5 TASTING PLACE IN IT

Choosing coffee by origin

Blending and blends

Flavored coffees

Anyone who reads a newspaper is aware of how arbitrary the concept of nation-state can be. National boundaries often divide people who are similar and cram together those who are different. A Canadian from Vancouver has considerably more in common culturally with an American from across the border in Seattle than with a fellow Canadian from across the continent in Quebec, for example.

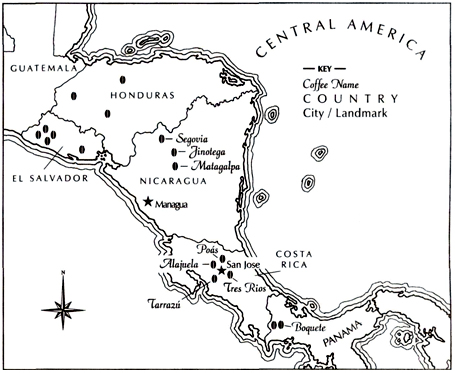

The concept of country often plays a similarly arbitrary and misleading role in understanding coffee. Countries tend to be large and coffee-growing areas small. Ethiopian coffee that is gathered by hand from wild trees and processed by the dry method hardly resembles coffees from the same country that have been grown on larger farms and processed by the wet method. On the other hand, some families of taste-alikes transcend national boundaries. In the big picture, for example, high-quality coffees from Latin American countries generally resemble one another, as do coffees from East Africa and the Arabian Peninsula. And both tend to differ from coffees from the Malay Archipelago: Indonesia, New Guinea, and Timor.

But the notion of generally labeling coffee by country of origin is inevitable and well established. Hence the organization of the next section of this chapter by continent and country. It is well to keep in mind, however, that in tasting coffee, as in thinking about history, the notion of country is no more than a convenient starting point.

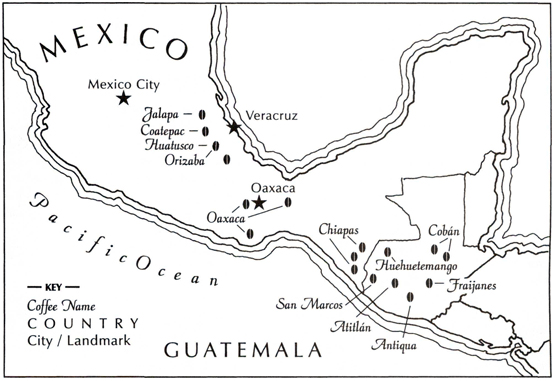

Mexico: Coatepec, Oaxaca, Chiapas

Most Mexico coffee comes from the southern part of the country, where the continent narrows and takes a turn to the east. Veracruz State, on the Gulf side of the central mountain range, produces mostly lowland coffees, but coffees called Altura (High) Coatepec, from a mountainous region near the city of that name, have an excellent reputation. Other Veracruz coffees of note are Altura Orizaba and Altura Huatusco. Coffees from the opposite, southern slopes of the central mountain range, in Oaxaca State, are also highly regarded and marketed under the names Oaxaca or Oaxaca Pluma. Coffees from Chiapas State are grown in the mountains of the southeasternmost corner of Mexico, near the border with Guatemala. The market name traditionally associated with these coffees is Tapachula, from the city of that name, but coffee sellers now usually label them Chiapas. Chiapas produces some of the very best and highest-grown Mexico coffees.

The typical fine Mexico coffee is analogous to a good light white wine—delicate in body, with a pleasantly dry, acidy snap. If you drink your coffee black and prefer a light, acidy cup, you will like these typical Mexico specialty coffees. However, some Mexico coffees, particularly those from high, growing regions in Chiapas, rival the best Guatemala coffees in high-grown power and complexity.

Mexico is also the origin of many of the certified organically grown coffees now appearing on North American specialty menus. These are often excellent coffees certified by various independent monitoring agencies to be grown without the use of pesticides, fungicides, herbicides, or other harmful chemicals.

Coffee from many of the most admired Mexican estates seldom appears on the United States market but is sold almost exclusively in Europe, particularly Germany. Some of these names, should they ever become relevant for the North American aficionado, include Liquidambar, Santa Catarina, Irlandia, Germania, and Hamburgo.

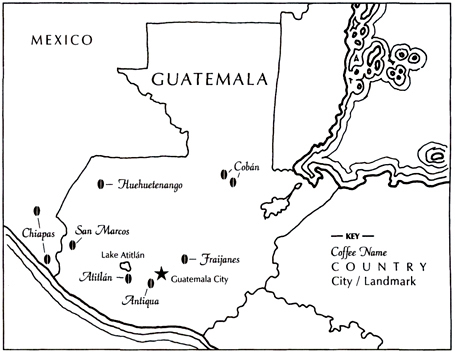

Guatemala: Antigua, Cobán, Huehuetenango, Atitlán, San Marcos, Fraijanes

The highlands of Guatemala produce several of the world’s finest and most distinctive coffees. The mountain basin surrounding the austerely beautiful colonial city Guatemala Antigua produces the most distinguished of these highland coffees: Guatemala Antigua, a coffee that combines complex nuance (smoke, spice, flowers, occasionally chocolate) with acidity ranging from gently bright to austerely powerful. Fraijanes displays similar cup characteristics. Other Guatemala coffees, perhaps because they are more exposed to wet ocean weather than the mountain-protected Antigua basin, tend to display slightly softer, often less powerful, but equally complexly nuanced profiles. These softer Guatemalas include Cobán, admired for its fullish body and gentle, deep, rounded profile, chocolaty and fruity; Huehuetenango from the Caribbean-facing slopes of the central mountain range; and San Marcos coffees from the Pacific-facing slopes. Coffees from the basin surrounding Lake Atitlán in South-Central Guatemala typically offer the same complex nuance as Antiguas but are lighter in body and brighter in flavor.

There are many excellent Guatemalan estates. To name just a small selection: in the Antigua Valley, San Sebastián, La Tacita, San Rafael Urias, Pastores, El Valle, and Las Nubes. In Huehuetenango, Santa Cecilia, Huixoc, and El Coyegual. In the Coban region, Yaxbatz, Los Alpes, and El Recreo. In San Marcos, Dos Marias.

Small-holder coffees predominate in Huehuetenango and Cobán, but transportation difficulties and wet weather during harvest may compromise quality. Perhaps the best small-holder Guatemala coffees come from peasant farmers in the Lake Atitlán basin, who are organized into cooperatives that run their own mills and turn out meticulously prepared coffee. A cooperative near the town of San Juan La Laguna markets its excellent coffee under the poetic name “La Voz que Clama en el Desierto.” This cooperative practices coffee production at the ultimate end of environmental correctness: organically grown in a dense, bird-sheltering, shade canopy of native trees and plants. The coffee is processed with passion and precision, although delays in getting the freshly picked coffee fruit down the mountainside to the cooperative mills sometimes impart a slight, giddily fermented twist to the cup. Atitlán cooperative coffees are a perfect choice for those in search of both cup quality and a coffee grown in exquisite harmony with earth and the aspirations of people on it.

The highest grade of Guatemala coffee is Strictly Hard Bean (SHB). The regionally designated coffees (Antigua, Atitlán, Cobán, etc) are tasted and approved as meeting flavor profile criteria established for these regions by Anacafé, the Guatemalan National Coffee Association. Those coffees that do not meet regional flavor profile criteria are only allowed to be sold as SHB without regional designation.

Generally, Guatemala has preserved more of the traditional typica and bourbon varieties of arabica than many other Latin American growing countries, which may account for the generally superior complexity of the Guatemala cup. Most Guatemala coffee is grown in shade, ranging from rigorously managed shade on large farms to the serendipitous thickets of small growers.

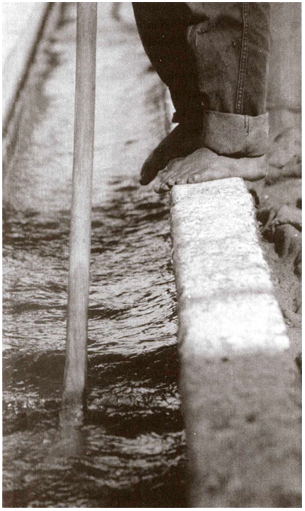

A stage in the wet method of processing coffee fruit in Guatemala. After natural fermentation has loosened the sticky fruit mucilage clinging to the beans, the mucilage is washed off in channels of running water like this one.

El Salvador

Like Guatemala, El Salvador is recovering from a terrifying civil war brought about in part by the now abandoned Cold War policies of the United States. And, as in Guatemala, the terrors of the civil war ironically preserved many of the traditional varieties of arabica like bourbon from replacement with more modern, sun-grown, hybrid coffee varieties.

However, El Salvador apparently lacks the typography that produces the complex, authoritative coffees of the Antigua growing region in Guatemala and Central Costa Rica. Most El Salvadors are soft, ingratiating coffees with relatively subdued acidity, much like many Mexico and Central America coffees grown on ocean-influenced slopes and valleys. Nevertheless, these El Salvador coffees can be fine, if gentle: fragrant and seductive. Occasionally an El Salvador appears that is powerful, deep, and acidy like the finest Guatemalas.

A few El Salvador farms and cooperatives, including Los Ausoles and Larin, grow the intriguing hybrid variety pacamara, a tree that produces a large bean that is a cross between the extremely large-beaned maragogipe and a local strain of the caturra variety called paca. Los Ausoles markets its pacamara coffee under the name Tizapa. From an aficionado point of view, pacamara is a fascinating hybrid because it is superior in cup quality to either of its parent varieties. From a coffee drinker’s point of view, the large bean makes an interesting curiosity and the soft but complex cup gives some sensual support to the conversation-invoking potential of the bean size.

