The paucity of entertainment options in the 1970s is difficult to convey to contemporary South Korean youths, for whom a world without readily reproducible movies and music, and without cell phones, computer games, or leisure sports, is simply unimaginable.

— John Lie, K-Pop

In writing of the New Wave in Korean culture in the 2000s, Korean returnee John Lie describes a cultural amnesia—a loss of cultural memory and the erasure of a world of only a generation past. Yet this loss brings into existence new, almost bizarre ways to see Seoul and to imagine its future.

While the destructions of colonialism and war might lie beneath Seoul’s post-1953 profusion of blank boxes and the subsequent and seemingly unending expansion and proliferation of the megalopolis, such conditions can be seen also to have resulted in an episteme—a way of constructing knowledge and understanding of the world—that enables the unprecedented cultural explosion of present Korea. It is the notion of “creative destruction,” perhaps cultural succession, as an enabling condition for new invention. In the economic sphere this has most notably been articulated by Joseph Schumpeter (1950); in the cultural ἀeld, by Walter Benjamin, although it is ultimately to be traced variously to Karl Marx and Friedrich Nietzsche.1

The effect of the losses and distortions, together with the extraordinary acceleration of a superἀcial modernization, was to leave a void. The past has either slipped away, to be renounced, or to be imagined now in Disneyἀed simulacra—the reconstructed palaces and their soldierly reenactments being the most dramatic manifestation, but also 198the purchased antiquity of Woninjae Shrine, the Seohojeongsa, and their ilk. This modernization, however, occurred at a singular junction in the transits of the age—in that cusp between an e-economy and age (the electronics boom on which the Korean economic miracle rode), and the emerging k-economy (where the drivers are no longer the media but the contents of those media). Although the period from about 1990 would seem most starkly to mark this metamorphosis, there were certainly earlier foreshadowings. The void is thus not to be ἀlled but rather replaced by another space that is always already empty (cyberspace) and that constantly provokes the creation of contents. The world of remembered images is crosscut by another, of digital imagery and of cyberspace, also of the inἀnite possibilities that can explode to occupy that space.

The previous chapter was preoccupied with blankness, despite that inἀnity of advertisement boards and conical spires and crosses as an appliquéd montage—the eerily “modern” city of seemingly nondescript buildings and surfaces, as well as public spaces that could be found anywhere or nowhere (though often well and professionally designed in a conventional, academic “urban design” sense). The preoccupation that will emerge in the present chapter, however, is with contents. If Korean everyday life increasingly retreats into boxes—apartments in forests of high-rise concrete and glass, with the aged relegated to even meaner boxes, and leisure to the bang—what do Koreans listen to and watch in their reclusion? Equally signiἀcantly, what do other Koreans create as those new contents? The following is in four parts. The ἀrst addresses Seoul’s preoccupation with media and the new contents evoked by media; the second moves on to the phenomenon of Hallyu, the Korean Wave that has risen from that preoccupation. Part 3 turns to the global reach of the Korean Wave and K-pop, as Seoul and Korea metamorphose into an unprecedentedly new form of global hyperspace: the city and urban space are redeἀned. The fourth and ἀnal part of the chapter reprises the discussion of Seoul as assemblage from chapter 4, to consider the implications of a new urban geography.

Part 1

MEDIA AND THEIR CONTENTS

The claim is constantly made that South Korea is “the most wired nation in the world”—also the most wireless (Oh Myung and Larson 2011).2 By 2009, 95 percent of South Korean homes were connected to 199cheap, high-speed broadband Internet; its nearest rival was Singapore, with 88 percent.3 Seoul was the ἀrst city to feature DMB (digital multimedia broadcasting), a digital mobile television technology, and WiBro (wireless broadband), a wireless high-speed mobile Internet service.4 It has had a fast, high-penetration 100-megabits-per-second ἀber-optic broadband network, to be upgraded to 1 gigabit per second by 2012. In June 2011 the Seoul city government announced that it would offer free Wi-Fi in outdoor spaces, providing residents and visitors with Internet access on every street corner. By the end of 2011 all buses, subway trains, and taxis would be equipped to offer wireless Internet to passengers; by 2015 the network would cover 10,430 parks, streets, and other public places.5 An altogether new dimension is added to the realm of communication, in what can be seen as one of the most signiἀcant of all urban transformations—Seoul becomes a new sort of city.

The high concentration of people in tower blocks makes it easy to get ἀber-optic cable to much of the population. High-speed broadband is cheaply and almost universally available; by 2007 nine out of ten residents had mobile phones, and Samsung and LG continue to pump out the gadgetry to a voracious local market. Seoul also pioneered “convergence”: digital multimedia broadcasting was launched in South Korea in 2005. Other Asian cities—Singapore, Tokyo, and Hong Kong—are in pursuit. Singapore leads the challenge, especially on Internet access: in late 2006 the Singapore government said it would roll out free Wi-Fi broadband across the island and that by 2012 it would deliver wired broadband speed of up to 1 gigabit per second. That project continues. The rivalry between Korea and Singapore (and Hong Kong, Taiwan, the People’s Republic of China …) is a theme to which we will return.

Korea is also claimed to have been the ἀrst to succeed in commercializing online games, in the mid-1990s (Yi In-hwa 2006). As Martin Fackler has observed, “[O]nline gaming is a professional sport, and social life for the young revolves around the ‘PC bang,’ dim Internet parlors that sit on practically every street corner.” It is also alleged to be the ἀrst country to have to set up “boot camps” to treat Internet addiction among the young (Fackler 2007; also Song Do-Young 1998; Yi In-hwa 2006). Martin Fackler could report in 2007 that up to 30 percent of South Koreans under eighteen years old, or about 2.4 million people, are estimated to be at risk of Internet addiction; of these, about a quarter million probably show signs of actual addiction (Fackler 2007). To address the problem, a network of 140 Internet addiction counseling centers had been established by the government; treatment programs had been introduced at some one hundred hospitals; then, in 2007, the Internet Rescue Camp program was initiated, 200run on quasimilitary lines, part boot camp and part rehabilitation center. Korea is certainly not unique in having the problem of youth addiction to cyberspace; however, as it is in the vanguard of the problem, so is it apparently pioneering efforts to address it.

A more recent observation of online gaming—as industry, as social and cultural phenomenon, as economic transformation, and ultimately as “empire”—is Jin Dal Yong (2011; also 2010 and 2013). Korean government policies encouraged the development of online gaming both as a cutting-edge business and as a cultural touchstone. Games are broadcast on television, professional gamers are celebrities, and youth culture is increasingly identiἀed with online gaming. As an industry, Jin recounts how Korean online gaming is increasingly global in its reach.

Songdo as “new ubiquitous city”

To observe the wired world raised to the next power, one can turn again to New Songdo, introduced in chapter 4 and ἀnely spruiked in the wondrous rhetoric of Marthin De Beer, senior vice president of Cisco Systems, the information technology contractor for New Songdo:6

If you’ve been to Songdo in Korea, it’s amazing what is going on there. Every home will have a Telepresence unit built in like a dishwasher. And it’s the developer that is putting those into new apartments as they get built out, because that is how education, health care and government services will be delivered right into the home. It will come to you. You don’t have to go ἀnd it. And that is how they will reduce traffic congestion and pollution in the cities….

[Y]ou can literally sit back on the couch and see your friends and family in life-size, full high deἀnition, right in your living room, and interact with them. It’s not a small computer screen. You get a full view of everyone. (Dignam 2010)

De Beer made this statement in a June 2010 talk at a Bank of America/Merrill Lynch Technology Conference focused, of course, on video, telepresence, and networks. More interesting, however, was the talk’s subtext: what are the social and psychological implications of reality’s replacement with its virtual substitute? De Beer spoke of such “presencing” with one’s banker, lawyer, accountant, tutor, “because now I can interview and hire a tutor that may be in a different city for my kids, and it’s the best possible tutor I can ἀnd.” However, he goes no further. The real effects on the individual, isolated in a world of virtual 201reality, are yet to be observed. Dignam’s comment: Songdo may be able to show us the art of the possible.

Lest the transformative aspects of Songdo overexcite, it must be emphasized that, for Gale, Cisco, and its other proponents, this is an investment, and expected to harvest a rich return. The observation of (New) Songdo in chapter 4 casts some doubt on the richness of that return. So we can observe another, also rhetorical, assessment of the project:

Cisco calls this Smart+Connected Communities initiative a potential $30 billion opportunity, a number based not only on the revenues from installation of the basic infrastructure but also on selling the consumer-facing hardware as well as the services layered on top of that hardware. Picture a Cisco-built digital infrastructure wired to Cisco’s TelePresence videoconferencing screens mounted in every home and office, with engineers listening, learning, and releasing new Cisco-branded bandwidth-hungry services in exchange for modest monthly fees. You’ve heard of software as a service? Well, Cisco intends to offer cities as a service, bundling urban necessities—water, power, traffic, telephony—into a single, Internet-enabled utility, taking a little extra off the top of every resident’s bill. (Lindsay 2010)

The ἀnancial model, it seems, is akin to that of ancient rent farming. One must wonder, however, if Cisco picked the right farm, and whether Gangnam or elsewhere in Seoul might not have been a smarter target.

