This chapter is concerned with how present Seoul is experienced. Cities are not experienced as wholes, unless from space, perhaps fleetingly from the air, more comprehensively from a map. Rather, they are experienced as disaggregated places, always already fragmented, bits, moments, feelings, memories. A city is a collage, a collection, an assemblage.1

Whereas chapters 2 and 3 have focused on the social construction of Seoul and on the ideologies that have permeated that process, the present chapter seeks to understand the uses made of the city and how it is to be read—how the observer is to make sense of what is seen. Reading is concerned with images (what is seen) and with what those images might be revealing or else masking (ideas, meanings, ideologies—that is, with making sense).

The chapter is in four very unequal parts. The ἀrst is a brief discussion of how images and ideas intersect in urban space. It will introduce notions of dialectical image, montage as a technique, and collage as a result of that technique. Part 2 will occupy a greater part of the chapter and will view Seoul as a multiplicity of fragmented places, each distinct visually, functionally, and in its activities—something of a collage, a patchwork. All cities, to some extent, can be seen as fragmented into differentiated neighborhoods, each with its unique complexity of history, buildings and places, vibrancy, activities, and pathologies; in Seoul this fragmentation is augmented by the city’s geography—the city is an aggregation of seemingly separate “towns,” in the interstices between multiple dominating mountains and mostly in the lowlands of streams winding their way through those ranges of mountains. 132It is a constantly disorienting city, made even more so by the metro subway lines that can take the traveler from one place where special mountains and landmark buildings are reassuringly visible, only then to deposit the traveler in another place—perhaps only two or three stations away—where there seem to be different mountains and the previous landmarks are hidden. Part 3 will therefore see the city as transits—as lines rather than places.

The city will therefore be walked through (also ridden through) as a collection of places and their experience—“grabs” from the spaces of an inconceivably vast city, randomly and without connecting narrative. While this might give an impression of how the city is seen and experienced and of how one might seek to make sense of its component spaces, there is still the question of what sort of city these elements assemble to form. Therefore part 4 of the chapter—also brief, like part 1—will move from the idea of collage to that of an assemblage. The idea of Seoul as assemblage will subsequently be taken further (in chapter 5) to ask a more demanding question: what sort of city is Seoul becoming?

Part 1

DIALECTICAL IMAGE, MONTAGE, COLLAGE

Urban space transmits messages—street signs, the name of a building, directions to other places. There is a second though more ambiguity-laden order of such communication, in the ways that buildings and places suggest their uses—this is a house, this an office block, school, park, apartment block, factory, highway, laneway. The ambiguity can arise from dissembling (this only looks like a holiday resort; it is actually a prison) or because uses have changed over time (old offices become loft housing, a house becomes an office or a clinic). Then there is a third communicative order: this may look like a house (it may be a house) but it was once the residence of a famous writer or the site of a gruesome murder; this entertainment zone hides a military encampment; these advertising boards screen informal or illegal enterprises behind them.

This third order of communication requires information other than that directly transmitted by the appearance of the building or place—the second order. That may come from a reading of its history, a plaque, or less directly from incongruous juxtapositions, a whispered story. Thus we come to that city of blank boxes encountered in the 133“impressions” of the preface that launched the present text and whose production was a topic of chapter 3 above. The blandness of Korean everyday space is ultimately misleading: while the erasures of history, the violent division of modern Korea, the compromises and accommodations of dictatorship, and the headlong rush of the “tiger economy” may all have underlain the production of the present city, the dilemmas and contradictions can be obscured in the blandness and the visual cacophony. At that third communicative order, there is thus some imperative to attempt a reading—to determine what might lie behind the phenomena of the present city.

The chapter accordingly turns from the grander spaces of the city (the palaces, gateways, axes of chapter 2, and the stories of their resurrection in chapter 3) to how one is to read the boxlike structures, the regimented order alternating with jumbled disorder of labyrinthine space, discordant images and signs, in the seemingly undistinguished, proliferating spaces of everyday Seoul. The method will be to present the city as a collage, a vast aggregation lacking the ordering of any author but where the aggregated components set up tensions, ambiguities, and contradiction that constantly call meanings into question.

“City as collage” could apply to most cities. Seoul presents as a patchwork of distinctive communities in rather unique ways, not least due to its topography, whereby its intervening mountains fragment it into seemingly separate towns, which are then reinforced by a high level of functional specialization (Oh Myung and Larson 2011, 1). Patterns of ethnic fragmentation are also unique: though South Korea is classiἀed as a nonimmigration society, Seoul has been described as “a global city with ethnic villages” (Kim Eun Mee and Kang 2007, 64).2

Dialectical images, dialectical juxtapositions

Charles Baudelaire (1821–1867) famously redeἀned the phenomenal world: “All the visible universe is nothing but a shop of images and signs” (quoted in Benjamin 1982, 313). In the never-completed Passagen-Werk (Arcades Project), Walter Benjamin worked in the 1930s on ways of seeing—reading—the historical space of the streets and passages (arcades) of Paris in the nineteenth century.3 The method was to be a juxtaposition of “dialectical images” (“I have nothing to say, only to show”), a vast collection of visual images, aphorisms, textgrabs, and ideas from a seeming inἀnity of sources, assembled into an elaborate ἀling system of some thirty-six “Konvoluts,” or folders. This material, it seems, was eventually to be brought together as six provisional chapter divisions that would juxtapose a historical ἀgure with 134a historical phenomenon. So there were to be “Fourier or the Arcades” (the too-early, anticipatory images of modern architecture), “Daguerre or the Dioramas” (the too-early anticipations of photography, ἀlm, and television), “Grandville or the World Expositions” (the too-early precursors of the commodity’s slippage to pure image), “Louis-Philippe or the Interior” (the dust of the bourgeois era obscuring the traces of its own origins, even of revolution), “Baudelaire or the Streets of Paris” (the preἀgurement of the loss of meaning—the desert of modernity), and “Haussman or the Barricades” (the dialectical tension between obliterating the past and actualizing its potential) (Benjamin 1978; Buck-Morss 1991, 51–53; King 1996, 186). The juxtapositions would “deconstruct”—demolish the myths and delusions—of each taken-forgranted phenomenon of the Paris of that time (as of the 1930s Paris of Benjamin’s own time).

Benjamin’s approach is savagely political. Space will be viewed as multivoiced cacophony, layered images, a “complicated tissue of events,” to be deconstructed by the juxtapositions of images, both visual and textual, that are set up to refer to it. One might translate Benjamin’s method from Paris to Seoul—“Park Chung-hee and the Jungang-cheong” (the Japanese reembrace, the chaebol, and the tiger economy), “Kim Swoo Geun and the National Assembly” (unmasking the imagining of the future city), “Paik Nam June and Television” (anticipating the Korean Wave and the city’s modern translation to virtual reality, to be considered in chapter 5) … and perhaps others. More revealing, however, is to take the Benjamin method more directly to the scenes of the present city, to observe the too-frequently incoherent, perplexing juxtapositions and to ask: what contradictions in the society and culture itself might these contradictions in the city’s imagery bring to reflection? What memories might be stirred?

Any application of the Benjamin approach in the case of Seoul needs caution. Because memories in Korea are contested, thereby fragmenting its historiography (the theme of chapter 1), an image (memory) from the past that is set against an observation of the present may lead to multiple, opposed unmaskings. The screaming Christian proselytizer in the subway carriage may be purposively ignored, but, if reflected upon, remembered antecedents and lineage will likely rush back to older ideological confrontations (chapter 2). The glance at a colonial ediἀce will summon conflicted histories and their distortions in memory; reflection on the regimented rows of apartment towers will be set against the reality of surviving old Seoul, the memory of “what good times have been lost” or of “what bad times we have left behind.” Dialectical imagery is not predictable, but it does enrich the imagination and thereby the urge to creativity (chapter 5). 135

Benjamin’s method can be illustrated through his assertion of progress as fetish. If the city seems ancient, it is because of the rapidity of technological change—innovation, new commodities, new ways of producing and marketing them, new forms of consumption. A second reading reveals that all of these “changes” are but shifts on the surface of the unchanging fetishization of change itself—“hellish repetition” (Buck-Morss 1991, 108). It is the city as a phantasmagoria, a world where fashion is the “measure of time”—Seoul, indeed, in the present age presents as the epitome of highest fashion—for, as Susan Buck-Morss writes, “fashions are the medicament that is to compensate for the fateful effects of forgetting, on a collective scale” (Buck-Morss 1991, 97–98). A near century of compelled forgetting in the case of Korea—though deἀant memory always survives—leaves that only-ever-partial vacuum that can enable the fabulous outbursts of fashion that make for the new world of Korea—a story for the next chapter. “Monotony is nourished by the new,” says Benjamin, to which Buck-Morss adds, “Hellishly repetitive time—eternal waiting punctuated by a “discontinuous” sequence of “interruptions”—constitute the particularly modern form of boredom” (1991, 104). Seoul, it seems, is newness itself.

Benjamin would pose two images of the space of the city: its “organic, naturalistic” growth unmasked as delusion, on the one hand, and modernity and its progress unmasked as Hell, on the other. Both, it seems, present as images of Seoul; both also, suggests Buck-Morss, “criticize a mythical assumption as to the nature of history … that rapid change is historical progress; the other is the conclusion that the modern is no progress” (Buck-Morss 1991, 108). These two conceptions of time and history are complementary; they are inescapable oppositions whose critique, we are told, must be directed to yield the “dialectical conception of historical time.” Each image of the city, as “natural” history (evolution, the organically growing city) and as “mythic” history (the wonderful progress of the human race), is to erode the other. Only through space is time to be understood (King 1996, 192).

While this is only one part of the Benjamin critique, it is a useful one for present purposes. For Seoul, “natural” history is ambiguous—“nature” (ecological evolution) is still there, intact though possibly ignored; the idea of the “natural,” organic evolution of the city and its life, however, is interrupted, destroyed, erased. “Mythic” history, by contrast, is intact and resplendent, progress is everywhere, fashion reigns; Benjamin’s “progress as Hell,” surely, could well be Seoul.

This, of course, is all grand scale and grand hyperbole. Ordinary lives go on in the ordinary spaces of an immense city. While Benjamin’s critique (and Buck-Morss’ critique of Benjamin) suggests a method 136for reading the spaces and signs of the city, how does this translate into a reading of the city of the everyday? The method of this chapter is to tour the spaces of the city, to observe the inconsistencies of a metropolis mostly of blank surfaces and undistinguished boxes, albeit then variously identiἀed by numbers (on otherwise identical housing towers) or festooned in advertising boards—dialectical images and dialectical juxtapositions.

