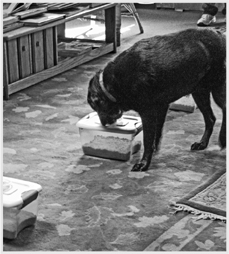

Angel sniffs for cancer. (photo credit 8.2)

How did dog training really begin? Nobody knows for sure, of course, but in my mind’s eye I see a group of ancient humans and canines, roaming the plains together thousands of years ago and working cooperatively to find food, water, and safe shelter. Some people imagine that whatever the very first dog “trainers” did back over five thousand years ago involved some kind of force, but I’m not so sure about that. I’m more aligned with the theory that some more-docile, doglike wolves ingratiated themselves with early humans, choosing us as much as we co-opted them.1 I picture that first curious “psychologist” or behaviorist of dogs realizing that a playful puppy would do anything for a piece of food or a stick—of course there were no pet stores back then! Maybe the puppy would bring some of those things back and the human would tug on them and entertain both himself and the puppy at the same time. So there were two of a dog’s biggest motivations right there on display—play drive and food drive.

And then there was prey drive. Whoever that pioneer “dog handler” may have been, I’ll bet you that his first thought wasn’t about all the different ways he could educate the animals. He wasn’t worrying about which leash to use, which theory to follow, or which treats to offer. I’m certain he was far more focused on finding out what those amazing proto-dogs were able to teach him. How did they work together to lead their pack to the closest prey? How did they track, stalk, surround, and take down the prey? How did they know to go in the direction of the nearest water? How could they be so alert to dangerous predators, long before the human sentries could hear a beast or an enemy coming near?

These early dog men and women may have realized something that modern dog owners and trainers sometimes forget—almost everything we are able to “train” a dog to do really derives from that dog’s natural instincts. Far beyond finding a better way to get a dog to sit or roll over or stop jumping on visitors at the door, it is my belief that the future of dog training will look more like the way this art and science might have begun—with our dogs, using their amazing inborn talents, teaching us.

So many of a dog’s abilities are far superior to the high-tech solutions we keep dreaming up when we try to copy what a dog does naturally. Our challenge in the future will be not to teach the dogs to do what we want, but to learn from what they are already doing—and to find better ways to help them communicate their innate knowledge to us. And the beautiful thing is that our dogs want to work with us! That’s why it’s so crucial that we honor their instincts and help our dogs to fulfill their instincts. That is the real way to a well-behaved dog.

“Okay, so I’ve got my own theory on how humans and dogs actually hooked up,” says champion herding dog trainer Jerome “Jerry” Stewart. “Now, this idea came from a trip I took down to the Borrego Springs in California, where I stopped on the side of the road overlooking a valley and watched a pack of coyotes trying to hit up a herd of cattle. I noticed where each coyote was positioning itself in relation to each other. And then the hunt was on. That made me think that way back when, centuries ago, men must have done the same thing, spotted this behavior and watched the natural hunting pack style and realized that they could use a dog to do work for them.”

Titan, a rottweiler, at Jerome Stewart’s sheepherding facility (photo credit 8.1)

Jerry Stewart has been involved in the sport of herding since 1986, when he acquired his first Shetland sheepdog. Since then, he’s become a fixture in the herding ring, teaching all-breed herding classes, offering clinics throughout the United States, and serving as an AKC and AHBA herding test and trial judge. He continued to speculate on how the first herding breeds may have come about. “So there’s some traits the early man wouldn’t want. You wouldn’t want a total alpha that’s gonna actually do the kill, because if you’re domesticating animals, you wouldn’t want the dogs eating your food. That’s my theory, anyway. None of us ever can really know. But basically we all agree that herding came about from a canine’s natural hunting pack style. And how man capitalized on that is anybody’s guess.”

There are at least twenty different breeds in the category of herding dogs, but the herding instinct still survives and bubbles up in mixed breeds and even in a few dogs that shouldn’t logically have a herding background at all.2 That is because centuries ago humans took the natural prey drive of a canine and modified it by taking away the aspect of the kill. This left them with a helpful animal with the ingrained genetic compulsion to organize herds of domesticated livestock. Many herding dogs aren’t bred to guard their flocks from predators, though dogs raised with the animals they will grow up to tend protect the flock that has become their pack. “If you haven’t bred against those traits, then those traits are probably still going to be there in the dog,” Jerry explains. “That’s why you can get a mutt that wants to do herding. Because if things have not occurred in that dog’s genetics to preclude it from doing it, it’s going to want to herd. Can’t help it.

“Some breeds of dogs are better at it than others. And it’s because they’ve been specifically bred for different traits that the herdsman wants, whoever the herdsman is, whatever kind of animals he’s working. The traits that will vary will be the size of the dog, stubbornness of the dog, traits like heeling—that means the dog’s biting the heels of the sheep or the cows—or heading—that means the dog’s going to the head and stopping the animal. These are all different traits that a different stockman would need in a dog to run his operation, however he’s got his operation configured and whatever type of animals he’s working with. So that’s why there’s so many different breeds that herd—corgis, border collies, cattle dogs, Australian shepherds. It’s because there are so many different ways they were used.”

