Chapter 6

Industrialization and Poverty in Penang

Muhammad Ikmal Said205

Introduction

Industrialization has transformed Malaysia into an emerging economy that is on its way to becoming a high-income or a developed one. This is a straightforward argument, and the association between industrialization and wealth creation is almost a truism even. Viewed from this perspective, Penang is one of the most industrialized, and economically advanced states in the Malaysian federation. This chapter seeks to look at the journey that Penang undertook to industrialize as part of the larger Malaysian economy, and how this has improved incomes and virtually eliminated poverty in the last 40 years or so.

This journey commenced under Lim Chong Eu’s stewardship of the Gerakan state government after the 1969 elections. One of the objectives of this chapter is to look at how Lim Chong Eu made that transition possible. Another objective of this chapter is to simplify this very complex story by linking Penang’s industrialization with the country’s broader journey to economic development, and to offer an insight into the dynamics of the socio-economic and political choices that were “on the table”.

Part I: The National Context

a. Import-Substituting Industrialization and Growth

Independent Malaya inherited a characteristically colonial export economy, where primary commodity exports, particularly rubber, tin, timber, and iron ore made up a very significant portion of the GDP. In 1960, exports contributed 55 percent of the GDP (Malaysia. 1965:24).206 Thus, the fall in price of rubber and the sluggish growth of other primary commodities for much of the 1960s posed a very serious challenge to the economy.

Diversification of the economy was clearly the way forward. After outlining the challenges and opportunities facing the newly independent nation and the long-term objectives of the country’s development, the First Malaysia Plan that followed the Second Malaya Plan reiterated that the most important resolution was “the need for economic diversification, which includes both agricultural diversification and industrialization” (Malaysia.1965: 15). However, agricultural diversification would have needed a prolonged gestation period. Rubber, the country’s principal smallholder crop, and coconut, were not doing well at all, and there was widespread poverty among cultivators, due mainly to low productivity and prolonged decline of prices for much of the 1960s and the mid-1970s. On the other hand, the general level of prices had increased considerably, threatening smallholders with a “reproduction squeeze”, that is, the inability to earn enough to continue producing on the same scale.

Instead, the key strategic transformation agenda was to increase investment in import-substituting industrialization, or ISI for short. The country’s GDP per capita was relatively high internationally, at $731 in 1960, and per capita consumption grew 2.8 percent annually from 1960 to 1965, assuring, it was argued, a very positive purchasing power trajectory. Since a large proportion of consumption was serviced by imports,207 it made sense for the state, particularly under conditions of weaker export revenue potential,208 to induce growth while simultaneously saving the country’s foreign exchange through import-substituting industrialization.

To this end, tax incentives, import duties and quotas were provided under the Pioneer Industries (Relief from Income Tax) Ordinance (PIO) of 1958, followed by the Investment Incentives Act in 1963, 1966 and 1968.209 The Malaysian Industrial Development Finance Corporation was also established during this time, providing investment capital for the development of industrial estates. With these incentives in place, the weighted average effective rate of protection was said to have risen to 65 percent by the end of the decade (Kanuthia.2009:8).

The ISI policy yielded encouraging gains in the ten-year period covering the Second Malaya Plan and the First Malaysia Plan from 1960 to 1970. Net manufacturing output grew at 9.9 percent annually in the 1960-1965 period and 10.4 percent between 1966 and 1970, raising the share of manufacturing to the country’s GDP from 8.5 percent in 1960 to 10.4 percent in 1966 and 13 percent in 1970 (Malaysia, 1971:15). These were mainly in foodstuffs, beverages, tobacco products, petroleum products, cement, rubber and plastic goods, fertilizers, textiles and steel bars.

The largely foreign firms that took advantage of the ISI provisions were capital intensive, and were, therefore, incapable of generating enough jobs to cater to the country’s rapid population growth. In addition, the domestic market was relatively small. Consequently, many of the firms that enjoyed protection behind the tariff walls very quickly became inefficient. By 1970, “the ISI policy had led to average consumer prices in Malaysia to rise above 25 percent of world market prices…” (Kanuthia.2009:7).210

b. Export-led Industrialization and Growth

Although the emphasis on import-substituting industrialization increased the manufacturing sector’s output and share of Malaysia’s GDP, it failed to fulfil the key justifications for its introduction, and was soon supplanted with an industrialization policy that laid increasing emphasis on export-oriented manufacturing.

As noted earlier, the emphasis on ISI under the First Malaysia Plan was an interim plan triggered by weakening exports. Indeed, the First Malaysia Plan – the first phase of a 20-year Perspective Plan – clearly recognized the strategic importance for an export strategy:

“During the next five years, although attempts will be made wherever possible to promote the growth of exports, efforts to solve the problem will probably have to rely mainly on import substitution. Over a longer span of time large-scale development of new exports will emerge as a second feasible strategy” (Malaysia.1966:16, emphasis added).

The First Malaysia Plan speculated that the generation of “new exports” could be spearheaded by the import-substituting industries. However, as revealed by the Second Malaysia Plan subsequently, domestic demand was not large nor strong enough to meet the ambitious New Economic Policy (NEP) targets to address pressing social and economic inequalities that had precipitated the ethnic riots of 13 May 1969. Instead, manufacturing exports, through increased foreign investment, would have to play a crucial role (Malaysia 1971:152, 156) under the Second Malaysia Plan and beyond, particularly to provide much-needed employment opportunities to alleviate widespread poverty and to break down the ethnic division of labour, the two key objectives of the NEP. The new exports would be based on labour intensive industries, which were struggling with rising wages in their respective countries.

Following these changes, the manufacturing sector expanded very rapidly. Between 1970 and 1980, it grew at an average of 12.5 percent annually, and accounted for 26.8 percent of GDP growth. As a result, its share of the country’s GDP rose to 20.5 percent in 1980, from 12.2 percent in 1970 (Malaysia.1981:18).211 The manufacturing sector continued to grow further, raising its share of GDP to 27.0 and 33.1 percent in 1990 and 1995 respectively, before declining in the face of the Asian financial crisis in 1997-98.

The doubling of the share of manufactured exports to total exports to 23 percent in 1975 from 11.4 percent in 1970, underscores the significant shift of emphasis of policy to export-oriented industrialization. The share of manufactured to total exports increased further to 25.2 percent in 1980, 58.8 percent in 1990 and 79.6 percent in 1995.

The surge in manufactured exports was propelled considerably by the electrical and electronics sector, whose share of total exports rose from 2.1 per cent in 1973212 to 37.4 percent in 1980. As testimony to this remarkable growth, Malaysia emerged as the largest exporter of electronics components among developing countries, and was also ranked among the world’s major exporters in 1980 (Karunaratne and Abdullah.1978). The electrical and electronics industry went on to increase its share of manufactured exports to 52.1 percent in 1985, 65.7 percent in 1995 and 72.5 percent in 2000 (Rasiah, R.2010:304).

The rapid growth of industrialization was not an uninterrupted, secular course. The first serious challenge came with the global cyclical downturn in 1979-1982, which emerged again in 1985-1986. As a result, the manufacturing sector experienced slower growth of 4.9 percent over the 1981-1985 period, when compared to 12.5 percent in 1976-1980, and its share of GDP in 1985 declined to 19.1 percent, from 20.0 percent in 1980 (Malaysia.1986:49). The extended drag on the economy over this period saw a 66 percent drop in manufacturing value added and an 18 percent drop in employment between 1981 and 1985.

The severity of the impact of the global slowdown was exacerbated by a shift in policy in 1981 to develop heavy industries, with active state participation.213 With this change in policy, foreign direct inflows, already curtailed by the recession, slowed down further214 Meanwhile, the heavily subsidized heavy industries suffered considerable losses and could not be relied upon to drive manufacturing growth. Since manufacturing growth was critical to meeting the objectives of the NEP, a quick return to another round of export-oriented manufacturing ensued.

The second round of export oriented industrialization brought back strong growth in manufacturing. Between 1986 and 1990, the average annual growth of the manufacturing sector rose to 13.9 percent, while its share of total exports rose from 58.8 percent in 1990 and 85.2 percent in 2000, up from 32.8 percent in 1985.215 Its contribution to GDP rose from 27.0 percent in 1990 to 33.1 percent in 1995, and remained at that level until 2010.

