Cesar favorite Rin Tin Tin (photo credit 1.1)

The television set was an old black-and-white Zenith made of plastic that was supposed to look like wood. When you walked into our Mazatlán apartment, you could hear it before you could see it as you walked down a narrow hallway into the living room with a floor of large black-and-white tiles and a couch against one wall. My mother loved to watch her telenovelas—the daily soap operas that were so popular in Mexico. My sister loved the program Maya, which was about an elephant. But me? I had only two favorites: Lassie and Rin Tin Tin.

I still remember the way the Rin Tin Tin television show opened. Over a distant shot of a low-lying fort set in a cradle of mountains somewhere in the American West, there came the sound of a bugle playing reveille. At the sound of the call, American cavalry officers in Civil War–era uniforms rushed from their posts inside Fort Apache to fall into formation. Then there was a cut—the one I always waited for—to a shot of a magnificent German shepherd dog, sitting stoically on a rooftop, his ears pointed high, on alert to the bugle call. When Rusty, a little boy, joined the formation line, Rin Tin Tin barked, leapt off the rooftop, and got into the line of soldiers, just as if he were a soldier himself. By the end of the opening credits, I was filled with excitement and anticipation, wondering what incredible adventure Rusty and Rin Tin Tin would face this week.

Then there was Lassie. None of the dogs on my grandfather’s farm looked anything like Lassie, with her downy cream-and-white-colored coat and her elegant, pointy nose. Our dogs had raggedy coats and muddy faces, but Lassie was always meticulously groomed. Every week Lassie’s boy owner, Timmy, would get into some sort of trouble, but Lassie would never fail to save her master and help Timmy’s parents teach him a life lesson, all within the span of one thirty-minute show.

By the time I saw Lassie and Rin Tin Tin on television, I was nine or ten years old and already entranced with dogs. From as early as I can remember, I was fascinated by, drawn to, and in love with the packs of working dogs that lived with us on my grandfather’s farm in Sinaloa. They weren’t pretty like Lassie or obedient like Rin Tin Tin, but sometimes I felt more a part of them than I did my human family. I never tired of just watching them—the way they interacted and communicated with one another; the way the mothers so effortlessly but firmly raised the pups; and the way they managed to solve disputes with each other quickly and cleanly, usually without even fighting, then move on to the next thing without bitterness or regret. Perhaps in some way I envied the clear and simple rules of their lives compared with the complexity of the human interactions in my own close but sometimes troubled family. All I knew then, however, was that dogs fascinated me, took me out of myself, and made me want to spend every spare minute learning everything I could about them.

Then Lassie and Rin Tin Tin came into my life through television, and I began to wonder if there wasn’t something about dogs I was missing. You see, at first I was totally fooled by these professional performing dogs. As a father, I used to watch my son Calvin watching kung fu movies on television when he was younger, and I could see by the look in his eyes that he believed the guys were actually fighting each other. He didn’t realize that the fight was choreographed by a stuntman behind the scenes. Well, I was the same way in my beliefs about Lassie and Rin Tin Tin. As primitive as television may have been back then, it did a great job convincing a naive little Mexican boy that there were amazing magical dogs in America that were born being able to communicate with humans, march in the army, and always manage to save the day. Before I even knew that there was a trainer behind the scenes, signaling to Rin Tin Tin to jump off the roof, I got it into my head that somehow, someday, I just had to get to America to meet these amazing dogs that could talk to people, leap over fences, and get mischievous little boys like me out of the trouble we were always getting into!

I think I believed Lassie and Rin Tin Tin did the things they did all on their own because the dogs on our farms seemed to do everything we wanted of them without being told or coerced by us to do it. They would naturally follow my grandfather out into the field and help him corral the cows. They would naturally accompany my mother or sister along the road, as guides and escorts. We didn’t reward them with food every time they followed us across the river or when they barked to alert us of a predator in the area. We did ultimately reward them—but always at the end of the workday, with our leftover meat or tortillas. So I already knew dogs that seemed to be able to communicate with people. To my mind, Lassie and Rin Tin Tin were just a cut above that.

By the time I realized that Rin Tin Tin and Lassie were specially trained dogs, I was a few years older and living with my family in the city of Mazatlán, always wishing for the weekends when I could go back to my grandfather’s farm and be with nature and the animals again. Instead of being disillusioned by the discovery that humans were manipulating those dogs’ behaviors, I was even more excited. You mean, there are people who can make their dogs do these things? How? What are their secrets? It became even clearer in my mind that I would have to get to America as soon as possible to learn from the Americans about creating these amazing behaviors in dogs.

