6

Manufacturing Choice

The tightly folded cortex of the human brain is arranged, like a walnut, in two separate halves or hemispheres. The ‘left’ and ‘right’ brains (as they are sometimes informally known) are associated with different abilities. Pop psychology and pop management theory has had a field day with the supposed distinction between left-brained thinking (supposedly logical, quantitative, analytical) and right-brained thinking (presumed to be emotional, creative, empathic), though the reality is far murkier.

In normal life, the two hemispheres of the brain work together remarkably fluently – indeed, there is a massive bundle of more than 200 million nerve fibres, the corpus callosum, whose role it is to exchange messages between them (Figure 25).

But what would happen if the two hemispheres were truly split apart – if our left and right brains had to work in isolation? During the 1960s and 1970s, the spread of an experimental treatment for severe epilepsy provided a window into what life is like when the two hemispheres operate in isolation. Severing the corpus callosum surgically turned out to help reduce seizures, apparently by stopping the spread of anomalous waves of the electrical activity that overwhelms the brain. But what would the implications of such a drastic procedure be on the mental functioning of the patient, who is now, one might assume, divided into two distinct ‘selves’? The apparent effects of the operation were surprisingly modest: people could live a normal life, reported no change in subjective experience (e.g. their sense of ‘consciousness’ was as unified as ever), had near normal verbal IQ, memory recall and much more.

Careful analysis in the laboratory revealed that the two halves of the cortex were, indeed, functioning independently. Consider a particularly striking study by one of the pioneers of split brain research, the psychologist and neuroscientist Michael Gazzaniga. He simultaneously showed a split-brain patient, P.S., different pictures on the left and right halves of the visual field.2 The left-hand picture was a snowy scene; the brain’s cross-over wiring pipes this information through to the visual cortex of the right hemisphere. The right-hand picture was a chicken’s foot, which is sent to the corresponding area in the left hemisphere. Like most of us, P.S.’s language-processing abilities are strongly concentrated in the left hemisphere; the right hemisphere, in isolation, has minimal linguistic abilities. P.S.’s left hemisphere was able to report what it could see – and fluently describe the chicken claw, but P.S. was unable to say anything about the snowy scene that the right hemisphere could see.

For each picture, P.S.’s task was to pick out one of the four pictures which was associated in some way with the picture being viewed. Both hemispheres could do this. P.S.’s left hemisphere directed the right hand (the brain’s cross-over wiring again) to pick out a picture of a chicken’s head, matching up with the chicken’s claw. And P.S.’s right hemisphere directed the left hand to pick out a picture of a shovel, to match up with the snowy scene in the left picture.

But how would P.S. (or rather, P.S.’s left hemisphere) explain these actions? P.S.’s language-processing left hemisphere was, after all, totally unaware of the snowy scene – so on seeing the left hand (controlled by the right hemisphere) choosing the shovel, one might expect P.S.’s left hemisphere to say nothing, or admit to being utterly mystified. Instead, P.S. explained both choices very neatly: ‘Oh that’s simple. The chicken claw goes with the chicken. And you need a shovel to clean out the chicken shed.’ Elegant, but entirely wrong! The left hemisphere was entirely unaware of the snow–shovel association that must really have triggered the right hemisphere’s choice – because the left hemisphere was totally oblivious to the snowy scene. But the left hemisphere readily invented a plausible-sounding explanation, none the less.

Gazzaniga calls the language-processing system of the left hemisphere ‘the interpreter’ – a system that is able to invent stories about why we do what we do. But what the experiment with P.S. shows is that the interpreter is a master of speculation. It can have no possible insight into the origin of the choice of the shovel (the snowy scene) because those causes arise in the half of the brain to which it is disconnected – yet it invents an explanation with a flourish.

In another study, Gazzaniga presented a split-brain patient, J.W., with the word ‘music’ in the left visual field (routed through to the right hemisphere, which has only rudimentary language) and the word ‘bell’ in the right visual field (routed through to the language-processing machinery of the left hemisphere). The left hand chose an ‘appropriate’ picture – guided by the right hemisphere, it chose a picture of a bell (the right hemisphere has some basic knowledge of word meaning). When this was queried, J.W. responded: ‘Music – last time I heard any music, it was from the bells outside here, banging away’ – a comment on the bells regularly ringing out from the nearby library on the campus at Dartmouth College, New Hampshire, where the study was carried out. Again J.W.’s left hemisphere interpreter was making a creditable attempt to explain the choice – but an entirely wrong one. The left hand chose a picture of a bell because the corresponding right brain had just seen the word bell – but of course the left hemisphere had no possible way of knowing this. But the interpreter just ploughs cheerfully onwards, even when it cannot possibly have any knowledge of what actually caused the choice.

