The present chapter is to ponder a two-part question. Korean historiography overwhelmingly depicts the Japanese era darkly, as the death of “old Korea,” perhaps even of Korean identity itself. So, the ἀrst part of the question: to what extent should we see death (eclipse, distortion, erasure) as historiographical vis-à-vis actual? Stated more bluntly, is the erasure of old Korea merely a product of more modern, nationalist historians, politicians, and ideologues, or did it actually happen and how much? The second part of the question is this: to what extent was erasure, variously historiographic and actual, really part of interweaving, mutually opposed, yet thereby mutually invigorating understandings of modernity, and therefore also enabling? Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak (1996, 19) writes of colonization as providing an “enabling violence” or “enabling violation” that can free or enrich the discourse of culture and indeed of nation. To what extent is the Japanese era to be seen as containing seeds for the much later outbursts of new creativity in more recent times—the economic “Miracle of the Han,” the new avant-garde, the K-wave? (Chapter 3 will need to take this question further, to ask how the further tragedies of the Korean War and the long military dictatorship were also destructive of the past yet also enabling of later creativity.)

The question can be posed more bluntly. There are continual charges that colonization erased Korean culture; there was certainly erasure written on the fabric of the city of Seoul. There is also a more recent historiography (chapter 1) that would assert that colonization 24also brought enrichment (multiplicity, otherness) to the urban culture of Seoul, again written upon the city. So, in understanding Seoul there is a terrible tension, almost a dialectic, between erasure and enrichment. How are conflicting historiographies to be negotiated and the city thereby to be read?

The present chapter will be in four parts. The ἀrst will take the form of a selective history to the beginning of the Japanese era, with the second then extending the account to the end of that era. Both parts are to trace the political and social trajectory of Korea but also the evolution of the extraordinary diversity of ideologies, ideas, and cultural resources with which Koreans were later to confront the post-1945 world and which persist, even further enriched, into the present. Although reading as a form of history, the focus is on the geography and spaces of the city. Part 3 of the chapter deals more explicitly with the question raised above: in what ways might the Japanese intervention be seen as eroding—even erasing—old culture and identity and in what ways might it have been enabling of a new Korean modernity? Part 4 then deals with that further question of the extent to which erasure was actual and to what extent a product of modern Korean historiography—has the outrage been enhanced in some distorted national remembering? In that sense, part 4 returns to themes of chapter 1.

A note on method: to repeat from the preface, this and following chapters are based on an interweaving of themes and ideas—historiography, architecture, urban form, literature, ἀlm, religion, television, and popular culture. The purpose is to invoke reflection on challenging juxtapositions, throwing accepted ideas and their supposed underlying wisdom into doubt, thereby to see the city and its story anew.

Part 1

SEOUL AND KOREA BEFORE COLONIZATION

Ancient Korea is essential to any engagement with present Korea, and thereby Seoul, in three senses. First, it presents contested origins to legitimize North versus South, and Korea versus Japan, into the present day. Second, it provides the wish images in which modern Seoul’s past would be imagined and its present identity would be socially constructed, both physically and in cyberspace.1 Third, the old kingdoms were theaters of beliefs and ideologies, variously competing and overlapping, contested and hybridizing, contradictory yet coinciding, that 25still run through the culture of the present. They account in large part for the extraordinary intellectual vigor of the South and much of the vibrancy of Seoul.

Korea in antiquity was in some sense a peripheral kingdom, on the edge of a Sino-centric world. With its proximity to China, it came to share the latter’s Daoist and Confucian traditions; in the second century BCE it had adopted the Chinese writing system, and in the fourth century CE, its Buddhism. Like the Japanese, Vietnamese, Tibetans, and diverse Central Asian peoples in the orbit of ancient China, the Koreans regarded China as the apex of human civilization and were seemingly happy to adapt desirable Chinese ways of doing things (Clark 2000, 4). Subsequently, the Korean language was codiἀed and given an alphabetical structure in the fifteenth century, in part to differentiate the Koreans from the Chinese in the perennial search for clarity of identity through language (see chapter 1, in relation to the Benedict Anderson argument). In ancient times Korea was a fulcrum for the transfer of continental culture to Japan, while also being periodically caught up in raiding parties and the resulting skirmishes with its island neighbors.

The foundational legend has the proto-Korean Gojoseon (ancient Joseon, Chõsen, or Chosun) kingdom founded in 2333 BCE by Dangun (Tan’gun), the Posterity of Heaven. Its capital may have been in Liaoning (in present-day China) but around 400 BCE moved to Pyongyang. In 108 BCE a Han Chinese invasion ended Gojoseon, and a succession of small states ensued until the emergence of the three kingdoms of Baekje, Koguryo, and Silla. The mountain-ringed valley of the Han River had been chosen for the capital of the southwestern Baekje (Paekche) kingdom around 18 BCE. While the Baekje capital was somewhat mobile, shifting between sites, all of these were within the region that would now be called Greater Seoul—Wiryeseong (present day Hanam), north and south of the Han River, and Bukhan in northwest Seoul (present-day Goyang). In present-day Seoul’s Pungnap-dong there is Pungnap-toseong, a flat earthen wall at the edge of the Han River, oval-shaped and with a circumference of some 3.5 kilometers. Based on research during the Japanese occupation, it is speculated that this structure was an element of Hanam Wiryeseong, the ἀrst capital of Baekje. A further, outlying fortress of the supposed Hanam Wiryeseong is Monchon-toseong, with its surviving earthen ramparts on the Olympic Park site. In the fourth century the somewhat putative kingdom of Baekje became a more full-fledged kingdom, acquiring Chinese culture and technology through contact with the Chinese southern dynasties; in turn, Japanese culture, art and language were strongly influenced by the kingdom of Baekje. 26

The relationship between Korea (speciἀcally Baekje) and Japan is contested. At the extreme there is the view of Korea as the onetime ruler of Japan and “the fount of all Japanese civilization” (Farris 1994, 24–25). Against that is the more modest claim that Baekje art “became the basis for the art of the [Japanese] Asuka period (about 552–644)” (Hatada 1969, 20); furthermore, Bruce Cumings (2005, 34) cites recent evidence, “weighed dispassionately,” that Japan obtained metals, metal technologies, military technology, and strategy from Korea.2 Cumings also notes speculations on Korean origins of Japan’s imperial house (33), suggesting that such speculations may account for Japanese reluctance to permit the archaeological opening of imperial tombs—what might they ἀnd? The embarrassment (for Japan) continued: as recently as the late 1500s and early 1600s, massive numbers of Korean potters were forcibly abducted to Japan to engineer the birth of the Japanese Imari porcelain tradition. The contested relationship might be seen as underlying, in part, a determination on the part of many Japanese in the twentieth century to suppress Korea and all memory of it. Yet there is also Everett Taylor Atkins’ (2010) counterobservation of the extent of Japanese commitment to Koreana and a view of Korea as what Japan may have lost in its headlong rush to modernity.

Three kingdoms vied for dominance in the Korean Peninsula and adjoining Manchuria in ancient times. Baekje was centered on the southwest of the peninsula, and Koguryo was in the north, branching far into Manchuria and what is now Paciἀc Russia; between these two was Silla.3 In the 660s Silla effected a uniἀcation of the peninsula, also becoming strongly allied with Tang China;4 in the ninth century Silla in turn collapsed to yield a multiplicity of states. Then, in 918, the Goryeo (Koryo, Korea) state was founded and the Han valley, locale of the erstwhile Baekje capital, continued as locale for the new capital, at Gaeseong or Songdo (now Kaesong in North Korea but on the border with South Korea and effectively within the broader Seoul region).5 In 1392 the Yi (or Chosun, Joseon, “Morning Calm”) dynasty replaced Goryeo through a largely bloodless coup. The choice of name represented a claim for both antiquity and authenticity, casting back to that imagined birth of the Korean nation in the third millennium BC when king Dangun had founded Old Chosun. With the new dynasty in 1392, Goryeo (Korea) would cease; the nation would proclaim return to its (Chosun) origins.