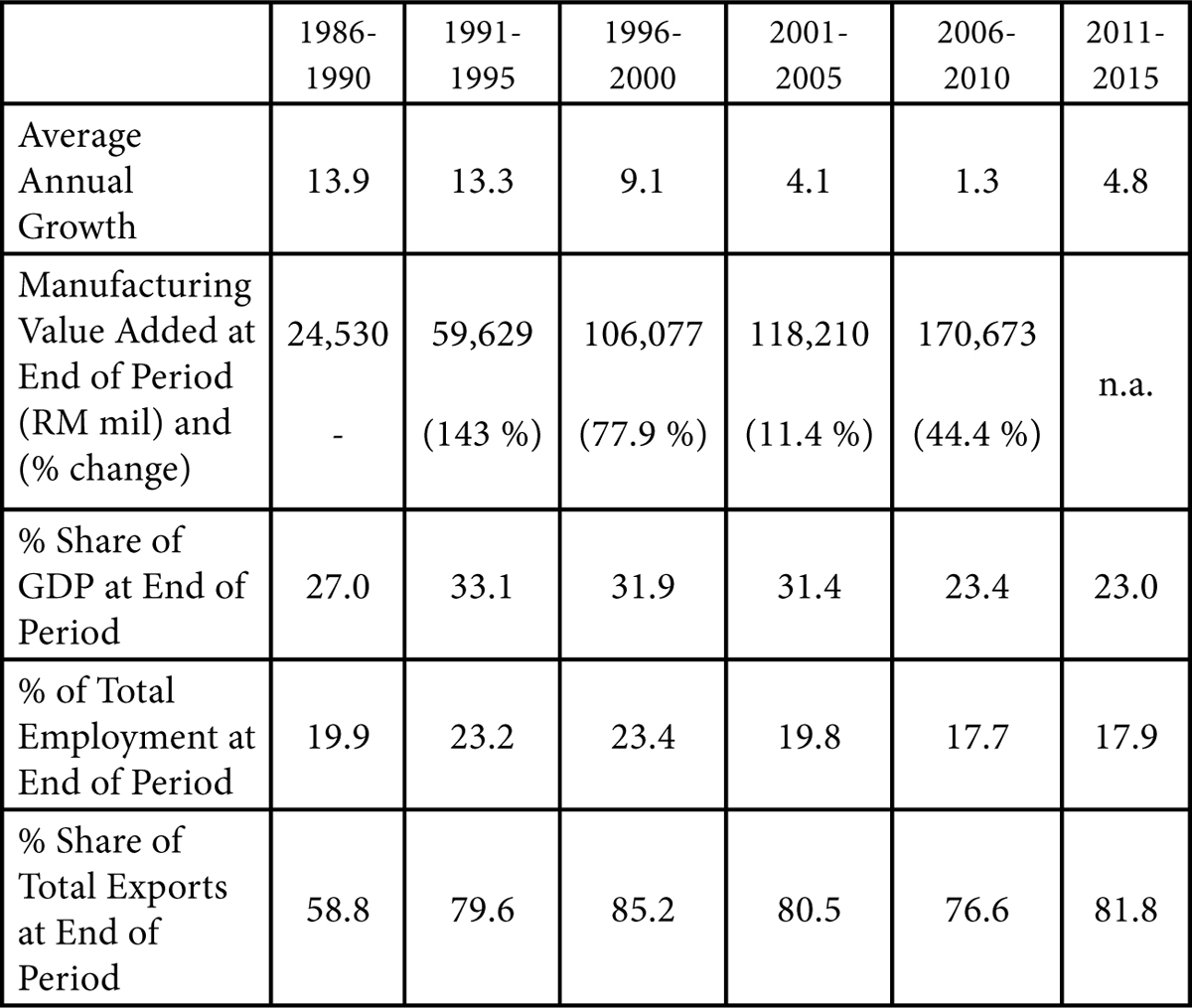

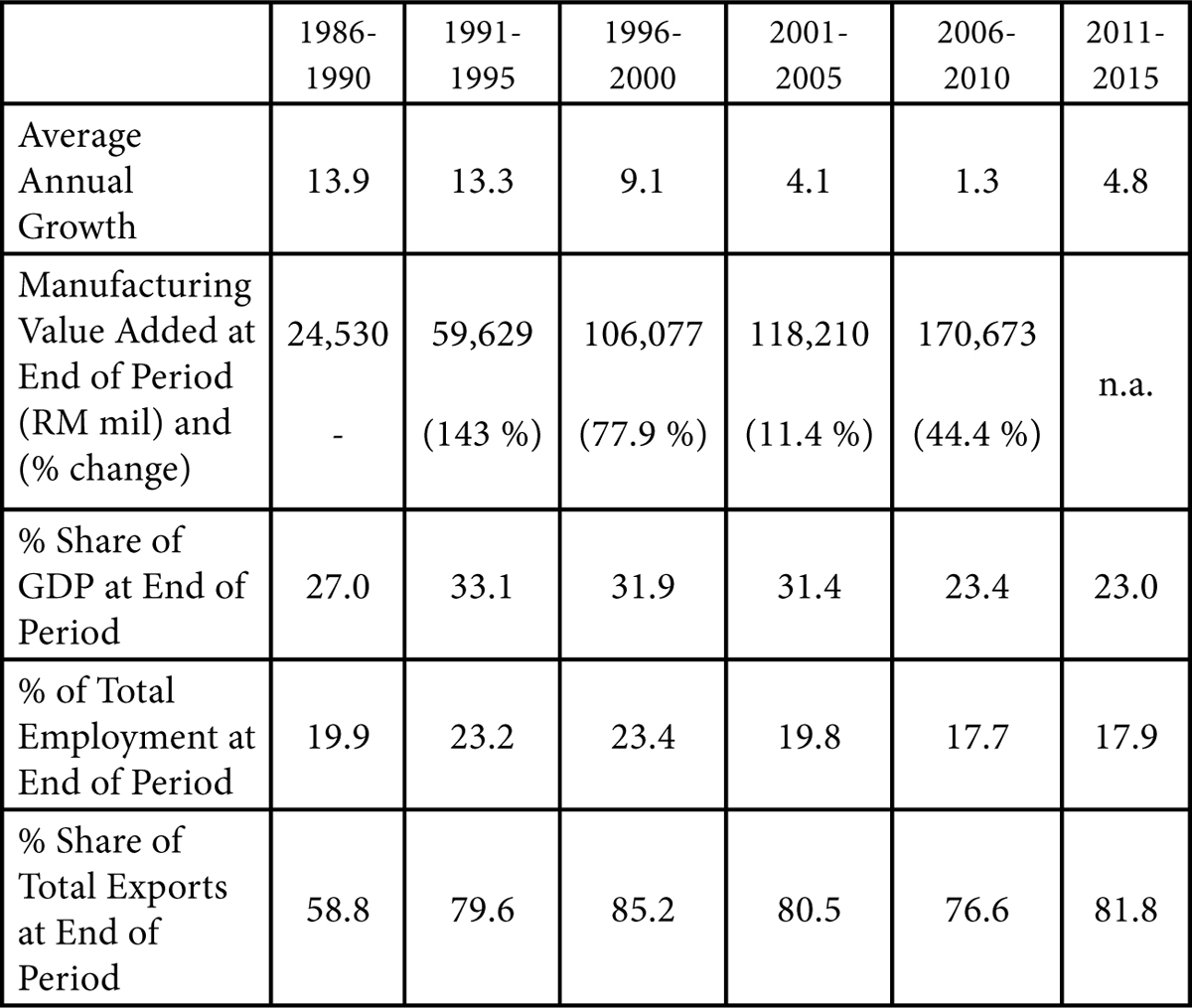

However, the rapid recovery of the manufacturing sector in 1986-1990 could not be sustained. As is evident from Table 6.1, the average annual growth of the manufacturing sector declined to 13.3 percent in 1991-1995 and to 9.1 percent for the 1996-2000 period. Indeed, the manufacturing sector continued to see slower growth, with average annual growth declining further to 4.1 percent in 2001-2005, and 1.3 percent in 2006-2010, but recovered to record a 4.8 percent growth in 2011-2015. The percentage increase of manufacturing value added has also shown a perceptible decline.

Similarly, the manufacturing sector’s share of GDP also declined from 33.1 percent in 1995 to 23.0 percent in 2015, while its share of total employment dropped from 23.4 percent in 2000 to 17.9 percent in 2015. However, despite the declining annual growth rate or declining contribution of the manufacturing sector to the economy as a whole, manufacturing exports have continued to account for a lion’s share of total exports.

Table 6.1: Trends in the Manufacturing Sector

Thus, there appears to be a “stalling” in the growth of the manufacturing industry. Henderson (2013) attributes this to the affirmative action programmes of the New Economic Policy that were implemented from 1971 by the UMNO-led Barisan Nasional government. Essentially, the massive income transfers that benefit the Bumiputera communities under the New Economic Policy (1971-1990), and newer versions of the same, had stultified investment by private, especially local, capital.

c. Import Substitution, Employment and Poverty and Inequality

The economic situation in the years leading up to 1970 was, on the whole, positive. The export of goods and services grew, on average, by 5.5 percent annually and per capita real income increased by 12 percent. Domestic demand and total investment grew by slightly more than six percent annually, while GDP grew by 5.5 percent annually. Yet, the country had only just come out of a prolonged decline in rubber prices for the greater part of the 1960s.

In 1965, agriculture accounted for 52 percent of total employment (Malaysia, 1966:81). Skill levels were low since the bulk of the work force had little education, more so among the rural population. The predominantly rural Malay population had poor access to schools, with only 44 percent in the 6-12 age cohort attending schools in 1950. This was compounded further by the fact that a great majority of the children who enrolled in Malay primary schools could not proceed to secondary schools, since there were not many Malay secondary schools back then (Abdul Rahman and Sharifah Zarina, 2011). For the country as a whole, only 30 percent of children who completed primary education proceeded to secondary schools (Malaysia.1966:167). Thus, by and large, the labour force was not sufficiently educated in the 1960s.

Throughout the 1960-1970 decade, population growth outpaced employment growth. Consequently, unemployment increased from six percent in 1960 to 6.5 percent in 1965 and eight percent in 1970 (Malaysia. 1971:17-18).216

Poverty was widespread in both urban (21 percent) and rural areas (59 percent). These conditions, together with increasing out-migration of lowly-educated rural Malays into Peninsular Malaysia’s towns, and heightened tensions over perceived erosion of Malay political influence arising from the general elections of 11 May 1969, led to the ethnic riots on 13 May.217

The bulk of foreign investments that came with the country’s import-substituting industrialization drive was capital-intensive. Capital goods imports in the 1960s not only grew rapidly but was also at a rate faster than growth in total investment (Malaysia. 1971:30). The much larger growth in output than in employment in the manufacturing sector corroborates further the high capital intensity of that sector (Osman, 2010:263). Only four percent of manufacturing establishments had 50 or more employees. Yet, these same group of companies accounted for 60 percent of total net manufacturing output (Malaysia.1966:124). Thus, capital-intensive import substituting manufacturing was totally out of sync with the prevailing conditions of high unemployment.

A closer look at the unemployment situation gives us a sense of the scale of the problem, and what this meant to poverty reduction. Between 1965 and 1970, the unemployment rate for men over 25 years was only three percent. It was instead among youth between 15 and 25 years old where the great bulk of unemployment was found, in no small measure due to a tripling in their number between 1955 and 1965 (Hirschman,1980:109-110). It was estimated that 75 percent of those who were unemployed in 1967 was from this age group. (Malaysia, 1971:99).

With insufficient opportunities for employment, the great majority of youth in the 15-25 age category, especially those between 15-19 years who, because of poverty, had poor access to schools, completed schooling prematurely with no skills. It was reported that unemployment among the 15-19 years age group was as high as 16 percent (Malaysia.1966:79). Unemployment among this age-group in the urban areas, which hosted rapidly increasing numbers of migrants from the countryside, was at an alarmingly high of 27 percent. The comparable unemployment rate for the same age-group in the rural areas rate was 14 percent. Although this was much better than the situation for urban youth, there was, nonetheless, a relatively high incidence of underemployment among the rural population.218

There was a long queue to employment for unskilled school leavers, as 30 percent remained unemployed for more than a year and another 30 per cent never had a job. Yet jobs, though not growing fast enough to keep pace with the swelling labour force, were aplenty then. About 30 percent of the jobs in the private sector which required post-secondary education remained unfilled, or were taken up by non-Malaysians. Even the take-up of jobs in government service was low, with about 30 percent unfilled (Malaysia.1966:79).

About 792,000 of the 1.6 milion households in West Malaysia, or almost one half (49.3 percent) of the population, was poor in 1970. Unsurprisingly, the great bulk of poverty was found among the rural population, accounting for 86 percent of poor households in 1970. It is also evident from Table 2, that rural poverty, due to its sensitivity to rural commodity prices, seemed more persistent than urban poverty. Between 1957 and 1970, rural poverty declined by a mere one percent.219 By contrast, urban poverty declined from 30 percent in 1957 to 21 percent in 1970..

The Malays, who formed the bulk of the rural population attending to small-scale paddy, rubber and coconut smallholdings, were the poorest lot, with 71 percent considered poor in 1957. By contrast, 27 percent of Chinese and 36 percent of Indian rural households were poor.

Rural smallholders were generally on the fringe of the colonial project, and were often left to themselves to fend not only against the clutches of gatekeepers of a highly fragmented and underdeveloped market in the countryside but also against the interests of the commodity export lobby. Under these circumstances, small-scale agriculture was burdened with high interest rates and low prices,220 which skimmed surpluses from the peasantry into the coffers of market mediators that had little interest investing in production. Expectedly, productivity remained low and poverty was rife.

It will be noticed in Table 6.2 below that while poverty declined among rural Malay households, it increased for Chinese and Indian households. The changing fortunes of the Malay peasantry can be traced to the changing role of the state. This change came in the wake of increasing dissatisfaction in the countryside, which was reflected in significant shifts of support for the opposition Islamic party PMIP in the less developed, and predominantly Malay states of Kedah, Perlis, Kelantan and Terengganu in the 1959 and 1964 general elections (Rudner.1983). These shifts directly threatened UMNO’s power base, and its leadership of the Alliance government. In response, UMNO, with the MCA and MIC in tow, steered the state to transfer considerably larger resources for the development of the predominantly Malay peasantry. This is clearly reflected in the very large increase in the allocation of public expenditure made in favour of agriculture and rural development, which rose from RM475.6 million under the under Second Malaya Plan (1961-1965) to RM1,086 million under the First Malaysia Plan (1966-1970). As a result, the share of agriculture and rural development to total public development expenditure rose from 15.3 percent and a 23.9 percent respectively.

