How do you solve the following problem: if the peasantry is not with us, if the working class falls under the influence of various anarchist elements and also tends to abandon us—on what can the Communist Party now base itself?

Iurii Milonov at the Tenth Congress of

the Communist Party (March 1921)1

Nothing has been left that could obstruct the central government, but, by the same token, nothing could shore it up.

Alexis de Tocqueville2

The political crisis that shook the Communist Party in 1921–23 was due to the fact that the suppression of rival parties did not eliminate dissent, but merely shifted it from the public arena into the inner ranks of the party. This development violated the cardinal tenet of Bolshevism, disciplined unity. The resolutions of the Eleventh Party Congress obliquely acknowledged what was occurring:

In order to consolidate the victory of the proletariat and to maintain its dictatorship under conditions of an exceedingly stressful civil war, the proletarian vanguard had to deprive all political groupings hostile to Soviet authority of the freedom to organize. The Russian Communist Party was left the country’s only legal political party. This circumstance, of course, gave the working class and its party many advantages. But, on the other hand, it also produced phenomena that have extremely complicated the party’s work. Inevitably, into the ranks of the only legal political party streamed, seeking to exert their influence, groups and strata that under different conditions would be found not in the ranks of the Communist Party but those of Social-Democracy or another variant of petty-bourgeois socialism.3

As Trotsky put it: “Our party is now the only one in the country; all discontent goes only through our party.”4 The leadership thus confronted a painful choice: whether to sacrifice unity and all the advantages that flowed from it by tolerating dissent within party ranks, or to outlaw dissent and maintain unity even at the risk of both the ossification of the party’s leading apparatus and its estrangement from the rank and file. Lenin unhesitatingly opted for the second alternative: by this decision, he laid the groundwork for Stalin’s personal dictatorship.

The Bolshevik leaders, and no one more than Lenin, fretted about the progressive bureaucratization of their regime. They had the feeling—and statistical evidence to support it—that both the party and the state were being weighed down by a parasitic class of functionaries who used their offices to promote personal interests. To make matters worse, the more the bureaucracy expanded, the more of the budget it absorbed, the less got done. This held true even of the Cheka: in September 1922 Dzerzhinskii demanded a thorough accounting of what Cheka personnel were doing, adding that he believed such a survey would yield “deadly” (ubiistvennye) results.5 For Lenin in the last period of his life the bureaucracy became an obsessive concern.

That they should have been surprised by this phenomenon only provides further evidence that under the hard-bitten realism of the Bolsheviks lurked a remarkable naïveté.* It should have been apparent to them that the nationalization of the country’s entire organized life, economic activity included, was bound to expand the number of white-collar workers. It apparently never occurred to them that “power” (vlast’), of which they never had enough, meant not only opportunity but also responsibility; that the fulfillment of that responsibility was a full-time occupation calling for correspondingly large cadres of professionals; and that these professionals were unlikely to be concerned exclusively or even primarily with public welfare but would also attend to their own needs. The bureaucratization of life that accompanied Communist rule opened unprecedented opportunities for clerical careers to lower-middle-class elements previously barred from them: they were its principal beneficiaries.6 And even workers, once they left the factory floor for the office, ceased to be workers, merging with the bureaucratic caste, although in party censuses they often continued to be listed as workers: in a private letter to Lenin, Kalinin urged that only persons engaged in manual labor be listed as workers, whereas “foremen, markers, watchmen” should be classified as office personnel (sluzhashchie).7 This is how the Menshevik émigré organ analyzed the phenomenon on the eve of NEP:

The Bolshevik dictatorship … has ejected from all spheres of governmental and public administration not only the tsarist bureaucracy, but also the intelligentsia from bourgeois circles, with their diplomas, and in this manner opened the “path upward” to that countless offspring of the petty bourgeoisie, the peasantry, the working class, the armed forces, and so forth, who previously, by virtue of the privileged status of wealth and education, had been attached to the lower classes and who now make up the huge “soviet bureaucracy”—this new urban stratum, in its essence and ambitions a petty bourgeoisie, all of whose interests bind it to the Revolution, because it alone enabled them to climb to where they are, freed of hard productive labor and involved in the mechanism of state administration, rising above the nation’s masses.8

The Bolsheviks failed to anticipate this development because their philosophy of history taught them to regard politics exclusively as a by-product of class conflicts, and governments as nothing but instruments of the ruling class: a view that precluded the state and its corps of civil servants having interests distinct from those of the class they were said to serve. The same philosophy prevented them from understanding the nature of the problem once they had become aware of it. Like any tsarist conservative, Lenin could think of no better device to curb the abuses of the bureaucracy than piling one “control” commission on top of another, sending out inspectors, and insisting there was no abuse that “good men” could not correct. The systemic sources of the problem eluded him to the end.

Bureaucratization occurred in the apparatus of the party as well as of the state.

Although structured in a highly centralized fashion, the Bolshevik party traditionally cultivated within its ranks a certain degree of informal democracy.9 Under the principle of “democratic centralism,” decisions taken by the directing departments had to be carried out by the lower organs with no questions asked. But the decisions were reached by majority vote—first of the Central Committee, and then of the Politburo—after thorough debate in which everyone had a chance to have his say. Provincial party cells were routinely consulted. Even as dictator of the country, within the party Lenin was only primus inter pares: neither the Politburo nor the Central Committee had a formal chairman. Delegates to the party’s congresses, its highest organs, were elected by local organizations. Local party officials were chosen by fellow members. In fact, Lenin almost always prevailed by the force of his personality and stature as the party’s founder: but victory was not assured and on occasion eluded even him.

As the party assumed ever greater responsibilities for managing the country, its membership expanded and so did its administrative apparatus. Until March 1919, a single person, Iakov Sverdlov, carried in his head all the details of party organization and personnel. He ran the party from day to day, freeing Lenin and his associates to make the political and military decisions.10 Such a system could not last for long in any event, given that by March 1919 the party had 314,000 members. Sverdlov’s sudden death at this time made it imperative to place the party’s management on a more formal basis. To this end the Eighth Party Congress in March 1919 created two new organs of the Central Committee: the Politburo, initially of five members (Lenin, Trotsky, Stalin, Kamenev, Nikolai Krestinskii), to decide swiftly on urgent issues, without resort to the entire Central Committee; and the Orgburo, also of five members, to attend to organizational matters, which in practice meant personnel appointments. The third institution, the Secretariat, established in March 1917, until Stalin’s appointment as its chairman in April 1922, seems to have occupied itself mainly with shuffling papers. Its head, the Secretary, was required to be a member of the Orgburo. Judging by the agenda of the Orgburo and the Secretariat after Stalin had taken over, there was no strict division of responsibilities between them, both dealing with personnel matters, although the Orgburo seems to have been more directly responsible for monitoring the performance of the cadres.11 The creation of these organs began the process of concentrating authority in party affairs at the top, in Moscow.

By the time the Civil War ended, the Communist Party had a sizeable staff occupied exclusively with paperwork. A census conducted toward the end of 1920 revealed interesting facts about its composition. Only 21 percent of the members engaged in physical labor in industry or agriculture; the remaining 79 percent held various white-collar positions.* The members’ educational level was exceedingly low and not commensurate with their responsibilities and authority: in 1922, only 0.6 percent (2,316) had completed higher education, and 6.4 percent (24,318) had secondary school diplomas. On the basis of this evidence, one Russian historian has concluded that at that time 92.7 percent of party members were functionally semiliterate (18,000, or 4.7 percent, were completely illiterate).12 From the body of white-collar personnel emerged an elite of functionaries employed in Moscow by the central organs of the Communist Party. In the summer of 1922, this group numbered over 15,000 persons.13

The bureaucratization of party life had inevitable consequences.… The Party official engaged exclusively on Party business was at an obvious advantage compared with the rank-and-file Party member who had a full-time job in a factory or in a government office. The sheer force of professional preoccupation with Party management rendered the officialdom the center of initiative, direction, and control. At every level of the Party hierarchy, a transfer of authority became visible, first from the congresses or conferences to the committees which they nominally elected, and then from the committees to the Party secretaries who ostensibly executed their will.14

The Central Committee apparatus, gradually, naturally, and almost imperceptibly, supplanted the local organs of the Party not only in making most of the decisions but also in selecting executive personnel at all levels. The process of centralization did not stop there, progressing with an inexorable logic: first the Communist Party took over all organized political life; then the Central Committee assumed direction of the Party, stifling initiative and silencing criticism; next, the Politburo began to make all the decisions for the Central Committee; then three men—Stalin, Kamenev, and Zinoviev—came to control the Politburo; until finally one man alone, Stalin, decided for the Politburo. Once the process culminated in a one-man dictatorship, it had nowhere further to go, with the result that Stalin’s death led to the gradual disintegration of the Party and its authority over the country.