Media and the uncertainties of new invention

There may be a warning for enterprises like Cisco and projects like New Songdo in the uncertainties that accompany the endless proliferation of new media. Although this chapter is more concerned with the contents than with the media conveying them, it is instructive to note the recent dilemmas facing the PC bangs.

Some think that the age of the bang may be passing. Yoon Ja-young (2012) cites a survey of Internet café owners (by the Korean Federation of Small and Medium Business) showing 64.5 percent of them in deἀcit; one in three was barely breaking even, and only 1.8 percent saw a proἀt. Where there were an estimated 24,000 Internet cafés in Korea in the early 2000s, by 2012 the ἀgure was around 15,000. The fall is attributed to the expansion of smart devices as well as to the provision of free Wi-Fi in coffee shops. Accordingly the Internet cafés 202are increasingly relying on online game players, although the games are also making the shift from desktop to mobile devices. Yoon cites a white paper on Games by the Korean Creative Content Agency:7 while Internet cafés took 29 percent of sales in the 2009 games market, that fell to 19 percent in 2011 and was expected to be only 12 percent in 2013; in contrast, as smart devices become smarter, sales of mobile games were projected to have doubled between 2009 and 2013.

The uncertainties of new invention continue: the annual flood of new mobile devices, and of new games to be played on them, has continued to place old technologies and bangs under yet further pressure; so 2016 saw the release of the ἀrst commercially available virtual reality headsets, preἀguring the next wave of both consumer frenzy and youth distraction. Multiplayer games proliferate as evolving technologies enable ever-increasing connectivity between devices, thereby threatening the bangs and accordingly the spaces of the city.

From media to content

Nowhere have the transpositions of reality been more brilliantly manifested than in the extraordinary creativity of Korean electronic art. The National Museum of Contemporary Art, Korea at the base of Mount Cheonggyesan in suburban Gwacheon, as an example, is in the main a gallery of electronic art and imagery. It is set in a forest in low foothills of the main mountain range and was designed by architect Kim Tai Soo. Though thoroughly modern in its starkly geometric forms, there are apparent references to ancient Chosun-era monuments. The complex might be seen as a ἀne reflection of the quest for a modern Korean identity—and perhaps also as a counter to other expressions of that identity (Gyeongbokgung, Seohojeongsa, the reenactments of Chosun pageantry at the variously restored and reconstructed palaces).8 It is in its electronic art contents that the real challenge to an understanding of Korea is to be found.

In 2001 the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, mounted a major exhibition of Korean art, again digital and diversely electronic, especially celebrating the seminal work of Korean composer and video artist Paik Nam June (1932–2006). From February to April 2000 Paik’s work had similarly dominated the New York Guggenheim (Hanhardt 2000). Paik Nam June is widely considered “the father of video art” (Lee Yongwoo 2006; Kal Hong 2011, 85). The ἀrst phase of Paik’s musical output began in 1947 with conventionally notated works and the Korean-flavored sounds of his youth. The seminal work of Paik grew out of the 1960s flowering of a Korean sense of impending freedom and its potential for a radical break. His ἀrst emblematic work 203was TV Buddha, a TV set and a statue of the Buddha are placed facing each other, as the Buddha contemplates his own image picked up by the video camera placed above the TV set (Lee Yongwoo 2006).9 Both modern electronic technology and ancient Buddhist contemplation are set to deconstruct each other—Korea is itself deconstructed. There is something of a contradiction here, however: while Paik’s work is widely seen as seminal to the direction of modern Korean culture, he spent much of his time from the 1950s on in Germany, the United States, and Japan, and was a founding member of the internationalist Fluxus Group, so that the idea of Korean cultural rebirth falls into the framework of emerging, internationalist, avant-gardist culture.

Paik’s artistic debut was with a solo exhibition in Wiesbaden, Germany, in 1963, titled Exposition of Music-Electronic Television. Twelve television sets were scattered through the exhibition space and used to create unexpected effects in the images being received. Paik moved to New York in 1964 and began working with cellist Charlotte Moorman to combine video and performance. In their installation TV Bra for Living Sculpture, television sets were stacked in the shape of a cello; as Moorman bowed the television sets, there were images of her playing, collages of other cellists, and live images of the performance. Paik also incorporated television sets into a series of robots, sometimes built from bits and pieces of wire and metal, and later from vintage radio and television sets. He laid out a large garden in an exhibition space and planted dozens of television sets in it; he also hollowed out a television set and ἀlled it with plants rooted in earth. To this he gave the title TV Plant. The implication seemed to be that, while technology itself was not necessarily of substantive relevance, it could be brought to some organic place in general culture by our contemplating the nexus (or its lack) between technology and nature (Hanhardt 2000; Hanhardt and Hakuta 2012). On New Year’s Day 1984 Paik broadcast, via international satellite, “Good Morning, Mr. Orwell,” which he had composed in Paris and New York, to negate the pessimism of George Orwell’s (1903–1950) novel 1984, which had warned of the oppressive power of television in a totalitarian state. The show was aired simultaneously in major urban centers, including Seoul (Kal Hong 2011, 140n1). There is no mention of it being aired in Pyongyang.

For the 1988 Olympic Games in Seoul, Paik built a tower from 1,003 monitors, titled ἀ e More the Better;10 it now stands in the center of a spiral ramp in the National Museum of Contemporary Art, Korea. The “1,003” symbolizes October 3, Korea’s National Foundation Day—the foundation of the ancient Gojoseon, the ἀrst Joseon or Chosun. The work is not merely at the center of the Museum of Contemporary Art; the museum is effectively built around it. ἀ e More the Better is now a national monument (ἀgure 5.1) (Kal Hong 2011, 85). 204

FIGURE 5.1 Paik Nam June, The More the Better, 1988. The assembled television sets are from an earlier age and technology—they are no longer manufactured and so cannot be replaced as they fail. The blank screens thereby measure the passing of their age and its technology so that The More the Better will in time become a ruin—a dead, electronic monument to a past time. Photographed 2012.

205Paik was commonly called the founder of video art, philosopher of technology, composer, poet, information artist. Lee Yongwoo notes Paik’s assertion that “the role of the artist was to anticipate the future.11 He believed that when technology could be used like an artist’s brush, technology would be humanized so that it could be applied for the true beneἀt of mankind [sic]” (2006, 39). While he certainly searched widely for Korean subject matter, it would be mistaken to ἀnd nationalism in this quest. Similarly, while it was scarcely coincidental that a Korean artist would be imbued with the excitement of video technology in Korea’s decade of technological embrace in the 1960s, his signiἀcance (as both a Korean and a global artist) was in his turn to the potential content of this new technology—as well as in his turn to philosophical reflection on the relationships of power emerging in the new age.12

Aftermath to Paik Nam June

In Yongin at the southern extension of Seoul, on the Bundang subway line, sits the Nam June Paik Art Center. The idea of an institution dedicated to Paik was discussed with him starting 2001. In 2008 the center was opened to the public.13 Accommodating exhibition halls, creative activity spaces, and archives, it is described as “a space of ‘introspective anarchy of inἀnite light and life,’ … a venue for the ‘escape from enlightenment,’ going beyond enlightenment.” Paik, it is asserted, did not regard video and television as “a means for communicating messages, but as an explosion of time, instead creating a space for mandala-based televisuals, and for participation by the public where ‘consilience’ among heterogeneous ἀelds can take place.”14

There are younger followers in the tradition that Paik pioneered. Moon Kyungwon and Jeon Joonho project video installations in News from Nowhere (2012), retracing William Morris’ 1890 novel that envisioned an agrarian society in which the divisions between art, life, and work were erased. Here, however, the erasure is to be of the borders between science, architecture, product design, engineering, philosophy, and religion in a postapocalyptic future—after the North-South apocalypse.15

The ἀrst generation of Korean modern artists represented by Paik Nam June was followed by a new generation of distinguished artists working in a variety of media. These include Chang Ree-seok, Chang Doo-kun, Paek Young-su, Chun Kyung Ja, Kim Tchang-Yeul, and Suh Se-ok. More recently, the Korean art world is represented by a group 206of painters and sculptors such as Chun Kwang Young, Park Seo-bo, Lee Jongsang, Song Soo-nam, Lee Doo-shik, Lee Wal-jong, Youn Myeungro, Lee Il, Kang Ik-joong, Lim Ok-sang, Kim Young-won, and Choi Jong-tae, all of whom have achieved international recognition.16 Also notable for its urban focus, on North Korea rather than Seoul, is the photography of Back Seung Woo.17 The diffusion both of media and of forms of expression might be linked to the example of Paik’s “exit” from convention, but also to the explosion of art spaces and zones in the city recounted in chapter 4.