Table 6.2: Incidence of Poverty in West Malaysia, 1957-1970

|

1957/58 |

1970 |

All Households |

51.2 |

49.3 |

Rural households |

59.6 |

58.7 |

Urban households |

29.7 |

21.3 |

|

||

Malay |

|

|

All households |

70.5 |

65.9 |

Rural households |

74.9 |

70.3 |

Urban households |

32.7 |

38.8 |

|

||

Chinese |

|

|

All households |

27.4 |

27.5 |

Rural households |

29.4 |

30.5 |

Urban households |

25.2 |

24.6 |

|

||

Indian |

|

|

All households |

35.7 |

40.2 |

Rural households |

31.5 |

44.9 |

Urban households |

44.8 |

31.8 |

Source: Ikemoto (1985:358)

Poverty increased only slightly among rural Chinese, but increased considerably among Indian communities in the same period. The rural Indian communities were largely concentrated in the rubber plantation sector, where they formed the bulk of the labouring class. A large number of Indian labourers either lost their jobs or endured declining wages when economically marginal, mainly British-owned, rubber plantations were subdivided and sold off to Asian owners in the 1950s and 1960s,221 or were replanted with oil palm, where less labour was required. It was estimated that nearly one-fifth of the predominantly Indian plantation work force became redundant as a result of the subdivision of estates (Malaysia.1971:17).

On the other hand, poverty among urban Malay households increased, but declined among Chinese and Indian urban households. This came in the wake of an unprecedented wave of migration of unskilled Malays from the countryside into urban centres, where shanty settlements or slums became a growing part of the landscape.

The primary objective of the import-substituting industrialization policy was to generate economic growth at a time when the country’s two key export earners, rubber and tin, were facing serious price and low-reserve issues, and not to directly address unemployment of the large reserve of unskilled labour. In the absence of a sufficiently established local industrialist class, the post-colonial state was dependent on foreign capital to shape the form and to set the pace for its import-substituting industrialization policy. As it turned out, these firms were very largely capital-intensive rather than labour-intensive. Thus, although the Alliance government had a tighter rein over the post-colonial state as soon as UMNO lost voters in the northern states of peninsular Malaysia to the opposition PMIP, it was not strong enough to transfer resources away from sectors preferred by colonial and foreign capital.

d. Export-Oriented Industrialization and Poverty and Inequality

Despite the declining fortunes of the rubber sector, the economic situation in the years leading up to 1970 was, on the whole, positive. The export of goods and services grew, on average, by 5.5 percent annually and per capita real income increased by 12 percent. Domestic demand and total investment grew by slightly more than six percent annually, while GDP grew by 5.5 percent annually. And this was at a time when the country had only just come out of a prolonged decline in rubber prices.

However, unemployment was high, reaching eight percent in 1970, while poverty was widespread, affecting one-half of the population, certainly more if data was available for Sabah and Sarawak then. Based on estimates of the population in Peninsular Malaysia, 21 percent of the urban population and 59 percent of the rural population were poor that year. As could be expected, the great bulk of the poor – 79 percent – was made up of rural households. These conditions, together with increasing out-migration of lowly-educated rural Malays into Peninsular Malaysia’s towns and heightened tensions of perceived erosion of Malay political influence arising from the general elections of 11 May 1969, led to an outburst of ethnic riots on 13 May.222

Following the 1969 riots, the state embarked on a gargantuan initiative to eliminate poverty and “the identification of race with economic function”.223 These two basic objectives of the New Economic Policy involved “raising income levels and employment opportunities for all Malaysians, irrespective of race” and “the modernization of rural life, a rapid and balanced growth of urban activities and the creation of a Malay commercial and industrial community in all categories and at all levels of operation so that Malays and other indigenous people will become full partners in all aspects of economic life of the nation” (Malaysia:1971:1).

So, how has Malaysia fared with poverty and inequality since 1970?

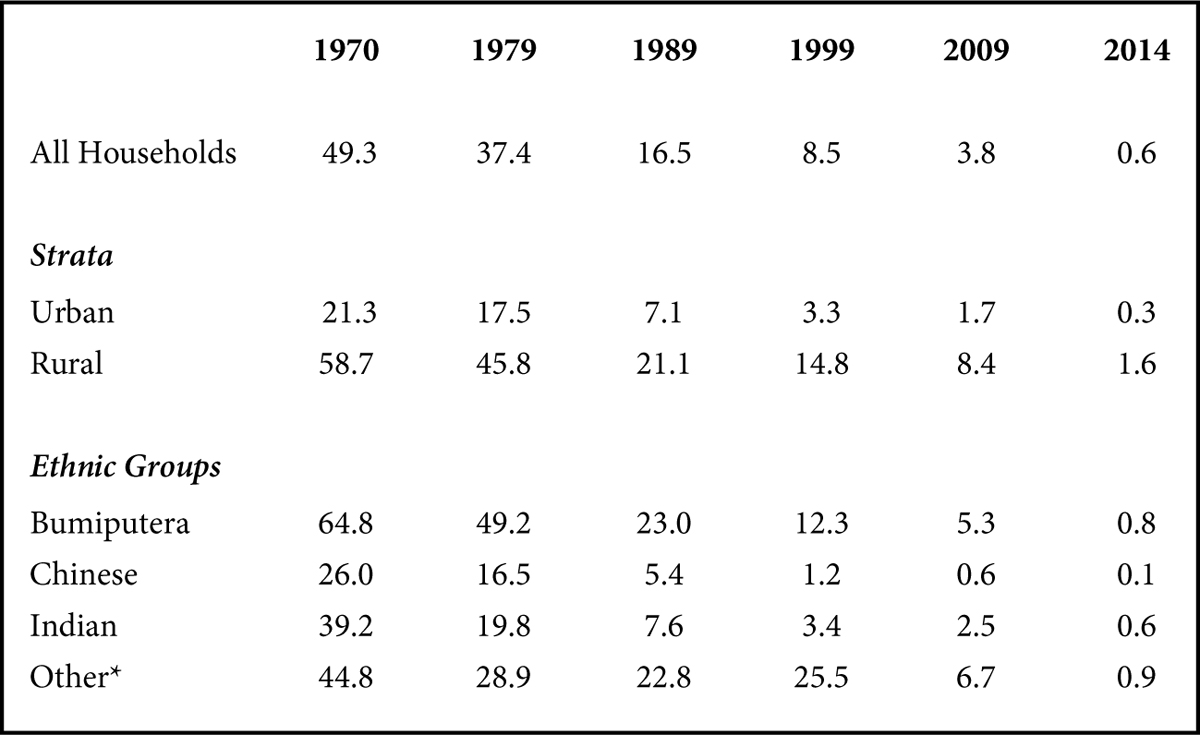

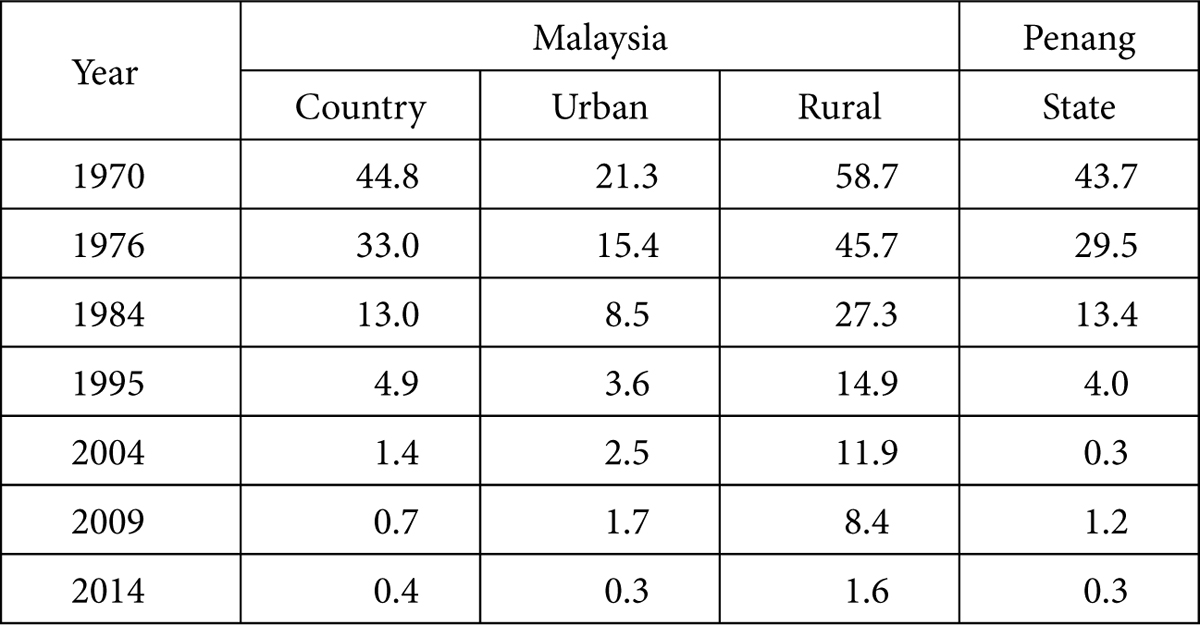

First, as Table 6.3 shows, poverty declined considerably over the next 40 years, from about 50 percent of all households in 1970 to only 0.6 percent in 2014. Poverty among the urban population is limited to 0.3 percent of households, down from 21.3 percent in 1970. The reduction of poverty among rural households has been no less impressive, as only 1.6 percent remains in poverty, compared to 58.7 percent in 1970.

Table 6.3: Incidence of Poverty in West Malaysia, 1970 - 2014

*The “Other” residual group is a very small minority, accounting for a mere one about percent of the population in 2016 (Malaysia, 2018) and for much of the four decades between 1970 and 2010. Due to its small size, this group’s relative standing will not be subject to analysis.

Source: “Time Series of Income and Poverty Statistics, 1979-2009”, Table 6. Department of Statistics, Malaysia. Findings of Household Income Survey (HIS) 2012

Second, it is observed that throughout the four decades, poverty was lowest among Chinese households, and highest among Bumiputera households, while the incidence of poverty among Indians stood somewhere in between the first two groups. Although the three principal ethnic groups reported considerably contrasting incidences of poverty in 1970, more than 99 percent of members of all ethnic groups today enjoy incomes that are above the poverty line.224

Third, the Bumiputera community achieved the largest movement out of poverty in the last 40 years. Starting out with 65 percent of households living in poverty in 1970, less than one percent of the Bumiputera community remains poor today. The progress achieved by the Chinese and Indian ethnic groups was also very substantial. The Chinese community is virtually free of poverty, with only 0.1 percent living under the poverty line in 2014, compared to 26 percent in 1970. At the same time, poverty among Indian households declined from 39.2 percent in 1970 to 0.6 percent in 2014.

Fourth, poverty, continued to be a more serious problem among rural than urban households. In 1970, 59 percent of rural households were poor compared to 21 percent of urban households. By 2014, rural poverty was limited to only 1.6 percent of rural households, and 0.3 percent of urban households remain poor.

Finally, it should be observed that the decline in poverty reflected changes in the economy. The decline in poverty is tied, to a very large degree, to the vagaries of global economic trends. For example, the steady decline in poverty from 16.5 percent in 1989 to 12.4, 8.7, and 6.1 percent in 1992, 1995 and 1997 respectively was interrupted by the rapid contraction of the economy following the Asian financial crisis in 1997-98. We witnessed a similar experience in the 1999-2009 decade. Due mainly to the Asian financial crisis, 8.5 percent of households were poor in 1999. The situation improved as the economy got better.

Poverty subsequently declined to 6.0, 5.7 and 3.6 percent in 2002, 2004 and 2007 respectively, but rose slightly to 3.8 percent in 2009 when the economy fell into negative growth territory with the global financial crisis in 2009. Over the long run, however, the falling trend in poverty is unmistakable.

Part II:

a. Decline of Penang’s Entreport Trade in Post-Colonial Southeast Asia

Penang flourished on entreport trade throughout the colonial era, with strong links with neighbouring states such as Kedah, Perlis and Perak, Southern Thailand, Burma, and Indonesia. It had all the signs of a thriving economy comparable to Hong Kong and Singapore, when Malaya attained independence in 1957.

