5

EIGHT MINUTES OF CUT AND SLASH

8.55 A.M. TO 9.15 A.M.

A THIN RED STREAK TIPPED WITH STEEL

8.55 A.M. TO 9.05 A.M.

Fifty-five-year-old Brigadier General Sir James Scarlett, commanding the Heavy Brigade, was a large, florid, ruddy man and short-sighted. Popular with all ranks, he had recently commanded the 5th Dragoon Guards but had never seen active service. He was, nevertheless, open to advice from his official staff ADC Lieutenant Alexander Elliot and Colonel Beatson, both of whom had campaigned in India. Glancing left, Elliot spotted the tips of Russian lances fretting the high ground, followed by the heads and horses of Russian cavalry coming over the edge of the Causeway Heights. Scarlett had not noticed but the skyline was pointed at as Lucan and his staff came galloping up, shouting, ‘Scarlett! Scarlett! Look to your left!’ About 400 yards away and 100ft above a huge grey Russian wave was gathering, about to break over and engulf his column. ‘Left wheel into line,’ Scarlett immediately ordered, which brought his squadrons into one line, two troopers deep. Because the rough ground of the cavalry encampment and an old vineyard lay to his left, Scarlett moved his first three squadrons further right to enable the 5th Dragoon Guards to come up in between to the left. Coolly oblivious to Lucan’s shouted demands to charge immediately, Scarlett set about fixing his brigade’s alignment. Officers sat motionless on horses, with their backs to the enemy as NCOs darted about dressing the ranks. Their only hope of survival was to present the Russians with a compact front.

Four squadrons of Russian cavalry were repulsed by Sir Colin Campbell’s 93rd Highlanders barring the way to the British logistic base at Kadikoi village and Balaclava. Meanwhile, the British Heavy Brigade charged uphill against a mass of Russian cavalry more than six times their number. They struck the compacted Russian cavalry with four successive attacks from different directions, which unhinged the mass and caused it to break and flee. It was a remarkable success.

The Russians on the ridgeline pulled up so abruptly that the rattle of accoutrements was clearly audible to spectators on the Sapoune Heights. The appearance of British cavalry below had been completely unexpected. They gaped, fascinated, at the scene below. The absence of hurry and the imperturbable dressing of ranks going on below appeared menacing. Scots Greys with busbies and red tunics seemed terribly like the bearskins of the awful Guards they had faced at the Alma. Had they taken to horseback? The immediate halt led to a spillage of Russian horsemen beyond the flanks, so that the tight phalanx of mass cavalry took on a crescent-shaped appearance. A trumpet sounded and the advance resumed, this time hesitant and slow.

Major General Ryzhov commanded Liprandi’s cavalry and he had been ordered: ‘On the occupation of the last enemy redoubt by our infantry, to immediately – even starting from the spot at full speed – to throw ourselves at the English cavalry occupying a fortified position near the village of Kadikoi and the town of Balaclava.’

He decided to move forward at a quick trot, ‘not at full speed as ordered’, because charging an enemy thought to be a mile distant would blow the horses. But suddenly there they were, right in front of him. Ryzhov, like many of his contemporaries in the Tsar’s army, followed battle tactics as a form of parade evolutions. Instead of immediately attacking, utilising height and surprise, he paused to execute a drilled approach. With the British equally acting as if on parade, Ryzhov decided ‘as the rest of the divisions each came up the slope, I directed them to parts of the enemy formation’. This resulted in the Russians stretching and extending their line along the Causeway Heights. This ponderous allocation of deliberate tasks was distracted by the Ural Cossack regiment on the right, whose ‘commander tore off at high speed without any thought or any of the necessary arrangements’. The predatory Cossacks wanted instinctively to attack the vulnerable British. Ryzhov saw the English cavalry had anchored its left flank on the rough vineyard terrain to his right, and were protected ‘by a rather strong battery emplaced in Kadikoi village’. His Cossacks were already moving on this side, which further complicated the spillage over the ridge on both flanks, created by the sudden halt in the centre. ‘An officer sent with my orders was no longer able to stop them,’ he remembered with exasperation.1