So the left-hemisphere ‘interpreter’ invents ‘stories’ to explain the right hemisphere’s choices – and does so naturally and fluently. Indeed, the very ability of the ‘interpreter’ to create such stories may be crucial to maintaining the sense of the mental unity for the split-brain patient. But the very existence of the interpreter suggests the possibility that, for people with normal brains, choices are also naturally and fluently explained after the fact. So while we may imagine that our justifications for our choices merely report the inner mental causes of those choices (the hidden plans, desires, intentions, from within our hidden depths), perhaps we should consider another possibility entirely: that our justifications for our choices are ‘cooked up’, in retrospect, by the ever-inventive left hemisphere interpreter.

Deciding what to say is, then, a creative act, rather than a read-out from a comprehensive inner database of my beliefs, attitudes and values. The speed and fluency with which we can often generate and justify thoughts is impressive. So quick, indeed, that it seems that at the very moment that we ask ourselves a question, the answer springs to mind – so fluent that we don’t realize we are making it up on the spot : we can sustain the illusion that the answer was there all along, waiting to be ‘read off’.

The parallel with perception is striking: we have seen how we glimpse the external world through an astonishingly narrow window, and how the illusion of sensory richness is sustained by our ability to conjure up an answer, almost instantly, to almost any question that occurs to us. Now we should suspect that the apparent richness of our inner world has the same origin: as we ask questions of ourselves, answers naturally and fluently appear. Our beliefs, desires, hopes and fears do not wait pre-formed in a vast mental antechamber, until they are ushered one by one into the bright light of verbal expression. The left-brain interpreter constructs our thoughts and feelings at the very moment that we think and feel them.

ON NOT KNOWING OUR OWN MINDS

Psychologists Petter Johansson and Lars Hall, and their colleagues from Lund University in Sweden, played a trick on voters in the run-up to Sweden’s 2010 general election.3 First, they asked people whether they intended to vote for the left-leaning or the right-leaning coalition. Then they gave people a questionnaire about various topics crucial to the campaign, such as the level of income tax and the approach to healthcare. The hapless prospective voter handed over their responses to the experimenter, who, by a simple conjuring trick with sticky paper, replaced their answers with answers suggesting they belonged to the opposing political camp. So, for example, a left-leaning voter might be handed back responses suggesting, say, sympathy with lower income tax and more private sector involvement in healthcare; a right-leaning voter might be confronted with responses favouring more generous welfare benefits and workers’ rights.

When they checked over the answers, just under a quarter of the switched answers were spotted: in these cases, people tended to say that they supposed that they must have made a mistake and corrected the answers back to previously expressed opinion. But not only did the majority of changes go unnoticed; people were happy to explain and defend political positions which, moments ago, it appeared they didn’t actually hold!

Now, of course the Swedish voting population don’t have split brains – their corpus callosa are fully intact. But the left-hemisphere interpreter appears to be playing its tricks here too. Confronted with questionnaire responses in which she appears to have endorsed lower taxes, the prospective voter’s (presumably primarily left-hemisphere) ‘interpreter’ will readily explain why lower taxes are, in many ways, a good thing – lifting the burden from the poor and encouraging enterprise. But this statement, however fluent and compelling, cannot really justify her original response: because, of course, her original response was completely the opposite – favouring higher taxes.

