Part One was devoted to Bruegel’s “outer” worlds—to nature (landscapes, the sea and ships) and to men and women (his countrymen and contemporaries). Now, in Part Two, we enter his “inner” worlds, the realms of imagination. The fanciful takes precedence over the actual; the fantastic submerges the realistic; the symbol transforms the report.

All formal arrangements and selections from a great artist’s work are likely to be misleading—including this one. Life and art do not lend themselves neatly to arbitrary outlines. (And strictly chronological presentations are often the most misleading of all, even when définitive dates can be established throughout.) The arrangement of prints in this book, however, does permit a certain pausing from time to time to survey what we have seen and what yet awaits.

Thus we find that in the three sections immediately following, the artist is concerned with human conduct. His aim, overt or covert, is normative. His graphic comments—caustic, comical, ribald, or grave—imply the need to alter what is, and “remold it nearer to the heart’s desire.” The posture of the approach may be a sneer, a shrug, or a loud laugh. Sometimes a cry of despair seems to re-echo distantly.

The three-way division of the title of this section (Drolleries, Didactics, and Allegories) should not be taken too seriously. The compartmentalization cannot be watertight. This is no Teutonic super-systematization behind a façade of “scholarship.” Bruegel’s art is as intolerant of categorical fences as is that of Shakespeare. And the Bruegel of the following engravings, one can imagine, might have relished the parody of subdivisions like those Shakespeare put into the mouth of his pundit, Polonius: “The best actors in the world, either for tragedy, comedy, history, pastoral, pastoral-comical, historical-pastoral, tragical-historical, tragical-comical-historical-pastoral. . . .”

Among the following prints, “The Peddler Pillaged by Apes” is more or less unmitigated drollery; hence “comical.” “The Triumph of Time” is almost all allegorical. The others intermingle in varying proportions all three aspects. A Polonius of art history would have to set them down therefore as “allegorical-didactical-comical.”

How essential is the comical?

“Authorities” during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, when they devoted attention to Bruegel the Elder at all, did so usually in terms which implied that his dominant quality was a peasant-like drollery, a heavy-handed rustic comedy, coarse and racy, unfit for sensitive souls.

This distortion persisted well into the current century. Thus, one reads in Buxton and Poynton’s German, Flemish and Dutch Painting (London, 1905) concerning “Peasant” Bruegel: “There is a coarse humor about his pictures which, if vulgar, is better than the insipid. ...” Etc., etc. However, according to the same source, the following generation did better, for that elegant and elaborate but rather empty technician, Jan (“Velvet”) Breughel is rated as “decidedly superior to his father.”

The Encyclopaedia Britannica, 14th edition (1929), illustrated a similar cultural lag. This is part of the short entry headed “Breughel or Brueghel”: “The subjects of his pictures are chiefly humorous figures like those of D. Teniers; and if he lacks the delicate touch and silvery clearness of that master, he has abundant spirit and comic power.”

This was all a long-lasting rehash of the generalization, written about a generation after Bruegel’s death, by Carel van Mander: “You cannot but laugh at the droll figures that he painted.” Mander, as we know now, was far from complete and not always entirely accurate in what he had to tell about Bruegel the Elder.

With regard to the “droll figures,” Adriaan Barnouw writes: “I, for one, find it difficult to laugh at his drolleries ... all the human wreckage of a time that was out of joint were rendered by him with poignant realism. The pain and the pity that stirred within him . . . found expression in the beauty of their portrayal.”

“Didactic,” too, deserves comment. The term is applicable here in the same sense as that in which the aim of didactic poetry is said to be “less to excite the hearer by passion or move him by pathos than to instruct his mind and improve his morals.”

The “instruction” aspect is not important; Bruegel did not seek to impart information as such. He was aiming at improvement of human understanding, attitude, outlook. And these improvements are moral.

Bruegel’s art held up a mirror to a topsy-turvy world. He portrayed crazy and perverse situations. See, as one instance, “The Witch of Malleghem.” In the extreme view of Tolnay, Bruegel believed the world of men to be, in fact, hopeless, incapable of betterment. Things were as they had to be, because men were what they were and would always be. How, then, could he accomplish a didactic end? Where improvement is out of the question, how can there be effective moral teaching?

A more balanced and adequate interpretation of Bruegel’s personal attitude is suggested in the comments which follow—especially those for the engravings in the series of Sins and Virtues. That interpretation is, it seems to this writer, closer to Barnouw than to Tolnay.