Korean official culture exhibits a wider embrace of the deconstructive power of digitally transmitted content. Sunday 15 April 2012 was the one-hundredth birthday of Kim Il-sung. From its permanent collection, the National Museum of Contemporary Art, Korea reprised a video art installation by William Kentridge (South African, b. 1955), I am not me, the horse is not mine (original 2008). The phrase was commonly a peasant’s insolent reply in Czarist Russia to deny responsibility for actions; it has subsequently become a Russian proverb. The theme of the installation was based on Gogol’s absurdist ἀ e Nose: television screens depict Constructivist cartoons, including a cartooned Stalin, with one screen displaying (in English) the text of the plenum of the Central Committee of 26 February 1937 that condemned Bukharin. The proclaimed purpose of the work is “to lay bare the institutional violence of Stalin’s regime.”18 In Korea it is safe to assume that the conjunction of such a display with Kim Il-sung’s centenary was not coincidental.

It is similarly not coincidental that Korea can be seen as enmeshed in the vanguard of the new cyberpolitics (Lee Eun-Jung 2004). In the context of increasing collusions between the political parties and the formal press (the Third Estate with an increasingly compromised Fourth Estate), there are inserted the ever-more-subversive Internet-based web journals—weblogs, or blogs—claiming the space of the Fifth Estate.19 So the Korean OhMyNews online, an interactive news “paper,” was founded in February 2000 and claims to have been the world’s ἀrst “citizen journalism” outlet. Its motto is “Every Citizen is a Reporter,” and in 2004 it was reported as having a readership of two million, and over 26,000 registered “citizen journalists.” On some accounts it was credited with playing a key role in bringing President Roh Moo-hyun to office in the 2002 elections (StarIn Tech, Malaysia, 23 November 2004 1–3;20 Yun Seongyi 2003; Oh Myung and Larson 2011, 156). Yun Seongyi (2006, 57) elsewhere reports that Roh’s home page was logged on to by more than 300,000 “netizens” every day, and by 860,000 on the day of the election, quoting Britain’s Guardian to the effect that “South Korea will stake a claim to be the most advanced 207online democracy on the planet with the inauguration of a president who styles himself as the ἀrst leader fully in tune with the Internet.” While there are complaints that the Internet is unable to communicate the uplifting policies and messages of the Third Estate, that of course is precisely the point: its character is in its anarchic fragmentation and dissemination, and in its disorder. Its effect rather is “debunking, reinforcing, and cooling” (Yun Young Min 2003). Late modern politics, like late modern Protestantism (chapter 3), “flies apart.”

Cinema

As “debunking” and “flying apart” characterize both modern Korean politics and the trajectory of Korean “high-culture” music and visual arts, so too popular culture—albeit sometimes unintentionally. All arise in the context of an enabling episteme of distortion of memory, reimagining of the past, naturalizing of material culture, and transposition of reality (a theme for chapter 6). Thus, indeed, can one view the extraordinary phenomenon of Hallyu, the “Korean Wave.” Although the term refers to the popularity of South Korean popular culture that swept through East and Southeast Asia around mid-1999, its antecedents go back to the long evolution of the Korean cinema industry.21

There had been a brief Golden Era of Korean silent ἀlms in the years 1926–1930, sparked by the 1926 release and critical success of Na Woon-gyu’s Arirang. Although the ἀlm did not have an explicitly political message (no nationalism, no Japanese bashing), the common use of a live narrator, or byeonsa, at the theater who could inject his own satire and criticism of the occupation, would give it a political subtext invisible to government censors. For all that, Arirang was seen by the police as a blatant attack against Japanese rule and accordingly banned (Eckert et al. 1990, 295).22 More than seventy ἀlms were produced in this time, in a complex and evolving process of interaction between Japanese and Korean ἀlmmakers, whereby “the latter played key roles in the formation of Korean cinema both despite and in conjunction with the heavy-handed influence of Japan’s ἀlmmakers, technology and capital” (Chung Chonghwa 2012, 138).23 After 1930, however, the domestic ἀlm industry was virtually shut down due to censorship and mounting Japanese oppression; from 1938 on, all ἀlmmaking in Korea was done by the Japanese; by 1942 the use of the Korean language in ἀlms was banned (Min Eungjun et al. 2003).

After 1945 there was a brief outburst of production with “freedom,” understandably, as the guiding theme, although this abruptly ended with the 1950–1953 civil war.24 The real rebirth began in 1955, enjoying support from the Syngman Rhee government, and then 208subsequently in 1960–1961, a year of unprecedented freedom in the period between the Rhee and Park administrations. With Park, heavy censorship and regulation returned—“family values” were to be encouraged, while any hint of pro-Communist messages or obscenity was to be purged. Despite the constriction, ἀlm production, ἀlm quality, and audiences increased throughout the 1960s to give Korea a strong cinematic culture; the 1970s, by contrast, marked a period of suppression and decline. “Political correctness” would rule cinema production. This decline was further hastened by “free” trade agreements with the United States that allowed an unrestricted Hollywood flood (Lee Hyangjin 2000; Kim Byeongcheol 2006).25 Steven Chung (2014a) sees Shin Sang-ok (1926–2006) as arguably the most important Korean ἀlmmaker of the postwar era, having directed or produced nearly two hundred ἀlms in a decidedly melodramatic genre. These included the highly regarded A Flower in Hell (1958) and ἀ e Housemaid and My Mother (1961). However, by around 1972 his career was floundering in the wake of the dictatorship’s censorship and the Hollywood flood, only to revive in spectacular fashion after 1978—we resume that story following.

Kathleen McHugh and Nancy Abelmann (2005) identify the 1955–1972 period as the “golden age” of South Korean ἀlms and the period of a “ἀrst renaissance” (of that earlier golden era of 1926–1930?).26 The various papers that McHugh and Abelmann bring together focus on a number of intersecting themes: transnational connections (the debt to Hollywood but also to Italian Neorealism, French art, and even Mexican cinema), war and the plight of women (a strong emotional attachment to MGM’s Waterloo Bridge of 1940), the dilemma of syncretization, and the indigenization of Christianity in Korea and its entanglement in the representation of women (McHugh and Abelmann 2005). These are themes that reemerged in the “second renaissance”—the “New Wave” Korean cinema—beginning in the 1990s.27 This latter McHugh and Abelmann identify with tendencies toward both auteurism and melodrama, a critique that is also taken up by Moon Jae-cheol (2006). Where in Western cinema auteurism—the celebration of the author, the director, and originality—took the form of emphasizing ἀlm as art, in Korea the industry took such an idea as the operator for challenging the Korean ἀlm institution. The director and his or her ἀlm would challenge the institution and thereby its protecting, wider society. The strategy of the New Wave was to hybridize the two concepts of auteurism (the art-house cinema that engages the humanist vision of a single writer-director) and realism.28 Hybridity is also emphasized by Kim Kyung Hyun (2011b, 186): “By fully embracing Hollywood, rather than rejecting it, their works display hybridity 209that equally engages national identity and global aesthetics, art and commercialism, conformity and subversion, and narrative coherence and stylistic flair.”29

Moon Jae-cheol further argues that the New Wave’s view of history was melodramatic: “These ἀlms reproduce the past through the lens of nostalgia, thereby emphasizing a sense of loss in the present. As Fredric Jameson said about postmodern ἀlm, there is evidence of a regression that cannot imagine a new history” (Moon Jae-cheol 2006, 44). A melodramatic imagination, following Peter Brooks (1976), would be one that seeks hidden moral values in a world in which values are being destroyed—“primal secrets or essential nature has been suppressed and awaits liberation” (Moon Jae-cheol 2006, 48; on the melodramatic in Korean cinema, see also Lee Young-il and Choe Young-chol 1998).30 Moon goes on, however, to suggest that there was, by 2006, an emerging post–New Wave cinema in which the melodramatic was being supplanted by an ironic imagination and view of history. Irony builds on ambiguity of meaning—rather than look for hidden meaning in history, irony would point to the uncertainty of history by showing that positive truth is not possible.31

If Moon’s observation has validity, then the suggestion would be that there can be detected, in the sensibilities of recent Korean cinema, some shift away from the preoccupation with nostalgia and loss in Korean society that has been a constant theme of chapters 3 and 4. The uneven shifts between nostalgia and irony preoccupy modern Korean literature embedded, as Stephen Epstein (1997) observes, in and reflective of historical context. One might reasonably question: is any such tendency to be observed in uses of the built environment to represent “the Korean condition”—in the neo-Modernist landscape of Cheonggyecheon or perhaps the siting and forms of the National Museum of Contemporary Art, in contrast to the nostalgic (melodramatic) reconstructions of palaces and palace guards? Where the historical reconstructions of Kwanghuamun and Gyeongbokgung Palace might be seen to express a melodramatic imagination, the reinvention of Cheonggyecheon is ironic. Irony also arises in the hyperspatial phantasmagoria—albeit accidental—of New Songdo? Are we likewise seeing a “new wave” urban design? We will return to this question.