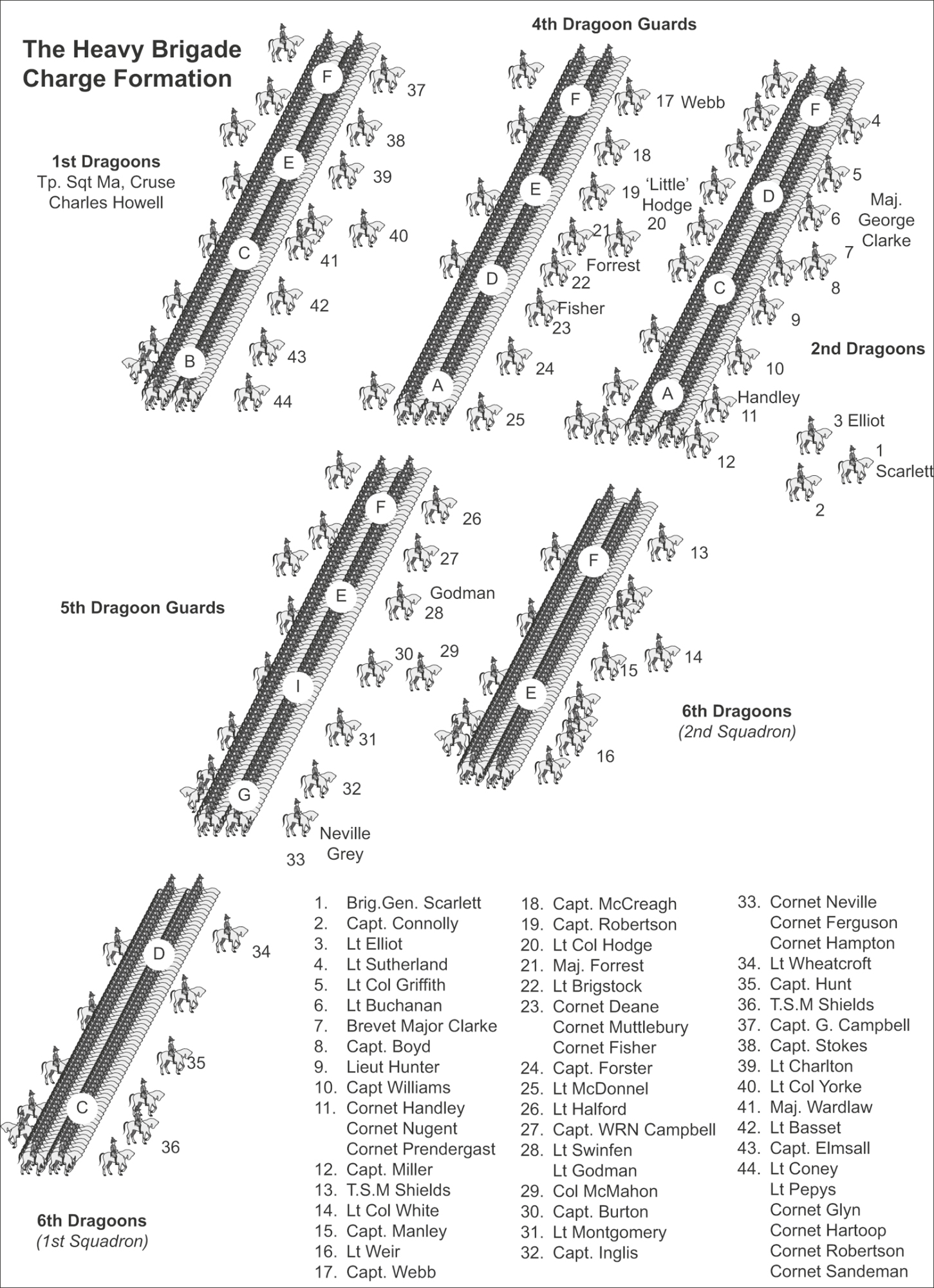

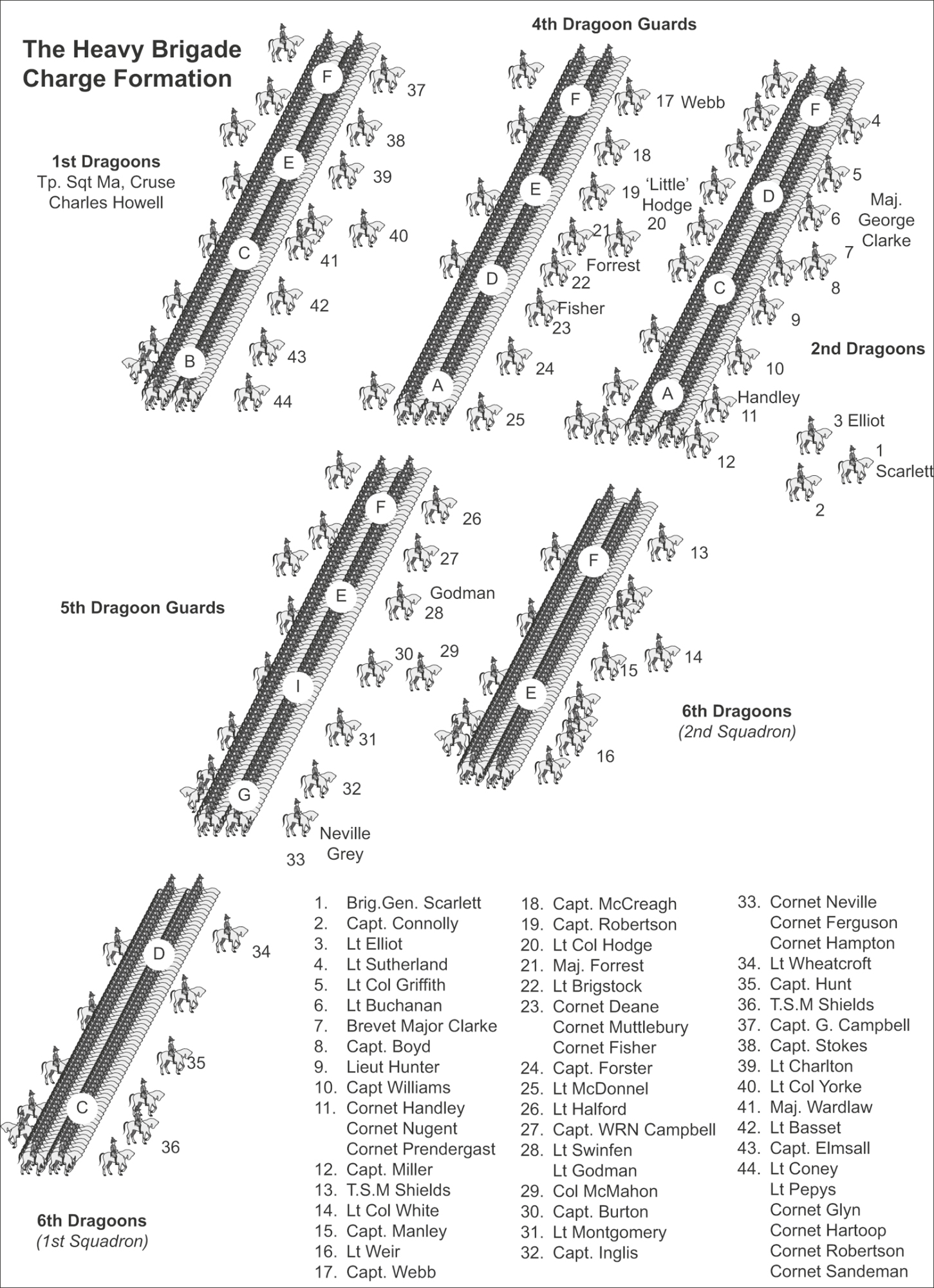

The positions of the various squadrons and regiments of Scarlett’s Heavy Brigade are shown in this schematic, as well as the location of some major witnesses of the action. The 6th and 2nd Dragoons hit the Russian assembly first, followed by the 6th’s second squadron and the 5th Dragoons. The 1st Dragoons and lastly the 4th Dragoons were the coup de grâce that finally split the Russian mass apart.

Cossacks occupied a unique position in the Russian forces, recruited for just three years before entering the reserve. They originated from the Russian and Ukrainian settlers that used to secure the frontiers of Old Russia. Military service, long compulsory for Cossacks, was regarded as an honourably martial way of life, affecting a man’s stature in society. A Cossack father would provide the horse, sabre and accoutrements his son would need at his own expense; the government only issued the carbine. Cossacks were better educated than the dull Russian soldiery, and less amenable to its unthinking rigid discipline. They had a robust frontier attitude that led to a looser and more informal relationship between officers, junior leaders and men. Unthinking Russian infantry were resolute in defence, whereas Cossacks were observant and cautiously independent, with a highly developed instinct for self-preservation. Dying in place was hardly a virtue if one could fight advantageously elsewhere. They were born raiders, merciless in pursuit and particularly adept at sniffing out defence gaps. Their proclivity for precipitate retreat, and placing loot above duty did not endear irregular Cossacks to the more traditional regular Russian cavalry. Captain Robert Hodasevich with the Taroutine Regiment remembered their scruffy, unruly appearance, with clothes often ‘in tatters’:

They have few words of command, but all their movements are directed by signals. These signals are imitations of the cries of different animals found in the Caucasus: they howl like jackals and wolves and bark like dogs, and mew like cats.2

The men understood these signals, but their training did not suit them for conventional cavalry operations.