Where would we be without herding dogs? Could we, the human race, have come as far as we have with domesticated flocks and herds of cattle, sheep, and goats if we didn’t have dogs to do that crucial work for us? With all the technology at our command, herding dogs are still a livestock manager’s most useful tool. Today herding is still more art than craft, more instinct than training, even though for many dogs some human instruction is helpful in bringing out the best herder in them. “You can’t teach a dog to herd that doesn’t have it in him, that’s for sure,” says Jerry.

So what can we give back to modern-day herding dogs that even comes close to what they have given us? Of course, the best thing in the world for a herding dog is to simply give it a job and let it herd. At my new Dog Psychology Center, I am building an arena for this very purpose. Since ordinary people don’t have herds of livestock anymore, there are also classes like those Jerry offers in which pet and owner can both participate in the activity that the dog was born for.

“So many dog problems happen because mankind, we have a very unnatural lifestyle now,” Jerry muses. “You can’t stop a herding dog from trying to do what they do, but they try it places that, as far as we’re concerned, are inappropriate. The dog is heeling pets or house-guests, for example, nipping at heels. All its life, a herding dog is trying to do what every cell in its body is telling it to do, but being told ‘No, that’s a bad dog.’ And you know, people working up regimens to get the dog trained away from doing it. They try to find all these different training techniques to get the dog to quit it. But that goes against this dog’s natural instinct. He’s only doing it because he has a genetic imperative to do it,” Jerry explains.

“When people come to herding classes, all of a sudden the dog just stops these little traits that were bothering them. They just go away. You know, things like heeling at home with a pet can be annoying. Now the owners see why the dog is doing it. ‘Oh, this wasn’t bad behavior after all,’ and all of a sudden the dog has a correct place to do it. The owners turn around and find out that this dog can actually do something that they both can participate in together. And all the tension in that dog just melts away.”

So what do you do if you have a herding dog and there’s no one like Jerry Stewart anywhere near where you live? They are not the perfect substitutes, but there’s Flyball. There’s Frisbee. There’s agility. “I tell people, especially those with herding dogs or dogs with high prey drive, that these are dogs that need a job,” says trainer Joel Silverman. “If you don’t give them a job, if you don’t train them, they’re going to do their own thing. They’re going to find a thing to do which you’re probably not going to like. So scent work. I think agility work is awesome. If that’s what your dog needs, you need to find some way to learn about that dog and what he likes to do.”

Bird dogs, tracking dogs, retrieving dogs, working terriers that go after rodents and vermin in the ground … for centuries all these dogs have joyfully offered up to us their extraordinary powers of scenting, stalking, digging, and retrieving—everything that goes along with the hunting instinct minus taking the kill for themselves. Once again, I wonder what we humans would have done without those amazing hunters by our sides.

“In our dogs, the nose and its scenting ability is the most important and unique sense,” says Martin Deeley, who understands the power of scent in his training of retrievers and other gundogs. “It is so sensitive that we are able to employ it for so many jobs in our world.

“Initially, man utilized the dog as a hunting companion. Possibly not just to run down prey but particularly to use his nose to find prey. A dog has an inherent instinct to find prey, chase it when found, catch it, kill it, and then share it with family members. Training a dog as a hunting companion harnesses these skills, with one of the main attributes being the use of the nose in the finding of prey such as birds, rabbits, and other game. The hunter may kill the game after the find, but then the dog uses another inherent skill: that of carrying the game to the family or pack—the hunter.

“Therefore, hunting, nose work, and retrieving are all strong natural skills and attributes we can harness. With some dogs, they have been enhanced through breeding. Dogs such as spaniels, retrievers, and pointers especially have been bred for these skills through selection of the best to breed the best.”

As we have seen, however, using their nose becomes a reward in itself for many kinds of dogs because they are fulfilling an intrinsic desire—the very “life rewards” that Ian Dunbar talks about. “The retrieve actually becomes the final reward for the nose work,” says Martin of his hunting dogs. “The carrying of an object they enjoy is fulfillment of successful nose work.

“A working terrier loves to work—it lives for that magic moment when the scent drifts up from the hole and its genetic code explodes within, taking everything else with it like a tidal bore,” writes Patrick Burns of his life’s passion, working Jack Russell terriers. “A working terrier would rather work than eat, drink, or rest. The work itself is a self-validating experience for the dog; it tells him what he is, and that he is right for this world. When people ask me how I reward my dogs for going to ground and baying a critter to a stop end, I reply: ‘I let them do it again.’ They love the work, and it is its own reward.”3

But much like herding, the ability to go to ground, track, and retrieve is both partially instinct and partially trained. “The terrier has the curiosity to follow scent, but the dog often has to be trained [i.e., given a few easy experiences] to understand the reward of going underground,” Patrick explains. “A small, dark, tight tunnel is not an obviously fun place for a dog. They have to discover the fun—the code has to explode. Once it does, the dog will repeat the experience for the thrill of it.”

