During the five years when Lenin was in charge, the foreign policy of Soviet Russia was an adjunct of the policies of the Russian Communist Party. As such, it was intended to serve, first and foremost, the interests of the global socialist revolution. It cannot be stressed strongly enough and often enough that the Bolsheviks seized power not to change Russia but to use Russia as a springboard for a world revolution, a fact that their foreign failures and subsequent concentration on building “socialism in one country” tend to obscure. “We assert,” Lenin said in May 1918, “that the interests of socialism, the interests of world socialism are superior to national interests, to the interests of the state.”1 But inasmuch as Soviet Russia was the first, and, for a long time, the only Communist country in the world, the Bolsheviks came to regard the interests of Russia as identical with those of Communism. And once the expectations of an imminent global revolution receded, they assigned the interests of Soviet Russia the highest priority: for, after all, Communism in Russia was a reality, whereas everywhere else it was but a hope.

As the government of a country that had its own national interests and, at the same time, served as the headquarters of a supranational revolution, a cause that knew no boundaries, the Bolshevik regime developed a two-tiered foreign policy. The Commissariat of Foreign Relations, acting in the name of Soviet Russia, maintained formally correct relations with those foreign states that were prepared to have dealings with it. The task of promoting the global revolution was consigned to a new body, the Third or Communist International (Comintern), founded in March 1919. Formally, the Comintern was independent of both the Soviet government and the Russian Communist Party; in reality it was a department of the latter’s Central Committee. The official separation of the two entities deceived few who cared to know, but it enabled Moscow to conduct a policy of concurrent détente and subversion.

The Bolsheviks insisted with a monotony suggestive of sincerity that if their revolution was to survive it had to spread abroad. This belief they reluctantly abandoned only around 1921, when repeated failures to export revolution persuaded them there would be no repetition of October 1917, at any rate for a long time to come. Until then they encouraged, incited, and organized revolutionary movements wherever the opportunity presented itself. To this end, they formed a network of foreign Communist parties by replicating the tactics Lenin had employed in the early 1900s to create the Bolshevik party, that is, by splitting Social-Democratic organizations and detaching from them the most radical elements. Simultaneously, Moscow negotiated with foreign governments for diplomatic recognition and economic aid.

The Bolsheviks had greater success in winning recognition than in exporting revolution. By the spring of 1921, the major European powers had established commercial ties with Soviet Russia, which were soon followed by diplomatic relations. Every attempt to spread revolution abroad, however, miscarried because of inadequate popular support and repression. On balance, therefore, Lenin’s foreign policy failed. His inability to merge Russia with the economically and culturally more advanced countries of the West virtually ensured that she would eventually revert to her own autocratic and bureaucratic traditions. It made all but inevitable the triumph of Stalinism.

Lenin’s one foreign policy success was to exploit for his own ends diverse groups abroad, ranging from Communists and fellow-travelers to conservatives and isolationists, which for one reason or another wanted to normalize relations with the Soviet regime and opposed intervention on behalf of the Whites. The “hands off Russia” slogan robbed the White armies of more effective aid from the West.

Lenin first tried to export revolution in the winter of 1918–19 to Finland and the Baltic republics: in Finland by means of a coup, in the Baltic countries, by means of an invasion. Strictly speaking, neither attempt was intervention, however, inasmuch as the four countries involved had been part of the Russian Empire.

In October–November 1918, when the Central Powers sued for peace, the Bolsheviks felt the hour they had been waiting for had arrived. The collapse of Germany and Austria had caused a political vacuum to emerge in the center of Europe: accompanied as it was by economic breakdown and social unrest, it seemed to provide an ideal breeding ground for revolution. The radical upheavals that shook Germany at the end of October and early November 1918—the mutiny of the fleet, the revolts in Berlin and other cities—while not directed from Soviet Russia were clearly inspired by her example. And yet, despite the role played by the proto-Communist Spartacus League and the importation of such Russian institutions as the soviets, the November revolution in Germany was not a Bolshevik one, since it was primarily directed against the monarchy and the war: “notwithstanding all the socialist appearance … it was a bourgeois revolution,” that is, an analogue of the Russian February rather than October Revolution. The “Congress of Soviets” that convened in Berlin on November 10, 1918, and proclaimed the establishment of a “Soviet Government,” was not even socialist in composition.2

In October 1918, just before collapsing, Germany had expelled from Berlin the Soviet embassy from which German radicals had carried out their subversive activities.3 In its place, in January 1919 Lenin dispatched to Germany Karl Radek, an Austrian subject who had numerous contacts there and was well acquainted with her political situation. Radek was accompanied by Adolf Ioffe, Nicholas Bukharin, and Christian Rakovskii.4 He lost no time taking charge of the newly formed German Communist Party directed by Paul Levi. But his main hope was the Spartacus League, formed out of the radical wing of the Independent Social-Democratic Party (USPD), led by Karl Liebknecht, Rosa Luxemburg, and her lover, Leo Jogiches.* Ignoring the hesitations of the Spartacists, Radek appealed to German soldiers and workers to boycott the elections to the National Assembly and overthrow the interim socialist government.5

The strategy, based on the experience of October 1917, misfired because the German authorities, avoiding the mistakes of the Russian Provisional Government, moved vigorously to crush the attempt by a small minority to defy the nation’s will. On January 5, 1919, the Spartacists, joined by the Independent SDs, staged an uprising in Berlin. As the Bolsheviks had done in Russia, they timed the revolt to precede the elections to the National Assembly, scheduled for January 19, which they knew they could not win. Tens of thousands of excited workers and intellectuals filled the streets of the capital carrying red banners and awaiting the signal to attack. The revolt had a reasonable chance of success, for the Socialist government had no regular forces at its disposal. Emulating the Bolsheviks, the Spartacists declared the government deposed and power transferred to a Military-Revolutionary Committee. Then they froze in inactivity. Unlike the Russian Provisional Government under similar circumstances, the German socialists turned for help to the military. They appealed to veterans to form volunteer detachments, the so-called Freikorps, staffed mainly by officers, many of a monarchist persuasion. On January 10, the Freikorps went into action and quickly suppressed the rebellion. Liebknecht and Luxemburg were arrested and murdered. Two weeks later Radek was taken into custody.6 In a protest note to Moscow, the German government claimed it had “incontrovertible evidence” that Russian officials and Russian money were behind the rebellion.7

24. Radek on the eve of World War I.

In elections to the National Assembly, which the Spartacists boycotted, the Independent Social-Democrats received only 7.6 percent of the vote: their one-time colleagues and now principal rivals, the Social Democrats (SPD), who had won 38.0 percent, formed a coalition government.8 In February, in striking contrast to what had happened in Russia, the Executive Committee of the German Worker and Soldier Soviets, rather than claiming power, resigned in favor of the National Assembly.9

The German Communists ignored this setback and tried to seize power in several cities, including Berlin and Munich. Their rebellions were suppressed as well: in Berlin, over one thousand people lost their lives. The high point of these putsches was the proclamation in Munich on April 7 of a Bavarian Socialist Republic. The leaders of the Munich revolt, Dr. Eugen Levine and Max Lieven, were veterans of the Russian revolutionary movement; Levine was a Russian Socialist-Revolutionary, and Lieven, the son of the German consul in Moscow, considered himself a Russian.10 Their program, closely modeled on Russian precedents, called for arming the workers, expropriating banks, confiscating “kulak” lands, and creating a security police with authority to take hostages.11 Lenin, who took a keen interest in these events, sent a personal emissary to Germany to urge the adoption of a broad program of socialist expropriations extending to factories, capitalist farms, and residential buildings, such as he had successfully carried out in Russia.12 The strategy showed a remarkable ignorance of the German workers’ and farmers’ inbred respect for the state and private property.

During this brief revolutionary interlude, which ended in the summer of 1919, the Soviet government acted on the premise that in Germany, as in Russia in 1917, there existed “dual power” (dvoevlastie), and addressed its official communications to both the German government and the Soviets of Worker and Soldier Deputies.13

Only in Hungary did the Communists achieve some success in exporting revolution, and this more for nationalist than socialist reasons.