The post-1997 explosion in Korean ἀlm production, as well as in both its domestic and international adulation, represents a breakthrough in artistic and marketing terms but is also, however, a phenomenon needing explanation. It might be seen, simplistically, as an issue of quality, as well as the sudden release of previously suppressed ideas and creativity. A partial explanation may also relate to a recurring theme of the Korean people’s suffering as a result of their division 210and the longing for reuniἀcation. Arguably even more signiἀcant has been a hard, uncompromising “values” focus that marks New Wave Korean ἀlms. In writing on the “independent ἀlmmakers,” Park Young-a (2011) has drawn special attention to director Kim Dongwon (b. 1955), whose documentary Sanggyedong Olympics exposed the violence of the “eviction squads,” local gang members hired to clear the slums in preparation for urban beautiἀcation for the 1988 Olympics. Deeply moved by the work of radical Catholic activists among the poor, Kim went on to direct a series of documentaries to unveil the condition of Seoul’s shantytown residents. He went to live among his subjects but in his ἀlms avoided identiἀcation of individuals, instead relying mostly on long shots of groups of residents, to thereby depict the shantytown as “a community with a uniἀed future and hope” (Nam Tae-je and Yi Jin-pil 2003, 35, cited in Park Young-a 2011, 193). Chris Berry (2003) has invoked the idea of a “socially engaged mode” in describing Kim’s and related Koreans’ work as the antithesis of a “commodity mode” of most Western documentary making, directed instead to the construction of a “counterpublic sphere.” The avant-garde Oasis (2002) highlighted the plight of the handicapped and Koreans’ inability to understand and accept them; Oldboy (2003) experimented with themes of psychological madness and sexual distortion; Samaritan Girl (2004) was about a teenage prostitute. My Sassy Girl (2001) was a romantic comedy, signiἀcantly based on a series of blog posts adopted into a ἀctional novel.32 When released throughout East Asia, My Sassy Girl became a megablockbuster in Japan, China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong; it was also strongly received through Southeast Asia.33

If Shin Sang-ok is seen as Korea’s “most important” ἀlm director of the late 1950s and 1960s, then the “best and most challenging” might be Kim Ki-young (1922–1998), known for his intensely psychosexual and melodramatic horror ἀlms, often focusing on the psychology of their female characters. The most revered of these was ἀ e Housemaid, released in 1960. It was a domestic thriller telling of a family’s destruction through the introduction of a sexually predatory housemaid; it was lurid, expressionistic in contrast to the prevailing realism, set in an eerie house, and preoccupied with sexual obsessions, rats, and murder. ἀe Housemaid was produced in that brief period of relative freedom following the end of the Syngman Rhee regime in 1960 and before the rise of Park Chung-hee in 1961 and new restrictions and censorship. To mark the ἀlm’s fiftieth anniversary, director Im Sang-soo was invited to produce a remake of the original; the result, ἀe Housemaid (2010), seeks to explore the change in Korean society over that time. Like the 1960 version, the 2010 ἀlm is melodramatic, even absurdist, an erotic thriller. In a 2010 interview, Im observed that, despite the obliteration 211of six decades of colonial oppression and the three years of civil war, there had emerged in the late 1950s a new middle class that, “while quite ordinary by Western standards,” could afford to hire uneducated girls from the destitute countryside as housemaids. This had been the economic background to Kim’s masterpiece. By 2010, however, only a limited class of the superrich could afford live-in housemaids in suddenly affluent Korea. The superrich, says Im, “are very separate from normal people, but they rule our society politically and economically from behind the scenes. I want to know who they really are, how they live, what they think. This ἀlm is part of my study of the superrich in Korea.” It is a class that lives isolated, in a cultural vacuum—“they just copy the European traditional rich using new money. But, you know, when you copy someone else’s life, inside there is only emptiness.”34 The 2010 ἀlm is far more than a remake; rather, the two versions are to be seen together, as dialectical images that expose one aspect of the evolution of the Korean class structure. Signiἀcantly, both deconstruct “family values,” a constant preoccupation of the New Wave in Korea.

Bong Joon-ho’s immensely successful ἀ e Host of 2006 presents a very different take on family values and domestic life, here interwoven with the blockbuster–monster–special effects genre: an unremarkable family is thrust into the extraordinary events of a human-consuming monster in Seoul’s Han River.35 The ἀlm becomes a commentary on the implications of America’s military presence in Korea and of the complicity of the Korean political establishment. The monster, we are to assume from the ἀlm’s cues, is linked to American biological experimentation and the aftermath is a tangle of official efforts at disinformation. Bong Joon-ho has rejected any charge of anti-Americanism, however: “In the broad sense, to compress it or simpl[if]y it as an anti-American ἀlm, I think that’s not correct because there’s always a history of political satire in the sci-ἀ genre. If you look in the broad sense, the American satire is just one part of it. There is also the satire against the Korean society and, even further, the whole system that doesn’t protect the weak people. That’s the greater flow of satire in this ἀlm, not that one part of anti-Americanism” (Bong Joon-ho, quoted in Blodrowski 2007). The seeming mirage of anti-Americanism won it the rare distinction, for a South Korean ἀlm, of official North Korean praise. The North Korean pleasure, however, may have derived from a lack of sophistication in reading the satire: the ἀlm is almost exclusively set along the banks of the Han River; the architecture is dark and futuristic; the river—the always feared, forever threatening pathway for that other monster of North Korean invasion—is constantly menacing. Or is there yet another reading of the river? Bong Joon-ho writes, “The Han River: The River has flown with us and around us. 212A fearsome Creature makes a sudden appearance from the depths of this river, so familiar and comfortable for us Seoulites. The riverbanks are constantly plunged into a bloody chaos. The ἀlm begins at the precise moment, in which a space familiar and intimate to us, is suddenly transformed into the stage of an unthinkable disaster and tragedy.”36 Above all else, ἀ e Host may be seen as a commentary on the ambiguity of the Han River in the minds of Seoul people—“familiar and comfortable,” as Bong insists, yet dark and threatening as he depicts it, deἀning the city yet also potentially the city’s path of impending destruction.

Kim Kyung Hyun suggests an explicitly architectural reading of ἀ e Host. Bong is seen to be preoccupied with an evolving landscape “mauled by the hurried pace of industrialization and modernization.” “Bong’s depictions of landscape often show nature beyond repair. Countryside towns and farms are invaded …; a wide-open vision of green forest is obstructed by rows of apartment buildings, which are ubiquitous in Korea …; the Han River is inhabited by a monster and threatened by the sprawling cityscape …; and a mountain is razed by miners and builders who extract rocks from it to make cement and other construction materials” (Kim Kyung Hyun 2011b, 190).37

Bong’s ἀlms are seen as depicting “the global metropolis that is Seoul’s parasitical dependence on nature and its destruction of ecological harmony…. [T]hese ruined landscapes are exploited as both the generic ingredients for his crime mystery, horror, and comedy, and the effective sites of new virtual realities” (Kim Kyung Hyun 2011b, 191).38 ἀ e Host portrays a virtual city drained of its crowds. The dense masses of people who will occasionally occupy the riverbanks are absent. The absence, however, does not restore nature but instead places the viewer in a phantasmagoric state—a “perversion” of the landscape. Only when the city becomes virtual—reimagined as a barren, abandoned landscape—“does the presence of flâneurs (city strollers) and nomads become conspicuous” (compare this with my own flâneur-like stroll through the empty, abandoned streets of New Songdo, also drained of crowds, phantasmagoric, in chapter 4). Kim invokes ideas from Deleuze and Guattari (1987): vagabonds, whose “dwelling is subordinated to the journey” and here occupy “the striated spaces of sewers, tunnels and concrete holes,” become crucial. In ἀ e Host, spaces of everyday urban life—convenience stores, corporate high-rises, gigantic parking garages, sewers—become what Deleuze and Guattari call the “operation of the line of flight,” delineating a movement along which both deterritorialization and reterritorialization must occur. Such spaces in Seoul are constantly invoked as “lines of flight” (Kim Kyung Hyun 2011b, 196–197). 213

