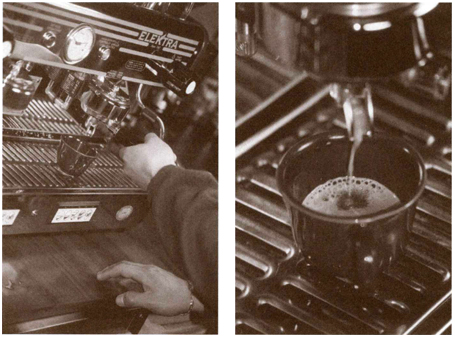

10 THE ESPRESSO SIDE OF IT

What makes espresso espresso

Espresso history

Classic, beatnik, and mall espresso

Espresso is several things at once. It is a unique method of brewing in which hot water is forced under pressure through tightly packed coffee, one or two servings at a time. It is a roast of coffee, darker brown than the traditional American roast but not extremely dark. In a larger sense, it is an entire approach to coffee cuisine, involving not only roast and brewing method, but grind and grinder, a technique of heating and frothing milk, and a traditional menu of drinks. In the largest sense of all, it is an atmosphere or mystique: The espresso brewing machine is the spiritual heart and aesthetic centerpiece of the great coffee places, the cafès, caffès, and coffeehouses of the world.

WHAT MAKES ESPRESSO ESPRESSO

The espresso system was developed in and for cafès and caffès. Despite advances in inexpensive home espresso systems, it is still difficult to duplicate the finest caffè espresso or cappuccino in your kitchen or dining room without spending several hundred dollars on equipment. Even those on a budget can come close, however, and I outline the strategy for that effort in Chapter 11. For now, I want to discuss the big, shiny, caffè machines.

Fundamentally, they make coffee as any other brewer does: by steeping ground coffee in hot water. The difference is the pressure applied to the hot water. In normal drip-brewing processes, the water seeps by gravity down through ground coffee, loosely spooned into a filter. In the espresso process, the water is forced under pressure through very finely ground coffee packed tightly over the filter.

A fast, yet thorough brewing makes the best coffee. If hot water and ground coffee stay in contact too long, the more unpleasant chemicals in the coffee are extracted and the more delicate, pleasant aroma and flavor components evaporate. Hence the superiority of the espresso system: the pressurized water makes almost instant contact with every grain of ground coffee and rapidly begins dribbling out into the cup. Another advantage of the espresso system is freshness. Every serving is brewed in front of you, a moment before you drink it; in most cases the coffee beans are also ground immediately before brewing. Other restaurant brewing methods make anywhere from a pot to an urn at a time from preground coffee, then let it sit, where it loses flavor and aroma to the detriment of the coffee and the advantage of the ambience.

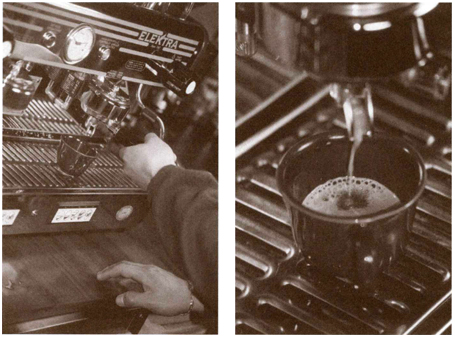

EVOLUTION OF THE CAFFÈ MACHINE

The oldest caffè espresso machines and the smaller home espresso machines work on a simple principle. Water is heated to boiling inside a closed tank; a space is left at the top of the tank where steam gathers. When a valve is opened below the water line, the pressure of the steam trapped at the top of the tank forces hot water out of the valve and down through the coffee. The first European patents for the idea were filed between 1821 and 1824, and a variation of the method was first applied to a large caffè machine by Eduard Loysel de Santais in 1843. Santais’s machine wowed visitors to the Paris Exposition of 1855 by producing “two thousand cups of coffee an hour.” Santais’s machine brewed coffee a pot at a time, however, and used steam pressure, not to force the brewing water directly through the coffee, but instead to raise the water to a considerable height above the coffee, whence it descended through an elaborate system of tubes to the coffee bed. The weight of the hot water, not the trapped steam, applied the brewing pressure.