Independence speeded up the political and economic integration of Malaya, and of other neighbouring countries as well. One clear expression of this was the centralization of the post-colonial state, as the governing elites went about to consolidate the development of their respective “national” economies. The rapid development of Kuala Lumpur as the administrative and commercial centre, and the Klang Valley as the country’s leading industrial corridor, was one clear expression of the new geography of state power in Malaya. Consequently, the Klang Valley assumed a larger share of the country’s trade, enormously benefiting Port Swettenham, renamed Port Klang, at the expense of “outlying” ports such as Penang.225 In much the same way, local ports in Burma, Thailand and Indonesia grew in importance with the development of their respective national economies, diminishing Penang’s entreport trade.226 As a result, the post-colonial regional geography assigned Penang to a considerably reduced role.

As part of its efforts at defining the course of development of the post-colonial economy, Kuala Lumpur experimented with import-substituting industrialization, on the advice of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development. Import-substituting industrialization was touted as the panacea that could at once arrest the country’s dependence on diminishing export revenues from a few primary commodities on the one hand, and reduce the country’s bloating import bill on the other. Import-substituting industrialization became the new “national” mantra under which Penang was to chart its future, but which had not gathered enough momentum from local and foreign capital to fire the required blast for sustained growth.

The Prai Industrial Estate, established in 1964, grew out of this new policy. However, within a few years, many of the industries there failed.

Responding to comments regarding the threat of the Malaysian common market to Penang’s entreport trade and industrialization, an official of the Federal Treasury offered a blunt but unclear assessment of the uneasy relationship between import-substituting industrialization on the one hand, and “free trade” under the old international division of labour, on the other. In the same breadth, the officer offered an uncanny gaze of “free trade zones for entreport trade”, viewed by the Customs Department then as a “back door” attempt to perpetuate Penang’s free port status and hold on the old international division of labour:

“I should point out, in reply to these observations, that no reason is seen why the entreport trade of Penang Island cannot be catered for, in the context of a Malaysian common market, by the provision of special facilities in that island by the establishment of free trade zones for entrepot trade…As regards industry in Penang Island, it has been pointed out before that it is apparent that industrialisation is most unlikely to take place while Penang Island is outside the principal Customs area or the Malaysian common market, as manufacturers would then have to compete without any protection with low-priced imports from other countries”.227

The “free trade zones for entreport trade” was not in any of the federal government’s plans, whereas industrial free trade zones were still a long way away from reality. With no new economic stimulus to drive growth, Penang’s economy took a turn for the worse. By the end of the 1960s Penang’s per capita income was 12 percent lower than the national average, unemployment had risen to nine percent, whereas underemployment reached seven percent (Athukorala, 2012), and the incidence of poverty had climbed to 43.7 percent by 1970

Penang had another problem. It had grown into an “outlying port” in another sense. For much of the first decade after independence, Penang became the hub of left-wing politics. In the first City Council of George Town elections in 1951, the Penang Radical Party, led by Lim Chong Eu, took the lion’s share of the nine elected seats.228 Subsequently, the City Council came under the successful control of the Labour Party until local council elections were suspended in 1965.

Thus, the Alliance coalition government had its hands full containing a very well-managed, financially independent, but ideologically committed Labour Party, as a result of which the state government often had to deal with strikes, demonstrations and even riots.

With no new way forward under the MCA-led Alliance state government, and the Labour Party drawing a hard line to boycott the 1969 general elections, the newly established Parti Gerakan Rakyat Malaysia, or Gerakan for short, swept into power and Lim Chong Eu, its seasoned leader, was made Chief Minister.

b. Arresting the Slide

Thus, Lim Chong Eu was up against a daunting challenge. For he needed to set a new developmental course that would not only wean Penang’s trading community off the entreport trade but also simultaneously absorb excess labour sustainably. He was to lead a newly elected, predominantly Chinese-based but multi-ethnic opposition party that had unseated the incumbent Alliance government – still in the driving seat in Kuala Lumpur - in a territorially small Chinese-majority state that needed to deal with an UMNO that had failed to improve the lot of the Malays. Tunku Abdul Rahman, whose laissez-faire leadership won the favour of the predominantly Chinese business community and urban middle classes, was put under great pressure by a very restive Malay population.229

The unrestrained jubilation over the electoral gains, particularly in Selangor, generated the sparks that lit the May 13 1969 racial inferno. The post-May 13 1969 reconstruction, particularly under 18 months of emergency rule, saw close cooperation between Lim Chong Eu and UMNO’s two key leaders, Abdul Razak Hussein and Ismail Abdul Rahman. Consequently, an understanding was struck between the Gerakan state government in Penang and the federal Alliance government in Kuala Lumpur to enable the new state government to address the pressing economic issues of the state at one level and of the country at another. The confidence and trust that developed between the three leaders encouraged Lim Chong Eu to lead the Gerakan Party in 1973 into the broadened ruling governing coalition, called the Barisan Nasional.230

Recognizing Penang’s declining economy, the federal government commissioned Messrs R. Robert Nathan and Associates in 1969 to outline a new growth strategy for Penang. The “Nathan Report”, better known as the Penang Master Plan Study (PMPS), recommended for a two-pronged initiative to power Penang’s turn to sustained growth, visibly through the development of an export-led manufacturing industry on the one hand and tourism on the other.

Lim Chong Eu embraced the key recommendations of the PMPS, and concluded that to step out of the economic quagmire, Penang must nurture a labour-intensive export-led manufacturing industry231 that could simultaneously support the development of the tourism industry, and shrewdly determined that the electronics industry would serve the employment situation in Penang well.232 The Penang Development Corporation (PDC), a statutory body, established in 1969 with the responsibility for planning, implementing and monitoring development in the state, swiftly got down to playing its role.233

The timing could not have been better. A new international division of labour was already taking shape as manufacturers in the United States, Europe and Japan, were faced with rising labour costs in an increasingly competitive global market. One important way forward was to seek alternative off-shore sites in less developed economies, where labour was not only abundant and cheap but also where governments, in their desire to attract foreign direct investments under the very real threat of losing out to countries competing for the same with even more generous incentives, were prepared to forge labour regimes that were pliant to the interests of foreign investors.234 Some of these multinational corporations were already in the region, mainly in South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Singapore, and had begun to explore alternative sites in the region, such as Penang, where labour costs were cheaper.

Guided by the Nathan Report, the state government and PDC, sometimes with the assistance of the Malaysian Industrial Development Authority (MIDA), made concerted promotional efforts to attract multinational corporations to invest in Penang. Lim Chong Eu provided the leadership that enabled the PDC to steer through the many layers of state and federal bureaucracies, no doubt hastened by the heightened pressure borne upon the state- and the federal governments to urgently address the gaping ethnic fault lines exposed by the May 13 riots and by the subsequent suspension of Parliament until February 1971, to develop the necessary eco-system, and on occasion, establish new laws at the federal level, such as the Free Trade Zone Act 1971.235 The availability of a large pool of cheap but fettered labour was, of course, a critical part of Malaysia’s attractive package,236 enhanced further in Penang by the enthusiastic welcome of a new state government that was very ably supported by a dynamic and creative managerial team.

c. Industrialization and Growth

The Bayan Lepas Free Trade Zone (FTZ, renamed Free Industrial Zone, or FIZ, in 1990) was opened in 1972 with eight companies in its first year. Today it has expanded to include four phases, with more than 90 percent of the RM14.6 billion invested there originating from companies in the electronics and electrical goods sector (Yeo and Ooi, 2009). Another two FIZs were established in Prai and Prai Wharf on the mainland. The island and the mainland are today connected by two bridges, thus providing easy access to airport facilities on the island and seaport facilities on the mainland.

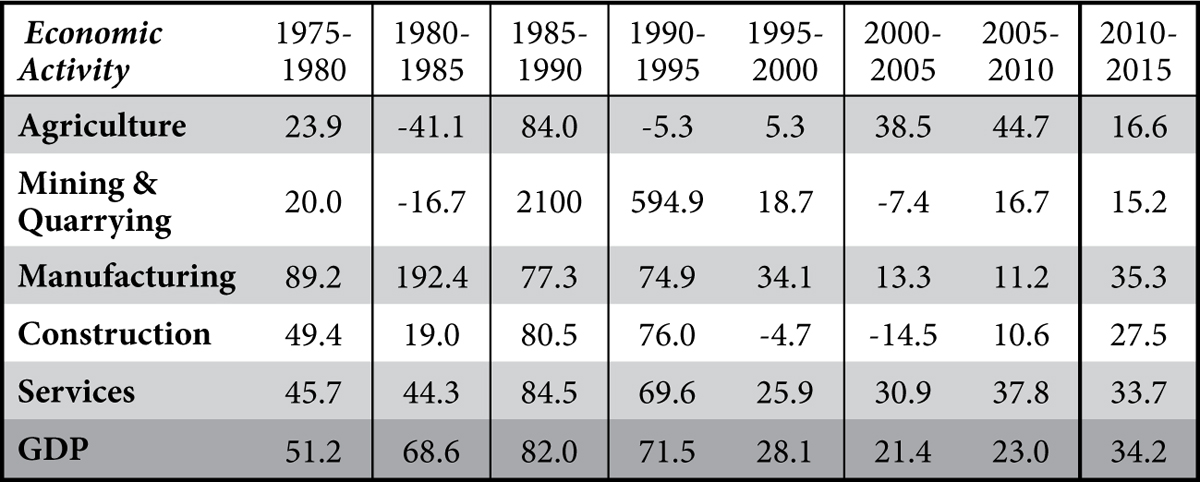

Penang’s industrial sector grew at a scorching pace from the early 1970s to the mid-1990s, but slowed down subsequently, especially between 2000 and 2010. As is shown in Table 6.4 below, the manufacturing sector grew by about 89 percent between 1975 and 1980, or at an average annual growth rate of 18 percent, but which more than doubled at 38 percent annually between 1980 and 1985, and roughly 15 percent annually in each the subsequent five-year periods between 1985-1990 and 1990-1995. The rapid growth of the manufacturing sector, along with the steady growth of the services sector in the last 40 years, has greatly contributed to the expansion of the state’s economy.

Table 6.4: Penang GDP Growth Rate (%), 1975-2015, Penang

Undoubtedly, a significant share of the growth recorded in the services sector may be traced to linkages with the manufacturing industry, including logistics, marketing and sales, R & D, and design, especially after 1990, when the federal government decided on a new policy to develop industry linkages in the free industrial zones. Initially, the sought-for linkages were targeted at resource-based industries such as palm oil and furniture, which were also more largely owned by local capital. Subsequently, the incentives were broadened to apply to other industries when new realities emerged.