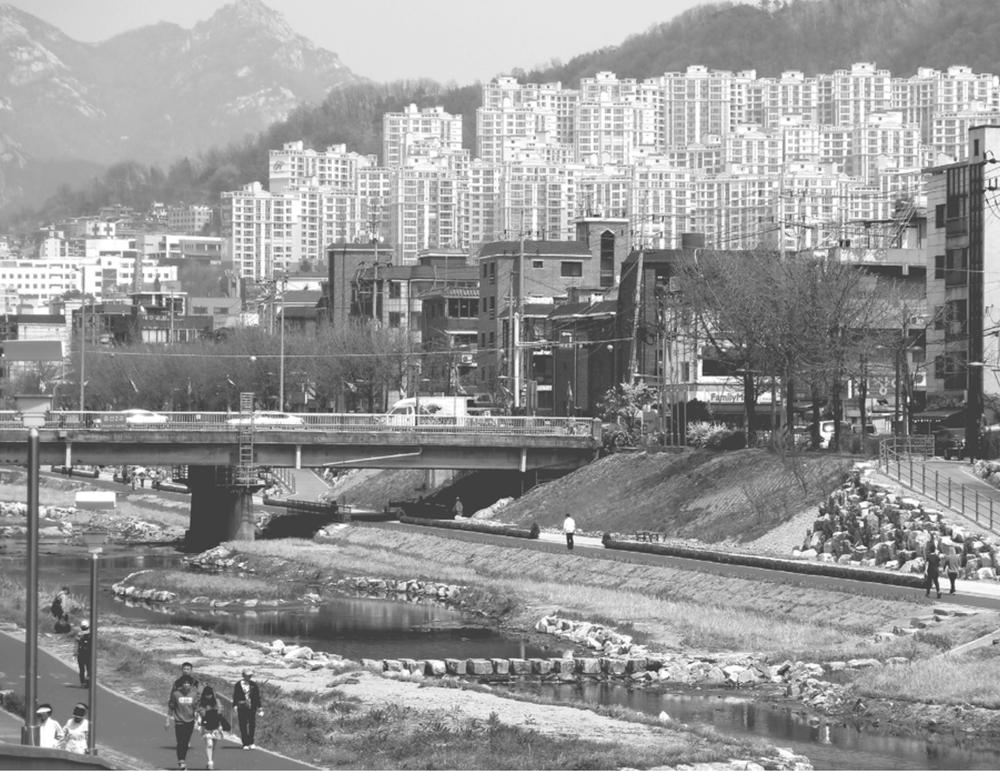

It is not difficult to ἀnd dark images of real (surreal?) Seoul that match the dark vision of ἀ e Host—the winter snow, the ice, and the mists ensure that. Observe ἀgure 3.9 in chapter 3. A more sundrenched, spring-blossomed image can be more suggestive: Digital Media City, some seven kilometers west of the old city, is yet one more of the futuristic “new cities” that inhabit some imagined, dreamed vision of a future Korea.39 There are the majestic mountains and the small stream of the Bulwongcheon River that old villages would have lined and that the mean, brown-brick, 1960s and 1970s modernity would have supplanted. Then, behind this brown-brick, boxland Seoul and blocking out the majesty of the green mountains and the reminders of mountain temples and shamanic retreats are now the walls of Seoul’s ubiquitous high-rise apartment towers. Older aerial photographs reveal the stream as a drainage line—anecdotally polluted with industrial waste, an example of Bong’s “nature beyond repair.” Yet, look again: a 2012 image reveals new landscaping of the stream.40 The new plantings, sculptured banks, stepping-stones, waterside pathways, benches, and exercise equipment (a constant preoccupation) are part of a wider program to “bring nature back”—likewise the Cheonggyecheon reconstruction, as well as the vast Hangang riverside parks (ἀgure 5.2).

The expressed artiἀciality of these landscape reconstructions, sculptural rather than fake-naturalistic, puts them in the same dramaturgical realm as Bong’s deconstructive vision in ἀ e Host. They present for the most part a hard, unromantic nature, evoking an ironic rather than a melodramatic imagination, in the sense argued by Peter Brooks, above.41

Neo-Seoul

There is another apocalyptic vision of a future Seoul, also negotiating that dialectic of the melodramatic and the ironic and to be set against its engagement in ἀe Host. It emerges as one of many layers of Cloud Atlas (2004), a novel by English author David Mitchell, subsequently adapted to a German American ἀlm (2012).42 Nea So Copros is an immense, economically powerful, corporate nation centered on a uniἀed Korea, where Korean-style neocapitalism has run amok in seemingly the world’s last bastion of “civilization,” albeit ambiguously deἀned. Its capital is Neo-Seoul. “Nea So Copros” is a corruption of “New East Asian (Sphere of) Co-Prosperity”—the imperial Japanese vision is ἀnally achieved, albeit with a Korean hegemony. The land in Nea So Copros is mostly uninhabitable, rendered toxic by industrial waste and nuclear accidents (Fukushima multiplied). Society is strati-ἀed in a Confucianist apotheosis, ranging from Xecutives who appear 214to control Nea So Copros as part of the juche (a reference to the philosophy of the Syngman Rhee regime, also to that of present North Korea) to consumers to the relict poor and down to genomed clones known as “fabricants,” manufactured for speciἀc tasks, such as serving food and cleaning up radioactive water, but kept from intellectual development.

FIGURE 5.2 Digital Media City, 2012. This image effectively summarizes the city: the mountains had restricted the city’s development to the small valleys in the era of the “Miracle on the Han” (the dreary boxlike buildings along the stream); the later, wall-like arrays of apartment towers engulf the lower slopes; most recently, the stream itself is transformed from industrial drain to overdesigned, landscaped, recreational walkway. Digital Media City claims to be the generator of an entirely new, digitally enabled age.

It is Neo-Seoul and its ἀlmic graphics that especially challenge any reading of the present city.43 The year is 2144, and the levee walls and floodgates erected to protect Seoul from the rising sea levels have long since failed. Old Seoul has been submerged, and the abandoned metropolis is now a slum megasociety with shack dwellings growing up like a coral reef on the levee walls and immense shantytown flotillas built on and around the half-sunken skyscrapers bridged by salvaged 215steelwork from ancient, wrecked oil rigs. Here reside the poor, servicing the glittering Neo-Seoul sprawling up and between the mountainsides above. Even in the murk of the world’s industrially destroyed atmosphere, Neo-Seoul shines brilliantly, amid holographic building “skins” and illuminated freeway ribbons; there are factory ships manufacturing fabricants, and others industrially slaughtering them to produce food for new fabricants.

Mitchell’s novel has been much acclaimed; the ἀlm and its graphics have been more controversial. It has been observed that the depicted skyscrapers of Old Seoul seem more Hong Kong than Seoul; Shanghai and Midtown Manhattan also seem to be represented. Neo-Seoul is also derivative of Blade Runner (whose implication seems to have been that civilization had run out of new ideas and could now only pillage its past—again, an ironic comment on “old” Seoul).44 Nea So Copros is a corporate state, and Neo-Seoul is festooned with the advertising that similarly decorates Old Seoul of the present. The advertising is in Korean, though mostly upside-down.

Two concluding points can be drawn from the fable of Neo-Seoul. First, it might usefully be read as an ironic metaphor on the debates of present Korean historiography: the colonial era returns, but it is now Korea colonizing a devastated Japan; neoliberalism has gone berserk; there is democracy, but only corporations have the vote; Confucian hierarchy reigns. The upside-down script is appropriate for an inverted history. Second, this is a parable of Seoul and Seoulites, but it has been told by an English author and German ἀlmmakers, albeit with Korean (and American) actors. The cultural colonization might bemuse the culturally colonized (as might that represented in the present book), yet it also highlights Seoul’s global appropriation, always reciprocal. The intrusion of skyscrapers from Hong Kong, Shanghai, and elsewhere is itself metaphoric of the hybridizing force of globalization.

Inescapable discursus (1): Dark passages

The dark undertones running through ἀ e Host will draw unwelcome attention to another, darker space of Seoul, of subterranean or submarine passages of inἀltration, invasion, “lines of flight,” and, indeed, the terror of the next erasure. The Han River is the ever-threatening passage for feared North Korean frogmen or midget submarines. A further recurring feature of Seoulites’ forebodings are the “water panics”: the ἀrst was in 1986, when it was discovered that North Korea was building massive dams on the Imjin River, a tributary of the Han, giving it the potential to release massive walls of water into the Han and thereby to flood Seoul. In September 2009, floods were suddenly sent, 216without warning, toward Seoul (Choe Sang-hun 2009). The image of a flooded “old” Seoul in Cloud Atlas may express yet another level of modern Seoulite paranoia.

The Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) presents other darkly threatening passages in the form of the North Korean tunnels. The ἀrst of the inἀltration tunnels was discovered in November 1974, a second in March 1975, and a third in October 1978—it is estimated that there may have been a total of seventeen tunnels. In March 1980, North Korean inἀltrators were killed trying to enter via the Han River estuary; in October 1995 inἀltrators were intercepted attempting to enter at the Imjin River, presumably thence down the Han River. Even the Seoul subway system is feared as a potential network for the dispersal of an invading force through (under) the city.