One weekend when I went back to my grandfather’s farm I decided to see if I could teach some of the dogs there how to do specific behaviors. First, I tried to teach the dogs to jump on command. I started with my leg. I’d stick it out in front of me and hold a ball right on the other side. When they’d go over my leg to get it, I’d make the sound “Hup!” Gradually I raised my leg higher and higher until they were jumping right over it. Within the span of a day or two, I could make the dogs jump over my back when I bent down and said, “Hup!”

These dogs were already conditioned to respond to what humans needed from them—not in a “trained” way, but as part of doing their job. And it was a job they wanted to do, because it challenged them and fulfilled their need for a purpose in life. Doing their job was also the way they survived from day to day. We didn’t use leashes for our dogs on the farm. I couldn’t imagine a dog on a leash. Other than every once in a while when my grandfather would get the old rope from the barn to do something like get a donkey out of a ditch, I didn’t know what a leash was until I moved to the city and saw rich people walking their dogs on leashes.

Because of their lifestyle, my grandfather’s dogs naturally wanted to follow me, and they naturally wanted to please me. When the dogs were in a playful state, I caught the energy of that moment and used it to create something new. And they didn’t ask for anything in return except, “What are we going to do with our time?” I learned that I could teach them how to crawl on the ground just by encouraging them verbally and letting them imitate me crawling. Dogs are great at copying behavior—that’s one of the many ways in which they learn from one another when they are pups. And dogs’ brains crave new experiences. If a dog finds what you’re doing interesting, and he is interested in you, and it’s a challenge for him, he naturally wants to be a part of it. The learning experience, the figuring it out, becomes such a thrill to a dog when it’s fun.

Every weekend at the farm I’d try to teach the dogs a new behavior. I wasn’t using food rewards to get this behavior—that strategy wasn’t yet in my mental tool kit. But the dogs wanted to be with me and wanted to do what I wanted. When you have a dog that is eager to do things for you, he doesn’t need food rewards. And to make him eager to do things for you, you have to motivate him with something he wants. What I was offering these dogs was a challenge, plus the entertainment value of it all. It was fun for me, and it was fun for them—an overall positive experience for all of us. By the end of a few weeks I could get them to jump over me, crawl under me, and jump up and give me five. The dogs were happy to be doing it. And with verbal encouragement and just my general enthusiasm, I let them know very clearly how happy I was that they were doing it for me. The outcome was a deeper bond between us.

To me, that was the whole point. Ultimately, you want your dog to do things for you just because you love him. And he loves, respects, and trusts you.

My quick and easy experiences training the farm dogs to do simple behaviors encouraged me to learn more about training, any way I could. It was obvious that it might be a very long time before I’d be able to go to America to meet the magical dogs and their trainers.

When I was a teenager, I learned of a man in Mazatlán who was the only person I’d ever heard of who called himself a professional “dog trainer.” He was from Mexico City, and he would train dogs to do tricks for performances. That was the first time I saw, from behind the scenes, how a dog can fake getting shot. The guy would fire off a gun, and the dog would fall down. I was fascinated by the hand signals and other cues the man used to get the dog to do the behaviors. For the first time, I also saw someone using verbal commands (“sit,” “stay,” “come”). On the farm, it hadn’t occurred to me to use human words (in my case Spanish words) to get a dog to do something. It was interesting to see a dog responding to human language as if he were a person who actually understood what the words meant.

I was intrigued by how this man accomplished all this and asked him if I could volunteer to clean his kennels and help him, sort of like an apprentice. It was the first opportunity I’d had to learn from someone I thought was a real professional.

Meeting this man and seeing him work behind the scenes was my first experience of being totally disillusioned by a dog trainer. Unlike the dogs on the farm, this man’s dogs did not seem particularly excited about doing the things their trainer wanted them to do. The man was very forceful. As I watched him pry open one dog’s mouth and tape in the item he wanted the dog to carry, I became extremely uncomfortable. I left that situation very quickly because even though I had no formal training, I knew in my gut that there had to be a better way.

I was a pretty trusting kid, I was naturally honest, and I tended to believe what people said to me. I didn’t understand then that there are people who are in the animal business not because they love animals. Sometimes they are just in it for the money. My next two experiences in trying to educate myself as a dog trainer taught me that lesson the hard way.