The post-1945 partitioning of the peninsula also partitioned its historiography. Both North and South would claim Old (and new) Chosun; the North would title the country Chosun, the South would take the more recent (1890s) Han’guk. From the Three Kingdoms period, the North conferred national legitimacy on Koguryo, with its legendary center in the sacred mountain Paektu, which also 27thereby became central to the founding myth of the Kim dynasty—Kim Jong-Il, we are told, was born there.6 The South, contrarily, claims Korea’s true descent to be through Silla, with its capital at Kyongju or Gyeongju (north of Busan). The presidents of South Korea from 1961 to 1996, both those elected and the dictators, came from this region; the ἀrst president, Syngman Rhee, had his legitimizing ideology located in Silla.7 It is Baekje that is omitted from these rival claims of origin—and, more vehemently, from Japanese claims.8

In August 1394 Taejo, founding monarch of the Yi (Chosun) dynasty, established Hanyang (the present Seoul) on the same site as two previous dynastic capitals but as an entirely new foundation. Ryu Jeh-hong (2004, 17) argues that Taejo, having established his dynasty by coup, needed to “denaturalize” (destroy) Gaeseong, the previous “naturalized” capital of the Goryeo dynasty, and then to invoke the already “naturalized” pungsu, the Korean geomancy, bringing its principles to determine both the location and geometry of the new capital. Lee Sang-hae (2000, 15) has outlined two principles of Hanyang’s (Seoul’s) planning. One lay in the doctrine derivable from pungsu, seen as an “image-text”:

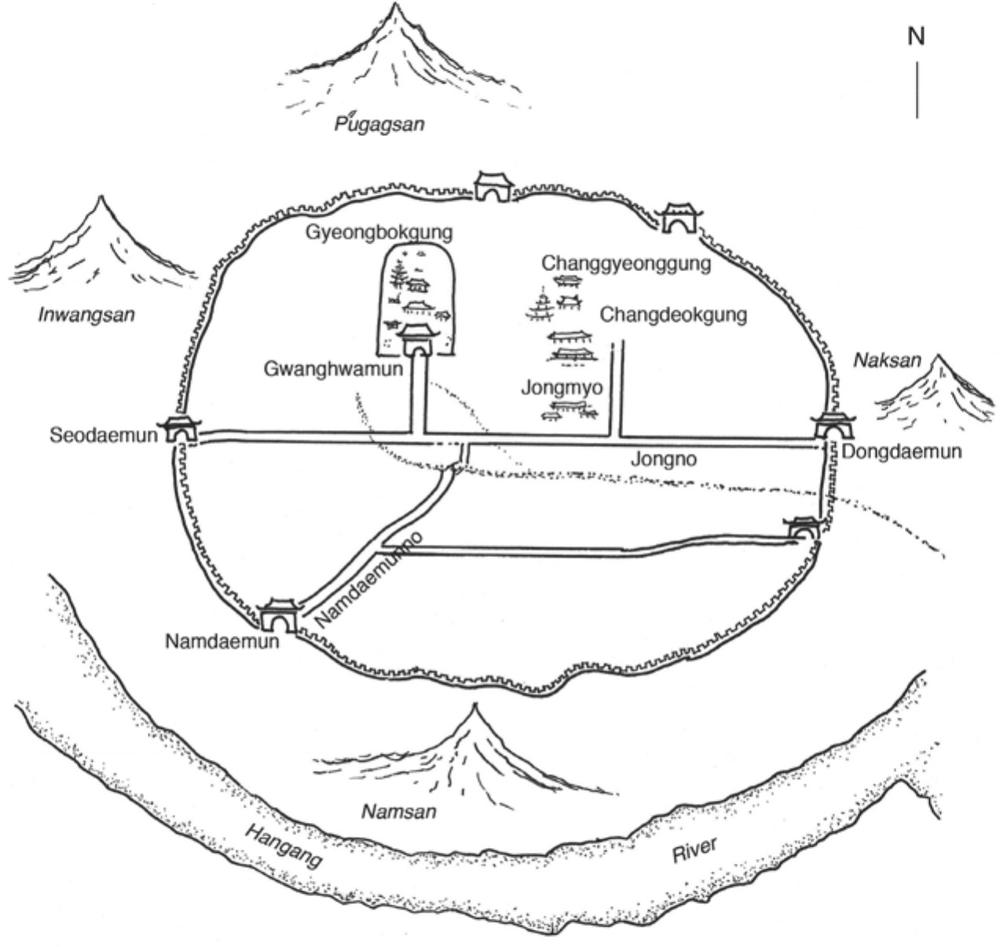

The name Hanyang is itself a reflection of its [pungsu] principles. In the theory of negative-positive (yin-yang in Chinese), yang denotes the sun ἀlled southern slope of a mountain overlooking its river to the south.9 Hanyang then means a site situated south of the North (pronounced “puk” in Korean) Mountain (pronounced “ak” in Korean), or Pukak [Pugak], and north of the Han River. In terms of geomantic conἀguration, the city occupied a valley encircled by a range of mountains: Pukak as the Principal Mountain; Namsan the Southern Mountain; Naksan the “Left Blue Dragon”; Inwangsan the “Right White Tiger.”10

The second principle flowed from the metaphysics of neo-Confucianism, whereby “the city was an instrument for implementing the ritual institutions, and the ἀrst order of its plan was the proper placement of guardian shrines of the state” (Lee Sang-hae 2000, 15).

The ἀrst decision facing the Chosun, in the context of this new orthodoxy, was the siting of the main royal palace, Gyeongbokgung Palace, in the north of the city but under the protecting south slope of Pugak, the North Mountain, which, however, was not visible from the palace due to an intervening mountain slope, but was majestically visible from the great north-south axis of Taepyeongno (now Sejongno, ἀgure 2.1). The city thereby gained the effect of legitimizing 28Taejo’s coup by naturalizing his palace. Jongmyo (Chongmyo), the royal ancestral temple, was to the east of the palace, and the shrine to the guardian spirits of land and crops to the west. The kingdom’s main administrative functions were located along the north-south Taepyeongno, which stretched from Gwanghwamun, the ceremonial gate to the palace, to Hwangtoyeon, an open plaza (Lee Sang-hae 2000, 14; Gelézeau 1997). Hanyang thereby became a “natural” city—nature and its spirits reigned (Ryu Jeh-hong 2004, 17).

FIGURE 2.1 The idealized city of 1394: four geomantic mountains, three main and three subsidiary gates, a discontinuous, bent axis (regularized in the Japanese era and renamed Sejongno in the present time), and palaces beneath the most sacred of the mountains, facing south. Source: based on Lee Ki-Suk (1979, 79–82); Kim Won (1981, 3–10); King (2008a); and Gelézeau (2014, 167).

The main gates to the city were to the east and the west, and, consequently, the main roads ran east-west. About six hundred meters south of Gwanghwamun, Taepyeongno was crossed by Jongno, the most important of these east-west roads, “the street of the bell” whose ringing would signify the opening and closing of the city gates, and the street of shops to serve the royal court and thereby the commercial and business street of the old city, a commercial preeminence that persists to the present day.11 North of Jongno were the residences of the aristocracy, to the south the plebeian districts. 29

While the north-south, east-west grid characterized the principal avenues of Hanyang, it did not have the same rigorous geometry that one would encounter in the Chinese cities, most notably in the Tang dynasty capital, Chang-an. The discontinuous Taepyeongno is one aberration; a stream running southeast from Kwanghwamun yielded the line of the diagonal Insadonggil; within its somewhat irregular grid squares, minor streets and lanes follow no discernible plan. The contrast between the processional avenues and the labyrinthine alleys behind them would appear to reflect an ancient tension between the display of power and the concealment of private space, a tension also evident in the Chinese metropolises—witness the tension between the gridded avenues of Beijing and the hidden hutongs (laneways) within the grid squares. (The ancient tension translates, in modern Seoul, into that between the grand corporate boulevards and the ordered arrays of seemingly identical apartment blocks, on the one hand, and a more chaotic, labyrinthine, disordered space of the “back streets,” alleys, and “real life” on the other. It is the dichotomy of morphologies introduced in chapter 1, ἀgure 1.1.)

Ideologies (1)

Throughout the Chosun era there was a continuing struggle between Buddhist belief and ritual, and Confucianism. The Chinese-style, Confucian civil service examinations were ἀrst held in Korea in 958. Confucians had long looked down on Buddhism as an intrusion distracting the masses from the hard work of building a society based on justice and propriety, where humanity and science would be the guide rather than superstition, the spirits, and the gods. Confucianists were especially offended by the seeming indolence of monks, as well as their celibacy and hence their disrespect of parents in refusing to beget children and thereby continue family lines.

In the United Silla period (668–918), Korean Buddhism had thrived, even while adjusting to Confucian norms, and the Silla capital of Kyongju was reported to have been dense with temples. The Goryeo kingdom (918–1392) likewise celebrated its adherence to Mahayana Buddhism while simultaneously basing its examination and administrative system on Confucian principles.12 The founders of the Chosun dynasty in 1392, however, attacked Buddhism and other folk religions as corruptions that served only to mislead the common people. The temples in towns and cities were demolished, and the founders ordered that no temples were to be built within the new capital of Hanyang (Seoul). Only temples in the mountains could remain standing (Clark 2000, 41). (The absence of temples in the present Seoul 30urban landscape, especially when seen against the forest of churches, is extraordinary.)