And this should make us profoundly suspicious of our defences and justifications of our own words and actions, even when there is no trickery. If we were able to rummage about in our mental archives, and to reconstruct the mental ‘history’ that led us to act, we would surely come up short when asked to justify something we didn’t do – the story we recover from the archives would lead to the ‘wrong’ outcome after all. But this is not at all how the data come out: people are able to effortlessly cook up a perfectly plausible story to justify an opinion that they did not express, just as easily as they are able to justify opinions that they did express. And, indeed, we are blithely unaware of the difference between these two cases. So the obvious conclusion to draw is that we don’t justify our behaviour by consulting our mental archives; rather, the process of explaining our thoughts, behaviour and actions is a process of creation. And, as with mental images, the process of creation is so rapid and fluent that we can easily imagine that we are reporting from our inner mental depths. But, just as we reshape and recreate images ‘in the moment’ to answer whatever question comes to mind (How curved is the tiger’s tail? Does it have all four paws on the ground? Are its claws visible or retracted?), so we can create justifications as soon as the thoughts needing justification come to mind. (But why might tax rises help the poor? Well – they pay little tax anyway, and benefit disproportionately from public services; or conversely, why might tax rises harm the poor? Surely they are least able to pay, and are most likely to be hit by the drag taxation puts on the economy.) The interpreter can argue either side of any case; it is like a helpful lawyer, happy to defend your words or actions whatever they happen to be, at a moment’s notice. So our values and beliefs are by no means as stable as we imagine.

The story-spinning interpreter is not entirely amnesic; and it attempts to build a compelling narrative based on whatever it can remember. Indeed, the interpreter works by referring back to, and transforming, memories of past behaviour – we stay in character by following our memories of what we have done before. But Johansson and Hall’s results show that we can be tricked by, in effect, having the experimenter implant ‘false memories’ – misleading information about our past behaviour (being fooled about one’s own past choices).

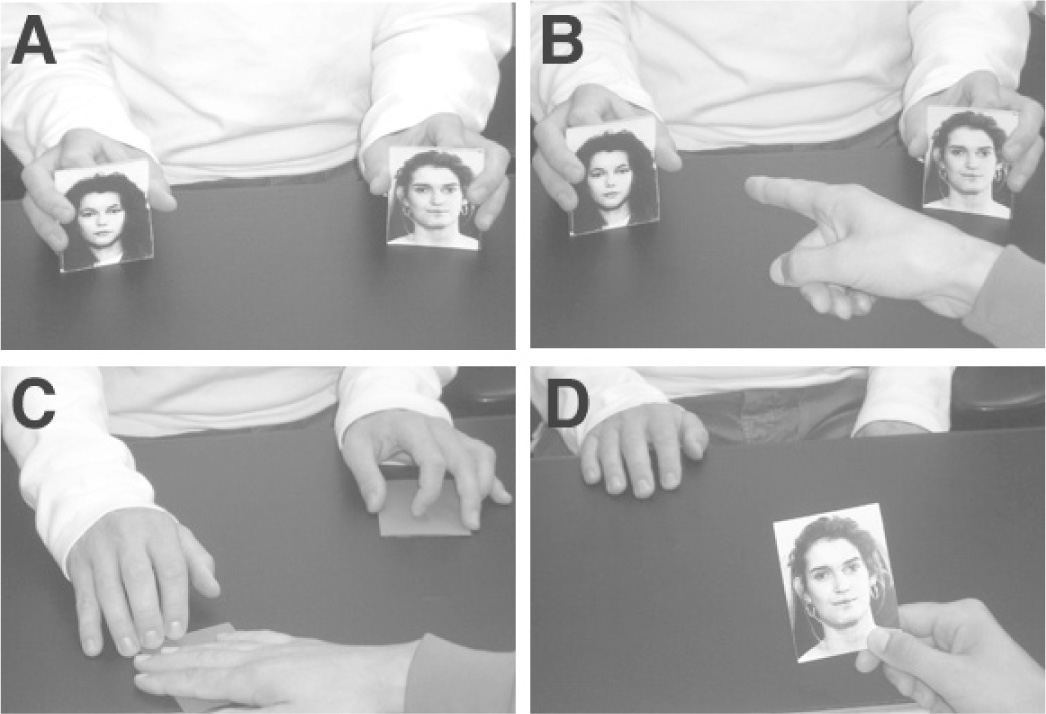

This phenomenon of ‘choice blindness’ – of defending a choice one didn’t actually make – is not limited to politics. Johansson, Hall and their colleagues discovered the phenomenon in a context in which we might believe our intuitions to be deep-seated and immutable – judgements of facial attractiveness. People given pairs of faces on cards (Figure 26) chose the face they found the most attractive, and, on some occasions, by a devious card trick, were handed the non-chosen face. Mostly people didn’t notice the trickery, and happily explained why they made the choice they did not actually make. Analysis of the content of these explanations (their length, complexity, fluency) found no difference between cases where the ‘trick’ had been performed and where it hadn’t. Rather than being stopped in our tracks by being asked to explain a non-choice, the ‘interpreter’ blithely defended the ‘opposite’ point of view, noticing nothing amiss. Often, tellingly, the justifications in cases in which people had been deceived drew on reasons that were transparently post hoc: ‘I chose her because of her nice earrings and curly hair’ can’t be a true report of past decision-making processes of a person who actually chose the picture of a straight-haired woman, without earrings. But it is just the kind of story that the interpreter would scramble together to justify its choice, with hindsight.