Part 2

SEOUL AS COLLAGE

This traverse of the city begins with “old” Seoul, still its symbolic center, then a sample of its distinctive neighborhoods, on to Gangnam as a new form of city, then, in part 3, a subway transit through the city—another dimension of its experiencing—to diverse attempts to “jumpstart” an even newer, seemingly artiἀcial form of city. Places are selected for their political and ideological context or for their ability to throw light on the city’s production, its underlying ideas, and their afterlife. Touristic Seoul is avoided unless, like the palaces, its sites illuminate that afterlife of the Chosun/Japanese collision or, like Gangnam, they are central to understanding the modern city’s trajectory.4

Jongno: Front street, back street

The long, straight, east-west avenue of Jongno (Street of the Bell) is an appropriate place to begin a reading of Seoul space. It connects the north-south axis of Taepyeongno (Sejongno) to the ancient city’s eastern Dongdaemun Gate and, as observed in chapter 2, was the street of shops that served the royal court in the Chosun era; its commercial and cultural preeminence persisted into the colonial period and in part to the present (ἀgure 4.1). It also divided the town: north were the royal and aristocratic quarters in the Chosun age, south the plebeian; the order reversed in the Japanese era. At its intersection with Taepyeongno stands the Bigak Pavilion, built in 1902 to celebrate Emperor Gwangmu (erstwhile King Kojong), as well as the Bosingak Belfry, originally constructed in 1396 but destroyed and replaced many times. Its bell, which signiἀed the time of day and also warned of disaster, gave the street its name. Also on Jongno is Tapgol Park and the Jongmyo Royal Shrine (chapter 2). 137

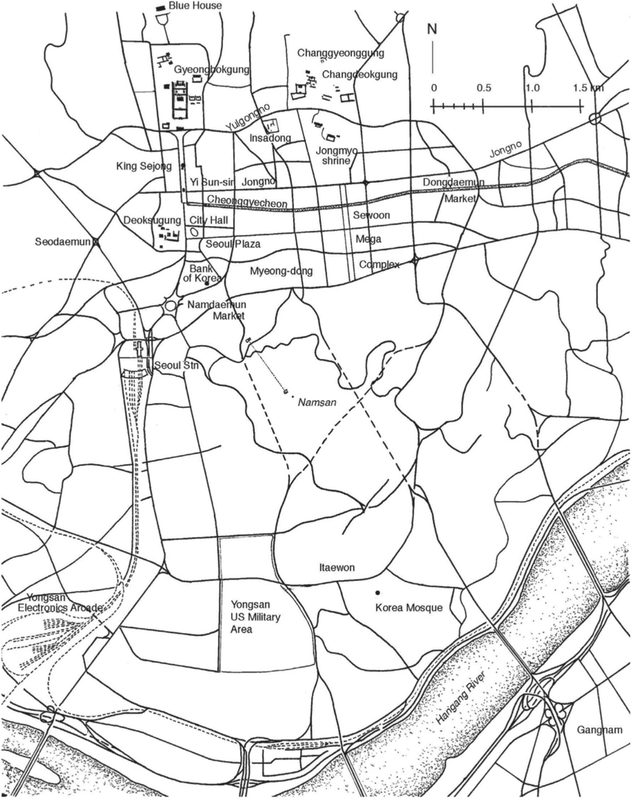

FIGURE 4.1 Old Seoul in the present era: the ancient Chosun City, Namsan Mountain, Yongsan (and Itaewon), and the Hangang River. Source: author, based on 2014 maps.

138Tapgol (Pagoda) Park was once the site of Wongaksa Buddhist Temple, founded in 1465. It was laid out by Irish advisor John McLeavy Brown on the orders of King Kojong in 1897 as Seoul’s ἀrst “public” garden, for the enjoyment of the aristocracy.5 It was subsequently opened to a wider public in 1913, in the Japanese era. Tapgol Park was the starting point of the Samil, the March First Movement, 1919; here the Korean Proclamation of Independence was read.6 As an emblematic place in Korean history, it is a popular locale for demonstration and protest. It was the terminal point for the Grand Peace March for Democracy on 24 June 1986 that led to President Chun Doo-hwan caving in to the demand for free elections.

While Jongno’s economic centrality has in part been lost to other centers, most notably Yeouido and Teheranno (Gangnam), and in part to the general dispersal of economic activity across the greater metropolis, it still retains both economic and commercial signiἀcance and will commonly be referred to as Seoul’s “main street” (Korean Institute of Architects 2000, 73). Many of Korea’s largest bookshops are concentrated here; Dansungsa, the oldest cinema theater in Korea (established 1907), and a number of other important cinemas are on Jongno; office towers, shops, and restaurants line it; the ideosyncratic Jongno (Samsung) Tower, designed by Uruguayan but US-based architect Rafael Viñoly and completed in 1999, is symbolic of Jongno’s continuing economic role;7 it is on the site of the old, iconic Hwasin Department Store.8 At the more informal end of the economic spectrum and at its eastern geographic end, there is the vast Dongdaemun Market and garment district.

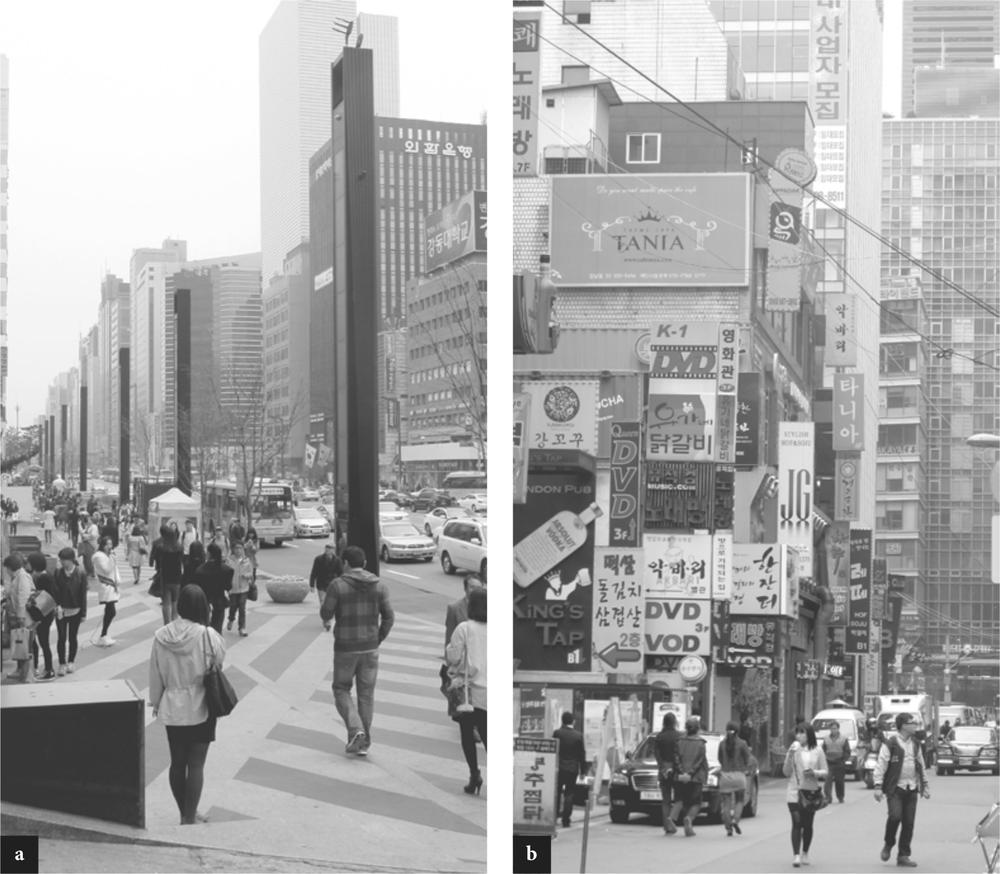

The most revealing aspect of Jongno’s spatial economy, and indeed of Seoul’s more widely, emerges from a short stroll from the wide and emblematic Jongno into its parallel back streets. Jongno is some eight to ten traffic lanes wide, then add to that the generous sidewalks on either side. The “thickness” of the wall of fashionable blocks fronting the avenue varies—around its intersection with Tonhwamunno, for example, it is seventeen meters thick on the north side and twenty-nine meters on the south. Then, behind this decidedly imposing corporate and formal façade are the narrow back streets: that on the north side is generally six meters wide, that on the south, varying from only three to six meters. The Jongno back streets—bars, eateries, entertainment, small shops, services—present an urban landscape and economy surviving from an earlier era, though still thriving, serving the towers and corporations of the “front” street in what will be claimed, following, is an emerging urban vernacular. Front street and back street are to be seen as diametrically opposed urban worlds, yet they are clearly interdependent both economically and culturally. 139

There is yet another Jongno space, in sharpest contrast with both front and back street. Seoul’s winter climate is very cold, and in some measure curtails street life; accordingly, much day-to-day commercial activity will go underground, to the subterranean shopping arcades that are mostly linked to various subway train stations. These range from the formal and organized arcades to groups of the more informal and opportunistic entrepreneurs selling assorted and often secondhand clothing, electronics, secondhand books, stationery, groceries, and assorted bric-a-brac. The Jongno underground arcade is especially extensive, regimented, and linked into the more corporate underground bookshops in the basements of larger buildings (ἀgure 4.2).

Ultimately Jongno is to be seen as old, tired, passed-by. Life—for it is still there, and vibrant—is mostly in the narrow back streets. This world of dichotomous urban realms—front street vis-à-vis back street and then underground arcade, chaebol-corporate vis-à-vis the very small entrepreneur, the formal vis-à-vis the informal—characterizes the space of Seoul.9 It is the point of the present chapter and, I argue, will dominate any reading of the space of Seoul; it is also the point expressed in the dichotomous urban realms represented in ἀgure 1.1 of chapter 1.

