THE IMMEDIATE CHALLENGE FOR THE DOGES AFTER 1204 was to establish control over their new empire. In Constantinople itself the authority exercised in the city by Enrico Dandolo in the months before his death was passed through election to one Marino Zeno, who arrogantly announced that he was ‘lord of a quarter plus half a quarter of the Roman empire’ and took on the title of podestà (the word means ‘one who holds power’; often, in Italian cities, an elected chief magistrate). There was even talk of moving the capital of the Venetian empire to Constantinople. These ambitions were quashed by the emergence of a tough doge, Pietro Ziani (r. 1205–29), who moved quickly to reassert his own authority in Venice. He made it clear that the lands acquired by Enrico Dandolo from the Byzantine empire, certainly those close to Venice, were under his direct control, not that of the podestà, and that Venetians could take over the newly acquired territories without reference to the podestà. Ziani then further announced that it was he, not Zeno, who was the lord of the Roman empire. In 1207 Zeno was replaced by a podestà sent out from Venice and this became the usual procedure. Not that the podestàe were without power. One of them, Giacomo Tiepolo, even exploited the weakness of the Latin emperor of his time in order to make his own treaties with surrounding states and then used a second term as podestà (1224–9) as a stepping stone to the office of doge.

Once the doges had asserted their status as ‘lord of a quarter plus half a quarter of the Roman empire’ we find them linking themselves back to the Byzantine imperial past, even to the heyday of Rome. Pietro Ziani, the doge who had stamped his authority on the podestà, was praised on his tomb as ‘rich, honest, patient and in all things straightforward. None could be his equal amongst the high-born and wise. Not even Caesar and Vespasian when they were alive.’ Julius Caesar, the conqueror of Gaul in the first century BC and later dictator of Rome, needs no introduction. The emperor Vespasian (r. AD 69–79) had restored order to the empire after the reign of Nero and commissioned the building of the Colosseum. Conquest, stability, building: these were the ‘Roman’ attributes of Ziani. It was in his reign that work to finalize the form of the Piazza San Marco and complete the transformation of the façade of St Mark’s, described earlier, was begun.

Ziani’s claim that the doges had supplanted the emperors may be seen reflected in his embellishment of the Palo d’Oro, one of the great treasures of St Mark’s. The Palo d’Oro is an altar screen which had been commissioned by an earlier doge, Ordelafo Falier (r. 1101–18), from workshops in Constantinople. As originally made, it had three central panels on which portraits of Alexius I, the emperor of the time, and his wife Eirene, flanked the Virgin Mary at prayer, a standard Byzantine image. In this form it was installed by the altar in St Mark’s. In other words, the supremacy of the Byzantine emperor was, in the early twelfth century, still being respected in the doge’s own chapel in Venice. When a mass of jewels and enamels arrived back in Venice among the treasures of the sack of 1204, it was decided to fit them into the Palo d’Oro. Ziani asked the procurator of St Mark’s, one Angelo Falier, who was a descendant of Doge Ordelafo, to oversee the task, and Falier was arrogant enough to discard the portrait of Alexius I and replace it with one of his ancestor – while retaining all the imperial regalia that had been shown on the original! In effect, a doge, albeit in this case one long dead, was transformed into a Byzantine emperor.

It was only a matter of time before the same transformation was effected of a living doge, and sure enough this occurred in 1284, when Venice decided to mint its own gold ducats. On these the doge – another Dandolo, Giovanni – was shown on the coin receiving an imperial banner just as the emperor was on Byzantine coins. By this period the doge also dressed himself in a costume which drew on Byzantine precedents, notably red stockings, black shoes encrusted in diamonds and a fur-lined mantle.