And these results have been found not only in experiments concerning politics or faces, but also in taste tests. Setting up a stall in a local supermarket, Johansson and Hall’s team asked people to choose between pairs of jams. They were able to swap the chosen and non-chosen jams by devious use of a double-ended jam jar (each end containing a different jam). The switch could be effected, unnoticed, by surreptitiously turning over the chosen jam jar before presenting it to the customer, so giving them a new taste of the jam they had rejected, rather than the jam they had actually chosen. As before, people mostly didn’t notice; and, where they failed to spot anything amiss, they were just as confident in their ‘fake’ choices as when their choices were ‘real’. Market researchers beware! Even when it comes to something as familiar as jam, most of us have only the most tenuous grasp on what we like.

SHAPED BY STORIES

So is the ‘interpreter’, the spinner of stories defending and explaining our thoughts and actions with such eloquence, no more than a commentator, justifying our past, but unable to shape our future? In fact, the interpreter does not merely describe our past actions, but helps shape what we do next.

Consider faces again. Some years ago, I was part of the study with Johansson and Hall’s team to look at how false feedback might influence future choices. It turned out that, having been told (wrongly) that we prefer face A to face B, we are more likely to express this preference if we make the same decision later. The interpreter explained the decision we didn’t make (it was the earrings, or curly hair), but that very explanation helps shape future decisions. Perhaps even more important is the aim of being consistent – to make choices that the interpreter can justify and defend. If we believe (whether rightly or wrongly) that we said that we preferred face A the first time we were asked, how can we justify having changed our minds? Given the inventive powers of the interpreter, a story could, of course, be cooked up (oh well, we hadn’t noticed the friendly smile of face B . . . were distracted . . . or picked the wrong face the first time by mistake). But it is so much easier, and so much more convincing, to be consistent.5 And with this in mind, we would be biased towards choosing face A the second time we are asked.

And how about politics? Johansson and Hall’s team finished their deceptive political questionnaire study by totting up the left/right significance of people’s answers in plain view of the participants; and then asked them to indicate their left/right voting intentions. So, had the intentions changed from those they had expressed at the beginning of the experiment just a few minutes ago? Remarkably, people who had been given false feedback that led them to the left (and, remember, accepted and even defended some of the left-leaning opinions that they didn’t originally possess) were substantially more likely to express an intention to vote for the left-leaning coalition. It was the same story, in reverse, for the right. And the effects were significant: nearly half the participants had moved across the left/right boundary as a result of the false feedback. There are, it seems, many more floating voters than pollsters might realize.

But can such momentary shifts in thinking really change how people actually vote? We should be sceptical: after all, we might believe that our final decision at the polling booth is the summation of a myriad of occasions in which political issues have run through our minds. No single moments, one might hope, should have a disproportionate influence.

A remarkable study from Cornell University, in the run-up to the 2008 US presidential election, suggests, in contrast, that even apparently modest experimental manipulations can lead voters to change their minds.6 Participants took a web-based survey on their political attitudes. The American flag was present in the corner of the screen for half the sample. Prior research has suggested that exposure to the American flag tends momentarily to bring to mind feelings of nationalism, concerns about security, and so on, that are most associated with the platform of the Republican Party – and the study did indeed show a shift to the right in people’s political attitudes when the flag was present. Such findings are interesting in themselves – further evidence that we attempt continuously to construct our preferences to fit the thoughts that happen to be splashing through our stream of consciousness.

Yet one might expect such effects to be short-lived. Astonishingly, though, when the Cornell team returned to their sample after they had voted later, the people presented with the US flag while answering part of the original survey were significantly more likely to have backed the Republican Party. The brief presence of the American flag in an internet survey had significantly shifted actual voting behaviour, a full eight months later! But how can this possibly be right? After all, American voters are continuously exposed to the US flag – on buildings, billboards, on neighbours’ flagpoles. Among all these hundreds of flags, surely just one more could not have tipped the balance to the Republicans. If it could, and if each flag-exposure is nudging people relentlessly to the right, then the entire political battleground in the US should surely be concerned with little more than – for the Republicans’ electioneering – covering every available surface in the Stars and Stripes; and for the Democrats, discreetly blocking them from view.