Already in 1920 it was common for the Orgburo to designate provincial Party officials without consulting the organizations they were selected to manage15: a practice which came to be known as naznachenstvo, or “appointmentitis.” In a country accustomed for centuries to bureaucratic rule and the flow of directives from above, such procedures seemed normal, and opposition to it was confined to a small and ineffective minority.

Although there undoubtedly were Communists who joined the Party for idealistic reasons, the majority did so for the advantages membership bestowed. Members enjoyed privileges that in the nineteenth century had been associated with gentry (dvorianstvo) status, namely, assured access to executive (“responsible”) positions in government. Trotsky labeled them “radishes” (red outside, white inside). Those sufficiently high in the Communist hierarchy received additional food rations and access to exclusive shops, as well as cash allowances. They had virtual immunity from arrest and prosecution, which in the lawless Soviet society was no mean privilege. Emulating tsarist practices, the Soviet government established as early as 1918 the principle that its officials could not be brought to justice for actions committed in the performance of duties.16 Whereas under tsarism, an official could be tried only with the concurrence of his immediate superiors, a Communist functionary could be arrested “only with the knowledge and approval of the Party organization corresponding to the rank he held in the Party.”17 Lenin strenuously objected to this practice, demanding that Communists be punished for wrongdoing more severely than others, but he was powerless to change custom.18 From the beginning of its reign, the Communist Party’s status as an entity above the law transferred also to its membership.

Such power, combined with legal immunity, inevitably led to abuses. Beginning with the Eighth Party Congress (1919), complaints were heard of the corruptibility of party personnel and their estrangement from the masses.19 The pages of the Communist press were filled with accounts of violations of the most elementary norms of decency by party officials: judging by some, Communist bosses behaved like eighteenth-century owners of serfs. Thus, in January 1919 the Astrakhan organ of the Communist Party reported on the visit of Kliment Voroshilov, Stalin’s comrade-in-arms and commander of the Tenth Army at Tsaritsyn. Voroshilov made his appearance in a luxurious shestërka, a coach pulled by six horses, followed by ten carriages with attendants, and some fifty carts piled high with trunks, casks, and other wares. On such forays, the local inhabitants were required to render the visiting dignitaries all manner of personal services and were threatened with revolvers if they refused.20

To end such scandalous behavior, the Party carried out a purge in late 1921 and early 1922. Although ostensibly directed at careerists who had enrolled under the relaxed admission procedures in force during the Civil War, its true targets were persons who had transferred from the other socialist parties, notably Mensheviks, whom Lenin blamed for injecting democratic and other heretical ideas into Communist ranks.21 Many were expelled; and with voluntary resignations, especially by disgruntled workers, the membership declined from 659,000 to 500,000, and then sank still lower, below 400,000.* The practice was instituted at this time of appointing “candidate members,” who had to undergo a period of apprenticeship before qualifying for admission. In subsequent purges (1922–23) more were expelled or resigned, until nearly half of the party turned over.22 These procedures may have rid the party of Mensheviks and other “petty-bourgeois socialists” but not of corrupt Communists. Abuses continued because they inhered in the privileged status of the Communist Party and its complete freedom from accountability. If the citizen had no means of redress against those administering him either as voter or as the owner of property, and if, moreover, party members were exempt from legal responsibility, then it was inevitable that the administrative corps would turn into a self-contained, self-perpetuating, and self-gratifying body. The Control Commission established in 1920 to oversee the ethics of the Party reported that party officials felt they were accountable for the performance of their duties only to those who had appointed them, not to the “party masses,”23 let alone to the population at large. It was a carryover of attitudes prevalent among officials under tsarism.24

To make matters worse still, the Party itself began to corrupt the bureaucracy. In July 1922, the Orgburo passed an innocuous-sounding ruling, “On the improvement of the living conditions of active party workers,” originally published in a truncated version.25 It established a salary scale for party functionaries: they were to receive several hundred (new) rubles, with additional allowances for families and overtime, which in their totality could double their basic pay—this at a time when the average industrial worker earned 10 rubles. High party bureaucrats were further entitled, free of charge, to extra food rations, as well as housing, clothing, and medical care, and, in some instances, chauffeured cars. In the summer of 1922 “responsible workers” employed in the central organs of the Party were issued supplementary food rations entitling them to 26 pounds of meat and 2.6 pounds of butter a month. They traveled in special train coaches, upholstered and lit by candles, while ordinary mortals, fortunate enough to obtain tickets, had to squeeze into crowded third-class compartments or freight cars.26 The very highest officials had the right to vacations and rest cures of one to three months in foreign sanitoria, for which the Party paid in gold rubles. In November 1921, no fewer than six top-level Communists were receiving medical care in Germany: one of them (Lev Karakhan) went there for hemorrhoid surgery.27 Allocations of such benefits were made by Stalin’s Secretariat, the staff of which, on his assumption of office, numbered 600.28 In the summer of 1922, the number of persons entitled to special benefits exceeded 17,000; in September of that year, the Orgburo raised it to 60,000.

The Party’s leaders qualified for dachas. The first to acquire a country house was Lenin, who in October 1918 took over an estate at Gorki, 35 kilometers southwest of Moscow, the property of a tsarist general. Others followed suit: Trotsky took over one of the most luxurious landed estates in Russia, Arkhangelskoe, the property of the princes Iusupov, while Stalin made himself at home in the country house of an oil magnate at Zubalovo.29 At Gorki, Lenin had at his disposal a fleet of six limousines operated by the GPU.30 Although he rarely asked favors for himself, he was not averse to requesting them for members of his family and friends, as, for instance, directing that the private coach in which his sister and the Bukharins were traveling to the Crimea, almost certainly on vacation, be attached to military trains to speed up their journey.31 When attending the theater or opera, the new leaders occupied as a matter of course the imperial loges.

Imperceptibly, the new rulers slipped into the habits of the old. Adolf Ioffe complained to Trotsky in 1920 of the spreading rot:

From top to bottom and from bottom to top, it is everywhere the same. On the lowest level, it is a pair of shoes and a soldier’s shirt [gimnasterka]; higher up, an automobile, a railroad car, the Sovnarkom dining room, quarters in the Kremlin or the “National” hotel; and on the highest rungs, where all this is available, it is prestige, prominent status, and fame.32

According to Ioffe it was becoming psychologically acceptable to believe that “the leaders can do anything.” None of these patrician habits of public servants had anything to do with Marxism, but they did have a great deal to do with the political traditions of Russia.