The next man I met who said he was a trainer claimed that he had trained animals—including dogs—in America, the land of the magical dogs. He worked in the city where I was born, Culiacán, so I went to see if I could learn from him. But when I arrived, I found that the real way he made his money was as an illegal exotic animal broker. This was pretty shocking to me, but this man swore up and down that he could teach me how to work with dogs. So I tentatively waited around in order to be this man’s student. In the meantime, I volunteered by cleaning the dogs’ kennels, feeding them, and generally looking after them.

One thing that probably should have tipped me off right away that this guy was not someone I should be around or learning from was that he had a lot of out-of-control and aggressive dogs. I remember wondering, How could he be a very good trainer if his dogs are like this? I used to take his dogs out and walk them, and he seemed amazed that I could do it. Here comes this kid who can easily walk these dogs that were aggressive with him and biting him. To me, it was easy. It was just common sense. If a dog shows teeth to me and growls at me, I don’t become afraid and I don’t get angry or blame the dog. I try to understand why the dog is growling and gain the dog’s trust. Then I walk with him. I spent time with these dogs, mostly walking them for hours. By the time the walk was over, the dogs and I understood one another. There was trust and there was respect, something they did not have for their owner. Forget about training—this was the beginning of what I would later call “dog psychology.” Of course, I didn’t know it yet.

It wasn’t long before I learned why this man’s dogs were out of control and aggressive. I saw him give the dogs some kind of injection that made them really go crazy. I don’t know what he gave them, but I knew right away that this was not dog training, and I left in a hurry. This experience was traumatic for me at the time, but today I think it was important that I got to see the worst of the worst right up front, so that I would always know the difference.

I was still determined to find someone in Mexico who could help show me the way to train dogs. I kept hearing about other dog trainers, but they were always far away—in Guadalajara, in Mexico City. And I was just a teenager. When I was fifteen, I met another man who offered to take me to Mexico City to meet two brothers who were amazing dog trainers—the champions of the champions—but it would cost me one million pesos. Today that would be about $10,000. You can imagine how overwhelming a sum that would have been for a fifteen-year-old working-class Mexican kid. But I had been saving money from my job as a kennel boy at a vet’s office and some other odd jobs for a very long time. I planned to go to Mexico City during my school vacation to learn from the “best of the best.”

The man who took my money drove me to Mexico City—which was over five hundred miles from my home in Mazatlán—and dropped me at the place where he said the brothers did their dog training. I went to the address, but there was nobody there. I’d been conned. Not only that, I was stranded and had to find a place to live while I figured out how I could get back home. Fortunately, a very kind woman took me in. She happened to have a German shepherd that was out of control. So I said, “Señora, while I’m here, can I just do something with your dog so I can pay you back for your hospitality?” And that’s what I did. The dog was obviously frustrated from pent-up energy because he lived in the city and the owners never walked him. One thing I knew from the farm was that dogs really like to walk. So I just started walking him at first. I would tire him out until he was calm and relaxed. And then I tried a little training on my own. The woman and her family lived in front of a park, so I would go there with the dog and ask him to wait, ask him to stay, ask him to come—just basic stuff. Mostly I captured the behavior that he was already doing. I had no idea that capturing a behavior an animal is already doing is one of the core tenets of operant conditioning–based animal training. I had no idea what that was, or what those words meant. It just felt very natural to me to encourage a dog to do more of what he was already doing right. So I ended up taking a class in animal training after all, except that this German shepherd ended up being my teacher.

Eventually I got a ride back to Mazatlán. I never told my parents what had happened to me—that I’d been tricked out of my money.

Despite all my setbacks in Mexico, my dream of making it to America and becoming a real dog trainer was still at the forefront of my mind. In fact, my dreams had become even bigger. I wanted to become the best dog trainer in the world.

In my first book, Cesar’s Way, I tell the story of how I crossed the border into America, got a job as a groomer in San Diego, and finally made it to Los Angeles. It didn’t work out the way I’d fantasized—which was that I’d walk into Hollywood; ask, “Where is Lassie? Where is Rin Tin Tin?”; and get apprenticed to one of the big-time movie trainers to work with him on his next movie. But I was practical—I knew I had to start somewhere. So I took a job as a kennel boy at a very big, successful, and busy dog training facility. Most of my work involved cleaning kennels and feeding, grooming, and walking dogs. We were very busy: with people dropping off dogs every day, there were thirty to fifty dogs at any one time waiting to be “trained.” It wasn’t unusual for me to work fourteen- to sixteen-hour days.

