal by a second, male judge. This judge is also critical, but he criticizes in a way that belittles the contestant, pointing to his “cavalier” and “oh poor me again, I screwed up” attitude. He continues: “You want to show us how cutesy and intelligent and crafty you are. Well that’s going to get you a one-way ticket back to where you came from. And then you can show your friends and the six people who told you you were good how cutesy and smart you are while you’re at home cooking at dinner parties” (“Joe vs Howard Pasta Challenge” 2013). As with the Planned Parenthood clips, the Master Chef clips were perceived as significantly different from one another ( , sd = 1.20;

, sd = 1.20;  , sd = 0.89, p(two – tailed) < 0.01).

, sd = 0.89, p(two – tailed) < 0.01).

Before moving into the relationships between conflict orientation, incivility, and emotional responses to these new clips, I offer a brief characterization of the participants and treatments. The average participant was slightly conflict-avoidant ( , sd = 2.95). There was a statistically significant difference between the perceived civility of the civil and uncivil clips, as well as between the coverage of the two topics. Specifically, the civil Planned Parenthood clip was found to be almost half a point more civil than that from Master Chef (

, sd = 2.95). There was a statistically significant difference between the perceived civility of the civil and uncivil clips, as well as between the coverage of the two topics. Specifically, the civil Planned Parenthood clip was found to be almost half a point more civil than that from Master Chef ( , sd = 1.31;

, sd = 1.31;  , sd = 1.20, respectively) on a 5-point scale where 5 signified extreme civility. The difference between the two uncivil clips was smaller and statistically insignificant (

, sd = 1.20, respectively) on a 5-point scale where 5 signified extreme civility. The difference between the two uncivil clips was smaller and statistically insignificant ( , sd = 0.90;

, sd = 0.90;  , sd = 0.89).

, sd = 0.89).

As in the previous experiment, participants’ experience of discrete emotions was self-reported on a 5-point scale where 1 demonstrated that a participant did not feel a particular emotion at all and 5 indicated extreme emotion. For the most part, the uncivil treatments produced more emotional responses, particularly negative ones, than the civil treatments.

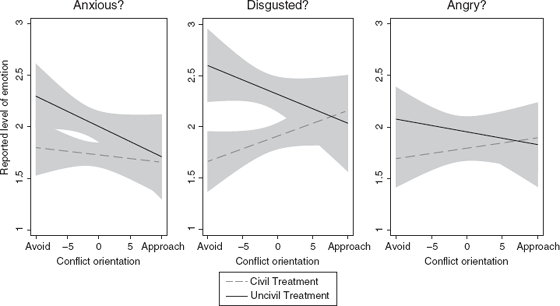

An OLS regression of each emotion on the interaction between conflict orientation and incivility, holding constant partisanship, ideology, gender, education, and race, displays patterns similar to those seen in the SSI study. Figure 3.5 graphically depicts these results.6 For the Master Chef clip, there is no significant difference in the reported anger, disgust, or anxiety of the highly conflict-approaching. However, the most conflict-avoidant individuals were likely to report substantially more anger, disgust, and anxiety after watching the uncivil clip than the civil one. The uncivil Planned Parenthood clip produced a strong direct effect but weaker interactive effects on anger and disgust. Regardless of conflict orientation, the uncivil clip elicited greater disgust and anger on the part of participants. However, the interactive pattern for anxiety matches that found in the SSI study and with the Master Chef clips. The conflict-avoidant reported greater feelings of anxiety—almost a point higher on the scale—when shown the uncivil clip, whereas there is no difference in the emotion evoked by the two clips in the conflict-approaching. Once again, there is support for the anxiety, disgust, and anger hypotheses. Party identification fails to obtain statistical significance, so once again there is no support for the partisan-anger hypothesis.

FIGURE 3.5 GfK study also demonstrates conflict-avoidant have negative reactions to incivility.

Note: Linear predictions are from an OLS regression of emotion and the interaction between conflict orientation and experimental treatment, controlling for demographic and political variables. Each emotion was measured on a 0 to 4 scale, with 0 indicating a respondent experienced a given emotion “not at all” and 4 indicating “extremely.”

Source: GfK.

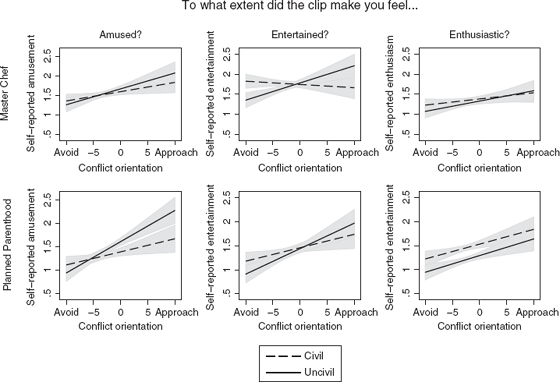

As in the SSI study, incivility and conflict orientation produce weaker effects on positive emotional responses (see figure 3.6). Both conflict orientation and incivility produce statistically significant direct effects for the Planned Parenthood and Master Chef videos; however, the interaction between the two is only statistically significant for amusement in the Planned Parenthood condition. While the remaining interactions fail to achieve statistical significance, they do follow a similar pattern to that found in the SSI sample. Therefore, there is at least some support for the amusement and entertainment hypotheses, as well as an indication that conflict orientation and the presence of incivility can evoke enthusiasm in participants, thereby substantiating the enthusiasm hypothesis.

FIGURE 3.6 Incivility evokes positive emotions among GfK participants.