69. A new elite in the making: a party functionary (extreme right) reads while workers labor.

The key territorial administrators under the new regime were the chairmen of the provincial (guberniia) committees of the Party, popularly known as gubkomy. Since Peter the Great, the guberniia had been the basic administrative unit of Russia, and its chief, the governor, enjoying broad executive and police powers, represented imperial authority. The Bolshevik regime followed this tradition: secretaries of the gubkomy became, in effect, successors to imperial governors. The authority to designate them, therefore, was a source of considerable patronage. Before the Revolution, governors had been appointed by the tsar on the recommendation of the Minister of the Interior; now they were appointed by Lenin at the recommendation of the Orgburo and the Secretariat. A special department of the latter, called Uchraspred (Uchetno-Raspredetil’nyi Otdel), established in 1920, selected and transferred party personnel. In December 1921, it was ruled that to qualify as gubkom secretary one had to have joined the Party before October 1917; secretaries of district (uezd) party committees (ukomy) had to have belonged for a minimum of three years. All such appointments were to be approved by a higher party authority.33 These provisions may have helped safeguard discipline and orthodoxy, but at the price of depriving party cells of the right to choose their own officers. Although little noticed at the time, they vastly enhanced the powers of the central apparatus: “The right of confirmation by the Orgburo or Secretariat … became in practice tantamount to a right of ‘recommendation’ or ‘nomination.’ ”34 All this had occurred before Stalin assumed the post of General Secretary in April 1922.

As a result of these practices, appointments to key Party posts in the provinces increasingly were made not by the members but by the “Center.” During 1922, thirty-seven gubkom secretaries were removed or transferred by Moscow, and forty-two appointed on its “recommendation.”* Now, as under tsarism, loyalty was the supreme qualification for appointment: in a circular sent out by the Central Committee, “the loyalty of a given comrade to the Party” was listed as the very first criterion for office.35 In the course of 1922, the Secretariat and Orgburo made over 10,000 assignments.36 Since the Politburo was overburdened with work, many of these assignments were made at the discretion of the General Secretary and the Orgburo. Frequently, inspection teams were sent to the provinces to report on the performance of gubkomy—an echo of the “revisions” of Imperial Russia. At the Tenth Party Conference held in May 1921, it was resolved that gubkom secretaries were to come to Moscow every three months to report to the Secretariat.37 Viacheslav Molotov, who worked for the Secretariat, justified these practices with the argument that left to themselves the gubkomy attended mostly to their own, local affairs and ignored national party concerns.38 In effect, the gubkomy turned into “conveyor belts for Moscow directives.”39

The Secretariat acquired the additional authority to select delegates to party congresses, nominally the party’s highest authority. By 1923, most delegates were appointed on the recommendation of gubkom secretaries, who themselves were in good measure appointees of the Secretariat.40 This authority enabled the Secretariat to muzzle opposition from the rank and file. Thus at the Tenth Party Congress (1921), which witnessed acrimonious debates pitting the so-called “Workers’ Opposition” and “Democratic Centralists” against the Central Committee, 85 percent of the delegates fell in line with the Central Committee’s resolutions condemning the dissenters: a vote which, judging by the available evidence, hardly reflected the sentiments of the membership at large.41 Two years later, at the Twelfth Congress, the opposition was reduced to an impotent fringe. At the next Congress, there no longer was an opposition.

Thus an aristocracy emerged in the Communist service class. The practices adopted five years after the power seizure were a far cry from the early days of the regime, when the Party insisted on its members’ receiving lower salaries than the average worker and confining their living quarters to one room per person.42 They also meant the abandonment of regulations that denied Communists employed in factories special privileges, while imposing on them heavier obligations.43

So much for the Party bureaucracy.

The state bureaucracy expanded at an even more spectacular rate. The structure of nationwide soviets rapidly lost the little influence they had had on Bolshevik policies, and by 1919–20 turned into rubber stamps for party decisions transmitted through the Council of People’s Commissars and its branches. Their “elections” turned into ceremonies to approve nominees picked by the Party: fewer than one in four eligible citizens bothered to vote.44 The soviets were supplanted by bureaucratic state institutions, behind which stood the all-powerful Party. In 1920, the last year that the soviets were allowed to hold open discussions, it was common to hear complaints about the spread of the bureaucracy.45 In February 1920, the office of Worker-Peasant Inspection (Rabkrin) was created, with Stalin as chairman, to oversee abuses in state institutions; but as Lenin conceded two years later, it did not meet his expectations.46

The expansion of the governmental bureaucracy is explainable first and foremost by the fact of the government taking over the management of institutions that before October 1917 had been in private hands. By eliminating private enterprise in banking and industry, by abolishing zemstvos and city councils, by dissolving all private associations, the government assumed liability for their functions, which, in turn, demanded a proportionate expansion of officialdom. One example will suffice. Before the Revolution, the nation’s schools were partly supervised by the Ministry of Public Instruction, partly by the Orthodox Church, and partly by private bodies. When, in 1918, the government nationalized all schools under the Commissariat of Enlightenment, it had to create a staff to replace the clerical and private personnel previously in charge of nongovernmental schools. In time, the Commissariat of Enlightenment was also given responsibility for directing the country’s cultural life, previously almost entirely in private hands, and for enforcing censorship. As a consequence, as early as May 1919 it had on its payroll 3,000 employees—ten times the number employed by the corresponding tsarist ministry.47

But enhanced administrative responsibilities were not the sole reason for the increase in the Soviet bureaucracy. An employee even on the lowest rungs of the civil service ladder acquired precious advantages of survival under the harsh conditions of Soviet life: access to goods not available to ordinary citizens, as well as opportunities to obtain bribes and tips.

The result was massive featherbedding. White-collar jobs multiplied in the various bureaus directing the Soviet economy at the very time that production was declining. While the number of workers employed in Russian industry dropped from 856,000 in 1913 to 807,000 in 1918, the number of white-collar employees rose from 58,000 to 78,000. Thus, already in the first year of the Communist regime, the ratio of white- to blue-collar industrial employees grew by one-third, compared to 1913.48 In the next three years, this ratio rose even more dramatically: whereas in 1913, for every 100 factory workers there were 6.2 white-collar employees, in the summer of 1921 their proportion rose to 15.0 per hundred.49 In transport, with railroad traffic declining by 80 percent and the number of workers remaining stationary, bureaucratic personnel increased by 75 percent. Whereas in 1913 there were 12.8 employees, both blue- and white-collar, per one kilometer (five-eighths of a mile) of railroad track, in 1921 20.7 were required to perform the same tasks.50 An inquiry into one rural district of Kursk province, carried out in 1922–23, showed that the local agriculture department, which under tsarism had 16 employees, now had 79—and this while food output had dropped. The police chancery in the same district had doubled its personnel compared to prerevolutionary days.51 Most monstrous was the expansion of the bureaucracy charged with managing the economy: in the spring of 1921, the Supreme Council of the National Economy (VSNKh) employed 224,305 functionaries, of whom 24,728 worked in Moscow, 93,593 in its provincial agencies, and 105,984 in the districts (uezdy)—this at a time when the industrial productivity of which it was in charge had dropped to below one-fifth of what it had been in 1913.52 In 1920, to Lenin’s astonishment and anger, Moscow housed 231,000 full-time functionaries, and Petrograd, 185,000.53 Overall, between 1917 and the middle of 1921, the number of government employees increased nearly fivefold, from 576,000 to 2.4 million. By then, the country had over twice as many bureaucrats as workers.54

Given the immense need for officials and the low educational level of its own cadres, the new regime had no choice but to hire large numbers of ex-tsarist officials, especially personnel qualified to run ministerial bureaus. The following table indicates the percentages of such officials in the commissariats as of 1918:55

| Commissariat of the Interior | 48.3% |

| Supreme Council of National Economy | 50.3% |

| Commissariat of War | 55.2% |

| Commissariat of State Control | 80.9% |

| Commissariat of Transport | 88.1% |

| Commissariat of Finance | 97.5% |

“Indications are that over half the officials in the central offices of the commisariats, and perhaps ninety percent of upper echelon officials, had worked in some kind of administrative position before October 1917.”56 Only the Cheka, with 16.1 percent ex-tsarist officials, and the Commissariat of Foreign Affairs, with 22.9 percent (both figures are for 1918), were staffed primarily with new personnel.57 On the basis of this evidence, one Western scholar has reached the startling conclusion that the changes in government personnel made by the Bolsheviks in the first five years “could perhaps be compared with those occurring in Washington in the heyday of the ‘spoils system.’ ”58

The new bureaucracy modeled itself on the tsarist. As before 1917, officials served the state, not the nation, which they viewed as a hostile force. The anarchist Alexander Berkman, who visited Russia in 1920, thus depicted the typical government office under the new regime:

The Soviet institutions [in the Ukraine] present the familiar picture of the Moscow pattern: gatherings of worn, tired people, looking hungry and apathetic. Typical and sad. The corridors and offices are crowded with applicants seeking permission to do or to be exempt from doing this or that. The labyrinth of new decrees is so intricate, the officials prefer the easier way of solving perplexing problems by “revolutionary method,” on their “conscience,” generally to the dissatisfaction of the petitioners.