Back street, boxland, box space

Back streets, behind the office towers of most districts, occasionally hidden behind the marshaled ranks of residential towers, with their fragmented space of small, boxlike buildings ranging from two to four or ἀve stories, will be found in all but the newest and most antiseptic of districts. At the scale of everyday life, this boxland of Jongno, as elsewhere, increasingly becomes “box space” in modern Seoul. The “karaoke box,” of mostly Japanese derivation and common in Japan and Hong Kong, more often called KTV in Taiwan and China and videoke in the Philippines, is norae bang in Korea—literally, “song box.”10 However, in Korea these are alleged to have emerged more from the games parlors than from the karaoke bars, often initially as small booths in corners of video-games rooms.11 They ἀrst appeared in Busan (Pusan) at the beginning of 1990, as shops and technology came together to provide places where people could sing together accompanied by controllable music, up to the scale of a full orchestra. A typical establishment will have ten to twenty (or more) boxes as well as a main “karaoke bar” area in front; they might often sell refreshments, but many will not provide “beverages” and so are deemed suitable for families and children.

The norae bang went through a ἀrst crisis in 1992, and a second in 1994. Song Do-Young (1998, 100) writes, “Those crises were the result of not only cultural dynamics but also … of technological development, of market & industrial environments, of control and regulations, and … of differentiated daily life of residents.” The keys to their success, Song suggests, were new technology, the separation of singing from drinking, and cheap slot machines operable even by children. In 2012 they could still be reported as the general way to enjoy Korean popular music (K-pop).12 140

FIGURE 4.2 The complementary spaces of Jongno, 2012: (a) Jongno itself and the Samsung Tower (architect Rafael Viñoly), (b) back street, (c) underground arcade.

141There are other bang (boxes) in the modern Korean space: there are PC bangs (Internet cafés) as LAN gaming centers;13 DVD bangs or video bangs are establishments that have private rooms for couples and friends to watch movies—they began to appear in the 1980s, the motivation being mostly the seeking of privacy in a society in which Koreans lived at home until marriage and there was a social stigma surrounding public displays of affection. These rooms could often transform into something less subtle in terms of what might transpire there. There is also the soju bang, a pub,14 and manwhabang, where Koreans can go to read manwha, the Korean form of comics and print cartoons. The term manwha is a cognate of the Chinese manhua, as is the Japanese “manga.”15 There are also jjimjil bang, large public bathhouses, usually gender-segregated but with unisex areas on other floors; they are a popular weekend getaway for Korean families to relax, soak, lounge, and sleep while the children play away on PCs. As Song summarizes their role, “[The] urbanized environment of Korea has been terribly lacking in time and space for cultural activities. That’s the effect of rapid growth oriented processes over the past 40 years … pro-collective cultures which did not provide enough individual free expression” (Song Do-Young 1998, 123).

The bangs are literally boxes. Floor space is typically divided into the smallest cubicles that can still be used for their intended purpose; bangs might occupy a single floor or multiple floors in a building. Their roles relate to the typical crowding of Korean domestic space in a period of changing values placed on privacy and escape. They especially boomed after the 1997 crisis, as the government helped create the conditions for establishing small businesses. Kang Inkyu (2014) sees the bang as signifying the metamorphosis of Korean culture to a new, ever-emerging state of fragmenting cybercultures.

The bangs of Jongno back streets are mostly above small shops or food outlets, and mostly labeled “PC” or “DVD.”

Insadong: Labyrinth

Insadonggil can be seen, in one sense, as a back street to Jongno but taken to an extreme (and without the bangs). In the early Chosun era, 142there were two towns whose names ended in “In” and “Sa,” divided by a stream that ran along what is now Insadong’s main street, Insadonggil. Its diagonal irregularity in an otherwise Zhouist (though partly Japanese-imposed) grid reflects old ecological processes and signiἀes an antiquity preceding the present city with its modernist imposed order. It became the area of subsidiary palaces, of which only the restored Unhyeongung Palace survives,16 and a residential area for government officials in the Chosun era; it also housed Dohwaseo, the government-based royal painting institute of the dynasty. During the Japanese era, the wealthy Korean residents were forced to move and sell their possessions, whereupon Insadong became the locale for the trading of such antiques. In the Japanese era it was part of the “northern village” and a realm of Korean decay and poverty (Henry 2014, 9, 52–53). After the Korean War, the area became a center of the city’s artistic and café life, evolving as a popular destination for foreign visitors during the 1960s and even more so during the 1988 Olympics. In the late 1990s there was a program of renovations and modernization, to further attract the tourists. This, however, provoked protests due to the consequent loss of its “historic character,” leading to a halt in the officially endorsed renovations.

The promotional rhetoric on Insadonggil will commonly refer to it as a “traditional street for both locals and foreigners,” the “culture of the past and the present,” “unique,” and representing “the cultural history of the nation” (Ch’oe Chun-sik et al. 2005). While it was once known as the biggest center for antiques and contemporary art trading in Korea, much of that activity has now relocated to areas near the newer “cultural hot spot” of Samcheong-dong north of Insadong, or to the luxury shopping locale of Cheongdam-dong in Gangnam, south Seoul. Accordingly, it is now commonly referred to as merely a “tourist spot” (Moon So-young 2009). Still, about one hundred art galleries are claimed to be clustered in the area as it reinvents itself, albeit now more as a tourist area. A consequence of the tourist focus is higher turnover of establishments and, increasingly, outlets for less expensive works by younger and “rising” artists. “Young people who felt that the threshold for art galleries was very high now feel free to enter our gallery after seeing small paintings through the show window,” said Han Jin-sook, a curator at Gallery Topohaus. “Paintings are popular, especially as wedding gifts” (Moon So-young 2009). Gallery Topohaus’ show window was in the form of a giant red heart surrounded by silver stars. The small-scale, almost grassroots rise of this new, decentralized production and marketing soon attracted the corporate sector, however: across the street from Gallery Topohaus arose Ssamziegil, a complex of small art galleries and handicraft shops opened in late 1432004 by Ssamzie, a company manufacturing accessories and trading artwork.17 Certainly Ssamziegil has helped Insadong to attract young people—as artists, as voyeurs, and as purchasers and thereby collectors. Yet, noted one manager, “[a]bout 70 to 80 percent [of customers here] are Japanese tourists” (Moon So-young 2009). Where Hongdae, to be discussed below, might be seen as a domain for cultural production (though more as a site where the putative cultural producers would “hang out”), Insadong is where they might seek to market their production.

Change—though in Benjamin’s terms it is no change, just the delusion that the eternal present is always change—will continue to produce both the fantasy of culture and the consumer paradise. It will also reassure the young artist to continue in the delusion that their genius is real and recognized, until the reality of the commodity world slowly dawns. Fashion, the fetishization of novelty, seizes Insadonggil; the consequent inflated rents expel the creative and the champions of “alternative lifestyles”—to Hongdae, Samcheon-dong, and elsewhere. There may indeed be “no change,” but there is certainly constant relocation, of which Insadonggil, like Jongno, is emblematic.

The reality of Insadong is that it is a collection of 1960s and 1970s small two- and three-story, boxlike buildings that have now been gentriἀed, often rebuilt, adapted, and commodiἀed—it is heavy urban design applied to an indigenous muddle. The northern end is the fashionable, tourist stretch of the better-presented galleries and narrow radiating alleys with pseudo-ancient teahouses and fashionable shops (ἀgures 4.3, 4.4, and 4.5). It goes downmarket as it goes south, toward Jongno, marketing Korean crafts, antiques, food, and music, to a more local clientele, hosting performers of indigenous music, religious practices, and local foods. The labyrinthine intricacy of ancient Seoul is retained as is the minute scale of its alleys, no doubt for its marketability; however, it is also part of a wider project of riding on the reconstructed memory of the Chosun age. Comparison of the area’s present structure (ἀgure 4.3) with the 1928 map of Insadong in Todd Henry (2014, 53), citing Keijo toshi keikaku chosasho (1928), reveals that only limited “improvements” have occurred since then. Tapgol Park has been enlarged and the southern end of Insadonggil reordered; however, the most signiἀcant change has been connecting previous culs-de-sac to provide east-west accessibility through the “village.”

While the tiny establishments in Jongno’s back streets are for the most part just boxes adorned with their advertising boards and other signage, on Insadonggil and in its alleys these are more often minimalist, understated, and self-consciously “modern.” It is Seoul boxland taken to its limit. 144

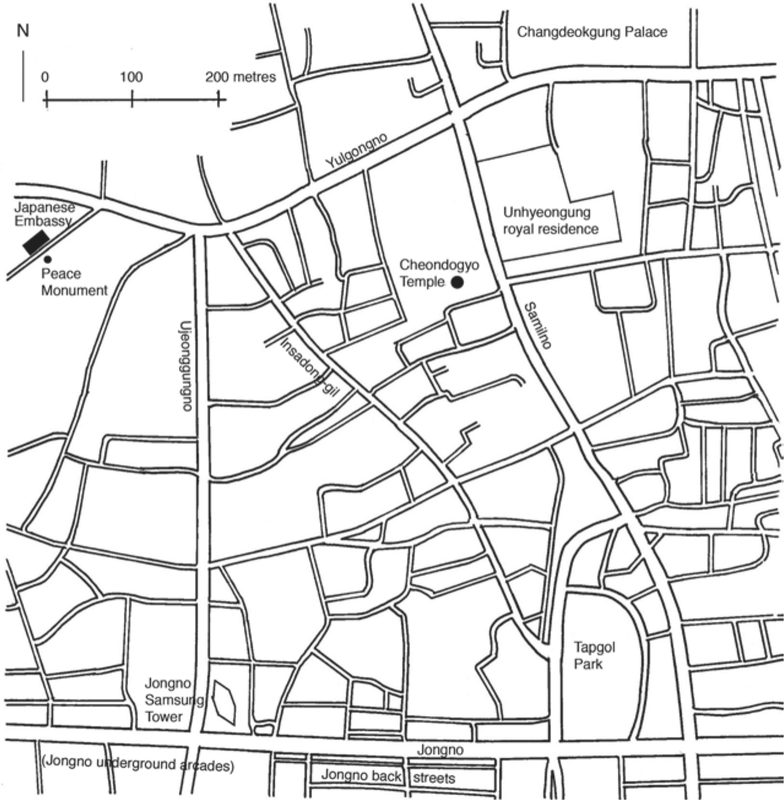

FIGURE 4.3 Insadong as labyrinth. While the colonial Japanese “modernized” the principal roads of the old city, the interiors of the blocks retained their premodern, Chosun, labyrinthine complexity. Source: author, based on 2014 maps.

FIGURE 4.4 Insadonggil, 2012: urban elegance and minimalist design.145

FIGURE 4.5 Insadonggil boxspace, 2012: high elegance transforms Seoul boxland.