In my opinion, the correct interpretation of this study is very different, and far more interesting. Exposure to the flag has an instantaneous, although limited, impact on political attitudes; and, no doubt, this impact will rapidly be overwritten by the myriad other stimuli that jostle for attention. But if you see a flag while filling in a political survey, then the flag will, of course, affect your answers in the survey – and, indeed, this is just what the researchers found. But now memory traces have been laid down which have the potential to have a long-lasting effect on behaviour. To the extent that I later recall that, when contemplating my political views, I previously found myself leaning to the right, I am a little more likely to lean to the right in future. To make the most sense of my own behaviour, I will aim to think and act as I did before.

CHOOSING AND REJECTING

Suppose that we try, despite everything, to hold onto the idea that deep down we have stable, pre-formed preferences, even if they are a bit ‘wobbly’. Here is what sounds like a foolproof way to find out whether, for example, I prefer apples to oranges. Just offer me either an apple or an orange, on many occasions, and tot up which one I choose more often. That, surely, must be the fruit I prefer. And here is another apparently foolproof test: offer me an either an apple or an orange, and ask me to reject one (and hence keep the other). Now we tot up which option I reject less: that, surely, must be the fruit I prefer, mustn’t it? It would be ridiculous to choose mostly apples in the first case (indicating that I prefer apples); and mostly to reject apples in the second case (indicating that I prefer oranges). Consistently deciding to choose, but also to reject, the very same thing seems to make a nonsense of the very idea of preference.

Yet remarkably, psychologists Eldar Shafir and Amos Tversky found that this paradoxical pattern does indeed occur. They asked people to decide between extreme options (with both very good and very bad features) and neutral options (where all the features were middling).7 In one study, for example, people imagined making custody decisions between a ‘parent-of-extremes’ (good : very close relationship with the child, extremely active social life; above-average income; bad : lots of work-related travel, minor health problems) and a ‘typical parent’ (reasonable rapport with the child, relatively stable social life, and average income, working hours and health). In Shafir and Tversky’s experiment, when asked to choose which parent should be awarded custody, people selected the parent-of-extremes most of the time. But when asked to choose which parent should be denied custody, they also selected the parent-of-extremes most of the time! And this general pattern was followed across many studies: when asked to choose an option, people selected the ‘mix-of-extremes’ more often than the ‘average’. Yet when asked to reject an option, they also chose the ‘mix-of-extremes’ more often than the ‘average’. Surely people can’t think that the very same parent is both the best option and the worst option.

What is going on here? Shafir and Tversky argued that when we make choices, we are not ‘expressing’ a pre-existing preference at all; indeed, they would argue that there are no such preferences. What we are doing instead is improvising – making up our preferences as we go along. Improvising can take many forms – for example, we may be influenced by what we normally do, or what other people do, as we will see below. But one natural thing to do, in order to come up with a decision, is to scramble together some reasons for or against one option or another. But which do we focus on: reasons for or against? Shafir and Tversky argued this positive or negative focus is influenced by how the decision is described.

If we are asked to choose an option, we mostly focus on reasons for choosing one thing or another: and these reasons will tend to be positive reasons in favour of one option or the other. The extreme option has the most powerful positive reasons (e.g. a very close relationship with the child), so it wins out.

If, on the other hand, we are asked to reject one of the available options, then we search for negative reasons, which might rule out one option or the other. And the extreme option also has the most powerful negative reasons (e.g. lots of work-related travel). So now the extreme option loses out.

My colleagues Konstantinos Tsetsos, Marius Usher and I decided to look at this strange phenomenon – of choosing and rejecting the very same thing – in a highly controlled setting.8 The participants in our experiment had to choose between gambles. In each trial, a gamble would produce a number, corresponding to a monetary reward. People saw the kinds of rewards generated by a gamble over many trials, before deciding whether to select it – a bit like looking over another player’s shoulder as they play a slot machine, before deciding whether to take the plunge oneself. As it happens, people were able to see two or three gambles being played out on a computer screen in each trial – they saw ‘streams’ of numbers at different locations. The question for the players in our experiments was: which type of gamble – which stream of numbers – should they choose?