Following the Armistice, Hungary was proclaimed a republic under a government headed by Count Michael Karolyi, a liberal aristocrat who cooperated with the Social Democrats. In January 1919 Karolyi became President. He resigned two months later in protest against the decision of the Allies to allocate Transylvania to the Romanians, a region with a predominantly Magyar population that the Allies had promised Romania in 1916 as a reward for entering the war on their side. The loss of this region aroused fierce nationalist passions in Hungary.

Hungary had few Communists: a high proportion were repatriated prisoners of war from Russia and urban intellectuals.14 Their leader, Bela Kun, a onetime Social Democratic journalist, had commanded in Soviet Russia the Hungarian Internationalist detachment. Moscow sent him to Hungary ostensibly to arrange for the return of Russian POWs but in reality to act as its agent. At the time the Allies assigned Transylvania to Romania, he was serving time in a Hungarian jail for Communist agitation. There he was visited by a Social Democratic group who proposed to him forming a coalition government with the Communists: in this manner the SDs hoped to gain Soviet Russia’s help against Romania. Kun agreed on several conditions: the Social Democrats were to merge with the Communists into a single “Hungarian Socialist Party,” the country would be governed by a dictatorship, and there would be “the closest and most far-reaching alliance with the Russian Soviet government so as to preserve the rule of the proletariat and combat Entente imperialism.”15 The conditions were accepted and on March 21, 1919, a coalition government came into being. Lenin, who had always insisted on the Communists maintaining a separate organizational identity, expressed strong disapproval of the merger of Hungarian Communists with the Social Democrats, carried out on Kun’s insistence, and ordered him to break up the coalition, but Kun ignored his wishes.16 The Eighth Congress of the Russian Communist Party, held that month, hailed the Hungarian Soviet state as marking the dawn of the global triumph of Communism.* The new government hardly reflected Hungarian conditions, given that 18 of its 26 Commissars were Jews;17 but then this was hardly surprising, given that in Hungary, as in the rest of Eastern Europe, Jews made up a large part of the urban intelligentsia and Communism was primarily a movement of urban intellectuals.

Regarded by Hungarians “as a government of national defense in alliance with Soviet Russia,”18 the coalition initially enjoyed the support of nearly all strata of the population, the middle class included. Had it remained such, the Communists might have established themselves in Hungary for good. This did not happen because Kun, who was formally Commissar of Foreign Affairs but in reality head of state, was in a hurry to communize Hungary and from there penetrate Czechoslovakia and Austria. He rejected Allied compromise solutions of the Hungarian-Romanian territorial dispute, since his power depended on continued enmity between the two countries. He ordered the abolition of private property in the means of production, including land, but refused to distribute the nationalized estates to the farmers, forcing them into producers’ cooperatives, which alienated the peasantry. The workers, too, soon turned against the Communists. As his authority eroded, Kun increasingly resorted to terror, the brutalities of which, together with inflation, estranged the population from the Communist dictatorship. When in April the Romanians invaded Hungary and the expected assistance from Soviet Russia failed to materialize,† Hungarian disenchantment was complete. On August 1, Kun fled to Vienna, his government resigned, and the Romanians occupied Budapest‡ Communism was thoroughly discredited in Hungary and persecuted under the rule of Admiral Nicholas Horthy, who in March 1920 became Regent and head of state.

While still in power in June, Bela Kun tried to stage a putsch in Vienna, employing for the purpose a Budapest lawyer, Ernst Bettelheim, whom he supplied generously with counterfeit banknotes. The only accomplishment of the Viennese Communists was to set fire to the Austrian parliament.

Thus, the three efforts to stage revolution in Central Europe at a time when the conditions for it were especially propitious went down in defeat. Moscow, hailing each as the beginning of world conflagration, had stinted neither on money nor on personnel. It gained nothing. European workers and peasants turned out to be made of very different stuff from their Russian counterparts. One could blame Communist failures on specific tactical mistakes, but ultimately they were due to the futility of trying to transfer the Russian experience to Europe:

Lenin had completely misjudged the psychology of the working classes in Germany, Austria and Western Europe. He misunderstood the traditions of their Socialist movements and of their ideologies. He failed to grasp the real balance of power in these countries and thus deceived himself not only about the speed of revolutionary development there, but also about the very character of the revolutions when … they did break out in the countries of the Central Powers. He had assumed that they would evolve along the same lines as the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia; that the left wing in the labor movements would split away from the Social Democrat[ic] parties, and would form Communist parties, which then, in the course of the revolutionary processes, would capture the leadership of the working class from the Socialist parties, overthrow parliamentary democracy and set up a dictatorship of the proletariat.19

Indeed, these attempts at social revolution in Europe achieved the very opposite result of that intended: they discredited Communism and played into the hands of nationalist extremists who exploited the population’s xenophobia by stressing the role of foreigners, especially Jews, in inciting civil unrest. In Hungary, the collapse of Bela Kun’s regime led to bloody anti-Jewish pogroms, and in Germany the Communist revolts gave credibility to the anti-Semitic propaganda of the nascent National-Socialist movement. It is difficult to conceive how right-wing radicalism, so conspicuous in interwar Europe, could have flourished without the fear of Communism, first aroused by the putsches of 1918–19: “The main results of that mistaken policy were to terrify the Western ruling classes and many of the middle classes with the specter of revolution, and at the same time provide them with a convenient model, in Bolshevism, for a counterrevolutionary force, which was fascism.”20

In the spring of 1919, Communist activities abroad were given a more organized structure in the form of the Communist International (Komintern or Comintern). The new International was designed as a militant vanguard whose mission was to accomplish around the globe what the Bolshevik Party had achieved in Russia. The task was spelled out in its resolution: “The Communist International sets for itself the goal of fighting, by every means, even by force of arms, for the overthrow of the international bourgeoisie and the creation of an international Soviet republic.”21 A related assignment was defensive, namely preventing a capitalist “crusade” against Soviet Russia by arousing the “masses” abroad against intervention. The Comintern was to prove much more successful in its defensive than its offensive missions.

In the first year of its existence (1919–20), the Comintern assigned the highest priority to combatting Social Democracy. For Lenin, the assault on “bourgeois” regimes required disciplined cadres of workers and worker leaders, organized on the model of the Russian Bolshevik party. These cadres were in short supply in Europe because the socialist and trade union organizations there were dominated by “renegades” and “social chauvinists” who collaborated with the “bourgeoisie”: hence the importance of splitting Social Democracy and detaching from it the truly revolutionary elements. This held especially true of Germany, a pivotal country in Lenin’s strategy, as it had the world’s strongest and best-organized socialist movement. As we shall see, to subvert the German Social-Democratic Party, Moscow was prepared to enter into partnership even with the most reactionary and nationalistic elements. It has been said that Lenin hated Karl Kautsky, the Nestor of German Social Democrats, more passionately than he did Winston Churchill.22

Lenin had decided to form a new International as early as July 1914, in response to the Second (Socialist) International’s betrayal of pledges to oppose the war. The rudiments of what became the Comintern can be discerned in the so-called “Left opposition” at the Zimmerwald and Kiental conferences (1915–16), at which Lenin and his lieutenants sought, with only partial success, to deflect the antiwar socialists from pacifism to a program of civil war.23

Although the formation in Bolshevik Russia of a new International was a foregone conclusion, in the first year and a half in power Lenin had more pressing matters to attend to. During this time the sporadic efforts at foreign subversion were orchestrated by the Commissariat of Foreign Affairs, which formed special foreign branches for this purpose under Radek. Their personnel was assembled quite casually. According to Angelica Balabanoff, who in 1919 served as Secretary of the Comintern, they “were practically all war prisoners in Russia: most of them had joined the Party recently because of the favor and privileges which membership involved. Practically none of them had had any contact with the revolutionary or labor movement in their own countries, and knew nothing of Socialist principles.”24

While World War I was on, these agents, supplied with abundant money, were sent, under cover of diplomatic immunity, to friendly Germany and Austria as well as to neutral Sweden, Switzerland, and Holland, to establish contacts and carry on propaganda. According to John Reed, in September 1918 the Commissariat of Foreign Affairs had on its payroll 68 agents in Austria-Hungary and “more than that” in Germany, as well as an indeterminate number in France, Switzerland, and Italy.25 The Commissariat also employed for such purposes Red Cross personnel and the repatriation missions sent to Central Europe after the Brest-Litovsk Treaty to arrange for the return of Russian POWs.