Neo-Confucianism had arisen in China in the Tang dynasty (618–904), reaching something of a zenith with Confucian scholars of the Song dynasty (960–1279). Zhou Dunyi (1017–1073) is seen as its ἀrst true pioneer. Neo-Confucianism developed both as a renaissance of traditional Confucian ideas and as reaction to the more metaphysical ideas of religious Buddhism and Daoism. Neo-Confucianism was a social and ethical philosophy that would bring a more syncretist and tolerant approach to Confucianism, more open to Buddhist and Daoist teachings—though not without resistance—and more academic and “scientiἀc.” While borrowing metaphysical ideas from Daoism, neo-Confucianism emphasized humanism and rationalism in the belief that the universe could be understood through human reason—the task was to create a harmonious relationship between the individual and the universe. Reason would supplant (Buddhist, Daoist) meditation.13

Neo-Confucianism was introduced to Korea by An Hyang (1243–1306) in the Goryeo dynasty, at a time when Buddhism was the dominant religion.14 It gained both influence and followers, mostly from an anti-aristocratic middle class that became the vanguard in overthrowing the old dynasty and setting up the Chosun. Neo-Confucianism became the state ideology of the new dynasty; Buddhism was seen as poisonous to neo-Confucian order and accordingly was restricted and persecuted. Although the early Chosun reformers might have been Buddhist in their private lives, they agreed that the organized Buddhist religion had to be suppressed, its monasteries and lands conἀscated, and their members returned to “useful” occupations. Remaining Buddhist clergy would be banished to mountain-dwelling monasteries and Korea would be a neo-Confucian state (Clark 2000, 9; also Duncan 1996).

The founding Chosun monarch Taejo had given priority to the establishment of institutions of Confucian learning.15 The fourth monarch, King Sejong the Great (r. 1418–1450), brought together Confucian humanism and progressive administration in what almost amounted to a welfare state. Arguably his greatest cultural achievement was the creation of the Korean alphabet, han-gul. Sejong’s reign is commonly seen as premodern Korea’s golden age: Koreans had invented movable metal type printing around 1234—two centuries before Gutenberg (in the 1450s)—perfecting the method in 1403. Then, in 1420, Sejong set technicians to the task of mechanizing the process: “We are prepared to print any book there is and all men will have the means to study” (Cumings 2005, 65, quoting Gale 1972, 233). 31There were similar advances in mathematics, the physical sciences, and technology that were comparable with China and certainly far ahead of the West and Japan.

Although Buddhism was restricted, Sejong returned to a private Buddhist devotion toward the end of his reign. There was always the Buddhist ἀghtback, however, and King Sejo (r. 1455–1468) signiἀcantly strengthened the Buddhist practices, in part to reinforce monarchical power by suppressing the yangban (“two branches”) class of office-holding aristocrats and the Confucian institutions. His successor, Songjong (r. 1469–1494), ninth king of the Chosun dynasty, worked to restore Confucian rule and reinforce the scholarly class.16 The anti-Sejo literati had used the institution of the royal lecture (haranguing the king) in an attempt to abolish Buddhist ritual and other anomalies from the life of the court.17 Land-tenure issues—hence those of social class—were always at the core of the struggles. Although tensions were always there, this was the peak of the resurgent neo-Confucian school.

Another basis of Confucian-Buddhist conflict related to the forms of society that each would imagine. Deeply embedded in Buddhism is the idea of human equality; enlightenment is open to all. Gong Fuzi (Master Gong, Confucius, 551–479 BCE), on the other hand, had taught that people are not created equal, nor do they become equal during their lives; some are stronger, some weaker; some will labor with their hands, others with their minds; what matters, rather, is the principle of mutual duties and obligations. A society’s most moral people should be its leaders, where moral knowledge is best acquired through the study of philosophy, history, and literature. Thus the soundest investment is in education; the pathway to honor and authority—to being truly respected and followed by others—is via success in the Confucian examination system. To the Confucian mind, the Buddhist focus on meditation and otherworldliness presented as indolence at one level, as unscientiἀc superstition at another, and the property and wealth of the temples would be put to better use if invested in the education of the people.

The Confucian system subsequently disintegrated—went underground—in the face of Western encounters and Japanese oppression, only to reemerge in the present age. John Duncan (2000) refers to “the plasticity of Confucianism” throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Korea’s two most prominent neo-Confucian scholars were Yi Hwang (1501–1570) and Yi I (1536–1584); they are today commemorated on Korea’s one-thousand- and ἀve-thousand-won banknotes, respectively. Major thoroughfares in modern Seoul are named for them. 32

Boyé Lafayette De Mente suggests that, for older Koreans in the present day, the most important word in the Korean language might be aboji (“father”)—indeed, Korea’s traditional culture might be described as a father culture because of the central role that fathers played in the social structure and in day-to-day living for over ἀve centuries (De Mente 2012, 1). The place of women, by contrast, was always circumscribed (Seth 2002; Kim Youngmin and Pettid 2011). As something of a corollary to the neo-Confucian system, man and wife were to be placed in different realms of duty and obligation. Whereas women in the Goryeo period could enjoy a small measure of freedom—widows, for example, could remarry—the Chosun wife would ἀnd herself spatially conἀned, bereft of property, nameless, and effectively a gift to her husband’s family and household; she had no rights of inheritance. Her best hope—usually realized—was to rule the inner sanctum of that household (Ko et al. 2003; Jung Ji-Young 2011). Ancestors were to be venerated, with ancestor “worship” being arguably Korea’s most important tradition, albeit inauspiciously instituted with a new law in 1390. Also to be venerated were teachers, “the greatest Men in the Kingdom” (Ledyard 1971, 123, 218–219).

During the Goryeo era the wealthy ruling class had been referred to as the yangban (“two branches”) class, indicating the two types of official, civil and military, although it was in Chosun that the system reached its full power.18 Entry to the yangban required either having passed the merit examination or having been appointed as a favor by the king or a high official as “merit subjects.” There was always tension between the examination passers and the merit subjects in their struggles for power and royal support. The enormous power of the yangban and their bitter and often violent divisions progressively undermined the Chosun kings and reflected their corresponding weakness. It was in the yangban class that women were most constricted: marriage was a union arranged between two surnames and could not be changed within a lifetime. Husbands could kill adulterous wives; concubinage, on the other hand, was to be tolerated (Haboush 2003).19

There were exceptions to this repression, however. While neo-Confucian ideologues attempted the eradication of Buddhism, the common people retained attachment to Buddhist practices and their comfort, but also to folk religions, shamanism, geomancy, and fortune-telling. Though condemned by both Confucians and the modern world, these thrived then and still persist today, constituting a “second tradition” in conflict with elite culture. In this second tradition, women typically found pathways for their artistic expression; they could escape the constricting virtues: the shamans, for instance, were typically female. 33

The sudden shift in the status of Korean women at the end of the twentieth century, to be observed in chapter 5 below, must be seen as extraordinary against such a historical background.20

In 1592 the Japanese warlord Toyotomi Hideyoshi invaded both Ming and Chosun realms in the Imjin War (Hawley 2005).21 Though ultimately defeated in a second invasion in 1597–1598 (principally by the Korean admiral Yi Sun-sin), the Hideyoshi invasions destroyed government records, cultural artifacts, archives, and historical documents. There was land devastation, population loss, and loss of artisans and technicians. As the land registers were destroyed, the basic class relationships were overturned; the class structure began to crumble.

Postwar uncertainty was complicated by the collapse of Ming China and the rise of the Manchu Qing and was spurred by the rise of revolutionary ideas. The yangban elite shunned Sejong’s han-gul alphabet as too easy, instead adhering to the idea that Chinese characters were beyond the ability of the lower classes and hence constituted a barrier to protect their own privileged positions. Slowly, however, use of the “too-easy” han-gul began to permeate to the otherwise bypassed royal and yangban women (and even down into the non-yangban strata), who began to produce a literature of diaries, memoirs, and stories. The theme of the novel Hong Kil-tong chon, by Ho Kyun (1569–1618), was that all people are born equal and that, if provoked, the lower classes together with the peasant class could become a powerful force in the struggle for social justice (Lee Ki-baik 1984, 244). There was also the Chunhyangga (Song of Chunhyang), one of the ἀve p’ansori (ancient song dramas) surviving today; it is about a woman of chaste reputation but also about resistance to the aristocracy (Eckert et al. 1990, 175, 190; Clark 2000, 72–74).22 It continues to be immensely popular and has been made into over a dozen ἀlms, as well as the more recently popular Korean drama series Delightful Girl Choon-Hyang of 2005, part of the Korean Wave output.23 Such ideas gave encouragement to the people and further undermined the prestige of yangban (gentry) society.

