REWIND, REWIND, REWIND

COINCIDENCES CAN BE pretty great. On a sunny September Saturday just after moving to Toronto, I stayed in bed until 3 p.m., because I had nothing to do. I had come here for a job and, for the first time I could remember, had no work to deal with on the weekend. But I also had no one to hang out with, because I’d left most of my friends behind in New Brunswick a month earlier. Since I’d just bought a turntable, I finally convinced myself to get out of bed to go find a vinyl copy of Joel Plaskett Emergency’s Ashtray Rock. I’d spent much of my younger life believing a foolish theory that Maritimers only liked music made in the Maritimes to justify their own cultural relevance, not because the music was actually good. Ashtray Rock was the chief album that changed my mind. It wasn’t just a great rock record that I needed to add to my collection; after leaving the east coast, it had taken on a whole new life for me. It began to feel like a document of growing up on Canada’s east coast — of its brutal winters, of its summer nights spent running off to party in the woods, of its constant outflux of people. I’d listen to the mp3 version front to back as I took the bus, then the subway, to work. “The Instrumental” would begin as I got off, six stops east; I’d emerge onto Yonge Street as the lap steel kicked in and the record’s duelling protagonists got a postcard from the girl who got away — who moved away. I’d get to the office listening to “Soundtrack for the Night,” an ode to not knowing what you’ve got until it’s gone. Its story was fiction, but after the move, Ashtray Rock was among the most relatable records I’d ever heard.

So I hauled myself out of the tiny room in the apartment I rented with strangers and began my search. No shops on Bloor Street had Ashtray Rock, so I took a streetcar south to Queen West. First store, nothing. Second store, nothing. I gave up, picked up some other records, and grabbed another streetcar home.

It was standing room only. I wound up near the rear exit. As we pulled up to the next stop, a tall, familiar-looking guy hopped on.

It was Joel Plaskett.

Was it? Actually? Nah. Wait — maybe? We hit the next stop, a dozen people shuffled off, and the man walked farther back. It’s definitely him. Soon enough, we were standing next to each other.

I froze. Should I just stand here? This guy’s music was the reason I got out of bed that day. Ugh. The coincidence was too much to handle.

Well, fuck it. “Excuse me — are you Joel Plaskett?”

“Yeah, man. What’s your name?”

Of course he was this friendly. I told him my name and, unable to handle silence, started throwing him questions. Was he in town for the Polaris Music Prize gala on Monday? Yeah, actually — he’d been invited to play songs from his Ashtray Rock follow-up, 2009’s Three, which was shortlisted that year. Played anywhere cool lately? Definitely — he’d just come from a quick gig in New York, and before that he was actually in Fredericton, the city I’d left the previous month; my friends had seen him play a few days earlier. After a little more small talk, I held up my bag of records and confessed that I’d been looking for Ashtray Rock.

“Oh, sorry, man. We sold out of those on the first tour. But I might press it again someday.”

My face probably lit up. And then I realized I’d missed my stop four blocks ago. I wished him good luck at the Polaris Prize, got off the streetcar, and texted about 4,000 people.

Three didn’t win the Polaris, but that streetcar encounter made me circle back to it anyway, and I came to love it as much as I did Ashtray Rock. At first, it mostly served me as a breakup album, for both a girl and a place; the record is, after all, about leaving someone and somewhere behind. But with enough listens — and, for a while, a mended relationship — the record’s whole picture became clearer. It’s about coming home, too, and embracing what you’ve got and where you’re from. Soon I was seeing bigger pictures across Plaskett’s whole catalogue — crystal-clear portraits of life on the east coast, of growing up there, of leaving there, of coming home. The ghost of geography infects his oeuvre, from its friendly barroom tales and harbour-town stories to too-familiar ruminations over one’s place in the world. The frustrations of leaving and loss, I soon recognized, were sprinkled throughout his entire body of work. The themes popped up constantly: in Thrush Hermit songs like “I’m Sorry If Your Heart Has No More Room” and the breakup bookend “Before You Leave”; in the loved-ones-long-gone songs of the Emergency’s Truthfully, Truthfully; and in the metaphoric road trips of La De Da and Three.

