Chapter 5

‘Developmental’ States and Economic Growth at the Sub-National Level: The Case of Penang (1970-2005)

Francis E. Hutchinson162

Introduction

When electronics manufacturers go to Malaysia, they do not stop in the national capital, Kuala Lumpur, but fly directly to production sites in a distant province, Penang. This small state, near Thailand, with a population of some 1.5 million, has established a reputation as a dynamic hub for technology-intensive goods such as semiconductors and hard disk drives.

Penang has created an environment that seems different – and slightly separate – from the rest of the country. Investors here do not liaise with the federal government, but rather with state government agencies for incentives, permits, and licenses. They source for components, design work, or labour from a variety of dynamic firms nearby, and send their products via local airports or the internet.

Penang is a ‘different’ state for a variety of reasons. It hosts a long tradition of political activity and is the home of personalities such as the [former] Prime Minister, Abdullah Badawi, and Opposition leader, Anwar Ibrahim. Penang is also the only state with a Chinese majority and Chief Minister, and has been governed by a small, regionally based multi-ethnic party since 1969.

Traditionally a centre for shipping, finance, and trade, Penang overhauled its economic model in the 1970s, following a deep recession. Since then, the state has received several waves of strategic foreign investment and reaped the benefits. From having a per capita income 12 per cent below the national average in 1971, Penang now enjoys a per capita income almost 50 per cent above the national average.163

The ‘motor’ of the Penang’s industrial sector is electronics, which accounts for approximately half of all employment in the manufacturing sector. In 2005, this comprised some 200 multinational electronics firms employing 110,000 workers, in addition to some 350 firms and 25,000 workers in downstream sectors as well as an unknown quantity of firms in the informal sector.164

Penang is not the only centre for electronics manufacturing in Malaysia. The Klang Valley and Johor Baru also house sizeable numbers of firms. However, what distinguishes Penang is not the size of its electronics industry, but the quality of its operations. Penang has specialised in the semiconductor and hard disk drive sectors. In contrast, the Klang Valley and Johor Bahru have specialized in less technologically intensive sectors. In addition, more than the other two states, multinational corporations (MNCs) have relocated their more value-added tasks to their Penang affiliates such as research and development, supply chain management, and customer care. In particular, Penang has acquired a reputation for expertise in areas such as semiconductor design.165

The theory of comparative advantage argues that patterns of industry location are driven by the geographical distribution of factors of production. Yet, following this logic, Penang’s initial endowments of scarce capital and greater supplies of land and labour, would have restricted it to labour-intensive activities. Thus, it is pertinent to ask how it altered its comparative advantage away from hosting simple labour-intensive tasks towards more complex, capital-intensive ones.

Research carried out on countries that have successfully ‘upgraded’ their comparative advantage, such as Japan, Korea, and Taiwan, suggests that part of their success lies in their institutional contexts. In particular, ‘developmental’ state agencies fostered the transformation of their economies through effective proactive policymaking and close ties with the private sector.

In general, the Developmental State literature emphasizes three institutional characteristics necessary for promoting economic transformation. These characteristics, which this article will use as an operational definition, are: a comparatively autonomous and capable bureaucracy; an over-riding commitment to economic growth; and a high degree of public-private cooperation.166

However, firms in Malaysia have not benefited from this institutional configuration or the same enabling policymaking. Some classify the national state as ‘intermediate’ as opposed to ‘developmental’, because although it has been quite successful at fostering economic growth, it has been less effective at engineering meaningful economic transformation.167 This is attributed to commitments to the interethnic distribution of wealth above economic transformation as well as pervasive rent seeking.168

That said, Malaysia has a multi-level governmental structure, with a central government and state counterparts.169 While state governments have a smaller range of responsibilities than their federal counterpart, they have the crucial authority to tax and spend.170 It is therefore worth asking whether Penang’s local political and institutional context aided its industries to develop more quickly and, in particular, whether its state government was an active participant in this endeavour.

To date, the Developmental State literature has largely retained its focus on the national level. While this framework is useful for establishing whether and how national-level institutions foster a specific industry, it is less useful for understanding why an industry develops in one part of a country and not in another. However, by applying the Development State framework at the sub-national level – in particular concepts such as state capacity, autonomy, and communication with the private sector – much insight can be gained about how and whether local-level institutions and policies influence economic activity.

Thus, this article will analyse the case of Penang by paying particular attention to its economic trajectory on the one hand and its political, institutional, and policy environment on the other. To this end, the next three sections will each look at a specific period of Penang’s history, seeking to examine how the Penang State Government, through its constituent institutions and policy choices, influenced the development of its electronics sector. The fourth and final section will set out the theoretical and policy implications gained from the case study.

The Genesis of Penang’s ‘Developmental State’ (1969-1980)

In the first and arguably most important phase of Penang’s history, a change in the province’s political context had far-reaching effects on its institutional framework, policy framework, and economic structure.

The Political and Institutional Context

The roots of Penang’s economic success can be found in the events of 1969 when state level elections marked a turnaround in its political and economic fortunes. That year, after a decade-long recession and rising unemployment, Penang’s citizens voted out the local representative of the ruling Alliance coalition.

Gerakan, a newly formed social democratic and multi-racial party, won 16 out of 24 seats. Drawing its cadres from academic and professional circles, the party promised a more independent stance vis-à-vis the national government, whose import substitution policies had been detrimental to Penang’s free trade economic model.

The key figure in Gerakan was its Chairman and the Chief Minister of Penang, Lim Chong Eu. A member of the first generation of Malaysian politicians, he had been President of the Malaysian Chinese Association (MCA) in the late 1950s. Lim thus enjoyed extensive contacts at the national level as well as considerable legitimacy among the Chinese community for his efforts while at the helm of the MCA.

Lim Chong Eu’s formidable political acumen served the state well. In the wake of the country’s racially motivated riots of 1969, he foresaw that Penang’s prospects would suffer if it remained an opposition-led state in the new climate of heightened Malay nationalism. Thus, Lim negotiated Gerakan’s incorporation into the ruling coalition – albeit at the cost of some sections of his party leaving. Instead of being the Chief Minister of a marginalised state, Lim thus became head of the Penang branch of the ruling coalition and used this position to retain an important modicum of independence.171

Lim moved quickly to bolster this tacit room for manoeuvre. He appropriated a statutory body charged with overseeing economic development in the state, the Penang Development Corporation (PDC), as his implementing arm. The PDC’s status as a statutory authority meant that, at least initially, the Penang State Government had considerable autonomy from the federal government in establishing its strategic direction and appointing staff.

This was done to great effect, as Lim personally chose a core of staff members, many from outside Penang. Despite earning lower salaries than in the private sector, PDC employees enjoyed considerable prestige, as the Corporation was the premier institution of the State Government. During the 1970s, the PDC remained relatively small, with some 70 professionals out of a total of 300 staff. With an average tenure of 17 years, it had a very low attrition rate and was able to accumulate various layers of experienced personnel.172

This institutional capability was backed up by considerable operational freedom and good strategic direction. Lim chose the PDC’s Board Members with care, seeking to gather input and support from key party and federal government officials and generating an operational vision for the state. In addition, informal information sessions with technical experts were regularly held to discuss innovative ways of tackling problems.

Policies

The Federal Government had commissioned an in-depth study of Penang’s economic situation in the 1960s. Citing the state’s dearth of natural resources, the Nathan Report recommended that Penang foster manufacturing and tourism in order to diversify the economy and reduce unemployment. Lim and the PDC took this report as their blueprint for action.

However, Malaysia’s high degree of centralization and formula for allocating revenue to state governments meant that the Penang State Government had a limited resource base. Thus, the PDC resorted to unorthodox means to raise funds. The Corporation capitalized on state government control over land to create a property bank through acquisitions and strategic purchases. After converting the land into industrial sites, it then sold them at near-market rates. The PDC was also active in residential development and used the profits to subsidize investments elsewhere.

Second, the PDC marketed Penang aggressively to overseas investors, in particular targeting electronics firms due to their labour-intensive nature as well as possibilities for subsequent higher value-added activities. Thus, the PDC regularly embarked on overseas trade missions, specifically targeting US-based semiconductor manufacturers. In spite of limited real power, the PDC was able to make the investment process quicker and more agile, relying on a well-nurtured relationship with bureaucrats in the federal Malaysian Industrial Development Authority.173

Third, the Corporation moved to provide infrastructure for investors, including industrial parks, land, trained workers, and nearby low-cost housing for the rapidly growing workforce. Thus, the PDC pioneered the building of free trade zones in Malaysia, setting up the first in 1972 and managing four free trade zones and four industrial parks by 1980.174

Fourth, the PDC invested considerable capital in a variety of startups. By 1980, this totalled some USD 6.4 million in 17 firms. These investments encompassed: ship-building; mushroom farming with upstream operations in food-processing and marketing; real estate; furniture; textiles; electronics; and high-quality glass fabrication.175 While many of the firms did not turn out to be profitable, these investments served other purposes, such as: demonstrating the state government’s commitment to a specific sector; reducing risk for local entrepreneurs; and attempting to diversify the economy.