Long lines are everywhere, and much writing and handling of “papers,” and documents by baryshni (young ladies) in high heeled shoes, that swarm in every office. They puff at cigarettes and animatedly discuss the advantages of certain bureaus as measured by the quantity of the paëk [ration] issued, the symbol of Soviet existence. Workers and peasants, their heads bared, approach the long tables. Respectfully, even servilely, they seek information, plead for an “order” for clothing, or a “ticket” for boots. “I don’t know,” “In the next office,” “Come tomorrow,” is the usual reply. There are protests and lamentations, and begging for attention and advice.59

As in the days of tsarism, Soviet officialdom was elaborately stratified. In March 1919, the authorities divided the civil service into 27 categories, each minutely defined. Salary differentials were relatively modest: thus employees in the lowest rank (razriad), made up of junior doormen, charwomen, and the like, received 600 (old) rubles a month, those in the 27th rank (heads of commissariat departments, and such like) were paid 2,200 rubles.60 But wages counted for little, because of hyperinflation: the meaningful salary took the form of perquisites, of which food rations were the most important. Thus Lenin in 1920 obviously did not live on his monthly salary of 6,500 rubles, which would have bought him thirty cucumbers on the black market, the only place where they were available to ordinary citizens.61 In addition to the paëk, even the lowest officials had ways of supplementing their wages by means of bribery, which was rampant, notwithstanding severe laws against it.62

Lenin liked to ascribe the unsatisfactory state of the Soviet apparatus to the large number of ex-tsarist bureaucrats in its employ: “With the exception of the Commissariat of Foreign Affairs,” he wrote, “our state apparatus, most of all, represents a survival of the old apparatus, least of all subjected to the smallest changes. It is only slightly adorned at the top; in other respects, it is the most typically old of our old state apparatus.”63 But as his disjointed and confused remarks on the subject indicate, he had not the slightest idea what had gone wrong and why. The size of the bureaucracy was determined by the scope of his government’s ambitions, while its corruptibility was assured by freedom from public controls.

In the summer of 1920 the Communist Party was shaken by a heresy the party establishment designated the “Workers’ Opposition.” It reflected the dissatisfaction of Bolshevik industrial workers with the manner in which intellectuals had taken control of the country, and, more specifically, with the bureaucratization of industry and the concurrent decline in the authority and autonomy of trade unions. Although its spokesmen were veteran Communists, the movement also expressed the sentiments of that majority of workers who either belonged to no party or inclined toward Menshevism. Its main bases of support were Samara, where the Workers’ Opposition took over the gubkom, the Donbass region, and the Urals. Its adherents were very influential in the metallurgical, mining, and textile industries.64 Alexander Shliapnikov, its head, ran the Metal Workers’ Union, the strongest union in the country and the one traditionally most friendly to the Bolsheviks. The highest Bolshevik functionary of worker background, during World War I Shliapnikov had directed the party’s underground in Petrograd, and in October 1917 took over the Commissariat of Labor. Alexandra Kollontai, his mistress, was the movement’s most articulate theorist. Alongside the Workers’ Opposition emerged a second heresy known as “Democratic Centralism.” Composed of well-known Communist intellectuals, it objected to the bureaucratization of the party and the employment in industry of “bourgeois specialists.” Its adherents wanted greater power for the soviets, while opposing trade union demands for a dominant role in economic management. One of their leaders, T. V. Sapronov, an old Bolshevik, also of worker origin, had the temerity at a party congress to call Lenin an “ignoramus” (nevezhda) and an “oligarch.”*

The Workers’ Oppositionists were stalwart Bolsheviks. They accepted the dictatorship of the Party and its “leading role” in the trade unions; they approved of the abolition of “bourgeois” freedoms and the suppression of political parties. They found nothing wrong with the party’s treatment of the peasantry. When Kronshtadt rebelled in 1921 they were among the first to volunteer for the Red Army units formed to suppress the mutiny. In Shliapnikov’s words, their differences with Lenin were not over objectives, but over means. They found it unacceptable that the intelligentsia, formed into a new bureaucracy, was displacing labor as the country’s ruling class. For indeed, the country’s “worker” government had not a single worker in a position of authority: most of its leading officials had not only never worked in a factory or on a farm, but had never even held a steady job.65

70. Shliapnikov.

Lenin took this challenge extremely seriously: he was not inclined to ignore “worker spontaneity,” which he had fought ever since founding the Bolshevik party. Denouncing the Workers’ Opposition as a species of Menshevism and syndicalism, he counterattacked and crushed it in no time. But in so doing he had recourse to procedures that destroyed, once and for all, what was left of democracy in Communist ranks. To maintain the fiction that the Bolshevik dictatorship was a government of workers while ignoring the workers’ wishes, he ensured the government’s isolation even from its own supporters.

The Workers’ Opposition emerged into the open at the Ninth Party Congress (March 1920) in connection with Moscow’s decision to introduce into industry the principle of one-man management. Until then, Soviet Russia’s nationalized enterprises had been administered by boards, on which sat, alongside technical specialists and party officials, representatives of trade unions and factory committees. This arrangement proved inefficient and was blamed for the collapse of industrial production. The party leadership had determined already in 1918 to shift to personal management, but the decision was difficult to implement because of labor resistance. Now that the Civil War was over, the Ninth Party Congress resolved to put into effect, “from top to bottom, the frequently stated principle of express responsibility of a given person for the given work. Collegiality, to the extent that it has a place in the process of deliberation or decisionmaking, must unconditionally yield to individualism in the process of execution.”66 In anticipation of this resolution, the Central Council of Soviet Trade Unions had voted in January 1920 against one-man management. Lenin disregarded its wishes. He similarly ignored the preference of the workers of Donbass, whose delegates voted 21 to 3 in favor of retaining the collegial system of industrial management.67

Under the new arrangement, introduced nationwide in 1920 and 1921, trade unions and factory committees no longer participated in decisionmaking, but only in the implementation of decisions made by professional managers. Lenin had the Ninth Party Congress pass a resolution forbidding trade unions to interfere with management. He justified such procedures with the argument that under Communism, which had eliminated the exploiting classes, trade unions no longer had to defend the interests of the workers since this was done for them by the government. Their proper function was to act as government agents in improving production and maintaining labor discipline:

Under the dictatorship of the proletariat, trade unions transform themselves from organs of struggle of the vendors of labor against the ruling class of capitalists, into instruments of the ruling working class. The tasks of trade unions lie, mainly, in the areas of organization and education. These tasks the trade unions must fulfill not as a self-sufficient, organizationally isolated force, but as one of the basic instruments of the Soviet state, led by the Communist Party.68

In other words, Soviet trade unions henceforth were to represent not the workers but the government. Trotsky fully subscribed to this view, arguing that in a “workers’ state” the trade unions had to rid themselves of the habit of viewing the employer as an adversary, and turn into factors of productivity under the party’s guidance.69 This view of their function meant in practice that trade union officials would not be elected by their members but appointed by the party. As had so often happened in the course of Russian history, an institution created by a social group to defend its interests was taken over by the state for its own purposes.