Also making an effective push into the American specialty market is a large cooperative that markets its pleasantly sweet, nutty, certified organic coffee as Café Pepil. Pepil is the name of one of the Native American cultures that dominated El Salvador at the time of the arrival of the Spanish.

The best grade of El Salvador coffee is Strictly High Grown (SHG). Most El Salvador coffee is grown in various degrees of shade.

Honduras: Marcala

Recently Honduras has been plunged into a horrific period of suffering, starting with the almost otherworldly devastation of Hurricane Mitch in 1998 and continuing through the floods and storms of 1999. These events cut off a promising entry of a small number of Honduras growers and exporters into the American specialty market.

Honduras also suffers from having most of its coffees produced by small holders who are forced to perform the fruit removal and drying of the coffee themselves owing to poor coffee infrastructure. These small lots of coffee are then mixed together, producing understandably inconsistent quality. Coffees from the Marcala region near the El Salvador border have the best reputation of Honduras origins. Strictly High Grown is the highest grade.

When Honduras coffees do return to the specialty market, most probably will prove to be rather gentle, low-key coffees of medium body, with occasionally brighter, more acidy coffees from the Marcala region.

Nicaragua: Jinotega, Matagalpa, Segovia

Like Guatemala and El Salvador, Nicaragua too is recovering from the brutality of civil war followed by the ravages of Hurricane Mitch. In the case of Nicaragua, its coffees are only now becoming known again in the United States owing to the long interruption of the Cold War years when Nicaraguan coffee was not allowed to be imported into the United States.

The distinctive genius of some Nicaragua coffees is a round, deep, yet resonant, chocolaty fullness. The typical acidity of Central American coffees makes itself felt but only enveloped inside the almost fatty fullness of the cup. Look for coffees from the Prodocoop cooperative mill in the Segovia region for an example of this subtly distinctive variation on the Central America theme.

Other Nicaragua coffees offer a cup in the more familiar Central America mode: fragrant, complex, with a nut and vanilla bouquet, moderately acidy and medium in body. Jinotega, Matagalpa, and Segovia are the best-known growing regions. Most Nicaragua coffee is shade grown. The highest grade is Strictly High Grown.

Costa Rica: Tres Ríos, Tarrazu, Dota, Herediá, Volcán Poás

Central Costa Rica is one of those classic coffee origins that is respected but not fawned over. Although Costa Rica produces a variety of coffees, those that reach American specialty coffee menus usually are very high-grown Strictly Hard Bean coffees from regions near the capital of San José in the central part of the country: Tarrazu, Herediá, Tres Ríos, Volcán Poás. At best Costa Rica coffees from these regions are distinctive in a way that defies simple, romantic description. When good they are clean, balanced, and resonantly powerful. When ordinary they are clean, balanced, and rather inert.

The relative lack of innuendo in Costa Rica coffees ironically may be owing to the advanced state of the Costa Rican coffee industry. They tend to come from trees of relatively recently selected or developed cultivars of arabica like caturra or catuai and usually are impeccably wet-processed using technically advanced techniques that eliminate the oddities of flavor that derive from traditional or regional variations in processing.

Among estates, La Minita has become particularly prominent owing to the quality of its almost fanatically prepared coffee and the skillful publicity efforts of its owner, William McAlpin. The La Minita coffee appearing in specialty stores is likely to be so labeled: Costa Rica La Minita, La Minita Tarrazu, etc. Bella Vista can be almost as remarkable, although recently it has been available only from Starbucks.

Coffees from the Dota area of Tarrazu are the exact opposite of the classic-at-best, boring-at-worst Costa Ricas. Apparently owing to a local variation in fermenting technique, Dotas walk a thin, wild edge between disturbing overripeness and exciting fruit and chocolate and are a good choice for those who prefer romantic risk to perfection.

Panama: Boquete

Panama is a rising star, an up-and-coming contender among Central America coffee origins. All premium Panama coffees are produced on large, family-owned farms in Chiriquí Province in the western part of the country near the border with Costa Rica. At least five growing regions are clustered around Barú volcano: Boquete (the best known), Paso Ancho (also admired), Volcán, Piedra de Candela, and Renacimiento. The elevations are impressive (3,600 to 5,200 feet, 1,100 to 1,600 meters), the soil volcanic, the wet-processing state-of-the-art. Although some traditional typica and bourbon varieties are grown, most Panama specialty coffee appears to come from caturra (a twentieth-century selection) and the respected hybrid catuai.

Many well-run estates (Lerida, Berlina, La Torcaza, Los Alpes, El Túcan, Las Victorias, Don Bosco, Bajo Mono, Boutet, La Florentina, among others) produce meticulously prepared coffees that range from lively but gently acidy and round to others that are rich, complexly nuanced, and boldly acidy. In short, Panama is a superior Central America wet-processed coffee with all of the range and potential virtues of those coffees.

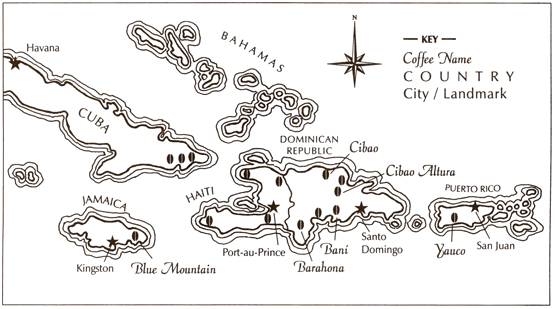

Jamaica: Blue Mountain

The central Blue Mountains of Jamaica are an extraordinary landscape. The higher reaches are in almost perpetual fog, to which the tropical sun gives an otherwordly internal glow, as though the light itself has come down to settle among the trees. The fog slows the development of the coffee, producing a denser bean than the relatively modest growing elevations (3,000 to 4,000 feet) might produce elsewhere. Coffee grown in the Blue Mountains of Jamaica is the world’s most celebrated, most expensive, and most controversial origin.

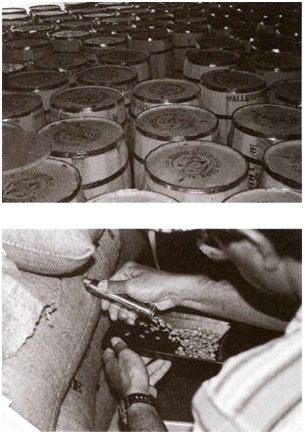

Jamaica Blue Mountain has been an admired coffee since the early nineteenth century when, for a brief time, Jamaica led the world in coffee production. After World War II the British colonial government, alarmed that undisciplined production was on the verge of ruining the Blue Mountain reputation, instituted a rigorous program of regulation and quality control under the leadership of the newly established Coffee Industry Board of Jamaica. After Jamaica achieved its independence from Britain, the new Jamaican government continued that coffee policy, requiring that all Blue Mountain be wet-processed at government-sanctioned mills and dried, dry-milled, cleaned, and graded at centralized facilities.

Protecting the identity of high-priced coffee in Jamaica and Kona, Hawaii. Top, barrels of Jamaica Blue Mountain coffee waiting to be shipped. Bottom, an agricultural official drawing a sample from a bag of Kona coffee waiting State of Hawaii certification.

Volume Increases, Quality Decreases. In the mid-1970s, when I first tasted Jamaica Blue Mountain from a mill that exported a famous mark called Wallensford Estate, it was indeed a splendid coffee, without drama perhaps, but extraordinarily rich, balanced, resonant and complete. In the 1970s and 1980s, however, the Coffee Industry Board began investing in Jamaica Blue Mountain with money provided by Japanese interests. New mills were constructed that use a short-cut version of the wet-processing method called aquapulping or mechanical demucilaging, and volume increased dramatically while quality decreased despite the Coffee Industry Board’s efforts to maintain it.

The famous Wallensford mark now has become close to meaningless: It simply describes coffee wet-processed at a mill that pretty much resembles all of the other government mills. (True, the Wallensford mill is located in the central part of the Blue Mountains, which may give its coffees a slight edge in altitude over coffees produced by some of the other mills.) Most Blue Mountain coffees now are a decent to mildly impressive version of the Caribbean taste profile: fairly rich, soft, with an understated acidity that is sometimes gently vibrant, other times barely sufficient to lift the cup from listlessness.

Blue Mountain Estate Coffees. At this writing a prolonged recession in Japan (Japan supported Jamaica coffee prices by buying Blue Mountain heavily) and a general, worldwide plunge in coffee prices has the Jamaica Blue Mountain industry in trouble. At the same time, the Coffee Industry Board of Jamaica has embarked on an unprecedented experiment by allowing several farmers to wet-process their Blue Mountain on their farms and export their coffees as separate and distinct estate coffees, rather than as generic Blue Mountain. These new estate Blue Mountains include Alex Twyman’s Old Tavern Estate, and the RSW Estates, a group of three family-owned farms that wet-process their coffees at a common mill. All of these estate coffees are processed using the traditional ferment-and-wash technique, rather than the mechanical demucilage method used to process generic Blue Mountain.

I do not have sufficient experience with RSW Estates to evaluate its coffees. However, I am very familiar with Alex Twyman’s Old Tavern Estate Jamaica Blue Mountain and can vouch that it often approaches the original Wallensford Blue Mountain in its combination of gentleness and deep, vibrant power. However, Old Tavern currently suffers from inconsistency: A slight, almost undetectable hardness sometimes haunts its bouillonlike richness. Time will tell whether Old Tavern becomes a consistently exceptional coffee and whether it, the RSW Estate coffees, and more vigorous leadership from Jamaica coffee officials can help lead the Jamaica Blue Mountain industry generally out of its quality doldrums.