Namdaemun and Myeong-dong

South of Jongno and east of the ancient Namdaemun Gate, in the erstwhile plebeian district of precolonial Seoul and the upmarket commercial locale of Japanese Seoul, is Myeong-dong, recently Seoul’s most “high-end” retailing district, though increasingly replaced in that role by Apgujeong-dong in Gangnam-gu, south of the river—this latter has Apgujeong Rodeo Street, homage to Beverley Hills. Then, between the gate and Myeong-dong is its obverse in the vast Namdaemun Market. The two zones, Namdaemun Market and Myeong-dong, constitute another labyrinthine district of narrow alleys that reflects its unplanned, unregulated, underclass genealogy (ἀgure 4.6).

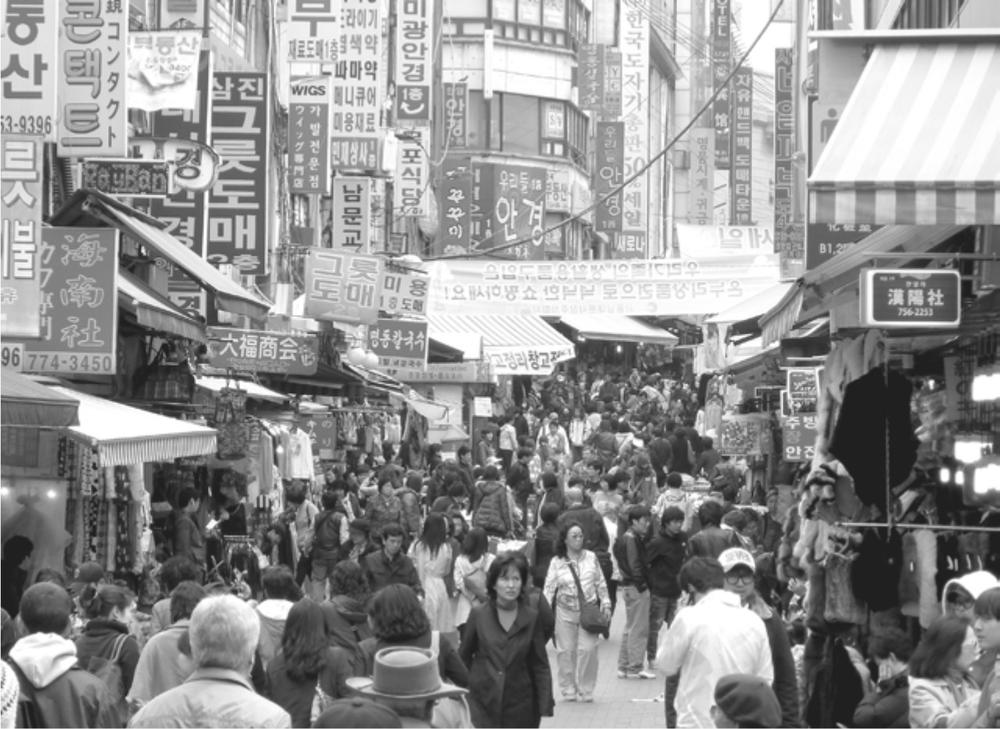

Namdaemun Market’s history goes back to the beginning of the Chosun dynasty, when merchants established their businesses nearby, just outside the city wall. The present market dates from 1922 and is one of Seoul’s two largest markets, the other being Dongdaemun Market at the eastern end of Jongno.18 It comprises some ten thousand shops of all sizes, especially for clothing, agricultural products and other foodstuffs, everyday needs, and medical supplies. Namdaemun’s commercial space is layered: its alleys are deἀned by formal buildings, many of them high-rises, with their ground-floor space used as shops and occasionally food outlets; there will be stairs to other levels; in front of the shops and often as extensions to them will be a layer of stalls, typically under retractable awnings, beneath which clothes and other wares typically hang from hooks and wires; in front of those again, though more often freestanding at intersections of the labyrinth, will be smaller, mobile stalls, often under multicolored umbrellas; a ἀnal layer are the food vendors operating from metal dishes on the ground. 146There is all manner of merchandising; missing, however, are the vendors of pirated DVDs who characterize the street markets of Southeast Asian cities—the Internet and the DVD bangs have mostly replaced them (ἀgure 4.7).

FIGURE 4.6 Namdaemun Market as disordered space, 2012.

FIGURE 4.7 Namdaemun Market as diverse, intersecting economies, 2012.

The chaos and disorder of the street surface is matched vertically on the façades of the enclosing buildings. Projecting from the 147buildings are layer upon layer of advertising boards for products, establishments, and services in a visual cacophony that would defy any disentanglement of messages. It is an adornment of façades that is repeated across the districts of the city.

Myeong-dong in the Chosun dynasty had been a residential area. In 1898 the Gothic-styled Catholic Cathedral was completed there (chapter 2) and, in the colonial period, the area became the Japanese colonists’ primary commercial district. Much of its ἀne colonial architecture was destroyed in the Korean War. After rebuilding in the late 1950s, the area acquired the National Theater, bookshops, and teahouses, to become a center of Seoul’s artistic life. In 1962 the junta generals put dampers on Seoul’s raucous nightlife, at that time centered on Myeong-dong, in part to save electricity (Cumings 2005, 356). With the subsequent relocation of the National Theater, however, both art life and nightlife declined, and instead Myeong-dong began to acquire high-end shopping, thence to become Seoul’s focus for high fashion.

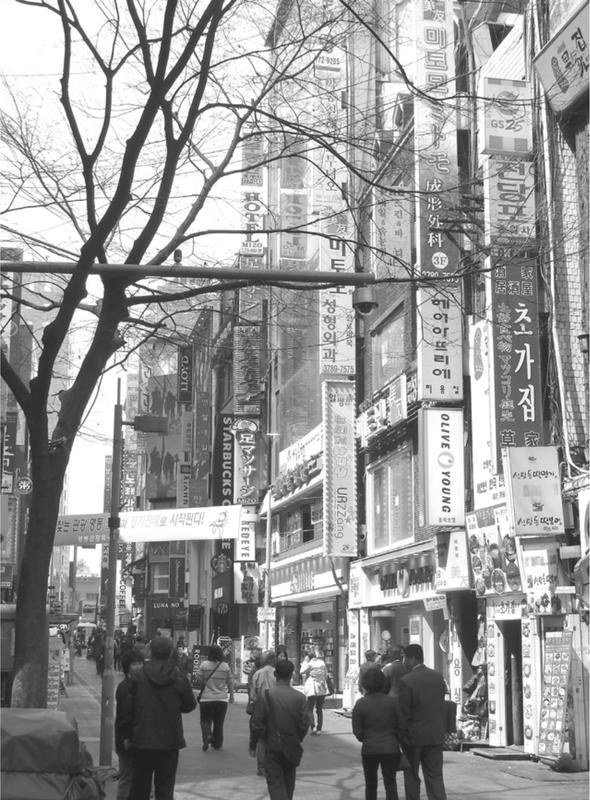

Like Namdaemun Market, the adjoining Myeong-dong is a labyrinth and also displays the festoons of advertising boards projecting from building façades; however, they are better designed and more often associated with national and global names, and the more fragmented, smaller-scale buildings are interspersed with the department stores, office towers, and surviving colonial-era buildings—the Bank of Korea Building, for example (ἀgure 4.8).

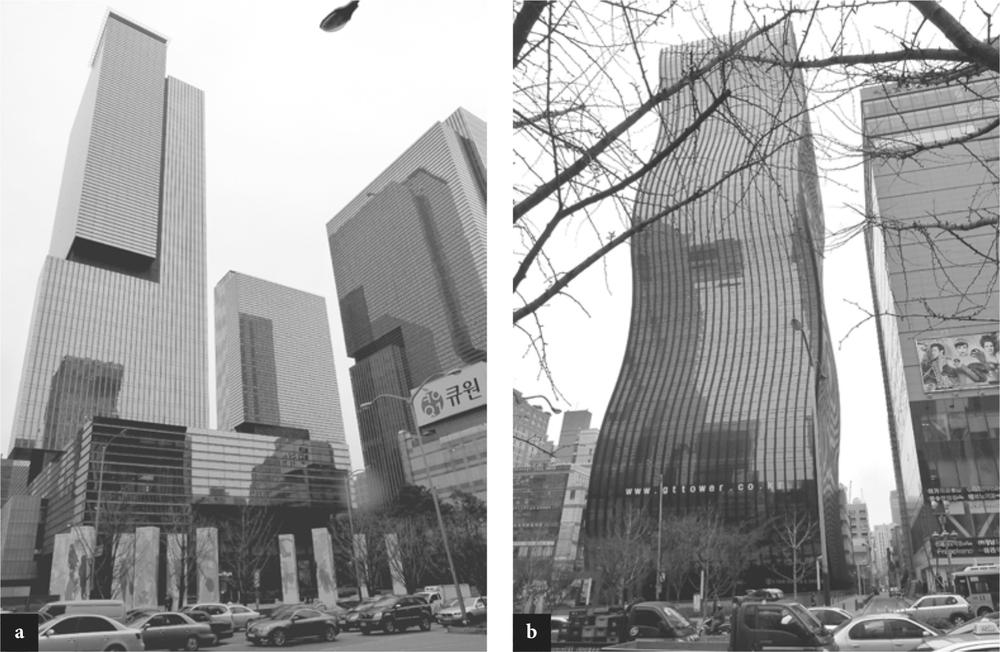

As corporations and, less often, state institutions seek “presence” with iconic buildings, these also come to distinguish the often dispersed districts in which they locate. The overdesigned Jongno (Samsung) Tower performs this function on present Jongno. Several towers distinguish Myeong-dong—the “split” Post Office Tower is one, the “bent” SK Tower is another.19

Cheonggyecheon

Unlike Myeong-dong or the immediate back streets of Jongno, Insadonggil presents as a display of purposive urban design. Although it follows an ancient streamline, there is no attempt to acknowledge that past in the design or signiἀcation of the space. The stream is missing. A far more interventionist and comprehensively designed project to transform the boxland of the city center is Cheonggyecheon, a 5.8-kilometer creek in downtown Seoul. Here also was an ancient stream, named Gaecheon (Open Stream), albeit artiἀcial, constructed as part of a drainage system in the early Chosun era, thence to be regularly drained and refurbished throughout various reigns. It was renamed Cheonggyecheon in the Japanese colonial period and was 148remembered from that era by composer Kang Sukhi (2007), cited earlier; he recalled it running parallel to the city’s commercial Jongno, with women washing clothes in the stream, its life seemingly little changed from the old dynasty. It was also totally polluted, according to newspaper reports of the time (Henry 2014, 158–159). After the 1950–1953 Korean War, rural-to-urban migration turned Seoul into a slum city, and the banks of Cheonggyecheon acquired squatter settlements in flimsy makeshift houses. A twenty-year program of slum demolition and concrete covering of the old watercourse was crowned, in the 1967–1971 period, with the elevated, sixteen-meter-wide Samil highway over the top of it for its 5.8 kilometers. Together with the emblematic Samil Building, it served as a proudly displayed example of economic growth and urban modernization (Park Kil-Dong n.d., 10).20

FIGURE 4.8 Myeong-dong, 2012. Like Namdaemun Market, Myeong-dong is labyrinthine but also upmarket; the indigenous muddle is interspersed with grand department stores and with monuments from the late Chosun and Japanese eras.