As we have seen, the coronation rites of the Byzantine emperors stressed that they were the favoured of God, who, the fiction went, had chosen the emperor as his representative on earth. We find Enrico Dandolo making the same claim for himself. One chronicle records his words: ‘And God through his mercy and divine grace illuminates the mind of each doge, chief and rector of Venice, so that his state may always grow and expand [God had done Dandolo proud in this respect!], and so that each may accordingly support and govern and preserve his state.’ Martino da Canal reproduces the acclamation with which the doge, in this case Reniero Zeno (r. 1253–68), was met in St Mark’s when he entered on a feast day: ‘Let Christ be victorious, let Christ rule, let Christ reign; to our Lord Reniero Zeno, by the grace of God illustrious Doge of Venice, Dalmatia and Croatia, conqueror of a fourth part and half a fourth part of all the Roman empire, salvation, honour, life and victory, let Christ be victorious, let Christ rule, let Christ reign.’ This can be compared to the acclamation with which the Byzantine emperor Leo I was greeted on his succession in 457: ‘Give ear, oh God, we call on you. Hear us, oh God. To Leo, life. Give ear, oh God. Leo shall rule. Oh God who loves mankind, the common people ask for Leo as emperor, the army asks for Leo as emperor … Let Leo come, he, the ornament of all, Leo shall rule, he, the good of all. Give ear, oh Lord, we call on you.’ In both cases the acclamation begins and ends with acknowledgement of God or Christ, with specific epithets applied to the emperor in between. In Constantinople the emperors had signified their place as representative of Christ by carrying a white paschal candle in the Easter procession. According to Martino da Canal, the doges adopted the same practice for the Easter procession in Piazza San Marco.

If one looks at the burial places of Dandolo’s successors one can see how they developed their ‘divine’ status. As Debra Pincus has shown in her study of the tombs of the doges, the creation of an opulent tomb became a prominent feature of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, and their decoration includes echoes of the Byzantine emperors’ burial monuments. The tomb of Doge Giacomo Tiepolo, the former podestà, survives on the outside wall of the grand Dominican Church of Santi Giovanni e Paolo in Venice. The lid, apparently from an original sarcophagus of the fifth century, is crafted in a style associated with Ravenna, to where the last of the western Roman emperors withdrew their court in the fifth century. Prominent on it is a jewelled cross which stands on steps. The emperor Theodosius (AD 379–95) had placed a similar cross on the site of the crucifixion in Jerusalem, and it is a type found on Byzantine coins. So the cross here is a symbol not just of Christianity but of the Christian emperor. Tiepolo’s successors, Doge Marino Morosini (d. 1253) and doge Reniero Zeno (d. 1268), were also buried in antique tombs, ‘which encase the body of the doge in images of Christ as ruler’, as Debra Pincus puts it. Pincus has also shown how the frontal reliefs of Morosini’s tomb, believed to be contemporary with his death, appear to have been influenced by those on one of the most prestigious of all Roman monuments, the triumphal Arch of Constantine in Rome. Another feature of these doges’ reigns which enhanced their ‘imperial’ status was the formation of marriage alliances between their families and neighbouring royal families: the family of Pietro Ziani with the king of Sicily, that of Giacomo Tiepolo with the king of Rascia in the Balkans, and that of Marino Morosini with the kings of Hungary.

Of course, the most prestigious burial place had to be St Mark’s. Marino Morosini was the first doge to be buried there, but his tomb was in the atrium, the colonnade at the entrance: not a very privileged area. Doge Giovanni Soranzo (r. 1312–28) was given a much more prominent position, in the baptistery. At the time there was an entrance to the basilica here from the Piazzetta, so the tomb would have been seen by anyone entering by this door. It was (and remains) a particularly fine tomb of coloured marble, set in a wall of marble slabs. Doge Andrea Dandolo (r. 1342–54) attempted to go even further. As a procurator of the basilica he had directed restoration work on the interior, and it was he who, in his capacity as procurator, had allowed Soranzo’s tomb to be placed in the baptistery. When doge himself, he added a great crucifixion mosaic above the baptistery altar; he also built a new chapel, San Isidore, and remounted the Palo d’Oro in even greater splendour – in the form in which it survives today. He had hoped that his benefactions would be sufficient to earn him a burial place in the chapel of St John the Evangelist, close to the central dome of the basilica – but his ambitions had risen too far. After his death the procurators refused his request and his body ended up, like Soranzo’s, in the baptistery.