What can we offer these dogs in return?

First, we can honor their being by making sure we communicate with them with respect for the rule of nose-eyes-ears. We can employ their noses using scent work, as in the Dunbars’ demonstration, so that their favorite sense is always engaged and fulfilled. Instead of simply trying to eradicate those instincts so they can live peacefully with us in an apartment, we can share activities with them that channel their desire to run, to track, to dig, and to retrieve. We can take responsibility for the instincts we have bred into them instead of calling them bad behavior.

In the survey discussed in Chapter 2, 22 percent of our readers said that they felt it was very important for their dogs to help warn them or even protect them from dangerous situations. Most anthropologists believe that dogs’ habit of barking to warn of potential dangers was one of the most important things that early man found useful about his canine companions. Historical records show that attack dogs have been used for personal protection and even in warfare for thousands of years. Legend has it that in 350 B.C., Alexander the Great’s dog Peritas saved his master by attacking a charging elephant. It’s clear that we humans have relied on our dogs as defenders for as long as they’ve been with us.

Many years ago, I did a lot of work in protection dog training. It was a hobby and, to a certain extent, a business. My journey has long since taken me past this phase of my life, but back when I was very involved in it, I saw that many trainers in this field taught their dogs to override their canine common sense while in attack mode. The key to all protection training is to teach the “off” switch first, before anything else. Most trainers focus instead on getting the dog into a frenzy and egging him on to the strike. A dog in crazed attack mode is blind and deaf and has broken the needle of the intensity meter. Once a dog has gotten past that level ten of intensity, he’s not listening to anything anymore—not his instincts, not his common sense, and certainly not his handler.

Back in the early ’90s, I worked with a dog named Sa, a German shepherd sent to me from the Long Beach Police Department Canine Division. This dog put three hundred stitches on one handler and one hundred on another. Each time it happened when the handler asked him to let go, the “out” command. The dog would let go and then go after the handler. I rehabilitated him, but they didn’t want him back, and so I sold him to a client who wanted a protection dog. Sa was absolutely fantastic after that. He was already trained. He just didn’t know how to out and be calm about it. I was able to condition him to understand that the most important part of his job was listening to when to go “on” and when to go “off”—the attack itself was secondary.

The way I saw protection dogs being trained back then was similar to the way dogs are trained for illegal and inhumane dogfights. There was a lot of sound—a lot of crazy barking—which the handlers seemed to think was proof that their dogs were “tough.” There was a lot of yelling and physical prodding and swearing at the dogs by the handlers. To me, this training method drowned out the best of the dogs’ natural instincts and abilities. The handlers taught their dogs using sound and sight, never engaging their noses or helping them practice their natural self-control. I was able to prove that there was a far better way.

A dog’s protection instincts derive from his prey and hunting instincts. If you watch any animal hunting in the wild, the hunt is not a frenzied thing until maybe at the very last minute. The lead-up to the hunt is very calm, very disciplined. It’s all about patience and waiting and organization. And it is very, very quiet.

I trained my dogs by starting with a rag attached to the end of a crop, which I would move around to stimulate the prey drive. I wanted the dogs to use their natural stalking ability and their natural common sense. Only when they were ready did I let them catch it. Other trainers would have their dogs leap in the air for the rag, which was more of an impulse.

I wanted to encourage my dogs to use self-control. To me, this is a much more natural challenge, because this is what dogs know. They’re programmed to wait out their prey until it gets tired or compromised. Eventually, I transferred this kind of controlled stalking behavior to a decoy human wearing protection gear. I liked to play the decoy myself. That way, I could turn the game into play—something fun that we did together. I could be 100 percent certain that my dogs understood that I always controlled when the game began and ended, just the way Ian Dunbar practices his tug games with Dune and Hugo.

Many protection trainers teach the “aus,” or “out,” command by pulling or forcing a dog off a target. That is a good way to have that leftover frenzied aggression directed at yourself, and that is what happened with Sa. In teaching the “aus” command, I would allow a dog to bite my arm (wearing protection gear, of course), and then I would stop moving, sit very still, and wait. When the dog naturally let go, I would say the command. I put myself in a position where I just had to wait and let the dog have fun. When he was ready to let go, then I said, “Aus.” That way, I was going with the flow. I didn’t use food rewards, but I did use a lot of praise and pride. I was using the dog’s natural knowledge of when to let go of its prey by just putting it on command.

These are all techniques I borrowed from traditional Schutzhund training exercises. Schutzhund is the German word for “protection dog,” and it has evolved over hundreds of years into an exacting sport that tests and challenges the temperament and split-second obedience, or “soundness,” of a dog. Many protection trainers use German words because they derive from Schutzhund. However, not all protection training is Schutzhund training. Schutzhund is a disciplined sport that does not result in a mean or defensive dog. In fact, Schutzhund-trained dogs are “just the opposite,” says Diane Foster, who, along with her husband, Doug, breeds German shepherds and trains dogs in the Schutzhund tradition. “You can trust a dog that is trained for this. A Schutzhund dog will not attack anyone unless the person comes at him.”