As Ryzhov’s Hussar columns began to descend the slope, the Cossacks, he recalled with irritation, ‘moved with a frightful “Ura!” and quickly shifted back and forth in a long row like some kind of flock or flight of birds, but not however, closing with the enemy’.

Instead of swiftly plunging down the slope, having caught out the British in a chance meeting engagement, Ryzhov busied himself sorting out Hussar squadrons as they reached the crest. Meanwhile, ‘the enemy stood calmly,’ he recalled, ‘and waited as if by agreement.’ An ominous silence reigned on both sides; ‘only the Cossacks were shouting,’ he remembered, ‘and that was far off and nobody paid them any attention.’

A tense William Russell on the Sapoune Heights saw a sudden movement to the left of the assembled mass, when an element ‘drew breath for a moment, and then in one grand line dashed at the Highlanders’ covering the Balaclava gorge. Partially obscured by a small hillock were 550 93rd Highlanders occupying a 150-yard frontage blocking it. They were reinforced at each end by 100 sick and convalescents from Balaclava, and Turkish survivors from the stormed redoubts.

The Highlanders watched attentively as the Causeway Heights suddenly came to life. Hundreds of Russian cavalry were starkly silhouetted against the skyline, amid the protrusions of the captured redoubts. A great slice detached itself from the mass, and four squadrons of 400 Hussars came hurtling towards them. Charging cavalry often looked forbiddingly more numerous than they actually were. Russell found them frightening. ‘The ground flies beneath their horses feet,’ he observed from 2 miles away. ‘Gathering speed at every stride, they dash on towards that thin red streak tipped with a line of steel.’ Campbell, confident in the capabilities of the Minié rifle, chose not to form square, but engage from a line two deep. With the front rank kneeling and the rear standing, the whole firepower of the regiment could be brought to bear, rather than the quarter side of a square.

Surgeon George Munro with the 93rd remembered Campbell riding along their front ‘telling the regiment to be “steady”’, for if necessary every man should have ‘to die where he stood’. His aide, Lieutenant Colonel Sterling, recalled, ‘he looked as if he meant it’. ‘Ay, Ay sir Colin,’ the cheery soldiers responded, ‘we’ll do that.’ Campbell was an experienced soldier, sure of his ground, and his infantry outnumbered the approaching cavalry three to one. Munro recalled, ‘I do not think there was a single soldier standing in the line who had an anxious thought as to our isolated and critical position or who for a moment felt the least inclination to flinch before the charge of the advancing cavalry.’ They knew what to expect and anticipated ‘a regular hand to hand struggle’.

Onlookers predicted a grim outcome. ‘Ah what a moment!’ remembered Mrs Fanny Duberly, standing by Russell. ‘Charging and surging onward, what could that little wall of men do against such numbers and such speed?’ The Russian cavalry ‘passed in front of us a few hundred yards’, remembered Private Charles Howell with the 1st Dragoons, and ‘the thought was in my mind, oh the poor 93rd, they will be all cut up, their’s more than fifty to one against them.’ The Russians were galloping so boldly and fast that one trooper remarked to Major William Forrest with the 4th Dragoon Guards, ‘Bedad, they must take them for Turks.’ ‘They never expected to meet English there I am sure,’ agreed Lieutenant Temple Godman with the 5th.3

‘The sudden appearance of a steady line of redcoats, as if sprung from the earth, caused the enemy to falter,’ Munro remembered. Campbell had learned his trade in the Peninsular War. ‘As we sat our horses,’ Howell remembered, ‘we heard quite plain the sharp words, Kneeling ranks Ready – Present and in an instant many a Russian soldier’s saddle empty.’ The first volley, a flash and billowing cloud of smoke, accompanied by rapid crackling one second later, was likely premature, probably at 600 yards. Few Russians fell and they came on. ‘The distance is too great,’ Russell tersely reported:

The Russians are not checked, but still sweep onwards through the smoke, with the whole force of horse and man, here and there knocked over by the shot of our batteries above. With breathless suspense every one awaits the bursting of the wave upon the line of Gaelic rock.

‘Present!’ the command rang out again. By now, with just 100 yards to go, the scarlet line would have felt the reverberation of hundreds of thundering hooves through the ground. ‘Fire!’ Campbell bellowed as the rear rank of rifles with fixed bayonets erupted with crackling fire and spluttering smoke. There was a notable recoil within the Russian mass, horses plunged and reared amid a chorus of shrieks from riders. As the smoke rolled back on the Highland ranks they brought their bayonets up to charge, ‘manifesting an inclination to advance and meet the cavalry half way,’ Munro recalled. Campbell sharply checked them: ‘Ninety-Third! Ninety-Third! Damn all that eagerness!’

Private Donald Cameron in the ranks remembered that after the second volley ‘they seemed to be going away. We ceased firing and cheered.’ But it was not over yet. The Russians changed direction and ‘wheeled about and made a dash at us again’. Colour Sergeant J. Joiner with the 93rd saw that ‘they found it too hot to come any further’ and swung round to take them in their right flank. ‘The Grenadiers, under my old friend [Captain] Ross, were ordered to change front,’ Munro remembered, ‘and fire a volley,’ which caused visible damage: ‘This third volley was at much nearer range than the previous ones and caught the cavalry in flank as they were approaching, apparently with the intention of passing our right.’

Joiner claims, ‘volley after volley was fired into them so fast’ that ‘their own dead and dying choked their way’. Campbell, with a keen veteran eye, had anticipated the Russians would seek to envelop a weak flank, and shared the insight with his ADC. ‘Shadwell!’ he said, nodding towards the Russians, ‘that man understands his business.’

Russell’s subsequent vivid dispatch composed from 2 miles away created an iconic account of what was in effect simply a brief cavalry-infantry skirmish. The ‘thin red streak’ became the ‘thin red line’, immortalised by British military history as an example of inspirational courage: rock-hard Highland infantry seeing off masses of Russian cavalry seeking to trample them. Mrs Fanny Duberly standing alongside was hardly likely to contradict the respected correspondent of the prestigious Times newspaper. ‘One terrific volley,’ she recalled, ‘a sudden wheel – a piece of ground strewed with men and horses.’ Russell’s exciting dispatch climaxed with ‘another deadly volley flashes’ that ‘carries death and terror into the Russians’, who ‘wheel about’ and ‘fly back faster than they came’. ‘Bravo, Highlanders! Well done!’ was the predictable patriotic applause from spectators on the Sapoune Heights. The gripping yarn was embellished in similar newspaper accounts that published eyewitness letters. The ‘93rd opened such a fire upon them that you could see them falling out of their saddles like old boots,’ claimed one private with the 1st Dragoons. ‘Dozens of saddles were soon empty,’ another 1st Royals eyewitness claimed. Other depictions point to a paucity rather than multiplicity of corpses sprawled in front of the Highland line. Surgeon Munro, coming forward to treat them, found ‘not more than 12’, while Captain George Higginson on the high ground with Russell ‘could not observe any casualties’. Lieutenant Stotherd with the 93rd wrote to his parents, convinced the stand had been a resounding success: ‘We gave them three British cheers and peppered them so much that they turned and swerved away and finally beat a retreat at a hard gallop, leaving many a corpse behind.’ Whatever the body count, the 93rd had mastered a crisis.4