So, in the Venice of the thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries we find the doges consciously associating themselves both with symbols of Byzantine imperial power and directly with the divine, as the emperors had. They also took trouble to show themselves off to their subjects – and where better to do so than the loggia of St Mark’s? There is a description of the scene at the election of doge Reniero Zeno in 1253 in Martino da Canal’s Estoires de Venise, with the newly elected doge and his entourage of nobles standing on the loggia and his subjects taking part in a brightly coloured parade below.

We know, too, that in the thirteenth century the coronation ceremony included a presentation of the doge to the people with the words: ‘This is your doge if he pleases you’ – a procedure reminiscent of imperial coronations in Constantinople – and this again presumably took place on the loggia. Indeed, Canal goes on to describe the processions which ‘Monsignor the Doge makes upon high festivals’, and these always end with a mass after which the doge shows himself to the people from the loggia.

From 1364 we have a much more explicit description of the doge acting in a ceremonial role on the loggia. It comes in a letter written by Petrarch, the greatest scholar of his age, who that year had been welcomed to Venice and given a house there. This letter is also important in providing the first description of the horses in situ. Petrarch is up on the loggia beside them with the doge – he was actually given the most honoured position on the ruler’s right (the position given to Mark in relation to Christ in the mosaics that had once been behind the loggia). He writes:

Now the Doge himself with a vast crowd of noblemen had taken his place at the very front of the temple above its entrance, the place where those four bronze and gilt horses, the work of some ancient and famous artists unknown to us, stand as if alive, seeming to neigh from on high and paw with their feet. Where he stood on this marble platform it had been arranged that all should be under his feet, and multicoloured awnings were hung everywhere as protection against the heat and glare of the setting summer sun.

The occasion was a victory celebration, applauding the defeat of a serious revolt in Crete, and one is reminded of the similar use of the hippodrome in Constantinople by the twelfth century. The emperor Manuel, for instance, is described as returning to Constantinople in 1150 after a major victory over the Serbs to be ‘acclaimed’ in the hippodrome ‘by the people and the entire senate; the recipient of applause and praise, he reviewed the horse races and spectacles.’ Much the same seems to have happened in the Piazza on this occasion. Petrarch goes on: ‘When religion had amply received its due, everyone turned to games and spectacles.’ Among the races were ones on horseback; there were also tournaments and other contests and festivities. Just as in a hippodrome, there was a densely packed mass of spectators.

Petrarch describes the doge standing on the loggia alongside the horses. A comparison can be made with a relief of the Byzantine emperor Theodosius (AD 379–95), which shows him presiding over the hippodrome in Constantinople. In each case the emperor/doge stood over an arch. (The Art Archive)

Down below [in the Piazza] there was not a vacant inch; as the saying goes, a grain of millet could not have fallen to earth. The great square, the church itself, the towers, roofs, porches, windows were not so much filled as jammed with spectators … On the right a great wooden grandstand had been hastily erected for this purpose only. There sat four hundred young women of the flower of the nobility, very beautiful and splendidly dressed.

It appears, then, that the doges used the Piazza San Marco as a ceremonial arena much as the emperors had come to use the hippodrome in Constantinople. There is even intriguing evidence, although from a much later date, that the processions which came to take up such a large part of Venetian life could be linked back to Byzantine ceremonial ritual. One of the most celebrated of Venetian paintings, now in the Accademia in the city, is Gentile Bellini’s Procession in the Piazza San Marco, which shows the festivities of 25 April, the feast day of St Mark himself, in 1496. In the foreground one of the city’s scuole (confraternities of citizens set up to dispense charity), that of San Giovanni Evangelista, carries its relic of the True Cross. The painting was commissioned, in fact, by the scuola itself as part of a cycle which celebrated their important relic and the miracles it had effected. Before and behind the relic walk white-robed officials carrying white candles. A man whose son has been healed by the cross kneels behind it. On the right the doge and city dignitaries are assembled while a mass of white-mantled citizens stand in ranks on the left. Behind the crowds St Mark’s is shown in all its radiant glory, and the horses stand out in this earliest painting to show them on the loggia.