Fifth, the PDC helped reduce information asymmetries through fostering links between international investors and local firms in the metalwork and fabricated metal product sectors. Relations between the federal government and the predominantly Chinese manufacturing sector had grown tense following the introduction of a raft of ethnically based affirmative action policies. However, the PDC’s intermediary role was possible due to the good rapport that Lim had with local businessmen, many of whom he knew through the Chinese Chamber of Commerce. The Chief Minister then began to encourage MNC managers to source components locally, and brokered meetings with local firms.176

Sixth, the PDC created mechanisms for targeted skill provision. While the Corporation’s strategic investment in the electronics sector did not yield profits, it provided a nucleus of skilled labourers, almost all of whom were subsequently recruited by MNCs. This was bolstered by a training centre that trained school leavers in skills needed by the nascent manufacturing sector.

Outcomes

The initial push to attract investment bore fruit, and by 1972, there were 17 electronics facilities employing 12,000 workers in Penang. This grew to 19 firms and 18,700 workers in 1978 and, by 1980, Penang had an electronics sector comprised of a core of 25 electronics assembly facilities, providing employment for almost 25,000 workers in the PDC’s industrial parks.177 While the first electronics operations were labour-intensive, essentially consisting of semiconductor assembly, firms began to upgrade their operations in the late 1970s.

The state’s economy was thus transformed. In 1971, the state’s GDP per capita was 12 per cent below the national average, the most important activity was trading, and manufacturing accounted for only 21 per cent of GDP. In 1980, per capita GDP was 28 per cent above the national average and manufacturing was the state’s prime economic activity, employing 56,000 workers and accounting for 37 per cent of GDP.178

Thus, the PDC’s small size, targeted recruiting, constant access to high-quality information, and political backing enabled it to build considerable institutional capacity. In a relatively short time, the PDC came to approximate the ideal of a ‘developmental’ pilot agency, possessing high levels of bureaucratic capacity and autonomy, in addition to beginning a dialogue with the local private sector. The Corporation’s drive, vision, and communication with the local and international private sector thus enabled the ‘birth’ of an entirely new sector.

Maturity and Consolidation (1980-1990)

The PDC’s role as a ‘developmental’ agency and its success at spurring investment and economic growth came to maturity during the 1980s. The Penang State Government continued with its industrialization drive and quest for investment with considerable success. However, it began to confront the limits of its constitutional responsibilities and trends at the federal level were not in its favour.

The Political and Institutional Context

The autonomy the Penang State Government had in pursuing its industrialization drive was considerably curtailed by Mahathir’s rise to power – as his administration was characterized by the centralization of power and decision-making into the Prime Minister’s Office.179 However, the Penang State Government was able to preserve a degree of autonomy due to: Lim’s status as an elder statesman; Gerakan’s continued electoral success; and the obvious benefits of the industrialization drive.

However, while these factors preserved a degree of political autonomy, at the institutional level the PDC’s margin of manoeuvre decreased markedly after 1980. While the Corporation retained its high level of capacity due to good leadership and low staff turnover, federal policies entailed less autonomy. New legislation meant that all borrowing and investment decisions by state development corporations had to be approved and finances audited by the federal Ministry of Finance. Authority over creation and grading of posts was withdrawn and also placed under federal control. In addition, the federal government began to directly appoint representatives on the PDC Board, which in turn came to have more emphasis on political representation than technical expertise.180

Furthermore, the number of federal government agencies present in Penang increased tremendously, coming to outnumber state government agencies by a margin of three to one by 1991. Responsibilities were often overlapping and contested, including the PDC’s much prized ability to requisition land for real estate development.

Policies

The policy ‘package’ set out the previous decade was retained. Thus, the PDC continued its marketing drive by undertaking trips to East Asia, North America, and Europe, seeking to capitalise on the state’s plentiful and comparatively well-educated labour force. This continued to attract firms engaged in semiconductor testing and assembly, but the PDC also succeeded in attracting firms in more technologically sophisticated sectors such as hard disk drives.181

The State Government also constructed more housing for workers, special facilities for SMEs, and tried to create synergies by grouping local supplier firms together. However, the supply of available land to be converted to industrial use began to run out. As such, the PDC embarked on an ambitious project to reclaim land from the sea.182

The Corporation also continued to encourage ‘self-discovery’, coming to own an investment portfolio of some 24 firms worth USD 8.9 million by 1989. That said, the portfolio’s composition changed somewhat, moving away from testing the feasibility of new activities towards more speculative sectors such as real estate development and leisure facility management. Due to the increased emphasis on real estate development, the PDC began to make a profit after the mid-1980s.

Despite this, the PDC still made some strategic investments. The unprofitable electronics firms set up during the 1970s were phased out and replaced by more technologically intensive operations, including a precision engineering and a biotechnology company. In addition, in an effort to overcome credit constraints, an existing PDC company was tasked with providing venture capital opportunities for local companies.183

In addition to attracting investment, the PDC implemented a variety of policies to overcome information and coordination failures, building on its incipient intermediation efforts of the 1970s. These tentative, low-cost efforts were particularly helpful for local firms affected by the federal government’s policy bias towards large firms. In some cases, the Corporation was able to play a productive role, but in others it was clearly constrained by the federal government’s industrial policy framework.

After the mid-1980s, Penang-based MNCs began to automate their operations, opting to subcontract simple operations to local firms. This was facilitated by established links between local entrepreneurs, PDC officials, and MNC managers. One notable example of these matchmaking efforts was the establishment of Intel’s supplier network, where the PDC played a key supportive role through convincing local firms to take on more sophisticated tasks from MNCs. After the first takers successfully upgraded their operations, subcontracting ties were then expanded to other firms.184

The PDC also carried out crucial intermediary functions between local entrepreneurs and the federal government, lobbying the Ministry of International Trade and Industry to extend duty-free privileges to local firms and to accord them a measure of protection from foreign supplier firms who were crowding them out.185

In 1985, the PDC set up a Small-Scale Industries Unit to cater to small firms. Although it largely ceased to function after two years, it was the first institution with the express remit to cater to small companies, and helped reduce information asymmetries for investors through compiling a directory of local supporting firms in Penang.186

However, while communication between local firms and the PDC was effective, it is important to note that it was not institutionalised. The Unit for small firms disappeared after several years, and most of the matchmaking between firms and multinationals depended on personal connections and did not utilize existing business organisations.

Perhaps the best-known PDC initiative was the establishment of the Penang Skills Development Corporation (PSDC). As the electronics sector grew and labour shortages emerged, the PDC requested the local university and private colleges to provide training for technical personnel. However, the Penang State Government’s authority in this area was limited due to education’s classification as a federal and not a state responsibility.

Thus, the PDC, after extensive consultation with MNC managers, set up the PSDC as an informal ‘training’ institute (which was outside federal control), with a mandate to provide technical training to high school graduates and retrain workers in the electronics industry. Twenty-six ‘founder’ companies, employing some 44,000 workers, had input into the eventual structure of the Centre.187

As a result, the PSDC is largely industry-driven and client companies pool their resources, including equipment, and provide training on industry-specific issues. The PSDC thus acts to reduce information asymmetries by providing a forum for identifying training needs for the manufacturing sector as a whole. Originally providing the PSDC with land and a start-up grant, the PDC also lobbied the federal government to provide a tax deduction for contributing companies.

Despite its evident success, this initiative was confined to training technical personnel and was not sufficient to offset imbalances in the federal government’s education policy. Despite the centrality of the electronics industry to Penang’s economy, enrolments at the local university were biased towards arts and humanities at the expense of technical subjects, and it did not have an engineering faculty until 1987. Thus, skilled workers were in short supply, and linkages between the electronics industry and the university were minimal.