149In July 2003, Seoul’s then mayor (and subsequent president) Lee Myung-bak resolved to remove the elevated Samil highway and restore the stream as part of a wider movement to reintroduce nature into what had become a “hard” urban concretescape. The project, with its underlying rhetoric and somewhat brutal manner of implementation, must be seen in the context of Lee’s political ambitions and self-reconstruction. In Cheonggyecheon Flows to the Future (Lee Myung-bak 2005), published by Lee to coincide with the stream’s (re)opening, we are told how he “endured developmentalism” (Park Chung-hee?) represented in the paved stream, how he had escaped from developmentalism, remaking himself as the man of “the future” to show the path to reembrace the nature of common people.

Accordingly there was rhetoric to promote a more eco-friendly urban design and, at the same time, to advance urban competitiveness with rival East Asian cities through ampliἀed urban infrastructure (Lee Myung-bak 2006). Cheonggyecheon merchants demonstrated against the project in 2003, however, echoing antirestoration discourse raised by NGOs;21 there were also protests and debate on the need for alternatives to high-rises and against unsystematic development, traf-ἀc problems, and the displacement of merchants.22 The process was also widely criticized as being procedurally undemocratic and rushed, as the desires of the Seoul metropolitan government took precedence over all else (Cho Myungrae 2004; Ryu Jeh-hong 2004, 23).23 The project continued, however, with the ἀnal cost of some 386 billion won (around US$281 million), and the stream ἀnally opened to the public in September 2005.

While the attempted character of the restoration might be labeled “naturalistic,” it is quite artiἀcial. The stream had long run dry, and so the design called for 120,000 tons of water to be pumped in daily (Park Kil-Dong n.d., 13). Environmentalists, however, had previously called in vain for the restoration of the original upper reaches of the stream in order to use available and natural water flow in the watercourse.

The corridor’s beginning, at the great north-south axis of Taepyeongno (Sejongno), is dramatically and elegantly signiἀed in the immense Spring sculpture by Swedish American sculptor Claes Oldenburg; it plays on the notion of “spring”—rebirth, source of water, but also spring as a mechanism. It uses a conch shell as its generating springlike form, with a stone pseudo-rivulet running across the plaza to the artiἀcial waterfall (“spring”) that feeds the reconstructed stream 150(ἀgure 4.9). It is surely accidental that the sharply conical form of the sculpture also reflects the ubiquitous conical “spires” with illuminated red crosses atop all manner of shop blocks and other, small, boxlike buildings that house small churches throughout the Seoul region (and to be discussed further, below).

FIGURE 4.9 Cheonggyecheon: (a) Spring (sculptor Claes Oldenburg); (b) Spring and pond.

As completed, the restored stream begins at a fountain pool in the ἀnancial-government-royal district of Sejongno, below the stone rivulet that connects it to the symbolic Spring, then flows eastward along its old concreted channel; the rapids, rock pools, wetland swamps and marshes, ecological displays, walking paths, and climbing areas are simply additions, sitting atop the concrete channel that still lies beneath its surface (Stevens 2009). In the water, however, there are still some stones from the much older stream and its retaining banks, as well as traces of the vanished highway. On the high walls retaining the roads above on both sides, there are images and stories of past history; most dramatically, there is a vast tiled mural over several hundred meters long depicting the grand procession of King Sejong to Suwon. The stream changes along its length—stony and sculptural, then softened by limited planting, then more “naturalistic.” The whole project is urban sculpture on a vast scale, in part as a vehicle for historical storytelling—reinvented memory, erasing the erasures of the past (ἀgure 4.10). 151

FIGURE 4.10 Cheonggyechon as it passes through the Jongno financial district, 2012; right, the mural of King Sejong’s procession to Suwon.

Both the economy and the architecture change along the length of the stream: corporate and “high-end” as it traverses the ἀnancial district near its beginning, then the less imposing boxland of smaller, mostly older buildings. Then, in its lower, eastern reaches, it enters the vast Dongdaemun Market area. This part of the present city is mostly from the 1960s and 1970s, built at a time when the stream was still extant, although the present market can be traced to Chosun era enactments of 1791 (Lee Ki-baik 1984, 230). Here, for around a kilometer, the stream is lined on both sides by long, standardized building rows from the 1970s, ἀve to six stories to the north and ἀve stories to the south, uncompromisingly modernist in style, dilapidated, seemingly underoccupied—almost abandoned—and now used as part of an extensive garment district. The more decrepit north side is a busy street market of continuous small stalls—a shoe zone, a pet-shop zone, and so on. It links to the extensive Dongdaemun Market district (ἀgure 4.11). The southern side opposite the traditional Dongdaemun Market is the also linked Pyonghwa Market. Chun T’ae-il was a worker in one of the several hundred textile sweatshops there in the 1970s; he died on 13 November 1970 at the age of twenty-two when he set himself on ἀre to protest the failure of a petition for a Labor Standards Law—his slogan: “Workers too are human beings.” On 30 September 2005, two days before the opening of the rehabilitated stream, a statue of Chun was unveiled at the Boduldari Bridge over the Cheonggyecheon in front of Pyonghwa Market (Kal Hong 2011, 118). Whereas these lines of buildings previously faced an elevated highway, they now face 152a very popular stream and its walkways. There are already signs of the gentriἀcation that might be expected to follow the restoration of the stream: in 2012 the JW Marriott Hotel was constructed immediately facing Dongdaemun Gate. Also at the bridge across the stream at that point, platforms were under construction in April 2012 for a pop concert—a regular event—a younger generation being attracted into an old, albeit tired place, though briefly. More was to come.

FIGURE 4.11 Cheonggyecheon looking toward Dongdaemun Market and the garment district, 2012: identical five- and six-story blocks on both sides.

In March 2014 the immense Dongdaemun Design Plaza was opened on the south side of Cheonggyecheon as the new centerpiece of the city’s “fashion hub,” designed by Iraqi-British architect Zaha Hadid and Korean studio Samoo, with its curving, elongated forms, and tautologically proclaimed as “neofuturistic” and “the world’s largest asymmetrical free-formed building” (Ashin 2014). It also marks the corporate sector’s spectacular takeover of what had been a district of informal, small-scale, and even chaotic invention and entrepreneurial vigor (Hwang Jin-Tae 2014), as well as a powerful response to the “Bilbao effect”—the shock of architect Frank Gehry’s Bilbao 153Guggenheim Museum of 1997—one for the ages, and a locale for the equally extraordinary exhibition in 2001 of the video art of Korean/universalist Paik Nam June, a topic for chapter 5. Also one for the ages.

In a critique of the effects of the Cheonggyecheon project, Ryu Jeh-hong (2004) has described three areas that it traverses, each locally renowned for small-scale, highly networked metal and molding industries, referring to “networks and processes of high-tech production based on multi-kind items and small quantities that colluded to constitute the system.” The discussion leads to an interesting question that implies a broader critique of modern Korea’s evolution: “This metalworking network producing multi-kind items and small quantities resembles a postmodern, or at least late modern, production system. How is it possible to form a postmodern system of production out of a pre-modern way of applying technology within a modernized space?” (24–25). The suggested answer is that, in the shambles of 1945, there were no means of production left behind in Japanese factories or flowing from American military bases except machinery parts. In the struggle for survival, small workshops arose to utilize this refuse in what was in effect a “premodern,” informal, and folk subsistence economy and industry. When the Park-led shift to import-substituting manufacturing began, a premodern mode of industrial organization simply morphed into part of a postmodern, “flexible accumulation” mode in the sense argued by David Harvey—the collapse of the “consensus” of big corporations and big labor (the chaebol?) and its replacement with more “flexible” ways of organizing the creation and appropriation of wealth (Harvey 1989). In Harvey’s understanding, vertical integration is broken down, processes are split up, their components are dispersed, and self-employed consultants and outworkers replace in-house experts. All this fluidity is, however, highly organized; there are strong coordinators in the form of the ἀnancial markets, and the key investment and management decisions are more centralized than ever before (King 1996, 116).

Ryu tells of the Sewoon Arcade area of Cheonggyecheon, discussed earlier in relation to architect Kim Swoo Geun. This has evolved into a network of technological know-how in computers, enabled by a diversiἀed folk industry of deconstructing and reconstructing imported electronics, in a virtual explosion of innovation that would not be possible in a grand, mainline corporation. The disintegrated apparel industry in the Dongdaemun Market area of Cheonggyecheon has likewise increased the speed of imitation, design development, manufacturing, and marketing.

It is suggested that there were here two signal failures of the Seoul metropolitan government. The ἀrst was the failure to recognize both 154the vitality of the chaotic economies of the Cheonggyecheon corridor, ultimately built on the desperation of a post-1945 slum community. The second was to charge bulldozer-like into a world whose role, vitality, or vulnerability they saw ἀt to ignore. Yet it is likely that the national prosperity (the chaebol, the Five-Year Plans) ultimately rides on that world’s flexibility, innovation, inventiveness, and transgressions. It represents another of the deἀning space types of Seoul.

Cheonggyecheon continues to evoke controversy. While one of its claimed effects has been to reduce the separation between the north and south of the old city, there was criticism that this would be achieved via intended gentriἀcation of adjacent areas that house many shops and small businesses and, of course, those incubators of creativity suggested above. An emphasis on a hoped-for network of activities to be named the Cheonggyecheon Cultural Belt only deepened the sense of misgiving.24 Then, in the face of the restoration of two ancient bridges over the stream in the name of a return to old culture—in effect simulacra in the sense argued by Baudrillard (chapter 1) and also represented in the re-created Gyeongbokgung Palace—there were attacks on the project’s frequently articulated claims of a return to authenticity.