Two years later Surgeon Munro received an insight into the true extent of the Russian casualties. He met a Russian Hussar officer in the Crimean capital Simferopol with a severe limp, who had participated in the charge. ‘In the first place, we did not know that you were lying down behind the hill close to the guns,’ he explained, ‘which were keeping up a galling fire on our columns.’ They were heading to capturing them and were in mid-stride, when:

You started from the ground and fired a volley at us. In the next place, we were unable to rein up or slacken speed, or swerve to our left before we received your second volley, by which almost every man and horse in our ranks was wounded.

When they tried to wheel left, ‘a wing of your regiment changed front’ and delivered another punishing volley, ‘one of your bullets breaking my thigh and making me the cripple that you see’. Russian cavalry were generally strapped to the saddle in action, which explains the relatively low casualty count. ‘A mounted man,’ the Russian pointed out, ‘though severely, or even mortally wounded, can retain his seat in the saddle long enough to ride out of danger.’ Much of the cavalry fleeing back to the Causeway Heights was reeling, semi-conscious but fastened to their saddles.5

The first crisis in front of Kadikoi village and Balaclava was settled in minutes. The attention of the onlookers on the Sapoune Heights now shifted to the unfolding catastrophe about to overwhelm the British cavalry.

SUCH A CHARGE! EIGHT MINUTES OF CUT AND SLASH

9.05 A.M. TO 9.13 A.M.

An axiom of cavalry warfare was that no mounted unit should ever receive an attack standing stationary. Forward momentum was vital, to stave off defeat. Strangely enough, Brigadier General Scarlett’s insistence on standing still and calmly dressing the ranks in front of the Russian menace proved sound. Every British trooper knew they were in a bad place. Corporal Joseph Gough with the 5th Dragoon Guards looked up, thinking, ‘at first we thought they were our Light Brigade, till they got about twenty yards from us, then we saw the difference’. Corporal John Selkrig grimly realised, ‘we were taken completely at a disadvantage’.6 Officers sitting motionless on their chargers and ignoring the enemy while waiting for NCOs to dress the ranks was enormously reassuring to men acutely aware of their vulnerability. It represented order in the face of pending chaos. Lord Lucan, the British cavalry commander, was so impatient to get Scarlett moving he ordered his own duty bugler, Trumpet Major Joy of the 17th Lancers, to sound the charge. Scarlett studiously ignored the call, intent on aligning his squadrons to present a cohesive front. No officer would move without his order.

There was much to reflect upon during this interval between life and death. Squadron commander Major George Clarke in the lead Scots Greys line was apprehensive that his charger ‘Sultan’, habitually unnerved by galloping squadrons during training, would revert to form and swerve across the line of advance. Troopers uneasily fidgeted and fingered sabre pommels. Newly sharpened sabres had been issued in England six months before. Troop Sergeant Major George Smith with the 11th Hussars remembered ‘an order was given that they were not to be drawn till required, when in the presence of the enemy’. Sword practice was banned for good reason. Every time the blade was withdrawn from its steel scabbard and replaced, it lost some of its keen edge. Experienced cavalrymen stuffed straw down the full length of the scabbard to protect newly sharpened blades. Not everyone had done so. Lack of training, tedious picket duty and constant false alarms had resulted in a dropping away of standards by the less experienced. The sudden early morning alarm gave no time to remedy blunt blades.

Cornet Henry Handley with the Greys fingered his prize purchased acquisition, one of the new Colt and Adams revolvers, vastly superior to the conventional one-shot pistols. A number of officers and NCOs had chosen to purchase these five or six percussion cap models. Some of the unease in the ranks was mellowed by the euphoria of the moment. They were living the heavy cavalryman’s dream of battle, for which many had joined. Nothing on this epic scale had occurred since Waterloo nearly fifty years before. Then, as now, the Inniskillings and Scots Greys were drawn up together, and were going to replicate the glorious charge of the Union Brigade. This produced an upsurge of tribal regimental fighting spirit. ‘There is something grand and exciting in a charge,’ recalled one Inniskilling private. ‘You brace up with all your nerves and prepare yourself for mortal combat.’ ‘But,’ he added, ‘it is not very pleasant to have showers of musket balls whistling over your ears.’ Cornet Grey Neville waiting with the 5th Dragoons in the centre of the second line remained nervous. Since the outbreak of war, he was convinced he was going to die; he had a brother in the infantry siege lines in front of Sevastopol. Grey Neville was a promising and popular young officer but not a good swordsman or horseman and up ahead were Cossacks, reputed experts.

Further to the left and rear Major William Forrest waited motionless in the second line with the 4th Dragoon Guards. On the verge of battle, he remembered, his thoughts were of his wife Annie. Cardigan had hounded him from the 11th Light Dragoons in 1843, when as Commanding Officer he refused Forrest’s reasonable request for leave to attend her when she was ill with her first pregnancy. Even the Duke of Wellington had to intercede in the scandalous society quarrel that resulted. His new Commanding Officer, Edward Hodge, was more reasonable and likeable, but disapproved of wives on campaign. He would later have to share a hut with her, because Forrest was his second in command. ‘In my mind a very disgusting exposé to put any lady to,’ he insisted. Hodge was loved by his soldiers, but he was exasperated by their tendency to drink themselves to death, but paternal enough to care. Hodge’s father had been killed in the cavalry skirmish at Genappe the night before Waterloo, adding to the poignancy of the moment. This was the first major cavalry action since.7

Trickling slowly down the slope towards them came the Russians. Those ascending the ridgeline, coming up from the North Valley, were getting their first view of the South Valley. On the left, they were being hit and occasionally unhorsed by Captain Barker’s W Battery. They did not expect to see British cavalry arrayed – as if on parade – before them. They also had brief time for reflection. Captain Khitrivo, commanding the 8th Weimar Hussar Squadron, was comforted by the thought that if he should fall, his old father would not be saddled with his regimental debt, cleared the night before. Cornet Veselovski in his regiment had just been reinstated months before, having been demoted to private following a scandalous fracas with another cornet in a guard house three years ago. He was determined to distinguish himself in the coming battle, but had barely minutes to live. The pressure of more and more squadrons coming up the slope behind them was precipitately pushing the lead units into a totally unexpected situation. Lieutenant Yevgenii Arbuzov on the left with the Saxe-Weimar Hussars remembered: ‘While still on the move we saw that we would not have to deal with an artillery park, as supposed in our battle orders, but with English cavalry fully ready for battle.’