New Century, First Espresso Machine

It was not until the dawn of the twentieth century that the Milanese Luigi Bezzera patented a restaurant machine that used the pressure of trapped steam to directly force water through ground coffee. The Bezzera machine also innovated by distributing the freshly brewed coffee through one or more “water and steam groups” directly into the cup.

In many respects the Bezzara machine established the basic configuration that espresso machines would maintain throughout the twentieth century. See the illustration to the right. These machines decreased the size of the strainer that held the coffee, but increased the number of valves, enabling them to produce several single cups of coffee simultaneously, rather than a single big pot at a time. Then as now, the espresso operator packed a few teaspoons of very finely ground, dark-roasted coffee into a little metal filter. The filter was clamped into a receptacle called the group, which protruded from the side of the machine. When the operator opened the valve (or, in more modern machines, pulls a handle or pushes a button), hot water was forced through the coffee and into the cup.

An early caffè machine of the type that helped create the culture of espresso during the first half of the twentieth century. It uses the simple pressure of steam trapped at the top of the boiler to force water through the bed of ground coffee at the right of the cross-section diagram and into the cup. A second outlet, at the top left in the diagram, taps the steam at the top of the boiler and directs it out a steam valve and wand for use in heating and frothing milk.

The early espresso machines look like shiny steam engines pointed at the ceiling. The round water tank is set on end and bristles with picturesque spouts, valves, and pressure gauges. These shiny towers topped with an ornamental eagle dominated the European caffè scene until World War II. After the war, Italians wanted an even stronger cup of coffee to go with their Vespas, and they wanted it faster.

The Gaggia Mid-Century Breakthrough

In 1948, Achille Gaggia obliged them with the first truly modern espresso machine. As Gaggia’s design eventually evolved, the water tank was laid on its side and concealed inside a streamlined metal cabinet with lines like a Danish-modern jukebox. The simple valve of the old days was replaced with a spring-powered piston that pushed the water through the coffee harder and faster. The operator depressed a long, metal handle. The handle in turn compressed a spring-loaded piston that forced a dose of hot water slowly through the coffee as the handle majestically returned to its original erect position. The new spring-loaded machines pushed the water through the coffee at a pressure that is now accepted as ideal for espresso brewing: a minimum of 9 atmospheres, or nine times the ordinary pressure exerted by the earth’s atmosphere. By comparison, the prewar, steam-pressure machines exerted a feeble 1.5 atmospheres of pressure.

Computer Age Espresso

In the 1960s, just when pumping the handle became the signature performance piece of espresso caffès, less dramatic and more automated means for forcing the hot water through the coffee began to evolve. The earliest of these no-hands machines were built around simple hydraulic pumps. Today’s versions heat water separately from the main reservoir, control water temperature and pressure with precision, and flatter the hi-tech pretensions of the late twentieth century with digital readouts.

These push-button machines tend to carry the streamlined look to an extreme. Everything is concealed inside a single, sleek, enamel-and-chrome housing. All have one feature in common: The operator pushes a button or trips a switch rather than pumping a long handle. Since so much of the process is automated, the push-button machines are easier for the novice to master, but do not necessarily make better espresso. Proprietors of some of the better caffès in the San Francisco Bay Area, at any rate, still prefer the pump-piston machines because they give the sophisticated operator maximum control over the brewing process.