The criticism of Cheonggyecheon on the grounds of its inauthenticity is problematic: certainly there is no replication of wild nature nor of the “soft,” ἀne-scale, intimate, designed nature of the traditional Chosun-era garden. Cheonggyecheon may, however, be seen as an urban-scale translation of older cultural practices of representing human responses to ecological reality—in this case to the ecology of an urban drain in a city district starved of green space. The adverse reactions might therefore be seen more as nostalgic yearning for speciἀc, lost aspects of the culture—for the garden as a place of withdrawal and scholarly contemplation. The places of withdrawal in modern Korea are boxes rather than gardens and rarely for scholarly contemplation, as observed in relation to the bangs (unless, of course, the Internet is the new site of scholarly contemplation in a cyberage).

The question of authenticity is problematic in present Seoul, especially in light of the attempts to reconstruct the Chosun world and to obliterate that of the Japanese colonial age.

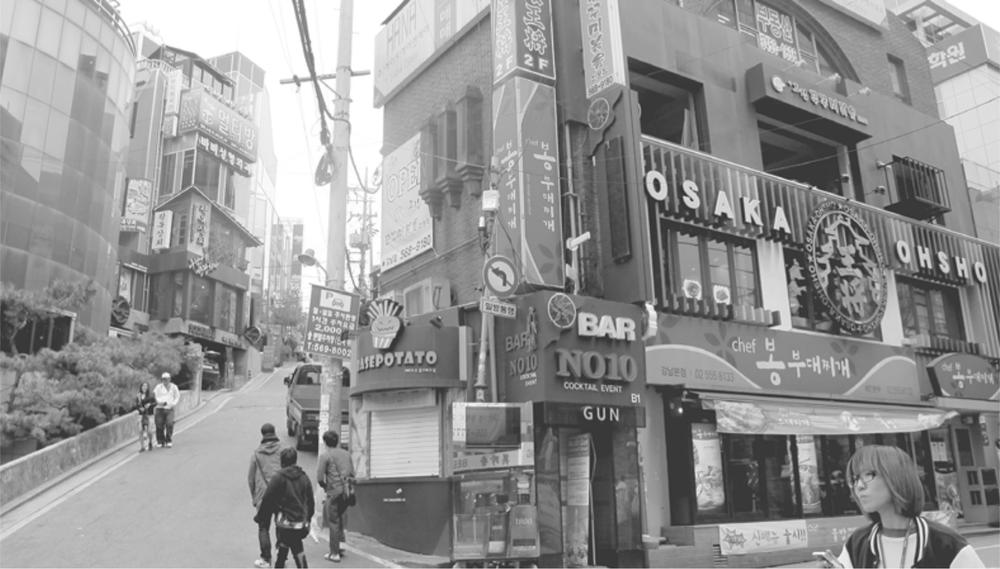

Dongdaemun and hybrid economy

The long Cheonggyecheon blocks and their adjoining Dongdaemun Market highlight the juxtapositions of Seoul space and their anomalies. There is Ryu Jeh-hong’s (2004, 14) reference to the hybridity of Dongdaemun, drawing on Jan Nederveen Pieterse (1997), who in turn 155references Fredric Jameson and Ernst Bloch: “The uneven moment of social development, or ‘the coexistence of realities from different moments of history’ (Jameson 1994, 307) is no longer embarrassing: Pyeonghwa clothing stores in front of Migliore fashion centre in Dongdaemun [since 2014, in front of Cheonggyecheon Design Plaza], mom-and-pop stores alongside convenience stores, European restaurants next to Korean folk taverns, and traditional tea rooms next to coffee houses. This hybrid coexistence of different pasts is called ‘the synchronism of the non-synchronous,’ or the ‘contemporaneity of the non-contemporaneous’ (Bloch 1997).” Nederveen Pieterse (1997, 50) has drawn attention to the hybridizing effect of globalization (hybridization being a constant theme of the present account): “What globalization means in structural terms … is the increase in the available modes of organization: transnational, international, macro-regional, national, micro-regional, local.” It is an effect that translates into modes of production: “The notion of articulation of modes of production may be viewed as a principle of hybridisation…. Counterposed to the idea of the dual economy split in traditional/modern and feudal/capitalist sectors, the articulation argument holds that what has been taking place is an interpenetration of modes of production” (50–51). The sheer speed of Korean development has precluded any neat transformation of one mode or era of production into another. Instead, we end up, in the urban landscape of Seoul, with radically disjunctive modes of economic organization coexisting, both reinforcing and undermining each other simultaneously—seemingly more so here than elsewhere.

Seoul’s public markets in particular illustrate both the traditional/modern split and the “principle of hybridization” that brings these together. In Korea the public market does not appropriate a public square or a designated building; rather, it will occupy a street or group of streets, restricting or even ending vehicular movement. The markets are permanent, giving circulation space back to pedestrians and thereby, in a city of small and often-crowded apartments, providing a public space and local community focus—albeit also crowded (Gelézeau 1997, 77). The markets and the blank-walled laneways that they most typically appropriate are cultural survivals of ancient Hanyang; they also signify Korea as being linked to a Chinese spatial realm of communal lanes and walled, secluded houses. The markets thrive even in the newest areas of the metropolis; streets are seized in the absence of lanes and where the housing is high-rise apartment blocks. Yet the markets are now also of the twenty-ἀrst century; the more traditional stalls and their vendors interweave with outlets of the more formal (and “modern”) economy. 156

Korea is distinguished by the sheer speed of its modernization, ergo of its globalization; when everything spins ever faster, there is no time for evolution and little time for reflection. The consequence is the sort of hybridization suggested by Nederveen Pieterse, in which the chaebol coexists with the wild disorder of the traditional market, Samsung with the proliferating stalls of Dongdaemun or Namdaemun, and the fragmented production of Cheonggyecheon with the global corporations lining Gangnam’s Teheranno—indeed the coexistence of realities from radically different moments of history (Jameson 1994, albeit referring to Japan rather than Korea). The hybridization makes Korean space “different,” enabling a larger-sized underground economy in Korea than in other OECD countries,25 but thereby problematizing efforts to measure the “national” economy in the same way as others. Itaewon, Hongdae, and Insadonggil, but also both the grand and more minuscule markets, are manifestations of this intermingling of economies, of nationalistic exclusiveness but with global embrace, of order with disorder. An even more dramatic manifestation of proliferation and disorder, however, is represented in that forest of red plastic crosses that electrify the night skyline of Seoul.

In this context of ahistorical hybridization and coexistence of realities, Ryu Jeh-hong (2004) refers to the story of Seoul Plaza, another mayoral project of Lee Myung-bak. An open area is bounded on the west by the grand north-south axis of Taepyeongno, the Korean-traditional Deoksugung Palace, the Romanesque-Revival Anglican Cathedral, and the former National Assembly Building; on the north by the Japanese Art Deco City Hall; on the south by the American-Modernist Plaza Hotel. The modern history of Seoul seems to have been assembled here; it had also been a historic site of protest, notably for the 1919 anti-Japanese uprising and June 1987 democracy movement. In the early 2000s, a forty-year-old fountain was demolished, and the plaza’s previous dominant role as a traffic intersection was ended and instead it was reopened in May 2004, grassed and with diverse art installations, ostensibly as a public open space and for “cultural displays.” Ten days after the opening the public was forbidden to walk in the plaza, however: “Don’t Walk, Just Look” was the instruction written next to the roped-off ἀeld—landscaping is only to provide spectacle (Ryu Jeh-hong 2004, 11). It has subsequently become a new location for anti-American protests—the (hybridizing, anticolonial, neocolonial) story of Korea still playing out there (Kim Rahn 2008).

The hybridization and coexisting realities continue. In 2012 the old City Hall had been screened and hidden (for restoration). It would be overwhelmed by a very large, overdesigned, idiosyncratic 157new building. The old Japanese building is to be effectively embedded in—embraced by—the new, plastic-form, high-tech City Hall (Yoo Kerl, architect).

Boxlands 1: Itaewon

The spaces listed above are all within the old walled area of the Chosun city and evoke memories of that space and age. Itaewon, on the southern slopes of Namsan (South) Mountain, began its modern history later, as a residential area of the Japanese colonists in the early twentieth century. The Japanese departed in 1945, and the city was destroyed in the early 1950s. The city of the 1960s and 1970s rush was hurriedly, poorly built; it was also a city of transgressive insertions, none arguably more blatant than the American military area of Yongsan to the immediate south of the old walled city, which, in 1945, had simply and smoothly been taken over from the departing Japanese. Nearby but in the dreary, disordered boxland of the city itself it spawned Itaewon—“entertainment” places, bars, brothels, American music, and disorder. In the Cold War it could be seen as “the only alien space within Korea” (Kim Eun-shil 2004, 60); it was also a focus for resentment against the occupiers and their indigenous clients (the dictatorship). In more recent times it is seen more as one hybridized, ambiguously signed space among many. Itaewon can be observed in the context of Lee Jin-kyung’s (2010) analysis of South Korean military labor in the Vietnam War, domestic female sex workers, Korean prostitution for US troops, and Asian migrant labor in Korea. Her argument, to reprise from chapter 1, is that the Korean “economic miracle” is to be demystiἀed, to be seen at one level as a global and regional articulation of industrial, military, and sexual proletarianization, and, at another, as the transformation from a US neocolony to a “sub-empire.” The “miracle” stood on a masking of the changing status of both Itaewon and Korea more broadly. The lesson of Itaewon is that it reveals the mask as just that—merely a mask, of advertising boards, surface glitter, and consumption. In a study of kijich’on (military camptown) prostitutes, Moon Hyung-Sun (1997, 1) comments that, since the Korean War, over one million Korean women have served as sex providers for the US military.26

In more recent times Itaewon has transformed into Seoul’s center for international cuisine and cosmopolitan entertainment; it is still mostly visited by American military personnel stationed in the nearby Yongsan Garrison.27 The main street, Itaewonno, runs for some 1.4 kilometers eastward from Itaewon Junction; off this branches a network of alleyways and arcades crammed with stores, restaurants, 158nightclubs, and bars. One of these alleys leads up to “Hooker Hill,” resplendent with nightclubs and establishments of lesser repute and a favored haven for much of the military population of the nearby Yongsan US military base. Paradoxically, the prostitution market is in part Russian-supplied.28 From the late 1990s on, Itaewon also gathered a moderately visible gay and lesbian community.