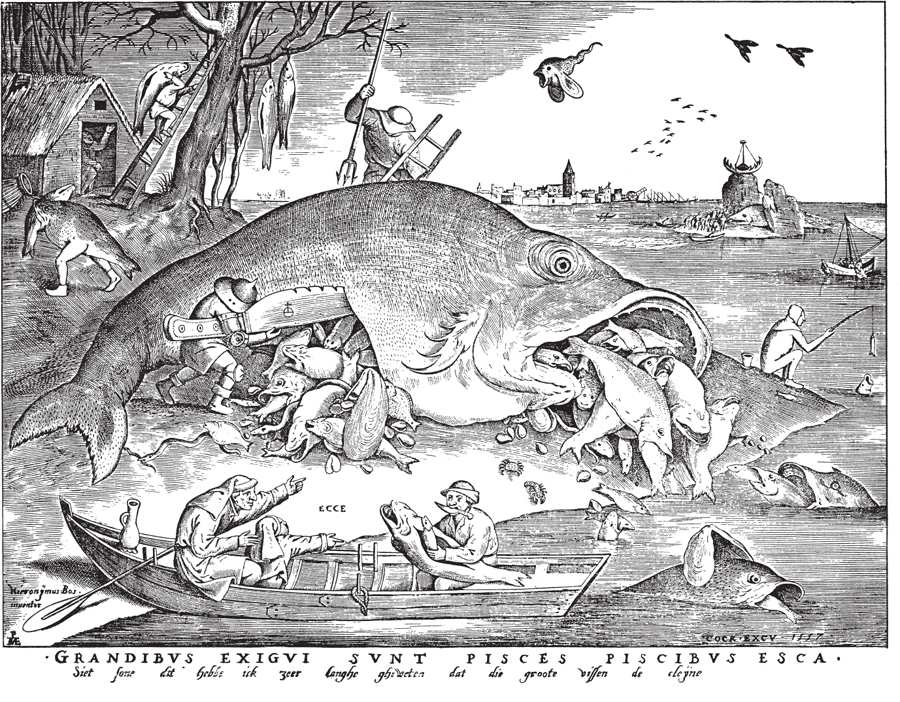

Our chronology of Bruegel’s creative life, previously given in this book, shows that when the artist made his “abrupt” addition of satirical and moralistic subjects to his landscapes, he started not with the semi-theological series of Sins but with the folksy and proverbial drolleries of “Big Fish Eat Little Fish” and “The Ass at School.” These two, as well as other engravings later in this section, are essential to the pictorial message which Bruegel penned to his audience of fellow countrymen, his contemporaries in trying times.

The engraver for this striking and increasingly famous print was van der Heyden, in 1557. The original, a pen drawing in gray ink, in the Albertina Museum, Vienna, is dated 1556 and signed “brueghel.”

The engraving bears, at lower left, just above the oar blade, the signature “Hieronymus Bos. inventor.” This poses a problem not completely solved even now, though scholars generally agree that this is a forgery or misrepresentation, at least in the sense that the immediate model followed by the engraver was Bruegel’s drawing to which the engraving conforms completely.

Jerome Cock was the publisher, as indicated by the credit at lower right “Cock excu. 1557.” Opinion is divided chiefly as to whether (a) Cock put the name of Bosch on the engraving hoping thus to increase its sales—the earlier artist presumably being more sought after than the contemporary—or (b) whether Bruegel’s drawing was, in fact, a recasting or “restoration” of an earlier drawing by Bosch, who was thus in a sense being given his just due. In either case, this engraving is authentically “after Bruegel.”

The Latin word “Ecce,” meaning “Behold!” or “See there!,” seen just above the rowboat, is not part of the original drawing. The engraving is, of course, a mirror image of the drawing.

The engraving was published with the motto it illustrates printed below in both Latin and Flemish. The basic proverb is “Big fish eat small.” The Flemish version is given somewhat more elaborately. In terms of a modern comic strip it would be seen as a “balloon” coming from the mouth of the older man who points at the object lesson. He says, freely rendered: “See, my son, I have known this for a very long time—that the large gobble up the small.”

The spectacle on the shore illustrates abundantly this maxim of worldly wisdom. A peculiarly Bruegelian figure, all helmet and body, cuts open the belly of the beached monster. Out pours a tangled flood of fish, mussels, and eels, still whole, many themselves in the act of swallowing others. The same violent and cynical situation is repeated at the creature’s mouth where a dozen or more fish can be distinguished.

Another faceless hat-man, atop a ladder, is about to plunge his trident into the monster’s back.

The huge notch-bladed knife wielded by the helmeted figure has on its blade what seems to be a maker’s trade-mark, but actually is the symbol for the world—the wicked, foolish, dog-eat-dog and fish-eat-fish world. The helmeted figure has been nicely termed a “storm trooper” by Adriaan Barnouw.

In the water to the right of the boat, a giant mussel gets a grip on a large fish which is swallowing a smaller. Higher and to the right, in the three-way play, fish No. 1 swallows No. 2, who is swallowing No. 3.

Above, on the bank, sits the fool of the world who dangles one fish to catch another. Beyond, in the water, a typical fishing vessel pulls its nets.

On a distant island is stranded a huge fish or whale wedged between rocks. A crowd of men approach, probably to kill, cut, and devour. Atop the towering rock rests a peculiar structure, possibly the wreck of a boat, more likely an ornament, but definitely reminiscent of certain cryptic, elaborately “Oriental” constructions pictured in paintings by Bosch, as well as in the later Sins prints of Bruegel.

In the far background, at the horizon, lies one of Bruegel’s typical towns with harbor. Five or six galleys (oars plus sails) are anchored there. “Normal” birds fly in the sky—two nearer, and over a dozen more distant. The dominant creature in the sky, however, is a tri-phibious monster: part fish, part snake, part bird or insect. Its mouth gapes for prey.

Another monster—suggestive of the shape of things to come in later drawings—climbs the bank at left: a fish with man’s legs, its mouth gorged with a fish.