Even after successfully completing training exercises, some of the handlers I knew could not safely trust their protection dogs in public settings. These animals had been conditioned in a very unnatural way, and so they were overly keyed up to sudden sounds and movements—similar to the way Gavin the ATF dog became overly sensitive to sounds. Like Schutzhund-trained dogs, my dogs, I insisted, were safe under any conditions, with any human. After all, I raised them around my kids.

Most people are shocked to find out that I trained my late pit bull Daddy to be a top-notch protection dog. Mellow, laid-back Daddy? The best pit bull on this earth? He learned these skills alongside a pack of rottweilers that I raised him with from the time he was four months old. Yet as every Dog Whisperer fan knows, I could take Daddy with me anywhere in the world and completely trust him with any person or animal, in any situation. If we were doing a Dog Whisperer episode and another dog became aggressive toward Daddy, he would not respond in a defensive way just because he’d had protection training. His training kicked in only under two very specific circumstances: one, if I triggered it with a command; and two, if a threatening adult male human made a truly aggressive move toward one of his pack. Because I had not messed with Daddy’s instincts, he knew from the deepest animal-dog part of himself the difference between a bad guy with a real serious motive to harm and someone just joking around.

I trusted Daddy’s instincts 100 percent. I never spent a moment worrying about him. Daddy lived sixteen years and never once hurt or bit anyone. He preferred licking people’s faces, sprawling on the ground near people’s feet, and, of course, getting his stomach rubbed. But he definitely came to the rescue on more than one occasion. Former Dog Psychology Center employee Tina Madden remembers one such incident that happened back in 2007, when Daddy was thirteen years old.

“Daddy was diagnosed with cancer during the first few months that I worked for Cesar, and I drove Daddy to one of his chemotherapy appointments. I remember driving back down into the rough neighborhood of South Central one day and not really knowing the area all that well. I pulled into a drive-thru to get myself some lunch, and Daddy was sleeping on the front seat of my truck, and I had the windows down for air for him. Suddenly I caught the eye of these two guys who were definitely big trouble. And they looked right at me and made a beeline for the car really fast, and I thought, ‘Oh no, why did I make eye contact? What was I thinking?’ I was stuck at the drive-thru, car in front of me, car behind me. I was terrified. I knew something really awful was about to happen to me.

“I completely forgot that Daddy was sleeping right there next to me. And the guys kept coming, and one of them started to lean into the car. The next thing I knew, Daddy was awake and had jumped up and just let loose with this really scary growl. It was like I had a grown lion in the car with me. These two guys turned white and ran like nobody’s business, screaming. They were gone, in six seconds or less. I gasped with relief and looked at Daddy. This was right after his chemo and everything. And then after they were gone and I rolled up the window, he just looked at me, lay down, and went back to sleep. I told Cesar about it, and he said to me, ‘Make sure you thank Daddy for that.’ I said, ‘I’ve thanked him every single day since.’ He really saved me from a very bad situation. I bet you those boys had soiled underwear that day. Thank God for Daddy.”

Daddy’s protégé, Junior, is also a pit bull, and I raised him from a puppy in much the same way that I raised Daddy. The big difference between them is that I don’t want Junior to have any access to that protection dog side of himself. I live in the suburbs now and don’t need a dog for protection anymore. Junior has not been trained in how to bite or how to hold on. I don’t even play tug-of-war or dominance games with him. I have not tapped in to his prey instinct side or the side that wants to defend the pack. Instead, Junior is the peacemaker. He knows that his teeth are not to be used on another animal, period, unless it is an inhibited bite during play. To Junior an outstretched hand means to drop whatever he is holding and not to touch. Even a child can put her hand in Junior’s food bowl while he is eating and Junior will politely back away. I want Junior to be the opposite of a pit bull: a happy-go-lucky guy who uses his instincts and energy and intensity for exercise—for lots of play, of course, but also for helping other animals become balanced, which, in a way, makes him the opposite of a pit bull.

The protection instinct in dogs is not one to mess around with, even if your dog is not the obvious breed for this purpose, like a German shepherd, rottweiler, Belgian malinois, or Doberman. The only criterion for a great protection dog is courage, and courage doesn’t have a breed. Pretty much every terrier will kick your ass, since they were bred to hunt for animals that can turn on them and fight back, like rodents and vermin and even foxes. A Jack Russell terrier might have to target a mugger’s feet, but he’d be right there to defend you. We’ve seen on Dog Whisperer how little Chihuahuas and Yorkies can become weapons when they’re not socialized properly and instead are carried around by their owners all the time; many will attack people who reach out to pet them. Even a lower-energy bulldog like Mr. President could have become a protection dog if I hadn’t raised him to respect and be submissive to all humans, though he’d get hot and tired pretty fast.