Jamaica Blue Mountain’s fame and high prices have encouraged the usual deceptive blender creativity: Blue Mountain blends that contain very little actual Blue Mountain or Blue Mountain–“style” blends that contain no Blue Mountain whatsoever. These coffees may be excellent, but they are not Blue Mountain.

Puerto Rico: Yauco Selecto, Alto Grande

In the nineteenth century, Puerto Rico was one of the world’s leading coffee origins. In 1896, for example, the island was the sixth largest coffee producer in the world. But in the twentieth century coffee apparently became lost in the complex political and economic shuffle that marked Puerto Rico’s passage from agricultural economy and Spanish colony to developing American commonwealth. In the late 1980s, however, a consortium of farmers led by Harvard-educated marketing expert Jaimé Fortuño revived Puerto Rico as a specialty coffee origin.

Puerto Rico Yauco Selecto is produced at elevations above 3,000 feet in the southwestern mountains from trees of the admired bourbon variety and other traditional local Puerto Rican cultivars. At best it is a superb example of the Caribbean taste, soft yet powerful, with a fragrant, fruity sweetness. At this writing Yauco is not what it has been in the recent past, however, with a hard, flavor-dampening edge often insinuating itself into the Caribbean sweetness. Hopefully, quality will pick up again. Other Puerto Rico coffees, including Alto Grande, are only occasionally sold in the American specialty market.

Dominican Republic: Santo Domingo, Cibao, Bani, Ocoa, Barahona

Coffee from the Dominican Republic is occasionally called Santo Domingo after the country’s former name, perhaps because Santo Domingo looks romantic on a coffee bag and Dominican Republic does not. Coffee is grown on both slopes of the mountain range that runs on an east-west axis down the center of the island. The four main market names are Cibao, Bani, Ocoa, and Barahona. All tend to be well-prepared wet-processed coffees. The last three names have the best reputation. Bani leans toward a soft, mellow cup much like Haiti; Barahona toward a somewhat more acidy and heavier-bodied cup, closer to the better Jamaica and Puerto Rico coffees in quality and characteristics.

Haiti: Haitian Bleu

Haiti, which shares the island of Hispaniola with the Dominican Republic, is one of many countries in which coffee has been called upon to help heal the scars of war and alleviate poverty. During the mid-1990s, conditions in Haiti were so dire owing to a United States–led embargo against the prevailing dictatorship that many farmers burned their coffee trees to produce charcoal for sale in local markets. Haiti coffee, another Caribbean origin with a long and distinguished tradition, virtually disappeared from the specialty coffee menu. Decades of disorder had so depressed the quality of this once celebrated origin that few in the coffee world probably even noticed or regretted its absence.

Today, however, with the help of an international development agency, a cooperative of over seven thousand farmers called Cafeieres Natives produces and markets a revived specialty coffee from Haiti trademarked Haitian Bleu. At its best, Haitian Bleu is rich, opulent, and sweetly low-toned, another fine example of the Caribbean cup. It is difficult to control quality with seven thousand participating farmers, however, and Haitian Bleu can be very inconsistent. Nevertheless, if you like rich, full coffees with dry tones well balanced by sweetness, as many American coffee drinkers do, and if you want to make your dollars count to help the Western Hemisphere’s most impoverished farmers, Haitian Bleu is worth trying.

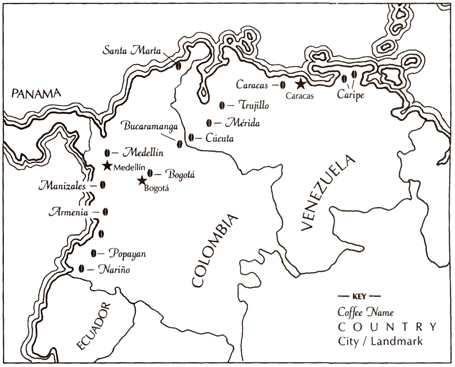

Colombia

Colombia is the paradox of the specialty coffee world. Its 100 percent Colombia campaign, featuring the ubiquitous Juan Valdez, is a model of successful coffee organization and marketing. Colombia remains the only premium single-origin coffee able to compete successfully in the arena of canned supermarket blends. Although it ranks second to Brazil in total coffee production—with about 12 percent of the world’s total coffee production compared to Brazil’s 30 to 35 percent—most of Colombia’s 12 percent is excellent coffee, grown at high altitudes on small peasant holdings, carefully picked, and wet-processed. The Colombian Coffee Federation ranks among the world’s most thorough-going and successful efforts at organizing and supporting smallholder coffee farmers. For seventy-five years the federation has maintained fair, stable coffee prices for the over 550,000 small holder farmers, helped build over 200,000 neat, sturdy little houses for them, constructed over 200 hospitals, and provided an impressive range of other technical and social services.

Nevertheless, for most specialty coffee afficionados and professionals, Juan Valdez is Rodney Dangerfield’s Latin cousin. Colombias carry nowhere near the insider panache of the coffees of Kenya, Guatemala, even of Papua New Guinea and Zimbabwe. Colombia sells well in specialty stores only because it is the sole name on the menu that coffee neophytes recognize.

It would appear that Colombia’s remarkable success at producing large and consistent enough quantities of decent-quality coffee to position it at the top of the commercial market has doomed it as an elite origin. The Colombian Coffee Federation has evolved a system wherein hundreds of thousands of small producers wet-process their coffee on or close to their farms and deliver it to collection points and eventually to mills operated by the federation, where the coffee is sorted and graded according to rigorous national standards. There is an inherent leveling effect in such an arrangement. One farmer’s wet-processing and microclimate may be exceptional and another’s may be mediocre, but both end up mixed in the same vast sea of coffee bags in which the only discriminations are the broad ones imposed by grading criteria. The regional origins famous in the earlier part of the twentieth century—names like Armenia, Manizales, Medellín—are now lost in a well-organized but faceless coffee machine.

Private Mill Colombias. In fact, until recently the only viable specialty coffees to come out of Colombia were developed by private mills and exporters operating largely outside the institutional structure of the coffee federation. These “privates” often supply coffees from single farms and cooperatives or from relatively narrowly defined growing regions. They may offer coffees produced exclusively from traditional, heirloom varieties of Coffea arabica like typica and bourbon, rather than from a mixture of varieties including newer, federation-sponsored hybrid cultivars like the controversial var. colombia.

By contrast, the standard Colombia coffees exported by the coffee federation are distinguished by grade only. Origin is not specified. Supremo is the highest grade, Extra second. The two are often combined into a more comprehensive grade called Excelso. If the only qualifying adjective you see bestowed on a Colombia is a grade name like Supremo or Excelso, you are almost certainly contemplating a standard Colombia from the Colombian Coffee Federation. Nevertheless, these standard Colombias will not all taste the same. Some lots will display much more quality and character than others, and skillful coffee buyers will find them for their customers.

However, if a Colombia coffee is identified by a regional or market name rather than grade name, it may be either a private-mill coffee or one of a new group of specialty coffees developed by the Colombian Coffee Federation. Most of these regionally specific coffees come from traditional cultivars, either bourbon or typica, and most display more character than standard lots of Colombia. Those with the most character and distinction tend to be produced in the southwestern part of the country, in the departments of Nariño, Cauca (market name Popoyan), and Southern Huila.

* * *

At this writing the Colombian Coffee Federation is busy attempting to revive the specialty coffee concept in Colombia by systematically identifying coffees with distinctive cup characteristics and marketing them to specialty coffee buyers as separate regional origins. Given the technical and marketing savvy of the coffee federation and the diversity of the coffee environment in Colombia, I expect this program to be a success.

Colombia coffee at its finest is, like Costa Rica, a classic. No quality is extreme. The body tends to be medium, the acidity vibrant but not overbearing, and the cup lively and nuanced by understated fruit tones.

Venezuela: Maracaibo, Táchira, Mérida, Caripe

At one time, Venezuela ranked close to Colombia in coffee production, but in the 1960s and ’70s, as petroleum temporarily turned Venezuela into the richest country in South America, coffee was relegated to the economic back burner. Today Venezuela produces less than 1 percent of the world’s coffee, and most of it is drunk by the Venezuelans themselves. However, some interesting Venezuela coffees are again entering the North American specialty market.

The most admired Venezuela coffee comes from the far western corner of the country, the part that borders Colombia. Coffees from this area sometime are called Maracaibos, after the port through which they are shipped, and may include one coffee, Cúcuta, which is actually grown in Colombia but may be shipped through Maracaibo. The best-known Maracaibo coffees, in addition to Cúcuta, are Mérida, Trujillo, and Táchira. Mérida typically displays fair to good body and an unemphatic but sweetly pleasant flavor with hints of richness. Táchira and Cúcuta resemble Colombias, with rich acidity, medium body, and occasional fruitiness.

Coffees from the coastal mountains farther east are generally marked Caracas, after the capital city, and are shipped through La Guaira, the port of Caracas. Caripe comes from a mountain range close to the Caribbean and typically displays the soft, gentle profile of the island coffees of the Caribbean.

Regardless of market name, the highest grade of Venezuela coffee is Lavado Fino.

Ecuador

Ecuador produces substantial amounts of coffee but little seems to appear in specialty stores in the United States. By reputation it is a generally unremarkable coffee, with thin to medium body and occasional bright acidity.