There was one (melo)dramatic moment that materialized these fears. On 21 January 1968, an elite North Korean commando unit launched the “Blue House Raid,” in an attempt to assassinate President Park Chung-hee. They got within one hundred meters of the Blue House before being thwarted. They had inἀltrated the DMZ by simply cutting through fencing, crossing the Imjin River, and entering Seoul, where they launched their attack. Having been defeated, they then attempted to disappear into Seoul’s mountains, with their informal settlements—other dark places.45

So much for the subliminal messages of ἀ e Host. One might also suspect that there are other messages to be read in the New Wave and in the culture more widely. Are the retreat to the goodness of “family values”—even in such terrifying portrayals as ἀe Housemaid—and the unquestionably devout turn to Christianity also to be seen as normal quests for reassuring certainties in an age of uncertainty?

Another cinema

There is another Korean cinema, with another great ἀgure behind it. In September 1967, twenty-six-year-old ἀlm buff Kim Jong-il was appointed cultural arts director of North Korea’s Propaganda and Agitation Department. Hollywood was young Kim’s envied realm of dreams, and it was Hollywood’s blockbusters that he would emulate as he took control of the cinema industry.46 Among his oeuvre are a bloody and sentimental three-hour-long adaptation of Sea of Blood about the Japanese occupation of Korea, and North Korea’s Gone with the Wind. Sensing, however, that all his achievements were trash alongside their American models, Kim conceived an extraordinary plan to bring real quality into his work. In 1978 his agents kidnapped renowned South Korean director Shin Sang-ok and his onetime wife, 217admired leading lady Choi Eun-hee. They were kept apart for four years, and then on 6 March 1983 reunited in a Kim-hosted banquet and “invited” to join him to collaborate on a new series of “quality” blockbusters.47

They made seven ἀlms together. There were typical nationalist melodramas, a light romance titled Love, Love, My Love, and the globally praised social-realist tragedy Salt (1985). Then there was the wonderfully ridiculous Pulgasari (1985), a Godzilla rip-off but presenting a terrifying monster with noble socialist sentiments. All were domestic hits beyond Kim’s expectations. Shin and Choi ἀnally escaped during a visit to Vienna in 1986; however, their subsequent careers were less stellar than Kim’s.48

Part 2

THE KOREAN WAVE

The New Wave South Korean ἀlms are distinguished by high production values that, signiἀcantly, were transferred into the realm of Korean television. Equally signiἀcantly, Korean ἀlms were characterized by their exploration of domestic social issues, their frequent concern with family-centered values, and their often unpredictable plotting. In all these ways they presented as “Asian” and “un-Hollywood” and came to foreshadow the Korean Wave.

The Korean Wave, also called Hallyu, from the Korean pronunciation of the term, allegedly began with the export of Korean TV dramas in the 1990s, which many Asian television companies purchased because they were impressive looking but cheap. As their exposure increased, the dramas resonated with audiences, and their popularity increased. By 2000 the Korean Wave was in full swing, and soon reinforced by iconic programs such as Jewel in the Palace and Winter Sonata. Although TV dramas dominated the “wave” and accounted for the vastly greater part of its earnings, the dramas were quickly matched in the ἀelds of cinema (the “New Wave” alluded to above) and popular music.49 The “wave” can be seen as a function of Korea’s sudden leadership in digital technology, where content—building on the long history of the struggle for freedom of expression in the cinema ἀeld—equally suddenly seized the opportunity to “ἀll” the new digital media. It was also a consequence of the realization of globalization and its corollary in Asian regionalism that hit Asia following the 1997 IMF crisis. 218

As Cho Hae-Joang (2005, 147) observes, “The global technology revolution and global capitalism prepared the system for the manufacture of cultural products and circulation within Asia, and formed the coeval space of capitalist Asia.” “Korea mania” initially hit China around mid-1999; Hong Kong, Taiwan, Vietnam, and Singapore soon followed. By 2001 the phenomenon was receiving increasing critical attention and discursive engagement.

In view of the seminal role of the TV dramas in the rise and spread of the wave, these need some explanation. The sixty-six-episode TV drama First Love had been produced in 1996 and was aired between September 1996 and January 1997. It has been ranked the highest-rated of all Korean dramas to that time. This and a variety of other drama series from the 1990s provided a platform for yet higher production values but also contributed to the gathering myth of Korean sophistication in media content.

Winter Sonata was the second part of the TV drama series Endless Love, directed by Yoon Seok-Ho and reprising the lead actors from the earlier First Love. The series comprised four parts: Autumn in My Heart (2000), Winter Sonata (2002), Summer Scent (2003), and Spring Waltz (2006).50 This second installment, in twenty episodes, originally aired from 14 January to 19 March 2002. The setting is the present day and the theme is the interplay of present-day Korean values. As the story alternates between Korea and the United States, however, there is an additional subtext of the nuanced differences between Korean and American values. While not reaching the domestic adulation of First Love, Winter Sonata’s appeal beyond Korea was certainly greater. The greatest international impact, however, came with Jewel in the Palace.

Dae Jang Geum, literally “The Great Jang Geum” but aired in the West as Jewel in the Palace, is a historical drama series set in Chosun Korea in the reigns of Kings Seongjong (r. 1457–1494), Yeonsan-gun (r. 1494–1506), and Jungjong (r. 1506–1544). It focuses on Jang-geum, the ἀrst female royal physician in the Chosun era, and stresses diverse themes of perseverance, the portrayal of traditional Korean culture, royal court cuisine, cultural practices, and traditional medicine. As in the tradition of Korean cinema, the presentation is characterized by high production values and the story by unpredictable twists of plot. The series was ἀlmed in ἀfty-four one-hour episodes and ἀrst shown on MBC channel from 15 September 2003 to 30 March 2004. It was reputedly the highest-rating TV series in Korean history. In May 2004 it began airing in Taiwan; in September 2005, in Hong Kong and China; in October 2005, in Japan; and subsequently throughout Asia, the Middle East, Africa, the United States, and Europe. 219It received high ratings throughout Asia and critical acclaim virtually everywhere.51

The Korean Wave is not all success. Kim Seong-kon has observed that there is a signiἀcant gap between the Korean Wave—more speciἀcally, K-pop—and Korean literature. The success of Shin Kyung-Sook’s novel Please Take Care of Mom (2009) stands out from a ἀeld of otherwise internationally unrecognized work. It is noteworthy that this novel is a story of family values, woman-centeredness, and motherhood—themes that elsewhere elevated the drama series to international acclaim. Kim Seong-kon’s suggestion is simple but debatable: this is no longer the age of translated texts; it is now the age of the TV series.52 This gap between genres would seem to have been tested in Shin’s next novel, I’ll Be Right ἀ ere (2014), in which the foreign and the esoteric are made familiar to each other, as the interpreter of emotion and experience is led to bridge any gaps between East and West.

ἀ e Korean Wave and architecture

If we see the Korean Wave as a fusion of international appropriation (a Koreanization of American and Japanese culture) with more indigenous Korean themes and practices, then we might well ask if any similar fusion is to be observed in present Korean architecture and in a reading of Seoul urban space. While such a hybridization might well be seen to have run through the second and third periods of Kim Swoo Geun’s work, reviewed in chapter 3, that was from an earlier time. So, what of the 2000s? Especially useful sources on recent Korean architecture and its provoked reactions are publications that have emerged from periodic exhibitions—notable are John Hong and Park Jinhee (2012), based on an exhibition at Harvard, and Caroline Maniaque-Benton and Jung Inha (2014), based on a small show at Malaquais School of Architecture (École nationale supérieure d’architecture Malaquais) in Paris53—as well as Kim Sung Hong and Peter Schmal (2008).

The reimagining (reinvention) of the culture is identiἀable in both the historical dramas and the historical reconstructions in the space of the city—the rebuilding of Gyeongbokgung Palace as its most dramatic element, but also the Chosun-clad guards and reenactments at the main palaces and other sites. The hordes of children who daily visit those sites on school excursions and photograph the brilliantly colored guards and each other in these settings will be mentally rehearsing stories from both the historical dramas and their school history lessons that would seek a continuity with Chosun, thereby to erase those earlier erasures from colonization and dictatorship—to reconstruct 220(reinvent) memory. Thus the nostalgic aspect of the Korean Wave ἀnds a place in a deeper historical reconstruction that is reinforced in both architecture and daily theatrical performance, as in the television dramas.

Todd Henry (2014, 217) suggests an interesting caution: by redirecting both Korean and international attention to the reimagined glories of a united peninsula under Chosun monarchs, the period immediately preceding Japanese rule, a periodization of history based on Japanese imperialist rule is privileged. The centrality of that rule and its postcolonial heritage is asserted.

There is also, however, that myth of national elegance that runs through the Korean Wave and its marketing. To walk the streets of Myeong-dong, Insadong, or Gangnam, or to visit the ἀner hotels, coffee shops, or tourist locales, is to have the myth conἀrmed—it is a city of the young, the tall, and the display of “style.” (By contrast, the markets, the myriad noncentral business districts, and the subway reveal an older, shorter, clearly poorer population—relicts from those hard times of the dictatorship and the still-only-incipient economic miracle; on the Seoul Station Plaza and at many other locations, there are the homeless, seemingly always sleeping, huddled in old coats and blankets, faceless.) Architecture again reinforces the Hallyu myth: Insadong and Gangnam in particular present brilliant displays of urban elegance. It is urban design at the highest level of competence. Much of this design ἀnesse is linked to the new precision and inventiveness that have been enabled by the computer—examples abound in the Seoul region.