Looking at the painting, one is reminded of a description of the founding of Constantinople given in a Byzantine document, the Chronicon Paschale:

He [Constantine] made for himself another gilded monument of wood, one bearing in his right hand a Tyche of the same city also gilded, and commanded that on the same day of the anniversary chariot races, the same monument of wood should enter [the hippodrome], escorted by the troops in [white] mantles and slippers, all holding white candles; the carriage should proceed around the further turning post and come to the arena opposite the imperial box; and the emperor of the day should rise and do obeisance to the monuments of the same emperor Constantine and this Tyche of the city.

Is what we see in Bellini’s picture a Byzantine ritual adapted to serve the needs of Constantinople, with the wood of the True Cross in its gilded reliquary replacing ‘the gilded monument of wood’? Certainly the candles and the white mantles appear to link the two – one even has a peep of the white slippers of one or two of Bellini’s participants! (White was always the colour in which groups clothed themselves in both Greek and Roman processions. In Venice in this period white was a mark of status because it signified detachment from the workaday world where clothes were easily soiled.) It is possible that the Venetians had deliberately incorporated the foundation ceremony of Constantinople – which, as we have seen, took place in the hippodrome – into the feast-day celebrations of the patron saint of Venice.

Procession in the Piazza San Marco, 1496, by Gentile Bellini. The first surviving painting to show the horses in situ. The procession itself echoes those described in the early Byzantine empire. (Academia Venezia/Scala)

So we come to the possibility that one of the reasons why the horses were placed where they were was because they reinforced the idea of the Piazza as a ceremonial hippodrome. Of course, there is no suggestion that chariot races were held in the Piazza (although there is an account of a festival there in 1413 in which over four hundred horsemen took part). In any case, by this time the hippodrome in Constantinople, which many Venetians would have seen, had almost lost its function as an arena for races and was predominantly a ceremonial venue.

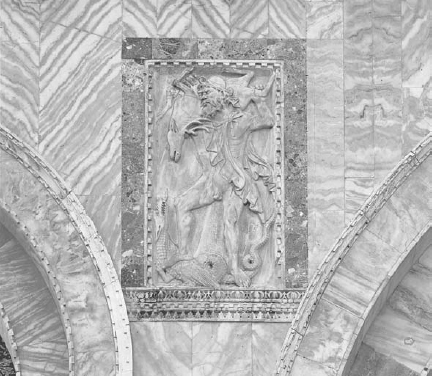

For further evidence in favour of this idea we need to return to the two reliefs of Hercules which, as noted in chapter 7, were placed on the western façade of St Mark’s, one at either end. As with the two other pairs of reliefs between them, one is from Constantinople (dated as early as the fifth century) and the other carved in Venice in the thirteenth century. The older relief shows Hercules in one of his most famous labours, the killing of the Erymanthean Boar. The other portrays the hero having completed two labours, the killings of the Cerynean Hind and the Lernean Hydra. The San Alipio mosaic shows them in place so they must have been erected before 1267.

Two reliefs of Hercules known to have been placed on the façade of St Mark’s by the 1260s. The one showing Hercules carrying the Erymanthean Boar is antique, the other, showing the killing of the Cerynean Hind and the Lernean Hydra, is from the thirteenth century. Hercules was the patron of the hippodrome and it is arguable that the placing of the reliefs was intended to reinforce the idea that here, symbolically, was a ceremonial hippodrome. (S. Marco, Venezia/Scala)