On the tree above, two fish are hung, their bellies slit open. A man climbs a ladder to hang up a third.

Many subsidiary Flemish folksays and proverbs have been traced in this print. Among them: “Little fish lure the big”; “One fish is caught by means of another”; “Fish are hooked through fish”; “They hang by their own gills” (like the fish in the tree—i.e., they are caught by their own weakness or vulnerability).

About half a century after Bruegel drew the original of this engraving, an Englishman—a playwright—wrote some pungent dialogue relevant to this picture’s theme. (From Pericles, Prince of Tyre by William Shakespeare, Act II, Scene 1.)

Third Fisherman: ... Master, I marvel how the fishes live in the sea.

First Fisherman: Why, as men do a-land: the great ones eat up the little ones. I can compare our rich misers to nothing so fitly as to a whale: a’ plays and tumbles, drivirig the poor fry before him, and at last devours them all at a mouthful. Such whales I have heard on o’ the land who never leave gaping till they’ve swallowed the whole parish, church, steeple, bells, and all.

Pericles (aside): A pretty moral . . .

. . . How from the finny subject of the sea

These fishers tell the infirmities of men . . .

Adriaan Barnouw writes regarding the didactic content and connotations of this print: “Marine life is graded mass murder . . . and a counterpart of man’s inhumanity to man. . . . The underfish of our day are still at the mercy of the big gluttons, but they are preyed on with a subtler . . . voracity. Big nations gobble up little ones ... big corporations, holding companies, chains, department stores swallow up the little fellow for the general public’s and the little fellows’ own good.”

In summary we may say that seen as a whole this engraving expresses important aspects of Bruegel the graphic artist in his “new” fantastic-didactic style. We see the exuberant abundance of action and incident, the seven-ringed circus effects, the simultaneous variations on a given theme (often cryptic, seldom dull). This Bruegel is an abundant, repetitive, and extensive artist, an analogue in line to such outpouring geniuses as Rabelais and Shakespeare in literature. Yes, and even to the Melville of Moby Dick, to Mark Twain, and to Thomas Wolfe (prior to editorial pruning).

This plate was engraved in 1557 by van der Heyden, whose monogram does not appear on the plate, and published by Cock, with credit at lower left to “Bruegel. Inventor.”

The original, a pen drawing in brownish black ink in the Kupferstichkabinett, Berlin, bears date and signature, spelled “brueghel. 1556.” Below the drawing, a hand not Bruegel’s printed the rhymed Flemish lines which in the engraving are reproduced below the Latin lines. They may be translated freely this way:

Though a donkey go to school in order to learn,

He’ll be donkey, not a horse, when he does return.

This practical psychology is akin to our proverbs: “You can’t make a silk purse from a sow’s ear!” or “Once an ass, always an ass!” Or, to coin a mixed maxim: “A fool and his folly are not soon parted! “

The donkey looking in learnedly at the left has been given “all the advantages “—eyeglasses to read with, notes to sing by, a candle to cast light on his studies. But when he essays to sing, he’ll bray the same old way. . . . Hee-haw!

Through the grating at upper center, somebody is looking in at this most unprogressive educational institution.

The “children” are quite obviously grown-ups, foolish, fantastic, bewildered. The sober schoolmaster (Old Man Experience, perhaps?) is in the act of administering corporal punishment to the bared backside of a scholar. A bundle of twigs is in his hat like an ornament. He may apply them too, but probably in vain.

Dozens of the perverse and not-to-be-helped “schoolchildren” clutter up the room. They study a-b-c’s, in crazy postures and combinations.

Below the window, two of them are huddled under a large hat pressed down on them by a sly fellow who peers around the corner. A peacock’s feather flaunts from the hat band. This, Adriaan Barnouw points out, relates to different Flemish sayings: “Two fools under a single hood” and “Easily caught under a hat” (characteristic of a gullible fool). The peacock feather, he points out, was held among Latin scholars to symbolize cowardice because of similarity in sound between paveo (I am afraid) and pavo (peacock).

Many other proverbs and sayings, some long lost, are certainly suggested elsewhere here.

One scholar celebrates his new learning by sticking his head into a beehive (right). Two little monks seem to dispute as they pore over tomes. A woman keeps herself and books in a basket. Near “teacher” there are grimacers and weird contortionists. One balances a basket on his head. At least half a dozen figures show the Bruegel “trade-mark”—that is, no face is visible under the hat or headcovering.

The atmosphere of semi-imbecility is unmistakable.

And neither the bundle of twigs in teacher’s hat, nor a spare switch in the pot at the right, is likely to alter matters much.

Translation of Latin caption: You may send a stupid ass to Paris: if he is an ass here, he won’t be a horse there.

Another engraving by van der Heyden, assigned to 1567 by Tolnay, though more recently another scholar, F. Würtenberger, has dated it nine years earlier. As indicated by the credit “Aux quatre Vents,” it was published by Cock. No original drawing survives.

Perhaps a better title might be “The Battle of the Piggy-Banks and the Treasure Chests.” After all, the warriors at left are pottery, not bags.

It has been called by Ebria Feinblatt, “a satire on the forces of war and plunder . . . one of the least complicated subjects by Bruegel to read.”