Even among the yangban, however, there were impulses to reform. A central theme of neo-Confucianism had been truth through a better understanding of reality—“the investigation of things” (Clark 2000, 15). A group of yangban accordingly set up their own school of thought called silhak (“practical learning”) in response to the increasingly metaphysical nature of neo-Confucianism, its arid scholasticism, and its disconnect from the rapid agricultural, industrial, and political changes in Korea from the late seventeenth to the early nineteenth centuries. Especially signiἀcant to the movement was the novelist and philosopher Bak (Park) Ji-won (1737–1805) (Park Ji-won 2011). 34Silhak scholar Yi Su-gwang (1563–1628) traveled to China and returned with the new Western learning then spreading in Beijing, also initiating a tradition of interest in Korean history (Eckert et al. 1990, 168). Western scientiἀc ideas—mathematics, astronomy, study of the natural world—had been introduced into China by Jesuit missionaries, and these in turn came to infect silhak. Jesuit philosophy and theological exegesis were also adopted, and some went so far as to establish their own branch of Catholicism in Seoul, as the beginning of Korean Christianity.

A consequence of the Hideyoshi invasions of the 1590s had been reinforcement of Korean ideas of the Japanese as barbarians, pirates, and cultural inferiors (Haboush 2016). Another had been a strengthening of Korean seclusion—a “contemptuous exclusiveness,” the nineteenth-century American intruders called it (Drake 1984, 105). Yet neighborly relations with the Japanese continued as Korean officials would be dispatched periodically to Edo; Busan in particular long facilitated the minimal official trade between Korea and Japan and, in the nineteenth century, developed into an almost extraterritorial base for Japanese commercial, agricultural, and then military ambitions (Kyung Moon Hwang 2010, 145).

While the Korean king acknowledged Chinese suzerainty and tributary obligations to the Chinese emperor, practically this amounted to very little: China’s policy was effectively one of “benign neglect,” leaving Korea with substantive autonomy as a nation. Japan, however, was perceived by the Koreans as yet another state in the Sinic thrall. By the nineteenth century, Korean policy was mostly one of “no treaties, no trade, no Catholics, no West, and no Japan” (Cumings 2005, 91, 100). There were bloody pogroms against native Catholics in 1801, 1839, and 1846 (Eckert et al. 1990, 183–184). By gunboat diplomacy, Japan established unequal treaties with China in 1871 and with Korea in 1876, albeit written within the norms of diplomatic language of the time. The barriers had been breached by the erstwhile cultural inferiors.

Ideology and the end of the Chosun age

In the nineteenth century, amid conditions of peasant revolt and virtual civil war, Ch’oe Che-u (1824–1864) formulated the ideology of Donghak, or “Eastern Learning,” to stand against “Western Learning” (Catholicism), though the doctrine also incorporated elements of Catholicism (Lee Ki-baik 1984, 258). Donghak was to rescue the farmers from prevalent poverty and unrest and to secure political and social stability. In a trance Ch’oe Che-u had experienced a revelation 35compelling him to spread a message of spiritual enlightenment throughout Korea.24 He envisioned a new world order based on human equality, a theme later formalized in the doctrine of innaecheon (“humans are Heaven”); in the new religion of Cheondogyo (Religion of the Heavenly Way), the orthodox form of Donghak, this became the central tenet of the religion’s theology, persisting into the present. Cheondogyo arose in 1860 as a mixture of elements of Confucianism, Buddhism, indigenous Songyo (teachings of the ancient Silla kingdom’s hwarang, or “flower of youth” class),25 native Korean beliefs in spirits and mountain deities, and modern ideas of class struggle that one might now consider Marxist, together with nationalistic and antiforeigner (anti-Western, anti-Japanese) sentiment; it also proclaimed a strong millenarian message, to the alarm of establishment circles (Eckert et al. 1990, 187). It underlay the abortive Donghak Revolution of 1894, which was seized, many decades later, as an ideological forebear by both North and South Korea (Bell 2004; Beirne 1999; Hong Suhn-kyoung 1968).

Ch’oe Che-u’s ideas rapidly gained acceptance, and he set his doctrines to music so that farmers could understand them more readily. There were satirical mask dances and village magic performances. His teachings were systematized and compiled as a message of salvation, incorporating the syncretized elements from Confucianism, Buddhism, and Songyo referred to above, together with modern humanist ideas. Exclusionism from foreign influences was another characteristic of his religion, which incorporated an early form of Korean nationalism and rejection of alien thought. The early Donghak slogan is revealing: “Drive out the Japanese dwarfs and the Western barbarians, and praise righteousness” (Hatada 1969, 100).26

Although the Chosun government executed Ch’oe Che-u in 1864 on charges of treason, his movement thrived and poverty-stricken farmers gathered under his standard. There were large-scale Donghak demonstrations in 1892; in 1893 Donghak believers went to Hanyang (Seoul) and demonstrated in front of the royal palace. The uprisings increased to effectively become a revolution. The Donghak Revolution occurred when Korea was on the verge of radical transformations that were in part precipitated by that revolution. Society was stagnating under a rigid Confucian social hierarchy whereby peasants were overtaxed and generally oppressed by corrupt government officials and the yangban class—the Donghak Revolution would have ended the taxation of the peasantry and crushed the yangban. External forces, including Western encroachment, the impending collapse of Qing China, and the aggressive rise of Japan, were causing considerable alarm in Korea (Bell 2004). In 1875 there was a Japanese provocation—the 36so-called Unyo Incident—followed by gunboat diplomacy in 1876 to force a treaty and the entry of a Japanese legation in 1880 (Eckert et al. 1990, 200–201).

Among many of the intelligentsia there was an emerging pro-Japan push, albeit enmeshed with elements of Korean nationalism.27 Following a military mutiny in 1882, a small and rather clandestine group formed, variously referred to as the Progressive or Independence Party, wanting to emulate Japan’s Meiji Restoration and hoping for Japanese support. Finding reform blocked by conservatives centered on the family of Queen Min, on 4 December 1884 they initiated a violent coup in Hanyang (Seoul). A false report of an uprising of Chinese troops based in the Chinese legation was conveyed to King Kojong, who was evacuated to Gyeongun Palace (today’s Deoksugung Palace) and then urged to seek protection from the garrison of the nearby Japanese legation. The Chinese troops moved into action, the coup was defeated, and key Progressives fled with the retreating Japanese guards to asylum in Japan. Among those fleeing was Seo Jae-pil (Philip Jaisohn, 1864–1951), who then traveled to America, where he studied medicine and became the ἀrst Korean to receive US citizenship (Lee Ki-baik [1961] 1984, 275–279).

Following their intervention, the Chinese tightened their hold on Korea’s government, though it was increasingly countered by mounting Russian presence and influence.28 From their refuge in Japan, Progressives continued in vain to call for reform (Kim Okkyun 2000, 256–258), while Korea descended into increasing chaos.

In 1894 Chon Pong-jun (1854–1895) assumed Donghak leadership, heading a popular revolt against the district authorities of Gobu County in Jeolla-do Province (around the present city of Gwangju); when peaceful demonstration proved ineffective, the farmers turned to violence and full-scale rebellion, which spread throughout the province. Again the immediate cause was the corruption of local officials, crushing taxation, and opposition to the yangban aristocracy, but also strong anti-Japanese sentiment. Alarmed at the support engendered by the uprisings, the royal court asked for Chinese intervention (Oliver 1993; Weems 1964). This, however, was a fatal move: Japan responded by invading in force, ἀrst driving out their Chinese rivals and occupying Hanyang, then turning to the Donghak, who were ultimately crushed. Chon Pong-jun was captured and beheaded, and Donghak troops and farmers were massacred by the Japanese. The Japanese demanded that the Korean government order Chinese troops to leave, as the Japanese officials announced their intention to maintain their presence in Korea to help sort out the country’s domestic mess. The Japanese military based itself south of the city at Yongsan, 37between Namsan and the river. On 23 July 1894 the Japanese occupied the royal palace and imposed “protection” on King Kojong. Two days later, the Sino-Japanese War of 1894–1895 erupted, with total victory going to the Japanese. On 8 October 1895, Queen Min was assassinated in Gyeongbokgung Palace, allegedly by Japanese “ruffians” at the behest of the Japanese minister. With the aid of Russian sailors, Kojong escaped to the Russian legation in February 1896, from where he succeeded in recovering some of his power, returning to Gyeongun Palace in February 1897. Caught in the middle between rising popular nationalism at home, China’s decay, and Japan’s expansionist modernization on its periphery, Chosun Korea clambered for survival, some assurance of independence, and the semblance of international equality, on 12 October 1897 declaring itself to be the Great Han (Daehan) Empire and its erstwhile king to be the Emperor Gwangmu—just like China and, more to the point, Japan.