Russia’s trade union leaders took seriously the claim that their country was a “dictatorship of the proletariat”: strangers to the subtleties of dialectic, they failed to understand how the party leadership, composed of intellectuals, could know better what was good for labor than labor itself. They objected to the dismissal of worker representatives from industrial management and the return to positions of authority, in the guise of “specialists,” of former captains of industry. These people, they complained, treated them exactly as they had done under the old regime. What, then, had changed? and what had the revolution been for? They further objected to the introduction into the Red Army of a command hierarchy and to the restoration in it of ranks. They criticized the bureaucratization of the Party and the accumulation of power in the hands of its Central Committee. They denounced the practice of having provincial party officials appointed by the Center. To bring the Party into direct contact with the laboring masses, they proposed that its directing organs be subjected to frequent personnel turnovers, which would open access to true workers.70

The emergence of the Workers’ Opposition brought into the open a smoldering antagonism that went back to the late nineteenth century, between a minority of politically active workers and the intellectuals who claimed to represent them and speak in their behalf.71 Radical workers, usually more inclined to syndicalism than Marxism, cooperated with the socialist intelligentsia and allowed themselves to be guided by them because they knew they were short of political experience. But they never ceased to be aware of a gulf between themselves and their partners: and once a “workers’ state” had come into being, they saw no reason for submitting to the authority of the “white hands.”*

The concerns expressed by the Workers’ Opposition stood at the center of the deliberations of the Tenth Party Congress in March 1921. Shortly before it convened, Kollontai released for internal party use a brochure in which she assailed the regime’s bureaucratization.72 (Party rules prohibited venting party disputes in public.) The Workers’ Opposition, she argued, made up exclusively of laboring men and women, felt that the Party’s leadership had lost touch with labor: the higher up the ladder of authority one ascended, the less support there was for the Workers’ Opposition. This happened because the Soviet apparatus had been taken over by class enemies who despised Communism: the petty bourgeoisie had seized control of the bureaucracy, while the “grand bourgeoisie,” in the guise of “specialists,” had taken over industrial management and the military command.

The Workers’ Opposition submitted to the Tenth Congress two resolutions, one dealing with party organization, the other with the role of trade unions. It was the last time that independent resolutions—that is, resolutions not originating with the Central Committee—would be discussed at a party congress. The first document spoke of a crisis in the party caused by the perpetuation of habits of military command acquired during the Civil War, and the alienation of the leadership from the laboring masses. Party affairs were conducted without either glasnost’ or democracy, in a bureaucratic style, by elements mistrustful of workers, causing them to lose confidence in the party and to leave it in droves. To remedy this situation, the party should carry out a thorough purge to rid itself of opportunistic elements and increase worker involvement. Every Communist should be required to spend at least three months a year doing physical labor. All functionaries should be elected by and accountable to their members; appointments from the Center should be made only in exceptional cases. The personnel of the central organs should be regularly turned over: the majority of the posts should be reserved for workers. The focus of party work should shift from the Center to the cells.73

The resolution on trade unions was no less radical.74 It protested the degradation of unions, to the point where their status was reduced to “virtual zero.” The rehabilitation of the country’s economy required the maximum involvement of the masses: “The systems and methods of construction based on a cumbersome bureaucratic machine stifle all creative initiative and independence” of the producers. The party must demonstrate trust in the workers and their organizations. The national economy ought to be reorganized from the bottom up by the producers themselves. In time, as the masses gain experience, management of the economy should be transferred to a new body, an All-Russian Congress of Producers, not appointed by the Communist Party, but elected by the trade unions and “productive” associations. (In the discussion of this resolution, Shliapnikov denied that the term “producers” included peasants.)75 Under this arrangement, the Party would confine itself to politics, leaving the direction of the economy to labor.

These proposals by veteran Communists from labor ranks revealed a remarkable ignorance of Bolshevik theory and practice. Lenin, in his opening address, minced no words in denouncing them as representing a “clear syndicalist deviation.” Such a deviation, he went on, would not be dangerous were it not for the the economic crisis and the prevalence in the country of armed banditry (by which he meant peasant rebellions). The perils of “petty bourgeois spontaneity” exceeded even those posed by the Whites: they required greater party unity than ever.76 As for Kollontai, he dismissed her with what apparently was intended as a humorous aside, a reference to her personal relations with the leader of the Workers’ Opposition (“Thank God, we know well that Comrade Kollontai and Comrade Shliapnikov are ‘bound by class ties [and] class consciousness’ ”).*

Worker defections confronted Lenin and his associates with a problem: how to govern in the name of the “proletariat” when the “proletariat” turned its back on them. One solution was to denigrate Russia’s working class. It was now often heard that the “true” workers had given their lives in the Civil War and that their place had been taken by social dregs. Bukharin claimed that Soviet Russia’s working class had been “peasantified” and that, “objectively speaking,” the Workers’ Opposition was a Peasant Opposition, while a Chekist told the Menshevik Dan that the Petrograd workers were “scum” (svoloch) left over after all the true proletarians had gone to the front.77 Lenin, at the Eleventh Party Congress, denied that Soviet Russia even had a “proletariat” in Marx’s sense, since the ranks of industrial labor had been filled with malingerers and “all kinds of casual elements.”78 Rebutting such charges, Shliapnikov noted that 16 of the 41 delegates to the Tenth Congress supportive of the Workers’ Opposition had joined the Bolshevik party before 1905 and all had done so before 1914.79

Another way of dealing with the challenge was to interpret the “proletariat” as an abstraction: in this view, the party was by definition the “people” and acted on their behalf no matter what the living people thought they wanted.80 This was the approach taken by Trotsky:

One must have the consciousness, so to speak, of the revolutionary historic primacy of the party, which is obligated to assert its dictatorship notwithstanding the transient hesitations of the elemental forces (stikhiia), notwithstanding the transient wavering even among the workers.… Without this consciousness the party may perish to no purpose at one of the turning points, of which there are many.… The party as a whole is held together by the unity of understanding that over and above the formal factor stands the dictatorship of the party, which upholds the basic interests of the working class even when the latter’s mood is wavering.81

In other words, the Party existed in and of itself and by the very fact of its existence reflected the interests of the working class. The living will of living people—stikhiia—was merely a “formal factor.” Trotsky criticized Shliapnikov for making a “fetish of democracy”: “The principle of elections within the labor movement is, as it were, placed above the Party, as if the Party did not have the right to assert its dictatorship even in the event that this dictatorship temporarily clashed with the transient mood within the worker democracy.”82 It was not possible to entrust the management of the economy to workers, if only because there were hardly any Communists among them: in this connection, Trotsky cited Zinoviev to the effect that in Petrograd, the country’s largest industrial center, 99 percent of the workers either had no party preference, or, to the extent that they did, sympathized with the Mensheviks or even the Black Hundreds.83 In other words, one could have either Communism (“the dictatorship of the proletariat”) or worker rule, but not both: democracy spelled the doom of Communism. There is nothing to indicate that Trotsky or any other leading Communist saw the absurdity of this position. Bukharin, for example, explicitly acknowledged that Communism could not be reconciled with democracy. In 1924, at the closed Plenum of the Central Committee, he said:

Our task is to acknowledge two dangers. In the first place, the danger that emanates from the centralization of our apparatus. In the second, the danger of political democracy, which may occur if democracy goes over the edge. The opposition sees only one danger—bureaucracy. Behind the bureaucratic danger it does not see the danger of political democracy.… To maintain the dictatorship of the proletariat, we must support the dictatorship of the party.*