Plaskett in the mid-2000s.

[© Ingram Barss]

As I explored Plaskett’s catalogue with fresh ears, the prospect of living in Toronto for the long-term was becoming more of a reality, even though I was identifying as a New Brunswicker, and a Maritimer, far more than ever before. His lyrics started to carry more bite, like in “Work Out Fine,” where he calls out friends for shipping off to Montreal and Toronto, and in “Love This Town,” where he jokes about just how easy — and fun — it can be to hold a grudge against them. Like thousands before me, I’m living out a theme that’s been an undercurrent for much of Plaskett’s work: living well, for many, means leaving home. And like any good lapsed Catholic, my internalized guilt occasionally rises up, reminding me that I’ve left the place with which I most strongly identify. I fly the flag, but it doesn’t match my mailing address. Over time, this cognitive dissonance just keeps getting wider. I’m prouder than I ever have been of where I’m from, but my roots elsewhere keep getting deeper. My love for home is complicated, but as somebody once pointed out, free and easy’s overrated.

LIKE MUCH OF Canadian art, there’s an inextricable connection between Plaskett’s work and its sense of place. He’s a great proponent of regionalism, of fostering the history and stories that make a place what it is. Atlantic Canada’s sense of place in the world is inexorably shaped by distance. The closest Canadian metropolis, Montreal, is at least a 10-hour drive for most East Coasters, and the rest of the vast, culturally unique province of Quebec sits in between. This instills a fierce sense of independence in Atlantic Canada, even though that same distance breeds an economic dependence on the rest of the country. East Coasters will tell you that there is no place in the world as great as our home, and in many ways, we are correct. It is a place steeped in history and surrounded by nature, the people are among the friendliest in the world, and the cost of living remains bafflingly low.

But boosterism rarely acknowledges broader contexts. As Canada’s major hubs developed along the St. Lawrence River and its watershed centuries ago, the Atlantic region was established, largely, as a place to pass through or pass by, onto the rest of the country. The prospect of leaving home, then, is something East Coasters have long had to grapple with. The prolific author and journalist Harry Bruce — who bucked migration trends by moving from his birthplace, Toronto, to his ancestral home of Nova Scotia — wrote in his east-coast epistle Down Home: “Maritimers, more than other Canadians, have had to keep their eyes on the horizons, and Leaving Home has long outlasted the golden age of sail as part of their heritage. It is as Down-Home as a clambake at dusk, complete with Moosehead ale.” And Gary Burrill, who edited the now-defunct New Maritimes magazine, met so many Maritimers who had moved away to Ontario, Alberta, and “the Boston States” that he compiled a whole book about their stories, arguing that leaving is an “inseparable” part of the regional identity. In one sense, this isn’t all bad: tension fuels art, and on the east coast, the theme of going away has inspired songwriters for at least 130 years. While previous generations of musicians wrote straightforward songs about nostalgia and shuttered industry, today’s pop recognizes this reality with a tongue-in-cheek flair, from Plaskett’s less-than-subtle expat chiding in “Work Out Fine” to the name of electronic producer Ryan Hemsworth’s early album Can Anything Good Come From Halifax? Beneath the jabs, though, the harsh reality remains: today, Canada’s most eastern provinces have the smallest populations in the country, while New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island have the lowest gross domestic product per capita — which is a nice way of saying they have a measurably low standard of living. People have flocked from low-density communities to big cities for centuries, but in Atlantic Canada, the numbers give them an extra push.

This context gives greater meaning to Plaskett’s success as an artist living on the east coast. It’s also why his concerts sell so well in cities like Toronto and Calgary, where east-coast diaspora head in droves. “Atlantic Canadians want to support artists from home,” his manager Sheri Jones once said, “because they will take any opportunity to be reminded of home.” Ontario and Alberta are the ostensibly greener pastures where youth, talent, and labour tend to seek work and like-minded people. Often, those like-minded people are other Maritimers, meeting through well-timed introductions and happy accidents. Harry Bruce once described Maritimers as “like a motorcycle gang,” banding together in spite of our inherent stubbornness and infighting; never do we band together more tightly than when away from home. And luckily for us, we have Plaskett’s music. He isn’t the relative at Christmas dinner nagging us to move back east. He’s a nationally beloved artist that transcended the barrier of geography to tell stories from a corner of the world that sheds more storytellers every day.