Gwangmu (Kojong) ruled from Gyeongun (Deoksugung) Palace rather than the vastly grander and only recently reconstructed Gyeongbokgung.29 The extent of the latter made it difficult to defend in the increasing turmoil, as demonstrated in the assassination there of Queen Min; the Deoksugung, on the other hand, had a small periphery and was thereby more secure. Additionally, the Deoksugung had proximity to the Russian legation and thereby to its defending garrison—it was also no coincidence that Japanese advisors were now being replaced by Russians. The Deoksugung was also interesting for its architecture, for this was a hybrid assemblage like no other. Initially, like other royal palaces, it had comprised halls and other elements in traditional architectural forms, many dating from the 1592 war against the Japanese, and correctly oriented to the south. Subsequently the complex was reoriented to the east, against all tradition, with a new main Junghwajeon throne hall (from 1902) and the eastern gate becoming the Daehanmun imperial gate. In 1906 many of its elements were then reconstructed. The reorientation has the effect, intended or otherwise, of signaling a break from the Korean/Chinese orthodoxy. Equally radical was the insertion of a second, Western-style palace as the new imperial residence, including the imposing Neoclassical Seokjojeon, designed for Kojong by British architect John Harding in 1900 but not completed until 1910. Though Kojong was deposed in 1907, he continued to reside here until his death in 1919, and both he and the palace thereby became emblematic of the Daehan Empire’s claim for global (Western) connection but also of its lost independence.30

The spirit of independence was also expressed in 1896 with the founding of the Independence Club, principally by Seo Jae-pil, now 38returned from America; it mostly comprised veterans from the 1884 abortive coup (like Seo) and middle-ranking government officers. It was established to implement two symbolic projects, ἀrst the erection of Independence Gate to replace Yeongeunmun Gate (Welcoming Gate for Obligation, sometimes translated as Welcome to Beneἀcent Envoy of Suzerains), which was a symbol of unequal diplomatic relations between Korea and Qing China and of Korea’s tributary status. The Yeongeunmun had been built around 1407 in the Ming era, just outside Donuimun (Loyalty Gate), the great west gate to the city, for the ceremonial reception of the Chinese emperor’s ambassador; it was demolished in 1896 following the Japan-China Treaty of Shimonseki to symbolize the end of tribute. The second project was to transform the adjoining Mohwa-gwan (Hall of Cherishing China) into an Independence Hall and Independence Park (Eckert et al. 1990, 232–233).

A month after the declaration of the great empire, on 20 November 1897, the new nationalism was duly celebrated with the ceremonial inauguration of Dongnimmun (Independence Gate). Again architecture took on a symbolizing function. Whereas the Yeongeunmun had been in a Ming Chinese form, its replacement, Independence Gate, is in a modernist hybrid styling—its designer was Korean-American Seo Jae-pil, an independence activist, medical doctor, and founder of Korea’s ἀrst newspaper in han-gul.31 Despite Seo’s American experience, the styling presents paradoxically (to this observer) as akin to Japanese modernism of the time, though its avowed model was Paris’ Arc de Triomphe. Symbolically, the two supporting pillars of the old gate were left intact in front of the new one—its erasure and that of Chinese suzerainty would continue to be represented.

In 1905 Korea came to enjoy Japanese protection (more like Japan); then on 29 August 1910, it received the ultimate privilege of annexation, to become de jure part of Japan. Korea ceased to exist as a politically independent state.

Part 2

COLONIZATION

The post-1868 Meiji (Enlightened Rule) government in Japan found itself confronting three interlinked dilemmas. First, how was Japan to enrich and strengthen itself? From the 1880s onward an argument developed for “dissociation from Asia” (datsu-a ron) whereby Japan 39would distance itself from Asian countries to join the ranks of the Western imperialists. In this matter, Naoki Sakai (2000, 792) invokes the concept of negativity, “without which the reflectivity necessary for self-consciousness cannot be achieved.”32 Negativity might be implied in the notion of otherness, alterity, difference; it is certainly implied in defeat. Naoki Sakai cites the wartime historiography of Masao Maruyama, which asserted that the moment of negativity could be detected in Japanese thought in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, whereas the Chinese never succeeded in giving rise to their own negativity. Implicit here, in the justifying argument of Japanese political superiority over China, was the old thesis of “flight from Asia, entry into Europe”—Japan should be capable of modernizing itself while (the rest of) Asia must wait for the West’s initiative (Maruyama 1974). Yoshimi Takeuchi ([1947] 1993), an ardent sinologist, argued the opposite; the point to be made here is that the material interests of Meiji Japan sought ideological justiἀcation in a historiography that was always already contested. To achieve this self-modernization and thereby join “the West,” the Japanese would need to acquire colonies in Asia, expanding from their islands to the Asian mainland. The foothold for this was seen to be the Korean Peninsula.

Second, the turn from feudalism to capitalism brought the need to secure commodity markets, then to secure export markets for Japan’s products; for these, colonies would be essential, especially with the Western powers entering an era of strident imperialism in the 1880s.

Third, Japan faced a need for food security following a population boom, with a related need for resettlement space. Many Japanese migrated to Hokkaido and other parts of the Japanese archipelago, as well as to the Americas and Australia. However, Korea and especially Manchuria were increasingly seen as the logical areas for colonization (Park Chan Seung 2010, 83–86).33

There are other arguments presented to throw light on the colonization of Korea. If Manchuria was viewed as the more logical sphere for Japanese expansion, then the colonization of Korea is seen in some part as a strategic attempt to keep other potential colonizers out (Russia, Britain?). Also running through Japanese legitimizing ideology was a thread of enlightenment, seeking to end Chosun corruption and decay and bring about a better-educated, more hygienic, and more industrious Korean population.34 Additionally, colonization was rationalized as Japan “returning” to an ancient origin. There were also some less noble arguments: after the Meiji Restoration and the end of the samurai age, invasions would provide an outlet for the energies of disestablished samurai; colonization, in turn, would provide opportunities to spread Japan’s “imperial glory” (Eckert et al. 1990, 198). 40

The Japanese annexation of Korea was a gradual process. In April 1904, during the Russo-Japanese War, the Japanese Imperial Army under General Kuroki Tamemoto effected a landing near Incheon, then moved on to occupy Seoul. The war concluded on 5 September 1905, ending Russian influence in Korea and Manchuria; on 17 November 1905 the Eulsa Treaty with Japan was arbitrarily imposed on Korea, with American support, establishing a Japanese protectorate.35 British acknowledgment soon followed.36 When Kojong mounted a diplomatic effort to reestablish sovereignty in 1907, he was forced to abdicate in favor of his son. A two-tier system of administration developed in Korea: on one hand was the royal government of the Daehan Empire; on the other was the Japanese Residency-General, or what Lee Ki-baik (1984, 308) terms “government by advisers.” While responsibility might still lie with the royal departments, the Residency-General was always influential. After the 1907 deposition of Kojong, all authority passed to the Residency-General.

General Terauchi Masatake, as the third resident-general to Korea, executed the Japan-Korea Annexation Treaty in August 1910, thereby becoming the ἀrst Japanese governor-general. The ἀrst decade of the formal colonial period was the “military rule” era (Kyung Moon Hwang 2010, 162). In the cities, and especially in Seoul, there was effectively a police state as the Japanese struggled to stabilize their colony, although the consequence was to transform gathering discontent into an ensuing explosion, on 1 March 1919—the March First Movement.

Pro-Japan sentiment had persisted after the failed 1884 coup, manifesting in aspects of what Lee Ki-baik calls the “forces of enlightenment” (elsewhere the Patriotic Enlightenment Movement),37 and especially ambivalently in the 1904–1910 Ilchinhoe (Advance in Unity Society), which ardently embraced Japan’s discourse of “civilizing Korea” and saw colonization as an opportunity to advance its own populist agenda. Both the Japanese colonizers and the Korean elites disliked the Ilchinhoe for its aggressive activism, which sought to control local tax administration and reverse the existing power relations between the people and government officials. Ultimately, the Ilchinhoe members faced visceral moral condemnation from their fellow Koreans when their language and actions resulted in nothing but the emergence of the Japanese colonial empire in Korea (Moon Yumi 2013). There were also strong anti-Japan movements: as Brandon Palmer (2013) observes, Koreans’ long-standing animosity toward Japan culminated in active Korean resistance to colonial rule, of which the two main instances were the “righteous armies” and the March First Movement. From 1907 to 1912, small bands of righteous armies fought against colonial rule, with some 17,600 Korean ἀghters and 41civilians allegedly killed in the process of their suppression. The March First Independence Movement of 1919 was a peaceful peninsula-wide protest with nearly a million participants and a signal event in recent Korean history.