In any ἀnal analysis, however, this display of “style” and elegance may carry Korean characteristics but is ultimately internationalist. Elegant young Koreans might dress in black and white more than young people elsewhere, yet such display is not uniquely Korean, nor can its genealogy point back to Korea. The power of digital technology in enabling a “more liberated” design culture, which may have been taken up vigorously in digitally focused Korea, yet its genealogy is overwhelmingly North American (most famously, architect Frank Gehry and the immense shock of Gehry’s Bilbao Guggenheim Museum, venue for Paik Nam June’s 2001 further shock on modernist sensibilities). In Seoul, Dongdaemun Design Plaza is the most insistent and arguably the most distinguished demonstration of the genre, albeit by Zaha Hadid, an Iraqi-British architect.

The people on the street (some streets) reinforce the Korean Wave myth. The architectural culture can do so only incidentally. There is, however, a different dimension to this culture that is certainly “Korean”—Seoul is preeminently the city of architectural “pop,” to be 221read not so much against the force of the Korean Wave as its linked movement of K-pop.

K-pop

K-pop (Korean popular music) is commonly referred to in Korean as inky gayo (popular music) or simply as gayo (music).54 It is a musical genre comprising elements of electronic, hip-hop, pop, rock, and R&B (rhythm and blues) music originating in the early 1990s. A turning point for Korean music was the 1992 launching of the group Seo Tai-ji and Boys. Also important was the establishment of Korea’s largest talent agency, SM Entertainment.

Lee Soo-man graduated from Seoul National University in the early 1970s and pursued a career as a singer, then, in the 1990s, surveyed teenage girls on what they wanted to see in music groups. He turned music entrepreneur and founded SM Entertainment in 1989, and in 1995 the company became a public company. Lee started the boy band HOT (“High-ἀve Of Teenagers”) and girl group SES; both became successful in the late 1990s. By that time other talent agencies had also entered the market and were producing performers as fast as the public could consume them. Notable were YG Entertainment, DSP Entertainment, and JYP Entertainment (Russell 2008).

As with Korean cinema and TV, it is production values and sheer professionalism that lift K-pop above other pop movements in Asia. The talent agencies adopt a strategy of apprenticeship: solo artists, girl groups, and boy bands will be recruited, nurtured at the agencies’ expense, and prepared for the opportune moment for their release. The apprenticeship might last for two years or more as trainees hone their voices, learn choreography, shape their bodies through exercise, and study multiple languages—all the while still attending school (Kim Ji-eon 2010).

The professionalism, however, has also masked exploitation, and SM Entertainment in particular became embroiled in the attendant controversies.55 At the height of their popularity, boy band HOT came to realize that their royalties were far below industry standards. After fruitless negotiations with Lee Soo-man, three of the group’s ἀve members left the company in 2001, to the dismay of millions of teenage fans. SES disbanded a year later, in 2002, then in 2003 the very successful Shinhwa moved away from SM to new management. In 2009 the Korea Fair Trade Commission was called on to probe allegations that naïve young singers, desperate for fame, were being locked into unfair “slave contracts” that enriched their managers while the stars were left in relative penury.56 By 2009 a variety of law cases and controversies 222had overtaken SM; in 2017 they continue.57 In 2016 the Chinese Alibaba Group acquired a controlling stake in SM Entertainment.

Despite its contractual travails, SM Entertainment has subsequently thrived and diversiἀed. SM Entertainment Japan was established in 2001. Together with SM Japan, SM Entertainment then moved to establish headquarters in both Beijing and Hong Kong. Not surprisingly, SM Entertainment located its Korean headquarters in Gangnam-gu, the upmarket neighborhood of Apgujeong-dong, then moved in 2012 to Cheongdam-dong, with its American headquarters on Los Angeles’ Wilshire Boulevard. JYP Entertainment is likewise located in the area, but with its American base in New York City. Cube Entertainment is similarly in Cheongdam-dong. YG Entertainment, by contrast, declares no location (although it has headquarters in Hongdae), seeing itself instead as virtual and ubiquitous, characterized by the constant mobility of both its sponsored performances and its auditions.58 The sites for the consumption of Seoul “cool” similarly include Gangnam and Apgujeong, as well as Samcheong and, notably, Hongdae (Russell 2014, 10).59

Ma Sheng-mei sees an underlying subtext of the terror of national preservation and survival—a racial substratum and the terror of “bastardy”—in the Korean Wave and its K-pop sibling. There is “a wave of nostalgia for an essentialized tradition”; tradition lives in the fear of the symbolic “bastards” who might usurp power, perhaps through contamination of the bloodline through incest. So, in the context of foreign invasions and suffering, the hermit kingdom resembles a circle that tries to keep itself intact, impervious to outside forces. Translated into the Korean Wave’s TV dramas, this drive inward might turn into the tease of forbidden love, usually between lovers who mistake themselves for half-siblings, as in Winter Sonata. Many television dramas revolve around protagonists of lowly origin caught in the hierarchies of premodern Korea, in which the story line swings between tradition and bastardy. Even the tease of incest and bastardy, which causes pain in the Korean consciousness, Ma suggests, is not demonized as the Other. Rather, it is internalized in contrast to the Western tendency, as this duality of tradition and bastardy in the Korean Wave attracts wider Asian audiences, who ἀnd themselves ambivalently wedged between a lost tradition and a modernity of the Other (Ma Sheng-mei 2006, 132).

Park Gil-Sung (2013) offers a distinctively different critique of K-pop. While the global rise of K-pop might be attributed to the passionate support of inter-Asian audiences, its actual production, performance, and dissemination have had little to do with an Asian pop-culture system. Its dissemination has been made possible only 223through global social network services such as YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter, none of which is owned or operated by Asians—despite Korea’s place in the global e-economy and culture. Park suggests that the “manufacturing of creativity in non-Western music,” as in the case of Hallyu, involves three stages: globalization of creativity, localization of musical contents and performers, and global dissemination of musical contents through social media. The salience of the ἀrst of Park’s stages reflects a general debate on the importance of inter-Asian cultural connections and hybridizations (riding on the backs of Japanese, Chinese, or Indian popular music!) in explaining K-pop’s ascendance (reviewed, for example, in Iwabuchi 2013). It is an argument rejected by Park for its inability to account for K-pop’s simultaneous success in Japan, China, India, Europe, and the United States, something never achieved by Indian, Chinese, or Japanese pop music. Simply, it is creativity that is globalized in cultural production, not contents.60

K-pop and Gangnam style

The emblematic space of Korean modernity is Gangnam; it is also the symbolic home of K-pop in both its production and its consumption. In 2012 a quite extraordinary collision of Gangnam and K-pop threw the ambivalences of Korean urban modernity into especially high relief. Park Jaesang is a Korean musician who goes by the pseudonym Psy, for psycho. His career in the K-pop scene had been relatively undistinguished, perhaps complicated by his being a Kim Jong-un look-alike and by a stage persona as a fool and court jester (Fisher 2012). On 15 July 2012 he issued a K-pop single titled “Gangnam Style.” It featured quirky, absurdist, rap dancing, equally quirky music, and somewhat inane lyrics—mostly an endlessly repeated “Oppan Gangnam Style,” which might be freely translated as “[I am] Big Brother Gangnam Style”—oppa being an expression used by Korean women to refer to an older male friend or an older brother, while “Gangnam Style” would refer to the lavish lifestyles associated with Seoul’s Gangnam District (chapter 4).

Psy succeeded where the K-pop entertainment-industrial-complex and its superstars had failed: the clip broke into the American and wider global markets. By mid-September “Gangnam Style” had topped the iTunes Charts in thirty-one countries, including the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, and Canada. By 20 September it was recognized by Guinness World Records as the “Most ‘Liked’ Video in YouTube History.” By 25 September it had been viewed over 280 million times on YouTube; by early October it had been viewed 400 million times. On 21 December 2012 views reached one billion; 224by late 2013 views were over 1.8 billion. Then, in December 2014 viewing hit (crashed through) a digital brick wall: YouTube had been designed with a counter using a computer integer that could count to 2,147,483,647, as it was unimaginable that counting would go beyond that point. “Gangnam Style,” however, broke through, and YouTube (Google) had to be redesigned. By April 2017 the count was over 2.8 billion.

Psy would be an unlikely candidate for making such an impact. He is not the superbeautiful superstar favored in K-pop; at thirty-four he was relatively ancient for the genre and, unlike other performers, he writes his own music and choreographs his own videos. “Gangnam Style” was composed by Psy and Yoo Gun-hyung, a well-known producer in Seoul who had also previously collaborated with Psy. Yoo arranged the song, and Psy wrote the lyrics.