In March 1919 responsibility for foreign subversion was transferred to the Communist International. The immediate stimulus for the creation of the new body was the decision of the Socialist International to convene in Berne its first postwar conference. To counter this move, Lenin hastily convened in the Kremlin on March 2 a founding Congress of his own International. Because difficulties of transport and communication prevented direct communication with potential supporters abroad, the gathering turned into something of a farce, in that the majority of the delegates were either Russian members of the Communist Party or foreigners living in Russia, hardly any of whom represented genuine foreign organizations. Of the 35 delegates, only five came from abroad and only one (the German Hugo Eberlein-Albrecht) carried a mandate.* Boris Reinstein, a Russian-born pharmacist who had returned to his place of birth from the United States to help the Revolution and posed as the “representative of the American proletariat,” was accorded five mandates although he represented no one but himself. The affair in some respects recalled an amusing episode of the French Revolution when a group of foreigners living in France were garbed in native costumes and introduced to the National Assembly as “representatives of the universe.”†

The expectations of the Comintern’s founders knew no bounds: the All-Russian Congress of Soviets in December 1919 proclaimed its establishment “the greatest event in world history.”26 Zinoviev, whom Lenin appointed the Comintern’s Chairman, wrote in the summer of 1919:

The movement advances with such dizzying speed that one can confidently say: in a year we shall already forget that Europe had had to fight a war for Communism, because in a year all Europe shall be Communist. And the struggle for Communism shall be transferred to America, and perhaps also to Asia and other parts of the world.27

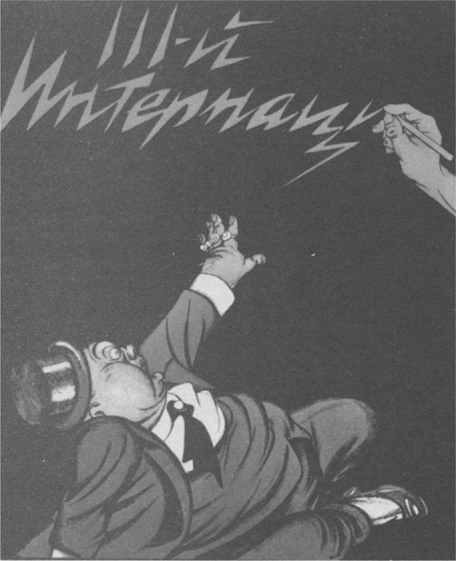

25. The capitalist pig squirming: the sign reads “Third International.”

Three months later, on the second anniversary of the October coup, Zinoviev expressed the hope that by the time of the third anniversary “the Communist International will triumph in the entire world.”28

According to Zinoviev, during its first year his organization was no more than a “propaganda association.”29 But this statement cannot be taken at face value because a great deal of Comintern activity was clandestine. It happens to be known, for instance, that the head of the Soviet Red Cross Mission in Vienna gave local Communists 200,000 crowns with which to found their organ, Weckruf.30 Since for the Bolsheviks newspapers were nuclei of political organizations, such action represented more than mere propaganda.

26. Lenin in May 1920.

Lenin addressed himself seriously to the Communist International only in the summer of 1920, when the Civil War was for all practical purposes over. His concept was simple: to make the Comintern into a branch of the Russian Communist Party, identically structured and, like it, subject to the directives of the Central Committee. In pursuit of this objective, he brooked no opposition: resistance to the principle of “democratic centralism” served Lenin as grounds for expulsion. Zinoviev defined this oxymoron to mean “the unconditional and requisite obligatory force of all instructions of the superior instance for the subordinate one.”31 Objections to it by foreign Communists Lenin discounted as Menshevik twaddle.

At the request of Zinoviev, who wished to placate the restless workers in his charge, the Second Congress of the Comintern opened on July 19, not in Moscow but in Petrograd. The decision to do so was kept secret to the last moment in order to avert potential assassination attempts against Lenin. Lenin traveled at night in an ordinary passenger train.* Four days later the Congress resumed in Moscow, where it sat until August 7. Foreign representation was far better this time. Present were 217 delegates from 36 countries, 169 of them eligible to vote. Next to the Russians, who had one-third (69) of the delegates, the largest foreign deputations came from Germany, Italy, and France. The casual way in which “national” representations were sometimes selected is evident in the fact that Radek, who in 1916 at the Kiental Conference had been listed as a spokesman of the Dutch proletariat, and in March 1919 had served as the envoy of the Soviet Ukraine to Germany, now appeared as the representative of the workers of Poland.32 The Bolsheviks ran into considerable resistance to their program from foreigners, but in the end nearly always had their way. The mood of the Congress was euphoric, because while it was in session the Red Army was advancing on Warsaw: it seemed virtually certain that a Polish Soviet Republic would soon come into being, to be followed by revolutionary upheavals in the rest of Europe. In something close to revolutionary delirium, Lenin on July 23 cabled to Stalin, who was in Kharkov, a coded message:

The situation in the Comintern is superb. Zinoviev, Bukharin and I, too, think that the revolution should be immediately exacerbated in Italy. My own view is that to this end one should sovietize Hungary and perhaps also Czechoslovakia and Romania. This has to be carefully thought out. Communicate your detailed conclusion.33

This extraordinary message can be understood only in the context of a decision taken in early July 1920, in the midst of a war with Poland, to carry the revolution to Western and Southern Europe. As has become known recently with the publication of a major speech by Lenin to a closed meeting of Communist leaders in September of that year, the Politburo resolved not merely to expel the Poles from Soviet territory and not merely to Sovietize Poland, but to use the conflict as a pretext for opening a general offensive against the West.

Poland declared her independence in November 1918. The Versailles Treaty recognized her sovereignty and defined her western borders. But the shape of Poland’s frontier with Russia had to be held in abeyance until the Russian Civil War had been resolved one way or another and there was a recognized Russian government with which to negotiate the matter. In December 1919, the Supreme Allied Council drew up a provisional frontier between the two countries based on ethnographic criteria which came to be known as the “Curzon Line.” The Poles rejected it since it deprived them of territories in Lithuania, Belorussia, and Galicia to which they felt entitled on historical grounds.* In fact, by the time the Curzon Line was drawn, Polish armies were already 300 kilometers to the east of it. Pilsudski was determined to seize as much territory from Russia as possible while that country was in the throes of Civil War and unable to resist. His armies occupied Galicia, dislodging from there a Ukrainian government, following which they expelled Bolshevik forces from Vilno. In mid-February 1919, Polish and Soviet troops fought skirmishes which marked the onset of a de facto state of war. Pilsudski, however, did not immediately press his advantage because, for reasons previously stated, he wanted to give Moscow the opportunity to defeat Denikin, to which end in the fall of 1919 he ordered his troops to suspend operations against the Red Army. He only waited for Denikin to be out of the picture to resume the offensive.

Pilsudski probably could have secured at this time advantageous peace terms from Moscow. But he had very ambitious geopolitical plans, which, as events were to show, vastly exceeded the capabilities of the young Polish republic.

The outbreak of the Polish-Russian war is commonly blamed on the Poles and it is indisputable that their troops started it by invading, at the end of April 1920, the Soviet Ukraine. However, evidence from Soviet archives raises the possibility that if the Poles had not attacked when they did the Red Army might have anticipated them. The Soviet High Command began to plan offensive operations against Poland already at the end of January 1920.34 The Red Army assembled a strong force north of the Pripiat marshes with the intention of sending them into action no later than April.35 The principal front was to advance against Minsk, while a secondary, southern front was to aim at Rovno, Kovel, and Brest-Litovsk. The ultimate objective of the campaign was kept secret even from the front commanders: but from instructions issued by S. S. Kamenev that once inside Poland the two fronts were to link up, there can be little doubt that the next phase would have carried the offensive to Warsaw and farther west.36 The hypothesis of Soviet plans for an invasion of Poland is reinforced by a recently declassified cable dated February 14, 1920, from Lenin to Stalin, who was with the Southern Army in Kharkov, requesting information on the steps being taken to “create a Galician striking force.”37

The Polish assault disrupted these plans, which, as will be clear from Lenin’s retrospective analysis discussed below, were meant to begin a general offensive on Western Europe.