Ideologies (2)

The 1 March 1919 event needs to be seen in the context of continuing ideological evolution in Korea. Japan’s annexation of Korea came as an overlay across an intricate web of ideologies and beliefs. While neo-Confucianism had collapsed in the onslaught of (Japanese) modernization, its ideals of self-discipline, order, respect, appropriate behavior, and national dignity simmered beneath any surface of subservience. The Confucian insistence on the material, on science and “the real,” continued in tension with the Buddhist preoccupation with the immateriality of the phenomenal universe. Jesuit-infused Christian modernism and openness to Western science, philosophy, and theological exegesis had interlaced with both Confucian and Buddhist orthodoxies to yield, in turn, the still-persisting (in the twenty-ἀrst century) Donghak ideology.

Despite its virtual annihilation in 1894 at the hands of the Japanese, Donghak could stand as a powerful symbol of Korean resistance; furthermore, it was distinguished as an indigenous, democratic, nationalistic, and modern political philosophy. The argument has been that, whereas China eventually had to turn to an imported, Western ideology for its modernization (Communism), Korea could claim to have found a guiding ideology in its own traditions and powers of invention (Kang Wi Jo 1968, 48). Cheondogyo, the religious formulation of Donghak, had failed to be similarly crushed by the Japanese, becoming instead the vehicle for the historical enhancement of the Donghak myth of resistance. Kirsten Bell (2004) cites Kim Yong Choon (1978, vii): “What is Korean thought? Answering this question might involve several traditions such as Buddhism, Confucianism, Shamanism, Christianity and Ch’ongdogyo [Cheondogyo]. However, Ch’ongdogyo alone is the major indigenous tradition developed in Korea, while Buddhism, Confucianism, and Christianity are of foreign origin, and Shamanism is relatively common in many parts of the world.”

Cheondogyo certainly had its nationalistic element and provided motivating ideology for the 1 March 1919 Korean Declaration of Independence and the consequent March First Movement against the Japanese. Of the thirty-three signatories to the declaration, fifteen were Cheondogyo; however, it should be noted, sixteen were Protestant (Kyung Moon Hwang 2010, 171). Nevertheless, other elements 42of Cheondogyo developed into the Ilchinhoe referred to above, which openly supported the annexation of Korea and from which it subsequently beneἀtted.

Nor was there any political consensus among the Christians. While there was nationalist sentiment, most entered a form of social contract with the authorities to refrain from political activities in order to avoid persecution. A degree of cooperation with the state persisted until the outbreak of war in 1937 when the issue of Shinto worship came to the fore, and then the 1942 expulsion of American missionaries.38 Even here, however, there was no social consensus: among Catholics, for whom shrine worship was common, the respect for Shinto shrines was less problematic.

This fragmentation of ideologies, both Cheondogyo and Christian, characterized positions toward the Japanese colonial authorities, as well as toward pathways to modernity. It characterized the March First Movement and then persisted into the diversity of positions that underlay the post-1945 maelstrom. The role of Christianity here cannot be exaggerated: the mission stations—churches, schools, hospitals, and missionary residences—expressed a Western civilization that created a sense of awe and mystery among Koreans, who were experiencing modern amenities for the ἀrst time. Missionary compounds provided a window on the Western world that was not distorted by any refraction through Japanese colonization or ideology. The demand for education was overwhelming; consequently some 800 schools accommodating approximately 41,000 students were founded by the missionaries, with many independence ἀghters among the alumni. The Christian population reached 315,000 in the mid-1930s, and around 500,000 by 1945; although their numbers were much smaller at the time of the 1919 uprising, the glimpse presented of a Western modernity was a powerful motivation.39

ἀ e March First Movement

The end of World War I and the breakup of empires had encouraged expectations of Korean independence. Erstwhile Emperor Kojong died in January 1919, with rumors of poisoning, and independence rallies against Japanese invaders occurred nationwide on 1 March, to be suppressed by force as a result of which some seven thousand people were killed by Japanese soldiers and police. In the aftermath of the 1919 suppression, on 13 April 1919 the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea was formed in Shanghai, with Syngman Rhee (1875–1965) as president. This did not achieve recognition by world powers, although a form of recognition was given by the nationalist 43government of China. The Provisional Government coordinated armed resistance against the Japanese Imperial Army during the 1920s and 1930s, including the signiἀcant Battle of Qingshanli in October 1920, in eastern Manchuria. The Korea Independent Army lured a larger Japanese force into battle, inflicting them with a major defeat and forcing a Japanese withdrawal from the area. The Battle of Qingshanli is considered a great victory for Korean guerrilla tactics.

In the aftermath of the 1919 uprising and events in Manchuria, the Japanese came to realize that they were on “the wrong side of history”—their form of repressive colonization had found itself in the wrong century. Always concerned with appearing “modern,” this realization was the beginning of their “cultural” policy, and there was a relaxing of Japanese control. In the 1920s the colonial government was headed by a more humane governor-general, Admiral Viscount Saito Makoto (1858–1936), who permitted Koreans to assemble, speak, and publish their own newspapers and magazines; he improved education and allowed Koreans to join religious and even political organizations (Clark 2000, 17). In 1907 the Japanese had passed the Newspaper Law, effectively preventing the publication of local papers. Only the Korean-language Taehan Maeil Sinbo continued publication because it was run by a foreigner, E. T. Bethell. Hence for the ἀrst decade of colonial rule there were no Korean-owned newspapers, although books and several dozen Korean-owned magazines were published (Robinson 1988). In 1920 these laws were relaxed, and two of the three major Korean daily newspapers, Dong-A Ilbo and Chosun Ilbo, were established in 1920. In 1932 a double standard applying to Korean vis-à-vis Japanese publication was removed. However, the Japanese government still seized newspapers without warning, with over a thousand such seizures recorded between 1920 and 1939. By 1940, with the Paciἀc War increasing, Japan again shut down all Korean-language newspapers. In the 1920s, however, the cultural nationalist movement was wide-ranging; certainly there was censorship, but there was also a vibrant liberal and even Marxist literary and artistic movement, well into the late 1930s (Robinson 1988).40

Many Koreans still advocated armed insurrection as the only path to independence; others, however, saw their task as the advancement of the culture and the reinforcing of identity to yield, ultimately, a future generation as the basis on which to build a new Korea. There were two moderate-nationalist movements that focused on a more gradual approach to national resurgence. The ἀrst was the National University Movement established in 1922 and led by the Society for the Establishment of a National University, as an outcome of intelligentsia concerns—there had been a long and proud tradition of elite 44education in Korea, though it was now deeply threatened.41 Colonial schools had a strong emphasis on Japanese language acquisition, cultural values, and Japanized Korean history; there were few opportunities for college education in Korea, so most college students ended up in Japan. A national fund-raising campaign was launched. Within six months, however, inἀghting among cliques, typical of the era, undid the project. The Japanese authorities announced the establishment of an imperial university for Seoul, the Keijo Imperial University (1924–1946), with new buildings scheduled for 1926 (Eckert et al. 1990, 290–291).

One factor in the collapse of the national university project was the withdrawal of support by the more radical student groups, including the All Korean Youth League. Student radicalism was strong, and paradoxically reinforced from Japan: Korean students traveling to Japan may have become somewhat assimilated into Japanese ways and thought, yet that was often into Japanese radical, left-wing thought, as Japan was also in some social turmoil at that time. Socialist thinking at the student level was in a mismatch with the second moderate-nationalist movement, the movement for incremental independence: worsening economic conditions, Government-General economic reforms, and general concern regarding economic dependency led to the Korean Production Movement of 1923–1924. Korean businessmen had been lobbying for subsidies and concessions so that they could compete on equal footing with Japanese enterprises; however, now the strategy shifted to mobilize national sentiment to support Korean industry and products. The effect of such a shift in consumer behavior would be the accumulation of Korean capital to compete with Japanese capital (Eckert et al. 1990, 291–293).