The basic theme is reminiscent of the title of Brailsford’s book: The War of Steel and Gold. Here, wealth fights wealth, in a mad, dehumanized mêlée. Mammon and murder, now and forever, one and inseparable.

In the words of Dr. Barnouw: “All wars are engendered by greed. It is not the poor who make war but the rich who want to rob each other. . . . Strong boxes and barrels filled . . . with gold ducats. . . . Those are the forces that clash on each battlefield.”

Below the engraving are three couplets in Latin and three in Flemish, the latter supplying a rhymed text. Freely translated, the Flemish runs:

Have at it, you chests, pots, and fat piggy-banks!—

All for gold and for goods you are fighting in ranks.

If any say different, they are not speaking true—

That’s why we’re resisting the way that we do. . . .

They’re seeking for ways now to drag us all under;

But there’d be no such wars, were there nothing to plunder!

Pear-shaped pottery “banks” like these were quite common in Bruegel’s time. Coins were inserted through a slot near the top, visible as a dark diagonal slash on some in this engraving. Accumulated wealth was removed by breaking the bank. Near the top, left of center, we see a flag-flying giant piggy-bank that has broken open and is giving birth to a column of smaller bank-warriors who march straight into battle.

Human heads project from some of the animated money-barrels and pots. But others, more consistently dehumanized, have only man-like arms and legs. In the foreground, right, an arm lies severed from the pierced strong-box nearby. The hand still clutches its sword. The money-containers die hard!

In that corner, a watchdog chained to a money-barrel barks frantically. Meanwhile, a foot soldier—face hidden again—extracts coins through the barrel staves. This figure reminds one of some in Diego Rivera’s memorable murals of Mexican history.

The entire coin-bespattered carnage is a wild tangle of weapons, warriors, and weird violence. Weapons of various periods are represented: cannon and cannonballs; lances, spears, swords, daggers, cutlasses, maces, battle-axes, and pikes. In the lower left corner a soldier has a short kitchen-type knife embedded through his helmet and brain-pan.

No weapon is too murderous, no aggression too brutal for this “striden en twisten”—Flemish for fighting and quarreling.

Money is on the march! Make way for plunder!

Translation of Latin caption: What riches are, what is a vast heap of yellow metal, a strong-box filled with new coins, among such enticements and ranks of thieves, the fierce hook will indicate to all. Booty makes the thief, ardent zeal serves up every evil, and a pillage suitable for fierce spoils.

The names above, in English, Flemish, and French could be matched by others in other tongues. For example, the German Schlaraffenland, the American “Big Rock Candy Mountain,” etc. Everywhere the concept is the same—the Never-Never-Land of dolce far niente, where roast fowl flies unaided into one’s mouth; and milk and honey, or one’s favorite cocktail, flow endlessly for the asking.

The original of this 1567 engraving by van der Heyden is the fine painting by Bruegel in the Pinakothek Museum, Munich. It is signed and dated “1567. Bruegel.” (This same painting was mentioned in a 1621 inventory of the imperial art collection in Prague.)

In the engraving a four-line Flemish verse at the bottom issues an ironical invitation to peasant, soldier, or clerk (scholar) to “go native” in this lazy man’s dream of Luilekkerland. Freely translated it runs like this:

All you loafers and gluttons who love to be lying:

Farmer, Soldier, or Clerk—you can live minus trying.

Here the fences are sausage, the houses are cake,

And the fowl fly ‘round roasted, all ready to take!

The three “callings” mentioned in the verse are all here, lying in useless slumber under a table-tree. At the left, the scholar, mouth open not for eloquence but in snoring. Next, the peasant flat on his flail. Finally, the soldier, his lance on the grass, his gauntlet cast down, his helmet farther right. All three are literally “good for nothing.”

Between the first two scampers an egg, already opened and eaten. Empty eggshells are with Bruegel, as with Bosch, symbolic of spiritual emptiness and sterility.

At left, a cactus-like plant is actually made up of cakes—and no spines! Further right, a roast pig, already partly carved, trots along, a knife handily stuck through a loop of skin.

To the right again, a roast goose lays itself down in readiness on a silver platter. A fine linen napkin or cloth is already spread below.

Above the pig, in the background, we see a man who is “making it the easy way” according to the Dutch tradition. He has just eaten his way clear through the rice pudding mountains which form the barrier to Lazy-delectable-land (Luilekkerland). He cushions his fall by grasping the branch of a tree which grows partly through the pudding.

The fence on the far side of the sleepers’ lawn is a woven web of sausages. At the right is a house or lean-to, its roof covered with pies and cakes. Under this protection an open-mouthed figure is awaiting a roast chicken which is flying in “right on the beam.” Dr. Barnouw has identified the figure as a farmer’s wife; however, it seems to be rather a helmeted knight, his visor lifted, his arms propped comfortably on a brocaded pillow.

The rice pudding mountains plunge precipitously down to a sea (of beer, perhaps?) on which a rowboat and fishing boats are seen. At the horizon, just as might be expected, is a substantial city.

Pieter van der Heyden engraved this bit of drollery. It is his monogram which is seen at the lower right under the small drum. The engraving was first published by Cock, 1562. Bruegel’s original has dropped out of sight.