The advance was going to be tricky, because ‘between us and the English, we could see their horse lines and serving tables’. An abandoned English cavalry encampment was in the way with partially struck tents. Lieutenant Stefan Kozhukhov was watching the cavalry advance from his artillery placement on the high ground at the head of the South Valley, near Kamara village. His impression was that the Russian cavalry, having overrun the Turkish redoubts, were complacent, believing the battle to be virtually over. There was neither command dexterity nor time to react to this unexpected development. ‘Either General Ryzhov ordered the attack too late,’ he subsequently surmised, ‘or it was commanded when the Hussars had not yet managed to form up.’ He watched as the hesitant Russian cavalry moved down from the Causeway Heights like ‘an unorganised mob’.8

When Scarlett was satisfied his men were ready, he ordered his own trumpeter, Monks, to sound the charge and the Heavy Brigade started to spur their mounts uphill. From the Sapoune Heights, the action looked lost, as Russell recalled:

The Russians advanced down the hill at a slow canter, which they changed to a trot, and at last nearly halted. Their first line was at least double the length of ours – it was three times as deep. Behind them was a similar line, equally strong and compact. They evidently despised their insignificant looking enemy.

Lord George Paget, watching to the north with the Light Brigade, had identified the difficult ground the ‘Heavies’ would have to cross, because they had been encamped on it: ‘Anyone who has ridden, or attempted to ride, over an old vineyard will appreciate the difficulties of moving along its tangled roots and briars and its swampy holes.’

It was no conventional charge, Trot through Gallop at 200 yards and then Charge for the final fifty. There was neither time nor space. ‘The pace of the Heavy Brigade never could have exceeded 8 mph,’ Paget remembered, ‘during their short advance across the vineyard’, and they were going uphill. ‘Suddenly within 20 yards of the dry ditch,’ when it appeared the Russians ‘must annihilate and swallow up all before them’ with a ‘handful of redcoats, floundering in the vineyard,’ Paget saw ‘the Russians halt, look about, and appear bewildered, as if they were at a loss to know what next to do!’ The bizarre scene ‘is forcibly engraved in my mind’, he remembered. ‘They stop! The Heavies struggle-flounder over the ditch and trot into them!’9 Scarlett’s first three squadrons of the Heavy Brigade, one of Inniskillings and two of the Scots Greys, barged into the centre of the Russian mass. The Greys keened a low tribal-like moan while the Inniskillings gave a high-pitched cheer. Three hundred men were attacking about 1,600 Russians. The swift change of direction from open column into line and further reorganisations to enable units to close up, meant by accident rather than design that the Heavies would hit the Russians in multiple waves of regimental attacks from different angles.

Another axiom of mounted tactics, creating the elan characteristic of cavalry troops, was that once the charge was sounded, it was ‘do or die’. There could be no recall or turning back, commitment was total. As the first scarlet wedge plunged into the Russians, it disappeared from view. Onlookers on the Sapoune Heights were horrified. They appeared to be swallowed in the maw of the grey Russian mass, whose flanking arms unfolded to pull the British inside. Sergeant Timothy Gowing, viewing to the right of the Heights, remembered ‘a number of the spectators, as our men dashed into that column, exclaimed, “They are lost! They are lost!”’ Private Albert Mitchell with the Light Brigade was thrilled. ‘I have often heard of cavalry charging cavalry,’ he recalled thinking, ‘now will be a chance of seeing it.’ Although cavalry charge in lines, head-on collisions with opposing lines, the stuff of feature films and novels, only rarely occur. Horses instinctively swerve or pull up when confronted with obstructions, always stronger than the pain of the spur or pull of the bit. One side generally loses its nerve and turns about even before horses begin to baulk at self-destruction. Sergeant Timothy Gowing, viewing at distance, described the essence of this initial collision: ‘heavy men mounted on heavy horses, and it told a fearful tale’. British horses were larger in girth and height than their more wiry adversaries. Fear of possible Austrian intervention had resulted in a dearth of Russian cavalry available for the Crimea, with poor quality ponies and insufficient fodder.10

Mitchell remembered ‘we could see little else but smoke and dust’ on impact, ‘for the Russians fire their pistols when they charge and then use the sword’. Firing from the saddle is futile unless the muzzle is almost touching the target, because pistols and carbines were notoriously inaccurate. One of the earliest casualties was Lieutenant Colonel Darby Griffiths, the Greys Commanding Officer, struck in the head by a carbine shot. It took off his bearskin and had him reeling in the saddle, blood pouring down his face. Aiming was haphazard, with barrels jerked about by horses producing little control where shots went. It was dangerous to let the enemy get too close before resorting to swords. Sergeant Charles McGrigor with the Scots Greys recalled: ‘When within two yards of our enemy, they fired upon us with pistols, but ’ere they could get them out of their hands, we were into them with our swords like the very devils, laying them low at every blow.’

‘All I saw was swords in the air in every direction,’ remembered Lieutenant Temple Godman with the 5th Dragoons, ‘the pistols going off, and everyone hacking away right and left.’ ‘On the smoke clearing away,’ Mitchell ‘could plainly see our red jackets had gone clean through their leading squadrons and were engaged with the next.’ Russians turning about at the approach of Scarlett’s wave were sabred as the Inniskillings and Greys ‘threaded’ their ranks, spurring their horses between the gaps. Scarlett and his staff were the first inside the line. The general with his helmet looked less conspicuous than his ADC, Lieutenant Elliot, whom he insisted wear the cocked hat appropriate to his staff appointment, thereby attracting much of the Russian ire. They broke the line and the Greys, resplendent in their prominent bearskins, drove a wedge through the opening.11

‘Oh such a charge!’ a captain in the Inniskillings wrote home: ‘Never think of the gallop and trot which you have often witnessed in Phoenix Park when you desire to form a notion of blood-hot, all mad charge, such as that I have come out of.’

Troopers sat well back in their saddles at the instant of shock. Horses were totally unrestrained by the bit and spurred forward to give it its head. Swords were pointed forward as men rose in their stirrups. ‘Such splendid cutting and thrusting never was seen,’ claimed Sergeant Thomas Kneath in the Scots Greys. ‘Their horses, little cats of things, could not stand the jumping forwards of our powerful animals, with a pair of spurs driven into their sides.’ The greater height of the British horses meant every cut and thrust had the advantage of gravity. Kneath was confident of the superiority of:

Our heavy dragoons swords, longer and straighter than the Russians’ which is a complete curve, and is not the slightest use in giving point, so that all they could do was to cut at our fellow’s helmets, which they did heavily, but only dented them.12

The perennial cavalry debate about cut versus thrust was still not settled after the French wars. Stab wounds penetrated deeply, pierced vital organs and caused internal bleeding, a killing rather than disabling stroke. Penetration was invariably mortal, whereas a man with several cuts might fight on. French Colonel Antoine de Brack, called ‘Mademoiselle’ on account of his elegant good looks, wrote after the Napoleonic Wars: ‘It is the point alone that kills; the others serve to wound. Thrust! Thrust! as often as you can: you will overthrow all whom you touch, and demoralise those who escape your attack.’