Outcomes

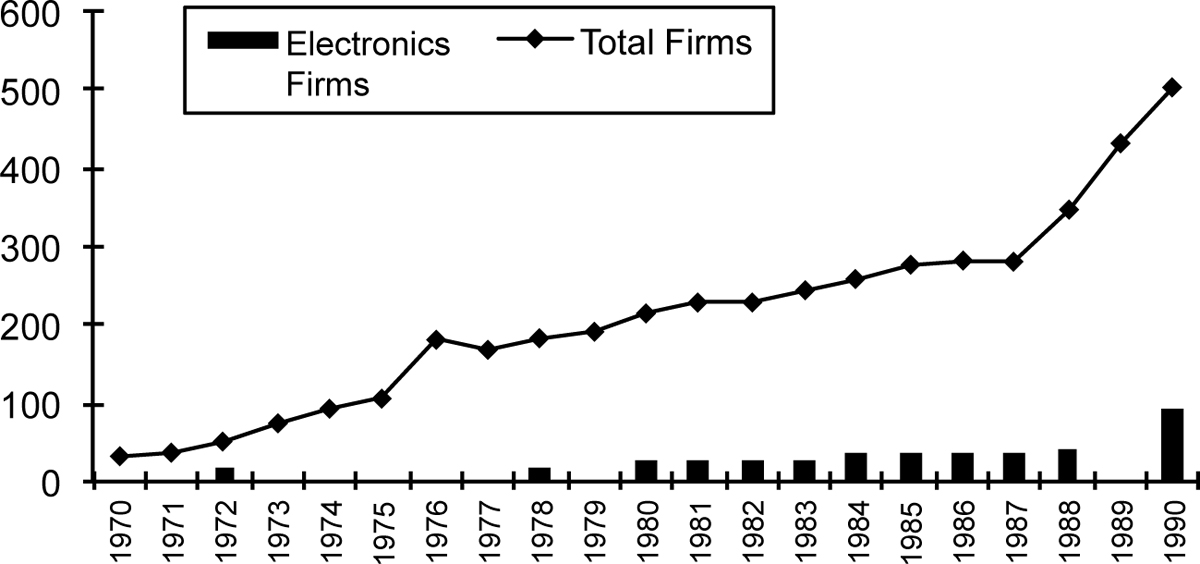

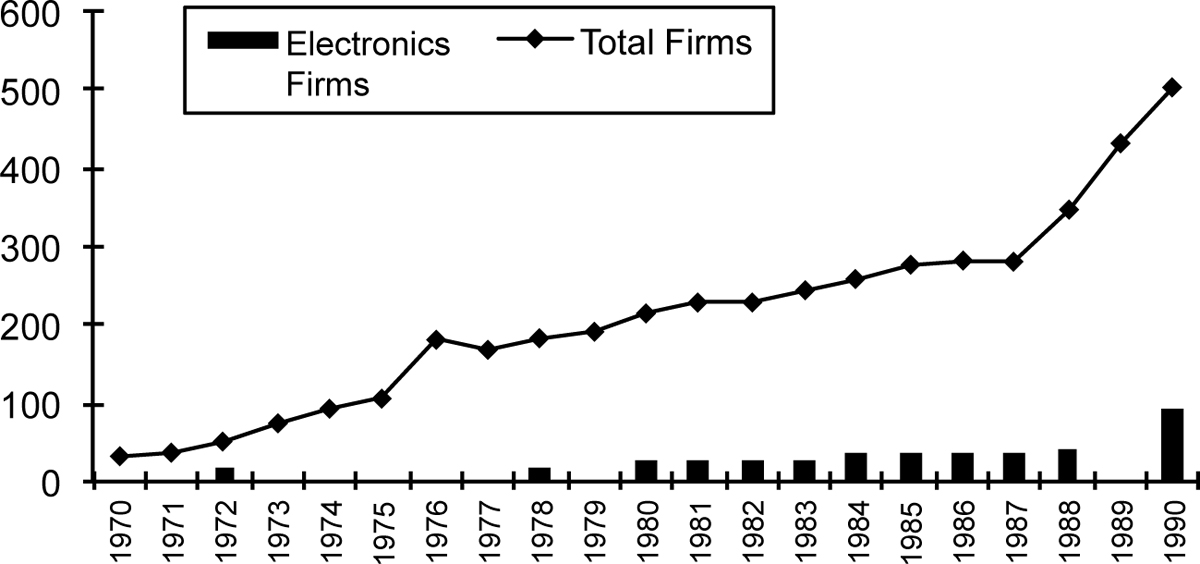

As during the 1970s, Penang’s manufacturing sector grew quickly, weathering downturns in the global electronics industry. As Table 5.1 shows, the number of firms in PDC industrial areas increased at a steady pace during the 1970s and early 1980s, before growing rapidly after 1987. While electronics firms comprised a relatively small portion of the total number of companies, their presence was key for a significant number of enterprises in the metal product, plastics, and packaging sectors. However, in terms of the workforce in the state’s industrial parks, the electronics sector accounted for almost half of the total.

Table 5.1: Firms in PDC Industrial Areas (1970-1990)

Sources: ISIS/PDC, Penang Strategic Development Plan, Penang: Penang Development Corporation, 1991 p. 7-21. Rasiah, R. ‘Technological Change and the Electronics Industry: The Impact on Penang in the 1980s’, In Changing Dimensions of the Electronics Industry in Malaysia: The 1980s and Beyond, edited by S. Narayanan, Rasiah, R., M.L. Young and B.Y. Yeang, pp. 51-80. Malaysian Economic Association and Malaysian Institute of Economic Research, Penang and Kuala Lumpur. 1989, pp. 68.

Table 5.2: Employment in PDC Industrial Areas (1970-1990)

Sources: ISIS/PDC, Penang Strategic Development Plan, Penang: Penang Development Corporation, 1991 p. 7-21. Rasiah, R. ‘Technological Change and the Electronics Industry: The Impact on Penang in the 1980s’, In Changing Dimensions of the Electronics Industry in Malaysia: The 1980s and Beyond, edited by S. Narayanan, Rasiah, R., M.L. Young and B.Y. Yeang, pp. 51-80. Malaysian Economic Association and Malaysian Institute of Economic Research, Penang and Kuala Lumpur. 1989, pp. 68.

In spite of a big market downturn halfway through the decade, the 1980s were to prove the most fertile period for the establishment of successful domestic enterprises. By 1985, some 35 firms employing 2,400 people provided supporting services to the electronics sector. This encompassed operations such as precision engineering, metal stamping, plastic moulds, manufacture of automation systems, and chemical products. By the end of the decade, the cluster had grown to 45 firms.188

However, while Penang continued to attract FDI and multinationals with the ensuing job creation and economic growth, the structural limits of the MNC-led industrialization model began to emerge. While the state’s manufacturing sector grew very quickly, it also narrowed substantially and exposed the state to the instability of the international market.

The industrial structure of the electronics sector was also unbalanced. While a group of local electronics firms had emerged, the electronics sector still consisted of a large group of big multinationals and a set of smaller domestic firms that relied exclusively on them for business. In addition, due to the onerous technological and capital requirements of the electronics industry, it also remained largely segregated from the local economy.

After some 20 years in power under Gerakan, the Penang State Government’s drive to attract investment to, and nurture the development of, the electronics sector had brought many benefits. In 1990, the state enjoyed a per capita income some 20 per cent above the national average. Its manufacturing sector accounted for 46 per cent of GDP, and the state’s industrial parks housed some 500 firms, which employed almost 120,000 people.189

Despite its successes, the Penang State Government began to confront the limits of what it could do during this period. Crucial decisions, particularly regarding investment incentives, university education, and university-industry linkages lay outside the scope of its constitutionally mandated powers.

The Eclipse of the Developmental State? (1990-present)

Penang entered the most recent period of its history with essentially the same policy framework. However, political and institutional developments in the state and in Malaysia as a whole as well as structural changes in the electronics industry meant that the ‘developmental’ role played by the State Government began to fade.

The Political and Institutional Context

Although Penang’s development over the previous two decades had been prodigious, Lim Chong Eu’s 21-year tenure reached an end in 1990 with the loss of his seat to the opposition Democratic Action Party. However, Gerakan and the national ruling coalition, Barisan Nasional, retained control of the state. As national head of Barisan Nasional, Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad chose Lim’s Political Secretary, Koh Tsu Koon, as his successor.

While Gerakan remained in power, this change in leadership had important structural implications. Rather than negotiating terms of entry into a coalition as Lim had, Koh was appointed by the Prime Minister and could, in theory, be replaced. This different power relation was reinforced by Koh’s relative youth, lesser political stature, and less ‘personal’ relationship with Mahathir.

This subordinate position was reinforced by factional infighting within Gerakan, as well as increasing competition for votes from the Malaysian Chinese Association and the Democratic Action Party. Gerakan was only able to retain the Chief Minister’s seat due to support from the largest party in the national coalition, the United Malays’ National Organisation (UMNO). This came at a price and in 1992, the post of Deputy Chief Minister was created and given to an UMNO official.190

However, this decreasing room for manoeuvre was compounded by other developments at the national level. During the 1990s and up until Abdullah Badawi’s accession to power in 2003, Penang was not a priority for federal government initiatives. Under the Mahathir administration, Kuala Lumpur had received copious federal funds to upgrade its seaport, airport, and public transport system in addition to strategic investments in the automobile, electronics, and IT industries. This is not to mention prestige projects like the Petronas Towers and the Multimedia Super-Corridor.