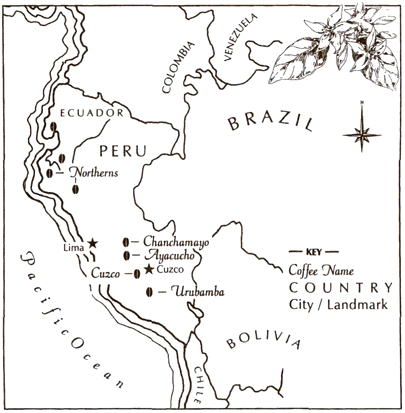

Peru: Chanchamayo, Urubamba

Generally a mildly acid coffee, light-bodied but flavorful and aromatic, Peru is considered a good blender owing to its pleasant but understated character. Peru also is widely used in dark-roast blends and as a base for flavored coffees. But the best Peru coffees are subtly exceptional: light and levitating with a vanilla-nut-toned sweetness that deserves appreciation as a distinctive specialty origin.

Wet-processed coffee from the Chanchamayo Valley, about two hundred miles east of Lima in the high Andes, has the best reputation of the Peru coffees. The Cuzco region, particularly the Urubamba Valley, also produces respected, wet-processed coffee. The highest grade is AAA. Certified organic coffees from cooperatives of small farmers in northern Peru are often excellent, and represent the socially progressive side of speciality coffee at its most admirable.

Brazil: Santos, Bourbon Santos, Estate Brazils

Brazil is not only the world’s largest coffee producer, it is also the most complex. It turns out everything from mass-produced coffees that rank among the world’s cheapest to elegant coffees prized as the world’s finest origins for espresso brewing. In Brazil, fruit is removed from the bean using four different processing methods, and it is not uncommon for all four methods to be used on the same farm during the same harvest.

For one thing Brazil coffee is not is high-grown. Growing elevations in Brazil range from about 2,000 to 4,000 feet, far short of the 5,000-plus elevations common for fine coffees produced in Central America, Colombia, and East Africa. Lower growing altitudes means that Brazil coffees are relatively low in acidity. At best they tend to be round, sweet, and well-nuanced rather than big and bright.

Santos Brazils, Estate Brazils. The most traditional Brazil coffee, and the kind most likely to be seen in specialty stores, has been dried inside the fruit (dry-processed) so that some of the sweetness of the fruit carries into the cup. It also sometimes comes from trees of the traditional Latin American variety of arabica called bourbon. The best of these coffees are traded as Santos 2, or, if the coffee comes exclusively from trees of the bourbon variety, Bourbon Santos 2. Santos is a market name referring to the port through which these coffees are traditionally shipped, and 2 is the highest grade. On specialty coffee menus the 2 is usually dropped, so you will see the coffee simply described as Brazil Bourbon Santos or Brazil Santos.

Some years ago the Brazilian government deregulated the coffee industry, allowing large farms to market their coffees directly to consuming countries without regard to government-mandated grading structures. Consequently, coffees similar to Santos or Bourbon Santos also reach the American market directly from large farms (fazendas). Names of very large fazendas that you may see on specialty menus include Ipanema, Monte Alegre, and Boa Vista, all of which produce excellent coffee. Respected smaller fazendas include Lagoa, Lambari, Fortaleza, Cor-campo, and many others. The farms operated by Ottoni and Sons, particularly Fazenda Vereda, produce very fine coffees. Improving organic coffees are produced by an increasing number of farms, including Fazenda Cachoeira and a farm that markets its coffees as Blue de Brasil.

The premium coffees arriving in the United States from these farms are usually dry-processed or “natural” coffees. However, estate Brazils also may be wet-processed, which turns them a bit lighter and brighter in the cup, or they may be what Brazilians call pulped natural or semiwashed coffees, which have been dried without the skins but with the sticky fruit pulp still stuck to the beans. Typically these pulped natural coffees absorb sweetness from the fruit pulp and are full and sweet in the cup like their dry-processed brethren.

Risks and Rewards of Dry-Processing. When coffee is dried inside the fruit, as most classic Brazil coffees are, lots of things can go wrong. The seed or bean inside the fruit is held hostage, as it were, to the general health and soundness of the fruit surrounding it. If the fruit rots, the coffee will taste rotten or fermented. If microorganisms invade the fruit during that rotting, a hard or medicinal taste will carry into the cup. At the most extreme medicinal end of this taste spectrum are the notorious rio coffees of Brazil, which are saturated by an intense iodinelike sensation that American coffee buyers avoid but which coffee drinkers in parts of Eastern Europe and the Near East seek out and enjoy. In fact, in some years these intensely medicinal-tasting coffees fetch higher prices in the world market than sound, clean-tasting Brazil coffees.

Brazilian Growing Regions. Three main growing areas provide most of the top-end Brazil coffees. The oldest, Mogiana, lies along the border of São Paulo and is famous for its deep, richly red soil and its sweet, full, rounded coffees. The rugged, rolling hills of Sul Minas, in the southern part of Minas Gerais State northeast of São Paulo, is the heart of Brazil coffee country and home of two of the largest and best-known fazendas, Ipanema and Monte Alegre. The Cerrado, a high, semiarid plateau surrounding the city of Patrocinio, midway between São Paulo and Brasilia, is a newer growing area. It is the least picturesque of the three regions with its new towns and high plains but arguably the most promising in terms of coffee quality, since its dependably clear, dry weather during harvest promotes a more thorough, even drying of the coffee fruit.

An Espresso Treasure. The very finest of Brazils are a coffee treasure, so spicy sweet and smooth that even a sugar fanatic can drink them black with pleasure. They particularly come into their own in espresso brewing, which puts a premium on mellow sweetness.

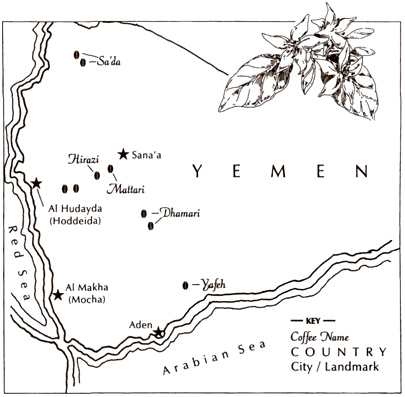

Yemen: Mocha, Mattari, Hirazi, Ismaili, Sanani

Mocha is one of the more confusing terms in the coffee lexicon. The coffee we call Mocha (also spelled Moka, Moca, or Mocca) today is grown as it has been for hundreds of years in the mountains of Yemen at the southwestern tip of the Arabian Peninsula. It was originally shipped through the ancient port of Mocha, which has since been replaced by a modern port and has fallen into picturesque ruins. The name Mocha has become so permanently a part of coffee vocabulary that it stubbornly sticks to a coffee that today would be described more accurately as Yemen or even Arabian.

Complicating the situation are coffees that closely resemble Yemen in cup character and appearance from eastern Ethiopia, near the town of Harrar. These dry-processed Ethiopia Harrar coffees often are sold under the name Mocha or Moka. They are typically lighter bodied than their Yemen namesakes but otherwise very similar.

Still another possibility for confusion derives from the occasional chocolate tones of Yemen Mocha, which caused some enthusiast to tag the name onto drinks that combine hot chocolate and coffee. So Mocha is an old-fashioned nickname for coffee itself, a common name for coffee from Yemen, a name for a similar coffee from the Harrar region of Ethiopia, and the name of a drink made up of coffee and hot chocolate.

The World’s Most Traditional Coffee. True Arabian Mocha, from the central mountains of Yemen, is still grown as it was over five hundred years ago, on terraces clinging to the sides of semiarid mountains below ancient stone villages that rise like geometric extensions of the mountains themselves. In the summer, when the scrubby little coffee trees are blossoming and setting fruit, misty rains temporarily turn the Yemen mountains a bright green. In the fall the clouds dissipate and the air turns bone dry as the coffee fruit ripens, is picked, and appears on the roofs of the stone houses, spread in the sun to dry. During the dry winter, water collected in small reservoirs often is directed to the roots of the coffee trees to help them survive until the drizzles of summer return.

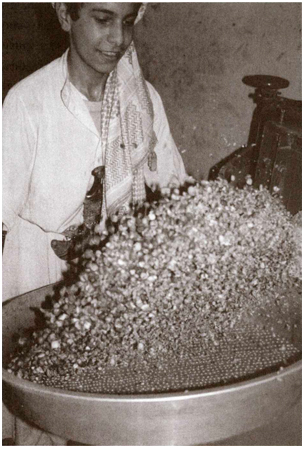

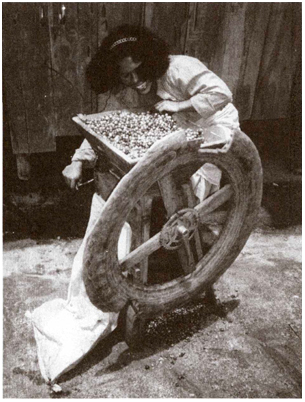

Yemen coffees are processed as they have been for centuries. All Yemen Mochas are dry or natural coffees, dried with the fruit still attached to the beans. After the fruit and bean have dried, the shriveled fruit husk is removed by millstone, which accounts for the rough, irregular look of Yemen beans. I have been told that some of these millstones are still turned by camels or donkeys, although I never managed to witness this spectacle. But even millstones turned by little gasoline engines are fascinating and nostalgic for the coffee historian, since they represent the oldest and most fundamental of coffee technologies.

The husks of the dried coffee fruit, neatly broken in half by the action of the millstones, are used to make a sweet, light drink Yemenis call qishr. The husks are combined with spices and boiled. The resulting beverage is cooled to room temperature and drunk in the afternoon as a thirst quencher and pick-me-up. Yemenis drink roast-and-ground coffee only in the morning, when, after bathing and prayers, they line up at coffeehouses for a quick morning cup of coffee boiled with sugar in Middle Eastern fashion.