Attacking with the point as the Inniskillings and Greys closed in extended line was the only practical offensive option when riding knee to knee. Lieutenant Elliot saved Scarlett’s life on breaking the line when the short-sighted general failed to notice a tall Russian officer bearing down on him. Elliot barged him with his horse and ran him through the body with such force that the thrust went home to the hilt. The complication of the thrust, as evidenced by training notes, was that the blade needed to be parallel to the ground to slide between the ribs without being entangled in the cage. ‘The Russian was turned quite round in the saddle before the sabre could be disengaged,’ described a witness, ‘and then he fell dead to the ground.’ Elliot barely managed to retain his sword with the momentum, as he passed him. Instinctive slashing took over in most melees, because it took a cool head to target, thrust and withdraw the sword.13

The Heavies’ ‘do or die’ effort was pressed home with maniacal courage. ‘I never in my life experienced such a sublime sensation as in the moment of the charge,’ confessed an Inniskilling officer. ‘Some fellows talk of it being “demoniac” like the Beserkers of ancient Irish history, because it “made me a match for any two ordinary men” and “gave me an amount of glorious indifference to life”.’ ‘From the moment we dashed at the enemy,’ he later wrote, ‘I can tell you I knew nothing but that I was impelled by some irresistible force onward.’ Only with maniacal cutting, thrusting and energy-sapping slashing would they get through this Russian mass. They had to keep moving forward to survive, otherwise they would be blocked, surrounded and cut down.

Forward-Dash-Bang-Clank … It was glorious! Down, one by one, aye, two by two fell the thick skulled over numerous Cossacks … I could not pause. It was all push, wheel, frenzy, strike and down, down, down, they went. Twice I was unhorsed, and more than once I had to grip my sword tighter, the blood of foes streaming down over the hilt, and running up my very sleeve.

Major George Clarke’s horse Sultan was predictably spooked at the outset and in the process his imposing bearskin was knocked off. Superstitious Russians gave him a wide berth, convinced that a bare-headed man taking on acres of flashing swords had to be imbued with satanic powers. Clarke looked the part when he emerged on the other side, blood streaming over his face and neck from a deep cut across the skull. ‘They say you could not see a redcoat, we were so surrounded,’ recalled one Scots Grey officer, ‘and for ten minutes it was dreadful suspense.’

The charge was soon a ‘scrimmage’, ‘more like a row at a fair’, recalled Lieutenant Robert Scott Hunter. ‘The scene was awful, we were so outnumbered and there was nothing but to fight our way through them, cut and slash.’ The bluntness of swords against thick padded Russian greatcoats caused problems. ‘I made a hack at one,’ Scott Hunter remembered, ‘and my sword bounced off his thick coat, so I gave him the point’ and he reeled from the saddle. ‘Such a mill you could not imagine,’ Cornet Daniel Moodie claimed, describing the metal-on-metal noise as being akin to an industrial workshop. The Russian mass became so tightly compacted, they could barely swing a sword. ‘The slaughter was awful,’ claimed Sergeant Charles McGrigor, with many Russians ‘lying dead on their horses’ necks or cruppers, for being strapped into the saddle, they could not fall from their horses’, snagging and entangling those fighting around them. Cornet Henry Handley blessed the day he purchased his Colt and Adams revolver. Lanced and severely wounded he was surrounded by four Cossacks, three of which he managed to shoot from the saddle. This intensity of hand-to-hand fighting could not be physically maintained for more than eight to ten minutes, without succumbing to exhaustion. Scott Hunter described the energy-sapping fight through a succession of whirling and fleeting images:

I made a hack at one, and my sword bounced off his thick coat, so I gave him the point and knocked him off his horse. Another fellow just after made a slash at me, and just touched my bearskin, so I made a rush at him, and took him just on the back of his helmet, and I didn’t wait to see what became of him, as a lot of fellows were riding at me, but I only know that he fell forward on his horse, and if his head tumbled like my wish, he must had have it hard, and as I was riding out, another fellow came past me, whom I caught slap in the face, I was bound his own mother wouldn’t have known him.14

If Scarlett’s intrepid 300 from the Innskillings and Greys failed to punch through, they would lose momentum and be overwhelmed. They were being surrounded, as Scots Grey Sergeant David Gibson realised:

I was in the centre, cutting right and left, when a Russian came in rear and gave me such a clip on the bearskin that it came off my head, and I got two cuts on the cranium before I was aware of it. I thought it was all up with me.

Faint with loss of blood and blinded by the flow gushing down his face, ‘one gave my sword a crack and sent it spinning out of my hand.’

Both Russian flanks had changed direction and imploded at Scarlett’s penetration, seeking to take the English in flank and rear. As they exposed their own sides and backs in doing so, the second Inniskilling squadron crashed into the Russian left flank. At the same time the 5th Dragoon Guards, following up the Greys, hit the Russian centre for the second time. Gibson was rescued, but badly cut up. He had been lanced, received two sword cuts on his left hand, one on the right hand and left arm, and two cuts to the head with another across the brow. As he was led off to hospital, he was regarded a very lucky man.

Paget, viewing from the Light Brigade lines, watched these successive blows against the Russian mass. ‘One body must give way,’ he appreciated. The noise was completely deafening, ‘the clatter of the swords against the helmets, the trampling of the horses, the shouts!’ The unearthly din became an enduring memory and ‘still rings in one’s ears!’ Successive blows from arriving British waves were visibly destabilising ‘the heaving mass’ of Russians that ‘must be borne one way or other’. It was not certain which way it would go.15

CRACKING OPEN THE MASS

9.10 A.M. TO 9.15 A.M.

‘I held my breath, waiting to see how this would end,’ recalled Major General Ryzhov, ‘as I did not have any reserve.’ Ryzhov’s later account of the battle was somewhat disingenuous in avoiding unpleasant truths. Dismayed at the sheer ferocity of the British assaults, he began to assume the worse. ‘If the hussars turned back,’ he recalled, ‘I would not have anything with which to stop the enemy.’ Successive squadrons of Russian cavalry coming up the rear slope were jam-packed together, unable to fend off barging British cavalry on big horses thrusting and cutting their way through from all directions. Ryzhov claimed: ‘Never had I seen a cavalry attack in which both sides, with equal ferocity, steadfastness, and it may be said – stubbornness, cut and slashed in place for such a long time.’