Conversely, long-standing calls for similar measures in Penang went unheeded. In 1996, a high-tech park, partially funded by the federal government, was set up in the neighbouring state of Kedah. Possessing a high-end wafer fabrication facility, it succeeded in persuading some firms to relocate there from Penang. In 1997, the federal government almost succeeded in downgrading Penang’s airport and rerouting all international flights to Kedah. And, despite the electronics industry’s need for cutting-edge telecommunications and access to skilled workers, Penang’s industrial parks were granted Multimedia Super-corridor status only in 2005. It was only with the Northern Corridor Economic Region launched in 2007, with its plans to reduce regional inequality and revitalise the economy in Malaysia’s northern states that Penang stood to obtain much-needed investment in infrastructure.

At the institutional level, the high degree of capacity established under Lim Chong Eu’s tenure was maintained to a degree. Under Koh’s leadership, the Penang Development Corporation retained its image as a technocratic, professional institution. It was rated first among state governments for the quality of its development projects, and received commendations for good project implementation.191

However, the innovative potential seen in prior decades was waning. Most of the original staff, including the Corporation’s first General Manager, retired during the 1990s. And, issues had begun to emerge in areas where the PDC once excelled. The long time it took to obtain permits, the intermittent follow-up with international investors, and spotty maintenance of infrastructure are some of the complaints that were aired. And, perhaps most critically, constant calls were made for the government to do more for local entrepreneurs.192

During this period, the Penang State Government began to set up new institutions in an attempt to revitalize its economy. In 1997, it established the Socioeconomic and Environmental Research Centre to contribute technical and policy information and bolster planning capacity at the state level. In 2003, the Collaborative Research and Resource Centre (CRRC) was established to address issues facing local entrepreneurs, in particular helping small firms access research and development facilities and tap overseas markets.

In late 2004, the Penang State Government implemented a large-scale restructuring. An entirely new agency, InvestPenang, was created. Absorbing the CRRC, InvestPenang became the peak agency charged with facilitating investment and fostering industrial development in the state. In contrast, the PDC was left to focus on tourism and real estate development.

Policies

The Penang State Government, under Koh Tsu Koon, was proactive in trying to formulate a strategic vision for the state. Following the tradition set by the Nathan Report, the state government commissioned two strategic plans to provide a blueprint for development. The first Penang Strategic Development Plan (PSDP) came out in 1991, to be followed by the Second Penang Strategic Development Plan (PSDP2) in 2001.

The Plans set out broad-ranging strategic frameworks for the state in the economic, social, environmental, and governance areas. However, attempts to ensure that their recommendations were followed up were less successful, as the Penang State Government’s relative importance vis-à-vis the federal government had waned. After 1990, state branches of federal government agencies concerned with economic development were set up in Penang. However, these agencies followed federal and not state-level priorities, reporting back to Kuala Lumpur for strategic direction. In comparison, during 1999-2003, the Penang State Government’s budget amounted to only 16 per cent of the federal government’s budget for projects in the state.193

During this time, the PDC’s investment portfolio continued to expand, coming to encompass 59 companies in 2002. This included 48 wholly-owned, subsidiary, or associate firms, in addition to investments in 11 publicly listed companies, at a value above USD 70 million.194 The overall performance of these firms was mixed, as 17 companies were either dormant or being liquidated in early 2005. There were, however, some successes. Schott Glass, a PDC joint-venture established in 1974, became a profitable industry leader.195

Continuing the trend established in the 1990s, the portfolio’s composition moved away from manufacturing towards more lucrative operations in real estate, hotel and leisure amenities, and construction. That said, there were a few self-discovery projects in manufacturing as well as investments in industrial parks in Bangalore and Medan.

But, the biggest new area for investment was in supporting industries for the manufacturing sector such as warehousing, air cargo handling, and information technology. In addition, the PDC also made strategic investments in hospitals and private colleges to diversify the state’s economy and make it a regional centre of excellence for health and education.

The PDC, and then InvestPenang, continued Lim Chong Eu’s attempts to establish a dialogue with the private sector through several means. First, consultative councils such as the Penang Economic Council, Penang Industrial Council, and Penang Competitiveness Committee were meant to enable communication with the private sector by consulting industry ‘leaders’. Second, sector-specific ‘clusters’ such as the Software Consortium of Penang, the Penang Automation Cluster, and the Radio-Frequency Cluster were meant to bring local firms together to foster collaboration and provide a single point of contact for international investors.

In addition, the PDC pushed for firms in the state to join Rosettanet, a consortium seeking to establish global standards for manufacturing related e-business, and worked with the federal Ministry of Trade and Industry to set up the organization’s headquarters in Penang. This was potentially an important strategic decision as, through their adoption of these standards, Penang’s SMEs were put in a position where they were able to cater to MNCs regardless of their location.196

However, while these initiatives were useful, they drew their membership from the larger, more established local firms – many of whom had been working with the State Government since the 1980s. Many of these groupings were also rather short-lived, often closing down due to a lack of interest. Furthermore, these groups’ utility was limited by their sector-specific nature, as there was no vision or ‘road-map’ for the sector as a whole. Collaboration between local firms was limited as there were worries about intellectual property theft, and the most visible cases of upgrading were still the result of the effort of individual firms rather than any industry grouping.197

In contrast, there was less systematic communication with smaller and newer firms, in particular those operating on the edge of the formal economy and in most need of help.198 The PSG created the Small and Medium Industry Centre in 1992 to broker contacts between MNCs and local companies as well as provide information on government initiatives. At its height, it had two full-time staff and 180 member companies in the metals, electric, and plastics sectors. However, it experienced a series of managerial problems, including staff shortages, and is now defunct.199

Thus, attempts to reach out to small local firms were limited. There was an apparent information gap between InvestPenang and smaller, local firms. In a rare public display of discontent, in 2006 a prominent member of the local business community took InvestPenang and the state government to task for its lack of responsiveness in dealing with local firms.200

This ‘communication gap’ had an effect. Stock-takes of the electronics sector found that there was a need for institutional support to help companies upgrade. A Japanese government-sponsored study found that: local entrepreneurs did not adequately understand the aims of various initiatives; there was an overlap between federal and state government programs; and initiatives were too oriented to high-technology ventures such as IT and biotechnology as opposed to dealing with basic, technical production issues.201

This was echoed in the findings of a Penang State Government sponsored study. An in-depth survey found that the capabilities of local firms were curtailed by a lack of basic amenities such as: a library with engineering resources; common facilities for basic research; access to elementary market intelligence; readily available loans and venture capital; and technical help in writing grant applications.202

Outcomes

So where did the electronics sector stand at that time?

For the Penang-based electronics industry, the first part of the 1990s was characterized by a continuation of the growth experienced at the end of the 1980s. The basic combination of infrastructure and overseas marketing proved sufficient to attract more investment from electronics MNCs.

In addition, Penang benefited from agglomeration economies, as its existing base of supplier firms and trained workers attracted additional investments. Thus, Japanese firms set up facilities to manufacture consumer electronics items, and Penang became an important offshore centre for American disk drive and computer manufacturers. The disk drive sector expanded quickly, and by 1997 accounted for one third of employment in the sector.203

However, after 1996, the electronics industry changed considerably, as the sector’s technological requirements escalated dramatically. MNCs began to focus more on their core competencies, outsourcing sophisticated manufacturing and logistics tasks to the most dynamic of their supplier firms. In addition, new competitors for labour-intensive tasks emerged, such as China and Vietnam.

These changing requirements exposed the structural shortcomings of Penang’s policy framework and base of supporting industries. Thus, faced by locations with more sophisticated supplier firms and available skilled labour on one hand, and lower-cost locations for labour-intensive operations on the other, MNC investments slowed.