Enter Frothed Milk

With the long, gleaming handle going the way of the running board, the best routine left to the espresso operator is heating and frothing the milk used in drinks like cappuccino and caffè latte. Espresso is a strong, concentrated coffee, and, in accordance with European tradition, many of the drinks in espresso cuisine combine it with milk. If the milk were unheated, it would instantly cool the coffee. Early in the history of the espresso machine, someone, probably Luigi Bezzara in 1901, realized that the steam collected in the top of the tank could be used to heat milk as well as provide pressure for making coffee. A valve with a long nozzle was fed into the upper part of the tank where the steam gathers. When the valve is opened by unscrewing a knob, the compressed steam hisses out of the nozzle. The operator pours cold milk into a pitcher, inserts the nozzle into the milk, and opens the valve. The compressed steam shoots through the milk, heating it and raising an attractive head of froth or form.

Caffè patrons soon discovered that steamed, frothed milk both tastes and looks better than milk heated in the ordinary way, and it became an important part of espresso cuisine, particularly in the United Sates of the 1990s. The white head of foam is decorative, can be garnished with a dash of cocoa or other garnish, prevents a skin from forming on the surface of the milk, and insulates the hot coffee.

A REMARKABLE CUP OF COFFEE

It is difficult to say how much of the success of the espresso machine is due to its scientifically impeccable approach to coffee making and how much to its drama and novelty, but, given European tastes, it certainly does produce a remarkable cup of coffee: freshly ground, and brewed so quickly that, as an Italian friend of mine says, you get only the absolute heart of the coffee.

Nevertheless, many a mainstream American coffee lover facing a straight espresso for the first time may take one swallow and either finish it stoically or hide the little cup behind a napkin. The distaste is understandable. This impeccable brewing system is designed to make a cup of coffee in the southern European or Latin American tradition rather than in the northern European or North American. Good espresso is rich, heavy-bodied, and almost syrupy; furthermore, it has the characteristic bittersweet bite of dark-roast coffee.

But the sharp flavor and heavy body make it an ideal coffee to be drunk with milk and sugar, and it is this virtue that has made espresso cuisine the latest coffee rage in North America. The “latte,” a drink that does not even appear on espresso menus in Italy, combines espresso with gigantic quantities of hot milk (or milk substitutes) and endlessly customized syrups and garnishes. This now ubiquitous drink seems on its way to replacing the bottomless cup of tradition in the morning hearts and bellies of America.

ESPRESSO CUISINES, CLASSIC TO POSTMODERN

There are many espresso cuisines, not just one. Every culture adopts the potential of the machine and the espresso system to its own tradition, from the sugar-heavy tintos of Cuba to the ultra-tiny cafezinhos of Brazil.

In North America at least three espresso cuisines overlap to confuse the novice. The first is the classic Italian cuisine as practiced in the best bars of Italy. The second is the Italian-American beatnik espresso of the 1950s through ’80s, which still dominates in college towns and the bohemias of large cities. The third is what we might term “mall” or perhaps postmodern espresso, the thoroughly Americanized, constantly morphing, many-flavored cuisine that brought us the gigantic caffē latte and its ever-proliferating progeny.

Classic Italian Espresso Cuisine

Southern Europeans have drunk strong, sharply flavored coffee in tiny cups or mixed with hot milk for generations. Consequently, most of the drinks in espresso cuisine are not original with the machine; rather, the machine brought them from promise to perfection. Here are some of the most popular drinks from the classic Italian cuisine.

Espresso. About 1 to 1½ ounces of espresso coffee, black, usually drunk with sugar. Fills about 1⁄3 to 2⁄3 of a demitasse, no more.

Espresso Ristretto. “Restricted” or short espresso. Carries the “small is beautiful” espresso philosophy to its ultimate: The flow of espresso is cut short at less than 1 ounce, producing an even denser, more perfumy cup of espresso than the norm.

Espresso Lungo. Long espresso; about 2 ounces or 2⁄3 of a demitasse.

Double or Doppio. Double serving, or about 2½ to 3 ounces of straight espresso, made with twice the amount of ground coffee, served in a 6-ounce cup.