Shliapnikov conceded that “unity” was indeed the supreme objective, but, he argued, the party lost the unity it had enjoyed in the past, before taking power, from lack of communication with its rank and file.84 This rupture accounted for the wave of strikes in Petrograd and the Kronshtadt mutiny. The problem was not the Workers’ Opposition: “The causes of the discontent that we see in Moscow and other worker cities lead us not to the ‘Workers’ Opposition’ but to the Kremlin.” The workers felt completely estranged from the party. Among Petrograd metal workers, a traditional bastion of Bolshevism, fewer than 2 percent were members; in Moscow, the proportion of metallurgists belonging to the party fell to a mere 4 percent.† Shliapnikov rejected the argument of the Central Committee that the economic disasters resulted from “objective” factors, notably the Civil War: “That which we presently observe in our economy is the result not only of objective causes, independent of us. In the breakdown which we see, a share of responsibility falls also on the system we have adopted.”85

The motions of the Workers’ Opposition were not submitted to a vote but the delegates could register their preferences by casting ballots for or against two resolutions introduced by Lenin: “On the unity of the party,” and “On the syndicalist and anarchist deviations in our party,” which repudiated the platform of the Workers’ Opposition and condemned its sponsors. The first collected 413 votes against 25, with 2 abstentions; the second, 375 against 30, with 3 abstentions and one invalid vote.86

The Workers’ Opposition suffered a decisive defeat and was ordered to dissolve. It was doomed from the outset not only because it challenged powerful vested interests of the central apparatus, but because it accepted the undemocratic premises of Communism, including the idea of a one-party state. It championed democratic procedures in a party that was by its ideology and, increasingly, by its structure committed to ignoring the popular will. Once the Opposition conceded that the unity of the party was the supreme good, it could not carry on without opening itself to charges of subversion.

We have spent much time on what turned out to be an episode in the history of the Communist Party because the Workers’ Opposition, for the first and, as it turned out, the last time, confronted the Party with a fundamental choice. The Party, whose base of support among the population at large had dwindled to a wafer-thin layer, now faced rebellion in its own ranks from workers, its putative masters. It could either acknowledge this fact and retire, or else ignore it and stay in power. In the latter event, it would have no choice but to introduce into the party the same dictatorial methods it employed in running the country. Lenin chose the second alternative, and he did so with the hearty support of his associates, including Trotsky and Bukharin, who later, when these methods were turned against them, would pose as tribunes of the people and champions of democracy. In taking this fateful step, he ensured the hegemony of the central apparatus over the rank and file; and since Stalin was about to become the unchallenged master of the central apparatus, he ensured Stalin’s ascendancy.

To make impossible further dissent in the party, Lenin had the Tenth Congress adopt a new and fateful rule that outlawed the formation of “factions”: these were defined as organized groupings with their own platforms. The key, concluding article of the resolution “On the unity of the party,” kept secret at the time, provided severe penalties for violators:

In order to maintain strict discipline within the party and in all soviet activities, [in order] to attain the greatest unity by eliminating all factionalism, the Congress authorizes the Central Committee in instances of violations of discipline, or the revival or tolerance of factionalism, to apply all measures of party accounting up to exclusion from the party.*

Exclusion required a two-thirds vote of the members and candidate members of the Central Committee and the Control Commission.

Although Lenin and the majority that voted for his resolution seem to have been unaware of its potential implications, it was destined to have the gravest consequences: Leonard Schapiro regards it as the decisive event in the history of the Communist Party.87 Simply put, in Trotsky’s words, the ruling transferred “the political regime prevailing in the state to the inner life of the ruling party.”88 Henceforth, the party, too, was to be run as a dictatorship. Dissent would be tolerated only as long as it was individual, that is, unorganized. The resolution deprived party members of the right to challenge the majority controlled by the Central Committee, since individual dissent could always be brushed aside as unrepresentative, while organized dissent was illegal.

The ban on inner-party groupings was self-perpetuating and irreversible: under it no movement for its revision could be set afoot. It established within the party that barrack discipline which may be meat for an army but is poison for a political organization—the discipline which allows a single man to vent a grievance but treats the joint expression of the same grievance by several men as mutiny.89

Nothing was better calculated to ensure the bureaucratic rigidity that ultimately stifled everything that was alive in the Communist movement. For it was mainly to enforce the ban on factions that Lenin created in 1922 the post of General Secretary and agreed to Stalin being the first holder of that office.

The consequences of the ban on factions became visible in the representation of the Eleventh Party Congress the following year. Of the 30 delegates who had the courage at the Tenth Congress to vote against Lenin’s resolution condemning the Workers’ Opposition as an “anarchosyndicalist deviation” (the voting was open), all but six had been purged and replaced with more compliant delegates. Molotov could now boast that all party factions had been eliminated.90 By the time the Twelfth Congress convened in 1923, three of the surviving six were gone as well, Shliapnikov among them.91 Such silent purges ensured the unchallenged domination of the Central Committee, which packed party congresses with delegates supportive of its position and interests: suffice it to say that 55.1 percent of the delegates to the Twelfth Congress (1923) were fully occupied with party work, and an additional 30.0 percent were so part-time.92 Not surprisingly, at the Twelfth Congress and subsequently, all resolutions were adopted unanimously. Like the “Land Assemblies” of Muscovite Russia, these gatherings were (in the words of the historian Vasilii Kliuchevskii) “consultations of the government with its own agents.”

Even in the face of such formidable obstacles, the Workers’ Opposition tried to persevere. Ignoring party resolutions, in May 1921, the Communist Party faction of the Metal Workers’ Union rejected by a vote of 120 to 40 the list of officers submitted to it by the Center. The Central Committee disqualified this vote, and proceeded to take over the direction of this and the other trade unions. Union membership became compulsory, and virtually the entire financing of unions henceforth came from the state.93

The anti-faction resolution made the Workers’ Opposition an illegal body and provided grounds for its prosecution. Lenin harried its leaders with a vengeance. In August 1921, he asked the Central Committee Plenum to have them expelled, but his motion fell one vote short of the required two-thirds majority.* Even so, they were subjected to harassment and removed, under one pretext or another, from party posts.94 Unable to get a hearing, the Workers’ Opposition unwisely took its case to the Executive Committee of the Comintern, without securing prior approval of either the party or the Russian delegation to that body. The Executive, by now a section of the Russian Communist Party, rejected the appeal. In September 1923, following a wave of strikes, many adherents of the Workers’ Opposition were arrested.95 Stalin would make certain all were killed. Kollontai was the one exception: in 1923 she was sent to Norway, then to Mexico, and ultimately to Sweden to serve as ambassador—the first woman in history, it was said, to head a diplomatic mission. It seems to have gratified Stalin’s ribald sense of humor to have the apostle of free love represent him in the country of free love. Shliapnikov he had shot in 1937.

The first symptoms of Lenin’s illness appeared in February 1921, when he began to complain of headaches and insomnia. They were not entirely physical in origin. Lenin had suffered a succession of humiliating defeats, including the military debacle in Poland, which ended the hope of spreading the revolution to Europe, and the economic disasters that necessitated a humiliating capitulation to market forces. The physical symptoms resembled those he had suffered in 1900, at another critical moment in the history of the party, when the Social-Democratic movement seemed about to collapse from internal divisions.* In the course of the summer of 1921 the headaches gradually eased, but he continued to suffer from sleeplessness.† In the fall, the Politburo, concerned that Lenin was overworking, requested that he lighten his schedule. On December 31, still unhappy over his condition, it ordered him to take a six-week vacation: he was not to return to his office without the permission of the Secretariat.96 Strange as such orders may appear, they were routinely issued by the highest party organs to Communist personnel: as E. D. Stasova, Lenin’s principal secretary, told General S. S. Kamenev, Bolsheviks were to regard their health as “a treasury asset.”97

Lenin’s condition showed no improvement. He grumbled that he, who in the past had been able to work for two, now could hardly do the work of one. He spent most of March 1922 resting in the country, where he closely followed the course of events and drafted speeches for the Eleventh Party Congress. He was gruff and irritable, and the physicians treating him misdiagnosed his problem as “neurasthenia induced by exhaustion.”98 At this time his habitual truculence assumed ever more extreme and even abnormal forms: it was while in this state that he ordered the arrest, trial, and execution of the SRs and clergymen.