People brought their dogs to this facility to be trained in what was called Basic Obedience, which was “sit, down, stay, come, heel.” Basic Obedience was divided into three courses. The most common course was on-leash obedience; after going through this course, the dog would be ready, the facility promised, in two weeks. This was in the early ’90s, and the course cost $2,500. Then there was off-leash ground obedience, which was the same thing except now the dog was dragging the leash on the ground. Learning off-leash ground obedience was supposed to take three to four weeks, and the course ran about $3,500. For the hefty sum of $5,000, the final course was off-leash obedience: the dog stayed at the facility for two months, after which we would return the dog to the owner able to perform basic obedience completely off-leash—or at least, capable of performing off-leash with our people, in the little yard of our headquarters, where we would give the owner a demonstration to show off what we’d accomplished. The facility offered sessions for the owner afterward for an additional cost. And owners could get a pretrained dog as well—if they could afford the $15,000 price tag.

The methods used at this facility back then were what most people today would consider very harsh. There were no food rewards, and there was no positive reinforcement. It was all about choke chains and prong collars. If the first didn’t work, we moved to the second, and finally to the e-collar if all else failed. That was the protocol. Now that I’ve worked with hundreds of dogs myself, I believe that these tools have their places in some specific situations, but almost never in simple obedience training. To my mind, the whole training methodology being used at this facility was flawed because it was based on a ticking clock … and a ticking clock that just wasn’t realistic. I have come to believe that patience is the most important quality anyone who works with animals can possess. When we work with animals, we have to be prepared to first gain the animal’s trust, then wait for as long as it takes to develop communication with the animal and earn its respect.

This isn’t to say that the trainers at this facility were unkind to the animals—I’m sure most of them didn’t intend to be. A lot of accusations of “animal abuse” are thrown around today when people don’t agree with one method or another, and I’ve been at the center of some of those accusations myself. I like to remind these critics that most people who go into animal-related fields do truly care about animals and that very few people who train or work with animals make a lot of money at it. They do it for the love of the work itself and their love of animals. And the jobs are hard to come by.

When I first arrived at the dog training facility, I had no opinion one way or the other about the methods being used there. But after a little while I came to see that those methods worked only to the extent that they created short-term changes in outward behavior; they had no effect on a dog’s state of mind. Because the dogs would do the behavior just long enough to get the trainer off their back, I doubt very much that the “lessons” they learned stuck with them. In addition, many of the dogs had no motivation to learn the behavior because not only did they have no real relationship with the trainer, but the process of learning wasn’t pleasant or fun for them.

The man who ran this facility may well have been a good dog trainer, but I never saw him train a dog personally. Most of what he did for the company was sales. He was the best salesman in the world. He would bring in a dog that he had purchased in Germany and that had been through advanced training for a number of years, give a demonstration with that dog, and then say, “This is what your dog will be able to do when it leaves here.”

The key problem was that he didn’t tell owners how their dog was going to be able to learn these things, but most people back then didn’t know enough to ask that question. I don’t remember people being concerned about how their dogs were going to be trained; no one asked questions like: “What method do you use?” “Do you use positive rewards?” “Are your trainers certified?” I don’t think for a minute that these owners asked no questions because they didn’t care. I’m certain they cared a great deal about their dogs, as most dog owners do. I truly think they just didn’t have the right information to know what questions to ask.

I did a lot of observing during my time as a kennel boy at this place, and that’s when something in my mind clicked. I began asking the question, “Is obedience training really what this dog needs right now?” Many of the dogs were fearful and insecure, and the process of training made them worse. They might have left the facility being able to respond to commands, but they still had the behavior problem they’d come in with. Observing these dogs, I began to think about the idea of dog rehabilitation as opposed to dog training. I also noticed that the owners were never encouraged to be a part of the process. They would drop off their dogs at the place expecting them to be fixed, like a car or an appliance. No one considered the possibility that the owners’ own behavior was contributing to the dog’s problem behavior.

The issue was that the owners didn’t know what to look for. What the dogs needed was behavior modification; obedience training did not help them, especially the nervous ones, the fearful ones, and the extremely aggressive ones. Facing a behavior issue with their dog, owners were told, “You’ve got to train that dog.” Nobody told them, “You have to rehabilitate that dog.” Nobody told them, “You need to fulfill the needs of that dog.” The word for all of that—for everything that had to do with behavior—was training, the assumption being that a trained dog was going to be okay. I could see from the dogs that came through the facility day after day that this absolutely wasn’t the case.