With its almost inept dance moves, seemingly meaningless lyrics, and ridiculous settings and imagery, the clip is extremely funny—albeit, in the ἀrst few seconds, it might seem so for all the wrong reasons. Yet its core is satire, as it parodies popular imaginings of the high-class, consumption-focused, swinging lifestyles of Gangnam; both Gangnam’s self-important, ostentatious denizens and its envious wannabes are lampooned. Satire, however, is unusual in K-pop, which is mostly dominated by “teen” or “bubblegum” pop; hence, vacuous bubblegum pop is also lampooned—Psy’s dream girl is played by Kim Hyun-a, at twenty a grand old lady of teen K-pop.61 The video has Psy appearing in unexpected places in the Gangnam District, although, it should be noted, only two of the scenes are actually ἀlmed in Gangnam, while the others are ἀlmed in various places in Gyeonggi Province and in Incheon—most notably New Songdo. So, Psy appears in hedonistic relaxation on a fancy beach, which is revealed to be a children’s playground sandbox; he visits a sauna not with bigtime businessmen but with mobsters; he dances not in a nightclub but on a bus full of middle-aged tourists; he ἀrst meets his love interest (Hyun-a) in the subway; he struts with two models not down a red carpet but in a parking garage, trash and snow flying at them.

Max Fisher (2012) cites Adrian Hong’s reaction to “Gangnam Style” and its ironic take on conspicuous consumption: important to the video’s subtext, claims Hong, is South Korea’s credit card debt rate. In 2010 the average household carried credit card debt of 155 percent of their disposable income (the US average just prior to the subprime crisis was 138 percent); in Korea there are nearly ἀve credit cards for every adult. Gangnam is home to some of Korea’s biggest brands (Samsung, for instance) as well as US$84 billion of its wealth or 7 percent of the entire country’s GDP. Quoting Hong, “The neighborhood 225in Gangnam is not just a nice town or nice neighborhood. The kids that he’s talking about are not Silicon Valley self-made millionaires. They’re overwhelmingly trust-fund babies and princelings” (Fisher 2012). Fisher also quotes blogger Jea Kim: the video is “a satire about Gangnam itself but also it’s about how people outside Gangnam pursue their dream to be one of those Gangnam residents without even realizing what it really means.” However, Kim opines, that feeling is changing, and “Gangnam Style” captures people’s ambivalence—the uncertainties and insecurities of the age.

So “Gangnam Style” can also be seen as a critique of the place of fashion in Seoul society and of the mechanism whereby the pressure of envious, aspiring outsiders pushes the privileged insiders to new plateaus of fashion. To quote Fernand Braudel (1992, 324), “I have always thought that fashion resulted to a large extent from the desire of the privileged to distinguish themselves, whatever the cost, from the masses that followed; to set up a barrier…. Pressure from followers and imitators obviously made the pace quicken. And if this was the case, it was because prosperity granted privileges to a certain number of nouveau riches and pushed them to the fore.” Thus, indeed, Korea.

The immense popularity of what is really very sharp satire can be attributed in part to the video’s lack of aggression and its humorous edge; also in part to Psy’s ordinariness of persona. Overwhelmingly, however, it is the jerky rhythm and the dance moves. The song’s ubiquity has triggered numerous flash mobs in many countries, as well as a turn to “Psy-inspired clothing.” In Bangkok, a clash between rival flash mobs led to massive gunἀre. As the video was not copyrighted, it was inevitable that it would spawn imitations, restylings, and parodies (albeit of a parody), the earliest appearing on 23 July, only eight days after the original’s release.62 Many of these were surprising, and some offensive—“Jewish Style” in Israel, for instance. There was also “Gangnam Style Hitler.”63

The North Korean government released their own homage to “Gangnam Style” with their “I’m Yusin Style!,” a nonhumorous parody of presidential candidate Park Geun-hye, mocking her as a devoted admirer of the Yusin system of her father, Park Chung-hee.64 While the DPRK elite might express fear and loathing of the South and attempt to block its cultural impact, they clearly pay some attention to K-pop. Although “Gangnam Style” went viral in mid-August 2012, and despite Psy’s unfortunate resemblance to Kim Jong-un and, more distantly, his father, it took more than a month for a “Kim Jong Style” parody to surface.65 Here Psy dances, sings, and shakes his ἀnger, and his people do his bidding; there are lines such as “The national pastime of the people is to be oppressed” and “work, work, work, then sleep … torture.” 226

Innovate or imitate: K-pop and Samsung

The ambivalence that Ma Sheng-mei sees highlighted by the Korean Wave, and more speciἀcally K-pop, referred to above, raises the question of sources; it also reprises the story of Samsung, from chapter 3. “To South Koreans, the legal battles the two giants [Samsung and Apple] are waging across continents have highlighted both the biggest strength and worst weakness of Samsung in particular and of their economy in general” (Choe Sang-hun 2012). A California court had imposed damages of US$1.05 billion on Samsung for violating Apple’s patents for the iPhone and iPad. Choe Sang-hun quoted James Song of KDB Daewoo Securities to the effect that the ruling labels Samsung a “copycat” but also reflects on the brilliance of Samsung’s move—companies such as Nokia, Motorola, and Blackberry, which did not do as Samsung did, drastically lost market shares.

Where Apple is seen as the great innovator and the world’s number one company by value, pro tempore, Samsung presents as the brilliant strategist, albeit largely an imitator, and the largest technology company by sales. Samsung is seen as the quintessential, representative Korean icon. So Choe also quotes Anthony Michell (2010) on Samsung: “Koreans do things quicker than almost anyone. This allows them to change models, go from design to production faster than anyone at the present time.” (It is an alacrity also mirrored in the architecture of the city.) The strategy has been to build something similar to another company’s product but make it better, faster, and at lower cost; it would pounce, flooding the market with a wide range of models that would be constantly upgraded with incremental improvements that rivals could not match. In effect, the strategy was the innovation.

The story of Samsung and Apple raises the broader issue of innovation versus imitation in Korea’s modern cultural history. The reconstructed palaces are simulacra, Hallyu is periodically accused of building on Japanese and American popular culture (with the Japanese, in turn, also mimicking America), and K-pop looks back to American “bubblegum pop” of the 1960s and 1970s.66 However, cultures—including industrial cultures—are never isolated; the question is how ideas, irrespective of lineage, transform as they pass through different cultures, markets, and traditions. Modern minimalist architecture passes through the prism of Seoul back-street, boxland visual cacophony to yield the display of Paju Book City or a few of the more assured elements of Hongdae; K-pop passes through the mind of Psy to be displayed in the conἀdence and originality of “Gangnam Style,” transforming K-pop into something seemingly extraordinary and indigenous. 227

K-pop and architecture

The sorts of traits running through K-pop can also be read analogously in the architecture of the city. Seoul might well be read as the city of “pop” architecture—an over-the-top architecture of signage, emblems, logos, and kitsch, albeit montaged onto the blank space of the ubiquitous boxlands, ever-changing with the changes of fashion and products. At a somewhat superἀcial level this manifests in places like Seoul’s Lotte World, although this is no more than a children’s theme park in the style of Disneyland; the earlier Songdo Resort is also in this undistinguished category. More important is the more indigenous, even vernacular evolution of a wild and distinctive visual, architectural culture. Indeed we are concerned here with nothing less than the evolution of a new vernacular; it is for the most part a story of the power of graphic design (and in sharp contrast with the ubiquitous presence of “Hello Kitty”—Japanese rather then Korean—and all its standardized marketing in Seoul space).

There is, of course, another Seoul vernacular scarcely surviving in the spaces of the city and best represented in historic enclaves such as Bukchon, Seongbuk-dong, and, more intermittently, in areas such as Insadong. Traditional houses, or hanok, discussed previously, are built of earth, stone, and wood, with curved black-tile roofs, mostly dating from the city’s densiἀcation of the early twentieth century.67 However, that bland housing from the 1960s and its constant elaboration in the present time is no less a vernacular and no less worthy of reflective observation.

The hard times and their austere urban fabric of the 1960s are now, in much of inner Seoul, swept away in the rush of later development or else cloaked in the skills of the graphic designer (Insadong as its paradigmatic, transforming manifestation, as in ἀgures 4.4 and 4.5; also Itaewon in ἀgure 4.13, and Hongdae in ἀgure 4.15). However, these grinding, mean times are clearly represented in later districts, most typically along the Korail commuter Line 1 to Incheon (chapter 4); Bupyeong may be later, but it is clearly still in a world of “hard times” (see ἀgure 4.23). This is typical Seoul boxland, adorned for the most part with standardized graphics and advertising logos, signage, and similar devices. At an even meaner level are the small establishments on “the wrong side of the expressway” in Chamwon-dong (Gangnam) (see ἀgure 4.16).