Repression

In April 1926 Sunjong, the last Chosun monarch, died. Apparently genuine sorrow combined with hostility toward Japan to produce an outpouring of both grief and anger. Mindful of how the death of Kojong had led to the March First Movement, the colonial police moved to suppress the threatened mass demonstrations, which, however, proceeded in a variety of forms. Student radicalization increased, spreading through the country and culminating in the Gwangju Incident of 1929, in which ἀghting erupted between Korean and Japanese students, the police blamed the Koreans, and there were mass arrests, followed by further escalations. By early 1930 demonstrations had spread across the country (Lee Ki-baik 1984, 364). The Gwangju Incident led to tightening military rule in 1931. Then with the outbreak of 45the Sino-Japanese War in 1937 and World War II, Japan attempted the total Japanization of Korea, although the effort was always more frustrated than effective. The Japanese governor-general from 1936 to 1942, General Jiro Minami (1874–1955), ordered cultural assimilation of Korea’s twenty-three to twenty-ἀve million people: Korean culture became illegal; worship at Japanese Shinto shrines was made compulsory; and use of the Korean language was progressively banned, as was the study of Korean literature and culture, to be replaced with that of Japan; while the school curriculum was changed to outlaw teaching in the Korean language and to abolish the teaching of history. Koreans were pressured to adopt Japanese names. Korean cultural artifacts were destroyed or taken to Japan. From 1939 onward, education would be aggressively redirected to the task of converting Koreans into useful, Japanese-speaking imperial citizens.

Assimilation efforts became extreme, with total mobilization in 1943; Koreans would be educated as “new Japanese” (Palmer 2007). Lee Ki-baik has described the last, frenetic attempt at assimilation:

The leading ἀgures in the Korean Language Society were arrested in October 1942, on charge of fomenting a nationalist movement, and as a result of the severe torture to which they were subjected by the Japanese police, Yi Yun-jae and some others among the Korean linguists died in prison. Novelists, poets and other creative writers were forced to produce their works in Japanese, and in the end it was even required that Japanese be exclusively used in the schools and in Korean homes. Not only the study of the Korean language but also of Korean history was considered dangerous. (1984, 353)

Many Koreans were transported to Japan to work in mines and factories as Japanese workers were drafted into the military; women were also put to work, mostly in factories, although increasing numbers were sent with Japan’s military as cooks, laundresses, and coerced prostitutes—the “comfort women.”42

Using Japanese and Korean sources, Brandon Palmer (2013, 3) estimates that from 1937 to 1945 Japanese colonial authorities recruited at least 360,000 Koreans to serve in the military as soldiers or civilian employees, and a further million as industrial laborers within Korea. By the end of World War II, between four and seven million Koreans had been mobilized throughout Japan’s wartime empire.43 Resistance to mobilization manifested within Korea, even more so outside the country. The Shanghai-based Provisional Government formed the Korean Liberation Army in 1940, bringing together many of the Korean resistance groups in exile. On 9 December 1941 the 46government declared war on Japan and Germany, and the Liberation Army participated in Allied action in China and Southeast Asia. An assault on imperial Japanese forces within Korea was planned; however, with the 1945 Japanese surrender, this goal was never achieved. At war’s end, there were vast armies of Koreans who had fought on both sides.

ἀ e mobilization era and the question of assimilation

Where assimilation had always underlain colonialist ideology, with various threads running through Government-General policy, mobilization brought it to new levels of enforcement and extremism that seemed to go back to an earlier colonizing experience. Mark Caprio argues that Japan’s earlier history of colonial rule, notably of Ainu and Ryukyuan peoples, had tended more toward obliterating those cultures than incorporating those peoples as equal Japanese citizens. With their annexation of Taiwan in 1895, the Japanese moved more toward European models, such as England and France, in developing policies for assimilation.44 England’s assimilation of the Scots and the Welsh is cited. Caprio suggests that there was indeed a potential for Korean assimilation but that very few initiatives were taken to implement the policies. Instead, the Japanese maintained separate communities in Korea with two separate and unequal schooling systems, and very little intermarriage or effort to hide their disdain for Koreans as inferior (Caprio 2009).45

Takashi Fujitani (2011) makes the provocative comparison of Korean soldiers recruited or drafted into the Japanese Imperial Army with Japanese Americans similarly recruited into the US military. In the last years of the Paciἀc War, as Naoki Sakai (2000, 805) observes, referencing Edwin O. Reischauer, Japan and the United States engaged in the ideological war for the hearts and minds of multiethnic Asia.46 Both, accordingly, were compelled to adopt explicitly antiracist strategies in contradiction to popular perceptions of their histories. The dilemma for Japan was that it needed to project antiracism at precisely the moment when it had to forcibly recruit the Koreans into the effort of total warfare.

In their attempt to disavow racism even as they reproduced it, Japan and America moved closer together (Fujitani 2011). Sakai adds that after 1945, as the United States assumed responsibility for Japan’s colonies, Japan was relieved of the burden of decolonization. Korea, on the other hand, was left with the abiding bitterness of experiences of resistance versus collaboration, with its attendant uncertainties of identity. 47

Part 3

ERASURE OR RADICAL BREAK?

While the concern here is with the effects of the Japanese colonization both at the time of and subsequent to the 1945 liberation, there is always the question: to what extent are we observing the effects of colonization, and to what extent those of modernization? Certainly late Chosun was caught up in that maelstrom of modernity that marked the turn to the twentieth century. Furthermore, in some ways the 1910 declaration of formal colonization was tokenistic, as Japanization had been a gradual process of the preceding decades. The following discussion of modernity-colonization’s effects, observing the blurred boundary between Chosun and colony, will be thematic rather than chronological; its purpose is to explore how these effects are to be read off the space and fabric of modern Seoul.

Migration and land

In the late nineteenth century Japanese merchants had settled in Korean towns and cities seeking economic opportunity so that by 1910 Korea was reputed already to have Japan’s largest overseas community. Japanese settlers were interested in acquiring agricultural land even before Japanese landownership was legalized in 1906. Terauchi Masatake, as governor-general, advanced settlement through land reform, which was initially popular with the wider Korean population.47 Hwang Insang observes that colonial economic exploitation and control was symbolized in the Land Survey and the Company Law, with the former serving as the foundation of Japan’s colonial rule and the structural basis for economic exploitation of the colonial economy.48 A new Land Survey Bureau conducted cadastral surveys that established ownership on the basis of documentary evidence (deeds, titles, etc.); ownership was denied to those unable to provide such written proof, and these turned out to be mostly aristocratic and absentee landlords who could only quote traditional rights. Considerable private lands thereby fell into the hands of the Government-General. Additionally, under the Forest Law of August 1911, all government mountain forests came under the Government-General; a Forest Survey Ordinance in 1918 further extended forest areas to Government-General ownership.

As land was increasingly acquired by Japanese individuals and corporations, many Korean erstwhile landowners, together with 48agricultural workers, became tenant farmers; as often happens in Japan itself, they were forced to pay over half their crop as rent. Then, additionally, they had to pay tax. Landowners were mostly Japanese or Japanese collaborators, while tenants were all Korean. Cumings (1981) reports that in 1942 there were 2,173 Korean and 1,317 Japanese owning more than ἀfty chongbo (approximately 123 acres); the largest of those, holding 500 acres or more, comprised 116 Koreans and 184 Japanese. It is not possible to determine how many of those Korean landowners were enjoying the beneἀts of collaboration with the government.

By the 1930s the growth of the urban economy and the migration of farmers to the cities had weakened the power of the landlords. With the onset of the wartime economy, realizing that landlordism impeded increased agricultural productivity, the government brought the rural sector under the wartime command economy through a Central Agricultural Association in which membership was obligatory.

At the cataclysmic end of colonization in 1945, some 750,000 Japanese resided in Korea, contrasting with the 20,000 to 30,000 French nationals in Vietnam. Whereas most French in Vietnam were engaged in colonial administration, only 40 percent of the Japanese in Korea were in colonial administration, while the rest were civilians. Japan’s aggressive migration policy, however, had Japanese mostly settling in the Korean cities and seizing power in the Korean economy. They lived in their own quarters separate from Koreans and enjoyed a privileged status in education and health services.49

Economy

Cyhn Jin (2002) is among scholars who have argued that Japanese rule worsened economic conditions in Korea; Atul Kohli (2004), on the other hand, concludes that the economic development model instituted by the Japanese was crucial in Korean economic development and was maintained by the Koreans post-1945. The latter is a view also supported by Jones (1984) and by Savada and Shaw (1990), who argue that Japan’s economic development brought little beneἀt to Koreans although its aftermath was more positive, a point to be taken up following.