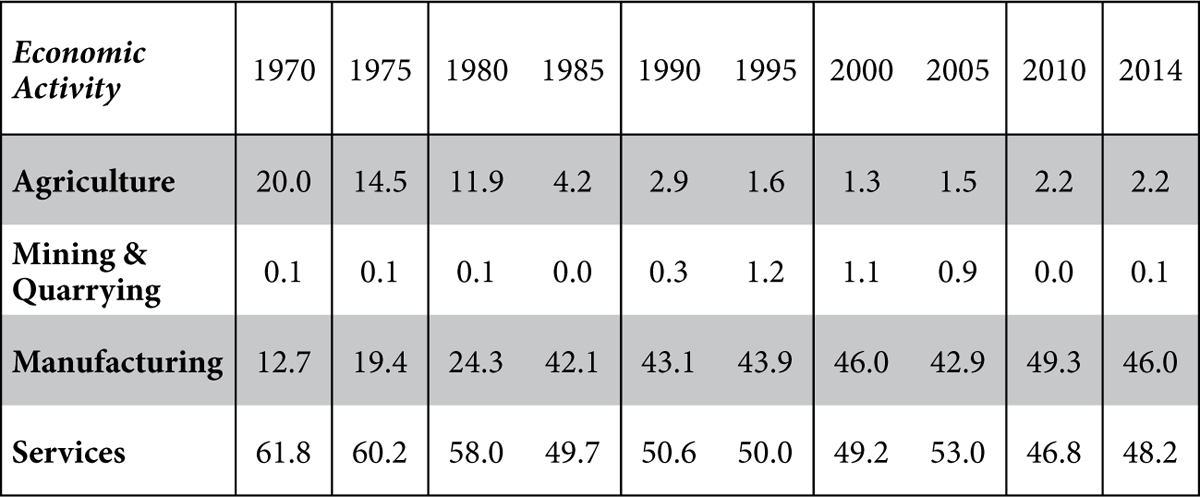

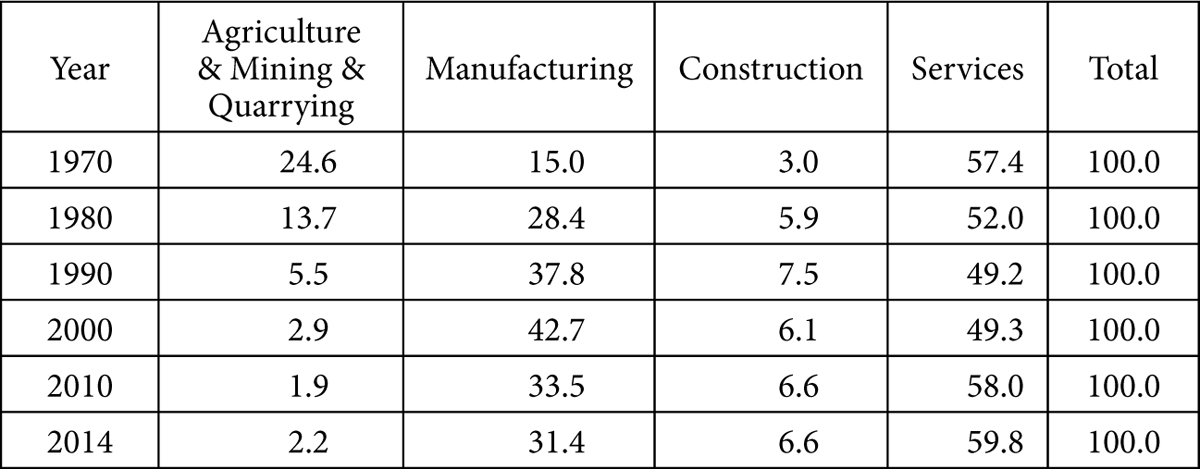

The very rapid growth of the manufacturing sector between 1980 and 1985 raised its share of the state’s GDP to 42 percent in 1985, and has since increased moderately to 46 percent by 2014 (see Table 6.5 below). On the other hand, the share of the services sector in Penang’s economy declined from 62 percent in 1970 to 50 percent in 1985, and 48 percent in 2014.

Table 6.5: Economic Structure (% Share in GDP) of Penang

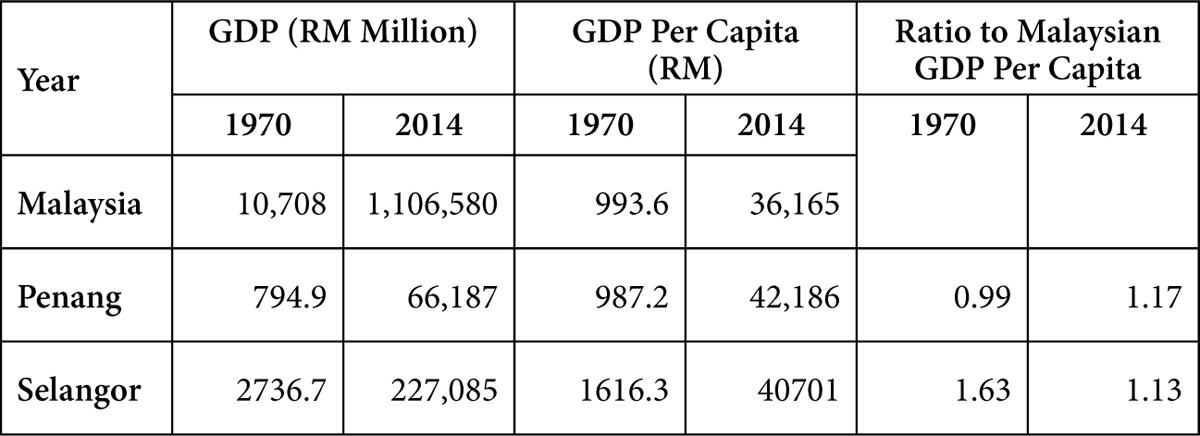

Since 1985, the manufacturing and service sectors together account for more than 90 percent of Penang’s economy. With this very rapid but successful turn away from dependence on entreport trade, the state’s GDP rose from RM800 million in 1970 to more than RM66 billion in 2014, raising the state’s GDP per capita from RM987 to RM42, 186 during the same period, surpassing the country’s GDP per capita of RM36,165 and even that of Selangor’s (RM40,701).

In 1970, Penang’s GDP per capita was slightly lower (0.99 times) than the country’s average, and was much lower in rank order, then topped by Selangor, whose GDP per capita, as Table 6 shows, was 1.63 times larger than the country’s average. However, Selangor’s GDP per capita declined gradually over the next four decades. By 2014, the ratio of Selangor’s GDP per capita to the Malaysian GDP per capita had declined to 1.13, whereas Penang’s had risen to 1.17. Thus, Penang’s growth has not only been very rapid, but also surpassed other states, including Selangor.

Table 6.6: Selected GDP Per Capita, 1970-2014

As it would have been noticed in Table 6.4, the average annual growth of the manufacturing sector slowed down considerably to 6.8 percent annually between 1995 and 2000, from 15 percent in the 1990-1995) period. Subsequently, manufacturing growth, to borrow Henderson’s (2013) term, “stalled” at 2.6 and 2.2 percent annual growth between 2000-2005 and 2005-2010 respectively, but recovered with a seven percent average annual growth between 2010 and 2015.

The slowdown was partly due to the Asian Financial Crisis in 1997/1998, which triggered a loss of investor confidence in the region and weakened global demand (Jomo, 1998). However, global demand soon recovered, but Malaysia’s, and Penang’s economic growth stalled, because Malaysia was in the middle-income trap. Due to its dependence on cheap labour, the country was, on the one hand, losing out to cheaper competitors, and at the same time, lacking the necessary quality of human capital to compete against knowledge-and innovation driven economies. The emergence of China as a key investment destination in the 1990s was thus bad news for Malaysia (Ong, 2000).237

d. Income Levels

Penang’s GDP increased remarkably over the last 44 years from RM794.7 million in 1970 to RM66.9 billion 2014, with a corresponding increase in GDP per capita from RM987 to RM40,606.

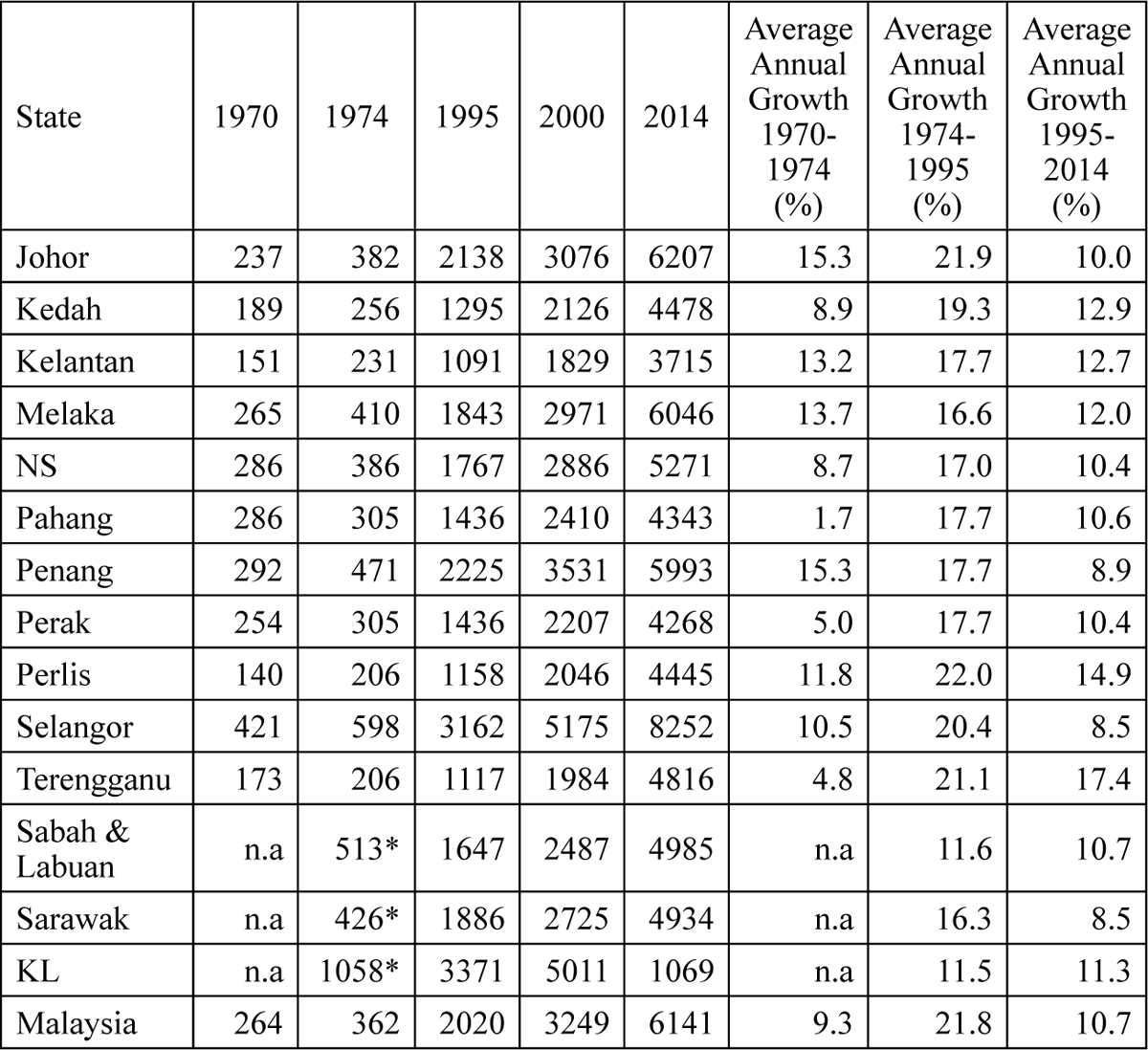

Penang’s nominal mean monthly household income increased eleven-fold, from RM471 in 1974 to RM5,993 in 2014, reflecting the enormous scale of development that was built upon the foundations laid by Lim Chong Eu. Median monthly household income increased even more remarkably, by 18 times to grow to RM4,702 in 2014 from RM241 in 1974, hinting that the distribution of income arising from the growing wealth improved over the course of the last 40 years (EPU).

Yet such income gains need to be viewed more closely, not from a single historical snapshot, but rather from a few shorter, patterned snippets of history. As suggested earlier, Penang’s industrial development and economic growth underwent three “phases”, each portraying a set of challenges, against which issues of poverty and inequality may be understood. The first is a very brief phase of four years from 1970 to 1974. The second extends from 1975 to 1995 while the third is from 1996 to 2015.