The culture of leaving that set this stage stretches back for centuries. The region has a history of displacing its own, actually, that goes further back in time than the idea of Canada itself. Since about 1500 C.E., people there have shouldered the consequences of directives issued from plush rooms in distant capitals in the names of colonialism, bottom lines, and Canadian unity. No wonder the kids don’t want to live there.

As soon as explorers like Cabot and Cartier stumbled across the region that would become Atlantic Canada, the wheels were set in motion. First, the native Mi’kmaq, Wolastoqiyik, Passamaquoddy, Beothuk, and other First Nations peoples were slowly, methodically exploited, displaced, and killed as Europeans began to arrive. The early French Acadian settlers were next. In the 1750s, nearly 11,000 of them were deported as far as Louisiana and the Falkland Islands after new British rulers demanded allegiance or exile in what’s been called le Grand Dérangement.

After generations of French and English power struggles, things settled by the mid-19th century; the region flourished with industry, thanks in large part to shipping and shipbuilding, and the population reached 800,000 by 1861. [1] But the east-coast colonies — eventually provinces — were slow to adapt to industrial changes, and people soon began to trickle away. As the world’s ships moved to steel and steam, the Atlantic provinces stuck with wood and wind, and their ports were eclipsed by more forward-thinking ones. The lack of strong rail infrastructure, too, helped choke out the region’s shipping hubs as cargo-bound vessels instead went to the U.S. or down the St. Lawrence River. By the time Confederation was enacted — originating, partly, as a band-aid effort by the Atlantic colonies to secure funding to strengthen its rail networks — the region had lost its chance to be an economic entry point to Canada. Instead, power, people, and industrial centres further concentrated along the St. Lawrence and its tentacled corridors. Maritimers started leaving home by the thousands. One historian called it an “exodus” that took on “the characteristics of a mass migration.” Another called it a “decapitation” of Maritime society. From 1851 to 1931, more than 600,000 people left the Maritimes; while there was some immigration, it was a net loss of 460,000 people. Tragedies over those decades only exacerbated the problem. The Great Fire of Saint John in 1877 burned two-fifths of the New Brunswick city to the ground, grinding to a halt any chance of the city becoming a competitive shipping hub. And in Halifax, roughly 2,000 people died and the city’s north end was levelled in 1917, when a French munitions ship blew up in the city’s harbour during the First World War.

By the turn of the century, the pressure to move away had become ingrained in the public consciousness, and original songs began to emerge about leaving home. One, “Prince Edward Isle, Adieu,” is a flippant takedown of Confederation that sees several characters leave the island behind: “’Tis clear, they can’t stay here / For work to do there’s none.” Sometime around the turn of the century, a similar song emerged from Nova Scotia. Folklorist Helen Creighton came across several versions of “Farewell to Nova Scotia” while researching along the province’s eastern shore: “Farewell to Nova Scotia, the sea-bound coast / May your mountains dark and dreary be / For when I am far away on the briny ocean tossed / Will you ever heave a sigh or a wish for me?” It’s become a popular traditional song, covered by artists like Gordon Lightfoot and the Real McKenzies.

By the time Newfoundland joined Canada in 1949, the Atlantic provinces were firmly established as the kid brother at the end of the table: scrawny, begging for the country’s leftovers, and aggravating to the adults who were trying to make serious conversation. Nearly 100,000 people left the region each decade from the 1940s to the 1960s, for familiar reasons, writes public policy researcher Donald Savoie: “continuing to go down the road to Central Canada to secure a job.” And while immigrants landed in Atlantic Canada, many of them were just stopping by on their way somewhere else.

Canada brought in equalization payments to have-not provinces in the 1950s, but they focused more on public services than the economy, and not much changed on the east coast. Some academics literally started to use the term “Maritimization” to describe the threat of broader economic marginalization. Acknowledging relative federal inaction toward the region’s generally lower quality of life, economic historian David Alexander once suggested that Atlantic Canadians might have to seek a “new notion of happiness” and look within the region, not abroad, to measure their standard of living — and that the happiness they’d find might not be all that happy. The struggle has continued into the 21st century. The region grew less than one-tenth of a percent between 2011 and 2015, compared to the national rate of 4.4 percent. Meanwhile, 10 percent of the local labour force is unemployed, versus Canada’s average of 6.9 percent. In other words, it’s still tough for the region to keep people and keep them working.