In March 1920, Pilsudski proclaimed himself Marshal and took personal charge of the 300,000 troops deployed on the Eastern front. During March and April 1920, the Poles carried out negotiations with Petlura, which on April 21 resulted in a secret protocol. Poland recognized Petlura as head of an independent Ukraine and promised to restore Kiev to him. In exchange, Petlura acknowledged eastern Galicia as belonging to Poland.* The diplomatic agreement was supplemented on April 24 by an equally secret military convention providing for joint operations and the eventual withdrawal of Polish troops from the Ukraine.38

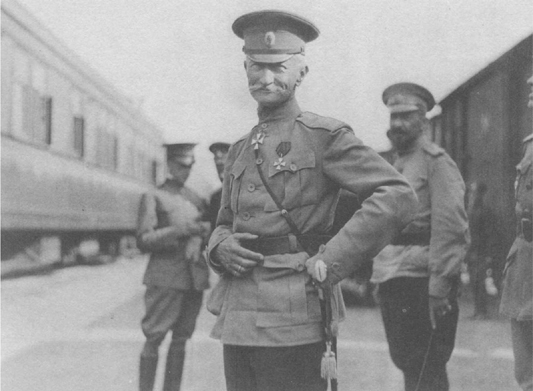

27. Brusilov during World War I.

The Polish army, made of troops that had fought on opposite sides in the World War, was high in spirits but low on equipment. The British refused help on the grounds that they had done their share by supporting the Whites, and Poland was France’s responsibility. The French, as was their custom, gave nothing for nothing: instead of outright aid, they offered the Poles credit of 375 million francs with which to purchase, at current market prices, surplus war matériel, some of it captured from the Germans. The United States offered credit of 56 million dollars to buy stocks left behind by its army in France.39

On April 25, a numerically superior Polish army, assisted by two Ukrainian divisions, struck at Zhitomir in the direction of Kiev.* Although it had been preparing for action since January, the Twelfth Red Army fell back, weakened by mutinies and defections, especially among its Ukrainian units. The Red forces also had to contend with effective partisan activity in their rear. On May 7 the Poles occupied the Ukrainian capital: it is said to have been the fifteenth change of regime in Kiev in three years. The total Polish losses up to that point were 150 dead and twice that number wounded.

Poland’s triumph was short-lived. The expected rising of the Ukrainian population did not occur. Instead, the invasion ignited a patriotic frenzy in Russia that rallied socialists, liberals, and even conservatives behind the Communist regime that was defending the country from foreign aggressors. On May 30, the Soviet press carried an appeal by the ex-tsarist general Aleksei Brusilov, the commander of Russia’s 1916 offensive, urging all ex-Imperial officers who had not yet done so to enroll in the Red Army.*

On June 5–6, Budennyi’s cavalry broke through the Polish lines. The Poles abandoned Kiev on June 12 and retreated as rapidly as they had advanced. The Soviet counteroffensive proceeded on two fronts, separated by the impassable Pripiat marshes. The southern army advanced on Lwow; the northern one, under Tukhachevskii, crossed into Belorussia and Lithuania. On July 2, Tukhachevskii issued an order to his troops: “Over the corpse of White Poland lies the path to world conflagration.… On to Vilno, Minsk, Warsaw! Forward!”40 Flushed with victory, on July 11 the Red Army took Minsk, the capital of Belorussia, and three days later Vilno. Grodno fell on July 19, and Brest-Litovsk on August 1. By then, Pilsudski’s troops had lost all the territory they had conquered since 1918: the Red Army stood on the Bug River, the eastern boundary of the Polish population, poised to invade Poland proper. In all the occupied areas, Soviet methods of rule were introduced.

In Poland, the military reverses precipitated a political crisis. Under pressure from those who had all along opposed the Ukrainian adventure, and they were on both the right and the left of the political spectrum, the Polish government on July 9 advised the Allies that it was prepared to give up territorial claims against Soviet Russia and to negotiate a peace settlement.41 Curzon immediately passed on to Moscow the Polish offer, suggesting a truce along the Bug as a provisional frontier, a permanent one to be worked out later. Britain offered her services as mediator. Curzon accompanied these proposals with a warning that if the Russians invaded ethnic Poland, Britain and France would intervene on her behalf.

Curzon’s note produced disagreements in Bolshevik ranks. Lenin, supported by Stalin and Tukhachevskii, wanted to reject the Polish offer and to ignore the British warning: the Red Army should march on Warsaw. He was convinced that the appearance of Red soldiers and the proclamation of Bolshevik decrees favorable to workers and peasants would cause the Polish masses to rise against their “White” government and permit the installation of a Communist regime.

But behind Lenin’s decision lay far weightier motives. What these were, he explained to a closed meeting at the Ninth Conference of the Russian Communist Party on September 22, 1920, at which he sought to explain and justify what he called “the catastrophic defeat” which Soviet Russia had suffered in Poland. Lenin requested that his remarks be neither recorded nor published, but the stenographers kept on working: the text appeared in print seventy-two years later.* Although the formal objective of carrying the war into ethnic Poland had been Sovietizing that country, Lenin explained in his typically rambling fashion, the true objective was far more ambitious:

28. Tukhachevskii.

We confronted the question: whether to accept [Curzon’s] offer, which gave us convenient borders, and by so doing, assume a position, generally speaking, which was defensive, or to take advantage of the enthusiasm in our army and the advantage which we enjoyed to help Sovietize Poland. Here stood the fundamental question of defensive and offensive war, and we in the Central Committee realized that this is a new question of principle, that we stood at the turning point of the entire policy of the Soviet government.

Until that time, waging war against the Entente, we realized—since we knew only too well that behind each partial offensive of Kolchak [or] Iudenich stood the Entente—that we were waging a defensive war and were defeating the Entente, but that we could not decisively defeat it since it was many times stronger.…

And thus … we arrived at the conviction that the Entente’s military attack against us was over, that the defensive war against imperialism was over: we won it.… The assessment went thus: the defensive war was over (Please record less: this is not for publication)….

We faced a new task.… We could and should take advantage of the military situation to begin an offensive war.… This we formulated not in the official resolution recorded in the protocols of the Central Committee … but among ourselves we said that we should test with bayonets whether the socialist revolution of the proletariat had not ripened in Poland.…

[We learned] that somewhere near Warsaw lies not the center of the Polish bourgeois government and the republic of capital, but the center of the whole contemporary system of international imperialism, and that circumstances enabled us to shake that system, and to conduct politics not in Poland but in Germany and England. In this manner, in Germany and England we created a completely new zone of proletarian revolution against global imperialism.…

Lenin went on to explain that the advance of the Red Army into Poland set off revolutionary upheavals in Germany and England. On the approach of Soviet troops, German nationalists made common cause with Communists, and Communists formed volunteer armed units to help the Russians. In Great Britain, the emergence of a “Council of Action” (see next page) seemed to Lenin the beginning of a social revolution: he thought that in the summer of 1920, England was in the same situation as Russia in February 1917, and that the government had lost control of the situation.

Nor was this all, Lenin continued. The southern Red Army, by advancing into Galicia, established direct contact with Carpathian Rus’, which opened up possibilities of carrying the revolution to Hungary and Czechoslovakia.

The overthrow of Poland offered a unique opportunity to liquidate the entire Versailles settlement. Both on this occasion and on others, Lenin justified the invasion of Poland as follows: “By destroying the Polish army we are destroying the Versailles Treaty on which nowadays the entire system of international relations is based.… Had Poland become Soviet … the Versailles Treaty, … and with it the whole international system arising from the victories over Germany, would have been destroyed.”*

In short, Poland was but a stepping-stone from which to launch a general assault on western and southern Europe and to rob the Allies of the fruits of their victory in World War I. This goal, of course, had to be concealed: Lenin admitted that his government had to pretend it was interested only in Sovietizing Poland. The historian can but marvel at the utter lack of realism behind these assessments: as is often the case, fanaticism employs cunning means for quixotic purposes.