Almost all Yemen coffee comes from ancient varieties of Coffea arabica grown nowhere else in the world except perhaps in eastern Ethiopia. Yemenis have scores, perhaps hundreds, of names for their local coffee varieties. Most of these names and the trees to which they refer have never been documented and are identified only within the rich and complex set of oral traditions that make up Yemeni coffee lore. At least one variety is widely recognized (and admired) across Yemen, however: Ismaili, which produces tiny, rounded beans resembling split peas.

Mysterious Market Names. Market names for Yemen coffee are as irregular as the beans themselves. Many names refer both to variety of tree and to growing district. For example, to an outsider it is never entirely clear when a coffee seller says he has an Ismaili coffee available whether he is describing a coffee from the Bani Ismail growing district, beans from the Ismaili variety of coffee tree, or both.

Given that caveat, this much can be said about market names for Yemen coffee. Mattari, originally describing coffee from Bani Mattar, a very high-altitude growing district just west of the capital of Sana’a, is the most famous of Yemen coffees. Despite the fact that most exporters mix true Mattari coffees with other, similar coffees, coffee sold by that name still is likely to be the most acidy, most complex, most fragrantly powerful of Yemen origins. Hirazi, from the next set of mountains west of Sana’a, is likely to be just as acidy and fruity, but a bit lighter in the cup. Ismaili, regardless of whether the name describes cultivar or region, is also likely to be excellent but a bit gentler and less powerful than Mattari. The market name Sanani describes a blend of coffees from various regions west of Sana’a and is typically more balanced, less acidy, and less complex than coffees marketed as Mattari, Hirazi, or Ismaili. Sanani usually includes somewhat lower-grown coffees from districts like Rami.

Winnowing chaff from coffee beans after removing the dried fruit by millstone, Yemen.

History in the Cup. No matter what market name modifies it, Yemen is one of the most distinctive coffees in the world and one of the finest. It literally embodies coffee history. When you drink a Yemen, you are drinking the exact coffee, picked from the same variety of trees, grown on the same terraced fields, dried on the same rooftops, as Sufis drank in Cairo in 1510, as Europeans first discovered in Constantinople, and as Diderot and Voltaire enjoyed in Paris in the eighteenth century.

It also is an excellent alternative for those who wish a coffee grown without chemicals. Yemen Mocha is as organically grown as it was five hundred years ago when the first trees from Ethiopia were established.

When I conduct a coffee tasting with nonprofessionals, the participants almost always prefer Yemen to other samples. The reason: Yemen is acidy but sweet, it is distinctively dry and fruity, and it is satisfyingly rich and full-bodied. Coffee professionals, on the other hand, often criticize Yemen owing to a very faint off-taste that probably derives from an endemic microorganism that the coffee fruit picks up during drying. This aftertaste, a very muted ferment tone, apparently is an inevitable component of the rich, luxurious Yemen flavor package. The similar-tasting coffees from the Harrar region of eastern Ethiopia share it. Those of us who love Yemens either learn to love this odd aftertaste or simply put up with it for the sake of the rest of what this explosively flavorful, historical coffee brings to the cup.

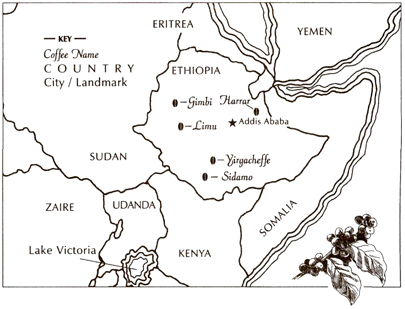

Ethiopia: Harrar, Yirgacheffe, Sidamo, Limu, Jima

Coffee was first developed as a commercial crop in Yemen, but the arabica tree originated across the Red Sea in western Ethiopia on high plateaus where country people still harvest the wild berries. Today Ethiopia coffees are among the world’s most varied and distinctive, and at least one, Yirgacheffe, ranks among the very finest.

All display the wine- and fruit-toned acidity characteristic of Africa and Arabia coffees, but Ethiopias play a rich range of variations on this theme. These variations are in part determined by the processing method. Ethiopia coffees neatly divide into those processed by the dry method (the beans are dried inside the fruit) and those processed by a sophisticated, large-scale wet method, in which the fruit is immediately removed from the beans in a series of complex operations before the beans are dried.

Ethiopia Casual Dry-Processed Coffees. In most parts of Ethiopia dry-processing is a sort of informal, fall-back practice used to process small batches of coffee for local consumption. Everywhere that even a single coffee tree grows, someone will pick the fruit and put it out to dry. I recall driving along a seemingly uninhabited road in western Ethiopia and suddenly coming upon a slice of pavement that had been walled off with a row of rocks to protect a patch of drying coffee! Such informally dry-processed coffee is seldom exported, but simply hulled, roasted, and drunk on the spot or sold into the local market.

Instead, the best and ripest coffee fruit is sold to wet-processing mills, called washing stations, where it is prepared for export following the most up-to-date methods. Only the leftovers, the unripe and overripe fruit, is put out to dry, usually not on roads, but on raised, tablelike mats in front of the farmers’ clay and thatched houses. This dry-processed coffee may reach export markets, but only as filler coffees for inexpensive blends.

Ethiopia Dry-Processed Harrar. The exception to dry-processed coffee’s second-class status in Ethiopia is the celebrated and often superb coffee of Harrar, the predominantly Muslim province to the east of the capital of Addis Ababa. In Harrar, all coffee fruit, including the best and ripest, is put out in the sun to dry, fruit and all. Often, the fruit is allowed to dry directly on the tree. The result is a coffee much like Yemen, wild, fruity, complexly sweet, with a slightly fermented aftertaste. This flavor profile, shared by both Yemens and Ethiopia Harrars, is often called the Mocha taste and is one of the great and distinctive experiences of the coffee world. For this reason Harrar often is sold as Mocha or Moka, adding to the confusion surrounding that abused term. Some retailers cover both bases by calling the Ethiopian version of this coffee type Moka Harrar. (Harrar may be spelled Harari, Harer, or Harar.)

Yirgacheffe and Other Wet-Processed Ethiopias. The first wet-processing mills were established in Ethiopia in 1972, and three decades later more and more coffees in the south and west of Ethiopia are being processed using a sophisticated version of the wet method. The immediate removal of fruit involved in wet-processing apparently softens the fruity, winelike profile of dried-in-the-fruit coffees like Harrars and turns it gentle, round, delicately complex, and fragrant with floral innuendo.

In the wet-processed coffees of the Yirgacheffe region, a lush, deep-soiled region of high rolling hills in southwestern Ethiopia, this profile reaches a sort of extravagant, almost perfumed apotheosis. Ethiopia Yirgacheffe, high-toned and alive with shimmering citrus and flower tones, may be the world’s most distinctive coffee. Other Ethiopia wet-processed coffees—Washed Limu, Washed Sidamo, Washed Jima, and others—are typically soft, round, floral, and citrusy, but less explosively fragrant than Yirgacheffe. They can be very fine and distinctive coffees, however.

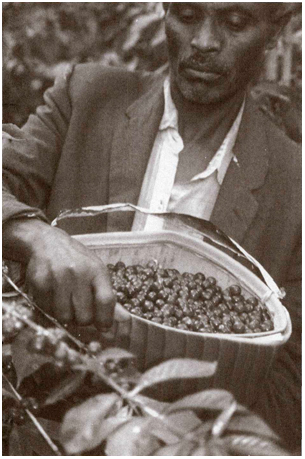

Selective coffee picking, Sidamo region of Ethiopia.

Most Ethiopia coffees are grown without use of agricultural chemicals in the most benign of conditions: under shade and interplanted with other crops. The only exceptions are a handful of wet-processed coffees produced by large, government-run estates in southwestern Ethiopia that make discreet use of chemicals. Harrars and Yirgacheffes in particular are what Ethiopians call “garden coffees,” grown on small plots by villagers using completely traditional methods.

Poorest Country, Richest Coffee Culture. Economically Ethiopia is one of the globe’s poorest countries, but it embodies one of the world’s richest coffee cultures. The Ethiopian coffee ceremony is a communal event practiced across Ethiopia and neighboring Eritrea. It gathers neighbors for an hour or two of food and gossip while the hostess roasts, grinds, brews, and serves coffee and can be one of the most moving tributes to the art of coffee the world has to offer. These ceremonies are often mounted in restaurants and hotels for tourists and visitors. These public, contrived versions of the ceremony may unfold with less authenticity than the countless gatherings carried out in coffee-growing villages, but the reassurance for a coffee lover is how good the coffee always turns out, even when the so-called ceremony is conducted, as it once was for me, in a roadside hotel by a well-dressed bar girl. If there is one culture in the world that thoroughly incorporates the wisdom of coffee in all of its aspects, from seed to cup, that culture is Ethiopia.

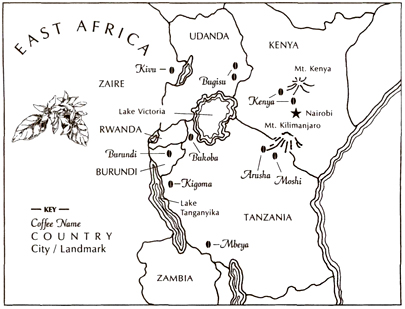

Kenya

Of all contemporary coffee origins, Kenya is doubtless the most universally admired. Coffee growing came late to this mainly tea-drinking nation, introduced in 1900 by the British. When the Kenyans achieved independence, they structured their coffee industry with what, in retrospect, seems admirable foresight. They maintained a technically sophisticated research establishment, made use of the most advanced techniques in fruit removal and drying, developed efficiently run cooperatives of small holders, and organized their export industry around an open auction.