IN THE 20TH century, all of this began to seep into popular culture. Donald Shebib’s critically acclaimed 1970 film Goin’ Down the Road told the story of two down-on-their-luck Cape Breton boys moving to Toronto for work after years of “driving up and down Main Street looking for something you know damn well ain’t there.” It’s a beloved film — and one of Joel Plaskett’s favourites — but it’s among the grimmest pop portraits of the region’s never-ending exodus. Shebib’s Cape Breton is all dilapidated houses and broken-down boats, and in Toronto, things get worse for the boys — they can barely find work and resort to theft to stay alive. After the credits roll, a disclaimer appears: “The characters in this photoplay are fictional and any similarity to actual persons living or dead is purely coincidental.” But there are thousands, if not hundreds of thousands, of people for whom this story isn’t fiction.

As broadcast and recording technology began to democratize music in the mid-20th century, Atlantic Canadian musicians had the chance to become more ambitious. For those like fiddling folk icon Don Messer, that meant building a career at home and broadcasting shows across Canada, which he did for decades on on CBC Radio and Television. For others, life went full circle. Saint John’s Ken Tobias, who wrote a Top-10 Billboard hit and recorded with Righteous Brother Bill Medley, moved to cities like Montreal and Los Angeles only to come back to a quieter career in New Brunswick after a life of touring on next to no money. But most Maritime musicians who made a dent in music history settled far from home. Early country star Wilf Carter, born and raised in Nova Scotia, was banished from home after deciding to master the genre’s new yodelling craze as a teen, much to the chagrin of his staunchly religious Baptist minister father. He eventually found his way to Alberta wheat fields, Montreal recording studios, and New York radio stations. In the Big Apple, a secretary bestowed him a new name: Montana Slim. He went on to spend much of his life in Alberta and the U.S. Hank Snow, 10 years Carter’s junior and a Jimmie Rodgers fanatic, chased happiness from Brooklyn, Nova Scotia, all the way to Nashville, Tennessee, on the invitation of Ernest Tubb. There, he became a regular at the Grand Ole Opry, thanks to the success of songs like 1950’s “I’m Movin’ On,” which became a country standard and was eventually covered by the likes of Ray Charles and the Rolling Stones. That song might imply leaving home behind, but Snow would later rhapsodize the province he left more directly in 1968’s “My Nova Scotia Home,” waxing romantic about Cape Breton sunrises and the blue Atlantic sky.

In May 1972, Maclean’s magazine published two side-by-side profiles of Maritime artists who’d shipped away. One featured Snow, framed around his choice to live in Tennessee; the sub-headline read “Why Nova Scotia’s Hank Snow Ain’t Comin’ Home No More.” Snow wrapped his personal story around escaping the isolation of Canada’s east coast: he may have missed his Nova Scotia home, but leaving it, he said, was necessary. “I figgered it would just be so wonderful not to have to jump on an old train and ride 1,000 miles from Halifax to Montreal settin’ up, just to make a record.”

The issue’s cover star was Anne Murray, who had become the first Maritimer to climb the pop charts with her recording of Gene MacLellan’s “Snowbird,” a song about leaving home after heartbreak. The story, “What Upper Canada Has Done to Anne Murray,” opens with a ride on the rails from Halifax to Toronto: “The train is not unlike the country it runs through. . . . It’s full of beautiful reasons for leaving.” In her early career, Murray stocked her management with East Coasters, and they became affectionately known as the Maritime Mafia. Toronto, to them, was a compromise: they may have missed home, but it was where work had taken them. Murray had success before leaving the east coast — “Snowbird” was a million-selling single before she headed west — but she needed to live closer to the music industry if she wanted to keep any forward momentum. Without a strong follow-up to “Snowbird,” she worried of having to return to “the relative Maritime obscurity from whence I’d come.”