Cesar’s Rules FOR CHOOSING A DOG TRAINER

I knew I wanted to become a different kind of dog “trainer,” but I didn’t have a handle on exactly what to do or how to do it yet. I left the professional facility anyway and went to work for a businessman who had been impressed with the way I handled his dog. He hired me to wash his fleet of limos and also threw me extra work training his friends’ dogs on the side. Because they were his friends, he asked me not to charge them very much, so I would bring the dogs to my job with me and work with them during my breaks. While I was working, I wanted to keep the dogs occupied and give them something challenging to do. So I taught them how to help me wash the limos.

There was a German shepherd named Howie whose owner wanted me to teach him obedience. I didn’t want to use the methods I’d left behind at the facility, and I remembered how easy it had been to train my grandfather’s dogs back home, especially when they wanted to be a part of what I was doing. So I figured out a way to teach Howie how to carry the bucket of water and bring it to me as I washed all thirteen cars.

Most dogs naturally love to chase prey, and many naturally retrieve. With Howie, I started by throwing the bucket instead of the ball, so he’d go and retrieve the bucket. He would naturally bite the inside of the bucket to get a hold of it and carry it to me sideways. I realized that wouldn’t work if I wanted the bucket to hold any water, so I put a tennis ball on the bucket handle. Howie was immediately attracted to the tennis ball, and that’s how he learned to grab the handle and carry the bucket to me upright. We worked on that for a long time. Eventually, Howie learned how to raise his head and walk very proud and tall carrying the bucket. That’s when I started putting just a little bit of water in it. But before I put the water in it, I would tell him with my energy and body language to stay where he was, to build up his eagerness to get the bucket. As soon as I saw that intensity in his posture—that he really wanted to get the bucket—I’d let him go. This was new: the bucket was not being thrown, it was in one place, and he was expected to bring it from that place to me. I eventually took the tennis ball off the bucket handle and replaced it with layers of thick tape, to make the handle easier for Howie to hold in his mouth.

Finally, I’d give a name to the activity: “Go get the bucket.” Howie learned to get the bucket from wherever it was and bring it to me wherever I was. Later on, I was able to teach this routine to other clients’ dogs.

Now that I had a bucket assistant, I needed someone to carry the hose. I chose Sike, a rottweiler whose owner wanted me to teach him obedience. The hose was much easier to teach. Using a sort of early combination of dog psychology and dog training, I began the exercise by making sure the dog was relaxed around the water coming out of the hose. Once I accomplished that—simply through gradual exposure to the hose and the water stream—I had to train Sike not to puncture the hose when he pulled it. I learned that lesson the hard way: my boss got mad at me the first time Sike bit through a hose, and he made me buy him a new one. Teaching a retriever to be gentle with a water hose is easy—they’re bred to have very soft mouths for carrying ducks intact back to hunters—but teaching a German shepherd or a rottweiler not to sink his teeth into something is a bit trickier. My solution was to put a thick roll of tape around the part of the hose I wanted the dog to target—up near the nozzle, where the surface was harder—which made the hose easier for the dogs to hold.

Howie carries the bucket by the handle.

It took me about two weeks to teach each new behavior, but when I was done, people would come by the garage to see me washing the car with a German shepherd carrying the water bucket for me and a rottweiler rinsing the wheels with a hose. After we finished each car, I’d reward the dogs with food, but I wasn’t rewarding them constantly. The tasks were complex enough to hold their attention, so it wasn’t as though they would lose interest in the middle of the process and drop the bucket or the hose. The task was challenging for them, and it was fun for them to be involved in what I was doing. In my mind, I was saying, Okay, if I finish this car, I get paid, and if I get paid, I can give you food. So I was getting as much out of the process as the dogs were. They knew that if we finished a car, they got fed. And with the dogs’ help, I washed thirteen cars that much quicker.

Sike helps Cesar with the hose.