The first phase may be described as a transitional period, when a very broad range of new policies and practices were drafted and institutions established, as part of the overarching New Economic Policy, when the country embarked on a developmental journey that sought to break away from the laissez-faire regime. In Penang’s case, a new government had also just come to power.

Lim Chong Eu moved fast, and was the first to establish a FTZ, the Bayan Lepas FTZ, in 1971. The Bayan Lepas FTZ attracted eight electronics and electrical multinational companies in its first years, which delivered the first of many more jobs to come. Penang’s mean household income was among the highest during this phase, just behind Kuala Lumpur and Selangor, and together with Johor, grew at an average rate of 15.3 percent per annum, the fastest throughout the first phase.

The second phase, from 1975-1995, was a period of rapid growth in an environment where virtually all other states in the federation were galloping out of underdevelopment at breakneck speed. As evident from Table 7 below, Penang’s monthly household income increased at an even more rapid pace (17.7% per annum), to reach RM2,225 in 1995. Even so, Selangor, despite ceding Kuala Lumpur to the Federal Government to become a federal territory on 1 February 1974, outperformed Penang’s growth and edged it to a distant third with a mean monthly gross household income of RM3,162 to emerge second behind Kuala Lumpur (RM3,371) in 1995.

Table 6.7: Mean Monthly Gross Household Income by State, 1974-2014

Indeed, although Penang managed to stay among the three states with the highest mean monthly household incomes in the country in 1995, its increase relative to the other states between 1974 and 1995 was not spectacular. As Table 6.7 shows, less developed states such as Kelantan and Pahang, and Perak recorded the same percentage increase (17.7%) in monthly household incomes, whereas Johor (21.9%), Kedah (19.3%), Perlis (22.0%), Selangor (20.4%) and Terengganu (21.1%) recorded even higher increases.

The pace at which household income increased declined for all states in the third phase (1995-2014). Penang’s average annual monthly gross household income growth dropped to a comparably dismal 8.9 percent in 1995-2014, from 17.7 percent in 1974-1995. Only two states, Sarawak and Selangor, recorded lower growth rates during this period.

This considerable slowdown in household income growth for Penang saw Johor (RM6,207) and Melaka (RM6,046), in addition to the two historically more advanced economies of Kuala Lumpur (RM10,629) and Selangor (RM8,252) surpassing Penang’s mean monthly gross household income of RM5,993 in 2014.

e. Poverty

Penang’s economy was at the crossroads in the 1960s, since it had yet to develop a new developmental initiative that could arrest its declining role as a regional commercial and trading centre. In spite of this uncertainty and decline, its economy was, in several respects, stronger than that of most other states in the country. Penang’s GDP was fifth largest in 1970, and GDP per capita was third behind Selangor and Sabah, while its mean monthly gross household income was second to Selangor. Penang was also the most urbanized state in 1970.

Even so, poverty, at 43.7 percent in 1970, was widespread, and remained high at 32.4 percent in 1976 (epu.gov.my; updated 25/08/2015)238, although the Fourth Malaysia Plan (Malaysia, 1981) reported that poverty had declined to 29.5 percent in 1976.239

With rapid industrialization and full employment, poverty declined rapidly to below ten percent in 1989 and below two percent in 1997. This trend continued, though less dramatically. In 2014, only 0.3 percent of households in Penang were poor. These households were probably stubborn remnants of bureaucratic processing since the state had committed to top-up incomes for households with less than RM770.00 in 2013.240 The recent increase in the minimum monthly wage to RM1,000 in Peninsular Malaysia and RM920.00 in Sabah and Sarawak, which came into effect on 1 July 2016, only marginally improved the poverty situation since much of this stubborn remnant is very probably confined to individuals and households who are incapacitated either by illness, debt, unemployment/underemployment or are engaged in agriculture or the informal sector, who may not have sought for assistance or have been overlooked or neglected by the apparatuses of the state.241

Very clearly, Lim Chong Eu’s leadership in setting up the sustained development of export-oriented manufacturing and tourism was an important driver for this later success, particularly through the large employment opportunities that became available. It needs to be added, however, that this was aided by the fact that Penang had a relatively small agricultural base and a large modern services sector in 1970.

Table 6.8: Incidence of Poverty, 1970-2014

The virtual elimination of poverty in Penang was accompanied by a gradual reduction in inequality, with the Gini Coefficient declining from 0.597 in 1974 to 0.452 in 1984, 0.405 in 1995, 0.398 in 2004 and 0.364 in 2014. This is consistent with the gradual narrowing of the mean and median monthly gross household incomes (UNDP and EPU, 2016).

f. Urban Poverty

Due to its small size and important role in entreport trade over much of the colonial period, Penang has had a relatively larger urban population than other states.

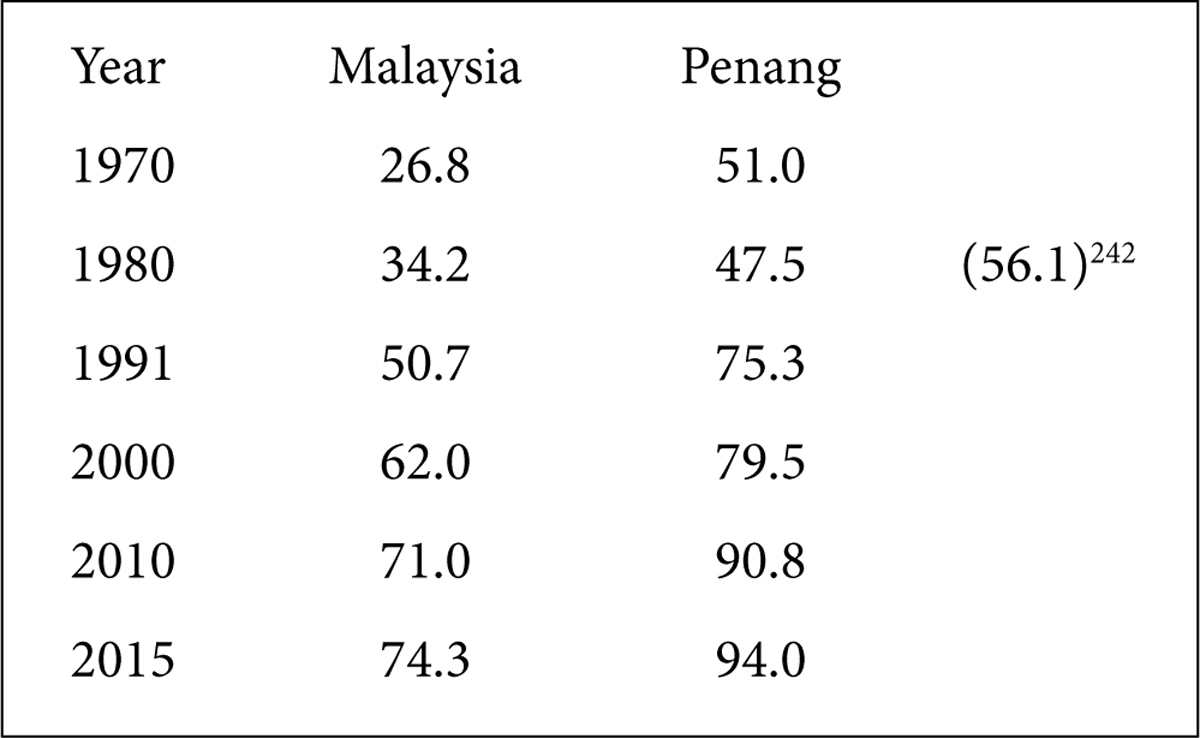

Table 6.9: Percentage of Urban to Total Population

Even so, until fairly recently, the majority of its population lived in rural areas. In 1970, one half of Penang’s population were urban residents. The Bayan Lepas area, where the country’s first FTZ was to be located just two years later, was still rural then. The Department of Statistics estimated that the urban population declined to 47.5 percent of the state’s total population in 1980. This is quite a surprise, and went against the tide of development that was taking place then.

Manufacturing was, after all, growing at an average annual rate of 11 percent between 1970-1975 and 18 percent between 1975 and 1980, raising its share of GDP from 12.7 in 1970 to 24.3 percent in 1980. Even if the majority of the population remained rural in 1980, a significant section of the rural residents were probably daily commuters, traveling to and from their more spacious and cheaper dwellings in villages to places of work in town, or at factories just outside of town.243 This was very evident in the 1970s and 1980s, for even if 56.1 percent of the population was rural in 1980, 86 percent were employed in predominantly urban sectors (manufacturing, construction, services) of the economy (see Table 6.10 below). The important role played by a significant section of the rural population in meeting the cheap labour needs of the industrial complexes in the urban areas meant that more members of rural households earned more regular and higher urban incomes.

Table 6.10 Employed Persons by Industry, Penang, 1984-2014 (%)

Malaysia (2015); Rasiah, R. (1991)

The incidence of urban poverty declined rapidly, from 16.6 percent in 1976 to 1.1 percent in 2009, and, except for households that remained outside the watch of the state bureaucracy, would have now been virtually eliminated. In 2013, the state government declared a commitment to ensure that all households earned a monthly minimum income of RM770.00. The new minimum wage of RM1,000 per month in Peninsular Malaysia implemented on 1 July 2016, further facilitated in the complete elimination of poverty.244

Access to affordable and decent housing is an especially important measure of the standard of living in urban areas, and should be considered in the drawing of any poverty line. Such access has been defined mainly in terms of house ownership, however, and consequently translated in terms of developing low-cost or affordable housing and providing subsidized housing especially for first-home buyers. Almost three-fourths (72.5 percent) of the country’s households own houses. Home ownership is predictably higher among the rural (81 percent) than among the urban (69 percent) population (KRI, 2015). Penang has done well on this score; for although the great majority (94 percent) of the state’s population is urban, home ownership is higher (77.5 percent) than the Malaysian average; and 83.5 percent of its rural population and 76.8 percent of its urban population are home owners.

This suggests that Penang has, more or less, kept pace with increasing population pressure and housing values throughout the industrial era.245 The Rifle Range Flats in Air Hitam, built from 1969 onwards, was Penang’s first affordable housing project,. Under Lim Chong Eu’s leadership, the state carried out many more affordable housing projects, especially through the Penang Development Corporation, initially in Bayan Baru, a new township close to the FTZ in Bayan Lepas, but later spread to other areas in the state.

Indeed, in 2000, there were 355,436 dwelling units to only 284,969 households, or an over-supply of 70,467 dwelling units. This over-supply problem continued. By 2005, an additional 114,895 units were built, raising the housing stock to 470,331. Thus, an annual average of 22,979 new dwelling units were brought into the market during the five years between 2000 and 2005, when demand for new units was estimated at only 12,300 per year (Goh, 2009).

The over-supply situation persisted (Goh, 2009). In 2009, a few unsold blocks of government-built apartments stood in bold testimony of the irony of the state “over-doing” it for the poor. Another over-supply situation surfaced again in 2015 (Mok, 2015, David Tan 2015),246 barely two years after the DAP-led Pakatan state government announced the establishment of a RM500 million Public Housing and Affordable Housing Fund247 and other measures to curb speculation in property. The state government soon discovered that many of its new affordable housing projects could not take off. This was because the take-up of dwellings under these projects fell short of the 60 percent minimum required before they could be viable, with many applicants dropping out after failing to secure loans for the purchases.248 In response, the state government liberalized access to affordable housing projects by increasing the net household income cap so that a larger pool of applicants would be eligible to purchase dwellings under such projects.249 In addition, 30 percent of the affordable housing projects opened up to those who already owned property. Clearly, this decision to address the problem of over-supply did so by changing the criteria for eligibility to affordable homes rather than by making such dwelling units more affordable. Indeed, the bulk of these units were priced beyond the earning capacity of the average household (David Tan, 2015).