The auction system in particular may be the key to Kenya’s coffee success. The buyer who offers the highest price for a given lot of coffee at the weekly government-run auction gets that coffee. No insider deals can be cut. Samples of lots of coffee up for auction are distributed to licensed exporters, who evaluate them and distribute them to their customers for their evaluation. The exporters bid for the coffees based on their own evaluations and on the preferences of their customers.

This simple, transparent system tends to reward higher quality with higher prices. Kenya coffee growing also has the advantage of consistently high altitudes and whatever imponderables of soil and climate contribute to the heady fruit and wine tones that embellish the best East Africa and Arabia coffees.

The main growing area stretches south from the slopes of 17,000-foot Mt. Kenya almost to the capital, Nairobi. There is a smaller coffee-growing region on the slopes of Mt. Elgon, on the border between Uganda and Kenya. Most Kenya coffee sold in specialty stores appears to come from the central region around Mt. Kenya and is sometimes qualified with the name of the capital city, Nairobi. Grade designates the size of the bean: AA is largest, followed by A and B.

The Kenya Cup. Kenya is both the most balanced and the most complex of coffee origins. A powerful, wine-toned acidity is wrapped in sweet fruit. Although the body is typically medium in weight, Kenya is almost always deeply dimensioned. Sensation tends to ring on, resonating like a bell clap rather than making its case to the palate and falling silent. Some Kenyas display dry, berryish nuances, others citrus tones. The berry-toned Kenyas are particularly admired by some coffee buyers. Finally, Kenya coffees are almost always clean in the cup. Few display the shadow defects and off-tastes that often mar coffees from other origins.

Like many origins, Kenya is under fire from specialty buyers for introducing new hybrid varieties of Coffea arabica that successfully resist disease but, according to the buyers, do not taste as good as the older hybrid varieties, like SL28, on which the Kenya coffee industry was built. Perhaps the criticism is particularly intense in the case of Kenya because we fear losing one of specialty coffee’s greatest treasures.

Uganda: Bugisu

Uganda, situated in the Great Lakes region of central Africa at the headwaters of the Nile, is the original home of Coffea canephora, or robusta. The main part of Uganda coffee production continues to be dry-processed robusta used in instant coffees and as cheap fillers in blends. Uganda also produces excellent wet-processed arabicas, however, virtually all grown by villagers on small plots.

Coffee marketed as Wugar is grown on mountains bordering Zaire along Uganda’s western border. More admired is Bugisu or Bugishu, from the western slopes of Mt. Elgon on the Kenya border. Bugisu is another typically winy, fruit-toned African coffee, usually a rougher version of Kenya.

Burundi: Ngoma

Tucked between Tanzania and Congo in central Africa, Burundi is a relative newcomer on the American specialty stage. Its coffees are produced on small plots by villagers in the northern part of the country and wet-processed at small mills. The coffee is sold at auction to exporters in a system resembling the Kenya auction system. Burundi is still another organically grown coffee owing to the fact that the farmers cannot afford chemicals. Most is grown in full shade. At best, when not spoiled during drying, storage, or transportation, it is a floral and brightly acidy version of the East Africa style.

Tanzania

Most Tanzania arabicas are grown on the slopes of Mt. Kilimanjaro and Mt. Meru, near the Kenyan border. Those from Mt. Kilimanjaro usually are called Kilimanjaro or Moshi; those from Mt. Meru are marked Arusha. The Moshi and Arusha designations derive from the respective main towns and shipping points. Smaller amounts of arabica are grown much farther south, between Lake Tanganyika and Lake Nyasa, and are usually called Mbeya, after one of the principal towns, or Pare, a market name. In all cases, the highest grade is AA, followed by A and B. Owing to tradition, most Tanzania coffee sold in the United States is peaberry, a grade made up entirely of coffee from fruit that produces a single, rounded bean rather than twin flat-sided beans.

Most Tanzania coffees share the characteristically sharp, winy acidity typical of Africa and Arabia coffees. They tend to be medium- to full-bodied and fairly rich in flavor. Other Tanzania coffees may exhibit soft, floral profiles reminiscent of washed Ethiopia coffees.

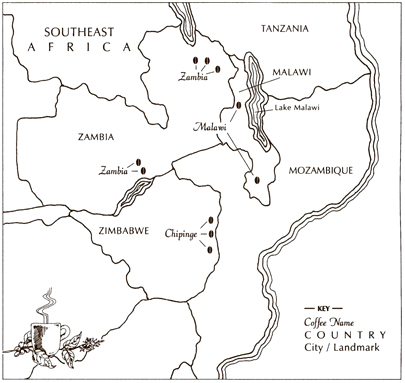

Malawi

Malawi is a relatively small country whose borders meander on a north-south axis between Mozambique and Zambia in southeastern Africa. Although there are many subsistence growers in Malawi organized into cooperatives, Malawi specialty coffees currently reaching North America are produced by estates. These estate Malawis embody the softer, more floral style of East Africa coffee: sweet, delicate, shyly bright.

Zambia

Zambia coffee currently appearing in North America specialty stores is produced by large estates. The most prominent are Terranova and Kapinga. At their very best, these are coffees in the classic East Africa tradition: medium-bodied, floral in aroma, with a wine-toned, resonantly acidy cup.

Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe, formerly Rhodesia, has been exporting an excellent coffee to the United States for some years. It is a wet-processed coffee grown on medium-size to large farms, mainly in the mountainous Chipinge region in eastern Zimbabwe bordering Mozambique. It is still another variant on the acidy, winy-toned coffees of East Africa. Some importers rank Zimbabwe with the best Kenya coffees. Samples I have tasted over the years are not so deeply dimensioned or rich, but it is a fine medium-bodied, complexly wine- and berry-toned, African-style coffee. The best grade is AA. Smaldeel and La Lucie currently are the most prominent estate names.

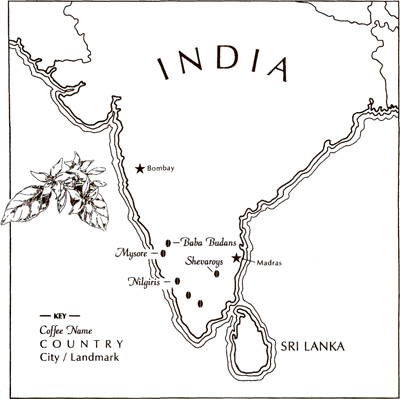

India: Niligris, Baba Budan, Sheveroys, Monsooned Malabar

India has a long and deep coffee culture. Coffee was first brought to India around 1600 by the Muslim pilgrim Baba Budan, who smuggled seed out of Mecca. Coffee growing for export was not started until 1840 by the British, however. India now claims to be the fifth-largest producer of coffee in the world, after Brazil, Colombia, Mexico, and Ethiopia.

Much of India’s production is consumed at home, and India has never achieved a reputation as a fancy coffee origin among North Americans. However, mainly through the efforts of Joseph Johns of Josuma Coffee, a specialized importer of India coffee, India has made some impact on American specialty menus of late.

India has eight main coffee-growing regions, all in the southern part of the country. Those with the highest elevations—Baba Budan, Niligris, and Shevaroys—produce the most admired specialty coffees. They are all wet-processed or washed coffees; Arabica Plantation A is the highest grade.

Currently the most distinguished India coffees to reach the American market come from estates in the Sheveroys district: Pearl Mountain, Arabadicool, and others. These are bright yet gentle coffees, with a buoyant body and an intriguing bouquet of spice notes. The spice is subtle yet explicit: tantalizing suggestions of nutmeg, clove, and cardamon. Since these farms typically grow, process, and store coffee in close proximity to crops of spices, the coffee probably picks up its spice tones during drying and storage in an atmosphere redolent with those scents.

Aside from high-grown estate coffees, India arabica tends to be full, round, sweet, occasionally spicy or chocolaty, but usually a bit listless. Relatively low, growing elevations and the use of disease-resistant hybrids that often have been back-crossed with robusta probably contribute to this full but often inert profile. Nevertheless, India coffees’ sweetness and full body recommend them to espresso blenders, who may use them as a base component in Italian-style blends.

Monsooned Malabar. India’s most unusual coffee is the famous Monsooned Malabar, a dry-processed coffee that has been exposed for three to four months in open-sided warehouses to the moisture-laden winds of the monsoon. The monsooning process swells and yellows the bean, fattens body, and reduces acidity, imparting a heavy, deep, syrupy sweetness to the cup. Unfortunately, many monsooned coffees also acquire a sharp, hard, mustiness that overlays and dampens the attractive sweetness.

Monsooning was originally devised by Indian exporters to produce a cup similar to Old Brown Java coffees, which were similarly transformed in taste by exposure to salt air and moisture in the hulls of wooden sailing ships on the voyage from Java to Europe. If you can find a monsooned coffee that is free of mustiness (a version exported as Coelho’s Gold often is), you may enjoy a cup as sweetly sultry as the name, the history, and the exotic process.

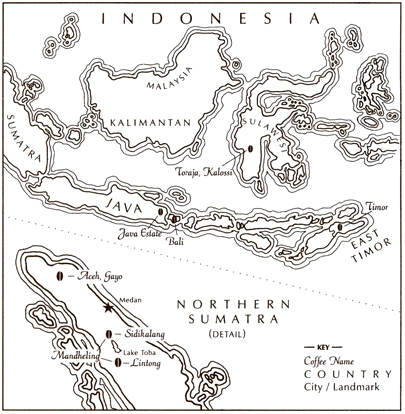

Sumatra: Lintong, Mandheling, Aceh, Gayo Mountain, Kopi Luak

Sumatra is one of the great romance coffees of the world. It is not simply that the Indonesian island of Sumatra embodies a Conradian romance of the unfamiliar. When it is at its best the coffee itself suggests intrigue, with its complexity, its weight without heaviness, and an acidity that resonates deep inside the heart of the coffee, enveloped in richness, rather than confronting the palate the moment we lift the cup.