Cappuccino. In Italy, a single serving (about 1¼ ounces) of espresso, topped by a dense, soupy froth, served in a 6-ounce cup. The espresso goes into the cup first, then the froth, which picks up the coffee as it is poured, lifting and combining with it. The result is a delectable fusion of espresso and heavy froth. Usually the completed drink is lightly dusted with a garnish of intense, unsweetened cocoa, which further and subtly complicates the aromatics of this splendid beverage.

Unfortunately, the cappuccino is North America’s most misunderstood and abused espresso drink, with versions ranging from miniature caffè lattes with virtually no froth to the Seattle “dry” cappuccino, in which the froth is stiff and meringuelike, floating like an afterthought atop an often bitter, overextracted shot of espresso.

Espresso Macchiato. A single serving (1 to 1½ ounces) of espresso “stained” with a small quantity of hot, frothed milk. Served in the usual espresso demitasse.

Latte Macchiato. An 8-ounce glass filled with hot, frothed milk, into which a serving of espresso is slowly dribbled. The coffee “stains” the milk in faint, graduated layers, darker at the top shading to light at the bottom, all contrasting with the layer of pure white foam at the top. This is the drink Italians take when they want a tall, milky morning coffee.

Classic Espresso Cuisine at Home. Detailed instructions and suggestions for brewing espresso and frothing milk with home machines are given in Chapter 11, together with recipes from all of the espresso cuisines.

Beatnik or Italian-American Espresso Cuisine

Compared to the chaste, elegantly restrained espresso cuisine of contemporary Italy, the menu of drinks that evolved from the interaction of Italian immigrant caffè owners and their youthful American counterculture customers in the 1950s through ’80s moves us a bit closer to the unbridled espresso exuberance of 1990s.

Here are some variations and drinks that evolved in the heyday of navy turtlenecks and madras miniskirts. In addition to differences in how the various drinks are constructed, the coffee itself in the beatnik cuisine is sharper, more darkly roasted, and more bitter than the round, sweet, espresso blends used in Italy.

Espresso Romano. A single serving of espresso served in a demitasse with a twist or thin slice of lemon on the side. The lemon is wiped around the lip of the cup leaving a faint trace of lemon oil. The scent of the lemon subtly (and exquisitely) combines with the aromatics of the coffee as you sip it.

Beatnik or Italian-American Cappuccino. About one-third espresso, one-third milk, and one-third froth, served in a heavy 6-ounce cup, garnished with unsweetened cocoa. Not quite as elegant as the true Italian cappuccino with its enveloping, soupy froth (here), but Allen Ginsberg liked it this way.

Caffè Mocha. As served in the Italian-American caffès of the 1950s onward, about one-third espresso, one-third strong hot chocolate, and one-third hot, frothed milk. The milk is added last, and the whole thing usually is served in an 8-ounce mug, sometimes topped with whipped cream. With the classic mocha the hot chocolate is made very strong, so it holds its own against the espresso, and is at most lightly sweetened. The customer adds sugar to taste. Most contemporary caffès add chocolate fountain syrup to a caffè latte and call it a mocha. So be it.

Caffè Latte. At least until recently, ordering a “latte” in Italy got you a puzzled look and a glass of cold milk. The American-style caffè latte does not exist on the menus of Italian caffès, except perhaps in a few places dominated by American tourists.

Exactly who in America started the practice of serving a little espresso with a lot of hot milk in a very large bowl or glass and calling it a caffè latte is open to question. Obviously breakfast drinks of this kind have existed in Europe for generations, but the contemporary caffè version of the drink is an American invention. I was told by Leno Meiorin, proprietor of the original Caffè Mediterraneum in Berkeley, that he invented it in 1959 when customers complained that the latte macchiati and cappuccini he was serving were too stingy in size. Certainly the Mediterraneum was the first place I saw caffè latte listed on a menu. For the first year or two Leno served his caffè lattes in lovely fluted glass bowls but switched to the now-classic, 16-ounce beer glasses when too many of the bowls walked out the door with his customers. Some upscale caffès have returned to serving their caffè lattes in bowls.