He estimated the contest ‘slashed away at a standstill for about seven minutes’, before they were pushed, teetering over the top of the Causeway Heights. Witnesses claim the Russians fought in silence except for a deep moan-like noise, punctuated by a constant hissing between determinedly clenched teeth. Ryzhov worried that any ‘descent from the heights,’ if he were pushed over, ‘with its unavoidable disorder, would help the enemy cavalry deal us a great defeat.’

Major General Khaletskii’s Ingermanland Hussars were in serious trouble. The general discharged his pistol at close range in the melee and was set upon and slashed about the ear and neck, which sent his sabre spinning. His orderly, 55-year-old Corporal Karp Pivenko, gave him his own and slipped from his horse to recover the general’s sabre and fended off another attack on him, for which he was to be subsequently decorated. Within a year, though, he would be dead from typhus. The Ingermanland Hussars on the left were unhinged by the two successive blows to the Russian centre punched in by Scarlett’s group followed by the 5th Dragoons and the second Inniskilling squadron that emerged from the left oblique. Lieutenant Yevgenni Arbuzov’s command was caught off balance and disorientated: ‘Our regiment’s 2nd Squadron, being pressed from the left side, veered to the right at full gallop, pushed on the 1st Squadron and forced it unwittingly to do the same.’

This meant his own platoon ‘did not have any enemy facing it at the moment we collided with the English’. They chased the English left and rear and ‘hewed into it’. He had only dim memories of the crazed melee that resulted: ‘I only remember that I struck one dragoon in the shoulder, and my sabre bit so deep into him, that I only drew it out with difficulty.’

The cut Englishman pitched from the saddle, his spurs snagging on Arbuzov’s reins as he went down, tearing at the bit in the horse’s mouth. ‘My horse reared up’ in the closely packed fighting ‘and nearly fell over,’ he recalled.16

Russian officer casualties, many at the front when the English tore through, were considerable, perhaps four out of ten. Captain Petr Marin, ahead of the 3rd Squadron, which he commanded, was knocked from his horse. By the time he managed to remount, he was slashed about the head, one cut down to the bone. He presented a ghoulish appearance, his moustache clotted with blood as he managed to rally his men. Captain Khitrivo’s 8th Squadron was hit as he attempted to form line from column. His debt was settled, having been paid the night before to protect his old father. He went down with his horse, struck by a bullet and multiple sabre cuts; when he got to his feet the squadron saw him cut down again. He was subsequently recovered to Scutari Hospital, Constantinople on an English steamer but died before he got there. Cornet Veselovski, seeking to redeem the regimental disgrace that had reduced him to the ranks, disappeared underfoot, never to be seen again. Wounds were horrific, medieval in character. Staff Captain Prince Mutsal Khamzaev received a slash to the left rear of his skull and lost two incisors on the return stroke to his left chin. Shell fragments pitted his right elbow. Pitching from the saddle decreased survival chances even further. Horses had the equivalent of a heavy mace at the end of each leg, and these were kicking out in the tight press.

The size and weight of the English chargers was a combat multiplier, as dangerous as the men riding them. Weight conferred momentum, every slash from greater height was aided by gravity, while Russian counterstrokes required more effort. Padded Russian greatcoats offered some protection to the torso; the most injuries were to the face, neck and upper extremities. Captain Matveeski in Arbuzov’s regiment was slashed across the face to the right, the blade snagging the corner of his eye socket, penetrating the cheekbone to the skull and inflicting massive trauma to his brain. As he momentarily reeled, unbalanced by the stroke, his assailant plunged his blade into Matveeski’s chest, entering the ribcage above the eighth rib. Amazingly he lingered on in regimental service until succumbing to his devastating injuries in 1857. Russian casualties were rising. Arbuzov briefly broke off the action, ‘I wanted to see my squadron better,’ he recalled, ‘and bring it to good order.’ But half his men were already down.17

‘Then we went in and gave them what they will not forget,’ remembered a 5th Dragoon Guards officer, chasing after the Greys through the centre. ‘Some of the Russians seemed to be rather astonished at the way our men used their swords’ – it was light curved versus heavy straight, Troop Sergeant Major Henry Franks recalled. ‘It was rather hot work for a few minutes; there was no time to look about you.’ Disturbing images of bloody viscera was Private James Prince’s enduring memory as the 5th Dragoons plunged in after Scarlett’s 300 Inniskillings and Greys. It was a gory passage. ‘There was some being with their heads half off, and some with their bowels out, and some with their legs shot off with cannon balls.’ ‘We soon became a struggling mass of half frenzied and desperate men, doing our level best to kill each other,’ Franks remembered. ‘Swords were flying about our ears as if by magic,’ one Inniskilling trooper recalled, ‘but we drove them back in queer style.’ ‘We’re heavier than the enemy,’ Franks realised, ‘and we were able to cut our way through them, in fact a good many of them soon began to give us room for our arms.’

Up on the Sapoune Heights, Raglan and the staff watched mesmerised as scarlet threads irresistibly stitched a passage through the grey Russian colossus. ‘Grey horses and red coats had appeared right at the rear of the second mass,’ William Russell observed. Sergeant Timothy Gowing, watching further to the right, was equally excited. ‘At times our men became entirely lost in the midst of the forest of lances,’ he remembered, ‘but they cut their way right through as if they had been riding over a lot of donkeys.’ Elements suddenly broke out of the rear of the Russian mass. ‘A shout of joy burst from us and the French, who were spectators,’ he recalled, ‘as our men came out of the column.’ Incredibly, Scarlett’s first 300 had got through.18

Anyone knocked from a horse was in serious trouble. Corporal Joseph Gough’s horse ‘was shot; he fell, and got up again’ but Gough ‘was entangled in the saddle, my head and one leg were on the ground’. The horse galloped forward again, snagging him even further in a hopeless predicament, until it fell again. At the point of being impaled by a Russian lancer ‘and I could not help myself’, his friend ‘Macnamara came up and nearly severed his head from his body; so thank God I did not get a scratch!’ Gough caught a loose Inniskilling horse, snatched a pistol from its holster, and managed to shoot a Russian bearing down on him through the arm: ‘He dropped his sword, then I immediately rode up to him and ran him through the body, and the poor fellow dropped to the ground.’

Corporal James Taylor was less fortunate; he was surrounded and set upon by Russians and ‘a good many of them’ suggested one eyewitness, ‘as he was very strong and a good swordsman’. Taylor’s left arm was nearly chopped through in four places, ‘all the Russians seemed to cut at the left wrist,’ the witness claimed, because ‘so many men lost fingers, and got their hands cut.’ Taylor’s body was later found, but it ‘was nearly cut to pieces’.