The relief with the Erymanthean Boar closely follows earlier classical models – a third-century sarcophagus found in Rome has a relief almost identical to it – and when it was put in place on the façade it was given an antique framing with dentils. It was as if the antiquity of the relief were being deliberately highlighted. The sculptor of the ‘new’ Hercules copied the pose of the other relief and carved the dead hind and the hydra around it in a way not known from earlier reliefs. He obviously had no classical example to work from. The setting of Hercules here, alongside four religious reliefs on the façade of a Christian church, seems bizarre. However, the commentators on these reliefs, notably Otto Demus, the great authority on the fabric of St Mark’s, explain that Hercules could be used in Christian contexts. As a symbol of strength he could be linked to Samson, even to the Saviour himself ‘conquering evil and saving the souls of the faithful’. Moreover, the earliest political centre in the lagoon, Eraclea, was named after him – perhaps echoing legends that Hercules had been the tribal hero of the Veneti, the original tribe in the area – and other churches in the region have Hercules represented on them.

There is, however, another possibility. As we have seen in previous chapters, in both the Greek and the Roman world Hercules was associated, among other things, with chariot racing and the hippodrome. Could it be that these two reliefs were placed on the façade roughly at the same time as the horses in order to emphasize that the Piazza was a symbolic hippodrome? The evidence cannot be conclusive, but it reinforces rather than excludes the possibility.

If the horses were associated with the assertion of imperial prestige, is there a particular doge or event before 1267 to which their elevation on to the loggia can be related? There is no mention of the horses on the loggia at the coronation of Zeno in 1253, although this is no evidence in itself that they were not in place. We have only the terminal date of the San Alipio mosaic in 1267, when Zeno was still doge. Zeno’s reign marked the zenith of imperial glamour. He was an immensely rich man and fond of displaying himself before his people in gold and jewels in a manner reminiscent of Constantine. During the Easter season he processed through the Piazza each Sunday dressed in all his regalia; the season ended, on Ascension Day, with the grand ceremony of La Sensa, in which the doge and his retinue took to their barges and at the entrance to the lagoon from the open sea cast a gold ring into the water to symbolize Venice’s ‘marriage’ to the sea. This ceremony, perhaps the most hallowed in the Venetian calendar, reached its most elaborate and opulent form in his reign.

The horses could have been put in place simply as part of Zeno’s programme of imperial display; but if one is looking for another, more immediate catalyst for the elevation one could also see it as a response to a political crisis. There was good reason why, in the mid-1260s, Venice should have felt the need to reassert its imperial pride through a dramatic reminder of its earlier humiliation of Constantinople. These were years when, despite the glamour of Zeno’s dogeship, things were turning sour for Venice. In 1259 the city’s confidence had been undermined when a new French king of Sicily had annexed Corfu and parts of the Dalmatian coast, infringing Venice’s control of the Adriatic. Such intrusions always made the city edgy. Worse was to come. In 1261 a Greek emperor, Michael Palaiologos, regained control of Constantinople with the help of Genoa, Venice’s ancient rival. The Venetian quarter was put to the flames, and there are harrowing stories of its inhabitants, many of whom had known no other home, crowding down to the shore where they were evacuated by the thirty Venetian ships in port. The last podestà, Marco Gradenigo, left with them. Zeno continued to use his title of ‘lord of quarter and half a quarter of the Roman empire’ (he pointedly wrote to the new emperor Michael as ‘emperor of the Greeks’ not ‘of the Romans’, the ancient title which Michael might have hoped for) but it was a hollow one. In return for their help, the Genoans had been granted rights to have a colony at Galata, just across the Golden Horn from Constantinople, and they retained these rights even after Venice and the empire eventually made peace in 1268. The Venetians, although they saved many of their trading posts in the eastern Mediterranean, never recovered their favoured position within the Byzantine capital. At home, meanwhile, the strain of defending what remained of the empire is known to have led to unrest and food riots.