Espresso con Panna. In its original Italian-American configuration, the con panna consists of a big dollop of very lightly sweetened, heavy whipped cream laid atop a single long serving of espresso in a 6-ounce cup, garnished with unsweetened cocoa.

Café au Lait. In some American caffès, a drink made with about half filter coffee and about half hot milk and froth, served in a 10-, 12-, or 16-ounce glass or bowl. The proportion of coffee to milk has to be larger than with the espresso-based caffè latte, because American filter coffee is so delicate in flavor and light in body compared to espresso.

The Italian-American or Beatnik Cuisine at Home. Detailed instructions and suggestions for brewing espresso and frothing milk with home machines are given in Chapter 11, together with recipes from all of the espresso cuisines.

Postmodern or Mall Espresso Cuisine

Americans have subjected the classic espresso cuisines to their own brand of cultural innovation. In general, it would seem that we are frustrated by the brevity and precision of the classic cuisines, and want bigger drinks with more in them. Perhaps an ounce of coffee in a tiny cup does lack comfort in the middle of the Great Plains or atop the World Trade towers. Still, I think it would be better if Americans understood and experienced the intensity and perfection of the classic espresso cuisine before immediately expanding it, watering it down, or adding ice to it. But, for better or worse, the latte cuisine is here to stay. Here are some of the more honorable results of American espresso cuisine tinkering.

Caffè Latte by the Ounce. A Brazilian friend of mine always expresses amazement at what she sees as evidence of American practicality and directness. Somewhere along the line in the 1980s, American espresso operators dispensed with all of the fancy names and cups of the classic Italian and beatnik cuisines and simply started asking customers how much espresso they wanted, how much milk, and put the two together in a series of ever larger cardboard or Styrofoam® plastic cups. The result is certainly practical, though hardly elegant. Furthermore, to satisfy the precise and conflicting needs of dieters, the milk part of the menu was expanded to include everything from skim milk to soy milk.

Thus, rather than a cappuccino, latte macchiato, or caffè latte, American espresso drinkers simply specify the number of servings of espresso they prefer (single, double, triple, or the murderous quad), the volume of milk (small or short, or enough milk to fill an 8-ounce container; tall, enough to fill a 14-ounce container, or various pop terms like grande, 16 ounces, or venti or mondo, enough to fill 20 to 24 ounces) and kind of milk (non-fat, 1 percent, 2 percent, 3 percent, or 4 percent butterfat, soy, or rice). Example: “Triple soy grande,” which translates as three shots of espresso in hot soy milk with a light head of froth to fill a 16-ounce cup.

Flavored Caffè Latte by the Ounce. During the heyday of Italian-American or beatnik espresso, every big-city caffè sported a lineup of colorful Italian-style syrup bottles on the back bar put out by the family-owned Torani company of San Francisco. These syrups were added to seltzer or sparkling water to make various soft drinks. In the late 1970s, L. C. “Brandy” Brandenburger, an entrepreneur from Portland, Oregon, thought to begin adding these syrups to milk-based espresso drinks like cappuccino and caffè latte. The idea caught on, and was elaborated with particular enthusiasm in Seattle in the early 1990s, where experimentation with syrups reached truly baroque dimensions. One kind of syrup might be added to the espresso, a couple of others to the frothed milk, and the whole concoction might be topped with whipped cream blended with still a fourth flavoring.

Meanwhile, the discreet garnish of unsweetened cocoa added to a classic cappuccino became similarly elaborated. I recall visiting an espresso cart in Seattle in the mid-1990s that offered customers the option of at least a dozen different garnishes for the froth on their espresso drinks, ranging from fresh-grated nutmeg through orange-flavored sugar and powdered vanilla. Thus, our hypothetical latte—one flavor in the coffee, two more in the milk, and a fourth in the whipped cream—might be further elaborated with the addition of a fifth flavor of garnish on the whipped cream.