Upper Canada became a necessary pilgrimage for rock, country, and folk musicians, too. The young men of April Wine left the Halifax area for Montreal in early 1970, just five months after forming. “We almost had to move away,” says founding bassist Jim Henman, who left the band in its early days to return to Nova Scotia. “It was our goal. I can’t remember anybody from that period who actually accomplished any type of success by staying here as their home base.” Some songwriters put the Maritimes front and centre in their music long after they’d left it behind. Stompin’ Tom Connors was born in Saint John, New Brunswick, and raised in Skinners Pond, Prince Edward Island, and while he mostly lived on the road and in Ontario, he’d always introduce himself as “Stompin’ Tom from Skinners Pond.” Connors would fill Toronto’s Horseshoe Tavern with Maritimers in the late ’60s and early ’70s, playing songs like the cutesy P.E.I. potato anthem “Bud the Spud.” But he was not all playfulness. “New Brunswick and Mary,” for instance, addresses the heartbreak of a man bound for the Prairies, while “To It and at It” explores the stories of people from all corners of the Maritimes trying — and failing — to find a better life in Toronto. The song even became a recurring punch line in SCTV’s 1982 parody of Shebib’s Goin’ Down the Road, in which John Candy and Joe Flaherty play a lawyer and surgeon from Moncton who, despite their lucrative jobs, still go to Toronto for work. And that skit, in turn, helped inspire a YouTube series called Just Passing Through, in which two Prince Edward Islanders get stuck in Toronto and struggle to adapt to its culture, all while on their way to find work in the most recent Maritime expat Mecca: Alberta.

Ron Hynes lived and died in Newfoundland, but his most famous song, “Sonny’s Dream,” came to him while he was far away in Western Canada, travelling by bus in 1976. The song became a folk standard, but it’s a familiar east-coast tale: a farming mother worries that she’ll lose her son to the adventures of the sea and the world beyond it. The east coast even inspired songwriters who’d been born elsewhere. Stan Rogers lived most of his life in southern Ontario, but he built a reputation in folk circles as “Maritime Stan,” thanks to his Atlantic-focused debut, Fogarty’s Cove. He romanticized his family’s roots on Nova Scotia’s eastern shore and openly resented the fact he wasn’t born there. Separation and loss are constant themes in Rogers’s music, especially in the Maritime context, with songs like “The Idiot,” about a man working in Alberta and longing for home after making the expedition west. Alongside Cape Bretoner John Allan Cameron, Rogers is regularly credited with popularizing the Celtic-influenced east-coast traditional folk sound. More importantly, Rogers’s success helped demonstrate that original music could be written within the framework of this genre and thrive.

Soon after Rogers’s death in 1983, record labels began pillaging the region for all the Celtic-flavoured and traditional-influenced acts they could get their hands on, sending the likes of the Rankin Family, Great Big Sea, the Barra MacNeils, Rita MacNeil, Natalie MacMaster, and Ashley MacIsaac up the Canadian charts. To the rest of the world, theirs are the sounds most closely associated with Atlantic Canada. But that hardly paints a whole picture of the region’s culture — especially so in the past quarter-century. Traditional music basks in history rather than embracing the present. It’s safe. With the exception of daring experimenters like MacIsaac, the genre revels in conformity, rarely pushing boundaries or exploring new sounds, even when crossing over into pop. By the late ’70s, artists that were doing something far more forward-looking began to emerge on the east coast. The pressure to leave Atlantic Canada still hung in the air, and it still sometimes came across in lyrics, but the music sounded different than ever before. As is often the case, punk can take credit for shifting the creative zeitgeist.