I advise people to think long and hard about whether they want their dogs to be their defenders. It is a lot of responsibility to put on any dog, especially if the training isn’t done exactly right. If this is something you are serious about, you should look into Schutzhund or other disciplined training that promises not to turn your dog into a weapon without an “off” switch.

This is where dog psychology has an advantage over traditional dog training. If you are your dog’s leader in all situations, you can always switch him off. Like Daddy, your dog can always have access to his own best instincts and quickly return to balance once the time to be on alert is over. The trust and respect between you and your dog—something that goes far beyond simple command training—is what gives you the ability to snap him out of an alert, excited dominant state and back to peaceful, calm submission. If you are not 100 percent comfortable in your position as your dog’s pack leader, then get a good alarm system or a can of Mace and let your dog just enjoy being a dog.

For many years, people have been collecting anecdotal evidence about dogs’ ability to detect physical instabilities in people and predict epileptic seizures, heart attacks, strokes, and diabetic comas—all manner of disorders with onsets that are still largely a mystery to modern medicine. I believe the real future of dog training will be in teaching ourselves to understand these important communications dogs are sending us about our health.

In most of these areas, the science isn’t in yet as to how dogs sense what they do about our physical condition, and humans still have very few ideas about how to train or make use of this innate ability in dogs. But at the Pine Street Clinic in San Anselmo, California, the proof is in the puppy—and, more important, in the statistics.

The streets of picture-perfect San Anselmo, California, are lined with funky boutiques, antique stores, and colorful Victorian homes from the Gold Rush era. At the end of one of these streets is a small, pink, adobe-style storefront with an awning that reads PINE STREET CLINIC. Inside, an old-fashioned raised pharmacy counter spans a cozy room carpeted with Oriental rugs and framed by book-lined walls. It’s a casual, healing environment—there’s even an aviary filled with quietly chirping finches.

When I first entered this peaceful sanctuary with miniature schnauzer Angel trotting brightly by my side, I immediately felt at home. I am a great supporter of many alternative medicine practices, and for thirty years the Pine Street Clinic has specialized in integrating Western therapies, drugs, and supplements with time-tested Eastern herbs, acupuncture, and philosophy.

But Pine Street is more than just a clinic. It’s the home of a foundation that for the past nine years has been conducting a series of amazing clinical trials that prove dogs can detect lung, breast, pancreatic, and ovarian cancer from human breath samples. I had come here to see the world-famous cancer-sniffing dogs in action and to see if little Angel could learn how to perform this fantastic feat himself.

The Pine Street Clinic (photo credit 8.4)

For hundreds of years, a certain story has emerged among people in every culture and from every walk of life: people report that their dog started acting strangely shortly before they were diagnosed with cancer or another illness. Often the dog seemed to hone right in on the part of the body where the disease was taking hold. We had a case just like that in season four of Dog Whisperer. The Make a Wish Foundation contacted us for help in fulfilling the dream of Michelle Crowley, a cancer survivor whose rottweiler, Major, had actually discovered her disease. Scientists began to take such reports seriously only a decade or so ago, when they theorized that dogs can smell even the tiniest molecular changes in our bodies.4

“It started with a group out of the University of Florida at Tallahassee in the early ’90s,” says Michael Broffman, director of the Pine Street Foundation. “Some researchers there, plus a local dermatologist, got together with a terrific dog trainer, and they actually demonstrated that the dogs, successfully, with a high degree of accuracy, could really differentiate between a melanoma lesion and a non-melanoma lesion on a variety of people. They published the study, and based on that we decided to launch our own program. At the same time, the British were working on a program with dogs, looking at prostate cancer, so we decided in the mid-’90s to start looking at lung cancer and breast cancer.”

Cancer cells, even in the disease’s earliest stages, excrete a specific waste product that researchers predicted would show up in human breath. The Pine Street folks decided to see whether dogs could reliably detect the presence of cancer at stages I, II, III, or IV in breath samples. In 2003, the clinic started its lung and breast cancer trials with two dogs—two beige-colored standard poodles adopted from a top breeder, chosen specifically for their scent-oriented behavior. “The two dogs we selected seemed to be the ones that were exploring the world with their noses immediately,” says Broffman. Shortly after that, the Pine Street Foundation hired its first head trainer, Kirk Turner.

Turner chose a poodle puppy named Shing Ling, two Portuguese water dog puppies, and an adult Labrador retriever to join the study. “With the other dogs in the program who were already adult dogs, we were really looking for dogs that were work-motivated, because the research involved three or four hours a day, several days a week, for several months,” Broffman explains. “So we needed a dog that was interested in working, happy to work, had some motivation, wouldn’t get bored, and would stay with it for that duration.” Surprisingly, the obvious candidates for scent work, like beagles and bloodhounds, were rejected because they didn’t have the stamina, focus, and work ethic of the poodles, Portuguese water dogs, and Labradors.