People watched sequences of numbers representing the possible outcomes of gambles, corresponding to the rectangular boxes. The gambles either had a relatively broad range of outcomes (the black bell curve in the upper row of Figure 27) or a narrow range of outcomes (the grey bell curve in Figure 27). The average pay-off for both types of gamble was exactly the same. So which gamble did people prefer? If people were asked to select either a broad and narrow gamble, then, we suggested, they might focus on positive reasons for selection – that is, on ‘big wins’. If so, they might prefer the broad gamble – in economic terminology, this is known as ‘risk-seeking’ behaviour (top left of Figure 27). But if people were asked to eliminate a broad or narrow gamble, then they might focus on reasons for rejection – i.e. on big losses. But the broad gamble also has the greatest number of big losses, so now that very same option might be rejected – this is known as ‘risk-averse’ behaviour. And, indeed, this is precisely how people behave (lower panel of Figure 27). People were initially presented with three gambles (one broad, and two narrow), which they observed over many trials; they were then asked to eliminate one of the gambles (lower left panel); then they were exposed to further samples from the two remaining gambles, and asked which one of these they would like to choose. As expected, the typical pattern of results was that people were especially likely to reject the broad gamble, more than either of the narrow gambles, at the first stage, but at the second stage they were more likely to choose a broad gamble (which was deviously added back in by us, even though it had initially been rejected). So at one moment people shy away from risk; yet at the next moment they embrace it. This makes no sense if we make our choices by referring to some inner oracle, but it makes perfect sense if we are improvising: conjuring up reasons, in the moment, to justify one choice or another.

Choosing and rejecting the same thing seems peculiar. But it is hardly an isolated incident. Indeed, entire fields of research, including Judgement and Decision-Making, Behavioural Economics, and large areas of Social Cognition have found countless examples of such inconsistencies.10 Ask the same question, probe the same attitude, or present the same choice in different ways and, almost invariably, people provide a different answer. Take our attitude to risk. We just noted that people are risk-seeking when deciding which of two gambles to choose, but risk-averse when deciding which of two gambles to reject – using a particular way of presenting the gambles as streams of numbers. But if we just ask people to choose gambles based on descriptions (e.g. a 50 per cent chance of £100 compared to a certain chance of £50), then people are mostly risk-averse. If we describe the gambles in terms of losses not gains, people typically become risk-seeking. If the gambles are ‘scaled down’ so that the chances of winning big (or losing big) are tiny, then things flip again: people become risk-seeking for a tiny chance of a big win (and therefore like to play lotteries), but risk-averse for a tiny chance of a big loss (and therefore buy insurance).

And it gets worse! People make wildly different choices when the same financial risk is described in a variety of superficially different ways (in terms of losses, gains, investments, gambling, etc.).11 And when we compare risk attitudes for money, health, dangerous sports, and so on, these also turn out to be only weakly related.12 To a good approximation, every new variation on the ‘same’ question gets us a systematically different answer – the brain conjures up a new ‘story’ each time; and if we prod the storyteller in a slightly different way, the story will, more than likely, be a little altered.13

If these variations were not the products of creative licence, but merely wobbly measurements, then taking more and more measurements and triangulating them carefully would eventually produce a consistent answer. But the variations in the story are systematic – so that no amount of measuring and re-measuring is going to help. The problem with measuring risk preferences is not that measurement is difficult and inaccurate; it is that there are no risk preferences to measure – there is simply no answer to how, ‘deep down’, we wish to balance risk and reward. And, while we’re at it, the same goes for the way people trade off the present against the future; how altruistic we are and to whom; how far we display prejudice on gender or race, and so on.

If mental depth is an illusion, this is, of course, just what we should expect. Pre-formed beliefs, desires, motives, attitudes to risk lurking in our hidden inner depths are a fiction: we improvise our behaviour to deal with the challenges of the moment rather than to express our inner self. So there is no point wondering which way of asking the question (which would you like to choose, which would you like to reject) will tell us what people really want. There are endless possible questions, and limitless possible answers. If the mind is flat, there can be no method, whether involving market research, hypnosis, psychotherapy or brain scanning that can conceivably answer this question, not because our mental motives, desires and preferences are impenetrable, but because they don’t exist.