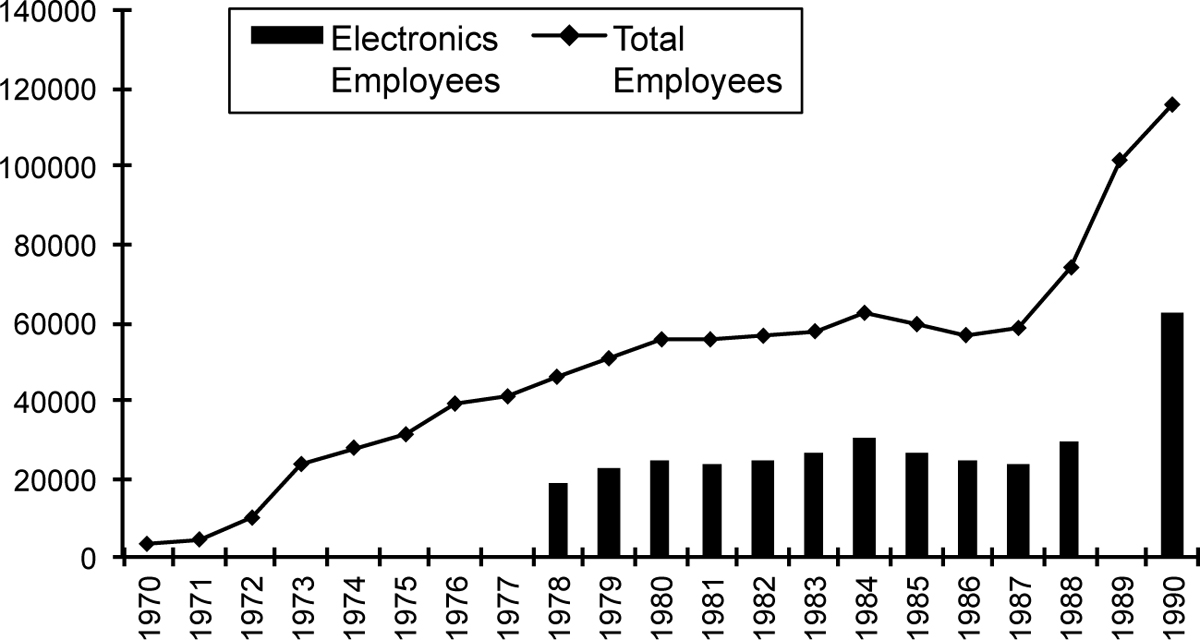

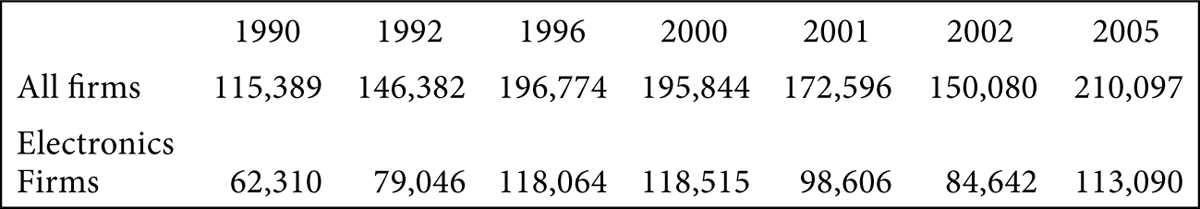

As Table 5.3 shows, the number of firms on PDC land expanded from 500 in 1990 to some 740 in 1996, falling below 700 in 2000, and then climbing subsequently to reach 1170 in 2005. Looking at electronics in particular, the cluster of firms rose from 91 in 1990 to 150 in 2000 and 164 in 2002. From 2002 to 2005, the sector experienced modest growth to reach 188 firms, below the dynamism seen by the manufacturing sector as a whole.

Table 5.3: Firms in PDC Industrial Parks (1990-2005)

Sources: DCT, Annual Survey of Manufacturing Industries in PDC Industrial Areas, Penang: DCT Consulting, 2000-02, SERI “Performance of the Penang Industrial Sector”, Penang Economic Monthly, 2006, No. 6, p. 4.

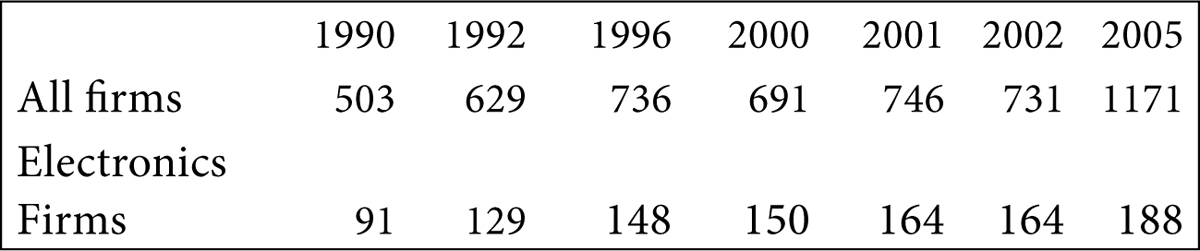

Table 5.4 tracks employment levels in the manufacturing and electronics sectors. For manufacturing, the figure roughly doubled over the 1990-2005 period climbing from 110,000 to 210,000, with a plateau during 1996-2000. For the electronics sector, the picture was somewhat different. Employment levels doubled from 1990 to 1996, jumping from about 60,000 to almost 120,000. From there, employment levelled off, staying at about the same level during the 1996-2000 period, before falling by approximately one-third in 2001-2002. Employment levels then recovered significantly, climbing above 110,000, but not reaching the numbers attained in 1996.

Table 5.4: Employment in PDC Industrial Parks (1990-2005)

Sources: DCT, Annual Survey of Manufacturing Industries in PDC Industrial Areas, Penang: DCT Consulting, 2000-02, SERI “Performance of the Penang Industrial Sector”, Penang Economic Monthly, 2006, No 6, p. 4.

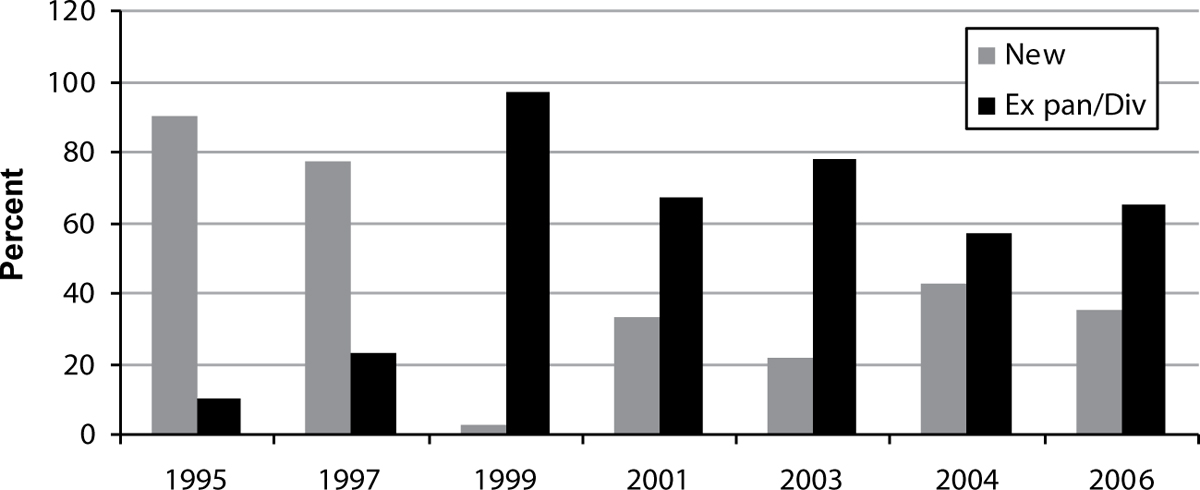

A decline in employment levels is not necessarily bad, as it could signal a transition to higher value-added industries. However, while employment levels had fallen in labour-intensive industries, they were accompanied by falling job levels in skill-intensive industries, such as the hard disk drive industry, electronic component, and software sectors.204 And, as seen in Table 5.5, the composition of investment also changed, away from new investments to re-investment in existing facilities.

Table 5.5: Foreign Direct Investment in Penang’s Electronics Sector

Sources: Annual Survey of Manufacturing Industries in PDC Industrial Areas, 2000-2002, SERI “Penang Economic Report 2006”, Penang Economic Monthly, 2006, No. 12, p.25. Note: 2006 figure for Jan-Sep only.

Thus, Penang’s electronics sector faced real challenges in dealing with the heightened levels of competition that characterised the industry in the early 21st century. Its electronics sector was able to house large amounts of investment that required a lower-level trained workforce and basic infrastructure. However, while it had begun to host more value-added tasks such as design and marketing, it was unable to move past a reliance on low-cost labour as the anchor of its competitive advantage. Thus, despite single-handedly engineering the birth of its electronics industry, the Penang State Government was not wholly successful at fostering its upgrading.

Conclusion

This case study argues that the Penang State Government closely resembled the Developmental State ideal during the 1970s and 1980s. The state government, through the Penang Development Corporation, had a pilot agency that was capable, autonomous, established close links with the local private sector, and pursued economic growth and transformation relentlessly.

However, over time, the PDC came to lose some of its institutional capacity and, particularly, autonomy vis-à-vis the federal government. In addition, with the exception of a small group of established firms, communication with local entrepreneurs was limited. Thus, while the electronics sector continued to grow, real innovative potential was limited to a handful of firms rather than the sector as a whole. This was compounded by rapidly increasing competitive levels in the global electronics industry.

In uncovering a sub-national developmental state, this article shows that there was room for agency at the local level, given certain conditions. Despite an unsupportive national context for its ambitions, the Penang State Government acted as a catalyst for an entirely new industry and revitalized its ailing economy. This, however, was not a permanent state of affairs, and subsequent developments mitigated its transformative potential.

What, then, can be said about the relationship between sub-national institutions and policies and economic development?

First, while national governments have a wider range of responsibilities and sources of revenue than their sub-national counterparts, there is room for manoeuvre at the sub-national level. More than established responsibilities or budgets, institutional configurations and, within that, specific institutions can play a role in fostering new industries.