FIGURE 4.12 Itaewon space, 2012: Hannam-dong and cascading buildings appear as if constructed on top of each other. As Seoul is a landscape of mountainsides, it is also a landscape of seemingly precarious cascades.

Itaewon is “ordinary space”—undistinguished boxlike buildings with advertising boards and neon signs. It is atypical in that the smallscale boxland is on the main road as well as on the lanes and back streets, although, even here, there are the “signature” corporate towers—most notably the elegantly designed Cheil Worldwide.29 Whereas the back streets to Jongno (and of Teheranno, to be discussed below) are mutually deἀning, dialectic opposites of the front avenue, those of Itaewon are exaggerations—in some sense caricatures—of the main Itaewonno Road. The back street to the north has most of the ἀnest and most fashionable bars and restaurants; that to the south is the notorious Hooker Hill. The back street behind the small bars and other establishments of Hooker Hill—a back-back street—is Muslim: the Seoul Central Mosque is here, discretely embedded behind a long building that has, among other things, PC bangs and Islamic coffee shops. The Seoul Central Mosque opened in 1976 and has been the target of a number of “incidents” and a consequent need for police protection. This back-back street has a proliferation of tiny enterprises: small shops, a few tailors, computer repairs, Indian halal cafés; they would be nearly the smallest to be seen in Seoul, no doubt reflecting the economically depressed status of the city’s Muslim community.

In a discussion of Itaewon’s mosque and small Muslim commercial community, Kim Eun Mee and Jean S. Kang (2007, 78–80) observe that the more numerous groups of its patrons are Indonesian and Bangladeshi. On the basis of Seoul Metropolitan Government 159data they ἀnd that both groups in the 2000s had small concentrations in the industrial southwest, mostly Geumcheon and Guro, with the Indonesians also in Seongdong and Seongbuk in the northeast. The mosque preceded the influx of the Muslim workers, and none of these localities would be seen to have much connection with Itaewon.

Itaewon possesses a visual drama in that it is built on very steep hill faces, with cascading buildings and spaces. It is quite unique in that most of its signage is in English (ἀgure 4.12).

Only its nightclubs and the ladies of Hooker Hill hint at the compromises of Korean history—the American intrusion, the earlier rescue of the capitalist “progress” in the Korean War, the Japanese occupation preceding that of the Americans. If viewed in an earlier Cold War context, the Russian ladies of the nightclubs present as a wonderful anomaly—how many secrets transmitted across the pillow? In the present age, however, their presence seems to attest to no more (nor less) than the collapse of the Russian world and of one of the great myths of history (yet to be learnt by the Koreans of the North). Itaewon is fashionland in Benjamin’s understanding, “progress as Hell,” yet it is also a screen—albeit the paradox of a revealing screen—across the national humiliation (ἀgure 4.13).

FIGURE 4.13 Itaewon space, 2012: Hannam-dong back street, an assemblage of high-end, finely designed, discordant boxes.

160Yongsan (Itaewon) provides another, very different screen across the national humiliation: here is the immense War Memorial of Korea, originally conceived by the Roh Tae Woo government as an emblem of military glory to legitimize the military dictatorship that Roh had served and as a symbol of ethnocentric nationalism. Sheila Miyoshi Jager has noted the connection forged between “the military, manliness and nationalism,” as well as the fact that the museum at the memorial virtually ignores the Japanese period—it is a blank, expunged from history (Jager 2003, 118, 129; Kal Hong 2011, 73).

Seoul is a metropolis of a multiplicity of distinctive neighborhoods, often very concentrated in what each is known for. The western side of Yongsan is sharply different from the eastern, Itaewon side; the west has the Yongsan electronics market, comprising some twenty buildings housing around ἀve thousand stores selling computers and peripherals, stereos, appliances, electronic games and software, videos, CDs, and all things electronic. Stores range from the traditional retail to the noisily, aggressively entrepreneurial. The term Yong pali, “Yongsan salesperson,” has been coined to describe ruthless, shameless sales behavior. Yongsan is thus a patchwork of concentrations—military base, Itaewon, Hooker Hill, Muslim focus, electronics mart—all effectively a reflection of Seoul itself as a multiplicity of interacting multiplicities, an assemblage, as will be argued following.

There is far more to Yongsan, however. In September 2010 plans were revealed for a new Yongsan Business Hub, to include an underground strip mall “six times larger” than anything else in the city, to house studios, galleries, and “concert stages for young artists.”30 The centrality of “young artists” in marketing everything Korean is a theme for the next chapter. There would additionally be three landmark buildings at the center of the district, a triangle of spikes allegedly inspired by an ancient crown, to be 100, 72, and 69 stories tall. The one-hundred-story “spike,” designed by architect Renzo Piano, was proudly proclaimed as the world’s most expensive building, to be built by Korea’s Samsung Corporation, which also built the Burj Khalifa (162 stories in Dubai) and Taipei 101 (101 stories, in Taipei). Another “spike” would be the Yongsan Apartment, designed by the Dutch architects MVRDV: it would comprise twin towers, sixty and ἀfty-four stories (somewhat at odds with the elsewhere-proclaimed seventy-two stories), connected by “a pixelated cloud” of apartments, swimming pool, amenities, cafés, and a serene koi pond connecting the two towers. The “cloud” would be a ten-story bridge linking the buildings at their twenty-seventh floors. The response, however, has varied from the troubled to the outraged. “The ‘pixelated clouds’ evoked the clouds of debris that erupted from the iconic 161World Trade Center towers after terrorist planes flew into them,” charged New York’s Daily News. MVRDV’s response: it “regrets deeply any connotations The Cloud project evokes regarding 9/11. It was not our intention to create an image resembling the attacks nor did we see the resemblance during the design process.”31

Yongsan Business Hub was initially proposed as a project of Korail (whose vast land holdings in Yongsan would thereby be greatly enhanced) and Samsung. The overall plan was designed by Daniel Libeskind, who, ironically, was the designer behind the rebuilding of the World Trade Center. Construction was scheduled for January 2013; however, by August 2010 the project’s demise was already being predicted (Kim Tong-hyung 2010); by March 2013 its ἀnancial collapse was clear (Rosenberg 2013); a month later the project was abandoned.

Yongsan thereby presents three worlds in confrontation. First is the world of military domination—it was the center of the Japanese military colonial enterprise from as early as 1894, which seemed to pass seamlessly in 1945 to that of the American hegemony. The second is Itaewon. It was and continues to be the realm of American happiness—here are the places of escape, the nightclubs, entertainment “spots,” and brothels, just beyond the gates of the US military realm. The third world of Yongsan is that of the global hyperspace—the electronics mart in which a new generation of Seoulites will seek the gadgetry to join a wider cyberworld. There is also a putative fourth world of Yongsan Business Hub, in which the ideas and the designers will no longer be simply “Korean” but, rather, “other,” as an assembly of more global attempts at understanding and constructing what might constitute a “Korean world and space.” There are different spaces, each standing against and contradicting the others: military space (with all its own contradictions), the hedonistic space of escape, the space of entrepreneurial vigor, and the space of capital and its regime of accumulation.

Boxlands 2: Hongdae

Another example of the ambiguity of Korean blank space is addressed in Lee Mu-Yong (2004): Hongdae, an abbreviation of Hongik Daehakgyo (Hongik University), had been just another nondescript residential area in the 1950s but, in the 1970s, it metamorphosed into an art culture district following the establishment of Hongik University and its College of Fine Arts (ἀgure 4.14).

Seoul is extraordinary in its proliferation of art districts and profusion of galleries and museums. One is tempted to identify Seoul as the Berlin of Asia; it reveals the power of destruction and erasure 162that then seemingly enables the sudden release of creativity and the dream of representing both the idea of Korea itself and that other idea of Korea’s place in a new, twenty-ἀrst-century world.32 Claes Oldenburg’s Spring at Cheonggyecheon may indeed provide a metaphor for Seoul and Korea (albeit from an American sculptor): the fantastic kinetic energy held within the spring by its suppression (1895 to 1945, to 1953, to 1987?), then the colossal drama of its sudden release (see ἀgure 4.9). One looks at Seoul as the greatest manifestation of cultural resurrection. It is the theme of chapter 5 to follow but also of any reading of chaotic, even tawdry Hongdae—a wonderful place, like much else in what is simultaneously the ultimate Orwellian, Kafkaesque city of urban-design oppression, with all those seemingly identical graywhite towers. It is the greatest contradiction.

FIGURE 4.14 The wider city. Source: author, based on 2014–2015 maps.

In the early 1990s a trendy café culture in pastiche (postmodern?) buildings inserted itself into Hongdae; it is now galleries and small theaters, art studios, handcraft furniture shops, art institutions, 163publishers, “culture spaces” and clubs, techno and trance. Many foreigners prefer Hongdae to Itaewon, given its relative lack of prostitutes and seediness.