Lenin’s physical deterioration became apparent at the Eleventh Party Congress, held in March 1922, the last he would attend. He delivered two rambling speeches, defensive in character and replete with ad hominem attacks on anyone who disagreed with him, subjecting some of his closest associates to ridicule. Observing his erratic motions, lapses of memory, and occasional speech difficulties, some doctors now concluded that he was suffering from a more serious malady, namely progressive paralysis, for which there was no cure and which was bound to end before long in total incapacitation and death. Lenin, who as recently as February had denied in a private letter to Kamenev and Stalin that his illness showed any “objective symptoms,”99 apparently accepted this diagnosis, because he began to make preparations for an orderly transfer of authority. This was for him a very painful task, not only because he loved power above all else, but also because, as he would make clear in his so-called “Testament” of December 1922, he thought no one was truly qualified to inherit his mantle.* He further worried that his withdrawal from active politics would set off destructive personal rivalries among his associates.

71. Inessa Armand.

At the time, Trotsky seemed the natural heir to Lenin: who but the “organizer of victory,” as Radek called him,100 had a better right to be his successor? But Trotsky’s claim had more appearance than substance, for he had much going against him. He had joined the Bolshevik Party late, on the eve of the October coup, after subjecting Lenin and his followers for years to ridicule and criticism. The Old Guard never forgave him for his past: no matter what his accomplishments since 1917, he remained an outsider to the party’s inner circle. Although a member of the Politburo, unlike Zinoviev, Stalin, and Kamenev, his principal rivals, he held no executive post in the party and hence lacked a base of support in its cadre, not to speak of the power of patronage. In elections to the Central Committee at the Tenth Party Congress (1921), he came in tenth, behind Stalin and even the relatively unknown Viacheslav Molotov.101 At the next Congress a young Armenian Communist, Anastas Mikoyan, disparagingly referred to him as “a military man” ignorant of the way the party operated in the provinces.102 Nor was Trotsky’s personality an asset. He was widely disliked for arrogance and lack of tact: as he himself admitted, he had a reputation for “unsociability, individualism, aristocratism.”103 Even his admiring biographer concedes he “could rarely withstand the temptation to remind others of their errors and to insist on his superiority and insight.”104 Scorning the collegiate style of Lenin and the other Bolshevik leaders, he demanded, as commander of the country’s armed forces, unquestioned obedience to himself, giving rise to talk of “Bonapartist” ambitions. Thus in November 1920, angered by reports of insubordination among Red Army troops facing Wrangel, he issued an order that contained the following passage: “I, your Red leader, appointed by the government and invested with the confidence of the people, demand complete faith in myself.” All attempts to question his orders were to be dealt with by summary execution.105 His high-handed administrative style attracted the attention of the Central Committee, which in July 1919 subjected them to severe criticism.106 His ill-considered attempt to militarize labor in 1920, not only cast doubts on his judgment, but reinforced suspicions of Bonapartism.107 In March 1922 he addressed a long statement to the Politburo, urging that the party withdraw from direct involvement in managing the economy. The Politburo rejected his proposals and Lenin, as was his wont with Trotsky’s epistles, scribbled on it, “Into the Archive,” but his opponents used it as evidence that Trotsky wanted to “liquidate the leading role of the Party.” 108 Refusing to involve himself in the routine of day-to-day politics, frequently absent from cabinet meetings and other administrative deliberations, Trotsky assumed the pose of a statesman above the fray. “For Trotsky, the main things were the slogan, the speaker’s platform, the striking gesture, but not routine work.”109 His administrative talents were, indeed, of a low order. The hoard of documents in the Trotsky archive at Harvard University, with numerous communications to Lenin, indicate a congenital incapacity for formulating succinct, practical solutions: as a rule, Lenin neither commented nor acted on them.

72. Trotsky, 1918.

For all these reasons, when in 1922 Lenin made arrangements to distribute his responsibilities, he passed over Trotsky. He was much concerned that his successors govern in a collegial manner: Trotsky, never a “team player,” simply did not fit. We have the testimony of Lenin’s sister, Maria Ulianova, who was with him during the last period of his life, that while Lenin valued Trotsky’s talents and industry, and for their sake kept his feelings to himself, “he did not feel sympathy for Trotsky”: Trotsky “had too many qualities that made it extraordinarily difficult to work collectively with him.”* Stalin suited Lenin’s needs better. Hence, Lenin assigned to Stalin ever greater responsibilities, with the result that as he faded from the scene, Stalin assumed the role of his surrogate, and thus in fact, if not in name, became his heir.

In April 1922, Stalin was appointed General Secretary, that is, head of the Secretariat: this was formalized at the Party Plenum on April 3, on Lenin’s personal instructions.* It has been asserted, by contemporaries in a position to know, that Lenin took this step because Stalin was continuously warning him of the danger of splits in the party and assuring him that he, Stalin, alone was capable of averting them.110 But the circumstances of this event remain obscure, and it has also been suggested that Lenin had no idea of the importance of Stalin’s promotion to a post that until then had been of very minor significance.111

The Secretariat under Stalin’s direction had two responsibilities: to monitor the flow of paperwork to and from the Politburo, and to prevent deviations in the party.

In his report on organizational matters to the Eleventh Party Congress, Molotov complained that the Central Committee was swamped with paperwork, much of it trivial: in the preceding year, it had received 120,000 reports from the local branches of the party, and the number of questions it had to take up increased by almost 50 percent.112 At the same Congress, Lenin ridiculed the fact that the Politburo had to deal with such weighty issues as imports of meat conserves from France.113 He thought it absurd to have him sign every directive issued by the government.114 One of the tasks of the General Secretary was to ensure that the Politburo received only important papers and that its decisions were properly implemented.115 In this capacity, the Secretary was responsible for preparing the Politburo agenda, supplying it with pertinent materials, and then relaying its decisions to the lower party echelons. These functions made the Secretariat a two-way conveyor belt. But because it was not, strictly speaking, a policy-making post, few realized the potential power that it gave the General Secretary:

Lenin, Kamenev, Zinoviev, and to a lesser extent, Trotsky, were Stalin’s sponsors to all the offices he held. His jobs were of the kind which would scarcely attract the bright intellectuals of the Politburo. All their brilliance in matters of doctrine, all their powers of political analysis would have found little application either at the Workers’ and Peasants’ Inspectorate or at the … Secretariat. What was needed there was an enormous capacity for hard and uninspiring toil and patient and sustained interest in every detail of organization. None of his colleagues grudged Stalin his assignments.116

The key to Stalin’s rising power was the combination of functions vested in him as member of the Orgburo and chairman of the Secretariat. At his command, officials could be promoted, relocated, or dismissed. This power Stalin used not only to eliminate anyone who challenged the judgment of the Central Committee, as Lenin wanted, but to appoint functionaries personally loyal to him. Lenin’s intention was to have the General Secretary ensure ideological orthodoxy by keeping close watch on party personnel and rejecting or expelling divisive elements. Stalin promptly realized that he could use these powers to enhance his personal authority in the party by appointing to responsible posts, in the guise of safeguarding ideological purity, individuals beholden to him. He drew up registers (nomenklatury) of party officials qualified for executive positions, and selected for appointment only those listed on them. In 1922, Molotov reported that the Central Committee kept files on 26,000 party functionaries (or “party workers,” as they were euphemistically called) subject to close scrutiny; in the course of 1920, 22,500 of them had received assignments.117 To make certain nothing escaped his attention, Stalin required provincial party secretaries to report to him personally once a month.118 He also made an arrangement with Dzerzhinskii to have the GPU send his Secretariat on the seventh day of every month its regular summaries.119 In this manner Stalin acquired unrivaled knowledge of party affairs down to their lowest levels, knowledge that, together with the power to make appointments, gave him effective control of the party machine. By ruling that a high proportion of party documents, including protocols of plenums, were secret, he withheld this information from his potential rivals.120

Stalin’s self-aggrandizement did not go unnoticed: at the Eleventh Congress an associate of Trotsky’s complained he had taken on too many responsibilities. Lenin impatiently brushed such objections aside.121 Stalin got things done, he understood the supreme need to preserve party unity, he was modest in his behavior and personal needs. Later, in the fall of 1923, Stalin’s associates, led by Zinoviev, who in a private letter to Kamenev referred to “Stalin’s dictatorship,” held a secret conclave to curb his powers. It failed because Stalin cleverly outmaneuvered his rivals.122 In his eagerness to stir the cumbersome machine of state and to prevent splits, Lenin endowed Stalin with powers that he himself six months later would characterize as “boundless.” By then it would be too late to curb them.