Four states of the plate are recorded, indicating the continuing popularity of the subject. The first lacks Bruegel’s name at the left, but has Cock’s name in the centre. The second adds in the small panel at the lower left, the words “Brueghel lnvē.” The third shows below those words the legend “T.G. excudit,” indicating Theodore Galle as publisher; this state lacks the center credit to Cock. The fourth and final state names C. J. Visscher as publisher.

Pictures of the plight of the peddler who falls asleep and is robbed by a band of mischievous and malicious monkeys are found as early as a century or more before Bruegel. The theme was used in graphic works in Italy, Germany, and the Netherlands. It is found also, even earlier, in marginal artwork or illuminations of the late Gothic period.

More than a score of apes have descended on the itinerant haberdasher and “notions” peddler as he lies blissfully sleeping outdoors in a rural area. Some are tailed, some devoid of tails; but all are inspired imitators of humans, in a simian sort of way.

In the lower left corner, one of them lustfully regards his own image in the mirror. Above him, another is voiding in the peddler’s feathered hat. Still higher, two play like children on hobbyhorses. Higher still, two roll in a stolen basket.

To the right of them, one beats a drum; another, up the tree, blows a horn; while four hold hands, dancing in a ring to the music. The trees have been hung with the poor merchant’s finest merchandise. We see beads, purses, gloves, “costume jewelry,” etc. Even the peddler’s person is invaded. Behind him, a monkey makes a drastic and unmistakable commentary with his nose and fingers. Another, atop the peddler’s head, is “grooming” his locks—looking for vermin, that is.

Below, one tries on boots; another searches through the peddler’s money pouch; in his goods case a simian tries on spectacles.

And so human finery creates fun for monkeys.

Plate 33 is reproduced by permission of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City (Dick Fund).

Here again van der Heyden is believed to have been the engraver.

The original drawing, in the British Museum, was executed with pen and brownish ink. It bears at lower left the signature “Brueghel 1558.”

Two states of the plate are recorded: The first lacks Bruegel’s name and identifies the publisher at the lower right with the words “H. Cock excud. cum Privileg.” The second state replaces this with the name of Bruegel as “invent.” and Joan Galle “excudit” (publisher).

A picture within a picture hangs on the wall at top, left of center. A man in medieval garb sits amid a shambles of shards looking into a mirror. The legend below expresses in Flemish this pithy and pregnant thought: “No one knows himself” (Niemāt en kent hē selvē, i.e., Niemant en kent hem selven). It is the ironic commentary—not an answer—to the age-old injunction: Know thyself!

In the scene below, five figures—each labeled “Elck” or “Everyman” on his garments—are searching, pawing, clawing, tugging through an endless pile of things . . . things . . . things. . . . The foreground resembles, as the saying goes, “a Belgian attic.” A sixth and seventh, in the far distance, go seeking with lanterns.

An eighth figure is seen only in part. He holds a lantern in the hogshead at lower left. Were he to step forth, “Elck” would be on the hem of his garment too.

Unrealistic as the action may be, we somehow cannot feel that the import is utterly obscure. The general drift is indicated by the verses at the bottom in Latin, and below, at greater length, in French, at the left, and Flemish, at the right.

An English equivalent of the French and Flemish is attempted here. Too free for a “translation,” it is rather a restatement of the feeling that seems to flow from the cryptic picture and the verses attached to it:

Always, each man is seeking for himself alone—

And everywhere ... So how can one stay lost?

Each man will pull and tug and grunt and groan,

Seeking to get more for himself—get most!

And no man knows himself despite such seeking;

No light will help him in this lonely place.

Strange! Though he looks with eyes forever open,

He never sees at last his own true face.

The Elck seeking in the center of the picture carries a fat money-bag at his waist. Eyeglasses and a lantern do not help him to find what he seeks, though just about every kind of thing is scattered in a tangled confusion about the place. There are household goods, tools, games (dice, cards, chess, etc.). There are bales and bags and bundles. The goods and the distractions of the world are all about. Yet Everyman, in every form, is always and everywhere seeking in vain.

The Elcks here shown are aging. They are distraught, frustrated, unhappy. The abundance of things does not fulfill their need; and the lantern leaves them as much as ever in the dark.

It is a bitter business, with no final success in sight, to be looking, looking, looking only for one’s self. For no man (Nemo) will find himself here, even though he may find “private gain” for himself.

Translation of Latin caption: There is no one who does not seek his own advantage everywhere, no one who does not seek himself in all that he does, no one who does not yearn everywhere for private gain—this one pulls, that one pulls—all have the same love of possessing.

Both of these “polar” prints were engraved by van der Heyden and published by Cock. Both plates are dated 1563.

They are polar and complementary because exactly opposite in conception, though matching in form.

Everything, everyone is lean, scrawny, half-starved in this poor kitchen. Shortage reigns here. At the table, five men, like underfed coyotes, reach into a bowl to clutch mussels or oysters. Under the table, a bitch with hungry pups tries to get some nourishment from the empty shells.

At center front, a mother, her thin breasts drained dry, tries to feed her nursing child from a horn.

A bearded man at left front pounds away, seeking to soften a piece of hardtack or possibly a dried herring. At the hearth some watery soup is being stirred over a scanty fire. The available “reserves” of food appear to consist of a few turnips, a carrot or two, and a half-eaten loaf of bread on the table.