The recent over-supply situation was partly triggered by Bank Negara’s increased control of bank approval of housing loans, which, in turn, was precipitated by serious concerns regarding the country’s rising public debt. As a result, a higher percentage of housing loan applications was rejected, reining in demand for residential property. The NAPIC (2015) Property Sales Data for Penang, Q3 2015 corroborate the reduced demand, reporting a nine percent reduction in the number of transactions of residential property between Q3 2014 and Q3 2015.

However, Bank Negara guidelines on housing loan approval are probably only one part of the story. If housing loans represent an important proportion of public debt, then perhaps the country is developing more residential properties than it should. After all, the bulk of these relatively “cheap” dwelling units remain beyond the means of a good segment of the bottom 40.

Thus, the state was trapped in a “build-for-sale” scheme. Since there were not enough people in the target groups who could afford to buy such units, the state subsequently decided to sell them to people who were earlier not eligible for such purchases. This situation persisted, and other measures will need to be considered to change the trend, for example, through building low-cost and affordable homes for rent instead of for sale.

Property prices continue to rise, even when there is an over-supply of stocks. NAPIC’s House Price Index for residential property prices for the country as a whole increased by about 15.7 percent between Q3 2014 and Q3 2015. The average price of apartments and condominiums in Seberang Prai was RM192 psf in 2015. This represented a 23 percent increase over the 2014 level. (theedgeproperty.com, 2016).

One critical factor that determines the price of dwelling units is the price of land. This has soared over the last several years, particularly with the development and completion of the second bridge linking Batu Kawan on the mainland and Batu Maung on the island. Where vacant land was priced at between RM8-9 psf (per square foot) in Batu Kawan before the Second Penang Bridge project was announced in late 2006, it fetched between RM50-60 psf in 2014, a more than six-fold increase in eight years. The price of vacant land increased five-fold in Batu Maung during the same period, while the price of condominiums and landed property increased by slightly more than 250 percent in the same period. (David Tan, 2014).

An improbable ten percent annual wage increase over the same eight-year period would still not have made it possible for the average wage earner to catch up with the increase in the price of an affordable home, or to service a longer loan re-payment period. Thus, clearly, a serious review of “home-ownership” democracy is necessary, especially when the state government has to surrender a good share of its land to enable private developers to build “affordable homes”. With only eight percent of state land left for future development, the state government’s capacity to intervene in the public and affordable housing sector can be expected to decline over time.

The constraints of a very limited supply of land and the lure of making money from real estate have attracted a steady increase in investment in real estate, leading to a spiralling increase of property prices. Thus, the cost of doing business has been relatively more expensive in Penang than in other regions in the country or in different parts of Asia in the mid-1990s (Ong, 2000) and in the first decade of the 21st century (Kharas, Zeufack, Majeed, 2010,). Of late, the state government has actively sold land for property development to “seek rents” to improve its finances, risking a further rise in the general cost of goods and services, as well as the cost of doing business (LSS Report, 2015).

g. Rural Poverty

Agriculture was backward in Penang in the 1960s, for productivity was low, off-farm employment opportunities were limited and underemployment was high (Purcal, 1971). Clearly, this is no longer true today since there has been an enormous but relatively uneventful demographic shift over the last four decades, facilitated by the successful development of the manufacturing and service sectors.

With the growth of urban-industrial employment, operators of predominantly small-scale farms abandoned their uneconomic holdings for jobs offering higher and steady incomes in comfortable settings. Some of these lands may have continued with pre-existing land use, but large areas were left “idle”,250 while others were converted to non-agricultural uses. “Idle lands” emerged as a common feature in villages, where land was once scarce. The decline of planted area under rubber smallholdings is reflective of this. In 1960, the land area under rubber smallholdings totaled 765,600 hectares. With generous state support, especially under the NEP years, smallholding agriculture expanded so that by 1990 such use of land increased to 1,488,000 hectares. However, the large urban population drift that accompanied successful urbanization and industrialization led to a massive decline of smallholding agriculture, to 621,300 hectares in 2014 (Malaysia (DOS), 2015), or a decline by 58.2 percent in the last 24 years.251

Penang is one of Malaysia’s smallest states, and also one of the most urbanized in the country. It was a regional entreport hub for much of the colonial era, but is today home to three free industrial zones. The Bayan Lepas FIZ is the best known among the three, while the remaining two FIZs, the Prai Wharf and Prai, are located in Seberang Prai on the mainland. With such history and close proximity to the pressures of the market, we can expect operators of smallholding agriculture in Penang to respond to the many urban and industrial opportunities that are available.

The limited data available at the state level shows that the total land planted under rubber declined by 43 percent from 19,000 hectares in 1990 to 10,838 hectares in 2011. The lands that were once cultivated with rubber trees have either been left idle or have attracted new tenants or owners, who have ventured into other forms of agriculture, or into new land uses, such as property development.252 Likewise, large sections of what were once paddy fields have been converted into other forms of land use. It was reported that within a short span of eight years between 2000 and 2008, about one half of the land area in Seberang Prai ceased cultivating paddy. (Samat et al, 2014). Due to the expansion of the urban economy, many of these villages became peri-urban villages, with a significant percentage of the farming population cultivating more profitable crops, or taking up non-farm forms of employment, with the majority commuting to work in the manufacturing and services sectors. Thus, farming, once the source of small incomes, is no longer the only or the predominant source of income for households residing in the countryside (Malaysia, 1991; Kortteinen, 1999).253

Thus, very few people are engaged in the agricultural sector in Penang today, where poverty is limited to less than one percent of the rural population. The large majority who remain in agriculture, especially small-scale farmers, are ageing parents (Terano and Fujimoto, 2009)254. The average age of paddy farmers is today above 60 years and 40 percent of rubber smallholders are above 60 years in age (MPIC, 2014).

Conclusion

Penang underwent a very successful process of industrialization to become a well-known electronics hub in the world. This successful transition was set off by the visionary Lim Chong Eu. He remained as Chief Minister long enough (1969-1990) to see to it that Penang’s development followed the ideas and plans that he envisioned. He must have had earlier misgivings that the multinational companies in the electronics industry would sooner or later desert Penang’s shores for cheaper locations elsewhere, but worked with his team to not let this happen.

Right to this day, the electronics industry continues to make an immense contribution to Penang’s economy. So does the tourism industry. Penang has done exceptionally well economically. There is full employment. Despite the very high urban population, limited land and serious issues regarding the allocation of state resources in the development of public housing, Penang has managed to provide more than enough low-cost and affordable homes.

Lim Chong Eu’s vision of Penang’s development was very much tied to the development of the northern region as a whole. The Northern Corridor Economic Region offers his successors a ready platform to harness the combined potential of the northern states for a better Penang.

References

Abdul Rahman Embong and Sharifah Zarina. (2010). “The Razak Education Report, National Unity and Human Capital Develoment”, in H. Osman Rani (ed.), Tun Abdul Razak’s Role in Malaysia’s Devlopment, Petaling Jaya: MPH Publishing Sdn Bhd.

Abdul Rahman Hasan and Prema Letha Nair (2014). “Urbanisation and Growth of Metropolitan Centres in Malaysia”, Malaysian Journal of Economic Studies, 51 (1): 87-101.

Aikawa, Michael Hiroshi “FTZ Development for Export-oriented Industrialisation in Penang, Malaysia: The Role of Government in Supporting TNCs and Local SMEs”

Anazawa, Makoto (“1985). Free Trade Zones in Malaysia”, Hokudai Economic Papers, 15: 91-148

Athukorala, Premachandra (2012). “Growing with Global Production Sharing: The Tale of Penang Export Hub, Malaysia”, Paper for the International Conference on Trade, Investment and Production Networks in Asia organised by Leverhulme Centre for Research on Globalisation and Economic Policy, University of Nottingham, 16-16 February 2012, Kuala Lumpur.

Athukorala. Prema-chandra and Jayant Menon (1996). “Foreign Investment and Industrialization in Malaysia: Exports, Employment and Spillovers”, Asian Economic Journal, 10 (1): 29-44.

Chet Singh (2016) “Building Penang, Inspiring Malaysia”, Penang Economic Monthly, February 2016.

Chet Singh. “PDC’s Success and Malaysia’s Lost Opportunities”, Penang Economic Monthly, February 2016.

Department of Statistics. Labour Force Suvey. Putrajaya: ______. (2015). Malaysia Economic Statistics: Time Series. Putrjaya.

Drabble, John H. “Economic History of Malaysia”, https://eh.net/encyclopedia/economic-history-of-malaysia/

EPU (Economic Planning Unit). “Household Income and Poverty, 1970-2014” (updated 25/08/2015). EPU (www.epu.gov.my). Putrajaya: Prime Ministers’s Department.

Fujimoto, Akimi. “Evolution of rice farming under the new economic policy.” The Developing Economies 29.4 (1991): 431-454.

Fujimoto, Akimi. “Farm management analysis of Malay and Chinese rice farming in province Wellesley, Malaysia.” The Developing Economies 21.4 (1983).

Goh, Ban Lee (2009). “Social Justice and the Penang Housing Question”, Penang Economic Monthly, 11 (8): 1-17.

Hechter, Michael (1978): Group Formation and Cultural Division of Labour, American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 84, No. 2 (Sep., 1978), pp. 293-318

Henderson, Jeffrey & Richard Phillips (2007): Unintended consequences: social policy, state institutions and the ‘stalling’ of the Malaysian industrialization project, Economy and Society, 36:1, 78-102

Hirschman, Charles (1980) “Demographic Trends in Peninsular Malaysia, 1947-1975.” Population and Development Review 6:103-125

Ho Chin Siong (2008). “Urban Governance and Rapid Urbanization Issues in Malaysia”, Jurnal Alam Bina, 13 (4): 1-24.

Hutchinson, Francis Edward (2008). “Developmental” States and Economic Growth at the Sub-National Level: The Case of Penang”, Southeast Asian Affairs, 2008(2008): 223-244.

Ikemoto, Yukio. 1985. “Income Distribution in Malaysia: 1957-1980”, The Developing Economies, 23 (4): 347-367.

Jomo K. S. and Wee Chong Hui, Policy Coherence Initiative on Growth, Investment and Employment The Case of Malaysia, Prepared for ILO, Geneva.

Jomo, K.S. (1986) A question of class: capital, the state, and uneven development in Malaya. Singapore: Oxford University Press.

United Nations Malaysia and EPU (2016). Malaysia Millennium Development Goals Report 2015. Kuala Lumpur: United Nations Malaysia.

Karunaratne, N.D. and M.B. Abdullah (1978). “Incentive Schemes and Foreign Investment in the Industrialization of Malaysia”, Asian Survey, 18 (3): 261-274

Kharas, Homi, Albert Zeufack & Hamdan Majeed (2010). Cities, People & the Economy: A Study on Positioning Penang. Kuala Lupur: Khazanah Nasional Berhad and World Bank.

Kinuthia, Bethuel Kinyanjui. (2009). “Industrialization in Malaysia: Changing Role of Government and Foreign Firms”. Paper Presented at the DEGIT (Dynamics, Economic Growth and International Trade) XIV Conference, UCLA, June 5-6, 2009

Koay Su Lyn and Steven Sim. “A History of Local Elections in Penang. Part I: Democracy Comes Early, Penang Monthly, January 2016.

Lim Chong Eu (2005). “Building On Penang’s Strengths: Going Forward”. Penang Lecture 2005. Penang: Socio-economic and Environmental Research Institute.