Sumatra Lintong and Mandheling. This praise applies mainly to the finest of the traditional arabica coffees of northern Sumatra, the best of those sold under the market names Lintong and Mandheling. Lintong properly describes only coffees grown in a relatively small region just southwest of Lake Toba in the kecamatan or district of Lintongnihuta. Small plots of coffee are scattered over a high, undulating plateau of fern-covered clay. The coffee is grown without shade, but also without chemicals of any kind, and almost entirely by small holders. Mandheling is a more comprehensive designation, referring both to Lintong coffees and to coffees grown under similar conditions in the regency of Diari, north of Lake Toba.

Sellers often label Lintong and Mandheling coffees dry-processed. In fact, the fruit usually is removed from the bean by a variety of hybrid methods. The most prevalent is a backyard version of the wet method. The farmers remove the skins from their little crops of coffee cherries immediately after picking using rickety pulping machines ingeniously constructed from scrap metal, wood, and bicycle parts. The skinned, slimy beans are then allowed to ferment overnight in woven plastic bags. In the morning the fruit pulp or mucilage, loosened by the overnight fermentation, is washed off the beans by hand. The coffee (now in its parchment skin) is given a preliminary drying on sheets in the farmer’s front yard. The parchment skin is then removed by machine at a middleman’s warehouse and the coffee is further dried. Finally, the coffee is trucked down to the port city of Medan, where it is dried a third and last time.

I am told that elsewhere in the Mandheling area the mucilage is simply allowed to dry on the bean after the skins have been removed, much as is done with the semiwashed coffees of Brazil. Thereafter the dried mucilage and parchment skin are removed by machine and the coffee subjected to the same two-phase drying, first at the middleman’s warehouse, then at the exporter’s facility in Medan.

Pulping (removing the skins from freshly picked coffee fruit), Mandheling region of Sumatra. The pulping machine is entirely made by hand from improvised components. The fly wheel consists of a slab of truck tire and the axle and handle are constructed from recycled bicycle parts.

Processing and Sumatra Character. I go into these procedures in such detail because it is not clear how much of the unique character of Lintong- and Mandheling-style coffee derives from soil and climate and how much from these unusual processing techniques and the prolonged three-step drying. One thing is certain: These procedures produce a sporadically splendid yet extremely uneven product, and only relentless hand sorting at the exporters’ warehouses in Medan assures that the deep body and unique, low-toned richness of the Lintong/Mandheling origins emerge intact from the distractions of dirty-tasting beans and other taints.

Some admirers of Sumatra enjoy certain of these flavor taints. Earthy Sumatras, which pick up the taste of fresh clay from having been dried directly on the earth, are popular among some coffee drinkers. Musty Sumatras, which acquire the rather hard, mildewy taste of old shoes in a damp closet, are also attractive to some palates.

Sumatra Gayo Mountain, Aceh. Less famous than Lintong and Mandheling are arabicas from Aceh, the province at the northernmost tip of Sumatra. Aceh coffees are grown in the lovely mountain basin surrounding Lake Tawar and the town of Takengon. All are grown in shade and almost all without chemicals.

Processing methods vary widely with Aceh coffees, however, as do flavor profiles. Some are processed by small farmers using the traditional Sumatran backyard washed method. These coffees resemble Lintong/Mandheling coffees, and probably often are sold as such by the Medan exporters.

But the Aceh coffees most likely to reach North American specialty stores come from a large mill near Takengon. The mill’s Gayo Mountain Washed Arabica is processed by a meticulous wet method following international standards and is certified organic by a Dutch agency. Gayo Mountain Washed is sweet and subtly rounded, a higher-toned, lighter-bodied version of the Lintong/Mandheling flavor profile.

The Gayo mill also markets coffees that have been processed by the semidry method, in which the outer skin of the coffee fruit is removed and the beans, still covered with sticky mucilage, are sun-dried. These often excellent coffees offer an attractive compromise between Gayo Mountain Washed and the resonant weight of the traditional Lintong/Mandheling. Such coffees are marketed as Gayo Unwashed. The last term is a bit misleading. (Did the beans forget to take a bath?) A more accurate description might be Gayo Semidry.

The Infamous Kopi Luak. Luak coffee is one of those snicker-rich stories beloved of newspaper writers and party raconteurs. This gourmet curiosity consists (ostensibly) of coffee beans that have been excreted by a smallish animal called a luak or palm civet after the luak has consumed (and digested) the coffee fruit that previously enveloped those beans. Apparently villagers in parts of Sumatra gather the beans from wild luak excrement as well as feed coffee fruit to luaks kept in cages.

Owing to a production method that is clearly limited in volume, Kopi Luak is a rare coffee that demands by far the highest price of any coffee on the world market—currently around $300 per pound retail roasted.

Note that the luak-assisted method of picking and processing coffee is not so outlandish as it at first may sound. Presumably the luak, like any good coffee picker, chooses only ripe cherries to eat. And recall that in the classic wet method of coffee preparation, one step involves allowing natural enzymes and bacteria to literally ferment or digest much of the fruit from the beans.

Although the odor kopi luak produces while roasting dramatically reminds us of its intestinal journey from fruit to bean, the taste in the cup does not. The kopi luak I have tasted is a rather pleasant, low-key, full-bodied, earthy Sumatra coffee.

As for authenticity, I suspect that, amazing as it sounds, most kopi luak is actually produced as advertised. The beans in the lots I have examined are irregular in size and shape, have little nicks and nibbles taken out of them, and seem saturated with intestinal nuance rather than simply rubbed in it. Nevertheless, only the luak knows.

For those well-heeled gastronomical adventurers interested in sampling a luak-prepared coffee, see Sending for It.

Sulawesi or Calebes: Toraja, Kalossi

The Indonesian island of Sulawesi, formerly Celebes, spreads like a huge four-fingered hand in the middle of the Malay Archipelago. The Sulawesi coffee most likely to be found in specialty stores today comes from a mountainous region near the base of the southwestern finger of the island, north of the port of Ujung Padang. The region and the coffee, Toraja, are named after the colorful indigenous people of the region. The coffee is also called Kalossi, after a regional market town.

Whether we call it Sulawesi Toraja or Celebes Kalossi, coffee from this region can range from a plantation-grown, wet-processed coffee with a smooth, vibrant, but relatively low-acid, medium-bodied profile to small-grower coffees that resemble the Mandheling coffees of Sumatra both in virtues (when they are good they are deep, resonant, and pungently complex in the lower registers) and in vices (off-tastes range from earth through musty hardness to an odd stagnant water or pondy taste).

Java: Estate Arabica

The Dutch planted the first Coffea arabica trees in Java at the beginning of the eighteenth century; and before the rust disease virtually wiped out the industry, Java led the world in coffee production. Most of this early acreage has been replaced by disease-resistant robusta, but under the sponsorship of the Indonesian government, arabica has made a modest comeback on several estates originally established by the Dutch at the turn of the century and situated in the dramatic mountains of East Java. In many of these estates the original machinery the Dutch introduced is still in use, maintained perfectly and as neat as a museum display but infinitely more useful.

Java coffees share some of the low-key vibrancy of the best Sumatra and Sulawesi coffees but tend to be lighter, cleaner, and brighter in the cup owing to having been subjected to sophisticated wet-processing and drying methods on large farms. At best they can be astoundingly sweet, buoyantly fragrant, and alive with nut, spice, and vanilla tones. At worst they can display hardness or mustiness owing to the same moisture-interrupted drying that plagues all Indonesia coffees. Nevertheless, a really fine Java is a coffee treasure: restrained in acidity, yet light-footed, spirited, and complex with nuance.

Of the four revived “old” estates that provide most of the good Java arabica—Jampit (or Djampit), Blawan, Kayumas, and Pancur—Jampit and Blawan are the most likely sources of the Java coffee in American specialty stores.

Old Government, Old Brown, or simply Old Java describe Java arabica that has been held in warehouses for two to three years. Such matured coffee turns from green to light brown, gains body, adds pungency, and loses acidity. Old Java was a celebrated gourmet coffee until it disappeared from the market after World War II. It has been revived, although it remains difficult to obtain in the United States. A somewhat similar taste is offered by aged Sumatra and India Monsooned Malabar coffees.

Timor: East Timor

Timor is another do-good, feel-good coffee that is gradually becoming taste-good as well. As any newspaper-reading adult knows, over the decades of the 1980s and ’90s, East Timor—a former Portuguese colony—underwent a bloody war of resistance to Indonesian occupation, and eventually, at the end of the 1990s, a brief but even bloodier spasm that led to independence from its much larger neighbor. During the 1990s, international assistance organizations helped the East Timorese revive their once famous coffee industry. Like most small-holder coffees from the Malay Archipelago, East Timor coffees are grown without chemicals, but Timors have the advantage of being internationally certified as organic. They are wet-processed at recently established wet mills or washing stations. Buying a Timor coffee at this moment in history means making a small but valuable gesture of support for one of the many peoples of the world caught up in sectarian and political conflict.

In terms of taste, most current versions of Timor are typical for small-holder, wet-processed coffees from the islands of the Malay Archipelago: low-key, sweet, with a musty pungency that can range from soft and intriguing to hard and oppressive. However, the very best and cleanest-tasting Timors can be extraordinary: full, round, smooth, sweet, and deliciously cocoa-toned. These coffees, already promising, may continue to improve as the first decade of the new century unfolds.