On the wall at the right hangs a slack bagpipe, emblem of scarcity.

Mynheer Fatman has opened the door—possibly by mistake. A man and woman seek to induce him to come in; but he has seen enough; he is already on his way elsewhere. This is not the place for him.

The texts at the bottom of the picture in rhymed French and in Flemish state the sentiments that must fill his overworked heart and surge through his cholesterol-clogged arteries. Translated freely they might be:

Where Thinman’s cook there’s meager fare and

lots of diet trouble.

Rich Kitchen is the place for me; I’m going

there, on the double!

Thinman is the Flemish “magherman,” the scarecrow at the hearth.

Rich Kitchen is where we next see Fatman, or his counterparts.

Flaccid bagpipe on shoulder, Thinman or one of his scrawny clan has just opened the door of Rich Kitchen, but is getting a cold—but fat—shoulder from the overstuffed inmates. They don’t want the likes of him anywhere in sight. The fat fellow nearest the door pushes him out and gives him a kick for extra emphasis. A fat dog nips at his ragged shanks.

The corpulent clan reject this reminder of hunger. Theirs is the same deep-down sincerity to be found in the anecdote of the beggar who penetrates to the presence of a rich man to ask help; the rich man pulls the bell-cord and orders his butler: “Throw this fellow out! He’s breaking my heart.”

The verses inscribed below in French and Flemish tell what these fat men are saying or thinking. Freely done into English they run:

Beat it, Thinman! Though you are hungry, you are wrong.

This is Fat Kitchen here, and here you don’t belong!

In fact, several of the overstuffed pieces of human furniture in the scene are not even aware of the episode at the door; they are too busy gorging.

One fat fellow with a tall hat, pensively biting off a cheese or huge roll, wears a chain of sausages round his neck, like a gourmandizer’s garland.

The opulence and overabundance are fairly sickening. Hams, sausages, pigs’ feet, pigs’ heads, cheeses, baked goods, and so forth, hang from the ceiling and sprawl over the table.

Three pots simmer over a roaring fire. A suckling pig is basted at a grill before it, while a huge overfed cat laps the drippings as they fall.

At the near end of the table, a mother, almost as wide as high, feeds her fat baby at one breast; the other is in readiness to carry on the infant’s meal. Meanwhile, Mamma holds a tumbler, no doubt filled with something nourishing—perhaps a heavy Malz beer ... a sturdy stout ... or maybe straight cream liberally laced with sugar and cinnamon. After all, a nursing mother must keep up her strength!

In spite of the broad farce which such commentary may suggest, this pair of pictures in fact have in them something horrible. The scarcity in one is too savage and oppressive; the excess in the other too compulsive and distorted. They are more than a little monstrous, especially when regarded together. And this impression is probably not peculiar to modern eyes and minds.

In the second state of this plate, reproduced here, Pieter van der Heyden, the engraver, is identified by a monogram which appears on a leg of the table, lower center. Below it, the publisher, Cock, has placed his name and authorization and the date of publication, 1559. “P. Brueghel” is named as “inventor” on a card suspended from the cracked monster-egg at the lower right. Flemish verses appear in three couplets below the picture.

Such is the second state of the plate. In a rare first state neither Heyden nor Bruegel was identified. In a third state, the credit to Cock was obliterated, and in the margin below the picture, the initials of the new publisher, T. Galle, were inserted. In a fourth state, French verses were added. And in a fifth state the name of the publisher was changed to Joan Galle.

No original drawing of this subject survives today.

This is a witches’ brew of quackery, gullibility, and superstition.

Malleghem was a proverbial village, a sort of “Suckerville” or “Jerkburg” of the Flemings. Mal in Flemish means crazy or foolish. A Flemish district, in what is now Belgium but was then part of the undivided Netherlands, bore the name Malleghem. By analogy of sound this was related to Fools’ Home (Mal-heim).

In particular, the Malleghemians were supposed to swallow any fake nostrums and cure-alls; they were natural prey for quacks. Madness, it was widely believed in Bruegel’s time, arose from alien growths in the brain or head, such as bumps and tumors on the forehead. It is this that the “witch” has come to Malleghem to cure. She is at work over the far end of the bench. In her left hand she holds up triumphantly the “stone” that she had just cut from the head of the patient whose chin she still grasps with her right.

Others among the crowd awaiting her attentions look on in stupid anticipation or shout their excitement. On the wall, upper center, appears a placard advertising the witch’s wondrous healing arts. It pictures a huge knife and from the banner hang many stones that she has, ostensibly, removed from other patients.

A free approximation of the Flemish verses under the print will help to illuminate the spectacle. It is herself speaking:

Folk of Foolsville, be of good cheer;

I, Lady Witch, wish to be well-loved here

As I am elsewhere. . . .

I have come here to cure you

With my proud aide; I assure you

We’re at your service: draw near.

So let them come on, come one and come all,

The large and the small. . . .

Hurry on, every one,

If you’ve a wasp in your dome

Or are plagued by a stone.

The “aide” is the fool-hatted man with a lantern casting light on the witch’s work. He carries a pouch for her surgical tools.

Another patient has been tied to a chair, to the left of the bench. His head is being doused, perhaps in preparation for the knife. In the right corner, an enormous empty eggshell, symbol of futility and barren folly, serves as surgery. Dozens of stones are sliced away from the patient there; they shower over the floor.