Cornet Grey Neville with the 5th Dragoons, a poor rider and swordsman, also ended up on the ground. He had had a premonition of death. He rode at a group of Russians and in trying to bowl them over went down with them. Totally winded, he was lanced four times on the ground, feigning death. When Grey looked up he saw a Russian dragoon had dismounted to finish him off. The sword came down cutting at his head and sliced his ear, but Grey’s helmet saved him. He lay with both sides trampling over him until his plaintive cries for help attracted Private John Abbot from the Dragoons. Once he recognised him, he stood defiantly astride his prostrate body. Abbot held onto his horse’s bridle and killed three Russians who tried their luck, until he slung Grey across his back and sought medical assistance. Grey’s sad premonition of death came to fruition; a broken rib that had pierced his chest was to finish him off, though he lingered for nineteen more days. As he lay dying his final wish was that his father, Lord Braybrook, should provide for his gallant rescuer. Abbot was decorated and awarded £20 each year for life.19

Just as Scarlett’s 300, chased by the 5th Dragoon Guards, was starting to overwhelm the first Russian echelon, the Russian crescent-shaped formation was hit on the right flank by the 4th Dragoon Guards. At virtually the same time, as if orchestrated, the 1st Dragoon ‘Royals’ crashed in from a right oblique direction. Its Commanding Officer had charged up from redoubt number 6 on his own initiative. The Russian mass had now been struck five times in a succession of staggered frontal and flank attacks. Lord George Paget, watching from the Light Brigade lines, observed the discernible cumulative effect the successive blows had:

Their huge flanks lap round that handful, and almost hide them from our view. They are surrounded and must be annihilated! One can hardly breathe! Our second line, half a handful, makes a dash at them! One pants for breath! One general shout bursts from us all! It is over!

The coup de grâce was administered to the right flank by ‘Little Hodge’ and the 4th Dragoon Guards, while the Royals plunged in from the oblique. Major William Forrest riding with them recalled ‘we had very bad ground to advance over, first thro’ a vineyard, and over two fences, brush, and ditch then thro’ the camp of the 17th’. General Richard Dacres ‘saw it all from the hill’, the Sapoune Heights, and remembered the cool and deliberate way the flank was turned: ‘The 4th came up at a very slow trot, till close to [the enemy], when they charged them right in flank at a gallop and sent them right about.’

Colonel Edward Hodge’s account was conspicuous by its simple brevity. ‘The Greys were in a little confusion and retiring,’ he explained, ‘when our charge settled the business.’ Hodge’s men burrowed swiftly from flank to flank across the entire Russian mass.

The fight now became a scrap; it was not about swordsmanship, more about ‘laying about’ with one’s blade, which was often blunt. Forrest cut at a Russian:

But do not believe that I hurt him more than he hurt me. I received a blow on the shoulder at the same time, which was given by some other man, but the edge must have been very badly delivered for it has only cut my coat and slightly bruised my shoulder.20

Darby Griffiths, the Greys Commanding Officer, later admitted the Greys’ swords were indeed defective. ‘Whenever our men made a thrust with the sword, they all bent and would not go into a man’s body.’ Private Isaac Stephenson got ‘one slight cut on the arm from a “cut 6” by a Russian Dragoon’. But before he could get at him, ‘there were no less than three sabres of our fellows going on him thicker and faster’ and he was down. Private James ‘Jack’ Auchinloss ‘bowed to the pommel of his saddle’ to dodge a pistol shot fired by a ‘huge’ Russian lancer, which ricocheted off the hilt of his sword. ‘Fair play, mate,’ he shouted and spurred after him incensed through the crowd until he clasped his assailant around the neck ‘and battered his face to a jelly with his sword hilt, then throwing him down’. Blunt blades led many a soldier to aimlessly flail about in the compressed mass, lost in the fury and terror of the moment, when cool heads might have dispatched opponents with a simple thrust. Private Thomas Ryan in the 4th Dragoons had his helmet battered off in the fight and his reddish fair hair clearly showed ‘he had about 15 cuts on his head, not one of which,’ according to a witness, ‘had more than parted the skin’. Death came from ‘a thrust below the armpit, which had bled profusely’. He was the only man in Hodge’s regiment to die.21

‘My friends it is a thing impossible for a person that is in battle to give anything like a true account of it,’ declared Private Charles Howell, with the 1st Dragoon Royals. ‘He knows scarcely anything, only what he happens to do himself, not always then,’ he recalled. ‘All that I know is that I used my sword the best way I could.’ These last two attacks on the right flank completely unhinged the Russians. ‘It was the first time I ever crossed swords with the enemy,’ admitted one trooper with the 1st Dragoons, ‘and it was very sharp work.’ In the exuberance of the charge they sensed they were turning the battle. ‘I never enjoyed such a sport in my life,’ the trooper admitted; ‘it was far beyond my expectations; I actually felt overjoyed meeting them at a gallop.’ ‘The Russians,’ he recalled, ‘went over the hill again like a drove of scattered sheep.’22

Trumpet Major William Forster recalled: ‘when the Royals saw that they could not be restrained, they gave one loud shout and let us at them … Without waiting for the command of an officer or any one else we rushed as hard as they could gallop at the enemy’ catching them in the flank and rear. ‘It became a frightful scene of slaughter’ and ‘the Russians had to turn tail and run for it.’ As they linked up with the Greys, who had preceded them, there was ‘a real British hurrah’. ‘They give way!’ Paget observed from the Light Brigade lines on the flank. ‘The heaving mass rolls to the left! They fly! Never shall I forget that moment!’

The time had arrived for the Light Brigade to administer the coup de grâce and hit the teetering Russian mass in the flank. But they remained stock-still. ‘They bolted,’ remembered Sergeant Timothy Gowing watching the Russians from the Sapoune Heights, ‘that is, all that could – like a flock of sheep with a dog at their tails.’23

The remarkable fight was over in barely eight to ten minutes. Eight hundred British cavalry had put twice their number to flight, despite being tactically wrong-footed and obliged to charge uphill over difficult ground. Casualties among Ryzhov’s cavalry were some forty to fifty killed and over 200 wounded. Virtually every squadron commander in the Ingermanland Hussars was dead or wounded, with one man in six a casualty, despite outnumbering their opponents two to one. The British Heavy Brigade lost ten killed and ninety-eight wounded. In ten minutes, despite catching the British unawares at the beginning of the day and overrunning the Turkish redoubts on the Causeway Heights, the main Russian objective of the day was already lost. The British logistics park at Kadikoi remained intact and the ostensibly open route to Balaclava harbour was blocked. General Liprandi’s primary objective for this probing attack was compromised by two of the most iconic actions ever celebrated in British military history. A third was to come later that same morning.