The human nervous system, not to mention the memories of baristas and the budgets of caffès, could hardly sustain such extravagance. Today the flavoring craze seems to be abating. The flavored caffè latte may be here to stay, but the Cherry Cheesecake Latte and Raspberry Truffle Latte appear to be on their way out. Caffès increasingly follow the lead of Starbucks, which limits its syrups to a few popular favorites with proven affinity with coffee (hazelnut, chocolate, vanilla, raspberry, Irish creme, almond, mint) and its garnishes to chocolate, cinnamon, and nutmeg.

Double Cappuccino. (Or double cap, as in baseball cap.) If this innovation is made correctly, you should get about 3 ounces of uncompromised espresso, brewed with double the usual amount of ground coffee, topped with 3 to 5 ounces of hot milk and soupy froth. Usually served in an 8-ounce cup or mug. If the ground coffee is not doubled, and the operator simply forces twice as much water through one serving’s worth of ground coffee, you are getting a bitter, watery perversion, rather than a taller, stronger version of a good drink.

Mocha Latte, Moccaccino. The rugged, rich, original mochas of the old-time caffès (here) have been replaced by a more ingratiating drink. When made properly, this mall version of the mocha consists of a serving of espresso pulled directly into an ounce or so of good chocolate fountain syrup, after which the two are mixed and frothed milk is added to make a mocha with caffè latte proportions. Caffè Strada, in Berkeley, is reputed to be the original of the White Chocolate or Bianca Mocha, which replaces the usual chocolate syrup with either white chocolate melted in a double boiler or a special white chocolate syrup.

Iced Espresso. This is usually a double espresso poured over plenty of crushed, not cubed, ice, in a smallish, fancy glass. Some caffès top the iced coffee with whipped cream. Caffès that brew and refrigerate a pitcher of espresso in advance when they feel a hot morning on the way fail to deliver the brewed-fresh perfume of true espresso, but the practice still makes a fine drink and one that does not need to be iced and diluted as much as the version made with fresh espresso.

Iced Cappuccino. Best made with a single or double serving of freshly brewed espresso poured over crushed ice, topped with an ounce or two of cold milk, then some froth (not hot milk) from the machine to top it off. This drink should always be served in a glass. The triple contrast of coffee, milk, and froth, all bubbling around the ice, makes a pleasant sight on a hot day.

Granitas, Latte and Otherwise. Espresso granita is an Italian-American specialty that has morphed into a popular mall espresso drink that is usually called latte granita or, in Starbucks-speak, frappuccino.

Traditional Italian-American granitas usually involved freezing strong, unsweetened espresso, crushing it, and serving it in a parfait glass or sundae dish topped with lightly sweetened whipped cream.

The latte granita is a tall, smoothly icy drink that blends espresso, milk, ice, ample sugar, and (usually) vanilla. In the best caffès and bars the mixture is made with freshly brewed espresso and combined in powerful bar blenders. Less authentically, the ingredients are mixed in special dispensing machines. Made with fresh espresso the latte granita can be a very agreeable summer drink. If chocolate syrup is added to the mix it is called a mocha granita. Like the original caffè latte the latte granita can be endlessly elaborated with flavorings.

Chai, Chai Latte. Chai traditionally is a mixture of spices and black tea drunk with hot milk and honey in the Middle East, India, and Central Asia. The spice mix is usually boiled for 15 or 20 minutes and combined with black tea brewed in the usual way. This liquid concentrate is then strained and mixed with hot milk and honey. Some innovator in the American Northwest came up with the notion of making the hot milk component of traditional chai, hot, frothed milk. Chai is now part of the repertoire of American espresso cuisine, usually as a tall, hot milk drink called a chai latte. The tingly, lively spice mix carries the tea taste through the milk and allows tea drinkers to enjoy a milky morning beverage analogous to the caffè latte.