THE REGION’S FIRST punk scenes sprouted up in isolation from one another, but were each crucial stepping stones toward sustainable independent music communities. Moncton’s Mark Gaudet, later a force in the bands Eric’s Trip and Elevator, started the city’s first punk band — named, aptly, Punks — in 1978 after seeing the Ramones play on Don Kirshner’s Rock Concert, and later formed the Robins, releasing a record in 1980. Da Slyme, from St. John’s, Newfoundland, were writing original songs by 1977 and put out a spray-paint-decorated LP in 1980. In Halifax, punk bands like Agro and Nobody’s Heroes lined up to play at the Grafton Street Cafe, a rare venue that allowed musicians outside of the rather un-punk Atlantic Federation of Musicians to perform. The isolation of small-town Cape Breton bred the Dry Heeves, who released a series of experimental punk tapes before finally performing a show in 1984. And in Fredericton, a label owner named Peter Rowan helped the Vogons put out the city’s first punk album after he started a local festival in the mid-’80s that finally cross-pollinated the region’s various municipal punk scenes. While this is hardly a full account of early east-coast punk — many bands never recorded, making scenes tough to fully document — it’s clear that the genre’s rise gave musicians in the region a sense of possibility and self-sufficiency.

Outside of punk, one of the first alternative bands in Atlantic Canada to properly record their music was Null Set, a group of Nova Scotia College of Art and Design (NSCAD) students. They released a seven-inch EP, the Talking Heads–esque New Job, in 1980. For the most part, though, the early days of east-coast alternative was confined to concerts. Almost all live music was local, since the 10-plus hour trek from Montreal prevented most touring bands from heading to the region. In those early days, it felt like “a very isolated place,” says Allison Outhit, who played in the new-wave band Staja/TANZ, and is now a vice-president of FACTOR, a music-funding body in Toronto. “You felt far away from everything.”

Midway through the decade, the outside world began to creep in. In 1984, on invitation from NSCAD, a young New York band named Sonic Youth came to speak to a class and play the art school’s cafeteria. Guitarist Thurston Moore said they played to “maybe eight people” — there was a big hardcore show across town, which some remember was headlined by Vancouver punks D.O.A. — but the Sonic Youth show left enough of an impression that it’s widely considered a crucial chapter in the city’s music history. Outhit, who was there, still calls it “a mind-blowing event for everybody concerned.”

One of the Halifax scene’s biggest early boosters was Greg Clark, who opened Backstreet Amusements arcade in 1980. “All the punk kids started hanging out there,” says Clark. And the punk kids wanted shows. So, seeing a business opportunity when the Grafton Street Cafe closed, Clark opened Club Flamingo in 1983 and started putting on all-ages concerts. It was only open a few months before the building was sold and the club shut down, but Clark continued to book music — and still does to this day.

In 1986, when a new iteration of Club Flamingo opened on Gottingen Street, its Halloween debut doubled as a release party for the compilation album Out of the Fog: The Halifax Underground 1986. The record was the first full-length document of the local alternative scene. Its release was more than just symbolic — the authors of the Canadian music tome Have Not Been the Same call the record proof to Haligonians that “alternative music could be made in their own backyard.” Local band Jellyfishbabies dropped their self-titled debut album that same year, giving them a chance to tour and earning them kudos from the BBC’s John Peel. They were the first band in the Halifax alternative scene to put out their own full-length, and, soon, the first to move away. The band released their second album from Toronto. “It just seemed like that’s what it would take to have a career playing music — to move to a bigger centre and hook up with people who were willing to give everything up to play music,” says Mike Belitsky, who joined the band after the move and now drums for the Sadies. Returning to Halifax was never really on his mind. “I’m just one of those people who feels like they have to be at the source, as opposed to starting the source,” he says. After another lineup change and a move to New York, Jellyfishbabies disbanded.

Basic English, who appeared on Out of the Fog alongside Jellyfishbabies, also attempted a move to Toronto only to break up. But there was another band on the compilation who did gain traction: the October Game, whose vocalist, Sarah McLachlan, handled ticketing at Club Flamingo. Aside from the Jellyfishbabies and Basic English, “nobody was trying to make it in the music biz,” says longtime scene-watcher Stephen Cooke, who covers Nova Scotia music for the Halifax Chronicle-Herald. “That wasn’t really a concept until one of the guys from Nettwerk happened to spot Sarah McLachlan with her band.”