Note: Linear predictions are from an OLS regression of emotion and the interaction between conflict orientation and experimental treatment, controlling for demographic and political variables. Each emotion was measured on a 0 to 4 scale, with 0 indicating a respondent experienced a given emotion “not at all” and 4 indicating “extremely.”

Source: GfK.

***

Current research on incivility emphasizes its dual nature: on one hand, it decreases trust in government and perceptions of legitimacy; on the other, it increases participation. This book offers one reason for these contrasting outcomes: incivility affects people differently because people respond to conflict in different ways.

Specifically, the studies described in this chapter demonstrate that people who do not enjoy conflict—the conflict-avoidant—will experience greater negative emotions when exposed to incivility than when asked to watch a civil video clip. Alternatively, the conflict-approaching will report stronger positive emotions in the face of incivility. These patterns hold up across different samples and using different video clips on both political and entertainment topics.

The fact that conflict orientation and incivility interact to provoke different emotional responses has implications for a range of political behaviors and decisions. Much of the evidence suggests that emotion has a positive effect on political participation (Marcus et al. 2000). Research by Brader (2006) suggests that anxiety propels people to seek more information, while enthusiasm stimulates the desire to vote. This increased engagement in the political sphere is typically seen as normatively positive, but it raises concerns about the quality of citizens’ engagement. Conflict-approaching individuals are being drawn into politics, but not in a way that facilitates reasoned, respectful conversations about the issues. Previous research (Anderson et al. 2013; Stroud et al. 2015) demonstrates that preventing anonymous postings and moderating comment forums can reduce uncivil comments, but this does not explain why individuals are driven to make uncivil comments in the first place, nor does it explain why they are willing to use their Facebook accounts to do so. My research suggests that the presence of incivility in the media, coupled with greater engagement by people who are comfortable with conflict, could increase the likelihood that discourse will become uncivil.

While there is a clear relationship between conflict orientation, exposure to incivility, and affective responses, the impact of that relationship on behavioral outcomes is less clear. If incivility makes the conflict-avoidant anxious, are they looking for more information about politics, and if so, how and where are they doing so? The greatest effects were in eliciting disgust reactions, which have been shown to lead to avoidance behaviors (Neuberg, Kenrick, and Schaller 2011; Rozin et al. 2008). Are most of the conflict-avoidant deciding to simply avoid politics instead? Or, because anger motivates political action, could we see the conflict-avoidant become more engaged in political activity? Positive emotions like enthusiasm also encourage engagement, so it is possible that the conflict-approaching are also more likely to participate in certain types of political activity. In the next two chapters, I investigate how conflict orientation and political incivility interact to influence political engagement.

, sd = 1.0;

, sd = 1.0;  , sd = 1.1, t = 6.6). The most conflict-avoidant and the most conflict-approaching participants perceived the civil treatment as similarly civil and the uncivil treatment as similarly uncivil. These treatments present a hard test of my theory: if only a slight difference in incivility can produce different emotional effects, it is likely that a more extreme case would produce larger variation. Furthermore, because perceptions of incivility do not vary with conflict orientation, we can be more confident that conflict orientation is directly shaping emotional reactions, rather than orientation affecting perceptions of incivility, which then influence one’s affective response.

, sd = 1.1, t = 6.6). The most conflict-avoidant and the most conflict-approaching participants perceived the civil treatment as similarly civil and the uncivil treatment as similarly uncivil. These treatments present a hard test of my theory: if only a slight difference in incivility can produce different emotional effects, it is likely that a more extreme case would produce larger variation. Furthermore, because perceptions of incivility do not vary with conflict orientation, we can be more confident that conflict orientation is directly shaping emotional reactions, rather than orientation affecting perceptions of incivility, which then influence one’s affective response.

,

,  , p < 0.041).

, p < 0.041). ,

,  , p = 0.30).

, p = 0.30).

,

,  , p < 0.02; Anxiety :

, p < 0.02; Anxiety :  ,

,  , p < 0.041), but they are much greater for feelings of disgust. On average, participants report feeling a little disgusted after watching the civil treatment (

, p < 0.041), but they are much greater for feelings of disgust. On average, participants report feeling a little disgusted after watching the civil treatment ( ), but this average jumps half a point on the scale to 2.37, or somewhere between “a little” and “somewhat” disgusted for participants in the uncivil condition (p < 0.01).

), but this average jumps half a point on the scale to 2.37, or somewhere between “a little” and “somewhat” disgusted for participants in the uncivil condition (p < 0.01).

, sd = 1.3;

, sd = 1.3;  , sd = 0.90, p(two – tailed) < 0.01).

, sd = 0.90, p(two – tailed) < 0.01). , sd = 1.20;

, sd = 1.20;  , sd = 0.89, p(two – tailed) < 0.01).

, sd = 0.89, p(two – tailed) < 0.01). , sd = 2.95). There was a statistically significant difference between the perceived civility of the civil and uncivil clips, as well as between the coverage of the two topics. Specifically, the civil Planned Parenthood clip was found to be almost half a point more civil than that from Master Chef (

, sd = 2.95). There was a statistically significant difference between the perceived civility of the civil and uncivil clips, as well as between the coverage of the two topics. Specifically, the civil Planned Parenthood clip was found to be almost half a point more civil than that from Master Chef ( , sd = 1.31;

, sd = 1.31;  , sd = 1.20, respectively) on a 5-point scale where 5 signified extreme civility. The difference between the two uncivil clips was smaller and statistically insignificant (

, sd = 1.20, respectively) on a 5-point scale where 5 signified extreme civility. The difference between the two uncivil clips was smaller and statistically insignificant ( , sd = 0.90;

, sd = 0.90;  , sd = 0.89).

, sd = 0.89).