Lenin did not anticipate that as a result of the regime he had introduced, Russia would come under one-man rule. He thought that impossible. In January 1919, in an exchange with the Menshevik historian N. A. Rozhkov, who had urged him to assume dictatorial powers, he wrote:

As concerns “personal dictatorship,” if you pardon the expression, it is utter nonsense. The apparatus has grown altogether gigantic—in some respects [excessive]. And under these conditions, a “personal dictatorship” is (in general) unrealizable.123

In fact, he had little idea how gigantic the apparatus had grown and how much money it cost. He reacted with disbelief to information supplied by Trotsky in February 1922 that in the preceding nine months the party’s budget absorbed 40 million gold rubles.*

He was worried about something different: he dreaded the prospect of the party being torn apart by rivalries at the top and paralyzed by the bureaucracy from below. He had not expected either to be a threat. Communists treated everything that happened as inevitable and scientifically explicable except their own failures: here they became extreme voluntarists, blaming whatever went wrong on human error. To a detached observer the problems that troubled Lenin and jeopardized his revolution appear embedded in the premises of his regime. One need not share Isaac Deutscher’s romantic view of the Bolsheviks’ aspirations to accept his analysis of the contradictions they had created for themselves:

In its dream the Bolshevik party saw itself as a disciplined yet inwardly free and dedicated body of revolutionaries, immune from corruption by power. It saw itself committed to observe proletarian democracy and to respect the freedom of the small nations, for without this there could be no genuine advance to socialism. In pursuit of their dream the Bolsheviks had built up an immense and centralized machine of power to which they then gradually surrendered more and more of their dream: proletarian democracy, the rights of small nations, and finally their own freedom. They could not dispense with power if they were to strive for the fulfillment of their ideals; but now their power came to oppress and overshadow their ideals. The gravest dilemmas arose; and also a deep cleavage between those who clung to the dream and those who clung to the power.124

This link between premise and effect escaped Lenin. In the last months of his active life, he could think of nothing better to safeguard his regime than restructuring institutions and reassigning personnel.

He reluctantly concluded that the fusion of party and state organs that he had enforced since taking power could not be permanently institutionalized because it depended on one person, himself, directing both in his double capacity as Chairman of the Sovnarkom and titular leader of the Politburo. The arrangement, in any event, was becoming unworkable because the policy-making organs of the party were becoming clogged from the multitude of affairs, important and petty, mostly petty, that the state apparatus forwarded to them for decision. After Lenin’s partial withdrawal, the old arrangement had to be altered. In March 1922, Lenin protested that “everything gets dragged from the Sovnarkom to the Politburo,” and conceded that he bore blame for the resulting disarray, “because much that concerned links between the Sovnarkom and the Politburo was done personally by me. And when I had to leave, it transpired that the two wheels did not work in a coordinated manner.”125

In April 1922, at the same time that Stalin assumed the post of General Secretary, Lenin came up with the idea of naming two trusted associates to act as watchdogs over the state apparatus. He suggested to the Politburo the creation of two deputies (zamestiteli, or zamy for short), one to run the Sovnarkom, the other the Council of Labor and Defense (Sovet Truda i Oborony, or STO).* Lenin, who chaired both institutions, suggested the agrarian specialist Alexander Tsiurupa for the Sovnarkom and Rykov for the STO, each to oversee a number of commissariats.† Trotsky, who was given no voice in economic management, subjected this proposal to harsh criticism, arguing that the zamy’s responsibilities were so broad as to be meaningless. He believed that the economy would continue to perform unsatisfactorily unless subjected to authoritarian methods of management from the Center, without Party interference126—an argument widely interpreted to mean that he aspired to become “dictator” of the economy. Lenin called Trotsky “fundamentally wrong” and accused him of passing ill-formed judgments.127

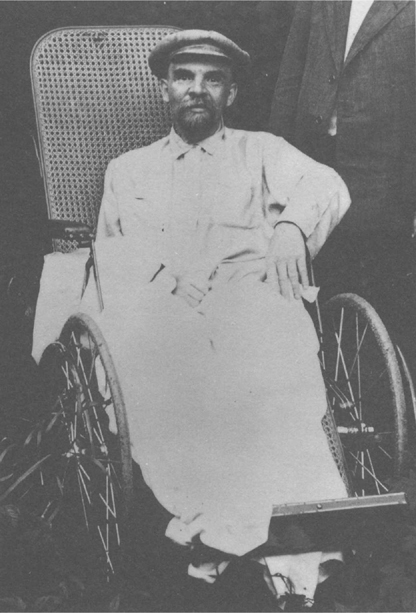

On May 25–27, 1922, Lenin suffered his first stroke, which resulted in a paralysis of the right arm and leg and deprived him temporarily of the ability to speak or write. For the next two months he was out of commission, most of the time resting at Gorki. Physicians now altered their diagnosis to read arteriosclerosis of the brain, possibly of hereditary origin (two of Lenin’s sisters and his brother would die in a similar manner). During this period of forced absence, his most important posts—the rotating chairmanships of the Politburo and of the Sovnarkom—were assumed by Kamenev, who also headed the Moscow Party organization. Stalin chaired the Secretariat and the Orgburo, in which capacities he directed the day-to-day business of the party apparatus. Zinoviev was chief of the Petrograd Party organization and the Comintern. The three formed a “troika,” a directory that dominated the Politburo and, through it, the party and state machines. Each, even Kamenev, who was Trotsky’s brother-in-law, had reasons for joining forces against Trotsky, their common rival. They did not even bother to inform Trotsky, who was vacationing at the time, of Lenin’s stroke.128 They were in constant communication with Lenin. The log of Lenin’s activities during this time (May 25–October 2, 1922) indicates Stalin to have been the most frequent visitor to Gorki, meeting with Lenin twelve times; according to Bukharin, Stalin was the only member of the Central Committee whom Lenin asked to see during the most serious stages of his illness.* According to Maria Ulianova, these were very affectionate encounters: “V. I. Lenin met [Stalin] in a friendly manner, he joked, laughed, asked that I entertain him, offer him wine, and so on. During this and further visits, they also discussed Trotsky in my presence, and it was apparent that here Lenin sided with Stalin against Trotsky.”129 Lenin also frequently communicated with Stalin in writing. His archive contains many notes to Stalin requesting his advice on every conceivable issue, including questions of foreign policy. Worried lest Stalin overwork himself, he asked that the Politburo instruct him to take two days’ rest in the country every week.130 After learning from Lunacharskii that Stalin lived in shabby quarters, he saw to it that something better was found for him.131 There is no record of similar intimacy between Lenin and any other member of the Politburo.

73. The “troika,” from left to right: Stalin, (Rykov), Kamenev, Zinoviev.

After obtaining Lenin’s consent and then settling matters among themselves, the triumvirate would present to the Politburo and the Sovnarkom resolutions that these bodies approved as a matter of course. Trotsky either voted with the majority or abstained. By virtue of their collaboration in a Politburo that at the time had only seven members (in addition to them and the absent Lenin, Trotsky, Tomskii, and Bukharin), the troika could have its way on all issues and isolate Trotsky, who had not a single supporter in that body.