It may well have been during this period of crisis that Zeno decided to use the horses specifically as propaganda to revive the confidence of his city. He was a proud and determined man, sensitive to the prestige of Venice. When in 1265 the new emperor offered him a peace treaty that would have once more granted the Venetians a quarter in Constantinople and freedom to settle in the Black Sea, he declared himself offended by its tone which, he said, was too reminiscent of earlier treaties in which Venice had acquiesced in the supremacy of the Byzantines. So he turned it down. If a flamboyant gesture of Venice’s pride were now needed, what better than to haul the horses up on to the loggia where they could be seen by all and act as a reminder that the doges were still emperors in spirit? With the doges identifying themselves so closely with Christ they could be presented as ‘the quadriga of the lord’ and yet still function as the presiding symbol of an imperial hippodrome. The Venetians were adept at creating different layers of meaning in their monuments. With the horses in place, the final embellishment of the Piazza, its herringbone paving, which we know was laid down in 1266, was now put in hand.

The association with the Byzantine emperors, so carefully cultivated by the doges, did not last; indeed, their claim to any kind of imperial grandeur was soon under threat. By the end of the thirteenth century Venice had lost its position in Constantinople and the Byzantine empire had revived itself for a final period of independence before its extinction at the hands of the Ottoman Turks in 1453. Old rivals such as Genoa and Pisa, as well as newly emerging Italian cities such as Bologna and Ancona, were threatening Venetian trade. Even Venice’s control over the Adriatic, the sea it claimed as its own, was threatened. In 1273 the Bolognans forced Venice to allow them to import corn directly through the Adriatic ports, so depriving the city of the trade. Conflict with Genoa simmered on through the 1290s. In 1311 Zara, encouraged by the Hungarians, revolted. In Venice itself there were renewed food shortages and currency problems.

As unrest grew, in 1297 the Great Council was reorganized through the law of the Serrata, with the aim of creating a more stable form of government. While the Serrata, the ‘cutting-off’, would eventually confine government to a finite circle of nobility, in the short term the act allowed more commoners to be included in the nobility, and others were incorporated in the decades that followed. Any immediate hope that this measure would bring calm was dashed by continuing popular disaffection and disorder, in which even the position of doge was challenged. In 1310 Doge Pietro Gradenigo (r. 1289–1311) was the focus of an assassination attempt which, although led by nobles, enjoyed wider support; and when he died (of natural causes, in the end) he could not even have a public burial because it was feared that his corpse would be set upon and desecrated. The secretive Council of Ten, which had the power to order the killing of those suspected of crimes, was set up in 1310 and became a fixed feature of the political system.

This was a different world from that of 1204; even if St Mark’s had carried with it connotations of the hippodrome in the thirteenth century, these would have disappeared as popular involvement in government waned and the role of the doge diminished. At the death of each doge a committee met to draw up the coronation oath of his successor, and a study of these shows that with each reign the powers of the doge became more limited. Marriage alliances with European royal families, for instance, were forbidden. No doge was buried in St Mark’s after 1354. Up to the 1380s one finds that several ancient families – the Dandolos, the Morosinis, the Zenos and the Faliers – provided among them a succession of doges; after this date these families fade from prominence and a number of new ones, some of them having gained their high status through recent military successes, achieve prominence.

The rituals surrounding the election and coronation of the doge evolved new forms as he became increasingly subject to the Grand Council. By the fifteenth century the doge was elected by an intricate system in which only the nobility played a part, and even the presentation of the doge before his people for formal approval had vanished. His election was now confirmed inside St Mark’s by the leader of the forty-one electing nobles. The doge then processed outside the basilica and even though he was elevated above the people in the Piazza on a wooden platform, no part of the ceremony involved his asking them for their support. It was simply assumed. The procession now moved to the Doge’s Palace and by the end of the fifteenth century it was here that the formal coronation took place. What had originally been a rather secret, private building had been transformed by an opulent entrance near San Marco, the Porta della Carta (built 1438–42), and the Scala dei Giganti (completed about 1490), a grand ceremonial staircase which led from the inner court to the first floor. The new doge would ascend this and then present himself to the crowds from a balcony inside the palace courtyard. So by this time one has to accept that the Piazza San Marco was no longer seen as fulfilling the ‘coronation’ functions of a hippodrome. Gone were the days when the doges were ‘emperors’ acclaimed by the people. They were now servants of the nobility.