The motive of the round stone recurs elsewhere in this close-packed composition. Also the motive of the bird. One sits on the back of the chair mentioned above. A stupefied or alarmed owl perches at the extreme left, turned as if unable to bear watching the mass madness.

Higher, somewhat left of center, a demon-bird perches on a huge jug. A horn or musician’s pipe is thrust through his nostrils. A bass viol is carried on one shoulder by a vendor of nostrums or salves. He has filled his bottles from one of the siphon tubes at the two jugs which stand on a stage or platform supported on hogsheads, such as actors used in festival plays of that period.

Against that platform leans an enormous tool, surmounted by a crescent blade. It is a giant “stone remover.” Something of this size is needed to remove a stone as large as that growing on the shouting sufferer at the lower left. In his frenzy he clutches the purse of the man who is helping to support him. Gold coins spill on the floor and roll, as the extracted stones are doing elsewhere. Some kind of commentary is indicated by the two hooded figures at the lower left. Are they deploring all this stupidity and deception? Or—since one holds a stone and has two stones in front of him—are they impressed by the essential helpfulness of it all?

Above them, to the left of the platform, five figures wearing visored capes look on also. One has arrived on a horse. In front of him (and just above the man with the super-stone) a helmeted man walks on crutches, and with the help of a wooden leg. He seems to have arrived also to consult the busy witch.

Peering out from under the bench below the witch is a winking man with padlocked mouth. A fool’s head up his sleeve gives him away. He, too, holds a stone taken from a basket full of them.

Some elements of sanity—or nonparticipation in the madness—are glimpsed (as so often with Bruegel) in the far background. Grain is being carried across a plank bridge to a mill powered by a waterwheel. At top center a fisherman goes about his useful business in his boat.

But then again, between mill and fisherman stands a strange, leaning hill, like an upside down carrot or turnip. Its tip projects through a bowl-like rim. And from that strange bowl there pours down on an agitated man below—a shower of stones!

The words “Brueghel Invē” appear in the extreme upper left corner; the name of the publisher, Cock, along the lower left margin. No date appears and no engraver’s symbol. The date is probably 1558 or 59; and the engraver, Philippe Galle.

The working drawing, pen with brownish ink, is in the Kupferstichkabinett, Berlin. It is signed and dated “Brueghel 1558” in a hand not Bruegel’s own, but Tolnay believes the information conveyed is correct.

The alchemist here is the shaggy and desperate man heating the crucible over the blow-flame at the left. His wife behind him woefully seeks to get a coin from an empty purse, but nothing comes. Above her, their three children scramble, and search in the empty larder.

A figure wearing a fool’s cap shouts or sings as he fans the flame in a brazier with a bellows. Folly drives on the insane, insatiable quest to win gold from dross.

At extreme left a ladle, held by an “off-scene” hand, pours more fuel on the fire.

At a desk or lectern at the right sits the spokesman for experience or sanity—a scholar who points to books before him for a punning commentary on the alchemist’s efforts. The headings of the pages to which he points are “Alghe” and “Mist,” reminiscent of the modern German alles Mist. Even in Bruegel’s Flemish they stood for something much like “All rubbish.”

Such is the present state of this follower of the delusions of alchemy. But his future and final fate is shown beyond the window, in an ingenious example of graphic “time travel.” There the same five members of the family—alchemist, wife, and children—now completely penniless, are being received at the poorhouse, or “hospital.” One of the children in this future scene still wears the same pot on his head as in the main picture. The alchemist still wears one slipper, and one shoe of a sort. A bleak prospect, and inevitable.

The wealth of detail and variety in Bruegel’s original drawing has been preserved admirably. Ebria Feinblatt calls the composition “one of the most beautifully drawn of Bruegel’s satirical subjects, with the properties of the various materials finely rendered by the engraver.”

Even the labeling of some of the hapless alchemist’s supplies is preserved legibly in the engraving. Thus a bag leaning limply against the stone in lower left is labeled “Drogery” (drugs). And near the lower right corner, the table, made of a dismounted door lying on a tub, bears two labeled cans, one of which can be read as “sulfer.”

The writ or document nailed to the face of the hearth above the alchemist’s head also contains legible words, one of which seems to be “misero.”

The situation depicted here is not entirely fanciful or far-fetched. See the tale that Chaucer has put into the mouth of the Canon’s Yeoman in his Canterbury Tales.

Deceptions and disappointments inherent in alchemy were exposed by various moralistic and iconoclastic writers of Bruegel’s time and shortly before. Tolnay has quoted, for example, lines from Agrippa von Nettesheim in his Vanity and Uncertainty of the Sciences (Die Eitelkeit und Unsicherheit der Wissenschaften): “The making of gold ... is surely a right lovely discovery, and a nice unpunishable swindle, whose vanity and futility easily reveal themselves, insofar as that is promised which Nature can in no way tolerate or attain; for every other art and science imitates Nature but never surpasses Nature, since the power of Nature is far stronger than the power of art.”

Agrippa von Nettesheim, to be sure, could not know that within four centuries the art or science of nuclear physics would transmute elements, turn matter into energy, and threaten the very survival of mankind on earth.