As seen in Penang, the State Government was, even with limited responsibilities and funds, able to innovate, generate its own resources, and move into areas that were not part of its constitutionally mandated purview.

Second, more than harmonious relations between national and sub-national governments, what is key for successful policy innovation is autonomy. The most creative period of Penang’s recent history, in policy terms, was the 1970s, when the State Government had greater control over staffing of its agencies and their strategic direction. As federal control over sub-national developments expanded, policy innovation decreased.

Third, the ability to access know-how and resources from the international economy is a key enabling agent for sub-national economies. While resources are facilitating in and of themselves, the point is that provincial governments often have fewer resources to invest in ‘lumpy’ high-end infrastructure and research facilities that are vital for maintaining competitiveness. As such, tie-ups with foreign firms may be the only way to acquire them. Thus, in contexts where other domestic regions are recipients of federal largesse, being able to access outside investment and know-how is vital.

Fourth, there may be technical limits to effective state action at the national and sub-national levels. It is clear that basic policies aimed at starting a new industry can work. Marketing trips, targeted infrastructure, training workers, tax breaks, and low labour costs can attract investment. But, as labour costs rise, can government policy successfully foster greater value-added activities to compensate?

Creating an ‘innovative environment’ where firms are able to effectively collaborate and exchange ideas – thus increasing the performance of the sector as a whole – requires patient, long-term, and piece-meal efforts that may surpass the capacity of even the most determined of public servants. This is perhaps best encapsulated in the words of a former PDC senior official, who stated “Getting firms to come – that is easy. Getting them to stay or grow – that is the difficult part”.

A Light Moment. (From left) Penang’s first Chief Minister, Wong Pow Nee; Lim Chong Eu’s wife, Goh Sing Yeng; Wong Pow Nee’s, Elizabeth Law; and Lim Chong Eu.

A rare moment of Lim Chong Eu with Tunku Abdul Rahman, the first Prime Minister of Malaysia.

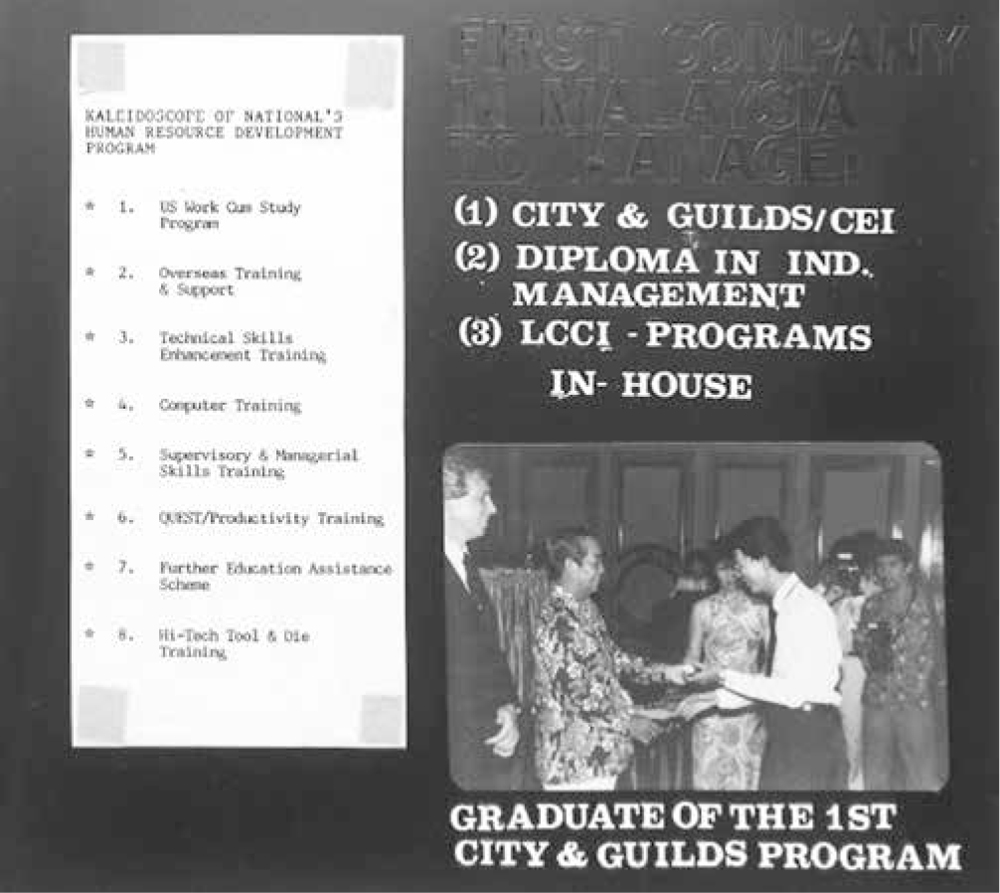

Booklet of National Semiconductors, one of the earliest MNCs to be established in Penang – accepting graduates with technical skills.

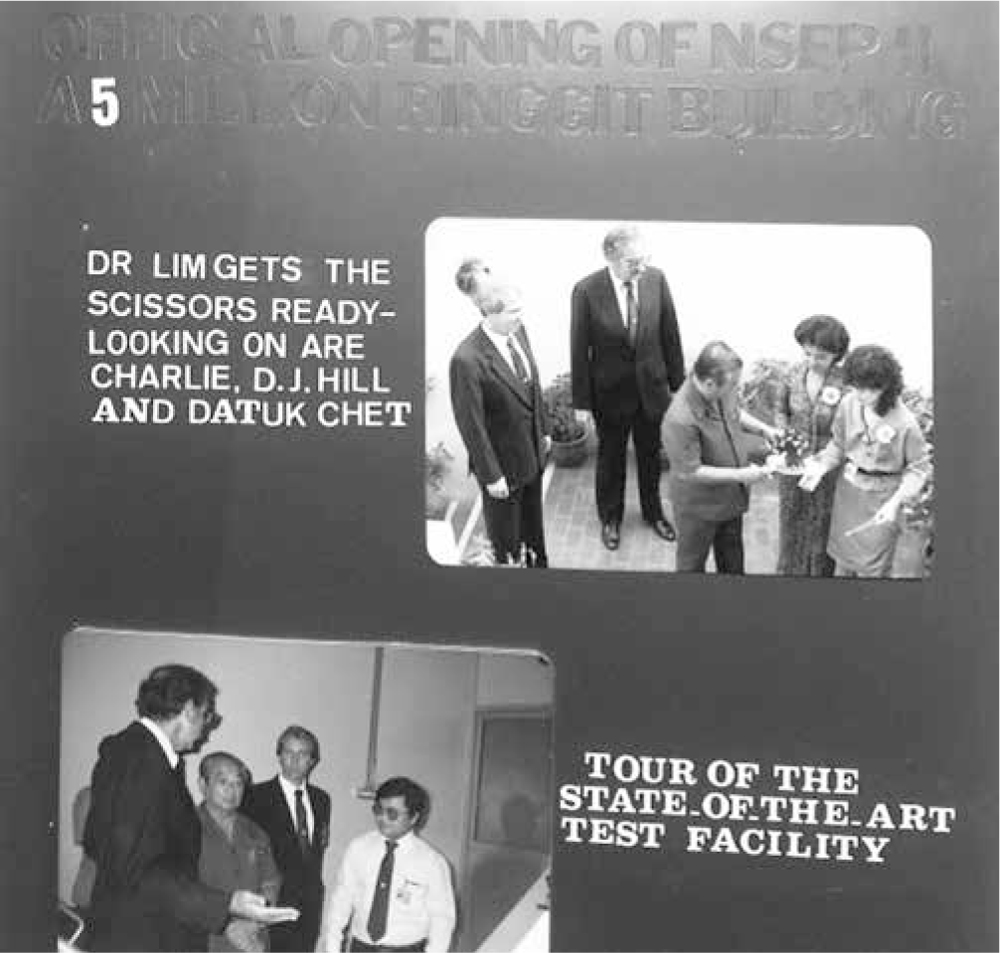

Booklet of National Semiconductors – opening of National Semiconductors by Lim Chong Eu.

Lim Chong Eu greeting HRH Queen Elizabeth II during her royal visit to Penang in 1972.

Celebrating Lim Chong Eu’s 20th Anniversary as Chief Minister of Penang, from 1969 to 1989. Dato Seri Chet Singh, the first General Manager of PDC, is seen on his left.

Lim Chong Eu in a meeting with Donald Dunstan, Premier of South Australia and Tun Abdul Razak, then Prime Minister, in April 1975 – about eight months before Razak passed away.

Lim Chong Eu’s victory moment in the 1969 General Elections where Parti Gerakan Rakyat Malaysia became the first opposition party to rule Penang and Chong Eu became the second Chief Minister of Penang.