As we’ve seen throughout this book, no training can succeed without an understanding of what motivates each specific dog. “We found three different motivations,” says Broffman. “Play and food are both obvious for the Labs and the Portuguese water dogs. For the poodles, it was sort of fascinating because, on the one hand, they were very easy to train, with very high work motivation, but their reward was more our acknowledgment that they got it correct, as opposed to play or food.”

The poodles enjoyed doing their jobs, and everybody on the research team was impressed by their work ethic. But Michael Broffman and his team soon learned that poodles are, to put it in human terms, “perfectionists.” “We had mixed up our samples between which ones were the cancer samples and which ones were the control. And so, as the dog was going through the training on a given day, the dog kept on identifying a sample as being cancer, and we kept on saying, ‘No.’ This went on for a couple of hours until we realized that the dog was right, and we had actually made a mistake. And the poodle basically just quit working for a few weeks based on that. You know, a Lab would’ve been upset an hour or two and then just got back at it, but the poodles tend to carry these things a little bit farther.”

In other words, don’t try to mess with a poodle’s instincts!

As the trials progressed and the dogs became more and more adept at picking out the cancer samples from the controls, the poodles’ simple need for acknowledgment and recognition of a job well done actually caused some problems outside the laboratory setting. “We’d be on the street on a day off, and suddenly the dogs would identify a complete stranger, just someone minding their own business.” Michael Broffman still shakes his head in amazement as he recounts this story. “And it would create a lot of awkward moments to have to walk up to a complete stranger and say, ‘Excuse me, but our dogs were telling us that you have lung cancer. And they could be wrong, but they’re over ninety percent accurate in this lab study we’re doing. We feel obligated to tell you maybe you should see your doctor.’ And it took us a number of months to figure out how to get the poodles to stop working outside of the very specific research setting.”

At least two of the strangers whom the Pine Street poodles had pinpointed on the street called the organization later to report that, yes, the poodles had been correct—they had been diagnosed with cancer. Both of them were very thankful to have had the canine early warning.

Not only did the dogs perform exceptionally well in these studies, but they did so consistently over a four-month period of 12,295 separate scent trials—each one documented on videotape. “What is important about this study,” the Pine Street Foundation’s Web site reports, “is that (1) ordinary dogs, with no prior scent discrimination training, could be rapidly trained to identify lung and breast cancer patients by smelling samples of their breath, when compared to blank unused sample tubes; (2) dogs could accurately and reliably distinguish breath samples of lung and breast cancer patients from those of healthy controls; and (3) the dog’s diagnostic performance was not affected by disease stage of cancer patients, age, smoking, or most recently eaten meal among either cancer patients or controls.”5

The first peer-reviewed paper published by the Pine Street Foundation came out in the journal Integrative Cancer Therapies in 2006. In a study of eighty-six people—fifty-five with lung cancer and thirty-one with breast cancer—five professionally trained scent dogs accurately distinguished between breath samples from diseased patients and those from eighty-three healthy controls. The dogs’ ability to correctly identify or rule out lung and breast cancer, at both early and late stages, was around 90 percent.6

The success of this study earned the foundation another grant to begin its current study, which is testing dogs’ ability to detect ovarian cancer from breath samples. Ovarian cancer has a high fatality rate because its sufferers often don’t show any symptoms until very late in the progression of the disease. Canine scent work promises a method for early detection with the potential of saving millions of women’s lives.

Kirk Turner was in charge of selecting the dogs for this next phase of the project. Some of the dogs auditioned for the role were retired guide dogs. “We probably went through forty dogs to come up with the five that ended up continuing in December,” says Kirk. “They can’t live in a house where anybody smokes because that’ll ruin the scenting ability of any dog in six weeks. And they had to be happy, bright dogs without any kind of emotional problems, and also not too spoiled by the owners.”

The day Angel and I went to the Pine Street Clinic, the two Michaels—Broffman and McCulloch—and trainer Kirk Turner arranged a full demonstration of what their cancer dogs could do. Kirk has been training dogs for this special task for over seven years, and he can now do it in a very short period of time. “Two and a half weeks,” Kirk told me. “That’s what it takes for me to train a cancer dog. Five runs, and then they get taken out and walked. And then it’s the next dog’s turn. They usually do this between two and three times a day, which means the dogs do no more than fifteen runs a day. The runs usually take less than a minute.”

“That’s an amazing learning curve,” I said, impressed.

“Our big research grants over the years have come from the Department of Defense,” Michael Broffman added. “And this caused a big flap when we published our research a couple of years ago. Because we were able to train our dogs to do scent detection in about a third of the time that it took the Department of Defense’s best dog trainer at their Alabama facility to do for the military. And it caused a lot of problems within their dog training world as to how and why we were able to train our dogs that much more efficiently and more accurately than their best guy. And I think it was largely because we were taking the position of actually nurturing and highlighting the dog’s natural instincts and not trying to overlay some heavy training methodology.”

“We do want them to go home and be dogs too,” Kirk said. “That’s why we use people’s pet dogs. We don’t own the dogs.”