Back then I lived in the crime-ridden “hood” of Inglewood, California. There were a lot of break-ins and a lot of gang activity. Just wanting to be able to walk safely on the streets and in the parks, people started to be interested in getting dogs for protection. I quickly learned that protection dog training was big business in our area. Aside from my work at the professional facility and the tricks and obedience work I did on my breaks washing limos, doing protection work with dogs was my first professional experience as a dog “trainer.” I had already begun to experiment with my theory of pack-power–related training, and my ability to get packs of dogs to work reliably in tandem was getting me some attention—especially when I was out in the park with a pack of perfectly behaved rotties following me off-leash. And it was that growing reputation that drew my first celebrity client, Jada Pinkett.

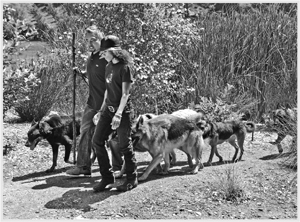

Jada has been a friend ever since our first meeting, and she and I have been through a lot together. She has since married actor Will Smith and has a beautiful family with him, but at the time I met her, she was just a young actress starting out. Living alone in Los Angeles, she felt she needed protection dogs. She did not have a lot of experience with or knowledge of powerful dogs, but she had a very open mind and was willing to learn. Jada is a tiny woman, and she would have to handle all her dogs alone, so it was imperative that I teach her to go beyond issuing commands to sit, stay, come, and even to attack—she needed to achieve the pack-leader position among her dogs. We did much more than advanced protection work with her and the pack. We took them on hikes in the mountains, to the beach, and through the tough neighborhoods of South L.A. We practiced with “bad guy” dummies in the trees and in the bushes, and Jada learned how to start and stop a protection activity. I wanted her to know beyond the shadow of a doubt that she could be in control of all the rotties at all times, in any situation. She learned more than simply which commands to use or how to choose a leash or style of “dog training.” It was really all about teaching her how to feel confident as the leader of her dogs. We achieved this through weeks and weeks of hands-on practice but also through the body language she expressed, the thoughts she focused on, and the energy she projected when she was with her dogs.

A pack walk with Jada (photo credit 1.2)

Sharing this experience with Jada was an “aha!” moment for me. It really clicked for me, working with her, how important the owner is when it comes to dog training. I knew then that this would be my new challenge and my mission—training people to understand how to communicate with their dogs.

Around this time in my development I stopped thinking of myself as a dog “trainer” and also let go of thinking about what I do with dogs as “training.” I was realizing that I would need to train owners and rehabilitate, fulfill, or balance their dogs.

I always like to say that, as immigrants, we Latinos are not taking away the jobs of Americans. We fill in where there are empty spaces. When I came to this country, there were no professionals focused on helping dog owners to understand their dogs. Nor were there any who focused on fulfilling the basic needs of the dogs themselves. It was all about getting dogs to do what people want, using our language or our own means of teaching them. So I took it upon myself to fill that empty space.

Since that time when I changed my focus, I’ve personally redefined the word training to mean answering to commands (“sit,” “stay,” “come,” “heel”), doing tricks, or doing some behavior that is not necessarily natural to the dog. Or the behavior may be natural to the dog, but we want to control it in a way that is more based on human needs than the dog’s needs. I believe that dog training is something created by humans, but that dog psychology—what I try to get my clients to practice first and foremost—is created by Mother Nature.

When any mother animal raises her babies to survive in the world, she isn’t thinking consciously about what it will take to teach them how to find food or how to spot a danger or how to follow the rules of behavior for being that particular animal. The babies learn from her what it takes to be a successful animal in that particular environment without a lot of extra effort on her part, much less bribes or punishment. Surviving, fitting in, and functioning in the world around them is their most fundamental motivation. I believe it’s important to understand a dog’s natural inclination to fit into his environment first before thinking about commands, special behaviors, or tricks.

Professional animal handler Mark Harden has been training animals for film and television for over thirty years. He’s trained everything from the wolves in Never Cry Wolf to the spiders in Arachnophobia to the parrots in the Pirates of the Caribbean movies to the cats and dogs in—what else?—Cats and Dogs. Mark trains a lot of movie dogs, but he also keeps dogs at home as family pets. And he differentiates between training and good behavior in much the same way that I do, although we use different words to describe our ideas.

“I say there’s raising and then there’s training,” Mark told me. “Those are the two things that I do, and I link it to my kids. For example, I raise them to behave in public. In a restaurant, they know how to behave. I don’t give them a treat for behaving in the restaurant. If they misbehave in the restaurant, there will be consequences, but I expect them to behave. So that’s part of how I raise them. Now, if they go and get an A-plus in math analysis, well, that might be a trick. I might be willing to reward them for that, to give them an incentive for it, because I don’t see an obvious incentive for a child to get an A-plus in math analysis. I mean, my motto with people on set is: ‘Treats are for tricks.’ I ‘pay’ for tricks, but I raise animals to behave like I would my children. I would train tricks, and I would raise them with manners.”