Trotsky took issue with Lenin’s offensive strategy: he thought it advisable to accept the British mediation offer and urged that a pledge be given of respect for Poland’s† sovereignty. In this, he enjoyed the backing of the Red High Command, which felt confident that it could crush the Polish army in two months, but only if assured that the Allies would not intervene militarily; in view of the British warning, however, and the possibility of Romanian, Finnish, and Latvian involvement, it recommended that offensive operations be suspended at the Curzon Line.42 The party’s leading experts on Poland, Radek and Marchlewski, cautioned against expectations that Polish workers and peasants would welcome the Russian invaders.

As was usually the case, Lenin’s view prevailed. On July 17, the Central Committee resolved to carry the war into Poland, following which Trotsky and S. S. Kamenev instructed the commanders to ignore the Curzon Line and advance westward.43 Britain was sent a polite note rejecting its offer of mediation.44 On July 22, Kamenev ordered that Warsaw be taken no later than August 12. A five-man Polish Revolutionary Committee (Polrevkom) was formed under Dzerzhinskii and Marchlewski to administer Sovietized Poland. Moscow received a great deal of encouragement from the condemnation of the Polish government by Britain’s Labour Party. On August 12, a conference of trade unions and the Labour Party voted to order a general strike should the government persist in its pro-Polish and anti-Soviet policy. To implement this decision, a Council of Action was formed under the chairmanship of Ernest Bevin. These developments made British intervention highly unlikely. At the same time, the Bureau of the International Federation of Trade Unions in Amsterdam, an affiliate of the Second (Socialist) International, instructed its members to enforce an embargo on ammunition destined for Poland.45

In the midst of these military and political engagements, the Second Congress of the Comintern opened its sessions. A large map of the combat zone was posted in the main hall, and the westward advance of the Red Army marked daily to the cheers of the delegates.

At the Second Congress of the Comintern, Lenin pursued three objectives: first, the creation in every foreign country of Communist parties: these were to be formed either from scratch or by splitting existing socialist parties. This, the most urgent task, was to be accompanied by the destruction of the Socialist International. In its resolutions, the Congress asserted that foreign Communist parties were to impose on their members “iron military discipline” and require “the fullest comradely confidence … in the party Center,” that is, unquestioned obedience to Moscow.46

Second, Unlike the Socialist International, which was structured as a federation of independent and equal parties, the Comintern was to follow the principle of “iron proletarian centralism”: it was to be the exclusive voice of the world’s proletariat. In the words of Zinoviev: the International “must be a single Communist Party, with sections in different countries.”47 Each foreign Communist Party was subordinate to the Comintern Executive (IKKI). The Comintern Executive, in turn, was a department of the Central Committee of the Russian Communist Party, whose directives it was required to carry out.* To ensure absolute control, the Russian Communist Party allocated to itself five seats on the Executive; no other party was assigned more than one. The principal criterion in selecting Comintern executives was obedience to Moscow. Parties and individual members, no matter how prominent, who disobeyed the Executive risked expulsion. To make certain that foreign Communist parties followed its orders, the Executive was authorized to establish abroad supervisory organs, independent of local Communist organizations.

29. Lenin and his secretary, Stasova, at the Second Congress of the Comintern.

Third, the immediate task of foreign Communist parties was to infiltrate and seize control of all mass worker organizations, including those committed to “reactionary” policies, along with all “progressive” organizations. According to Lenin’s instructions, Communist cells were to be planted in every body of a mass character, openly where appropriate, secretly where not.48

The ultimate mission of the Comintern was “armed insurrection” against the existing governments49 for the purpose of replacing them with Communist regimes, preparatory to the establishment of a worldwide Soviet Socialist Republic.

Lenin’s exceedingly authoritarian proposals antagonized the foreign delegations, which admired Bolshevik achievements and objectives but knew little of Bolshevik ways. Lenin had to battle two groups: those who objected to his “opportunism” in seeking to work within the framework of parliaments and trade unions, and those who resented his undemocratic procedures in the Comintern.

Some foreign Communists, inspired by the Russian example, wanted to launch an immediate and direct assault on their governments: they saw no advantage to the tactic of gradual infiltration of the enemy’s institutions advocated by Lenin. In a pamphlet distributed at the Second Congress, Leftism, an Infantile Disease of Communism, Lenin rejected this strategy on the grounds that the Communists abroad were too few and too weak to go on the offensive. The correlation of forces required them to follow a patient strategy of exploiting every disagreement in the enemy camp and entering into temporary alliances with every potential ally.50 Foreign delegates who questioned this approach were rebuked by the Russians and on occasion prevented from speaking.

In line with Lenin’s policy of infiltration, the Comintern Executive insisted that foreign Communist parties take part in parliamentary elections.51 Some delegations, led by the Italians, opposed this demand on the grounds that by so doing they would only reveal the small size of their following, but Lenin stood his ground: he had not forgotten the mistake he had committed in 1906 when he ordered the Bolsheviks to boycott elections to the First Duma. As he saw it, winning elections was less important than using parliamentary immunity to discredit national governments and spread Communist propaganda. Emulating the tactics adopted by the Russian Social-Democrats and Socialists-Revolutionaries in 1907, he had Bukharin force through a resolution requiring Comintern affiliates to “make use of bourgeois governing institutions for the purpose of destroying them.”52 To ensure that foreign parties did not succumb to what Marx called “parliamentary cretinism,” Communist legislators were required to combine parliamentary work with illegal activity. According to the resolutions of the Second Congress,

Every Communist parliamentary deputy must bear in mind that he is not a legislator who seeks understanding with other legislators, but an agitator of the party, sent into the enemy camp to implement party decisions. The Communist deputy is accountable not to the amorphous body of voters but to his legal or illegal Communist party.53

There was much wrangling over policy toward trade unions. For Lenin, infiltrating and subverting unions was the second most important item on the Comintern’s agenda, since the support of organized labor was a sine qua non of European revolution. This, however, would perforce be a formidable task, given that organized labor in the West was overwhelmingly reform-minded and affiliated with the Second International. European trade unionists present at the Second Congress argued in vain that their organizations were entirely unsuited for revolutionary work, since their members were interested in economic, not political, objectives. The strongest opposition came from the British and American delegations. The British resented being told to join the Labour Party since they knew it would not admit Communists and that an application for membership would only cause them embarrassment. John Reed, an American admirer of the Bolsheviks, was prevented from speaking when he tried to object to American Communists seeking affiliation with the American Federation of Labor. When he was finally allowed to make a motion, the vote on it was not even entered in the official record.54 In protest against such undemocratic methods he later resigned from the Comintern.

A half-hearted attempt was made to move the headquarters of the Comintern. It had been the Bolsheviks’ original intent to locate the Third International in Western Europe, but they abandoned the idea from fear of sharing the fate of Luxemburg and Liebknecht.55 The Dutch delegate, who had suggested Norway as the Executive’s permanent seat, said after his motion had been defeated that the Congress should not pretend that it had created a truly international body, because in fact it had vested “the executive authority of the International in the hands of the Russian Executive Committee.”56 The Comintern Executive established itself in Moscow in the luxurious residence of a German sugar magnate that in 1918 had been home to the German embassy.

Before adjourning, the Second Congress adopted its most important document, containing 21 “Conditions” or “Points” for admission to the Comintern. Lenin, its author, deliberately formulated the requirements for membership in an uncompromising manner in order to make them unacceptable to moderate socialists. The most important conditions were the following:

Article 2. All organizations belonging to the Comintern were to expel from their ranks “reformists and centrists”;

Article 3. Communists had to create everywhere “parallel illegal organizations,” which, at the decisive moment, would surface and assume direction of the revolution;

Article 4. They were to carry out propaganda in the armed forces to prevent them from being used for purposes of the “counterrevolution”;

Article 9. They were to take over trade unions;

Article 12. They were to be organized on the principle of “democratic centralism” and to follow strict party discipline;

Article 14. They were to help Soviet Russia repel the “counterrevolution”;

Article 16. All decisions of Comintern Congresses and the Comintern Executive were binding on member-parties.*

Why did the delegates to the Second Congress of the Comintern, despite doubts and resentments, in the end vote with near-unanimity for rules that deprived them of all independence? They did so in part from admiration of the Bolsheviks, who, in their eyes, had carried out the first successful social revolution in history and, therefore, seemed to know what was best. But it has also been suggested that being only superficially acquainted with Bolshevik theory and practice, they did not realize what these requirements entailed.57

When the Second Congress of the Comintern adjourned, the fall of Warsaw and the establishment of a Polish Soviet Republic seemed a foregone conclusion. The Polish army was falling back at the rate of 15 kilometers a day: it was dispirited, disorganized, and lacking in basic supplies. It was also vastly outnumbered: by Pilsudski’s estimates, the Red Army in Poland had 200,000 to 220,000 combat troops, while the Polish forces had been reduced to 120,000.58 But the Poles enjoyed a geographic advantage when on the defensive, in that the invading Red Army had to divide itself in two, one north of the Pripiat marshes, the other south of it, whereas the Polish army could operate as one integrated body.59

German military circles rejoiced at the prospect of Poland’s imminent destruction: like Lenin, they believed that its collapse spelled the doom of Versailles. The Weimar government, having declared neutrality in the Soviet-Polish war, on July 25 rejected a French request for permission to ship military supplies for Poland across Germany. Czechoslovakia and Austria followed suit, which had the effect of virtually cutting Poland off from her Western allies.

