is the average velocity; and t is time. When the motion is vertical, we often use y instead of x for displacement.

is the average velocity; and t is time. When the motion is vertical, we often use y instead of x for displacement.

After Chapter 1.6, you will be able to:

Objects can undergo only two types of motion—that which is constant (with no acceleration) or that which is changing (with acceleration). If an object’s motion is changing, as indicated by a change in velocity, then the object is experiencing acceleration, and that acceleration may be constant or itself changing. A moving object that experiences constant acceleration presents a relatively simple case for analysis. The MCAT tends to restrict kinematics problems to those that involve motion with constant acceleration.

In linear motion, the object’s velocity and acceleration are along the line of motion, so the pathway of the moving object continues along a straight line. Linear motion does not need to be limited to vertical or horizontal paths; the inclined surface of a ramp will provide a path for linear motion at some angle. On the MCAT, the most common presentations of linear motion problems involve objects, such as balls, being dropped to the ground from some starting height.

Falling objects exhibit linear motion with constant acceleration. This one-dimensional motion can be fully described by the following equations:

where x, v, and a are the displacement, velocity, and acceleration vectors, respectively; v0 is the initial velocity;

is the average velocity; and t is time. When the motion is vertical, we often use y instead of x for displacement.

is the average velocity; and t is time. When the motion is vertical, we often use y instead of x for displacement.

When dealing with free fall problems, you can choose to make down either positive or negative. However, for the sake of simplicity, get in the habit of always making up positive and down negative.

To demonstrate the typical setup of a kinematics problem on the MCAT, we will consider

an object falling through the air. For now, we will assume air resistance to be negligible,

meaning that the only force acting on the object would be the gravitational force

causing it to fall. Consequently, the object would fall with constant acceleration—the

acceleration due to gravity

—and would not reach terminal velocity. This is called free fall. Under these conditions of a free falling object that has not reached terminal velocity, which are typical for Test Day, we could analyze the fall,

using the relevant kinematics equations.

—and would not reach terminal velocity. This is called free fall. Under these conditions of a free falling object that has not reached terminal velocity, which are typical for Test Day, we could analyze the fall,

using the relevant kinematics equations.

Let’s now consider what happens when air resistance is not negligible. Air resistance, like friction, opposes the motion of an object. Its value increases as the speed of the object increases. Therefore, an object in free fall will experience a growing drag force as the magnitude of its velocity increases. Eventually, this drag force will be equal in magnitude to the weight of the object, and the object will fall with constant velocity according to Newton’s first law. This velocity is called the terminal velocity.

The amount of time that an object takes to get to its maximum height is the same time it takes for the object to fall back down to the starting height (assuming air resistance is negligible); this fact makes solving these problems much easier. Because you can solve for the time to reach maximum height by setting your final velocity to zero, you can then multiply your answer by two, getting the total time in flight—as long as the object ends at the same height at which it started. Because the only force acting on the object after it is launched is gravity, the velocity it has in the x-direction will remain constant throughout its time in flight. By multiplying the time by the velocity in the x-direction, one can find the horizontal distance traveled.

Projectile motion is motion that follows a path along two dimensions. The velocities and accelerations in the two directions (usually horizontal and vertical) are independent of each other and must, accordingly, be analyzed separately. Objects in projectile motion on Earth, such as cannonballs, baseballs, or bullets, experience the force and acceleration of gravity only in the vertical direction (along the y-axis). This means that vy will change at the rate of g but vx will remain constant. In fact, on the MCAT, you will generally be able to assume that the horizontal velocity, vx, will be constant because we usually assume that air resistance is negligible and, therefore, no measurable force is acting along the x-axis.

Note that gravity is in bold, indicating it has a vector value. Gravity is unique in that it is used as both a constant and as a vector in calculations. Though gravity is not always bolded, you should recall for Test Day that gravity has a direction.

Inclined planes are another example of motion in two dimensions. When working with an inclined plane question, it is often best to divide force vectors into components that are parallel and perpendicular to the plane. Most often, gravity must be split into components for these calculations. These components can be defined as:

where Fg,|| is the component of gravity parallel to the plane (oriented down the plane), Fg,⊥ is the component of gravity perpendicular to the plane (oriented into the plane), m is the mass, g is acceleration due to gravity, and θ is the angle of the incline. Otherwise, the same kinematics equations can be used in these problems.

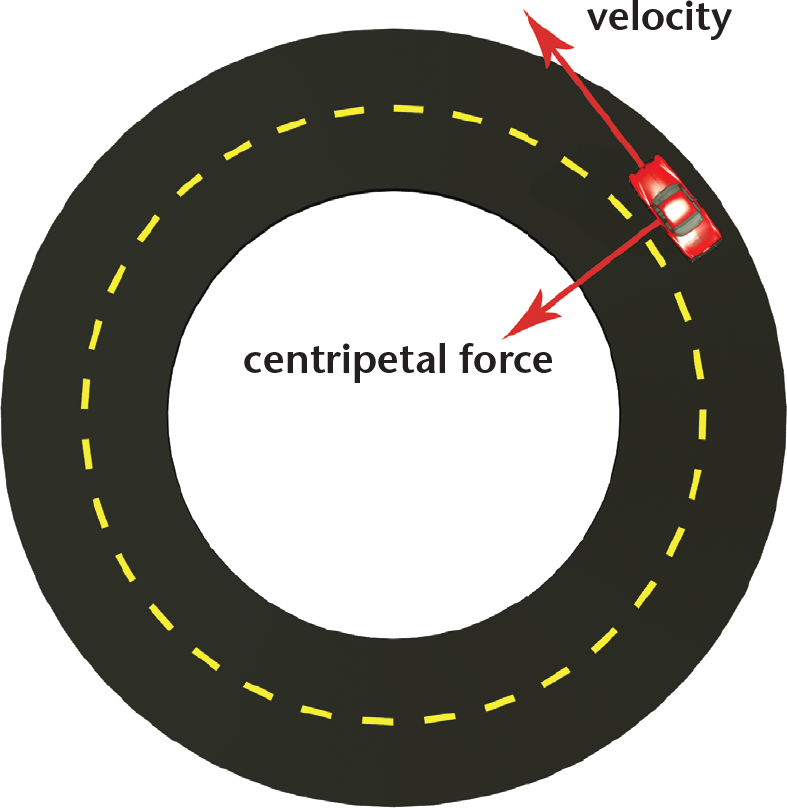

Circular motion occurs when forces cause an object to move in a circular pathway. Upon completion of one cycle, the displacement of the object is zero. Although the MCAT focuses on uniform circular motion, in which case the speed of the object is constant, recognize that there is also nonuniform circular motion.

In uniform circular motion, the instantaneous velocity vector is always tangent to the circular path, as shown in Figure 1.9. What this means is that the object moving in the circular path has a tendency (inertia) to break out of its circular pathway and move in a linear direction along the tangent. It is kept from doing so by a centripetal force, which always points radially inward. In all circular motion, we can resolve the forces into radial and tangential components. In uniform circular motion, the tangential force is zero because there is no change in the speed of the object.

As a force, the centripetal force generates centripetal acceleration. Remember from the discussion of Newton’s laws that both force and acceleration are vectors and the acceleration is always in the same direction as the net force. Thus, it is this acceleration generated by the centripetal force that keeps an object in its circular pathway. When the centripetal force is no longer acting on the object, it will simply exit the circular pathway and assume a path tangential to the circle at that point. The equation that describes circular motion is

where Fc is the magnitude of the centripetal force, m is the mass, v is the speed, and r is the radius of the circular path. Note that the centripetal force can be caused by tension, gravity, electrostatic forces, or other forces.