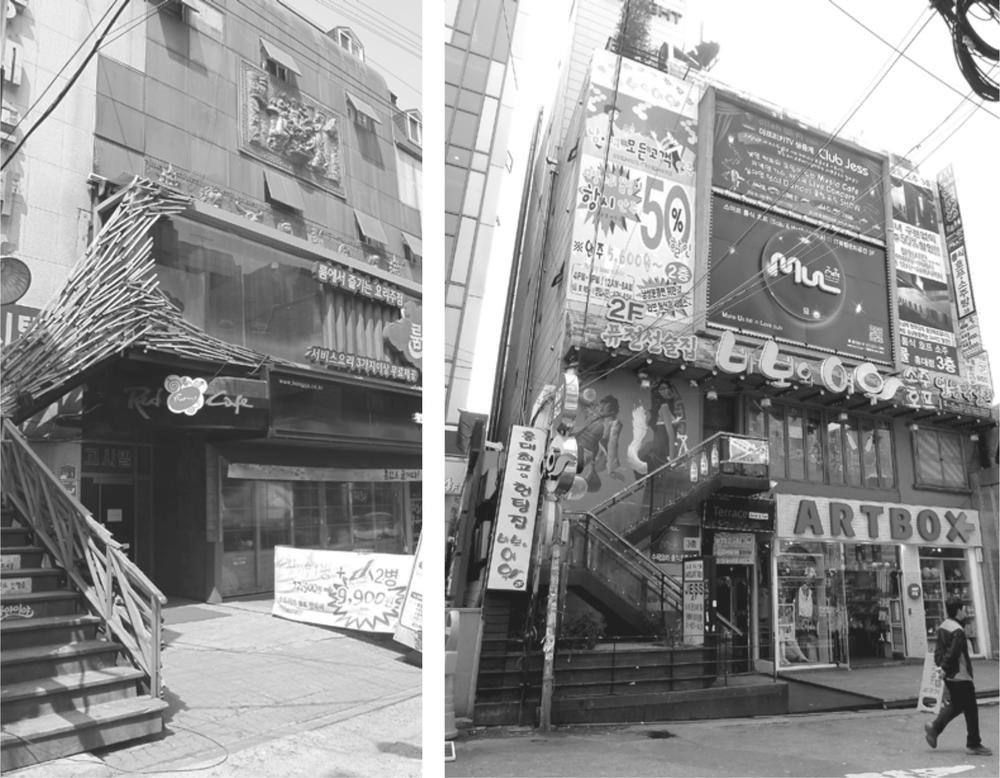

The tiny shops that proliferate in the back streets and alleys are, in their “style,” survivals from an earlier, harder age (even though many are from a more recent time). They are akin, in some sense, to the endless stalls and street markets and underground galleries. These small establishments proclaim their presence with signage, variously projecting signboards, decoration, and emblems. This, of course, is also the character of the establishments behind Jongno. The decoration in Hongdae becomes more inventive, however (this is, after all, a zone of art and performance), and there will be self-conscious design. Yet this is still to be seen as a “folk” vernacular. There are just a few instances, in Hongdae as in Insadong, where that self-conscious design will be expressed in an avant-garde architecture (ἀgure 4.15).

Hongdae is an expression of the explosion of cultural production that accompanied the collapse of the era of dictatorship, albeit exploding as if from the vacuum of obliteration (the spring is released). The power of Hongdae may be in the exuberance that becomes possible in the lack of an artistic/cultural “establishment.” Instead of a still-thriving, conservative, self-protective community of “old art,” here it is nostalgia that is to be countered by the young students and a nascent avant-garde.

FIGURE 4.15 Hongdae, 2012: in both images indigenous muddle morphs into avant-garde.

164If authenticity—truth to oneself—is the dialectical opposite of nostalgia (chapter 1), then the confrontation with nostalgia might be seen as a condition of possibility for “authentic” creativity and reinvention.

Seoul, as observed above, is resplendent with “art districts,” caught up in the shifts from freewheeling avant-gardism to commercialization and exploitation. Hongdae is only one of these “wild places” simultaneously in tension and collaboration with the ever-shifting and redeἀning art market. Yet it is still antinostalgic in its presentation (if not in the intentions of its entrepreneurs); thus it stands dramatically against the elitist, antiauthentic national enterprise of rebuilding the ancient palaces, gates, and grand monuments. It is as if in opposition to the “Chosun return,” embodied in the reappearing palaces, that one can read Hongdae.

The national enterprise and the start-up nature of Hongdae come together, somewhat incompatibly, in the Seoul Art Space program of the Seoul Foundation for Arts and Culture (SFAC), established in 2004 by the Seoul Metropolitan Government. In 2015 there were fifteen Art Spaces listed, widely distributed across the space of the city.33 The programs, facilities, and political agendas vary as widely as their locations. Thus Seoul Citizens Hall, in the basements of the new City Hall and like a symbolic rhizome under the older Japanese hall, is clearly a promotional instrument of the city government. Seoul Art Space Seogyo is an intrusion into the Hongdae area, its mission proclaimed as “the dream of being a hub of the art ecosystem in the Hongik University area”—to take it over? It exudes the discordant order of officialdom in the dishevelment of Hongdae.

Other Art Spaces would seem more creative in their intent. That at Geumcheon is proclaimed as being linked to the “urban regeneration” movement of Seoul city planning and as responding to the decline of the Guro complex (chapter 3); it was established in 2009 to provide an experimental art complex with residency programs, exhibitions, urban research projects, and an open studio—all accommodating both Korean and international artists. It occupies the buildings of an old printing factory.34 Similarly, Seoul Art Space Sindang utilizes an old and bypassed underground shopping center from 1971; forty-two previous shop units have been converted into “creativity workshops” and exhibition halls. Yeonhui’s Art Space is a small “village” for writers; Seoul Art Space Mullae has been fashioned from a strip of steel materials shops, with a theater and performance emphasis; Seongbuk 165has a focus on arts participation and health. There are also Art Spaces at Gwanak, Hongeun, Jamsil (dedicated to people with disabilities), and Namsan Arts Center (a theater), as well as Namsan Creative Center, Daehak-ro Creative Space, and Seoul Theater Center—all with an experimental theater focus.

It is instructive to see, in the mind’s eye, the disciplined program of SFAC and the Seoul Art Spaces against the undisciplined disorder of Hongdae, and even more against the informal vigor of Cheonggyecheon. And to ask: where is creativity most likely to be found?

Gangnam Chamwon-dong

Nothing could be further removed from the wild, unconstrained, exuberant disorder of Hongdae than the regimented discipline of the stiffly restrained ranks of identical apartment towers of Gangnam and a seeming inἀnity of other districts on the southern side of the Hangang River (ἀgure 4.14). As Hongdae and the other areas contemplated above are in the north, this contrast might mistakenly be seen as a north-south distinction; we will see following, however, that the immense zones of identical residential towers are ubiquitous to Seoul. However, those of Gangnam, fronting as a vast wall onto the river and determining the river’s character in its central reaches, are especially emblematic.35

One could take any of the hundreds of zones of multitowered housing for special discussion. For present purposes, a medium-sized estate in Gangnam’s Chamwon-dong will be observed (ἀgure 4.16; also seen in ἀgure 1.1 from chapter 1). It abuts the Kyeongbu Expressway (Highway 1) and comprises forty-four residential towers, each some twenty-eight stories, together with its own schools (sizes of towers in Seoul vary: those of the estate immediately to the south are thirty-ἀve stories). The soul-less, virtually identical, necessarily numbered towers have elaborate, overdesigned entrances, completely hidden car parking, a ἀnely wooded landscape weaving through the blocks, woodland trails (albeit alongside an elevated highway whose scale is further visually augmented by ten-meter-high noise barriers) with exercise equipment liberally distributed along the trails. This is clearly an upmarket housing estate—“Gangnam style.” It is also, however, the ultimate Corbusian, modernist landscape—one lives by numbers, in numbered towers in an idyllic woodland park, isolated.36

An underpass under the elevated highway leads to another, more varied urban landscape of both large and small, older apartment buildings, a very few separate houses, small shops, bars, and bangs—the necessary, complementary urban landscape that can supply what 166the vast, regimented estate is planned to exclude. It is, in effect, the housing estate’s back street; most estates, however, enjoy no such immediate back street. There is another, vaster, and far more vibrant zone of entertainment and escape little more than two kilometers to the south, in the Gangnam-Teheranno District, that serves, in various ways, much of the city.

FIGURE 4.16 (a) Housing estate, Chamwon-dong, Gangnam District … and (b) its obverse, on the opposite side of the Kyeongbu Expressway, 2012. These dichotomous worlds are within three minutes’ walk.

Boxlands 3: Teheranno

It has been suggested above that the political economy of the Cheonggyecheon Stream is to be seen in the context of a premodern, post-1945 subsistence economy of scavenging, recycling, and reinvention, morphing into a postmodern economy of disintegrated, flexible, small-scale, high-tech production and services on which the corporate economy of large-scale, globally connected activity ultimately rides. In such a view, new invention and creativity are always more likely to arise in the flexible world of Cheonggyecheon and similar zones of the old, disheveled city than in the corporate towers of the chaebol.

Cheonggyecheon’s obverse is Teheranno (Tehran Street). Samneungno was a 3.5-kilometer stretch of Highway 90, in the Gangnam-gu District on the south side of the river; in the 1960s it ran through a relatively remote and underdeveloped area that was annexed into Seoul in 1963. Its name was changed to Teheranno to mark a 1976 visit from the mayor of Tehran (a street in Tehran was, reciprocally, supposed to be renamed after Seoul). In the following 167decades Gangnam-gu experienced phenomenal growth, with Teheranno becoming one of Korea’s busiest streets, noted for the number of Internet-related companies operating there—Yahoo!, Korean rivals Daum and Naver, Samsung, Hynix, diverse Korean and international ἀnance institutions, and major banks.

Teheranno is popularly called Teheran Valley and is the Silicon Valley of Korea, though more a steel-and-glass canyon than a valley. Except for the signage in Korean script, it could be any North American city center. It is believed that more than half of Korea’s venture capital is invested there.37

There is a view that the impact of information and communication technologies (ICTs) on cities is essentially substitution, replacing the need for proximity and presence with telepresence (W. Mitchell 1999, 110).38 Nigel Thrift (1997), however, sees this as myth, arguing instead that we need always to be aware of the ways that “culture, context and content mediate the contingent social constructions of ICTs, and their resulting effects” (Graham 2004, 98).39 Some aspects of these effects will preoccupy chapter 5; other aspects are to be read from the (distanced) juxtaposition of Teheranno space and Cheonggyecheon space. Two lessons can be drawn from this relationship: the ἀrst is that neither Teheranno nor Cheonggyecheon is unique to Seoul; rather, both are different though inseparable aspects of a globally linked (hyper)-space of flexible corporate coordination and control (Teheranno) and an equally globally linked (and hyperspatial) realm of creativity and innovation (Cheonggyecheon).40 The second lesson is that there are different genealogies and time scales involved in these radically different, interlinked realms. Within the context of Seoul, the most modern of metropolises, Cheonggyecheon and the space that it presents is “ancient,” dating from the immediate post-1945 period of scraping for scrap materials and promising ideas; it evolves from pilfering, the junkyard, and local, small-scale invention. Teheranno space is new; its antecedents are the multinational corporation and the more homegrown, Japanese-modeled but ultimately indigenized chaebol, albeit often dating from colonial-collaborationist family enterprises from the Japanese era. There is a third lesson from Teheranno, relating to the fragmentation of Seoul space: that, however, will be deferred until later in this chapter.

While dialectical imagery might run through both Teherrano and Cheonggyecheon, it is their dialectical (though distanced) juxtaposition that is to be read as most clearly throwing “the miracle” into question—the Park-chaebol axis (and order) always inextricably linked with and dependent on the disordered, ultimately subversive “Miracle on the Cheonggyecheon.” 168