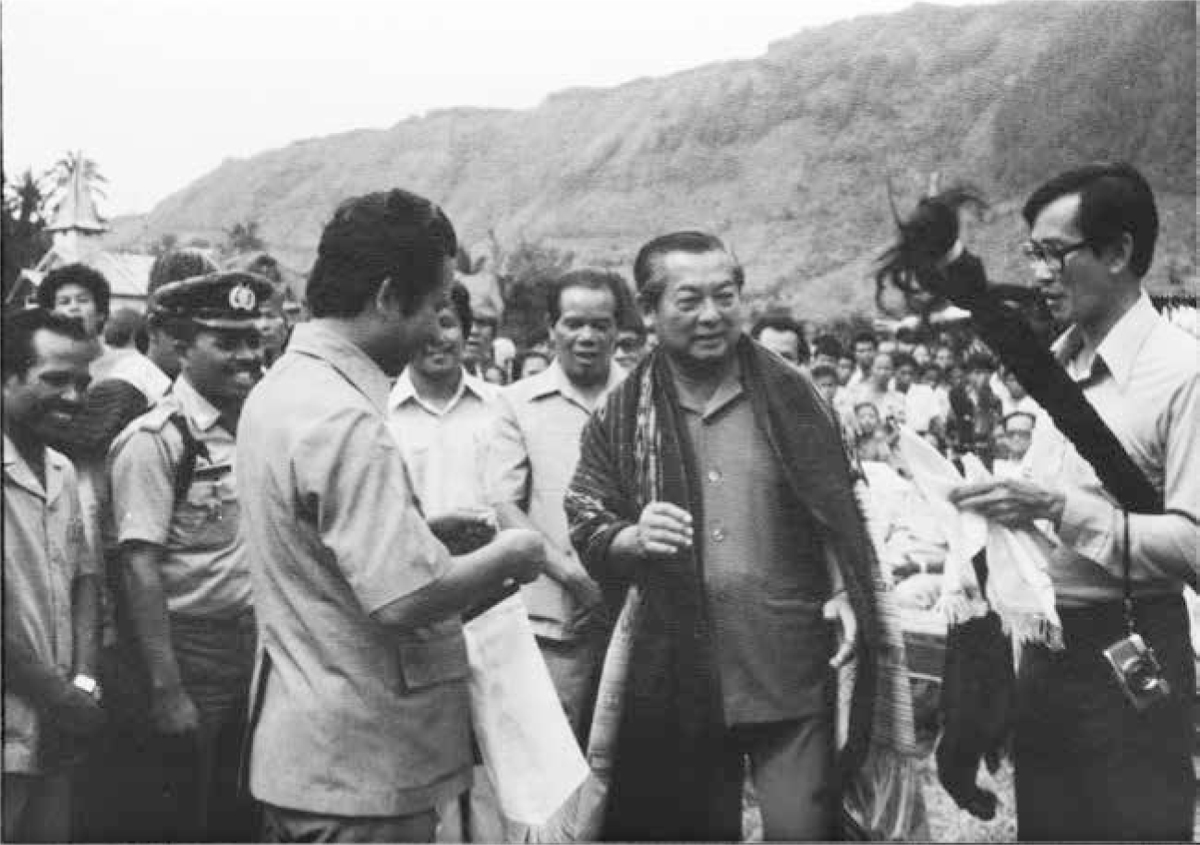

Lim Chong Eu receiving a warm welcome during his visit to Indonesia in the early 1980s.

Lim Chong Eu with Indonesian delegates on a trip to Indonesia in the early 1980s.

Inspecting a potential site for FTZ establishment in the 1970s.

The construction of KOMTAR in the 1970s. KOMTAR was part of Lim Chong Eu’s rejuvenation plan for George Town.

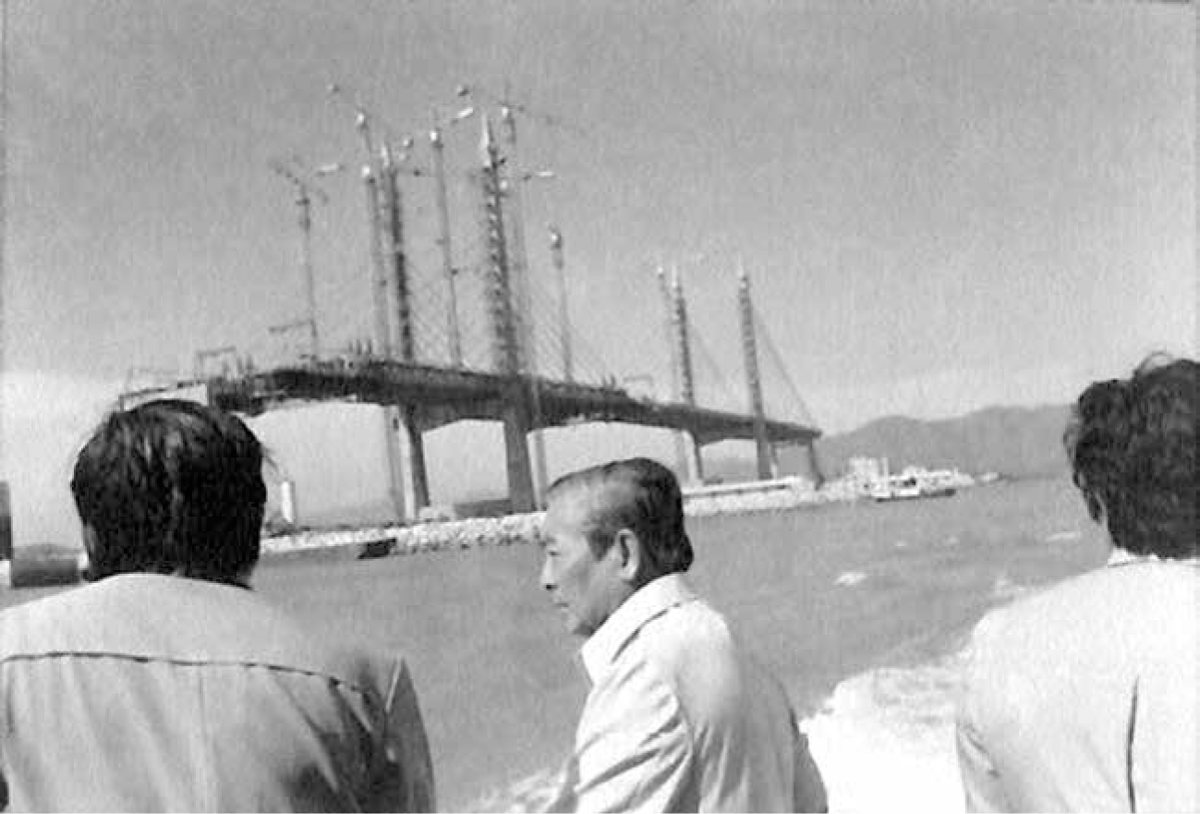

Inspecting the construction of the Penang Bridge in the early 1980s.

Launching of Penang Bridge with Tun Dr Mahathir, then Prime Minister, in the late 1980s. Penang Bridge was a mammoth project realised by Lim Chong Eu as part of the development plan for Penang.

Meeting German delegates in Germany for potential investments in the early 1980s.

162Francis Hutchinson is a senior fellow at ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute and the coordinator of its Malaysia Studies Programme. A version of this case study was first published in Southeast Asian Affairs (2008), and relies on fieldwork undertaken in Penang for the author’s doctoral dissertation in 2004, while he was a visiting researcher at the Socioeconomic and Environmental Resource Institute (now Penang Institute).

163K. Salih, and Young, M.L. ‘Economic Restructuring and the Future of the Semiconductor Industry in Malaysia’, In Changing Dimensions of the Electronics Industry in Malaysia: The 1980s and Beyond, edited by S. Narayanan, Rasiah, R., M.L. Young and B.Y. Yeang, pp. 20-50. Penang and Kuala Lumpur: Malaysian Economic Association and Malaysian Institute of Economic Research, 1989. SERI. Penang Statistics Quarter 2 2006, Penang: Socioeconomic and Environmental Research Institute, 2006, p. 7.

164Penang Statistics Quarter 2 2006, Penang: Socioeconomic and Environmental Research Institute, 2006, p. 3-4. Interviews with industry observers, Penang, 02/04/2004 and 25/02/2004.

165PSDC, Technology Roadmap for the Electrical and Electronics Industry of Penang, Penang: Penang Skills Development Corporation, 2007, p. 3. Ernst D., ‘Global Production Networks in East Asia’s Electronics Industry and Upgrading Perspectives in Malaysia’, In Global Production Networking and Technological Change in East Asia, edited by S. Yusuf, M.A. Altaf and K. Nabeshima pp. 89-158. Washington D.C.: World Bank/Oxford University Press, 2004, p. 139.

166Z. Onis. ‘The Logic of the Developmental State’, Comparative Politics October, (1991): 109-26.