On July 28, the Red Army occupied Bialystok, the first major Polish city west of the Curzon Line. Two days later the Polish Revolutionary Committee (Polrevkom) issued a proclamation informing the population that it was “laying the foundations of the future Polish Soviet Socialist Republic,” to which end it has “removed the previous gentry-bourgeois government.” All factories, land (except for peasant holdings), and forests were declared national property.60 Revolutionary Committees and soviets were organized in all localities occupied by the Red Army. In communicating with his agents in Poland, Lenin urged the “merciless liquidation of landlords and kulaks … also real help to peasants [to seize] landlord land, landlord forest.”61 Lenin conceived what he called a “beautiful plan” of hanging “kulaks, priests, and landowners” and pinning the crime on the “Greens”; he further suggested paying a bounty of 100,000 rubles for each killed class enemy.62 But the differences in political culture between Poland and Russia soon became apparent, as did the futility of appealing to primitive anarchist emotions in a different, more Western environment, for neither Polish workers nor Polish peasants responded to exhortations to loot and kill. On the contrary: faced with foreign assault, Poles of all classes closed ranks. To its surprise, the invading Red Army met with hostility from Polish workers and soon had to defend itself from partisan bands.

The invading force was organized in a Southwestern front under Egorov, composed of the Twelfth Army and Budennyi’s cavalry, and a Western front under Tukhachevskii, made up of four armies—the Third, Fourth, Fifteenth, and Sixteenth—reinforced by the Third Cavalry Corps of General G. D. Gai Bzhiskian, a Persian-born Armenian veteran of the tsarist army. Stalin was attached to the Southwestern Army as political commissar. (He was originally assigned to Budennyi’s cavalry by Trotsky.)63 Stalin urged the Politburo to concentrate the main thrust of the offensive in the southern sector. He was overruled. On August 2, the Politburo ordered Egorov’s infantry along with Budennyi’s cavalry to pass under Tukhachev-skii’s command.64 But, under circumstances which are far from clear, Kamenev, Stalin’s protégé, delayed implementing this decision. It was only on August II that he ordered a temporary suspension of the operation against Lwow, and appointed Tukhachevskii Commander in Chief of both the Western and Southwestern fronts. The Twelfth Army and Budennyi’s cavalry were to proceed toward Warsaw.65 Stalin refused to follow these instructions.66 According to Trotsky, his insubordination contributed materially to the Red Army’s defeat in Poland.67

The hard-pressed Poles pleaded with the Allies for supplies. Lloyd George, who was in the midst of commercial negotiations with Soviet representatives Krasin and Lev Kamenev, lectured them on the aggression and even gave them an ultimatum, but Lenin, correctly sensing that the British were not about to break relations with him over Poland, called his bluff.68 The British Trade Union’s Council of Action, subsidized by the Soviet authorities (it received the proceeds from the sale of jewels smuggled into England by Kamenev),69 stopped shipments of war materiel to Poland by repeating its threat of a general strike. British dockers refused to load cargoes destined for Poland.

Such scanty assistance as the Poles received came from France. Some supplies were delivered by way of Danzig, then under British control, but French help consisted mainly of training and advice. Several hundred French officers who had arrived earlier in the year to instruct Polish troops were now joined by a military mission, headed by General Maxime Weygand, the Chief of Staff of Marshal Ferdinand Foch, the Commander in Chief of Allied Forces in France in 1918. Weygand expected to assume command of the Polish forces, but this was denied to him. Although he and his staff subsequently received much if not most of the credit for the “Miracle on the Vistula,” in reality they contributed next to nothing to the victory for the simple reason that they were kept in isolation and their strategic plan, calling for a defensive stance, was rejected.70 Weygand himself disclaimed credit for the defeat of the Red Army: “This is a purely Polish victory,” he said after the event. “The preliminary operations were carried out in accordance with Polish plans made by Polish generals.”71 The French mission has been aptly described as “a symbolic substitute for [the] material aid that the Allies were unwilling or unable to supply.”72

On August 14, Trotsky ordered the Red Army to take Warsaw without delay. Two days later, the Polrevkom moved to a location 50 kilometers from the Polish capital, expecting to enter it in a matter of hours. Warsaw was unperturbed: even as the sound of artillery could be heard in the capital, its inhabitants calmly went about their business. A British diplomat reported on August 2 that the “insouciance of the population here is beyond belief. One would imagine the country in no danger, and the Bolsheviks a thousand miles away.”73

At this critical point in the war, Tukhachevskii committed fatal strategic blunders. Instead of concentrating forces on Warsaw, which he apparently considered to be his for the asking, he dispatched the Fourth Army, together with the Cavalry Corps, northwest of Warsaw—in Pilsudski’s words, “into a void.”74 His apparent intention was to sever communications between Warsaw and Danzig in order to prevent Allied supplies from reaching the beleaguered city.* Later he would claim that he meant to encircle Warsaw from the north and west. But evidence from recently opened Russian archives suggests that he was acting on orders from above and that the purpose of the operation was political: to occupy the Polish Corridor and turn it over to the Germans, reuniting East Prussia with the rest of Germany, thereby winning over nationalist circles there. “The approach of our troops to the borders of East Prussia, which is separated by the Polish corridor … showed that all Germany began to seethe,” Lenin said in his September 19, 1920, speech. “We received information that tens and hundreds of thousands [!] of German Communists crossed the border. Telegrams came about the formation of German Communist regiments. It was necessary to pass resolutions to prevent the publication (of this information) and to continue declaring that we were waging war (with Poland).”*

Polish-Soviet War, 1920

POLISH OFFENSIVE (APRIL–MAY 1920)

No less disastrous was the gap which was allowed to develop between Tukhachevskii’s main force, besieging Warsaw, and the Red Army’s left wing (the Twelfth Army and Budennyi’s cavalry) commanded by Egorov and politically supervised by Stalin. Here a front 100 kilometers long was defended by a mere 6,600 troops. In the historical literature, in no small measure owing to the claims of Trotsky, the blame for this mistake is placed on Stalin, who, it is said, had ambitions of his own and wanted to occupy Lwow before Tukhachevskii took Warsaw, and hence failed to come to the latter’s aid. But in view of Lenin’s emphasis on the need to revolutionize South Central and Southern Europe, as stated both in his secret speech and in his cable to Stalin (above, this page), it seems more likely that this strategic blunder, too, was committed by Lenin, who apparently wanted Egorov’s army to take Galicia as a base from which to invade Hungary, Romania, and Czechoslovakia, while Tukhachevskii marched on Germany.