The identity of the engraver is unknown. In the first state of the engraving the small plaque at the lower right contained the name of the first publisher, Philippe Galle, and the date 1574 (five years after Bruegel’s death). In the second state, here reproduced, this was replaced by only the credit to the second publisher, “Jo. Galle excudebat.” Farther left, the original artist is named in Latinized form: “Petrus Bruegel inven.”

At lower center, worked directly into the design, is the Latin motto, meaning: “Time devouring all and each.”

Doubt has been voiced as to whether this engraving was in fact based on a Bruegel original. The consensus of scholars seems to support Gustav Glück’s contention that it was. Earlier in this book we have seen Bruegel’s use of pagan mythology in a subsidiary way in landscapes and marine (ship) subjects. In recent years, The Calumny of Apelles, a Bruegel drawing from 1565, has come to light. Like this work, it is concerned completely with a classical theme.

The stamp of Bruegel is clear in many details of treatment here.

The essential meaning is obvious: Time destroys all that it has brought into being. Nothing survives permanently, neither man nor his monuments.

Like Saturn in classical mythology, Time devours his own offspring. The identification of Time and Saturn grows out of the persistent and understandable confusion of two names: Kronos (the Greek name for the figure who corresponds to the Latin’s Saturn), and Chronos (Time).

Adriaan Barnouw has written that the infant that Father Time here carries on his right shoulder “betokens the principle of constant renewal.” This would imply that the babe is along, so to speak, “just for the ride.” However, examination of the print shows beyond doubt that Time is engaged in a grisly act of cannibalistic infanticide. Everything is a child of Time, comes into being within Time, and is eventually swallowed up mercilessly by Time. The face of Time here, though grim, is not savage; he eats his child without frenzy, rage, or lust; it is simply the way things are. And in his left hand Time raises high the snake with tail in mouth, a widespread symbol of renewal, continuity, and the endless cycle of life.

These major allegorical acts take place amidst a plethora of allegorical objects and symbols. Time rides his car, drawn slowly by the light horse of day (sun ornament) and the darker horse of night (moon ornament).

The great globe of the earth itself is carried on the car, belted around by the signs of the zodiac, together with their conventional symbols. Three of the signs are a little outside the circle: the scorpion is halfway up the trunk of the tree (Tree of Life?); Libra, the scales, hang higher from a branch; and the crab (lobster?) seems to be slipping off the wagon between the wheels.

In the crotch of the tree stands a clock, its hammer striking the unceasing hours.

Time himself sits on a great hourglass. One foot is shod, the other bare—a symbol which this writer is at a loss to interpret.

The earth rests on a bed of bare boughs in the cart. The body of the wagon is built like a galley, with hook-beaked prow. Its wheels contrast: the hind wheel’s tire is woven of vines; the front wheel flaunts an ornately patterned tire. This writer’s guess—nothing more—is that there is some reference here to the seasons—perhaps autumn and spring. Or possibly it should suggest that Time sometimes travels along smoothly, sometimes roughly.

Time is followed by mounted Death, bearing a long scythe. As always, mortality is on the march. The Grim Reaper mows down all life when its Time has come. Behind death follows an angelic herald, trumpeting atop an elephant of truly Bruegelian proportions. The Latin caption identifies this herald as Fame. And Fame all too often follows only after Death.

Adriaan Barnouw concludes: “All that remains of man’s deeds is a breath of wind.”

Time and his entourage ride roughshod over a road strewn with the emblems and objects of human life. Here, in profusion, drawn with precise detail, are scattered men’s tools and trophies. Like blinded Samson, they lie “at random, carelessly diffus’d.”

From left to right we can identify: the painter’s palette and brush; the musician’s instruments and compositions; the artisan’s tools; the warrior’s weapons; the crown of the king, the helmet of the knight, the hats of the cleric and the burgher; then sword, scepter, and pruning shears; the broken column of a church or temple; a treasure chest, a money-bag.

All that men slave, sweat, kill, conspire, cheat, or bribe to acquire, lies here like rubble in the road. To on-marching, devouring Time these “treasures” mean—nothing.

Bruegelisms permeate the background. At left two men in a fishing boat sail in the direction of a town that burns on the horizon, filling the sky with flames and smoke. To the left of the town is a squat water fort.

On the other side, just above the horse’s hips, a rural couple walk side by side. Thomas Hardy’s verse comes to mind:

Yonder a maid and her wight

Come whispering by.

War’s annals will fade into night

Ere their story die.

Far back at the right are the buildings of a town. On the green near the church, dancers have formed a ring around a tall maypole. They are not aware of the Triumph of Time, or if they are, they are not depressed by it.

A windmill and a castle are farther back, up the hills.

This, too, shall pass; Time will take care of that. But meanwhile it gives the background an illusion of safety and durability of a solid Dutch sort.

Translation of Latin caption: The horses of the sun and moon rush Time forward; who, borne by the four Seasons through the twelve signs of the rotating extensive year, bears off all things with him as he goes on his swift chariot—leaving what he has not seized to his companion Death. Behind them follows Fame, sole survivor of all things, borne on an elephant, filling the world with her trumpet blasts.

Plate 39 is reproduced by permission of Mr. and Mrs. Jake Zeitlin, Los Angeles, California.