167Doner, R.F., Ritchie, B.K. and Slater, D., ‘Systemic Vulnerability and the Origins of Developmental States: Northeast and Southeast Asia in Comparative Perspective’. International Organization, 2005, 59, p. 327.

168Ritchie, B.K., 2005. ‘Coalitional Politics, Economic Reform, and Technological Upgrading in Malaysia’, World Development, 33(5):745-61, 2005. Gomez, E.T. and Jomo, K.S., Malaysia’s Political Economy: Politics, Patronage, and Profits, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

169The Constitution lays out the responsibilities of each level of governance, with a list each for the federal and state governments and a concurrent list with shared responsibilities. The federal government is responsible for public goods such as defence, internal security, external affairs, and finance, as well as services such as education, health, and transport. The states are given residual responsibilities, consisting of land, forestry, Islamic affairs, and local governments, and the federal government is given precedence over state governments in the event of any dispute (Ninth Schedule, the Constitution of Malaysia).

170‘Economic policy can only be formulated by units which have the ability to tax (i.e. to generate revenues) to fund financial incentives, and the legal authority to initiate and implement a variety of measures affecting the creation, utilization, and geographical distribution of resources.’ H.P. Gray, and Dunning, J.H., ‘Towards a Theory of Regional Policy’. In Regions, Globalization, and the Knowledge-Based Economy, edited by J.H. Dunning, pp. 409-34. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002, pp. 410-11.

171Interview with a former Penang State Government Official, Penang, 05/04/2004.

172Singh, C., 1991. ‘Learning From the Malaysian Experience: A Case Study of the Penang Development Corporation (PDC)’ in Public Enterprise Management: Strategies for Success, pp. 99-116. London: Commonwealth Secretariat, 1989, p. 108. Interviews with former Penang State Government Officials, Penang, 09/02/2004, 03/03/2004.

173Lim Chong Eu, ‘Party Crisis’, Speech to Gerakan Party Members, Penang, 16th July 1971. in Selected Speeches and Statements of Lim Chong Eu 1970-1989. edited by Lim, C.S., Penang: Oon Chin Seang. 1990, p.9-10. Rasiah, R., ‘Politics, Institutions, and Flexibility: Microelectronics Transnationals and Machine Tool Linkages in Malaysia’, In Economic Governance and the Challenge of Flexibility in East Asia, edited by F.C. Deyo, R.F. Doner and E. Hershberg, pp. 165-90. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2001, p. 175. Haggard, S., Lim, P.L. and Ong, A., “The hard disk drive industry in the northern region of Malaysia”, Report 98-04, University of California, San Diego: Information Storage Industry Center. 1998, p. 15.

174PDC. Looking Back, Looking Ahead: 20 Years of Progress, Penang: Penang Development Corporation, 1990, pp. 17-18. PDC, Annual Report, Penang: Penang Development Corporation, 1980, p.25.

175PDC, Annual Report, Penang: Penang Development Corporation, 1980, p.23. PDC, Annual Report, Penang: Penang Development Corporation, 1977, p.13.

176Rasiah, R., ‘Politics, Institutions, and Flexibility: Microelectronics Transnationals and Machine Tool Linkages in Malaysia’, In Economic Governance and the Challenge of Flexibility in East Asia, edited by F.C. Deyo, R.F. Doner and E. Hershberg, pp. 165-90. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2001, p. 176. Jesudason, J.V., Ethnicity and the Economy: The State, Chinese Business, and Multinationals in Malaysia, Oxford University Press, Singapore. 1989, p. 149. Interview with a former Penang Development Corporation Official, Kuala Lumpur, 10/05/2004.

177ISIS/PDC, Penang Strategic Development Plan, Penang: Penang Development Corporation, 1991 p. 7-21. PDC, Annual Report, Penang: Penang Development Corporation, 1980, p. 19.

178PDC, Annual Report, Penang: Penang Development Corporation, 1980, p.9.

179Funston, J., ‘Malaysia: Developmental State Challenged’, in Government and Politics in Southeast Asia, edited by J. Funston, pp. 160-202, London: Zed Books, 2001:175-7.

180Singh, C., 1991. ‘Learning From the Malaysian Experience: A Case Study of the Penang Development Corporation (PDC)’ in Public Enterprise Management: Strategies for Success, pp. 99-116. London: Commonwealth Secretariat, 1989, p.107. Interview with a former Penang Development Corporation Official, Kuala Lumpur, 10/05/2004.

181McKendrick, D.G., Doner, R.F. and Haggard, S., From Silicon Valley to Singapore: Location and Competitive Advantage in the Hard Disk Drive Industry, Stanford: Stanford University Press. 2000, p. 212.

182PDC, Annual Report, Penang: Penang Development Corporation, 1980, p.17. PDC, Annual Report, Penang: Penang Development Corporation, 1981, p.18. PDC, Annual Report, Penang: Penang Development Corporation, 1987, p.17.

183PDC, Annual Report, Penang: Penang Development Corporation, 1988, p.28. PDC, Annual Report, Penang: Penang Development Corporation, 1989, p.29.

184Jomo, K.S., Rasiah, R., Alavi, R. and Gopal, J., 2003. ‘Industrial policy and the emergence of internationally competitive manufacturing fims in Malaysia’. In Manufacturing Competitiveness: How Internationally Competitive National Firms and Industries Developing in East Asia, pp. 106-72. edited by K.S. Jomo and K. Togo, London: Routledge. 2003 p. 116-17.

185Rasiah, R., ‘Government-Business Coordination and Small Enterprise Performance in the Machine Tools Sector in Malaysia’, Small Business Economics, 18(1-3):177-95. 2000, p. 180.

186PDC, Annual Report, Penang: Penang Development Corporation, 1985, p.4.

187PDC. Looking Back, Looking Ahead: 20 Years of Progress, Penang: Penang Development Corporation, 1990, p.51. PSDC, “Penang Skills Development Centre: Meeting Human Resource Development Requirements for Industry in Penang in the 90’s”, Penang: Penang Skills Development Corporation. 1990, p. 26.

188Narayanan, S. and Rasiah, R., ‘Malaysian Electronics: The Changing Prospects for Employment and Restructuring’, Development and Change, 23(4):75-99. 1992, p. 93. Rasiah, R., ‘Systemic coordination and the development of human capital: knowledge flows in Malaysia’s TNC-driven electronics clusters’, Transnational Corporations, 11(3):89-129. 2002, p. 110.

189ISIS/PDC, Penang Strategic Development Plan, Penang: Penang Development Corporation, 1991 p. 1.9,7.19.

190New Straits Times 02/02/1994.

191The Sun 20/02/2003, New Straits Times 07/03/2004.

192New Straits Times 09/12/2000, The Star (12/11/1999.

193Penang State Government website, http://www.penang.net.y/index.cfm, accessed 29/04/2005.

194PDC, Annual Report, Penang: Penang Development Corporation, 2002, p.34. http://www.pdc.com.my, accessed 22/04/2005.

195http://www.pdc.com.my, accessed 22/04/2005. The Star 2/12/2003.

196http://www.rosettanet.org.my, accessed 02/05/2005. PDC, Annual Report, Penang: Penang Development Corporation, 2002, p.5.

197PSDC, Technology Roadmap for the Electrical and Electronics Industry of Penang, Penang: Penang Skills Development Corporation, 2007, pp. 49-52.

198New Straits Times, 9/12/2000. Interviews with industry observers, Penang, 25/02/2004, and Kuala Lumpur, 10/05/2004.

199JICA. “Study on Strengthening Supporting Industries Through Technology Transfer in Malaysia”. Penang: Japanese International Cooperation Agency/Penang Development Corporation. 2001, p. 7.11.

200The Star 16/09/2006, 23/09/2006.

201JICA. “Study on Strengthening Supporting Industries Through Technology Transfer in Malaysia”. Penang: Japanese International Cooperation Agency/Penang Development Corporation. 2001, p. S-2.

202PSDC, Technology Roadmap for the Electrical and Electronics Industry of Penang, Penang: Penang Skills Development Corporation, 2007, pp. 52-55,86-87.

203Rasiah, R., ‘Systemic coordination and the development of human capital: knowledge flows in Malaysia’s TNC-driven electronics clusters’, Transnational Corporations, 11(3):89-129. 2002, p. 105. McKendrick, D.G., Doner, R.F. and Haggard, S. From Silicon Valley to Singapore: Location and Competitive Advantage in the Hard Disk Drive Industry, Stanford: Stanford University Press. 2000, pp. 204-5.

204Ernst D., ‘Global Production Networks in East Asia’s Electronics Industry and Upgrading Perspectives in Malaysia’, In Global Production Networking and Technological Change in East Asia, edited by S. Yusuf, M.A. Altaf and K. Nabeshima pp. 89-158. Washington D.C.: World Bank/Oxford University Press, 2004, p. 136. Far East Economic Review 02/05/2002, The Edge 25/05/2001, The Sun 29/04/2003.