Soviet Counteroffensive and Polish Breakthrough

(JULY–AUGUST 1920)

Pilsudski quickly seized the opportunities presented to him by the Red Army’s mistakes. He formulated his daring plan for a counterattack during the night of August 5–6.75 On August 12, he left Warsaw to assume command of a secretly formed striking force of some 20,000 men, assembled south of the capital. On August 16, two days after the Russians had launched what was to have been the final assault on the Polish capital, he struck, sending this force through the gap, northward, to the rear of the main Red force. The counteroffensive caught the Red command by complete surprise. The Poles advanced for 36 hours without encountering resistance: Pilsudski, fearing an ambush, frantically toured the front in his car, looking for the enemy. To avoid having his armies trapped, Tukhachevskii ordered a general retreat. The Poles took 95,000 prisoners, including many soldiers who only recently had seen service with the Whites: a British diplomat who inspected them had the impression that nine-tenths of the captives were “good natured serfs,” the rest “fanatical devils.” Questioning revealed that the majority were indifferent toward the Soviet regime, respected Lenin, and despised and feared Trotsky.76

In the battles that followed the “Miracle on the Vistula,” of the five Soviet armies that had invaded Poland, one was annihilated and the remainder were severely mauled: the remnants of the Fourth Army and Gai’s Cavalry Corps crossed into East Prussia, where they were disarmed and interned. Estimates are that two-thirds of the invading force suffered destruction.77 Stragglers were hunted down by Polish peasants. Budennyi’s cavalry, retreating, assisted by two Red infantry divisions, distinguished itself by carrying out massive anti-Jewish pogroms. Lenin received a detailed account of these atrocities from Jewish Communists, describing the systematic annihilation of entire Jewish settlements and urgently requesting help. He noted on the margin: “Into the Archive.”78 After Trotsky had visited the collapsing front and reported to the Politburo, the latter with near-unanimity voted to seek peace.79 An armistice went into effect on October 18.

Instead of installing a Soviet government in Poland and from there spreading Communism to the rest of Europe, Moscow now had to enter into negotiations from which it emerged much worse off than if it had accepted the terms proposed by the Poles in July. On February 21, 1921, the Central Committee, hard-pressed by domestic unrest, decided to make peace with Poland as soon as possible.80 In the treaty concluded in Riga in March 1921, Soviet Russia had to surrender territories lying well to the east of the Curzon Line, including Vilno and Lwow.

The Soviet defeat in Poland profoundly affected Lenin’s thinking: it was his first direct encounter with the forces of European nationalism and he had emerged the loser. He was dismayed that the Polish “masses” did not rise to aid his army. Instead of meeting resistance only from Polish “White Guards,” the would-be Russian liberators confronted a united Polish nation. “In the Red Army the Poles saw enemies, not brothers and liberators,” Lenin complained to Clara Zetkin.

They felt, thought and acted not in a social, revolutionary way, but as nationalists, as imperialists. The revolution in Poland on which we counted did not take place. The workers and peasants, deceived by the adherents of Pilsudski and Daszynski, defended their class enemy, let our brave Red soldiers starve, ambushed them and beat them to death.*

The experience cured him of the fallacy that incitement to class antagonism, so successful in Russia, would always and everywhere override nationalist sentiments. It dissuaded him from sending the Red Army to fight on foreign soil. Chiang Kai-shek, who visited Moscow in 1923 as a representative of the Kuomintang, then an ally of the Communists, was told by Trotsky:

After the war with Poland in 1920 Lenin had issued a new directive regarding the policy of World Revolution. It ruled that Soviet Russia should give the utmost moral and material assistance to colonies and subcolonies in their revolutionary wars against capitalist imperialism, but should never again employ Soviet troops in direct participation so as to avoid complications for Soviet Russia during revolutions in various countries arising from questions of [nationalism].81

As soon as the Second Congress of the Comintern had adjourned, the Executive proceeded to implement its directives. Western Europe now witnessed a repetition of the events that twenty years earlier had destroyed the unity of Russian Social Democracy.

The Italian Socialist Party (PSI) was the only major socialist party in Europe to attend the Second Congress. The PSI was a genuine mass party and it was dominated by antireformists. In 1919 it had split into pro- and anti-Comintern factions. The majority, headed by G. M. Serrati, voted to affiliate with the Comintern: the PSI was the first foreign socialist party to join the new International. The minority, under Filippo Turati, opposed this decision, but for the sake of socialist unity submitted to it. As a result, the reformists were not ejected but remained in the PSI. Lenin found such tolerance unacceptable and insisted on the expulsion of the Turati faction. When Serrati refused, he became the object of a vicious slander campaign underwritten by the Comintern, including entirely baseless charges of bribery. It ended with his expulsion from the Comintern.82 Subsequently, the ultraradical minority of the PSI, bowing to Moscow’s wishes, broke away from the PSI to form the Italian Communist Party (PCI). In parliamentary elections a few months later, the PCI received only one-tenth of the votes cast for the Socialists. Despite their shabby treatment, the Italian socialists continued to consider themselves Communists and to profess solidarity with the Comintern. But the split in the PSI forced by Moscow weakened it appreciably and facilitated Mussolini’s seizure of power in 1922.

The French Socialist Party voted in December 1920 by a three-to-one majority to join the Comintern. This triumph enabled the Communists to seize control of the party’s organ, L’Humanité. The majority of 160,000 members now declared itself the Communist Party; the defeated minority retained the name of Socialist Party.

In Germany, the pro-Communist element was concentrated in the Independent Social-Democratic Party of Germany (USPD), founded in April 1917 by socialists opposed to the war. Its radical wing formed the Spartacus League. After the Armistice, the USPD gained considerable mass support. In March 1919, it came out in favor of introducing into Germany a Soviet-type government and the “dictatorship of the proletariat,” which made it a Communist party in all but name. The leaders of the USPD were prepared to join the Comintern, but had difficulty persuading the rank and file to subscribe to Lenin’s 21 Points. In the June 1920 elections, the USPD won 81 parliamentary seats, not markedly less than the Social-Democratic Party (SPD), which gained 113 seats and emerged as the second largest bloc in the Reichstag. The Communist Party (KPD), as the Spartacus League renamed itself, got only two parliamentary seats out of 462.83 The USPD took a final vote on the Comintern’s 21 Points in October 1920 at its Halle Congress, at which Zinoviev delivered an impassioned four-hour address. Ignoring the warnings of the Menshevik L. Martov, the delegates voted 236 to 156 to accept the 21 Points and join the Comintern. Of the 800,000 members in the USPD at the time, 300,000 enrolled in the German Communist Party, 300,000 remained in the USPD, and 200,000 left socialist ranks.84 The consequence of the Halle Congress vote was a split in a party that seemed on the verge of becoming the largest in Germany. The USPD lay in ruins, but Lenin attained his objective. The VKPD (United Communist Party of Germany), which resulted from the fusion of the KPD and the breakaway faction of the USPD, became the Comintern’s agency in Germany. It had approximately 350,000 members and constituted one of the largest Communist parties outside Soviet Russia.

When in March 1921 the Soviet government found itself in a crisis as a result of widespread peasant rebellions and the mutiny of the Kronshtadt naval base, it decided that a revolution in Germany could help it overcome domestic unrest. Disregarding the advice of the German Communist leaders, including Paul Levi and Clara Zetkin, it ordered a putsch. German workers did not stir and the uprising was readily crushed.85 In the aftermath, the membership of the United German Communist Party declined by one-half, to 180,000 members.86 Although they had been proven right in warning Moscow, Levi and Zetkin were forced out of both the Party and the Comintern.

The British Communist Party, formed in January 1921 of minuscule radical splinter groups, made up mostly of intellectuals and a small number of Scottish workers, in 1922 had only 2,300 members. Somewhat more numerous was the ILP (Independent Labour Party), with 45,000 members (1919), which, while in sympathy with the aims of the Comintern, refused to join. Lenin decided that British Communists could acquire greater influence by entering the Labour Party and subverting it from within. He persisted in this strategy despite Labour’s hostility, as evidenced in 1920 by an overwhelming defeat—nearly 3 million votes against 225,000—of a motion calling on it to join the Third International.87 He instructed British Communists to apply for admission, which they did, against their better judgment, only to meet with a humiliating rebuff: at the 1921 Labour Party Conference, the Communist Party’s application was rejected by a vote of 4.1 million to 224,000. This was repeated in 1922 and the following years.88 With their tiny membership, the British Communists had to live off subsidies secretly conveyed by the Comintern; and with financial dependence came servility.

The Czechoslovak Socialist Party, which had nearly half a million members, voted in March 1921 with virtual unanimity to join the Comintern.