When Greg Clark promoted a show for Vancouver band Moev in spring 1986, the October Game opened. Mark Jowett, a partner at Moev’s label, Nettwerk, was in the audience and soon spearheaded a year-long push to sign McLachlan. It worked. McLachlan’s success “started to help us out,” Clark says. “All of a sudden, people were like, ‘You can actually make money from this?’” says Cooke. McLachlan moved to British Columbia, where the label is headquartered, but back in Halifax, the ball was in motion: getting signed on the east coast was suddenly a real possibility. “Prior to that time, unless you were a fiddle player or Rita MacNeil, nobody had any kind of a career while still living in Halifax,” Cooke says.

Most of the other bands that emerged around this time didn’t last long, but many of their members went on to form or join more familiar acts. Few of them committed much to record. “It was expensive and it took a lot of money to put a record out, and not a lot of bands were doing it,” says Sloan’s Jay Ferguson. But these bands built a scene from the ground up, laying the foundation for what was to come. The cast of characters that emerged in the late ’80s would become major players a few years later. Sloan’s Patrick Pentland and Thrush Hermit drummer Cliff Gibb formed Happy Co., while future Joel Plaskett Emergency mainstay Dave Marsh helmed the band No Damn Fears with members of Jale and Sloan. And John Wesley Chisholm’s Black Pool featured, over time, Chris Murphy of Sloan, Matt Murphy of the Super Friendz, and both Marsh and Tim Brennan of the Emergency.

In 1987, Jay Ferguson and Chris Murphy began jamming with their friend Henri Sangalang, forming the band Kearney Lake Rd. The riff-rock band made a few tapes and got the attention of Fredericton’s Peter Rowan, who ran DTK Records. “When we started DTK, Halifax was a million miles away,” Rowan says. “These little communities were creating music without any idea that 100 miles down the road, people were doing the same thing.” Rowan took Kearney Lake Rd. on tour to Toronto and helped them record an album that was never released; they broke up in 1990. Rowan later managed Sloan, Eric’s Trip, and the Hardship Post, and he co-founded the Halifax Pop Explosion music festival with Greg Clark in 1993.

Ferguson and Murphy joined Andrew Scott and Patrick Pentland to form Sloan in early 1991. The experienced musicians earned attention quickly. They landed a slot at the East Coast Music Awards — a rarity for an alternative band at the time — and when a rep from MCA Canada, who’d come on Ferguson’s invitation, saw the band, he immediately wanted to discuss a contract. Rowan pushed MCA for a U.S. deal, and its newly acquired subsidiary Geffen came knocking. The band became the first in the region’s alternative community to ride music-industry hype to a major-label contract while staying in Halifax. They also became the first major recorded band — aside from traditional and Celtic-influenced acts — to eagerly incorporate east-coast localisms into their lexicon. Most famously, Murphy’s song “Underwhelmed,” which helped earn the band its major-label interest, references “the LC,” local slang for the province-run liquor store.

The band put out its full-length debut Smeared in 1992 through Geffen to much fanfare, only to be stonewalled by the label when their reference material shifted from Sonic Youth to the Beatles for its follow-up, Twice Removed. Geffen wasn’t happy with the change and asked the band to re-record it. When they didn’t, the label released the album anyway but gave it next to no support. Faced with the same possibility for all of their future records, the band decided to quietly break up. Sort of. It was a year-long, messy divorce that lasted most of 1995, spanning numerous awkward interviews and concerts, including a headlining gig at Edgefest at the Molson Canadian Amphitheatre in Toronto.

Some of the murderecords roster at a Stinkin’ Rich seven-inch photoshoot, including Rob Benvie and Joel Plaskett of Thrush Hermit; “Stinkin’ Rich” Terfry; Stephen Cooke; Ian McGettigan of Thrush Hermit; and Jay Ferguson and Patrick Pentland of Sloan.

[© Catherine Stockhausen]

“We were just trying to avoid getting contractually fucked by Geffen, because if we said officially we were broken up, then we would be under a different set of rights than if we were an intact band that they dropped,” Chris Murphy says. “So we didn’t want to say that we were officially breaking up, and then what ended up happening was we ended up getting tons of press because of that.” But there was also tension within the band’s ranks, as drummer Andrew Scott had moved to Toronto, making it impossible to practise. “I would rather break up than replace a member,” says Murphy. “I would have rather started over.”