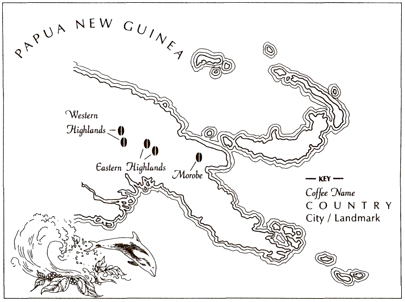

New Guinea: Papua New Guinea

Coffee labeled New Guinea comes from Papua New Guinea, often abbreviated PNG, which occupies the eastern half of the island of New Guinea. Like Indonesia coffees, New Guineas come in two versions: estate coffees that have been meticulously wet-processed in large-scale facilities and smallholder, peasant coffees that usually are wet-processed by the farmers using the simplest of backyard methods.

Most New Guineas sold in North American specialty stores are estate coffees. Most prominent are Sigri, grown in Western Highlands Province near the town of Mount Hagen, Madan, also in Western Highlands Province, and estate coffees from the Eastern Highlands Province exported as Arusafa or Arona.

Depending on year and harvest, Sigri, Arona, and other New Guinea estate coffees range from pleasant to splendid, at best displaying the authority of a high-grown coffee together with the transparency of a carefully wet-processed coffee while retaining the fragrant, low-key luxuriousness characteristic of all coffees of the Malay Archipelago.

Papua New Guinea small-holder coffees often are certified organically grown. They share the problem faced by all small-holder coffees worldwide. If hundreds or thousands of smallholders do their own wet-processing and drying, quality is erratic. Many of these New Guineas arrive in North America musty, hard-tasting, earthy, or fermented. When they are clean-tasting, however, they too express the coffee genius of the Pacific: low-key, vibrant, luxuriously deep. Efforts are being made to control the processing and grading of some of these coffees and establish them as recognized origins. Village Premium Morobe from Morobe Province in the East-Central part of the country represents one of these efforts.

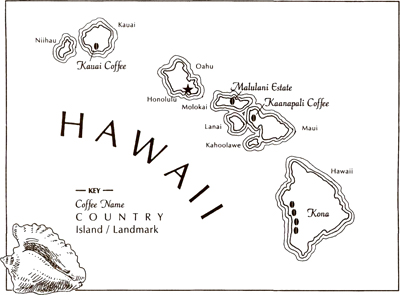

Hawaii: Kona, Kaanapali Coffee, Malulani Estate, Kauai Coffee

Hawaii Kona. The tiny Kona growing district on the southwest coast of Hawaii, the “Big Island” of the Hawaiian chain, produces the most famous and the most traditional of Hawaiian coffees. Entirely handpicked, wet-processed, and from trees of a splendid local strain of typica called Guatemala, Kona is grown on clusters of tiny farms above the Pacific on the lower slopes of Mount Hualalai and Mauna Loa.

The coffee trees are shaded by a cloud cover that appears regularly most afternoons, followed by tourist-discouraging drizzles that often escalate into downpours. The combination of regular rain and cloud cover, the temperature-moderating influence of the Pacific, and very porous soil (sometimes the trees grow straight out of the volcanic rubble) seems to mimic the effect of higher growing altitudes. Although grown at altitudes of 800 to 2,500 feet, very low for arabica, Kona often displays the powerful acidity of much higher-grown coffees.

But it is the gently acidy, fragrant, sometimes wine- and fruit-toned cup of the more typical Konas that made Kona’s reputation as one of the world’s premier coffee origins. In the late 1990s, the soft, aromatic cup, tourist-inspired demand, limited supply, and palms-and-sand romance made Kona the highest-priced coffee in the world, with prices exceeding even those attracted by Jamaica Blue Mountain.

Kona Deceptions and Evasions. At this writing Kona prices have moderated somewhat, but the extremely high prices paid for Konas in the 1990s apparently encouraged one mill owner and supplier to sell Costa Rica and Panama coffees in Kona bags. After a few years of successful deceit he was uncovered and indicted for fraud. The resulting scandal shook the little world of passionate, outspoken Kona growers and mill owners. The end result seems to be positive, however, as the growers work with authorities toward clearer control of the Kona coffee identity.

Young girl helping with family coffee picking in the Kona district of Hawaii.

However, retail sales of Kona coffee continue to be rife with dubious marketing practices. Commercial roasters produce Kona-style coffee, Kona-blend coffee, and Hawaiian hotels brew coffee vaguely labeled Kona that probably consists in large part of (often low-grade) Central America beans. In fact, it is difficult to find a good cup of Kona coffee in Kona, and flat-out impossible in hotels. The colorful bags of Kona coffee sold in Hawaiian supermarkets and airport gift stores are almost always poor quality and stale. Tourists who visit Kona often do come across that one splendid cup, however, and driven by its fragrant memory, plus recollections of the warm air insinuating itself under their newly purchased aloha shirts and muu-muus, spend the next six months trying to find a comparable coffee experience through mainland supermarkets and specialty stores. Most, I suspect, give up and buy something else.

Buying and Visting Kona. One way to enjoy a good, bona-fide Kona on the mainland is to find a roaster who sells a Kona from a single, designated estate, and who does not destroy it by roasting it too dark. If there is no one who fits that description in your area, consult Sending for It. An even better way to buy Kona coffee is to visit Kona in person, find an estate or mill that produces a coffee you like, and arrange to buy that coffee, custom-roasted, on a regular basis by mail.

Visiting Kona farms and mills can be a delight. The current Kona coffee industry largely was founded by Japanese immigrants fleeing the regimentation of work at the large sugar plantations. They established tiny family farms in the rugged countryside, one of which, the D. Uchida Farm, has been restored for visitors by the Kona Historical Society. The ongoing theme of individualism and independence was given a boost in the 1960s and ’70s by back-to-the-land hippie types from the mainland, who settled in to grow coffee next to the Hawaiians and Japanese. Today, you can arrange tours, led by the owners themselves, of tiny farms that produce excellent coffee or visit the wonderful Bayview Farms or Greenwell mills, where from late August to early December you can watch coffee being fastidiously wet-processed.

“Other Island” Hawaiis: Maui, Molakai, Kauai. Today, Kona is no longer the only coffee grown in Hawaii. Visitors to the “other” major coffee-growing islands—Maui, Molokai, and Kauai—now encounter an entirely different coffee spectacle. In place of Kona’s family plots shoehorned in among rocks and rusting cars, long, regular lines of coffee trees undulate like gleaming dark-green hedges over low coastal plains where sugar and pineapple once grew. Rather than isolated groups of pickers balancing their way over rocks, ingenious harvesting machines roll across the nearly flat terrain, coaxing ripe cherries off the trees with hundreds of fiberglass rods vibrating through the branches like tireless fingers. The soil is deep and red, and rainfall, less frequent than in Kona, is supplemented by meticulously managed drip-irrigation systems.

These coffee farms—Kaanapali Coffee with 450 acres on Maui, Malulani Estate with 460 on Molokai, and Kauai Coffee with an astonishing 4,000 on Kauai—are revivals of earlier efforts to grow coffee on a commercial scale on the coastal plains of Hawaii. In the nineteenth century, these coffee farms gave way to the more profitable crops of sugar and pineapple, and coffee growing survived only in rugged Kona, where the rocky terrain discouraged large-scale agriculture.

Today, however, cheap-labor competition from other parts of the world has shut down the less productive of the big pineapple and sugar plantations, and growers and the state of Hawaii are scrambling to find replacement crops that will prevent rural Hawaii from turning exclusively into a playground for tourists and a bedroom community for hotel maids and helicopter tour operators.

Experiment and Innovation. Coffee is one such crop. Coffee romantics may entertain existential attitude problems with these highly technified coffees and their corporate sponsors. For some afficionados, however, the experiment and innovation they represent can be as engaging as Kona’s tradition. All three farms are among world leaders in the effort to maximize quality and offset extremely low growing altitudes through superior processing and seed selection.

All have succeeded to some degree. Pioneer Mill, just outside Lahaina, markets its excellent Kaanapali Estate coffees by botanical variety: moka or mocha, a very old, traditional variety that arrived in Hawaii from Yemen via Brazil; yellow caturra, a more recent selection; red catuai, a good hybrid; and the traditional Kona strain of typica. All are subtly different. The typica has proven to be something of a failure in the Maui growing conditions, but any of the other three varieties can produce oustanding coffee in any given crop year. The moka produces a particularly interesting cup. Kaanapali offers it roasted and packaged as (of course) Maui Gold.

All Molokai coffee is grown at the Coffees of Hawai’i plantation in the central part of the island at around 850 feet. Most comes from trees of the hybrid (but admired) red catuai variety. The wet-processed Malulani Estate and the dry-processed Moloka’i Muleskinner coffees are medium-bodied, sweet, low-acid coffees with complex, attractive bouquets that often include unusual herbal tones.

Kauai Coffee produces a highly selected coffee called Kauai Estate Reserve from trees of the hybrid yellow catuai and the typica varieties. These are consistent, agreeable coffees that will please those who prefer a full-bodied, sweet, low-acid cup.

Maragogipe (Elephant Bean)

Maragogipe (also called elephant bean) is a variety of arabica that produces an extremely large, rather porous bean. It is a mutant that spontaneously appeared in Brazil, almost as though the giant of Latin America thought regular beans were too puny and produced something in its own image. It was first discovered growing near the town of Maragogipe, in the northeastern state of Bahia. Subsequently it has been carried elsewhere in Latin America and generally adopts the flavor characteristics of the soil to which it has been transplanted.