The traditional black tea chai has been joined by various noncaffeinated herbal tea chais, usually mint-based. The spices in traditional chai always include ginger, cinnamon, and cardamom, but may include smaller amounts of coriander, nutmeg, cloves, star anise, fennel, black pepper, and orange zest. Americans are wont to add vanilla to sweeten and mellow the mix, but vanilla is not a typical component in authentic chais. Lately instant chai mixes have appeared that are as stupid, cloying, and insipid as Middle Eastern Kool-Aid. If the idea of chai appeals to you, try to find a caffè that uses a chai mix brewed in the traditional way, with real spice and real black tea.

ESPRESSO MISUNDERSTANDINGS AND MISREPRESENTATIONS

Unfortunately, America has contributed more than innovation to the classic espresso cuisine. It has also watered it down, misunderstood it, and misrepresented it.

The art of espresso cuisine, as practiced in the best bars of Italy, is a masterpiece of coffee making, once tasted, seldom forgotten. Unfortunately, few American coffee drinkers have an opportunity to experience the aromatic perfection of a perfectly brewed single espresso or classic cappuccino. There are a growing number of American places where you can experience precise, knowledgeable espresso making, but even in these places, production is uneven, and you are as likely to encounter overextracted coffee drowned in scalded milk as you are a good cappuccino. Of the ninety or so caffès in the city I live in—Oakland, California—only two consistently produce genuine, authentic espresso. Good espresso cuisine demands not only a technically complete system and good intentions on the part of the caffè owner but a skilled and attentive operator, or barista. And the barista, as any conscientious caffè owner will tell you, is the most difficult part of the equation.

The Sin of Overextraction

The most prevalent and destructive mistake of novice espresso operators is running too much water through the coffee, often in a generous effort to provide customers with something more substantial than a little black stuff at the bottom of a demitasse. Instead of substance, of course, the customers are rewarded with a thin, bitter, watery drink that will make them wish they had ordered filter coffee or mint tea. Such overextracted coffee destroys all beverages in which it appears, including cappuccino and caffè latte.

The espresso system is so efficient that the goodness is extracted from the ground coffee almost immediately, making a small amount of intense brew, usually no more than 1¼ ounces per serving. Any water run through the coffee after that moment of truth contributes only bitter, flavorless chemicals to the cup. Those who want greater quantity should drink another style of coffee or order a double, which doubles both the amount of ground coffee and the amount of hot water run through it. As for cappuccino, the most egregious error is drowning the coffee in hot milk, which produces a weak, milky drink closer to a caffè latte than an intense, perfumy cappuccino.

AUTOMATED ESPRESSO

To compensate for untrained or careless baristas, the espresso industry in both Italy and the United States has been busily producing innovations essentially designed to automate the espresso brewing process to the point that the operator is reduced to irrelevant schlep or predictable button pusher. The most distressing result, which fortunately has not found much foothold in the United States, is machines that mix cappuccino and caffè latte in a device that works much like a commercial hot chocolate dispenser. The result is little more than instant coffee mixed with hot milk.

Other innovations are more positive. There are machines that grind the coffee, load it, and brew the espresso, all at the push of a single button, for example. The operator still has to heat and froth the milk, however. Even here help is on its way. The American Acorto company produces machines that do everything at the touch of a button, including frothing the milk and combining it with appropriate amounts of freshly brewed espresso. Kept properly tuned, the very expensive Acorto machines produce excellent beverages.

The simplest of these new, easy espresso expedients are pods of preground, prepackaged espresso coffee. The pod looks like a disk-shaped tea bag filled with ground coffee. The operator simply pops one (or two for a double) of these pods into a specially designed espresso filter, clamps the filter onto the machine, pushes the button or depresses the lever, and the brewing proceeds as usual. The operator still needs to know when to stop the brewing process, but the grind and measurement of coffee remain consistent.

Pod espresso is now available in home machines, and provides a helpful introduction for espresso beginners.