The second objective of the Comintern in order of importance—penetrating and assuming control of the trade unions—proved more difficult to attain than creating Communist parties: it was easier to win the support of intellectuals dominant in political life than of workers in the trade unions. Lenin instructed his foreign followers to use any available means to gain controlling influence over organized labor. They must, he wrote, “in case of necessity … resort to every kind of trick, cunning, illegal expedient, concealment, suppression of truth, so as to penetrate into the trade unions, to stay in them, to conduct in them, at whatever cost, Communist work.”89 To promote this objective, Moscow founded in July 1921, at the Third Comintern Congress, a branch of the Communist International, subordinate to its Executive, called the Red International of Trade Unions, or “Profintern.”* Its mission was to lure away organized labor from the International Federation of Trade Unions (IFTU), an affiliate of the Socialist International with headquarters in Amsterdam, representing over 23 million workers in Europe and the United States.90 The Profintern experienced great difficulty in trying to make inroads into organized labor because Western trade unions were fully committed to ameliorating their members’ economic conditions, and had no interest in making revolution. It had the greatest success in France, where syndicalist traditions were strong. The largest French trade union organization, Confédération Générale du Travail (CGT) split in 1921, following which the pro-Communist minority (CGTU) joined the Profintern.

In other countries, the Communists managed to win over from the socialist movement only splinter groups.91 The latter typically came from declining or unstable sectors of the economy or “sunset industries,” like the marginal coal-mining industry of Britain and the waterfronts of Australia and some United States ports. Indeed, these toeholds were often the only ones obtained in those countries, exactly as the First International found its major support in Britain in the dying crafts and seldom in the characteristically capitalist large-scale industry of its day. On the Continent, in the 1930s at least, the Communist hold was in the smaller factories rather than in the bigger: “The bigger the factory, the smaller the communist influence; in the industrial giants it is altogether insignificant.”92

The attempts of the Comintern to take over organized European labor, mandated by Article 9 of the 21 Points, ended in failure: “During the next fifteen years [1920–1935] the communists in the West were unable to conquer one single union.”93

The fiasco, which both puzzled and frustrated Russian Communists, was principally due to cultural differences that they had difficulty grasping, for they had been weaned on an ideology that saw class conflict as the only social reality: warnings from foreign Communists that Europe was different they interpreted as lame excuses for inaction. But as experience was to demonstrate time and again, whatever their grievances, European workers and peasants were neither anarchists nor strangers to the sentiment of patriotism, attitudes that had greatly facilitated the task of revolutionaries in Russia. Even in relatively backward Italy, with its strong base of radical socialism, revolutionary ardor was missing. In August and September 1920, when Italy was seething with agrarian riots and factory seizures, the trade union leaders nearly to a man opposed revolution and failed to stir when the government forcibly restored order. Here, as in the rest of Europe, the decisive factor proved to be not the “objective” economic and social conditions, which were quite revolutionary in Italy, but that imponderable factor, political culture.94

An inquiry into the antirevolutionary spirit of Western labor must also take into account that workers in the advanced industrial countries enjoyed welfare benefits that gave them a stake in the status quo. In Germany, since the advent of Bismarck’s “state socialism,” they had been assured of compensation in case of sickness or accident, as well as support in old age and disability. In England they had had unemployment insurance since 1905 and old age pensions since 1908. The National Insurance Act of 1911 provided compulsory benefits for poorer workers from contributions by the government, the employers, and the workers, which guaranteed basic health and unemployment aid. Workers who had such protection from the state were not likely to want its overthrow, risking the benefits they had won from “capitalism” for the possibly more generous but much less certain rewards of socialism. The Bolsheviks did not account for this reality because prerevolutionary Russia had had nothing comparable.

A survey of Communist movements in Europe indicates that within a year of its Second Congress, the Comintern had achieved considerable success. By the end of 1920 it had won over, at least formally, most of what had been the Italian Socialist Party, and more than half of the French. It had a sizable following in Germany, as well as in Czechoslovakia, Romania, Bulgaria, and Poland.95 All these parties had accepted the 21 Points, and by so doing placed themselves at the disposal of Moscow. Had Lenin showed greater respect for European traditions of political compromise and nationalism, the influence of the Communist International might have steadily grown. But he was accustomed to Russian conditions, where firm authority was all and patriotism counted for little. His tactless interference in the internal affairs of European Communist parties and his resort to slander and intrigue against anyone who dared to disagree with him soon alienated the most idealistic and committed followers. Their place was taken by opportunists and careerists—for who else would be willing to work under the rules set by Moscow, which treated independent thought and obeying one’s conscience as treason?

Another factor that contributed to the degradation of Comintern personnel was money. Balabanoff was amazed by Lenin’s willingness to spend whatever was necessary to buy followers and influence opinion. When she told him of her uneasiness, Lenin replied: “I beg you, don’t economize. Spend millions, many, many millions.”96 The moneys realized from the sale abroad of Soviet gold and tsarist jewels reached Western Communist parties and fellow-travelers in devious ways, mostly by special couriers and Soviet diplomatic agents.* As will be seen (this page), in 1920 tens of thousands of pounds sterling were brought to England by two Soviet diplomats, Krasin and Kamenev, to finance a friendly left-wing newspaper and promote industrial strife there. But Moscow also utilized other channels, most of which remain concealed to this day. It is known, however, that in England one of the transfer agents was Theodore Rothstein, a Soviet citizen (later Soviet Minister to Iran) and the chief Comintern agent there, who transmitted Moscow’s money to British Communists.97 After 1921, when Moscow established commercial relations with Western countries, Soviet trade agencies served as additional conduits for funds. Little is known of these transactions, carried out in great secrecy, but it appears that nearly every Communist party and many pro-Communist groups benefited from Moscow’s largesse: according to a French Communist, his was the only party that did not live off “Moscow’s manna.”98 This claim is borne out by an internal financial statement of the Comintern which indicates that subsidies in currency (Russian and foreign) as well as “valuables” (mainly gold and platinum) were in 1919 and 1920 generously paid to Communist parties in Czechoslovakia, Hungary, the United States, Germany, Sweden, England, and Finland.† Subsidies ensured Moscow’s control over European Communist parties; at the same time they degraded the quality of these parties’ leadership.

One reason for the ruthlessness with which Moscow treated its foreign adherents was the belief that revolution in Europe was imminent and that only the methods employed in Russia promised success. “The Bolsheviks simply reasoned that parties not wholly Communist would be prevented by vacillators from utilizing the revolutionary opportunities to seize power as the Bolsheviks had done in 1917, and to establish a Soviet dictatorship of the proletariat.”99 This is a generous explanation. It has been suggested by no less an authority than Angelica Balabanoff that behind it lay another motive, namely the desire to maintain power. Pondering the behavior of her Russian colleagues, she reluctantly concluded that it had less to do with the good of the cause than with the desire to dominate European socialism. Zinoviev’s animus toward Serrati and insistence on his expulsion led her to believe “that the objective was not the elimination of right-wing elements but the removal of the most influential and important members, in order to make it easier to manipulate the others. To make such manipulation possible, it is necessary always to have two groups that can be played off against each other.”100 The vehemence with which Lenin insisted on dividing Western socialist movements and ejecting from the Comintern members with the greatest mass following in favor of docile flunkies, she declared, was primarily motivated by the desire to establish Moscow’s—that is, Lenin’s—hegemony over foreign socialist parties. The suspicion is bolstered by a 1924 letter of Stalin’s to a German Communist editor that “the victory of the German proletariat will indubitably shift the center of the world revolution from Moscow to Berlin.”101

Since all attempts by Communists to utilize revolutionary opportunities in Europe ended in disaster, the net legacy of Lenin’s strategy was to splinter and thereby weaken the socialist movements. This made it possible in several countries, notably Italy and Germany, for radical nationalists to crush the socialists and establish totalitarian dictatorships that outlawed Communist parties and turned against the Soviet Union. In the end, therefore, Lenin’s strategy promoted the very thing he most wanted to avoid.

Although it concentrated on the industrial countries, the Comintern did not ignore the colonies. Lenin had been persuaded long before the Revolution by J. A. Hobson’s Imperialism (1902) that colonial possessions were of critical importance for advanced or “finance” capitalism. Capitalism had managed to survive because the colonies provided it with cheap raw materials and additional markets for manufactured goods. In Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism (1916), Lenin argued that the capitalist economy could not endure without colonies, profits from which capitalism used to “buy off” workers. “National liberation” movements in these areas would strike at the very lifeline of capitalism.