IT WASN’T MUCH of a breakup. No one left or got replaced. Sloan was back in the studio recording One Chord to Another by Christmas 1995, and they fairly negotiated their way out of their Geffen contract soon after. But even if they had never gotten back together, the legacy of their first run was immeasurable. In a few short years, the band injected a huge sense of promise and possibility into Halifax and across the east coast. “That was a fun time,” Cooke says. “Bands were really getting their shit together, learning how to write songs properly, and taking a little more of a professional attitude.” Before Sloan, he says, “there wasn’t a lot of ambition onstage. People were doing it for fun, and sometimes that’s the right reason to do something, but once bands had to prove themselves a little bit more than that, the possibility of Halifax having some music worth remembering on a bigger scale finally came to fruition.”

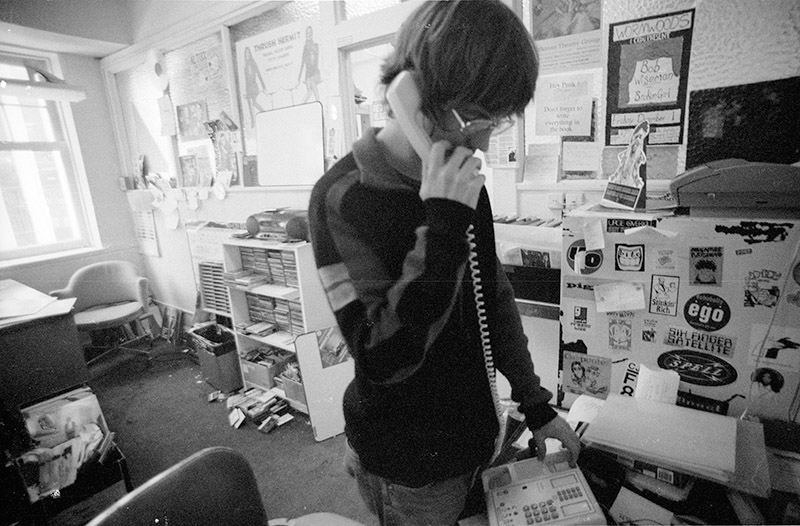

Chris Murphy at the murderecords office.

[© Catherine Stockhausen]

An indie-label ecosystem had blossomed. No Records, founded by future Halifax municipal councillor Waye Mason, emerged as a home for acts like the power-pop band Cool Blue Halo and hip-hop troupe Hip Club Groove. Cinnamon Toast Records put out albums by Outhit’s new outfit Rebecca West and teenage band Plumtree. And, influenced by Ian MacKaye’s Dischord Records in Washington, D.C., Sloan decided to launch a label, too.

Backed by some of the band’s Geffen funding, murderecords became a vehicle for creating a permanent document of their local scene, putting out a handful of albums and EPs and a slew of 45s. Left without a band for much of 1995, Murphy and Ferguson spent the year working out of the Barrington Street murderecords office, packaging records by hand and manually handling mail orders. The label’s catalogue included releases from an east-coast who’s who: the Super Friendz; Eric’s Trip; Stinkin’ Rich, now better known as Buck 65 or CBC Radio host Rich Terfry; and Kingston band the Inbreds, who later moved to Halifax themselves. “For so long, bands had been ignored in Halifax,” Ferguson says. “It was such an especially fertile period in the early ’90s. It was the right time to make sure everything was documented.”

The glass ceiling that geography, economics, and history had long held over pop, rock, and alternative music in Atlantic Canada was, through Sloan, finally broken. Unlike their predecessors, from Hank Snow to Sarah McLachlan, Sloan managed to get a record deal without moving away, enlivening their own scene in the process. It was suddenly cool to be from the east coast — and, sometimes, to sing about it. Labels and journalists began to swarm the region, clamouring to discover the next Sloan. There were a few candidates, among them Eric’s Trip, Jale, the Hardship Post, and Cool Blue Halo. One of the youngest contenders, a gang of kids from the Halifax suburb of Clayton Park, was called Thrush Hermit. The band had three constant members: Rob Benvie, Ian McGettigan, and Joel Plaskett.

(1) —The boom was only for settlers, of course — the Aboriginal population in the Maritimes had by then shrunk to 3,000, mostly on reserves.