While the core interest remained colonial, namely to exploit Korea’s resources, in the 1920s new efficiencies and structural reforms were brought to this enterprise. Furthermore, restrictions on native enterprise were eased, thereby stimulating the emergence of many Korean family-based companies that would later evolve into the giant conglomerates that eventually came to dominate the Korean 49economy, such as Samsung and LG, a story to be reprised in chapter 3. Kyung Moon Hwang (2010, 165) especially draws attention to the family-owned Kyongsong Textile Company, which eventually branched out into other industries and regions, with factories in Manchuria and elsewhere. Especially influential has been Carter Eckert’s account of the same company (chapter 1). Eckert’s book had concentrated on a single, remarkably successful Korean family, the Kims of Koch’ang County. The brothers Kim Songsu and Kim Yonsu had proἀted from a Japanese opening of the rice market between 1876 and 1919, allowing them to accumulate capital, with which the family established the Kyongsong Spinning and Weaving Company, or Kyongbang, in 1919 for the production of yarn and cloth. From 1919 to 1945 Kyongsong grew substantially, a success that Eckert attributes in part to Japanese colonial control, as well as to government subsidies and loans and to Japanese-enabled access to raw materials (cotton from China), machinery and expertise (from Japan), and markets (initially China, later the Japanese military for uniforms). He further notes that Kyongsong provided support to the Japanese ideology of Naisen Ittai (“Japan and Korea as one”), reflecting only a weak commitment to Korean nationalism generally on the part of the Korean bourgeoisie. The group continued to prosper after 1945 and into the present.

In this era Korea acquired an industrial capitalist class whose interests were in harmony with Japanese imperial goals and that accordingly enjoyed colonialist support. Correspondingly there also arose an industrial proletariat, albeit minute alongside the larger, agricultural population; however, this was a very low-wage proletariat, without legal or political protection. By the 1920s there was also a developing proletarian sensibility within the (Marxist) intelligentsia movement of New Tendency literature (Kimberley Chung 2014).

Industrialization and the burgeoning of Korean enterprises brought a reordering of the social structure, not least through a dramatic rise in social mobility. Especially dramatic were changes in the status of women: increasing numbers moved into education and far more into factory employment. With the advent of the “new woman” or “modern girl,” new opportunities arose for new enterprises to produce the commodities and publications that a proto-bourgeoisie could be encouraged to demand. The publications, in turn, provided the media for women’s voices to now be heard. Increasing numbers of Koreans traveled to Japan for education, returning to Korea awakened by the liberty and “style” of a culturally advanced middle class that would then be emulated, albeit in the cities rather than the countryside, and then mostly in Seoul. 50

Henry H. Em begins ἀ e Great Enterprise: Sovereignty and Historiography in Modern Korea with a reference to an essay of September 1932 in Tongkwang by Kim Ki-rim, announcing 1930s modernity as the era of short hair and calling on “Miss Korea” to cut her hair—the essay had argued that modernity would not be identiἀed by “sport, speed, sex,” but by short hair, and “women of status venturing outside in daytime unconstrained by marriage and motherhood. Indeed by the 1930s one could have seen in colonial Korea baseball games, beauty pageants, exhibitions, display windows fronting the new department stores, street cars, street lights, and cafés that enabled crowd watching” (Em, 2013, 1). Being modern was not easy. Some Korean women conformed to the dictates of colonial modernity; others, however, took deliberate pains to distinguish between what was “modern” (Western) and thereby legitimate and what was “Japanese,” hence illegitimate. Yoo (2008) suggests that what made the experience of these women unique was the dual confrontation with modernity and with Japan as a colonial power.

Diverse aspects of economic change related to new infrastructure. There was massive investment by the colonial government in communications and transportation infrastructure, schools and technical training centers, hospitals and other health initiatives—all, certainly, catering to the Japanese migrant population to assist the colonization process yet also improving the welfare of many Koreans. This might be seen as merely a continuation of innovatory programs under the old Daehan Empire whereby Seoul had acquired railways, trams, electricity, hospitals, industrialized mining, and other hallmarks of a modern city, except that these had been implemented when Korea was already coming under the Japanese sway.50 Furthermore, it was the acceleration and scaling up of these that distinguished the colonial era.

The experience of rapid industrialization and modern infrastructure under the Japanese, in both Korea and Manchuria, is seen to have had long-lasting effects. Cha Myung Soo (2010) has argued that “the South Korean developmental state, as symbolized by Park Chung-hee, a former officer of the Japanese Imperial Army serving in wartime Manchuria, was closely modeled upon the colonial system of government. In short, South Korea grew on the shoulders of the colonial achievement, rather than emerging out of the ashes left by the Korean War, as is sometimes asserted.” We return to this theme in chapter 3.

Education

The long lineage of the Korean educational tradition has already been referred to—Lee Ki-baik (1984, 119, 130) can allude to the struggles in 51the Goryeo (Koryo) age between the National University (founded in 992, in Gaeseong) and the more prestigious twelve private academies. The tradition had then been enriched over the centuries through Buddhist and Confucian insertions.51 The colonial imposition thus came on top of something very ancient, albeit privilege-focused, but also quintessentially Korean. The Japanese in Korea produced a public education system modeled after the Japanese school system, with elementary, middle schools, and high schools culminating in Keijo Imperial University (1924–1946) in Seoul. The university was closed by the US military on 22 August 1946 and subsequently merged with nine other colleges to form Seoul National University. As in Japan, education was seen primarily as an instrument of “the formation of the Imperial Citizen.” The public curriculum for most of the period was taught by Korean teachers in a hybrid system focused on assimilating Koreans into the Japanese Empire as well as emphasizing Korean cultural education. Integration of Korean students in Japanese-language schools and Japanese students in Korean-language schools was discouraged but nevertheless increased over time. Korean history and language would be taught alongside Japanese history and language until the early 1940s.

In 1921 there were government efforts to strengthen Korean media and literature throughout Korea but also in Japan. There were incentives for ethnic Japanese to learn Korean, although this may have been as much to garner Japanese cultural acceptance as to foster cooperation between Koreans and Japanese. Japanese policy moved more aggressively toward cultural assimilation in 1938 (Naisen Ittai, “Japan and Korea as one”), with reform advocated to strengthen the war effort. By 1943 all Korean language courses had been phased out.

Although the Japanese education system may have been detrimental to Korean cultural identity, its introduction of universal public education was instrumental in the improvement of Korean human capital: near the end of Japanese rule, elementary school attendance was around 38 percent. The system produced hundreds of thousands of educated Koreans who later became “the core of the postwar political and economic elite” (Duus et al. 1996, 336). Against that assessment is the reality that adult literacy was around 22 percent in 1945; in 1970, by contrast, it had reached 87.6 percent.

Park Chan Seung (2010) argues that colonial Korea developed as a dualistic society. The main lines of differentiation were between an upper class, mostly Japanese but also comprising small numbers of Koreans, and a great majority of Koreans with a relatively few Japanese. In other words, the divide became multilayered, as much economic as ethnic. 52

Transgressions, erasures, architecture

While debate persists among historians about the beneἀts or disbene-ἀts of land reform, educational development, and economic modernization, one ἀnds few mentions of the colonial government’s actions to conserve elements of Korean culture. Instead the emphasis is on Japanese acts of destruction of Korean heritage and identity. Some of this conservation effort was to attract tourism, yet there were also real attempts to promote aspects of Korean culture; Korean studies were a signiἀcant focus in Japanese scholarship, and there were committed Koreaphiles even among the Japanese administrators. The remnant royal family was especially used in the conservation of traditional Korean culture and was allocated a colonial government budget for that purpose; cultural organizations were similarly funded.

Nevertheless it is the erasures and cultural distortions of the colonial society that have especially preoccupied postcolonial commentators and popular media. K. Itoi (2005) asserts that the Japanese destroyed an estimated 80 percent of the historic shrines, palaces, and cultural monuments of Korea; however, no sources are given for this somewhat arbitrary and seemingly exaggerated claim.52 Certainly there was heavy-handedness; there was also pillaging, with tens of thousands of cultural artifacts removed to Japan.

On what had been the grand Gyeongbokgung Palace forecourt the Japanese built their own multistory, domed, administrative headquarters, the Government-General Building, oriented to the north-south axis of Taepyeongno (Taihei Boulevard in the Japanese era) but at an angle to the remnants of the palace. Gyeongbokgung Palace had been destroyed in 1592 during the (Japanese) Hideyoshi invasion, whereupon the royal family and the court moved to the second or Changdeokgung Palace, which, with the third or Changgyeonggung Palace and the Jongmyo ancestral shrine constituted a vast integrated realm termed the “East Palace” complex (Korean Institute of Architects 2000, 56–63). The main Gyeongbokgung Palace had been rebuilt in 1867, and stood until its destruction (“deformation”) again along with much of the city following the Japanese inἀltration and then annexation in 1910. It had been mostly abandoned in the late nineteenth century with Kojong’s removal to Deoksugung Palace and, while its destruction by the colonial government had the effect of erasing the centrality of the monarchy, many of the removed buildings were demolished and reerected at Changdeokgung Palace with the agreement of the royal family.