MacAndrews, Colin (1977). Mobility and Modernisation: The Federal Land Development Authority and its Role in Modernising the Rural Malay. Yogyakarta: Gadjah Mada University Press.

Malaysia. Malaysia Plans (First-Eleventh, 1965; 1971), Government of Malaysia.

Malaysian Rubber Board. 2015. Natural Rubber Statistics. Kuala Lumpur: 2015.

Mok, Opalyn (2015). “Penang Loosens Affordable Housing Rules to Stimulate Sector”, The Malay Mail Online, Oct 12.

Muhammad Ikmal Said (1991). “Capitalist Development and Changes in Forms of Production in Malaysian Agriculture”, in Muhammad Ikmal and Johan Saravanamuttu (eds.). Images of Malaysia. Kuala Lumpur: Persatuan Sains Sosial Malaysia.

NAPIC (National Property Information Centre), Property Sales Data, Penang, Q3 2015. Putrjaya: Valuation and Property Services Department, Ministry of Finance.

Narayanan, Suresh (2008), “On the stalling of the Malaysian industrialization project” Economy and Society, 37 (4): 595-601

NEAC (National Economic Advisory Counci). 2009. New Economic Model for Malaysia. Part 1: Strategic Policy Directions. Kuala Lumpur: Prime Minister’s Office.

Narimah Samat, Applications of Geographic Information Systems in Urban Land Use Planning in Malaysia

Ong, Anna (2000). Penang’s Manufacturing Competitiveness. Penang: Socio-Economic Environmental Research Institute.

Osman Rani, H. (2010). “Transition to an Industrial Economy”, in H. Osman-Rani (ed.), Tun Abdul Razak’s Role in Malaysia’s Development.

Petaling Jaya: MPH Publishing Sdn Bhd.

Penang (2013). “Penang State Government New Housing Rule, 2013”, Press Statement by Penang Chief Minister Lim Guan Eng in Komtar, George Town on 18.12.2013.

Rasiah, R. (2008). “Drivers of Growth and Poverty Reduction in Malaysia: Government Policy, Export Manufacturing and Foreign Direct Investment”, Malaysian Journal of Economic Studies 45 (1): 21-44.

Rasiah, R. (2010): Are electronics firms in Malaysia catching up in the technology ladder?, Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy, 15:3, 301-319

Rasiah, R. (2009): Expansion and slowdown in Southeast Asian electronics manufacturing, Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy, 14:2, 123-137

___________ (1991). “Foreign Firms in Penang’s Industrial Transformation”, Jurnal Ekonomi Malaysia, 23: 91-117

Ritchie, Bryan K. (2005)” Coalitional Politics, Economic Reform and Technological Upgrading in Malaysia”, World Development, 33 (5): 745-761.

Rudner, Martin. 1983. “Changing Planning Perspectives of Agricultural Development in Malaysia”, Modern Asian Studies, Vol. 17 (3). pp. 413-435.

Shamimi Mokhtar (2012). “Population and Spatial Distribution of Urbanisation in Peninsular Malaysia 1957 – 2000”, GEOGRAFIA Online: Malaysia Journal of Society and Space, 8 (2): 20 – 29.

Shamsulbahriah Ku Ahmad 2010). in H. Osman Rani (ed.), Tun Abdul Razak’s Role in Malaysia’s Development. Petaling Jaya: MPH Publishing Sdn Bhd.

Sim, Steven and Koay Su Lyn, “Local Elections as the Foundation of Democracy, Penang Monthly, March 2015.

Sivalingam, G. (1994). World Back. The Economic and Social Impact of Economic Processing Zones: The Case of Malaysia”, Working Paper No. 66, International Labour Offie. Geneva: International Labour Offie.

Sri Wulandari, Malaysia’s Free Industrial Zones: Reconfiguration of the Electronics Production Space. Asia Monitor Resource Centre (AMRC)

Tan, David Tan, “Penang Affordable Housing Glut?” The Star Online, 22 June, 2015.

Tan, David. “Bridge Boosts Land Prices” The Star, 20 January 2014.

Tan, David. (2014). “Land Prices Continue to be on the Rise” The Star Online, 30 December.

Tarmiji Masron, Usman Yaakob, Norizawati Mohd Ayob, Aimi

Terano, Rika, and Akimi Fujimoto (2009). “Employment Structure in a Rice Farming Village in Malaysia-A Case Study in Sebrang Prai.” Journal of International Society for Southeast Asian Agricultural Sciences 15 (2): 81-92.

Usman Yaakob, Tarmiji Masron* & Fujimaki Masami “Ninety Years of Urbanization in Malaysia: A Geographical Investigation of Its Trends and Characteristics”,

theedgeproperty.com “Property Snapshot 3: What are Prices Like in Mainland Penang?” theedgeproperty.com,27 January, 2016.

UNDP (United Nations Development Programme) (2014). Malaysia Human Development Report 2013: Redesigning an Inclusive Future. Kuala Lumpur: UNDP.

Usman Haji Yaakob and Nik Norliati Fitri Md Nor (2013). The Process and Effects of Demographic Transition in Penang, Malaysia Kajian Malaysia, Vol. 31 (2): 37–6

Yeow Tek Chai and Ooi Chooi Im (2009). The Development of Free Industrial Zones–The Malaysian Experience”, 27 April, 2009. Washington: World Bank.

205I would like to thank Chyi Lee for assisting in preparing this chapter, in particular with Part II (c).

206In that year rubber and tin accounted for 62 percent of the total value of exports; with the former contributing 50 percent and the latter 12 percent respectively (Malaysia.1965:24).

207It was estimated that only 40 percent of domestic demand for manufactured consumer goods were produced locally (Malaysia. 1965:130).

208This was due to declining prices for primary commodities, especially of rubber, copra and coconut oil, and diminishing tin, iron ore, and known petroleum reserves at that time.

209The Investment Incentives Act 1968 provided for a broader range of incentives, including income and development tax relief for companies given pioneer status, investment tax credit, labour utilization relief, export incentives, tax relief for companies that locate their factories in certain designated areas and incentives for the establishment and expansion of hotels. In addition, infrastructure, facilities, the provision of industrial finance and the establishment of industrial estates were also introduced.

210“In manufacturing, investment had largely been directed [towards] production for the domestic market. The opportunities for further investment in import substitution industries gradually diminished and new investment began to look outward to the export market” (Malaysia, 1971:26-27). When the limits of the import-substituting regime became evident, the government appointed the Raja Mohar Committee to accelerate the pace of industrialization. The Committee’s recommendations were put into effect through the Investment Incentives Act of 1968. This Act departed from the earlier emphasis on import-substitution with provisions that promoted “the expansion of export in manufactures” (Jomo, 1986:222).

211During the same period, agriculture’s share of GDP decreased from 30.8 to 22.2 percent (Malaysia.1981:15), while its share of exports decreased from 52.1 percent to 35.8 percent (Malaysia.1981:20).

212The electronics sector only emerged in 1972. The electrical goods sector accounted for 1.8 percent of manufactured exports in 1970.

213This policy was aimed at building a more integrated industrial structure with strong linkages across the different sectors of the economy, unlike the dual industrial enclaves of the export-oriented and import-substituting industries that had emerged then.

214Employment and value added in the electrical and electronics sector slowed down to 5.2 percent and 11.4 percent respectively in the 1979-1985 period (Rasiah, R.2010).

215The electrical and electronics sector, which grew at only 5.2 percent in 1979-1985, recorded an average annual growth of 26.8 percent between 1986 and 1990.

216Between 1962 and 1967, the average annual growth of the labour force was 2.9 percent, whereas the corresponding growth of employment was 2.7 percent.

217The ethnic riots were as much a result of Malay grievances about their marginal position in the ethnic division of labour as they were frustrations among Malays over not making much headway in urban environments.

218In 1967, for example, 11 percent of workers, mainly in rural occupations, worked for less than 25 hours in a week (Malaysia,1966:99).

219Declining commodity prices and increasing prices of consumer goods aggravated the poor conditions of smallholdings sector: “The result was that smallholders were caught in a vicious cost-price squeeze: they were faced not only with the steepest decline in rubber prices but also the sharpest rise in consumer prices since Malaysia’s independence in 1957” (Stubbs, 1983:87).

220For an analysis of the conditions of small-scale producers in the rice sector, see (Muhammad Ikmal. 1987).

221Between 1957 and 1960, 300 rubber plantations with a total area of 230,000 acres, or 11 per cent of total estate acreage, were sub-divided, and sold to new owners, who, in turn, rented them out to tenants (Rudner.1981:95). Fee (2002) reported that the total area of rubber plantations sold off between 1950 and 1967 amounted to about 18 percent of total estate acreage.

222The ethnic riots were a result of Malay grievances against their marginal position in the ethnic division of labour, their frustrations of not making much headway in the urban environments that they had migrated into, and the looming threat of erosion of their political position.

223Arguably, the situation then fits well into Michael Hechter’s (1978) notion of society fragmented by a “cultural division of labour”.

224The aboriginal groups of Peninsular Malaysia and the Bumiputera groups of Sabah and Sarawak are the exceptions. The incidence of poverty in Sabah declined significantly from 19 percent in 2009 to 3.9 percent in 2014. Rural poverty declined from 33 percent to 7.4 percent in the same period. At the same time, the incidence of poverty declined from 5.3 percent in 2009 to 0.9 percent in Sarawak in 2014.

225Very quickly, the political and economic integration of the states in Malaya was broadened to include other neighbouring British territories, visibly, Singapore and the North Borneo states of Sabah and Sarawak to form “Malaysia” in 1963. Singapore, which parted company in August 1965, was very clearly a very huge threat to Kuala Lumpur’s leadership in the new geography.

226Indonesia’s “konfrontasi” with Malaysia between 1963 and 1965, dealt a harder blow to Penang’s fading trading fortunes.

227Chong Hon Nyan, “Penang and the Entreport Trade”, The Straits Times, 6 August 1965. p. 10.

228In 1958, Lim Chong Eu was elected President of the conservative Malayan Chinese Association (MCA), the key Chinese partner in the UMNO-led multi-ethnic Alliance coalition. He resigned from the MCA after failing to secure more seats for the MCA in the 1959 general elections.

229On the other hand, the non-Malay political parties asserted that all citizens are equal, and that no one group is any more deserving of state largesse than any other. The campaign trails of the non-Malay opposition parties, such as the Democratic Action Party and Gerakan and People’s Progressive Party, centred on building a “Malaysian Malaysia”, a popular clarion call for getting rid of “special rights” for the Malays and other indigenous communities at a time when they were in desperate need to make economic headway.

230Lim Chong Eu (2005) gave us a glimpse of the relationship that developed between him Abdul Razak and Ismail Mohammed Ali during this time. “I had also established the beginning of very close State and Federal Government relationships, irrespective of political partisanship…The NOC (and NCC)-SOC interaction served as a very special example of very close State and Federal cooperation. Later, this cooperation was to lead to the formation of the Barisan Nasional on 1st January, 1973, which evolved the principles of Government by Consensus (and at the beginning this included PAS as a constituent member)”.

231Lim Chong Eu (2005) knew exactly what Penang could offer foreign investors. The high unemployment rate meant that the state had “a reservoir of 50,000 potential workforces which we could tap and develop”. He went on to reveal that this was Penang’s selling point, and told potential entrepreneurs and investors that “in Penang we had a young and capable workforce who, if and when given the opportunity, could perform as well, if not better, than the workers anywhere else in the world and at a relatively cheaper cost” (Lim, 2005).

232“In the process of seeking new labour-intensive industries we decided that the best potential was the New Electronics industry… In fact, in close cooperation with M.I.T.I, we had studied the potential job creation opportunities from the making of hair-wigs, to amusement-theme-parks and to casinos (Lim, 2005).