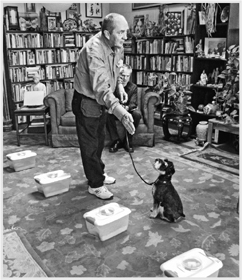

Today Kirk had brought along a very enthusiastic, muscular black Labrador named Freeman to demonstrate the process. Freeman is a retired guide dog with a great work ethic but a very high-energy personality. To keep Freeman’s energy focused on the task at hand, Kirk warned me and my crew not to give the dog affection before the demonstration began. “The last time, he fell in love with a cameraman and his brain went out the window.”

Kirk trains the cancer-detecting dogs using the clicker method and a hands-off approach to training. “I really didn’t focus on the obedience part,” he said. “When it came to indicating cancer, I used a clicker, and it worked really well. And you know, I think that’s why it was so quick, because I was basically letting the dog choose for himself.”

When it came time for the demonstration, the Pine Street Foundation team set up five basic storage containers, the kind that you can buy at any store, with special holes cut into the center of the lids. Into each hole went the small aerated dishes that held the breath specimen. The ovarian cancer breath specimens were collected from volunteers, who breathed into a special tube that captured, condensed, and sealed the samples for future use. The researchers collected specimens from cancer-free women to use as controls.

For each trial, the researchers put cancer-free control specimens into four of the five containers, with only one container holding the sample of cancerous breath. Kirk always stays out of the room while his team sets up the samples, because there’s always the danger that, through his body language and attitude, he’ll subconsciously indicate to Freeman which specimen dish holds the cancer.

Now it was time to let Freeman out of his crate. When he works with this high-energy Lab, Kirk likes to keep the leash on, for the first run at least. “I want to have the leash on just to show him what I want him to do, which is sniff the containers. He hasn’t worked in several months, so it may take him a run or two to get up to speed again.” Kirk led Freeman around the containers. Freeman sniffed each one and sat down next to one. Sitting down next to a sample is the signal the dog is supposed to give when it identifies cancer. Freeman’s choice was not the correct one. Kirk released him, and Freeman continued to sniff. Then he sat down next to two more containers. Kirk did not acknowledge or reward him in any way. Then they went back to the starting position. It was time for the real thing.

Now Kirk let Freeman off the leash and told him, “Go to work!” This time Freeman went down the line, smelling each container until he sat down next to one. This time he sat down next to the correct container. Kirk gave a quick click on his clicker, recalling Freeman. Kirk rewarded Freeman with a treat and lots of praise.

Freeman sniffs for cancer. (photo credit 8.3)

While I look on, Freeman identifies a cancer specimen. (photo credit 8.5)

Kirk and Freeman went back outside. “Another thing I like to do is to get him out here to smell something else in between,” Kirk explained. This is like what happens when you shop for perfume or cologne, and the salesperson makes you smell coffee in between brands. The smells are so different that if you smell them one after the other, you can very easily tell them apart.

The team did several more runs while I watched in amazement. After each run, they’d change the lids on the containers, because Freeman’s wet nose would contaminate the smell. Freeman took a minute to warm up, but before long he was detecting the cancer on his first try. Each correct detection got a click and a treat from Kirk. By the time they were done with the demonstration, Freeman was seven for eight.

As Freeman performed his work, researcher Michael McCulloch looked on, beaming, writing down notes on a clipboard. These dogs are very good at what they do. “We actually had a case where one of our dogs detected breast cancer recurrence eighteen months before it was found in routine follow-up care,” he told me. “That was in our 2006 published study. This was a person who enrolled in the study that we thought was in the control group. But twenty-four times out of twenty-five that the dogs sniffed her breath sample, they indicated, that is a cancer sample. And this is the same reaction from more than one dog. So we went to interview her and found that she had actually been in remission for breast cancer for which she had been treated some years before. About a year after the study was concluded, we learned that they had just then detected by a scan in the margin of where she had her prior surgery a tiny, tiny tumor that would have been undetectable at the time that we were doing the study. So that’s how good these dogs seem to be—they may be able to provide very early detection. We’re now doing a follow-up study on ovarian cancer, which is still open for recruitment, and women can join at www.pinestreetfoundation.org.”

The next phase of the Pine Street Foundation’s research involves comparing scent-detected cancer samples with chemically analyzed samples from the same subject. Will modern chemical analysis in a laboratory be able to come up with the same success rate as the dogs? Can science ever figure out exactly what tiny molecular changes the dogs are smelling? For right now, the only known fact is this: a dog’s brain and nose are among the most sophisticated odor-detecting devices on the planet, and modern science hasn’t even begun to match them yet.

I had brought miniature schnauzer Angel with me on this visit because, having raised him from a puppy for the book How to Raise the Perfect Dog, I know what an incredible nose he has. Once, when he was still a young puppy, Angel found a cigarette butt that was buried under three inches of dirt. I wanted to see if Angel had what it takes to become a lifesaving, cancer-sniffing dog.