There are other experienced and educated professionals who don’t necessarily agree with how I define dog training and separate it from dog rehabilitation or balance. They would say, “Bottom line, Cesar is a dog trainer.” I respect the views of many of these pros and want to share with you a few of their thoughts about what dog “training” is, to help you get a taste of the range of opinions and ideas out there. As you read, think about how each definition might apply to your relationship with your dog.

Ian Dunbar is a pioneer in off-leash puppy training, prevention, and reward-based dog training; he is also a veterinarian, emeritus college professor, author, television star, and lecturer from whom we’ll hear much more later in this book. “If I were to define training,” Ian says, “I would say it comprises altering the frequency of behaviors, or putting the reliable presence or absence of specific behaviors on cue. Whenever you’re reinforcing a behavior in a dog, you’re training him. Whenever you’re punishing a dog for the wrong behavior, you’re training him. I mean, that’s the very definition of training.”

Like Ian Dunbar, Bob Bailey is a man who truly knows animal training. Along with his late wife, Marian Breland Bailey, he was among the very first to use Skinnerian operant conditioning—that is, the science of using consequences to change and shape animal behaviors. In fact, Marian Breland invented the “clicker,” which is among the most important tools in positive animal training today. In his sixty years in the trenches, Bob has worked with everything from marine mammals to ravens to snakes to chickens, training them for stage shows, commercials, movies, television, corporate demonstrations, and top-secret military work. Although Bob told my co-author that he likes to call himself a behavior technician and not a trainer, he also uses a much broader definition of the word training than I do.

“I believe that the purposeful changing of behavior is, more or less, defined as ‘training,’ ” he says. “We may call it ‘instruction,’ or ‘teaching,’ or whatever, but in the greater scheme of things, behavior is behavior, whether it be sitting, lying down, or even thinking. After a long time of observing animals in the wild and training animals to do things to put bread on my table, I know that animals respond very well to very subtle environmental stimuli. For instance, if I’m working a dog, or any animal, a slight change in the environment, including a change in my demeanor and activity, can tell the animal that now is the time to ‘chill out.’ Such ‘chill-out’ behavior by the dog may appear casual, not as obvious or dramatic as jumping on a table and grabbing some flowers out of a vase, but that behavior is under stimulus control just as much as flower-grabbing. I think most of the trainers I have known, especially the very good ones, adhere to the view that training—learning—goes on all the time, not just when we want it to.”

My friend Martin Deeley and I agree on many things, but the specific definition of dog training is not exactly one of them. Martin is an internationally known professional pet dog trainer, gundog trainer, and executive director of the International Association of Canine Professional Dog Trainers (IACP-CDT). “Training happens every moment of every day of a dog’s life, with everything you do,” says Martin. “Every interaction between you and a dog is training.” Martin would define all the different things I do when I rehabilitate dogs as every bit as much “training” as what he does when he teaches a pack of retrievers to hunt down and retrieve a fallen duck in the woods.

“In training,” he says, “I share information—information from my body, my hands, the tools I use, and the situations I’m in with the dogs. I am always looking for the best way to communicate the information. Now, some information is translated and interpreted by the dog well and quickly, and some information may not be. We change our ways of communicating information to achieve the results we seek. Information is knowledge acquired through experience or study. In training, a dog is gaining information in both ways. Do not think of information as just written or verbal. Think of it as versatile and totally understandable communication. But the aim of that communication is to change and create behaviors, which, to me, is how I define ‘training.’ ”

I agree with Ian, Bob, and Martin that we are teaching our dogs all the time—every minute—how they should react to us and act around us. To me, that concept involves leadership more than training, but this is a semantic difference. However different we four dog professionals may be in our definitions and approaches, we all have the same goal in mind, which is to help you communicate well and live happily with your dog.

I always begin by fulfilling the dog’s needs first, making sure the dog is what I refer to as balanced. Let me be clear: balanced is not a scientific term, but to me it’s incredibly descriptive of what it means for any animal—including the human animal—to be comfortable in its environment and in its own skin. Let’s look into the relationship between balance and behavior in the next chapter.