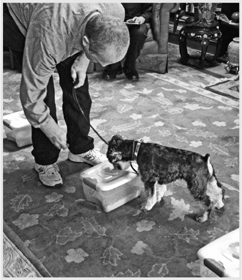

Kirk showed me the very basics of the training. Since Angel had never had any formal “training” except agility classes, Kirk had to introduce the clicker to him. Keeping him on his leash, Kirk held a treat in his hand, and when Angel came up and took the treat, Kirk gave him a click. “I just want to establish that the click noise means that the next thing that happens is he gets a treat,” Kirk said. Next, Kirk established that when Angel looked him in the eyes, he would get a click and treat. Angel, always an incredibly quick learner, picked right up on both these concepts without breaking a sweat.

Kirk then brought Angel to the containers and let him smell the lids. Each time Angel put his nose to the lid and sniffed, he was rewarded with a click and a treat. “On the cancer one, I would have him sit, or down, or however he wants to do it,” Kirk explained. “But the whole idea is to first smell.”

Kirk pointed to the lid of the container that had the cancer sample. He then stood, and following his physical cue, Angel sat down. Again, he got a click and a treat. This was reinforced again and again until Angel would smell the lid and sit, without Kirk’s physical command.

“How did he do?” I asked Kirk, eagerly.

“Angel is an excellent candidate for this kind of work because he’s got a great work ethic and already knows the basics of how to communicate with a human. Yeah, Angel did great,” he reassured me.

In fact, Angel was such a natural and such an apt pupil that statistician Michael McCulloch asked me if he was up for adoption! “Sorry, no, he belongs to SueAnn Fincke, the Dog Whisperer director,” I answered.

Kirk, too, was disappointed. “It’s always been my dream to teach smaller dogs,” he said. “The very first melanoma cancer–detecting dog was a schnauzer. Miniature schnauzers would be a good choice for this kind of work because they’re very, very smart. They love to learn and work. And if you teach everything as almost a game and make it really fun, especially the scenting stuff, I think this would be a very good breed. But you know, one of the advantages of teaching a bunch of small dogs is that they’re more portable. You can get a bunch of them in one vehicle.”

A fast learner! (photo credit 8.6)

Kirk has another dream that he hopes to realize now that the Pine Street Foundation’s research has quantified a formerly mysterious ability. “Our study provides compelling evidence that cancers hidden deep within the body can be detected simply by examining the odors of a person’s breath. So that’s one of the reasons why I wanted to start our own company. We could take on projects from other organizations involved in scent detection, but my most ambitious vision is to train doctors and dogs to work with each other and communicate with each other. Just imagine the possibility—dogs and doctors going together through villages in Third World countries, where you can’t drag along expensive equipment, and doing early diagnostic work and other kinds of therapy. This is really a possibility now.”

In my opinion, the very best dog training lets a dog be a dog first. As dog handlers, owners, and pack leaders, we want to be in control of our dogs’ instincts—for example, we definitely don’t want a dog’s prey instinct to kick in full force when the neighbor’s beloved cat crosses our yard—but we also must make sure that we listen to and honor those instincts, especially when they have something to teach us. When we simply try to force a training method on a dog or try to make him do something that doesn’t make sense to him on an instinctual level, we do him and ourselves a huge disservice. Though we may be able to teach him how to do something, at the same time we completely blind him and isolate him from his own common sense. A dog that isn’t connected to his natural common sense can’t relate to other dogs and can’t really be balanced or fulfilled in his life. And as we’ve seen in case after case on the Dog Whisperer show, when a dog isn’t fulfilled, he can’t possibly be the best companion for the humans who live with him either.

When we properly instruct a dog in how to best use an instinct he was born with, he gets something very powerful from us in return—something that he cannot get in the natural world. Not only does he experience the joy of performing the activity, but he gets a kind of euphoria when his human praises and rewards him and shares in his triumph with him. This allows him to experience a feeling that he will never be able to share with another dog, which is a celebration of his personal achievement.

A dog’s instincts are what first motivated humans to join forces with another species thousands of years ago. And yet instincts are often the very thing we try to suppress in our modern dogs. Some dog owners have come to believe that “dog training” is a good way to get a dog to put his instincts behind him forever.

Being in control of a dog’s instincts is not the same thing as trying to eliminate them. Encouraging instinct is simply rewarding natural behavior or not extinguishing it through punishment. When we honor a dog’s instincts and make them the cornerstone of our relationship, it can open up a whole new world for us.

Through centuries of breeding, humans have been learning to understand more about how dogs learn and training them to enhance their skills. By understanding and recognizing the sensitivity and ability of a dog’s nose, humans have been able to teach a dog to scent so many different things, from drugs to fruit and explosives to bedbugs and, ultimately, cancer. A scent hound can track down one person out of thousands if we familiarize him with even the most minute odor that the person left behind. A search-and-rescue dog can detect where humans are buried under snow and rubble. He can scent the chemical changes in a human body that indicates a medical condition such as a seizure.

If we honor our dogs’ natural abilities and train ourselves first, then we can develop with our dogs the greatest animal-human partnership ever imagined.